Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of the Freedom of Information Act 1982

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness and efficiency of entities’ implementation of the Freedom of Information Act 1982.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Freedom of Information Act 1982 (FOI Act) and the Australian Information Commissioner Act 2010 (AIC Act) together constitute the legislative framework to provide the public with a right of access to government documents. Ministers and government entities may claim certain specific grounds (exemptions) as a basis to refuse access to documents. Those decisions are subject to appeal. Since the FOI Act’s inception, there have been more than one million applications made for access to documents. Individual entities are responsible for receiving and deciding on freedom of information (FOI) applications. The Australian Information Commissioner, supported by his office (OAIC) has responsibility for oversight of the operation of the FOI Act.

Audit objective and criteria

2. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness and efficiency of entities’ implementation of the Freedom of Information Act 1982.

3. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level criteria:

- the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner effectively and efficiently provides guidance and assistance to entities and monitors compliance with the FOI Act;

- selected entities effectively and efficiently process FOI document access applications; and

- selected entities release relevant information under the Information Publication Scheme.

Conclusion

4. The administration of FOI applications in the three selected entities examined was generally effective. While the proportion of applications where access is refused has remained relatively stable at around 10 per cent, the number of exemptions from release being claimed by all entities across the Commonwealth has increased by 68.4 per cent over the last five years1, with the use of two particular exemptions having increased by more than 300 per cent and almost 250 per cent respectively.

5. OAIC, the FOI regulator, does not have an articulated statement of its regulatory approach and has undertaken limited regulatory activity since 2012.

6. OAIC publishes a wide range of useful guidance for entities and FOI applicants.

7. In 2015–16, OAIC reported that it had met its performance target for merit review of entity decisions for the first time. The ANAO noted that the time required to conduct a merit review varies substantially, with the elapsed time for decisions reported by OAIC in 2015–16 ranging from 81 to 1228 days (average of 372 days).

8. There is very limited quality assurance or verification of the reliability of FOI data reported to OAIC by entities.

9. Based on the targeted testing of FOI applications made to AGD, DSS and DVA, those agencies generally appear to be providing appropriate assistance to applicants. The selected entities’ ability to search for documents could be improved if they had the capability to electronically search the content of all electronic documents.

10. The number of exemptions claimed by entities has increased by 68.4 per cent over the last five years. The use of two exemptions in particular has increased substantially.

11. Across all entities:

- 88 per cent of applications were processed within the required 30 day period;

- the proportion of applications refused has remained fairly constant at about 10 per cent over the last five years;

- the number of exemptions being claimed is increasing, especially in relation to two of the ‘top ten’ exemptions; and

- the number of applications for internal review is trending upwards.

12. None of the three selected entities fully complied with the FOI Act requirement to publish specific required information as part of the Information Publication Scheme (IPS).

13. None of the three selected entities, nor OAIC, met the FOI Act requirement to review the operation of the IPS in their entity by May 1 2016.

14. The three selected entities updated their disclosure logs as required, noting that four of 15 required updates were late.

Supporting findings

OAIC’s role in freedom of information

15. The OAIC website (www.oaic.gov.au) contains a large amount of guidance and information material for applicants and entities and effectively meets the obligation under s 93A of the FOI Act to ‘issue guidelines for the purposes of the Act’.

16. OAIC receives about half of all applications for review of entity decisions, with the remainder subject to entity internal review. In 2015–16, OAIC exercised a discretion not to review 31.9 per cent of the applications that were finalised that year.

17. The proportion of reviewed entity decisions set aside or varied by OAIC has increased from about 30 per cent in 2011–12 to about 50 per cent in 2015–16.

18. In 2015–16, OAIC reported that it exceeded its target for the proportion of applications for merit review finalised within 12 months. Despite this, the ANAO noted that the time required to conduct a merit review varies substantially, with the elapsed time for decisions reported by OAIC in 2015–16 ranging from 81 to 1228 days (average of 372 days).

19. Around 300 entities report a range of FOI statistics quarterly and annually to OAIC. Although OAIC advised that it risk manages the collection of statistics, it undertakes very limited quality assurance of their accuracy. OAIC’s annual reports contain useful analysis and commentary on FOI statistics.

20. Since 2012, OAIC has undertaken limited FOI regulatory activity. OAIC also does not have a statement of its regulatory approach in relation to FOI.

Entity processing of freedom of information applications

21. The targeted testing of FOI applications to AGD, DSS and DVA examined by the ANAO suggested that the selected entities generally met the requirement to assist applicants to lodge applications.

22. The ANAO’s targeted testing of FOI applications to AGD, DSS and DVA showed that the selected entities generally conducted reasonable searches to attempt to locate documents. Entities’ ability to search for relevant documents could be improved were the entities able to electronically search the contents of all documents (rather than just by title).

23. The FOI Act requires that entities determine (make a decision about) applications within 30 days. Between 2011–12 and 2015–16, 88.4 per cent of FOI applications were reported as having been determined within 30 days.

24. Based on its targeted testing in selected entities, the ANAO concluded that those entities appropriately applied refusals and exemptions and conducted internal reviews. About 10 per cent of all FOI applications are refused (that is, that access to documents is not given). The number of exemptions (that is, grounds to deny access) claimed over the last five years has increased by 68.4 per cent, noting that an individual FOI claim can be subject to multiple categories of exemption. Over the same period the number of applications increased by 53.4 per cent. The use of the ‘certain operations’ and ‘national security’ exemptions has increased by 318 per cent and 247 per cent respectively.

25. The number of applications for internal review of FOI decisions increased by 35 per cent from 2014–15 to 2015–16. The proportion of internal review decisions where the original decision was affirmed is about half.

26. Of the selected entities, AGD has a manual which provides guidance for FOI decision-makers and administrators. There would be benefit in DSS and DVA considering whether to develop a manual or other consolidated guidance material.

Information Publication Scheme

27. None of the three selected entities met all of the statutory requirements for information they are obliged to publish as part of the Information Publication Scheme.

28. None of the three selected entities, nor OAIC, met the statutory requirement to review the operation of the Information Publication scheme by 1 May 2016.

29. Based on the limited number of FOI applications to the selected entities examined by the ANAO, AGD, DSS and DVA had updated their disclosure logs as required except that four of 15 required updates were late.

Recommendation

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 2.36

The Office of the Australian Information Commissioner should develop and publish a statement of its regulatory approach based on an assessment of risks and impacts associated with entity non-compliance with the requirements of the FOI Act.

Entity response:

Agreed. I am pleased to report that the OAIC’s 2017–18 Corporate Plan contains a commitment to develop an FOI regulatory action policy. This policy will outline our regulatory approach with respect to our full range of FOI functions. The 2017–18 Corporate Plan is available on the OAIC’s website at www.oaic.gov.au.

Summary of entity responses

30. A summary of entity responses is below, with full responses provided at Appendix 1.

Office of the Australian Information Commissioner

The OAIC welcomes external scrutiny of its operations and will seek to use the useful engagement we have had with the ANAO during the course of this audit, and the contents of the report, to assist us in our continuous endeavours to improve our operations in accordance with our statutory responsibilities to the benefit of the Australian community.

The OAIC also welcomes the acknowledgement in the report the OAIC has been through a sustained period of uncertainty between the 2014 and 2016 budgets, when responsibility for undertaking a large slice of the OAIC’s FOI functions and associated resourcing was withdrawn from the OAIC and distributed to other agencies. Now that that period is behind us the OAIC is pursuing all of its statutory FOI regulatory activity, taking into account our resourcing and balancing our priorities across all of our statutory functions.

The OAIC agrees with the ANAO’s recommendation to create an FOI regulatory action policy. The OAIC’s 2017–18 Corporate Plan contains a commitment to develop an FOI regulatory action policy. Although aspects of such a document are already contained in the FOI Guidelines the OAIC acknowledges that pulling this information together and expanding on it in a single policy document will assist agencies and the public better understand the OAIC’s approach to its FOI regulatory activity.

Attorney-General’s Department

The Attorney-General’s Department welcomes the findings of the ANAO audit on the administration of the Freedom of Information Act 1982 (the audit). The department is particularly pleased with the findings regarding the timeliness of processing requests and the static nature of the proportion of requests being refused.

The department is continually looking for ways to improve its processes and will consider options for streamlining the disclosure log process to ensure the statutory timeframe of 10 business days is routinely met.

Department of Social Services

I welcome the findings of the report, and I am pleased to note that the ANAO considers that DSS is administering the FOI Act effectively. DSS takes seriously its obligations under the FOI Act to treat Government-held information as a national resource and to provide the Australian community with access to documents in accordance with the legislative framework.

I also note the specific areas the ANAO has identified where DSS could improve its FOI administration, particularly with regard to:

- developing a manual or other consolidated guidance material for FOI decision-makers and administrators; and

- reviewing and updating its Entity Plan to maintain full compliance with the Information Publication Scheme requirements under section 8 of the FOI Act.

Department of Veterans’ Affairs

The Department of Veterans’ Affairs notes the result of the audit and thanks the Australian National Audit Office for the opportunity to respond to the issues raised.

1. Background

Freedom of information in the Australian government

1.1 There are two key Acts which govern the administration of freedom of information in Australia: the Freedom of Information Act 1982 (the FOI Act) and the Australian Information Commissioner Act 2010 (the AIC Act).

Freedom of Information Act 1982

1.2 The FOI Act came into effect in March 1982 and was significantly revised in 2010.2 The FOI Act applies to Ministers and almost all government entities.3 The Act’s objects are set out in Box 1.

|

Box 1: Objects of the Freedom of Information Act 1982 |

|

(1) The objects of this Act are to give the Australian community access to information held by the Government of the Commonwealth, by:

(2) The Parliament intends, by these objects, to promote Australia’s representative democracy by contributing towards the following:

(3) The Parliament also intends, by these objects, to increase recognition that information held by the Government is to be managed for public purposes, and is a national resource. (4) The Parliament also intends that functions and powers given by this Act are to be performed and exercised, as far as possible, to facilitate and promote public access to information, promptly and at the lowest reasonable cost. |

Source: Section 3, FOI Act.

