Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of the Fair Entitlements Guarantee

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Employment’s administration of the Fair Entitlements Guarantee.

Summary

Introduction

1. Businesses face a range of challenges and each year a number fail as a result, leaving their employees without employment and in some instances, without access to their accrued employee entitlements. In 2013–14, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission reported that 9 8221 companies entered external administration.2 The reasons for these failures were commonly attributed to: inadequate cash flow or high cash use; poor strategic management of the business; and trading losses3. Notwithstanding the reason for a business failing, successive Australian Governments have recognised the vulnerability of employees when this occurs. It is in this context that government has, since 2000, provided financial support to protect eligible employees from losing their accrued employee entitlements, including unused annual leave, long service leave, redundancy pay and wages, where the employee cannot get payment from another source.

2. The vulnerability of Australian employees to losing entitlements was highlighted in the late 1980’s by the Harmer Report.4 The issue came to prominence again in the late 1990’s following a number of significant corporate closures resulting in the loss of affected employee’s accrued entitlements. Following lengthy public discussion about protection of employees’ entitlements and consideration of a number of options,5 the Employee Entitlements Support Scheme (EESS) was established in early 2000. As a safety-net scheme, the EESS aimed to provide some assistance to employees, but not necessarily to compensate them for all their unpaid entitlements.

3. In early 2001, the original scheme was replaced with the General Employee Entitlements and Redundancy Scheme (GEERS). This scheme had fewer limits on the assistance available and as result, higher payments were generally provided to affected employees.6 The GEERS scheme was subsequently replaced by the Fair Entitlements Guarantee (FEG), which came into effect in December 2012 with the passing of the Fair Entitlements Guarantee Act 2012 (the FEG Act). Whereas previous schemes were delivered through administrative arrangements, this legislation established for the first time a legal obligation for government to provide support to eligible employees. The explanatory memorandum for the legislation described the need for the scheme in the following terms:

A scheme such as the one created by the Bill is necessary to fulfil a significant community need to protect the entitlements of Australian employees who would otherwise stand to lose their entitlements if they lose their jobs due to insolvency of their employer. While alternative measures for protecting employee entitlements are available on a limited scale (for example, redundancy trust funds in the construction industry) these are insufficient to adequately protect employees.7

4. The scheme is administered by the Department of Employment.8 To access FEG assistance, affected employees who have lost their employment due to insolvency and have not been paid their entitlements, must submit a claim for support under the scheme—this process is not initiated automatically when the insolvency occurs. During 2013–14, the department received 16 2469 claims for assistance. Of these claims, 11 255 were assessed as eligible and the department distributed $197 million to these claimants. To be determined as eligible for support, the employee’s former employer must have experienced an ‘insolvency event’.10 The department relies on the insolvency practitioner appointed to manage the affairs of the employer to verify the details of the claim and to assess the amount payable to the employee in the form of an advance11. The department will generally distribute the advance to the insolvency practitioner who makes necessary deductions (for example, tax deductions and superannuation payments) and distributes the net payment to the employee. The department then seeks to recover the amount advanced from the former employer on behalf of the Commonwealth as part of the winding up process of the employer’s business.

5. The role of the insolvency practitioner in an insolvency event is to realise the assets of the employer’s business and to recover sufficient funds to distribute these to creditors. These funds must be paid in the order of priorities set out in the Corporations Act 2001. In Australia, employee entitlements are ranked behind secured creditors and the costs and expenses incurred by the insolvency practitioner in winding up the business, but are given priority over the majority of other unsecured creditors.12 Once an advance has been paid, the FEG Act provides the Commonwealth with the same rights as a creditor of the company and the same right of priority of payment in the winding up of the company as the person who received the advance would have had.

6. Over the 14 years of the various schemes’ existence, government has distributed nearly $1.5 billion to affected employees. Of this amount, $1.1 billion was distributed in the last seven years of the schemes’ operation, representing a three-fold increase on the $379 million distributed over the first seven years of operation. A key factor in the growth in demand for support over the last seven years has been the impact of the global economic crisis, which in 2008–09 saw an increase of 60 per cent in the number of claims received.

