Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of the Adult Migrant English Program Contracts

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- Contracts for the delivery and quality assurance of delivery of the Adult Migrant English Program (AMEP) are valued at over $2 billion and will have been in place for 7 years and a half years before contracts are replaced.

- The ANAO has audited the management of AMEP contracts once previously (in 2001), with the audit report including six recommendations, all of which were agreed to.

- The ANAO audited the Department of Home Affairs, which has been responsible for AMEP since 2019 and the contracted quality assurance provider, Linda Wyse and Associates.

Key facts

- English tuition has been contracted for delivery by 13 providers, across 58 contract regions, including one distance learning provider.

- Quality assurance of tuition providers is contracted for delivery by one firm nationally.

What did we find?

- The design and administration of the AMEP contracts has not been effective.

- Appropriate contractual arrangements are not in place with the 13 general service providers.

- The general service provider contracts have not been appropriately managed, including by the department amending the contracted performance framework such that only one of the four key performance indicators remains.

- Department of Home Affairs has significantly changed the nature of services provided by the contracted quality assurance provider substantially away from quality assurance over the work of the general service providers.

What did we recommend?

- There were 10 audit recommendations.

- The department agreed to all recommendations. Linda Wyse and Associates also agreed with all recommendations.

$287m

average contract value per year of the program.

183653

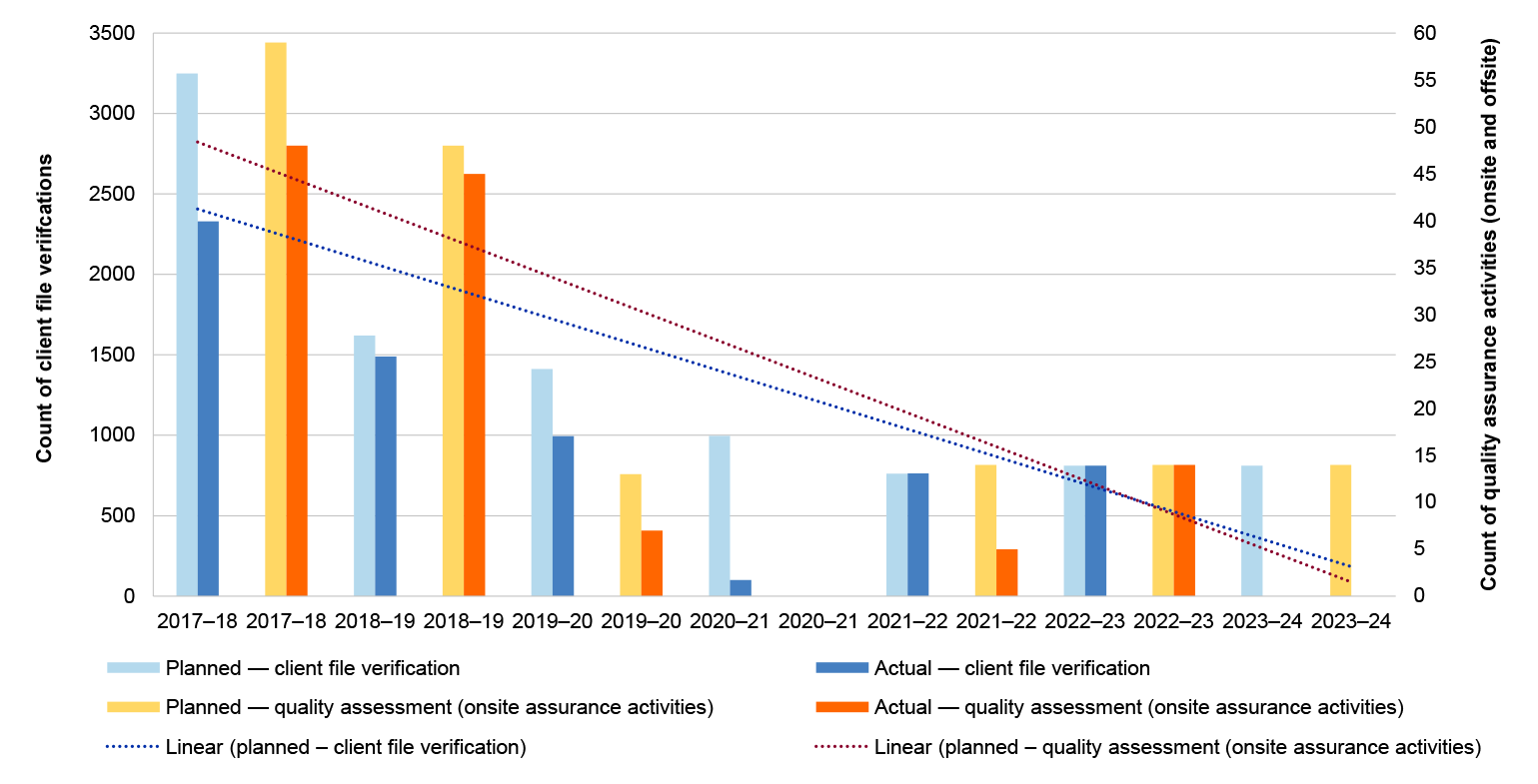

active students in since 1 July 2017.

Summary and recommendations

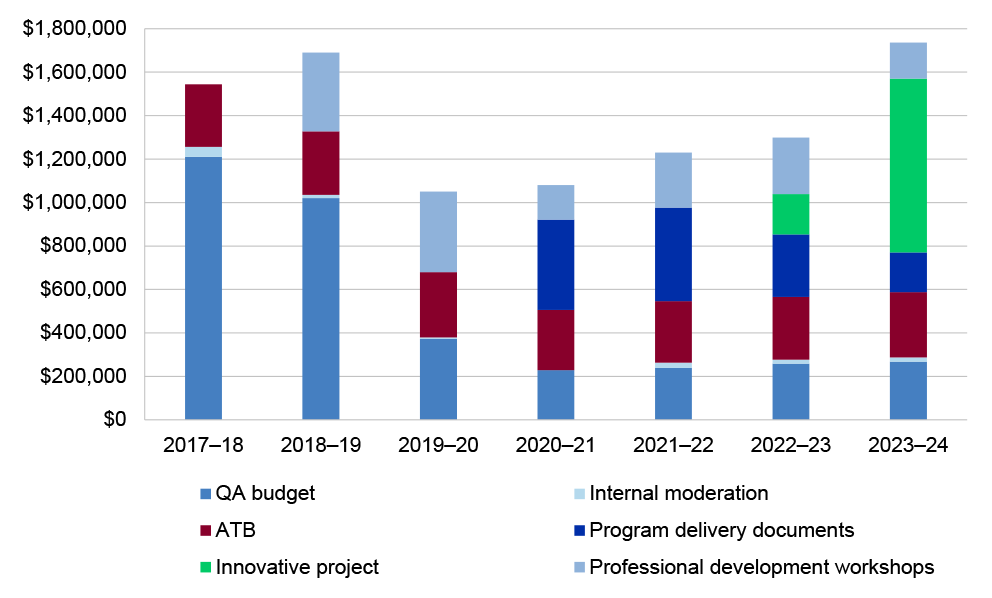

Background

1. Established in 1948, the Adult Migrant English Program (AMEP) provides free English tuition to eligible migrants and humanitarian entrants with no or low English levels.1 The program supports an average of 53,000 participants annually. The design of the program recognises that learning English can help migrant settlement.