1.3 Section 11 of the FOI Act creates a legally enforceable right of access to government documents.4 However, the Act also provides that certain documents (or parts of them) are exempt (or conditionally exempt) from release.5 The nine categories of exempt documents include:

- documents relating to national security, defence or international relations;

- Cabinet documents;

- documents affecting enforcement of law and protection of public safety; and

- documents subject to legal professional privilege.

1.4 There are also eight ‘conditional’ exemptions. Access must be given to a conditionally exempt document unless the relevant decision-maker decides that access to it would be contrary to the public interest to do so. Categories of conditionally exempt documents include documents relating to:

- Commonwealth-state relations;

- deliberative processes; and

- personal information6 about any person (who is not the applicant).

1.5 There are other grounds on which entities may refuse an application. These are discussed at paragraph 3.13.

1.6 The FOI Act also:

- creates an Information Publication Scheme (IPS) which requires entities to ‘publish a range of information about what the agency does and the way it does it’ as well as other information specified in section 8 of the FOI Act.

- allows people to apply to have amended (or annotated) information that an entity holds about them;

- provides for decisions made under the FOI Act to be reviewed by:

- the entity that made the decision;

- the Australian Information Commissioner (AIC – see paragraph 1.7); or

- the Administrative Appeals Tribunal;

- gives the AIC powers to conduct investigations and deal with complaints.

Australian Information Commissioner Act 2010

1.7 The Australian Information Commissioner Act 2010 (AIC Act) was part of the 2010 FOI reforms. The AIC Act provides for the statutory positions of the Information Commissioner, as head of the agency, Privacy Commissioner and Freedom of Information Commissioner (FOI Commissioner).7 The AIC Act provides the Commissioners with a range of powers related to undertaking FOI regulatory activity. The Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) supports the three Commissioners in the discharge of their functions.

1.8 Section 11(1) of the AIC Act gives the FOI Commissioner the freedom of information functions which are defined in s 8 of the Act and reproduced in Appendix 2.

Reviews of freedom of Information legislation

1.9 Since 2012, there have been two reviews relating to the freedom of information legislation.8 In 2013, Dr Allan Hawke AC undertook a review of the FOI Act and the AIC Act. Dr Hawke made 40 recommendations to streamline FOI procedures, reduce complexity and increase the effectiveness and efficiency of managing the FOI workload.9 The government did not formally respond to the report.

1.10 In 2015, Ms Barbara Belcher was commissioned by the Secretaries Board10 to undertake an independent review of whole-of-government internal regulation (known as the Belcher Red Tape review).11 The report made three recommendations with respect to FOI administration. The recommendations were accepted by the Secretaries Board in October 2015. The recommendations were:

- that entities ensure that their FOI practices impose the least burden and consider more active publication of information;

- that consideration be given to consolidating the Information Publication Scheme with other relevant government initiatives; and

- that in order to reduce the administrative burden on entities:

- FOI statistical reporting be reduced from quarterly to annually;

- that AGD seek the government’s agreement to prioritise implementation of the recommendations of the Hawke report; and

- that AGD consider the scope of exemptions.

Freedom of information requests: statistical overview

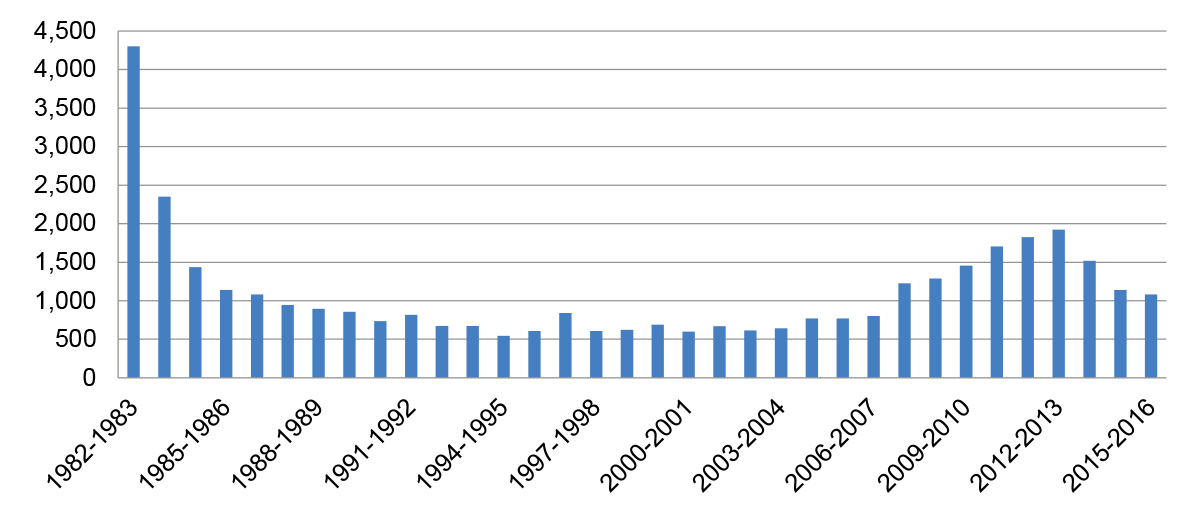

1.11 Since the FOI Act’s commencement, there have been just over one million FOI applications, with an average of about 31 000 per year. The number of requests each year are shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Numbers of FOI applications received, all entities, 1982–83 to 2015–16

Source: ANAO from <https://data.gov.au/dataset/freedom-of-information-statistics>.

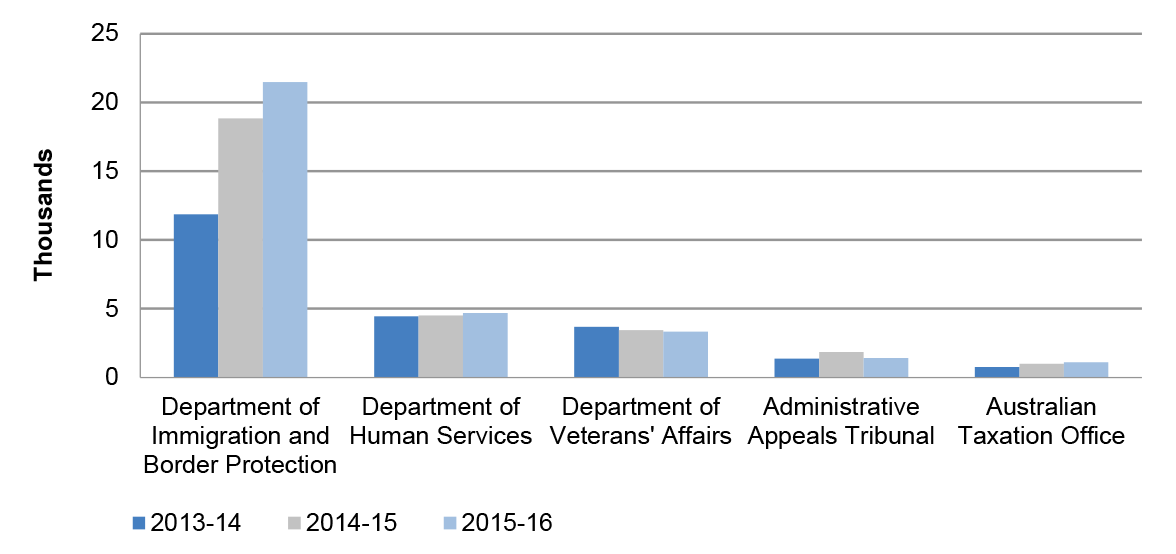

1.12 In terms of individual entities, the Department of Immigration and Border Protection receives the largest number of applications. Figure 1.2 shows the top five entities by number of applications received.

Figure 1.2: Numbers of FOI applications, Top five entities, 2013–14 to 2015–16

Note: The Social Security Appeals Tribunal, Refugee Review Tribunal and Migration Review Tribunal were amalgamated with the Administrative Appeals Tribunal on 1 July 2015.

Source: ANAO from <https://data.gov.au/dataset/freedom-of-information-statistics>.

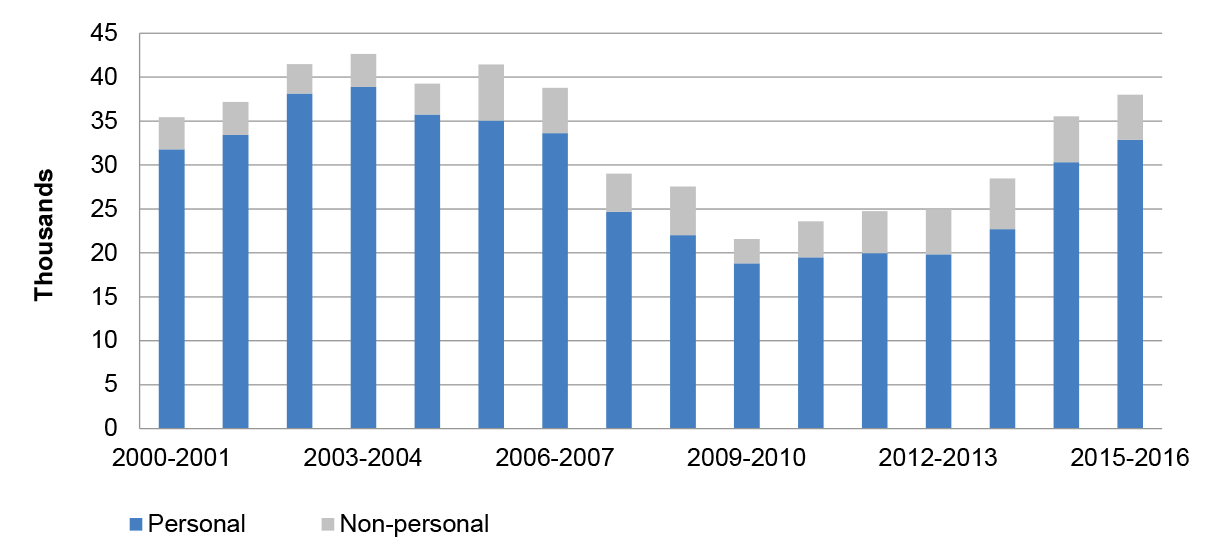

1.13 Applications are broadly categorised by entities as either ‘personal’ (that is, relating specifically to the applicant) or ‘other’.12 Prior to 2000–01, the numbers of requests for personal information and non-personal information were not separately recorded. Since then, between 80 and 90 per cent of all applications received each year have been for personal information (see Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3: Numbers of personal and non-personal FOI applications, all entities, 2000–01 to 2015–16

Source: ANAO from <https://data.gov.au/dataset/freedom-of-information-statistics>.

