Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of the Tariff Concession System

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service's administration of the Tariff Concession System.

Summary

Introduction

1. Customs duty and Commonwealth taxes are imposed on certain goods when they are imported into Australia, with the rate of duty payable determined by the tariff classification of the goods. Imposing duty on certain imported goods is designed to influence the flow of trade by regulating their value to protect Australia’s local economy and industry. There are, however, a number of ways that importers can obtain duty-free entry of imported goods into Australia, including through accessing free trade agreements1 and through the use of duty concession schemes, such as the Tariff Concession System (TCS).

Tariff Concession System

2. The TCS, which was established in its current form in 19922, is intended to assist Australian industry and to reduce costs to the general community where the imposition of a tariff serves no industry assistance purpose. That is, where no local manufacturer produces substitutable goods.3 The Department of Industry (Industry) is responsible for the policy framework underpinning the operation of the TCS, while the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service (Customs) is responsible for the administration of the system as part of its wider responsibilities for managing border risks.

3. To receive a duty concession under the TCS, an imported good must be covered by a current Tariff Concession Order (TCO). A TCO consists of a tariff classification and descriptive text, which together describe the good that is covered by the order. Once a TCO has been made by Customs, it is available for use by any importer that seeks to import goods that correspond to the description and tariff classification. In 2013–14, around $1.8 billion in revenue to the Commonwealth was forgone through the use of TCOs, with Customs estimating that the amount of revenue forgone will increase to around $1.9 billion in 2014–15.

Assessing a Tariff Concession Order application

4. The legislated process for assessing a TCO application involves two stages. The first stage assesses the validity of the application, with the details of a valid application published in the weekly Commonwealth of Australia Tariff Concessions Gazette (the Gazette), which facilitates any objections from local manufacturers. The second stage, which must occur between 50 and 150 days after notification of an application in the Gazette, requires Customs to determine whether a TCO will be made.

5. Customs’ decision as to whether or not to make a TCO is to be based on the information contained in the application and subsequent submissions from the applicant, any objections from local manufacturers to the proposed TCO and the results of any additional inquiries made by Customs.4 Once made, a TCO is available to all importers of the described goods unless it is revoked. In 2013–14, Customs received 941 TCO applications, 133 objections and made 770 TCOs (see Table S.1. for further details).

Table S.1: TCO applications (2012–13 and 2013–14)

|

Application Actions |

Number (1) |

|

|

Initial Stage (prior to gazettal) |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

|

Applications received |

998 |

941 |

|

Applications rejected |

99 |

36 |

|

Applications withdrawn |

118 |

96 |

|

Approval Stage (after gazettal) |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

|

Objections received |

88 |

133 |

|

TCOs made |

762 |

770 |

|

TCOs refused |

43 |

79 |

Source: ANAO analysis of Customs information.

Note 1: There is a lag of up to 150 days between the gazettal of an application and making a decision. As a result, the number of applications and decisions do not align within a 12-month period.

Revoking a Tariff Concession Order

6. There are a number of circumstances under which a TCO may be revoked, either at the initiation of a local manufacturer or the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of Customs. A local manufacturer initiated revocation places the onus on the applicant to demonstrate why a TCO should be revoked by providing evidence of the local manufacture of a substitutable good. Once an application for revocation has been lodged, a decision is made by Customs based on the information provided in the request and any further inquiries undertaken. Where Customs decides that the TCO should be revoked, the revocation takes effect from the date that the request for revocation was received, not the date of the decision. In 2013–14, Customs received 45 applications from local manufacturers for the revocation of a TCO, with 43 of these being upheld.

Managing Tariff Concession Order compliance

7. Managing importer compliance with TCO requirements underpins the effective operation of the TCS, supports Australian manufacturers through the proper implementation of the tariff, and helps to ensure the correct collection of customs duty. The primary risk related to the TCS is the misapplication of a duty concession to goods that do not adhere to the nominated TCO descriptions.

8. Prior to 1 July 2014, Customs’ Compliance Assurance Branch (CAB) was responsible for enforcing compliance with TCS requirements. CAB adopted an ‘intelligence-led, risk-based’ approach to managing compliance risks. Where a risk had been identified, it was rated and treated according to the level of risk it represented and the resources available at the time. From 1 July 2014, enforcement action relating to economic risks—the risk most relevant to the TCS—became the responsibility of the newly formed Strategic Border Command Division within Customs. Within Strategic Border Command, Customs has created a Revenue and Trade Crime Task Force with responsibility for coordinating a number of compliance activities5, including enhancing Customs’ revenue collection at the border.6 It is intended that responsibility for managing enforcement action will move to the newly established Australian Border Force, which will be established as a border agency within the Department of Immigration and Border Protection by 1 July 2015.7

Audit objective and criteria

9. The objective of the audit was to assess the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service’s administration of the Tariff Concession System.

10. To form a conclusion against the objective, the audit adopted the following high-level criteria:

- an appropriate governance framework to support the effective operation of the system was established;

- a consistent, accountable and transparent assessment process for TCO applications has been implemented;

- processes and systems for the ongoing management, review and eventual revocation of TCOs are effective; and

- the approach to managing compliance with TCO requirements was sound.

Overall conclusion

11. Imposing duty on certain imported goods is designed to influence the flow of trade by regulating their value to protect Australia’s local economy and industry. In 2013–14, goods to the value of $338 billion were imported into Australia, with $9.3 billion in customs duty collected. There are, however, a number of ways that importers can obtain duty-free entry of imported goods to Australia, including through accessing duty concession schemes, such as the Tariff Concession System (TCS). To receive a duty concession under the TCS, an imported good must be covered by a current Tariff Concession Order (TCO) made by Customs. A TCO consists of a tariff classification and text describing the good. As at October 2014, there were over 15 000 current TCOs available for use by importers. Under the TCS, around $1.8 billion in revenue to the Commonwealth was forgone in 2013–14.

12. Customs is responsible for administering the TCS, including assessing TCO applications, objections and revocations. In 2013–14, Customs received 941 applications for, and 133 objections to, TCO applications, made 770 TCOs, refused 79 TCOs and revoked 327 TCOs. Customs is also responsible for managing compliance with TCS requirements and providing assurance that importers applying a TCO to reduce customs duty are eligible to do so.

13. The TCS is supported by mature administrative arrangements that provide a generally sound basis for the assessment and management of TCOs, including the processing of TCO applications, objections, revocations, as well as the management of TCOs that are in use. There are, however, aspects of Customs’ administrative arrangements that could be further improved, including by:

- developing a communications strategy for the TCS to maximise the effectiveness of communications and awareness raising activities, with a particular focus on local manufacturer engagement; and

- more clearly documenting TCO application assessment activities, in particular the basis on which applications are assessed as meeting legislative requirements, to provide greater assurance regarding the integrity of the assessment and decision-making process.

14. Within the context of Customs’ broader compliance responsibilities, the limited resources assigned to TCS compliance are allocated on a risk basis and, overall, the small number of targeted compliance activities undertaken has identified TCO misuse. Nevertheless, Customs is not well placed to determine whether its activities directed at managing TCS compliance, including education and awareness activities through to enforcement action, are effectively addressing the risks arising from TCO misuse. This is primarily due to the: manner in which Customs collects and stores its compliance data, which makes it difficult to verify the number, scope and outcome of compliance activities; and absence of an appropriate set of performance measures against which an assessment of the effectiveness of compliance activities can be undertaken.

15. To further improve Customs’ administration of the TCS and strengthen compliance monitoring arrangements, the ANAO has made three recommendations designed to: enhance engagement with key stakeholders; provide greater assurance regarding the assessment and decision-making process; and improve the monitoring and reporting of compliance activities.

Key findings by chapter

Administrative Arrangements (Chapter 2)

16. Governance and oversight arrangements have been established by Customs to facilitate its delivery of the TCS, including appropriate management arrangements that provide a sound basis for the effective delivery of the system. There is, however, scope to better define the responsibilities of the policy entity (Department of Industry) and the delivery entity (Customs) through the expansion and endorsement of the proposed TCS schedule to the current Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) between the two entities.

17. The achievement of the Government’s objectives for the TCS is reliant on effective stakeholder engagement, with Customs required to communicate with a broad range of stakeholders with diverse interests. Customs’ current approach to stakeholder engagement relies heavily on direct communications with manufacturers in relation to specific TCO applications, supplemented by general information on the system, which is communicated through Customs’ website, and TCO specific communication through the gazette. While direct communication on matters relevant to individual manufacturers has been well received, this approach is resource-intensive. In relation to the published materials that are currently available to stakeholders, there is scope for Customs to review the accessibility and coverage of TCS information to better support a broader range of local manufacturers. The development of a communications strategy, implemented in conjunction with enhancements to the information currently available on Customs website, would assist Customs to better direct its limited resources to those activities that enable key stakeholders to effectively engage with the system.