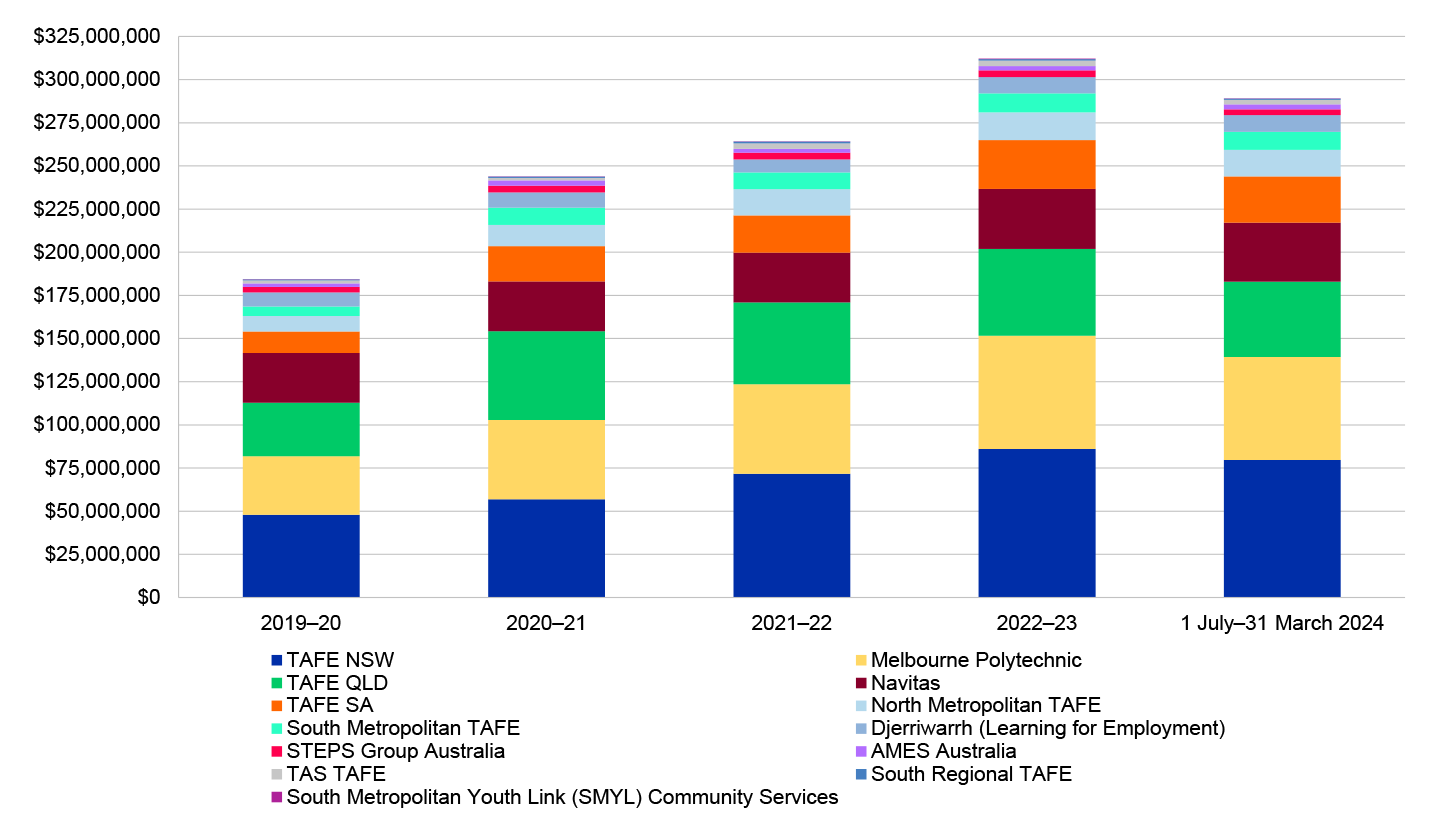

2. Contracted delivery of the Adult Migrant English Program (AMEP) has been in place for 25 years.2 The current contracts commenced in 2017 and deliver English language lessons in over 300 locations and online, to clients in metropolitan, regional and remote locations in Australia. The 15 contracts3 were initially valued at $1.22 billion which had increased by 75 per cent) to more $2.153 billion as at April 2024, representing an average annual contract value of $287 million. There is also a contract for quality assurance, for which the reported value increased from $6.15 million to $22.52 million. The October 2022 Federal Budget included $20 million to provide more flexible delivery options for the program and to increase case management support for students (to deliver on an election commitment).

3. All contracts were due to end on 30 June 2023. These contract arrangements were extended in December 2022, to 30 June 2024 (with work orders under the contracts not due to expire until 31 December 2024), after a government decision to delay implementation of a further new AMEP business model.4 The request for tender for new AMEP contracts was to be issued in September 2023, and new arrangements to commence 1 January 2025. On 30 November 2023, the Minister for Immigration, Citizenship and Multicultural Affair approved a further delay5, with no new release date advised. In February 2024 the department advised the ANAO that advice to the minister and a new policy proposal were in development and the release date of the request for tender is dependent on government agreement to a new model and implementation date.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

4. Contracts for the delivery and quality assurance of delivery of AMEP are valued at over $2 billion and will have been in place for at least seven and a half years by the time they are replaced. The ANAO has audited the management of AMEP contracts once previously (in 20016), with the audit report including six recommendations, all of which were agreed to. Those recommendations related to improving program performance management and reporting; strategic management and coordination; management of financial risk; and monitoring of contractor performance.

5. The audit provides assurance to the Parliament that the department is appropriately administering the Adult Migrant English Program contracts.

Audit objective and criteria

6. The objective of the audit was to assess whether the design and administration of AMEP is effective.

7. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level criteria were applied:

- Are appropriate contractual arrangements in place?

- Are the service provider contracts appropriately managed?

- Are contracted quality assurance services being delivered to an appropriate standard?

8. In addition to auditing the management of contracts by the Department of Home Affairs, the audit used the follow the money power provided under paragraph 18B(1)(b) of the Auditor-General Act 1997 to examine the performance of Linda Wyse and Associates (LWA), the quality assurance provider for the AMEP.

Conclusion

9. The design and administration of the Adult Migrant English Program contracts has not been effective.

10. Appropriate contractual arrangements are not in place with the 13 general service providers. The contracts are continuing to operate past their stated completion date, despite there being no extension options in the contracts. While the contracts, and associated instructions, clearly outline the contracted deliverables:

- there have been significant variations made to each of the contracts, with insufficient documentation to evidence that each variation represented value for money to the Australian Government and the records of the variations are inadequate;

- there are deficiencies in the processes by which the department has engaged advisers and contracted the existing service providers to identify areas that could benefit from adaptation of new ideas and innovative service delivery to enhance client outcomes (referred to as innovative projects);

- there is no probity plan for the management of the contracts, and inadequate departmental transition planning for the end of the contracts.

11. The general service provider contracts have not been appropriately managed. A comprehensive set of contracted performance indicators was in place when the contracts were first signed, but that framework has been amended over time such that it no longer addresses the educational outcomes being achieved by students, the accuracy of provider assessments of student educational outcomes or the timeliness of service provider provision of data to the department. The only indicator that has remained relates to the extent to which eligible students commence in the program. In addition:

- invoice verification processes have not been sufficiently robust; and

- the department has not implemented a previously agreed recommendation that it would use complaints data from providers to inform and improve service delivery for students.

12. In its administration of the contract with the firm engaged as quality assurance provider, the Department of Home Affairs (Home Affairs) has not obtained appropriate assurance over the work of the 13 contracted general service providers. Key factors that led to this result include:

- the contractual performance framework was diminished after the quality assurance provider was selected and the contract signed, and key performance indicators have not been met notwithstanding that the targeted quantity of work has been reduced over time by the department;

- the approach to planning quality assurance work is not risk based; and

- Home Affairs has significantly changed the nature of services provided away from quality assurance over the work of the general service providers. For 2023–24, the department decided that 15 per cent of the budget for the provider would be spent on quality assurance work, down from 78 per cent in the first year of the contract.

Supporting findings

Contractual arrangements

13. The service provider contracts, and associated Service Provider Instructions, clearly outlined the contracted deliverables. (See paragraphs 2.2 to 2.7)

14. Significant variations have been made to each of the contracts since they were signed such that the terms and conditions are now different in important respects from the procurement opportunity that was presented to the market. The department has not kept adequate records of the contract variations that have occurred. Home Affairs’ records of decisions to vary the contracts do not adequately address value for money considerations and therefore do not demonstrate that each of the variations has been appropriate. (See paragraphs 2.8 to 2.30)

15. Contracted advisers have not been engaged through appropriate procurement processes. In addition to engaging advisers, the contracts with service providers were amended to enable the department to engage them to deliver ‘innovative projects’ that are additional to the services they were contracted to deliver at the conclusion of the 2017 procurement process. (See paragraphs 2.33 to 2.42)

16. There is no probity plan for the management of the AMEP contracts. As a result, there are no conflict of interest declaration and other probity risk management requirements in place for the AMEP contracts. (See paragraphs 2.47 to 2.49)

17. Appropriate transition management plans are not in place. The contracts were due to end on 30 June 2023 and did not include any extension options yet, due to delays with the procurement process to replace them, they are continuing to operate past the stated completion date. As of December 2023, the department had not finalised and approved a transition out plan for the existing contracts, notwithstanding that those contracts were originally due to expire in June 2023 (they are now due to expire on 30 June 2024, with work orders under the contracts due to expire on 31 December 2024). Further, the draft transition in plan is substantively incomplete, reflecting the uncertainty about the future contractual arrangements (the tender process for replacement contracts has been subject to delays). (See paragraphs 2.53 to 2.63)

Service provider contract management

18. The introduction of an information technology system to support the department’s oversight of contractor service delivery has not proceeded. The department’s continued use of a system that was not replaced as planned has not provided a sound basis for monitoring service provider performance, or to support the payment of invoiced amounts. The failure to introduce the planned new system also required the department to make additional payments to the service providers to recognise the additional administrative burden placed on them, and has meant one of the four key performance indicators for the general service provider contracts has not been applied. (See paragraphs 3.2 to 3.9)

