Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of the Renewable Energy Demonstration Program

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism’s administration of the Renewable Energy Demonstration Program (REDP), including progress towards achieving the programʹs objectives.

The audit examined whether the department had established effective arrangements to:

- implement REDP, including governance arrangements;

- assess applications for REDP funding assistance and recommend projects to the Minister for funding approval;

- negotiate funding agreements for approved projects; and

- monitor progress towards the achievement of the REDP objective.

Summary

Introduction

1. Governments both nationally and internationally have acknowledged that climate change, which is primarily associated with the increase in greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere, has the potential to adversely impact on economic, social and environmental systems.1

2. In December 2007, Australia ratified the Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, agreeing to limit annual greenhouse gas emissions to an average of 108 per cent of 1990 levels during the Kyoto period (2008 to 2012). The Australian Government has also committed to a long-term target to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 80 per cent below 2000 levels by 2050.2

3. There are a range of options available to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, including: energy conservation; improving energy efficiency and shifting power generation to renewable energy sources. Renewable energy has a key role in mitigating climate change, with wider benefits, including: contributions to social and economic development; energy access; secure energy supply and reducing negative impacts on the environment and health.3 Within this context, the Australian Government has established a range of programs and initiatives aimed at mitigating the impact of climate change and promoting the use of renewable energy.

Renewable energy

4. Renewable energy is energy sourced from the natural environment that can be replenished at a sustainable rate-equal to or greater than the rate of use unlike fossil fuels, which have a finite supply and cannot be replenished. The generation of electricity from renewable energy does not generally involve the combustion of fossil fuels and the production of greenhouse gases.4 Renewable energy is a cleaner energy source with less impact on the environment. However, the establishment of any new technology to generate power is potentially more expensive than existing technology. There are various stages in the development of renewable energy technology for power generation, including: research and development; pilot; demonstration; and commercialisation.

5. As a technology moves along the development continuum, the technical risk progressively declines, from high risk at the research and development stage, to low risk at the commercial stage. However, the financial risk may increase at the demonstration stage, depending on the size of the installation and level of funding required for demonstration. The expected costs of a renewable energy technology typically rise during the research, development and demonstration phases, but decline during commercial deployment.5 As market drivers alone are not always sufficient to support an optimal innovation effort, government assistance for the renewable energy industry aims to address market failure.

6. Most of Australia's electricity is generated from fossil fuels, but the proportion generated from renewable sources is increasing. In 2009-10, Australia produced 241 566 gigawatt hours of electricity, with 91.8 per cent produced from fossil fuels6, and 8.2 per cent from renewables, such as hydro, wind, biofuel and solar.7 Estimated electricity generation from wind and solar energy increased in 2009-10 by 26 per cent and 78 per cent respectively.

7. The Australian Government has committed to increase the proportion of energy generated from renewable sources and to reduce dependency on non-renewable energy sources through its 20 per cent Renewable Energy Target.8 The objective of the Renewable Energy Target is to supply 20 per cent of Australia's electricity, approximately 60 000 gigawatt hours, from renewable energy sources by 2020.9 The Government has stated that renewable energy is an essential part of Australia's low emissions energy mix and has the potential to play a key role in reducing Australia's greenhouse gas emissions and in mitigating the impact of climate change.10

8. To contribute to the achievement of the Renewable Energy Target and to maintain a strong and competitive low emission economy, the Australian Labor Party announced the Renewable Energy Fund as an election commitment in 2007 with total funding of $500 million for the period 2009-10 to 2014-15.11 As part of the 2008 Budget, the Minister for Resources and Energy12 (the Minister) announced that the Renewable Energy Fund would comprise the:

- Renewable Energy Demonstration Program ($435 million);

- Geothermal Drilling Program ($50 million); and

- Second Generation (Gen2) Biofuels Research and Development Program ($15 million).13

9. The Government also announced in the 2008 Budget that the implementation of the Renewable Energy Demonstration Program (REDP) would be delayed until the following financial year, with funding to be appropriated from 1 July 2009. However, in December 2008, the Government announced that the Renewable Energy Fund would be brought forward for investment in the subsequent 18 months. The purpose of this acceleration was to stimulate the economy during the global financial crisis and to create low-pollution jobs for the future.

Renewable Energy Demonstration Program

10. REDP is designed to accelerate the commercialisation and deployment of new renewable energy technologies for power generation in Australia by assisting the demonstration of these technologies on a commercial scale.14 To be eligible for support under REDP, applicants were required to demonstrate that they satisfied the applicant and project eligibility criteria. Proposed projects were required to be: large-scale renewable energy demonstration projects for power generation meeting the objective and outcomes of REDP15; and involve eligible renewable energy generation technologies.

