Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of the Taxation of Personal Services Income

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Taxation Office’s administration of the personal services income regime.

Summary

Introduction

1. The personal services income (PSI) regime is one of many taxation measures administered by the Australian Taxation Office (ATO), Australia’s principal revenue collection agency with responsibility for administering Australia’s taxation and superannuation systems. In 2011–12, the ATO collected $301 billion in net revenue from taxpayers, working within a departmental operating budget of $3.4 billion and with over 24 700 staff.1

2. PSI is defined by Part 2–42 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 as income gained mainly as a reward for the personal efforts or skills of an individual. This excludes income: earned as salary by employees; from supplying or selling goods; from income‑producing assets; or generated by a business structure. PSI is most typically earned by contractors, consultants and sole practitioners, and in 2010–11, the majority (59 per cent) of these worked in administrative and support services; professional, scientific and technical services; and the construction industries.

3. The alienation of PSI legislation (PSI rules) was introduced on 1 July 20002, after the 1999 Review of Business Taxation (known as the Ralph Report) found that taxpayers ‘alienating’ PSI by interposing a company, partnership or trust between themselves and the person paying for the services presented a threat to the income tax base.3 These arrangements created opportunities to reduce taxation liabilities by splitting income with other individuals (such as a spouse), claiming work‑related tax deductions not otherwise available to an individual, and/or tax deferral. It was estimated at the time that the new regime would raise $1.4 billion in additional revenue in its first four years of operation4, mainly by reversing the trend of wage and salary earners accessing the business tax system to gain tax advantages. The revenue estimate was revised in 2001, calculating that the PSI regime would raise $2.3 billion over the first six years of operation.5

4. The PSI rules are intended to tax income earned from personal services in a broadly similar way to the income of people who are employees, and to not impact on genuine business undertakings. The legislation introduced five tests6 to enable entities to self‑assess whether the PSI rules apply to them before submitting their tax return. The tests are designed to determine the nature of the income‑producing relationship and specifically if an entity is operating as a business (known as a ‘personal services business’7), and therefore not subject to the PSI rules.8 Taxpayers can also apply to the ATO for a determination9 of their personal service business status.

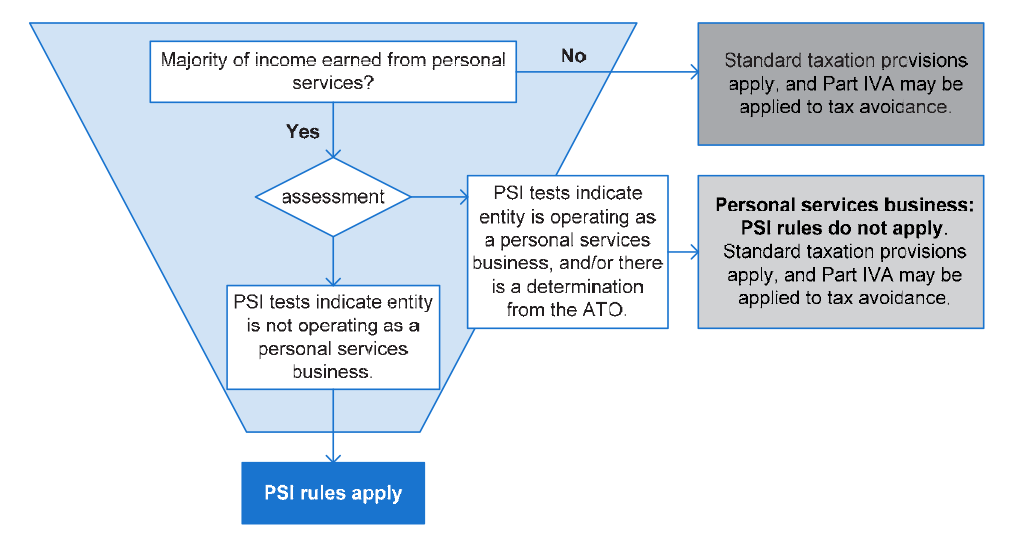

5. Prior to the introduction of the PSI rules, the Commissioner of Taxation (the Commissioner) had to rely on the general anti‑avoidance law for income tax (Part IVA10) to counter alienation of PSI. However, some taxpayers consider that the structure of the PSI rules has created complexity and uncertainty, particularly in how Part IVA now interacts with the PSI regime. Taxpayers who are assessed (through self‑assessment or determination) as personal services businesses are not subject to the PSI rules and instead, standard taxation provisions apply (including potentially Part IVA). This situation is summarised in Figure S.1.

