Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of the Health and Hospitals Fund

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of DoHA’s administration in supporting the creation and development of health infrastructure from the HHF, including DoHA’s support for the Health Minister and the HHF Advisory Board.

Summary

Introduction

1. The Australian Government announced the establishment of three new funds in the 2008–09 Budget to support capital investment in infrastructure, education and health. The three new funds, with total funding of $22.4 billion, were: the Building Australia Fund; the Education Investment Fund; and the Health and Hospitals Fund (HHF)1, all of which were given effect through the Nation-building Funds Act 2008 (the Act), commencing on 1 January 2009. The Act, together with the Nation-building Funds (Consequential Amendments) Act 2008, provides the legislative basis for these funds.

2. The HHF objectives, whilst not replacing state and territory effort, are to:

- invest in major infrastructure programs that will make significant progress towards achieving the Commonwealth’s health reform targets; and

- make strategic investments in the health system that will underpin major improvements in efficiency, access or outcomes of health care.

3. The 2008–09 Budget set the broad direction for the HHF, namely to fund capital investment in health facilities, including renewal and refurbishment of hospitals, medical technology equipment and major medical research facilities and projects.

4. Under the Act, the HHF is comprised of two interrelated parts: the HHF Special Account and investments of the HHF. The Department of Finance and Deregulation (Finance) has responsibility for the administration of the HHF Special Account, with the Act committing the Australian Government to crediting $5 billion to the HHF Special Account by 30 June 2009.2 The Future Fund’s Board of Guardians3, a statutory body within the Finance portfolio, is responsible for investing the financial assets of the HHF.

5. All health infrastructure proposals are to be assessed by an Advisory Board established under the Act and appointed by the Minister for Health and Ageing (Health Minister).4 The Health Minister is also responsible for formulating the evaluation criteria to be applied by the Advisory Board in its assessment of applications for funding from the HHF. The evaluation criteria, which are made subject to a legislative instrument5, are based on the following principles:

- Principle 1: projects should address national infrastructure priorities;

- Principle 2: projects should demonstrate high levels of benefits and effective use of resources;

- Principle 3: projects should efficiently address infrastructure needs; and

- Principle 4: projects should demonstrate that they achieve established standards in implementation and management.

6. The process for projects to receive HHF funding is complex, incorporating a number of administrative and legislatively determined steps:

- the Department of Health and Ageing (DoHA) undertakes a preliminary analysis to determine the extent to which each funding application addresses each evaluation criterion;

- the HHF Advisory Board assesses the eligibility of infrastructure project proposals against the evaluation criteria;

- following receipt of the Advisory Board’s assessments, the Health Minister puts forward projects for consideration by government in the Budget context;

- project proposals are scrutinised in the Budget context and may receive policy approval;

- as required by the Act, the Health Minister writes to the Minister for Finance and Deregulation (Finance Minister) recommending authorisation to enable future payments to be made for those projects with policy approval;

- following receipt of the Finance Minister’s authorisation, negotiations are initiated by DoHA on the details of funding agreements for projects, and the required financial management approvals are given by DoHA to enable financial commitments to be entered into through funding agreements;

- the Health Minister (or delegate) enters into the funding agreement with the entity responsible for the project to be funded;

- when a project payment milestone is reached, DoHA writes to the Finance Minister (or delegate) seeking payment. If agreed, the funds are made available by the Future Fund Management Agency into the HHF Special Account, and Finance transfers the money from that special account to the HHF Health Portfolio Special Account; and

- DoHA makes the payment to the relevant entity or to the COAG Reform Fund if the payment is for a state or territory delivery agency.

7. DoHA is responsible for administering the HHF. This includes: providing advice to the Health Minister; providing secretariat support to the HHF Advisory Board; contributing to the assessment process through its preliminary analysis; negotiating HHF funding agreements and administering their implementation.