18. The administration of the TCS is underpinned by two information management systems—TARCON and Compliance Central—as well as the creation of paper files to record aspects of the assessment and compliance processes. There are, however, functionality issues that adversely impact on the extent to which these systems have supported the effective delivery of the TCS. Where data has been captured in TARCON in relation to the assessment process, extracting the data to inform internal decision-making has been difficult and time consuming. As a result, assessment officers have introduced workarounds to address known functionality limitations that, ultimately, increase the risks to the integrity of the data and create inefficiencies.8

19. Similarly, the capture of compliance data in Compliance Central and the subsequent analysis and use of this data to inform the continuum of compliance activities from education and awareness through to enforcement has also been limited because of the lack of system functionality. As a result, CAB was unable to accurately report with a sufficient level of confidence the complete number, scope and outcome of compliance activities. Variability of compliance data over time has also affected the overall integrity of reported information. There is considerable scope for Customs to strengthen its approach to the management of compliance data as it transitions to the new operating environment within the Department of Immigration and Border Protection.

Assessing Tariff Concession Order Applications (Chapter 3)

20. Customs receives approximately 940 TCO applications every year, with around 80 per cent of applications resulting in a TCO being made. Customs has implemented generally sound practices to assess TCO applications, with appropriate processes in place to determine the validity of applications through an eligibility assessment process, such as the establishment of a pre-screening checklist to determine whether applicants met legislated eligibility requirements.9

21. There are, however, aspects of the TCS that make the assessment process difficult. In particular, the requirement for applicants to have undertaken appropriate searches for local manufacturers of substitutable goods is difficult for Customs officers to accurately assess. In effect, there is a strong disincentive for full disclosure of an applicant’s knowledge of local manufacturing as the presence of a local manufacturer may mean that a TCO is not made. This disincentive, coupled with the range of ways that evidence of appropriate searches can be manipulated (for example, the use of different search terms across multiple search engines) adds to the complexity of the assessment process. With regard to the assessment process, Customs is yet to establish a compliance model that provides a framework for addressing applicants’ non‐compliance and developing responses according to the nature, level and cause of non‐compliance and the level of co-operation from applicants.

22. The decisions relating to the TCO applications examined by the ANAO were made by a Customs officer with the required delegation. However, the extent to which the rationale for these decisions was documented was inconsistent. The absence of appropriate documentation to support key decisions makes it more difficult to determine the basis on which the delegate, on behalf of the CEO, considered that the application fulfilled legislative requirements. There would be benefit in Customs strengthening its guidance to assessment officers and reinforcing the importance of documenting key decisions to improve the transparency and accountability of the TCO decision-making process.

23. The framework for the TCS includes a number of opportunities for internal and external review of decisions, in addition to a process for compliments and complaints management. These arrangements provide an appropriate framework for the review of decisions. There would, however, be merit in Customs implementing a risk-based quality assurance program to examine a random selection of decisions, including decisions to make a TCO, which, by their nature, are unlikely to be referred by applicants for review.10

Managing Current Tariff Concession Orders (Chapter 4)

24. In general, Customs has implemented effective arrangements to manage TCOs once they have been made, including processes for TCO review and revocation. In particular, appropriate processes are in place to respond to local manufacturer initiated revocations. In relation to the 10 revocations that were initiated by local manufactures in the ANAO’s sample11, all assessments were completed within the legislated timeframes and all decisions were made by appropriately delegated officers.

25. In late 2012, Customs received budget funding to undertake a review to help ensure the ongoing validity of TCOs. This funding was provided on the basis of 1000 TCOs being reviewed annually. Customs has not, however, recorded the total number of reviews undertaken on an annual basis and has not reported on its progress against this annual target, rather it has reported on the number of TCOs revoked and the potential duty recovered.12 There is scope for Customs to improve aspects of its management of the TCO review program, including: enhancing the documentation of the risk analyses used to inform program activity; and strengthening the reporting of progress against the commitments that were established in the initial proposal to government.

Compliance with Tariff Concession Orders (Chapter 5)

26. Economic risks, such as the misuse of a TCO or other concession item, were considered by Customs to present a ‘medium’ risk and it was determined that the Compliance Assurance Branch (CAB) would focus its efforts on reducing and containing the risk.13 CAB collected intelligence relating to compliance with the TCS through compliance activities (including general monitoring, campaigns and projects) and stakeholder engagement. The limited data retained by CAB indicated that its compliance program was targeted towards TCO-related imports that were considered to present a higher risk of TCO misuse. However, the manner in which compliance data is collected and stored did not allow Customs to verify this information, which undermines the confidence that can be placed in the reported performance relating to compliance activities (to both internal management and external stakeholders).14 Further, in relation to the limited number of targeted campaigns and projects established by Customs to address TCO misuse, performance measures had not been established by CAB that would inform an assessment of the extent to which campaign objectives had been achieved. As such, CAB was not well placed to determine the effectiveness of its program of compliance activities.

27. Tariff concession schemes are complex to administer, with the management of compliance requiring specialist knowledge and a detailed understanding of the relevant legislation and regulation. Customs does not, however, provide training to its compliance officers on the specific requirements of the TCS. Providing increased support to officers undertaking compliance activities would better place Customs to more effectively deliver these activities and manage the risks in relation to the incorrect application of TCOs.

28. Customs is currently implementing a number of significant reforms, including its amalgamation with the Department of Immigration and Border Protection and the restructure of its compliance function. As the revised arrangements are yet to be fully implemented, it is not possible to determine at this stage the extent to which the arrangements will have an impact on compliance activity for the TCS. There would, however, be merit in Customs reflecting on the findings of this report when implementing revised compliance arrangements as part of its reform agenda.

Summary of entity response

29. Customs’ summary response to the proposed report is provided below, while the full response is provided at Appendix 1.

The Australian Customs and Border Protection Service (ACBPS) notes the ANAO finding that the Tariff Concession System (TCS) is supported by mature administrative arrangements that provide a sound basis for assessment and management of Tariff Concession Orders (TCO), including the processing of TCO applications, objections, revocations, and the management of TCOs that are in use.

ACBPS acknowledges that the manner in which it collects and stores its compliance data makes it difficult to verify the number, scope and outcome of compliance activities and that performance measures could be improved. ACBPS will take measures to better support delivery and oversight of activities directed at the risk of TCO misuse.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 2.35 |

To build greater awareness and promote the Tariff Concession System, the ANAO recommends that the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service:

Customs’ response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No. 2 Paragraph 3.47 |

To improve the transparency and accountability of the Tariff Concession Order decision-making process, the ANAO recommends that the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service strengthens its guidance to assessment officers and reinforces the importance of documenting key decisions. Customs’ response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No. 3 Paragraph 5.57 |

To better support the delivery and oversight of compliance activities directed at managing the risk of Tariff Concession Order misuse, the ANAO recommends that the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service:

Customs’ response: Agreed |

1. Background and Context

This chapter provides an overview of the Tariff Concession System and outlines the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service’s approach to assessing applications for, objections to, and applications to revoke Tariff Concession Orders. It also sets out the audit objective and approach.

Introduction

1.1 Customs duty and Commonwealth taxes are imposed on certain goods when they are imported into Australia, with the rate of duty payable determined by the tariff classification of the goods. Imposing duty on certain imported goods is designed to influence the flow of trade by regulating their value to protect Australia’s local economy and industry. In 2013–14, Customs facilitated the importation of 30.6 million air cargo and 2.9 million sea cargo consignments.15 It was also responsible for collecting customs duty and border-related taxes and charges, which totalled $13.7 billion.16

1.2 There are, however, a number of ways that importers can obtain duty-free entry of imported goods into Australia, including through accessing free trade agreements17 and duty concession schemes, such as the Enhanced Project By-law Scheme (EPBS)18 and the Tariff Concession System.

Tariff Concession System

1.3 The Tariff Concession System (TCS), which was established in its current form in 199219, is intended to assist Australian industry and to reduce costs to the general community where the imposition of a tariff20 serves no industry assistance purpose—that is, where no local industry produces substitutable goods.21

1.4 There are certain classes of goods that are ineligible for concessions under the TCS, including: goods produced in industries where there is an established local manufacturing base including foodstuffs, clothing, cosmetics and furniture; or where the importation of a good is regulated or restricted. The tariff classifications for these goods are listed on an Excluded Goods Schedule (EGS).

