Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of the Revised Protective Security Policy Framework

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- Physical security protects people, information and assets enabling safe and secure government business.

- The revised Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) was implemented in 2018.

- Previous ANAO audits have identified that too strong a focus on red tape reduction can be at the expense of effective outcomes.

Key facts

- The PSPF applies to 97 Australian non-corporate Commonwealth entities and represents better practice for 71 corporate Commonwealth entities and 18 wholly owned Commonwealth entities.

- The Attorney-General’s Department (AGD) has published two whole-of-government maturity reports under the revised framework.

What did we find?

- The administration of the revised PSPF by selected entities was largely effective.

- Advice to government by AGD as policy owner is limited as it is reliant on self-reporting from entities that may not understand and follow the mandated security reporting requirements.

- The Department of Social Services (DSS) and Services Australia have not met all core requirements at their self-assessed maturity levels in safeguarding people, information, and assets.

What did we recommend?

- There were five recommendations, one relating to AGD; two relating to DSS; and two relating to Services Australia.

- AGD agreed to one recommendation, DSS agreed to two recommendations, and Services Australia agreed to two recommendations.

17.5%

of reporting entities assessed their physical security for resources as ad hoc or developing

30%

of reporting entities assessed their protective security for facilities as ad hoc or developing

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. In response to recommendations in the 2015 Independent Review of Whole-of-Government Internal Regulation (Belcher Red Tape Review), to reduce compliance burden and to support entities to better engage with risk, the Attorney-General introduced a revised Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) on 1 October 2018.

2. The revised PSPF is underpinned by the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) requirements to govern an entity in a manner that is ‘not inconsistent’ with Australian Government policies and promote the proper use and management of public resources. Application of the PSPF is required by the 97 non-corporate Commonwealth entities (NCEs) and represents better practice for the 71 corporate Commonwealth entities and 18 wholly owned Commonwealth companies.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

3. Physical security arrangements underpin secure delivery of government business through the protection of people, information and physical assets. As Australian Government policy, the PSPF applies to all NCEs subject to the PGPA Act, with accountable authorities responsible for physical security arrangements within their own organisations.

4. As the policy owner, the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD) has responsibility for monitoring and reporting whether the PSPF meets its intended outcomes. AGD undertakes its role through the provision of general, high-level guidance to entities on the PSPF. AGD also collects and reports entities’ annual self-assessments and information on significant security incidents.

5. The Auditor-General has tabled performance audits identifying a low level of oversight and low levels of NCE compliance with mandatory policies. This audit will provide assurance about whether AGD is fostering the intended strong security culture through strategic, diligent, and risk-based administration of the PSPF, including by assessing the accuracy of self-reporting of physical policies by two entities.

Audit objective and criteria

6. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of administration of physical security in the revised PSPF.

7. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria.

- Has the Attorney-General’s Department effectively administered the Australian Government’s protective security policy framework?

- Are selected entities appropriately monitoring their security maturity and providing a safe and secure physical environment for their people, information and assets?

8. The audit did not include examination of the selected entities’ compliance with the pre-October 2018 PSPF or PSPF policies 1 to 3 and 5 to 14.

Conclusion

9. The administration of the revised PSPF by selected entities was largely effective. Advice to government by AGD as policy owner is limited as it is reliant on self-reporting from entities. The risk of optimism bias in entity self-assessment reporting has not been addressed by AGD as part of its administration of the PSPF. The selected entities have not met all core requirements at their self-assessed maturity levels in safeguarding people, information and assets.

10. AGD’s administrative arrangements to support the revised PSPF were largely effective. AGD’s advice to government about the progress of the framework was limited as AGD relied on self-assessment information, which the ANAO has found can be overstated or inaccurate, to accurately reflect the maturity of implementation of revised PSPF requirements. As policy owner, AGD did not monitor compliance with mandatory requirements. AGD provided a variety of support including detailed written guidance that could be better tailored to low-risk and face-to-face service environments. AGD’s role can be strengthened by closer alignment of the self-assessment reporting instrument and policy, and by ensuring that entities understand and follow the mandated security reporting requirements.

11. The Department of Social Services (DSS) was largely effective in implementing requirements that it established for itself under the PSPF at the ‘managing’ and ‘embedded’ maturity levels. DSS implemented a variety of physical security measures and integrated physical security considerations into its processes. DSS did not accurately report its maturity level as ‘embedded’ for policies 4, 15 and 16 because it did not always follow its plan, and documentary evidence of the certification authority’s satisfaction with physical security requirements was incomplete.

12. Services Australia was largely effective at implementing requirements that it established for itself under the PSPF at the ‘developing’ maturity level. Physical security measures to protect people were well established and developing for information and physical assets. Protective security measures were integrated into business-as-usual operations, including at modified facilities. Services Australia’s reporting was not accurate because in two years its reporting was based on an outdated security plan, and it did not evidence that most certifications and accreditations met requirements. Services Australia’s Security Plan 2020–22 remedied deficiencies in its previous outdated plan. Certification and accreditation documentation is being reviewed and improved.

Supporting findings

Effectiveness of AGD’s administration

13. AGD largely established fit-for-purpose governance arrangements to support its administration of the PSPF. AGD established governance bodies with defined roles, and it planned to manage risk, refine policies, and engage with other entities. AGD did not establish a framework for defining the effectiveness of the revised PSPF. The risk framework has not identified all appropriate risks, including the risk of optimism bias in entities’ self-assessments (see paragraphs 2.4 to 2.28).

14. AGD collected annual entity self-assessments. In the context of indications that self-assessment information may not be accurate, including discrepancies in the reporting of significant security incidents, the use of self-assessment information to assess the effectiveness of the PSPF is limited (see paragraphs 2.30 to 2.46).

15. AGD was effective in analysing completeness of responses. AGD did not collect information to provide assurance over the self-assessment responses provided by entities. Reports to government and the public on the Australian Government’s security culture and maturity were solely based on entity self-assessments. This reduces the level of assurance AGD has on its advice on whether the policy objectives of the PSPF are being met (see paragraphs 2.49 to 2.69).

DSS’ security maturity monitoring and provision of a secure physical environment

16. DSS was largely effective at considering its progress against the goals and strategic objectives in its security plans. DSS had established a plan with goals and objectives and monitoring bodies received reports about security capability and risk culture. DSS’ reported maturity levels were inaccurate because monitoring was not consistently against the indicators in the security plan and did not cover co-location sites. DSS captured and analysed performance data and used a limited range of performance data to inform change (see paragraphs 3.3 to 3.22).

17. DSS was largely effective at implementing physical security measures for its resources. DSS considered security risks at the enterprise level against its Security Plan 2019–21, as well as specific risk mitigation measures. DSS’ reported maturity levels were not accurate because it adopted controls with less assurance where it could not undertake physical site inspections. DSS did not document its rationale for departing from the control in its Security Plan 2019–21, and it did not document the outcomes of its substitute processes (see paragraphs 3.23 to 3.37).

18. DSS was partly effective in implementing its protective security measures at selected facilities. It had integrated protective security measures at its facilities for all reporting years. In all reporting years its reported maturity levels were inaccurate because there were gaps in certification and accreditation documentation (see paragraphs 3.38 to 3.54).

Services Australia’s security maturity monitoring and provision of a secure physical environment

19. Services Australia was partly effective at considering its progress against the goals and strategic objectives in its security plans. For the first two reporting periods assessed, Services Australia’s reported maturity levels were inaccurate because the security plan was outdated, and Services Australia did not have a consistent and defined approach to monitoring its performance against identified goals and objectives (see paragraphs 4.3 to 4.17).

20. Services Australia was largely effective at implementing physical security measures for its resources at facilities visited by the ANAO. Services Australia’s reporting of ‘developing’ was accurate because it did not implement all site security review recommendations, provide all information to staff, or fully assure itself of building access and usage of ICT facilities (see paragraphs 4.18 to 4.46).

