Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of the Access to Allied Psychological Services Program

To examine the effectiveness of the Department of Health and Ageing’s administration of the Access to Allied Psychological Services Program.

Summary

Introduction

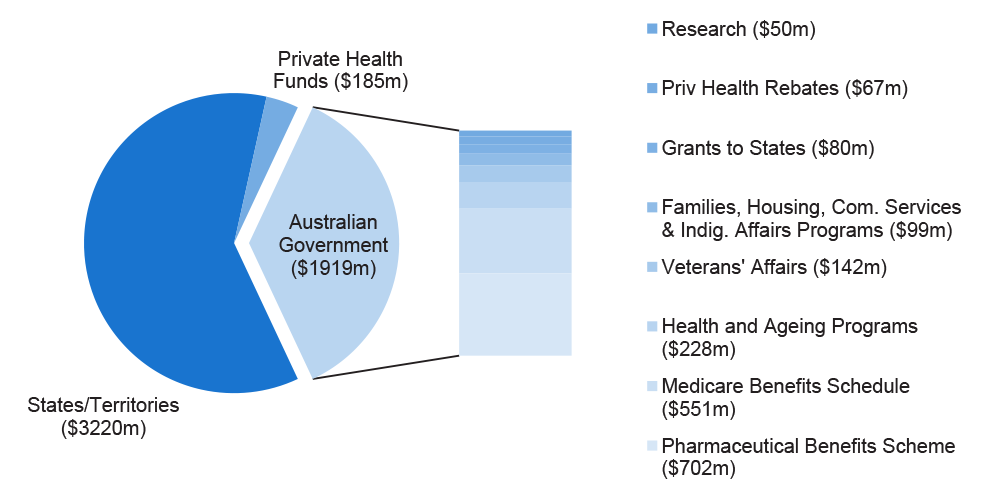

1. Almost one in two Australians aged 16 to 85 years has experienced a mental health disorder at some point in their life, with anxiety, depression and/or alcohol dependence the most common.[1] In 2008, Australian governments spent $5.1 billion on mental health (see Figure S.1 for the distribution of total recurrent funding on mental health by major funders), which represents 7.5 per cent of total government health spending.[2]

Figure S.1: Distribution of recurrent spending on mental health (2007–08)

Source: ANAO from the National Mental Health Report 2010.

2. The impact of mental illness can be profound, with the Mental Health Council of Australia reporting that affected individuals and their carers constitute one of the most disadvantaged and marginalised groups in terms of access to services and complexity of issues. They frequently experience financial hardship, housing issues and homelessness, unemployment or underemployment, alcohol and other drug use, and related physical health complaints.[3]

3. Access to treatment remains problematic for many Australians with a mental health disorder. It is estimated that over half the Australians with a mental illness do not access support services. The level of access has gradually improved since 2007, with the improvement attributed primarily to the introduction of additional government funded mental health care programs.[4]

4. The Department of Health and Ageing (DoHA) is the lead agency responsible for advising on, implementing and managing Australian Government mental health care policies and measures. Initiatives and programs administered by DoHA are varied and range from Medicare-based universal mental health programs through to programs designed to provide flexible mental health care services that target hard to reach groups less likely to access Medicare-based services. An example of the latter program type is the Access to Allied Psychological Services (ATAPS) Program.

Access to Allied Psychological Services Program

5. The ATAPS program, which had its origin in a 2001–02 Budget measure, has a current budget of approximately $43 million per year. It is the Australian Government’s primary mechanism to address historically poor access to mental health care for specific groups in society, such as people in remote locations including Indigenous communities, youth and the homeless. The program enables General Practitioners (GPs) to refer patients diagnosed as having a mental disorder to an allied mental health professional[5] for a capped number of sessions of focused psychological strategies[6] at low or no cost. Since 2001–02, over $150 million has been budgeted for the ATAPS program. As part of the 2011–12 Federal Budget, the Government announced a $2.2 billion National Mental Health Reform package[7], which included an increase of $206 million over the next five years to double the size of the ATAPS program.

6. The program is administered by a small team within DoHA’s Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Branch, which has responsibility for program design, planning, implementation, oversight, and reporting to the Minister and the Parliament. The responsibility for day-to-day delivery of the program rests with the Divisions of General Practice (Divisions), which cover defined geographic areas. Divisions act as fund holders and are allocated an annual budget to broker allied mental health services for consumers referred by GPs.[8] Divisions are afforded flexibility by DoHA to tailor service delivery to suit local circumstances and establish an appropriate system to manage local demand for services within the capped annual budget. Over recent years, these flexible delivery arrangements have been increasingly called upon to deliver the Australian Government’s response to the increase in mental health care needs following significant natural disasters, such as the 2009 Victorian bushfires and the 2011 flood and cyclone emergencies in Queensland.

