Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of New Income Management in the Northern Territory

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of FaHCSIA and DHS’ administration of New Income Management in the Northern Territory.

Summary

Introduction

1. Income Management is a welfare reform measure that involves quarantining a portion of a person’s welfare payments and subsequently allocating the quarantined funds towards priority needs such as food, clothing, housing and utilities. Income managed funds cannot be used to purchase excluded goods and services including alcoholic beverages, tobacco products, pornographic material and gambling services.

2. The Social Security (Administration) Act 1999 (the Act) provides the legislative basis for all forms of Income Management and sets out the objectives of the scheme, which are centred on bringing about changes in individual and community behaviours. Among other things, the Act also defines priority needs and excluded goods and services.

Evolution of Income Management

3. In 2007, the Board of Inquiry into the Protection of Aboriginal Children from Sexual Abuse released its report—Little Children are Sacred. In response to the report, the Australian Government (the Government) introduced a range of measures collectively known as the Northern Territory Emergency Response (NTER). One of these measures was the introduction of compulsory Income Management in 73 prescribed communities across the Northern Territory. At that time, Income Management was described as having two primary aims:

a) to stem the flow of cash that is expended on substance abuse and gambling; and

b) to ensure funds that are provided for the welfare of children are actually expended in this way.1

4. In 2010, following a review and redesign of some NTER measures, Income Management was extended from the 73 prescribed communities to all welfare recipients in the Northern Territory who met new eligibility criteria—known as ‘New Income Management’. Income Management is now described as ‘a key tool in supporting disengaged youth, long-term welfare payment recipients and people assessed as vulnerable, and is aimed at encouraging engagement, participation and responsibility’.2

5. Income Management is also being trialled in Cape York (since July 2008) and selected communities in Western Australia (since November 2008). Income Management is increasingly becoming an important component of the Government’s broader welfare reform agenda and, from 1 July 2012, the scheme was expanded to a further five trial sites in disadvantaged locations across Australia.3

6. There are two departments primarily involved in the delivery of Income Management. The Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) is responsible for providing policy advice and reporting on the performance of all Income Management measures. The Department of Human Services (DHS)4 is responsible for the day-to-day service delivery of Income Management, within the policy parameters established by FaHCSIA.

New Income Management

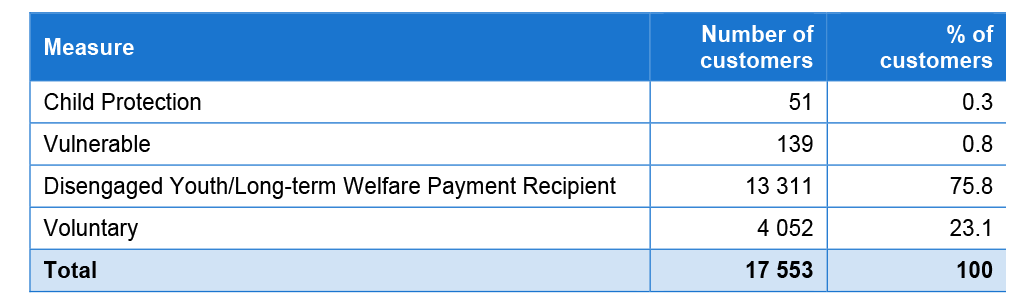

7. There were 17 553 people on New Income Management in the Northern Territory at 30 June 2012. The Government has provided $410.5 million over six years (2009–10 to 2014¬–15) for the implementation and administration of New Income Management, including complementary services (such as financial counselling), and associated programs (such as the School Nutrition program).

8. Under NTER Income Management, all people on income support payments who were living within the prescribed communities were subject to the scheme. In contrast, New Income Management introduced more targeted eligibility criteria whereby income support recipients can be subject to one of three compulsory measures, namely: Child Protection; Vulnerable; or Disengaged Youth/Long-term Welfare Payment Recipient. Further, those people not subject to compulsory Income Management can choose to participate in the scheme through a fourth, Voluntary measure. Table S1 shows the number of customers on each measure at 30 June 2012.