21. Services Australia was largely effective in implementing protective security measures at sites visited by the ANAO. In all reporting years, it considered and substantially integrated physical security requirements into all facilities visited by the ANAO. In all reporting years, its reported maturity levels were inaccurate because certifications and accreditation were partially in accordance with applicable requirements. Documentary records lacked explicit determination and acceptance of residual security risks (see paragraphs 4.47 to 4.70).

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.47

The Attorney-General’s Department review, reconcile and collate all significant security incident reporting data to inform assessments of whether the PSPF adequately supports entities to protect their people, information and assets.

Department response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 3.18

The Department of Social Services review and adhere to its planned schedules for assessment and reporting of progress against actions and measures of success in the department’s security plan.

Department response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 3.55

The Department of Social Services complete its certification and accreditation of its security zone areas, with documentation in accordance with PSPF core requirements.

Department response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 4.55

Services Australia undertakes site risk assessments as early as possible in the process of planning, selecting, designing and modifying its facilities.

Entity response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 4.64

Services Australia review and strengthen its monitoring and assurance arrangements for key physical security controls that seek to protect agency and Australian Government resources (people, information and assets).

Entity response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

22. Entities’ summary responses to the report are provided below and their full responses are at Appendix 1.

Attorney-General’s Department

The Attorney-General’s Department acknowledges the ANAO’s findings and welcomes the ANAO’s assessment that the department has been largely effective in its administration of the Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF).

As reflected in the Attorney-General’s Directive on the security of government business, the policy intent of the PSPF is to ensure the secure delivery of government business. To discharge our role under the Attorney-General’s Directive and the PSPF, the department employs a range of mechanisms to assess emerging security risks and refine protective security policy. The department remains committed to setting robust protective security standards to support non-corporate Commonwealth entities to protect their people, information and assets.

The department has accepted recommendation 1 (regarding security incident reporting) and is working towards implementation.

Department of Social Services

The Department of Social Services (the department) acknowledges the insights and opportunities for improvement outlined in the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) report on Administration of the Revised Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF).

The department maintains an array of physical security controls and measures to ensure we protect our people, information and assets. We acknowledge the ANAO’s overall conclusion that the department was largely effective in implementing requirements established for ourselves in relation to the PSPF. The department accepts Recommendations 2 and 3 and acknowledges the suggested opportunities for improvement within the Report. Remedial activities addressing one recommendation have been completed with certification and accreditation of security zones now fully documented for all the department’s sites.

A number of steps have already been undertaken to address the remaining recommendation and suggested opportunity for improvement. These will contribute to further strengthening of the department’s security maturity, governance and performance monitoring and reporting.

Services Australia

Services Australia (the agency) welcomes this report and agrees with the ANAO’s recommendations. The agency has commenced developing a strategy for a planned approach to uplifting the physical security maturity levels over future years. Our approach will take into consideration the audit findings, and incorporate any broader lessons where appropriate.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Policy implementation

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Protective security refers to the protection of information, people and physical assets. A security risk is something that could result in compromise, loss, unavailability or damage to information or physical assets, or cause harm to people. Physical security is the provision of a safe and secure physical environment.

1.2 The appropriate application of physical protective security measures by government entities ensures the operational environment necessary to conduct government business.

Overview of the Protective Security Policy Framework

1.3 The Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) was introduced to help Australian Government entities to protect their people, information and assets, both at home and overseas. The PSPF sets out the government’s protective security policy and comprises five principles, four outcomes and 16 core policies.

1.4 The focus of this audit is the PSPF regarding physical security with a focus on policies 4, 15 and 16. Policy 4 describes how an entity monitors and assesses the maturity of its security capability and risk culture; policy 15 describes the physical protections required to safeguard people, information and assets; and policy 16 describes the approach to be applied to building construction, security zoning and physical security control measures of entity facilities.

1.5 The PSPF is not specifically legislated. The PSPF is underpinned by the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) requirements to govern an entity in a manner that is ‘not inconsistent’ with Australian Government policies and promote the proper use and management of public resources. Application of the PSPF is required by the 97 non-corporate Commonwealth entities1 (NCEs) and represents better practice for the 71 corporate Commonwealth entities and 18 wholly owned Commonwealth companies.2

1.6 In 2015, the Independent Review of Whole-of-Government Internal Regulation (Belcher Red Tape Review) made seven recommendations to streamline the administration of the PSPF. The Belcher Red Tape Review recommended a shift from a compliance framework, underpinned by risk management principles, to a principles-based approach. To address the recommendations, to reduce the compliance burden and to support entities to better engage with risk, the Attorney-General introduced a revised PSPF on 1 October 2018.

1.7 Under the Administrative Arrangements Order of 18 March 2021, the Attorney-General’s Department (AGD) is responsible for protective security policy. As set out in AGD’s Corporate Plan 2021–25, AGD’s purpose includes maintenance and improvement of Australia’s law, justice, security and integrity frameworks.3 The Attorney-General issued a Directive as part of the PSPF updates, which stated that AGD, with oversight of the Government Security Committee, will ‘continue to assess emerging security risks and develop and refine protective security policy that promotes efficient secure delivery of government business’.4 According to the Directive, the Attorney-General expects accountable authorities to implement PSPF requirements and use security measures proportionately to address their unique security environments.

Features of the revised Protective Security Policy Framework

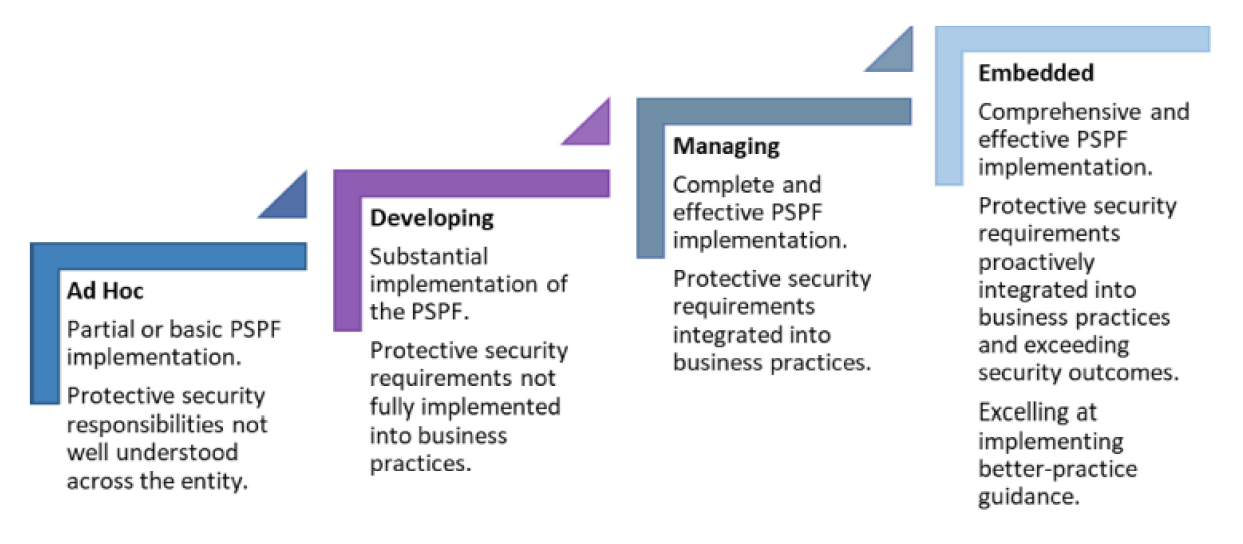

1.8 The revised framework replaced the binary (yes or no) compliance model comprising 36 requirements with a four-scale maturity model (ad hoc, developing, managing, embedded). Both models contained mandatory requirements. Figure 1.1 depicts the four maturity scales in the new model.

1.9 Under the revised PSPF framework, entities are required to assess their security maturity against each of the 16 core policies contained within four security outcomes. Entities are also required to develop tailored plans and strategies, and to continuously update their security posture to reflect their changing risk profile.