Cost of administering FOI

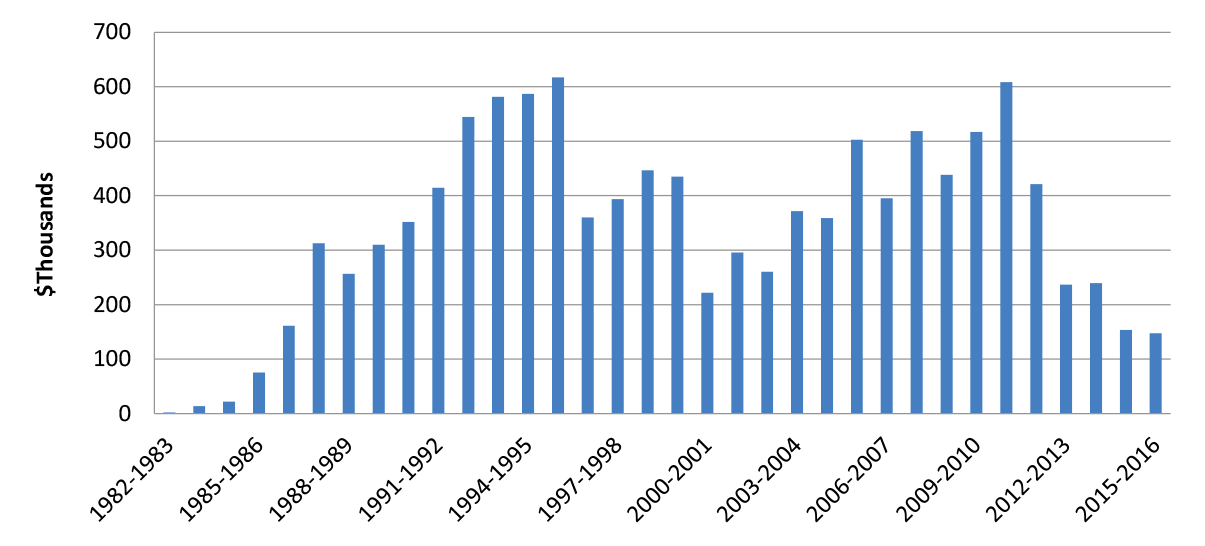

1.14 Entities have estimated their costs of administering freedom of information since its introduction in 1982. Figure 1.4 shows these estimated costs per application.

Figure 1.4: Estimated cost in 2015–16 prices of administration per application, all entities, 1982–83 to 2015–16

Note a: Annual costs have been adjusted for inflation using the Reserve Bank of Australia’s inflation calculator.

Source: ANAO from <https://data.gov.au/dataset/freedom-of-information-statistics>.

1.15 Figure 1.4 shows that the estimated cost per application increased between 2007–08 and 2012–13 but has decreased in recent years. The estimated cost per application in 2015–16 ($1,083) was close to the average long term (adjusted) annual cost of $1,113 (despite the high per application cost in the early years of implementation).

1.16 Until 2010, applicants were required to pay a $30 application fee. This fee and certain other charges were removed as part of reforms to the FOI Act but charges still apply for some items. Figure 1.5 shows fees and charges collected.

Figure 1.5: FOI fees and charges collected, all entities, 1982–83 to 2015–16

Source: ANAO from <https://data.gov.au/dataset/freedom-of-information-statistics>.

Freedom of information responsibilities

1.17 There was a change in FOI roles and responsibilities between 2014–15 and 2016–17 (see next paragraph). Current FOI roles and responsibilities are shown in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: FOI key responsibilities

|

Entity |

Key responsibilities |

|

OAIC |

Conducting merit reviews Assistance and guidance to entities and the public Issuing FOI guidelines FOI complaints and other investigations Reviewing IPS FOI statistics and reporting Monitoring and reporting on entity compliance with the FOI Act |

|

Australian government entities |

Receiving and deciding upon FOI applications Internally reviewing decisions when requested to do so Providing FOI data and statistics to OAIC |

|

Attorney-General’s department |

Policy responsibility for the FOI Act and the AIC Act |

Source: ANAO.

Intended abolition of OAIC

1.18 In the 2014–15 budget, the government announced an intention to abolish OAIC, with its functions transferred to the Australian Human Rights Commission, the Administrative Appeals Tribunal, the Commonwealth Ombudsman and the Attorney-General’s department. However, the necessary legislation to give effect to the measure13did not pass the Parliament and the Bill lapsed when Parliament was prorogued prior to the 2016 general election.

1.19 In June 2014, in recognition of the 2014–15 Budget decision and the proposed cessation of the OAIC on 31 December 2014, the OAIC prepared to cease undertaking FOI functions. This included reducing staff by 23 and closing the OAIC’s Canberra office. The OAIC continued to undertake the IC review function as it was not able to be delegated to other agencies. When the Bill to disband the OAIC was not considered by the Senate before the due date of 1 January 2015, partial funding was reallocated every six months to enable the office to continue to undertake a streamlined IC review function from the Sydney office.

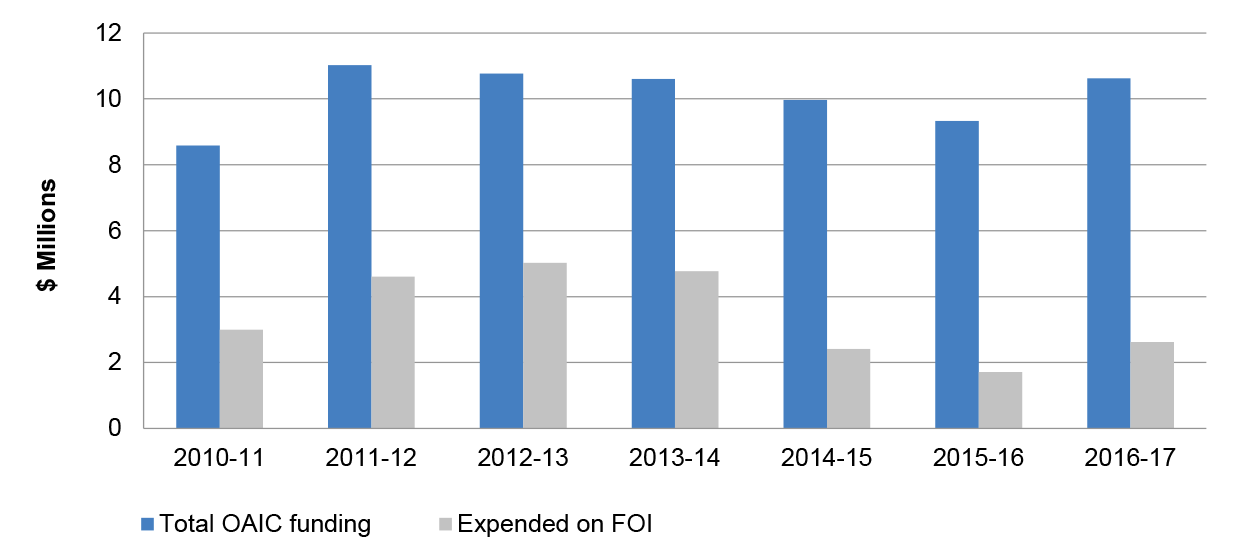

1.20 OAIC’s ongoing funding was reinstated in the 2016–17 budget and the functions that had been transferred elsewhere were returned to OAIC. Figure 1.6 shows the total budget for OAIC and the amount of funding that OAIC advised that it has estimated that it expended on its FOI functions.

Figure 1.6: Funding expended by OAIC on freedom of information functions, 2010–11 to 2016–17

Source: OAIC.

Audit approach

1.21 The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness and efficiency14 of entities’ implementation of the Freedom of Information Act 1982.

1.22 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO considered whether:

- the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner effectively and efficiently provides guidance and assistance to entities and monitors compliance with the FOI Act;

- selected entities effectively and efficiently process FOI document access applications; and

- selected entities release relevant information under the Information Publication Scheme.

1.23 The audit included targeted testing of 75 FOI applications made during the 2015–16 financial year to the Attorney-General’s department (AGD), the Department of Social Services (DSS)15, and the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA). These entities were selected16 taking account of the number and types of applications received and consideration of rejection rates, applicant withdrawal rates, processing timeliness and the use of charges. The targeted sample of applications was selected to achieve a variety of decision outcomes and decision-makers within each entity and to provide some insight into different entities’ approaches to the administration of freedom of information. Table 1.2 provides the numbers of applications selected for each department and application type.

Table 1.2: ANAO FOI targeted sample selection, by department and application type

|

Request type |

DVA |

AGD |

DSS |

Total |

|

Personal |

24 |

5 |

10 |

39 |

|

Non-personal |

7 |

18 |

11 |

36 |

|

Total |

31 |

23 |

21 |

75 |

Source: ANAO.

Audit scope

1.24 This audit has not examined charging17or complaints.18

1.25 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $580 000.

1.26 The team members for this audit were Julian Mallett, Brendan Mason, Rebecca Walker, Emily Arthur, Andrew Rodrigues and Paul Bryant.

2. The role of the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner in freedom of information

Areas examined

This chapter examines the role of the Office of Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) in the administration of freedom of information (FOI), including:

- guidance and assistance OAIC provides to entities and FOI applicants;

- OAIC’s merit review of FOI decisions;

- collecting, monitoring and analysing FOI information;

- OAIC’s role as the FOI regulator.

Conclusion

OAIC publishes a wide range of useful guidance for entities and FOI applicants.

In 2015–16, OAIC reported that it had met its performance target for merit review of entity decisions for the first time. The ANAO noted that the time required to conduct a merit review varies substantially, with the elapsed time for decisions reported by OAIC in 2015–16 ranging from 81 to 1228 days (average of 372 days).

There is very limited quality assurance or verification of the reliability of FOI data reported to OAIC by entities.

Although OAIC advised that it undertakes all its required functions, since 2012, OAIC has undertaken limited regulatory activity. It also does not have an articulated statement of its regulatory approach.