1.5 To receive a duty concession under the TCS, an imported good must be covered by a current Tariff Concession Order (TCO). A TCO consists of a tariff classification and descriptive text, which together describe the good that is covered by the TCO. Once a TCO has been made by Customs, it is available for use by any importer that seeks to import goods that correspond to the description and tariff classification. In 2013–14, around $1.8 billion in revenue to the Commonwealth was forgone through the use of TCOs, with Customs estimating that the amount of revenue forgone will increase to around $1.9 billion in 2014–15.

Applying for a Tariff Concession Order

1.6 The legislated process for assessing a TCO application is undertaken in two stages. The first stage assesses the validity of each application, with the details of a valid application published in the weekly Commonwealth of Australia Tariff Concessions Gazette (the Gazette). The second stage, which must occur between 50 and 150 days after notification of an application in the Gazette, requires Customs to determine whether the TCO will be made.

Assessing TCO applications

1.7 A valid application is one that:

- is submitted on the approved form, and contains the information required by the form;

- contains a full description of the goods, including a statement of the tariff classification that, in the opinion of the applicant, applies to the goods; and

- discloses all information that an applicant has, or can reasonably be expected to have, about Australian manufacturers of substitutable goods or potential substitutable goods. This includes details of all inquiries made by the applicant to establish that there are reasonable grounds for asserting that there are no manufacturers of substitutable goods in Australia.

1.8 Following receipt of a TCO application, Customs has 28 days to process the application and determine whether it is valid. As soon as practicable after the validity of the application is determined, a notice must be published in the Gazette. Initially, Customs is required to verify the tariff classification and descriptive text of the TCO, assess the research supporting the application, and if necessary, undertake additional research of potential local manufacturing. Applications that are assessed as invalid by Customs will either be requested to be withdrawn or be rejected by the assessing officer.

Making a Tariff Concession Order

1.9 Once made, a TCO is available to all importers of the described goods until it is revoked.22 Customs’ decision on whether to make a TCO is to be based on:

- the information contained in the application;

- any objections from local manufacturers to the proposed TCO;

- any subsequent submissions provided by the applicant (including where the applicant and a local manufacturer have designed an alternate descriptive text); and

- the results of any additional inquiries made by Customs.

1.10 If there is no potential local manufacturer (identified either through Customs-initiated research or by an objection made by a local manufacturer), Customs is to make the TCO, notify the applicant in writing and publish the TCO details in the Gazette. A TCO will be available for use from the date of the application, not the decision. Where importations occur between the date of the application and the making of a TCO, importers may apply for a refund of any duty paid. An example of a TCO is provided at Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Example of a Tariff Concession Order

Source: Customs Gazette No TC 14/47, Wednesday, 3 December 2014.

Objections

1.11 Under the TCS, it is in the interests of local manufacturers to review the Gazette and consider whether they manufacture substitutable goods for those described in a TCO application. Customs may also contact potential local manufacturers to help ensure that reasonable grounds exist for believing that, on the day on which the application was lodged, there were no producers in Australia of substitutable goods.

1.12 If a local manufacturer decides to object to the TCO, they must do so within 50 days of the original gazettal date. However, Customs has a period of 150 days during which it may invite objections. A valid objection must be on the approved form and be supported by sufficient evidence to demonstrate that the locally manufactured goods are substitutable for the goods described in the TCO application.23 Customs is also required to inform the applicant in writing and provide a short statement outlining the grounds on which each objection is based. The applicant and the objector may agree to an amendment to the TCO description, such as narrowing the description of the goods with any revision to be included in a subsequent Gazette.

1.13 In 2013–14, Customs received 941 TCO applications, 133 objections and made 770 TCOs (see Table 1.1 for further details). Customs reported in its annual reports between 2011–12 and 2013–14, that it had met the legislated timeframes for the TCO decision-making in all cases.24

Table 1.1: TCO applications (2012–13 and 2013–14)

|

Application Actions |

Number(1) |

|

|

Initial Stage (prior to gazettal) |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

|

Applications received |

998 |

941 |

|

Applications rejected |

99 |

36 |

|

Applications withdrawn |

118 |

96 |

|

Approval Stage (after gazettal) |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

|

Objections received (2) |

88 |

133 |

|

TCOs made |

762 |

770 |

|

TCOs refused (3) |

43 |

79 |

Source: ANAO analysis of Customs information.

Note 1: There is a lag of up to 150 days between gazettal of a valid application and making a decision. As a result, the number of applications and decisions do not align within a 12-month period.

Note 2: When an objection is received, the applicant and the party objecting to the application may agree to a narrowing of the wording of the TCO. If this occurs, the TCO is recorded as made rather than refused.

Note 3: While multiple objections can be received against the making of a single TCO, if successful Customs systems only record the refusal against a single objection.

Revocations

1.14 There are a number of circumstances under which a TCO may be revoked, either at the initiation of a local manufacturer or the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of Customs. These circumstances include if the:

- requirements of a TCO were no longer being met (for example if an Australian manufacturer of substitutable goods submits a valid application for revocation, or if the goods described by the TCO were included on the EGS);

- TCO is no longer required as it has not been used in the preceding two years; or because the general tariff rate for that good has been reduced to ‘free’;

- TCO contains a transcription error or error in the description of the TCO (including where changes to the Harmonised System25, or a ruling of the Administrative Appeals Tribunal, have changed the tariff classification); or

- TCO contains a description of the goods in terms of their intended end use.

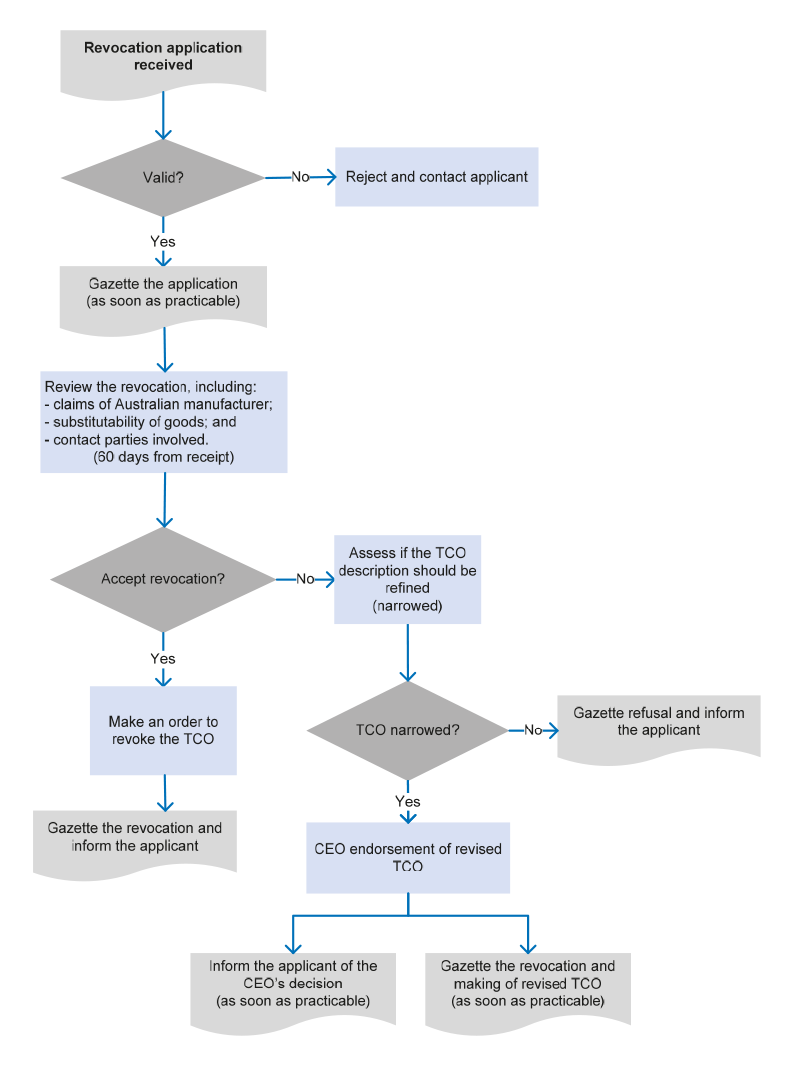

1.15 Similar to the objections process, a revocation initiated by a local manufacturer places the onus on the applicant to demonstrate why a TCO should be revoked. Once an application for revocation has been lodged, a decision is required within 60 days, based on the information provided in the request and inquiries made by Customs. Where Customs decides that the TCO should be revoked, the revocation takes effect from the date that the request was received, not the date of the decision. However, if Customs is satisfied that, by narrowing of the wording of a TCO, the TCO would only cover goods not manufactured in Australia, it may revoke and reissue a TCO with revised descriptive text. This process is known as a ‘revoke-reissue’.26

1.16 In 2013–14, Customs received 45 applications from local manufacturers for the revocation of a TCO. Of these, 43 were upheld. Table 1.2 summarises revocations of TCOs in 2013–14.