Figure S.1: Interaction between the PSI rules and standard taxation provisions

Source: ANAO interpretation of information provided by the ATO.

6. Two external reviews of the PSI rules have been conducted. In 2009, the Board of Taxation suggested a range of legislative options for improving the integrity and simplicity of the PSI regime, as it noted: poor compliance by taxpayers with the PSI rules; the ATO’s difficulty in monitoring compliance due to an absence of data on the taxpayers who should be reporting; and the level of uncertainty for taxpayers in applying the PSI rules to determine their personal services business status. This review was submitted to the Australia’s Future Tax System Review (the Henry Review), and in 2010, the Henry Review agreed and further considered that the PSI rules were complex and uncertain, and recommended consideration be given to a revised regime. There has been no formal government response to this recommendation.

Administration of the personal services income regime

7. When introduced in July 2000, the administration of the PSI regime was managed by a project team of around 120 staff within the ATO. Over time, staff numbers reduced to around 10 in 2004–05, and the level of staffing has been relatively constant since transition to the Micro Enterprises and Individuals (ME&I) Business Line.11 In 2012–13, there were approximately 6.1 full time equivalent staff allocated to PSI activities, and the cost of administering the PSI regime was estimated by the ATO at just over $784 000. The PSI regime is only a small proportion of the overall activity undertaken by the business line, which had 2273 full time equivalent staff and an operating budget of $216.7 million as at June 2013.

8. Understanding taxpayer behaviour, and what motivates people to comply with their taxation obligations, is the basis of the ATO’s approach to managing compliance. Compliance activities undertaken for the PSI regime follow the ATO’s compliance model.12 Initially the focus was on education and liaison with taxpayers and industry associations, but particularly with tax practitioners, as the ATO estimated that around 90 per cent of taxpayers who earned PSI used a tax practitioner to lodge their returns. Current activities include: educational information aimed at making compliance easier for taxpayers and tax practitioners; interpretive assistance on general or specific topics; targeted letter campaigns aimed at informing taxpayers and tax practitioners of their obligations; and compliance reviews and audits for investigating non‑compliance.

Reporting personal services income taxation revenue

9. At the time of preparation of this report, the ATO’s PSI data was limited to taxpayers who declare themselves subject to the PSI regime. In 2011–12, ATO data indicated that 462 824 taxpayers declared the receipt of PSI income and, of these, 328 261 were assessed as personal services businesses and therefore exempt from the PSI rules. The remaining 134 563 entities, for whom the PSI rules applied, reported $3.1 billion in net PSI.

10. Recent changes to PSI reporting will provide the ATO with further data sources for detecting potential non‑compliance, and improve the quality of the data reported. Mandatory annual reporting requirements for certain businesses that make taxable payments to contractors in the building and construction industry took effect on 1 July 2012.13 Further, from 1 July 2013, the PSI tax lodgement process for businesses was simplified by replacing the PSI schedule with a smaller set of specific questions in the annual income tax return.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

11. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Taxation Office’s administration of the personal services income regime.

12. The audit examined whether the ATO’s:

- governance arrangements for the PSI regime are appropriate and effective;

- systems and processes to identify and assess compliance risks are adequate and effective; and

- strategies to promote compliance and address non‑compliance are appropriate and effective, and their impact is being measured.

13. The audit also examined the ATO’s Part IVA program where it involved personal services businesses.

Overall conclusion

14. The PSI regime was introduced on 1 July 2000 as part of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 to address the erosion of the tax base arising from taxpayers alienating PSI—that is, gaining taxation advantages such as claiming business deductions and splitting income earned from personal services when they were not genuinely conducting a business. The regime was subject to independent review by the Board of Taxation and the Henry Review in 2009 and 2010 respectively, which noted complexity and uncertainty of the PSI rules for taxpayers, and the potential for considerable non‑compliance.

