Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of the Radiation Oncology Health Program Grants Scheme

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Health's and the Department of Human Services' administration of the Radiation Oncology Health Program Grants Scheme.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Radiation therapy is a treatment for cancer which employs targeted doses of radiation to kill cancer cells.

2. In 1988, the Commonwealth introduced the Radiation Oncology Health Program Grants Scheme (the ROHPG Scheme or Scheme) to fund radiation oncology equipment. The Scheme is administered by the Department of Health (Health) and the Department of Human Services (Human Services), and has been operating continuously since its introduction. The objectives of the Scheme are: to improve health outcomes for cancer patients; increase access to radiation oncology services; improve equity of access for cancer patients; and ensure the highest quality and safety of radiation oncology services.1 The Scheme aims to achieve these objectives by reimbursing radiation oncology facilities for a proportion of their capital costs incurred in delivering radiation therapy services.

3. While a number of reviews into the radiation oncology sector have resulted in refinements to specific aspects the Scheme, the overall program design has not changed since 1988.

Audit objective and criteria

4. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Health’s and the Department of Human Services’ administration of the Radiation Oncology Health Program Grants Scheme.

5. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level audit criteria:

- Health has designed the program and related guidelines to support the achievement of Scheme objectives;

- Health and Human Services have effectively and efficiently administered the Scheme consistent with relevant policy, guidelines and legislation; and

- Health and Human Services have implemented appropriate program governance, risk management, performance monitoring and reporting arrangements which have informed the ongoing administration of the Scheme.

Conclusion

6. Since its introduction in 1988, the Scheme has focussed on coordinated management of the supply of radiation oncology equipment by the Commonwealth. Health’s administration of the Scheme has been based on an assessment process to inform its decision-making on the number and location of machines, and elements of the Scheme’s design have sought to influence investment decisions of service providers relating to the type of equipment purchased and the frequency with which equipment is updated or replaced. This audit highlights a number of issues with the department’s management of the Scheme which could be addressed administratively—through incremental adjustments reflecting the current program design—or by looking more fundamentally at the Scheme’s underlying program design some three decades on. Key issues requiring attention include: Scheme reimbursement rates, which have not reflected movements in key variables such as interest and exchange rates; the release of departmental information on areas of need, to help inform investment decisions; inconsistencies in Health’s approach to assessing complex applications; and the basis for assessing whether scheduled equipment capital allowances reflect the actual cost of purchasing equipment.

7. The department has advised the ANAO that it intends to review the Scheme in 2016.

Supporting findings

Program administration

8. Scheme reimbursement rates have not been updated since November 2010, and do not reflect changes in equipment costs or specifications, or movements in interest and exchange rates. In addition, key assumptions affecting the calculation of Scheme reimbursement rates, such as borrowing costs for private and public facilities, interest capitalisation methodologies, and patient throughput rates, have not been reviewed in recent years. As a consequence, the current reimbursement rates may not accurately reflect the capital costs of eligible equipment. Health advised the ANAO that it intended to address the issue of exchange rates as part of a planned review of the Scheme.

9. Health has adopted a framework for identifying which regions would benefit from additional radiation oncology capacity. However, the data which supports this assessment – the ‘areas of need’ analysis – is not released publicly. Health would help inform the investment decisions of radiation oncology organisations by releasing this information.

10. Health is responsible for assessing whether an item of equipment purchased by a facility is eligible for funding under the Scheme’s existing schedule of eligible equipment. Treatments and technologies that are not already eligible for funding under the Scheme are first assessed by the Medical Services Advisory Committee for eligibility under the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) scheme. If the treatment or technology is approved under the MBS, it is then assessed by the Technical Specifications Working Group for funding under the ROHPG Scheme. The administration of the Scheme would benefit from a clearer and more transparent framework for determining whether an item of equipment is already eligible for funding under the Scheme; or whether the application involves a genuinely novel treatment or technology and should therefore be assessed by the Medical Services Advisory Committee.

11. Health held on file a legal instrument reflecting the terms on which Scheme funding was agreed for 99 per cent of equipment reviewed by the ANAO. Health was unable to locate approval minutes evidencing the basis for the delegate’s decisions in relation to one third of currently funded items of equipment. This represents a risk exposure for the department in the event that the delegate’s decision is challenged, for example in the context of administrative review. For those decisions for which documentation was available, the delegate was generally provided with relevant advice, including the need to consider the proper use of public resources, and sufficient justification for recommendations on proposed funding.

12. The Health Program Grants legislation requires approval of both organisations and facilities before they are eligible for funding. A total of 38 organisations have been approved to receive funding under the Scheme. The department did not have documents evidencing approval for four of these organisations. There was some documentation of approval for each of the 77 facilities approved to receive funding.

13. The ANAO identified a number of inconsistencies in Health’s approach to the assessment of complex applications, relating to: multiple funding applications in the same geographic area; replacement and refurbishment of equipment; multiple sources of funding; and the imposition of bulk-billing requirements. The department should consider whether to address these and other matters raised in this audit administratively, by clarifying the guidelines, or by considering program design more fundamentally.

14. The respective roles of Health and Human Services in administering the ROHPG Scheme are clearly set out in the ‘Business Agreement relating to Medicare and Related Programmes 2012-15’.

15. Both Health and Human Services have implemented risk management procedures to identify and address a number of program administration risks associated with the Scheme. The monthly processing of payments incorporates manual intervention and legacy systems, but Human Services has assessed that it would not be economical to automate these processes unless this was done as part of broader changes to Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) systems or the ROHPG Scheme design.

Program outcomes and design

16. Health currently reports performance against one quantitative indicator focusing on the number of sites delivering radiation oncology, and a qualitative indicator focusing on expert stakeholder engagement. The indicators do not provide a complete or balanced measure of the Scheme’s performance against its stated policy objectives: to improve health outcomes for cancer patients; increase access to radiation oncology services; improve equity of access for cancer patients; and ensure the highest quality and safety of radiation oncology services.

17. The Scheme has been operating continuously for nearly three decades. In that time, the Scheme has been the subject of a number of internal and external reviews. Some of these reviews resulted in changes to specific elements of the Scheme. However, no recent review or evaluation has systematically assessed the Scheme’s outcomes against its four policy objectives. The ANAO reviewed key evaluations, reviews and other information available to Health to assess the Scheme’s performance. Overall, it is difficult to assess the specific contribution made by the Scheme as a complex range of policy settings and related programs have also influenced the sector since 1988.

18. In summary, there have been improvements in the number of facilities and machines used to treat cancer; and the number and proportion of facilities located in regional areas. This period has also seen an improvement in patient bulk-billing rates for radiotherapy and therapeutic nuclear medicine, as well as a reduction in the average age of the equipment fleet. Together, these developments are likely to have contributed to realising the Scheme’s stated policy objectives.

19. However, a number of other factors are likely to have contributed to these changes, including the incentive for public and private sector organisations to locate facilities in areas that will maximise patient throughput and return on investment; other Government policies aimed at improving the affordability of health care services; and specific funding programs for radiation oncology facilities. Consequently, the extent to which the Scheme has directly contributed to these outcomes is unclear.

20. The current approach to reimbursing facilities is based on a representative schedule of equipment prices, rather than actual purchase costs. Under current arrangements, Health is unable to provide assurance that the scheduled equipment capital allowances are being set in a manner that accurately reflects the capital costs to facilities.