Table 1.2: TCO revocations (2013–14)

|

Local Manufacturer Initiated |

2013–14 |

|

|

Received |

45(1) |

|

|

Upheld |

43 |

|

|

Refused |

4 |

|

|

Withdrawn |

6 |

|

|

Cancelled |

14 |

|

|

Customs Initiated |

|

|

|

Tariff classification change |

2 |

|

|

Transcription error |

1 |

|

|

Inadequate description |

0 |

|

|

Goods excluded from the TCS because of EGS |

1 |

|

|

Tariff reduced to a free rate |

5 |

|

|

Subtotal revocations not related to the review |

9 |

|

|

TCO review revocations |

Became aware of local manufacturer |

15 |

|

Two years non use |

303 |

|

|

Subtotal review related revocations |

318 |

|

Source: ANAO analysis of Customs information.

Note 1: There is a lag of up to two months between receiving an application and making a decision. This accounts for the discrepancy between the number of applications and the number of decisions.

Targeted review of TCOs

1.17 In 2012–13, the Australian Government provided Customs with additional funding of $13.5 million over three years to expand its compliance assurance activities. This measure also provided Customs with additional staff to undertake a targeted review of current TCOs.

1.18 The first year of the targeted review focused on cookware and tableware, and led to the revocation of 16 TCOs and the receipt of a further 10 TCO revocation applications. Customs reported that the customs value27 of goods that used these TCOs in the 12 months prior to them being revoked exceeded $200 million.28 The review continued throughout 2013–14, with a total of 318 TCOs revoked as a result of local manufacturers being identified and/or because of two years non-use of the TCO. Customs estimated that the notional duty29 recovered in 2013–14 as a result of the review was $3.7 million.

Compliance with the use of Tariff Concession Orders

1.19 The existence of a TCO allows importers concessional entry of goods into Australia, subject to the goods meeting the tariff classification and description of the TCO. Managing importer compliance with nominated TCOs underpins the effective operation of the TCS, supports Australian manufacturers through the proper implementation of the tariff and helps to ensure the correct calculation and collection of duty.

1.20 Prior to 1 July 2014, the Compliance Assurance Branch (CAB) in Customs was responsible for enforcing compliance with TCS requirements.30 CAB was an organisational unit of the Compliance and Enforcement Division responsible for managing several categories of risk: regulated goods; economic (including revenue); and the cargo process, with an operating budget of around $27 million in 2013–14. CAB adopted an ‘intelligence-led, risk-based’ approach to managing economic risk. Under this approach, where a risk was identified, it was rated and treated according to the level of risk it represented and the resources available at the time.

1.21 From 1 July 2014, CAB ceased to exist and enforcement action became the responsibility of Strategic Border Command. Customs has also established a Revenue and Trade Crime Task Force to drive and coordinate a number of activities, including Customs’ commitment to enhancing revenue collection at the border.31 On 1 July 2015, responsibility for enforcement will move to the newly established Australian Border Force within the Department of Immigration and Border Protection.

Administrative arrangements

1.22 The Department of Industry (Industry) is responsible for administering the policy framework within which the TCS is delivered, with Customs responsible for the day-to-day implementation of the system.

1.23 Within Customs, the Industry Assistance Section (Trade Branch) is responsible for managing the TCS, including all decisions relating to the making and revocation of TCOs. In 2013–14, there were (on average) 12.4 full time equivalent staff, with expenses of $1.6 million (primarily staffing costs) to manage the TCS.

Related programs

Enhanced Project By-law Scheme

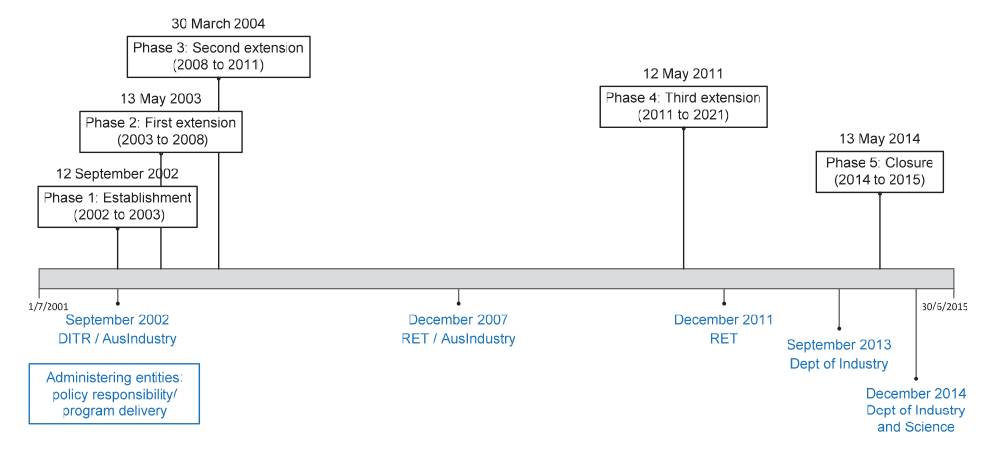

1.24 In 2002, the Australian Government established the Enhanced Project By-law Scheme (EPBS). The scheme reduces the tariff on eligible capital goods for major investment projects32 in specific industries33 that are supported by an approved Australian Industry Participation Plan.34 In contrast to the TCS, EPBS decisions are generally made at the project level for large items of equipment, rather than an individual item level. Only eligible goods that are not produced in Australia or that are technologically advanced, more efficient or more productive than those made in Australia are eligible for a concession under the EPBS. These criteria differ slightly to those established for the TCS.35

1.25 One method available to applicants to demonstrate that there is no locally made equivalent good is through a TCO for that good. As there is no fee set by Customs to assess a TCO application, this is likely to be a cost effective option for demonstrating eligibility against this criterion.

1.26 During consultation regarding proposed changes to the EPBS and TCS undertaken by Industry in 2009, Customs raised concerns regarding:

- the resourcing implications of an increased reliance on TCOs by applicants under the EPBS;

- the likelihood of more applications covering complex goods that are difficult to classify to a single tariff (increasing the complexity of application processing); and

- conflict in the objectives, terminologies and applicability of determinations between the two schemes, which increases the risks to both schemes where they are linked.

1.27 In 2010, an independent consultancy firm was commissioned to evaluate the EPBS, including its relationship with the TCS. The evaluation examined the scheme’s appropriateness, effectiveness, efficiency and the integration of the scheme with other government initiatives. It found that the scheme had sound policy foundations and, if implemented appropriately, worked in the national interest. However, it noted that for large projects, the EPBS should be the ‘scheme of choice’, rather than alternative approaches, such as the TCS or Preferential Trade Agreements.

Reviews of the Tariff Concession System

1.28 Since its establishment in 1992, the TCS has been subject to regular reviews. In January 1995, the then Minister for Small Business, Customs and Construction requested that Industry and Customs review the TCS.36 A major finding from this review was that costs in monitoring TCO applications were such that many small and medium enterprises did not monitor them and, therefore, did not submit objections where they might. The review recommended that the scheme be modified to impose most of the cost of the scheme onto those who benefited from the system—the importers.37 These changes to the system were enacted in 1996.

1.29 The Productivity Commission also reviewed Australia’s Tariff arrangements, including the TCS, in 2000. It concluded that there was a shift in the burden of the TCS from the manufacturer to the importer (primarily through increased requirements to identify potential local manufacturers, but also through changes to the definition of substitutable goods). This was consistent with the position that the costs should be borne by its beneficiaries.38 This position was further reviewed and endorsed in a joint Customs and Industry review of the TCS in 2008–09.

1.30 In September 2009, Customs participated in a number of Department of Industry-led stakeholder consultation sessions. Customs advised the department that, as part of this process, it received comments suggesting that unfair trading was occurring, specifically that some manufacturers were subjected to intimidation to prevent the lodgement of objections to a TCO. There were also concerns raised that TCOs were being made where there were local manufacturers of substitutable goods. Similar concerns have been raised during Senate Estimates hearings in May 2011 and in media reports in 2013.39

Audit objective, criteria, scope and methodology

Audit objective and criteria

1.31 The objective of the audit was to assess the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service’s administration of the Tariff Concession System.