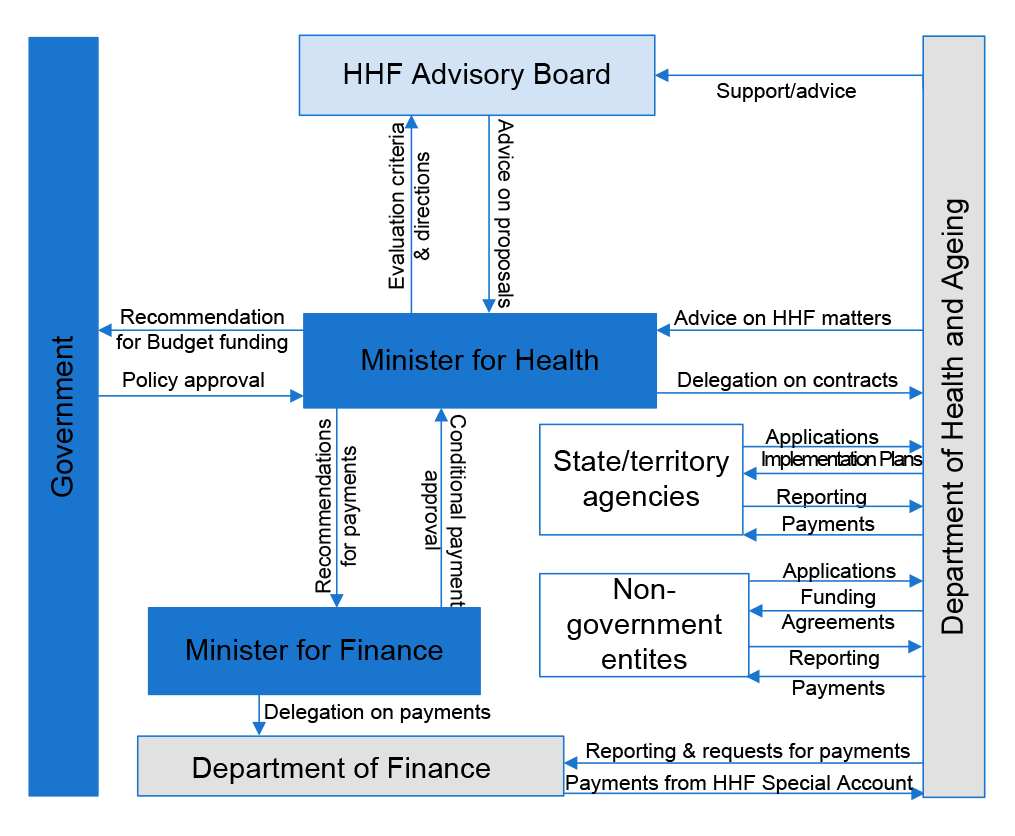

8. Figure S 1 provides an overview of DoHA’s role in administering the HHF.

Figure S 1 Overview of key roles for DoHA’s administration of the HHF

Source: Source: ANAO analysis.

9. Funded projects resulting from three HHF funding rounds were announced in May 2009, early 2010, and May 2011, involving a total of approximately $4.5 billion in Commonwealth financial assistance.

10. The first round (May 2009) included projects that were identified as being ‘shovel-ready’ as a contribution to the Australian Government’s economic stimulus strategy in response to the global financial crisis. Funding totalled approximately $2.61 billion.

11. The second round (early 2010) was targeted at regional cancer centres, with funding of approximately $540 million.

12. The third round (May 2011) focused on regional infrastructure developments in response to the agreements between the Australian Labor Party (ALP) and independent members of parliament which led to the ALP forming a minority government in August 2010. Funding totalled approximately $1.33 billion.

13. The 2011–12 Budget included $475 million for a fourth HHF funding round, also targeting regional infrastructure development. This round was announced on 25 August 20116, with funding for 76 new projects announced in the 2012–13 Budget7; this round was not examined in this audit.

