Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of the Strengthening Basin Communities Program

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of the Environment’s administration of the Strengthening Basin Communities Program.

Summary

Introduction

The Murray–Darling Basin

1. The Murray–Darling Basin (the Basin) is the catchment for the Murray and Darling rivers and their tributaries. It contains Australia’s three longest rivers—the Darling, the Murray and the Murrumbidgee—as well as nationally and internationally significant environmental assets, such as wetlands, billabongs and floodplains.

2. Through a combination of drought and flood, emerging changes in climate, population growth and the impact of past water allocation decisions, the Basin’s communities, industries and natural environment are under strain.1 In response, recent Australian Governments have increased their focus on improving water management practices across the Basin. During the period between 2007 and 2012, the Water Act 20072 and the Water Amendment Act 2008 were introduced, and the Murray–Darling Basin Authority3 (MDBA) prepared the Basin Plan to manage the Basin’s water resources in a coordinated and sustainable way in collaboration with the community.4

3. In January 2007, the then Prime Minister also introduced the National Plan for Water Security, which provided $10 billion over a 10-year period to increase agricultural production with less water use while improving environmental outcomes. This commitment to water initiatives has progressively increased, primarily through the Water for the Future Initiative. This initiative incorporated elements of the earlier national plan and provided an additional $2.9 billion in funding over a 10-year period (2008 to 2018) towards a suite of urban and rural policies and programs, including funding for: water purchasing; irrigation modernisation; desalination; recycling; and storm water capture.5

4. The Federal Parliament has had an ongoing interest in water management and the initiatives established by government to balance water use and the effect of water restrictions on communities located in the Basin. In 2008, the impact of the then proposed Water Amendment Bill 2008 was examined by the Standing Committee on Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport. The committee’s report supported the Bill, stating that it would enable water resources in the Murray–Darling Basin to be managed in the national interest, optimising environmental, economic and social outcomes.6 A minority report from this inquiry, by the Australian Greens and endorsed by the Independent Senator for South Australia, Senator Nicholas Xenophon, recommended that community planning be made a priority, with incentives and support provided to communities to assist them in creating plans that integrate infrastructure investment, water sales and structural adjustment.7

5. Senator Xenophon subsequently promoted the importance of government support for communities in the Murray–Darling Basin and negotiated an agreement with the then Government for additional funding in return for his support for its stimulus measure—the Nation Building and Jobs Plan—in early 2009. As a part of this agreement, the Government committed to provide $200 million in funding for a program initially titled Local Plans for a Future with Less Water.8

6. The Department of the Environment9 (Environment) commenced work on implementing the $200 million program, now titled the Strengthening Basin Communities Program (SBCP), to assist communities to plan for a future with less water, and develop water saving initiatives to support these plans. The SBCP is part of the $5.8 billion Sustainable Rural Water Use and Infrastructure Program (SRWUIP), which is the largest component of the Water for the Future Initiative.

Strengthening Basin Communities Program

7. The SBCP consists of two separate components: the Planning Component and the Water Saving Initiatives Component. The Planning Component had an initial allocation of $20 million. It was designed to provide grants for local government authorities in the Basin to assess the risks and implications associated with climate change with a focus on water availability, and to either review existing plans or develop new plans to take account of these risks and implications. The Water Saving Initiatives Component, which was allocated the remaining $180 million, was designed to support projects to improve urban water security through water saving initiatives that reduce demand on potable10 supplies in the Basin by:

- reducing water loss in distribution systems;

- reducing potable water use; and/or

- providing ‘fit for purpose’ water that can replace potable water.11

The Water Saving Initiatives Component was accessible to local government authorities and water utilities in the Basin.

Administrative arrangements

8. The SBCP is administered by Environment, a role which has included engaging with stakeholders and potential applicants, designing and implementing a grant assessment and selection process, and managing subsequent funding agreements. The department has conducted two separate funding rounds under each component, with separate program guidelines prepared for each component and each funding round.