21. The department has advised the ANAO that it intends to review the Scheme in 2016. That review provides an opportunity to consider issues of program design more fundamentally. In that context, there would also be merit in reviewing a number of key elements of the Scheme – the treatment of capital payments, capital allowances and pricing transparency.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 2.54 |

The ANAO recommends that, should the Department of Health continue to administer the ROHPG Scheme in accordance with current program settings, the department should:

Department of Health response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No. 2 Paragraph 3.32 |

The ANAO recommends that as part of its planned review of the ROHPG Scheme, the Department of Health review the underlying program design, including mechanisms to improve pricing transparency. Department of Health response: Agreed. |

Summary of entity responses

22. The Department of Health and the Department of Human Services provided formal comment on the proposed audit report. The summary responses are provided below, with the full responses at Appendix 1.

Department of Health

As identified in the Audit Report, the Radiation Oncology Health Program Grants (ROHPG) Scheme has been operating for nearly three decades and there has been a range of factors that have influenced the sector since its inception. Given that the ROHPG Scheme has been operating since 1988 and not reviewed since 1999, the proposed report is welcome. Furthermore, the Proposed Report recommendations are very relevant in the context of the review the Department is undertaking of the Scheme. The Department agrees with the audit report and will consider the report as part of its review.

Department of Human Services

The Department of Human Services (the department) welcomes this report.

The department is pleased to note that the ANAO found no issues with the department’s effectiveness in administering the Radiation Oncology Health Program Grants Scheme and has made no recommendations for the department’s action.

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Radiation therapy is a treatment for cancer which employs targeted doses of radiation to kill cancer cells. Although radiation oncology has high initial capital costs and requires a team of specialised practitioners, it is considered to compare well with other cancer treatment modalities such as surgery and chemotherapy, in terms of cost and treatment outcomes.2

1.2 In the 1980s, radiation therapy treatment rates for newly diagnosed cancer patients in Australia remained significantly below estimates of the clinically optimal level. For example, in 1988 the rate of newly diagnosed patients treated with radiation therapy was estimated to be as low as 32 per cent.3 In contrast, there is a body of opinion that around 50 per cent of newly diagnosed cancer patients would benefit from at least one course of radiation therapy.4 Reasons for the low rates of radiation therapy treatment given at the time included: a lack of awareness among medical students of radiation therapy as a cancer treatment; perceptions that radiation therapy was a relatively expensive form of treatment; and workforce shortages.5

1.3 Over the years, a number of barriers to patient access were also identified. As radiation therapy requires patients to have multiple treatments over a period of time and facilities have tended to be concentrated in metropolitan areas, cancer patients in regional areas have historically had significantly lower radiation therapy treatment rates compared to those living in metropolitan areas.6 Radiation oncology treatment may also involve a number of indirect costs for the patient in addition to the treatment costs. These include childcare, accommodation, and time away from work. As a consequence patients from lower socio-economic areas have had lower radiation therapy treatment rates.7

1.4 The Radiation Oncology Health Program Grants Scheme (ROHPG Scheme or the Scheme) was introduced in 1988 to fund radiation oncology equipment. The Scheme aims to improve health outcomes for cancer patients; increase access to radiation oncology services; improve equity of access for cancer patients; and ensure the highest quality and safety of radiation oncology services.8 The Scheme is administered by the Department of Health (Health) and the Department of Human Services (Human Services), and has been operating continuously since 1988.

1.5 The Scheme is designed to reimburse public and private facilities for the cost of certain types of radiation oncology equipment as treatments are delivered. Funding for each item of equipment ceases once that equipment has delivered a specific number of treatments — an arrangement which is intended to promote the timely replacement of equipment.9

1.6 Although a number of reviews into the radiation oncology sector have resulted in refinements to the Scheme, the overall program design has not changed significantly since 1988.

1.7 The radiation oncology sector has changed significantly since 1988:

- The number of megavoltage machines10 used to deliver radiation oncology services in Australia has increased substantially. In 1988, there were 46 megavoltage machines.11 By 2015, the number of linear accelerators in use had grown to around 200.

- The number of treatment facilities has increased. Prior to 1988, there were 18 public and private treatment facilities12; by 2015 the number of facilities funded under the Scheme was 76.

- The number and proportion of facilities located in regional areas has increased. In 2002, out of 44 radiation oncology facilities in Australia, only six (14 per cent) were in rural and regional areas.13 In 2015, of the 76 facilities receiving funding, 19 (or 25 per cent) were located in regional areas.14

- The financial accessibility of radiation therapy services has improved. Bulk-billing rates for radiotherapy and therapeutic nuclear medicine have increased from around 12 per cent in 1988, to nearly 70 per cent in 2015.15

- Between 2000 and 2010, the percentage of linear accelerators aged more than 10 years reduced from 14 per cent to nine percent; the percentage of linear accelerators aged between five and 10 years declined from 39 per cent to 28 per cent; and the percentage of linear accelerators aged five years or less increased from 40 per cent to 60 per cent.16

1.8 Under the Scheme, the amount that individual facilities are reimbursed for each service is determined from time to time by the Health Minister or delegate, and set out in the Scheme Guidelines (the Guidelines).17 To calculate the per-service funding amounts, Health estimates the capital cost of the machine and certain specified ancillary equipment (the capital allowance), and divides this cost by the notional number of services that each machine can deliver over its lifetime.18 For example, for the purposes of the Scheme, Health bases its calculations on a linear accelerator delivering around 82 800 services during its useful life.19

1.9 Each month, facilities are reimbursed an amount based on the number of eligible radiation oncology services delivered in the preceding month. Scheme funding ceases after the capital balance for a specific machine has been exhausted – that is, after the specified number of services have been delivered on that machine. Medicare benefits are still payable for services delivered on machines with expired capital allowances, as these represent payments for professional services rather than capital expenditure.

1.10 Private facilities are paid a higher rate of reimbursement than public facilities, as private facilities are provided with additional funding to account for the cost of borrowing to finance the purchase cost of capital equipment.20 Public facilities can receive the higher rate of reimbursement (which includes the cost of borrowing) if they can demonstrate that they have borrowed money to buy the equipment. This had not occurred in practice at the time of this audit.

1.11 In addition, radiation oncology facilities have received Commonwealth funding support from a range of other programs, including the Health and Hospitals Fund, Regional Cancer Centres initiative, and the Better Access to Radiation Oncology program.

Figure 1.1: Linear accelerator

Source: Picture taken during ANAO fieldwork visit to Canberra Hospital, October 2015.

Program Funding

1.12 The ROHPG Scheme provides ongoing funding for radiation oncology equipment through annual budget appropriations.21 Funding for the Scheme in 2014–15 was $68.5 million and associated radiation oncology MBS payments equalled $343 million. More than 400 items of equipment are currently funded under the Scheme, around half of which are megavoltage machines known as linear accelerators.22 As shown in Figure 1.2, expenditure has increased since 2007, reflecting an increase in the number of facilities and items of equipment funded under the Scheme.

Figure 1.2: Health Scheme expenditure, 2007–15

Source: Health internal budget information.

1.13 Health has estimated that the departmental cost of administering the Scheme is close to $340 000 per annum, which equates to three full time equivalent staff.23 Scheme administration by Human Services comprises approximately one full-time equivalent staff member, typically at a cost of between $100 000 and $130 000 each year.24

Legal and policy authority

1.14 The legislative basis for the Scheme is found in Part IV of the Health Insurance Act 1973 (the Act).25 The Act does not refer specifically to radiation oncology, but sets out conditions for the Minister (or delegate) to approve a broad range of Health Program Grants. The Act also requires facilities to be approved by the Minister for Health or delegate prior to receiving funding under the Scheme. Figure 1.3 outlines the relevant sections of the Act.

Figure 1.3: Legislative requirements for Scheme payment eligibility

Source: The Health Insurance Act 1973 and ROHPG Scheme Guidelines.

1.15 Eligibility criteria for the Scheme are set out in the ROHPG Scheme Guidelines, which are administered by Health and published on its website. The current Scheme Guidelines have been in place since November 2010.