14. HHF funding has been provided to states, territories and other organisations, and this has implications for the application of the Australian Government’s Commonwealth Grant Guidelines (CGGs). With the signing of the National Partnership Agreement on Health Infrastructure in December 20098, HHF funds provided to states and territories were regarded as National Partnership project payments with terms and conditions set out in implementation plans under the National Partnership Agreement. Round 3 agreements with states and territories were executed as project agreements under changes announced by the Australian Government in May 2011. For both types of arrangements with states and territories, HHF funding is not treated as a grant under the financial management regulations9 and is therefore not subject to the CGGs.10 However, funding to other organisations has been subject to the CGGs since these took effect in July 2009.11

Audit objectives and criteria

15. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of DoHA’s administration in supporting the creation and development of health infrastructure from the HHF, including DoHA’s support for the Health Minister and the HHF Advisory Board.

16. To form its opinion, the ANAO used the following criteria drawn from the requirements and principles of the CGGs and the ANAO better practice guide on grants administration12:

- DoHA’s administration of the planning and conduct of the funding rounds effectively supports the purpose of the HHF;

- DoHA provides appropriate support in the selection of projects for funding consistent with the requirements of the Nation-building Funds Act 2008 and the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (FMA Act);

- DoHA’s negotiation and management of funding agreements is effective in delivering projects and outcomes from projects into the future; and

- DoHA develops, collects and assesses output and outcome indicators of HHF performance and reports on them.

17. The audit focused on DoHA’s role in the administration of the HHF. This included the advice and support provided by DoHA: to the Health Minister in directing the work of the Advisory Board; and to the Board and the Health Minister in the assessment and selection of projects for funding.

Overall conclusion

18. The Australian Government’s commitment of $5 billion for health infrastructure through the HHF represents a substantial financial contribution to the Australian health sector, and is one of a number of recent programs intended to support the development of national health infrastructure.13 As a consequence, the administration of programs relating to the funding and development of health infrastructure—traditionally a responsibility of state and territory governments and the private sector—has in recent years become an increasingly significant activity for the Department of Health and Ageing (DoHA), with the HHF by far the largest such program administered by the department.

19. DoHA has generally established effective administrative processes to support the development of infrastructure funded from the HHF. The department has also established sound arrangements to support the HHF Advisory Board and has generally provided effective support to the Health Minister, although it has at times adopted a relatively narrow view of its role. Further, the department’s administrative and support arrangements have improved over time.

20. The administrative arrangements adopted by DoHA have had regard to the legal requirements established by the Nation-building Funds Act 2008 and the Australian Government’s financial management framework, and have incorporated key elements of better practice for grants administration. The core evaluation criteria adopted across funding rounds provided a reasonable basis for assessing proposals against the outcomes intended by the Australian Government and Parliament in establishing the HHF, and the additional tailored guidance provided to applicants adequately supported the specific focus of funding for Rounds 2 and 3. Further, DoHA’s approach to implementing the first three funding rounds resulted in proposals being brought forward by applicants that were of sufficient number and merit, including in the context of the expedited first and third rounds. The first round invited proposals from states and territories within limited timeframes, resulting from the Government’s decision to expedite projects as a means of providing economic stimulus to the economy in response to the global financial crisis.14 The third round was expedited to honour commitments made by the Australian Government to independent members of parliament following the 2010 federal election.15

21. These timing pressures, exacerbated by challenges arising from resource constraints which contributed to a fragmentation of the department’s administration16, have been characteristics of the program since its inception. Notwithstanding these challenges, the department’s administration has demonstrated improvement and refinement over time, informed by practical experience in administering successive funding rounds. While infrastructure expertise was initially limited to that provided by one particular member of the HHF Advisory Board, DoHA has worked with the Board to engage quantity surveyors to develop costing matrices to assist in assessing applications. The department has also established, at the Board’s request, a Centre for Capital Excellence within DoHA, comprising staff with expertise in infrastructure project management.17 The establishment of the Centre will assist with the assessment of project costing and the ongoing management of agreements for funded proposals. The Centre has strengthened the department’s capacity to administer infrastructure programs, reflecting the growing importance of infrastructure-related activity within DoHA’s responsibilities in recent years.