11. The Minister launched REDP on 20 February 2009 as a merit-based competitive grants program, with a proposed funding range of $50 million to $100 million for individual projects. As previously mentioned, the Australian Government initially made available $435 million16 under the program to stimulate investment in renewable energy technology for power generation. The private sector is expected to contribute at least $2 for every $1 provided by the program.17

12. The Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism (RET) is the administering agency for REDP.18 While the department is responsible for the design and implementation of the program, the Minister appointed an independent advisory committee, the Renewable Energy Committee (REC), to assess REDP applications against the merit criteria and make recommendations to him for funding those projects that would enable the program to meet its objectives. RET provided secretariat support for REC, which included managing the registration of interest process, assessing applications against the eligibility criteria and coordinating technical and financial assessments. The department is also responsible for negotiating and managing the deeds of agreement.

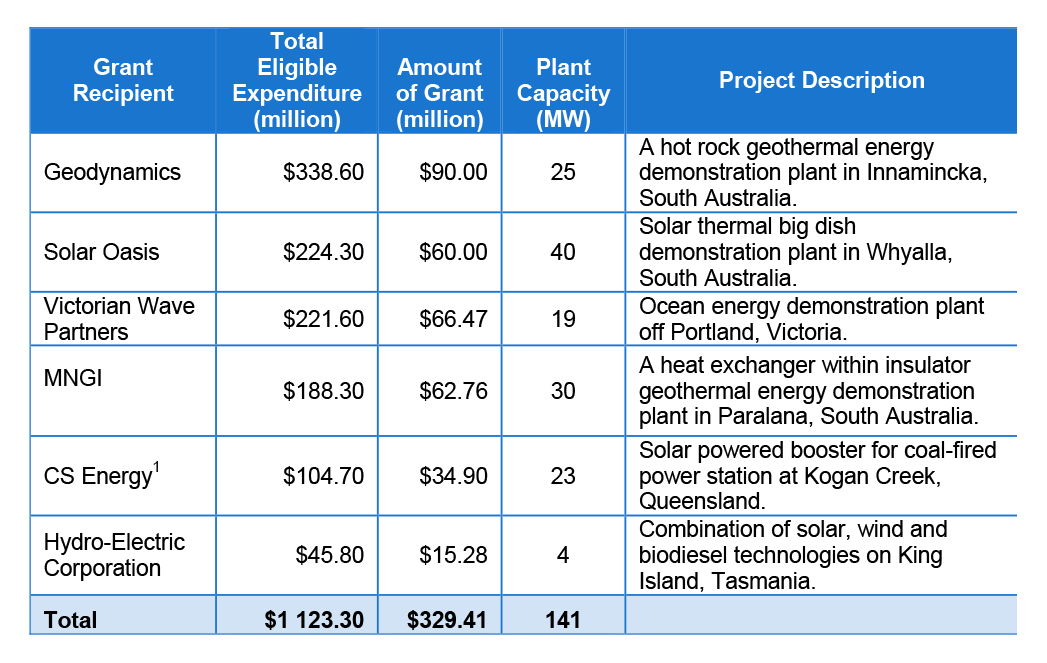

13. RET received 63 applications, of which 61 were considered by the department to be eligible for REDP funding (36 non-solar and 25 solar). On 6 November 2009, the Minister announced grants for non-solar technologies totalling $234.5 million for two geothermal energy projects, one wave energy project and one combination energy project. On 11 May 2010, grants for two solar technology projects totalling $91.9 million were announced by the Minister. Details of all of these projects, including expenditure and capacity, are provided in Table S 1.

Table S 1 Funded non-solar and solar projects

Program developments

14. As part of the 2009-10 Federal Budget, the Government announced the establishment of the Australian Centre for Renewable Energy (ACRE).19 ACRE comprised: a statutory board; a Chief Executive Officer, who was an SES officer appointed by RET's Secretary; and departmental support staff. ACRE was established to provide guidance to governments and the community on renewable energy technology, and support the development of skills and capacity within the renewable energy industry.20

15. Also announced as part of the Budget was $1.5 billion in targeted support for the solar energy sector - the Solar Flagships Program - an element of the Clean Energy Initiative (CEI), which is to be implemented by RET.21 With the announcement of ACRE and the CEI, solar energy projects were excluded from REDP, with the finalisation of REC's assessment of REDP solar applications suspended until ACRE was established.

