Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Scheme

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency’s implementation and administration of the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Scheme.

Summary

Introduction

1. Climate change caused by the emission of greenhouse gases has been recognised as a global challenge with the potential to affect ecosystems, water resources, food production, human health, infrastructure and energy systems in all countries.1 Within Australia, successive Australian Governments have introduced a range of initiatives to address the challenges posed by climate change. State and territory governments have also introduced programs and initiatives designed to reduce emissions or assist communities to adapt to climate change. In 2008, there were some 550 climate change related measures identified across jurisdictions in Australia.2

2. The reporting of greenhouse gas emissions is a central component of most greenhouse and energy programs as it allows entities and governments to monitor the achievement of their greenhouse and energy objectives. In response to the growing awareness of the potential impacts of greenhouse gas emissions on Australia’s climate, governments have increasingly sought to engage industry in initiatives to promote greenhouse gas reductions, encourage low emission technologies and improve energy efficiency.

3. In April 2007, the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) agreed to establish a mandatory national greenhouse gas emissions and energy reporting system to replace a range of voluntary industry surveys and programs with greenhouse gas or energy measurement requirements.

National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Scheme

4. The National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Scheme (NGERS) was established under the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Act 2007 (the NGER Act), which was passed by the Parliament in September 2007. NGERS was designed to introduce a single national reporting framework for constitutional corporations that have significant greenhouse gas emissions from energy consumption and energy production.3 The five objectives of the NGER Act are to:

- underpin the introduction of a proposed emissions trading scheme in the future;

- inform government policy formulation and the Australian public;

- meet Australia’s international reporting obligations;

- assist Commonwealth, state and territory government programs and activities; and

- avoid the duplication of similar reporting requirements in the states and territories.

5. The NGER Scheme commenced from 1 July 2008 and is administered by the Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency (DCCEE). The legal framework under which NGERS is delivered comprises primary legislation, subordinate legislation, guidelines and other supporting material.

6. Under NGERS, registration and reporting is mandatory for constitutional corporations with energy production, energy use or greenhouse gas emissions that meet specific thresholds. The thresholds for facilities4 controlled by corporations required to report under NGERS is 25 000 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2-e) emissions or 100 terajoules (TJ) of electricity.5 For corporations as a whole, the thresholds for 2010–11 are 50 000 tonnes of CO2-e or 200 TJ of electricity.

7. Registered corporations must report to DCCEE using the Online System for Comprehensive Activity Reporting (OSCAR), a web-based data tool that has been developed for industry to record energy and emissions data. It was designed to standardise reporting from corporations, and enable the automatic calculation of greenhouse gas emissions, based on energy and emissions data. In 2009–10, NGERS publicly reported greenhouse gas emissions totalling some 225 million tonnes of CO2-e.6