1.32 To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- an appropriate governance framework to support the effective operation of the system was established;

- a consistent, accountable and transparent assessment process for TCO applications has been implemented;

- processes and systems for the ongoing management, review and eventual revocation of TCOs are effective; and

- the approach to managing compliance with TCO requirements was sound.

1.33 The audit reviewed the administration of the TCS, and the compliance strategies implemented to mitigate the risks relating to the incorrect application of a TCO. It did not review the process of issuing refunds where a TCO has been applied, the use of penalties after misuse has been detected, or the process to recover underpaid duties once they have been identified.

Audit methodology

1.34 In undertaking the audit, the ANAO:

- reviewed departmental files and documentation;

- interviewed and/or received written input from departmental staff and relevant stakeholders, including TCS users and industry associations;

- analysed a sample of 10 per cent of all TCOs made between 18 March 2011 and 18 March 2014. This included 282 TCOs, of which 264 were the result of an application and 18 were TCOs that were revoked and reissued by Customs40; and

- examined compliance data relating to the potential misuse of a TCO.

1.35 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of $476 500.

Report structure

1.36 The structure of the report is outlined in Table 1.3.

Table 1.3: Report structure

|

Chapter |

Overview |

|

2: Administrative Arrangements |

Examines the governance and oversight arrangements established by Customs to administer the TCS. |

|

3: Assessing Tariff Concession Order Applications |

Examines the assessment process for TCO applications, including eligibility review and gazettal, the decision review process and complaints management. |

|

4: Managing Current Tariff Concession Orders |

Examines Customs’ management of current TCOs, including processes for their revocation and review. |

|

5: Compliance with Tariff Concession Orders |

Examines the compliance strategies and approaches adopted by Customs to manage the risks relating to the incorrect application of TCOs. |

2. Administrative Arrangements

This chapter examines the governance and oversight arrangements established by Customs to administer the Tariff Concession System.

Introduction

2.1 The effective management of the Tariff Concession System (TCS) requires sound administrative arrangements and support systems that allow Customs to manage its regulatory responsibilities and build stakeholder and public confidence. The ANAO examined:

- the oversight arrangements in place for the TCS;

- stakeholder engagement;

- staffing arrangements and guidance material;

- information management; and

- performance monitoring and reporting.

Oversight arrangements for the Tariff Concession System

2.2 As outlined earlier, Customs has assigned responsibility for administering aspects of the TCS to the Trade Branch and CAB.41 Oversight of administration and compliance functions are provided by the Operations Committee and ultimately the Customs’ Executive.

2.3 The regulatory framework for the TCS, including the assessment of TCO applications and revocations, is administered by the Industry Assistance Section of the Trade Branch. Responsibility for decisions regarding the acceptance or rejection of TCO applications and the subsequent making or refusal of TCOs are to be made by the CEO of Customs, who has delegated this responsibility to specified Customs officers within this section (Customs Level 2 and above).

2.4 The Assistant Secretary Trade is accountable for the performance of the TCS and its use of departmental resources. Information on the performance of the TCS (in relation to administrative and operational matters) is reported to the Assistant Secretary through monthly management reports, which are supplemented with additional issues-based reports as required. The monthly management reports include information on activities undertaken in the day-to-day operation of the TCS, with a ‘highlights’ section that is used to notify the Assistant Secretary of significant TCO decisions, including outlining potential impacts on revenue.

2.5 The CAB Executive provided oversight of the assessment of the risk of TCO misuse and for the allocation of resources to address this risk. Day-to-day responsibility was assigned to the National Director–Compliance and Enforcement Division.

Operations Committee

2.6 In 2009–10, Customs established an Operations Committee, which meets monthly, to focus on organisational reporting against planned outcomes. Matters arising from these committee meetings may be referred to Customs’ Executive for decision or information.

2.7 The Trade Branch and CAB provide (separate) reports to the Operations Committee in ‘dashboard’ format. CAB also supplements the dashboard report with an additional narrative report. Both reports focus on work level activity, such as tasks undertaken, budget information and staffing levels. Information on the administration of the TCS has generally not been reported separately with the exception of the systematic review of TCOs currently underway in Trade Branch (discussed in Chapter 4). Overall, the arrangements established for the TCS provide an appropriate level of oversight in the context of Customs’ broad range of responsibilities.

Stakeholder engagement

2.8 The effective operation of the TCS is reliant on the maintenance of sound relationships with the responsible policy entity—the Department of Industry—and other stakeholders involved in the TCS, including potential importers and local manufacturers.

Department of Industry

2.9 As the policy entity and delivery entity respectively, Industry and Customs have joint responsibilities in the development, administration and delivery of a number of industry assistance programs at the border. The relationship between Industry and Customs is underpinned by an entity-level Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), supported by officer-level engagement.

2.10 The MOU provides a broad outline of the general obligations of both parties to ensure the efficient and effective operation and administration of respective portfolio responsibilities. The current MOU has a number of schedules targeting specific trade concession arrangements, such as the EPBS. A schedule relating to the TCS has been drafted, but is yet to be endorsed. The schedule, as it is currently drafted, sets out the responsibilities of each entity and provides for regular (quarterly) meetings that are designed to ensure that administrative functions are effective and that proposed changes to policy, legislation and administrative arrangements are appropriately managed.

2.11 The endorsement of the TCS schedule will help to provide an appropriate framework to underpin the ongoing administration of the TCS. There would, however, be benefits in both agencies reviewing the agreement to help to ensure that responsibilities for the TCS functions are clearly articulated. For example, there is scope for the schedule to more clearly assign responsibility for the promotion of the TCS (discussed further at paragraph 2.14).

Engagement with Industry

2.12 In the absence of a specific schedule to the MOU governing the administration of the TCS, Industry and Customs have established appropriate operational-level communications to support the delivery of the system. Day-to-day contact occurs between the Trade and International Branch (Industry) and the Trade Branch (Customs).42 There has, for example, been:

- input from Industry into the revision of a number of key documents guiding Customs’ administration of the TCS;

- briefings on issues, such as the use of the TCS and its relationship with the EPBS; and

- correspondence and joint participation in meetings with potential users of the TCS.

2.13 In addition, both agencies are currently discussing possible legislative amendments for consideration by government that are designed to assist local manufacturers to lodge objections and to request the revocation of TCOs that infringe on their business.

2.14 The current level of engagement between Industry and Customs is supported by a long-standing relationship between the relevant managers in both agencies, and their understanding of risks to the effective delivery of the TCS. Clearly articulating the responsibilities of both agencies and establishing a fit-for-purpose performance measurement framework in the TCS schedule to the MOU would further strengthen existing arrangements, frame the expectations of both agencies and mitigate the potential risk of a loss of corporate memory resulting from staff turnover.

Stakeholder consultation

2.15 As outlined in Chapter 1, there have been a number of recent reviews that have provided an avenue for TCS stakeholders to provide feedback to both Industry and Customs on the operation of the TCS, including:

- workshops and focus groups held with representatives from the Customs Brokers and Forwarders Council of Australia Inc., the Law Council, and the Conference of Asia Pacific Express Carriers (with participation managed through invitation) that contributed to the review of guidelines, such as the ‘Description of Goods for Tariff Concession Order Applications’; and

- consultation with industry stakeholders (managed by Industry) relating to government policies aimed at strengthening Australian industry participation (with an open call for information).

2.16 These types of reviews have provided stakeholders with the opportunity to inform the administration of the TCS, including offering a user perspective on whether policy intentions are being met through the system.

2.17 Overall, the feedback that Customs has received regarding stakeholder awareness of the TCS has been mixed. Generally, larger manufacturers are more likely to be aware of the TCS and to be able to dedicate resources to the weekly review of the Gazette than small to medium sized local manufacturers. Notwithstanding the greater awareness of larger manufacturers, Customs has received feedback indicating that there is scope to improve the quality of the information made available for all TCS applicants.

2.18 Customs currently provides information to users of the TCS through:

- general awareness raising and promotional activities;

- direct ‘one-to-one’ stakeholder communications;

- published TCS materials; and

- emailing the gazette on request.

General awareness raising and promotional activities

2.19 While an overall TCS communications strategy is yet to be developed, in 2009–10 Customs drafted a communications strategy that was designed to build awareness of the Gazette. The aims of the draft strategy were to inform industry about the Gazette’s function and to encourage stakeholders to consult the Gazette on a weekly basis. Although the strategy was not finalised, it did guide changes to Customs’ website, the inclusion of advertising material in a manufacturing industry publication—Manufacturer’s Monthly (digital and print versions)—and an increase in direct communications with manufacturers.