1.16 The Scheme provides reimbursement for specific items of radiation oncology equipment identified in a Schedule to the Scheme guidelines.26 The eligibility of equipment for Scheme funding is determined by an expert committee convened by Health27, and may be referred to the Medical Services Advisory Committee (MSAC) if the technique or technology associated with the equipment has not been previously approved for funding under the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS).

1.17 Section 131 of the Act provides that the Minister for Health may delegate powers under the Act. The Scheme is administered by the Medical Specialist Services Branch in Health, within the Medical Benefits Division. Successive Ministers have delegated approval of Scheme funding to the Assistant Secretary, Medical Specialist Services Branch. Applications for funding are assessed by delegates in Health on a continuous basis. The delegate also approves monthly payments to facilities.

Audit approach

1.18 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Health’s and the Department of Human Services’ administration of the Radiation Oncology Health Program Grants Scheme (the Scheme).

1.19 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level audit criteria:

- Health has designed the program and related guidelines to support the achievement of Scheme objectives;

- Health and Human Services have effectively and efficiently administered the Scheme consistent with relevant policy, guidelines and legislation; and

- Health and Human Services have implemented appropriate program governance, risk management, performance monitoring and reporting arrangements which have informed the ongoing administration of the Scheme.

1.20 Although the Scheme has been in continuous operation since 1988, the audit’s focus was on the more recent administration of the Scheme from 2008–09 to 2015.28 While the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) funds Scheme payments associated with the treatment of eligible DVA clients, its role in the administration of the Scheme was not a focus of the audit.

1.21 Audit field work was conducted in Health and Human Services’ national offices in Canberra, and in Human Services’ state office in Western Australia. Field work included: examination of departmental records; observation of payment processing; and interviews with agency staff and key stakeholders in the radiation oncology sector. The ANAO also received stakeholder feedback through its citizens’ input portal.29

1.22 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO’s auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $435 519.

2. Program Administration

Areas examined

This chapter examines the Department of Health’s (Health) and the Department of Human Services’ (Human Services) administration of the Scheme, in particular whether:

- Health has implemented a timely process for reviewing and updating the Scheme reimbursement rates;

- Health has funded facilities where they are most needed;

- Health has clear arrangements in place to assess the funding eligibility of equipment;

- the delegate’s decisions are appropriately documented;

- Health has applied the Scheme Guidelines consistently; and

- Health and Human Services have effective arrangements to administer payments under the Scheme.

Conclusion

The ANAO identified a number of issues which would merit review should Health continue to administer the Scheme in accordance with current settings. In particular, the department should periodically review and document reimbursement rates and the underlying variables that inform the calculation of those rates, including interest and exchange rates; provide greater transparency regarding the geographic areas of need to inform stakeholder investment decisions; and clarify guidance relating to eligibility, competing applications, and upgrading and refurbishment of equipment.

Areas for improvement

The department should consider whether to address the issues raised in this audit administratively, by clarifying the guidelines, or by considering program design issues more fundamentally.

Does Health keep Scheme reimbursement rates under review?

Scheme reimbursement rates have not been updated since November 2010, and do not reflect changes in equipment costs or specifications, or movements in interest and exchange rates. In addition, key assumptions affecting the calculation of Scheme reimbursement rates, such as borrowing costs for private and public facilities, interest capitalisation methodologies, and patient throughput rates, have not been reviewed in recent years. As a consequence, the current reimbursement rates may not accurately reflect the capital costs of eligible equipment. Health advised the ANAO that it intended to address the issue of exchange rates as part of a planned review of the Scheme.

2.1 Reimbursement rates are set out in the Scheme Guidelines. In broad terms, the reimbursement per service is equal to the estimated cost of the item of equipment, divided by the estimated number of services that the machine will perform over its useful life. Private facilities are also reimbursed at higher rates to reflect their costs of borrowing. Figure 2.1 shows how reimbursement rates are calculated.

Figure 2.1: Calculation of Scheduled reimbursement rates

Note a: Public facilities are also entitled to the Scheme rate which includes the cost of borrowing if they can demonstrate that they have borrowed money to buy the equipment. In practice, the higher capital allowances that include a cost of borrowing component have only been accessed by private providers.

Source: Health approval of reimbursement rates, September 2010.

2.2 The cost of the specific items of equipment is estimated by Health’s Technical Specifications Working Group. Once the base specifications and vendor prices for each item of eligible equipment have been set, the capital allowances for each item are determined based on:

- the exchange rate of the Australian dollar against the US dollar30;

- the Reserve Bank of Australia’s 10 year bond rate (relevant to calculating capital allowances that include borrowing costs);

- building index/shielding allowance (for linear accelerators only)31; and

- the type and average cost of the equipment.

2.3 The current Scheme reimbursement rates have been in place since November 2010, notwithstanding significant movements in exchange and interest rates.

2.4 The US-dollar exchange rate used to calculate the capital allowances in November 2010 was around 90 cents, whereas in March 2016 it was around 75 cents.32 This has reduced the purchasing power of both public and private facilities.

2.5 Similarly, the 10-year government bond rate used to calculate borrowing costs for private facilities in November 2010 was 5.63 per cent, but since then has more than halved, to around 2.6 per cent (as at March 2016).33 This results in a relatively higher level of reimbursement being made to private facilities than would be the case if the Scheme rates were updated.

2.6 In August 2010, the Technical Specifications Working Group noted the impact of exchange rates on capital costs and resolved to undertake annual reviews of the rates wherever possible. Health was unable to provide a rationale for why the rates had not been updated since November 2010, and advised the ANAO that it intended to address this issue as part of its planned review of the Scheme.

|

Box 1: Key assumptions driving calculation of Scheme reimbursement rates |

|

There are a number of underlying assumptions impacting on the calculation of Scheme reimbursement rates, which have not been reviewed in recent years:

Health has not undertaken any analysis of the borrowing costs faced by private radiation oncology facilities. There is also no clear rationale for excluding borrowing costs for public facilities. Reviews of the Scheme have noted that ‘there is no evidence to suggest that public hospitals acquire equipment at a lower purchase cost or with a lower cost of borrowing than the private sector’.34 Health advised the ANAO that the exclusion of borrowing costs for public facilities only is not based on any particular evidence regarding their cost of borrowing; but rather, that private facilities rely on a few defined revenue sources, compared to public facilities, which are able to access a wider range of funding from their respective state governments and the Commonwealth. |

Has Health funded facilities where they are most needed?

Health has adopted a framework for identifying which regions would benefit from additional radiation oncology capacity. However, the data which supports this assessment – the ‘areas of need’ analysis – is not released publicly. Health would help inform the investment decisions of radiation oncology organisations by releasing this information.

2.7 Radiation oncology treatments are often delivered in repeated doses over short timeframes, which requires patients to be able to attend the facility regularly during their treatment period. Funding provided by the Scheme is intended to provide reasonable access to patients by aligning the location of radiation oncology facilities with population distributions throughout Australia.

2.8 When assessing funding applications for new facilities (and applications for the expansion of capacity in existing facilities), the department assesses regional need through its ‘areas of need’ analysis, which is based on:

- regional cancer incidence projections developed by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW);

- projected populations throughout Australia;

- optimal radiation oncology utilisation rates; and

- the notional life and throughput capacity of the existing fleet of linear accelerators.

2.9 This information is used to calculate the shortfall (or oversupply) of linear accelerators needed to treat a population in a given area. As of June 2015, areas of need were projected to 2024. Health’s projections for the number of linear accelerators required in each area of need as at 2016 are included at Appendix 2.