Audit approach

Audit objective and criteria

7. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Employment’s administration of the Fair Entitlements Guarantee (FEG).

8. To conclude against the audit objective, the ANAO’s high-level criteria considered whether: operational elements of the scheme were well managed; the treatment of claimants was fair and equitable; and performance of the scheme was effectively measured, monitored and reported.

Overall conclusion

9. Employees may receive little notice or forewarning when their employer’s business becomes insolvent or bankrupt and are generally not well placed to manage the risks associated with this occurring. As a result, the personal and social costs of business failure can fall heavily on employees and it is for this reason the Australian Government provides, through its employee entitlements scheme, a level of protection to employees when their employer’s business fails. While the Government’s entitlements scheme may not cover all of the entitlements an employee has accrued, it provides employees with a safety-net that can cushion the impact of the loss of employment and help bridge the transition to new employment. In 2013–14, the Fair Entitlements Guarantee (FEG) provided support to 11 255 employees from 1 536 insolvent entities, approximately 16 per cent of the 9 82213 companies reported by the Australian Security and Investments Commission as entering external administration during this same period. Through FEG and its predecessor schemes the Australian Government has distributed nearly $1.5 billion in advances since January 2000. Of these advances, the Commonwealth has recovered less than $200 million (13 per cent).

10. Overall, the department’s administration of the scheme has been mixed; while the department effectively transitioned its delivery of the previous entitlements scheme, the General Employee Entitlements and Redundancy Scheme (GEERS), to operate in accordance with the new FEG legislation in early 2013, a subsequent change initiated in August 2013—aimed at aligning the claims assessment process with the new arrangements—was poorly managed resulting in a significant backlog of claims and lengthy delays for claimants in obtaining their FEG payment. The department has taken action to reduce this backlog and advised that this work will continue to be a priority in 2015, however there are also opportunities for the department to make improvements to internal procedures to provide confidence that key compliance risks are being effectively managed. In particular, improvements to fraud control arrangements would address existing weaknesses and there is an opportunity to give greater focus to fraud prevention and detection. There would also be benefit in the department giving greater attention to periodic analysis and evaluation of the scheme’s performance and how the scheme integrates with other government initiatives aimed at protecting employees and regulating business.14 This work would support advice provided to government on relevant policy issues and improve external reporting.

11. Work associated with the transition of GEERS to FEG largely occurred over 2012–13, extending into 2013–14 as the flow of FEG claims gradually increased. During this time, the department also embarked on a change to its operating model, including in August 2013 the introduction of a new process for assessing FEG claims. In preparing for this change the department gave insufficient focus to the risks to its successful implementation, the potential consequences of these risks and the development of strategies for their management. In particular, there were limitations with the claims processing system which lacked the functionality to manage, track and report the status of individual claims and to provide visibility of the claim workflow to identify processing bottlenecks. These limitations hampered the department’s ability to identify and effectively respond to issues that arose during implementation of the change. This, in turn, lead to a backlog of claims.