Areas for improvement

- The ANAO suggested that OAIC consider developing an approach to verifying the quality of data input.

- The ANAO recommended that OAIC develop and publish a statement of its regulatory approach.

2.1 Section 10 of the AIC Act provides that the Information Commissioner has the freedom of information functions which are defined at s 8 of the AIC Act (and reproduced at Appendix 2). Of those functions, OAIC’s website identifies ‘responsibility for regulating and providing advice on the operations of the FOI Act’ as key functions.

Does OAIC provide guidance and assistance to entities and FOI applicants?

The OAIC website (www.oaic.gov.au) contains a large amount of guidance and information material for applicants and entities and effectively meets the obligation under s 93A of the FOI Act to ‘issue guidelines for the purposes of the Act’.

Information Commissioner’s FOI Guidelines

2.2 Section 93A of the FOI Act allows the Information Commissioner to issue guidelines for the purposes of the Act. The same section requires that entities must have regard to the guidelines in exercising powers and functions under the Act. The latest version of the guidelines on the OAIC website has 15 volumes.19 The guidelines cover matters such as:

- processing applications;

- applying exemptions and conditional exemptions;

- entity internal review of decisions; and

- entity reporting obligations.

2.3 There is a link to previous versions of the Guidelines and a table summarising significant changes between each version.

Other guidance material

2.4 In addition to the FOI guidelines, OAIC provides a range of other guidance material for entities and the public. These include:

- Twenty-nine FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions) for entities;

- sixteen FAQs for individuals;

- a series of 15 ‘agency resources’ which complement other guidance material on the website;

- thirteen Fact Sheets aimed at potential applicants;

- a 75 page FOI Guide 20; and

- an FOIstats guide which provides instructions for entities on the provision of quarterly and annual statistical returns to OAIC.

2.5 There is a wide range of relevant material available on the OAIC website which provides both entities and potential FOI applicants with guidance and assistance.

Enquiries line

2.6 OAIC also provides a 1300 enquiries line. In 2015–16, OAIC responded to 2483 enquiries for assistance.

How does OAIC manage the process for merit review of entity decisions?

OAIC receives about half of all applications for review of entity decisions, with the remainder subject to entity internal review. In 2015–16, OAIC exercised a discretion not to review 31.9 per cent of the applications that were finalised that year.

The proportion of reviewed entity decisions set aside or varied by OAIC has increased from about 30 per cent in 2011–12 to about 50 per cent in 2015–16.

In 2015–16, OAIC reported that it exceeded its target for the proportion of applications for merit review finalised within 12 months. Despite this, the ANAO noted that the time required to conduct a merit review varies substantially, with the elapsed time for decisions reported by OAIC in 2015–16 ranging from 81 to 1228 days (average of 372 days).

2.7 The FOI Act provides applicants with a right of review if they disagree with a decision an entity has made with respect to an FOI application. Decisions that may be reviewed include decisions to:

- refuse access to documents or to only grant access to some documents;

- grant access to information to a third party21;

- refuse to amend or annotate personal information22; and

- impose a charge.

2.8 Where an entity has not made a decision within the prescribed time period (30 days, unless extended by agreement with the applicant), it is deemed to have decided to refuse access. This deemed decision is also reviewable.

2.9 If applicants seek a review of a decision made by an entity, they can choose between applying for review to either the entity that made the decision23 or to OAIC.24 While an OAIC merit review has the benefit of being independent of the entity that made the original decision, OAIC’s Fact Sheet 12 Freedom of Information – your review rights25 advises:

… going through the agency’s internal review process gives the agency the opportunity to reconsider its initial decision, and your needs may be met more quickly without undergoing an external review process.

2.10 Figure 2.1 shows the numbers of internal review applications compared with applications for OAIC merit review. For the period 2011–12 to 2015–16, just under half (45.2 per cent) of applications for review were made to OAIC.

Figure 2.1: Applications for internal and OAIC review, 2011–12 to 2015–16

Source: ANAO from <https://data.gov.au/dataset/freedom-of-information-statistics>and OAIC annual reports.

Outcomes of merit reviews

2.11 Only a relatively small proportion of applications to OAIC for merit review actually proceed to formal review. Applications can have one of the following outcomes:

- declined because they are out of OAIC’s jurisdiction or are invalid;

- withdrawn prior to or during review;

- resolved by agreement between the applicant, the entity and OAIC without formal review;

- subject to an exercise of discretion by OAIC not to conduct a review; or

- formally reviewed.

2.12 Figure 2.2 shows these outcomes.

Figure 2.2: Outcomes of applications for merit review, 2011–12 to 2015–16

Note a: OOJ: Out of jurisdiction.

Source: ANAO from OAIC annual reports.

Applications resolved by agreement

2.13 In its 2015–16 annual report, OAIC stated that ‘We have a strong focus on resolving applications for review by agreement between the parties where possible’. Figure 2.2 shows that while the number of applications resolved in this manner has increased since 2011–12, it accounts for a relatively small proportion (22.9 per cent in 2015–16).

Discretion not to review

2.14 Once OAIC receives an application for review, it may exercise a discretion under s 54W not to do so (or not to continue with a review). The reasons for this are that:

- the application is ‘frivolous, vexatious, misconceived, lacking in substance or not made in good faith’ (s 54W(a)(i));

- the applicant did not cooperate in progressing the review (s 54W(a)(ii));

- the applicant cannot be contacted (s 54W(a)(iii));

- the Information Commissioner decides that it would be desirable for the review to be considered by the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (s 54W(b)); or

- the applicant fails to comply with an OAIC direction (s 54W(c)).

2.15 The ANAO observed that between 2012–13 and 2013–14, the number of occasions on which OAIC exercised its discretion under s 54W doubled (from 149 to 300). Of these, 170 (56.7 per cent) were declined on the grounds that the application was frivolous, vexatious, misconceived, lacking in substance or not made in good faith. The ANAO sought comment from OAIC about whether it was aware of any reason for this increase. OAIC advised that it ‘can only speculate that, given the backlog of matters at that time, a stronger line was taken by the decision-makers on whether the review was lacking substance’.

2.16 The ANAO confirmed that there was such a backlog by comparing the number of applications OAIC had on hand26 for each year. This is shown in Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3: Applications for review on hand, 2010–11 to 2015–16

Source: OAIC annual reports.

2.17 While the ANAO notes OAIC’s explanation, it considers that the exercise of a discretion not to review an application should be based on the merits of the application rather than the discretion being used as a workload management tool.

Outcomes of formal merit review of entity decisions

2.18 The proportion of applications for OAIC merit review that proceed to a formal review and decision has varied between 9.9 per cent in 2011–12 (25 decisions) and 26.6 per cent in 2014–15 (128 decisions). Under s 55K of the FOI Act, a formal merit review has one of three potential outcomes:

- affirm the entity’s original FOI decision;

- vary the decision; or

- set aside the decision and make a fresh decision.

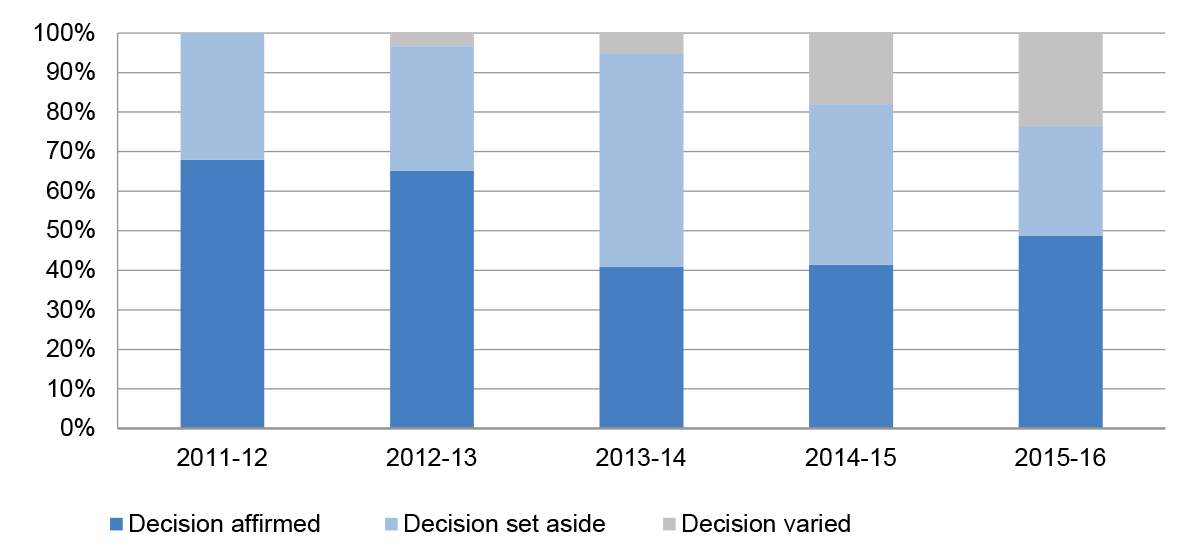

2.19 Figure 2.4 shows the proportion of decisions in each category.

Figure 2.4: Proportion of OAIC review decisions to affirm, set aside or vary entity decision, 2011–12 to 2015–16

Source: ANAO from <https://data.gov.au/dataset/freedom-of-information-statistics> and OAIC annual reports.

2.20 OAIC’s decisions on merit reviews are required to be publicly reported. OAIC complies with this by publishing the decisions on AustLII, the website of the Australasian Legal Information Institute.27 This body of cases contributes to the evolving body of FOI law and provides guidance for FOI decision-makers.

2.21 Figure 2.4 shows that the proportion of entity decisions set aside or varied by OAIC has increased from about 30 per cent in 2011–12 to about 50 per cent in 2015–16.

Timeliness of reviews

2.22 The timeliness of OAIC merit reviews has been one of its performance targets28 since its inception. Table 2.1 shows OAIC’s reported performance against its targets. OAIC reported that it was able to exceed its target for merit reviews completed for the first time in 2015–16.