19. The contracts, when first signed, established a performance measurement and management framework for the general service providers, focused on four key performance indicators (KPIs). The request for tender that led to the contracts being signed had stated that the four KPIs represented ‘a minimum performance standard that service providers will be expected to meet and it is an expectation of the department that service providers will strive to deliver above these standards’. The department has amended the framework over time such that the suite of four KPIs have not been used to inform contract management:

- none of the four KPIs were applied for the first 12 months of the contract term;

- the KPI relating to data timeliness has not been applied at all;

- the target addressing the KPI relating to the accuracy of service provider assessments of client learning outcomes was first reduced and was later paused in November 2021 for the remaining term of the contracts; and

- the English attainment progress KPI has been removed. (See paragraphs 3.10 to 3.20)

20. The invoices for general service providers have not been appropriately verified. Invoicing and payments to the 13 AMEP general service providers has not consistently adhered to the contracts with issues identified in a number of areas including the application of goods and services tax, fee indexation and backdating fee increases. (See paragraph 3.24 to 3.28)

21. The Department of Home Affairs does not have appropriate complaint resolution processes for the delivery of services under the Adult Migrant English Program, and has not implemented an ANAO recommendation from a 2000–01 audit report7 that it had agreed to. While the contractual framework includes appropriate arrangements to enable the department to monitor the number and nature of complaints being received by the 13 general service providers, the department has not effectively administered those arrangements. As a result, the department is unable to assure itself that service providers are meeting their obligations for the timely and effective handling of complaints, and the department does not analyse complaints data to identify opportunities to improve service delivery across the program. (See paragraph 3.29 to 3.34)

Quality assurance services

22. The contracted performance management framework has not been appropriately implemented by Home Affairs. The KPI framework was changed after the completion of the procurement process to select the provider of quality assurance services, and does not reflect the full scope of services expected of the contractor. Further, notwithstanding that the department has reduced over time the amount of quality assurance reviews required to be undertaken8, in only two years has the provider reported undertaking the (reduced) number of client file verifications specified in the annual plan (a shortfall of 27 per cent in the first six years) and has only undertaken the (reduced) number of onsite quality assurance reviews in 2022–23 (a shortfall of 20 per cent in the first six years). (See paragraphs 4.2 to 4.10)

23. Performance of AMEP service providers has not been a direct input into the development of quality assurance work. The department has not consistently implemented a risk-based approach to quality assurance work. The department decided to cease using a risk-based approach in 2020–21 and a proportional approach, based on student populations, was instead implemented from 2021–22. (See paragraphs 4.15 to 4.27)

24. The budgeting for, and tasking of, the quality assurance provider, by Home Affairs, has significantly changed the nature of services provided under this contract. The contracted provider has identified that the changes have redirected services from the intended purpose of the quality assurance role. As a result of the department refocusing the work of the contracted quality assurance provider to the delivery of professional development and development of ‘program delivery documents’, the quality assurance activities planned and delivered have not appropriately monitored the performance of the contracted general service providers. (See paragraphs 4.31 to 4.68)

25. The contractual arrangements in place to not allow an evidence-based assessment of whether the work of the quality assurance provider has improved the performance of the general service providers. (See paragraphs 4.73 to 4.77)

26. The invoices for the AMEP quality assurance provider have not been appropriately verified or paid in accordance with the AMEP quality assurance contract. (See paragraphs 4.78 to 4.79)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.18

To meet its record keeping obligations and ensure appropriate performance management of contracts, the Department of Home Affairs develop a complete record of all contract variations, including those variations agreed through correspondence, together with a master version of the contracts that incorporates all variations.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Linda Wyse and Associates response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.31

When considering potential contract variations for the Adult Migrant English Program, the Department of Home Affairs make a decision-making record that addresses whether the proposed changes represent value for money, including by reference to the value for money assessment that underpinned the procurement decision-making prior to the contract being awarded.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Linda Wyse and Associates response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 2.43

The Department of Home Affairs introduce stronger governance arrangements over the process by which it engages service providers under the Adult Migrant English Program to identify areas that could benefit from adaptation of new ideas and innovative service delivery to enhance client outcomes including opportunities to offer these opportunities to open competition.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Linda Wyse and Associates response: Agreed

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 2.50

The Department of Home Affairs develop a probity plan to govern the management of contracts for the Adult Migrant English Program.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Linda Wyse and Associates response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 2.64

The Department of Home Affairs improve its transition planning for the Adult Migrant English Program by:

- finalising the transition out plan for the current contracts and, for future contracts, preparing the transition out plan early in the new contract period; and

- aligning the development of the transition in plan for the replacement contracts with the preparation of the approach to market documentation.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Linda Wyse and Associates response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 3.21

The Department of Home Affairs establish a comprehensive suite of performance indicators and targets in the service provider contracts for the Adult Migrant English Program, require that service providers report performance against the indicators and targets and take appropriate contract management action where performance is below requirements.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Linda Wyse and Associates response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 7

Paragraph 3.35

The Department of Home Affairs analyse and review complaints data from the general service providers for the Adult Migrant English Program to inform and improve service delivery to students.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Linda Wyse and Associates response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 8

Paragraph 4.11

The Department of Home Affairs strengthen the contractual performance management framework for the provision of quality assurance services for the Adult Migrant English Program.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Linda Wyse and Associates response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 9

Paragraph 4.28

The Department of Home Affairs undertake a systematic, documented, evidence-based approach to determining and targeting quality assurance activities based on general service provider performance and other risk information known to the department.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Linda Wyse and Associates response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 10

Paragraph 4.69

The Department of Home Affairs give greater emphasis to monitoring the quality of services being delivered to students by the contracted general service providers.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Linda Wyse and Associates response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

27. The proposed audit report was provided to Home Affairs and Linda Wyse and Associates (LWA), the quality assurance provider for the AMEP. The letters of response are included in Appendix 1. Summary responses from Home Affairs and LWA are reproduced below.

Department of Home Affairs

The department has agreed to the recommendations made by the ANAO. While acknowledging room for improvement, the Department does not consider the ANAO’s findings, listed below, reflect and recognise the environment in which the AMEP Agreements were being delivered:

- The design and administration of the current Agreements have not been effective, and

- The appropriate contractual arrangements are not in place.a

The AMEP has successfully delivered English language tuition to eligible migrants and humanitarian entrants, including during a period of unprecedented disruption due to the impact of COVID-19.b

Since implementation of Administrative Orders, transferring the administration of the AMEP to the department in July 2019, the department has sought to strengthen processes, procedures and the technology that support the management of the Agreements.c Several recommendations made have previously been identified by the department as opportunities for improvement in the design of the future contract/s.d The procurement process for this future contract cycle has been delayed due to the change of Government and subsequent program setting reviews. Through the future contract/s, the department will implement an enhanced performance management framework, including key performance indicators supporting the strategic intent of the AMEP and effective performance management, and deliver a new IT system supporting the administration of the contract/s.

ANAO comments on Department of Home Affairs summary response

28. ANAO comments regarding Home Affair’s summary responses are included below, with rejoinders to the letter of response included within Appendix 1.

- An important consideration in the ANAO’s conclusions that the design and administration of the contracts has not been effective relates to the Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) for service providers. Of the four KPIs identified included in the contracts that commenced in July 2017 to establish ‘a minimum performance standard’ that service providers were expected to meet, three are no longer in place, including the KPI relating to the desired program outcome of progressive English attainment by students (see paragraphs 3.11 to 3.20).

- The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the program, and/or how the impact was addressed or not addressed by the department, is discussed throughout the audit report (paragraphs 1.4, 2.7, 2.26 and 2.27, 3.15, 4.25, 4.31, 4.36, 4.57, 4.60 to 4.68 and Table 3.1).

- Administration of the AMEP contracts transferred into the Department of Home Affairs nearly five years ago, in July 2019. Relevant records and some key staff moved with the program to the Department of Home Affairs (see footnote 28). Consistent with the ‘Collaborative Agreement’ signed by the two departments in October 2019, changes made since 2019 by the Department of Employment and Workplace Relations to the parts of the head contracts that apply to both AMEP and SEE have occurred through engagement with, and input from, the Department of Home Affairs. Home Affairs agreed that the department responsible for the SEE program would be the lead agency, and that any variations to the general clauses in the contract must be agreed by both departments.

- The ANAO notes the scope of its work has been on the current contracts and as such the findings relate to the administration of the current contracts. The ANAO has not audited the design of future contract/s, for which no request for tender has yet been issued.

Linda Wyse and Associates

LWA welcomes the report and its recognition that the Adult Migrant English Program (AMEP) contract faced many challenges in its tenure. The disruption caused by COVID-19 cannot be underestimated; it was the impetus for the change in work carried out by LWA to support AMEP providers facing the challenges of moving from face-to-face classes to online delivery for a diverse cohort of clients, who personified the digital divide.