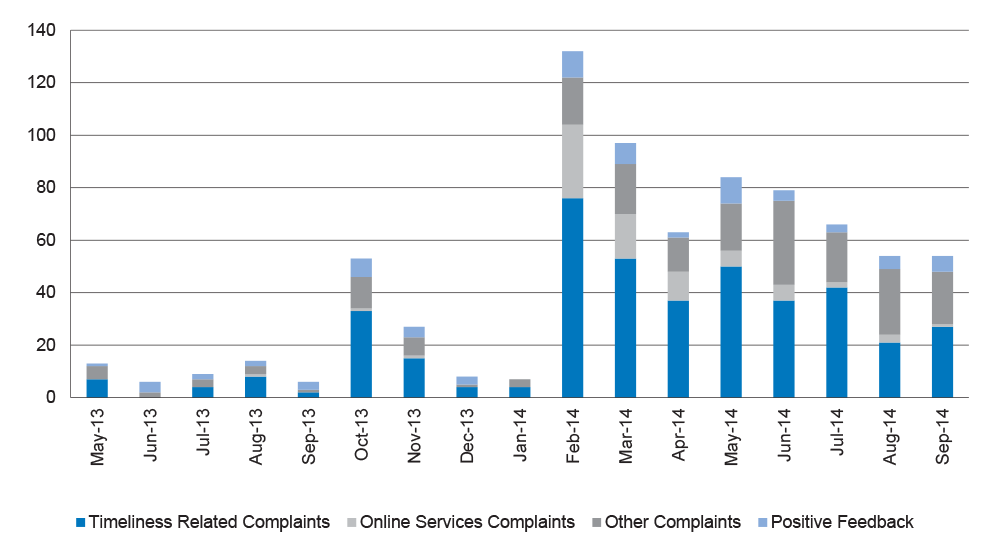

12. As a consequence, by the end of 2013–14, the average time for claimants to receive their FEG payment had doubled and the backlog of claims increased by 63 per cent to reach 8 297. The age profile of claims also deteriorated during this period, with the proportion of claims older than 16 weeks increasing more than 400 per cent to reach 4 467 in June 2014.15 Demonstrating the level of claimant frustration with these delays, 54 per cent of complaints received by the department between May 201316 and September 2014 related to timeliness issues.17 Better planning, including early identification of risks, would have allowed these to be managed and mitigated, and better positioned the department to undertake this change.

13. Monitoring compliance with the FEG legislation and the conditions of the scheme is a key element of the department’s administration of FEG. A sound approach to fraud control is an important component of the compliance monitoring framework and is fundamental to programs such as FEG that rely on third parties to verify information and distribute payments. Notwithstanding the associated risks which include frequently unavailable or poor quality documentation, and single payments to an individual approaching $300 000,18 the department’s fraud risk rating for the scheme is assessed as low. This assessment reflects weaknesses with the scheme’s fraud risk assessment process and the processes for identifying, tracking and reporting instances of non-compliance and fraud.

14. Furthermore, the department’s fraud control framework adopts an approach that emphasises the investigation of fraud after it has occurred, with lesser focus given to prevention and detection. As part of this framework, responsibility for the fraud prevention and detection is largely devolved to program staff and managers with only basic levels of fraud training and with limited active support from fraud specialists to assist them fulfil these responsibilities.19 To provide confidence that fraud risk is being adequately and appropriately managed, the department should improve its fraud control framework through adoption of a more contemporary risk-based approach that places greater focus on the areas of fraud prevention and detection.20

15. The ANAO has made one recommendation. Observing that the department is taking action to the resolve the backlog of existing claims, the recommendation is aimed at addressing identified issues associated with the FEG fraud controls and strengthening the department’s management of fraud risk by increasing its focus on fraud prevention and detection.

Key findings by chapter

Managing Scheme Risks (Chapter 2)

16. Facilitating timely access to entitlements by claimants was a significant risk to be managed by the department as part of the transition to FEG and as part of subsequent changes the department made to the FEG operating model. In August 2013, seeking to better align internal processes with the expectations of a legislative scheme (including changes to reflect the legislation’s focus on individual claims, rather than on the business), the department implemented a stage-based approach to processing claims. Notwithstanding the significance of this change and its potential to have an impact on the timely processing of claims, the department did not, prior to proceeding, seek to identify, assess and manage risks to its successful implementation. The department proceeded with the change despite having only limited documentation defining roles and responsibilities and describing the new processing activities and despite the processing systems not having the functionality necessary to manage, track and report the status of individual claims and to provide visibility of the claims workflow to identify processing bottlenecks. As a consequence, a large backlog of claims resulted and it has taken longer for claimants to receive their payments.