2.20 In 2010, TCS media advertisements were discontinued, as Customs considered that this type of promotional activity did not provide an increase—proportionate to the cost—in manufacturer awareness of the TCS. Customs continues to use its website to engage with potential importers and local manufacturers.

2.21 Customs has not evaluated the promotional activities it has undertaken over the last five years, but considers that general awareness programs that promote the name of a government program (such as the advertisements in Manufacturer’s Monthly) have minimal impact on the target populations, primarily because stakeholders gain no immediate benefit. Stakeholders were more engaged with the TCS when they became aware of an application that affected them directly.

Direct engagement

2.22 Since 2009, Customs has increased its focus on direct engagement with specific industry groups and individual manufacturers, with activities including:

- writing to industry groups annually to increase awareness of the TCS among local manufacturers;

- increasing its notifications to local industry of TCO applications outside of the gazettal process; and

- outreach visits to specific manufacturers or industry groups to:

- promote awareness of the system and explain its key elements; and

- facilitate objections or applications to reject TCOs where a substitutable locally produced good exists.

2.23 Stakeholders have provided positive feedback to Customs regarding its direct engagement initiatives. In particular, stakeholders have indicated that they are appreciative of the active approach that Customs has taken to informing them of potential TCOs that they may wish to object to, or current TCOs that they may wish to apply to revoke, as well as the clear manner in which the provisions of the TCS are communicated.

2.24 The direct engagement approach has not, however, led to a proportionate increase in subscriptions to the Gazette, with only one positive response from the 70 invitations to subscribe to the Gazette issued in May 2014. Nevertheless, the approach has contributed to greater involvement of local manufacturers in the TCO application process. For example, of the 264 TCO applications in the ANAO’s sample, 234 were accepted as valid applications. In its assessment of these applications, Customs contacted 186 potential local manufacturers across 94 applications to help to ensure that the applicant fulfilled its obligation to establish that there were reasonable grounds for believing that there were no producers in Australia of substitutable goods.43 Local manufacturers responded to this request from Customs on 75 occasions (40 per cent). There has also been a general increase in local manufacturer initiated objections.

2.25 While targeted contact with individual stakeholders is likely to generate greater interest, it is a resource-intensive approach. There is also potential for manufacturers to rely on Customs’ notifications and, therefore, neglect to examine the Gazette. This increases the workload on, and the expectations of, Customs, and has the potential to damage relationships between local manufacturers and Customs where relevant local manufacturers are not contacted in relation to TCO applications.

Published TCS materials

The Gazette

2.26 The Gazette is used by Customs to identify and provide information to Australian manufacturers who may manufacture goods that are substitutable to those described in a TCO application. In order to prevent Customs making a TCO that infringes on local industry, all Australian manufacturers are encouraged to review this publication on a weekly basis, as previously explained, and submit objections, where relevant.

2.27 The effectiveness of the Gazette as a communication tool is dependent on Australian manufacturers’ level of awareness of its purpose and the extent to which relevant information is readily available. The current format of the Gazette has not changed over many years, and does not facilitate the efficient identification of relevant TCOs. For example, local manufacturers cannot receive notifications based on nominated interests, such as specific chapters of the tariff, or based on subject areas. Stakeholders have informed the ANAO that regular users of the TCS (such as customs brokers) are more likely to use in-house compilations or proprietary systems listing TCOs rather than the Gazette.

Tariff Concession Order listing

2.28 In addition to the Gazette, Customs also publishes a digital listing of current TCOs on its website.44 The digital compilation of TCOs is created by collating TCOs made under different tariff headings into a single document.45 This prevents the use of ‘key word’ searching across all TCOs to identify orders that may already exist. The ability to search the total TCO population more broadly is important, as goods that are substitutable can be found across a range of different tariffs.46

2.29 Customs has informed the ANAO that the creation of the digital listing of TCOs is a manual process, with an officer required to extract relevant information from the Gazette to update the listing of TCOs. Although this process is to occur weekly, longer periods between updates may occur when other tasks are given priority. Up-to-date information can still be accessed through the Gazette. There would be merit in Customs assessing the costs and benefits of automating the digital listing of TCOs directly from TARCON47 and providing the capability for stakeholders to efficiently identify those TCOs relevant to their business.

Web-based information

2.30 Customs also provides information supporting the TCS on its website.48 Customs’ homepage for the TCS provides access to number of documents relevant to the system, including:

- forms for TCO applications, objections and revocations;

- advice to applicants about their obligations when applying for a TCO;

- a factsheet; and

- an historical listing of Gazettes and digital listing of TCOs.

2.31 When assessed together, these documents provide a broad overview of the system, applicant obligations and access to the Gazette. Customs could enhance existing information by including additional material directed at local manufacturers to more clearly outline their responsibilities and to better explain key concepts, such as:

- the role of local manufacturers to monitor the Gazette and submit objections and requests for revocation as necessary;

- the breadth of the substitutability test; and

- the absence of a market test.

2.32 In addition to supplementing the information available on the TCS, the accessibility of the information could also be improved as navigating the website is difficult. Webpage titles do not accurately reflect the content of the page, the navigation structure requires users to have a detailed understanding of the relationship between the TCS and the tariff and search results do not prioritise the most relevant webpage.

Conclusion

2.33 The diversity of TCS users means that Customs’ information has to reach a broad audience, ranging from small to medium local manufacturers to large multinational organisations, professional customs brokers and import agents. Although the TCS has been operating for many years, Customs is yet to develop a communications strategy for the TCS to guide its engagement with TCS stakeholders. This is, in part, because of a lack of clarity between Customs and Industry regarding responsibility for the promotion of the TCS.

2.34 The development of a communications strategy for the TCS would assist Customs to maximise the effectiveness of communications and awareness raising activities, particularly in the context of constrained resources. Important elements of this strategy could include, for example: assigning responsibility for specific activities; identifying stakeholders involved in the system; determining communication needs; and tailoring the most appropriate methods of communication. The regular review of the strategy, including incorporating stakeholder feedback, would help to expand the reach of communication and awareness activities and, ultimately, local manufacturer and importer engagement in the system.

Recommendation No.1

2.35 To build greater awareness and promote the Tariff Concession System, the ANAO recommends that the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service:

- develops a Tariff Concession System communications strategy, in consultation with the Department of Industry, aimed at increasing system awareness, with a particular focus on local manufacturer engagement;

- reviews the strategy periodically to inform the ongoing targeting and refinement of communication activities; and

- reviews the appropriateness and accessibility of Tariff Concession System information that is currently made available to stakeholders.

Customs’ response: Agreed

Staffing arrangements and guidance materials

Staffing arrangements

2.36 The effectiveness of Customs’ administration of the TCS is largely reliant on appropriately skilled and knowledgeable officers assessing applications and objections, supported by guidance, procedures and information systems. The profile of officers assessing TCO applications, objections and revocations is that of an experienced and stable workforce. Customs has recognised, however, that the loss of experienced officers has the potential to severely affect its ability to manage succession and build suitably capable officers to meet its challenging and complex work program.

2.37 The risks arising from the loss of experienced officers is exacerbated by the absence of a structured training program to support the professional development of officers undertaking the assessment of TCOs. At present, training occurs ‘on-the-job’, supported by mentoring, regular team discussions on key issues and specific instructions by supervisors on matters such as legislative requirements. This approach to training is heavily reliant on the availability of experienced colleagues to guide and mentor new officers. The development of core competencies and a tailored training program would better place Customs to manage turnover of TCS staff.

Integrity of the TCS decision-making process

2.38 Customs is aware of the risk of TCS decisions being compromised, including where decisions are made by delegates who are conflicted due to personal interests. To address this risk, Customs has:

- undertaken risk assessments of the integrity of its decision-making process;

- appointed an Integrity Support Officer within the decision-making team; and

- included a step in the TCO screening checklist (but not in the relevant Practice Statement) that instructs delegates with a conflict of interest to notify the Director (Customs Level 5 officer).

2.39 Customs has assessed the overall risks to the integrity of the administration of the TCS to be low, with specific risks allocated ratings ranging from very-low to medium. Risk mitigation factors have been developed, including the presence of legislated internal and external review points and the public gazettal of decisions.