15. The PSI regime is a small proportion of the overall activity of the ATO but is important to the equity and integrity of the tax system. The ATO has effectively administered many of the key elements of the regime, including developing sound governance arrangements and appropriate business planning, risk management and reporting processes. There has also been an evolving program of compliance activities to promote voluntary compliance and to address non‑compliance with PSI obligations.

16. The ATO last attempted to quantify the net revenue impact of the PSI rules (revised in 2001 to be $2.3 billion over six years) and the population of taxpayers that do not declare PSI in 2004–05, but was unable to do so with any reliability or accuracy; and there have been no subsequent attempts. The ATO has also yet to determine whether its compliance activities are effectively mitigating the ongoing alienation of PSI risk. Nevertheless, the ATO advised that it is endeavouring to better understand and estimate the population of non‑compliant taxpayers as part of the PSI compliance effectiveness assessment14 currently underway and anticipated to be completed in late 2013. A methodology to estimate the magnitude of the potential revenue at risk from this non‑compliance would contribute to establishing a baseline for comparison over time in future compliance effectiveness assessments.

17. There are, however, indications that the PSI regime has reversed the trend of wage and salary earners incorrectly accessing the business tax system when receiving PSI. From 2000–01 to 2011–12, the total number of individuals declaring PSI15 increased from around 184 000 to over 434 500, while the number of entities (such as partnerships, trusts and companies) decreased from around 32 000 to 28 000. Further, annual net PSI declared increased from $1.0 billion in 2000–01 to $3.1 billion in 2011–12.

18. The ATO’s strategies to encourage voluntary compliance and to address non‑compliance with PSI rules include educational material, general and specific advice as well as letter campaigns, reviews and audits.16 The ATO has calculated that compliance enforcement activities, which are based on an annual review of the alienation of PSI risk, have resulted in $38 million in additional revenue being collected over the last 10 years.

19. The ATO has found that at risk PSI taxpayers have common links with other non‑compliant contractors it manages.17 As a consequence, compliance activities being undertaken by other areas of the ATO will include PSI taxpayers. The ATO acknowledges that currently, these interactions across the ATO are not well communicated or appropriately documented. Capturing this information and analysing the outcomes of these compliance activities would assist with the ongoing assessment and reporting of the range of risks associated with the contractor population.

20. Stakeholders interviewed by the ANAO held mixed views about the complexity of the PSI regime.18 Some considered the rules complex and difficult to comply with, while others thought the regime was now operating more smoothly. The ATO has acknowledged that further communication is required to raise awareness and to improve taxpayers’ and tax practitioners’ understanding of their PSI obligations.

21. The ANAO has made one recommendation aimed at strengthening the assessment of the PSI compliance risk and the effectiveness of PSI compliance activities, by estimating the population of non-compliant taxpayers and the magnitude of revenue at risk.

Key findings by chapter

Governance Arrangements (Chapter 2)

22. The governance arrangements within ME&I supporting the PSI regime are appropriate. Business plans include activities relating to PSI as well as relevant performance measures and targets. Given its relative scale, there is minimal external reporting of PSI activities, but internal reports monitor actual achievements against the PSI activities planned.

23. ME&I’s risk management processes incorporate an annual review of risks, overseen by the business line’s Risk Management Committee. The ‘alienation of PSI’ risk has been reviewed by the Committee at least annually. The December 2012 quarterly review noted that the PSI risk assessment, risk summary and treatment plan had been finalised and approved by the risk owner. Planned PSI activities draw upon annual PSI risk treatment plans and include compliance case coverage, case volumes, and anticipated revenue figures. However, the business plan performance measure relating to measuring compliance effectiveness, introduced in 2010–11, has not been reported against for PSI. Nevertheless, work is underway to address this gap and is expected to be completed later this year.

Managing Compliance Risks (Chapter 3)

24. PSI is considered by the ATO to be an ‘endemic risk’, as it continues to be identified through compliance and data matching activities. Comprehensive PSI risk assessments were conducted in 2008 and 2011, and show very little change in the risk profile.19 In particular, the percentage of taxpayers that reported earning most of their taxable income from personal services, as opposed to earning other forms of income as well as PSI, was around 30 per cent (26 400 taxpayers) in 2005–06 and 29 per cent (30 000 taxpayers) in 2009–10. However, there have been no attempts to estimate the size of the non‑compliant PSI population since 2004–05.