16. In October 2009, the interim ACRE board22 was established by the Minister, pending the appointment of a permanent board in May 2010. The interim ACRE board assessed the REDP solar applications shortlisted by REC, using the REDP guidelines, and made funding recommendations to the Minister. This audit examines the assessment and selection processes for applications lodged under REDP (non-solar and solar), and ongoing management of funded projects.

17. On 8 July 2011, the Government announced that the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA) would be established to consolidate renewable energy support into one independent statutory authority within the Resources, Energy and Tourism portfolio. ARENA, which commenced on 1 July 2012, is to provide $1.7 billion in funding to renewable energy projects as well as managing existing programs, including REDP. ARENA replaced ACRE.

Grant administration framework and guidance

18. Australian Government grant programs involve the expenditure of public money and are subject to applicable financial management legislation. Specifically, the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (FMA Act) provides a framework for the proper management of public money and public property, which includes requirements governing the process by which decisions are made about whether public money should be spent on individual grants.

19. Following the introduction in December 2007 of interim measures to improve grants administration, the Government agreed in December 2008 to a suite of reforms, including the development of an improved framework for grants administration. These were given immediate effect through revised Finance Minister's Instructions issued in January 2009 and have now been reflected in the enhanced legislative policy framework for grants administration that came into full effect on 1 July 2009, shortly after the commencement of REDP. The new framework has a particular focus on the establishment of transparent and accountable decision-making processes for the awarding of grants, and includes new specific requirements under the financial management framework in relation to grants administration and the Commonwealth Grant Guidelines (CGGs). Officials performing grants administration duties must act in accordance with the CGGs.

Audit objective and criteria

20. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism's administration of the Renewable Energy Demonstration Program (REDP), including progress towards achieving the program's objectives.

21. The audit examined whether the department had established effective arrangements to:

- implement REDP, including governance arrangements;

- assess applications for REDP funding assistance and recommend projects to the Minister for funding approval;

- negotiate funding agreements for approved projects; and

- monitor progress towards the achievement of the REDP objective.

Overall conclusion

22. The Government has made a policy commitment to support renewable energy growth in Australia through a national renewable energy target as well as providing direct financial support for the renewable energy industry.23 The Renewable Energy Demonstration Program (REDP) was part of a 2007 election commitment that initially made available $500 million in grant funding to accelerate the development, commercialisation and deployment of renewable energy technologies in Australia. Although the Government announced in the 2008 Budget that the implementation of REDP would be delayed until the following financial year, it was decided in December 2008 that the Renewable Energy Fund, of which REDP was one component, would be brought forward for investment in the subsequent 18 months.24 The purpose of this acceleration was to stimulate the economy during the global financial crisis and to create low-pollution jobs for the future.

23. REDP was designed to provide competitive, merit-based funding for the construction of large-scale power plants to demonstrate the commercial viability of renewable energy technologies that had been proven at pilot plant scale, but had not progressed to full commercial operation. Even allowing for the expectation that these projects were to be 'shovel ready', they are a higher risk than commercially deployed technologies. This also has implications for the ability of applicants to attract and retain private sector funding (equity or debt) over the life of the project, given the requirement for grant recipients to contribute $2 for every $1 in grant funding.

24. RET received 61 eligible applications for REDP funding (36 non-solar and 25 solar). The Minister approved funding of $329.4 million for six projects, with individual grants ranging from $15.3 million to $90 million. These projects are expected to produce up to 141 megawatts of power from renewable technologies and attract a further $796.9 million in additional private sector investment. The projects are in a relatively early stage of development and, on the basis of current plans, are anticipated to be completed in 2015-16.

25. REDP was the first major program to be implemented by RET as a new department. At the time that REDP was being implemented (during late 2008 and early 2009) RET was still establishing core departmental functions. The acceleration of REDP's implementation also meant that grant applications, assessments and decisions had to be completed within a compressed timeframe, adding to the program's implementation risks.

26. While recognising the challenging environment these circumstances created, the department did not manage key aspects of the program's implementation well, departing from generally accepted practices for sound grants administration, which had only recently been reinforced by the release of the Commonwealth Grant Guidelines. In particular there were weaknesses in the following aspects of RET's administration:

- Program planning - the department did not complete an implementation plan for REDP, nor did it assess the risks facing the program until October 2009, some eight months after the launch of the program;

- Probity arrangements - departmental records did not indicate the consideration of declarations, by several Renewable Energy Committee (REC) members, of associations with entities, nor the involvement of these members in discussing individual applications for which they had declared a potential conflict. In addition, the department's probity officer did not observe the committee's assessment deliberations, nor perform the oversight tasks outlined in the probity plan; and

- Assessment of applications - the assessment process administered by the department fell short of the transparent and accountable decision-making processes for grants expected by government, with insufficient documentation retained by the department to evidence key aspects of the process.

