Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of the Imported Food Inspection Scheme

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective is to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Agriculture’s administration of the Imported Food Inspection Scheme.

Summary

Introduction

1. While Australia is a net exporter of food, around $15 billion in processed and unprocessed food was imported in 2013–14. These imports have increased at a rate of around five per cent per annum. As food production and processing practices can vary across the world, Australian consumers may potentially be exposed to imported food contaminated by pathogenic micro-organisms or unsafe chemicals if food safety risks are not effectively managed. The harm associated with food-borne illness can be significant, for example, micro-biological contaminations from listeria can cause serious illness or death.

2. Australia is part of a bi-national arrangement involving the Australian Government, states and territories and New Zealand to manage food safety risks. Under this arrangement, the Australian Government Department of Agriculture (Agriculture) is responsible for implementing the Imported Food Inspection Scheme (IFIS) in accordance with the Imported Food Control Act 1992 (the Act). The Scheme was established ‘to provide for the compliance of food imported into Australia with Australian food standards and the requirements of public health and safety’.1

Imported Food Inspection Scheme

3. IFIS was primarily designed to enable risk-targeted border inspections of imported food based on domestic food standards.2 Under the Act, all food imported for human consumption is categorised as either ‘risk’ or ‘surveillance’ food. Foods classified as posing a medium to high risk to human health by Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ)3 are treated as ‘risk’ category foods.4 All risk foods are to be referred to Agriculture for inspection at an initial rate of 100 per cent. As a producer builds up a history of compliance with Australian import requirements for a particular food, the rate of inspection reduces to a minimum of five per cent for that particular food from that producer.

4. Foods that are not classified as posing a medium to high risk by FSANZ are treated as ‘surveillance’ category foods under the Act. Five per cent of surveillance foods are to be referred to the department for inspection. If a surveillance food fails inspection, the rate of inspection for future consignments of that food from that producer is to be increased to 100 per cent and stays at this rate until a history of compliance is established.5

5. Under the Act, importers may also elect to enter into Food Import Compliance Agreements (FICAs) with Agriculture, which involve different regulatory arrangements. FICAs are a co-regulatory assurance arrangement that allows importers to manage their compliance with safety requirements and food standards as an alternative to IFIS inspection and testing. To qualify for a FICA, importers are required to have in place a quality assurance regime—through a food safety management system—and meet other conditions, including mandatory reporting of detections of non-compliant food. While FICA holders receive faster and more convenient clearance of their products without IFIS inspection and testing, the agreements are subject to periodic audits by Agriculture.

Administrative arrangements

6. The Australian Customs and Border Protection Service (Customs) is responsible for protecting the safety, security and commercial interests of Australians, including facilitating legitimate trade and collecting border revenue.6 Customs refers import consignments to the Department of Agriculture for assessment and inspection for biosecurity regulation7 under the Quarantine Act 1908 and food safety regulation under the Imported Food Control Act 1992. Consignments of food are only to be subject to inspections under IFIS if biosecurity requirements have been met.

7. The referral of food for IFIS inspection is based on 1500 risk profiles within the Customs Integrated Cargo System (ICS).8 These profiles, which are created and managed by Agriculture, refer food to the Scheme when the consignment information declared by importers match certain criteria such as the tariff code, importer, supplier and country of origin codes. When there is a match against the profile, the information about the imported food consignment is electronically transferred to Agriculture’s Import Management System (AIMS). Agriculture then uses this information to undertake the inspection process.

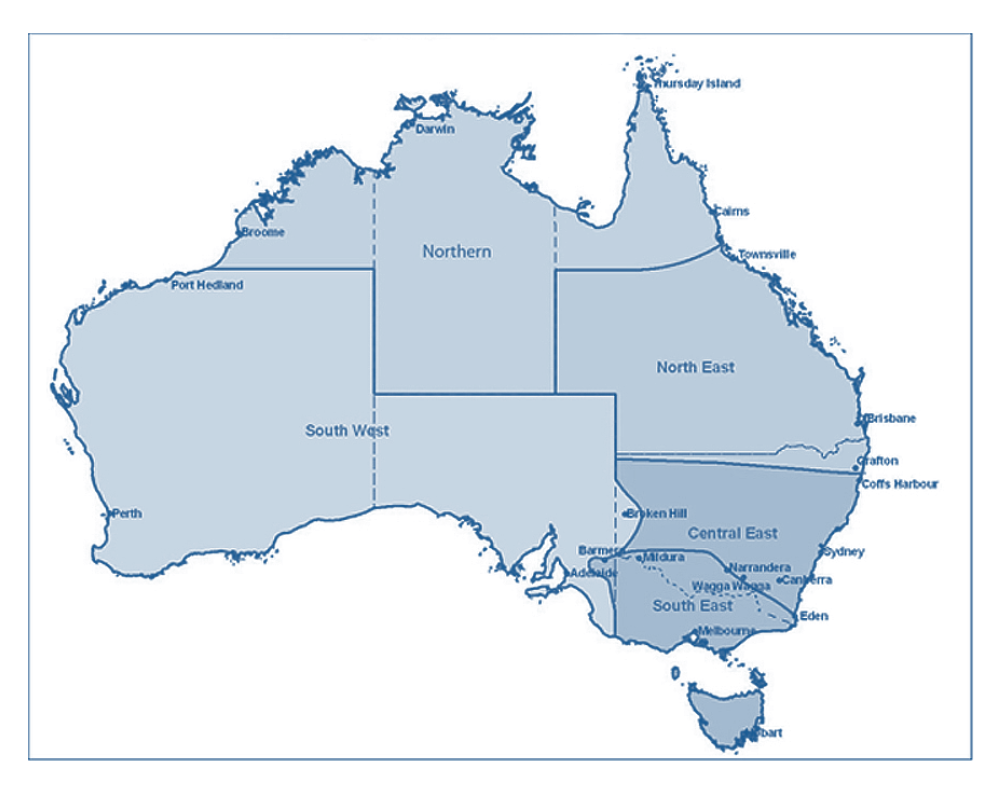

8. IFIS is administered by Agriculture’s Imported Food Section based in Canberra, which comprises 10 staff within the department’s Compliance Division. The food safety inspections conducted under the Scheme are undertaken by departmental staff at ports and warehouses across Australia (many of these staff members also undertake biosecurity compliance activities). These inspections consist of a visual examination to determine if the food appears safe and suitable, and an assessment of food labelling against the requirements of the Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code (the Code).9 In addition, private laboratories are engaged by Agriculture as ‘appointed analysts’ under the Act to conduct analytical testing for microbial, chemical and other contamination.

Recent developments

9. Recent public concerns about overseas food production and incidents of food-borne illness have triggered renewed interest in the regulation of food imported into Australia. In late 2014, two Parliamentary Committee reports on country of origin labelling were tabled.10 In February 2015, a private Senator’s Bill on country of origin labelling was also introduced into Parliament.11 The Bill mirrors a previous Bill introduced in 2013, which lapsed at the end of the 43rd Parliament.

10. In early 2015, there were also reported cases of Hepatitis A linked to the consumption of imported frozen berries and cases of scombroid poisoning linked to imported fish products. In response to these imported food incidents, Agriculture engaged with members of the food regulation network (which had also taken action relevant to their jurisdiction) and implemented a number of measures including: increasing its inspection rates for the manufacturers of identified products; requested a formal review of the risk status of frozen berries from FSANZ; and developed new testing requirements of E. coli as an indicator of process hygiene for imported berries. These incidents have further highlighted the need to appropriately assess and target food safety risks while facilitating the efficient entry of safe and compliant products into Australia (Agriculture’s responses to these incidents are discussed further in Chapters 2 and 3).