25. The introduction of the taxable payments reporting system from 1 July 2012 and replacing the PSI schedule of business tax returns with a set of specific questions will provide additional information for use in the ATO’s next comprehensive PSI risk assessment, currently scheduled for 2014. As part of this process, it would be beneficial to include an updated estimate of the number of taxpayers not declaring PSI, in light of findings from a 2012–13 PSI risk assessment exercise. This ‘risk summary’ identified that ATO data matching exercises had found that 81.5 per cent of entities in the selected sample may have incorrectly classified their income by not declaring their personal services business status.20

26. As it is difficult for the ATO to identify non‑compliant taxpayers using only the PSI information from tax returns, data matching programs were undertaken using labour hire firm data in 2007, 2009, and 2011. The use of data matching for compliance case selection has contributed to the improved ‘strike rate’21 (the percentage of compliance cases that have an outcome) of active compliance cases, from 60.2 per cent in 2010–11 to 78.9 per cent in 2012–13.

27. Annual PSI risk treatment plans cover a range of compliance activities to educate taxpayers about PSI, increase understanding and test for non‑compliance. The treatment strategies align with the risk behaviours documented in the PSI risk assessment, but not all strategies can be implemented because of resource constraints. Past compliance results are used in planning future compliance strategies. More recently, data matching activities have been repeated and greater emphasis has been placed on letter campaigns as an efficient method of interacting with a greater number of taxpayers.

28. In developing PSI risk treatment strategies, the ATO acknowledges that it does not currently coordinate the interaction of all contractor risk treatments, such as the inclusion of PSI in other streams’ plans and compliance mitigation strategies. An estimate of the non‑compliant population would also assist in the development of future PSI risk treatments.

Promoting Voluntary Compliance (Chapter 4)

29. The ATO’s strategies for promoting voluntary compliance with the PSI regime are generally appropriate. Marketing and education activities include online information, presentations to external stakeholder groups (including tax practitioners) using media such as webinars and webcasts, and all primary PSI‑related information has been recently updated. Although measuring the effectiveness of communication activities is difficult, the reach of communication is being measured by the ATO. The ATO’s risk assessments acknowledge that further communication is required to raise awareness of PSI obligations to those new to business, and to improve tax practitioners’ understanding of PSI. In this regard, there would be benefit in the ATO developing online decision tools to assist taxpayers to self‑assess and apply the PSI tests, and to incorporate PSI information into the existing employee/contractor decision tool.22

30. Interpretive assistance staff provide general advice to taxpayers and practitioners, as well as managing determinations, rulings and objections. Reports of the activities undertaken have been compromised in the past, following changes to recording and management systems in 2009–10. The ATO advised that poor record‑keeping during this period and in 2010–11, resulted in the number and outcome of some activities being unreliable. ATO data shows that the number of determinations has decreased significantly over time (from over 1800 in 2000–01 to 155 in 2012–13), despite the stated complexity of the legislation and the entry of new taxpayers into the system every year. However, the relatively high proportion of unfavourable outcomes (32 per cent, or 49 of 152 in 2011–12 and 21 per cent, or 33 of 155 in 2012–13) for determinations would suggest a need for greater communication and education. Adverse determinations were also to be considered in compliance case selection but this has not yet occurred.

31. The ATO does not currently analyse the basis for trends in taxpayer PSI queries or requests for determinations, private rulings and objections. This analysis would assist the ATO to better tailor the education material and advice provided to taxpayers and tax practitioners, as well as provide information on the effectiveness of these activities. In addition, the ATO undertakes a wide range of stakeholder consultation and research to assist with its understanding of taxpayers’ views and behaviours in relation to taxation topics. It may be of benefit for the ATO to explore this issue further in its research and client surveys, in order to determine whether current PSI‑related communication material and advice are the most effective for the PSI audience.

32. Stakeholders have expressed confusion about the interaction between the PSI rules and Part IVA. A Part IVA test case program began in March 2003 and has continued as a limited compliance program since 2009. Both programs were intended to provide clarity around the application of Part IVA to personal services businesses. However, the program still has not resulted in a clear outcome or a case being tested before the courts. As a result, taxpayer uncertainty in organising their personal services businesses to comply with the regime remains and was raised as a concern by some stakeholders. Given the lack of success of the Part IVA program in clarifying the application of Part IVA to personal services businesses over the past 10 years, the ATO may wish to review whether there is merit in continuing the program.

