Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of the Community Aged Care Packages Program

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of DoHA's management of CACPs in fulfilling the legislated objectives of the program.

Summary

Background

ANAO conducted this audit to provide assurance to Parliament that the Department of Health and Ageing (DoHA) was fulfilling its responsibilities in administering the Community Aged Care Packages (CACPs) program.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of DoHA's management of CACPs in fulfilling the legislated objectives of the program.

The CACPs program is a community care program designed to help frail older people with complex daily care needs stay in their own homes, as an alternative to residential types of care.

Unlike many other types of community care provided to Australians who are ageing or disabled, the subsidies paid under it are fully funded by the Australian Government.

Alongside the Australian Government's very much larger residential care program, it is one of three types of care regulated by the Aged Care Act 1997 and the Aged Care Principles promulgated under it.

Though still relatively small, the program has grown steadily, especially since the Australian Government's ‘Staying at Home' policy initiative in 1998, which increased the emphasis on community-based options for aged care. The Government has increased the number of CACPs from 10 000 in that year to 35 574 in 2006. This reflects a planning ratio of 20 community care places for every thousand people aged 70 years and over as at 30 June 2006. In February 2007, this planning ratio was increased to 25 places for every thousand people aged 70 years and over, to be achieved in the next four years.

The CACP, as well as facilitating the wishes of individuals to remain in their own homes, is a cost-effective policy option in that the subsidy for such a package is only approximately a third of that of a residential care subsidy. Funding for community care provided under the Act in 2006–07 is $414 million. CACPs now account for some 5 per cent of total Australian Government aged care expenditure.

The program works by DoHA funding a network of service providers which deliver the actual packages of care to people residing in the Aged Care Planning Regions across Australia. The packages are tailored to the individual needs of recipients.