Audit objective and criteria

11. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Agriculture’s administration of the Imported Food Inspection Scheme.

12. To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level criteria:

- an appropriate governance framework to support effective regulation has been established;

- sound arrangements to collect regulatory intelligence and assess compliance risks have been established;

- a compliance program to effectively monitor compliance with regulatory requirements has been implemented; and

- effective arrangements are in place to manage non-compliance.

13. The audit focused on the delivery of regulatory activities under the Act by Agriculture. The audit scope did not include an examination of the assessment of food risks by FSANZ or the responses taken by the states and territories in relation to detections of unsafe food.

Overall conclusion

14. In 2013–14, around $15 billion in processed and unprocessed food was imported into Australia, increasing at a rate of around five per cent per annum. The importation of food from countries with varying production and processing practices has the potential to expose Australian consumers to a broad range of food-borne illnesses if food safety risks are not effectively managed. As part of the bi-national food regulatory system established by Australia and New Zealand to manage food safety, the Department of Agriculture is responsible for implementing the Imported Food Inspection Scheme (IFIS).

15. The Scheme was designed to test whether imported food meets the same safety standards as food produced domestically through targeted border inspections. The level of inspection activity is ultimately determined by the volume of food being imported and imported food risk assessments prepared by Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ). In the six months to June 2014, 44 648 tests of imported food were undertaken as part of the inspection regime.12 These tests included label and visual checks and laboratory tests for micro-biological and chemical contamination. The reported compliance rate was 98.5 per cent, with most (79 per cent) instances of non-compliance, referred to as ‘failing food’, due to breaches of labelling requirements.13

16. In the context of the legislative framework established for the regulation of imported food, Agriculture’s administration of its responsibilities under the Imported Food Inspection Scheme has been generally effective. In particular: planning for compliance monitoring is informed by food risk assessments prepared by FSANZ; regulatory activity takes into account the compliance history of producers; and actions taken are proportionate to the level of risk presented. Further, inspections are underpinned by a staff capability program, a broad range of procedural guidance material, regular management verification of activities, and food testing is conducted by independently accredited laboratories. The department has also recently commenced initiatives to make its regulatory activities more client-focused and consistent through the re-organisation of business processes and deployment of new technologies.

17. While accepting that any border inspection regime for imported food will necessarily be risk-based, there is scope to improve aspects of Agriculture’s administration of IFIS and strengthen the delivery of regulatory activities under the Scheme:

- The department is yet to establish an appropriate mechanism to gain a sufficient level of assurance that risk profiles are operating effectively and food is being referred for inspection at the prescribed rate for imported food categorised as ‘risk’ (100 per cent) and ‘surveillance’ (five per cent).

- The work practices for assessing import documentation and managing inspection activities varies across Agriculture’s regional offices. As a consequence, the implementation of important inspection related activities, such as reporting the evasion of inspections and the sale of food prior to inspection, are inconsistent.

- The management of investigations in relation to serious breaches of importer requirements has been variable. The strengthening of investigation practices, particularly in relation to documenting preliminary reviews of reported incidents and appropriately planning investigations, would better position the department to respond to suspected non-compliance.

- The department is yet to develop appropriate performance measures specific to the Scheme and regularly monitor and report against these to: identify and respond to emerging trends and changes in the regulatory environment; and demonstrate to internal and external stakeholders the extent to which the Scheme is achieving its regulatory objectives.

18. In light of recent imported food incidents, Agriculture has given preliminary consideration to legislative reforms that would better assist in the management of food incidents and also provide for systemic improvements in the regulation of imported food. The reforms under considerations would, if adopted, allow the department to: hold food pending the preparation of a risk assessment by FSANZ; conduct compliance campaigns and intelligence gathering activities beyond risk and surveillance food inspections; and apply holding orders to allow for the establishment of new testing requirements, among other things.

19. To strengthen Agriculture’s administration of IFIS, the ANAO has made three recommendations designed to: provide greater assurance over the implementation of prescribed inspection rates; improve the management of inspection related activities and investigations; and enhance performance monitoring and reporting arrangements.

Key findings by chapter

Compliance Intelligence and Risk Assessment (Chapter 2)

20. In recent years, Agriculture has worked to improve its compliance intelligence capability across its regulatory activities, with a primary focus on biosecurity regulation. The regulatory intelligence collected and retained by the department for imported food is, however, limited. Information about incidents, recalls, and breaches of state and territory food regulation are not currently retained in an integrated intelligence system. There is scope for Agriculture to better integrate its intelligence capability through the development of an IFIS compliance intelligence strategy and further strengthen its compliance information sharing arrangements with co-regulators.

21. The classification of imported food as ‘risk food’ by Agriculture is based on risk assessments prepared by FSANZ, which is in accordance with the legislative framework applying to imported food. There would, however, be benefit in the department making greater use of the compliance intelligence that it collects to build its understanding of the sources of compliance risk and to inform its requests to FSANZ for food risk assessments. These measures would help to ensure that the classification of food and the testing regime for particular categories of food are appropriate over time.

Monitoring Compliance (Chapter 3)

22. Agriculture provides general information on its website and provides direct guidance to importers to encourage voluntary compliance. To complement existing approaches, there would be benefit in the department targeting its communication activities to small-scale importers at risk of inadvertent non-compliance. Further, the limited take-up of FICAs (considerably lower than expected since their introduction in 2010) suggests that the continuation of awareness activities for high-volume importers with established food safety management systems is warranted.

23. The delivery of inspection activities under IFIS is reliant on the automated referral of information from Customs’ ICS to Agriculture’s AIMS based on matching individual consignments with the risk profiles in ICS.14 Agriculture is, however, yet to establish a process to gain an appropriate level of assurance that risk profiles are operating effectively and food is being referred for inspection at the prescribed rate for ‘risk food’ (100 per cent) and ‘surveillance food’ (five per cent).15 In the absence of such a process, the ANAO analysed a sample of Custom’s data to examine the matching of consignments to profiles, and their referral to, and receipt by, Agriculture. Of the 152 sampled profiles, all consignments referred from Customs had been received by Agriculture, including 100 per cent of risk food matches.16 The implementation of a systematic approach to monitoring the referral of food to the department under the Scheme would provide greater assurance that its level of inspections is in accordance with prescribed rates.

24. Agriculture’s pre-inspection processing of food referred for inspection and the conduct of inspections is managed through an appropriate range of procedural guidance on key activities, competency requirements for staff, and regular management verifications. The department’s arrangements for managing the work of laboratories are generally sound and include performance monitoring and audit processes. Overall, Agriculture has implemented suitable arrangements to monitor the importation of food under FICAs based on the assessment of manufacturer assurance certifications, food tests and the ability to trace a sample of selected consignments.17

Responding to Non-compliance (Chapter 4)

25. Once identified, failing food (that is, food found not to be safe or compliant with domestic standards) is to be re-labelled, destroyed, re-exported or downgraded to stock feed, under the supervision of Agriculture. Overall, Agriculture has instituted appropriate responses to failing food identified through its physical inspection and laboratory testing regime. There is, however, scope for the department to improve on the timeliness of issuing holding orders to reduce the risk that further consignments of unsafe or non-compliant food are released without inspection. Further, the varying inspection workflow monitoring practices that are in place across regions increase the risk of inconsistent regulatory decision-making. In particular, the department’s reporting of the sale of food prior to inspection, was incomplete and inconsistent. In the two years to June 2014, there were 120 instances of food sold prior to inspection in the South East Region, yet only seven of these (5.8 per cent) incidents had been formally reported in accordance with procedural requirements. By contrast, the South West Region had 22 instances of food sold prior to inspection with 19 incidents reported (86.4 per cent).