Table S1 Northern Territory Income Management customer numbers by measure at 30 June 2012

Source: ANAO analysis of DHS data.

9. In addition to the new eligibility criteria there are other key differences between NTER and New Income Management including:

- the opportunity for customers on the Disengaged Youth/Long-term Welfare Payment Recipient measure to be granted an exemption where they meet specific criteria; and

- the introduction of two incentive payments. The Voluntary Incentive Payment is a $250 payment to individuals for every 26 continuous weeks they remain on Voluntary Income Management. The Matched Savings Payment is a one-off payment to encourage individuals to develop a savings pattern with their discretionary funds. Eligible individuals can receive $1 for every $1 they save, up to a maximum of $500.

10. Under Income Management, between 50 to 70 per cent of a customer’s fortnightly welfare payments, and all advance or lump sum payments, are set aside in an Income Management account to be spent on the priority needs of the customer and their family. In consultation with DHS, income managed customers notionally allocate their income managed funds to priority needs. The unmanaged portion of a customer’s welfare payment is discretionary and the customer can spend these funds on any goods or services (including excluded goods and services). Income managed funds can be spent using one of three mechanisms:

- the BasicsCard—a magnetic strip, PIN protected card that enables customers to make purchases using the EFTPOS network;

- DHS making regular or one-off direct deduction payments, on behalf of the customer, into the bank account of an organisation or individual (for example, a payment to a community store); or

- DHS making regular or one-off payments, on behalf of the customer, via manual processes such as a cheque or credit card, to an organisation or individual (for example, a payment for travel to an airline company).

11. Stores and service providers that receive income managed funds in payment for goods or services are known as third party organisations. DHS has contractual agreements with some third party organisations. These agreements facilitate BasicsCard and direct deduction payments; support the objectives of Income Management (such as preventing the sale of excluded goods and services); and provide for the department to conduct compliance activities. DHS is also able to make manual payments to organisations not subject to contractual agreements.

12. The Government has commissioned a consortium of experts to conduct a strategic longitudinal evaluation of the implementation and effectiveness of New Income Management in the Northern Territory. The evaluation process includes a baseline study, which reflects the circumstances of individuals soon after the implementation of New Income Management, and a series of four annual reports, culminating in a final evaluation report due in December 2014.

Audit objective, criteria and scope

13. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of FaHCSIA and DHS’ administration of New Income Management in the Northern Territory. The departments’ performance was assessed against the following criteria:

- New Income Management was effectively planned and implemented;

- DHS has developed effective processes for servicing customers and managing third party organisations;

- DHS has established effective performance monitoring and reporting arrangements, which are used to improve service delivery; and

- FaHCSIA effectively monitors, evaluates and reports on the performance of Income Management.

14. Income Management has been an area of ongoing interest to Parliament and the community, and there has been both support and criticism of the policy across a broad spectrum of stakeholders. During the audit a range of stakeholders were interviewed. While the ANAO’s mandate does not extend to commenting on the merits of government policy, stakeholders’ views on the administration of the scheme were taken into account, where appropriate.

15. The audit scope did not include an examination of individual cases and decisions such as:

- the assessment of applications for exemptions from Income Management5; or

- decisions to apply Income Management based on Northern Territory Government referrals (under the child protection measure) or social worker assessments of vulnerable welfare recipients.

Overall conclusion

16. Since first being introduced in 2007 as part of the NTER measures, Income Management has evolved into a broader welfare policy. In this respect, from August 2010, Income Management was extended from the 73 prescribed communities under the NTER to all welfare recipients in the Northern Territory who met new eligibility criteria—known as ‘New Income Management’.

17. FaHCSIA and DHS (the departments) effectively managed the transition from NTER Income Management to New Income Management. Consistent with one of the critical success factors set by the Government, by 31 December 2010 DHS had transitioned or exited the majority of NTER customers and commenced additional customers who became eligible under the new criteria.