27. RET informed the ANAO that despite these administrative issues, the processes employed by the department and REC were effective in determining the most appropriate projects to further the program's objectives. REC and subsequently the interim ACRE board25, supported by the department, completed their assessments and unanimously agreed to recommend to the Minister six projects for REDP funding. The Minister approved the six recommended projects, with a total value of $329.4 million, and deeds of agreement have been authorised and executed. At the time of the audit, the selected projects were at an early phase of implementation and, consequently, it was not possible to form an opinion on the extent to which the projects have contributed to the REDP objective - especially in terms of the commercialisation and deployment of the new technologies.

28. Since 2009, when the assessment processes for REDP were undertaken, RET has progressively strengthened its governance arrangements and guidance surrounding the administration of grant programs. This additional governance oversight and enhanced guidance better positions the department to effectively manage grant programs. There is, however, scope for the department to enhance existing materials through greater coverage of the requirements relating to the documentation of merit assessment processes. The ANAO has made one recommendation directed to this end.

Key findings by chapter

Program Planning and Oversight (Chapter 2)

Program design

29. RET consulted with industry stakeholders in designing REDP, including face-to-face meetings with selected potential applicants. Following the industry consultation process, RET refined key elements of the program design, including aligning the program's objective with the Government's policy intent by specifically incorporating the word 'new'. While the refinement of the objective restricted the eligibility of some renewable energy technologies and also changed the risk profile of the program, this change was consistent with the Government's policy position.

Program guidelines

30. The department prepared two program guidelines for REDP - one for potential applicants (the REDP Information Guide) and one for internal administration purposes (the Program Administrative Guidelines - PAG). The content of these documents was broadly aligned but the PAG was not publicly available. The department continues to issue both program administrative guidelines and separate information guides for the grant programs it administers, but now makes both publicly available. For new programs, there would be benefit in RET drafting and making publicly available program guidelines that meet the requirements of the CGGs and provide a single reference source for policy guidance, administrative procedures, appraisal criteria, monitoring requirements, evaluation strategies and standard forms to facilitate consistent and efficient grants administration.26

Implementation planning and risk management

31. The Government's decision to establish the Renewable Energy Fund in 2008 required RET to develop a detailed implementation plan, including milestones and clear measures of success. However, the department did not complete an implementation plan for REDP nor did it assess the risks facing the program until October 2009 - some eight months after the launch of the program. This increased the exposure of the department to downstream risks to the program's administration as there had not been early structured consideration given to the identification, treatment and mitigation of risks through a formal risk assessment process. The acceleration of the program and the condensed timeframe for project selection further raised the risk profile of the program and consequently the importance of sound risk management practices.

32. An implementation plan endorsed by senior management, that included resources and budgets, timelines and success factors as well as an assessment of program and implementation risks, would have provided a sound basis for the ongoing management of the program. The department's recent introduction of a project management framework, which includes the requirement for implementation and risk management plans to be developed, better positions the department to manage the implementation of its programs.

Measuring program performance

33. The department is yet to develop key performance indicators (KPIs) as a tool to allow the performance of REDP to be assessed. However, as REDP projects are in the early stages of implementation, RET has the opportunity to design and implement KPIs to assess the effectiveness of the program and the achievement of program objectives. Developing such indicators will enable the department to effectively monitor the progress of individual projects and assess whether the program is achieving its objective and whether outcomes are being delivered. RET informed the ANAO that the department is currently implementing the recommendations from ANAO Audit Report No. 5 2011-12 Development and Implementation of Key Performance Indicators to Support the Outcomes and Programs Framework.27 The department considers that the implementation of these recommendations will improve performance measures across departmental programs, and is currently drafting a set of KPIs for REDP.

Grant Assessment and Selection (Chapter 3)

Administration of the registrations of interest process

34. The REDP registration of interest process (ROI) established by RET was designed to provide feedback to applicants on the eligibility of proposed projects, assess the workload required to process applications, and to invite applicants to information workshops. RET used the information provided as part of the ROI process to identify potentially ineligible projects, including those projects that: were not of sufficient scale; had not been proven at pilot plant scale; were not employing renewable energy technologies; or were not for the generation of electricity. RET's ability to provide more specific feedback was, in part, affected by the condensed implementation timeframes resulting from the acceleration of the program and the high-level information requested from applicants.