26. In responding to identified or reported serious non-compliance, Agriculture has established a requirement for a preliminary review to be undertaken to assist in determining whether an investigation is to be commenced. The department’s preliminary reviews of reported incidents were not, however, appropriately documented in 40 per cent of the cases examined by the ANAO, which ultimately limits the transparency of the review process and adversely impacts on the efficient allocation of investigation resources. Once investigations were commenced, 59 per cent were discontinued, 13 of which related to investigations where preliminary reviews had not been fully documented.18

27. The establishment of appropriate plans and routine monitoring arrangements underpin the effective delivery of investigation activities. Of the 41 investigations examined by the ANAO, only nine cases had an investigation plan developed and three were subject to regular reviews in accordance with the minimum standards established in the Australian Government Investigation Standards (AGIS).19 Re-enforcing to staff the importance of implementing procedures, coupled with strengthening the management of investigations, would better support timely completion, the preparation of briefs of evidence, and ultimately, Agriculture’s implementation of its graduated response to non-compliance.

Governance Arrangements (Chapter 5)

28. Overall, appropriate administrative arrangements are in place to support the delivery of regulatory activities under IFIS, including well-established lines of responsibility between the national office and the regional office network. While staff capability is managed through a specialised training and competency accreditation program, continued effort will be required to help ensure that regional locations are able to efficiently meet the demand for inspection services and that regulatory activities are delivered in a consistent manner.

29. The effective delivery of IFIS is heavily reliant on the IT systems that support the Scheme, in particular the entry workflow management system (AIMS) that receives referrals from Customs ICS, allocates tests and manages inspection related information. In general, core workflow functions are appropriately supported by the department’s IT systems. A key limitation of AIMS is, however, its inability to produce exception reports, such as reporting on consignments referred, but yet to be inspected. Regional offices had adopted a range of spreadsheets to address this limitation, which as noted earlier, has impacted on the consistency of the delivery regulatory activities.

30. In general, Agriculture’s monitoring and reporting of its regulatory activities relates to its biosecurity compliance activities, with monitoring and reporting in relation to IFIS primarily limited to the periodic tracking of operational activities. The establishment of an appropriate set of IFIS-specific performance measures would better position the department to: identify and respond to trends and changes in the regulatory environment; and measure and report on the extent to which it is achieving regulatory objectives.

Summary of entity response

31. Agriculture’s summary response to the proposed report is provided below, with the full response provided at Appendix 1.

The Department of Agriculture (the department) considers the report and findings provide a basis for further improvements to the risk-based management of imported food under the Imported Food Inspection Scheme (IFIS). As noted in the report, imported food is currently estimated to have an overall compliance rate of 98.5 per cent, with most (79 per cent) instances of non-compliance due to breaches of labelling requirements.

The department has committed to reforms of the IFIS in response to growing levels of trade in food and community expectations of both government and importers that were expressed during the Hepatitis A Virus incident linked to imported berries.

The department is working closely with Food Standards Australia New Zealand which is reviewing its risk assessment advice that was previously provided to the department. This will inform the department’s risk management strategies under the IFIS to mitigate the risk posed by certain imported food.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 3.22 |

To gain appropriate assurance that imported food is referred for inspection in accordance with prescribed rates, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Agriculture implement a systematic approach for monitoring the operation of risk profiles and the referral of imported food for inspection under the Imported Food Inspection Scheme. Agriculture’s response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No. 2 Paragraph 4.45 |

To improve the management of inspection-related activities and responses to non-compliance under the Imported Food Inspection Scheme, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Agriculture:

Agriculture’s response: Agreed |

|

Recommendation No. 3 Paragraph 5.56 |

To inform management and stakeholders of the effectiveness of the regulatory activities under the Imported Food Inspection Scheme, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Agriculture: develop appropriate performance measures for the Scheme; and report against these measures on the extent to which objectives are being achieved. Agriculture’s response: Agreed |

1. Introduction

This chapter outlines the framework for the regulation of food imported into Australia and the role of the Department of Agriculture in implementing the Imported Food Inspection Scheme under the Imported Food Control Act 1992.

International trade

1.1 A key driver of globalisation and economic development over the past 50 years has been the rapid growth of international trade. Australia’s integration into the world economy has grown dramatically following the adoption of trade liberalisation and other measures. As trade has increased, so too has economic growth and employment. However, the world-wide movement of goods also comes with risks to domestic industries, human and animal health, and the environment. These risks arise from the introduction of exotic pests, diseases and food that is unsafe for human consumption.20

1.2 While Australia is a net exporter of food, in 2013–14, a total of $14.9 billion in processed and unprocessed food was imported into the country, amounting to six per cent of total imports, representing a trend growth rate of five per cent per annum.21 Australia’s main food imports are processed fruit and vegetables, processed seafood, soft drink and cordials, with New Zealand the major source of imports, followed by the United States, China and Singapore.

Food safety risks

1.3 Food production and processing practices can vary across the world, particularly in relation to the use of certain drugs, such as antibiotics, and hygiene and storage standards. Food safety risks include contamination by pathogenic micro-organisms and their toxins, unsafe chemicals or chemical residues, and physical factors (Table 1.1 provides further details on risk factors).

Table 1.1: Risk factors for imported food

|

Microbiological Factors |

Chemical Factors |

Physical Factors |

|

|

|

Source: Food Standards Australia New Zealand.

1.4 The harm associated with the realisation of food risks can be significant. Microbiological contaminations from e. coli, listeria monocytogenes and salmonella can cause serious illness or death. Incorrect labelling of food containing allergens, such as nuts, milk or eggs, also has the potential to cause fatalities. The transmission of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE or ‘mad cow disease’) through beef products, while rare, can also be fatal.22

1.5 While seeking to facilitate and maximise the benefits of international trade, governments have recognised the importance of managing the negative impacts associated with the entry, establishment and spread of pests, diseases and unsafe food. Trade rules, such as the World Trade Organization’s Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures, recognises the role of governments in adopting science-based measures for the protection of human, animal, plant life and health.23 In line with these measures, the Quarantine Act 1908 and the Imported Food Control Act 1992 frame the biosecurity and human health regulation of food imports into Australia.24

Food regulation system

1.6 Australia is part of a bi-national regulatory arrangement involving the Australian Government, states and territories and New Zealand to manage food safety risks. State and territory health and food regulatory bodies, and through them, local government authorities, are responsible for ensuring that food (both imported and domestically produced), which is available for sale within their jurisdictions, is safe for human consumption and meets the Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code (the Code). The Code is developed by Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ).25

1.7 Once it has cleared consignments of imported food, the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service (Customs) may refer consignments to the Department of Agriculture (Agriculture) for assessment and inspection under biosecurity regulation. The Quarantine Act 1908 establishes the requirement that all imports into Australia must comply with biosecurity conditions for entry26, with permits and conditions, import source restrictions, and government certificates and inspections used to manage biosecurity risks.27

1.8 The inspections conducted by Agriculture under the Imported Food Control Act 1992 (the Act) focus on the safety of imported food for human consumption and compliance with the Code and are only to be applied once imported food has cleared biosecurity requirements for entry. According to the Act, imported food poses a risk to human health if it has been manufactured or transported under conditions that render it dangerous or unfit for human consumption or if it contains:

- pathogenic micro-organisms or their toxins;

- micro-organisms indicating poor handling;

- non-approved chemicals or chemical residues;

- approved chemicals, or chemical residues, at greater levels than permitted;

- non-approved additives;

- approved additives at greater levels than permitted; and

- any other contaminant or constituent that may be dangerous to human health.28

1.9 The Act provides the legislative framework for the operation of the inspection regime for imported food—the Imported Food Inspection Scheme (IFIS).

