Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of the Fifth Community Pharmacy Agreement

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the development and administration of the Fifth Community Pharmacy Agreement (5CPA), and the extent to which the 5CPA has met its objectives.

Summary

Introduction

1. The Australian Government provides subsidised medicines to Australians and eligible overseas visitors through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS). In 2013–14, the PBS subsidised over 210 million prescriptions at a reported cost to government of some $9.15 billion. The Government also subsidised an additional 12.4 million prescriptions in 2013–14 to the veteran community through the Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (RPBS), at a cost of $397.9 million.

2. Since 1990 the Australian Government has entered into and funded successive five year community pharmacy agreements, at a cost of over $45 billion1, to help maintain a national network of approximately 5460 retail pharmacies as the primary means of dispensing PBS medicines2 to the public. The Government has also used the agreements to fund professional programs, and to establish a funding pool to be drawn on by pharmaceutical wholesalers that can meet specified service standards for supplying PBS medicines to retail pharmacies.

3. The Fifth Community Pharmacy Agreement (5CPA) is the current agreement between the Minister for Health, representing the Commonwealth, and the Pharmacy Guild of Australia (Pharmacy Guild), representing the majority of retail pharmacies currently approved to supply PBS medicines.3 The introduction to the 5CPA states that:

Community pharmacy is an integral part of the infrastructure of the health care system in its role in primary health care through the delivery of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme and related services.

The Fifth Community Pharmacy Agreement

4. To support community access to pharmaceutical services, the 5CPA provides that the Australian Government will deliver some $15.4 billion in funding from 1 July 2010 to 30 June 2015 as follows4:

- $13.8 billion in ‘pharmacy remuneration’5, including various fees for approved pharmacists—the owners of retail pharmacies that dispense PBS and RPBS subsidised medicines to the public6;

- $663 million for several categories of government funded professional programs7; and

- $950 million to be shared among eligible pharmaceutical wholesalers from a Community Service Obligation (CSO) funding pool, an arrangement which generally requires participating wholesalers to be able to supply the full range of PBS items to any retail pharmacy in Australia within 24 hours at an agreed price.

5. One of the key objectives of the 5CPA negotiations was to achieve savings to contribute to the structural repair of the Commonwealth Budget as there had been high cost growth under the 4CPA (an average growth of 9.4 per cent per year) that was due, in part, to a $1.1 billion transitional structural adjustment package (financial assistance) to assist pharmacies adjust to the introduction of Price Disclosure in 2007.8

6. The 5CPA anticipates that the initiatives covered by the agreement will result in $1 billion in government savings.9 The major savings initiatives were:

- cessation of the PBS Online incentive payment ($417.7 million);

- freezing the dispensing fee for two years ($281.5 million);

- cessation of underperforming professional programs ($226.4 million);

- reduction in private hospital pharmacy remuneration ($35.3 million); and

- freezing the CSO Funding Pool for one year ($19.2 million).

7. The 5CPA also references the Australian Government’s Pharmacy Location Rules (Location Rules), which regulate where new pharmacies that dispense PBS prescriptions may open and where existing pharmacies may relocate.

8. Six broad ‘principles and objectives’ are specified in the 5CPA:

i. Ensure a fair Commonwealth price is paid to Approved Pharmacists for providing pharmaceutical benefits while maximising the value to taxpayers by encouraging an effective and efficient community pharmacy network.

ii. Ensure that the Programs are patient-focused and target areas of need in the community including continued improvement in community pharmacy services provided to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

iii. Ensure transparency and accountability in the expenditure of the Funds.

iv. Promote the sustainability and efficiency of the PBS within the broader context of health reform and ensuring that community resources continue to be appropriately directed across the health system, while also supporting the sustainability and viability of an effective community pharmacy sector.

v. Maintain a co-operative relationship between the Commonwealth and the Guild.

vi. Ensure the Location Rules work for the benefit of the Australian community including increased access to community pharmacies for the population of rural and remote areas.

9. The 5CPA is a complex multi-part agreement underpinned by a number of further agreements between the Department of Health (Health) and the other entities involved in its administration, including: the Department of Human Services (Human Services); the Pharmacy Guild of Australia10; and Australian Healthcare Associates (AHA). The Pharmacy Guild and AHA are non-government entities.

Administrative arrangements

10. The 5CPA was developed and negotiated by Health, which has overarching responsibility for its administration, and agreed by government. The Pharmaceutical Benefits Division within Health has responsibility for policy advice on all elements of the 5CPA, while the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) is responsible for policy advice on the RPBS, including RPBS pharmacy remuneration.

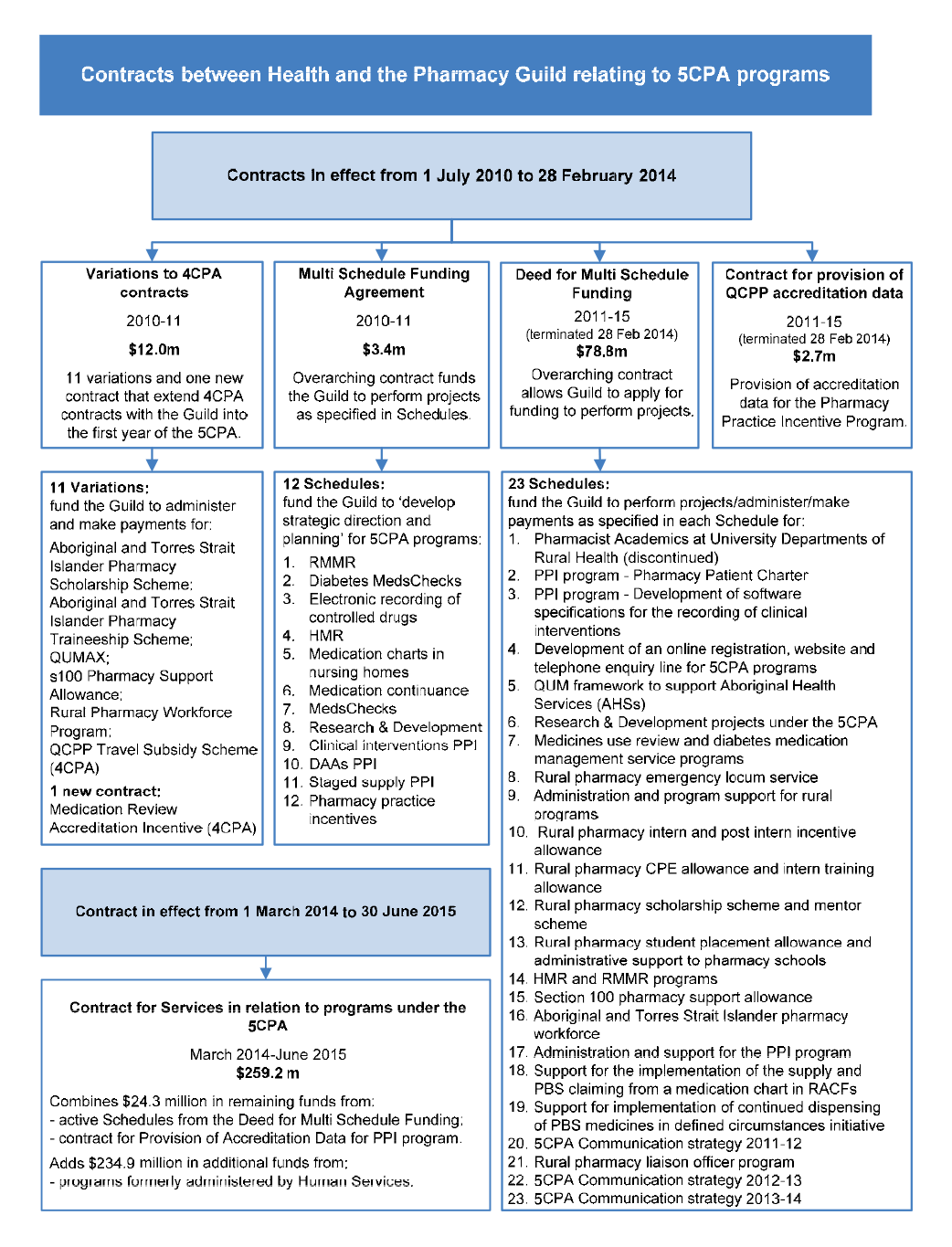

11. Until 1 March 2014, Human Services administered most 5CPA professional programs on behalf of Health (valued at $583 million), while the Pharmacy Guild administered some of the smaller programs (valued at $67 million). On 1 March 2014, Health transferred responsibility for the 5CPA professional programs administered by Human Services to the Pharmacy Guild, which now administers all 5CPA professional programs on behalf of Health.11

12. In respect of the 5CPA, the Pharmacy Guild is variously:

- an industry association and advocate acting on behalf of retail pharmacy owners, making representations to government and public inquiries, and conducting public campaigns;

- a publicly funded administrator under the 5CPA, at times acting as the Department of Health’s agent;

- a recipient of Commonwealth grants relating to certain 5CPA professional programs12;

- an owner of business enterprises that sell products and services to pharmacies on a commercial basis—with some products and services relating to 5CPA programs and activities; and

- an advisor to Health, through its co-membership of the overarching 5CPA governance body13 and under its contracts with the department.

13. Human Services processes pharmacy claims for reimbursement of PBS and RPBS dispensing on behalf of Health and DVA respectively, and accesses relevant Health and DVA appropriations for this purpose. The administration of the CSO Funding Pool is outsourced by Health to Australian Healthcare Associates (AHA), a private company based in Melbourne. AHA collects data from participating CSO pharmaceutical wholesalers and calculates their monthly share of the funding pool; with Health paying CSO wholesalers on the basis of AHA’s advice.

14. A summary of the five year budget and staffing for key entities involved in administering the 5CPA, before and after the transfer of 5CPA professional programs from Human Services to the Pharmacy Guild in March 2014, is shown in Table S.1.

Table S.1: Five year budget for 5CPA administration

|

Entity |

2010–15 budget before 1 March 2014 |

2010–15 budget after 1 March 2014 |

||

|

|

Staffing (ASL) |

Budget ($m) |

Staffing (ASL) |

Budget ($m) |

|

Healtha |

237.8 |

30.8 |

239.7 |

31.2 |

|

Human Services |

273.5 |

41.8 |

150.1 |

25.5c |

|

Veterans’ Affairs |

1.0 |

0.1 |

1.0 |

0.1 |

|

Pharmacy Guildb |

- |

29.3 |

- |

31.2 |

Source: Health, Human Services, Pharmacy Guild and Veterans’ Affairs information.

Notes: An entity’s administrative budget may cover a range of administrative costs in addition to staffing, such as ICT, property, legal and miscellaneous costs. ASL is average staffing level.

- See Table 1.7 for Health’s disaggregated annual staffing and administrative expenditure.

- The Pharmacy Guild was unable to provide ASL figures. See Table 5.2 for a detailed breakdown of administrative and program funding as specified in Health contracts with the Pharmacy Guild.

- Human Services’ ongoing budget was reduced by the equivalent of $16.4 million over five years following the transfer of 5CPA professional programs to the Pharmacy Guild. Prior to the transfer of functions, Human Services had expended $14.3 million. Health and the Pharmacy Guild received the unexpended $2.1 million portion of Human Services’ original budget.

Audit objective, criteria and methodology

Audit objective and scope

15. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the development and administration of the Fifth Community Pharmacy Agreement (5CPA), and the extent to which the 5CPA has met its objectives. The audit examined the development and negotiation of the 5CPA by the then Department of Health and Ageing (now the Department of Health), and the administration of the 5CPA by Health. The audit also examined aspects of the 5CPA that were implemented by the Department of Human Services (Human Services) and the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA).

16. While the ANAO did not examine the Pharmacy Guild of Australia’s administration of 5CPA professional programs, the audit refers to aspects of its involvement relating to the development, negotiation and administration of the 5CPA.

17. The Pharmacy Location Rules are not examined in this performance audit. They were considered in 2014 by the report of the National Commission of Audit14 and the draft report of the National Competition Policy Review.15

Criteria

18. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- the 5CPA provides transparent and accountable remuneration arrangements for the dispensing of Commonwealth pharmaceutical benefits, which achieve value for money, consistent with Government policy;

- the 5CPA’s funding and savings commitments are being met;

- the additional programs and services funded under the 5CPA are managed effectively and provide value for money; and

- the 5CPA performance framework enables an assessment of the extent to which the 5CPA is meeting its objectives.

Methodology

19. The audit methodology included:

- interviewing staff from Health, Human Services and DVA;

- extracting pharmacy claims and payment records from Health and Human Services databases;

- reviewing relevant documentation, including departmental files, briefings, legal advice, program guidelines, monitoring and reporting systems, reviews, evaluations and correspondence;

- consulting stakeholders and peak bodies, including the Pharmacy Guild; and

- reviewing over 100 stakeholder submissions received by the ANAO through its citizen’s input facility.

Overall conclusion

20. The Fifth Community Pharmacy Agreement (5CPA) continues the Australian Government’s policy approach, over 25 years, to enter into a funding agreement with the Pharmacy Guild of Australia (Pharmacy Guild)—representing the majority of retail pharmacy owners—to help maintain a national network of some 5460 retail pharmacies as the primary means of dispensing PBS medicines to the public. The 5CPA also provides for access to patient services that may be delivered by retail pharmacies or consultant pharmacists. The parties have entered into five successive agreements, valued at over $45 billion, since 1990.

