Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of Tobacco Excise Equivalent Goods

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of the administration of tobacco excise and excise equivalent goods.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Excise duty (excise) is a tax placed on excisable goods—tobacco, alcohol (excluding wine), and fuel and petroleum products—that are produced or manufactured in Australia. When imported these commodities are treated as excise equivalent goods, and customs duty is imposed at a rate equivalent to excise, to allow consistent treatment of the imported and Australian produced goods. From 2010–11 to 2014–15, the government collected an average of $8.1 billion in tobacco excise and customs duty each year.

2. The movement and storage of tobacco is controlled through licensed warehouses administered by the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) and the Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP). The goods must be manufactured and/or stored in these warehouses—referred to as being underbond—until they are released for home consumption, moved to duty free outlets or exported. The ATO has administered excise since 1999 (a responsibility under the Excise Act 1901 transferred from the (then) Australian Customs Service). Under the Customs Act 1901 DIBP is responsible for administering excise equivalent goods and collecting customs duty. In 2010, the ATO’s role was expanded, under powers delegated by the Chief Executive Officer of Customs, to include the management of excise equivalent goods stored in warehouses under section 79 of the Customs Act 1901 (s.79 warehouses): a measure that aimed to streamline administration of excise and customs duty. Agency roles and responsibilities pertaining to the 2010 delegation are agreed through a head Memorandum of Understanding between the ATO and DIBP and a subsidiary agreement specifically for excise and excise equivalent goods.

Audit objective and criteria

3. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the administration of tobacco excise equivalent goods, and the collection of customs duty.

4. To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO assessed whether:

- management arrangements between the ATO and DIBP support the effective administration of tobacco excise equivalent goods;

- ATO and DIBP systems and procedures support DIBP’s collection of customs duty for tobacco excise equivalent goods; and

- compliance activities for tobacco excise equivalent goods are appropriate and effective.

5. The report did not explicitly examine the administration of tobacco excise, as the production of tobacco and tobacco goods in Australia was diminishing, and ceased during 2015. However, tobacco excise was indirectly covered as there are some common arrangements with excise equivalent tobacco. While the audit has focused on tobacco, common arrangements exist for the administration of other excise equivalent goods (alcohol and petroleum).

Conclusion

6. The ATO and DIBP have established a suitable framework for administering a range of indirect taxes, including customs duty paid on excise equivalent goods, but the framework has not been implemented adequately over the previous five years, and the administration of tobacco excise equivalent goods and the collection of customs duty has fallen short of effective practice.

7. Over this period, DIBP did not meet its obligations under the Memorandum of Understanding to provide access to information and systems to the extent necessary for the ATO to carry out key aspects of its delegated role. Reconciliation of the movement of underbond tobacco with the revenue collected or reported is seldom done, and an absence of suitable warehouse licensing policy and inadequate compliance strategies contributed to a lack of visibility and assurance around tobacco storage. In addition, the assessment of tobacco risks lacked consistency, and compliance activities required a more risk focused and structured approach informed through greater contribution by DIBP.

8. Since mid-2015, there has been a renewed and positive focus within DIBP on arrangements with the ATO for administering tobacco excise equivalent goods. The two agencies are working more closely together to address many long standing issues noted in this report that, when fully implemented, would support more accountable, effective and streamlined administration of excise equivalent goods more broadly.

Supporting findings

Management and reporting arrangements

9. The administrative framework for managing tobacco excise equivalent goods is sound, providing detailed roles and responsibilities for the ATO and DIBP, and an appropriate committee structure. However, the (then) Australian Customs and Border Protection Service did not meet the intent of the agreement by sufficiently engaging with or supporting ATO officers. Specifically, DIBP’s decision not to provide ATO officers with the necessary level of access to DIBP’s systems limited the ATO’s ability to administer its roles and responsibilities under delegated powers for almost five years. This may have also limited the extent of the streamlining of regulatory services for industry participants, limited the effectiveness of the selection and conduct of risk and compliance activities for tobacco excise equivalent goods, and reduced the level of assurance that the correct amount of tobacco customs duty was being collected. There is no evidence that the ATO invoked dispute resolution processes set out in the head Memorandum of Understanding between the ATO and (then) Australian Customs and Border Protection Service to resolve the issue in a timely way.

10. From mid-2015, the newly established DIBP (following integration with the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service) has renewed engagement with the ATO to address many long standing issues related to the management of excise equivalent goods. Nevertheless, problems remain in exchanging information between the agencies, and the development of reporting mechanisms to the Secretary of DIBP and the Commissioner of Taxation would provide ongoing assurance that the arrangement is being managed effectively.

11. There is no calculation or reconciliation that provides assurance that the correct amount of customs duty is being collected and reported:

- neither the ATO nor DIBP examines the value of the charges due from the physical quantities of imported tobacco goods moved into the underbond system, and the actual volume of these goods (and customs duty paid) reported entering the domestic market;

- revenue (excise and customs duty) collected from tobacco goods is reported in Australian Government Budget documents, against forward estimates based on projected consumption (that include assumptions about fluctuations in demand, for example due to increases in excise rates). The assumptions do not factor in the size of the illicit trade in tobacco and potential changes to the supply of and demand for dutiable goods as a result of the increase in costs in the legitimate market; and

- the size of the trade in illicit tobacco (and value of revenue lost) has been the subject of much analysis, but the various results have not been agreed by key government and industry stakeholders. As at February 2016, the ATO was developing a tax-gap estimate for tobacco that will provide an estimate of the value of the illicit tobacco market and resultant revenue foregone.

Licensing s.79 warehouses administered by the ATO

12. The ATO has applied excise licence policy and process to excise equivalent licences, although the licences are issued under different legislation, the Excise Act 1901 and the Customs Act 1901 respectively, and no analysis of the requirements of the Acts has been conducted. With regard to tobacco, the ATO has focused on the administration of excisable goods, although the cessation of the excise tobacco industry in Australia (and a corresponding increase in revenue from customs duty) has been foreshadowed for several years. The ATO could have been more active in its administration of licensing for s.79 warehouses under its administration.

13. The process for issuing and renewing a licence to operate a s.79 warehouse administered by the ATO could be improved. The ATO has changed the wording on licences to more clearly identify the goods that may be stored in a warehouse, and is developing a new checklist for the application process, but more could be done. The number of criminal history checks on licence applicants has been reduced, but the ATO has not analysed the impact of this on incidences of non-compliance.

Risk and compliance

14. Risks associated with the administration of tobacco excise equivalent goods have not been consistently assessed. Fluctuations in the annual risk rating (from ‘low’ to ‘moderate’ to ‘significant’) lacked a clear rationale, with the most recent rating based on reputational risk to the ATO and DIBP. The shared administration of this risk between the ATO and (then) Australian Customs and Border Protection Service has been ad hoc and informal. There has been little evidence that the expectations of the relationship have been met regarding access to and the timely exchange of: knowledge and expertise of risk staff; and risk-related information, both ongoing and as part of the annual risk management process.

15. The planning and implementation of compliance activities for excise equivalent goods moving in and through s.79 warehouses administered by the ATO could be improved, including by DIBP engaging with the ATO as set out in the administrative framework. Within the ATO, there is a lack of process for the selection of warehouses (or other aspects of the tobacco industry) for targeted compliance activities, relying heavily on manual assessment. Testing of a sample of completed compliance activities for tobacco excise equivalent goods indicated the need for better recording in the ATO’s systems.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 2.19 |

To support the administration of excise equivalent goods, the ANAO recommends that:

ATO response: Agreed. DIBP response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.2 Paragraph 3.5 |

To support the issuing and renewal of licences for operators of s.79 warehouses administered by the ATO, the ANAO recommends that the ATO develops specific guidelines and procedural documentation for the administration of s.79 warehouses under ATO control. ATO response: Agreed. DIBP response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.3 Paragraph 4.13 |

To improve the assessment of risk associated with the administration of excise equivalent goods, the ANAO recommends that the ATO and DIBP develop working arrangements to share risk related information and intelligence and assess risks based on evidence and a joint understanding of the risk environment. ATO response: Agreed. DIBP response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.4 Paragraph 4.34 |

To improve the effectiveness of compliance activities associated with the storage and movement of excise equivalent goods, the ANAO recommends that:

ATO response: Agreed. DIBP response: Agreed. |

Summary of entity responses

16. The ATO’s and DIBP’s summary responses to the report are provided below, while their full responses are at Appendix 1.