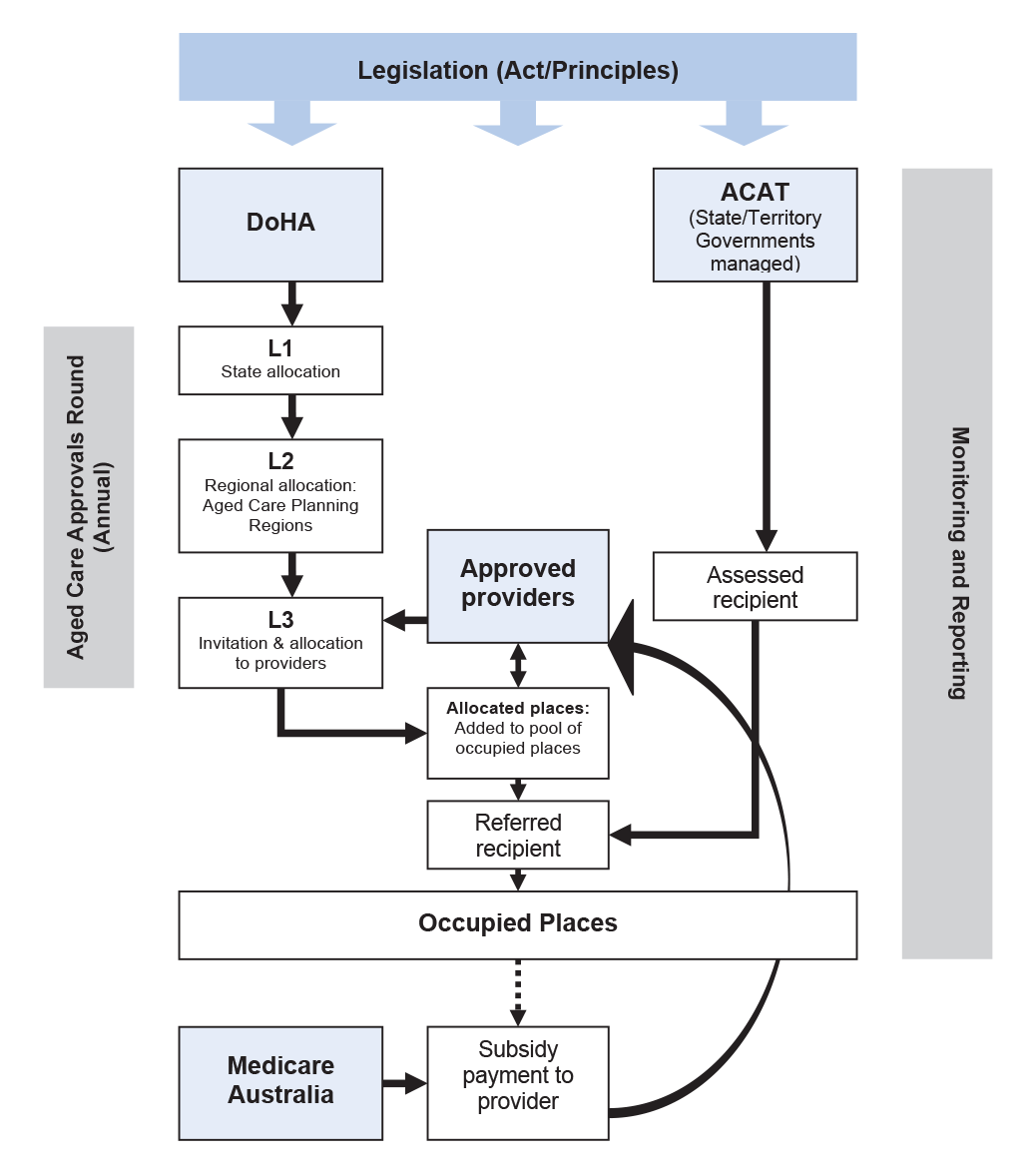

The distribution of the number of new packages created under the Government's planning framework each year is made through a three-level process, the Aged Care Approvals Round, the final level of which is where providers in the aged care planning regions are allocated specific numbers of new places. The providers then receive funds from the Government as a per diem subsidy for the number of occupied places that they hold. Medicare Australia makes the actual payments of the subsidies to providers. Once allocated to providers, the places are held indefinitely.

To obtain entry to a place held by a provider, the potential CACP recipient must be assessed as eligible for a CACP by an Aged Care Assessment Team, a network of which operate under State and Territory management in a joint Commonwealth/State program. Providers which hold vacant or prospectively vacant operational CACP places may then take the eligible potential care recipients into their care.

Legislation

The CACPs program is administered by DoHA under the Aged Care Act 1997 and the ‘Principles' made under it. This Act governs all aspects of the provision to older Australians of:

- residential care;

- community care; and

- ‘flexible care'.

The Act sets out procedures for planning the services, the approval of service providers and care recipients, payment of subsidies to providers, and responsibilities of service providers. Many of the administrative procedures specified in the legislation are common to all three subsidy types.

The legislation specifies ‘special needs groups' such as Indigenous Australians and people of non English-speaking backgrounds as requiring specific attention in the programs funded under it, to ensure their access needs are met.

The legislation also provides for DoHA to allocate limited grant funding (Community Care Grants) to providers, to help promote services in new areas or areas hard to service.

Service delivery environment

Starting 15 years ago as a pilot program, CACPs are now an established part of aged care service provision. They are a valued component of the much larger community care sector, other parts of which draw extensive funding from other spheres of government as well as the Australian Government.

Among the product offerings of the aged care industry, CACPs provide an alternative care option to residential care and are attracting increasing attention as they are much less costly to provide, and they offer value for users as well as providers. They allow the people who can access them, whatever their means, to continue to live independently, despite their having complex care needs.

Providers of CACP services are required by the aged care legislation to perform care planning, care coordination and case management on an individual basis, as well as arranging direct service delivery to them such as personal assistance with showering and travelling to appointments. Recipients of the packages are not means tested but providers may charge fees, adding to the commercial value of the packages in the industry environment.

CACP service providers typically deliver other programs as well as CACPs. They operate in a large, diversifying and increasingly sophisticated service industry sector that encourages sound business practices. Because the scheme of the legislation makes CACPs very similar to residential care beds, providers receive funding through subsidies that are determined by occupied place numbers, not services actually delivered.