Guidance material

2.40 Customs has developed guidance material for the TCS including: workflow charts; a screening checklist; standard operating procedures; practice statements; instructions and guidelines; and recently updated its guidance for making TCO decisions and conducting site visits to applicants. Overall, these documents provide a suitable framework for TCS decision-making, including providing strong links between the requirements set out in legislation and Customs’ work processes.

Information management

2.41 To support the administration of TCOs, Customs retains information on hard-copy files, a SharePoint site49, spreadsheets and databases50, email systems and a business information management system—TARCON. Information on compliance activities is recorded by CAB officers in the Compliance Central information management system (discussed in Chapter 5).

TARCON

2.42 TARCON is a bespoke information management system that was implemented in 2005. It is now considered by Customs to be a legacy system. It stores and processes the information supporting the administration of seven types of concessional instruments, including the TCS.

2.43 There are a number of activities that are recorded and managed in TARCON to support the TCS, including:

- entering an application for a TCO;

- recording a decision to make or refuse a TCO;

- recording an objection to the creation of a TCO;

- revoking a TCO; and

- reviewing a TCO decision.

2.44 Once relevant information is entered into TARCON, information is exchanged with the Integrated Cargo System (ICS)51 in relation to those TCOs that are current and available for importers to use.

2.45 Applications for TCOs are received by Customs in a number of formats, none of which allow the automatic migration of information from the application into TARCON. As a consequence, Customs officers are required to manually extract data from these documents and enter the information into TARCON. Customs officers must also access both TARCON and hard copy files to obtain complete information regarding the material that has been provided to Customs regarding a TCO application and Customs’ responses to applicants.

2.46 Customs has advised that, where data has been captured or created in TARCON, extracting it is difficult and time consuming. This inhibits the re-use of information and the creation of intelligence to inform internal reviews of TCO coverage, the preparation of risk assessments and the analysis of past actions to target regulatory and educational activities.

2.47 While TARCON is considered to be a generally stable system, there have been a number of issues identified by users that impact on its efficiency. Customs advised that these issues have been raised internally, but to date they have not been addressed because of the:

- relatively small number of system users (given Customs’ wider enterprise architecture); and

- age and complexity of the system.

2.48 Ultimately, the deferral of enhancements and remediation work on TARCON has resulted in necessary workarounds and inefficiencies being introduced into work processes—for example, the implementation of a manual check to reconcile the accuracy of the data exchanged between TARCON and ICS.52

Compliance Central

2.49 CAB records information regarding its compliance activities in Compliance Central53, a case management and reporting system that Customs has acknowledged has limited reporting capability. The compliance data retained in Compliance Central is ‘live’, which, in effect, means that the results reported at one point in time may not be replicable at a future point in time because the source records have been changed. The source records may be changed after reporting has occurred when: the application for a refund is successful; an alternate TCO has been identified to cover an imported good; and concessions or appeals after a compliance activity has been completed. The ANAO sought advice from CAB on the extent to which records may be altered and the impact this has on the integrity of reported data. As a result of system functionality issues, CAB was unable to provide this information. In addition, Compliance Central experienced a period of reduced capability between February and July 2014 when, due to the unexpected outcome of a system upgrade, the ability to create and access reports was further limited.

2.50 CAB was unable to accurately report, with any level of confidence, the complete number, scope and outcome of its compliance activities. These data integrity issues limited CAB’s ability to analyse its compliance activities and, ultimately, determine the effectiveness of these activities and report on its compliance program to internal and external stakeholders. There is significant scope for Customs to strengthen its approach to the management of compliance data as it transitions to the new operating environment.

2.51 Overall, Customs has recognised that its current IT operating environment is characterised by duplication of effort and the inefficient use of resources. In response to a number of recent reviews that have highlighted deficiencies in its IT environment, Customs has embarked on a four-year business alignment strategy that is planned to deliver more integrated, responsive information and services.

Performance monitoring and reporting

2.52 A sound performance management framework facilitates internal management decision-making as well as external accountability. Appropriate performance indicators (KPIs) and reliable performance information form the basis of transparent and accountable management reporting. The ANAO reviewed Customs’ performance reporting framework in relation to the TCS.

2.53 The objective of the TCS is to assist Australian industry to become internationally competitive and to reduce the costs to the general community by the reduction of duties where there is no local industry to protect. This objective, which is established in a range of Customs documents such as the relevant Practice Statement—Practice Statement No: 2010/16: Tariff Concession System (TCS)—is appropriately aligned to the policy objective set by government.

2.54 Customs’ performance indicators relating to the management of TCOs outlined in its Portfolio Budget Statements (PBS) and reported against in its annual reports provide information regarding the: amount of duty forgone through the use of TCOs; proportion of TCS applications processed in accordance with legislated timeframes; and number and outcome of TCO decisions that have been referred to external agencies for review (to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT) and the courts). In addition, specific actions relating to the TCS have also previously been reported. For example, the Customs Annual Report 2012–13 contained coverage of the targeted review of TCOs.

2.55 Customs has also indicated that the following KPIs, which are included in its PBS, are indicators of processing efficiency and of the quality of decision-making:

- the proportion of TCS applications processed in accordance with legislated timeframes; and

- the number of decisions that have been referred to the AAT and courts for review—and the outcomes of these cases.

2.56 Customs has advised the ANAO that this first performance indicator relates to whether decisions have been made prior to the ‘deeming’ provisions of the legislation being applied. However, the legislation establishes a timeframe for the assessment of an application, which includes notifying the applicant of the outcome. In relation to the second indicator, while the number of decisions that have been referred to the AAT and courts for review—and the outcomes of these cases—provides a qualitative assessment of Customs’ decision-making processes, the current measure does not provide coverage over those decisions that are less likely to be referred to the AAT, such as decisions made where there is no objection. Further clarification of these indicators would enable Customs to better demonstrate the extent to which it is achieving its regulatory objectives.

Quality and accuracy of information regarding compliance with the TCS

2.57 To inform internal and external stakeholders about the TCS compliance program, Customs produces reports that provide information relating to the number, scope and results of its compliance program. However, as discussed earlier in paragraphs 2.49 to 2.50, the manner in which compliance data is collected and stored means that CAB was unable to replicate reported data over time, which adversely impacts on its ability to: effectively use the data to inform internal intelligence collection and risk assessments; and accurately report on the effectiveness of its compliance activities. Further, CAB had not sufficiently informed the internal and external users of its compliance data that reported performance levels may change over time because of amendments to source data.

Conclusion

2.58 The TCS is a mature system, supported by established governance, oversight and management arrangements that provide a sound basis for the effective delivery of the system. There is, however, scope to better define the relative responsibilities of the Department of Industry and Customs through the expansion and endorsement of the TCS schedule of the MOU between the two entities.

2.59 The effective operation of the TCS is reliant on importers and local manufacturers being aware of the system. Customs has undertaken a number of awareness raising activities, including providing information through its website, publications and direct communications. While there has been a positive response from stakeholders, particularly following direct communications, there is scope for Customs to improve its stakeholder communications. The development of a communications strategy, implemented in conjunction with improvements to web-based information, would assist stakeholders to more effectively engage with the system.

2.60 The extent to which Customs’ information management systems facilitate the effective delivery of the TCS—both in supporting the application process and compliance arrangements—is limited. Functionality issues with existing systems have required officers to develop workarounds that have increased the risks to data integrity and also impacted on the efficiency of TCS administration. In general, the systems do not facilitate ready access to retained data to inform ongoing management. In particular, the variability in compliance performance data over time means that it is not possible, with any confidence, to accurately determine the number and nature of compliance activities relating to TCO misuse. As a result, Customs’ ability to determine the effectiveness of CAB’s compliance activities and accurately report on its compliance program to external stakeholders, including the Parliament, is limited. In transitioning to the new operating environment, there is considerable scope for Customs to improve its approach to the management of its compliance data.

2.61 Customs has developed a number of performance measures that it reports against to external stakeholders. However, these could be better defined and expanded in relation to administering TCOs to enable Customs to demonstrate the extent to which it is achieving the objectives established for the system.