9. All applications were assessed for eligibility by departmental officers. The assessment of applications against the merit and prioritisation criteria12 was also undertaken by departmental officers, with external technical assistance obtained for the Water Saving Initiatives Component. During Round 1 (both components), the Minister for Climate Change and Water held decision-making responsibilities for the SBCP. On 14 September 2010, the Minister for Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities assumed the role of decision-maker. This period covered the approval of grant recipients for Round 2 of both program components.

Funding allocations

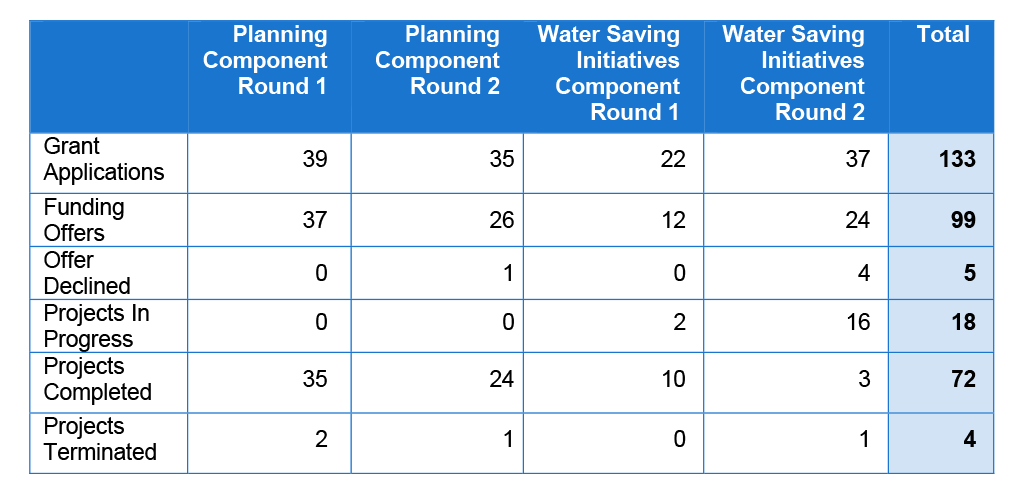

10. The department received 133 applications across both components and rounds of the SBCP. Of these, 99 applications were recommended to the relevant Minister for funding. The recommended applications involved 109 local government authorities (including where part of a consortium) and two water utilities.13 The Ministers approved 75 projects and gave in-principle approval to an additional 24 projects, to a total of $81.7 million ($19.3 million under the Planning Component and $62.4 million under the Water Saving Initiatives Component). However, five applicants did not enter into funding agreements with the Commonwealth. As at October 2013, 94 funding agreements to the value of $71.2 million had been signed ($19.3 million under the Planning Component and $51.9 million under the Water Saving Initiatives Component). Table S.1 (on the following page) provides a summary of the number of applications, funding offers and the status of projects.

11. Under the Planning Component, funding was provided for a range of activities including: plans to secure alternative water supplies for recreation reserves and other community green spaces; studies into the impact of climate change on the socio-economic security of an area; a platypus awareness and conservation plan; and groundwater modelling. These grants ranged from $18 570 to $800 000, with the median being $200 000. Projects funded under the Water Saving Initiatives Component included: water and/or effluent recycling and reuse plants; pipeline replacement; and stormwater harvesting projects. These grants ranged from $24 500 to $9 270 000, with the median being $891 000.

Table S.1: Grant summary information (as at October 2013)

Source: Departmental information.

12. In August 2012, the Government decided to transfer $100 million from the SBCP to the then Department of Regional Australia, Local Government, Arts and Sport to fund the Murray–Darling Basin Regional Economic Diversification Program. The allocation of the remaining funding is yet to be determined.

Audit objective and criteria

13. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of the Environment’s administration of the Strengthening Basin Communities Program.