Assessing applications for completeness and eligibility

35. Effective grant administration involves appropriate processes to ensure that applications are complete and that only eligible applications proceed to merit assessment. The process established by RET to determine the completeness of applications was limited to ensuring that attachments referenced in the application were provided. The department's assessment of completeness did not, however, include an assessment of whether all mandatory information was provided (mandatory information was not provided by 21 applicants). Notwithstanding the challenges faced by applicants in meeting the reduced application timeframe, the quality of the applications, particularly the provision of mandatory information, underpins the assessment process. The department's acceptance of incomplete applications ultimately made the subsequent merit assessment process by REC more challenging.

36. Broad eligibility criteria and the absence of clear guidance, such as defining the scale of the projects eligible for funding, made it more difficult for RET to undertake an assessment of eligibility. All 61 applications assessed as complete were deemed eligible by the department and progressed to merit assessment.

Technical and financial assessments

37. The assessment of eligible applications by the department's technical and financial assessors was designed to inform REC's merit assessment process. In general, RET appropriately managed the conflict of interest arrangements for assessors and, through documented procedures and workshops, provided assessors with a reasonable framework to undertake assessments. However, technical and financial assessors adopted different methodologies, which contributed to the inconsistent treatment of applications. In addition, the variable quality of the applications meant that the technical and financial assessments were also of variable quality - a point made by the committee. RET had made provision for the financial and technical assessments to be moderated to improve comparability, but did not pursue this option. As a result, the risk that applications were not treated equitably was increased.

38. The technical and financial assessment process would have been better informed had RET established minimum scores to demonstrate that key merit criteria were satisfied. By using total raw scores from the 17 assessments as the sole means to rank applications, there was no requirement for all criteria to be satisfied. This meant that some applications progressing to merit assessment by REC could receive a high score overall, but not meet key criteria, such as financial capacity.

Probity arrangements

39. The establishment of the REC brought expertise to the process of assessing and selecting applications and assisted the department to manage some of the program risks. Nevertheless, as some members of REC were involved in the renewable energy industry and were expected to have had involvement in the development of projects under consideration, the then Special Minister of State wrote to the Minister advising that members declare their interests in any such projects and remove themselves from the assessment. Several REC members declared an association with entities that prima facie could be considered to be a material conflict, including shareholdings, advisory roles, and professional relationships. The department advised the ANAO that the Program Manager and the REC Chair assessed the materiality of the declared associations; however, departmental records do not evidence this critical step as being undertaken.28

40. REC members informed the ANAO that the appropriate management of potential conflicts of interest was a key consideration for the committee, particularly given the total funding available under REDP, and that potential conflicts were disclosed and considered at the commencement of each meeting. The committee had agreed that members with conflicts of interest would not be excluded from committee deliberations, but were required to restrict their comments to those of a technical and financial nature. The meeting records do not, however, indicate the involvement of these members in discussing individual applications for which they had declared a potential conflict, nor the basis of the committee's decision to allow these members to rank their preferred applications.

41. The department's management of conflicts of interest was also adversely impacted by weaknesses in probity arrangements for the assessment process. Independent probity oversight was not established until after the assessment of applications had commenced. Further, the probity advisor did not observe the committee's assessment deliberations, nor perform the oversight tasks outlined in the probity plan.

42. The advice from REC members and the department to the ANAO has been that the potential conflicts of interest declared by committee members were appropriately managed. Nevertheless, the weaknesses in probity oversight and management of potential conflicts did not deliver to the Government the level of assurance expected in relation to the integrity of the assessment process for such a significant grant program.

Assessment of applications against the merit criteria

43. REC was responsible for assessing all applications against the program's merit criteria, with the committee advising the Minister that an initial out-of-session assessment was undertaken of all applications. The quality of the applications presented challenges for REC in conducting the merit assessment process. The department advised that the committee was required to exercise considerable judgement particularly in relation to the stage of development of some projects.

44. RET originally established a sound assessment process to underpin REC's merit assessment of applications. Through successive revisions to the assessment procedures, the department reduced the documentation required to support the committee's merit assessment process. RET made key decisions relating to the shortlisting of 31 of the 61 applications received (18 non-solar and 13 solar) that were not documented. The assessments by the committee members were not documented and their ranking sheets for selecting their preferred non-solar applications were not retained by the department. The preferential voting process applied by the department across individual committee member's rankings to 19 arrive at a final list of the 10 preferred non-solar and eight solar applications to be considered by the committee in-session was also not documented by the department.