2.10 Health’s assessment of geographical areas of need is also supplemented by stakeholder consultation on individual applications. The Scheme Guidelines indicate that in assessing private applications, Health will seek comment from relevant state health departments and cancer councils. For applications from public organisations, Health may seek comment from potentially affected private providers, other affected parties and the community more generally.35

2.11 The areas of need analysis provides a framework for identifying geographic areas of need and allocating funding. At present, this analysis is not publicly available to the radiation oncology sector, and there would be benefit in releasing this information to help inform investment decisions in the sector. The Scheme’s underlying design is to use public funding as a mechanism for managing the supply of radiation oncology services in areas of need. In effect, public funding is assumed to be a key incentive for the provision of services in those areas.36 Under the Scheme’s current settings, releasing information on areas of need would alert providers to the regions in which Scheme funding is likely to be available in the future. It would also be of benefit if a more market-driven approach to managing the supply of machines were adopted, as it would provide additional information to potential providers about local demand and potential market opportunities. The Scheme’s design is discussed further in paragraph 2.24 and Chapter 3. Health confirmed that the areas of need analysis is held confidentially by the department, but acknowledged during the course of the audit that there would be value in making this information publicly available.

2.12 Figure 2.2 shows a chart developed by the ANAO to illustrate the Health Planning Regions which, as of 2016, have been identified by Health as requiring additional linear accelerators.

Figure 2.2: Health projected areas of need by Health Planning Region as at 2016 [click for larger version]

Note: A negative number represents an oversupply of linear accelerators. A positive number indicates an undersupply and therefore an area of need. See Appendix 2.

Source: ANAO analysis of Health internal planning documentation.

Are clear arrangements in place to assess funding eligibility of radiation oncology equipment?

Health is responsible for assessing whether an item of equipment purchased by a facility is eligible for funding under the Scheme’s existing schedule of eligible equipment. Treatments and technologies that are not already eligible for funding under the Scheme are first assessed by the Medical Services Advisory Committee for eligibility under the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) scheme. If the treatment or technology is approved under the MBS, it is then assessed by the Technical Specifications Working Group for funding under the ROHPG Scheme. The administration of the Scheme would benefit from a clearer and more transparent framework for determining whether an item of equipment is already eligible for funding under the Scheme; or whether the application involves a genuinely novel treatment or technology and should therefore be assessed by the Medical Services Advisory Committee.

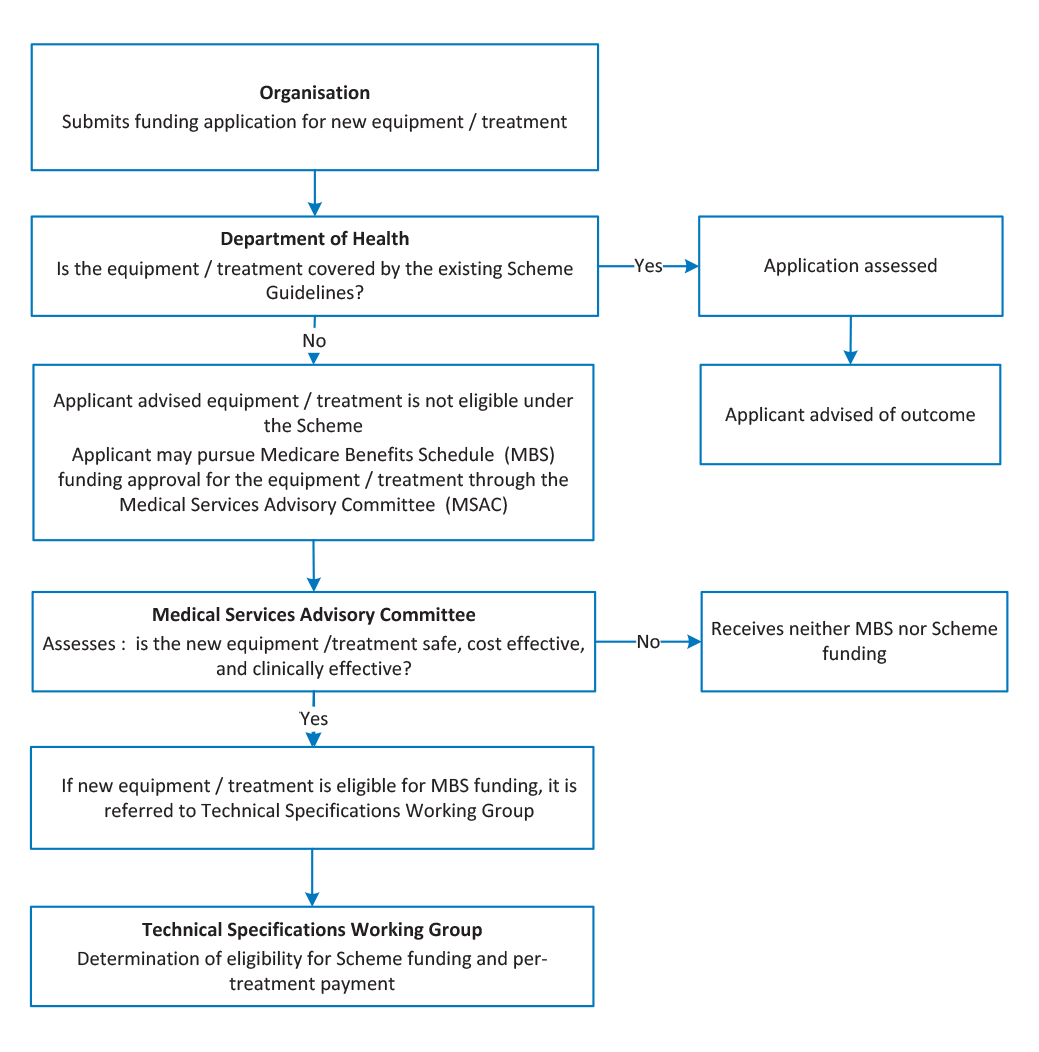

2.13 The Scheme Guidelines specify which items of equipment are eligible for funding. For equipment to be funded through the Scheme, the treatments that it delivers must first be listed on the Medicare Benefits Schedule. Figure 2.3 shows the process for assessing new radiation oncology treatments and technologies for funding under the MBS and ROHPG Schemes.

Figure 2.3: Assessment of radiation oncology treatments and technologies

Note: The Technical Specifications Working Group has not met since 2010.

Source: Health internal documentation.

2.14 Health advised the ANAO that the categories of equipment eligible for Scheme funding are deliberately broad so as to accommodate a range of different specifications. This reduces the need for prescriptive or technical schedules, as well as the frequency with which the schedule needs to be updated. However, this sometimes requires officers within Health to make difficult judgments about whether particular items of equipment are covered by the existing schedule of eligible equipment.

2.15 It is relatively rare for a new technology to be added to the list of eligible equipment under the Scheme, and Health’s responsiveness to reviewing new treatment technologies and determining eligibility under the Scheme has been raised with the department by stakeholders. In particular, stakeholders have argued that there is not a clear process for Health to decide which treatments and technologies are truly ‘novel’ (and would therefore require approval by the Medical Services Advisory Committee, see Figure 2.3); and those which are developments of existing technology and should therefore be approved for funding under the existing ROHPG Scheme categories.37 Stakeholders have also been critical of Medical Services Advisory Committee processes, and in June 2014 Health engaged a consultant to provide advice on how those processes could be improved. Health advised the ANAO that consultation on potential changes to Medical Services Advisory Committee processes was likely to commence in 2016.