7. Responsibility for day-to-day delivery of the ATAPS program will transition from Divisions to Medicare Locals from mid-2011. Medicare Locals, which are a key component of the Australian Government’s National Health Reforms, will be primary health care organisations established to coordinate primary health care delivery to address local health care needs and service gaps.

8. In February 2010, DoHA released a departmental review of the ATAPS program—conducted with oversight from an Expert Advisory Committee—which focused on the outcomes of the program as well as future directions.[9] The department is currently working to implement the areas of enhancement recommended by the review, while also responding to the expansion of the program as a result of substantial new Budget measures over recent years.

Audit objective and scope

9. To examine the effectiveness of the Department of Health and Ageing’s administration of the Access to Allied Psychological Services Program.

10. The focus of the audit was on DoHA’s administration of the ATAPS program, including systems and processes that the department employs to: guide its administrative efforts; manage day-to-day delivery of the program through a large number of third-party providers; plan and administer program initiatives; monitor compliance with program requirements; and report on the extent to which the program is achieving the objectives set by government.

Overall conclusion

11. The ATAPS program, with current annual funding of around $43 million, is a key Australian Government initiative designed to improve access to mental health care, with an increasing focus in recent years on those groups with historically poor access and with low usage of ‘mainstream’ Medicare-funded services. Since commencing in 2002, the ATAPS program has facilitated greater consumer access, at low or no cost, to Australian Government subsidised treatment in a primary care setting for people experiencing high prevalence mental health disorders, such as depression and anxiety disorders. As at March 2011, more than 900 000 mental health sessions of care had been recorded under the ATAPS program to around 170 000 people with a diagnosed mental health disorder.

12. Although considered a mature program, ATAPS is at a point of transition, with policy and administrative challenges arising from: a substantial increase in program funding announced in the 2011–12 Budget; the refocusing and targeting of the program following a review released in early 2010 to better complement larger mainstream programs; the implementation of four new ATAPS measures from the 2010–11 Budget; the proposed transfer of responsibility for day-to-day administration from Divisions of General Practice to Medicare Locals; and the implications of broader reforms to the health care system in Australia.

13. The day-to-day administration of the ATAPS program also presents challenges, requiring departmental engagement with a broad range of program stakeholders—often with competing views on program delivery priorities and approaches—and the oversight of over 100 organisations contracted to implement the program on the Australian Government’s behalf. The topical nature of mental health care policy and the clinical aspects of mental health care service delivery also contribute to the challenges facing DoHA’s program administrators. Additionally, the expanded use of the ATAPS service delivery framework to respond to increases in demand for mental health care services following significant natural disasters has called for agility and responsiveness, which the department demonstrated when responding to the 2009 Victorian bushfires and when developing options to respond to the 2011 Queensland flood and cyclone emergencies.

14. While the ATAPS program is delivering valued services to those able to access mental health care under the capped program, the administrative arrangements established by DoHA have not consistently supported the achievement of program objectives. In particular, there has been variable administrative performance, over the relatively long life of the program, in relation to a number of important program elements including: the allocation of program funding on the basis of identified need; monitoring compliance with program requirements; and the administration of new ATAPS initiatives.

15. Achieving improvements in access to mental health care services for hard to reach groups is strongly influenced by the extent to which funding for service delivery is matched to those consumers experiencing the greatest need. The allocation of ATAPS funding to Divisions was initially determined using a population-based funding formula. This approach, which reflected the broad eligibility for the program at the time, has not kept pace with demographic changes or changes in the program, such as the increased targeting of services. As DoHA has not historically assessed mental health care needs within Division of General Practice boundaries or regions on a regular basis, or used such information to allocate ATAPS resources, some communities are not receiving an equitable share.

16. To help ensure that funded organisations deliver the program as intended by government and that eligible consumers receive the appropriate services to which they are entitled, it is necessary to establish clear program requirements. DoHA has established in its program guidelines a broad range of terms, conditions and rules for the delivery of ATAPS services, such as the number of services available to eligible consumers, while relying heavily on self-reporting from Divisions as a means of monitoring compliance. Self-assessment and reporting have inherent limitations with respect to the level of assurance they can provide, but the department has not adequately considered and documented alternatives, such as focusing on those providers presenting the greatest risk of non-compliance. A risk-based approach to monitoring compliance would enable the department to more effectively deploy its limited resources and to better identify, and if necessary treat, the risk of ATAPS not being used as specified in the program guidelines.