Table 2.1: OAIC merit review of entity decisions: performance against PBS targets

|

Year |

PBS criterion |

Target % |

Result % |

|

2011–12 |

Reviews completed within six months |

80 |

32.8 |

|

2012–13 |

Reviews completed within six months |

80 |

25.2 |

|

2013–14 |

Reviews completed within 12 months |

80 |

71.2 |

|

2014–15 |

Reviews completed within 12 months |

80 |

71.1 |

|

2015–16 |

Reviews completed within 12 months |

80 |

87.0 |

Note: The criteria and targets for 2016–17 and 2017–18 are the same as for 2015–16 but results have not yet been reported.

Source: OAIC Portfolio Budget Statements; OAIC annual reports

2.23 The ANAO notes that the target timeframe for completion of merit reviews was increased from six months to 12 months with effect from 2013–14. The ANAO conducted an assessment of reported OAIC merit review decisions for 2015–16 and noted that the time required to undertake a merit review varies substantially. Specifically, the elapsed time (from OAIC’s receipt of the application for merit review through to the Commissioner’s decision) for decisions reported for that year ranged from 81 to 1228 days, with an average of 372 days.

2.24 OAIC advised:

The length of time taken to finalise a matter depends on a number of factors. These factors include the volume of documents under review, the exemptions applied, the security classification of the documents and the number of parties. However some matters take longer to finalise because the reviewable decision changes during the course of the IC review, adding to processing time. For example, the OAIC receives many applications for IC review of decisions ‘deemed’ to have been made refusing access to documents because the statutory timeframe has not been complied with. This gives rise to the right to seek IC review. When the OAIC receives an application for IC review of a ‘deemed’ decision, we ask the agency to make an ‘actual’ decision which then becomes the decision under review.

We experience the same issues with practical refusals, where the decision under review may change following a decision by the agency under s 55G to process the request and provide access to some documents.

Does OAIC collect, monitor and analyse FOI information?

Around 300 entities self-report a range of FOI statistics quarterly and annually to OAIC. Although OAIC advised that it risk manages the collection of statistics, it undertakes very limited quality assurance of their accuracy. OAIC’s annual reports contain useful analysis and commentary on FOI statistics.

2.25 All departments and prescribed authorities are required to supply OAIC with a wide range of statistics about their FOI activity. Returns are required quarterly and annually and are reported through a portal. OAIC provides entities with an FOIstats guide to assist them in the submission process.

2.26 The ANAO observed errors in the reported information, such as detailed breakdowns of statistics being inconsistent with totals. The ANAO asked OAIC whether it undertook any quality assurance or verification of the data input to the portal be entities. OAIC advised:

OAIC does undertake activity to risk manage the statistical collection to ensure as accurate statistics as possible are inputted by agencies but given the number of agencies and the number of data points collected and the resources available to the OAIC it is not possible to check every single data point entry each quarter and in the annual reports. The general trends observed from the statistical collection are very useful and a significant input to understanding how the FOI Act is being applied by agencies and Ministers.

2.27 FOI statistics have been reported to Parliament every year since 1998–99.29 The reports to Parliament have included detailed analysis and commentary on trends and issues.30 The reports also identify those entities which are not meeting statutory benchmarks such as processing FOI applications within the statutory time period. Such information is useful for Parliament and the ‘FOI community’.31

2.28 Whilst trend data is of use (and has been presented throughout this report), its reliability depends upon the accuracy of the raw data input by entities. There would be benefit in OAIC considering developing an approach to verifying the quality of data input.

2.29 In 2015, entities advised the Belcher Red Tape review (see paragraph 1.10) that the quarterly process of statistical reporting was ‘more administratively burdensome than necessary’ and the review report recommended that annual reporting only should be required.32

Does OAIC fulfil its regulatory role?

Since 2012, OAIC has fulfilled its regulatory role. However, it has undertaken limited investigatory action. OAIC also does not have a statement of its regulatory approach in relation to FOI.

2.30 As noted at paragraph 1.18, the government announced its intention to abolish OAIC in May 2014. As shown in Figure 1.6, the amount of funding allocated by OAIC to its FOI functions was significantly reduced. In the light of this reduction, the ANAO asked OAIC whether there were tasks or functions that it was not now performing. OAIC responded:

There are no functions that the OAIC is not now performing. The OAIC prioritises its activities within the resources available to it, to best deliver all its functions. As such, our ability to undertake intensive work, for example, around the IPS scheme and some discretionary activities such as Commissioner initiated investigations may not be as feasible as in previous years but we still plan to undertake some limited work in these areas.

2.31 Section 8 of the AIC Act imposes a number of freedom of information functions on OAIC which are listed in Appendix 2. Section 8(g) of the FOI Act gives OAIC the function of ‘monitoring, investigating and reporting on compliance by agencies with the Freedom of Information Act 1982’. In response to an ANAO request to provide examples to demonstrate its performance of this function, OAIC advised:

Reporting on compliance by agencies with the FOI Act happens in a range of ways including through our:

- Annual reports;

- publication on data.gov.au of the full set of FOI statistics provided by agencies;

- Commissioner initiated investigation reports;

- specific compliance reports eg our survey of IPS compliance; and

- submissions to inquiries eg our response to the Hawke inquiry.

2.32 The ANAO considered and assessed the examples cited by OAIC as shown in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Examples cited by OAIC of monitoring, investigation and reporting of compliance

|

OAIC example |

ANAO comment |

|

Annual reports. |

Reports have contained useful analysis and commentary on FOI trends and issues.a |

|

Publication of statistics on data.gov.au. |

Statistics are a compilation of data self-reported by entities. |

|

Commissioner initiated investigation reports. |

OAIC has initiated two investigations pursuant to s 69 of the FOI Act since its creation: one in 2012 and the other in 2014.b |

|

Specific compliance reports eg survey of IPS compliance. |

The survey was conducted in 2012. It comprised entities’ self-assessment of compliance with the IPS. |

|

Submissions to inquiries e.g.response to the Hawke inquiry. |

OAIC’s submission to the Hawke inquiry was in December 2012. |

Note a: With the exception of 2015–16 when it was anticipated that OAIC was to be abolished.

Note b: Processing of non-routine requests by the Department of Immigration and Citizenship, OAIC, September 2012 and FOI at the Department of Human Services, OAIC, December 2014.

Source: ANAO.

2.33 OAIC’s ongoing funding was reinstated in May 2016 in the 2016–17 budget and its FOI functions returned to it.

2.34 Although OAIC’s 2016–17 corporate plan and 2015–16 annual report state that it is ‘successful when we undertake FOI regulatory functions under the FOI Act in an efficient and timely manner’, OAIC’s regulatory activity since 2012 has been limited to its analysis and commentary on entities’ self-reported statistics.

2.35 As the FOI regulator, OAIC should have an explicit statement of its regulatory approach based on an assessment of risks and impacts associated with entity non-compliance with the requirements of the FOI Act.33

Recommendation no.1

2.36 The Office of the Australian Information Commissioner should develop and publish a statement of its regulatory approach based on an assessment of risks and impacts associated with entity non-compliance with the requirements of the FOI Act.

Entity response:

2.37 Agreed. I am pleased to report that the OAIC’s 2017–18 Corporate Plan contains a commitment to develop an FOI regulatory action policy. This policy will outline our regulatory approach with respect to our full range of FOI functions. The 2017–18 Corporate Plan is available on the OAIC’s website at www.oaic.gov.au.

3. Entity processing of FOI applications

Areas examined

This chapter looks at aspects of entities’ processing of FOI applications.

Conclusion

Based on the targeted testing of FOI applications made to AGD, DSS and DVA, those agencies generally appear to be providing appropriate assistance to applicants. The selected entities’ ability to search for documents would be improved if they had the capability to electronically search the content of all electronic documents.

The number of exemptions claimed by entities has increased by 68.4 per cent over the last five years. The use of two exemptions in particular has increased substantially.

Across all entities:

- 88 per cent of applications were processed within the required 30 day period;

- the proportion of applications refused has remained fairly constant at about 10 per cent over the last five years;

- the number of exemptions being claimed is increasing, especially in relation to two of the ‘top ten’ exemptions; and

- the number of applications for internal review is trending upwards.

Areas for improvement

There would be merit in DSS and DVA considering whether to develop a manual or other consolidated guidance material for FOI decision-makers and administrators.

3.1 As noted at paragraph 1.23, the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, the Department of Social Services and the Attorney-General’s Department were selected to provide insight into their respective handling of FOI applications.

3.2 It is open to entities to adopt an organisational model for FOI administration which best meets their needs: a small entity with few applications each year would not require a unit dedicated to processing FOI applications. The three selected entities have adopted different organisational approaches to processing FOI applications34:

- In AGD, the Secretary has delegated FOI decision-making powers to Senior Executive Service Officers in the relevant policy area, with a centralised FOI team providing advice and administrative support;

- In DSS, FOI decisions are made by specialised teams located within the department’s legal division with the relevant subject area providing administrative support (such as searching for documents) ; and

- In DVA, personal FOI applications (which form the majority of the entity’s applications) are generally managed by the National Information Access Processing team in the Client Access Branch. Non-personal FOI applications and more complex personal applications are managed by a specialised Information Law team located within the Legal Services and Assurance Branch.

3.3 The number of personal and non-personal FOI applications received by each of the selected entities is shown in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1: FOI applications received, selected entities, 2009–10 to 2015–16

|

Year |

DVA |

AGD |

DSSa |

|||

|

Application type |

Personal |

Non-personal |

Personal |

Non-personal |

Personal |

Non-personal |

|

2009–10 |

5178 |

13 |

26 |

41 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

2010–11 |

4916 |

21 |

50 |

183 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

2011–12 |

4379 |

22 |

102 |

212 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

2012–13 |

4115 |

130 |

58 |

150 |

n/a |

n/a |

|

2013–14 |

3629 |

52 |

78 |

185 |

39 |

87 |

|

2014–15 |

3395 |

41 |

55 |

204 |

92 |

102 |

|

2015–16 |

3318 |

20 |

47 |

175 |

77 |

83 |

Note a: As noted at paragraph 1.23, DSS was created in 2013.

Note: The data relating to the selected agencies relates to all FOI applications they received, not to the targeted sample examined by the ANAO.

Source: ANAO from <https://data.gov.au/dataset/freedom-of-information-statistics>.