LWA agrees in full with the 10 recommendations given in the report, recognising the importance of assuring quality and ensuring documentation accurately captures quality assurance activities. We feel strongly that monitoring the quality of services being delivered to the student is an important duty of the quality assurance provider and welcome the ANAO recommendation to give more emphasis to this activity.

LWA is committed to working with the Department to implement the recommendations and is initiating steps, as noted against the relevant recommendation, to address the areas identified for improvement.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

29. Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Contract management

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Established in 1948, the Adult Migrant English Program (AMEP) provides free English tuition to eligible migrants and humanitarian entrants with no or low English levels.9 The program supports an average of 53,000 participants annually (see Appendix 3). The design of the program recognises that learning English can help migrant settlement.

1.2 Contracted delivery of the Adult Migrant English Program (AMEP) has been in place for 25 years.10 The current contracts commenced in 2017 with AMEP providers contracted in each state and territory, delivering English language lessons in over 300 locations and online, to clients in metropolitan, regional and remote locations in Australia.11 Data published on AusTender initially valued the 15 contracts12 with 14 providers13 at $1.22 billion which had increased by 75 per cent to $2.15 billion as at February 2024, representing an average annual contract value of $287 million. There is also a contract for quality assurance, for which the reported value increased from $6.15 million to $22.52 million.

1.3 A 2019 Investing in Refugees Investing in Australia report14 found that the program had unacceptably poor results due to too few participants (seven per cent) achieving functional levels of English at the conclusion of their course. The report also found a significant underutilisation of the program, with many participants not completing the hours they had available.

1.4 The COVID-19 pandemic impacted on the delivery of the AMEP by the general service providers, given that the contracts involved face-to-face tuition. The COVID-19 pandemic also impacted on the delivery of onsite assessments by the quality assurance provider.

1.5 In 2021, changes were made to the program. They allowed eligible migrants access to unlimited hours of lessons by removing the previous 510 hour limit; and increased alignment with the AMEP’s partner program, Skills for Education and Employment (SEE) by increasing the standard of eligibility and attainment from ‘functional’ to ‘vocational’ English.15 The October 2022 Budget included $20 million to provide more flexible delivery options for the program and to increase case management support for students (to deliver on an election commitment).

Administrative responsibility for the program

1.6 Administration of the AMEP contracts transferred into the department from the Department of Education and Training through Machinery of Government changes in July 2019. The procurement process that resulted in the current AMEP contracts was conducted when the program was the responsibility of the then Department of Education and Training (the SEE program is now administered by the Department of Employment and Workplace Relations).

1.7 Changes made since 2019 by the Department of Employment and Workplace Relations to the head agreements that apply to both AMEP and SEE have occurred through engagement with, and input from, the Department of Home Affairs. This is consistent with a ‘Collaborative Agreement’ signed by the two departments in October 2019 under which Home Affairs agreed that the department responsible for the SEE program would be the lead agency. The Collaborative Agreement requires that any variations to the general clauses in the contracts must be agreed by both departments. The two departments have the ability to make variations to their respective schedules within the contracts, and are to inform each other as a matter of courtesy of any variations to their respective parts of the contracts.

Procurement process to replace the contracts

1.8 All contracts were due to end on 30 June 2023, with the request for tender for new contracts to be released on 30 April 2022. The contracts were extended in December 2022 to 30 June 2024 (with work orders under the contracts not due to expire until 31 December 2024), after a government decision to delay implementation of a further new AMEP business model.16 The request for tender for new AMEP contracts was to be issued by September 2023, and new arrangements to commence 1 January 2025. On 30 November 2023, the Minister for Immigration, Citizenship and Multicultural Affairs approved a further delay17, with no new release date advised. In February 2024, (22 months after the request for tender was to have been released) the department advised the ANAO that advice to the minister and a new policy proposal were in development and the release date of the request for tender is dependent on government agreement to a new model and implementation date.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.9 Contracts for the delivery and quality assurance of delivery of AMEP are valued at over $2.15 billion and will have been in place for at least seven and a half years by the time they are replaced. The ANAO has audited the management of AMEP contracts once previously (in 200118), with the audit report including six recommendations, all of which were agreed to. Those recommendations related to improving program performance management and reporting; strategic management and coordination; management of financial risk; and monitoring of contractor performance.

1.10 The audit provides assurance to the Parliament that the department is appropriately administering the Adult Migrant English Program contracts.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.11 The objective of the audit was to assess whether the design and administration of AMEP is effective.

1.12 To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level criteria were applied:

- Are appropriate contractual arrangements in place?

- Are the service provider contracts appropriately managed?

- Are contracted quality assurance services being delivered to an appropriate standard?

1.13 This audit examined the design and administration of the AMEP contracts entered into in 2017, including associated variations and work orders and preparation and transition planning for the program post-30 June 2024.

1.14 The ANAO did not audit the procurement processes for establishing the AMEP contracts.

1.15 In addition to auditing the management of contracts by the Department of Home Affairs, the audit used the follow the money power provided under paragraph 18B(1)(b) of the Auditor-General Act 1997 (the Act) to examine the performance of Linda Wyse and Associates (LWA), the quality assurance provider for the AMEP.

Audit methodology

1.16 The audit method included:

- examination of records;

- meetings with staff; and

- analysis of reports from information systems.

1.17 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $583,000.

1.18 The team members for this audit were Hannah Conway, Tamara Duncan, Amita Robinson, Calli Stewart and Brian Boyd.

2. Contractual arrangements

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether appropriate contractual arrangements in place with the general service providers.

Conclusion

Appropriate contractual arrangements are not in place with the 13 general service providers. The contracts are continuing to operate past their stated completion date, despite there being no extension options in the contracts. While the contracts, and associated instructions, clearly outline the contracted deliverables:

- there have been significant variations made to each of the contracts, with insufficient documentation to evidence that each variation represented value for money to the Australian Government and the records of the variations are inadequate;

- there are deficiencies in the processes by which the department has engaged advisers and contracted the existing service providers to identify areas that could benefit from adaptation of new ideas and innovative service delivery to enhance client outcomes (referred to as innovative projects); and

- there is no probity plan for the management of the contracts, and inadequate departmental transition planning for the end of the contracts.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made five recommendations aimed at improved records of contract variations, better addressing value for money when considering variations to contracts, improving the process by which funding is awarded for innovative projects, development of a probity plan for the program and improved transition planning by the department.

2.1 The adoption of appropriate contractual arrangements is an essential underpinning to achieving the outcomes envisaged through a procurement process. The Department of Finance’s Contract Management Guide states that ‘the aim of contract management is to ensure that all parties meet their obligations to deliver the objectives of the contract’ such as ‘ensuring the goods or services purchased are provided on time, to the agreed standard, at the agreed location and for the agreed price’.

Do service provider contracts clearly outline contracted deliverables?

The service provider contracts, and associated Service Provider Instructions, clearly outlined the contracted deliverables.

2.2 The deeds of standings offers executed with each of the 13 general service providers includes a chapter outlining the specifics of the services; a chapter outlining the performance requirements and expectations; another chapter outlining the fees to be charged for each of the AMEP services; and a chapter specifying the contract regions (see footnote 11 and paragraph 3.13) the provider is to deliver the AMEP services.

2.3 The deeds of standing offers with each of the general service providers do not require the department to seek quotes from the providers before entering into a work order under the deed of standing offer. Instead, the standing offers allows the Commonwealth to issue work orders on demand.19 The deeds with each provider state that ‘The Contractor … irrevocably offers to provide the Commonwealth with the Services as and when the Commonwealth requires those Services’ and that the Contractor agrees to provide the Services ‘for the Fees; within the Contract Regions; from the Sites; and on the conditions’ as set out in the deed.

2.4 The AMEP General Service Provider Instructions (SPIs) are intended ‘to support and clarify the delivery arrangements for the Adult Migrant English Program (AMEP) service providers’. The information in the SPIs usually go to the detail of operationalising the contract, such as providing details on how to enrol, how to use the IT system, what is to be included in reports, timeframes for enrolment and reports. The SPIs were in place from the start of contracts (1 July 2017) to 30 June 2022. Version 11 of the SPIs was released on 5 May 2023 (with an end date of 31 December 2024). As such no SPI was in place for 10 months.

2.5 No one document contains all the AMEP general service providers obligations. The SPIs note that they should be read in conjunction with ‘supplementary tier documents’, ‘your contract and any other relevant reference material issued by the department’. This lack of clarity in where the provider obligations may be recorded was partially addressed in the March 2021 update to the SPIs where the department specified that the SPIs provide ‘supplementary administrative advice and should be read in conjunction with your Deed of Agreement, Work Order, Administrative Advice and all other relevant advice and/or reference material issued by the Department from time to time.’ It is standard practice in the administration of the AMEP for the department to issue correspondence, Communiques and Administrative Advices via email to all providers, or upload to a shared secure site for providers to locate.20

2.6 The version control sections across the 11 versions of the SPIs (most recent update was made in May 2023) note that updates often incorporate changes made to the administration of the program through communication with providers (through Administrative Advices, Communiques and correspondence). Similarly, some variations executed to the deeds of standing offer are made to incorporate changes made to the General Service Provider Instructions.