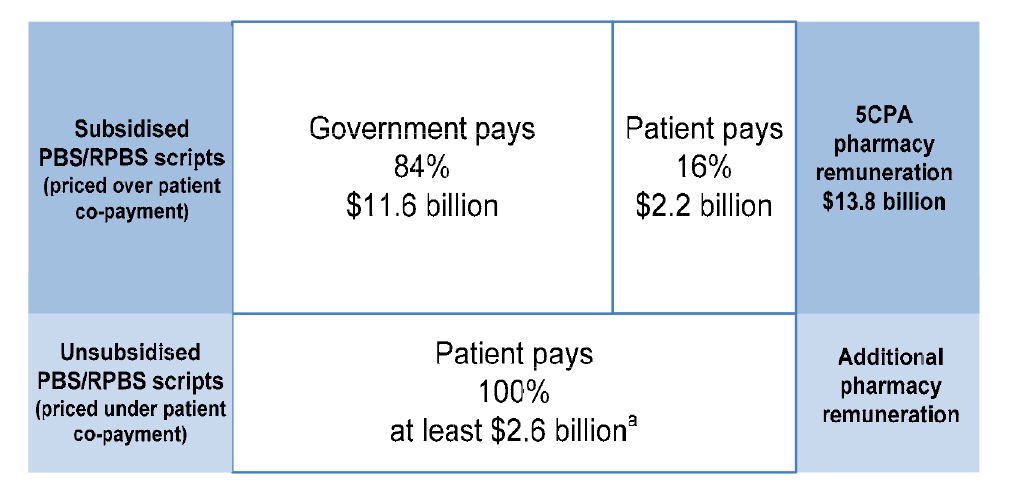

21. The $15.4 billion 5CPA provides that the Australian Government will deliver, over five years from 2010 to 2015: $13.8 billion in ‘pharmacy remuneration’, including various fees for approved retail pharmacies; $663 million in funding for professional programs; and a funding pool of $950 million to be drawn on by eligible pharmaceutical wholesalers to provide PBS medicines to pharmacies in a timely manner and at an agreed price. Although actual expenditure on the components of pharmacy remuneration is demand driven—depending on the number of PBS and RPBS medicines prescribed by doctors—the 5CPA commits the Government to delivering a fixed sum of money.16 The 5CPA also states that the initiatives covered by the agreement will result in $1 billion in savings to government.

22. The 5CPA is the head agreement in a complex scheme of legal, financial and administrative arrangements involving both government entities and third parties in its implementation. The 5CPA is underpinned by further agreements, principally between the Department of Health (Health) and the Department of Human Services (Human Services), the Pharmacy Guild of Australia and Australian Healthcare Associates (AHA). The arrangements were developed and negotiated by Health, which has overarching responsibility for the 5CPA’s administration, and agreed by Government.

23. Overall, the Department of Health’s administration of the Fifth Community Pharmacy Agreement has been mixed, and there is a limited basis for assessing the extent to which the 5CPA has met its key objectives, including the achievement of $1 billion in expected savings. The department developed and negotiated a complex agreement and related contracts with the Pharmacy Guild in a timely manner, enabling the 5CPA to be signed by the Health Minister and Pharmacy Guild on 3 May 2010, prior to the expiry of the 4CPA on 30 June 2010. However, a number of key government negotiating objectives for the 5CPA were only partially realised and there have been shortcomings in key aspects of Health’s administration at the development, negotiation and implementation phases.

24. The 5CPA states that the initiatives covered by the agreement will result in $1 billion in savings over the term of the agreement. The 2010–11 Budget Papers17 clarified that the $1 billion in savings is a gross figure, and after taking into account approved additional expenditure of $0.4 billion, net savings were estimated to be $0.6 billion.18 However, ANAO analysis indicates that the net savings estimated before the agreement was signed were closer to $0.4 billion, due to shortcomings in the department’s 5CPA estimation methodology.19 The principal issues relate to: unexplained increases in the baseline cost of professional programs; the application of inappropriate indexation factors; and the treatment of patient co-payments. In particular:

- The baseline budget for 5CPA professional programs in the Commonwealth forward estimates was $638.7 million (before adjusting for the negotiated 5CPA savings and spending measures). However, Health’s records showed that the approved baseline budget for 5CPA professional programs was only $511.6 million, and there was no documentary evidence of authority to increase the 5CPA baseline budget in the forward estimates by $127.1 million.

- The official indexation factors released by the then Department of Finance and Deregulation (Finance)20 were not utilised in estimating 5CPA savings, resulting in an overestimate of 5CPA savings of approximately $43.2 million.

- Health advised, in the course of this audit, that the estimated savings for the 5CPA incorrectly included $42.7 million in co-payments made by patients to pharmacies for the receipt of pharmaceutical benefits. Co-payments are a private contribution to the cost of PBS medicines, which are not a cost to government.

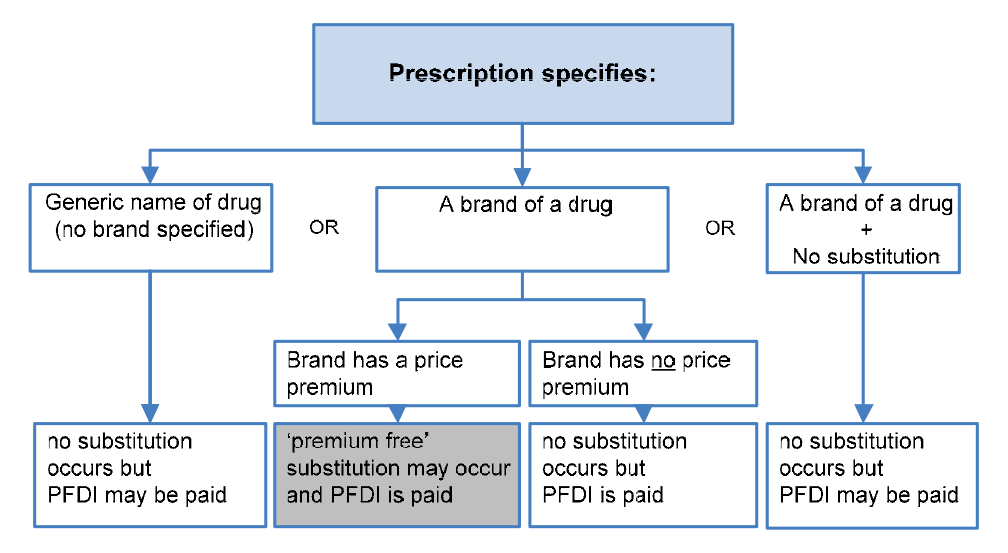

25. Actual pharmacy remuneration (paid by government and patients) in the first four years of the 5CPA aligned closely with the commitment made originally in the 5CPA.21 However, during the life of the agreement there have been two estimates variations (in 2011 and 2013) relating to the cost of one component of pharmacy remuneration—the Premium Free Dispensing Incentive22—which increased the expected cost to government of pharmacy remuneration by $292 million23 and also impacted the level of savings from the 5CPA.

26. In addition to the shortfall in anticipated savings, a number of the Government’s other strategic negotiating objectives were only partially realised, as previously indicated. In this context, the then Government and department considered that the 5CPA offered an opportunity to improve health outcomes and value for money by restructuring pharmacy remuneration arrangements ‘to diminish their link to the price of PBS medicines’. The Commonwealth anticipated doing so by shifting financial incentives from the volume driven sale of medicines to the delivery of value-adding professional services. However, the structure of pharmacy remuneration remained essentially unchanged from the 4CPA to the 5CPA—based on defined mark-ups to the base price of pharmaceuticals and the addition of a variety of fees. Further, key wholesaler and pharmacy mark-ups continued at previous rates.

27. A further Commonwealth negotiating objective, which Ministers considered to be ‘non-negotiable’, related to obtaining access from pharmacies to the full range of PBS data, including information relating to prescriptions that cost less than the general patient co-payment. This information would help the Commonwealth determine actual PBS pharmacy remuneration from all sources, including patients, and the total volume and cost of the PBS to both government and consumers. This objective was partially realised—while the 5CPA made provision for pharmacies to provide certain prescription information from 1 April 2012, it did not make provision for the receipt of cost information.

28. Another key government negotiating objective for the 5CPA was to support information technology systems that are fully interoperable with broader e-health systems. However, the two Prescription Exchange Services (PESs) that were approved by Health for the purpose of downloading electronic prescriptions by pharmacies, did not have systems that were interoperable. Government funding for the Electronic Prescription Fee (EPF) was subsequently re-allocated to pay the PESs directly to make their systems interoperable.

29. Six broad principles and objectives were included in the 5CPA.24 Limited departmental information25, plus shortcomings in Health’s performance reporting and 5CPA evaluation framework, mean that the department is not well positioned to assess whether the Commonwealth is receiving value for money from the agreement overall, or performance against the six principles and objectives. While some aspects of the agreement will be evaluated, the 5CPA evaluation framework does not make provision for reviews of the agreement’s two major financial components—pharmacy remuneration ($13.8 billion) and Community Service Obligation (CSO) payments to pharmaceutical wholesalers ($950 million). Pharmacy remuneration, which lies at the heart of the 5CPA and previous community pharmacy agreements—accounting for some 90 per cent of funding delivered under the current agreement—has not been fully reviewed since 1989.26 There is scope to improve the performance and evaluation frameworks for the 5CPA and the next community pharmacy agreement.

30. In addition to shortcomings in 5CPA costings, performance reporting and the evaluation framework, this audit identified scope for improvement in key aspects of the department’s general administration which covered the 5CPA’s development, negotiation and implementation phases. The key issues relate to: the clarity of the 5CPA and related public reporting; record-keeping; the application of financial framework requirements; risk management; and seeking Ministerial approvals. In particular:

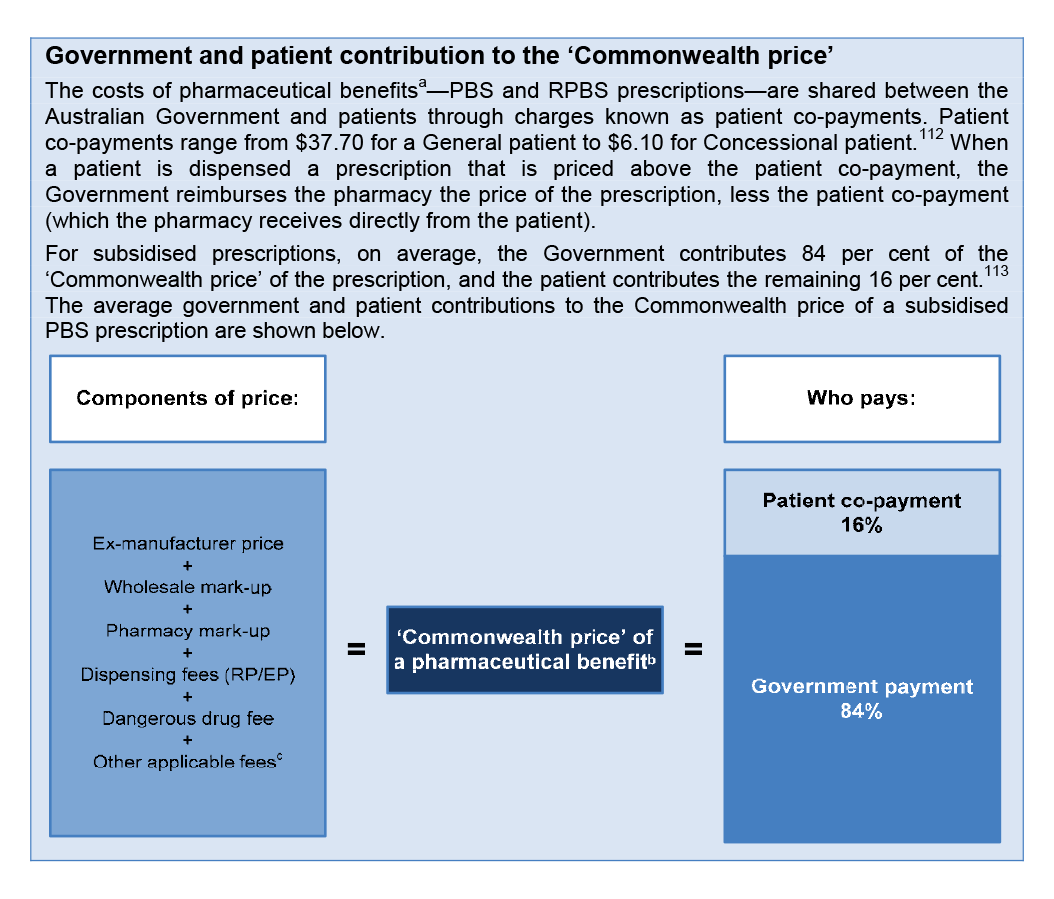

- The 5CPA does not clearly document expected net savings under the agreement, and there is no straightforward means for the Parliament and other stakeholders to be informed of the expected or actual cost of key 5CPA components. Specifically, the agreement does not document that some $2.2 billion of the $13.8 billion that the Commonwealth ‘will deliver’ for pharmacy remuneration is sourced from patient co-payments, which are not a cost to government.27 Similarly, the department’s annual report aggregates the cost of pharmacy remuneration (expenditure on services) with the cost of PBS medicines (expenditure on products), without differentiating between the two types of expenditure.

- There were persistent shortcomings in departmental record-keeping relating to the 5CPA. Health did not keep a formal record of its meetings with the Pharmacy Guild during the 5CPA negotiations, and did not document its subsequent discussions with the Guild on the negotiation of related contracts. Given the significance of the issues under negotiation, the decision not to prepare an official record of discussions was not consistent with sound practice, as shortcomings in record-keeping can affect a government entity’s capacity to discharge advisory, accountability and contract management obligations.

- The department did not assess whether financial framework requirements would apply to Pharmacy Guild officials when making payments of public money pursuant to the administration of 5CPA professional programs, resulting in a risk of non-compliance with legislative requirements. In designing and implementing complex administrative arrangements, it is important to consider relevant resource management requirements at the design stage, so as to avoid potential compliance and reputational risks.

- The 5CPA provides flexibility to re-allocate money between the various professional programs funded under the agreement, subject to Ministerial approval. However, at times the department has re-allocated funds without prior Ministerial approval, including to a $5.8 million communication strategy to be delivered by the Pharmacy Guild. The communication strategy is not a professional program, but was nonetheless funded mainly from professional program allocations.