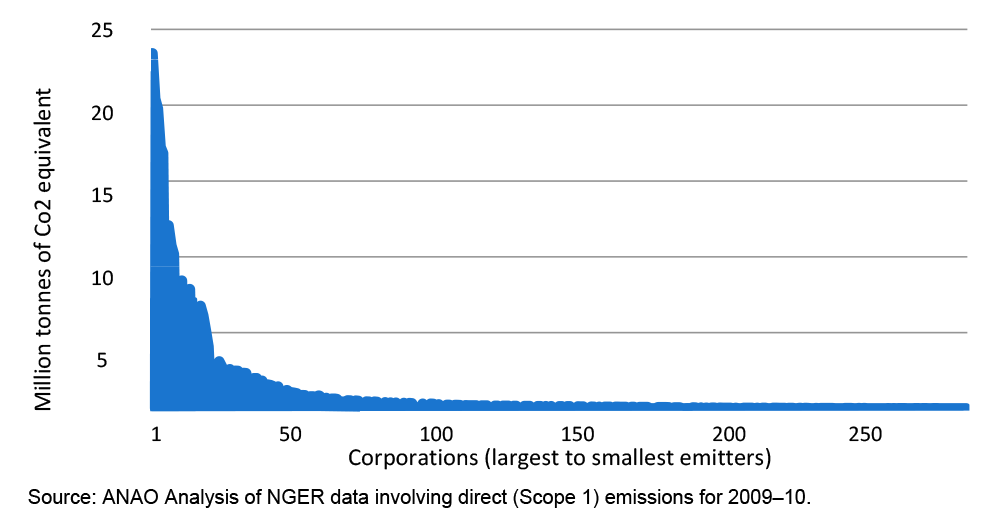

8. As at March 2011, 775 corporations were registered with DCCEE and reported their emissions and energy use data through OSCAR.7 Of these reporting corporations, those with the highest emissions (299) had their data published in 2011 for the 2009–10 reporting year.8 Figure S.1 shows the level of direct emissions that these corporations emit annually.9 The 100 corporations with the largest greenhouse gas emissions from direct combustion account for over 90 per cent of the total direct emissions reported. These are termed Scope 1 emissions.10

Figure S.1: Published reporters and direct emissions levels for 2009–10

Source: ANAO Analysis of NGER data involving direct (Scope 1) emissions for 2009–10.

Carbon Pricing Mechanism

9. In February 2011, the Government proposed that a carbon pricing mechanism would be introduced from July 2012 with a cap-and-trade emissions trading scheme following within three to five years. This decision effectively re-established the link to one of the primary objectives of the NGER Act—to underpin the introduction of a proposed emissions trading scheme. On 13 September 2011, the Government introduced a legislative package that would enable the implementation of the policy set out in the Government’s Climate Change Plan, Securing a Clean Energy Future.11 The Clean Energy Legislation was passed by the Parliament on 8 November 2011. With the passage of the legislation, regulatory responsibility for NGERS is expected to transfer on 2 April 2012 to a separate authority—the Clean Energy Regulator.

10. The Government has indicated that the carbon pricing mechanism will apply to approximately 500 of the largest emitters of CO2-e in Australia. In general, the NGERS threshold of 25 000 tonnes of CO2-e will determine whether a facility will be covered by the carbon pricing mechanism. Carbon pollution from the following sources will be covered by a carbon price: stationary energy; waste; rail; domestic aviation and shipping; industrial processes; and fugitive emissions. Over half of Australia’s emissions are intended to be directly covered by the carbon pricing mechanism.12

Audit objective and criteria

11. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of DCCEE’s implementation and administration of NGERS.

12. The audit examined whether DCCEE had effectively implemented the scheme; managed the integrity, security and quality of scheme data; monitored industry compliance with the provisions of the NGER Act; and streamlined reporting arrangements in line with the agreement by the Australian, state and territory governments.

13. The ANAO conducted a survey of registered corporations to obtain qualitative client data on the efficiency and effectiveness of the administration of NGERS.13 In addition, information technology (IT) testing was undertaken as part of the audit to assess the security of the NGERS online reporting system, OSCAR. The ANAO did not validate the data provided by registered corporations.

Overall conclusion

14. The passing of the NGER Act in September 2007 created a new regulatory regime for Australia, with 775 constitutional corporations required to self assess and report their greenhouse gas emissions, energy use and production. This assessment and reporting was a critical prerequisite to underpin the proposed emissions trading scheme. It was also fundamental to the transparent reporting of Australia’s national and global commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and energy use. Accurate and complete datasets are also integral to the integrity of Australia’s National Greenhouse Gas Inventory14 and other international reporting obligations under the Framework Convention on Climate Change.

15. The establishment of NGERS was a substantial and complex undertaking for DCCEE given the scale and broad coverage of the legislation across the Australian economy. The changing operating environment, particularly in relation to the proposed introduction of an emissions trading scheme in 2015 and the more recent carbon pricing mechanism, presented additional challenges for DCCEE that have impacted on the department’s implementation of NGERS. Nevertheless, DCCEE has established a workable greenhouse gas and energy reporting scheme that provides a more accurate measurement of greenhouse gas emissions and energy use within Australia when compared to the voluntary industry surveys and programs that were previously in place. DCCEE has established a positive relationship with the majority of registered corporations. In addition, over 50 per cent of corporations have indicated in their response to the ANAO’s survey that tangible benefits have been obtained from measuring their greenhouse gases and energy use.