22. In addition to drawing on the expertise of the HHF Advisory Board to inform its administration of the program, DoHA established support arrangements which have facilitated the Board’s ability to make a considered assessment18 of substantial numbers of complex infrastructure proposals19, often within truncated timeframes. The department conducted a useful preliminary analysis of all proposals received from applicants, to determine the extent to which each funding application addressed each evaluation criterion, and provided health policy and administrative expertise to the Board through the secretariat and involvement of the departmental Secretary, who served on the Board as an ex officio member.

23. Taken together, the administrative arrangements established by DoHA, the relevant balance of skills and expertise on the Board, the preliminary analysis of proposals by DoHA and the assessment undertaken by the Board, have made a positive contribution to the administration of the HHF and allowed projects to be advanced. There are some administrative aspects, however, where there is scope for the department to better assist key decision-makers, particularly the Health Minister, in discharging their responsibilities.

24. Currently, the Health Minister does not receive advice on the basis for including some projects in preference to others in Budget proposals, following their assessment by the Advisory Board. The role adopted by the Advisory Board in Rounds 1 to 3 was to conduct an assessment of proposals against the evaluation criteria, determining whether they were eligible or not.20 Following receipt of the Advisory Board’s assessments, the Minister put forward projects for government consideration in the Budget context. For Rounds 1 and 3, the Health Minister was provided with a significant number of eligible projects with a value, if agreed, well in excess of the funds available in the HHF.21 However, the Health Minister did not receive further advice—such as a merit list or scores for individual projects against the evaluation criteria—to support her assessment of the relative merits of the eligible applications; the Minister was only provided with a simple list of eligible projects and the funding sought and recommended, some brief descriptive information relating to particular characteristics of the proposals and any issues that the Advisory Board considered would need attention during negotiations, should the proposal be approved.

25. DoHA advised the ANAO that throughout all rounds it has been the Government’s decision as to which of the eligible projects are to be funded, and that it has not been required that the Board or the department rank projects for the Government. While there is no such requirement, this approach reflects a relatively narrow view of responsibilities in grants administration.22 Appropriately structured advice is particularly helpful where a Minister needs to consider a significant number of complex proposals—in this case 71 eligible proposals in Round 1 and 114 eligible proposals in Round 3.

26. There is also scope for DoHA to expand its advice to the Minister and to financial approvers23 where early payments are proposed for spending proposals relating to the HHF, to take into account the full financial implications of such government decisions and their potential impact on the economical use24 of HHF funds. For Rounds 1 to 3, 14 projects were provided with HHF payments in advance of project requirements, and the ANAO has estimated that the net present value of interest foregone by making payments in advance of requirements is $145 million. Some of the advance payments shifted funding from 2012–13 to earlier years. Two recent projects, the Victorian Comprehensive Cancer Centre in Melbourne and the Midland Health Campus in Perth, are being constructed for state governments under public-private partnership arrangements—the state governments receive Commonwealth funding over five years, whereas the private partners receive payments from state governments over 20 years. In consequence, the state governments in receipt of the advance payments will receive the benefit deriving from those funds—whether in the form of interest income or the ability to put the funds to other uses—rather than the Commonwealth. Further, the funding profiles for these projects were changed from the spending profiles considered by the financial approvers—effectively giving rise to new spending proposals which were not further considered for the purposes of the financial management regulations.25

27. The Royal Hobart Hospital Redevelopment project also received an advance payment of $170 million in June 2011, amounting to over 70 per cent of its HHF funding. The advance payment followed a request by the Tasmanian Premier to the Commonwealth Treasurer that it be made in the 2010–11 financial year26, and resulted in a significant amendment to the original funding profile.27 While making advance payments was a matter for government decision, the departmental advice to government did not document the substantive reasons for the payment other than the urgency of providing the funding before the end of the 2010–11 financial year. Further, the decision to make such a substantial advance in funding has constrained DoHA’s ability to manage risk in the future through regular means such as withholding payments in the event of poor progress.