18. The service delivery approach required for New Income Management is resource-intensive, differs from the day-to-day processes used for the majority of services provided by DHS, and consequently is a relatively higher cost service. For a customer living in a remote area, the departments estimate that the cost of providing Income Management services is in the order of $6600 to $7900 per annum. The delivery approach adopted by DHS provides for the identification of eligible customers, the establishment of priority needs in consultation with the customer, and the payment of income managed funds to third party organisations. Consistent with the objectives of Income Management, this approach supports the primary aim of ensuring that a portion of income support and family assistance payments cannot be spent on excluded goods and services; this money is available to be spent on priority needs, including food and housing.6

19. Due to the practical operation of Income Management, however, the departments are limited in their ability to determine if the notional allocations towards priority needs translate to actual spending on these goods and services. For example, a customer who has notionally allocated $70 for food on their BasicsCard can use these funds to purchase any non-excluded goods or services at any store accepting the BasicsCard. In this situation, departments can only routinely track the amounts spent via the BasicsCard, rather than the actual goods and services purchased.

20. New Income Management has moved from the implementation phase and is now provided to over 17 500 people in the Northern Territory. Funding for New Income Management has been provided until June 2014 and this period offers an opportunity for DHS to address a number of administrative aspects, such as the compliance program and quality assurance framework, that would improve the overall operation of the scheme. It is also timely for the departments to determine whether specific features of New Income Management, such as exemptions and the incentive payments, are working as intended.

21. DHS conducts a compliance program for third party organisations subject to contractual arrangements. The 2011¬–12 results showed that compliance rates were lower than the department’s desired level of 90 per cent, with 34 per cent of BasicsCard merchants reviewed (110 from 323 reviews) being found non-compliant. DHS has implemented a revised compliance program in 2012¬–13 to address identified process weaknesses. The revised program also presents an opportunity to better understand the reasons for non-compliance and subsequently develop mitigation strategies.

22. DHS relies on a number of IT workflows and automated functionality as a basis for its quality controls. DHS has also implemented a number of additional quality controls for specific parts of the process as issues have arisen, such as quality checks for parts of the exemption decision-making process. However, there is no overarching framework that outlines the approach to quality assurance and how the different aspects collectively address the risks. Given the different service approach that has been adopted for Income Management, and the risks associated with activities such as making manual payments on behalf of customers, there would be value in DHS assessing the merits of developing an overarching quality assurance framework to support the delivery of Income Management services.

23. The capacity for some customers to gain an exemption from Income Management is a key difference between New Income Management and the previous scheme. During 2011–12, a Commonwealth Ombudsman’s review and subsequent DHS internal taskforce identified a number of significant issues with the assessment of exemption applications, particularly concerning consistency and transparency in the decision-making process.7 DHS has since introduced a number of changes to its processes and it will be important that the department continues to monitor these changes to ensure they are addressing the issues that were identified.

24. In addition to exemptions, New Income Management has seen the introduction of the Voluntary Incentive Payment and Matched Savings Payment, with mixed success. As at 30 June 2012, 13 736 Voluntary Incentive Payments had been paid to 6006 customers, for a total of $3.4 million. By its nature, the payment is designed to encourage customers to begin and stay on the Voluntary Income Management measure. However, combined with the other operational attributes of Income Management (such as facilitating bill payments), there is a risk that the payment is also a barrier to some people moving off the scheme and becoming more self-sufficient in managing their financial affairs.

25. Take-up of the Matched Savings Payment has been significantly lower than expected, with only 18 people having received the payment at 30 June 2012. This suggests that the payment is not having the intended impact on savings behaviour. There would be value in FaHCSIA and DHS reviewing the design and impact of the payments to determine how they are contributing to the objectives of Income Management, and if necessary, provide advice to the Government on options to adjust the arrangements.