Criteria

14. To form a conclusion against this audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- the program design reflected the policy intention;

- sound administration arrangements were put in place to support its implementation;

- the assessment and selection process was sound and provided Ministers with sufficient information to support their decisions;

- funding agreements were effectively negotiated and managed; and

- progress against the program’s objectives was monitored and reported.

Overall conclusion

15. The Australian Government initially allocated $200 million in funding under the Strengthening Basin Communities Program (SBCP) to assist communities in the Murray–Darling Basin to assess the risks and implications associated with climate change and to identify local water efficiency measures that would meet the needs of communities now and into the future. The program was delivered across two components and two funding rounds, with 99 projects valued at $81.7 million approved for funding.14 As at October 2013, five applicants had not accepted the funding offer, 72 projects had been completed, four had been terminated and 18 were ongoing.

16. Program funding has been allocated to a broad range of projects across the Basin to assist communities to plan for a future with less water and to develop water savings initiatives. Despite the delivery of SBCP projects being adversely affected by extreme weather events, including drought conditions and severe flooding, all completed projects have reported positive results. Projects have resulted in the creation of planning documents, including socio‑economic modelling of how communities will be affected by a future with less water, and the construction of water saving infrastructure, such as grey water and stormwater re-use systems.

17. The department has worked in a collaborative and flexible manner to assist grant recipients to achieve the intended outcomes of their projects. However, there were significant shortcomings in some key aspects of program implementation that detracted from the effectiveness of the department’s administration. These included the design of the program guidelines, the subsequent assessment of grant applications, and the management of funding agreements.

18. The program guidelines published by the department provided applicants with a broad range of information. However, for each of the four sets of guidelines created (one for each component and round) information regarding program eligibility requirements was dispersed throughout the document. As a consequence, it was difficult for applicants and the department to easily determine whether eligibility requirements had been met. In total, 13 projects progressed to merit assessment15 despite not strictly meeting eligibility requirements, mostly in relation to applicant contributions. While the merit scores for six of these projects were not sufficient for them to be recommended for funding, the remaining seven were given in-principle funding approval, with six projects receiving funding.16 In addition, Environment departed from the assessment processes outlined in the program guidelines and did not fully document the basis of its decisions. As a result, the transparency, accountability and, ultimately, the equity of the assessment and selection process was adversely affected.

19. In relation to the management of funding agreements, Environment did not establish a sound and consistent process to manage the scope of funded projects. As a result, activities were funded that had not been merit assessed, and, on the other hand, activities that had been included in the assessment that determined the merit of the proposed projects were removed.17 Also, the opportunity to amend approved projects was not offered to all applicants, which again raises questions regarding the equity of the assessment and selection process. There were also shortcomings in the management of reporting obligations and the acquittal of grant funding. In particular, the department did not reconcile: recipient contributions to projects against the commitments included in funding agreements; and financial information included in the final report assessment against the audited financial statements to gain assurance over project expenditure. These shortcomings detracted from the department’s approach to monitoring program expenditure18 and applicant contributions to funded projects.

20. There would also be merit in Environment reviewing its approach to the reporting of SBCP performance. The department reported the achievements of the SBCP in a consolidated form with other departmental water programs. In some years it identified those projects that had contributed to this consolidated data and in others it did not. The individual contribution of each program to the consolidated figures was not, however, included. Further, the department did not disclose that the water savings data reported for the SBCP were based on estimates, including from projects that had yet to be completed, rather than actual program achievements.19 As such, stakeholders, including the Parliament, have limited visibility regarding program performance and the extent to which the Government’s objectives have been achieved.

21. While Environment has made a number of improvements to the administration of the SBCP over the life of the program, there remains scope to strengthen the department’s grants administration practices. The ANAO has made three recommendations designed to: improve the transparency and accountability of grant assessment and selection processes; strengthen the management of funding agreements; and more accurately report program performance.