2.7 The Department of Finance’s Contract Management Guide, notes in section 2.3, that some communications with suppliers ‘can result in a variation of the contract or a waiving of your entity’s rights under the contract’ and recommends that the entity keep ‘note of discussions or agreements and email these to the supplier to avoid uncertainty regarding the discussion, minimise the risk of dispute and ensure you both have a record’. The department only commenced maintaining a register21 of such communications in 2020.22

Were variations to the contracts appropriate, including adequately demonstrating value for money?

Significant variations have been made to each of the contracts since they were signed such that the terms and conditions are now different in important respects from the procurement opportunity that was presented to the market. The department has not kept adequate records of the contract variations that have occurred. Department of Home Affairs’ (Home Affairs) records of decisions to vary the contracts do not adequately address value for money considerations and therefore do not demonstrate that each of the variations has been appropriate.

2.8 The contracts resulted from a combined procurement process for the AMEP and Skills for Education and Employment Program (SEE) programs.23 The contracts with the general service providers, as well as the contract with the quality assurance provider, include separate parts specific to each program, as well as parts that apply to both programs.

Extent of variations

2.9 The Department of Finance’s Contract Management Guide advises that:

- ‘The variation process you should follow is usually in the contract’ and that the administering department should ‘document the variation in writing and ensure both parties sign as evidence of agreement to the change (usually through a Deed of Variation)’; and

- the administering department should have, for longer term or more complex contracts, a ‘master version’ of the contract that includes all variations in track changes.

2.10 The extent to which the contracts are varied can indicate that a contract does not provide an appropriate basis for the management and delivery of a program.

2.11 The first AMEP variation was approved in December 2017, less than six months into the contract term, with a total of seven variations (usually referred to as variation numbers two, three, five, nine, 10 and 11) made to clauses that impact on delivery of AMEP. In proceeding with the variation approved in December 2017, the department recorded in April 2018 that:

Since the commencement of the new AMEP contracts on 1 July 2017, the department and the service providers identified contractual inconsistencies, practical problems implementing the new business model and difficulties managing program with the administratively burdensome contingency IT system.

2.12 In addition to the variations specific to AMEP for all service providers, four service providers have had specific variations made to their contracts, as follows:

- in December 2018, a provider’s contract was varied24to incorporate an additional contract region25;

- in June 2022, the contract for one provider (and three previous deeds of variation) was varied26 to change the Australian Business Number to the correct number;

- in July 2023, the contract for one provider was varied to change the fees payable; and

- in December 2023, the contract for another provider was varied27 to change the fees payable.

2.13 Each of the service provider contracts has also been affected by a variation to the general contract terms (that apply to both AMEP and SEE) and a variation to extend the duration of each contract. These variations were undertaken by the department that administers the SEE program.

2.14 The contract with the AMEP quality assurance provider has been similarly subject to numerous variations, with ten deeds of variations executed. Of note:

- Deed of Variation 2 from April 2018 could not be located in departmental records28;

- an ‘in principle agreement’ to vary fees was effected29 via a letter of offer and acceptance, not through a deed of variation;

- two variations30 are titled ‘Deed of Variation 6’, one being executed in February 2021 and another in December 2021 (Deed of Variation 7 was executed earlier in December 2021); and

- Deed of Variation 9 (which was actually the tenth variation) from July 202331 states it is only amending the SEE Part yet varies Part 1 of the whole agreement which impacts both programs.

2.15 Home Affairs has not maintained adequate records of variations to the contracts. For example, in December 2020 (Deed of Variation 4) all contracts for the general service providers were varied to adjust the fees for the providers. Prior to this variation, fees had been varied for four service providers through correspondence and so not reflected as variations in each contract’s variation schedule. These variations through correspondence are not recorded in a contract register, and there is no central repository of them. Some of the fee increases were agreed to through correspondence by the department because of the financial situation of the provider, without the department examining the implications in terms of the competitive procurement process that had concluded that the contractor offered the best value for money for particular contract regions. For example:

- a general service provider was party to two variations specific to its contract:

- On 28 June 2019, the department agreed through correspondence to increase the fees for the provider effective from 1 January 2019, including backdating fees for a six-month period.32 The reason the provider sought an increase was due to the implementation of a new enterprise agreement for its staff as of 1 May 2018. The department decided to increase the fee as the ‘change to the [enterprise agreement] was unforeseen, outside [the provider’s] contract and is real in terms of the impact on their organisation and their sub-contractors. The [enterprise agreement] was not in place at the time [the provider] tendered to deliver the AMEP and the SEE program.’

- In December 2019, the same provider again requested a fee increase for financial years 2020–21 and 2021–22. The request was reiterated on 24 June 2020. The justification for the fee increase was the same as previously, ‘unanticipated costs’ related to staffing.33

- in December 2018 the department agreed through correspondence to increase the child care fee paid34 to a different general service provider, and backdate payment of the child care administrative fee to 1 July 2018.35 The provider had advised the department that its ‘new child care model, which commenced on 1 July 2017, was not working well and [the provider] could no longer support the losses associated with the program.’ The agreement through correspondence was to cease on 30 June 2020.36 The Quarter 1 Invoice for the 2020–21 financial year for this provider continued the varied child care administration fee, despite the agreement ceasing, and applied the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Wage Price Index to the unit fee, increasing the fee for the 2020–21 financial year.37 In December 2020, a deed of variation was executed38 reestablishing the fee schedules for all providers.

- in July 2018, a different general service provider sought an increase to its fees for the 2018–19 financial year to ‘cover ongoing administration costs associated with the increase in AMEP expenses’. Some seven months later, in February 2019, the department agreed through correspondence to increase fees and for this to be backdated to 1 July 2018. This higher rate was to expire on 30 June 2020.39 In 2019 the department recorded that this fee increase stemmed from ‘concerns about the financial viability of the small service provider delivering in regional and remote contract regions and the administrative burden of delivering the AMEP, which was not well quantified at the time of the tender’40 For the 2019–20 financial year, the fees agreed through correspondence were indexed, and increased by the ABS Wage Price Index of 2.3 per cent. Despite the agreed fees expiring on 30 June 2020, for the Quarter 1 invoices for the 2020–21 financial year, the department41 continued to apply the fees agreed through correspondence with a further index applied. In December 2020, a deed of variation was executed42 reestablishing the fee schedules for all providers, and incorporated this expired fee (index annually) in the varied fee schedule.

- in April 2018 the department agreed through correspondence to increase all fees43 for another provider in one of its allocated contract regions, including backdating payments for the revised fees to July 2017, as student participation numbers were lower than the provider anticipated, threatening its ability to continue to deliver services. A further agreement was made for the 2018–19 financial year44, and again in June 2019 for the 2019–20 financial year.45 There is no evidence of agreement for the 2020–21 financial year.46 For the Quarter 1 invoice for the 2020–21 financial year, the department had continued to apply the child care administration fee and supplementary program administration fee as agreed in the correspondence (and indexed each year) despite the agreement for these fee increases expiring. In December 2020, a deed of variation was executed47 reestablishing the fee schedules for all providers.

2.16 In February 2024 the department advised ANAO that it ‘does not agree’ that Home Affairs has not maintained adequate records, rather that ‘it maintains a record of the variation that is complete to the best of its knowledge’48, and that ‘the record may not encompass all variations, particularly those undertaken via correspondence, prior to Machinery of Government changes.’ ANAO notes that such limitations to the records means that they are not adequate.

2.17 The extent to which the contracts with the general service providers have been varied indicates that those contracts did not provide an appropriate basis for the management and delivery of the program.

Recommendation no.1

2.18 To meet its record keeping obligations and ensure appropriate performance management of contracts, the Department of Home Affairs develop a complete record of all contract variations, including those variations agreed through correspondence, together with a master version of the contracts that incorporates all variations.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

2.19 The Department will continue to update the contract variation register and master contract to ensure all variations identified prior to machinery of government changes, effected by correspondence, have been recorded.

Linda Wyse and Associates response: Agreed.

2.20 LWA respects the need for contract record-keeping management and the need to ensure that contracted and performed activities align. LWA is committed to working closely with the Department to ensure the quality assurance contract is managed according to the Department of Finance’s Contract Management Guide.

Considering value for money

2.21 The Department of Finance’s Contract Management Guide advises that ‘an entity should not seek or allow a contract variation where it would amount to a significant change to the contract or significantly vary the scope of the contract’ if ‘other potential suppliers may have responded differently to an amended contract scope … which may have produced a different value for money outcome’ or if it would ‘compromise the original procurement’s value for money assessment.’

2.22 Home Affairs’ records of each of the decisions to vary the contracts do not clearly record that value for money was considered and therefore do not demonstrate that each of the variations has been appropriate.