DoHA manages its legislative responsibilities for CACPs in this complex service delivery environment. On one hand the CACPs program comprises one small component of a wide spectrum of care provision in an ageing and disability sector that, in the community care area, is populated by many funding agencies, including other Commonwealth agencies and programs as well as State and Territory ones. This environment generates boundary problems and issues for administrative staff in provider organisations, among aged care professionals and among government agencies and staff. Community care recipients can also be faced with having to understand the many pathways to care places, and navigate multiple entry points and eligibility requirements.

On the other hand, the CACP is delivered through the Australian Government passing funding to providers to deliver the actual services. Circumstances created by this ‘arms' length' relationship with the delivery mechanism, and by the ways the aged care service provision industry actually works in its ‘market place', requires DoHA to maximise use of the limited monitoring mechanisms available to it if the department is to ensure that the legislated objectives of the CACPs program are achieved.

The Australian Government, in partnership with the States and Territories, is undertaking a major review of community care (including CACPs) to establish a simplified, streamlined, more accessible and better coordinated community care system. The review is outlined in the Australian Government's planning document The Way Forward: A New Strategy for Community Care issued in 2004. This strategy is shaping intergovernmental reform efforts which were under way during the audit. The Australian Government has initiated a separate review of its own community care programs – the Review of Subsidies and Services.

The CACPs program can be represented diagrammatically as follows.

Figure 1 CACPs Program

Source: ANAO

Overall audit conclusion

The Department of Health and Ageing (DoHA) manages the Community Aged Care Packages (CACPs) program integrally with the other subsidy schemes covered by the Aged Care Act 1997. The program assists ageing people, regardless of their financial circumstances, to continue living independently at home rather than needing to enter aged care homes and hostels to obtain care. It has grown considerably in the numbers of people it supports and the amounts of funds allocated to it since it was introduced as a pilot in the early 1990s. It is now an important component of aged care service provision in the community care sector.

The ANAO considers that DoHA has performed effectively, within developing Australian Government policy, in enhancing the number of new CACP places in ways that balance complex resource constraints, interfaces of CACPs with other Aged Care Act-funded places, and varying regional needs for services.

DoHA's ongoing management of CACPs would be strengthened by improvements in the following areas:

- greater consistency in the practices in DoHA's State and Territory Offices (STOs) with regard to their regional planning and assessment roles in the Aged Care Approvals Round, as well as in the areas of program management and approaches to monitoring outcomes;

- the use and administration of Community Care Grants to stimulate the extension of CACP services to areas where there is unmet or poorly served need;

- improved monitoring of service provider performance including their focus on special needs groups over time; and

- improved reporting to Parliament about the extent of unmet need and provider fulfilment of responsibilities, as required by the legislation.

DoHA's State and Territory Offices (STOs) assess relative need for new CACP places at the regional level using a range of relevant though variable data and sources. While core requirements are being met, individual STOs would benefit from sharing better practice.

Decisions on the assessment of individuals by Aged Care Assessment Teams and the role of providers in deciding whether to accept people into places are specified in the legislation. While DoHA is not directly involved in decisions on admitting people to CACP places, it requires more information from its STOs and CACP providers to satisfy itself that the arrangements operate fairly and consistently across Australian regions. Such information would, for example, allow DoHA to assess whether hard-to-place people are falling through the gaps.

The legislation under which CACPs are administered provides a funding mechanism which DoHA could use in a more proactive and consistent way to stimulate the extension of CACP services to areas where there is unmet need or groups that are poorly served. Uptake of these grants is very small and highly uneven. DoHA could make improvements in how it administers the grants and encourages providers to use the opportunities they present.

DoHA's effectiveness in monitoring the performance of the program has not kept pace with the growing importance of the program in terms of its claims on Australian Government funding and the weight it is now carrying in service provision for ageing Australians. Because the program is run at arms length, through the payment of subsidies and grants to approved providers, DoHA and the service providers are in an interdependent relationship in regard to performance management. How providers understand and discharge their responsibilities determines the quality of the program outcomes. However, DoHA's systems for collecting information about provider performance capture only a part of the relevant material required.