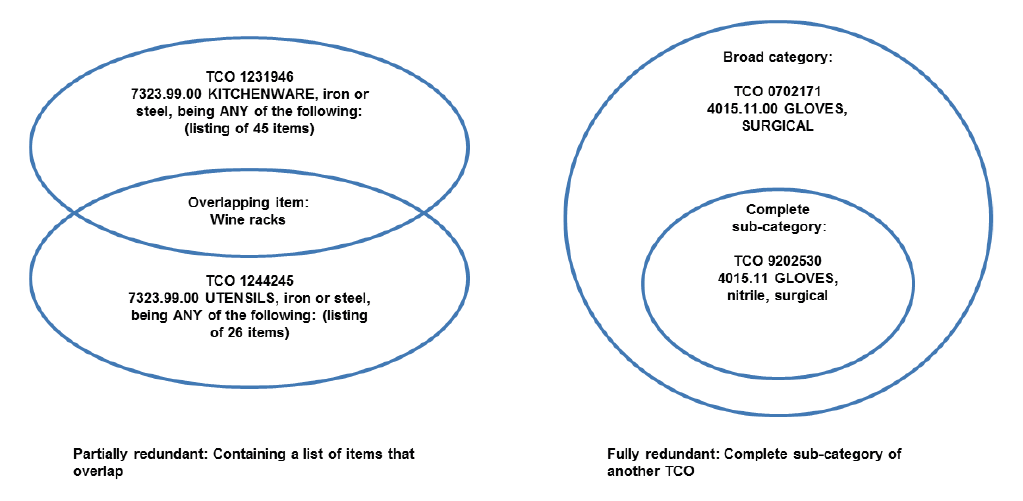

3. Assessing Tariff Concession Order Applications

This chapter examines the assessment process for TCO applications, including eligibility, review and gazettal, the decision review process and complaints management.

Introduction

3.1 As outlined earlier, to guide the assessment process and to help assure compliance with legislative requirements, Customs has developed a practice statement, which is available on its website, and a range of internal guidance documents for its officers.

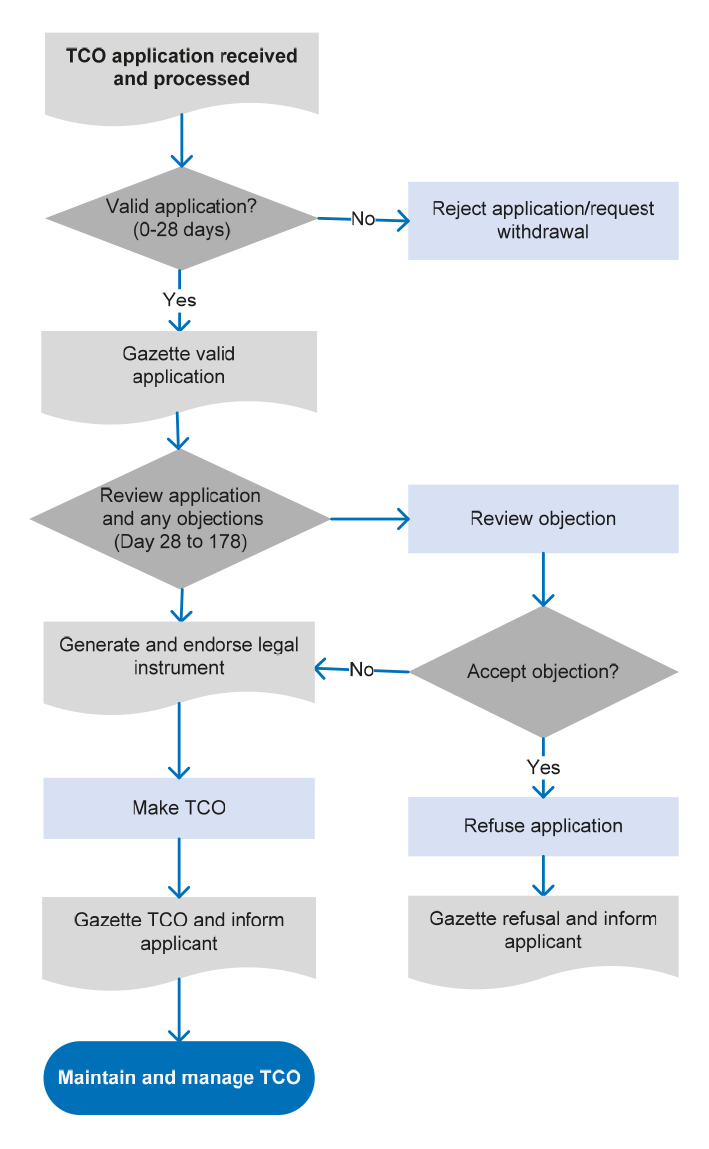

3.2 The process for assessing applications for a TCO is outlined in Figure 3.1 (on the following page). Broadly, this involves Customs officers receiving and registering applications, completing an eligibility assessment, publishing relevant information in the Gazette, managing any objections to the application, determining whether or not a TCO should be made, notifying the applicant and gazetting the decision. All of these processes are subject to either internal review, appeal to the AAT, or both.54

3.3 The ANAO examined the processes established by Customs to assess applications for, and objections to, a TCO. A sample of 10 per cent (282) of all TCO applications lodged between 18 March 2011 and 18 March 2014, which included 264 applications for new TCOs, were reviewed by the ANAO.

Figure 3.1: Tariff Concession Order application assessment process

Source: ANAO analysis of Customs information.

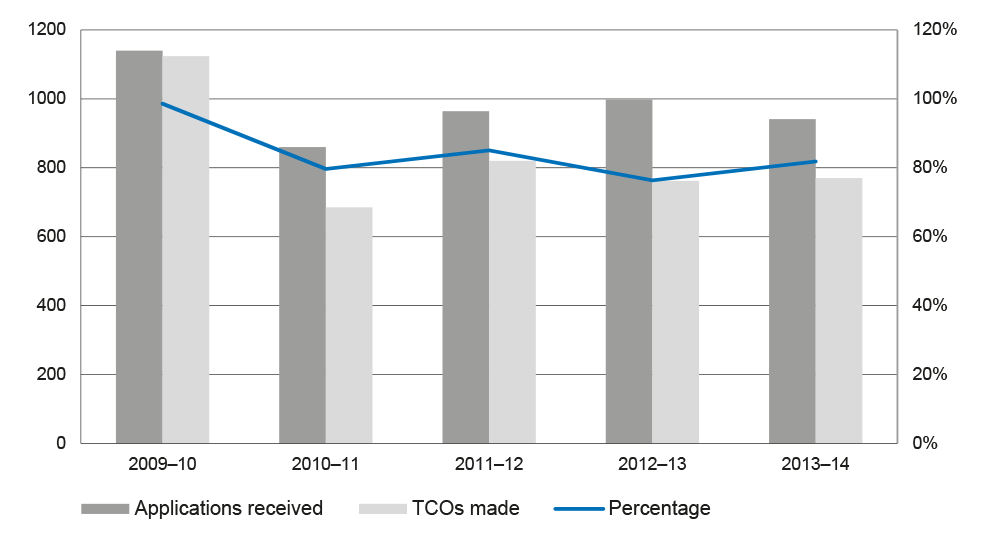

3.4 On average, over the last four years, Customs has received 940 applications for a TCO each year, of which 82 per cent (774) were made. Applications and TCOs made by year are provided in Figure 3.2.

Figure 3.2: Tariff Concession Order applications and orders made for the period 2010–14

Source: ANAO analysis of Customs information.

Receipt of applications

3.5 A feature of the TCS is the importance of the date on which the application is lodged, as a TCO is considered to have come into effect on the date of lodgement rather than the date it was made. Customs documents the receipt of a TCO application by:

- creating a record of the receipt in TARCON;

- creating a hard copy file; and

- acknowledging the receipt of the application.

3.6 The ANAO’s analysis of its sample of 264 TCO applications found that a confirmation of receipt email was generally provided within one day of lodgement, followed by an official receipt by letter, on average, seven days after the application was received. Customs advised the ANAO in November 2014 that it has since updated its processes and now only sends responses to applicants by email.

3.7 Relevant information from the application is also manually entered into TARCON. An online lodgement system would facilitate a reduction in workload, reduce the risk of user input error, and provide additional assurance over information used for decision-making. However, any decision to move away from the current manual process would be a matter for Customs Executive and need to be informed by a cost and benefit analysis.

Assessment of applications

3.8 Customs has a two-stage assessment and decision-making process covering:

- An eligibility assessment (0–28 days) that includes:

- risk assessment of the application;

- local manufacturer searches conducted by the applicant or prescribed organisation;

- description of the TCO and tariff advice; and

- legislated timeframes of assessment.

- Gazettal and review period (28–178 days) that includes:

- local manufacturer contact initiated by Customs; and

- objections by local manufacturers.

Eligibility assessment (0–28 days)

3.9 Once receipted, Customs officers assess applications against a pre-screening checklist. The purpose of the pre-screening checklist is to satisfy the legislated eligibility requirements of a TCO, confirming that the:

- application has been made on the correct form that has been signed and dated;