Key findings by chapter

Program design and establishment (Chapter 2)

22. The SBCP was designed to reflect the policy parameters established by the Government. Its implementation was guided by the early development of sound supporting documentation, including project, risk management and stakeholder engagement plans.

23. In accordance with the grants administration framework, the department published approved program guidelines for each component and round of the SBCP. The development of the guidelines was informed by consultation with internal and external stakeholders, including with departmental officers from similar programs20, relevant government agencies and the Minister, and outlined the key elements of the program.

24. While the program guidelines generally provided potential applicants with a broad range of information, there was scope for the department to have provided clearer and/or additional information regarding eligibility requirements. The program guidelines for all SBCP components and rounds included sections titled ‘eligibility’, ‘applicant eligibility’ or ‘project eligibility’ within which eligibility requirements were outlined. However, the various guidelines included additional eligibility requirements or provided further information that modified the requirements in these sections.21

25. Further, the department established a threshold score for each criterion, which required applicants to achieve a score of three or more out of a possible five, to be recommended for funding. The use of thresholds was not foreshadowed in the published guidelines. Twenty-seven projects that the department had assessed as being eligible did not receive funding because they did not meet these threshold requirements. If this information was included in the program guidelines, applicants that were not competitive across all criteria may have decided against investing resources in preparing an application.

26. The guidance material prepared by the department to inform the SBCP assessment and selection process included a program evaluation or assessment plan for each component and round. While the development of these plans provided a sound basis to guide the assessment process, there was a lack of consistency between the plans and the published program guidelines. As a consequence, the clarity of the process was adversely affected. In a number of cases where there was a conflict, departmental officers adopted the process outlined in the published guidelines to maintain transparency. However, in other cases, the process outlined in the evaluation or assessment plan was adopted, which was inconsistent with information provided to potential applicants, such as the use of threshold scores.

27. The department was aware of its responsibility to appropriately manage probity issues, including the management of conflicts of interest. A probity plan was prepared and departmental officers and technical advisors were required to declare conflicts, potential conflicts or apparent conflicts of interest.22 However, the department took a narrow view of what might be considered a conflict, and did not explore the breadth of possible relationships between advisors and applicants. The resulting conflict of interest statements––which focused on a single round and component of the SBCP––did not specifically require technical advisors to declare any involvement in applicants’ previous SBCP applications, projects or other commercial relationships. In the event, two of the three contracted advisors engaged to assist with Round 2 of the Water Saving Initiatives Component were involved in applicant projects from previous SBCP components or rounds.23

Governance arrangements (Chapter 3)

28. The oversight arrangements for the SBCP provided a sound basis to guide the implementation of the program. The department identified and managed the risks to the achievement of the program’s objectives at a program and project level, with the risk profile being reviewed on a regular basis. While this approach was appropriate, there was scope for the department to provide additional guidance to program staff assessing project risks. This would have reduced the inconsistency between assessments and enhanced their reliability over time.

29. The performance information for the SBCP has not been separately identified in Environment’s Portfolio Budget Statements (PBS) and annual reports.24 While the department identified the programs that contributed to the consolidated performance data in some years, it did not in others, and it did not provide information on the contribution of each program to the consolidated data. Further, the annual reports did not clearly state that the water savings data for the SBCP was based on estimates, and in some cases, for projects that had not been completed, rather than actual outcomes from completed projects.

30. The measures against which program performance has been reported have also changed over time and, as a consequence, it has been difficult for stakeholders to assess the achievements of the program over its life. The department has committed to provide ‘quantitative and qualitative evidence of additional urban water’ delivered as an outcome of the SBCP and other similar water programs in 2015.25 However, the limited performance data collected to date, and the termination of contractual relationships with SBCP funding recipients following the completion of their projects, will make it challenging to collect the relevant data needed to support an evaluation of the achievements of the program.