28. At present, progress in implementing the program is measured and reported by DoHA on a regular basis to the Health Minister. These progress reports, focusing on individual projects, provide an interim measure of benefits realised by the program, as the outcomes achieved through HHF funding will only begin to be realised once projects are completed. The Australian Government’s evaluation criteria for the HHF recognise that the construction of infrastructure is a means to an end, and provide that projects should ‘result in improvements in health outcomes’.28 To date, DoHA has advised government of its intention to implement an evaluation approach focusing on the measurement of progress against construction milestones. While this is a reasonable approach, it is always going to be challenging to measure, in any tangible way, improvements to health outcomes at a project level. There would accordingly be benefit in further developing the evaluation strategy to determine the program’s overall contribution to improving health outcomes.

29. The ANAO has made three recommendations to improve the effectiveness of DoHA’s administration of the HHF: to support the transparency of decision-making around the selection of projects for consideration in the Budget context; to advise the Health Minister and financial approvers of the financial implications of significant payments in advance of need; and to assess the overall contribution of the HHF to improving health outcomes.

Key findings by chapter

Planning and conducting funding rounds (Chapter 2)

30. Effective planning can contribute to realising the full benefit of the Australian Government’s funding for health infrastructure through the HHF.

31. The limited time and resources available to DoHA to establish processes for Round 1 militated against the adoption of a more structured approach to the planning and conduct of that round. At the local and state level, DoHA relied on the infrastructure needs and gaps identified by state and territory governments—a ‘bottom-up’ approach. While the focus of the round at the national level was decided by government, with extra time and resources devoted to the administration of the HHF the department could have utilised a more formal ‘top-down’ strategic planning approach, including independently assessing health infrastructure needs and gaps against government priorities. Where an analysis of needs and gaps was undertaken, it occurred on a project-by-project basis once applications were received.

32. Notwithstanding these time and resource constraints, DoHA’s work in planning and implementing the funding rounds facilitated the identification of projects with potential to achieve improvements in health care. DoHA developed additional selection guidance for particular rounds and identified persons with significant expertise, in areas pertinent to the HHF, to participate on the HHF Advisory Board. The department also worked with the Advisory Board to implement process improvements for Rounds 2 and 3.

Supporting the selection of projects for funding (Chapter 3)

33. The HHF is a hybrid program with grant funding for states and territories not subject to the CGGs, but required for other recipients. However, it is prudent for departments to apply the sound practice principles set out in the CGGs to the fullest extent possible in these circumstances. DoHA advised that in the HHF context, the timeframe and resource constraints in which the department operated meant that the department was restricted in its ability to fully apply these principles.

34. DoHA supported the Health Minister and the Advisory Board in the assessment of projects and its administrative arrangements had regard to the requirements of the Nation-building Funds Act 2008. In addition, many aspects of DoHA’s support to the Minister and Advisory Board were consistent with good practice.29 Where this support fell short, there was an impact on the transparency of the selection processes. The ANAO identified two areas where the transparency of decision-making processes could have been improved. These related to:

- the funding guidelines. While the funding guidelines advise applicants of certain elements of the decision-making process for selecting projects, they do not refer to the processes undertaken within government after the Health Minister has received the Advisory Board’s advice on the eligibility of proposals against the evaluation criteria—specifically, the role played by the Health Minister in deciding on which applications will be submitted for policy approval in the Budget context. To improve the transparency of the selection process, there would be merit in reviewing the funding guidelines to inform applicants of all key aspects in decision-making; and

- advice to the Health Minister in the context of selecting eligible projects to propose for Budget consideration. The Health Minister was only provided with limited information on each eligible proposal, and could have been supported further by being given advice on the relative merits of the eligible applications. Information such as a recommended priority or ranking of projects for funding would have further contributed to the achievement of transparent and defensible selection decisions. The department has advised that it has not been required that the Board or the department rank projects for the Government, reflecting a relatively narrow view of responsibilities in grants administration.