1.10 For some entities, such as the Department of Social Services (DSS), physical security involves more than one site, including wholly owned and leased facilities in Australia. In the 2020 Australian Government Office Occupancy Report, Services Australia was the entity with the largest controlled area tenancies.5 Services Australia is required to safeguard people, information and assets in 429 sites around Australia, including in rural and remote settings.

Figure 1.1: PSPF maturity assessment model

Source: Attorney-General’s Department, Protective Security Policy Framework 2019–20 Assessment Report, p. 2.

1.11 PSPF documentation indicates AGD’s expectation that most entities will fluctuate between ‘developing’ and ‘managing’ maturity depending on their risk profile, threat environment and resources. The ‘embedded’ level described in Figure 1.1 is what entities are expected to implement, and requires all core and supporting requirements to be implemented and effectively integrated. AGD reports that entities need to make an individual judgment about whether striving for an ‘embedded’ maturity level is desirable, based on their risk environment and efficient and effective use of their resources.

1.12 The following are mandatory assessment and reporting responsibilities.

- NCEs must meet the four security outcomes set out in the Protective Security Policy Framework.6

- NCEs must annually assess and report the maturity of the entity’s security capability.7

Whole-of-government maturity reports

1.13 As of March 2022, AGD has published two reports on whole-of-government PSPF maturity on its publicly available website. Table 1.1 summarises the number of entities that reported to AGD each year.

Table 1.1: AGD whole-of-government reports

|

Reporting year |

Number of entities |

Date of publication |

|

2018–19 |

98 (100%) |

15 January 2021 |

|

2019–20 |

97a (100%) |

8 June 2021 |

|

2020–21 |

97 (100%) |

Not yet published |

Note a: The difference in the number of entities reporting in 2018–19 and later years is due to Machinery of Government changes in December 2019.

Source: ANAO based on AGD documentation.

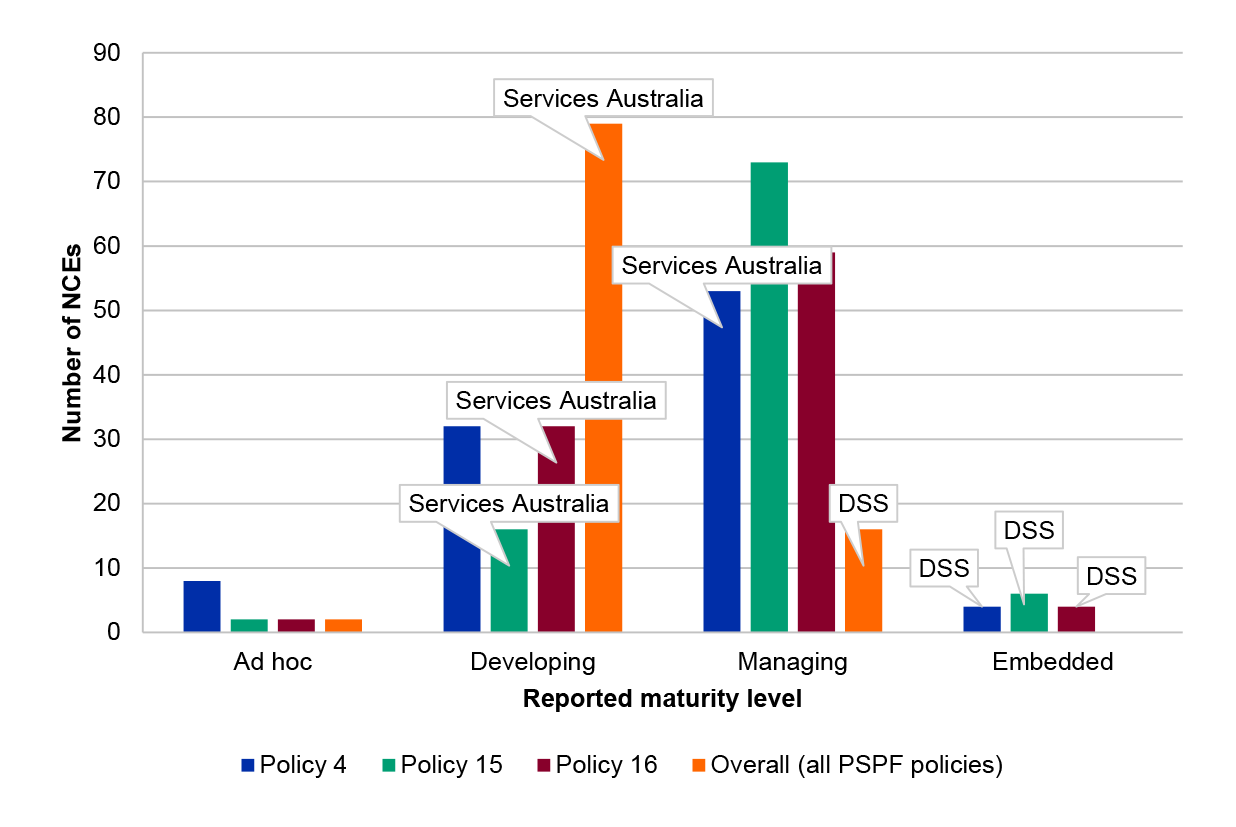

1.14 Figure 1.2 illustrates the number of NCEs reporting each maturity level in 2020–21. The figure shows that DSS was in a minority of entities, self-assessing its maturity at the highest degree of implementation for physical security policies. Services Australia reported developing maturity, which was below most NCEs’ maturity of ‘managing’ for physical security policies.

Figure 1.2: Reported physical security maturity among non-corporate Commonwealth entities in 2020–21

Source: ANAO based on PSPF maturity assessment reporting data 2020–21.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.15 Physical security arrangements underpin secure delivery of government business through the protection of people, information and physical assets. As Australian Government policy, the PSPF applies to all NCEs subject to the PGPA Act, with accountable authorities responsible for protective security arrangements within their own organisations.

1.16 As the policy owner, AGD has responsibility for whether the PSPF is successful. AGD undertakes its role through provision of general, high-level guidance to entities on the PSPF. AGD also collects and reports entities’ annual self-assessments and information on significant security incidents.

1.17 The Auditor-General has tabled performance audits identifying a low level of oversight and low levels of entity compliance with mandatory policies. This audit will provide assurance about whether AGD is fostering the intended strong security culture through strategic, diligent, and risk-based administration of the PSPF, including by assessing the accuracy of self-reporting of physical policies by two entities.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.18 The audit approach was to assess the effectiveness of AGD’s administration of physical security in the revised PSPF, including as well as compliance with physical security requirements by two entities (Department of Social Services and Services Australia). The ANAO used policy 4 (Security maturity monitoring), policy 15 (Physical security for entity resources) and policy 16 (Entity facilities) to assess this effectiveness.

1.19 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria.

- Has the Attorney-General’s Department effectively administered the Australian Government’s protective security policy framework?

- Are selected entities appropriately monitoring their security maturity and providing a safe and secure physical environment for their people, information and assets?

1.20 The audit did not include examination of the selected entities’ compliance with the pre-October 2018 PSPF or policies 1 to 3 and 5 to 14.

Audit methodology

1.21 The audit involved:

- a review of departmental documentation held by AGD and the selected entities relating to the revised PSPF;

- analysis of entity reporting data collected by AGD from 2018–19 to 2020–21;

- meetings with relevant staff within AGD, selected entities’ Chief Security Officers and other relevant entity staff;

- data analysis and observation of physical security measures at selected entities’ facilities in the ACT and NSW; and

- a survey of Chief Security Officers from 97 NCEs.

1.22 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $497,000.

1.23 The team members for this audit were Natalie Maras, Chay Kulatunge, Amanda Reynolds, Dale Todd, and Corinne Horton.

2. Effectiveness of the Attorney-General’s Department’s administration

Areas examined

This chapter examines the Attorney-General’s Department’s (AGD) administrative arrangements to support the revised Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF).