16. Notwithstanding these positive findings and progress to date, key aspects of DCCEE’s administration require strengthening to improve the operation of NGERS. These include enhancing the integrity of reported greenhouse gas emission and energy use data; better managing compliance with the regulatory requirements; and streamlining reporting obligations as intended by COAG.

Data integrity

17. The quality and accuracy of reports submitted by corporations is critical for the overall integrity of the NGERS dataset. As the scheme relies on the self assessment and reporting of greenhouse gas emissions and energy data by corporations, a sound quality assurance process supported by a risk-based compliance program are key elements for effective administration. Currently, DCCEE does not verify15 the data reported by corporations. Rather the department’s quality assurance relies on a desk top review of submitted data.16 It is intended that verification will be a major component of DCCEE’s compliance and audit program in 2012. In 2009–10, DCCEE identified that nearly three quarters of submitted reports contained errors, with 17 per cent of reports containing significant errors. The importance of accurate greenhouse gas emission and energy use data will increase significantly with the introduction of a carbon price in 2012. DCCEE has taken steps to improve data quality, including initiating a report re-submission process and the introduction of the recent Data Quality Improvement Strategy, to better position the department to monitor the integrity of data provided by registered corporations.

18. The integrity of the data collected under NGERS also relies on the functionality and security of the IT system (OSCAR) used by entities with NGERS obligations, to report and store data. The IT security testing undertaken as part of this audit, identified significant security vulnerabilities within the system that increased the risk of an unauthorised person gaining access to, and threatening the integrity of NGERS data. The subsequent report made forty specific recommendations to improve security. Eight of these recommendations were classified as high priority. The results of this security testing highlight the importance of managing risks through sound change and release management controls for the update and enhancement of IT systems. The ANAO’s recommendations are being progressed by DCCEE.

Compliance management

19. As the regulator, DCCEE is responsible for ensuring that regulated entities have met legislative requirements. DCCEE has put in place a number of strategies designed to educate and train representatives from corporations and to encourage compliance with NGERS registration and reporting requirements. However, the implementation of the NGERS compliance and audit program has been slower than planned. Implementation was constrained by the redistribution of resources following the deferral of the emissions trading scheme, and the lower priority afforded to this work within the first three years of NGERS. Consequently, a systematic, risk-based audit and compliance program is still in the process of being implemented. There remains substantial work to be undertaken to establish a program that is capable of providing an appropriate level of assurance that corporations are complying with their obligations. The cost of compliance for corporations is also significantly higher than the estimates in the NGERS regulatory impact statement. Striking the appropriate balance between meeting compliance obligations and the associated cost for regulated entities will be an important consideration for DCCEE in implementing the NGERS compliance and audit program.

Streamlined reporting

20. NGERS was intended to reduce the duplication of reporting requirements across related programs and create a single national reporting framework. This legislated objective was reinforced by a Protocol agreed by Australian, state and territory governments in July 2009. There was initial progress under the Protocol to streamline reporting obligations, with DCCEE ceasing a number of national programs as well as voluntary company surveys. Despite this initial streamlining activity, progress effectively stalled from April 2010 when the Government deferred the introduction of an emissions trading scheme. As a consequence, multiple reporting obligations remain.17 Reporting obligations and the associated inefficient use of resources were frequently cited as a significant problem by respondents to the ANAO survey and during discussions with stakeholders. Of the corporations surveyed, 63 out of 108 respondents (58.3 per cent) stated there had been no reduction in reporting requirements. If the objectives of the agreed Protocol are to be realised, DCCEE will need to give priority to working with jurisdictions to streamline current reporting requirements.

21. The ANAO has made three recommendations designed to: better target departmental compliance efforts; improve data sharing with Australian Government and authorised state or territory agencies; and advance efforts to further streamline greenhouse gas emission and energy use reporting requirements.

Key findings by chapter

Implementation planning and delivery (Chapter 2)

Establishing NGERS

22. DCCEE undertook considerable preparation and design work in 2007–08, during the early stages of NGERS. While the department’s focus was appropriately directed at those elements of the scheme necessary to facilitate registration and reporting by corporations, other key objectives of NGERS were not sufficiently progressed during this time, such as the compliance and audit program.