Addressing Non‑Compliance (Chapter 5)

33. The ATO has a range of strategies for addressing non‐compliance with the PSI regime. Letter campaigns are increasingly being used as a less resource‑intensive method for interacting with a larger number of the potential PSI population, with over 10 700 letters being sent between January 2012 and June 2013. These campaigns are also the only recent compliance activities directed at potential non‑declarers of PSI. The ATO assessed that the three letter campaigns in 2012 resulted in disclosure by some 10–15 per cent of targeted taxpayers, with voluntary disclosures providing approximately $1.1 million in additional revenue as at June 2013.23

34. Although the number of compliance reviews and audits has declined significantly (from over 800 cases in 2003–04 to 441 cases finalised in 2012–13), additional revenue collected has been relatively steady and the average revenue per case has increased over time. ATO data indicates that the average collected per case in 2005–06 was $5778 (450 cases raised $2.6 million) whereas in 2012–13, each case collected an average of $7482 (441 cases raised $3.3 million). The ANAO’s analysis of a sample24 of review and audit cases showed that key active compliance procedures were generally adhered to, including 94 per cent of cases meeting the planning requirements and 91 per cent of cases meeting decision procedures and requirements.

35. The ATO has an 80 per cent internal performance benchmark for compliance cases being finalised within prescribed time periods. For comprehensive audits it is 360 days and for comprehensive reviews it is 240 days. ATO records show that only 62 per cent of PSI cases met this performance standard in 2010–11; increasing to 75 per cent of cases in 2011–12; and 98 per cent of cases in 2012–13. Cases generally escalate from a review to an audit, however the ANAO found that 23 per cent of comprehensive review cases (completed from 1 July 2009 to 31 March 2013) exceeded the maximum allowable cycle time before escalation to an audit. The ATO may wish to reconsider when cases are escalated to audit and how the timeframes for these reviews/audits are recorded.

36. Work is being undertaken to measure the effectiveness of compliance activities in addressing the alienation of PSI risk, using the ATO’s Compliance Effectiveness Methodology. The methodology involves four phases: articulating the risk; defining successful outcomes and developing compliance strategies to achieve those; identifying and testing success indicators; and using those indicators to measure the effectiveness of the compliance strategies. The ATO undertook a PSI compliance effectiveness assessment during 2011–12, and the results of the assessment were put to the Risk Management Committee in October 2012. However, the assessment was withdrawn as the ME&I Executive asked for further work on the success indicators. At the time of this audit the assessment had not been completed.

37. The ATO has not attempted to quantify the level of non‑compliance in the PSI population since 2004–05, or developed a methodology to assess the magnitude of the related revenue at risk. These estimates are an important element in any assessment of the effectiveness of PSI compliance activities and would establish a baseline for comparison with future PSI risk and compliance effectiveness assessments.

Summary of agency response

38. The ATO provided the following summary comment to the audit report:

The ATO welcomes this performance audit and considers the report supportive of our overall approach to administering the personal services income (PSI) regime. The audit recognises that the ATO has effectively administered key elements of the PSI regime including the development of sound governance arrangements, appropriate business planning, risk management and reporting processes.

The ATO agrees with the report’s recommendation that the assessment of the alienation of PSI risk and the effectiveness of PSI compliance activities can be further informed by estimating the number of non-compliant PSI taxpayers, and developing a methodology to assess the potential magnitude of the revenue at risk from the estimated non-compliance.

39. The ATO’s full response is included at Appendix 1.

Recommendation

|

Recommendation No. 1 Para 5.37 |

To better inform its assessment of the alienation of personal services income (PSI) risk and the effectiveness of PSI compliance activities, the ANAO recommends that the Australian Taxation Office: (a) estimates the number of non‑compliant PSI taxpayers; and (b) develops a methodology to assess the potential magnitude of the revenue at risk from this non‑compliance. |

|

|

ATO response: Agreed. |

Footnotes

[1] ATO, Annual Report 2011–12, Canberra, October 2012, page c. At the time of preparation of this report, 2011–12 was the latest year for which the ATO could provide these figures.