26. In stating the objectives of Income Management, the Act highlights that the scheme is intended to bring about a range of changes in individual and community behaviour. As the department responsible for both policy advice and overall performance reporting, FaHCSIA has a key role in measuring the success or otherwise of Income Management in meeting its objectives. Currently, very limited information on Income Management is publicly reported, and the reporting focuses on basic metrics such as the number of people on the scheme and the amount of spending via one of three payment methods (BasicsCard). Accordingly, there is scope for FaHCSIA to improve the existing reporting arrangements by developing and reporting on a range of key performance indicators that provide insights on the effectiveness of Income Management in meeting its legislative objectives.

27. Similarly, while DHS collects an extensive amount of administrative data on Income Management, the nature of internal reporting is largely focused on specific metrics, such as customer numbers, and is not complemented by analysis of trends, key drivers, or the quality of service provision. Therefore, there is also scope for DHS to strengthen its internal monitoring and reporting arrangements by developing performance indicators that better measure the efficiency and effectiveness of Income Management service delivery.

28. The Government has commissioned a consortium of experts to conduct a strategic longitudinal evaluation of the implementation and effectiveness of New Income Management in the Northern Territory. The evaluation includes a baseline study which reflects the circumstances of individuals soon after the implementation of New Income Management, and a series of four annual reports. The findings of the evaluation, particularly the final report due in December 2014, can be expected to provide important insights on the impact of Income Management and will inform the Government’s consideration of the success of the policy approach and its future direction.

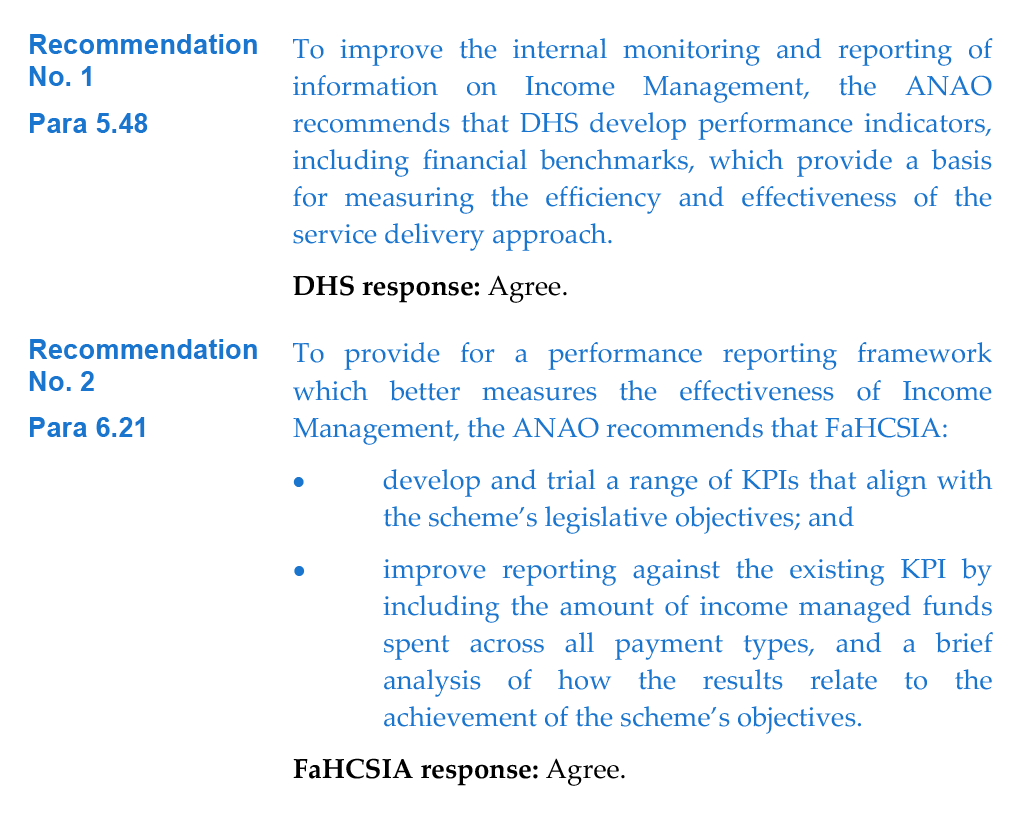

29. The ANAO has made two recommendations to improve the internal and external monitoring and reporting of Income Management. The recommendations are aimed at assisting the departments and stakeholders gain a better understanding of the service delivery performance and the success or otherwise of the scheme in meeting the stated policy objectives.