2.16 The future role of the Medical Services Advisory Committee, and in particular its role as part of the broader process for assessing the eligibility of equipment for funding under the ROHPG Scheme, should be considered further by the department. Whether to publicly fund new equipment, treatments and technologies are key decisions under the ROHPG Scheme, and clarity in assessment and decision-making processes can provide confidence to all stakeholders that such judgments are soundly-based. The administration of the Scheme would benefit from a clearer and more transparent framework for determining whether a given item of equipment is already eligible for funding under the ROHPG Scheme; or whether the application involves a genuinely novel treatment or technology and should therefore be referred to the Medical Services Advisory Committee for assessment.

Are the Health delegate’s decisions appropriately documented?

Health held on file a legal instrument reflecting the terms on which Scheme funding was agreed for 99 per cent of equipment reviewed by the ANAO. Health was unable to locate approval minutes evidencing the basis for the delegate’s decisions in relation to one third of currently funded items of equipment. This represents a risk exposure for the department in the event that the delegate’s decision is challenged, for example in the context of administrative review. For those decisions for which documentation was available, the delegate was generally provided with relevant advice, including the need to consider the proper use of public resources, and sufficient justification for recommendations on proposed funding.

The Health Program Grants legislation requires approval of both organisations and facilities before they are eligible for funding. A total of 38 organisations have been approved to receive funding under the Scheme. The department did not have documents evidencing approval for four of these organisations. There was some documentation of approval for each of the 77 facilities approved to receive funding.

2.17 The ANAO reviewed Health records relating to some 400 items of currently funded equipment38 to determine whether:

- relevant documentation was retained on file to evidence delegate approvals39, financial approvals, conditions of payment and supporting analysis;

- the assessment criteria and approval conditions were consistently applied; and

- eligibility requirements for delegate approval of organisations and facilities had been met.

2.18 Table 2.1 details the results of the ANAO’s review.

Table 2.1: Results of ANAO review—Scheme approval documentation

|

Documentation checked |

Purpose |

Result |

|

Legal instrumentsa |

Formalises the amounts to be paid for equipment and conditions of payment. |

Almost 99% of equipment had a legal instrument on file. |

|

Approval minutesb |

Documents approval by a delegate under the HIAc, the matters taken into account by the delegate, and assessment of whether funding decisions represented a proper use of Commonwealth resources. |

Health was unable to locate signed delegate approval minutes for one third of equipment currently funded under the Scheme. |

|

Approval under:

|

Required under the Guidelines to establish eligibility for Scheme funding:

|

There was no documentary evidence of section 40 approval for four organisations (of a total of 38 organisations). All 77 facilities had an approval under section 41 on file. This approval is re-made each time a new piece of equipment is added to the relevant organisation’s legal instrument. |

Note a: The advice to the delegate includes draft legal instruments, which once executed, provide evidence of the conditions attached to the funding. In practice, the legal instruments for an organisation are re-made each time a new facility or item of equipment for that organisation is added or replaced. Current legal instruments were accepted as evidence for all items of equipment listed.

Note b: The approval minute is the mechanism through which the delegate records their decision that the funding represents an appropriate use of Commonwealth resources; and the matters taken into account in reaching that decision.

Note c: The HIA is the Health Insurance Act 1973.

Source: ANAO analysis of Health records.

2.19 Health’s delegate is required to review funding applications to assess whether approving funding under the Scheme represents a proper use of Commonwealth resources.40 Of the 212 decision minutes available for ANAO review, the majority (79 per cent) of decisions under the FMA Act included such advice to the delegate. All 20 approval minutes signed under the PGPA Act included this advice. These statistics indicate that the department’s consistency in advising the delegate of the need to assess the proper use of resources has improved over time as all approvals since July 2014 have incorporated this information.

Records management

2.20 During the course of the audit, Health experienced difficulties locating relevant documents relating to organisations, facilities and equipment approved some years or decades ago. In particular, signed delegate approvals could not be located by Health in relation to one-third of currently funded equipment. Approval minutes are intended to document the exercise of the delegate’s powers under the Health Insurance Act 1973, the delegate’s assessment of ‘proper use’, and the matters taken into account by the delegate in reaching their decision. Health’s inability to locate these documents represents a potential risk exposure for the department, for example in the context of a request for internal or administrative review of a delegate’s decision. Shortcomings in Health’s records management were also identified in a number of recent ANAO performance audits.41

Has Health applied the Scheme Guidelines consistently to assess complex applications?

The ANAO identified a number of inconsistencies in Health’s approach to the assessment of complex applications, relating to: multiple funding applications in the same geographic area; replacement and refurbishment of equipment; multiple sources of funding; and the imposition of bulk-billing requirements. The department should consider whether to address these and other matters raised in this audit administratively, by clarifying the guidelines, or by considering program design more fundamentally.

Competing applications

2.21 Funding applications under the Scheme are assessed by Health on a continuous case-by-case basis. The Scheme Guidelines do not document an approach for managing situations where funding applications are received from more than one provider in relation to the same geographic area. Health has taken an ad hoc approach in its management of such ‘competing applications’. Some examples of approaches taken by Health included:

- the department convened an expert panel to decide which of two applications should be preferred;

- the delegate rejected both applications, but suggested an alternative site to one of the applicants;

- despite the department’s areas of need analysis identifying no shortfall in linear accelerators for some years to come, the department approved two facilities for the same region on the basis that they could take their own commercial risks. The department advised each facility of the existence of a competing application and one facility then withdrew;

- the delegate refused an application to establish a new private facility in an identified area of need, on the basis of its consultation with the relevant state department of health, which advised it intended to apply for funding for a new public facility in the same area; and

- one funding application for a new facility was chosen over another on the basis of the department having previously awarded it funding under the Health and Hospitals Fund (HHF)42 program.

|

Case study 1. Competing applications |

|

Competing public/private applications In October 2006, the department received a funding application for a new private radiation oncology facility. Consistent with the Scheme Guidelines, the department consulted the state health department and state cancer council. While the cancer council supported the application based on the need for services in the area, the state health department opposed it in light of its own impending application in the same area (which was submitted six months after the private facility’s application). The delegate approved Scheme funding for the state health department’s facility and refused the private facility application. The private applicant subsequently applied for a smaller facility in the same region and the state health department again opposed it on the basis that this would result in oversupply; while also flagging its intention to increase the capacity of its own facility. After extensive consultation between the private facility and the state health department, the state health department decided to support the private application, which was approved in February 2010. Competing private applications In late 2012, two private facilities each applied to establish new facilities in the same region. The department assessed the need for additional services in the area to be low, due to nearby facilities which would sufficiently service the population. Both organisations were refused and given the opportunity to provide more information. The delegate subsequently approved both applications, reasoning that there would be minimal financial risk to the Commonwealth but a high risk to each organisation. The delegate’s notes indicated that Health had ‘limited capacity’ to assess local need, and as the two private facilities deemed the area to be a sensible investment, considered this sufficient indication that it was an area of need. |

2.22 The issue of competing applications is not addressed in the Scheme Guidelines, and there is no formal guidance to assist staff. Health advised the ANAO that while there is no formal guidance, staff can draw on earlier precedents and examples (contained within file notes and decision minutes) and can consult with colleagues and supervisors to inform their thinking.

2.23 Health also advised the ANAO that the receipt of competing applications is becoming more common, and in some areas this has led to oversupply. This has occurred notwithstanding the Scheme’s underlying premise that the supply of services can be managed through the use of public funding. As the number of facilities increases and the number of identified areas of need decreases, there is a risk that the number of competing applications will increase. If Health chooses to continue administering the Scheme along current lines, there would be benefit in developing formal guidance for the assessment of competing applications.