17. ATAPS has been used regularly as a platform to trial new and innovative service delivery methods with the potential to improve access to mental health care for hard to reach groups. ATAPS initiatives have included trials of telephone-based therapy to address barriers to access for rural and remote consumers and projects to provide greater support for GPs engaged in suicide prevention activities for at risk patients. While certain aspects of DoHA’s administration of ATAPS initiatives were well managed, in general, the department had not actively managed initiatives and taken timely corrective action to address identified delivery issues. Furthermore, the absence of success criteria, established at the commencement of each initiative, has meant that the basis on which the department assessed the success or otherwise of initiatives (as a prelude to incorporating them as elements of the core program) was unclear.

18. The work currently underway within DoHA to implement the areas of enhancement recommended by the ATAPS review provides the department with an opportunity to establish a foundation for future program design decisions and to address identified weaknesses in administration. To assist DoHA to strengthen its administration of the ATAPS program, particularly in light of the substantial expansion of the program announced in the 2011–12 Budget, the ANAO has made five recommendations directed at improving the way in which the department: allocates and manages program funding; supports program administrators; oversees consumer access and the approaches employed by funded organisations to manage demand; administers program initiatives; and monitors compliance with program requirements.

Key findings

Designing the program

19. The ATAPS program has evolved considerably over the 10 years since it was announced, particularly in response to the introduction of significant new mental health care programs. Most recently, the Government has decided that ATAPS will be complementary to larger mainstream programs through the targeting of hard to reach groups.

20. Across a number of areas, the department was not well placed to make informed program design decisions, primarily due to the lack of: retained information on funding approaches; a complete set of program guidance materials; or evidence on which policy decisions were based. Effectively recording the basis of program changes stemming from the recent review will assist DoHA to make informed decisions regarding future changes in the design of the program and mitigate the risk of program delivery decisions being inconsistent with the policy parameters set by government.

21. DoHA has outlined the key program delivery parameters in its operational guidelines, including: target groups; eligibility criteria; service providers; eligible services; and service delivery models. With the program currently in transition to a more targeted approach, it would be timely for the department to review key ATAPS design elements and guidance materials, including the program guidelines, to ensure that they adequately support the government’s new policy settings for the program. The capture of key design elements in an explicit ATAPS program objective, endorsed by government, would also serve to inform future changes to the design of the program, provide a focus for DoHA’s performance monitoring activities, and assist the department to convey the intent of the ATAPS program to stakeholders.

Allocating program funding and managing demand

22. As observed by the ATAPS review and as acknowledged by DoHA, ATAPS funding was originally intended to reflect a population-based funding formula, but there has been a drift away from this formula over time, with some communities with higher needs not receiving an equitable share of ATAPS resources. This view is supported by departmental modelling which indicates that, based on a proposed needs-based funding model, around 60 per cent of Divisions would receive more funding while 40 per cent of Divisions would receive less funding. The department has recognised that a move to reallocate program funding presents risks and requires careful management. To support the effective targeting of program funding to those with the greatest need, the department should provide options, for Ministerial consideration, that would allow the ATAPS program to transition to an appropriate needs-based funding model.

23. The use of demand management strategies, such as the establishment of waiting lists, represents a pragmatic response by Divisions to the delivery of mental health care services within a constrained funding envelope. However, some of the approaches adopted by Divisions have the potential to affect consumers seeking treatment, for example, by further limiting the number of treatments available to consumers within the thresholds set by DoHA for the program. There is scope for DoHA to assess the appropriateness of the demand management strategies employed by Divisions in order to support more consistent and equitable access to treatment for eligible consumers experiencing a mental health disorder.

Supporting program administrators

24. The administration of the ATAPS program is challenging, requiring engagement with a broad range of program stakeholders and the oversight of over 100 organisations contracted to implement the program on the Australian Government’s behalf. The effectiveness of program delivery within this environment is heavily dependent on the knowledge, skills and expertise of a small team of program administrators. In order to strengthen day-to-day management of the ATAPS program, there is scope for DoHA to enhance the support that is currently provided for program administrators through the provision of: tailored induction and training; fit-for-purpose policy and procedural materials; and a central record of key program decisions (particularly exemptions and funding levels).

Responding to natural disasters and administering initiatives

25. The ATAPS service delivery framework has been used as a vehicle by the Australian Government to respond to the increased need for mental health care services following natural disasters and to deliver mental health care initiatives.

26. DoHA’s oversight of the ATAPS mental health response to the 2009 Victorian bushfires was timely and well designed, with additional flexibilities afforded to Divisions to tailor approaches to local conditions. The department acted quickly to bring forward program payments and provide additional funding to enable Divisions to respond in a timely manner to emerging mental health care needs. The department also demonstrated agility in providing the Government with options to respond to the anticipated increase in mental health care needs following the recent floods across large parts of Queensland.