17. In addition to the issues with claims processing mentioned above, weaknesses were identified with management of non-compliance (of which fraud is a component). There is limited guidance available to FEG processing staff regarding how to distinguish and manage the different types and severities of non-compliance and the administrative and legal remedies available for addressing non-compliance. In addition, there is no single register for recording, tracking and reporting occurrences of non-compliance. As a result, this information is not readily available to inform the ongoing fraud risk rating for the scheme and to inform management of the full extent of non-compliance for the scheme and the risk this poses. Examination of the department’s overall fraud control framework indicates a strong focus on investigation in response to fraud with limited emphasis on fraud prevention and fraud detection. As such, the department’s fraud control plan delegates a high level of responsibility for fraud prevention and detection activities to program managers and staff. If the department is to be assured that compliance and fraud are being effectively managed, it is important that staff are adequately supported in undertaking this task including through training and guidance from qualified fraud control experts.

Stakeholder Engagement (Chapter 3)

18. Information for stakeholders on the core elements of FEG has been developed and made available by the department. However, information for claimants on the timeliness of claims processing is limited. To better support claimants to make decisions regarding their future financial and employment options, there would be benefit in the department providing more information to claimants regarding average processing times and the status of their claims.

19. The department does not survey claimants to seek their views on the FEG process or to seek feedback regarding areas of potential improvement. The only means of gauging claimant satisfaction is through data collected as part of the scheme’s complaints and feedback process. However, the department did not establish a formal complaints and feedback process until May 2013, limiting the usefulness of this data for examining trends and the impact of the recent period of change and disruption.

20. Feedback from insolvency practitioners interviewed by the ANAO regarding the effectiveness of the department’s administration of FEG was largely positive, with most insolvency practitioners satisfied with the information available about the scheme and their interaction with the department. While generally satisfied with the department’s overall administration of the scheme and the transition to the FEG legislation, insolvency practitioners raised concerns regarding the department’s management of the transition to the new stage-based claims process, highlighting that they had not been informed by the department of the change and once delays occurred. In view of the importance of the role of insolvency practitioners as part of FEG, there would be benefit in the department consulting further with insolvency practitioners to ensure the working relationship is maintained.

Reporting and Evaluation (Chapter 4)

21. When the department transitioned to a stage-based processing model in August 2013, the scheme’s focus moved from processing claims at the company level to the individual claim level. It took some time for the department to make changes to the processing system to support this new focus; however in June 2014 enhancements to the processing system allowed for the tracking of individual claims as they progress through the claims process.

22. In both reporting on FEG in its annual report to Parliament and outlining the proposed allocation of resources in the Portfolio Budget Statements, the department’s reporting focused on outputs (referred to as ‘departmental outputs’), rather than reporting against outcomes, which is generally expected for government programs. The department has done this because of the nature of the entitlements scheme and its primary aim to protect employees from the loss of their entitlements. There is scope for the department to improve the individual measures for FEG to ensure they provide an accurate view of the performance of the scheme and the effectiveness of the department’s administration. The public sector’s performance reporting framework is currently subject to change as a result of the introduction of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013. New guidelines in relation to performance reporting are expected to be introduced in early 2015. This change provides an opportunity for the department to examine its reporting for FEG and to seek to align this with the new reporting arrangements.

23. Since the commencement of the various entitlements schemes in 2000 only limited focus has been given to evaluation and analysis of the scheme and how it integrates with other government initiatives aimed at protecting employees and regulating business. More recently, the sustained demand and rising cost of the scheme has led to greater scrutiny of the design of scheme components and highlighted the need for a better understanding of how the scheme is contributing and operating alongside other government initiatives. There is opportunity for the department to undertake periodic analysis to better position it to support policy making, assist in program management and strengthen accountability.

Summary of the Department of Employment’s response

24. The Department of Employment’s summary response to the proposed report is provided below. The full response is provided at Appendix 1.

The Department welcomes the report on the Department’s delivery of the Fair Entitlements Guarantee programme.