Grant assessment and selection (Chapter 4)

31. The SBCP program guidelines outlined the criteria to be used to assess eligibility for program funding. The eligibility criteria differed between each component, and were modified between each round. These changes coupled with the dispersal of eligibility requirements throughout the program guidelines, as outlined earlier, made it more difficult for applicants and the department to easily determine eligibility. As a consequence, 13 projects progressed to the merit assessment stage despite not strictly meeting all eligibility requirements, with six projects receiving funding.26

32. The department created and retained a broad range of documentation to evidence the assessment and selection process, with the level of documentation increasing in later rounds primarily through the use of improved templates.27 Nevertheless, some aspects of the assessment were not sufficiently documented to support an accountable and transparent process. In particular, documentation evidencing the moderation of individual assessments to produce a final recommendation was not retained for either component or round.

33. The department’s recommendation to the relevant decision-maker included appropriate information on the requirements of the financial management framework and an overview of the assessment and selection process. The Minister approved all recommended applications for both Planning Component rounds and the Water Saving Initiatives Component Round 1 without change. In contrast to earlier rounds, the department’s recommendation to the Minister that Water Saving Initiatives Component Round 2 applications be approved on an in-principle basis, pending the provision of additional information by applicants, was unusual. 28

34. The department adopted this approach on the basis that the applications provided information required to address the merit criteria, but did not sufficiently describe the proposed projects. The Minister approved the department’s recommendation that it approve the offers of grant funding once the required information was provided and assessed. While it is prudent for agencies administering grant programs to obtain all necessary information to support an informed decision on the allocation of funding, the information is generally obtained through the application process or sought during the assessment process. The fact that additional information was required from all recommended Round 2 applicants would indicate that there was scope for greater clarity of information requested as a part of the application process.

35. The department notified all applicants of the success of their applications. In some cases, the department offered partial funding or altered the scope of the proposed project as part of the assessment process. The program guidelines did not, however, outline to potential applicants that the department may reduce funding and/or alter the scope of proposed projects. While the changes were broadly outlined in the department’s letter of offer, greater detail regarding the implications for the project budget and scope would have reduced the potential for misinterpretation or confusion.29

Negotiation and management of funding agreements (Chapter 5)

36. The department offered funding agreements to the 99 approved grant applicants, with 94 entering into agreements with the Commonwealth. The majority of endorsed funding agreements reflected the relevant details of each application and subsequent departmental amendments determined during the assessment process.30

37. Agreement variations were used extensively by the department to account for changes in the delivery environment that resulted in the delayed implementation of a number of projects. In particular, the department used variations to extend project timeframes to reflect the impact of extreme climatic conditions that occurred during the program’s implementation period. While the department’s use of variations was generally appropriate, in some cases variations resulted in the use of SBCP funding for project activities that: did not meet the eligibility requirements as outlined in the program guidelines, such as using Planning Component funding for signage and educational materials; or had not been competitively assessed against the merit or prioritisation criteria outlined in the program guidelines to ensure that it represented an appropriate use of Commonwealth funding. Further, in a number of cases, Environment did not retain fit-for-purpose documentation, such as an exchange of letters, which provided both parties with a clear understanding of changed requirements.

38. The department established a monitoring program to gain assurance that recipients were complying with the obligations established under their funding agreement. This included recipients providing progress reports and audited financial statements, and visits to selected project sites by departmental officers. Grant recipients held mixed views regarding the appropriateness of the monitoring program, with some considering the reporting requirements to be cumbersome and excessive, while others considered the reporting proportionate to the level of funding being provided. The work of departmental officers in supporting grant recipients throughout the program was consistently recognised by recipients.

39. There was, however, scope for the department to strengthen aspects of its management of funding agreements, particularly in relation to the integrity of payments and the acquittal of in-kind contributions from grant recipients. While the department sought audited financial statements for each project and prepared an assessment of each project’s final report, there were inconsistencies in the financial information included in these documents. This made it difficult to reconcile payments. The ANAO identified two cases where the department was unaware that it had overpaid grant recipients, to the value of $56 000. The department has subsequently sought to recover these overpayments. In addition, the department did not establish sound processes to acquit grant recipient contributions to projects, both cash and in-kind for Planning Component projects and in-kind for Water Saving Initiatives Component projects. As the provision of in-kind contributions was included as an obligation in the funding agreements, it is important for Environment to manage funding recipient’s compliance with this obligation.