27. There were also aspects of DoHA’s administration of the three recent ATAPS initiatives—Telephone-based Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (T-CBT), Suicide Prevention, and Perinatal National Depression Initiative (PNDI)—that were well managed, such as the use of an international study and experience to inform the design of the T-CBT trial and the use of relevant data to target PNDI funding to areas of greatest need. However, in general, the department did not actively manage the delivery of initiatives and did not always take timely corrective action to address identified implementation issues. Furthermore, the absence of a set of clearly documented ‘success indicators’ for ATAPS initiatives made it more difficult for DoHA to effectively monitor the progress of the initiatives and, ultimately, to assess the success or otherwise of the initiatives before incorporating them as elements of the core program.

Monitoring compliance

28. A balanced approach to the monitoring of compliance with program requirements, involving a mix of education through to the targeted review of a small number of Divisions presenting the greatest risk of non-compliance, would provide DoHA with appropriate assurance while limiting resourcing requirements. The department’s current approach to monitoring Divisions’ compliance with program requirements relies heavily on self-reporting, complemented by the provision of annual audited financial statements. While the department’s use of reports from Divisions to monitor compliance is efficient from a departmental perspective, self-assessment has inherent limitations with respect to the level of assurance it provides on compliance with program requirements. In order to plan and coordinate its compliance activities, DoHA should establish a risk-based compliance approach to direct limited departmental resources to those providers presenting the greatest risk of non-compliance.

Evaluating program performance

29. The department’s focus on evaluation (involving the preparation of two to three evaluation reports each year) throughout the life of the ATAPS program is viewed by many stakeholders as a strength. It would be timely, given the passage of time since the program commenced and the changes to policy and administrative settings arising from the recent review, for the department to re-examine the evaluation needs of the ATAPS program in order to better determine the level and future focus of evaluation activity.

Summary of agency response

30. DoHA advised that the following summary comment and the responses to each of the recommendations in the body of the report comprised its formal response:

The Department of Health and Ageing (DoHA) welcomes the comprehensive audit of the Access to Allied Psychological Services (ATAPS) program—spanning the complete ten year history of the program—undertaken by the ANAO and agrees to all five recommendations. DoHA notes that the action recommended in Recommendation 1 was taken in 2010; many of the matters covered in the recommendations are currently being addressed; and implementation of the audit recommendations will further enhance the effectiveness of the administration of the program to continue to produce positive consumer outcomes for particularly disadvantaged Australians with mental illness.

The administrative arrangements put in place by DoHA have enabled ATAPS to become positioned, as the audit points out, as a targeted program that complements other primary care mental health programs, including services funded through Medicare. It has been shaped to become an agile and well respected program which is able to respond quickly and effectively to emerging needs such as disaster recovery and government policy objectives, particularly in better targeting hard to reach groups. The ongoing evaluation of the program has shown it has delivered effective, evidence based services which have improved mental health outcomes for people in hard to reach populations, within the allocated resources.

Footnotes

[1] National Advisory Council on Mental Health, 2009, Discussion Paper: A Mentally Healthy Future for all Australians, Canberra, p. 8. Available from: <http://www.health.gov.au> [accessed 22 December 2010].

[2] Department of Health and Ageing, 2010, National Mental Health Report 2010: Summary of 15 Years of Reform in Australia’s Mental Health Services Under the National Mental Health Strategy 1993–2008, Canberra, p. 2. Available from: <http://www.health.gov.au> [accessed 22 December 2010].

[3] Mental Health Council of Australia, 2011, ATAPS Flexible Care Packages for People with Severe Mental Illness Discussion Paper, Canberra, p. 1. Available from: <http://www.mhca.org.au> [accessed 2 May 2011].

[4] University of Melbourne, 2011, Final Report–Evaluation of the Better Access to Psychiatrists, Psychologists and General Practitioners Through the Medicare Benefits Schedule Initiative: Summative Evaluation, Melbourne, pp. 25–27. Available from: <http://www.health.gov.au> [accessed 6 April 2011].

[5] Under the ATAPS program, allied mental health professionals include psychologists, social workers, mental health nurses, occupational therapists and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers with specific mental health qualifications.

[6] The term ‘focused psychological strategies’ is defined in the 2010–11 ATAPS operational guidelines as the provision

of time-limited, evidence-based psychological treatments restricted to psycho-education, cognitive-behavioural therapy, relaxation strategies, skills training, interpersonal therapeutic strategies and narrative therapeutic strategy.

[7] This package included $1.5 billion over five years in new initiatives.

[8] Department of Health and Ageing, 2010, 2010–11 Guidelines for the Access to Allied Psychological Services Component of the Better Outcomes in Mental Health Care Program, Canberra, p. 3.

[9] The review proposed four key future directions around the themes of addressing service gaps, efficiency, innovation and quality.