- Further, Health did not secure Ministerial approval before re-allocating $7.3 million of funding originally approved by Ministers as a component of pharmacy remuneration—the Electronic Prescription Fee (EPF)—to other purposes, including financial assistance paid to Prescription Exchange Services28 and $896 110 to the Pharmacy Guild to increase pharmacies’ understanding, awareness and uptake of EPF. As a consequence, in the first three years of the 5CPA some 80 per cent of EPF payments were not paid to pharmacies but were instead used to fund other activities. While Health advised the ANAO that discussions were held with the Minister’s office, documented evidence to support this was not available.

31. The 5CPA is a substantial agreement that is integral to the parties achieving shared objectives—the maintenance of a national network of retail pharmacies as the primary means of dispensing PBS medicines to the public, and providing professional services to patients. Features of the 5CPA include complexity in policy design and administrative arrangements, and a key lesson of this audit is the importance of identifying and treating risks at the earliest opportunity.29 The successful implementation of complex programs requires active management and a disciplined and co-ordinated approach to managing risks and challenges through the program life cycle—including the development, costing, negotiation and implementation phases. Further, there is a need to ensure that there is appropriate authority for revised positions and outcomes when events do not unfold according to expectations.

32. The ANAO has made eight recommendations aimed at improving the overall administration of the 5CPA and informing the development of the next community pharmacy agreement. Seven recommendations are directed to Health, and relate to: the development of costings; improving the clarity of the next agreement and related public reporting; record-keeping; and improving performance information. A further recommendation directed to Health, Human Services and DVA focuses on improving the accuracy of Health’s calculation of pharmacy remuneration for reporting and evaluation purposes.

Summary of entity responses

33. The proposed audit report was provided to the Department of Health, and extracts were provided to the Department of Human Services, the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, the Department of Finance, the Pharmacy Guild of Australia and MediSecure Limited. Entities’ summary responses are included below and full responses are included at Appendix 1.

Health

34. The Department agrees with the Recommendations of the Report.

35. The Department welcomes the Report as an opportunity to further review the administration and processes for community pharmacy agreements. The Department acknowledges there is scope to realise further improvement in the effective and efficient administration of these agreements and welcomes the recommendations as a platform for ongoing development of future community pharmacy agreements and transparent engagement with the pharmacy sector.

36. I am pleased the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) acknowledged a number of the significant outcomes of the negotiations and implementation of the Fifth Community Pharmacy Agreement (the Agreement) including, but not limited to, the negotiations having been completed on-time for a 1 July 2010 commencement of the Agreement, a 70% reduction in polypharmacy and 50% reduction in medication errors due to the introduction of the National Residential Medication Chart, and the successful implementation of the Continued Dispensing initiative. Further, the Report accurately notes the complexity of the Agreement and its subsidiary arrangements and the pharmacy sector, as one component interacting with a more complex pharmaceutical sector and a broader health care system.

37. I am also pleased to advise that the Department has already implemented a range of improvements relating to issues identified in this Report and previous draft reports. For example, enhancements to financial modelling processes have been implemented to separately report on the cost impacts to government and patients. This will also enable the Department to revise its public financial reporting to include the cost of each major component of pharmacy remuneration in the future. I also note that risk, probity and legal plans are already in place for the anticipated negotiation of a future agreement along with a recording framework for key decisions throughout the negotiations.

Human Services

38. The Department of Human Services agrees with the findings and conclusions contained in the extract of the report provided. It agrees with ANAO audit Recommendation Number 4 in the extract and will support the Departments of Health and Veterans’ Affairs in their determination of reporting requirements on the cost of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme and the Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme expenditure on products.

Veterans’ Affairs

39. The Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) agrees with the report’s Recommendation Number 4, that the Department of Health (DoH) and DVA work closely with the Department of Human Services (DHS) to develop and refine processes for capturing and reporting data on pharmacy remuneration. DVA has already collaborated successfully with DoH and DHS across a number of key areas. DVA is confident that future projects centred on ensuring the exchange and use of accurate data will result in positive outcomes.

40. In addition to accepting the report’s recommendation, DVA confirms its intent to review the legislative instrument that establishes the Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (RPBS) in order to clarify pricing arrangements for pharmaceutical benefits. The RPBS is fundamental to DVA’s commitment to ensuring the health and wellbeing of eligible veterans and their dependents and the Department welcomes any recommendations to improve the Scheme’s operation.

Pharmacy Guild of Australia

41. The Pharmacy Guild of Australia (the Guild) welcomes the audit of the Administration of the Fifth Community Pharmacy Agreement (5CPA).

42. As the organisation representing the majority of community pharmacy owners, the Guild has a statutory responsibility under the National Health Act to negotiate with the Commonwealth the remuneration for pharmacies for dispensing PBS medicines. The Guild also plays a key role in the oversight and administration of the professional programmes funded under the community pharmacy agreements, working in partnership with the Department of Health, in consultation with a wide range of industry, consumer and other stakeholders.

43. The Guild takes these responsibilities very seriously. In successive agreements, the Guild has assisted the Commonwealth in facilitating opportunities for pharmacies and pharmacists to play an enhanced role in delivering the objectives of the National Medicines Policy through the provision of an expanding range of professional services, underpinned by nationally accredited quality assurance standards and enabled by leading-edge information technology platforms and systems.

44. The Guild considers that the audit has provided an important opportunity to scrutinise the administration of the 5CPA and will continue to work constructively with the Commonwealth and all stakeholders in ensuring that the next agreement provides maximum benefit to community pharmacy, the pharmacist profession, taxpayers, and, most importantly, the Australian public which relies on these vital PBS medicines and health care services.

MediSecure Limited

45. Our overall comments are that this audit report appears to have been well researched and has brought clarity and simplicity to the complex and convoluted arrangements that constitute the publicly funded support mechanisms for the delivery of medicines to the Australian community. I have worked in this space for 15 years and during that time have not seen a document that is as well researched. We congratulate the Auditor-General’s team on the quality and breadth of the extract we have seen.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 2.32 |

To clarify the nature of financial commitments entered into by the Australian Government, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Health presents, in key documents, estimated government payments and patient payments for both subsidised and unsubsidised Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme and Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme medicines. Health response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.2 Paragraph 2.55 |

To provide assurance regarding the basis of costings for the next community pharmacy agreement, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Health applies the relevant forecast indexation factors released by the Department of Finance. Health response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.3 Paragraph 2.78 |

To improve its ability to satisfy accountability requirements and capacity to protect the interests of the Commonwealth in the event of disputes or legal action, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Health:

Health response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.4 Paragraph 3.71 |

To improve the accuracy and transparency of reporting on Australian Government expenditure under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme and the Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, the ANAO recommends that the Departments of Health, Veterans’ Affairs and Human Services liaise on the collection, recording and sharing of information regarding payments to suppliers, so as to clearly identify the actual cost of medicines and the components of pharmacy remuneration. Health response: Agreed. Veterans’ Affairs response: Agreed. Human Services response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.5 Paragraph 5.30 |

In order to effectively discharge its advisory, accountability and contract management obligations in a timely manner, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Health reviews its record keeping arrangements for the Fifth Community Pharmacy Agreement and the next community pharmacy agreement. Health response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.6 Paragraph 5.67 |

To improve transparency in agreement-making, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Health documents anticipated levels of Australian Government funding for third party administration for the next community pharmacy agreement. Health response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.7 Paragraph 6.12 |

To improve transparency and the quality of program performance reporting, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Health reports annually on the actual cost of each major component of the Fifth Community Pharmacy Agreement and the next community pharmacy agreement, including pharmacy remuneration, CSO wholesaler payments and professional programs. Health response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No.8 Paragraph 6.28 |

To inform decision-making and the assessment of outcomes by stakeholders, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Health reviews performance reporting to improve alignment between the next community pharmacy agreement and public reporting against the program objectives, deliverables and KPIs relating to the department’s Program 2.1 and Program 2.2. Health response: Agreed. |

1. Introduction

This chapter outlines the background, scope and objectives of the Fifth Community Pharmacy Agreement (5CPA); the policy, legal and administrative framework relating to the 5CPA; and the audit objective, criteria and methodology.

Background

1.1 The Australian Government provides subsidised medicines to Australians and eligible overseas visitors through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS). In 2013–14, the PBS subsidised over 210 million prescriptions at a reported cost to government of some $9.15 billion.30 The Government also subsidised an additional 12.4 million prescriptions in 2013–14 to the veteran community through the Repatriation Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (RPBS), at a cost of $397.9 million.31

1.2 Since 1990, the Australian Government and the Pharmacy Guild of Australia (Pharmacy Guild)32 have entered into successive five-year agreements known as community pharmacy agreements. In the context of the agreements, ‘community pharmacies’ are retail pharmacies approved under the National Health Act 1953 (the National Health Act) to supply PBS medicines to the public. The current agreement is the fifth (the 5CPA), and is intended to operate from 2010 to 2015. While the main purpose of the agreements has been to set out remuneration arrangements for the owners of retail pharmacies that dispense PBS prescriptions, the scope of agreements has progressively broadened to establish a range of government funded professional programs (such as medication reviews), and a funding pool for pharmaceutical wholesalers that meet the requirements of the Community Service Obligation (CSO), which generally requires participating wholesalers to be able to supply PBS items to any retail pharmacy in Australia within 24 hours. Community pharmacy agreements have also referenced the Australian Government’s Pharmacy Location Rules (Location Rules), which regulate where new pharmacies that dispense PBS prescriptions may open and where existing pharmacies may relocate.

Table 1.1: The origin of community pharmacy agreements

|

Community pharmacy agreements—background |

|

The Australian Government has reimbursed pharmacy owners for dispensing PBS items to the public since the PBS was first introduced.a From 1953 to 1976, the Minister for Health was empowered under Section 99 of the National Health Act to determine pharmacy remuneration for PBS dispensing. In 1980, the Australian Parliament’s Joint Committee of Public Accounts recommended the establishment of an independent Tribunal to determine pharmacy remuneration for PBS dispensing.b In 1981, the Pharmaceutical Benefits Remuneration Tribunal (the Tribunal) was established under Section 98A of the National Health Act, and operated independently of the Government and the Pharmacy Guild. In 1989, after examining surveys into pharmacies’ dispensing costs, the Tribunal concluded that pharmacy owners were being over-remunerated for dispensing PBS medicines.c The Tribunal decided to change pharmacy remuneration by abolishing the mark-up then applying on PBS medicines, and reducing the dispensing fee. The Pharmacy Guild opposed this decision. The then Minister for Health subsequently negotiated directly with the Pharmacy Guild, and in 1990, entered into the first Community Pharmacy Agreement. The National Health Act was also amended to require the Tribunal to give effect to the terms of any pricing agreementd between the Minister for Health and the Pharmacy Guild (or another organisation representing a majority of retail pharmacy owners approved to supply PBS items).e |

Notes:

- C Sloane, A History of the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme 1947–1992, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, 1995, pp. 52–59.

- Joint Committee of Public Accounts, Report 182: Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme-Chemists’ Remuneration, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, 1980, p. xiii. In this inquiry the Committee examined and reported on the reasons for a significant excess payment by the Department of Health to chemists in respect of their remuneration under the PBS between 1973 and 1980. The Committee also examined the concurrent excess payments made by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs to chemists under the RPBS. The combined total of overpayments was estimated at approximately $253 million.

- Pharmaceutical Benefits Remuneration Tribunal, Data Base Inquiry Final Report, Canberra, 28 August 1989.

- The National Health Act provides that: ‘…where the Minister (acting on the Commonwealth’s behalf) and the Pharmacy Guild of Australia or another pharmacists’ organisation that represents a majority of approved pharmacists have entered into an agreement in relation to the manner in which the Commonwealth price of all or any pharmaceutical benefits is to be ascertained for the purpose of payments to approved pharmacists in respect of the supply by them of pharmaceutical benefits, the Tribunal, in making a determination under subsection 98B(1) while the agreement is in force, must give effect to the terms of that agreement…’, Section 98BAA(1), National Health Act 1953.

- The Tribunal restored the previous mark-up and dispensing fee on 29 December 1989. The reason the Tribunal gave for revoking its previous determination was, among other things, ‘the Tribunal’s concern to ensure as far as possible that the fees fixed are not only fair, just and equitable but are clearly perceived to be so’. Pharmaceutical Benefits Remuneration Tribunal, Determination and Report Fourteenth Inquiry, Canberra, 25 June 1990.

1.3 The overall cost of successive community pharmacy agreements has been over $45 billion. While actual costs of the agreements have not been publicly reported, Health advised the ANAO that the value of community pharmacy agreements (CPAs) was: 1CPA ($3.286 billion); 2CPA ($5.497 billion); 3CPA ($8.804 billion); 4CPA ($12.158 billion). The original estimated cost of 5CPA was $15.384 billion, which Health has since revised to $15.610 billion as reported in November 2014.

Pharmaceutical services

1.4 The use of a medicine is the most common health intervention in Australia.33 Of the 286 million prescriptions dispensed annually from retail pharmacies in Australia34, approximately 269 million (94 per cent) are PBS or RPBS prescriptions.35 Of these 269 million prescriptions, some 208 million (77 per cent) attract a government subsidy, and the rest are priced below the patient co-payment.36

Role of pharmacists

1.5 A pharmacist is a health specialist trained to exercise independent judgement when dispensing medicines and reviewing the use of medicines, in order to ensure that the medicines are safe and appropriate for the patient and that they conform to prescribers’ (generally doctors’) requirements.37 A pharmacist may advise prescribers and patients on the proper use of medicines, and provide primary health care services by educating consumers regarding health promotion and disease prevention.

1.6 Australia’s per capita consumption of certain medicines is among the highest in the developed world38 and access to pharmaceutical services, including appropriate medication management, is of key importance in achieving health outcomes. While medicines can improve quality of life and prevent disability and unnecessary hospitalisation, increasing medicines use is associated with a broad spectrum of medicine related problems.39 Medicine related problems are a direct cost to PBS and RPBS expenditure, and an indirect cost when adverse drug events are undetected or misdiagnosed, and trigger further interventions.40 It has been estimated that over 1.5 million Australians suffer an adverse event from medicines each year.41 Collectively, adverse drug events are responsible for up to 230 000 hospital admissions annually in Australia, costing approximately $1.2 billion per annum.42 In summary, effective medication management has an impact on patient safety and treatment, and the overall effectiveness of government and community spending on medicines and related services.