23. In parallel with DCCEE’s establishment of NGERS, the department directed considerable resources into the design of the proposed emissions trading scheme, including the establishment of a new authority with responsibility for NGERS as part of an integrated regulatory framework. When the introduction of the proposed emissions trading scheme was deferred by the Government, the subsequent reduction in resources, the re-deployment of staff, and the re-organisation of the department contributed, in part, to delays in progressing key elements of NGERS, such as the streamlining of greenhouse gas emissions and energy use reporting.

Support and guidance for corporations

24. As the legislative framework underpinning the NGER Scheme is principles-based, effective guidance and support is necessary to inform corporations of their obligations under the scheme. One hundred and thirty one corporations out of 187 respondents (70 per cent) to the ANAO’s survey, rated the support and guidance provided by the department as ‘good’ to ‘very good’. The remaining 30 per cent of survey respondents have provided useful insights into areas for further improvement, such as: clear lead times for the provision of updated guidance; improvements to the dissemination of guidance materials; and targeting guidance materials at those areas of greatest concern to registered corporations.

Governance arrangements

25. The ongoing administration of NGERS has occurred within a changing operating environment, which has presented challenges in ‘bedding down’ key elements of an effective governance framework. These elements include: the management of identified risks to program delivery, administrative processes for handling complaints and comprehensive performance reporting to Parliament. In response to these issues, DCCEE has implemented revised governance arrangements and systems, including establishing an Issues Coordination Committee (ICC) in mid-2011 to better coordinate matters such as the handling of major complaints or other priority business issues.18

26. DCCEE has developed and implemented a comprehensive business plan to guide the department’s administration of NGERS, which incorporates performance information aligned to the five NGERS objectives. A greater focus on measuring and publicly reporting progress against the achievement of all NGERS objectives will provide stakeholders with greater insights into program performance over time and enhance accountability. A high level risk management plan and risk register have also been developed, although implementation is at an early stage and will require a concerted effort to achieve the timely treatment of identified risks.

Data collection and management (Chapter 3)

Collecting the data prior to submission

27. Registered corporations self assess their emissions data based on methodologies and guidance provided by DCCEE. OSCAR automatically calculates greenhouse gas emissions based on the corporation’s energy and emissions data. Corporations are responsible for: collecting greenhouse gas emissions and energy data; assessing data accuracy; maintaining appropriate records of the data and any assumptions or estimates; and submitting their report through OSCAR within four months from the end of each financial year.

28. The process used by most corporations for collecting NGERS data prior to lodgement through OSCAR is through manual spreadsheets. In response to the ANAO’s survey, 128 corporations out of 180 respondents (71.1 per cent) reported that they relied exclusively or primarily on manual spreadsheets. Only five corporations (2.8 per cent) reported that they had fully automated systems. Spreadsheets are relatively low cost and may be appropriate for the majority of corporations with simple, indirect reporting requirements. However, they are prone to error and less than half of respondents to the ANAO survey indicated that they used independent assurance.19

Maintaining adequate records and verifying the data

29. In accordance with the NGER Measurement Determination, registered corporations are required to keep records detailing their greenhouse and energy-related activities, including facilities where appropriate.20 The ANAO’s survey results indicated that 116 corporations out of 181 (64.1 per cent) considered that they met these record keeping requirements. Some 65 corporations (35.9 per cent) indicated that they were experiencing challenges in this area, including four that were not sure or did not know whether records were available to verify their level of greenhouse gas emissions or energy use. Currently, the department does not verify the reported data. Rather, in the absence of an audit and compliance program, the department relies on a desk top review of submitted data to test matters, such as obvious data or calculation errors, consistency of data received against other publicly available information; and consistency across the two years of NGERS reports.

30. The most common explanations for incomplete records to support verification of reported data related to difficulties in: recording incidental emissions of greenhouse gases from minor sources; obtaining supporting records from contractors or other parties; and obtaining data and records in complex corporate relationships, such as following a merger or where there are hundreds of geographically separate sites and facilities. These findings were largely supported by the department’s 2011 pilot audit program. DCCEE has recognised the tensions between the requirements of the NGER Measurement Determination (particularly in regard to data ‘completeness’) and the practical constraints facing corporations in areas such as measuring incidental emissions and petroleum based oils and greases (PBOG’s) in particular.21 There has been some flexibility introduced to enable estimates of PBOG’s to be rolled over from year to year.