ATO response

The ATO welcomes this review and considers the report supportive of our overall approach to managing the administration of Tobacco excise equivalent goods under delegation from the Chief Executive Officer of Customs.

The review recognises that the ATO is committed to working closely with the DIBP to further enhance our administration and compliance approach. The audit identified a number of opportunities for improvement in our administration and risk assessment processes which the ATO will work more closely with the DIBP.

The ATO agrees with the four recommendations contained in the report.

DIBP response

The Department of Immigration and Border Protection (the Department) accepts the four recommendations presented in the report on the Administration of Tobacco Excise Equivalent Goods and acknowledges that further work is required to improve the cooperative relationship between the Department, the operational arm of the Department—the Australian Border Force (ABF) and the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) in the administration of Excise Equivalent Goods (EEGs).

Since the integration of the Department and the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service (ACBPS), the Department and the ABF have strengthened ties with the ATO through developing channels for information sharing, joint operations and other pathways to ensure appropriate treatment of risk around EEG goods at and beyond the border. The report reinforces the importance of this work. The Department and the ABF will continue to develop a close and collaborative working relationship in the indirect tax and EEG space.

The Department notes that the report provides examples of importations of illicit tobacco and includes discussion on the illicit tobacco market. While illicit tobacco presents complementary risks, these do not directly impact the administration of the EEG regime. The Department believes the illicit tobacco market is not indicative of the effectiveness of EEG administration by either the ATO or the Department.

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Excise duty (excise) is a tax placed on excisable goods—tobacco, alcohol (excluding wine1), and fuel and petroleum products—that are produced or manufactured in Australia. When imported, these commodities are treated as excise equivalent goods, and customs duty2 is imposed at a rate equivalent to excise to allow consistent treatment of the imported and Australian produced goods. The legislative framework for the administration of excisable goods and excise equivalent goods, and the collection of excise and customs duty, is set out in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Legislative framework for the collection of excise and customs duty

|

Excise |

Customs duty |

|

Excise Act 1901; Excise Tariff Act 1921; and Excise Regulation 2015. |

Customs Act 1901; Customs Tariff Act 1995; and Customs Regulation 2015. |

Source: Department of the Treasury consultation paper, Excise Equivalent Goods Administration, August 2012, pp. 6–7.

1.2 Excise (and customs duty) can also be applied selectively to pursue non-revenue objectives. In the case of tobacco (and tobacco products), increases in excise rates have been justified by the ‘strongly addictive qualities of tobacco, its serious health impacts, its uptake by minors and the costs that smoking imposes on non-smokers’.3 Over the period 1999 to 2015, excise rates for tobacco increased 654 per cent. From 1999, in addition to indexing for inflation4, excise rates for tobacco and tobacco products were subject to a one-off increase of 25 per cent in April 2010, with four further annual increases of 12.5 per cent imposed as part of the National Tobacco Strategy 2012–2018 (to take effect between 2013 and 2016).

Revenue raised from excise and customs duty

1.3 In the five year period, 2010–11 to 2014–15, the government collected an annual average of $31 billion per year in excise and customs duty: $17.8 billion from petroleum; $5.1 billion from alcohol; and $8.1 billion from tobacco. The relative proportion of excise to customs duty from tobacco products decreased significantly over the same period, as the Australian industry moved from domestic to imported product (Figure 1.1). By mid-2016, stocks of Australian produced tobacco will be exhausted and no further excise revenue is expected from tobacco.

Figure 1.1: Excise and customs duty collected from tobacco, 2010–11 to 2014–15

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO and DIBP data.

Administration of excisable and excise equivalent goods

1.4 Goods subject to excise must be manufactured and or stored in licensed premises or warehouses—referred to as being underbond—until the excise liabilities are paid and the goods can be: released into the Australian domestic market for home consumption; moved for sale in duty free outlets; or exported. Similar underbond arrangements apply to excise equivalent goods: once cleared by the Australian Border Force at the port of entry, the goods must be moved into and stored in a licensed warehouse until customs duty liabilities are paid.5

1.5 The system of licensed warehouses and permissions6 (to move excise and excise equivalent goods) is administered by the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) and the Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP).7

1.6 The ATO has administered all aspects of the excise system (including the licensing of premises for the manufacturing and storage of excisable goods and the collection of the tax) since 1999, when the responsibility for excisable goods under the Excise Act 1901 (Excise Act) was transferred from the (then) Australian Customs Service to the ATO. The rationale for the change was that, as an indirect tax, the administration of excise laws should be integrated with that of other taxation laws. The transfer of responsibility to the ATO was supported through legislative amendment in 2001.8

1.7 From 1 July 2010, administration of excise equivalent goods was also transferred to the ATO from the (then) Australian Customs and Border Protection Service, following a recommendation in the Productivity Commission’s Annual Review of Regulatory Burdens on Business: Manufacturing and Distributive Trades, 2008, to minimise duplication of revenue administration and compliance costs for excise and excise equivalent goods. In November 2009, the (then) government announced that the ATO would take responsibility for the administration of all excise equivalent goods ‘to cut red tape and reduce compliance costs for business by delivering a single administration for businesses to deal with’.9

1.8 The arrangement (for the administration of excise equivalent goods) operates under powers delegated by the Chief Executive Officer of Customs to ATO officers (rather than administrative orders or legislative changes), where ATO officers become ‘officers of Customs’ in the administration of licences for warehouses where excise equivalent goods can be stored, and the control and movement of these goods. DIBP retains responsibility for border activities relating to excise equivalent goods, and importers of these goods that are warehoused continue to use DIBP’s Integrated Cargo System (ICS)10 to report and enter the goods for warehousing, and to pay the customs duty.11

Licensing

1.9 Warehouses that are used for the manufacture and/or storage of excisable goods must be licensed under Part IV of the Excise Act; and for excise equivalent goods, warehouses must be licensed under section 79 of the Customs Act (referred to in this report as ATO administered s.79 warehouses). A licensed warehouse may be a:

- private warehouse, where the licence holder is the owner of the warehoused goods; or

- general warehouse, where the licence holder is storing goods on behalf of the owners of the goods.12

1.10 An application for a licence for premises where excisable goods can be manufactured and/or stored is available from the ATO website, and should be lodged with the ATO. Similar arrangements are in place for a licence to operate an ATO administered s.79 warehouse, although it is a requirement that an applicant must first register as a client with DIBP’s Integrated Cargo System. Warehouses that are used to store both excise and excise equivalent goods must be dual licensed. An overview of the licensing process for s.79 warehouses administered by the ATO is shown in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2: Administration of licences for s.79 warehouses administered by the ATO

Note: AAT is the Administrative Appeals Tribunal.

Source: ATO Learner Guide, Excise Equivalent Goods Introduction, p. 24.

Permission to move excisable goods and excise equivalent goods

1.11 Applications for permission to move excisable goods underbond (that is, from one licensed premises to another), or for export or to release them into home consumption can be submitted online to the ATO. The ATO processes the applications, and manages all aspects of the lodgement of excise returns and the payment of the tax.