The pharmacy sector

1.7 The Australian pharmacy sector is highly regulated. State and Territory legislation restricts pharmacy ownership to registered pharmacists, and requires pharmacies to be licensed to operate. At the national level, the Australian Government’s Pharmacy Location Rules43 regulate the location of retail pharmacies approved to dispense PBS subsidised medicines.44

1.8 As at March 2014, there were 28 188 registered pharmacists in Australia.45 About 63 per cent of registered pharmacists work in retail pharmacy with the majority as employees. As at 30 June 2014, there were 5457 retail pharmacies approved under Section 90 of the National Health Act to supply PBS subsidised medicines.46 Section 90 approved pharmacies comprise:

- 5305 commercially operated retail pharmacies; and

- 152 ‘not-for-profit’ Friendly Society pharmacies.47

1.9 In general usage the term ‘community pharmacy’ may refer to:

- a pharmacy located in the community (in contrast to a hospital); or

- a retail pharmacy approved under Section 90 of the National Health Act to supply pharmaceutical benefits48 to the public; or

- the practice of pharmacy by pharmacists who deliver health services in a community setting (in contrast to a hospital setting).

1.10 To avoid confusion, the ANAO has used the term ‘retail pharmacy’ to refer to a pharmacy approved under Section 90 of the National Health Act to supply PBS medicines to the public.

Pharmacy bodies and associations

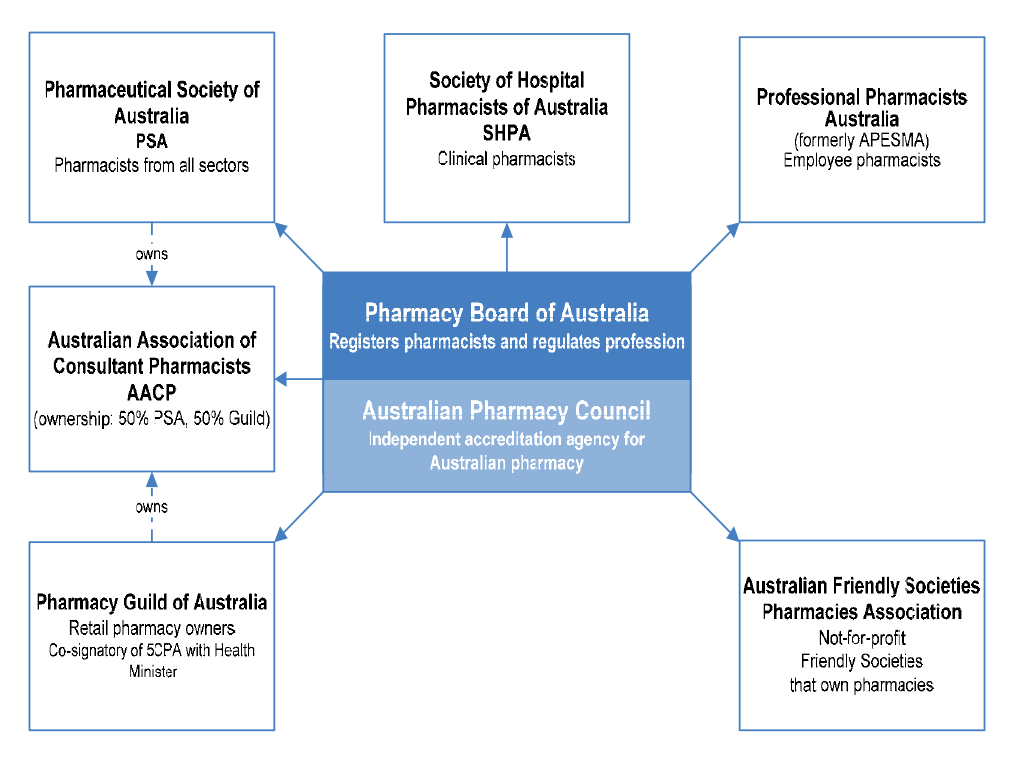

1.11 The Pharmacy Board of Australia is the national body responsible for registering pharmacists and regulating the pharmacy profession. The Board produces professional codes and guidelines that are mandatory.49 Under assignment from the Board, the Australian Pharmacy Council (APC) is responsible for accrediting pharmacy schools and programs; conducting examinations; and assessing overseas trained pharmacists and international students.

1.12 The professional associations representing the Australian pharmacy profession are shown in Figure 1.1. The largest professional association is the Pharmaceutical Society of Australia (PSA), with over 18 000 members. The Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia (SHPA) has the largest number of members practising in hospitals and other health service facilities. The PSA and SHPA have respectively developed extensive professional practice standards, but they are not mandatory.50 Professional Pharmacists Australia represents pharmacists who work as employees of pharmacies. The SHPA and the Australian Association of Consultant Pharmacy (AACP) train and accredit registered pharmacists to perform patient medication reviews.

1.13 The Pharmacy Guild, which signed the 5CPA with the Australian Government, represents the owners of retail pharmacies.51 The Australian Friendly Societies Pharmacies Association (AFSPA) represents not-for-profit pharmacies owned and operated by Friendly Societies.

Figure 1.1: Professional pharmacy bodies and associations

Source: ANAO analysis.

The Fifth Community Pharmacy Agreement (5CPA)

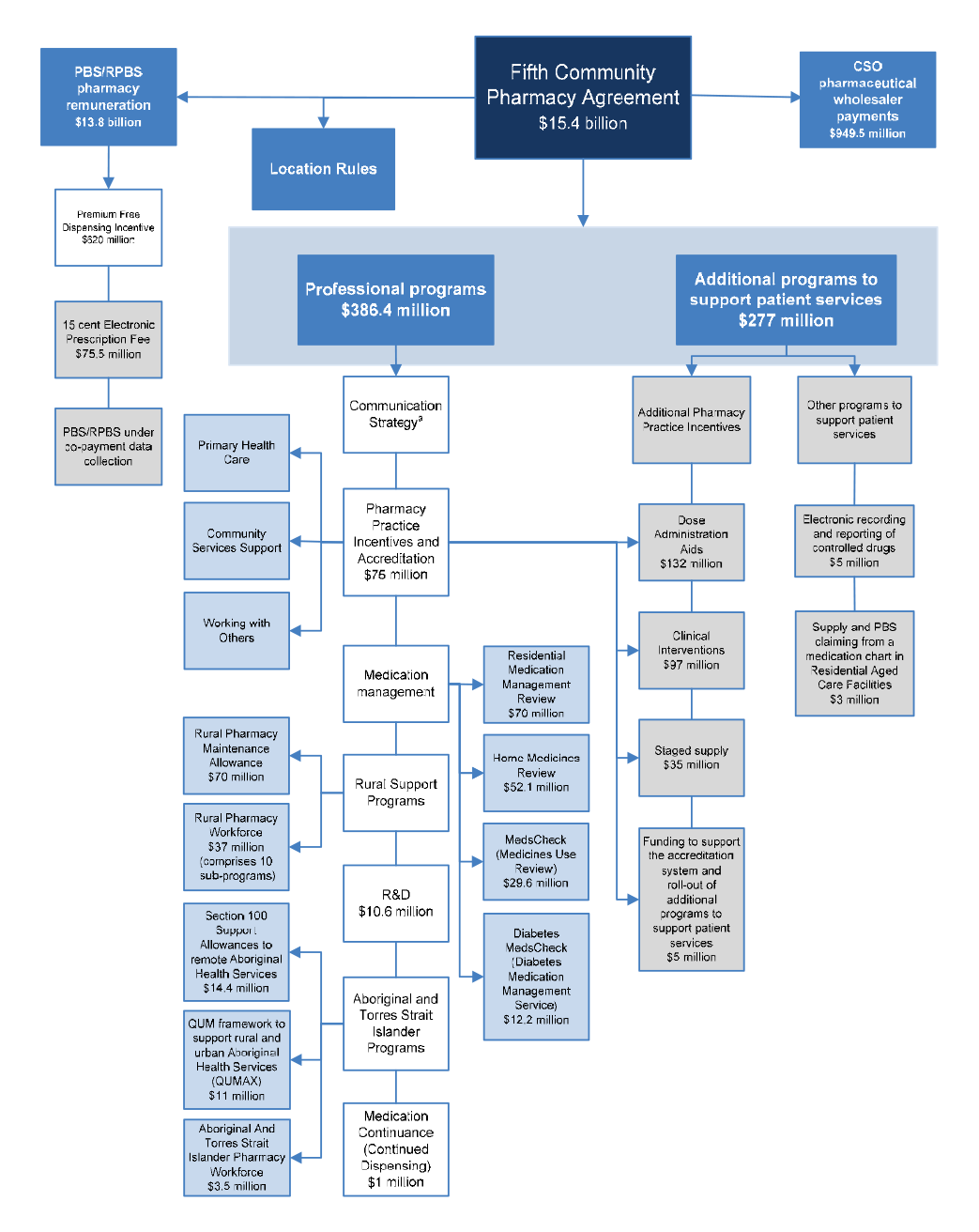

1.14 The Fifth Community Pharmacy Agreement (5CPA), which runs from 1 July 2010 to 30 June 201552, is a complex multi-part agreement. Its structure is outlined in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2: Structure of the 5CPA

Source: ANAO analysis of the 5CPA.

1.15 In summary, the 5CPA provides that the Australian Government will deliver $15.4 billion in funding over five years, as follows:

- $13 771.6 million in pharmacy remuneration (excluding the cost of medicines);

- $949.5 million to be shared among eligible pharmaceutical wholesalers that qualify for the CSO Funding Pool; and

- $663.4 million for professional programs.

1.16 Figure 1.3 reproduces the terms of the 5CPA relating to funding.

Figure 1.3: Commonwealth funding under the 5CPA

The Commonwealth will deliver $15.4 billion under the Agreement as set out in the following table:

Table: Funding for elements of the Agreement

|

Element |

$m |

|

Pharmacy remuneration (includes dispensing fee, pharmacy and wholesale mark-up, extemporaneously prepared and dangerous drug fees, premium free dispensing incentive and electronic prescription fee) |

13,771.6 |

|

Programs and services |

386.4 |

|

Additional Programs to support patient services |

277.0 |

|

Community Service Obligation |

949.5 |

|

Total |

15,384.5 |

Source: The Fifth Community Pharmacy Agreement, pp. 2–3.

1.17 The 5CPA was developed and negotiated by the then Department of Health and Ageing (now the Department of Health), and agreed by government. The Minister for Health and the Pharmacy Guild are signatories to the agreement, which was executed on 3 May 2010. The 5CPA’s six ‘principles and objectives’ are shown in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: Principles and objectives of the 5CPA

|

i |

Ensure a fair Commonwealth price is paid to Approved Pharmacists for providing pharmaceutical benefits while maximising the value to taxpayers by encouraging an effective and efficient community pharmacy network. |

|

ii |

Ensure that the Programs are patient-focused and target areas of need in the community including continued improvement in community pharmacy services provided to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. |

|

iii |

Ensure transparency and accountability in the expenditure of the Funds. |

|

iv |

Promote the sustainability and efficiency of the PBS within the broader context of health reform and ensuring that community resources continue to be appropriately directed across the health system, while also supporting the sustainability and viability of an effective community pharmacy sector. |

|

v |

Maintain a co-operative relationship between the Commonwealth and the Guild. |

|

vi |

Ensure the Location Rules work for the benefit of the Australian community including increased access to community pharmacies for the population of rural and remote areas. The specific objectives of the Location Rules are to ensure:

|

Source: Fifth Community Pharmacy Agreement, Section 1.2(d).

Key elements of the 5CPA

Pharmacy remuneration ($13.8 billion)