Imported Food Inspection Scheme

1.10 The Department of Agriculture (Agriculture) has had primary responsibility for the inspection of imported food for biosecurity and food safety since 1990.29 The Imported Food Control Act 1992 provides the legislative basis to enable targeted border inspections of imported food based on domestic standards. These standards are developed by FSANZ and set out in the Code. The Code outlines a series of:

- general food standards, including acceptable labelling, additives and contaminants, and food product standards for categories of food, such as meat, fruits and dairy products;

- food safety standards applying to practices, premises and equipment; and

- primary production and processing standards for categories of food.30

1.11 Inspections under IFIS are primarily focused at the border. When a consignment of food has been selected for inspection, the inspection involves a visual and label assessment and may also include sampling the food for laboratory testing for contaminants, depending on the risk profile of the particular food.31 The inspection regime under IFIS applies to imported food that has been classified, on advice from FSANZ, as ‘risk food’ and ‘surveillance food’ and food imported under Food Import Compliance Agreements.32

Food risk categories

Risk foods

1.12 Risk food is subject to ‘test and hold’ direction and is not to be released for sale until test results are known. Consignments of risk food that fail inspection and, therefore, do not meet Australian standards or are determined to be unsafe cannot be imported. These foods must be brought into compliance otherwise the food is to be re-exported or destroyed. In those cases where a producer’s or importer’s consignments fail inspection, subsequent consignments from the producer/importer are to be subject to 100 per cent testing of that product until a history of compliance is re-established. Examples of tests applied to risk food are outlined in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: Examples of tests applied to risk food

|

Food Type |

Hazard |

Tests Applied |

|

Cheese—soft, semi-soft and fresh |

Micro-organisms |

E.coli, listeria monocytogenes, salmonella |

|

Peanuts and peanut products, pistachios and pistachio products |

Aflatoxin |

Aflatoxin |

|

Beef and beef products |

Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) |

National competent authority certificate from a country permitted to trade and includes mandatory declaration |

|

Seafood—bivalve molluscs such as clams, cockles, mussels, oysters, pipi and scallops |

Biotoxins and micro-organisms |

Paralytic shellfish poisons, domoic acid, E.coli, listeria monocytogenes |

Source: Department of Agriculture.

Surveillance food

1.13 Surveillance food is all other food subject to the Scheme that has not be classified as risk food. As surveillance food is not considered to pose a medium to high risk to human health, it is subject to a ‘test and release’ direction and can be distributed for sale before test results have been received. If there are adverse test results, the relevant state or territory food regulator is to be advised, with a recall initiated where considered necessary. Any action, such as a recall or withdrawal, taken in relation to goods released by an importer is to be at the importer’s expense. Examples of food-specific tests applied to surveillance food are outlined in Table 1.3.

Table 1.3: Examples of tests applied to surveillance food

|

Food type |

Hazard |

Tests Applied |

|

Milk and cream concentrated powders, including powdered infant formula |

Micro-organisms |

Salmonella |

|

Fish |

Chemical |

Malachite green, nitrofurans (including furaltadone, nitrofurantoine) and fluoroquinolones (including ciprofloxacin and enrofloxacin) |

|

Contaminant |

Histamine |

|

|

Fruit—fresh, chilled or frozen, or dried |

Chemical and micro-organisms |

Pesticides (including acephate benalaxyl, chlorfenvinphos and DDT) and E. coli. |

Source: Department of Agriculture.

Food Import Compliance Agreements

1.14 Food Import Compliance Agreements (FICAs) are a co-regulatory assurance arrangement between food importers and Agriculture that allows importers to manage their own compliance with safety requirements and food standards as an alternative to IFIS inspection and testing. In order to qualify for a FICA, importers must demonstrate an ability to implement a quality assurance regime—through a food safety management system and meet other conditions, including mandatory reporting of non-compliant food. While FICA holders receive faster and more convenient clearance of their products without IFIS inspection and testing, the agreements are subject to periodic audits by Agriculture. As at March 2015, 14 importers had entered into a FICA covering a range of food types, including cheese, tuna, peanuts, sauces and condiments. Agriculture has undertaken over 30 audits of FICA holders since July 2012.

Selecting food for inspection

1.15 The Imported Food Control Regulations 1993 set the rate at which risk and surveillance food are to be inspected, as outlined in Table 1.4.

Table 1.4: Inspection rates for risk and surveillance food

|

|

Risk |

Surveillance |

|

Initial rate |

100 per cent of consignments (‘tight’) |

Five per cent of consignments |

|

Adjusted rate for history of compliance |

Five consecutive passes, reduces inspection rate to 25 per cent (‘normal’) A further 20 consecutive passes, reduces inspection rate to five per cent (‘reduced’) |

No reduction in inspection rate for compliance |

|

Adjusted rate following non-compliance |

Return to 100 per cent of consignments for that food |

Increased inspection rate to 100 per cent (via a ‘holding order’ instrument) until five consecutive passes are achieved, then return to the initial rate of five per cent |

Source: Imported Food Control Regulations 1993.

1.16 Customs refers imported food for inspection to Agriculture based on risk profiles linked to internationally agreed tariff codes in its Integrated Cargo System (ICS). Consignments of risk and surveillance food are targeted for inspection at rates prescribed in the Imported Food Control Regulations 1993. Agriculture may also take into consideration the compliance history of the importer or producer when selecting imported food for inspection.

1.17 For each category of testing, there is: a minimum number of sample units that must be examined for each consignment; a maximum allowable number of defective sample units; an acceptable microbiological level in a sample unit; and the level that, when exceeded in one or more samples, would result in the consignment being rejected.33

Managing and enforcing compliance

1.18 Agriculture’s Biosecurity Compliance Strategy provides guidance to stakeholders, the general community and staff on the management of compliance with both biosecurity and imported food regulation. The department’s approach to managing compliance is based on its ‘responsive regulatory model’ that rewards compliance with reduced regulation, provides advice and guidance in response in inadvertent non-compliance and targets enforcement effort towards deliberate and serious non-compliance.34

Measuring and reporting performance

1.19 Agriculture’s Imported Food Inspection Data Report, published biannually, contains summary data on inspection activity. Inspection data for the period January–June 2014 includes:

- 13 844 lines of imported food were inspected35; and

- 44 648 tests were undertaken as part of the inspection process, including label and visual checks and laboratory testing for microbiological and chemical contamination.

1.20 The reported overall compliance rate was 98.5 per cent based on the tests completed, which is a similar rate to that reported in 2012. Non-compliant food labelling accounted for most findings of non-compliance, which, if removed from the test data, would increase the overall compliance rate to 99.5 per cent.

Scheme administration

1.21 The Scheme is managed in Canberra by Agriculture’s Imported Food Section, which comprises 10 staff, within the department’s Compliance Division. At January 2015, 147 Agriculture staff were authorised to undertake food safety inspections at ports and warehouses. Food inspections by departmental staff are to consist of a visual examination to determine if the food appears safe and suitable, and an assessment of food labelling against the requirements of the Code.36 In addition, private laboratories are engaged by Agriculture as ‘appointed analysts’ under the Act to conduct analytical testing for microbial, chemical and other contamination.