35. While the Board has interpreted its terms of reference as requiring it to provide advice to the Health Minister on whether or not proposals met the evaluation criteria, its terms of reference also provide that it advise the Minister on ‘the extent to which proposals for HHF funding ... meet each of the evaluation criteria’. Advising on the extent to which proposals met each of the evaluation criteria would have provided a basis for advice to the Minister on the relative merits of proposals, and there would have been merit in the department encouraging such an approach or separately informing the Minister.

36. The distribution of projects and funding over the first three HHF rounds has not resulted in any Federal electorate type30 being favoured over others.

Negotiating and managing funding agreements (Chapter 4)

37. Since Round 1, DoHA has progressed a number of process improvements in consultation with the HHF Advisory Board. The improvements have been informed by experience from Round 1 and include the development and implementation of a sound framework to provide guidance to project managers on a range of matters pertaining to the negotiation and management of funding agreements, including a number of difficult administrative aspects of the HHF, such as land tenure and project scope. In addition, DoHA has established a unit with specific construction expertise to provide guidance to project managers. DoHA has also substantially improved the reporting and monitoring arrangements, including through the use of independent certifiers for projects managed by non-government entities.

38. Nonetheless, the negotiation of funding agreements has often taken a significant period of time—in some cases over two years from the time successful projects were announced.31 In addition, in a sample of 13 projects from across the three rounds examined by the ANAO, the resulting funding agreements for two projects (totalling $350 million) did not reflect the project scope as assessed by the Advisory Board, limiting assurance that the projects continued to satisfy the HHF Evaluation Criteria. A further high profile Round 3 project, the redevelopment of the Royal Hobart Hospital, was assessed by DoHA as having one risk at a level that would suggest additional risk management measures should be considered. However, the risk mitigation approach was not reflected in the funding agreement, limiting DoHA’s ability to manage the risk.

39. In the case of 14 projects, the ANAO also identified a misalignment of funding profiles, with DoHA entering into funding agreements that did not match the funding required by recipients to meet their project costs. These projects received substantial payments in advance of requirements which, in the case of two projects, the Victorian Comprehensive Cancer Centre and Midland Health, amounted to $232.9 million and $72.6 million respectively. A third project, the Royal Hobart Hospital Redevelopment, received $170 million in advance payments. The net present value of interest foregone32 by making prepayments for these 14 projects is estimated by the ANAO to be $145 million.

Monitoring and reporting HHF performance (Chapter 5)

40. The Australian Government’s intended outcomes for HHF funded projects were ‘significant, sustainable and measurable ongoing improvements in health care’33 through investment in specific reform priorities. The progress reports received for individual projects provide an interim measure of benefits realised by the program, and DoHA has informed recipients that they will be required to participate in evaluations. However, DoHA has not yet identified key performance indicators to measure outcomes, or settled an evaluation strategy. To date, DoHA’s approach to evaluation has focused on the progress of individual projects against construction milestones, and there would be benefit in further developing the evaluation strategy to determine the program’s overall contribution to improving health outcomes.

Summary of agency response

41. The Department acknowledges the ANAO report and its recommendations.

42. While the HHF was allocated $5 billion in the 2008–09 Budget, the Department was not allocated additional resources for the administration of the HHF until the 2011–12 Budget when departmental funds were reallocated from the savings made from the strategic review of the portfolio. The Department is now managing a portfolio of 224 major, medium and small scale health infrastructure projects situated across Australia in metropolitan, rural and remote locations.

43. As the ANAO report notes, the Department has improved and refined its administration of the HHF over time. Specifically, the Department has:

- centralised and consolidated the management of HHF projects;

- established specific construction expertise and knowledge in the Department through the Centre of Excellence for Capital Works;

- developed the online Capital Works Online Reporting Portal and an independent certification process to monitor the key risks associated with individual projects more closely, independently and accurately; and

- implemented project management and funding arrangements that better reflect the risk, costs and stages of the construction process.

44. The Department will continue to improve and strengthen the administration of the HHF if resources can be identified to do this, taking into account a constrained resource environment and other competing priorities and, in this context, is supportive of the ANAO’s recommendations.