31. The development of appropriate materiality threshold/s for reporting purposes would help to maintain a focus on the highest priority areas relevant to the objectives of the legislation and, at the same time, reduce compliance costs for the department and corporations. The potential effort and cost required by DCCEE to review and verify incidental emissions through its proposed audit program will be considerable. Equally, there is a compliance burden on reporting corporations with one corporation reporting that incidental greenhouse gases may only cover 0.1 per cent of the corporation’s emissions. There would be merit in DCCEE giving further consideration to the balance between the benefits gained from the current incidental reporting requirements compared to the compliance costs involved for the department and corporations. There is potential for DCCEE to significantly reduce the regulatory burden on corporations without materially impacting on the precision or completeness of NGERS data.

Online reporting system functionality

32. The establishment of OSCAR was intended to save business time and effort by reducing the burden of multiple reporting requirements and enable the sharing of common data across different government programs. In response to the ANAO’s survey, 90 corporations out of 186 respondents (48.4 per cent) rated the system as ‘average,’ 59 registered corporations (31.7 per cent) rated the system ‘good’ to ‘very good’ with 37 (19.9 per cent) rating the system from ‘poor’ to ‘very poor’. This variation is indicative of the considerable differences in the range and volume of data management issues across registered corporations. While OSCAR is broadly fit-for-purpose for smaller corporations with less complex reporting requirements, corporations with large, direct emissions or complex joint ventures indicated significant problems regarding the use of OSCAR. The absence of an upload facility, the level of duplication of data requirements across programs, the potential for errors in manual data entry and the slowness of the system, are all problems that have constrained the effectiveness of OSCAR.

33. DCCEE has informed the ANAO that an interim upgrade of OSCAR is expected to be in place for the 2011–12 reporting period. The department also advised that a project has been initiated to develop a more robust emissions reporting system in the longer term for NGERS and the carbon pricing mechanism.

NGERS data security

34. An ANAO IT security audit of OSCAR, undertaken as part of the broader audit, identified significant security vulnerabilities. The subsequent report made forty specific recommendations to improve system security. Eight of these recommendations were classified as high priority. Particular security concerns related to matters such as: formalising the security patch management process; hardening the protection of the servers running OSCAR applications; limiting administrator access and privileges within the OSCAR environment; and ensuring that all parties with access to OSCAR, including service providers external to DCCEE, are implementing and adhering to security requirements. These vulnerabilities increased the risk that an unauthorised person could gain access to NGERS data. The audit highlights the importance of managing risks through sound change control and release protocols for the update or enhancement of IT systems. The ANAO’s recommendations are being progressed by DCCEE.

Data quality and verification by DCCEE

35. While DCCEE conducts a data quality assurance process which tests reported data for errors, as previously noted, the department does not verify the data reported by corporations. It is expected that audits undertaken as part of the compliance and audit program will examine energy and greenhouse data. The department’s quality assurance process has identified that the quality of data reported to DCCEE over the first two years of NGERS has been affected by errors and gaps. In the first year of NGERS (2008–09), more than half of all reports to the department contained minor errors and around one per cent had significant errors. In the second year of NGERS reporting (2009–10), the department implemented a comprehensive quality assurance process for the reports from 545 controlling corporations.22

36. Of the 545 reports analysed, 72 per cent contained errors with 17 per cent including significant errors.23 The most common errors related to: gaps in own-use electricity; missing or incorrect sources; errors in facility aggregates; problems with energy production figures; and omitted corporate entities and facilities. Nine corporations were also found to have submitted incomplete reports because of ‘bugs’ in OSCAR. These results highlight the critical role DCCEE’s quality control process plays in enhancing the quality of outputs from NGERS reporting. To improve the quality of NGERS data, the department has instituted a resubmission process to address errors in submitted reports.24 DCCEE is also introducing a Data Quality Improvement Strategy to strengthen the integrity of the data provided by registered corporations. Introducing an appropriate materiality threshold for reporting purposes would also assist in this regard.