1.22 The Scheme is funded through cost-recovery arrangements from importers, including fees for inspections. Fees for these services are prescribed in the Imported Food Control Regulations 1993.37

Stakeholders

1.23 Key IFIS stakeholders include Commonwealth, state and territory food authorities, importers, and laboratories engaged to conduct biological and contaminant testing. Primary stakeholders include FSANZ, which develops the Code and undertakes risk assessments of imported food, and an Imported Food Consultative Committee, with members representing Agriculture, FSANZ and industry.

Recent developments

1.24 Aspects of the regulatory framework for imported food have been subject to a number of reviews in recent years in response to food incidents and related concerns raised by consumers and industry. In October 2014, the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Agriculture and Industry tabled its report on its inquiry into country of origin labelling for food. The Committee made eight recommendations to clarify country of origin labelling for food products to better inform consumers.38 In December 2014, the Senate Rural and Regional Affairs and Transport References Committee tabled its report on the requirements for labelling of seafood and seafood products. The Committee considered whether the current seafood labelling requirements provide consumers with sufficient information and recommended that cooked or pre-prepared seafood sold by the food services sector be made subject to country of origin labelling requirements.39 In February 2015, a private Senator’s Bill on country of origin labelling was also introduced into Parliament.40 The Bill mirrors a previous Bill introduced in 2013, which lapsed at the end of the 43rd Parliament.

1.25 In early 2015, the Australian Government Department of Health also detected a number of cases of Hepatitis A linked to the consumption of frozen imported berries which were sold in major supermarkets.41 Regulatory responses included national food recalls of relevant product lines, convening the National Health Incident Room to monitor the issue, and investigations into the issue by OzFoodNet and the Communicable Diseases Network of Australia.42 Agriculture’s response included: establishing a holding order for relevant products; formally requesting a review of the risk status of frozen berries by FSANZ; engaging with foreign government authorities seeking assurance on further imports; developing new testing requirements; and engaging with co-regulators as part of the national response. The Minister for Agriculture noted that the Government was considering changes to country of origin labelling and foreshadowed a review of the testing of imported food.43

Audit objective, criteria, scope and methodology

Objective

1.26 The audit objective is to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Agriculture’s administration of the Imported Food Inspection Scheme.

Criteria

1.27 To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level criteria:

- an appropriate governance framework to support effective regulation has been established;

- sound arrangements to collect regulatory intelligence and assess compliance risks have been established;

- a compliance program to effectively monitor compliance with regulatory requirements has been implemented; and

- effective arrangements are in place to manage non-compliance.

Scope

1.28 The audit focuses on Agriculture’s administration of regulatory requirements within the legislative framework in place for imported food to mid-2014. This includes Agriculture’s development of its compliance strategy in accordance with statutory prescribed inspection rates, implementation of border inspections and laboratory testing, the investigation of serious non-compliance and management of remedial action. The audit does not examine import regulation by Customs, biosecurity regulation by Agriculture, the assessment of risk food by FSANZ, the regulation of food safety by state and territory authorities, or cost recovery arrangements.

Methodology

1.29 In undertaking the audit, the ANAO reviewed Agriculture’s policies and procedures, analysed data and intelligence systems and interviewed inspectors and managers, key Commonwealth state and territory co-regulators, and industry representatives. The ANAO also conducted detailed analysis of a sample of regulatory activities undertaken in the two financial years 2012–13 to 2013–14.44

1.30 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of $499 000.

Report structure

1.31 The structure of the report is outlined in Table 1.5.

Table 1.5: Structure of the report

|

Chapter |

Overview |

|

2. Compliance Intelligence and Risk Assessment |

Examines Agriculture’s compliance intelligence capability, its assessment of compliance risks and its approach to compliance monitoring. |

|

3. Monitoring Compliance |

Examines the implementation of key elements of Agriculture’s compliance monitoring arrangements, including encouraging voluntary compliance, inspecting food and auditing compliance agreements. |

|

4. Responding to Non-Compliance |

Examines Agriculture’s approach to addressing non-compliance with IFIS, including the conduct of investigations and implementation of enforcement action. |

|

5. Governance Arrangements |

Examines the governance arrangements in place to support Agriculture’s administration of IFIS. |

2. Compliance Intelligence and Risk Assessment

This chapter examines Agriculture’s compliance intelligence capability, its assessment of compliance risks and its approach to compliance monitoring.

Introduction

2.1 Given the large and increasing volume of imported food entering Australia each year and the limited resources available to conduct assessments against safety requirements and food standards, the effectiveness of the department’s regulation depends on a sound intelligence-based, risk-targeted compliance program. The ANAO examined Agriculture’s:

- compliance intelligence capability;

- use of intelligence to assess risk(s) of non-compliance; and

- approach to targeting its compliance monitoring arrangements.

Compliance intelligence capability

2.2 The ability of Agriculture to receive and analyse regulatory intelligence depends on the effective collection and analysis of information, reliable internal and external sources of information and the development of appropriate systems to link and manage intelligence.

Planning for compliance intelligence collection and analysis

2.3 In November 2011, Agriculture developed a draft biosecurity intelligence operating strategy, which included coverage of food safety. The strategy outlined a proposed operating model to govern the collection and assessment of intelligence relating to biosecurity and food regulation. While the draft strategy was not finalised by the department, some initiatives foreshadowed in the draft strategy, such as the establishment of a biosecurity focused Compliance Policy Analysis and Intelligence (CPAI) function, have been implemented. The CPAI was established in 2012 to support decision-making in relation to compliance activity and the planning of targeted short-term compliance campaigns.

2.4 The establishment of a biosecurity intelligence function was also raised by the Interim Inspector-General of Biosecurity45 in a 2013 review, with the new intelligence unit considered to be an area for further development. The Interim Inspector-General also recommended that the department ’improve its analytical and predictive functions by expanding its strategic operational intelligence capabilities, including the development of a complementary information management system’.46 In response to this recommendation, Agriculture noted its plan to develop a whole of department intelligence strategy and review biosecurity intelligence collection. The department also informed the ANAO that it plans to improve the capture and linking of existing data, trial an electronic monitoring system and develop new intelligence products.47 The completion of this work will position the department to integrate and make better use of the information it receives from a range of sources.

Compliance intelligence sources

2.5 Agriculture receives information on the importation of food into Australia through the direct transfer of import data from Customs ICS. The data transferred to Agriculture from the ICS includes information on importers, brokers, food and other goods imported into Australia and referred to the department for assessment and possible inspection for biosecurity and food safety purposes. The accuracy of ICS data is reliant on the import declarations provided by importers and customs brokers as well as other regulatory and quality assurance activities undertaken by Customs and Agriculture (this matter is examined further in Chapter 3). The data received from the ICS is transferred electronically into the department’s Agriculture Import Management System (AIMS), which also includes additional information on importers and producers (discussed later in this chapter).

2.6 Intelligence on the activities of importers, including incidences of non-compliance, is obtained from the department’s regionally-based operational staff (responsible for both biosecurity and food regulatory activities) and co-regulators, and, to a lesser extent, from information provided by members of the public. Agriculture’s regionally-based operational staff, including inspectors, use data from AIMS and additional information from importers to conduct inspection activities. The day-to-day interactions that operational staff have with importers provides ‘on-the-ground’ knowledge of the behaviour of importers within the regulatory system. This knowledge includes the general extent to which importers are aware of their regulatory obligations and importing practices that may have particular intelligence value, such as the importation of similar products under different names into a single warehouse. This accumulated operational knowledge is not, however, systematically collected by the department and linked with other information unless it is formally reported to the investigations unit as a suspected serious breach of regulation.