1.12 Similar arrangements are in place with the ATO for permission to move excise equivalent goods underbond, but moving them into home consumption (or for re-export) and the payment of customs duty is conducted through DIBP’s ICS. Importers (or their agents) are required to lodge the following:

- for warehousing prior to delivery into the domestic market—a Nature 20 Warehouse Declaration (N20) with DIBP to store the imported goods in a licensed warehouse; and

- for delivery from a licensed warehouse into the domestic market—a Nature 30 Ex-Warehouse Declaration (N30) with DIBP (for all or part of the goods included in the N20), pay applicable duties, taxes and charges to DIBP, and be issued with an ICS-generated Authority to Deal that is presented to remove the goods.

1.13 The agency (the ATO or DIBP) that a business needs to contact in relation to excise equivalent goods and the payment of customs duty is set out in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: Agency contact for excise equivalent goods—ATO or DIBP

|

Type of interaction |

Type of operator |

||

|

|

General warehouse operator |

Private warehouse operator |

Importer/owner of the goods |

|

Licensing—apply, amend and renew |

ATO |

ATO |

N/A |

|

Lodging import and warehouse declarations: N20 and N30 |

N/A |

DIBP (using ICS) |

DIBP (using ICS) |

|

Permissions: apply, amend or cancel |

N/A |

ATO |

ATO |

|

Paying—customs duty, indirect taxes |

N/A |

DIBP |

DIBP |

|

Advice—(including ICS support and refund and drawback circumstances) |

DIBP |

DIBP |

DIBP |

|

Advice—licensing and permissions |

ATO |

ATO |

ATO |

|

Claiming refunds and drawbacks claims on customs duty |

N/A |

DIBP (using existing system to claim drawbacks and ICS to claim refunds) |

DIBP (using existing system to claim drawbacks and ICS to claim refunds) |

|

Seeking remissions of customs duty |

ATO |

ATO |

ATO |

|

Compliance—post transaction verification for stored goods |

ATO |

ATO |

ATO |

Note: N/A = Not Applicable (an importer that is not a private warehouse owner is not responsible for warehouse licensing matters, and a general warehouse operator is not responsible for warehouse declarations or permissions for the goods held on behalf of others).

Source: ATO.13

Legislative, policy and commercial changes in the Australian tobacco industry

1.14 The operation, regulation and management of tobacco goods in Australia have been subject to considerable change since 1999, including the cessation of the domestic production of tobacco and tobacco products in 2015. The key changes are set out in Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3: Key changes in the tobacco industry in Australia

Note 1: As of 1 December 2012, under the Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011 and associated regulations, retail packaging must not contain any promotional text other than brand and variant names. As a result, tobacco products not complying with the legislative requirements had to be withdrawn from the Australian retail market by 1 December 2012. These withdrawn products were to be either destroyed or exported.

Source: ANAO.

1.15 Further administrative changes may result from a DIBP review of all customs licensing regimes under the Customs Act. In November 2015, DIBP released a discussion paper seeking stakeholder input to deliver improvements in licensing arrangements ‘while ensuring the cost of maintaining the efficiency and integrity of our border is appropriately shared with those who use it’. The objectives of the review included to: assess the efficiency and effectiveness of the current licensing regimes; and recommend whether the current licensing regimes should be retained with improvements/enhancements or replaced. As part of the review DIBP welcomed comments, among other things, on: whether there is unnecessary duplication of systems and communications between the department and the ATO for the clearance of excise equivalent goods; and whether there are inconsistencies in the treatment of excise equivalent goods and excise goods by the department and the ATO. Submissions were due by 31 December 2015.14

1.16 As at 14 March 2016, DIBP advised that submissions have been received from industry and government agencies, with some individual submissions. The department has conducted an initial assessment of the submissions, and consultations with key stakeholders are continuing.

Stakeholder engagement

1.17 Ongoing engagement with stakeholders is conducted through bi-annual meetings of the Tobacco Industry Forum. Chaired by the ATO, it involves key corporate representatives with interests in the tobacco industry, senior staff from the ATO and DIBP along with a range of government departments and industry groups, including the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission.

1.18 Key issues identified at meetings of the Tobacco Industry Forum held in the three year period 2012 to 2014 include: measures to combat the trade in illicit tobacco; reform of the excise system; and compliance activities. Feedback from industry groups on the shift of responsibilities between DIBP and the ATO was predominantly positive, but meeting minutes reflect that further reductions in compliance costs may be achieved through legislative and administrative reform in the excise and excise equivalent goods systems.

The illicit tobacco market in Australia

1.19 Trade in the illicit tobacco market in Australia is a threat to government revenue. The Australian Crime Commission report Organised Crime in Australia 2015, noted that ‘organised crime remains entrenched within the illegal tobacco market in Australia’.15

1.20 Instances of illegal behaviour resulting in substantial loss of revenue have included:

- May 2014: approximately 350 000 mature tobacco plants were seized, with an excise value of $15 million16;

- September 2015: the importation of considerable amounts of illicit cigarettes and tobacco was discovered, with a potential customs duty of approximately $4.77 million17; and

- 16 October 2015: seizure of the largest ever illegal tobacco shipment, 71 tonnes, which would have avoided customs duty of approximately $27 million.18

1.21 DIBP advised that the majority of smuggled tobacco detections occur in the sea cargo environment. The tobacco is concealed and incorrectly described as other commodities to avoid payment of customs duties. In addition, DIBP identifies risks to revenue in the international mail and air cargo environment. An exercise in 2013–14 examining mail coming into Australia, detected approximately 42 million sticks of undeclared tobacco, with an estimated customs duty evaded of over $34 million.19

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.22 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the administration of tobacco excise equivalent goods.

1.23 To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO assessed whether:

- management arrangements between the ATO and DIBP support the effective administration of tobacco excise equivalent goods;

- ATO and DIBP systems and procedures support DIBP’s collection of customs duty for tobacco excise equivalent goods; and

- compliance activities for tobacco excise equivalent goods are appropriate and effective.

1.24 The report did not explicitly cover the administration of tobacco excise, as the production of tobacco and tobacco goods in Australia ceased during 2015, and no excise revenue is expected to be collected from tobacco goods when the stocks of local produce are exhausted later this year. However, tobacco excise was covered indirectly, as there were some common arrangements with excise equivalent tobacco, such as in risk assessments. Similarly, the illicit tobacco market in Australia was not within scope, but was considered in relation to the assessment of risk and compliance activities. While the audit has focused on tobacco, there are common arrangements for the administration of other excise equivalent goods (alcohol and petroleum), and accordingly some of the findings from the audit have application for other excise equivalent goods.

1.25 In conducting the audit, the ANAO: interviewed key ATO and DIBP personnel; reviewed ATO and DIBP documents; visited ATO administered s.79 warehouses and Customs depots administered by DIBP; and conducted analysis of ATO compliance activities.

1.26 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $755 000.

2. Management and reporting arrangements

Areas examined

This chapter examines management and reporting arrangements for the administration of tobacco excise equivalent goods.

Conclusion

Arrangements between the ATO and DIBP for managing tobacco excise equivalent goods and collecting customs duty have been less than effective, with weaknesses in administration and governance practices and visibility in the movement of goods. Established in 2010, arrangements under Memorandum of Understanding processes have achieved some streamlining of regulatory services to industry, but more may have been possible if the (then) Australian Customs and Border Protection Service had more fully supported and engaged with the ATO in carrying out the delegated functions.

The ATO also relies on an inadequate information technology system for the administration of tobacco excise and excise equivalent goods; and the exchange of information between the ATO’s and DIBP’s systems to administer excise equivalent goods is inadequate.

There is limited assurance that the correct amount of tobacco customs duty is being collected and reported, as reconciliation of goods moving through the underbond system is seldom undertaken. Further, there is uncertainty about forward estimates of tobacco revenue, as these estimates do not incorporate a change in supply and demand of dutiable tobacco arising from cheaper illicit product. As at February 2016 the ATO is developing a tax-gap estimate for tobacco that, when complete, should provide an estimate of the value of the illicit market in tobacco, and revenue foregone.