Key findings

Implementing New Income Management (Chapter 2)

30. FaHCSIA and DHS worked closely together to implement New Income Management across the Northern Territory within the Government’s six-month timeframe. Both departments developed project management plans that reflected their policy and service delivery responsibilities and contained project deliverables and key outcomes to support the transition of NTER customers and the engagement with new customers.

Delivering Income Management Services to Customers (Chapter 3)

31. DHS has developed processes, including system-based workflows, which support the identification, commencement and ongoing management of customers on Income Management.

32. Under New Income Management, customers on the Disengaged Youth/Long-term Welfare Recipient measure can apply for an exemption if they meet certain criteria, which vary depending on whether the person has dependent children. In 2011–12, the Ombudsman and a subsequent internal taskforce identified a number of issues with some exemption assessments, including consistency and transparency in the decision-making process, and the explanations provided to customers in letters advising that applications were unsuccessful. While DHS has made changes to its processes to address the issues, the department should continue to monitor and review the changes to ensure they are having the intended effect. Further, there would be benefit in DHS investigating whether there are any unintended barriers which either discourage particular customer groups from applying for an exemption, or affect the likelihood of their application being successful, and taking any necessary remedial action.

33. While on Income Management, and during final discussions with DHS prior to exiting the scheme, customers are provided with opportunities to both assist them to develop budgeting skills and put in place alternative arrangements post-Income Management. However, the nature of the practical operation of Income Management, such as the facilitation of bill payment arrangements, means that there is an inherent risk that instead of developing budgeting skills, customers may come to rely on DHS and choose to remain on Income Management.

34. Two financial incentive payments are offered under New Income Management. The Voluntary Incentive Payment provides an incentive for people to commence and remain on the Voluntary measure. However, the payment is also potentially a barrier to people becoming more

self-sufficient in managing their financial affairs and moving off Income Management. Consistent with the overall objectives of Income Management, the Matched Savings Payment is designed to encourage people to develop a savings pattern and increase their capacity to manage their money. The much lower than anticipated take-up of this payment suggests that it is not achieving the intended result. There would be value in the departments reviewing the design and impact of both incentive payments to determine how they are contributing to the objectives of Income Management, and whether there is a need to provide advice to the Government on options to adjust the arrangements.

35. Customers may exit Income Management in some circumstances. However, this is not an explicit objective of the scheme and as a result there are no specific strategies in place to achieve this outcome. While some customers are likely to remain on Income Management indefinitely due to their personal circumstances, there are others who would benefit from a defined pathway to exit the scheme. This would be consistent with one of the overall aims of Income Management—to promote and support positive behavioural change and personal responsibility—and would contribute to lowering the relatively high costs of administering the scheme. Accordingly, there would be merit in the departments developing strategies to assist customers to exit Income Management, where appropriate.

Managing Third Party Organisations (Chapter 4)

36. A third party organisation wanting to provide goods and services to income managed customers can choose from three payment mechanisms, provided they meet the relevant eligibility criteria. Two of the mechanisms, which facilitate BasicsCard and direct deduction payments, are based on contractual arrangements that support the objectives of Income Management and provide for activities such as compliance reviews. The third mechanism relates to manual payments, which can provide a further option where the BasicsCard or direct deduction options are unsuitable. However, manual payments are not supported by the same contractual arrangements as BasicsCard and direct deduction payments and therefore organisations receiving manual payments are not subject to terms and conditions such as compliance reviews.