2.7 The activities of co-regulators in the food regulatory system48, in particular cases of non-compliance identified by co-regulators, can be a useful source of intelligence to inform Agriculture’s compliance activities and risk assessments under IFIS. The primary means by which the department currently obtains information from co-regulators is through membership of a number of multi-jurisdictional forums as part of the bi-national food regulatory system. The department also reviews publically available information released by co-regulators on food incidents, including national food recall notices and the published outcomes of compliance activities.49 The department is, however, yet to establish agreed arrangements with co-regulators to share regulatory intelligence. The absence of agreed arrangements has been recognised by the department, with steps taken during the audit to initiate work on the strengthening of information sharing arrangements, such as the development of notification templates. While this early work is encouraging, further sustained work will be required to develop effective information sharing arrangements that usefully inform ongoing compliance work across jurisdictions.

2.8 While Agriculture has established arrangements to facilitate the reporting of suspected non-compliance with the requirements of the biosecurity and food regulatory systems from external sources such as industry and members of the public50, there are relatively few cases of suspected non-compliance under IFIS each year. Of the 526 cases reported to the department in 2014, five were imported food related matters.

Management of compliance intelligence

2.9 As outlined earlier, AIMS is the primary system used by Agriculture to support the delivery of IFIS. It is used by the department to refer food for inspection (based on data from ICS), allocate tests to be applied to food and manage the inspection process, including the recording of test results. AIMS is also used to store detailed compliance information, primarily related to the biosecurity and food regulatory systems. An overview of AIMS coverage of compliance intelligence is provided in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: Summary of AIMS coverage of compliance intelligence

|

Information included in AIMS: |

Information not included in AIMS: |

|

|

Source: ANAO analysis of Agriculture information.

Note 1: Agriculture plans to make the declaration of producer a mandatory requirement for all imported food in 2015. This was a business priority for 2011–12, which was delayed due to the requirement for technical changes in ICS.

Note 2: Operational sanctions, in the context of IFIS, include the supervised destruction or re-labelling of food that has failed inspection, and increased inspection rates for future consignments until a history of compliance is re-established.

2.10 While acknowledging that AIMS was designed as a processing system for the management of consignments through the quarantine and imported food regulatory systems, the system has been used by the department to record intelligence information. Agriculture also uses the Jade Investigator incident and investigation management system to record compliance information relating to the assessment of reports of suspected serious non-compliance with regulation, manage investigations and to prepare briefs of evidence for consideration by the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions (Agriculture’s management of incidents and investigations is examined in Chapter 4).51 The AIMS and Jade systems are, however, operated independently of each other, with no automated functionality to share compliance intelligence between the systems.

2.11 As outlined earlier, Agriculture established its intelligence function in 2012 to support decision-making in relation to its compliance activity. In undertaking this role, the intelligence unit produces reports based on the analysis of ICS and AIMS data, in addition to other internal data sources (such as the Quarantine Premises Register52) and external sources (such as Dunn and Bradstreet company information). The department’s use of its intelligence function to support imported food regulation has, however, been limited to the provision of reports on importers as part of the biennial review of FICA holders.

2.12 Overall, regulatory information collected and retained by Agriculture in AIMS is limited to the department’s regulatory responsibilities for imported food and quarantine. Relevant information about incidents, recalls, and other information from ICS are not currently retained in an integrated intelligence system. Further, the department does not effectively capture and retain information on breaches of state and territory food regulation, where relevant, with new mechanisms for receiving information on compliance action taken by states and territories currently being explored. There is scope for Agriculture to better integrate its intelligence capability through the implementation of an appropriate intelligence strategy. Further, there would be merit in reviewing existing systems used to capture compliance intelligence and the further development of information sharing arrangements with co-regulators to strengthen the department’s evidence base for the assessment of compliance risk.

Assessing compliance risk

2.13 Once collected and analysed, compliance intelligence relating to the food regulatory system provides an important basis on which to assess the risk of non-compliance.53 The assessment of compliance risk may be based on, for example: the type of food; health hazards; the compliance history of importers, brokers and producers; compliance margin54; food production processes, and country of origin. The primary approach of assessing compliance risk under IFIS is the categorisation of food, based on a consideration of potential safety hazards, which is to be inspected at prescribed rates. The Imported Food Control Regulations 1993 provides that the rates of inspection are to vary in accordance with categories of food classified as risk, surveillance and compliance agreement food.

2.14 Agriculture’s classification of risk food is guided by FSANZ’s assessments of food that present a medium to high risk to public health55, which is to be referred to the department at a rate of 100 per cent. Food that is not classified as risk or compliance agreement food is to be classified as surveillance food, which is to be inspected at the lower rate of five per cent. While food imported under a FICA is not subject to the IFIS inspection regime, companies operating under the arrangements are subject to periodic audits. In addition, Agriculture is to issue holding orders following the identification of unsafe or non-compliant food at inspections, which compels the inspection of future entries of the food at a rate of 100 per cent until a history of compliance is re-established. Holding orders may also be issued where there are ‘reasonable grounds’ for believing that food of a particular type would fail inspection.56

Food risk assessment and advice

2.15 As the bi-national food standards authority, FSANZ is responsible for assessing food risks taking into account new and emerging food safety issues both domestically and internationally. FSANZ’s advice to Agriculture under IFIS is issued in the form of imported food risk statements, designed to be science-based food safety assessments that outline the risks posed by a specific food item to public health. FSANZ is to develop imported food risk statements on request from Agriculture, in response to trigger events, such as imported food incidents, or a scheduled review of previously issued risk statements.

2.16 FSANZ risk statements cover a range of matters, including: the rationale for the decision to assess the food as medium to high risk, descriptions of adverse health effects; consumption patterns; risk factors; compliance history; relevant standards; and the approach taken overseas.57 In August 2014, the risk statements for six food items were reviewed and re-issued.

2.17 In addition to scheduled reviews by FSANZ, Agriculture can use its compliance intelligence and compliance risk assessments to request a food risk assessment by the Authority. Since July 2010, Agriculture has made eight requests for imported food risk statements from FSANZ, including two in February 2015. Five of those requests were triggered by external sources, such as the notification of Hepatitis A cases linked to imported frozen berries, rather than departmental risk management activities.58

2.18 Agriculture’s process for documenting and approving the actions taken to respond to the risk statements issued by FSANZ were largely informal until September 2014.59 Agriculture is now required to formally respond to risk statements in accordance with new inter-agency cooperation arrangements established in 2014. The department’s response to the six risk food assessments issued by FSANZ in 2014, discussed earlier, included the development of risk management strategies based on classifying the food as risk food and mandating laboratory testing for the hazards identified by FSANZ. Any changes to the testing regime adopted by Agriculture for risk food are to be published on the department’s website.

Surveillance food

2.19 As surveillance food generally presents a low risk to public health, Agriculture’s monitoring of surveillance food is focused on compliance with the Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code developed by FSANZ. The department’s approach is to select specific standards from the Code based on risk, to provide an indication of the overall compliance of a food rather than assessing compliance against the entire Code. Agriculture’s policy for determining surveillance food tests is designed to target food based on the most relevant areas of risk. This approach, while generally sound, needs to be supported by systematic and regular review to appropriately target risks and maintain public confidence in the system.