Managing compliance (Chapter 4)

Delays in implementation and late reporting

37. Implementation of an NGERS compliance and audit approach within DCCEE has been slower than planned, primarily because of limited resources and the lower priority afforded to this work within the first three years of operation. These delays have constrained the capacity of DCCEE to identify compliance issues within corporations and address these early in the implementation of NGERS. While a pilot audit program has recently been conducted by DCCEE and a full program has commenced, delayed implementation of the full audit program has compromised the assurance that the department has obtained regarding corporations’ compliance with key obligations under the NGER Act. This is particularly the case with regard to the adequacy of recordkeeping and the integrity of data underpinning the reports provided to the department by registered corporations.

38. DCCEE’s adoption of an education and guidance focus to compliance activity over the initial period of implementation has encouraged corporations to meet NGERS registration and reporting requirements. However, late reporting remains a challenge with 23 per cent of registered corporations submitting late reports from 2009–10. A total of 43 corporations had not reported at the beginning of June 2011—seven months after the statutory deadline.

Indicative costs of compliance

39. In general, registered corporations surveyed by the ANAO indicated that they were not in a position to accurately determine costs directly attributable to complying with their obligations under NGERS. Only eight corporations reported that they had firm data to support their response. A sample of corporations did, however, provide indicative estimates of their capital (22 corporations) and recurrent costs (68 corporations). These survey results indicate that registered corporations incurred capital costs ranging from $5000 to $3 million, with recurrent costs ranging from $1500 to $1.5 million. These reported estimates significantly exceed the original cost estimate of $10 000 for annual entity costs at the time the legislation was passed by the Parliament. Even taking into account that the cost data may relate to multiple reporting purposes, the reported costs do not support the ‘cost-neutral’ position assumed for larger corporations. Costs are also higher than the costs reported under similar international schemes.

Tangible benefits from measuring and reporting emissions

40. The ANAO sought information from registered corporations on whether measuring and reporting greenhouse gas emissions and energy use had resulted in tangible benefits. Ninety-three corporations out of 176 respondents (53 per cent) indicated that measuring and reporting had delivered benefits. Interviews with registered corporations also highlighted a number of benefits including, improved cost controls and reduced outlays for energy use—$2 million per annum for one registered corporation. Notwithstanding these positive outcomes, 83 corporations (47 per cent) indicated no tangible benefit from measuring and reporting energy use and greenhouse gas emissions, and expressed concerns regarding the significant regulatory burden they faced.

Streamlining greenhouse and energy reporting (Chapter 5)

Streamlining progress

41. Work to streamline corporate greenhouse gas and energy reporting across jurisdictions began in 2005 following recommendations in the then Australian Government’s 2004 Energy White Paper. In October 2006, a draft Regulation Impact Statement (RIS) was released for consultation. The statement identified fifteen Australian Government, state and territory programs at that time that had greenhouse and/or energy reporting requirements. COAG agreed that: ‘a single streamlined system that imposes the least cost and red tape burden is the preferable course of action’. A Streamlining Protocol was agreed by Australian, state and territory governments in July 2009. Implementation of the Protocol was agreed through COAG.

42. At the national level, the Australian Government has discontinued a Fuel and Electricity Survey of industry and amended the Energy Efficiency Opportunities25 (EEO) requirements to allow entities to align EEO and NGER Act reporting. This was completed before the Protocol was finalised in July 2009. DCCEE has also ceased a number of national programs as well as voluntary company surveys previously conducted to support the National Greenhouse Gas Inventory.26 From 2009, DCCEE developed technical solutions to support streamlining of greenhouse and energy reporting. Initial actions included the refinement of OSCAR to align it to both the NGER legislation and the National Greenhouse and Energy Streamlining Protocol requirements for Australian Government, state and territory stakeholders. However, there has been limited progress across other jurisdictions to reduce the multiple reporting requirements for corporations.