Areas for improvement

From mid-2015, there has been a renewed focus within DIBP on the joint arrangement to manage excise equivalent goods, following integration with the (then) Australian Customs and Border Protection Service; and DIBP has developed the Tobacco Strategy 2015–18 which provides strategic direction to the department’s management of the flow of tobacco across the Australian Border (both licit and illicit). The ANAO has made one recommendation aimed at improving the exchange of information between the agencies (paragraph 2.19). The ANAO also made one suggestion aimed at ensuring the operation of the management arrangement between the agencies is appropriately maintained (paragraph 2.24).

Introduction

2.1 The administration of excise equivalent goods is included in management arrangements between the ATO and DIBP relating to the administration of various taxes, namely the: goods and services tax; luxury car tax; wine equalisation tax; Tourist Refund Scheme; and excise and excise equivalent goods legislation applicable to the import and export of goods. The management arrangements consist of a:

- head Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between the ATO and DIBP that:

- sets out the common provisions for entering into subsidiary arrangements for the exchange of information and other activities between the agencies;

- establishes the membership and objectives of the Inter-agency Liaison Committee and the Operational Sub-Committee that manage the aspects of the relationship relating to the various taxes. The Inter-agency Liaison Committee is accountable to the Secretary of DIBP and to the Commissioner of Taxation;

- subsidiary arrangement—Subsidiary Arrangement, Excise and Excise Equivalent Goods (EEGs)—established under the head MoU; and

- controlled document, the Administration of Excise Equivalent Goods—Roles and Responsibilities (version 3, December 2013), that details the roles and responsibilities of each agency under the subsidiary arrangement (there is no document dealing specifically with tobacco goods).

2.2 Within the ATO, the administration of excisable goods and excise equivalent goods is largely conducted in the Excise Product Assurance branch (within the ATO’s Indirect Tax business line). As at January 2016, the branch was structured around specific functions, for example licensing and compliance, across all commodities. During 2016, the cessation of the production of excisable tobacco goods (and the collection of tobacco excise) will result in some minor adjustments to resource allocation in the branch. Within DIBP, the: Traveller, Customs and Industry Policy Division is responsible for the policy governing excise equivalent goods; and the Customs Compliance branch in the Australian Border Force coordinates and conducts border control and compliance activities.

Do the management arrangements between the ATO and DIBP support the effective administration of tobacco excise equivalent goods?

The administrative framework for managing tobacco excise equivalent goods is sound, providing detailed roles and responsibilities for the ATO and DIBP, and an appropriate committee structure. However, the (then) Australian Customs and Border Protection Service (ACBPS) did not meet the intent of the agreement by sufficiently engaging with or supporting ATO officers. Specifically, DIBP’s decision not to provide ATO officers with the necessary level of access to DIBP’s systems limited the ATO’s ability to administer its roles and responsibilities under delegated powers for almost five years. This may have also limited the extent of the streamlining of regulatory services for industry participants, limited the effectiveness of the selection and conduct of risk and compliance activities for tobacco excise equivalent goods, and reduced the level of assurance that the correct amount of tobacco customs duty was being collected. There is no evidence that the ATO invoked dispute resolution processes set out in the head MoU between the ATO and (then) ACBPS to resolve the issue in a timely way.

From mid-2015, the newly established DIBP (following integration with the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service) has renewed engagement with the ATO to address many long standing issues related to the management of excise equivalent goods. Nevertheless, problems remain in exchanging information between the agencies, and the development of reporting mechanisms would ensure that the Secretary of DIBP and the Commissioner of Taxation are kept informed and provided assurance that the arrangement is being managed effectively.

2.3 The effectiveness of the administration of excise equivalent goods is highly dependent on cooperation between the ATO and DIBP. The head MoU includes that ‘parties will be open, honest, cooperative and responsive to each other, respecting each other’s functions and roles, and providing each other with positive assistance whenever possible’.20 The subsidiary arrangement (for the administration of excise and excise equivalent goods) states that each agency is to ‘mutually assist the other to facilitate the administration of the Program’ (clause 29).

2.4 Irrespective of this requirement, a joint ATO and DIBP assessment, Vulnerabilities in the Administration of Excise Equivalent Goods, April 2014, identified a poor relationship between the agencies and weaknesses in almost all aspects of the functioning of the arrangement. The review identified vulnerabilities across three categories of the administration of excise equivalent goods related to: administration and governance; the visibility in the movement of the goods (including in warehoused goods); and specific legislative and technical matters, including vulnerabilities in exports.

2.5 In March 2015, the ATO prepared an update on priority issues identified from the initial review: Gaps and Vulnerabilities Update. The priority issues varied, with matters ranging from those that could be readily addressed by the agencies, for example the coordination of compliance activities; to systems constraints that would require significant capital investment by either or both agencies to improve functionality. An overview of the issues and their impact, focussing on key points most relevant to the administration of tobacco excise equivalent goods, is provided in Table 2.1.

2.6 Minutes of the Inter-agency Liaison Committee meetings21 reflected that the issues identified in the gaps and vulnerabilities documents had been raised by the ATO on several occasions, but mostly remained unresolved. Specifically, the issue of ATO staff having appropriate access to DIBP’s ICS was still outstanding as at the meeting of 16 September 2014, more than four years after the administration of excise equivalent goods was delegated to the ATO. The minutes recorded acknowledgement that an ATO officer acting under delegation should have the same system access profile as those in the (then) ACBPS doing the same function; and lack of access was inhibiting resolution of some of the vulnerabilities identified in the administration of excise equivalent goods. However, (then) ACBPS advised that ‘the ACBPS does not agree with some of the ATO views on ICS access and it has not yet received from the ATO a persuasive case for any changes to ICS access arrangements’.

Table 2.1: Overview of issues relevant to administration of tobacco excise equivalent goods outlined in the Gaps and Vulnerabilities Update, March 2015

|

Priority issue |

Impact |

|

Information sharing and protocols |

The exchange of information between DIBP and the ATO is ad hoc, with no formal agreed and documented processes including for: the establishment of client profiles in DIBP’s ICS; and data exchange of licensing information. |

|

Lack of coordinated compliance activities in warehouses |

An entity may be able to exploit checks undertaken by both agencies by moving goods between depot and warehouse to appear compliant according to whichever agency is undertaking a check. |

|

Handover points |

There is no electronic visibility as to when responsibility for goods transfers from DIBP to the ATO. |

|

Export vulnerabilities |

The movement of excise equivalent goods underbond within the export environment provides opportunities for the diversion of these goods into home consumption. The risk of unauthorised movement, alteration or interference with export cargo is high—given that opportunities and timeframes available for examination are limited. |

|

Restricted ATO ICS access |

The time taken for DIBP to approve access to ICS for new ATO staff, and restrictions placed on ATO staff access to the system limits the ATO’s ability to administer excise equivalent goods. |

|

Licensing |

Differences in warehouse licensing conditions imposed by the ATO and DIBP on the warehouses for which they are responsible affect the analysis and management of risk. There has been no systematic joint annual review of licensed warehouses since 2012 to confirm the appropriate agency has responsibility, although there has been informal liaison between the agencies. |

Source: ANAO from the ATO’s Gaps and Vulnerabilities Update.

2.7 Minutes from the Operational Sub-Committee reflected similar issues.22 The original intent was that the meetings would be held monthly, becoming less frequent as arrangements for the administration of excise equivalent goods were fully implemented. As illustrated in Table 2.2, the frequency of the meetings reduced although matters relating to the administration of excise equivalent goods remained outstanding: for example, the lack of ATO access to ICS was raised in March 2014 and again in February 2015, when there was discussion about the continuing lack of visibility by the ATO of export permissions recorded in ICS. As at January 2016, the last meeting of the Operational Sub-Committee was held in September 2015.

Table 2.2: Frequency of the Operational Sub-Committee meetings

|

|

2010 (from August) |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

|

Number of meetings |

4 |

10 |

6 |

4 |

2 |

2 |

Source: ANAO from ATO minutes.