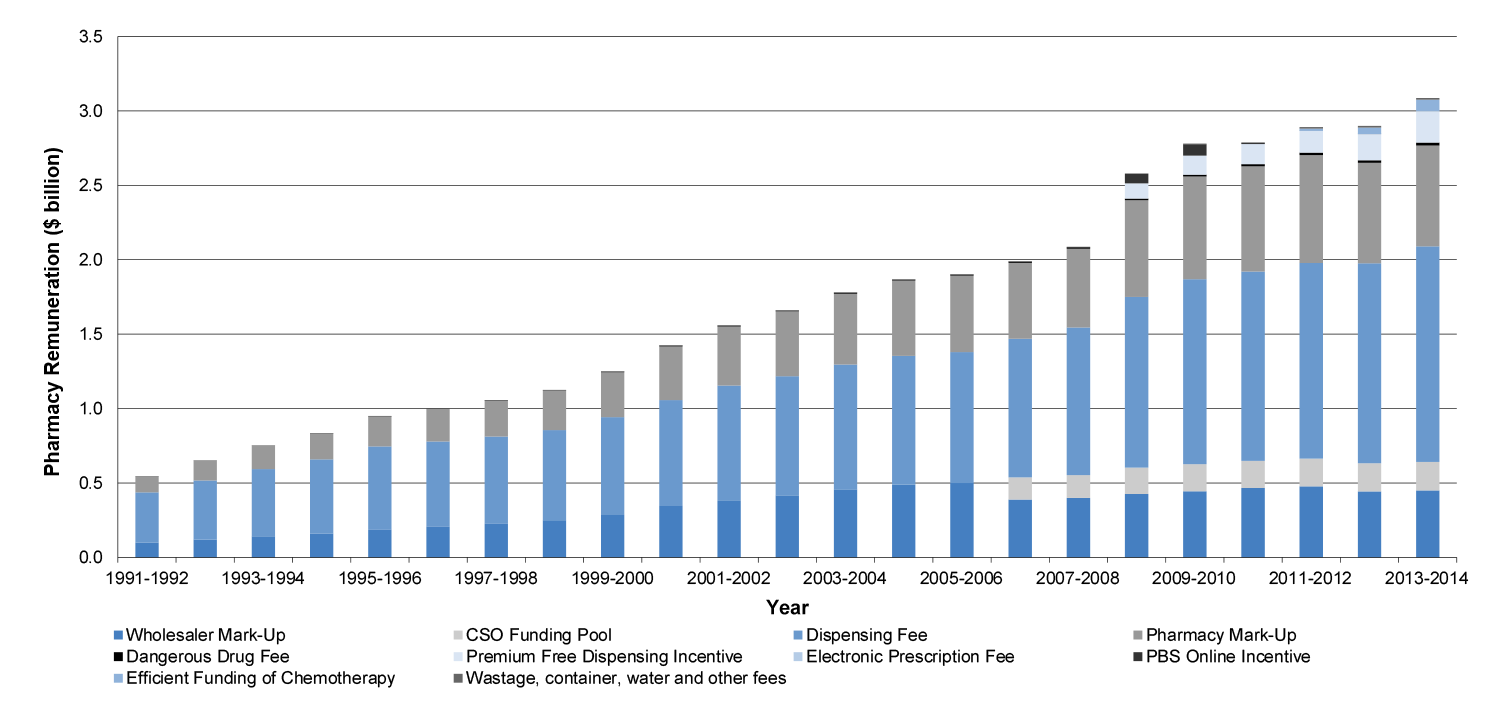

1.18 The 5CPA sets out the remuneration arrangements for ‘approved pharmacists’—the owners of retail pharmacies approved to dispense PBS subsidised medicines. Pharmacy remuneration is the largest financial component of the 5CPA, at a cost of some $11.6 billion to government and $2.2 billion to patients.53 As indicated in Figure 1.3, the 5CPA lists the components of ‘pharmacy remuneration’ as the: wholesale mark-up, pharmacy mark-up, dispensing fee, extemporaneously prepared fee, dangerous drug fee, Premium Free Dispensing Incentive (PFDI) and Electronic Prescription Fee (EPF).54 Further detail on these components is provided in Table 1.3.55

Table 1.3: Components of 5CPA pharmacy remuneration

|

Component as at 1 August 2014 |

Description |

|

Wholesale mark-up: 7.52 per cent capped at $69.94 |

A mark-up added to the ex-manufacturer price for the medicine.a |

|

Pharmacy mark-up: 15 to 4 per cent stepped mark-up bands capped at $70.00 |

A mark-up added to the wholesale price of the medicine.a |

|

Ready Prepared (RP) dispensing fee: $6.76 |

A flat fee paid for dispensing a ready prepared (‘off-the-shelf’) medicine. |

|

Extemporaneously Prepared (EP) dispensing fee: $8.80 |

A flat fee paid for dispensing an extemporaneously prepared medicine (requires ‘compounding’ or some preparation by the pharmacist). |

|

Dangerous drug fee: $2.71 |

A flat fee paid for dispensing a dangerous drug—classified as a ‘controlled drug’ due to its high potential for abuse and addiction. |

|

Premium Free Dispensing Incentive (PFDI): $1.68 |

A flat fee paid for dispensing a premium free PBS medicine that costs the patient no more than the patient co-payment. |

|

Electronic Prescription Fee (EPF): $0.15 |

A flat fee paid for dispensing a PBS/RPBS prescription that is downloaded from an electronic Prescription Exchange Service (PES)—paid on both over co-payment and under co-payment prescriptions. |

Source: ANAO analysis.

Notes:

- The wholesale mark-up and pharmacy mark-up are paid per dispensed maximum quantity for the item as specified in the PBS Schedule.

- This table outlines the pricing structure for Section 85 (National Health Act) General Pharmaceutical Benefits. Different pricing arrangements apply to pharmaceutical benefits supplied under Section 100 (National Health Act) special arrangements, which are outlined in Table 1.4.

PBS dispensing

1.19 In order for a patient to receive a medicine subsidised under the PBS, an authorised prescriber56 must prescribe a medicine that is listed on the PBS Schedule.57, 58 The patient (or their agent) presents the PBS prescription at an approved supplier (usually a retail pharmacy), which dispenses the item and charges the patient any applicable co-payment.59 The patient co-payment reduces the amount the government reimburses the pharmacy.

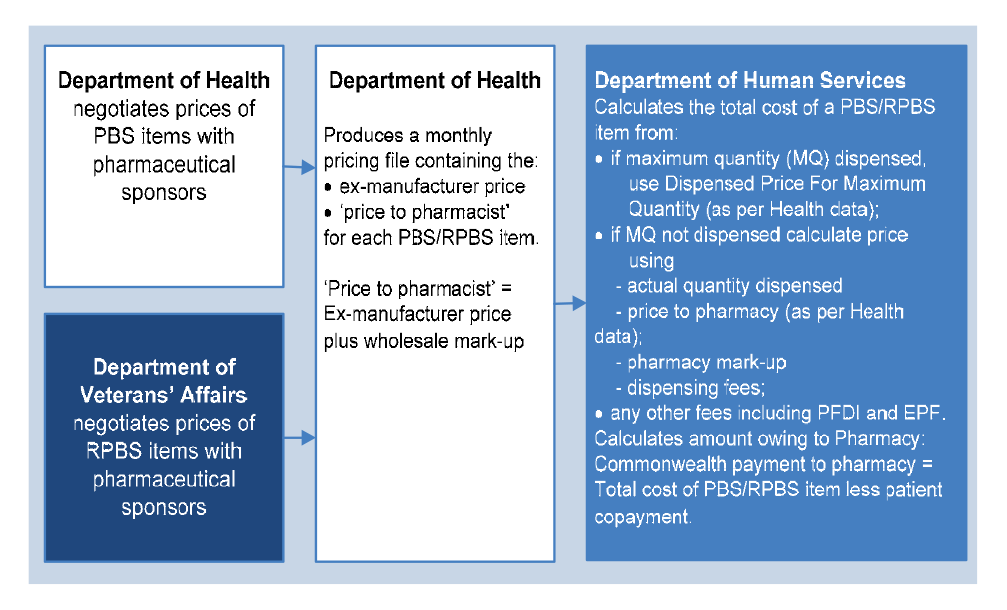

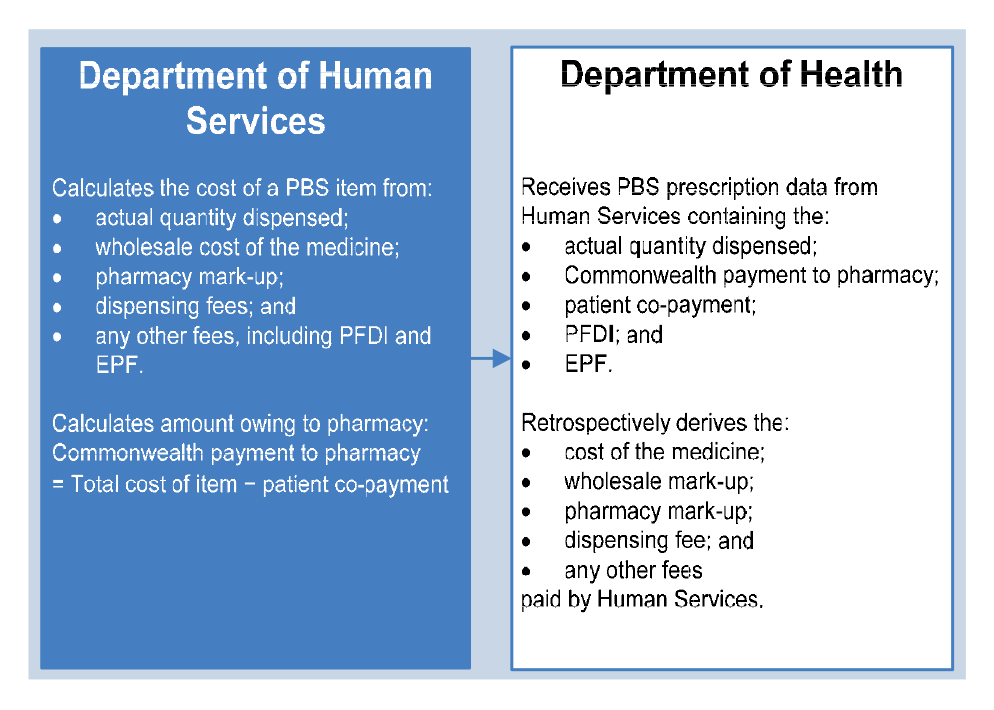

1.20 Retail pharmacies claim reimbursement for dispensing PBS items from the Department of Human Services (Human Services). Human Services calculates the dispensed price of the medicine, and then deducts any patient co-payment in order to work out the amount owing by the Commonwealth to the pharmacy.60 Different pricing rules apply to different classes of PBS items.

The PBS Schedule

1.21 The PBS Schedule lists over 902 drugs61, available in more than 2335 forms and strengths, and marketed as 5420 differently branded items.62 For pharmacy remuneration purposes, PBS medicines that are dispensed by retail pharmacies may be classified into five main groups, each with different pricing rules, as shown in Table 1.4. The RPBS Schedule is a supplementary list of items (including bandages and dressings) that are available to eligible veterans and their dependents. The RPBS generally adopts PBS pricing arrangements.

1.22 Under the 5CPA, retail pharmacies may also charge additional fees for PBS items that are priced under the patient co-payment. An example of how a common PBS item is priced is included in Appendix 2.

1.23 Table 1.4 summarises the main classes of PBS items dispensed by retail pharmacies. References are to the relevant sections of the National Health Act.

Table 1.4: Main classes of PBS items dispensed by retail pharmacies

|

PBS schedule |

Contains |

|

Section 85 items – general pharmaceutical benefits |

|

|

Section 85 (General schedule) |

The largest group of PBS drugs and the most frequently prescribed. |

|

Prescriber Bag |

About 26 Section 85 drugs provided free of charge to prescribers for emergency use. |

|

Section 100 items – items available under special arrangements |

|

|

Section 100 (Highly Specialised Drugs) |

Drugs for treating chronic conditions, which can only be initiated by a medical specialist. |

|

Section 100 (Efficient Funding of Chemotherapy) |

About 36 drugs for treating cancer, which are administered by infusion or injection. |

|

Section 100 (Remote Aboriginal Health Services) |

Section 85 drugs supplied in bulk to remote area Aboriginal Health Service clinics. |

Source: ANAO analysis.

Note: The Health Minister must declare all PBS items under Section 85 of the National Health Act. However, under Section 100, the Minister may make special arrangements for, or in relation to, providing that an adequate supply of pharmaceutical benefits will be available to persons in defined circumstances. In practice, different pricing arrangements have been implemented for certain groups of drugs supplied under Section 100 arrangements.

Pharmacy Location Rules

1.24 Subject to State and Territory law, any registered pharmacist may open a retail pharmacy. However, if a pharmacy owner wishes to claim reimbursement for dispensing pharmaceutical benefits, the pharmacy owner must first seek Commonwealth approval to supply pharmaceutical benefits from specific premises.63 If successful, the pharmacy owner is granted an approval number, which applies exclusively to those premises. If a pharmacy owner wishes to operate more than one approved pharmacy, they must separately apply for approval for each additional premises.64

1.25 The Location Rules were introduced in the first community pharmacy agreement to address perceived inefficiencies in the retail pharmacy sector and the oversupply and viability of pharmacy services in particular geographic areas.65 The first agreement provided incentive payments for pharmacies to close or merge, and the number of approved pharmacies decreased from around 5600 in 1990 to 4793 in 2003.66 The number of approved pharmacies has since increased to 5457 as at June 2014.67

1.26 The Location Rules set out location based criteria that must be met in order for the Australian Community Pharmacy Authority (ACPA) to recommend approval of a new pharmacy or the relocation of an existing pharmacy.68 Health and ACPA administer the Location Rules, and Human Services administers the pharmacy approvals system on behalf of Health.69

1.27 The Location Rules were considered in 2014 by the National Commission of Audit70 and the National Competition Policy Review.71

CSO Funding Pool ($949.5 million)

1.28 The CSO Funding Pool provides subsidies to eligible pharmaceutical wholesalers that meet the CSO service standards for supplying PBS items to retail pharmacies. The objective of the Funding Pool is to: ‘ensure that arrangements are in place to provide all Australians with ongoing and timely access to all PBS medicines, through community pharmacies’. The Funding Pool was established on 1 July 2006 under the 4CPA, and is administered by Australian Healthcare Associates, a private contractor, on behalf of Health. To access the Funding Pool, pharmaceutical wholesalers must tender for registration and enter into a deed of agreement with Health.

1.29 The CSO service standards include: being able to supply any brand of PBS item to any retail pharmacy in Australia within 24 hours; meeting minimum sales thresholds for low volume items and sales to rural and remote retail pharmacies; and supplying any PBS item at or below the ‘approved price to pharmacist’—which is based on the price agreed between the manufacturer and the government.72

5CPA professional programs ($663.4 million)

1.30 The Australian Government funds the following categories of professional programs under the 5CPA, at a total cost of $663.4 million:

- Pharmacy Practice Incentives and Accreditation ($344 million);

- Medication Management ($163.9 million);

- Rural Support ($107 million);

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Programs ($28.9 million);

- Research and Development ($10.6 million);

- Medication Continuance73 ($1 million); and

- Other Programs to support patient services (Electronic recording of controlled drugs74 ($5 million); and Supply and PBS Claiming from a Medication Chart in Residential Aged Care Facilities ($3 million)).