2.24 However, inconsistencies in Health’s approach to assessing competing facility applications, and the oversupply of services in some areas, suggests that the current program design—based on the use of publicly-funded financial incentives to manage supply—may warrant review some three decades after the Scheme was introduced. The case study above, relating to Health’s handling of competing private applications, indicates that the department has at times recognised limitations in its capacity to assess local need, and has allowed competing providers to make risk-based investment decisions based on their understanding of local demand. This is closer to a market-based approach. This matter is discussed further in Chapter 3.

Replacement and refurbishment of equipment

2.25 The Scheme Guidelines allow funding to be approved for new or refurbished radiation oncology equipment only.43 Stakeholder feedback indicated a lack of clarity surrounding what constitutes refurbishment, particularly with regards to planning systems. Unlike linear accelerators and other eligible equipment, a planning system is effectively a sophisticated desktop computer which undergoes regular hardware and software updates, similar to other IT infrastructure.

2.26 The Technical Specifications Working Group considered the issue of upgrading planning systems in early 2011. At that time, the delegate approved temporary funding for facilities that had completed substantive planning system upgrades, with a view to resolving the issue by the end of 2011. As at late 2015, no resolution to this issue had been achieved. As with the issue of competing applications, the department could address this matter administratively, by clarifying the guidelines, or by considering program design more fundamentally, recognising that well-designed incentives can help reduce the overall cost to the Commonwealth. For example, where providers are faced with decisions whether to replace equipment or refurbish it so as to maximise its economic life and clinical utility, they will have regard to relevant financial incentives. Poorly designed or unclear incentives can distort decision-making around the best use of capital.

Multiple funding sources

2.27 A number of related initiatives have been used to provide Commonwealth and/or state funding for radiation oncology, including: the Health and Hospitals Fund, Better Access to Radiation Oncology, and the Regional Cancer Centres initiative. The Scheme Guidelines state that equipment funded through other Commonwealth funding measures is generally not eligible for funding under the ROHPG Scheme.44

2.28 The ANAO identified several funding applications where facilities had received funding from other sources and the department was required to assess whether the applicant was eligible for funding under the ROHPG Scheme. Alternative funding sources and intended allocations have not always been clear to Health staff assessing applications, particularly when funds are sourced from both state and Commonwealth initiatives. This has led to some inconsistencies in information provided to the Health delegate, and decision making for Scheme funding. For example, three situations were identified where both a state and the Commonwealth contributed to a project and it was unclear to Health assessment staff which of these contributions funded the radiation oncology equipment. In one case, an application for ROHPG Scheme funding was rejected, but in the other two, applications were approved.

2.29 Health advised that assessment staff liaise with relevant areas in the department and with state and territory health departments when an application involves funding provided through another mechanism, however, this checking process is not formally documented.

Bulk-billing requirements

2.30 When considering a funding application under the Scheme, the delegate is able to impose conditions relating to the proportion of patients that are bulk-billed.45 However, Health has not established a clear framework for determining the circumstances in which these requirements should be imposed, which has led to inconsistencies between facilities in the application of the condition. For currently funded equipment, bulk-billing requirements were imposed in relation to 17 per cent of equipment funded in public facilities; and 39 per cent of equipment funded in private facilities.

2.31 Health’s advice to the delegate in seeking approval for the current Scheme Guidelines indicates that the optional bulk-billing condition is only imposed on organisations which specify in their application that they will bill patients in this way. The department also does not routinely check that bulk-billing conditions are adhered to, except ‘from time to time, [when] the statistics area within the Division provides information on billing patterns, including bulk-billing rates’.

2.32 A more clearly articulated policy objective, supported by appropriate internal guidance, would support a more consistent and outcome-focused approach to the imposition of bulk-billing requirements on facilities.

Documentation requested for new facilities

2.33 The current Scheme Guidelines indicate that applicants for new public or private facilities are required to provide ‘a project plan and timeframe for the establishment of the new service’.46 The ANAO examined all applications for new facilities held on Health files since November 2010 and found that only six out of 1747 new facilities provided information meeting this requirement.

2.34 The Scheme Guidelines also include a requirement for private applicants to provide a ‘fully costed and independently audited business case that explains what will be achieved by the project over a 10 year period’.48 Health records indicate that the requirement for an audited business case were originally introduced because:

- once a facility was approved, Scheme funds were nominally ‘set aside’ for that facility, as part of the process for managing funding commitments against available appropriations;

- private facilities are not necessarily part of the broader state health planning process (although they can be expected to conduct due diligence to inform their investment plans in a region); and

- establishing the genuine commercial intentions of the applicant was considered to reduce the risk of providers lodging ‘placeholder’ applications with the purpose of blocking competitors from the same location.

2.35 The ANAO’s review of a sample of applications found no evidence of documentation provided by private applicants that would meet this requirement, nor any reference to this requirement in the prescribed application forms. If the current design of the Scheme is retained, Health should review the Scheme Guidelines to avoid unnecessary regulatory requirements for applicants.

2.36 More fundamentally, these documentary requirements are linked to the current program design, which focuses on co-ordinated supply management. From that perspective, they are intended to provide assurance to the department that its decisions on the management of supply are well founded. The evidence that these requirements are no longer actively relied upon in the Scheme’s administration further underlines the benefit of reviewing the Scheme’s design.

Do Health and Human Services have clearly defined responsibilities in relation to the Scheme’s administration?

The respective roles of Health and Human Services in administering the ROHPG Scheme are clearly set out in the ‘Business Agreement relating to Medicare and Related Programmes 2012-15’.

2.37 Schedule A of the Business Agreement between Health and Human Services relates to Medicare and Related Programmes. Attachment 3 of the Schedule relates specifically to ‘Health Programme Grants for Radiation Oncology Services’.49

2.38 The attachment includes specific provisions intended to document the roles and responsibilities of the parties to the Agreement. In particular, it documents responsibilities for assessment processes and approvals (Health responsibilities), and payment arrangements (a Human Services responsibility). It also documents key processes for communication between the departments and providers.

2.39 Human Services administers Scheme payments through its program area in its National Office, which undertakes high level coordination and liaison with Health, and its state office in Western Australia (WA), which undertakes processing activities. The Scheme accounts for a small portion of the overall workload of the relevant Human Services branches, which are also responsible for a range of other functions relating to the Medicare program. Scheme administration by Human Services comprises approximately one full-time equivalent staff member for operations undertaken in the program area and the WA state office at a typical cost of between $100 000 and $130 000 in departmental expenses.50

2.40 The process for approving and making monthly Scheme payments is set out in Figure 2.4.

Figure 2.4: Scheme payment process

Source: Human Services process maps.

2.41 Human Services also makes six-monthly Networked Information System (NIS) payments, which are calculated by Health and are based on the number of networked linear accelerators in operation at a facility. Human Services does not undertake any data entry or data manipulation associated with this task.

Are appropriate risk management and control frameworks in place?

Both Health and Human Services have implemented risk management procedures to identify and address a number of program administration risks associated with the Scheme. The monthly processing of payments incorporates manual intervention and legacy systems, but Human Services has assessed that it would not be economical to automate these processes unless this was done as part of broader changes to Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) systems or the ROHPG Scheme design.

Risk management

2.42 Commonwealth entities are required to establish and maintain an appropriate system of risk management, oversight and internal control.51 The ANAO examined the risk management practices of Health and Human Services, including their approach to allocating risks between the departments.

Health

2.43 The Scheme represents a relatively small proportion of funding administered by each department. Health’s 2014–15 Business Plan identifies high-level risks for the Medical Benefits Division (which administers the Scheme within Health), and a standard set of mitigation measures relating to a number of identified administrative risks. These documents are provided to the delegate when approving funding for equipment under the ROHPG Scheme. Health’s risk mitigation processes are largely focussed on reducing specific payment risks arising from human error. These include monthly pre-payment checks on payment reports provided by Human Services; and verification of the six-monthly Networked Information Systems payments.