Summary of agency response

40. Environment’s summary response to the proposed report is provided below, with the department’s full response at Appendix 1:

The Department of the Environment is grateful for the opportunity to respond to the audit report and agrees with audit Recommendation Nos. 1,2 and 3. The Department notes that the audit has highlighted some areas for future improvement in the grants administration process and these recommendations will be incorporated into the administration of current and future grants programs.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 3.35 |

To improve the measurement and reporting of program performance, the ANAO recommends that the Department of the Environment:

Environment’s response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No. 2 Paragraph 4.72 |

Consistent with the transparency and public accountability principles of grants administration, the ANAO recommends that the Department of the Environment reinforces the importance of:

Environment’s response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No. 3 Paragraph 5.55 |

To improve the management of future grant funding agreements, the ANAO recommends that the Department of the Environment:

Environment’s response: Agreed |

Footnotes

[1] Murray–Darling Basin Authority (MDBA), Environmental Changes and Issues in the Basin, c2013, available from http://www.mdba.gov.au/about-basin/basin-environment/challenges-issues [accessed 5 November 2013].

[2] The Water Bill 2007 was introduced into Parliament by the then Coalition Government (1996–2007) and implemented a number of elements of that Government’s National Plan for Water Security. It came into effect on 3 March 2008 under the subsequent Labor Government (2007–13). References to the Government in this report refer to the Labor Government, unless otherwise stated.

[3] Murray–Darling Basin Authority leads the planning and management of Basin water resources in collaboration with partner governments and the community. For further information on the MDBA, see About MDBA, 2013, available from<http://www.mdba.gov.au/about-mdba> [accessed 14 August 2013].

[4] MDBA, Basin Plan, available from <http://www.mdba.gov.au/what-we-do/basin-plan>[accessed 14 August 2013].

[5] Department of the Environment, Water for the Future Fact Sheet, 2010, available from <http://www.environment.gov.au /water/publications/action/pubs/water-for-the-future.pdf> [accessed 31 August 2013].

[6] Standing Committee on Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport, Water Amendment Bill 2008, available from <http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Rural_and_ Regional_Affairs_and_Transport/Completed%20inquiries/2008-10/water_amendment/report/index> [accessed 11 June 2013], p. 16.

[7] ibid., p. 42.

[8] On 13 February 2009, the Bill supporting the Nation Building and Jobs Plan passed into law with the support of Senator Xenophon.

[9] In September 2013, the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (DSEWPaC) became the Department of the Environment as a part of changed administrative arrangements.

[10] Potable water is water that is safe for human consumption and domestic purposes.

[11] Department of the Environment, Water Saving Initiatives Component Round 2, Implementation and Funding Guidelines, July 2010, p. 5.

[12] Eligible Planning Component projects were assessed for merit against prioritisation criteria. Eligible Water Saving Initiatives Component projects were assessed against merit criteria.

[13] Sixty-five local government authorities or water utilities received one grant, while 37 local government authorities received two grants and nine received three grants.

[14] This figure includes 24 projects that were recommended to the Minister for in-principle approval, pending the provision of additional information by the applicant. The Minister also approved the department’s recommendation that it make the final funding decision once the additional information had been assessed.

[15] The criteria used to assess the merit of eligible projects under the Planning Component were termed ‘prioritisation criteria’, whereas the criteria used under the Water Saving Initiatives Component were termed ‘merit criteria’.