3.4 The nature of the entities’ functions are reflected in the relative proportions of personal and non-personal applications: over the period shown, 99 per cent of applications received by DVA were personal, in contrast to AGD (26.6 per cent) and DSS (31.2 per cent).

Do entities provide assistance to applicants?

The targeted testing of FOI applications to AGD, DSS and DVA examined by the ANAO suggested that the selected entities generally met the requirement to assist applicants to lodge applications.

3.5 The ANAO’s analysis of 75 FOI requests made to DVA, AGD and DSS found that entities had generally engaged with applicants in accordance with the FOI Act. However, the ANAO observed a number of instances where each department could have provided applicants with better assistance after lodging requests.35 Conversely, the ANAO also noted an instance in DSS where the department provided the applicant with information which went beyond what had been specifically requested and would have been of substantially more assistance to the applicant than a literal response.

3.6 The FOI Act also requires entities to acknowledge the receipt of all FOI requests within 14 days. There were 68 requests for which an acknowledgment was required.36 Of these, 57 (83.8 per cent) were acknowledged within 14 days, five (three DVA, one AGD and one DSS) were acknowledged outside the statutory timeframe and six requests were not acknowledged (three DVA, two DSS and one AGD). In their acknowledgement receipts, AGD and DVA typically included the date by which a decision was due. It is important that an applicant knows when to expect a decision, so that he or she knows when the application is deemed to have been refused and may then determine whether to apply for a review of the decision. DSS advised the ANAO that it would endeavour to routinely provide applicants with a due date by amending its templates.

Do entities conduct reasonable searches?

The ANAO’s targeted testing of FOI applications to AGD, DSS and DVA showed that the selected entities generally conducted reasonable searches to attempt to locate documents. Entities’ ability to search for relevant documents could be improved were the entities able to electronically search the contents of all documents (rather than just by title).

3.7 The FOI Act provides that entities may refuse a request for access to a document where entities have taken ‘all reasonable steps’ to find a document and the entity is satisfied that it cannot be found or does not exist.

3.8 The ANAO did not replicate the document searches for each of the 75 requests due to the large number of paper and electronic filing systems within each entity, some of which were geographically dispersed; and difficulties in ascertaining which documents may have been added or deleted since the search was originally conducted. Instead, the ANAO examined the entities’ records of their searching processes, including the advice provided by the decision-maker to the applicant about the searches conducted. Across the ANAO’s targeted sample of FOI requests, the degree to which the searching process was documented tended to align with the scope of the request: for example, search processes for broader requests tended to be more thoroughly documented.37 There were a small number of broad requests where the searching process was not documented; in these cases the decision-maker had relied on advice from the line area. Where the request related to specific documents or information, the relevant line area located and provided the relevant documents, or advised that no documents existed.

3.9 Of the three entities, DVA documented less detail associated with its processing of FOI requests, including its searches. Many of DVA’s records (such as files relating to veterans’ benefits) are paper-based. At the time of audit fieldwork, DVA’s FOI documentation was split across its enterprise document management system, email mailboxes and shared drives. During the course of the audit, DVA advised the ANAO that it had been reviewing a number of practices to improve its FOI record-keeping and was in the process of a project to digitise its paper records. In contrast, AGD and DSS retained all FOI records in their electronic departmental record systems.

3.10 Although each of the three selected entities use electronic data and records management systems (EDRMS) which allow for searches by document title, they are not able to readily search the content of the documents themselves. In some instances (such as searching for a particular text string), such a facility might have the potential to reduce both the task of searching for relevant documents and the number of documents in respect of which a decision must be made.

Do entities meet timeliness requirements?

The FOI Act requires that entities determine (make a decision about) applications within 30 days. Between 2011–12 and 2015–16, 88.4 per cent of FOI applications were reported as having been determined within 30 days.

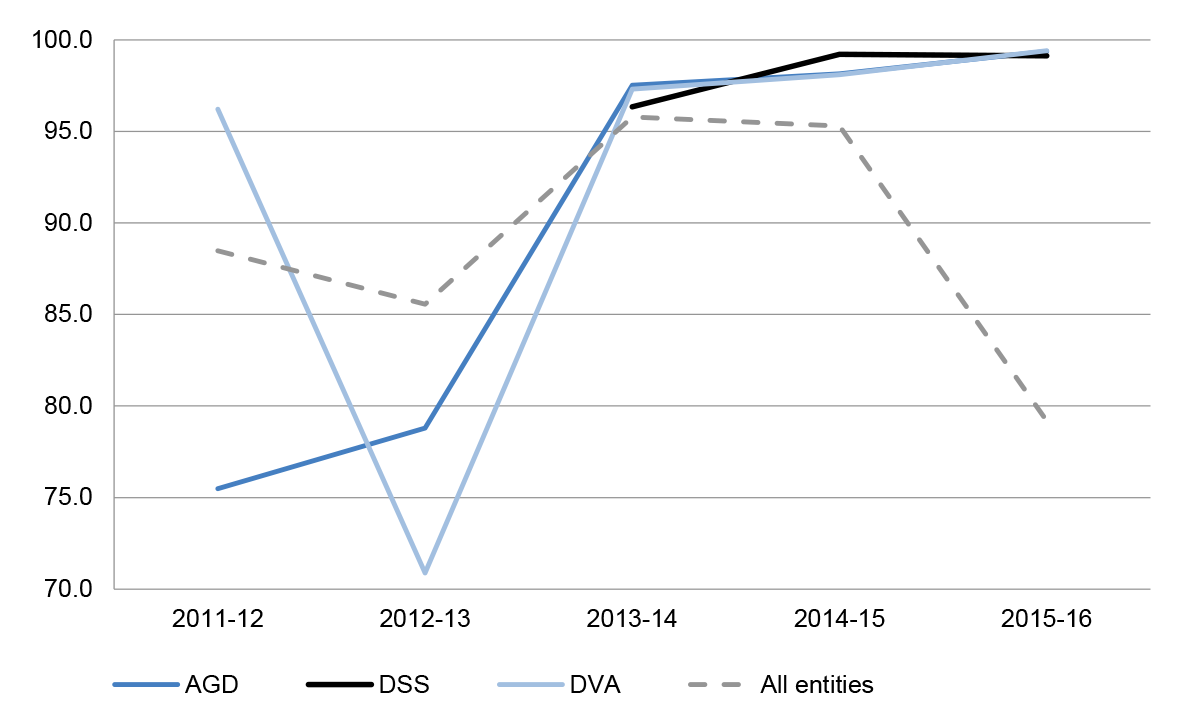

3.11 Section 15(5) of the FOI Act requires entities to ‘determine’ (that is, make a decision on) FOI applications within 30 days of being received.38 Figure 3.1 shows the proportion of FOI applications that were reported by entities as having been determined within the 30 day requirement.

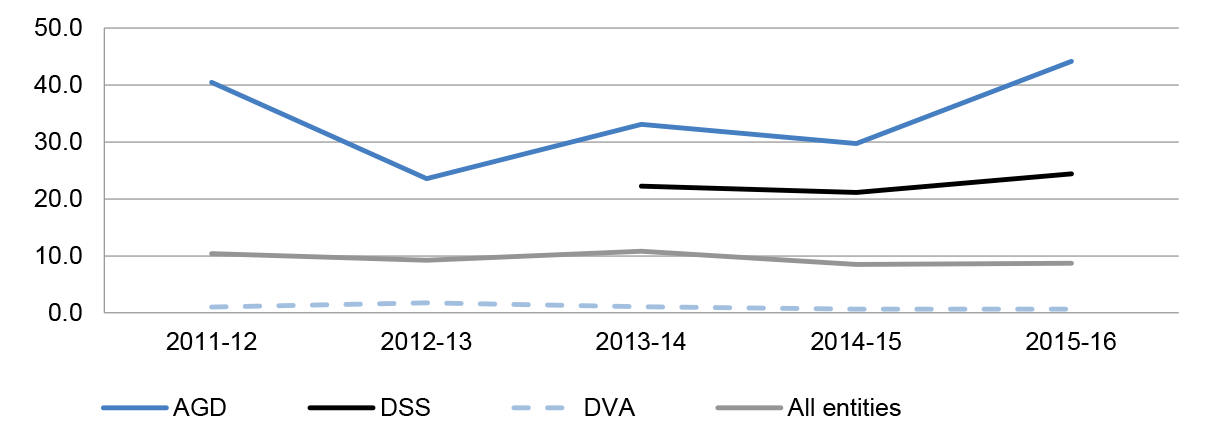

Figure 3.1: Proportion of FOI applications determined within 30 days, selected and all entities, 2011–12 to 2015–16

Source: ANAO from <https://data.gov.au/dataset/freedom-of-information-statistics>.

3.12 The significant drop for ‘all entities’ in meeting the 30 day requirement in 2015–16 is attributable to a single entity (the Department of Immigration and Border Protection).39 If that entity is removed from the ‘all entities’ figure, then more than 94 per cent of FOI applications were reported as having been processed within 30 days for each of the last three years.

Do entities appropriately apply refusals and exemptions and conduct internal reviews?

Based on its targeted testing in selected entities, the ANAO concluded that those entities appropriately applied refusals and exemptions and conducted internal reviews. About 10 per cent of all FOI applications are refused (that is, that access to documents is not given). The number of exemptions (that is, grounds to deny access) claimed over the last five years has increased by 68.4 per cent, noting that an individual FOI claim can be subject to multiple categories of exemption. Over the same period the number of applications increased by 53.4 per cent. The use of the ‘certain operations’ and ‘national security’ exemptions has increased by 318 per cent and 247 per cent respectively.

The number of applications for internal review of FOI decisions increased by 35 per cent from 2014–15 to 2015–16. The proportion of internal review decisions where the original decision was affirmed is about half.

All refusals

3.13 Entities may refuse FOI applications for the following key reasons:

- that the documents are publicly available;

- that the documents do not exist or cannot be found;

- that the application is invalid;40

- that some or all of the documents sought are exempt; and

- that dealing with the request would ‘substantially and unreasonably’ divert the entity’s resources (practical refusal).