Human Services

2.44 In mid-2015, Human Services finalised risk documentation, including a Scheme Compliance Assessment which rated the Scheme’s risk as low, based on the materiality of funds administered under the Scheme and lack of identified non-compliance. The department also developed a Risk Management (Including Payment Accuracy) Plan which identifies risks associated with Human Services’ administration of payments and recommended mitigation actions relating to the Scheme.

2.45 Health and Human Services advised the ANAO that their risk management arrangements are supplemented by regular meetings at the Senior Executive level, which provide an opportunity for the departments to discuss any risk management issues that may arise, including in relation to the Scheme.

Payment controls

2.46 Human Services maintains a database containing the details of all facilities and equipment funded under the Scheme, its outstanding capital balance, relevant MBS services delivered using that equipment, and the per-service reimbursement rate. Human Services updates the database as required, based on advice from Health.

2.47 Each month, Human Services’ WA team processes payments for both public and private facilities based on the number of MBS eligible services that have been delivered on each piece of funded equipment.

2.48 ROHPG Scheme payments to public facilities are based on an automated ‘sweep’ of Medicare claims from the previous month.52 The system automatically checks to ensure ROHPG claims match available MBS patient data.53

2.49 In contrast, private facilities generate a separate data file which is used as the basis for their Scheme payment claims. These files are submitted by individual facilities via secure email during the first week of each month.54 These files are manually checked by Human Services staff and uploaded to the Medicare mainframe. As at mid-2015, around 35 private facilities were claiming ROHPG payments each month. The Human Services Information Technology area then produces three reports: a private facility payment report; a public facility payment report; and a private facility error report. Private facilities use the error report to correct their claims and re-lodge them the following month.

2.50 The payment reports are used to populate a payment summary spreadsheet,which is checked by Human Services and forwarded to Health. Health extracts the payment information that is relevant to the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) and provides it to DVA for delegate approval.55 The Health and DVA delegates each approve their respective payments in writing, authorise the transfer of funds to Human Services, and notify Human Services that the funds are available for disbursement to the facilities.56

2.51 Once the funds are available, Human Services’ Finance area makes payments to facilities, and the WA team sends out payment reports and confirmation letters to each facility.

2.52 Many of the electronic systems used by Human Services WA to process Scheme payments are legacy systems and a degree of manual intervention is required. The ANAO did not undertake transaction testing of the payments made by Human Services as part of this audit. While there would be scope to realise efficiencies by automating payment processing, Human Services advised that it would not be economical to do so unless the changes were incorporated as part of broader reforms of either the MBS System or the ROHPG Scheme.

Summary

2.53 The ANAO identified a number of issues relating to Health’s management of the Scheme which would merit review should Health continue to administer the Scheme in accordance with current settings. Those issues are addressed in Recommendation 1. An alternative approach, discussed above and in the following chapter, is to consider program design issues more fundamentally.

Recommendation No.1

2.54 The ANAO recommends that, should the Department of Health continue to administer the ROHPG Scheme in accordance with current program settings, the department should:

- periodically review and document reimbursement rates and the underlying variables that inform the calculation of those rates, including interest rates and exchange rates;

- publish its areas of need analysis to inform stakeholder investment decisions; and

- clarify guidance relating to competing applications, the replacement and refurbishment of equipment, multiple funding sources, and the imposition of bulk-billing conditions.

Department of Health response: Agreed.

3. Program outcomes and design

Areas examined

This chapter examines the Scheme’s performance framework; the outcomes of the Scheme since it commenced operation nearly three decades ago; and a number of underlying design issues.

Conclusion

The Scheme’s performance indicators do not provide a complete or balanced measure of the Scheme’s performance against its stated policy objectives: to improve health outcomes for cancer patients; increase access to radiation oncology services; improve equity of access for cancer patients; and ensure the highest quality and safety of radiation oncology services.57

The Scheme has been operating continuously for nearly three decades. In that time, the Scheme has been the subject of a number of internal and external reviews. Some of these reviews have resulted in changes to specific elements of the Scheme. However, no recent review or evaluation has systematically assessed the Scheme’s outcomes against its four policy objectives. The ANAO reviewed key evaluations, reviews and other information available to Health to assess the Scheme’s performance. Overall, it is difficult to assess the specific contribution made by the Scheme as a complex range of policy settings and related programs have also influenced the sector since 1988.

The department has advised the ANAO that it intends to review the Scheme in 2016. That review provides an opportunity to consider issues of program design more fundamentally. In that context, there would also be merit in reviewing a number of key elements of the Scheme: the treatment of capital payments, capital allowances and pricing transparency.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO recommends that as part of its planned review of the Scheme, the Department of Health review the underlying program design.

Does Health’s performance framework provide a basis for assessing Scheme outcomes against policy objectives?

Health currently reports performance against one quantitative indicator focusing on the number of sites delivering radiation oncology, and a qualitative indicator focusing on expert stakeholder engagement. The indicators do not provide a complete or balanced measure of the Scheme’s performance against its stated policy objectives: to improve health outcomes for cancer patients; increase access to radiation oncology services; improve equity of access for cancer patients; and ensure the highest quality and safety of radiation oncology services.

External performance reporting

3.1 The Scheme’s policy objectives are: to improve health outcomes for cancer patients; increase access to radiation oncology services; improve equity of access for cancer patients; and ensure the highest quality and safety of radiation oncology services. Health publicly reports outcomes for radiation oncology measures under departmental Outcome 3: Access to Medical and Dental Services.

3.2 Health’s 2014–15 Annual Report reports on one quantitative key performance indicator for the Scheme, access to quality radiation oncology services, which relates to the number of sites delivering radiation oncology. The 2014–15 target was identified as 69, and the actual result was reported as 75.58 Health’s achievement against this target over the past five years is shown in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1: Number of sites delivering radiation oncology: 2010–15

|

|

2010–11a |

2011–12a |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

|

Target |

61 |

65 |

66 |

68 |

69 |

|

Actual |

61 |

63b |

66 |

69 |

75 |

Note a: Prior to 2012–13, Health reported on ‘the number of Radiation Oncology Health Program grants provided’ rather than the ‘number of sites delivering radiation oncology’. Health advised that the majority of radiation oncology facilities receive Scheme funding to purchase equipment.

Note b: In Health’s 2011–12 Annual Report, the number of sites was recorded as 64, however, in subsequent Annual Reports this figure was reported as 63. The department did not address this discrepancy in figures reported in its Annual Reports.

Source: Health Annual Reports, 2010–11 to 2014–15.

3.3 Health also reports on one qualitative performance indicator, which is expert stakeholder engagement in pathology, diagnostic imaging and radiation oncology. The 2014–15 Annual Report noted that ‘[t]he Department has worked with stakeholders and service providers to support the delivery of high-quality radiation oncology services that have resulted in better health outcomes for patients’.59

3.4 Health advised the ANAO that its quantitative performance target — access to radiation oncology services — is linked to Health’s long term planning activities because Scheme equipment approvals are granted based on analysis of ‘areas of need’, incorporating cancer incidence and Australian Institute of Health and Welfare data. The quantitative performance indicator is relevant and reliable, but it is not complete as an indicator of patient access.60 It focusses on one dimension of access, the total number of sites delivering radiation oncology, and does not address other dimensions, such as the location of services. Consequently, the indicator does not help inform Parliament and stakeholders of the link between funding provided under the Scheme, alignment with identified areas of need, and improvements in patient access. Similarly, the qualitative performance indicator relating to stakeholder engagement does not provide insight into how stakeholder consultation is likely to translate into the achievement of the Scheme’s objectives.