Weaknesses in the National Disclosure Tool

43. An electronic disclosure tool, the NGERS Disclosure Tool (NDT), was developed in 2009 to enable DCCEE to disclose greenhouse gas emissions and energy use data to specified persons and bodies within the Australian Government as well as state and territory jurisdictions.27 However, the NDT was not ‘rolled out’ to users until May 2010 and there were significant technical problems with the tool for the 12 months following roll out. Effectively, the NDT was not operational at this time and data access by users was restricted. The lack of full functionality of the NDT has resulted in the continued duplication of reporting requirements and potentially higher reporting costs for industry. Delays in establishing a functional disclosure tool have also hampered the capacity of specified agencies to benefit from the detailed data available under NGERS. DCCEE established a Data Users Group in March 2011 to resolve data sharing issues.

Intergovernmental cooperation on information sharing

44. Since the Streamlining Protocol was agreed, Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) to safeguard the confidentiality of NGERS data have been agreed between DCCEE and other Australian Government agencies, such as the ABS, DRET and ABARE. Similar MOUs were agreed progressively with Queensland, the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) governments in 2011. MOUs are yet to be agreed with the remaining state and territory governments—over two years after the Protocol was agreed by First Ministers in July 2009. Ongoing tensions exist in relation to data sharing arrangements, such as: potential conflicts between Australian Government and state legislation; controls over the release of sensitive, commercial-in-confidence information; warranties over the quality of the data; and the costs involved for state agencies in meeting Australian Government confidentiality and disclosure standards. Notwithstanding these tensions, DCCEE has advised that negotiations with individual jurisdictions are continuing, with outstanding issues being progressively resolved with a view to finalising all MOUs during 2012.

Views of registered corporations

45. The ANAO sought information from registered corporations regarding the progress that has been made against the objective of the Streamlining Protocol. In response to the ANAO’s survey, corporations reported that they were providing data for up to ten additional Australian Government, state and territory government, or international bodies.28 Sixty-three corporations out of 108 respondents (58.3 per cent) considered that there had been no progress, while 32 (29.6 per cent) considered that there had been progress to some extent.29 Only seven corporations (6.5 per cent) considered that there had been a reasonable or high degree of progress.

Summary of agency response

46. DCCEE responded to the report as follows, with the full response included at Appendix 2:

The Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency (the Department) accepts the three recommendations of the 2011 ANAO audit report on the Administration of the Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Scheme (NGERS).

The NGERS provides a rich and detailed data set across energy production and consumption and greenhouse gas emissions. This data set is currently meeting the majority of energy and greenhouse data needs of relevant Commonwealth agencies in advising government on policy, informing the community, and meeting international reporting obligations. The scope and granularity of NGERS data is being examined as a model by other countries. Over time, we expect the value of the data to increase, as each year of reporting establishes a longer time series and as the Department pursues continuous improvement to data quality.

The audit report acknowledges the dynamic policy and resourcing context the Department faced in implementing NGERS, the complexities of the reporting scheme, and the efforts of the Department in seeking the agreement of states and territories to use information reported under NGERS for state greenhouse gas or energy program purposes.

Regarding recommendations 2 and 3, the Department will continue to pursue achievement of the streamlining objectives, in alignment with appropriate initiatives under the Council of Australian Governments. In this regard the Department will also foster opportunities to engage with jurisdictions and stakeholders.

Following the IT findings from the 2011 ANAO audit, the Department has made significant improvements to the security of the IT system. The Department completed actions to rectify the very high and high risks identified and has made significant infrastructure improvements in light of the audit report.

As part of the Clean Energy Legislative Package, amendments to the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Act 2007 build on and strengthen a comprehensive national reporting framework to support delivery of the carbon price mechanism. With the passing of the legislation by the Senate in November 2011, the Department is firmly focused on implementation activities. A Carbon Price Implementation Program is now well underway to undertake the action necessary for the implementation of the carbon price mechanism to proceed smoothly.

Footnotes

[1] International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions, Working Group on Environmental Auditing, Coordinated International Audit on Climate Change; Key Implications for Governments and their Auditors, November 2010, p.9.

[2] ANAO Audit Report No 27, 2009–10, Coordination and Reporting of Australia’s Climate Change Measures, p.19.

[3] A constitutional corporation is defined under paragraph 51(xx) of the Australian Constitution.

[4] Examples of facilities include: retail outlets; primary production and manufacturing plants; construction sites; air, rail road and water transport; and electricity, gas or water supply.

[5] One terajoule is equal to 1012 joules.