[2] On 1 July 2000, the New Business Tax System (Alienation of Personal Services Income) Act 2000 inserted Part 2–42 into the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997.

[3] The number of owner‑managers of incorporated enterprises increased from 110 700 in 1978 to 465 900 in 1997, although the Ralph Report acknowledged that not all of these entities would necessarily be providing services in an employee‑like manner.

[4] Explanatory Memorandum, New Business Tax System (Alienation of Personal Service Income) Bill 2000, p. 4.

[5] The estimate was revised to account for the introduction of pay as you go withholding tax, the PSI results test and certain exemptions for financial planners.

[6] The five tests are sequential, and the assessment is completed if one is met. In broad terms, they involve an assessment of whether: (1) payments are for agreed outcomes rather than hours worked; (2) 80 per cent or more of the PSI comes from more than one client; and if so, (3) the income is from two or more unrelated clients; (4) employees or sub‑contractors are engaged, or (5) a business premises is maintained.

[7] A ‘personal services business’ is a business (sole trader, company, partnership or trust) that earns income from personal services and meets the results test or at least one of the four personal services business tests, and/or has a determination from the ATO stating it is a personal services business.

[8] For example, an individual providing information technology services, being paid according to hours worked, and failing the other PSI tests earns PSI and will be subject to the PSI rules. Alternatively, an individual receiving income on the basis of the agreed outcomes from providing these services would be classified as a personal services business, and subject to business taxation arrangements including deductions such as work‑related travel.

[9] A determination states the Commissioner of Taxation’s opinion on the application of a tax law to specific circumstances.

[10] Part IVA of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (Part IVA) has a broad application, and can apply to any circumstance where the Commissioner considers a scheme has been entered into for the sole or dominant purpose of obtaining a tax benefit.

[11] In July 2013, this business line was renamed the Small Business/Individual Taxpayers Business Line. For the purpose of this audit it is referred to by its former name.

[12] The ATO’s compliance model is structured around four strategies: make it easy to comply; help to comply; deter non‑compliance by detection; and use the full force of the law for significant fraud or tax evasion activity.

[13] Known as the ‘reporting of taxable payments to contractors in the building and construction industry’, this information will provide a data source that can be matched against ATO PSI data holdings.

[14] The ATO’s Compliance Effectiveness Methodology sets out its method for assessing the effectiveness of its compliance activities in treating the specified risk. It is based on two key elements: identifying measurable compliance objectives; and treating the risks to achieving them; and is undertaken across four phases of assessment.

[15] That is, individuals declaring PSI on their income tax returns and either being subject to the PSI regime or being classified as personal services businesses and not being subject to the regime.

[16] The ANAO’s assessment of 221 PSI compliance reviews and audits showed general adherence to key ATO procedures, with 94 per cent of cases meeting planning requirements and 91 per cent meeting decision procedures.

[17] Other contractor risks being managed by the ATO include: ‘sham contractors’, who receive income that should be classified as salary and wages; ‘non‑lodgers’, taxpayers (including contractors) who receive income but fail to register or to submit tax returns; and ‘level playing field’, the project addressing contractors who understate or omit income from their tax returns.

[18] Stakeholders interviewed included CPA Australia; the Association of Professional Engineers, Scientists and Managers Australia; the Civil Contractors Federation; the Housing Industry Association; Independent Contractors Australia; Master Builders Australia; and Taxpayers Australia.

[19] Annual risk summaries are also developed, containing more recent information than the comprehensive risk assessment.

[20] The significance of this non‑compliance may be low, as prior compliance case results have shown that many taxpayers who satisfy one of the personal services business tests do not complete the appropriate questions on their tax returns due to the complexity and cost of compliance with PSI obligations.

[21] The strike rate has a performance benchmark of 55 per cent.

[22] This online decision tool, available on the ATO’s website, assists employers to determine whether their workers are employees or contractors.

[23] As results for campaigns update over time, the June 2013 campaign results were not available at the time of preparing this report.

[24] The ANAO assessed a sample of 221 closed cases against ME&I Active Compliance procedures, representing 62 per cent of the 359 completed cases from the period 1 July 2009 to 28 March 2013.