45. While the minutes of REC meetings provided high-level coverage of matters considered by the committee, they did not outline the considerations taken into account when ranking eligible applications individually against the merit criteria. Summary assessments were prepared for shortlisted applications only, and these assessments did not specifically include an assessment against the merit criteria. Assessments were not prepared for those applications that were not shortlisted.29

46. These circumstances illustrate significant scope for RET to strengthen its processes for documenting the assessments of grant applications by departmental officers and advisory committees.30 That said, in terms of the selection process, the committee members advised the Minister that they had considered all applications and held a unanimous view on the projects recommended for funding in terms of the value for the expenditure of Commonwealth funds and contribution to the achievement of the Government's policy objectives.

47. RET has progressively strengthened its governance arrangements and guidance surrounding the administration of grant programs. The establishment of the Program Management Committee in 2010 and the subsequent Program Management and Delivery Committee in 2011 has provided improved oversight over development, delivery and risk management across departmental grant programs. The department's establishment of procedural rules for grants administration and risk management, the development of a comprehensive grants administration manual, and the preparation of a range of template documents to guide administrative practices better places the department to effectively manage grant programs.

Recommendations and advice to the decision-maker

48. REC provided the Minister, the decision-maker for REDP, with detailed reports recommending four non-solar and two solar projects for funding. The reports highlighted key considerations taken into account during the assessment process, including the immaturity of the Australian renewable energy sector and the shortcomings of the applications received for the program. While the reports included assessment summaries for each of the recommended projects, the summaries did not include information on the committee's assessment of the extent to which recommended projects met the merit criteria.31

49. Furthermore, the department's initial briefing accompanying REC's recommendations for non-solar projects did not comply with the requirements of the CGGs, particularly in relation to advising the Minister on the Australian Government's financial management framework and the requirements of the CGGs. The department subsequently advised the Minister of his obligations and sought approval in October 2009. The department's briefing accompanying the recommendations from the interim ACRE board for solar projects provided the Minister with appropriate information on his obligations.

Negotiation and Management of Funding Deeds (Chapter 4)

Deed negotiations

50. The department has adopted a risk-based approach to the negotiation and ongoing management of the deeds, which recognises the challenges arising from the demonstration of new renewable energy technologies at differing stages of development. The standard draft deed addressed a range of risks that could emerge under REDP by empowering the Commonwealth to claim repayment of grant funds in a range of circumstances, including abandonment of the project. Such provisions were designed to encourage applicants to commit to implementing their proposed projects in their entirety; otherwise they could be required to repay REDP grant funds in full.

51. During deed negotiations, key decisions were authorised by the Minister or the program delegate, and appropriately documented. Most deeds reflect the terms of the original recommended grant funding offer. The schedules to the deeds set out the milestones and progress payments agreed for each project, as well as the evidence that recipients must submit to the department to demonstrate the achievement of their project obligations.

52. Five of the six projects are for the construction of large-scale installations (19 to 49 megawatt). The sixth involved an integrated mini-grid project (4 megawatt) comprising wind, solar, biodiesel and storage technologies, as well as demand management features. REC noted that 'the scale of the project is small by REDP standards', but considered that 'the potential roll out to other locations around Australia was a valuable outcome'.

53. REC sought to manage the technology risks arising from some of the projects through the use of conditions precedent. This approach helped to ensure that grant recipients were in a better position to demonstrate their technology on a large scale prior to receiving REDP funding. Four grant recipients had conditions precedent imposed that involved testing part of their technology, for example completing a proof of concept project or a pilot project to demonstrate a mass manufacturing approach.

54. Two successful applicants negotiated to include the costs of pilot works in their REDP projects, despite the original grant offers for these projects requiring pilot works to be undertaken as a condition precedent separately from the REDP project. Although the overall funding to these projects did not increase during negotiations, the deeds include pilot costs as eligible expenditure. Allowing REDP demonstration projects to commence before the completion of conditions precedent relating to pilot works increases the risk profile of the projects. While recognising this, the department advised that this change in risk profile must be balanced with the greater risk that the project would not proceed, thus putting at risk the achievement of the objectives and outcomes of the program.

Deed management

55. There have been several variations to the funding deeds. Although most variations have been consistent with the REDP Information Guide, one grant recipient negotiated a variation that involves a further bringing forward of grant funding on a dollar-for-dollar basis in the early stages of the project. When considering the request for variation, RET prepared a risk assessment, which was informed by legal, technical and financial advice. The department also provided detailed briefings to the ACRE board and the Minister regarding the change in risk profile and the proposed risk mitigation strategies.