Footnotes

[1] Commonwealth of Australia (2008), Budget Overview. p.1. See <http://www.budget.gov.au/2008-09/content/overview/download/Budget_Overview.pdf> [accessed 5 January 2010].

[2] Nation-building Funds Act 2008 (Cth) s 16(1).

[3] The Future Fund Board of Guardians is established under the Future Fund Act 2006.

[4] The audit covers the period when the former Health Minister, the Hon Nicola Roxon MP, was Minister for Health and Ageing, The current Health Minister, the Hon Tanya Plibersek MP, is the Minister for Health. The Advisory Board includes both independent experts and the Secretary of the Department of Health and Ageing.

[5] HHF Evaluation Criteria 2009. (See <http://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/F2009L00041> [accessed on 7 March 2012].)

[6] Gillard, J (Prime Minister), Crean, S (Minister for Regional Australia) and Roxon, N (Minister for Health and Ageing), $475 Million More for Regional Health Facilities, Parliament House, 25 August 2011. (See <http://www.health.gov.au/internet/ministers/publishing.nsf/Content/mr-yr11-nr-nr161.htm?OpenDocument&yr=2011&mth=08> [accessed 22 November 2011].)

[7] Commonwealth of Australia (2012), Budget Overview. p. 21 See <http://www.budget.gov.au/2012-13/content/overview/html/overview_21.htm> [accessed 17 May 2012].

[8] Under the January 2009 Intergovernmental Agreement on Federal Financial Relations, the Commonwealth committed to the provision of ongoing financial support to the states’ and territories’ service delivery efforts, through a range of means, including national partnership payments to support the delivery of specified outputs or projects, to facilitate reforms or reward those jurisdictions that deliver on nationally significant reforms. The National Partnership Agreement on Health Infrastructure, which was subject to the provisions of the intergovernmental agreement, provided for joint investment in high quality physical and technological infrastructure for the health sector.

[9] Regulation 3A(2) of the Financial Management and Accountability Regulations 1997 provides that certain arrangements are taken not to be grants, including payments to states and territories made for the purposes of the Federal Financial Relations Act 2009, including National Partnership payments.

[10] Department of Finance and Deregulation (2009) Commonwealth Grant Guidelines: Policies and Principles for Grants Administration, paragraph 2.8. See also Finance Circular No 2009/03 Grants and other common financial arrangements, p. 3.

[11] Before the CGGs came into effect agencies subject to the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 were required to comply with the Finance Minister’s Instructions of December 2007 and January 2009.

[12] ANAO Better Practice Guide (2010), Implementing Better Practice Grants Administration.

[13] Other initiatives include: National Partnership Agreement projects; medical research infrastructure projects; the GP Super Clinics program; and primary care infrastructure grants.

[14] The Australian Government announced its intention to fast track infrastructure projects from the nation building funds on 14 October 2008. Letters to states and territories inviting project proposals were posted on 23 December 2008, with applicants given 27 calendar days to submit applications.

[15] The Government entered into agreements between 2 to 7 September 2010, and the invitation to apply for funding under the HHF was opened on 30 September 2010.

[16] DoHA was not allocated additional resources for HHF administration until the 2011–12 Budget, when the government allowed it to reallocate some of the savings made from a strategic review of the portfolio into functions supporting the HHF. As a consequence, the HHF was administered across a number of divisions within DoHA until the formation of a single team in 2011–12.

[17] DoHA advised that these experts were available for Round 4.

[18] The Board assessed infrastructure project proposals against the evaluation criteria to determine whether they are eligible or not.

[19] 135 proposals were considered in Round 1, 37 were considered in Round 2, and 237 were considered in Round 3.

[20] The Board identified eligible projects as either ‘ready to go’ or requiring ‘clarification on details in contract negotiations’. On its face, the Board’s terms of reference also made provision for a broader approach. The Board’s terms of reference state that in providing advice to the Minister, the Board will provide advice regarding the extent to which proposals meet each of the evaluation criteria.