37. DHS has developed a compliance program to monitor organisations’ adherence to their contractual obligations. The 2011–12 results were lower than the department’s desired level of 90 per cent compliance, with 66 per cent of BasicsCard merchants reviewed being found compliant. The main reasons for non-compliance by BasicsCard merchants were failing to keep receipts to demonstrate the goods and services provided, and allowing the purchase of excluded goods.

38. The 2011–12 compliance program was based on manual processes, relying on information maintained in various spreadsheets. DHS identified this approach as being a risk to the quality controls for the compliance program, and the results from the limited quality assurance process demonstrated that the approach required improvement. For the 2012–13 compliance program, DHS has implemented a system supported by automated workflows. The new approach presents DHS with the opportunity to: address previously identified process weaknesses; better identify reasons for non compliance; and develop appropriate strategies to address compliance issues.

39. The nature of manual payments means that they are time-consuming and susceptible to human error. In addition, where a contract is not in place, additional risks exist and it can be more difficult for DHS to be assured that actions such as selling excluded goods or services and providing cash refunds have not occurred. Therefore, it is preferable to minimise the number of manual payments, particularly those paid on a regular basis.

40. DHS produces a report which identifies third party organisations that regularly receive multiple manual payments. This allows the department to more easily identify those organisations that could be eligible for one of the contractual arrangements but instead choose to receive manual payments. DHS is using this information to contact organisations and encourage them to participate in Income Management through a relevant contract. DHS could further use this information to better understand the factors that may inform an organisation’s decision whether to enter into a contract and develop strategies to encourage greater take-up of the arrangements.

Monitoring and Reporting Service Delivery (Chapter 5)

41. System-based controls including workflows and automated functionality feature prominently in DHS’ IT delivery design for Income Management. While these features support consistent decision-making and provide a basis for quality control, there is no overarching quality assurance framework covering all Income Management activities. With Income Management now implemented in the Northern Territory and being progressively rolled out to other locations in Australia, it is timely for DHS to consider if the current quality management processes and controls remain appropriate. In this context, there would also be benefit in assessing the merits of developing an overarching quality assurance framework to support the delivery of Income Management services.

42. The nature of the Income Management arrangements means that situations can arise where moneys are required to be returned to the Commonwealth by either a third party organisation or a customer. Between 1 July 2011 and 6 August 2012, 2832 requests for recoveries from third party organisations were actioned. Of these, 12 per cent took 30 days or more to finalise, and on 41 occasions the value of the recovery was $500 or more. In the majority of recovery cases the customer must wait until the funds have been returned before their Income Management account is re-credited.

43. As with recoveries, overpayments can potentially lead to a debt being raised against a third party organisation or a customer. The majority of overpayments that have been identified (84 per cent) are due to DHS system or processing errors. Unlike recoveries, DHS has not established guidelines or a framework to support the identification of overpayments. This increases the risk that not all overpayments are identified, or identified in a timely manner.

44. Following amendments to social security law in 2010, DHS is developing a new process for raising debts. This presents an opportunity to ensure that there is also an appropriate framework in place to identify and manage overpayments, and clarify the circumstances when an overpayment will be raised as a debt. This is particularly important given the potential impact on customers, the age of some of the identified overpayments, the underlying reasons for the overpayments and DHS’ subsequent ability to raise debts.

45. DHS prepares a monthly project status report to track progress and results. While the reports provided management with useful information during the roll-out phase, the focus of the reporting has not been updated to reflect the post-implementation operating environment. As a consequence, the reporting does not provide an indication of important ongoing success factors, such as if the services being delivered are meeting customers’ expectations.

46. There is also scope for DHS to improve its monitoring and reporting arrangements in order to better understand the cost-effectiveness of Income Management service delivery, which involves additional costs arising from the resource-intensive delivery model required for the scheme. To this end, the monitoring and reporting arrangements could be improved by developing performance indicators that better measure the efficiency and effectiveness of Income Management service delivery.