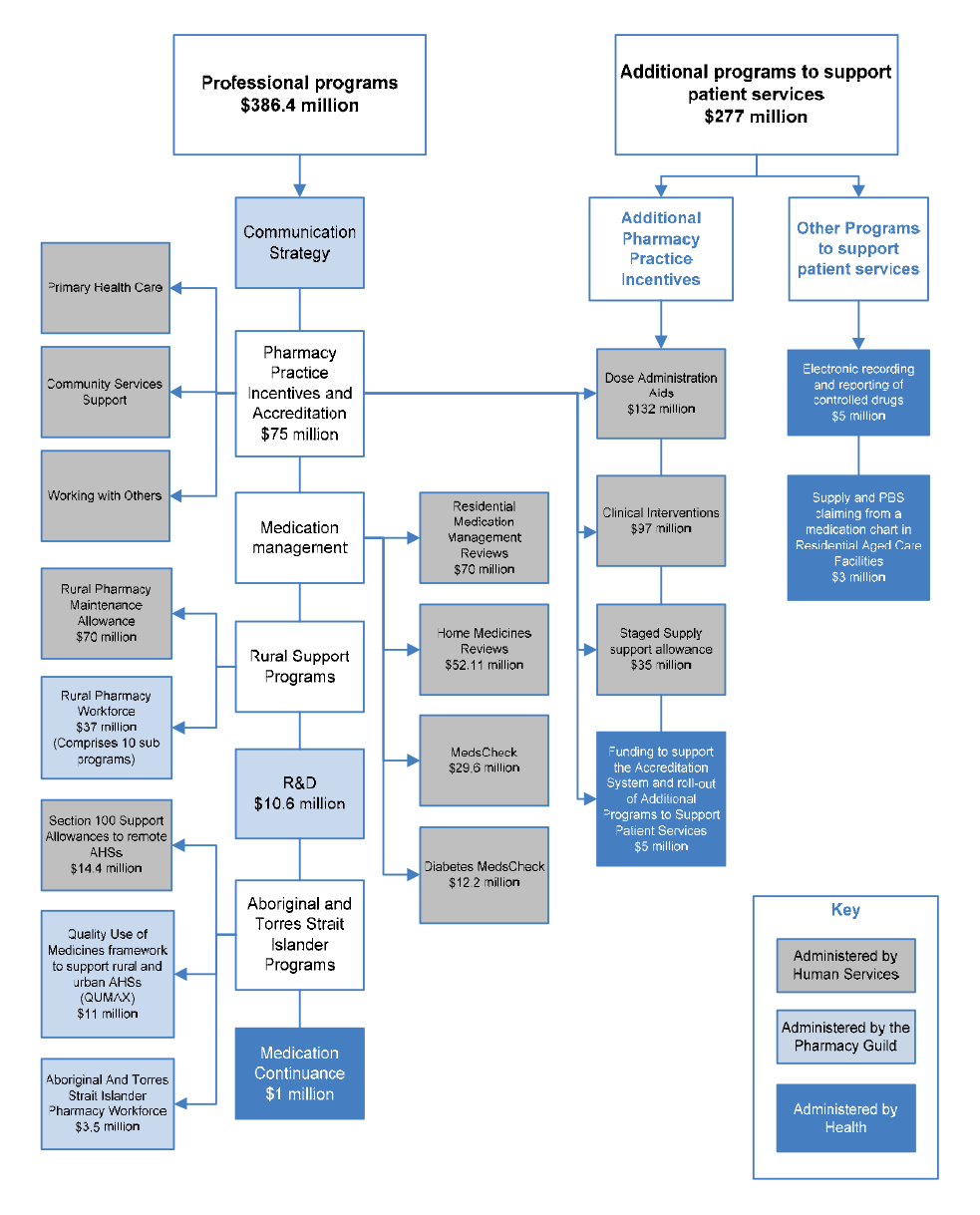

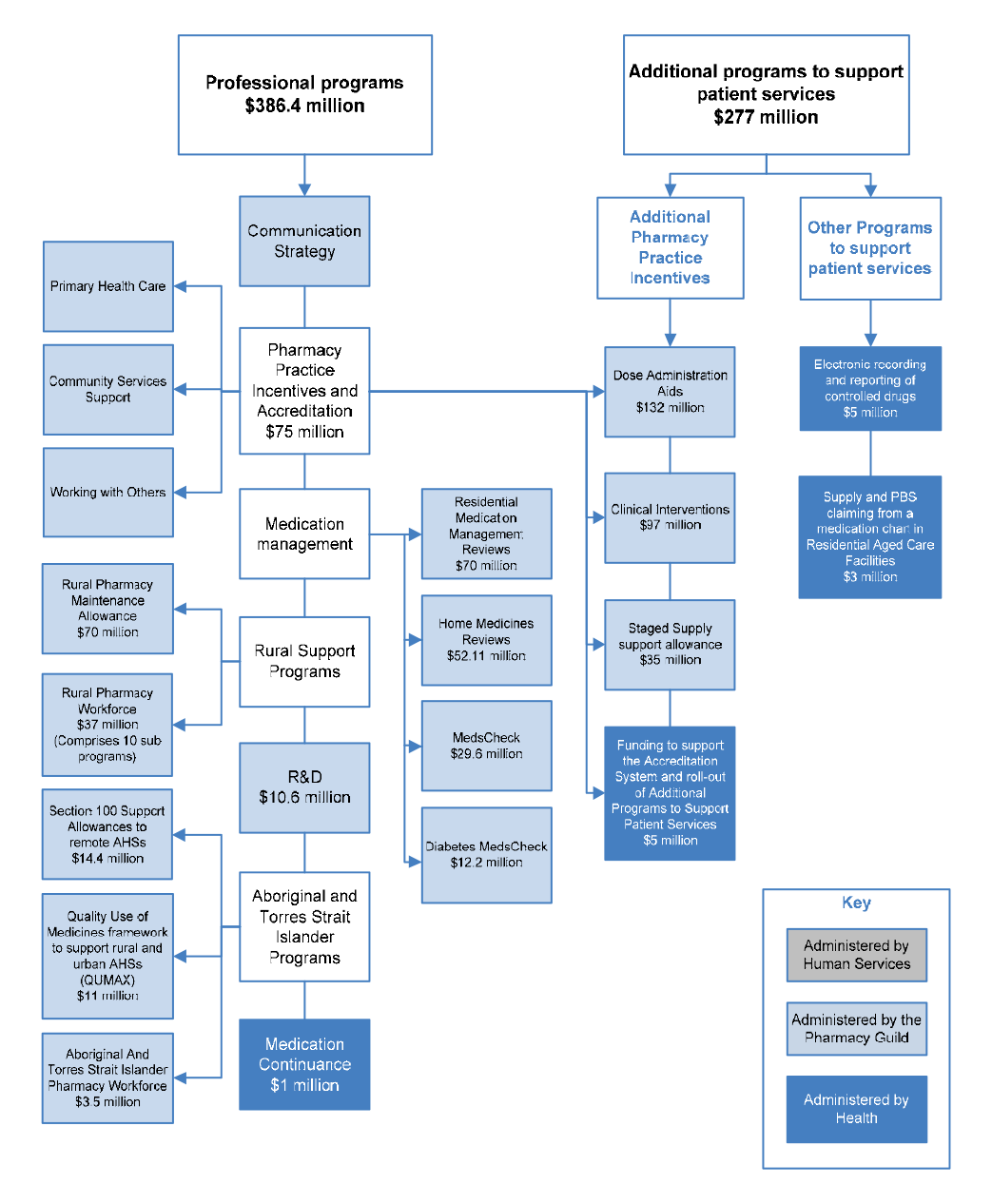

1.31 The categories listed above summarise a complex array of publicly funded professional programs and activities, which are illustrated with the other elements of the 5CPA in Figure 1.4.

Figure 1.4: Elements of the 5CPA

Source: ANAO analysis.

Notes:

- The Communication Strategy (shown above but not mentioned in the 5CPA) was funded by re-allocating $5.8 million from funding for professional programs.

- Grey boxes contain elements of pharmacy remuneration, professional programs and activities funded from new expenditure that was agreed in the 5CPA.

Legal and financial framework

Pharmacy remuneration

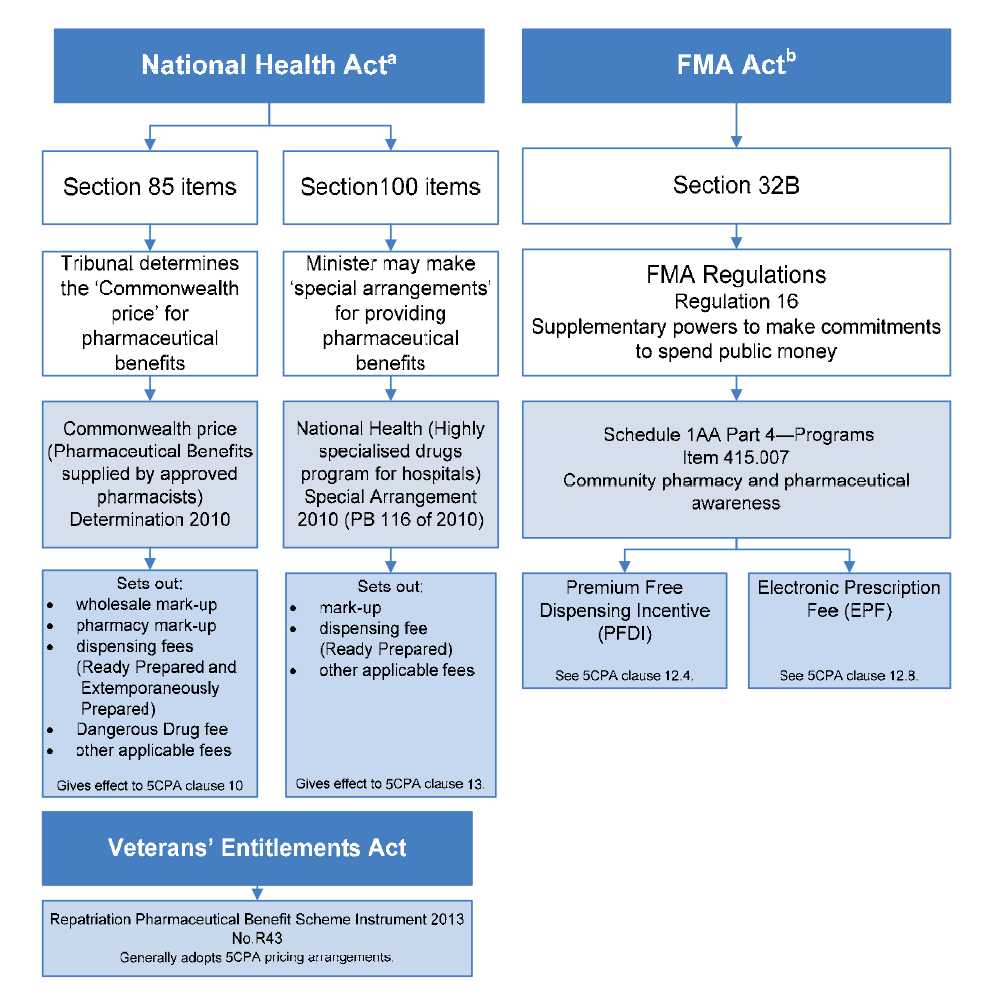

1.32 The PBS is established under Part VII of the National Health Act. As discussed, pharmacy remuneration is payable for PBS dispensing, and most of the components of pharmacy remuneration are built into the ‘Commonwealth price’ of PBS items. The Commonwealth price of PBS items is calculated by reference to determinations made by the Pharmaceutical Benefits Remuneration Tribunal (for Section 85 items), or the Minister for Health (for Section 100 and Prescriber Bag items).75 The payments for these components of pharmacy remuneration are authorised under Section 99 of the National Health Act, and made under Section 137 of the National Health Act, which establishes a special appropriation administered by Health.

1.33 In addition, the 5CPA sets out two additional fees as components of pharmacy remuneration: the Premium Free Dispensing Incentive (PFDI) and the Electronic Prescription Fee (EPF). The Commonwealth relies on provisions in the financial management legislation to authorise payment of these fees.76

1.34 Pharmacy remuneration is also payable for RPBS dispensing. The RPBS is established under Section 91 of the Veterans’ Entitlements Act 1986. The RPBS generally incorporates 5CPA pharmacy remuneration arrangements for the dispensing of items listed on the PBS and RPBS Schedules for eligible veterans and their dependents.77 RPBS pharmacy remuneration is funded through an annual appropriation administered by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA).

Pharmacy Location Rules

1.35 The Minister for Health determines the Location Rules under Section 99L of the National Health Act (the Act). Division 4B of the Act establishes the Australian Community Pharmacy Authority (ACPA), which considers applications to establish new or relocate existing approved pharmacies in accordance with the Location Rules. The ACPA consists of six members: five appointed by the Minister for Health, including two pharmacists nominated by the Pharmacy Guild and one pharmacist nominated by the Pharmaceutical Society of Australia; and one departmental representative appointed by the Secretary of the Department of Health. The ACPA recommends to the Secretary whether or not to approve a pharmacy.78

CSO Funding Pool

1.36 The Community Service Obligation (CSO) Funding Pool for pharmaceutical wholesalers was established under the 4CPA. The CSO is funded through an annual administered appropriation of the Department of Health. The CSO is an executive scheme, which is not established under legislation. Until 30 June 2014, the legislative authority for CSO payments was the reference to ‘Pharmaceuticals and pharmaceutical services’ in Part 4, Schedule 1AA of the FMA Regulations.79

Professional programs

1.37 The 5CPA professional programs are also executive schemes, which are not established by legislation. The 5CPA programs generally have program guidelines approved by Health, and many of these guidelines are available on the 5CPA website.80 Until 30 June 2014, the legislative authority for 5CPA professional program expenditure was the reference to ‘Community pharmacy and pharmaceutical awareness’ in Part 4, Schedule 1AA of the FMA Regulations.81

Agreements and contracts

1.38 The 5CPA is a complex multi-part agreement underpinned by a number of further agreements between the Department of Health and the other entities involved in its administration, including: the Department of Human Services (Human Services); the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA); the Pharmacy Guild of Australia; and Australian Healthcare Associates (AHA).82 The Pharmacy Guild and AHA are non-government entities.