Reviewing surveillance foods

2.20 The tests that Agriculture applied to surveillance foods, which remained largely unchanged between 2007 and 2013, generally included label, visual and food-specific tests for agriculture and veterinary chemical residues, natural contaminants (such as histamine and cadmium), and microorganisms (such as Salmonella and E. coli).60 The department amended the requirements for laboratory tests in March 2013 following recommendations from a commissioned review undertaken by an external consultant. In reviewing surveillance category food tests for Agriculture, the consultant considered:

- the compliance history of the food in Australia and overseas, as well as the compliance margin;

- the nature of the food, or a production or manufacturing issue in exporting countries;

- whether the food is a significant component of the diet; and

- the need for, and availability of alternative monitoring strategies.

2.21 As part of its response to the review, Agriculture developed a draft procedure for a rolling review of surveillance food monitoring arrangements in February 2013. The procedure, which is yet to be formally endorsed, includes decision-making processes for the review of existing surveillance tests and the consideration of new tests, consistent with the approach proposed by the consultant. According to the draft procedure, reviews are to be undertaken by food group and conducted biennially. Agriculture informed the ANAO in April 2015 that it intends to revise the draft procedure and establish a schedule for reviews.

2.22 In September 2014, the department finalised surveillance test reviews for: fruit and vegetables; cereal and grains; and edible fats and oils. The new testing arrangements for fruit and vegetables, implemented in April 2015, replaced the previous requirement for a 49 pesticide screen test with a 108 chemical test.61 The changes to cereal and grains and edible fats and oils testing were implemented by Agriculture in November 2014. A summary of the revised testing strategy is outlined in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Changes to surveillance food testing (November 2014–April 2015)

|

Food |

Test Applied |

Test Removed |

Reason |

|

Cereal grains, flours, processed cereals |

Arsenic (total) Lead |

Pesticide screen 49 residues |

Heavy metals not previously tested under IFIS. |

|

Edible oils – plants |

Erucic acid |

Pesticide screen 49 residues |

Residues not relevant. Low consumption. Standard for erucic in Code. Only tested previously in mustard and canola oil. |

|

Highly processed, refined fats and oils (for example, margarine, glycerol) |

No analytical test |

Pesticide screen 49 residues |

Not relevant, low consumption. |

|

Ready to eat frozen berries |

E. coli |

None |

Process hygiene indicator (response to information on process contamination following outbreak of Hepatitis A linked to imported frozen berries) |

|

Preserved and canned fruit |

Lead |

None |

Response to information about levels of lead in preserved fruit. Maximum level for lead in fruit in Standard 1.4.1 |

|

Canned fruit |

Tin |

None |

Response to information about levels of tin in canned fruit. Maximum level for tin in canned food in Standard 1.4.1 |

Source: Agriculture.

2.23 The three reviews undertaken were generally consistent with the draft procedural framework for the rolling review of surveillance tests, although they were not conducted in accordance with the planned timeline.62 The surveillance testing reviews contained references to external sources, such as the National Residue Survey Proficient Tests Handbook, the broad rationale for the decisions, laboratory testing and reporting requirements, and methods of implementation. While the reviews noted that Agriculture had consulted with FSANZ, co-regulators, Imported Food Consultative Committee and laboratories, the reviews did not contain information on the basis on which the new chemicals were selected and details of the consultations with co-regulators and industry. Further, unlike FSANZ risk assessments, Agriculture’s reviews of surveillance food tests did not include detailed information on the previous compliance history of the food.

2.24 In general, comments provided to the ANAO by stakeholders indicated a general acceptance of the testing regime applied by Agriculture, particularly in relation to risk foods. There were, however, concerns expressed regarding the limitations of current pesticide tests and a general lack of understanding of the need for certain surveillance food tests.

Additional approaches to assessing compliance risk

2.25 A primary focus on food and its assessed risk by FSANZ, while prescribed by the Act, is one approach to the assessment of compliance risk under IFIS. Alternative approaches include the assessment of information on specific incidents, and importer, broker and producer compliance risks. In addition to routine reviews of risk and surveillance food testing arrangements, Agriculture has worked with other agencies and used compliance intelligence to implement additional testing in response to specific incidents as outlined in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3: Increased monitoring in response to specific incidents

|

Time Period |

Trigger |

Action |

|

September 2012 to January 2014 |

Advice from the Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency relating to the additional risk of nuclear contaminants from food imported from Japan following damage to Japan’s Fukushima nuclear facility. |

Agriculture implemented additional testing for radionuclides in prescribed food from Japan. |

|

February 2014 to November 2014 |

State government notification of a consumer fatality arising from an undeclared allergen in an imported drink.1 |

Agriculture issued a holding order targeting all importers of the drink. |

|

October 2014 |

Australian Competition and Consumer Commission action under Australian consumer law on artificial honey (based on corn sugar syrup) labelled as honey. |

Agriculture issued a holding order targeting the importation of artificial honey and established additional testing arrangements. |

|

February 2015 |

Australian Government Department of Health OZ Food NET detected cases of Hepatitis A linked to the consumption of imported frozen berries from China. |

Agriculture issued a holding order targeting the importation of frozen berries from two manufacturers and:

|

|

February 2015 |

A NSW Food Authority investigation scombroid food poisoning identified links with tuna and mackerel products from a particular manufacturer in Thailand. |

Agriculture increased the inspection rate for tuna from a Thailand factory to 100 per cent.2 Agriculture also contacted the Thailand Department of Fisheries to inform it of the incident, that border inspection was raised to 100 per cent of consignments and request that it investigate. |

Source: ANAO analysis of Agriculture information.

Note 1: The label on the drink was found to be in breach of the Code by failing to declare dairy content.

Note 2: Tuna is classified as risk food and is subject to 100 per cent referral for inspection. When inspected, samples are taken to test for histamine, which is linked to scombroid food poisoning. The factory in Thailand that produced the product linked to this food incident had an established history of compliance and was on the reduced rate of inspection prior to the incident.

2.26 Apart from responding to individual incidents referred to the department, Agriculture has not used its compliance intelligence to develop targeted campaigns or compliance information gathering activities due to legislative constraints.63 Of the 149 reports produced by the department’s intelligence unit over the period from 2012–13 to 2013–14, six related to the regulation of imported food. In all six cases, the reports were requested as part of the process of biennial review of FICA holders (this matter is discussed further in Chapter 3).

2.27 By contrast, planning for biosecurity focused compliance activities has involved greater use of compliance intelligence, enabled by more flexible provisions under the Quarantine Act 1908. Since 2010, Agriculture has implemented targeted cargo campaigns that comprise short-term compliance activities focused on known or potential biosecurity risks. The campaigns are informed by compliance intelligence and overseen by a National Profiling and Targeting Committee.64 While some targeted campaigns have included imported food, the primary focus has been on biosecurity regulation.65 There would be merit in Agriculture exploring options for the greater use of intelligence capabilities to inform the development of short-term targeted compliance plans.

Compliance monitoring arrangements

2.28 The delivery of compliance monitoring activities informed by an assessment of compliance risk can direct limited regulatory resources towards those areas of highest risk. Agriculture’s approach to compliance monitoring includes a high level strategy to align regulatory action with risk, program-specific operating arrangements and regionally-based implementation of compliance activity.

Compliance strategy

2.29 Agriculture’s Biosecurity Compliance Strategy outlines the department’s approach to the management of compliance with biosecurity and imported food regulation. The Strategy is based on the premise that most stakeholders will comply or attempt to comply with their regulatory obligations and outlines a regulatory model of graduated responses to non-compliance proportionate to the level of risk presented, as illustrated in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Responsive regulatory model

Source: Agriculture (reproduced by the ANAO).

2.30 Agriculture’s compliance response continuum (outlined in Figure 2.2 on the following page) indicates that guidance and support is to be offered to encourage voluntary compliance and feedback is to be used in response to inadvertent non-compliance. Corrective sanctions are to be implemented in response to opportunistic non-compliance and the full force of the law is to be applied to criminal behaviour and fraud.