While the Australian Government, with DoHA advice, is participating in intergovernmental efforts to review and reform community care and has introduced a major review of its own community aged care programs, DoHA has not given priority to the introduction of effective and comprehensive information and reporting systems to ensure that the objects of the legislation are being met by the operation of the program. This has meant that, while issues of duplication, overlap, and lack of coordination with other community care services are being addressed, some key questions about program outcomes and the results of activities of service providers are difficult for DoHA to answer at present. For example, while the legislation provides for ‘special needs groups' to receive particular attention in allocation of places, and the ANAO does not disagree with the department that this was generally achieved in the allocation process, how far providers continue to adhere to conditions of grants of places relating to special needs groups year-upon-year is not monitored in an ongoing way.

The aged care legislation imposes particular requirements for reporting on the program to the Parliament on an annual basis. DoHA could improve the content and focus of its reporting in line with legislative requirements. In particular, the department could prepare material for the report that is presented by the Minister for Ageing annually on the operation of the Aged Care Act 1997 which more closely addressed the minimum requirements of the legislation. Such material could be generated by clearer tasking of STO's in the work performed in the annual acquittal of payments to providers, so that, for example, provider performance in their case management roles, and in their implementation of any obligations they have for delivering services to ‘special needs' groups, could be quantified and centrally reported.

Opportunities also exist for the department to use existing data collection arrangements, such as through its annual subsidy acquittal activities, the monthly payments claim processing system and, in the future, DoHA's Quality Reporting initiative, to assemble a fuller picture of how the CACPs program is performing across a wider range of performance characteristics than is being undertaken at present.

Key Findings

CACPs in their service delivery environment (Chapter 2)

Features of the service delivery environment of CACPs in which DoHA must perform its management responsibilities for the program are the extensive and complex nature of the community care sector, and the business circumstances of service providers in the aged care industry.

Case management requirement

The Aged Care Act 1997 requires the effective delivery of case-managed packages of aged care services to people with complex care needs who are not being provided with residential care ?{ the case-management being at an individual care recipient level, undertaken by CACP service providers to whom packages are allocated.

The legislation also requires that CACP recipients are approved against clear assessment that all approved individuals have complex care needs and require coordination services from the provider. Co-ordination of care services is consequently interpreted as a requirement of case management.

As the scheme of the legislation makes CACPs very similar to residential care beds, providers receive funding through subsidies determined by occupied place numbers, not services actually delivered. Providers consider the resulting revenue stream, which may also include the proceeds of any fees levied on recipients, important in their overall operations. This place-based funding contributes to shaping the way providers offer the CACP services. How providers deliver their services in fulfilment of their business strategies determines how well the program works to deliver its legislated objectives.

Despite the pivotal role of providers, DoHA has limited means of obtaining data on service delivery by providers. In particular, it has very limited information on how providers deliver case management services, services that are a significant legislated feature of CACPs and which give CACPs special value to recipients of care.

Overlap with other programs

The Aged Care Act 1997 requires service providers to avoid duplication of services in delivering case-managed packages of aged care services to individual care recipients.

DoHA's Guidelines do not address the boundary between the CACPs program and Veterans Home Care (VHC). Consequently, the ANAO noted considerable variations amongst providers, community organisations and DoHA's State and Territory Offices (STOs) in their understanding as to whether a care recipient who is a VHC recipient could also be held against a CACP place, and vice versa.

As well as VHC, CACPs have many overlapping characteristics with other community care programs, which make them difficult to distinguish from each other and, in many respects, make them difficult for DoHA to manage. The department is involved in major reform efforts that are under way both inter-governmentally and within the Australian Government to simplify the various community care programs, delineate their boundaries more clearly and make them mutually consistent and more accessible to users.

Planning and allocating new places (Chapter 3)

DoHA's activities in planning and allocating new CACP places are undertaken in a policy planning framework determined by the Government from time to time, in accordance with its assessment of the need for places across the various aged care types, and estimates of available budget resources. A major challenge to CACPs program administration is the maintenance of balanced growth of CACPs in the overall aged care program to achieve government-set targets, within the capacity of the community care industry.

The quantitative targets of the policy are determined periodically by the Australian Government as ratios expressed in terms of places per thousand of the population aged 70 years and over, to be achieved by a particular year. The legislation also identifies ‘special needs groups' such as Indigenous Australians and people of non-English-speaking backgrounds as requiring specific attention in the program.