[21] The Advisory Board determined that 71 proposals from Round 1 were eligible, with a value of $6.1 billion as compared to the $5 billion available in the HHF at the time. In Round 3, the Advisory Board determined that 114 eligible proposals were eligible, with a value of $2.4 billion as compared to the $1.8 billion then available in the fund. The issue did not arise in Round 2, as all eligible projects were funded.

[22] See footnote 20.

[23] Regulation 3 of the Financial Management and Accountability Regulations 1997 (FMA Regulations) provides that an approver (that is, a person who may approve proposals to spend public money) means a Minister, an agency Chief Executive or other authorised person. Typically, other persons are delegates of the agency Chief Executive.

[24] FMA Regulation 8 provides that a person must not enter into an arrangement, such as a grant funding agreement, unless a spending proposal has been approved under FMA Regulation 9. FMA Regulation 9 provides that an approver must not approve a spending proposal unless the approver is satisfied, after making reasonable inquiries, that giving effect to the spending proposal would be a ‘proper use’ of Commonwealth resources. Proper use is defined in section 44 of the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (FMA Act) as ‘efficient, effective, economical and ethical use that is not inconsistent with the policies of the Commonwealth’. While recent amendments to the FMA Act, which came into effect on 1 March 2011, added ‘economical’ to the definition of proper use, the Department of Finance and Deregulation has advised that the concepts of efficient and effective already encompassed the concept of economical, which was added to emphasise the requirement to avoid waste and increase the focus on the level of resources that the Commonwealth applied to achieve outcomes. (See Finance Circular No. 2011/01 Commitments to spend public money (FMA Regulations 7 to 12), available at <http://www.finance.gov.au/publications/finance-circulars/2011/docs/Finance-Circular-2011-01-FMA-Regulations-7-12.pdf> [accessed 27 April 2012]).

[25] Note 2 to FMA Regulation 9 provides that at the time the spending proposal is approved, the expectation is that an arrangement or arrangements will be entered into ‘consistent with the terms of the spending proposal’. Finance has advised that Note 2 to the Regulation ‘highlights the need for an arrangement to be entered into consistent with the terms of the spending proposals actually approved by the approver’. (See Finance Circular No. 2011/01, p. 22.)

[26] The Tasmanian Premier advised the Treasurer that ‘the timing of these payments is an important component to facilitate the pre-planning and delivery of the project’.

[27] The original funding profile involved a spread of payments in every year from 2011–12 to 2015–16. The Royal Hobart Hospital redevelopment also received $100 million in other Commonwealth funding, $95 million of which was paid in advance of identified requirements—this advance payment has not been included in the ANAO’s estimate of interest foregone.

[28] The criteria require that each proposal: ‘can demonstrate that the project will contribute to significant, sustainable and measurable ongoing improvements in health care; is supported by a good evidence-base that the project will lead to health outcomes; provides an indication of the relevant economic, social and environmental costs, and relevant health, economic, social and environmental benefits of the proposal; and demonstrates, comparing benefits and costs, that the proposal represents value for money’.

[29] As set out in the CGGs and ANAO Better Practice Guides, Implementing Better Practice Grants Administration (June 2010) and Administration of Grants (May 2002).

[30] Classified on a two-party preferred basis and by seat status of ‘safe’, ‘fairly safe’ and ‘marginal’, as defined by Australian Electoral Commission, and by whether seats were held by the Australian Labor Party, the Coalition or were held by elected members who sat on the cross-benches.

[31] DoHA advised that ‘there are many examples where negotiations were protracted because the Department would not compromise on issues where this would create an unreasonable risk or exposure to the Commonwealth, and this was frequently supported by legal, accounting and other advice’. The ANAO identified a range of factors affecting the time taken to negotiate funding agreements, such as: the size and complexity of the project; degree of advance planning for the project at the time of application; resolution of land tenure; significant changes in project scope or size following funding announcement; and advice required from other Commonwealth agencies.

[32] Through investments of HHF capital by the Future Fund Board of Guardians.

[33] Criterion 2(a) of the HHF Evaluation Criteria and specified in the application guidelines for Rounds 1 to 3.