[16] According to the program guidelines for Water Saving Initiatives Component Round 2, applicants were required to contribute a minimum of 50 per cent of the total project value in cash. The ANAO found that the applications for seven projects indicated that their contribution to the project’s total value would be through a mix of cash, third party contributions and in-kind support. These projects received an in‑principle recommendation for funding. Funding agreements were signed with six of these applicants (the remaining project was withdrawn by the applicant). During the negotiation of funding agreements for the approved projects, the department modified project budgets to ensure that the Commonwealth provided a maximum of 50 per cent of project costs. In two cases, the department waived the eligibility requirement for grant recipients to contribute 50 per cent of the project value in cash, accepting in-kind contributions as an alternative.

[17] For example, decisions were taken to increase or decrease the geographic reach of some projects, such as including or removing towns or local government authorities from the project’s scope.

[18] The ANAO identified two cases where the department was unaware that it had overpaid grant recipients to a value of $56 000. In response to the ANAO’s finding, the department has subsequently sought to recover these overpayments.

[19] The department did not require that grant recipients measure actual outcomes from SBCP projects.

[20] These officers suggested that applicants under the Water Saving Initiatives Component be required to provide at least 50 per cent of the total project cost to increase grant recipient engagement with each project and to encourage communities to select projects that were likely to provide optimal returns. This requirement was adopted for both funding rounds.

[21] For example, to be eligible under Water Saving Initiatives Component Round 2, the Guidelines stated that projects must have total costs of at least $500 000. This established the eligibility criterion. Under the heading ‘range and period of funding’, this criterion was modified to read: The minimum value of any project will be $500 000 with the minimum Australian Government contribution of $250 000 (GST exclusive). Applicants are required to contribute a minimum of 50 per cent of the total project cost in cash.

[22] Environment’s conflict of interest declarations referred to conflict, potential conflict or apparent conflicts of interest. The term ‘potential’ conflict of interest is also used to define a declared conflict that is yet to be assessed.

[23] Three technical assessments were undertaken by advisors that had a prior commercial relationship with the applicant––or a consortium of which the applicant was a part––through previous SBCP rounds.

[24] SBCP performance information has been consolidated with information from other water programs and included in Environment’s annual reports between 2009–10 and 2011–12.

[25] DSEWPaC, Portfolio Budget Statements 2011–12, available from <http://www.environment.gov.au/ about/publications/budget/2011/pubs/pbs-2011-12.pdf>, [accessed 19 August 2013], p. 62.

[26] As noted earlier, during the negotiation of funding agreements for the approved projects, the department modified project budgets to ensure that the Commonwealth provided a maximum of 50 per cent of project costs. In two cases, the department waived the eligibility requirement for grant recipients to contribute 50 per cent of the project value in cash, accepting in-kind contributions as an alternative.

[27] An example of improvements across the two rounds was in the design, completion and retention of assessment sheets. In the first round of the Planning Component, the eligibility assessment did not review project eligibility (as required), only applicant eligibility, and approximately 30 per cent of assessments did not contain a signature or name of the assessor. These issues were addressed in Round 2. Similarly, eligibility assessment sheets for Round 1 of Water Saving Initiatives Component were not retained, but were retained for Round 2.

[28] Additional information requested by the department included: risk management plans, finalised detailed design and budget documentation, relevant planning or environmental approvals and information regarding ongoing operating and maintenance costs of the project’s infrastructure over the next 20 years.

[29] An example of this occurring was during the eligibility assessment of one application, where the department determined that one element of the proposed project was ineligible for funding, while the remaining element was eligible. The broad nature of the department’s advice to the applicant regarding the approval of aspects of the proposed program did not outline the implications of partial funding on the applicant’s obligation to contribute cash funding. The applicant incurred costs to progress its project based on the initial departmental advice, but when advised of the specific requirements for cash funding withdrew the application.

[30] In some cases agreements included terms and conditions that were outside the requirements outlined in the published program guidelines, including the: use of staged activation of some agreements; extension of project timeframes beyond the published limits; and establishing a new requirement for annual audited financial statements in Round 1 projects.