Conclusion

AGD’s administrative arrangements to support the revised PSPF were largely effective. AGD’s advice to government about the progress of the framework was limited as AGD relied on self-assessment information, which the ANAO has found can be overstated or inaccurate, to accurately reflect the maturity of implementation of revised PSPF requirements. As policy owner, AGD did not monitor compliance with mandatory requirements. AGD provided a variety of support including detailed written guidance that could be better tailored to low-risk and face-to-face service environments. AGD’s role can be strengthened by closer alignment of the self-assessment reporting instrument and policy, and by ensuring that entities understand and follow the mandated security reporting requirements.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation aimed at reconciling and collating significant security incident reporting. The ANAO also identified an opportunity to ensure alignment of the self-assessment questionnaire and PSPF policy requirements.

2.1 The Public Governance Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) requires entities to demonstrate how public resources have been applied to achieve their purposes.

2.2 The Attorney-General’s Directive on the Security of Government Business establishes PSPF as an Australian Government policy.8 The Attorney-General’s Directive also reiterates the PGPA Act requirement for AGD, as policy owner of the PSPF, to develop and refine the policy.

2.3 The ANAO examined whether AGD:

- established fit-for-purpose governance arrangements to support its administration of the PSPF;

- collected information to effectively assess whether the policy objectives of the PSPF are being met; and

- effectively analysed information and reported to government on whether the policy objectives of the PSPF are being met.

Has AGD established fit-for-purpose governance arrangements to support its administration of the PSPF?

AGD largely established fit-for-purpose governance arrangements to support its administration of the PSPF. AGD established governance bodies with defined roles, and it planned to manage risk, refine policies and engage with other entities. AGD did not establish a framework for defining the effectiveness of the revised PSPF. The risk framework has not identified all appropriate risks, including the risk of optimism bias in entities’ self-assessments.

2.4 Sound governance arrangements enable a policy owner to put itself in the best position to report to government on the success or otherwise of its policy. Sound governance arrangements also assist a policy owner to build stakeholder and public confidence in the policy for which there is an expectation of compliance. The ANAO examined whether AGD put in place governance arrangements, and whether these supported the administration of the revised PSPF.

2.5 The Attorney-General’s Directive from October 2018 stated:

The Australian Government, through my department with oversight of the Government Security Committee, will continue to assess emerging security risks and develop and refine protective security policy that promotes efficient secure delivery of government business.9

2.6 AGD developed the PSPF Reforms Implementation Plan 2018 to support its implementation of the revised PSPF. This plan explained that the Attorney-General had portfolio responsibility for protective security and was the ‘final decision maker on protective security policy matters.’ The same plan indicated that the Government Security Committee (GSC) provided ‘strategic oversight’ of whole-of-government protective security policy and promoted the consistent, efficient and effective application of security policies by non-corporate Commonwealth entities (NCEs).

2.7 Under the Administrative Arrangements Orders10, AGD is responsible for protective security policy.11 As set out in AGD’s Corporate Plans from 2018–22 to 2021–25, AGD’s purpose included achieving ‘a just and secure society through the maintenance and improvement of Australia’s law, justice, security and integrity frameworks.’12

2.8 AGD achieved its purpose through five strategic priorities in 2018; six strategic priorities in 2019; and five key activities in 2020 and 2021. AGD positioned the revised PSPF under its strategic ‘integrity’ priorities in 2018 and 2019; and under its ‘administration and implementation of programs and services’ activities in 2020 and 2021.

2.9 According to its terms of reference, the GSC comprises 20 entity members13, with additional entity representatives invited as needed.14 AGD coordinated secretariat support for the GSC, which met as required by its terms of reference in the period October 2018 to December 2021.15 The GSC provided strategic oversight of the PSPF by considering proposed updates to PSPF policies and instructing AGD to consult with other entities on specific matters. AGD informed the Attorney-General of agreed policy revisions and published updates.

Arrangements to assess outcomes of the revised PSPF

2.10 As outlined in paragraph 2.5, AGD’s role in the PSPF is to assess emerging security risks and develop and refine protective security policy that promotes efficient secure delivery of government business. AGD did not develop a strategy to guide its assessment of whether the policy was successful in promoting efficient secure delivery of government business.

2.11 In response to ANAO queries about its reviews of the PSPF, AGD advised ‘over the past 4 years, the PSPF has been the subject of a number of audits and reviews by the ANAO and Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA)’.16 ANAO audits have found that the maturity levels for entities reviewed were below the required PSPF level of ‘managing’ and the reporting framework was not driving sufficient improvement in security. The JCPAA raised concerns about the level of entity compliance with mandatory requirements and the absence of internal assurance.

2.12 AGD’s corporate plans outline AGD’s strategic priorities that support the Attorney-General and assist the Minister. AGD measures the success of its strategic priorities using performance indicators outlined in its corporate plans. Business units are responsible for delivering on performance measures.

2.13 AGD’s Corporate Plan 2018–22 and Corporate Plan 2019–22 included performance measures for the revised PSPF. These performance measures focussed on AGD producing community impact or achieving objectives through entities understanding and applying the PSPF.

2.14 In late 2020, AGD updated its performance reporting framework.17 AGD consolidated its performance measures to focus assessment of policy work at the departmental level. AGD’s Corporate Plan 2020–24 and Corporate Plan 2021–25 no longer include specific performance measures for the PSPF.

2.15 The relevant performance measure for the PSPF in AGD’s Corporate Plan 2021–25 is performance measure 3, relating to the legal and policy framework for which AGD has administrative responsibility. AGD’s target relates to the average performance rating from stakeholders and the effectiveness of advice to the minister.

2.16 AGD advised that the Integrity and Security Division Protective Security Policy team delivers on AGD’s performance measure for the PSPF, being a policy framework relating to criminal justice and national security. The team has a PSPF Quarterly Plan that indicates what will be done, how the team will work as a team, and high-level risks to delivery. The plan does not contain performance targets.

Arrangements to manage risk

2.17 AGD’s corporate plans outline AGD’s arrangements to manage risk. AGD’s Chief Operating Officer is the Chief Risk Officer, accountable to AGD’s Secretary for the implementation and maintenance of the department’s risk management program. The Executive Board monitors the department’s strategic risks, which are also considered as part of business planning, internal audit planning and budget allocation processes. Business units manage risks associated with the department’s workforce, finances, infrastructure, and relationships with third parties.

2.18 The AGD protective security policy team managed risks relating to the PSPF through its PSPF Quarterly Plan and a risk register. This approach was consistent with AGD’s Risk Management Policy and supporting departmental guidance and templates. AGD’s risk register, dated 24 August 2021, reflected 10 risks for the revised PSPF, covering resourcing, access to and compromise of information or data management, and meeting expectations. Five of the 10 risks were rated as ‘low’ and five were rated as ‘medium’.

2.19 AGD implemented treatments to address the risks it identified including:

- provision of a range of policy guidance and mechanisms for NCE feedback (website, PSPF hotline, email and communities of practice discussed in paragraphs 2.23 to 2.25);

- determining the exposure of the reporting portal to cyber-attacks by unauthorised internal and external users; and

- consistent resourcing of the PSPF team to support NCEs and other stakeholders.

2.20 The identified risks and treatments did not include the risk of optimism bias in a self-assessment framework or that entities may not accurately report self-assessment results. Previous ANAO performance audit reports18 and the following chapters (three and four) indicate that this is a risk.

Arrangements to develop and refine protective security policy

2.21 AGD updated the PSPF policies when it identified the need to do so, when Government decisions or other policy changes affected the PSPF, or when requested by the GSC or other key stakeholders.

2.22 Since the revised PSPF commenced, AGD sought GSC approval of refinements to nine of the 16 policies. AGD obtained GSC approval for policy refinements at the second GSC meeting in 2019, 2020 and 2021. There were no refinements to the policies examined in this audit (policies 4, 15, and 16).

Arrangements for stakeholder support and engagement

PSPF website

2.23 The primary purpose of the PSPF website is to make the PSPF policies publicly available, including to NCEs.19 The website provides public access to policies, guides, news, and updates, and provides links to templates, the reporting portal, and a webform for contact with AGD’s PSPF team. AGD’s Protective Security Policy team also manages a protective security policy community on GovTEAMS. Access to this community, which is restricted to government personnel, is available through completion of a form on AGD’s website.