Administrative arrangements

1.39 The 5CPA was developed and negotiated by Health, which has overarching responsibility for its administration, and agreed by Government. The Pharmaceutical Benefits Division within Health has responsibility for policy advice on all elements of the 5CPA, while DVA is responsible for policy advice on the RPBS, including RPBS pharmacy remuneration.

1.40 Until 1 March 2014, Human Services administered most 5CPA professional programs on behalf of Health, while the Pharmacy Guild administered Rural Support Programs, Indigenous Programs and the Research and Development Program on behalf of Health. On 1 March 2014, Health transferred responsibility for the 5CPA professional programs administered by Human Services to the Pharmacy Guild, which now administers all professional programs.83

1.41 In respect of the 5CPA, the Pharmacy Guild is variously:

- an industry association and advocate acting on behalf of retail pharmacy owners, making representations to government and public inquiries84, and conducting public campaigns85;

- a publicly funded administrator under the 5CPA, at times acting as the Department of Health’s agent;

- a recipient of Commonwealth grants86 relating to certain 5CPA professional programs87;

- an owner of business enterprises that sell products and services to pharmacies on a commercial basis—with some products and services relating to 5CPA programs and activities88; and

- an advisor to Health, through its co-membership of the overarching 5CPA governance body89 and under its contracts with the department.

1.42 Human Services processes pharmacy claims for reimbursement of PBS and RPBS dispensing on behalf of Health and DVA respectively, and accesses relevant Health and DVA appropriations for this purpose. The administration of the CSO Funding Pool is outsourced by Health to Australian Healthcare Associates (AHA), a private company based in Melbourne. AHA collects data from participating CSO pharmaceutical wholesalers and calculates their monthly share of the funding pool, with Health paying CSO wholesalers on the basis of AHA’s advice.

1.43 An outline of 5CPA funding and administrative arrangements from 1 March 2014 is presented in Table 1.5.

Table 1.5: 5CPA funding and administrative arrangements from March 2014

|

5CPA element |

Funding $m |

Policy advice |

Claims processed by |

Paid by |

|

Pharmacy remuneration total |

$13 771.6 |

|

|

|

|

PBS |

|

Health |

DHSa |

DHS |

|

RPBS |

|

DVA |

DHS |

DHS |

|

Location Rules |

|

|

|

|

|

Approval of new pharmacies and relocation of existing pharmacies |

n/a |

Health |

DHS ACPAb |

n/a |

|

Community Service Obligation (CSO) Funding Pool total |

$949.5 |

|

|

|

|

CSO funding for pharmaceutical wholesalers |

$949.5 |

Health |

Australian Healthcare Associates |

Health |

|

Programs and services total |

$386.4 |

|

|

|

|

Pharmacy Practice Incentivesc |

$75.0 |

Health |

Guild |

Guild |

|

Medication Management Programs |

$163.9 |

Health |

Guild |

Guild |

|

Rural Support Programs |

$107.0 |

Health |

Guild |

Guild |

|

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Programs |

$28.9 |

Health |

Guild |

Guild |

|

Research and Development |

$10.6 |

Health |

Guild |

Guild |

|

Medication Continuance |

$1.0 |

Health |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Additional Programs to Support Patient Services total |

$277.0 |

|

|

|

|

Additional Pharmacy Practice Incentivesc |

$269.0 |

Health |

Guild |

Guild |

|

Electronic recording of controlled drugs |

$5.0 |

Health |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Supply and PBS claiming from a medication chart in Residential Aged Care Facilities |

$3.0 |

Health |

n/a |

n/a |

Source: ANAO analysis of Health, Human Services and DVA information.

Notes:

- DHS is the Department of Human Services; DVA is the Department of Veterans’ Affairs.

- ACPA is the Australian Community Pharmacy Authority. ACPA does not process claims but reviews applications and makes recommendations.

- Pharmacy Practice Incentives and Additional Pharmacy Practice Incentives are part of the same program.

1.44 A summary of the five year budget and staffing for key entities involved in the 5CPA’s administration, before and after the transfer of 5CPA professional programs from Human Services to the Pharmacy Guild in March 2014, is shown in Table 1.6.

Table 1.6: Five year budget for 5CPA administration

|

Entity |

2010–15 budget before 1 March 2014 |

2010–15 budget after 1 March 2014 |

||

|

|

Staffing (ASL) |

Budget ($m) |

Staffing (ASL) |

Budget ($m) |

|

Healtha |

237.8 |

30.8 |

239.7 |

31.2 |

|

Human Services |

273.5 |

41.8 |

150.1 |

25.5c |

|

Veterans’ Affairs |

1.0 |

0.1 |

1.0 |

0.1 |

|

Pharmacy Guildb |

- |

29.3 |

- |

31.2 |

Source: Health, Human Services, Pharmacy Guild and Veterans’ Affairs information.

Notes: An entity’s administrative budget may cover a range of administrative costs in addition to staffing, such as ICT, property, legal and miscellaneous costs. ASL is average staffing level.

- See Table 1.7 for Health’s disaggregated annual staffing and administrative expenditure.

- The Pharmacy Guild was unable to provide ASL figures. See Table 5.2 for a detailed breakdown of administrative and program funding as specified in Health contracts with the Pharmacy Guild.

- Human Services’ ongoing budget was reduced by the equivalent of $16.4 million over five years following the transfer of 5CPA professional programs to the Pharmacy Guild. Prior to the transfer of functions, Human Services had expended $14.3 million. Health and the Pharmacy Guild received the unexpended $2.1 million portion of Human Services’ original budget.

1.45 Health’s annual expenditure and staffing for the administration of the 5CPA is shown in Table 1.7.

Table 1.7: Health’s 5CPA annual administrative expenditure and staffing

|

Year |

Before transfer of the 5CPA professional programs on 1 March 2014 |

After transfer of the 5CPA professional programs on 1 March 2014 |

||

|

|

Staffing (ASL) |

Expenditure ($m) |

Staffing (ASL) |

Expenditure ($m) |

|

2010-11 (actual) |

64.0 |

7.2 |

64.0 |

7.2 |

|

2011-12 (actual) |

49.2 |

6.5 |

49.2 |

6.5 |

|

2012-13 (actual) |

45.3 |

6.2 |

45.3 |

6.2 |

|

2013-14 (actual) |

41.5 |

5.7 |

42.1 |

6.0 |

|

2014-15 (budget—indicative) |

37.8 |

5.1 |

39.1 |

5.3 |

Source: Department of Health.

Note: Health’s 2014–15 budget is indicative as at August 2014.

Audit objective, criteria and methodology

Audit objective and scope

1.46 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the development and administration of the Fifth Community Pharmacy Agreement (5CPA), and the extent to which the 5CPA has met its objectives. The audit examined the development and negotiation of the 5CPA by the then Department of Health and Ageing (now the Department of Health), and the administration of the 5CPA by the Department of Health (Health). The audit also examined aspects of the 5CPA that were implemented by the Department of Human Services (Human Services) and the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA).

1.47 While the ANAO did not examine the Pharmacy Guild of Australia’s administration of 5CPA professional programs, the audit refers to aspects of its involvement relating to the development, negotiation and administration of the 5CPA.

1.48 The Pharmacy Location Rules are not examined in this performance audit. They were considered in 2014 by the report of the National Commission of Audit and the draft report of the National Competition Policy Review.

Criteria

1.49 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- the 5CPA provides transparent and accountable remuneration arrangements for the dispensing of Commonwealth pharmaceutical benefits, which achieve value for money, consistent with Government policy;

- the 5CPA’s funding and savings commitments are being met;

- the additional programs and services funded under the 5CPA are managed effectively and provide value for money; and

- the 5CPA performance framework enables an assessment of the extent to which the 5CPA is meeting its objectives.

Methodology

1.50 The audit methodology included:

- interviewing staff from Health, Human Services and DVA;

- extracting pharmacy claims and payment records from Health and Human Services databases;

- reviewing relevant documentation, including departmental files, briefings, legal advice, program guidelines, monitoring and reporting systems, reviews, evaluations and correspondence;

- consulting stakeholders and peak bodies, including the Pharmacy Guild; and

- reviewing over 100 stakeholder submissions received by the ANAO through its citizen’s input facility.90

1.51 Fieldwork was conducted in Health, Human Services and DVA, in Canberra, Adelaide and Melbourne. This is the first ANAO performance audit of a community pharmacy agreement.91

1.52 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of some $828,541.

Report structure

1.53 The structure of this report is outlined in Table 1.8.

Table 1.8: Structure of the audit report

|

Chapter |

Overview |

|

2. Development of the 5CPA |

Examines the development of the 5CPA, including the planning, costing and negotiation of the agreement. |

|

3. Pharmacy Remuneration |

Examines the implementation of 5CPA pharmacy remuneration arrangements; departmental reporting of pharmacy remuneration; and the actual costs of pharmacy remuneration compared to departmental estimates. |

|

4. Pharmaceutical Services |

Examines dispensing services and 5CPA professional programs and services funded by the Australian Government under the 5CPA. |

|

5. Administration of Professional Programs |

Examines the governance and administrative arrangements for the 5CPA professional programs and services, and Health’s contractual arrangements with the Pharmacy Guild. |

|

6. Reporting and Evaluation |

Examines Health’s reporting and evaluation arrangements for the 5CPA. |

2. Development of the 5CPA

This chapter examines the development of the 5CPA, including the planning, costing and negotiation of the agreement.

Introduction

2.1 The Department of Health (Health) has developed and negotiated successive community pharmacy agreements on behalf of the Australian Government. This chapter examines Health’s processes for planning, costing and negotiating the Fifth Community Pharmacy Agreement (5CPA) with the Pharmacy Guild of Australia (Pharmacy Guild), including:

- planning, with particular reference to the development of a 5CPA costing model by Health;

- the forecasting and reporting of expected 5CPA costs and savings; and

- the negotiation of the 5CPA and outcomes of negotiations.

Planning for the 5CPA

2.2 Health advised the ANAO that there was no clear start date for its planning of the 5CPA, as there was a gradual ‘ramping up’ of activity that started at least 12 months before negotiations with the Pharmacy Guild commenced in July 2009.92 Although there was no documented plan for Health’s development of the 5CPA, Health advised the ANAO that the key steps in the process were:

- background research;

- the development of a forecasting model to estimate the costs of pharmacy remuneration under different scenarios;

- engagement with the department’s senior executive;

- seeking government approval; and

- negotiations with the Pharmacy Guild.

2.3 Health further advised the ANAO that the department engaged more widely beyond the department’s senior executive, including across the department, through an inter-departmental committee, and other stakeholder groups beyond the Pharmacy Guild.93

Background research and analysis

2.4 Health indicated that the 5CPA planning process involved consideration of evaluations of the components of the 4CPA. One evaluation was completed before the 5CPA was signed, and eleven were completed afterwards.94 To fully inform the development of the agreement, the evaluations should desirably have been completed before the agreement was finalised. In this respect, Health advised the ANAO that:

Evaluations and/or reviews undertaken during 4CPA, including those that did not commence until 2010, were still used to inform the construct of 5CPA programs (i.e., how continuing programs may have been implemented). In several instances, the Department used draft reports (if they existed) as a part of the negotiations.

2.5 In October 2008, Health convened a Departmental Workshop Group that canvassed a range of strategic and policy issues related to the development of the 5CPA. In November 2008, Health also convened a Remuneration Working Group to conduct background research for the development of the 5CPA. Following research and analysis of pharmacy’s role in the health care system, Health concluded that the current system of remunerating pharmacies based on the price and volume of medicines that they dispense had significant drawbacks. Health advised the ANAO that:

The results of the Department’s research and analysis were presented and discussed at an Inter-Departmental Committee (IDC) consisting of officers from the Departments of Finance and Deregulation, the Treasury, the Prime Minister and Cabinet and Industry, Tourism and Resources. Following the Department’s research and analysis and the consideration of the IDC, it was concluded that the current system of remunerating pharmacies based on the price and volume of medicines that they dispensed had drawbacks consistent with any fee-for-service or retail model, namely:

- the cost of pharmacy remuneration was driven by factors unrelated to health outcomes for patients, or services provided to patients; and

- retail pharmacies had limited incentive to improve the quality use of medicines, or other professional services to consumers.

2.6 Health did not keep a record of the meetings of the inter-departmental committee that considered these issues in the lead up to the negotiation of the 5CPA.

2.7 Pharmacy remuneration is structured around the price of individual medicines through a complex system of mark-ups and fees95, which do not necessarily relate to the level of professional service required by different patients with different medication regimens. Health’s records indicate that, at the time, the department considered the negotiation of the 5CPA to be an opportunity to improve health outcomes through better utilisation of the professional skills of pharmacists. Health considered that these outcomes could be achieved by restructuring pharmacy remuneration to shift the financial incentives from the volume driven sale of medicines, to the delivery of professional services.