2.23 For example, the first variation to the general service provider contracts (see paragraph 2.10) added services additional to those included in the approach to the market that resulted in the contracts being signed. Specifically, as recorded by the department, the ‘original contract did not make provision for Innovative Projects’ with Home Affairs advising the ANAO in April 2024 that this was a ‘drafting oversight’ at the time the tender was conducted. The contracts were varied to include a provision allowing for the conduct of select tender procurement processes for the delivery of additional services (‘innovative projects’). As of February 2024, ANAO has identified 53 innovative projects in departmental records (see paragraphs 2.35 to 2.42, Figure 2.1 and paragraphs 4.65 to 4.67) for a total budgeted cost of $5.94 million (excluding GST).

2.24 Other significant changes made in that variation related to:

- changes to the contracted key performance indicators (see paragraphs 3.11 to 3.19);

- changing the frequency of reporting from quarterly to six-monthly;

- allowing providers to seek exemptions from the department to engage teachers who do not meet the qualifications specified in the contract;

- changing the way child care travel payments were to be calculated and paid (to be formula based rather than based on records submitted by providers); and

- elevating from the General Service Provider Instructions to the contract provision for ‘blended’ classes (where providers with low student numbers may have students from both the pre-employment and social AMEP streams in the same class). This change was made on the advice of the department’s legal team which noted that ‘it is more appropriate to have the provider’s obligations set out on the face of the Contract rather than in the SPIs [Service Provider Instructions]’.

2.25 The brief to the approval delegate within the department did not discuss value for money implications of each of these changes either individually or in totality.

2.26 Another example related to changes made in July 2020, to come into effect in April 2020 (three months before the approval) in response to changes to support virtual tuition modes where face-to-face tuition was not possible due to the COVID-19 pandemic and social distancing measures. The changes included:

- detailing new services (being two new modes of tuition);

- agreement to a ‘One Off Transitional Cost’;

- development and implementation of ‘strategies to encourage adoption of Virtual Participation’;

- development and implementation of ‘a strategy that allows for AMEP clients to engage in a variety of ways most suitable to their circumstances’; and

- ‘Surveying other means of participation with AMEP Clients to determine their existing IT capability’.

2.27 While the department’s approval briefing for the changes discussed various ‘issues’, it did not explicitly address whether the changes (already in place for three months, see paragraph 1.4) represented value for money. The brief sought approval ‘to minimise the risk of 2019–20 program expenditure’ (see Appendix 5 paragraphs 10–12) being ‘recorded against the 2020–21 budget’ and:

A key consideration for desired outcomes is the Departmental budget for the AMEP. The budget model for the program is demand driven and normally increases and decreases according to the number of eligible visas granted. Under normal circumstances the reduction in arrivals from the closure of the Australian border on 15 March 2020 would have resulted in a proportional reduction in overall expenditure. However, the increased cost of delivery means that the reduced client inflow has been partially offset by the increased cost of delivery in the COVID-19 context.

2.28 The changes and associated fees were not incorporated into a deed of variation. Instead, the contract was varied to add a clause stating that Virtual Participation Fees ‘shall be set out in the AMEP SPIs and any applicable Work Order’. A work order was issued, which included a fee table, with fees specific to alternative tuition modes (see Appendix 5 paragraphs 10–12). The department’s approach to including and varying fees and services was inconsistent with the contract and also meant that, in a further contradiction of the contract terms, subordinate documentation, being the General Service Provider Instructions and work orders, was given priority over the contract deed (see Appendix 5 paragraphs 10–12).

2.29 Value for money was also not adequately addressed by Home Affairs in its decision making for the fourth deed of variation. This variation had two key impacts on fees. Firstly, adjusting the fees of all providers to incorporate variations made through correspondence49 (see paragraph 2.15), and secondly, the removal of the ‘supplementary program administration fee’ on 31 December 2020. This fee was agreed to be paid until a new information management system was introduced.50 When the administration of the AMEP program was moved to Department of Home Affairs in 2019, no new information management system had been introduced. Between 1 July 2017 and 30 June 2021, providers were paid $10.29 million in supplementary program administration fees. Neither the initial brief advising of the issue, nor the brief seeking execution of the deed of variation noted that all fees for all providers were also being varied to align with variations made through correspondence, and did not include a value for money assessment of the changes. Similarly, the department’s approval of an April 2021 variation did not adequately address value for money considerations. The variation was necessary as a result of legislative amendments that:

- removed ‘the 510 hour cap that currently limits free English tuition’ for AMEP students;

- raised ‘the AMEP eligibility threshold (and exit point from the program) from functional to vocational English; and

- removed ‘the time limit for registering, commencing and completing AMEP tuition (for those already in Australia as at 1 October 2020).’

2.30 The department’s variation approval briefing described these variations as ‘administrative only with no anticipated financial implications for the current contracts’. Inconsistent with this statement, removing the time limit on participation in the program (when providers are paid on hours of tuition) and extending the eligibility threshold from functional to vocational English can reasonably be expected to have financial implications.

Recommendation no.2

2.31 When considering potential contract variations for the Adult Migrant English Program, the Department of Home Affairs make a decision-making record that addresses whether the proposed changes represent value for money, including by reference to the value for money assessment that underpinned the procurement decision-making prior to the contract being awarded.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

2.32 The Department will improve decision making records for Adult Migrant English Program contract variations.

Linda Wyse and Associates response: Agreed.

Have contracted advisers on the program been appropriately engaged?

Contracted advisers have not been engaged through appropriate procurement processes. In addition to engaging advisers, the contracts with service providers were amended to enable the department to engage them to deliver ‘innovative projects’ that are additional to the services they were contracted to deliver at the conclusion of the 2017 procurement process.

2.33 The Department of Finance’s Contract Management Guide notes that specialist advisers, such as procurement specialists, technical and operational specialists, and legal advisers, may be used to assist with contract management activities. The Department of Home Affairs’ engagement of advisers to assist with AMEP is required to be consistent with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules, including employing procurement processes that encourage competition and demonstrate the achievement of value for money.

2.34 The CPRs also require that officials maintain appropriate records of the conduct of procurement processes. This includes records that outline the requirement for the procurement, the process that was followed, how value for money was considered and achieved and relevant decisions and the basis of those decisions. As outlined in Appendix 4, for the eight procurements examined by the ANAO:

- there was no competition for five procurements51 (63 per cent) despite the CPRs stating that encouraging competition is a key element of the Australian Government’s procurement framework, requiring non-discrimination and the use of competitive procurement processes; and

- value for money was not addressed in the record of the decision to spend public money for two procurements (25 per cent) despite the CPRs stating that achieving value for money is the ‘core rule’ of the CPRs (as it is critical to ensuring that public resources are used in the most efficient, effective, ethical and economic manner).

Innovative projects

2.35 The AMEP General Service Provider Instructions include ‘innovative projects’, which are projects to encourage AMEP service providers to ‘look beyond how you currently deliver AMEP services and what you do well, and identify areas that could benefit from adaptation of new ideas and innovative service delivery to enhance client outcomes’. As discussed at paragraph 2.23, the resulting contracts required amendment after being executed to provide for them.

2.36 The amendment to the contracts to permit the contracting of innovative projects set out various matters the department would specify when inviting a service provider to submit a proposal for an innovative project. Those matters included the timeframe for submitting a proposal, the nature of the services required for the innovative project and the delivery timeframe. The contract does not require the department to inform the service provider of the criteria that will be applied in deciding whether to accept any proposal that is received.

2.37 The AMEP General Service Provider Instructions advised providers that the department ‘may conduct funding rounds at least once per financial year’ and projects may be initiated in two ways: open submission from the panel of AMEP providers; and requests for quotation on specific projects identified by the department. Work orders were issued to 10 of the 14 providers to undertake the 56 innovative projects identified by the ANAO from departmental records (see Figure 2.1), for a total budgeted cost of $9.52 million (excluding GST). Innovative project rounds were open to all providers. Not all providers submitted proposals in all years.