Direct engagement

2.24 AGD engaged directly with entities through its PSPF Hotline. AGD also responded to entity emails through the PSPF mailbox (group email account), which is linked through AGD’s website contact form. PSPF Hotline and PSPF mailbox details were detailed in the Protective Security Guide for Chief Security Officers (CSO).

Forums and communities of practice

2.25 Since launch of the revised PSPF, AGD has established or leveraged existing forums to interact with public officials engaged in security matters across the sector. Stakeholder engagement in these forums and communities of practice raises awareness of PSPF requirements. By participating in these forums and communities, AGD was provided with access to insights about security culture in different entities, including issues of common concern, risk information, new and emerging threats, as well as access to products used to manage risks and address particular security concerns. Table 2.1 summarises AGD’s main engagements.

Table 2.1: AGD stakeholder forums and communities of practice 2019–2021

|

Forum/ Community of Practice |

Purpose |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

|

Personnel Security Community of Practice |

Provide entities with an opportunity to increase their maturity level by discussing issues, engaging on common risk concerns, identify new and emerging threats, and access and share products that may assist to address particular security concerns. |

February April May August September Novembera |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Security Culture Community of Practice |

Provide entities with an opportunity to increase their maturity level by discussing issues, engaging on common risk concerns, identify new and emerging threats, and access and share products that may assist to address particular security concerns. |

March May September |

Nil |

Nil |

|

Vetting Officers Community of Practice/Vetting Policy Forum |

Provide entities with an opportunity to increase their maturity level by discussing issues, engaging on common risk concerns, identify new and emerging threats, and access and share products that may assist to address particular security concerns. |

March May |

Julyb October |

May |

|

Chief Security Officer (CSO) Forum |

CSOs are the Australian Government’s security custodians. This forum supports CSOs to implement the PSPF and foster a strong security culture in their entity. |

May August November |

Nilc |

December |

|

PSPF Reporting Forum |

Support Commonwealth entities to complete and submit their annual security maturity self-assessment online, access benchmarking reports and report significant security incidents. |

July Augustd |

February June |

March July |

|

State and Territory Representatives Meetings |

Discuss protective security issues in each jurisdiction with Commonwealth representatives and counterparts in New Zealand. |

October |

Nil |

December |

Note a: AGD disbanded the Personnel Security Community of Practice in November 2019.

Note b: In July 2020, the Vetting Officer Community of Practice was replaced by the Vetting Policy Forum.

Note c: During the pandemic, AGD issued CSO newsletters instead of holding forums.

Note d: The August reporting forum was only for CSOs to assist them in interpreting their entity’s security maturity results.

Source: ANAO analysis.

Chief Security Officer satisfaction with AGD interactions

2.26 The ANAO conducted a survey of CSOs of the 97 NCEs who complete annual maturity assessments for the PSPF. A total of 39 (40 per cent) CSOs responded.

2.27 The ANAO’s survey indicated that the majority of CSOs interact with AGD on a six-monthly or yearly basis for advice about the PSPF, mainly during peak reporting time. In addition:

- 90 per cent of CSOs were very satisfied or somewhat satisfied with AGD’s responsiveness;

- 85 per cent of CSOs were very satisfied or somewhat satisfied with the clarity of AGD guidance material;

- 92 per cent of CSOs were very satisfied or somewhat satisfied with the comprehensiveness of AGD guidance; and

- 67 per cent of CSOs were satisfied that AGD understands their needs.

2.28 Less satisfied CSOs advised that AGD could improve the tailoring of advice. Some entity CSOs considered that AGD’s ‘one size fits all’ approach to PSPF advice and guidance did not take proper account of the complexity of entity circumstances, or the compliance burden on small entities required to complete the annual questionnaire. Some entity CSOs considered that AGD guidance is not well-tailored to face-to-face service provision. Some entity CSOs noted that the face-to-face forums held by AGD were useful, however these forums ceased when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Guidance on protecting people comprises three of 85 paragraphs in PSPF policy 15. The paragraphs in the PSPF guidance mainly refer to the Work Health and Safety Act 2011 and recommend that entities implement appropriate physical security measures.

2.29 AGD advised that the PSPF has been deliberately drafted not to duplicate other government policies, and as such, refers to any relevant policies such as the Work Health and Safety Act 2011 and provides additional and complementary protective security guidance where required. AGD also advised that specific guidance was developed and distributed to entities to support home-based work, adapting to the COVID-19 pandemic, and return-to-work arrangements.

Has AGD collected information to effectively assess whether the policy objectives of the PSPF are being met?

AGD collected annual entity self-assessments. In the context of indications that self-assessment information may not be accurate, including discrepancies in the reporting of significant security incidents, the use of self-assessment information to assess the effectiveness of the PSPF is limited.

2.30 Information collected by a policy owner assists in determining if the entities required to apply the policy are meeting requirements. Information collected can also assist a policy owner in determining whether contrary evidence exists where the policy owner relies on self-assertions by the entities. This section examines whether AGD collected the information it would need to effectively assess the success of the PSPF for which it is responsible.

Planning for collection of information

2.31 Before implementing the revised PSPF, AGD planned to collect self-assessment reports as the most effective and efficient way to provide assurance to government that effective protective security arrangements were in place. In proposing the self-assessment approach to the GSC in December 2017, AGD recognised that self-assessment is subjective. AGD also recognised that entities are in the best position to report on security risks impacting PSPF implementation because entities have the most comprehensive knowledge of their security risk environment.

2.32 AGD envisaged accountability checks on self-assessments in the form of approvals of entity reports from the entities’ accountable authorities and ministers. AGD proposed to the GSC the following additional accountability measures:

- the model more expressly requires entities to demonstrate a cycle of security planning, monitoring, and reporting each year to meet outcomes;

- reporting includes an explanation of security risk context together with a summary of how key risks for entities were managed over the period; and

- the model will require supporting evidence to be provided to validate responses where appropriate.

2.33 The self-assessment questionnaire contains questions, including free text fields, for entities to summarise their risks, explain their management, and evidence. AGD has not undertaken actions to validate the responses provided by entities and is reliant on self-assessment information to ‘assess emerging security risks’ and ‘refine protective security policy’ as envisaged by the Attorney-General’s Directive. As outlined in paragraph 2.11, ANAO audits have identified issues with the accuracy of entity reporting.

2.34 AGD advised that ‘the PSPF does not require AGD to engage in any activities that would involve assessing, validating, or providing assurance of the reliability or accuracy of entity self-assessments’. In addition, it was not a function that the Australian Government had ‘asked the department to perform’.

Self-assessment collection instrument

2.35 AGD collected self-assessed maturity ratings and comments from entities using a questionnaire-style instrument accessible through the PSPF online reporting portal or offline reporting template.20 The questionnaire comprised 17 mandatory modules — one for each of the 16 PSPF policies and a summary module.

2.36 During meetings with the ANAO’s survey respondents, two entities observed there was a mismatch between AGD’s questionnaire and policy requirements.

2.37 The reporting questions for the revised PSPF were developed between 2017 and 2019 with input from workshops and working groups of representatives from up to 24 entities. The working groups were guided by the PSPF Reporting Reform Project Plan. On 6 June 2019, the GSC nominated a group of Senior Executive representatives from 15 entities to consider the assessment questions.21 AGD was unable to produce any records of deliberations about specific language or alignment of assessment questions to policy language.

2.38 AGD advised that it has not changed questionnaire questions for policies 4, 15, and 16 since the working group formed these questions in 2019. Further, to preserve the baseline for year-to-year comparison, AGD preferred not to change assessment questions. AGD also considered there was no need for AGD to map questionnaire questions to the PSPF policy requirements because AGD’s reporting portal survey confirmed for AGD that 88 per cent of 484 respondents were satisfied that questions clearly aligned with policy requirements.

2.39 The ANAO compared core requirements in PSPF policy 4, 15 and 16 with the equivalent questions in AGD’s 2019–20 questionnaire. The comparison showed 49 inconsistencies between requirements expressed in both documents, 23 of which could be construed to materially overstate, understate, or omit policy requirements.