3.5 During the course of the audit, Health also published information on the percentage of the Australian population located in each state, and the number and percentage of linear accelerators and facilities in each state.61 This information provides a basis for improved reporting on the Scheme’s contribution to improved equity of access for patients.62

Internal performance reporting

3.6 Internally, Health reviews information relating to workforce capacity projects, dosimetry accuracy, cancer survival rates, and improvements to patient access.

Have the Scheme’s outcomes been evaluated against its policy objectives?

The Scheme has been operating continuously for nearly three decades. In that time, the Scheme has been the subject of a number of internal and external reviews. Some of these reviews resulted in changes to specific elements of the Scheme. However, no recent review or evaluation has systematically assessed the Scheme’s outcomes against its four policy objectives. The ANAO reviewed key evaluations, reviews and other information available to Health to assess the Scheme’s performance. Overall, it is difficult to assess the specific contribution made by the Scheme as a complex range of policy settings and related programs have also influenced the sector since 1988.

In summary, there have been improvements in the number of facilities and machines used to treat cancer; and the number and proportion of facilities located in regional areas. This period has also seen an improvement in patient bulk-billing rates for radiotherapy and therapeutic nuclear medicine, as well as a reduction in the average age of the equipment fleet. Together, these developments are likely to have contributed to realising the Scheme’s stated policy objectives.

However, a number of other factors are likely to have contributed to these changes, including the incentive for public and private sector organisations to locate facilities in areas that will maximise patient throughput and return on investment; other Government policies aimed at improving the affordability of health care services; and specific funding programs for radiation oncology facilities. Consequently, the extent to which the Scheme has directly contributed to these outcomes is unclear.

3.7 Since the Scheme’s inception in 1988, there have been a number of internal and external reviews of both the Scheme and the radiation oncology sector. Of these reviews, one of the most significant was the 2002 Baume Inquiry63, which made a number of recommendations relating to the Scheme’s design and administration including: consideration of areas of need, aligning the funding model for public and private facilities, promoting multidisciplinary care and workforce planning, prioritising a reduction in the average age of linear accelerators, and reviewing equipment eligibility.

3.8 No recent review or evaluation has systematically assessed the Scheme’s outcomes against its policy objectives. The ANAO examined key reviews and evaluations commissioned to date and a range of other information available to the department, to assess the Scheme’s performance against its four policy objectives.

Aligning facility locations with identified areas of need

3.9 During the operation of the Scheme, there have been a number of changes to the quantity and distribution of radiation oncology services in Australia, consistent with the Scheme’s objective to increase access to services. The changes include:

- the number of megavoltage machines64 used to deliver radiation oncology services in Australia has increased from 46 megavoltage machines in 198865 to around 200 in 2015;

- the aggregate number of treatment facilities has also increased. Prior to 1988, there were 18 public and private treatment facilities.66 By 2015, the number of radiation oncology facilities funded under the Scheme has increased to 76;

- in 2002, out of 44 radiation oncology facilities in Australia, only six (14 per cent) were in rural and regional areas.67 Since then, the number and proportion of facilities in regional areas has increased. By 2015, of the 76 facilities receiving funding, 57 were located in major cities, and the remaining 19 (or 25 per cent) were located in regional areas68; and

- data provided by Health indicates that there is now a broad alignment between the population in each state and territory and the number of linear accelerators and facilities located there. 69

3.10 A number of related policies, such as the Health and Hospitals Fund, Regional Cancer Centres, and the Better Access to Radiation Oncology program, are also likely to have contributed to the outcomes listed above. In addition, both private and public organisations have their own incentives to locate facilities in areas where they believe that patient throughput will be sufficient to sustain their operation.

Improving equity of access for cancer patients

3.11 Affordability is an important factor in facilitating patient access to radiation oncology services. Patients can face a variety of costs including: the cost of travel to treatment facilities; accommodation; loss of income while travelling to treatment; childcare costs; and direct costs of treatment, such as gap payments and upfront expenses. Health considers affordability in the context of assessing applications for funding under the Scheme. In particular, one of the six Scheme criteria relates to bulk-billing commitments presented by facilities. While the department does have the ability to make bulk-billing a condition of funding70, as discussed in paragraphs 2.30–2.32, the department does not have a clearly articulated policy framework around patient accessibility to support a consistent and outcome-focused approach to the imposition of bulk-billing conditions.

3.12 Since 1988–89, the rate of bulk billing for Radiotherapy and Therapeutic Nuclear Medicine services has steadily increased from 12 per cent to its current rate of 67.9 per cent, as shown in Figure 3.1.71

Figure 3.1: Percentage of radiation oncology services bulk-billed through Medicare 1988–89 to 2014–15

Source: Health Annual Medicare Statistics.

3.13 The rate of bulk-billing for radiation oncology services is comparable to the overall rate of bulk-billing for Medicare-eligible services and across region types. Where patients incur out-of-pocket costs, the MBS average patient contribution for radiotherapy and therapeutic nuclear medicine was around $37 in 2014–15.72 Medicare data demonstrates that more than 80 per cent of all radiotherapy services are charged at the MBS fee or less. Consequently, a large proportion of patients experience no or low out-of-pocket costs for their treatment.

3.14 The rate of bulk-billing in the private sector is substantially lower than the overall rate. Health advised the ANAO that private radiotherapy services account for around 24 per cent of all radiotherapy services, and of these private services, around 29 per cent are bulk-billed. Health also advised that in most areas where patients are charged high fees, there is a ‘no-cost high quality’ alternative available to patients such as a public hospital.

3.15 A discussion paper prepared by Health in 2012 pointed to a range of factors that are likely to have improved the rate of bulk-billing, in particular the introduction of the Extended Medicare Safety Net (EMSN) in 2004, and an increased number of public facilities providing radiation oncology services. Accordingly, the extent to which the Scheme has directly improved financial accessibility is unclear.

Replacement of equipment

3.16 The ROHPG Scheme is intended to promote timely replacement of radiation oncology equipment. This approach is considered to deliver better health outcomes, as incremental improvements in technology are expected to increase the accuracy, safety and effectiveness of treatments to better control and cure tumours and reduce side effects.73 In addition, as the machines used to deliver radiation therapy increase in age, their reliability generally reduces, and it may become more difficult to source parts for maintenance.

3.17 A survey in 1999 found that there were 94 linear accelerators and one cobalt machine in Australia. The mean age of equipment was 6.3 years; in general the machines in the public system were older (mean age of 7.0 years) than the machines in the private system (mean age 3.9 years); and there were three public facilities where the mean age of machines was approximately twice the national average (11.5, 12.1 and 14.0 years).74

3.18 Similarly, the 2002 Baume Inquiry found that a ‘substantial proportion’ of the machines in the public sector were more than 10 years old; with some machines more than 15 years old still operating. The Inquiry also noted that the incentives that were in place for private facilities to replace their equipment in a timely manner did not apply to public facilities. Subsequent changes to the Scheme brought the public sector funding arrangements into line with the private sector in this regard. Survey data from the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists suggests that between 2000 and 2010, there has been a reduction in the average age of the radiation oncology equipment fleet. In particular:

- the percentage of linear accelerators aged more than 10 years declined from 14 per cent to nine per cent;

- the percentage of linear accelerators aged between five and 10 years declined from 39 per cent to 28 per cent; and

- the percentage of linear accelerators aged five years or less increased from 40 per cent to 60 per cent.75

3.19 It is possible that the Scheme may have contributed to reducing the age of radiation oncology equipment in Australia. A reduction in the average age of machines, in turn, is likely to have contributed towards improving the quality of machines used, and therefore treatment outcomes for patients.76 Health has not analysed whether the reduction in the average age of machines has been due to accelerated replacement of machines in existing facilities, or increases in the overall number of new machines.