56. Grant recipients qualify for progress payments based on achieving milestones set out in the deed. The department has decided to pay milestone claims as a proportion of the original estimated costs, rather than the actual expenditure incurred by the recipient. The department plans to reconcile the total actual expenditure with estimated expenditure at the end of each financial year to ensure the overall grant funding does not exceed the authorised percentage. Given the department's decision to release milestone payments, which in some cases may exceed 33.3 per cent of actual eligible expenditure32, it is important for the department to implement a sound process to reconcile milestone payments with the amount of eligible expenditure allowed under the deeds, and to adjust payments in a timely manner.

Summary of agency response to the proposed report

57. RET's summary response to the proposed report is provided below, while the full response is provided at Appendix 1 to the report.

The Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism (RET) is committed to the effective administration of the Renewable Energy Demonstration Program (REDP). RET has successfully implemented REDP and is making good progress towards achieving the programʹs objectives.

The Auditor-General's report acknowledges the acceleration of REDP's implementation and the impact that this had on program planning, assessment and selection processes. The acceleration meant that grant applications, assessments and decision-making had to be completed within a compressed timeframe. RET accepts that some of documentation and record-keeping should have been better handled. This acceleration is the primary contributor to many of the issues identified in the Auditor-General's report.

The Auditor-General's report also acknowledges that REDP was the first major project to be implemented by RET as a new department and, at the time that REDP was being established, RET was still establishing core departmental functions. RET has considerably strengthened its governance arrangements and guidance surrounding the administration of grant programs since REDP was implemented. These improvements in departmental policies and processes address the issues in this report and RET is confident that similar issues will not occur in future program implementation.

The issues identified in this report need to be considered in balance with the positive aspects that have contributed to the effective administration of REDP. Specifically, RET would like to note that:

- The projects selected for funding under REDP were assessed and recommended by an independent and expert advisory committee, the Renewable Energy Committee (REC). RET relied heavily on the professional expertise and experience of the REC.

- The REC undertook a detailed evaluation of applications and applied considered judgement after lengthy analysis and discussion. The REC's evaluation was supported by detailed independent technical and financial written assessments.

- RET was mindful of probity requirements throughout the grant application assessment and selection process. RET maintained conflict of interest disclosures for all REC members which detailed all potential linkages and associations between REC members and applicants. No REC member had a material conflict of interest and decision-making was not compromised in any way.

- The subsequent management of the funding deeds and project activities has been professional, pro-active and outcome-focused, resulting in positive early-stage results across the project portfolio.

RET considers that the REDP funding decisions are sound, and have resulted in a balanced portfolio of meritorious projects that are fully consistent with the objectives of the Program and the principle of value for money. RET recognises however that good record keeping assists it to meet its accountability obligations and demonstrate that due process has been followed in actions and decisions. Notwithstanding the Auditor-General's findings regarding documentation and record-keeping, RET is aware of no evidence that decisions to award grants to successful recipients were incorrect, not based on merit, or that the grant application and assessment process was biased and unfairly favoured or disadvantaged any applicant.

RET accepts the recommendation of the report.

Footnotes

[1] Greenhouse gases are linked to the use of fossil fuels for energy generation, particularly coal, oil and gas. E. Edenhofer, R. Pichs-Madruga, Y.Sokona, K. Seyboth, P. Matschoss, S. Kadner, T. Zwickel, P. Eickemeier, G. Hansen, S. Schlomer, C. von Stechow (eds.), Summary for Policy Makers, In: IPCC Special Report on Renewable Energy Sources and Climate Change Mitigation, IPCC, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 2011, p. 2.

[2] Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency, National targets [Internet], Commonwealth of Australia, 2010, available from www.climatechange.gov.au/government/reduce/national-targets.aspx [accessed 4 April 2012].

[3] E. Edenhofer, et al., op. cit., p. 3. 3

[4] The combustion of biomass does produce greenhouse gas emissions, but in smaller amounts than it would in normal decomposition processes.

[5] Commonwealth of Australia, Draft Energy White Paper 2011: Strengthening the foundations for Australia's energy future, Canberra 2011, p. 209.

[6] In 2009-10, 75 per cent of Australia's electricity was produced from coal, 15 per cent from gas, and one per cent by oil. A further one per cent of Australia's electricity was produced by other fossil fuels.

[7] Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences, Energy Update 2011 [Internet], ABARES 2011, available from http://adl.brs.gov.au/data/warehouse/pe_abares99010610/EnergyUpdate_2011_REPORT.pdf [accessed 18 October 2011]. (One gigawatt hour is equal to one million kilowatt hours.)

[8] Wong, P., (then Minister for Climate Change and Water), Rudd government secures passage of 20 per cent Renewable Energy Target, media release, 19 August 2009.