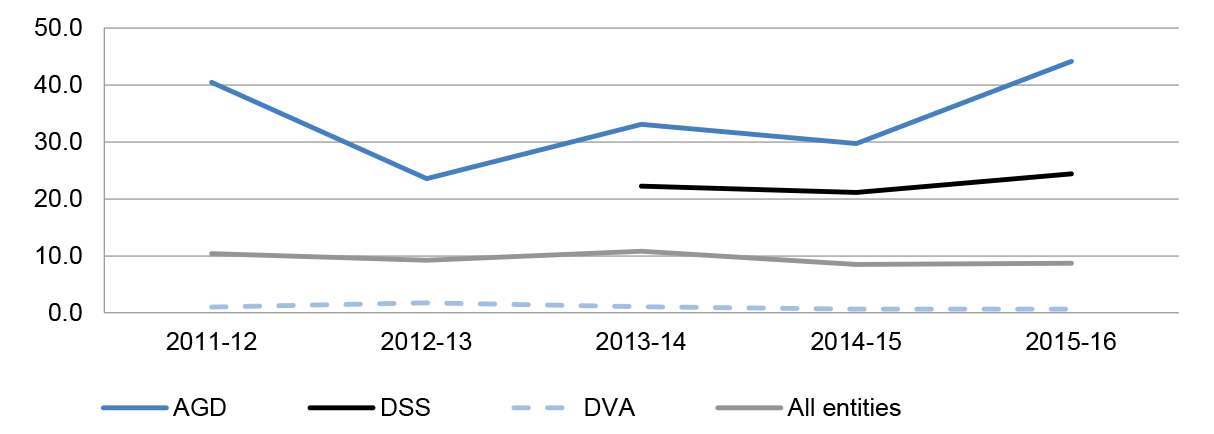

3.14 Figure 3.2 shows the proportion of applications refused for any reason as a proportion of applications received each year. While AGD has a higher proportion of refused applications relative to other entities, this is likely to be attributable to the fact that it has a larger proportion of non-personal applications than other selected entities: conversely, DVA receives a much higher proportion of personal applications, where access is generally granted. The rate of refusals for all entities has remained broadly consistent over the period at about 10 per cent and does not indicate a clear trend.

Figure 3.2: Refusals as a proportion of applications received, selected and all entities, 2011–12 to 2015–16

Note: The data relating to the selected entities relates to all refusals, not to the targeted sample examined by the ANAO.

Source: ANAO from <https://data.gov.au/dataset/freedom-of-information-statistics>.

Practical refusals

3.15 As noted at Case Study 1, s 24(1) of the FOI Act allows an entity to ‘practically refuse’ an application if the work involved in processing it would ‘substantially and unreasonably’ divert the resources of the entity. However, the entity must notify the applicant of its intention to refuse the application and is required to provide the applicant with an opportunity to revise the application (by narrowing its scope, for example). Figure 3.3 shows the proportion of total applications received where entities notified an applicant that it intended to ‘practically refuse’ the application.

Figure 3.3: Practical refusal notifications as a proportion of all applications received, selected and all entities, 2011–12 to 2015–16

Note: The data relating to the selected entities relates to all applications, not to the targeted sample examined by the ANAO.

Source: ANAO from <https://data.gov.au/dataset/freedom-of-information-statistics>.

3.16 Figure 3.3 does not show any clear trend in practical refusals. The relatively low proportion of applications refused by DVA is a reflection of that entity’s relatively larger proportion of applications for personal material (where access is generally granted).

3.17 The proportion of s 24(1) notifications which are subsequently processed after the applicant has had an opportunity to revise the application averages about 30 per cent per year. In numerical terms, from 37 996 applications received in 2015–16, entities made 1 354 notifications of intent to refuse and of those, 402 (29.7 per cent) were subsequently processed.

Exemptions

3.18 As noted at paragraphs 0 and 1.4, there are a total of 18 exemptions and conditional exemptions which may apply to documents being considered for release as a result of an FOI application. The full range of exemptions is explained in more detail in Appendix 3.

3.19 An entity might decide that a single document (or group of documents) attracts more than one exemption. OAIC provides entities with instructions about how to complete their quarterly and annual statistical returns. In relation to exemptions, entities are instructed that for each application, they should count the number of different exemptions claimed. A single document could therefore be claimed to be exempt under several exemptions and multiple documents included in a single application could attract many different exemptions. While it is reasonable to count the numbers of exemptions claimed, this makes comparisons with actual numbers of applications difficult. Consequently, it is more instructive to examine trends in the use of exemptions. Figure 3.4 shows the total number of exemptions claimed in the period 2011–12 to 2015–16.

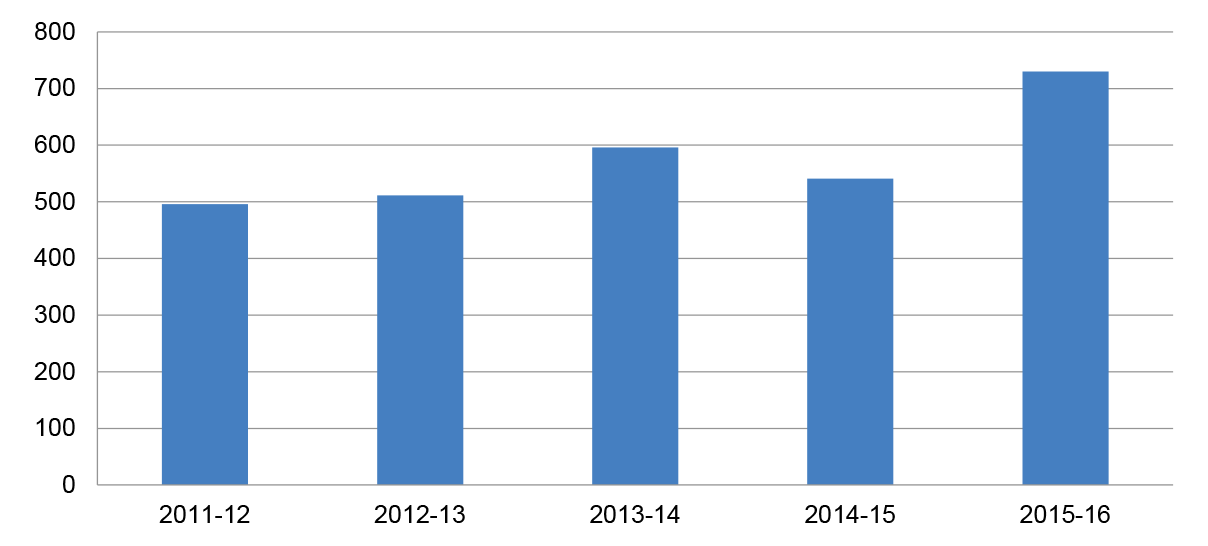

Figure 3.4: Total number of exemptions claimed, all entities, 2011–12 to 2015–16

Source: ANAO from <https://data.gov.au/dataset/freedom-of-information-statistics>.

3.20 The increase in the number of exemptions claimed between 2011–12 and 2015–16 was 68.4 per cent. Over the same period, the number of applications received increased by 53.4 per cent. As an individual FOI claim can be subject to multiple categories of exemption, the data cannot be used to determine whether the growth in the use of exemptions is occurring any faster than the growth in the number of applications.

3.21 The ANAO also examined the growth in the use of particular exemptions. Table 3.2 shows the top 10 exemptions claimed in the period 2011–12 to 2015–16.

Table 3.2: Top ten exemptions claimed, all entities, 2011–12 to 2015–16

|

Exemption |

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

Total |

% of all exemptions |

% increase 2011–12 to 2015–16 |

|

Personal privacy |

3850 |

4489 |

4759 |

5677 |

6030 |

24 805 |

46.1 |

56.6 |

|

Certain operations |

638 |

896 |

1721 |

1663 |

2672 |

7590 |

14.1 |

318.8 |

|

Law enforcement |

995 |

1282 |

1485 |

1461 |

1191 |

6414 |

11.9 |

19.7 |

|

Secrecy |

468 |

699 |

545 |

600 |

818 |

3130 |

5.8 |

74.8 |

|

Business |

400 |

513 |

426 |

518 |

539 |

2396 |

4.5 |

34.8 |

|

Deliberative processes |

332 |

363 |

487 |

566 |

588 |

2336 |

4.3 |

77.1 |

|

National security |

194 |

257 |

456 |

547 |

677 |

2131 |

4.0 |

249.0 |

|

Legal professional privilege |

330 |

304 |

288 |

267 |

346 |

1535 |

2.9 |

4.8 |

|

In confidence |

226 |

248 |

243 |

274 |

243 |

1234 |

2.3 |

7.5 |

|

Trade secrets |

332 |

141 |

126 |

131 |

105 |

835 |

1.6 |

-68.4 |

|

Total top ten |

7765 |

9192 |

10 536 |

11 704 |

13 209 |

52 406 |

97.5 |

70.1 |

|

Top ten as % of all exemptions |

96.7 |

96.8 |

97.7 |

98.0 |

97.7 |

97.5 |

97.5 |

1.0 |

|

All exemptions |

8027 |

9498 |

10 783 |

11 938 |

13 515 |

53 761 |

100.0 |

68.4 |

Source: ANAO from <https://data.gov.au/dataset/freedom-of-information-statistics>.

3.22 Table 3.2 shows that in each year, the top ten exemptions have accounted for 97 per cent to 98 per cent of all exemptions claimed. The greatest growth has been in the use of the ‘certain operations’41 exemption which has increased by more than 300 per cent in the five year period. The use of the ‘national security’ exemption has also increased substantially (by almost 250 per cent).

Internal review of decisions

3.23 As noted at paragraph 2.9, applicants who are dissatisfied with a decision that an entity makes about their application may choose between seeking an internal review by the entity or applying for review to OAIC. Applications for review are split roughly evenly between these two options. Figure 3.5 shows the number of applications for internal review received by all entities over the last five years.

Figure 3.5: Applications for internal review, all entities, 2011–12 to 2015–16

Source: ANAO from <https://data.gov.au/dataset/freedom-of-information-statistics>.

3.24 Figure 3.5 shows that the number of applications for internal review received in 2015–16 increased by 35 per cent from the previous year.

Outcomes of internal reviews

3.25 Under s 54C(2), an internal review of an FOI decision must be conducted by someone other than the person who made the original decision. Although not specifically required, an internal reviewer is usually more senior. As with OAIC reviews (see paragraph 2.18), an internal reviewer may either affirm the original decision, vary it (for example by giving access to some of the documents) or give access in full.