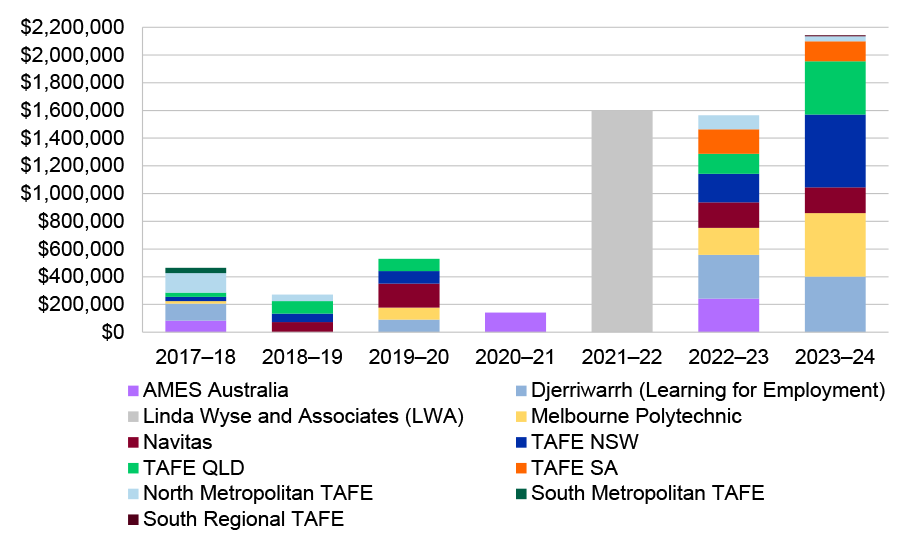

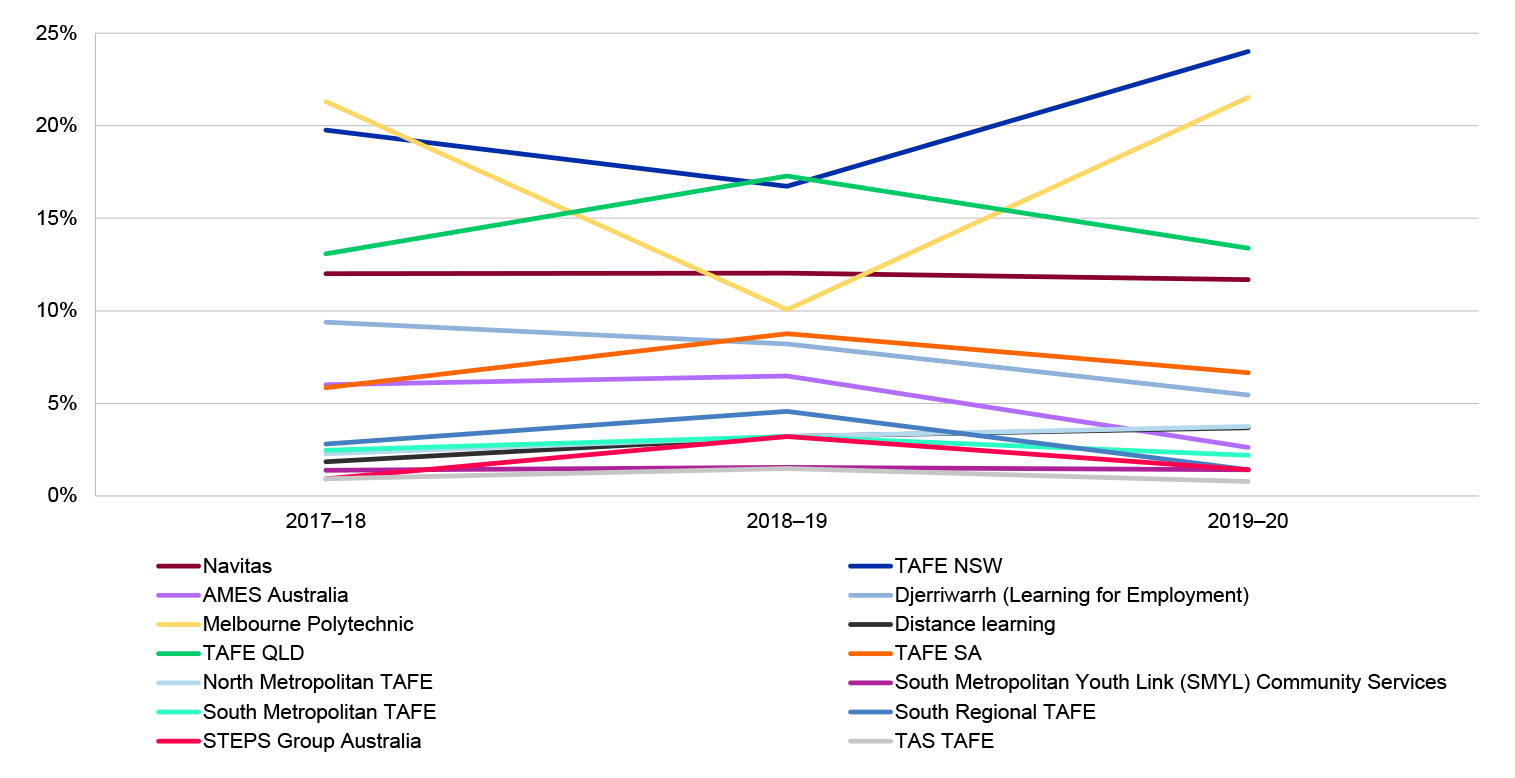

Figure 2.1: Distribution and value of innovative projects as at April 2024

Note: Three projects from 2019–20 were varied to extend the life of the project into 2020–21. One further project is yet to be approved for the 2023–24 year, with costs not included in this figure.

Source: ANAO analysis of Home Affairs records.

2.38 Initially, a competitive approach was taken to awarding innovative projects funding, with all providers invited in April 2017 to submit proposals. Seven providers submitted ten proposals in the funding round, of which eight proposals (from seven providers) were successful.

2.39 The innovative projects guidelines released to the AMEP providers included a statement of requirements for the projects and ‘assessment criteria’ that amounted to minimum requirements for projects identified through competitive rounds. The guidelines did not include evaluation criteria for projects where the department asked one or more providers to quote. While initially intended that work orders would be executed with successful providers, once it became apparent to the department52 that the contracts did not provide for this, the 2017–18 innovative projects were implemented through separate contracts with each of the successful AMEP providers.

2.40 Subsequently, between May and June 2018, the main contracts with the AMEP providers were varied to include innovative projects. All subsequent innovative projects have been effected through work orders under those contracts.

2.41 After the variations to contracts innovative projects were selected through the ‘request for quote’ process, with the department providing ‘themes’ and all AMEP providers given the opportunity to submit quotes for proposed projects. Not all providers responded to all requests, with an average of seven providers responding with an average of 12 proposals each year.53

2.42 The requests for quotes did not include evaluation criteria, or weightings against the statement of requirements. The requests for quotes did not included information on how the department would evaluate quotes against each other and assess value for money. An evaluation plan was established for the 2023–24 innovative project round, and records the assessment scores awarded to each proposal against five unweighted criteria and determined value for money rankings for projects based firstly on assessed score (highest to lowest total value), followed by assessed risk (lowest risk preferred) followed by value of project. This was also the first time conflict of interest declarations were made by the assessment team.

Recommendation no.3

2.43 The Department of Home Affairs introduce stronger governance arrangements over the process by which it engages service providers under the Adult Migrant English Program to identify areas that could benefit from adaptation of new ideas and innovative service delivery to enhance client outcomes including opportunities to offer these opportunities to open competition.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

2.44 The department has commenced implementing this recommendation, and notes the ANAO has recognised improvements made to the governance arrangements for Innovative Projects within the Report

2.45 With respect to the current Agreement, seeking proposals for Innovative Projects from existing providers is consistent with the intent of the panel approach, and the opportunity presented to the market in the establishment of the Panel. The department will consider opportunities to offer innovative projects to open competition, where practical.

Linda Wyse and Associates response: Agreed.

2.46 LWA acknowledges that extending these opportunities to open competition may further invigorate service delivery.

Have appropriate probity arrangements been effectively implemented?

There is no probity plan for the management of the AMEP contracts. As a result, there are no conflict of interest declaration and other probity risk management requirements in place for the AMEP contracts.

2.47 The Department of Finance’s Contract Management Guide identifies that, in addition to an overarching contract management plan, entities should consider developing a probity plan that ‘details the mechanisms for assuring probity within the management of the contract’. This guidance recognises that it is important that entity’s address probity risks during the management of contracts, and not only during the procurement process that results in the contract. The Guide identifies ethical considerations that need to be kept in mind during the management of contracts, including in relation to conflicts of interest:

As a contract manager, you should ensure all individuals materially involved with the management of a contract make a conflict of interest declaration and update it on a regular basis, particularly for longer term contracts.

2.48 Probity considerations are not addressed in the department’s contract management plan for AMEP, apart from identifying that advice on probity (and other) matters can be obtained from the department’s Civil, Commercial and Employment Law Branch and that probity risks will need to be managed as part of the transition to replacement contracts. For example, there is no requirement for those individuals materially involved with the management of the contract to make, and keep updated, conflict of interest declarations. The department does not maintain a register of any conflicts of interests that have been identified, or how they have been managed. The absence of a probity plan also means that, for example, there are not arrangements in place to address probity risks relating to:

- variations to the contracts, including where the variations mean the contract terms and conditions differ from the procurement opportunity that was presented to the market (see paragraphs 2.10, 2.24, 2.26, 2.29 to 2.30);

- ‘innovative projects’ (see paragraph 2.23);

- changes being made to the key performance indicators for the general service providers (see paragraphs 3.11 to 3.19); or

- the change in the nature of the services being requested from the contracted quality assurance provider54 such that the focus of the work is no longer consistent with the approach to the market (see paragraph 2.14).