[6] Over the year to the June quarter of 2011, Australia’s National Greenhouse Gas Inventory was an estimated 546 Mt CO2-e (million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent). DCCEE, Quarterly Update of Australia’s National Greenhouse Gas Inventory, Canberra, June 2011, p.6. Total scope 1 emissions are 344 Mt of CO2-e. This includes those reports below the public reporting threshold.

[7] These figures are updated annually inline with the reporting cycle.

[8] This data is available on DCCEE’s website.

[9] Direct emissions (Scope 1) are derived from the combustion of coal, oil or other energy sources.

[10] Scope 2 emissions are indirect greenhouse gas emissions derived from the purchase of energy, such as electricity produced from burning coal, oil or natural gas.

[11] DCCEE, Securing a Clean Energy Future—The Australian Government’s Climate Change Plan, Canberra, 2011.

[12] DCCEE op. cit., p.27.

[13] Not all corporations responded to every ANAO question. Consequently, the percentages stated in this report are based on varying totals based on the particular question asked.

[14] The National Greenhouse Gas Inventory provides estimates of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions based on the latest available data and the accounting rules that apply for the Kyoto Protocol within the Framework Convention on Climate Change.

[15] Data verification within this context is defined as testing and providing assurance that reported data is supported by accurate source material and records from which it is derived.

[16] This process tested: obvious data or calculation errors; the consistency of data received against other publicly available information such as the electricity market data; and consistency across the two years of NGERS reports.

[17] Corporations surveyed by the ANAO cited up to ten reporting obligations for different state, territory and/or Australian Government programs as well as voluntary international commitments such as the Global Reporting Initiative. Apart from NGERS, corporations cited reporting obligations under initiatives such as the Energy Efficiency Opportunities Program, Renewable Energy Certificates and the National Pollutant Inventory (Australian Government), the Environment and Resource Efficiency Plans (Victoria), New South Wales (NSW) Greenhouse Gas Abatement Scheme, Energy Savings Action Plan, NSW Greenhouse Abatement Certificates, Operating Licence reporting (NSW and other states) and QFLEET (Queensland).

[18] The ICC was established in mid-2011 to formally identify issues (such as realised risks), nominate the relevant section or team to resolve the issue and put a timeframe on the resolution of each issue.

[19] The ANAO survey found that 85 corporations (47.0 per cent) used some form of verification prior to submission.

[20] The NGER (Measurement) Determination provides for the Minister to determine methods, or criteria for methods, for the measurement of: a) greenhouse gas emissions; b) production of energy; and c) the consumption of energy.

[21] DCCEE, (August 2010) Review of the NGER (Measurement) Determination, Discussion Paper, p.47.

[22] This process tested: obvious data or calculation errors; the consistency of data received against other publicly available information; and consistency across the two years of NGERS reports.

[23] DCCEE has defined a significant error as one where the figure used is incorrect by greater than 40 per cent of the NGER facility threshold or that impacts on the data by 10 kilo tones of CO2-e or more of total greenhouse gas emissions or 40 TJ or more of energy consumption or production.

[24] In 2008–09 and 2009–10, there were 47 and 23 corporations respectively that resubmitted their reports. About one-third of these resubmissions were instigated by discussions with the department following analysis of corporations’ reports. This process has improved the quality of aggregate data available under NGERS.

[25] The Energy Efficiency Opportunities Program is managed by the Department of Resources, Energy and Tourism. The Program encourages large energy-consuming businesses to improve their energy efficiency. It does this by requiring businesses to identify, evaluate and report publicly on cost effective energy savings opportunities.

[26] Australia’s National Greenhouse Gas Inventory is required under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. The Inventory provides a national baseline of aggregate emission levels and allows emission levels to be tracked over time as well as Australia’s progress towards emission targets.

[27] Australian Government agencies include the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Department of Resources Energy and Tourism (DRET) and the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics (ABARE).

[28] Corporations with global operations commented that they have provided reports to programs in the USA, Canada and the United Kingdom, including the Carbon Disclosure Project and the Dow Jones Sustainability Index.

[29] Six corporations (5.6 per cent) were not sure or did not know if there has been a reduction in the level of duplication in reporting.