3.26 Figure 3.6 shows the outcomes of internal reviews.42

Figure 3.6: Internal review decision outcomes, all entities, 2011–12 to 2015–16

Source: ANAO from <https://data.gov.au/dataset/freedom-of-information-statistics> and OAIC annual reports.

3.27 Figure 3.6 shows that the proportion of internal review decisions in each category has remained broadly consistent over time.

3.28 The ANAO examined two internal reviews conducted by each of the three selected entities from the 2015–16 financial year. One application for review to DVA was withdrawn as the applicant decided instead to request an OAIC merit review. In accordance with s 54C(2) of the Act, the remaining five reviews were decided upon by a different decision-maker from the one who had made the original decision, and each decision-maker made a further decision based upon inquiries.43 All of the review decisions were made within the statutory timeframe. Four of the reviews affirmed the original decision, and in one case the AGD decision-maker reviewed the application of exemptions to a number of documents and decided to grant access to two additional paragraphs of content.

Do selected entities provide adequate guidance for decision-makers?

Of the selected entities, AGD has a manual which provides guidance for FOI decision-makers and administrators. There would be benefit in DSS and DVA considering whether to develop a manual or other consolidated guidance material.

3.29 As noted at paragraph 2.5, OAIC provides a wide range of guidance material, including comprehensive guidelines published pursuant to s 93A of the FOI Act. However, both the FOI Act and the OAIC guidelines leave scope for the exercise of discretion by entities in some respects, such as whether to charge applicants44 or when it is appropriate to refuse an application on practical refusal grounds (see paragraph 3.15). Further, every FOI application requires a decision-maker to exercise judgement about what documents should (or should not) be released and which, if any, exemptions should be claimed. Consequently, there remains a need for entities to supplement OAIC guidance with material to support FOI decision-makers which is tailored to the particular entity.45 A manual can also contain administrative procedural instructions. Such policy and procedural guidance would help to ensure consistency of process and practice across an entity. AGD has an FOI Procedures Manual while DSS and DVA advised that they do not.

4. Information Publication Scheme

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether selected entities and the OAIC have met requirements relating to the Information Publication Scheme (IPS).

Conclusion

None of the three selected entities fully complied with the FOI Act requirement to publish specific required information as part of the IPS.

None of the three selected entities, nor OAIC, met the FOI Act requirement to review the operation of the IPS in their entity by May 1 2016.

The three selected entities updated their disclosure logs as required, noting that four of 15 required updates were late.

4.1 The Information Publication Scheme (IPS) was introduced into the FOI legislative framework as part of the 2010 reforms. The OAIC FOI guidelines describe the IPS as follows:

The IPS requires agencies to publish a broad range of information on their website and provides a means for agencies to proactively publish other information. Agencies must also publish a plan that explains how they intend to implement and administer the IPS (an agency plan) … The IPS underpins a pro-disclosure culture across government, and transforms the freedom of information framework from one that is reactive to individual requests for documents, to one that also relies more heavily on agency-driven publication of information.

Do entities publish required Information Publication Scheme information?

None of the three selected entities met all of the statutory requirements for information they are obliged to publish as part of the Information Publication Scheme.

4.2 Section 8 of the FOI Act includes specific requirements for entities about what information must be published as part of the IPS. The ANAO assessed the selected entities’ compliance with these requirements. Table 4.1 lists the requirements and shows the ANAO’s assessment of the extent to which they have been met.

Table 4.1: Compliance with IPS publication requirements at May 2017, selected entities

|

Section |

Requirement |

AGD Compliant? |

DSS Compliant? |

DVA Compliant? |

|

8(2)(a) |

Entity Plan |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

8(2)(b) |

Details of the entity structure e.g. in the form of an organisation chart. |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

8(2)(c) |

Functions of the entity including: its decision-making powers; and other powers affecting members of the public. |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

8(2)(d) |

Details of appointments of officers made under Acts other than the APS Act 1999. |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

8(2)(e) |

Information in annual reports prepared by the entity that are laid before the Parliament. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

8(2)(f) |

Arrangements for members of the public to comment on specific policy proposals of the entity. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

8(2)(g) |

Information in documents to which the agency routinely gives in response to requests unless exempt. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

8(2)(h) |

Information held by the entity that is routinely provided to the Parliament in response to requests and orders from the Parliament. |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

8(2)(i) |

Contact details for an officer who can be contacted about access to the entity’s information under the Act. |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

8(2)(j) |

Entity operational information. |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Note: Section 8B of the FOI Act requires that agencies must ensure that the information is ‘accurate, up to date and complete’.

Source: ANAO.

4.3 Table 4.1 shows that while DSS complied with nine of the ten requirements, DVA and AGD complied with seven and five respectively.

Have entities and OAIC reviewed the operation of the Information Publication Scheme?

None of the three selected entities, nor OAIC, met the statutory requirement to review the operation of the Information Publication scheme by 1 May 2016.

4.4 Section 9 of the FOI Act requires each entity, ‘in conjunction with’ OAIC, to review the operation of the IPS in its entity ‘from time to time’. It also required that the first such review must be completed within 5 years of the commencement of the FOI Act. This meant that each entity’s review should have been completed by 1 May 2016. None of the three selected entities, nor OAIC, have undertaken the required reviews.46

4.5 The Independent Review of Whole-of-Government Internal Regulation (see paragraph 1.10) supported the concept of the IPS, provided it did not result in ‘mandating particular publishing requirements which are already otherwise required’ and recommended that:

AGD in consultation with relevant entities consider whether the Information Publication Scheme could be consolidated with other government initiatives for enhancing public accessibility of government information, such as the digital transformation agenda.47

Have selected entities updated their FOI disclosure logs?

Based on the limited number of FOI applications to the selected entities examined by the ANAO, AGD, DSS and DVA had updated their disclosure logs as required except that four of 15 required updates were late.

4.6 Section 11C of the FOI Act requires that when entities have released documents as a result of an FOI application, they are required to publish a ‘disclosure log’ that makes information publicly available that has been released to FOI applicants. Along with the introduction of the IPS, this requirement was introduced to encourage a proactive approach to publishing information and to increase recognition that information held by government is a national resource. Entities are required to publish information on their disclosure logs unless it includes personal or business information, or other information of a kind determined by the Information Commissioner. Entities must publish information on their disclosure log within 10 working days after the FOI applicant was given access to a document. Section 11C provides entities with three options for meeting these requirements:

- making the information available for downloading from the entity’s website;

- linking to another website where the information can be downloaded; or

- giving details of how the information may be obtained.

4.7 The three selected entities were required to publish information for 15 of the 75 FOI requests included in the ANAO’s targeted sample: these were requests for non-personal information, for which documents had been granted in full or in part. In all 15 instances, the relevant entity had updated its disclosure log, although four of the 15 required updates were outside the 10 day limit (by between four and 14 days).

4.8 Entity approaches to the provision of information on their disclosure logs varied, but all accorded with one of the three options described in the Act. On its disclosure log, DSS provided information about requests as well as making electronic copies of the documents or information released to applicants available for the public to download.48 AGD and DVA listed information about requests, with the documents or information available upon request.

4.9 DSS advised that it had adopted a deliberate approach of using the disclosure log to maximise the amount of information it makes available to the public. FOI statistics suggest that there is public interest in DSS’s disclosure log: in 2015–16, DSS reported that it uploaded 19 direct links to documents, and recorded 168 238 unique visitors and 245 297 page views on its disclosure log. DSS advised the ANAO that there was little extra work in making documents available for downloading on its log: in most cases, an electronic copy of the documents or information that had been prepared for provision to the applicant could also be uploaded to the disclosure log.

Appendices

Appendix 1 Entity responses

Appendix 2 OAIC’s freedom of information functions under the Australian Information Commissioner Act 2010

|

Section |

Function |

|

8(a) |

Promoting awareness and understanding of the Freedom of Information Act 1982 and the objects of that Act. |

|

8(b) |

Assisting agencies under section 8Ea of the Freedom of Information Act 1982 to publish information in accordance with the information publication scheme under Part II of that Act. |

|

8(c) |

The functions conferred by section 8Fb of the Freedom of Information Act 1982. |

|

8(d) |

Providing information, advice, assistance and training to any person or agency on matters relevant to the operation of the Freedom of Information Act 1982. |

|

8(e) |

Issuing guidelines under section 93A of the Freedom of Information Act 1982. |

|

8(f) |

Making reports and recommendations to the Minister about: (i) proposals for legislative change to the Freedom of Information Act 1982; or (ii) administrative action necessary or desirable in relation to the operation of that Act. |

|

8(g) |

Monitoring, investigating and reporting on compliance by agencies with the Freedom of Information Act 1982. |

|

8(h) |

Reviewing decisions under Part VIIc of the Freedom of Information Act 1982. |

|

8(i) |

Undertaking investigations under Part VIIBd of the Freedom of Information Act 1982. |

|

8(j) |

Collecting information and statistics from agencies and Ministers about the freedom of information matters. |

|

8(k) |

Any other function conferred on the Information Commissioner by the Freedom of Information Act 1982. |

|

8(l) |

Any other function conferred on the Information Commissioner by another Act (or an instrument under another Act) and expressed to be a freedom of information function. |

Note a: Section 8E allows the Information Commissioner to assist entities to identify and prepare information to be published under the IPS.

Note b: Section 8F allows the Information Commissioner to review entities’ IPS operation and monitor, investigate and report on compliance with IPS requirements.

Note c: Part VII of the FOI Act relates to reviewing entity FOI decisions.

Note d: Part VIIB of the FOI Act allows the Information Commissioner to investigate complaints and conduct ‘own motion’ investigations.

Source: ANAO.

Appendix 3 Exemptions and conditional exemptions under the FOI Act

Table A.1: Exemptions

|

Section |

Detail |

|

33 |

Exempts documents if their disclosure would, or could reasonably be expected to, cause damage to Australia’s national security, defence or international relations, or would divulge information communicated in confidence to the Commonwealth by a foreign government or an international organisation. This includes information communicated pursuant to a treaty or formal instrument on protection of classified information. |

|

34 |