2.8 Advice from DIBP is that (then) ACBPS did not meet the expectations or intent of the arrangement with the ATO, with respect to the administration of excise equivalent goods. Irrespective of the development of detailed roles and responsibilities for each party, the (then) ACBPS and the ATO were unable to resolve issues—through the committee structure—in the governance and operation of the delegated functions for many years.

2.9 These administrative shortcomings may have limited the extent of the streamlining of regulatory services for industry participants; limited the effectiveness of the selection and conduct of risk and compliance activities for tobacco excise equivalent goods; and reduced the level of assurance that the correct amount of tobacco customs duty was being collected.

Dispute resolution

2.10 The head MoU (between the ATO and DIBP) includes (clause c3) ‘the parties must attempt to resolve any dispute concerning the Arrangement by negotiations at an operational level’ and where those negotiations fail to resolve or determine specific outcomes, the matter should be referred upwards, through the parties’ equivalent management levels, until resolved. The Terms of Reference for the Inter-agency Liaison Committee includes that the committee is accountable to the Secretary of DIBP and to the Commissioner of Taxation; and that, ‘If a matter is unable to be resolved after a reasonable period, then that matter should be referred to the Commissioner and the CEO to resolve as they consider appropriate’.

2.11 The head MoU (paragraph 4) also requires each party’s MOU manager to provide a brief annual report on the operation and progress of the agreement and subsidiary arrangements to the Inter-agency Liaison Committee. These reports have never been completed for excise equivalent goods, with the ATO and DIBP advising that the annual Certificate(s) of Assurance (prepared by the ATO for DIBP) and meetings of the Inter-agency Liaison Committee satisfied this requirement. The Certificate(s) of Assurance, however, deal only with the ATO’s acquittal of its financial responsibilities under the delegation of powers.

2.12 While the Inter-agency Liaison Committee membership includes executive staff at senior levels in each organisation, there is no evidence that concerns were escalated to the Secretary of DIBP or to the Commissioner of Taxation; and reports on the progress of the arrangement for excise equivalent goods were not prepared. As such, weaknesses in the system—which accounts for an average $5.5 billion in revenue each year, including an average $3.2 billion in tobacco goods—remained unresolved for almost five years.

Arrangements going forward

2.13 Minutes of the Inter-agency Liaison Committee meeting of 8 April 2015 record a more positive approach, with DIBP advising that the relevant division of the department ‘will help ensure that the outstanding gaps and vulnerabilities are addressed, with a person allocated to each of the outstanding issues’.23

2.14 A joint ATO/DIBP operational level meeting to progress resolution of the gaps and vulnerabilities was held on 15 October 2015; with two ATO staff being given DIBP-level access to ICS in early November 2015, to test if this would resolve data visibility issues for the ATO. DIBP advised that if this is successful, this level of access will be provided to all relevant ATO staff as an interim solution, while the ATO specific profile is amended. DIBP has also developed the Tobacco Strategy 2015–18 (dated November 2015), which provides strategic direction to the department’s management of the flow of tobacco (both illicit and legally imported) across the Australian border.

2.15 The dispute resolution process set out in the terms of reference for the Inter-agency Liaison Committee, and reporting requirements included in the head MOU, were not implemented. Issues now being addressed to improve the administration of tobacco excise equivalent goods should have been resolved as they arose, rather than some five years after the delegation of powers to the ATO. Ongoing assurance that the arrangement is being managed effectively would be supported through the development of formal reporting mechanisms to the Secretary of DIBP and to the Commissioner of Taxation, following the bi-annual meetings of the Inter-agency Liaison Committee.

Information technology systems supporting the administration of excise equivalent goods

2.16 Information technology (IT) systems in both agencies are also fundamental to the administration of excise equivalent goods. All aspects of the administration of excise equivalent goods relies on information held in DIBP’s ICS, but is managed on a day-to-day basis through the ATO’s systems, namely the:

- Excise Collection System: a stand-alone ATO custom-built legacy system (using a Microsoft Windows 2003 platform). The system is out-dated, no longer supported by Microsoft, and has passed its decommissioning date;

- Siebel: an enterprise level system used to manage cases and work items;

- Integrated Core Processing: a new ATO system platform for many of the ATO’s business processes;

- ATO Integrated System: a legacy system that is used for the ATO’s accounting and transactional processes; and

- Data Warehouse: the central repository of integrated data sourced from multiple systems.

An overview of the arrangement is shown in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Information technology systems for the administration of excise equivalent goods [click for larger version]

Source: Developed by the ANAO in consultation with the ATO and DIBP.

2.17 The IT arrangement is complex and unwieldy. There is a lack of direct system interfaces supporting the information exchange between DIBP’s ICS and the ATO’s Excise Collection System; and between the ATO’s various systems. The arrangement relies heavily on manual intervention, including data entry (at times including double entry into multiple systems), and email correspondence to maintain the accuracy and currency of information. For example, the creation of an establishment code in ICS (for licensing purposes) requires an email exchange between an ATO licensing officer and a DIBP officer, and manual updates to computer systems in both agencies.24

2.18 The arrangement has developed with the transfer of the administration of excise equivalent goods to the ATO, aimed to streamline services to taxpayers. However, taxpayers still have to engage with both agencies, and the data exchange ‘loop’ through the ATO to DIBP’s ICS is far from efficient. The situation has been further exacerbated by DIBP’s reluctance in the first five years of the arrangement to provide ATO officers (effectively acting as DIBP or ‘customs officers’ under the delegated powers), the necessary access to ICS (as discussed earlier in this paper).

Recommendation No.1

2.19 To support the administration of excise equivalent goods, the ANAO recommends that:

- the ATO reviews and, subject to competing information technology priorities, improves the information technology platform currently in use; and

- DIBP and the ATO improve the exchange of information between the respective agencies.

ATO response: Agreed.

2.20 The ATO supports this recommendation. Our Reinvention Program has examined the excise system in use. Improvement opportunities have been identified and are being considered as part of our planning and prioritisation processes. The ATO is piloting additional access recently granted by DIBP to its Integrated Cargo System.

DIBP response: Agreed.

2.21 The Department supports this recommendation and is progressing the work necessary to provide the following to the ATO:

- Additional data fields in the automated nightly data upload to the ATO systems.

- An interim solution for increased Integrated Cargo System access while system changes are developed in the longer term to increase the level of visibility within the system for delegated officers within the ATO.

- A greater level of ad hoc information exchange through a closer working relationship, particularly in the joint operational space.

Is the correct amount of customs duty collected and reported?

There is no calculation or reconciliation that provides assurance that the correct amount of customs duty is being collected and reported:

neither the ATO nor DIBP examines the value of the charges due from the physical quantities of imported tobacco goods moved into the underbond system, and the actual volume of these goods (and customs duty paid) reported entering the domestic market;

revenue (excise and customs duty) collected from tobacco goods is reported in Australian Government Budget documents, against forward estimates based on projected consumption (that include assumptions about fluctuations in demand, for example due to increases in excise rates). The assumptions do not factor in the size of the illicit trade in tobacco and potential changes to the supply of and demand for dutiable goods as a result of the increase in costs in the legitimate market; and

the size of the trade in illicit tobacco (and value of revenue lost) has been the subject of much analysis, but the various results have not been agreed by key government and industry stakeholders. As at February 2016, the ATO was developing a tax-gap estimate for tobacco that will provide an estimate of the value of the illicit tobacco market and resultant revenue foregone.

2.22 The ATO is responsible for the collection and reporting of excise, and DIBP for customs duty. The ATO provides a monthly Financial Summary Reconciliation Report to DIBP on the revenue collected on DIBP’s behalf (not specific to commodity).25 DIBP could not provide any information on how, or whether, the report is used. DIBP provides the ATO with its monthly (so-called) ‘alcopops’26 report, which includes data on the quantity and duty value for excise equivalent goods extracted from the ICS for each commodity, with the ATO advising that the agency has little or no use for the report.