DoHA's role in assembling demographic planning data and industry information is crucial to this policy decision-making by the Government. DoHA directs substantial efforts towards ensuring that the Government receives advice based on accurate and up-to-date data, and that its control, monitoring and reporting arrangements for the creation and distribution of new places at aggregate levels reflect sound practice.

The legislation specifies in some detail how the distribution of new CACP places should be undertaken through three successive ‘levels' of the annual Aged Care Approvals Rounds, where the newly-created places are distributed among:

- the States and Territories; then to

- Aged Care Planning Regions within each State and Territory; and finally

- allocated to interested service providers in response to submissions from them.

DoHA's STOs perform the main assessment roles in the later two of these three processes. While the legislation's core requirements are generally met, the procedures employed by STOs vary more widely than different circumstance in States would suggest is appropriate. Identification of requirements of some of the ‘special needs' groups specified in the legislation is conducted with varying degrees of rigour and effectiveness. There would be significant benefits for the overall consistency and quality of delivery if DoHA was to disseminate better practices from a review of the different methodologies used in each STO to brief Aged Care Planning Advisory Committees.

As DoHA is required by the legislation to ensure that aged care services are targeted towards people with the greatest need for those services, and that access to them is facilitated regardless of race, culture, language, gender, economic circumstances or geographic location, the end result of each Aged Care Approvals Round should be that the distribution of places numbers and places allocation to providers is optimum in regard to these objectives. The ANAO found that the systems used by the department to ensure that this happens at the regional and provider level could be improved. How the department intends to address gaps and shortfalls in CACP places at these levels could also be made more explicit in decision-making.

Community Care Grants

The Aged Care legislation also provides for DoHA to allocate limited grant funding (Community Care Grants) to providers, to help promote services in new areas or areas hard to service. However, the department has not established sound procedures nationally to support the important function of meeting unmet or poorly served needs which can occur in regional Australia.

Providing places to people (Chapter 4)

The aged care legislation requires decisions to be made about a person's access to a CACP place at two key points:

- the professional assessment of the person's needs by an Aged Care Assessment Team (ACAT), which determines whether a person is eligible for a place; and then

- the decision of a service provider to admit the eligible person to a care place in the provider's possession.

Neither of these decision points is under the direct control of DoHA. However, they both have formal status under the Australian Government's aged care legislation administered by DoHA. Legislation requires ACAT approvals for CACPs to be made against clear assessment that all approved individuals have complex care needs and require coordination services from the provider.

ACAT assessments

The ACATs operate in a joint Commonwealth/ State/ Territory funding framework and are administered by the States. They function as delegates of DoHA when making their eligibility decisions, using guidelines and employing training provided by DoHA. The Australian Government, and DoHA at departmental level, are engaged in extensive reform efforts to improve the operation of the ACAT system.

Notwithstanding the departmental guidelines and the training provided by DoHA, the ANAO found considerable variations between ACAT practices on a State/Territory basis and among ACATs individually. While the reform processes under way were intended to address these and other concerns, the operation of the ACATs in their roles as departmental delegates could be improved, so as to achieve better national consistency in regard to:

- the ACAT focus on what it is that makes a CACP appropriate for a person (as distinct from other aged care types, or nothing); and

- in the ACATs' practices in referral of eligible people to providers.

Monitoring providers' decisions on acceptance of people into CACPs

DoHA has very limited information about providers' decisions on the placement of people assessed as eligible for a CACP, into CACP places. Relevant database material cannot produce fit-for-purpose data about waiting times and waiting numbers to provide information about:

- demand or supply;

- the queues of people awaiting assessment who want immediate placement; or

- those assessed waiting for placement.

Without at least some of this information, and acknowledging that at aggregate level there will continue to be an excess of demand over supply of places so long as resources are constrained, DoHA cannot assure itself about the effectiveness of arrangements for this final step in the pathway to a CACP place.

Monitoring and reporting program outcomes (Chapter 5)

The key objectives of the CACPs program are to provide:

- coordinated aged care packages tailored to meet the complex care needs of people, delivered where care recipients live; and

- an effective alternative to residential aged care for people who wish to stay at home.