2.49 In May 2022, the department adopted a probity plan that applies to consultations with stakeholders for planned program reforms, and the procurement process for replacement AMEP contracts. This probity plan does not apply to the management of the AMEP contracts under which services have been provided since 1 July 2017.

Recommendation no.4

2.50 The Department of Home Affairs develop a probity plan to govern the management of contracts for the Adult Migrant English Program.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

2.51 The department will establish a Probity Plan for the management of the existing and future contracts for the Adult Migrant English Program.

Linda Wyse and Associates response: Agreed.

2.52 LWA appreciates the importance of probity and its impact on contract management. LWA Conflict of Interest Plans, updated annually and used to inform quality assurance activities, are available to ensure quality assurance activities adhere to the developed probity plan.

Is an appropriate transition management plan in place?

Appropriate transition management plans are not in place. The contracts were due to end on 30 June 2023 and did not include any extension options yet, due to delays with the procurement process to replace them, they are continuing to operate past the stated completion date. As of December 2023, the department had not finalised and approved a transition out plan for the existing contracts, notwithstanding that those contracts were originally due to expire in June 2023 (they are now due to expire on 30 June 2024, with work orders under the contracts due to expire on 31 December 2024). Further, the draft transition in plan is substantively incomplete, reflecting the uncertainty about the future contractual arrangements (the tender process for replacement contracts has been subject to delays).

2.53 The transition from the prior contracts to the current AMEP general service provider contracts that commenced on 1 July 2017 was not well planned and executed. This was reflected in complaints from some general service providers and stakeholders. One provider made a request for compensation, and later sought (and was awarded) increases to its contracted fee, with the lack of student numbers cited as a key reason.

2.54 The contracts include a ‘completion’ date which according to the terms of the agreement is the date the agreement ends (unless terminated earlier). At the time the contracts were signed, this date was 30 June 2023.

2.55 Section 2.13 of the Department of Finance’s Contract Management Guide state that departments can only extend a contract if three conditions are met: the contract has an unused option to extend the contract; it is value for money to extend the contract; and the contract has not yet expired. The AMEP contract does not have a clause providing an option to extend the contract for any addition or set period of time.

2.56 Notwithstanding this situation, in December 2022, all contracts were varied to adjust the ‘completion’ date from 30 June 2023 to 30 June 2024. Essentially, this extended the contract period for a year despite the contract not having an option to extend. In December 2022, the planned request for tender for new contracts was under design and development, and had not yet been opened to the market.

2.57 As part of the December 2022 variation, the clause specifying when a work order made under the contract would cease was also changed. Originally the clause stated that each work order would end on a date specified in the work order or on the contract’s completion date. This was varied to state that the work order would ‘end on the end date specified in the Work Order, unless terminated earlier’ in accordance with the contract. This variation has the effect of allowing the work orders to continue on past the completion of the overarching contract.

2.58 On 30 November 2023, the Minister for Immigration, Citizenship and Multicultural Affairs approved a further delay55 to the planned approach to market for new contract arrangements for the AMEP program. The department advised the minister that:

New AMEP Work Orders would need to be put in place to extend arrangements with the current providers a further nine to twelve months. Current AMEP Work Orders are in place to 31 December 2024. These Work Orders sit under an Agreement that is owned by the Department of Workplace Relations (DEWR) which expires 30 June 2024. While new Work Orders can be entered into beyond the Agreement expiry date, any Work Orders must be in place before the Agreement expires and no further variations can be made after that date.

2.59 The department further advised that minister that:

The Agreement does not have any extension options. Extension may be possible through a Deed of Variation (DoV), but this is complex as responsibility for the Agreement sits with DEWR who conducted the approach to market in 2016 and manage the panel, which includes both AMEP and Skills for Education and Employment providers. Any DoV to extend the Agreement date would require consultation with DEWR and it is not clear if DEWR would support this process as they will have no ongoing need for the Agreement beyond 30 June 2024. It may be possible to seek transfer of the Agreement from DEWR to Home Affairs, but this would result in a large body of work for both departments and is therefore considered unlikely.

If the Agreement is not extended, it is possible to put Work Orders in place before the Agreement expires on 30 June 2024 which go beyond that date, as long as the need for services is justified. However, once the Agreement ceases, it is not possible to execute any new Work Orders. This will result in a loss of flexibility in managing the AMEP contracts, especially in undertaking any further Innovative Projects in relation to the Governments $20 million commitment to improving flexible delivery options and increasing case management support to clients in the AMEP. The Department will be able to incorporate Innovative Projects into ms before the expiry of the Agreement, but would need to seek further advice on the extent to which this is possible after the Agreement ceases.

With any DoV or Work Order process, consultation and negotiation would be required with each service provider.

2.60 The minister noted the risks associated with his decision.

Transition plan for end of AMEP contract

2.61 The contracts include ‘Transition-Out’ clauses, which outline the requirements of providers to support transition to new providers and new contract prior to the expiry of the ‘Agreement Period’. The contract defines ‘Agreement Period’ as ‘the period between the Commencement Date and the Completion Date’ (which is now 30 June 2024, although, as set out in paragraphs 2.57–2.60, work orders under the contracts are due to expire on 31 December 2024).

2.62 In terms of the department’s preparation for transitioning to new contracts, as at December 2023, Home Affairs:

- did not have a transition out plan prepared and approved. Drafting of a transition out plan commenced in April 2022, and the department decided in June 2022 to contract Callida at a cost of $250,000 to ‘create and implement a transition-out plan which will detail the processes and activities required to be carried out to ensure a seamless transition of supplier services prior to the expiry of existing AMEP agreements’.56 The most recent version of this draft dated November 2023. The document is not complete, has not been considered by the department’s Transition Working Group and has not been approved; and

- preparation of a transition in plan commenced in April 2023, and there have been no further draft versions prepared. Reflecting the significant uncertainty around the delayed procurement process to replace the AMEP contracts, the transition in plan is substantively incomplete. In February 2024, Home Affairs advised the ANAO that:

The department will continue to progress the development and approval of the Transition In Project Plan following finalisation of the new AMEP business model settings and contractual arrangements. As the Transition In Project Plan is a live document, it will continue to be regularly reviewed and updated over the life of the project, including following approval of the detailed transition in plans submitted by the preferred tenderer/s.

2.63 In February 2024 the department advised the ANAO that it ‘is considering options’ to ‘rectify any timeframe issues in relation to transition out clauses, to mitigate against any potential future risk where Work Orders may extend beyond the Completion Date.’ Further extending the completion date of the contract past 30 June 2024 would be inconsistent with Section 2.13 of the Department of Finance’s Contract Management Guide (see paragraph 2.55) which states that entities can only extend a contract if three conditions are met: the contract has an unused option to extend the contract; its value for money to extend the contract; and the contract has not yet expired. The AMEP contract does not have a clause providing an option to extend the contract for any additional or set period of time.

Recommendation no.5

2.64 The Department of Home Affairs improve its transition planning for the Adult Migrant English Program by:

- finalising the transition out plan for the current contracts and, for future contracts, preparing the transition out plan early in the new contract period; and

- aligning the development of the transition in plan for the replacement contracts with the preparation of the approach to market documentation.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

2.65 The department will finalise the drafting and approval of its Transition Out Project Plan in accordance with the department’s established Contract Management Framework.

2.66 The department will continue to align the further development of the Transition In Project Plan for the future contract/s with the preparation of the approach to market documentation.

Linda Wyse and Associates response: Agreed.

3. Service provider contract management

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether the Department of Home Affairs (Home Affairs) is appropriately managing the general service provider contracts.

Conclusion

The general service provider contracts have not been appropriately managed. A comprehensive set of contracted performance indicators was in place when the contracts were first signed, but that framework has been amended over time such that it no longer addresses the educational outcomes being achieved by students, the accuracy of provider assessments of student educational outcomes or the timeliness of service provider provision of data to the department. The only indicator that has remained relates to the extent to which eligible students commence in the program. In addition:

- invoice verification processes have not been sufficiently robust; and

- the department has not implemented a previously agreed recommendation that it would use complaints data from providers to inform and improve service delivery for students.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at improving the contracted framework for service provider performance and analysing complaints data from the general service providers so as to inform and improve service delivery to students.

3.1 The aim of contract management is to ensure that parties meet their obligations such that deliverables are provided to the required quantity and standard and within the specified timeframes such that value for money is achieved. The Department of Finance’s Contract Management Guide states that it ‘is important that contracts are managed consistently and actively throughout their life in accordance with their terms’ as this ‘will ensure that supplier performance is satisfactory, stakeholders are well informed, and all contract requirements are met thereby ensuring that the contract delivers the anticipated value for money.’

Is contract information accurately recorded and stored by the department?