Reconciliation of excise equivalent goods underbond

2.23 Effective control of the warehousing and movement of excise equivalent goods ensures there is no ‘leakage’ of goods and avoidance of customs duty, through for example: theft from a warehouse or when the goods are in transit; damaged goods not being destroyed; or goods being moved into the illicit market. Warehouse operators are liable for the payment of customs duty on goods that cannot be accounted for, and the ATO advised that the risk of ‘leakage’ is limited to smaller operators whose warehouses are not equipped with technology to track the movement of all goods. There are also constraints in the wording of licences that limit the identification of goods stored in some s.79 warehouses administered by the ATO, further discussed in Chapter 3.

2.24 Irrespective of the goods tracking systems in larger warehouses, with regard to excise equivalent goods, there are weaknesses in the agencies’ capacity to: control the movement of excise equivalent goods (identified in the ‘gaps and vulnerabilities’ document); and to reconcile the volume of goods recorded in N20 Declarations (when excise equivalent goods enter a warehouse) and N30 Declarations (when excise equivalent goods are released into home consumption). The gaps and vulnerabilities document identified that monitoring and analysis capability for the purposes of risk assessment and targeting was undermined because of the inability to cross match events pertaining to the movement of cargo.

2.25 The ATO advised27 that a reconciliation (of N20s and N30s) is technically possible, but is resource intensive (requiring a physical stocktake of goods located in a warehouse), and seldom done. Essentially, the operation of the underbond system, where goods may be moved between several licensed warehouses, the deferment of customs duty until the goods are released into home consumption, and tracking of goods that may be damaged and customs duty is not payable, makes regular and accurate reconciliation of goods through the underbond system difficult to achieve. Irrespective of these difficulties, the absence of such reconciliations limits the effectiveness of risk and compliance activities, further discussed in Chapter 4.

Actual and forecast tobacco revenue

External reporting

2.26 Neither the ATO nor DIBP include in their annual reports, the amount of excise or customs duty collected by commodity—each agency reports the combined amount of revenue (that is excise or customs duty respectively) associated with petroleum, alcohol and tobacco excisable goods and excise equivalent goods.28 Similarly, there is no reference in either agency’s Corporate Plan to responsibilities or prospective revenue in relation to excise or customs duty.29

2.27 Commencing in 2013–14, revenue raised from tobacco goods (combined excise and customs duty) is reported in Australian Government Budget documents.30 The Budget Papers report the tobacco revenue outcome for the most recent completed year, an estimate for the current year, forecasts for the next two years and projections for a further two years. Actual and forecast revenue for the six year period 2013–14 to 2018–19 is set out in Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2: Actual and forecast tobacco revenue, 2013–14 to 2018–19

Source: ANAO, from Australian Government Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook statements, 2013-14 to 2015-16.

2.28 Revenue forecasts are based on estimates of the consumption of legitimate tobacco products, which allow for assumptions about fluctuations in demand due to policy changes, such as increases in excise rates. The current revenue forward estimates reflect a slower rate of growth in revenue, as increased excise rates are off-set by a reduction in demand. The forecasts do not allow for changes in the supply of and demand for illicit tobacco, as the price (of the legitimate product) increases.

Estimating the tobacco excise tax gap

2.29 The ATO has publicly committed to estimating the tax gap for all the taxes it administers.31 A ‘tax gap’ is defined as the difference between the estimate of tax theoretically payable (assuming full compliance by all taxpayers) and the amount actually reported or collected for a defined period. A tax gap can result from actions that are deliberate, careless or unintentional. From 2012, the ATO has published tax gap estimates relating to the goods and services tax and the luxury car tax.

2.30 In 2014–15, the ATO released tax gap estimates for: the wine equalisation tax; excise and customs duty (for petroleum, diesel, and beer); ‘pay as you go’ withholding; and fuel tax credits; and, as at 25 August 2015, has refreshed the estimates for the goods and services tax and luxury car tax. As at February 2016, the ATO advised that it is developing a tax gap analysis for tobacco, with DIBP seeking executive endorsement to progress the work jointly with the ATO. The inter-departmental team would explore multiple ways to measure the size of the illicit tobacco market—with a subsequent conversion to an excise and customs duty amount. Subject to its credibility and reliability, the ATO intends to release a tax gap estimate for tobacco in its 2015–16 annual report.

3. Licensing s.79 warehouses administered by the ATO

Areas examined

This chapter examines the arrangements for issuing and renewing licences to operate s.79 warehouses administered by the ATO, which can store (among other excise equivalent goods) excise equivalent tobacco.

Conclusion

The licensing regime for s.79 warehouses administered by the ATO could be improved. The ATO has developed little specific guidance and process documentation, instead applying existing excise guidance to s.79 warehouses under its administration. The ATO has recently amended the wording on licences to clearly identify the goods that can be stored in a warehouse, but there is scope to improve other aspects of the processing of licence applications and renewals.

Areas for improvement

To support the administration of the licensing regime for s.79 warehouses administered by the ATO, the ANAO has recommended that the ATO develops specific guidelines and procedural documentation for the warehousing of excise equivalent goods (paragraph 3.5). The ANAO has also suggested that the ATO: assesses the results of its revised policy to not conduct criminal history checks of new employees of large companies (paragraph 3.16); ensures that a new checklist covers all legislative and policy requirements for issuing a warehouse license (paragraph 3.19); and reviews the extent of quality assurance checking in relation to licensing (paragraph 3.27).

Has the ATO developed procedural guidance for the licensing of s.79 warehouses?

The ATO has applied excise licence policy and process to excise equivalent licences, although the licences are issued under different legislation—the Excise Act 1901 and the Customs Act 1901 respectively, and no analysis of the requirements of the Acts has been conducted. With regard to tobacco, the ATO has focused on the administration of excisable goods, although the cessation of the tobacco industry in Australia (and a corresponding increase in revenue from customs duty) has been foreshadowed for several years. The ATO could have been more active in its administration of licensing for s.79 warehouses under its administration.

3.1 The requirement for industry to apply for and to renew licences for premises where excise and excise equivalent goods may be manufactured and/or stored is an important regulatory mechanism in the administration of these goods.32 In 2009, in a policy review of licensing decisions, the ATO described licensing as a cornerstone of the regulation of excise products. All applications for a licence, or to renew a licence to manufacture and/or store excise and excise equivalent goods, are managed by the licensing team within the ATO’s Indirect Tax business line, utilising the ATO’s Excise Collection System and DIBP’s ICS. As previously illustrated in Figure 2.1, the exchange of data between the ATO’s and DIBP’s systems for licences issued under the Customs Act is not streamlined, relies on manual input, and was identified as a weakness, among other aspects of the administration of these licences, in the gaps and vulnerabilities documents.

3.2 As at 1 December 2015, the ATO administered a total of 1682 licences related to the manufacture and/or storage of excisable goods held by 895 clients; and 324 licences for ATO administered s.79 warehouses to store excise equivalent goods, held by 155 clients. The licences are issued under different Acts, the Excise Act and the Customs Act respectively, and have different application forms and licences.

3.3 The ATO provided a number of Excise Practice Notes33 dealing with the licensing process and the issuing of movement permissions (relating to the movement of excisable goods). There were no similar documents dealing with the administration of licences for s.79 warehouses administered by the ATO; and there is no reference or additional notes (relating to s.79 warehouses or excise equivalent goods) in any of the excise related documents provided.

3.4 The ATO advised that: in the absence of specific licensing guidance from DIBP, the same or similar approach is applied to all licenses, as they consider the core criteria is essentially the same (for excise and excise equivalent goods). However, the excise and excise equivalent goods systems are administered under different Acts, and there was no evidence that the ATO had analysed the requirements under each Act to support the decision to apply common procedures to both licensing regimes. The cessation of excise tobacco in Australia adds further impetus for the development of guidance and procedural documentation for the warehousing of excise equivalent goods, including engagement with DIBP to improve the process.