The aged care legislation also requires that in deciding the allocation of places, DoHA give particular attention to the requirements of groups with special needs. Furthermore, the legislation specifies minimum content for the annual report that the responsible Minister must cause to be laid before each House of the Parliament on the operation of the Aged Care Act 1997. Those matters that are directly relevant to CACPs include:

- the extent of unmet demand for places; and

- the extent to which providers are complying with their responsibilities under the Act.

The aged care legislation points towards a wide range of performance characteristics that would be suitable for the CACPs program and for assessing and reporting on its improvement, including at the aggregate, State, regional and provider levels. However, DoHA's performance indicators focus on the creation of new places at the aggregate level, especially meeting the Government's target ratio of service provision. The department's performance indicators do not address the quality of CACPs program outcomes. In particular, they do not take into account the specified content of the annual reports required to be prepared annually on the operation of the Aged Care Act 1997, which address the assessment of unmet need and the extent to which providers are complying with their responsibilities under the Act.

Monitoring providers' performance in program delivery

The ANAO found that DoHA's acquittal system does not capture the performance of providers in regard to their fulfilment of all conditions of allocation of places to them, especially case management requirements and the targeting of people with special needs:

- a common gap in DoHA's STOs' monitoring of service provision was measuring the time providers spent in providing case management and/or care coordination services, as opposed to individual services; and

- while all deeds of agreement reviewed by the ANAO had a requirement for a minimum ratio of financially and socially disadvantaged people in the care places occupied, providers are not required to report specifically on their performance in meeting these conditions of allocation.

The ANAO also found that, in its present form, DoHA's Quality Reporting initiative is not intended to be used to capture quantitative data that could be used nationally to report on providers' performance of their responsibilities.

Overall, DoHA is constrained in its ability to provide comprehensive quantitative reporting on many aspects of program delivery, especially the phase of it that is the responsibility of providers. The constraints mainly arise from the complexity of interfaces between the CACPs program and the other aged care programs including those in the community care sector, and the limited information that DoHA has on the performance of CACP service providers.

Recommendations

The ANAO has made eight recommendations to assist DoHA improve its administration of the Community Aged Care Packages Program. DoHA has agreed to all recommendations, one with qualification. The second recommendation involves consultation between DoHA and DVA. Both agencies have agreed to that recommendation.

DoHA's response

The Department welcomes the audit findings and will develop a program of work to meet the objectives identified in the response to the audit recommendations, noting that some aspects will involve a stepped process over several years. Funding provided though the Securing the Future of Aged Care for Australians measure will provide resources to improve monitoring of service provider performance as part of a broader quality initiative. The Department will develop better practice guidelines and improve consistency in the practices of its State and Territory Offices and has already commenced action to address particular issues, including clearer Aged Care Approvals Round documentation and guidelines for the process of assessing applications. The Department is working with state and territory governments, through the 2006 Council of Australian Governments initiative to improve the Aged Care Assessment Program including the implementation of a national training strategy for Aged Care Assessment Teams. The Department will undertake to provide additional information in annual reporting on the operation of the Aged Care Act 1997, as required under Section 63-2 of the Act.

DVA's response

The Veterans' Home Care (VHC) program is a Department of Veterans' Affairs (DVA) program to help eligible veterans and war widows/widowers with low-level needs remain living independently in their homes for longer. The VHC program is not designed to meet the needs of veterans or war widows/widowers with complex or high-level needs. If such cases are identified by the VHC assessment agency, they are referred to more appropriate programs of care, such as the Community Aged Care Packages (CACP) program.

Where VHC clients are referred to other higher care programs, the VHC program Guidelines (Section 5.9) provide specific guidance to VHC assessment agencies on:

- what DVA services and under what circumstances these services may continue to be provided;

- the management of VHC clients receiving CACPs and other packages; and

- the necessary interactions with case managers of other programs.

DVA welcomes the recommendation by ANAO for DoHA to promulgate guidelines for its CACP Program to ensure a consistent approach to veterans as a special needs group in their access to CACPs. The introduction of clear guidelines in this area will significantly assist in the understanding by CACPs managers and providers of how the VHC program should interact with the CACP program to the benefit of veterans.