[9] Based on expected electricity production of 300 000 gigawatt hours. The Senate, Economics Legislation Committee, Renewable Energy (Electricity) Amendment Bill 2009 and a related bill [Provisions], [Internet], Commonwealth of Australia, August 2009, available from www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate_Committees?url=economics_ctte/renewable_energy_09/report/c02.htm [accessed on 22 September 2011], paragraph 2.2.

[10] Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency, Renewable energy [Internet], Commonwealth of Australia, 2010, available from www.climatechange.gov.au/what-you-need-to-know/renewable-energy.aspx [accessed 6 October 2011].

[11] Australian Labor Party, Fact Sheet-Renewable Energy Fund, Canberra, circa 2007, p. 1.

[12] Also Minister for Tourism.

[13] Ferguson, M., (Minister for Resources and Energy), Budget Boosts Clean Coal and Renewable Energy, media release, 13 May 2008.

[14] Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism, Renewable Energy Demonstration Program -Information Guide, Canberra, February 2009, p. 1.

[15] The program is designed to fill the gap between post-research and commercial uptake. Consequently, REDP is targeted at project proposals that are relatively mature and are at the state of commercial demonstration. Demonstration is taken to be the final step to address remaining technology risks around integration and scale-up of the technology, once the technology has been proven at pilot plant scale.

[16] The funding available under REDP was later reduced by the Government to $300 million for non-solar projects and $100 million for solar projects.

[17] Australian Labor Party, Fact Sheet - Renewable Energy Fund, Canberra, circa 2007, p. 1.

[18] REDP is administered as an executive scheme. Executive schemes rely on executive rather than legislative power, and their key advantage is the speed with which they can be established and their flexibility. A challenge in implementing an executive scheme is ensuring that any terms and conditions are clear and enforceable. As noted by the Commonwealth Ombudsman, many of the checks and balances in programs are conveyed through legislation. Source: Commonwealth Ombudsman, Executive Schemes [Internet]. Commonwealth Ombudsman, Canberra, 2009, available from www.ombudsman.gov.au/files/investigation_2009_12.pdf [accessed 12 December 2011].

[19] Initially announced as Renewables Australia and later changed to ACRE.

[20] Ferguson, M., (Minister for Resources and Energy), $4.5 billion Clean Energy Initiative, media release, 12 May 2009.

[21] The objective of the CEI is to support the growth of clean energy and reduce emissions. The initiative included programs such as Carbon Capture and Storage Flagships, Solar Flagships, the Australian Solar Institute and the Renewable Energy Venture Capital Fund. The Government later increased funding to the CEI to $5.1 billion.

[22] REC, which was appointed by the Minister to assess REDP applications, became the interim ACRE board.

[23] Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism, Clean Energy Initiative [Internet], Commonwealth of Australia, 2011, available at www.ret.gov.au/Department/archive/cei/Pages/default.aspx [accessed 5 April 2012].

[24] The Renewable Energy Fund also comprised the Geothermal Drilling Program and the Second Generation (Gen2) Biofuels Research and Development Program.

[25] The members of REC formed the interim ACRE board, which meant the committee was responsible for the assessment of both solar and non-solar REDP applications.

[26] Department of Finance and Deregulation, Commonwealth Grant Guidelines, Canberra, July 2009, p. 22.

[27] The ANAO recommended that entities: establish requirements to review program objectives to ensure they are clearly defined; develop key performance indicators with appropriate emphasis on quantitative and measurable indicators; and assess the extent that costing information is currently used to identify program support costs and allocate these costs to applicable programs.

[28] The REDP Renewable Energy Committee Handbook and assessment procedures required a decision on materiality or immateriality to be made prior to grant applications being provided to REC members.

[29] The CGGs state that 'In the context of grant administration, probity and transparency are achieved by ensuring: that decisions relating to granting activity are impartial, appropriately documented and publicly defensible.' p. 27.

[30] The CGGs state that 'Accountability involves agencies and decision-makers being able to demonstrate and justify the use of public resources to government, the Parliament and the community. This necessarily involves keeping appropriate records... [and] involves providing reasons for all decisions that are taken and the provision of information to government, the Parliament and the community.' p. 27.

[31] The REC summary assessments provided: a brief description of the proposal; the project participants; project details, such as technology, site, grant amount sought, project cost and megawatt (MW) scale; and a listing of strengths and weaknesses.

[32] In some cases, this ratio of project expenditure to grant funding has been altered through the deed negotiation or variation processes, with the grant recipient agreeing to contribute a greater proportion of funding to the project.