Recommendation No.2

3.5 To support the issuing and renewal of licences for operators of s.79 warehouses administered by the ATO, the ANAO recommends that the ATO develops specific guidelines and procedural documentation for the administration of s.79 warehouses under ATO control.

ATO response: Agreed.

3.6 The ATO supports this recommendation. Our Practice Notes are currently being reviewed to strengthen this aspect.

DIBP response: Agreed.

3.7 The Department supports this recommendation and will provide the ATO with the required support and advice as the ATO develops the recommended framework.

Is the process effective for issuing and renewing s.79 warehouse licences administered by the ATO?

The process for issuing and renewing a licence to operate a s.79 warehouse administered by the ATO could be improved. The ATO has changed the wording on licences to more clearly identify the goods that may be stored in a warehouse, and is developing a new checklist for the application process, but more could be done. The number of criminal history checks on licence applicants has been reduced, but the ATO has not analysed the impact of this on incidences of non-compliance.

3.8 The ATO’s licensing process for s.79 warehouses, as at November 2015, is set out in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1: Licensing process for s.79 warehouses administered by the ATO, as at November 2015

Note 1: Warehouses assessed as at higher risk (of non-compliance), or applicants applying for their first warehouse license, may be required to provide a financial security bond.

Source: ANAO, based on information provided by the ATO.

3.9 The ANAO examined four elements of the process: the conduct of criminal history checks; the use of process checklists; recording of licence application decisions; and the wording in licences. The ANAO also examined the ATO’s quality assurance processes for licensing decisions.

Conducting criminal history checks

3.10 Prior to July 2009, the ATO routinely conducted criminal history checks on all applicants for a licence to manufacture and/or store excisable goods, in assessing if the applicant (or an associate) was a ‘fit and proper person’ to hold a licence.34 Between December 2006 and July 2009, the ATO conducted over 800 criminal history checks. From January 2011 to November 2015, the ATO completed a total of 158 criminal history checks for licence applications for s.79 warehouses under its control.

3.11 Since 2009, the ATO has made several changes to the policy for conducting criminal history checks, set out in Table 3.1.

3.12 The ATO provided two policy documents relating to these changes: in July 2009 and in December 2013.

Policy change, July 2009

3.13 An ATO minute, Use of Criminal History Record Checking in Licensing Decisions, 6 July 2009, provides the rationale for moving to a risk based approach for the conduct of these checks, based on the premise that:

- since December 2006, over 800 CrimTrac searches had been undertaken, with 53 individuals found to have a criminal history, but none of the checks had resulted in the refusal to grant or to cancel a licence. Anecdotal information indicated that in the two years, the results of a CrimTrac check did not influence a licensing decision; and

- the cost of CrimTrac searches had been over $18 000 since 2006 (around $23 per check). Direct administration of the process accounted for approximately 0.15 full time equivalent staff, with additional ‘large amounts of extra time spent by licensing officers on obtaining forms and appropriate POI [proof of identity] from clients before CrimTrac checks can be lodged’, adding to the regulatory burden to applicants, and some delay in processing the licence application.

The document also notes the deterrent effect of asking applicants or their associates to complete a Consent to obtain information form, and that the practice should continue as it ‘provides Licensing with some insight about the applicant (albeit self-assessed) and is a low cost to the client and Licensing’.35

Policy change, December 2013

3.14 The December 2013 policy document provided to the ANAO, Excise Act Policy—Requirement to Undertake Criminal History Checks, is not on an official form, is undated and does not refer to any authorising or responsible officer.

Table 3.1: ATO policy for criminal history checks in the licensing process

|

Year |

Licences for warehouses for excisable goods |

Licences for s.79 warehouses administered by the ATO |

|

Pre-July 2009 |

Criminal history checks conducted on all applicants. |

N/A |

|

2009 |

Excise policy document implemented, changes include criminal history checks conducted on a risk-based framework. |

N/A |

|

2010 |

As above. |

Due to a lack of guidance from DIBP, ATO adapted the excise criminal history check policy to excise equivalent goods warehouse licences. Criminal history checks were carried out on all new excise equivalent goods licence applicants while existing licence holders were checked on a risk basis. |

|

2013 |

The 2009 excise policy document was updated. Criminal history checks included the following exemptions: low risk industries and government applicants. |

The criminal check process for excise equivalent goods licences remained. While the updated excise policy did not formally apply to excise equivalent goods licence applications, it was still used as a basis for existing licence holders. |

|

November 2013 |

As above. |

In November 2013, new legislation was introduced that included additional criteria for fit and proper checks. The changes meant that criminal history checks and aviation or maritime security identification card checks had to be carried out on all new applicants. Existing licence holders remained checked on a risk basis. |

|

2015 |

The existing policy on criminal history checks for excise licence applications was withdrawn and all checks were carried out on a risk assessed basis, irrespective of whether the applicant was new to excise or an existing licence holder. |

As above. |

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO documents. Table developed in cooperation with the ATO.

3.15 The ATO advised that the policy applies to fit and proper person checks undertaken under the Excise Act, and has been adopted for excise equivalent goods. The policy provides a list of exemptions for the further conduct of criminal history checks, limiting the checks to entities identified as a ‘high risk’ (though no criteria for this risk are included in the document).36 The policy also negated the need for entities exempt from a criminal history check to complete Consent to obtain information forms.37

3.16 The new policy significantly reduces the number of criminal history checks carried out, specifically for large entities, and negates any deterrent effect of the requirement to complete a consent form. The ATO advised that the criminal history checks have been reduced for large entities as those entities conduct their own criminal history checks. However, there was no advice available as to how the ATO verifies that these checks are being conducted. In this light, the ATO could assess the results of this change in the policy for conducting criminal history checks, including considering any increase in the incidence of warehouse operators’ non-compliance with the requirements of their licence.

Developing a new checklist for processing warehouse licence applications

3.17 In September 2015, the ATO commenced a limited trial of a new checklist to support the processing of applications for all licensed warehouses under its control. Subject to the trial, when fully developed and implemented, the new checklist is intended to replace the separate excise/excise equivalent checklists currently in use (irrespective of the commodity or commodities to be stored). The checklists include consideration of the: physical security of the warehouse, for example the adequacy of security measures; value of goods to be stored; and insurance held by the applicant (for loss or damage to the stored goods). The new (combined) checklist requires more detailed responses, with officers providing written comments against specific ‘checks’—rather than the previous ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response with optional comments—and a written evaluation of the decision.

3.18 The checklist being trialled also reflects legislative changes to the warehouse licensing regime, (including for s.79 warehouses administered by the ATO) introduced by the (then) ACBPS in February 2014.38 The changes are outlined in Table 3.2.

Table 3.2: Legislative changes to the warehouse licensing regime, February 2014

|

Amendments to the Customs Act 1901 |

What the changes mean |

|

Additional criteria for ‘fit and proper person’ tests. |

The Secretary of DIBP, or the delegate, must now consider whether a person has been refused an aviation or maritime security identification card or had it suspended or cancelled in the previous 10 years. |

|

Additional notification requirements for a warehouse licence holder. |

Holders of a warehouse licence must notify the Secretary of DIBP, or delegate, where the licence holder or partners have had an aviation or maritime security identification card refused or cancelled, within 30 days. |

Source: Australian Border Force.

3.19 The ATO advised that these requirements were implemented but, as at December 2015, they are not reflected in the checklist currently in use for s.79 warehouses administered by the ATO; and the ATO was unable to advise how compliance with the additional notifications for licence holders was verified. The ATO subsequently provided an updated version of the (combined) checklist (updated 28 January 2016) reflecting that checking the status of an applicant’s maritime or aviation security card should be undertaken on a risk assessed basis (but did not provide information on relevant risk criteria). The ATO could ensure that the new checklist, including the recent update on the status of maritime or aviation security cards, meets all legislative and policy requirements for issuing a license.