2.40 The ANAO suggests that AGD undertake a review of questions in the questionnaire instrument that have not already been amended by the GSC, to ensure that results collected with the instrument align with all aspects and the intent of each policy.

Collection of significant security incident reports

2.41 Since 1 October 2018, the PSPF has required entities to report significant22 or reportable security incidents to the relevant lead security authority and other affected entities at the time they occur. Entities are also required to complete the Australian Signals Directorate’s annual cyber security survey.

2.42 AGD guidance provides:

Information gathered on significant security incidents assists the Attorney-General’s Department to:

a. determine the adequacy of protective security policies

b. provide an insight into entity security culture

c. identify potential vulnerabilities in government security awareness training to inform whole-of-government security outreach activities.23

2.43 Significant security incidents can be reported to AGD through the PSPF Reporting Portal, by email, or by telephone to the PSPF Hotline. AGD advised the ANAO that significant security incidents can also be reported ‘where appropriate, via a classified system’ although this is not described in the guidance material.

2.44 Since 2019, AGD has maintained a log of significant security incidents that have been reported. The log captures 14 significant security incidents reported to AGD between 2019 and 2021.24 ANAO analysis of NCE self-assessment reports shows that entities experienced more significant security incidents than are captured in AGD’s log, and the log does not contain all incidents that were reported to AGD. One entity reported in its self-assessment that it had experienced 42 significant security incidents that it did not report to AGD. Another entity did not report to AGD because it considered the portal inappropriately security classified.

2.45 In July 2021, AGD reminded entities of the requirement to report significant security incidents. AGD updated guidance material on significant security incident reporting on 21 April 2020; and updated the significant security incident reporting template on 8 June 2021.

2.46 AGD can receive reporting on significant security incidents from a variety of sources as outlined previously, however, this information is not collated within its log of significant security incidents. This limits AGD’s ability to meet it intended role as outlined in its guidance for ‘Policy 5, Reporting on Security’. Reviewing and reconciling security incident reporting data would better inform AGD’s assessments of whether PSPF guidance has been effective in supporting entities to protect their people, information, and assets.

Recommendation no.1

2.47 The Attorney-General’s Department review, reconcile and collate all significant security incident reporting data to inform assessments of whether the PSPF adequately supports entities to protect their people, information, and assets.

Attorney-General’s Department response: Agreed.

2.48 The Attorney-General’s Department agrees to strengthen the approach to security incident reporting. The department reviews the data it collects from significant security incident reports it receives in accordance with PSPF policy 5: Reporting on security. The department uses that data to identify lessons learned and consider improvements to the PSPF. The department will undertake further outreach and awareness-building activities with entities and increase whole-of-government visibility of security incident reports to drive continuous improvement across the system. Implementation of this recommendation will build on recent departmental initiatives to improve security incident reporting which included regularly advising entities of their obligations, providing advice and transitioning to an online reporting tool. The new reporting tool streamlines reporting for entities, ensures the reporting entity has met their reporting and referral obligations, and provides a uniform data source to improve analysis by the department and inform updates to the PSPF.

Has AGD effectively analysed information and reported to government and the public on whether the policy objectives of the PSPF are being met?

AGD was effective in analysing completeness of responses. AGD did not collect information to provide assurance over the self-assessment responses provided by entities. Reports to government and the public on the Australian Government’s security culture and maturity were solely based on entity self-assessments. This reduces the level of assurance AGD has on its advice on whether the policy objectives of the PSPF are being met.

2.49 Appropriate analysis of relevant information enables a policy owner to provide evidence-based advice to the Australian Government and the public on the extent to which its policy is achieving the desired outcome. This section examines whether AGD’s reports to government and the public were supported by effective analysis.

Analysis of information

2.50 As discussed in paragraphs 2.31 and 2.32, AGD did not collect information to analyse accuracy or provide assurance over self-assessment information. Consistent with its self-assessment approach, AGD accepted information from entities as true and correct at the time of submission.

2.51 AGD reviews the completeness of responses and if it finds missing information, returns the incomplete submissions to NCEs for completion. The reporting portal captured information about AGD’s reasons for returned submissions. Commonly missing information for which AGD returned submissions included the APS level of the submitting CSO, incomplete modules, missing rationales, missing strategies for improving ‘ad hoc’ or ‘developing’ modules, unspecified timeframes, or undefined key risks. Table 2.2 summarises the number of incomplete self-assessments that AGD returned for completion.

Table 2.2: Number of submissions returned by AGD for completion by NCEs

|

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

2020–21 |

|

78 of 98 (80%) |

45 of 97 (46%) |

8 of 97 (8%) |

Source: ANAO based on AGD documentation.

2.52 AGD invited entities to complete several free text fields in their annual self-assessment reports. These fields captured the entities’ rationale for its self-assessed maturity rating, issues, and strategies to improve their treatment of risks as well as summary comments. Consistent with its advice that ‘AGD did not collect information with any intention to provide assurance over self-assessment information’, the ANAO was unable to identify analysis of free text fields. AGD advised the ANAO:

It is not correct to say that AGD does not intend to analyse information. AGD intends to, and does, analyse the information provided by entities, including in the free text fields, to identify the common reasons for low maturity, blockers to improving maturity, and key risks.25

2.53 The ANAO analysed free text fields in 2020–21 self-assessment reports for 97 entities. The analysis showed that regardless of size or function, NCEs considered cyber threats in their top two threats. Besides cyber, the analysis of free text fields showed stratification of themes by NCE size and function. Larger entities considered foreign interference among their top threats whereas medium NCEs rated malicious motivated individuals or groups in their top threats; and small NCEs rated unauthorised access or disclosure of information in their top threats. By function, regulatory NCEs rated their transition to remote or working from home arrangements as a top threat; smaller operational NCEs rated staff understanding of compliance with security requirements as a top threat; and policy NCEs rated foreign interference as a top threat.

Public reports

2.54 Three years after the implementation of the revised PSPF, AGD has had an opportunity to compare three years of self-assessment information and consider whether the revised PSPF was meeting objectives. As outlined in Table 1.1 in Chapter 1, AGD has publicly reported twice on the revised PSPF.

2.55 Before AGD had multiple year results to compare, AGD had reported in relation to the revised PSPF:

The results are promising. Most entities have substantially implemented the core and supporting requirements of the Protective Security Policy Framework. Entities are actively engaged with risk and have a strong understanding of their threat environments. They demonstrate a commitment to improving the security of their information, as well as their people and assets.26

2.56 AGD’s public reports collated NCE maturity status information from the annual questionnaires and present summary graphs of maturity for each of the 16 policies. The reports refer to the work of other entities, such as the Australian Signals Directorate’s Australian Cyber Security Centre, in identifying threats. The reports did not refer to any work that AGD did to identify emerging security risks.

2.57 AGD’s 2018–19 report concluded:

While some entities require additional supports, these results demonstrate that entities are working to continually improve their security posture, and demonstrate a sound understanding of the threat environment in which they operate.27

2.58 AGD’s 2019–20 report concluded:

Entities are building resilience, adapting to the rapidly changing environment in which they operate, and continually working to improve their security posture by prioritising efforts to target areas of low security maturity.28

2.59 In publishing the 2019–20 report on 8 June 2021, AGD noted that ‘entities reported improvement across all four security outcomes and the majority of entities (99 per cent) reported they had substantially implemented the core and supporting PSPF requirements, up from 89 per cent in 2018–19.’ AGD noted that the 2019–20 report ‘provides assurance to government and the Australian public that entities are implementing security measures that proportionately address their unique security risk environments.’

2.60 The public reports did not contain any explicit statement to indicate that information is based only on self-assessment information and AGD had not independently verified that entities are building resilience, adapting, and continually working to improve their security posture. By comparison, the publicly available Commonwealth Security Posture Report (produced by the Australian Signals Directorate29), which refers to the AGD maturity data for policy 10, stated that some ‘information in the report is self-reported and has not been independently verified’.