Figure 2.2: Agriculture’s compliance response continuum

Source: Agriculture (reproduced by the ANAO).

2.31 Agriculture’s compliance response continuum reflects a graduated response to non-compliance with enforcement action weighted towards the most serious and deliberate breaches of regulation. This general model for addressing non-compliance is to apply across the department’s regulatory responsibilities.

2.32 The department has established a range of IFIS-specific operating arrangements, policies and procedures to support the implementation of compliance activities undertaken through its regional offices. These arrangements include:

- the requirement that all inspections (including risk, surveillance and holding order food) include label and visual checks of the food products;

- competency accreditation and verification systems for inspectors and entry processors;

- procedures for the engagement of laboratories to undertake biological and chemical contaminant testing on behalf of the department; and

- separate regime to audit the performance of importers under FICAs.

2.33 Agriculture’s implementation of these arrangements is based on its practice statement system, which includes procedural guidance, work instructions, business rules and operating procedures. The delivery of nationally consistent compliance activities requires the development and regular review of procedural guidance and processes to ensure that regionally-based operational staff are acting in accordance with established requirements.66

2.34 Agriculture’s regional offices are tasked with delivering on the department’s compliance strategy and program-specific operating arrangements. As areas within each region have different operational conditions (goods imported and exported, the frequency, volume, and transportation methods), each region is largely responsible for determining its staffing requirements to address inspection workloads within a staffing limit established by the national office. The department is, however, seeking to achieve greater consistency in practices across regions and modernise its service delivery through the development of a National Service Delivery Model (which is examined further in Chapter 5).

Conclusion

2.35 While Agriculture’s compliance intelligence capability has improved in recent years, for example with the introduction of an intelligence unit in 2012, its management of intelligence related to imported food is hindered by a lack of integration between its primary inspection system, AIMS, and other relevant information on incidents, recalls, and breaches of co-regulator legislation. Further work on linking information based on an intelligence strategy, and arrangements to share intelligence with state and territory authorities, would better position the department to support compliance planning and decision-making with a sound evidence-base.

2.36 Agriculture’s classification of risk food is appropriately based on FSANZ risk assessments, in accordance with the legislative framework for the regulation of imported food. However, the department has made limited use of its compliance intelligence and assessments of compliance risk to inform its requests of FSANZ for food risk assessments and more often relies on external triggers. There is scope for the department to make greater use of its compliance intelligence to help ensure that food is appropriately classified as risk or surveillance, and that the tests that are applied over time are appropriate.

2.37 Agriculture’s arrangements for determining surveillance food tests have evolved since 2013 and are maturing. To help ensure that surveillance food tests are appropriately aligned to changing risks over time, there would be benefit in Agriculture finalising its procedural framework for the rolling review of surveillance food tests. There is also scope for the department to explore options to use its regulatory intelligence to inform imported food compliance activities. Targeted short-term campaigns specific to imported food compliance risks, would be a useful addition to Agriculture’s graduated actions in response to non-compliance directed towards opportunistic and deliberate breaches of regulation.

3. Monitoring Compliance

This chapter examines the implementation of key elements of Agriculture’s compliance monitoring arrangements, including encouraging voluntary compliance, inspecting food and auditing compliance agreements.

Introduction

3.1 The importation of safe and compliant food depends on importers appropriately managing the risks associated with their goods and Agriculture effectively monitoring compliance with regulatory requirements. The ANAO examined Agriculture’s implementation of primary regulatory activities under its graduated approach to monitoring compliance:

- encouraging voluntary compliance by communicating regulatory expectations;

- sampling, inspecting and applying laboratory test results to risk and surveillance food; and

- auditing Food Import Compliance Agreements (FICAs).

Encouraging voluntary compliance

3.2 Agriculture encourages voluntary compliance primarily through the provision of general guidance and advice, direct engagement with importers, and the promotion of FICAs. These activities are linked with the department’s Compliance Division Stakeholder Engagement Strategy, which is discussed further in Chapter 5.

General guidance and advice

3.3 Agriculture maintains a dedicated webpage for IFIS, which provides general information on the scheme.67 The webpage includes information on tests applied to food, FICAs, fees, tailored information for consumers, importers and laboratories, and minimum documentary requirements. The information available from the website is supported by information made available to subscribers through an imported food electronic distribution list, which is used to convey news such as changes to testing requirements for particular food products.

3.4 Stakeholders are also able to contact Agriculture directly via telephone, the internet or in person to obtain information on the regulation of imported food. In 2014, the department established a new system for monitoring general enquiries, with initial data reports on general enquiries suggesting that imported food is not a major stream of interest from stakeholders contacting the department. This is consistent with the department’s monitoring of client feedback. In the period from July 2012 to April 2015, Agriculture received 887 complaints of which nine related to imported food. In the same period, 387 compliments were received of which one related to imported food.

Direct engagement with importers

3.5 Direct engagement with importers may be initiated by Agriculture as part of its processing of entry documentation prior to an inspection, or by importers providing documentation or scheduling an inspection. Often the initial contact is made between Agriculture and brokers, who subsequently provide information and documents to their client importer to facilitate an inspection. As brokers are required to be licenced under the Customs Act 1901 and tend to work with more than one importer, they are generally more familiar with the biosecurity and imported food regulatory systems.

3.6 As there are minimal industry barriers, a large number of businesses import a small number of food consignments each year.68 These small scale importers, in particular, have fewer opportunities to interact with Agriculture and build an understanding of the regulatory system. In 2013–14, 586 brokers facilitated 510 828 quarantine and food consignments for 91 277 importers. Of these, 74 257 (81 per cent) had only one or two consignments for the financial year referred by Customs to Agriculture for assessment and inspection. Of the 3599 importers of food over the same period, 2180 (or 61 per cent) had only one or two entries referred under IFIS. In contrast, the top 10 food importers had an average of over 500 referrals.

3.7 Certain small-scale importers, such as those catering for niche cultural markets, are at risk of inadvertent non-compliance if they are not adequately informed of regulatory requirements.69 Agriculture is yet to develop information, such as pamphlets in English and in other languages, to communicate imported food regulatory requirements to importers. By contrast, information on biosecurity, animal and plant health and use of farm chemicals is available on the department’s website in 23 languages and pamphlets are produced for biosecurity regulation.70 The absence of targeted information for new importers highlights the important educative role of inspectors in encouraging voluntary compliance, in addition to their primary role of monitoring compliance.

Promotion of compliance agreements

3.8 Importers may apply to Agriculture to enter into a FICA to manage their compliance with food standards as an alternative to routine inspections under IFIS. The ‘trusted’ arrangement offers industry a faster, more convenient and cost effective clearance of food. In order to qualify for a FICA, importers must meet certain conditions, assessed by Agriculture, including having a food safety management system in place that is periodically audited by the department.71

3.9 As at February 2015, 14 importers have entered into FICAs since the agreements were introduced in 2010—considerably lower than Agriculture’s initial expectation of 30–50. The department’s initial activity to promote FICAs was undertaken through the Imported Food Consultative Committee, workshops for importers and the recruitment of FICA trial participants. To encourage further take up of FICAs, Agriculture reviewed import data to identify importers most likely to be interested in the arrangement. In the period from 2012 to 2014, the department directly approached 66 importers, four of which undertook a FICA gap audit for a detailed assessment of suitability, while a further nine expressed interest in the arrangement. Agriculture also published a pamphlet in July 2013 to further promote the availability of FICAs.