Recording licence application decisions and renewals

3.20 The ATO maintains a record of new warehouse licences for excise and excise equivalent goods granted each year (including those that are required to pay a security deposit). Where a licence application is refused, the ATO must provide the applicant with the reason for the refusal, including that the decision can be appealed.

3.21 Since 2010, the ATO has not refused any applications for a s.79 warehouse licence and has requested 111 security deposits. A number of these security deposits were to replace those previously held by DIBP prior to the change in administration, and some have since been returned. Over the same period, there has been one appeal of a decision to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal that was not in relation to granting or refusing a s.79 licence but to a variation of licence conditions.

3.22 For annual s.79 warehouse licence renewals, the ATO sends licence holders a notification six weeks prior to expiration of their licence. In most cases, once payment is received by the ATO, the licence is renewed. The ATO advised that there are a number of instances where a renewal application will undergo a review, for example: where compliance issues have been identified; there has been a change of key warehouse staff members; or the licence holder is selling the business. The ATO could not provide advice on how many renewal applications had been reviewed and the outcome of the reviews.

Changing the wording in licences for s.79 warehouses administered by the ATO

3.23 In 2010, the ATO identified an anomaly in the wording of s.79 warehouse licences when the administration of these licences was transferred from the (then) ACBPS. Ambiguity in the wording of the licences meant the ATO could not readily identify the type(s) of excise equivalent goods that could be stored in s.79 warehouses under its administration, as shown in Table 3.3, and has taken steps to amend the wording.

Table 3.3: Wording of licences for s.79 warehouses administered by the ATO

|

Previous wording on a licence to store tobacco excise equivalent goods |

New wording on a licence to store tobacco excise equivalent goods |

|

Goods subject to Customs control excluding petroleum and like products. |

Goods subject to Customs control being tobacco and tobacco products. |

Source: ANAO from ATO documents.

3.24 Effectively, the warehouse licence holder for tobacco goods could store both alcohol and tobacco products. The ATO changed the wording for all new licences issued from 2010, but did not apply this change to licence renewals until November 2015. As licences are renewed, licence holders are now required to complete a stocktake of the goods stored in the warehouse, and the ATO determines that the licence is appropriate and the wording on the licence specifies the goods that can be stored.

3.25 Over a 12 month period (as licences are annually renewed), the ATO is to establish an accurate list of the type of goods that warehouse licence holders are permitted to store, providing essential information for compliance purposes. Until this is completed, the ATO has limited visibility of the types of goods licence holders are permitted to store in s.79 warehouses that it administers.

Conducting quality assurance on licensing decisions

3.26 The ATO’s licensing process requires that the recommendation (to grant or refuse a license) of the officer assessing a new licence application must be reviewed and approved or disallowed by a more senior delegate (this instruction is included in the new licensing checklist being trialled). Commencing in the December 2014 quarter, licensing decisions were included in the ATO’s corporate quality assurance process, the ATO Quality Model, as applied in the Indirect Tax business line.

3.27 A review of the four quarterly reports on the quality assurance testing in the Indirect Tax business line, between December 2014 and September 2015, showed that licensing decisions were not always specifically considered, but opportunities for improvement were identified. For example, scope to improve recordkeeping processes were identified to provide clear reasons behind a decision, and to improve licensing processes cases were subsequently moved to a new case management system. The ATO advised that there was no distinction between excise and excise equivalent goods licence cases examined in the quarterly reports, and the QA process was not applied to license renewals. The ATO could review the extent of its quality assurance activities in relation to licensing, to ensure that an appropriate level of assurance is provided.

4. Risk and compliance

Areas examined

This chapter examines the ATO’s and DIBP’s management of the risk associated with tobacco industry participants’ non-compliance with their obligations in relation to excise equivalent goods and customs duty liabilities, and the ATO’s and DIBP’s conduct of compliance activities.

Conclusion

The risk associated with the administration of tobacco excise equivalent goods has not been consistently assessed over the previous five years, with no clear rationale for the fluctuation in annual risk ratings. The ATO and DIBP could more effectively work together to analyse factors influencing risk.

The planning and conduct of compliance activities for tobacco excise equivalent goods stored in s.79 warehouse administered by the ATO could be improved, including by greater engagement with DIBP. Within the ATO, there is a lack of process for selecting warehouses for targeted compliance activities, and the recording of completed compliance activities could be improved.

Area for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at improving the assessment of risk that would subsequently support more effective selection and targeting of compliance activities (paragraphs 4.13 and 4.34).

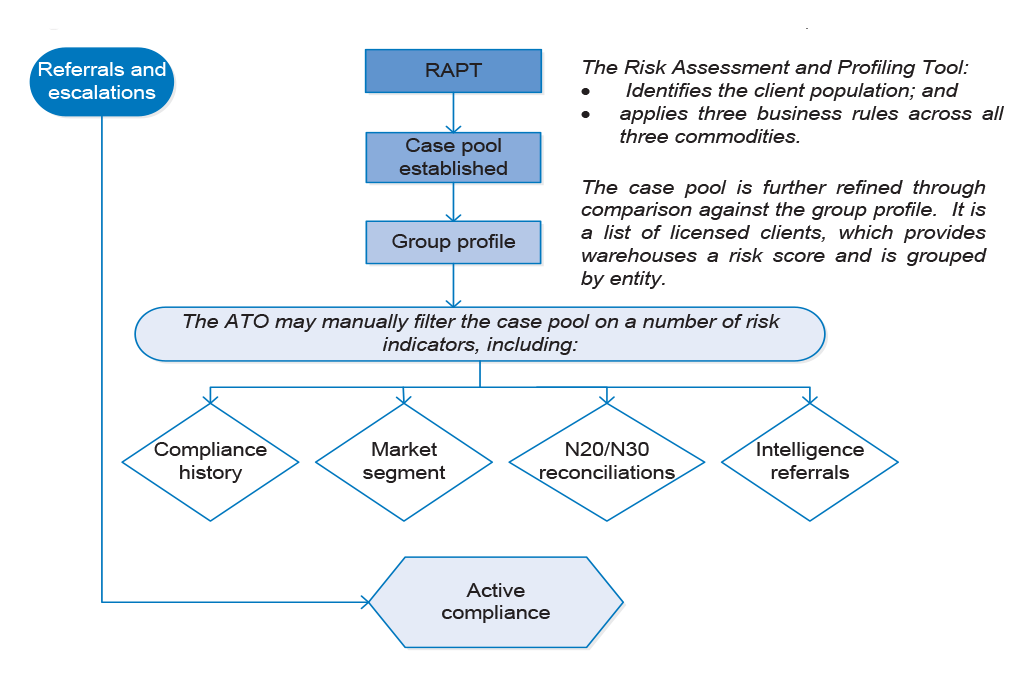

Are risks associated with tobacco excise equivalent goods effectively assessed?

Risks associated with the administration of tobacco excise equivalent goods have not been consistently assessed. Fluctuations in the annual risk rating (from ‘low’ to ‘moderate’ to ‘significant’) lacked a clear rationale, with the most recent rating based on reputational risk to the ATO and DIBP. The shared administration of this risk between the ATO and (then) Australian Customs and Border Protection Service has been ad hoc and informal. There has been little evidence that the expectations of the relationship have been met regarding access to and the timely exchange of: knowledge and expertise of risk staff; and risk-related information, both ongoing and as part of the annual risk management process within each agency.

4.1 Customs duty is calculated and collected under a self-assessment regime, where industry participants are expected to comply with the laws and regulations regarding the importation and sale of excise equivalent goods, and to pay their customs duty liabilities. Assessment of the risk of taxpayers’ non-compliance and targeted compliance activities aim to provide assurance that taxpayers are meeting their obligations.