2.61 In response to the ANAO’s queries about the transparency of AGD’s reliance on self-assessment reports, AGD advised the ANAO in February 2022 that:

The department has never suggested that the self-assessments are independently verified. On the contrary, the 2019–20 PSPF assessment report explicitly stated it was based on consolidated entity self-assessments. Similarly, the department’s ministerial submission that sought approval to publish the 2019–20 assessment report stated that the department used the self-assessments submitted by entities to prepare the report.

Reporting to Government

2.62 AGD reported to the Attorney-General, seeking ministerial approval for GSC-approved updates to the PSPF and annual reports prior to publication on the PSPF website.

2.63 AGD’s advice to the Attorney-General that security maturity is improving was based exclusively on self-assessment reports of entities. AGD did not use other public information (such as NCE corporate information or media), or information from its engagements with stakeholders to make evidence-based reports to the Attorney-General about the sufficiency of the mandatory reporting framework in meeting the objectives of the PSPF.

2.64 On 18 September 2020, AGD advised the Attorney-General that it had developed minor and technical amendments to six of the 16 PSPF core and supporting requirements and guidelines to respond to emerging security risks. The advice did not elaborate on what the emerging security risks were; how emerging security risks were identified; or how the amendments responded to identified risks.

2.65 While seeking the Attorney-General’s approval to publish the 2018–19 PSPF assessment report on the PSPF website, on 3 December 2020 AGD summarised the consolidated view of protective security self-assessments. AGD advised that its ‘experience with the 2018–19 report has indicated it would be desirable to make further refinements to the maturity model to better represent progress by entities and the achievement of substantial maturity.’ AGD stated ‘we will undertake that work now’. AGD also advised that it is working with the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation and the Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC) to develop and implement strategies to assist entities to improve security maturity results, including:

- biannual briefings on the threat environment;

- sharing PSPF results on cyber security requirements with ACSC; and

- policy and implementation advice and assistance offered to entities that self-assessed as ‘ad hoc’.

2.66 On 24 May 2021, AGD reported to the Attorney-General that ‘there was a clear increase in security maturity during 2019–20’ and ‘[e]ntities achieved improvements in their level of implementation’. AGD expected that entities ‘will continue to improve their maturity year-on-year’. These statements repeat publicly available summaries of self-assessment reports. AGD also noted that with two years of reporting data available to it, the department was ‘considering whether the PSPF maturity model meets its purpose and whether any enhancement could be made to improve the model.’

Improvements to assurance of self-reporting data

2.67 In March 2021, AGD commenced a procurement process for evaluation services addressing how the PSPF maturity model could be improved. The evaluation did not address the whole PSPF framework and was not intended to determine if alternatives to the self-assessment model should be implemented.

2.68 The evaluation report was delivered in June 2021. To improve the model’s design, the report made 16 recommendations including for self-assessment accuracy; guidance, education, and support; and reporting process and reporting outputs. AGD advised the Attorney-General that findings will inform updates for the 2020–21 PSPF reporting period.

2.69 AGD responded to the report’s recommendations by taking to the GSC proposals for changes to self-assessment reporting, guidance, peer support and external moderation. Minutes from the 20 July 2021 meeting of the GSC record that AGD was working on updates to the reporting portal. The GSC noted AGD’s proposal to formalise the assurance arrangements undertaken by entities with ‘an additional question about the accuracy of the self-assessment.’ On 24 November 2021, the GSC agreed to the following action items for AGD, without accompanying timeframes.

- AGD to update the PSPF maturity model, including changing the calculation methodology, a review of the yes or no questions, and updating maturity level descriptors.

- AGD to progress work on a new starter guide to reporting, and Best Practice Evidence Guide to support entities in improving the accuracy of their self-assessments.

- AGD to develop an opt-in peer review option to support information sharing and explore a pressure testing framework.

3. Department of Social Services’ security maturity monitoring and provision of a secure physical environment

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of Social Services (DSS) has implemented the requirements for security maturity monitoring, physical security measures for entities and protective security measures at its facilities under the revised Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF).

Conclusion

DSS was largely effective in implementing requirements that it established for itself under the PSPF at the ‘managing’ and ‘embedded’ maturity levels. DSS implemented a variety of physical security measures and integrated physical security considerations into its processes. DSS did not accurately report its maturity level as ‘embedded’ for policies 4, 15 and 16 because it did not always follow its plan, and documentary evidence of the certification authority’s satisfaction with physical security requirements was incomplete.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at adherence to plans for assessing and reporting progress against indicators set in the security plan; and completion of certification and accreditation and documentation in accordance with core requirements of the PSPF.

The ANAO made two suggestions aimed at consistently documenting responsibilities for implementing the PSPF at co-location sites; and using a broader variety of performance data to evidence its assessments of risk culture.

3.1 The PSPF requires entities to comply with physical security requirements in policy 4 (security maturity monitoring), policy 15 (physical security for entity resources) and policy 16 (entity facilities).

3.2 To assess whether DSS met requirements, the ANAO examined whether:

- assessments of security capability and risk culture were aligned with security plans and demonstrated routine consideration of progress against set goals;

- risks were assessed and physical security measures were selected and implemented at facilities visited by the ANAO; and

- protective security was fully integrated into planning, selection, modification and design of facilities and certifications and accreditations were undertaken.

Did DSS effectively implement security maturity monitoring at the ‘managing’ and ‘embedded’ maturity level?

DSS was largely effective at considering its progress against the goals and strategic objectives in its security plans. DSS had established a plan with goals and objectives and monitoring bodies received reports about security capability and risk culture. DSS’ reported maturity levels were inaccurate because monitoring was not consistently against the indicators in the security plan and did not cover co-location sites. DSS captured and analysed performance data and used a limited range of performance data to inform change.

3.3 The PSPF policy 4 core requirement is that each entity must assess the maturity of its security capability and risk culture by considering its progress against the goals and strategic objectives identified in its security plan. The entity should set indicators in its entity security plan against which to evidence and document its assessment. The supporting requirement of this policy is that entities document and evidence their assessment of the entity’s security maturity. Monitoring security maturity is an ongoing process that involves routine assessment of security capability and risk culture against set indicators.

3.4 In 2018–19, DSS reported in its PSPF self-assessment that it had a maturity level of ‘managing’. At this maturity level, the entity’s implementation of policy 4 should demonstrate a consistent and defined approach to monitoring the entity’s security performance which is tailored to the entity’s risk environment. The entity should have clearly defined its security goals and objectives in the security plan, and performance should be tracked and measured to assess security capability and risk culture maturity.

3.5 In 2019–20 and 2020–21, DSS reported that it had reached an ‘embedded’ maturity level. This maturity level means that the entity actively engages in ongoing monitoring and improvement of security capability and culture through long-term planning to predict and prepare for security challenges. It also means that performance data is captured, analysed, and informs change.

3.6 The ANAO examined DSS’ security plans, documentation, and evidence of its implementation of policy 4, including its assessments of security capability and risk culture maturity, at the reported levels. Table 3.1 outlines findings for policy 4.

Table 3.1: DSS’ implementation of policy 4

|

Policy requirement |

ANAO assessment |

ANAO comment |

|

Assess the maturity of security capability against the goals and strategic objectives identified in its security plan. |

▲ |

In 2018–19 DSS undertook assessments. Assessments were not against goals and objectives in its security plan. |

|

▲ |

In 2019–20 and 2020–21 DSS’ assessments were not always tracked against its security goals and indicators. The frequency of DSS’ consideration of its progress was inconsistent. |

|

|

Assess the maturity of risk culture by considering its progress against the goals and strategic objectives identified in its security plan. |

▲ |

In 2018–19 DSS assessed its risk culture. Its assessments were not clearly linked to the security plan, making it difficult for DSS to show that it considered its progress against the goals and strategic objectives in its security plan. |

|

▲ |

In 2019–20 and 2020–21 DSS developed an enterprise-wide Threat and Vulnerability Risk Assessment to predict and prepare for security challenges. Its monitoring was not aligned to the security plan and infrequent. |

|

Key: ◆ Appropriately implemented. ▲ Partly implemented. ■ Not implemented.