Monitoring and Reporting Income Management Objectives (Chapter 6)

47. As the department responsible for policy advice and reporting on all Income Management measures, FaHCSIA has developed a performance reporting framework that is outlined in its Portfolio Budget Statements (PBS) and reported in the Annual Report. The reporting framework in the PBS has a narrower focus than the objectives outlined in the Act and is measured by a single key performance indicator (KPI) relating to amounts spent via the BasicsCard.

48. The KPI is limited in its scope as it only includes spending via the BasicsCard, and does not provide a comprehensive view of whether Income Management is meeting its objectives. To provide a stronger basis for measuring the impact of New Income Management, there would be value in FaHCSIA developing and trialling additional KPIs that provide information on the effectiveness of Income Management in meeting its legislative objectives. In addition, reporting against the existing KPI could be improved by including spending relating to direct deduction and manual payments and a brief analysis of how the results relate to the achievement of the scheme’s objectives.

49. New Income Management is one of a range of social policy initiatives which will have an impact on individuals and communities and is based, in part, on bringing about change in individual behaviour (including encouraging socially responsible behaviour and reducing harassment). However, measuring the effectiveness of Income Management in realising changes in the behaviour of individuals is difficult for a number of reasons, including the lack of baseline data for comparison purposes.

50. Income Management is a high-profile measure that has drawn a wide variety of stakeholder views on the merits of the policy. Creating and sustaining behavioural change is not easily measured in the short term and to that end, the Government has commissioned an external evaluation to help determine the impact of New Income Management in the Northern Territory. To date, an early implementation study and one of a series of four annual reports have been completed. While focused on Income Management in the Northern Territory, the evaluation findings, particularly the final report due in December 2014, can be expected to contain important information for measuring the overall effectiveness of Income Management as a social policy approach. Accordingly, if the evaluation is able to capture sufficiently reliable data and adequately address the key aspects of Income Management, it will inform the Government’s consideration of the policy and its future direction.

Summary of agency response

51. FaHCSIA and DHS provided the following summary responses to the proposed audit report. Each department’s full response is included at Appendix 1.

Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs

The Department agrees with Recommendation Two proposed in the report. The Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs will continue to work with the Department of Human Services to improve the Key Performance Indicators for Income Management.

Department of Human Services

The Department of Human Services (the department) welcomes this report and considers that implementation of its recommendation will enhance the administration of Income Management in the Northern Territory.

The department agrees with Recommendation No.1 outlined in the report. The department will work collaboratively with the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs on developing performance indicators to improve internal monitoring and reporting on Income Management.

Recommendations

Footnotes

[1] Explanatory Memorandum, Social Security and Other Legislation Amendment (Welfare Payment Reform) Bill 2007, p.5.

[2] Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, ‘Objectives of Income Management’, in FaHCSIA, Guide to Social Security Law [Internet], FaHCSIA, 2012, available from <http://guidesacts.fahcsia.gov.au/guides_acts/ssg/ssguide-11/ssguide-11.1/ssguide-11.1.1/ssguide-11.1.1.30.html> [accessed 25 October 2012].

[3] The sites are: Bankstown, New South Wales; Logan, Queensland; Rockhampton, Queensland; Playford, South Australia; and Greater Shepparton, Victoria.

[4] In July 2011, the Human Services Legislation Amendment Act 2011 integrated the services of Medicare Australia and Centrelink into DHS. DHS delivers Centrelink services and payments to customers. Throughout this report, DHS is used instead of Centrelink.

[5] In June 2012, the Commonwealth Ombudsman released an own motion review that examined aspects of Income Management, including exemptions. Commonwealth Ombudsman, Review of Centrelink Income Management Decisions in the Northern Territory: Financial Vulnerability Exemption and Vulnerable Welfare Payment Recipient Decisions, Commonwealth Ombudsman, Canberra, June 2012.

[6] Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, ‘Objectives of Income Management’, in FaHCSIA, Guide to Social Security Law, op. cit.

[7] The Ombudsman did not assess whether the outcome of the decision was correct or preferable, other than to the extent that the outcome may have been adversely influenced by problematic decision-making processes.