Development of the 5CPA costing model

Limitations of previous costing model

2.8 A key departmental objective in the lead up to the negotiation of the 5CPA was the development of a pharmacy remuneration costing model. Health had experienced difficulties in negotiating the 4CPA partly due to a lack of technical capability.96 According to a departmental report:

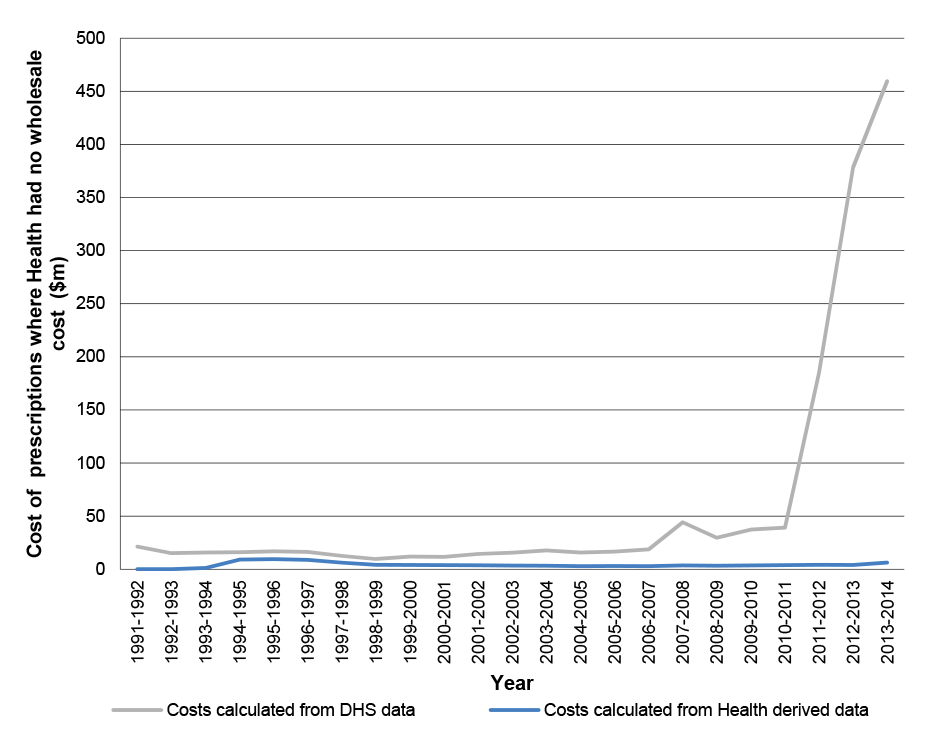

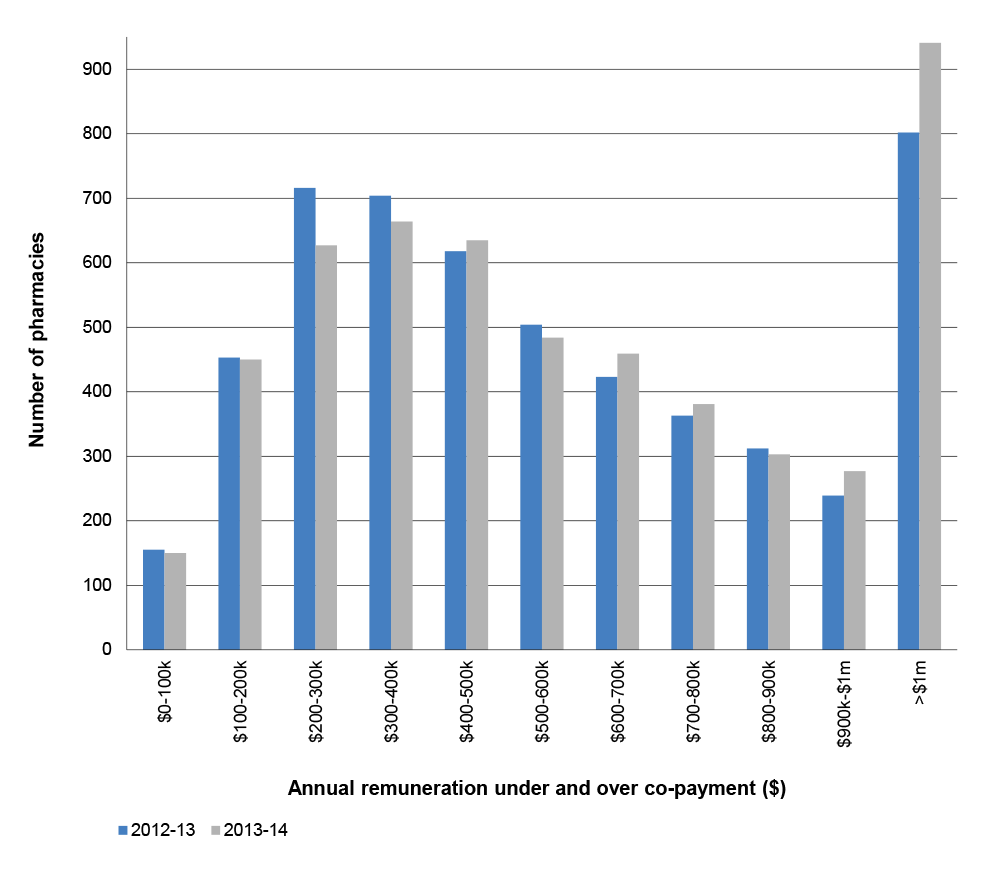

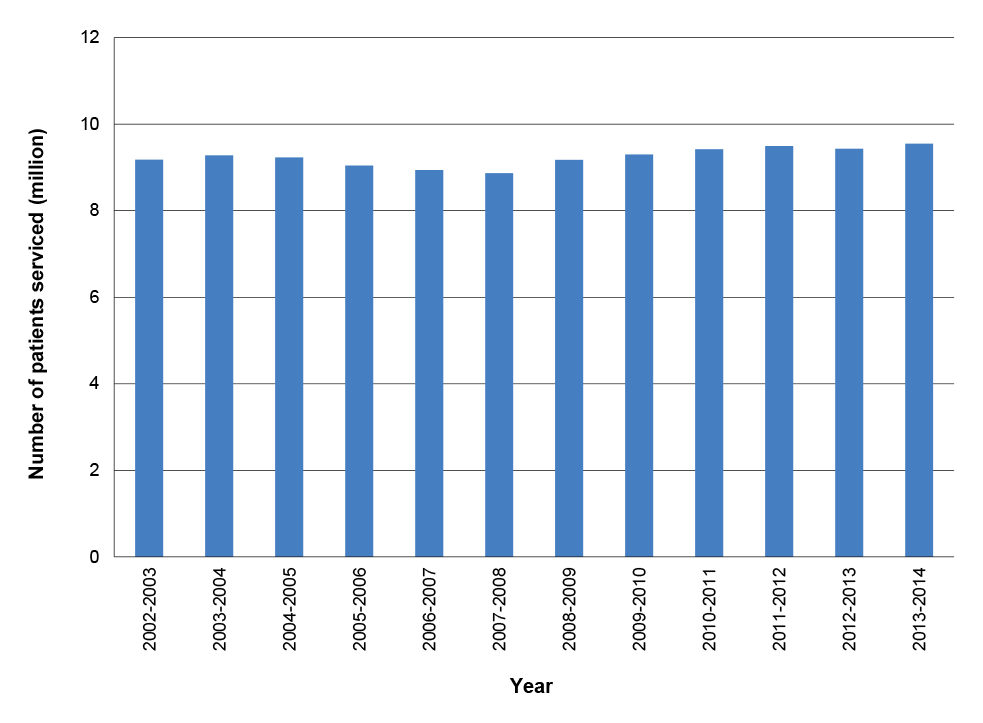

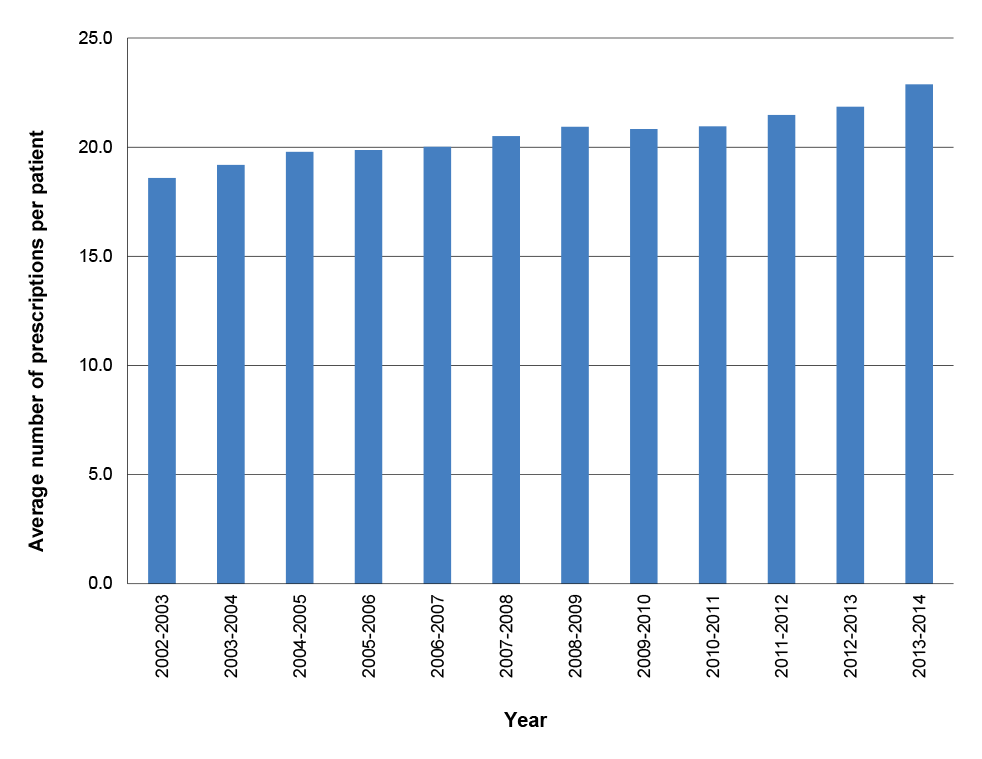

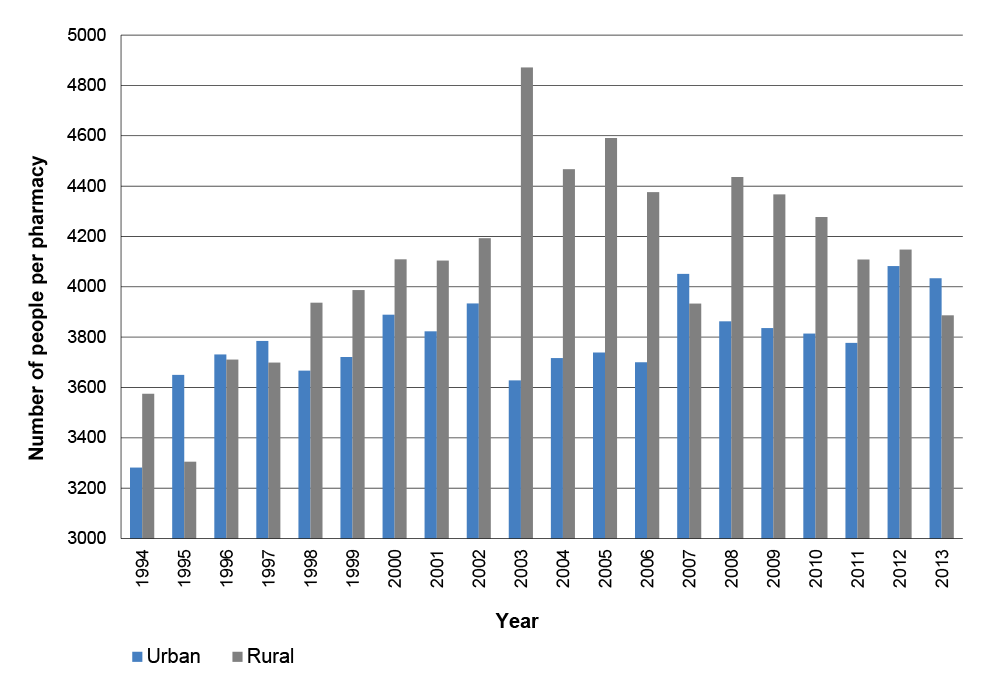

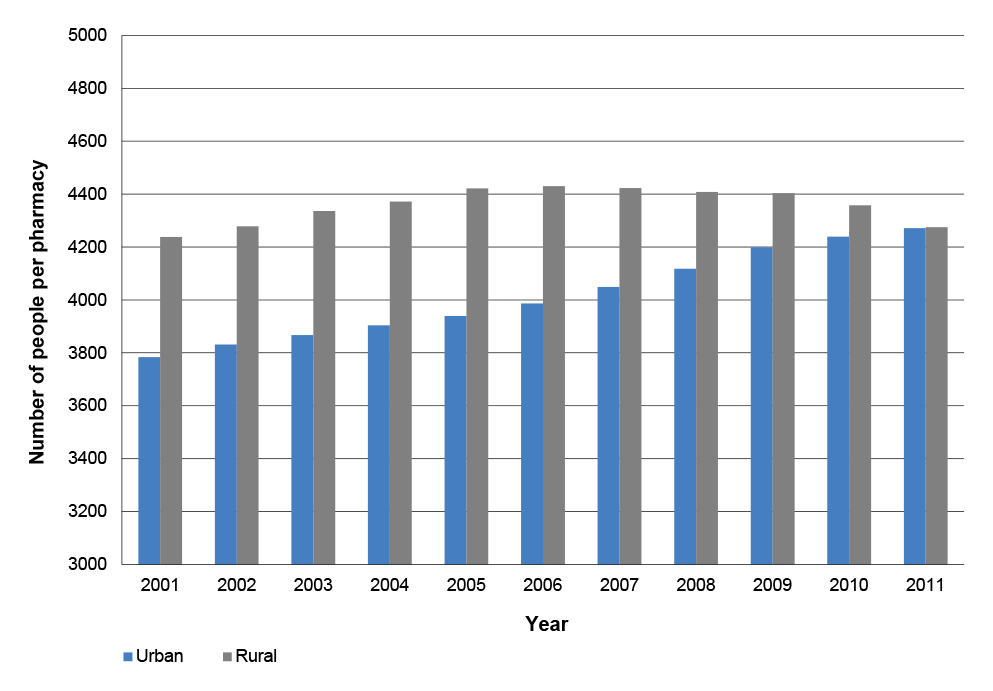

Unfortunately, the Department had to rely on an Excel spreadsheet to forecast the costs to government of the various remuneration scenarios put forward during the negotiations of the Fourth Agreement. The Excel spreadsheet could only provide linear forecasting, relied on manual manipulation of data (therefore subject to human error), was dependent on availability of Departmental staff with advanced Excel skills and struggled to manage the large amount of Medicare PBS dispensing data. The Excel spreadsheet was slow and cumbersome. The deficiencies of the Excel spreadsheet were again highlighted in the 2006–07 negotiations of the compensation package to pharmacists under the PBS reforms…