Source: ANAO analysis of DSS activities.

Monitoring of security capability and risk culture in 2018–19

3.7 DSS had a Security Plan 2018–2020 that was not finalised. In this plan, DSS clearly defined security goals for the period between 1 July 2018 and 30 June 2019. Security goals address both DSS’ security capability and risk culture. The Security Plan 2018–2020 also contained key actions and measures of success for each goal.

3.8 DSS’ Security Plan 2018–2020 did not include internal audits as part of its monitoring activities. DSS undertook an internal audit on its compliance with the PSPF between October 2018 and April 2019. The internal audit found that for PSPF policy 4, DSS was achieving a ‘developing’ maturity level because it had not undertaken an annual security capability and enterprise-wide security risk assessment as stated in its Security Plan 2018–2020.

3.9 DSS upgraded its self-assessment to ‘managing’ based on enhancements to its security governance by appointing a Deputy Secretary CSO, incorporating security policies and guidelines into procurement processes, and implementing a designated assessment register. DSS had agreed to the recommendation in the internal audit — that the Security Plan should form the basis for DSS’ security reporting framework — and it was implemented in the Security Plan 2019–21. An accurate self-assessment would have been for DSS to maintain the ‘developing’ maturity level until it had implemented the recommendation, rather than when it had agreed to the recommendation. As such, DSS’ self-assessment was inflated and unsubstantiated at the ‘managing’ level for 2018–19.

3.10 DSS established a Security Working Group (SWG)30 to monitor the strategic direction and execution of all DSS’ security functions to ensure that security risks to its people, information and resources are managed effectively. DSS planned for the SWG to meet monthly. The SWG received two reports to monitor its security capability and risk culture. These were:

- monthly reports which covered security capability and risk culture related topics, including preparation of an annual enterprise-wide security risk assessment, conduct of protective security reviews for facilities and risk training for the DSS security team; and

- occasional Security Action Plan updates, which recorded the progress of security activities.

3.11 The SWG meetings and monthly reports did not occur monthly as intended. This was partly due to SWG transitioning to the Implementation Committee from December 2018. The Implementation Committee is an advisory body that reports to the Secretary through the Executive Management Group.31 Overall, monitoring activities and reports were available for most of the year, except for May and June 2019.

3.12 The activities addressed in monthly reports did not explicitly align to DSS’ security goals, and monthly reports did not comment on DSS’ overall progress, making it difficult for DSS to substantiate that its assessments of security maturity related to its security plan. SWG meetings included discussion of security activities. These meetings did not directly cover the key actions and measures of success from the Security Plan 2018–2020.

Monitoring of security capability and risk culture in 2019–20 and 2020–21

3.13 In its Security Plan 2019–21, DSS defined its strategic objective to: ‘protect our people, information, and assets so that the department is able to deliver on our mission to improve the wellbeing of individuals and families in Australian communities’. DSS clearly defined its security goals, which aligned to the four security outcome themes of the PSPF.32 As shown in Table 3.2, DSS’ key performance indicators address monitoring and assessment for both security capability and risk culture.

Table 3.2: Security goals, key actions and performance indicators related to security capability for 2019–20 and 2020–21

|

Security goal |

Key actions |

Key performance indicators |

|

Governance — Manage security risks and support a positive security culture in an appropriately mature manner ensuring clear lines of accountability, sound planning, investigation and response, assurance and review processes and proportionate reporting. |

Bi-annually review and update the Security Plan and associated Security Risk Assessment for the Secretary’s approval. |

The Security Plan, Security Risk Assessment, and associated security risk mitigations are approved by the Secretary. |

|

Monitor our performance against the actions identified in the Security Plan through the Implementation Committee and Executive Management Group on a quarterly basis. |

Security performance reported quarterly to Implementation Committee. |

|

|

Improvements in compliance with security requirements noted between reporting periods. |

||

|

Performance reporting includes number of security incidents and staff participation in mandatory annual security training (at departmental, stream and group levels). |

100% of staff complete the security awareness training by 30 June 2020 and 2021. |

|

|

Physical security — Provide a safe and secure physical environment for our people, information and assets. |

Undertake bi-annual Threat and Vulnerability Assessments (T&VA) and Security Zone Assessments for all facilities.

|

All facilities are certified in accordance with Physical Security Guidelines contained in the PSPF. |

|

Risks identified through T&VA are mitigated to as low as possible in accordance with security risk tolerance. |

||

|

Undertake a rolling six-month security asset audit and maintenance program |

100% of security assets are sighted. |

|

|

100% of assets in use are certified as compliant with Security Construction Equipment Committee (SCEC) requirements.a |

||

|

Develop and implement risk assessment policies and procedures for staff travelling off-site for work, or working in high-risk environments (remote communities, service providers, hostile or highly political community environments). |

100% of staff are briefed and familiar with standard operating procedures on working in high-risk environments. |

|

Source: DSS Security Plan 2019–21.

3.14 At DSS’ self-reported ‘embedded’ maturity level, DSS should have actively engaged in ongoing monitoring and improvement of security capability and risk culture through long-term planning to predict and prepare for security challenges. DSS engaged in long-term planning to predict and prepare for security challenges when it developed an enterprise-wide Threat and Vulnerability Risk Assessment as part of its Security Plan 2019–21 (discussed at paragraphs 3.29 and 3.30). It identified risks, included risk analysis and considered risk mitigation measures.

3.15 DSS did not always monitor its security capability and risk culture against the key actions and measures of success that it established in its Security Plan 2019–21 (shown in Table 3.2). DSS prepared four types of security reports to document its assessments. One of these (Security Goal Progress Report) was explicitly structured to align with the indicators from the Security Plan 2019–21. The reports covered general progress for activities related to governance and physical security:

- Security Goals Progress Reports — provided commentary on the implementation status of key performance indicators from the security plan;

- Security Balanced Scorecards — tracked the status and trends of DSS’ maturity levels against each PSPF policies. It reported on key activities conducted under each security goal. The Security Balanced Scorecards had a more succinct reporting format compared to the Security Goals Progress Reports;

- Quarterly Workforce Report — included a security component, which covered security incidents, clear desk inspections, key security projects underway, status of staff security clearances, and status of zone certifications; and

- Security Plan Quarterly Updates — covered updates on the implementation of some of the measures outlined in the Security Plan.

3.16 In November 2020, DSS established the Security Governance Committee to monitor DSS’ performance against the security plan and updated risk and vulnerability assessments. Minutes indicate that the committee discussed items such as progress against elements of the DSS Security Plan 2019–21, trends in security maturity and security reports. During 2020–21, DSS regularly monitored its Threat and Vulnerability Risk Assessment at meetings of the Security Governance Committee and through some of DSS’ security reports.

3.17 DSS’ monitoring activities over 2019–20 and 2020–21 is shown at Figure 3.1. The Security Governance Committee did not meet quarterly as planned and DSS’ Security Plan Quarterly Update was not prepared quarterly. During 2019–20, one Security Goal Progress Report was prepared, and the Security Working Group and its successor the Security Governance Committee did not meet during 2019–20. In 2020–21, DSS’ monitoring activities were concentrated towards the second half of the year. The infrequency and gaps in DSS’ monitoring make it difficult for DSS to substantiate that it was actively engaged in ongoing monitoring.

Figure 3.1: DSS’ monitoring of security maturity in 2019–20 and 2020–21

Source: ANAO analysis based on DSS documentation.

Recommendation no.2

3.18 The Department of Social Services review and adhere to its planned schedules for assessment and reporting of progress against actions and measures of success in the department’s security plan.

Department of Social Services response: Agreed.

3.19 The department has revised its assessment and reporting documentation to clearly demonstrate progress directly against the measures of success contained in the department’s security plan. The department is committed to adhering to governance and oversight arrangements established in the security plan as a key mechanism for strengthening performance monitoring, reporting and continual improvement.