The Department is modifying its fraud control framework so that greater support with specialised fraud and non-compliance resources is available to programme areas to prevent and detect fraud. The Department recognises the need for timely assistance to be paid under the programme and is implementing a strategy aimed at addressing claims processing backlogs by end of June 2015. The Department will also consider the other programme enhancement suggestions identified by ANAO in the report.

Recommendation

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 2.43 |

To enhance the effectiveness of fraud controls for the Fair Entitlements Guarantee, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Employment strengthen its focus on the areas of fraud prevention and detection. Department of Employment’s response: Agreed |

1. Introduction

This chapter provides background information and context to the Fair Entitlements Guarantee. The audit objective, scope, criteria and approach are also included.

1.1 Since 2000, successive Australian Governments have provided a safety-net to help protect employees from losing all their accrued employment entitlements, such as wages, unused annual leave, long service leave and redundancy pay, due to the insolvency of their employer. This support is currently provided through the Fair Entitlements Guarantee (FEG). In 2013–14, FEG provided support to 11 255 employees from 1 536 insolvent entities, approximately 16 per cent of the 9 82221 companies reported by the Australian Security and Investments Commission as entering external administration during this same period.22

1.2 The first government scheme of this nature was the Employee Entitlements Support Scheme (EESS), which commenced on 1 January 2000 following a number of insolvencies in the mining and textile industries that resulted in the loss of workers’ entitlements.23 In response to the high-profile collapse of the Ansett group of companies, the then Government announced a separate scheme specifically to assist Ansett employees known as the Special Employee Entitlements Scheme for Ansett group employees (SEESA).24 Coinciding with the establishment of the SEESA, the Government announced replacement of the EESS with the General Employee Entitlements and Redundancy Scheme (GEERS).25 Each of these schemes was delivered through administrative arrangements, imposing no legal obligation on government to make an advance and providing government with discretion regarding a claimant’s eligibility and the amount of any advance.26

1.3 The GEERS was subsequently replaced in December 2012 with the passage of the Fair Entitlements Guarantee Act 2012. The FEG Act states it is ‘An Act to provide for financial assistance for workers who have not been fully paid for work done for insolvents or bankrupts, and for related purposes.’27 FEG applies to all claims relating to insolvencies that occurred on and after 5 December 2012.

Purpose of the scheme

1.4 When the then Government introduced the FEG Bill to Parliament on 30 October 2012, it described the aims of the Bill as:

to provide a scheme for the provision of financial assistance (called an ‘advance’) to former employees where the end of their employment is linked to the insolvency or bankruptcy of their employer. After making an advance, the Commonwealth assumes the individual’s right to recover the amount that was advanced through the winding up or bankruptcy process of their employer.28

1.5 FEG was established with the aim of protecting employees’ access to the work entitlements they are owed. It operates alongside other government welfare programs designed to provide support to alleviate the financial and personal hardship imposed on employees as a consequence of losing their employment such as income support, employment services and financial advice services.

1.6 Many claimants will, due to their personal circumstances, place priority on the payment of the FEG advance to cushion the impact of their unemployment and help them make the transition to new employment. While some employees may find alternative employment quickly, placing less reliance on the advance, others may require the financial support paid by FEG to bridge any gap while they consider their financial and employment options. These circumstances are recognised through provisions in the FEG Act designed to ensure payment of entitlements is timely. It is also recognised through the design principle of the scheme that avoids the need for employees to wait until finalisation of the winding up of the employer’s business before seeking any residual amount outstanding through FEG.

1.7 The FEG Act sets out the trigger events for the advance, the criteria for determining eligibility and the method of calculating the amount of the advance. The FEG Act also provides individuals the right of review of decisions through processes undertaken by the department, or by the Administrative Appeals Tribunal.29 Through provisions that create links to section 560 of the Corporations Act 200130 and section 109 of the Bankruptcy Act 1966,31 the FEG Act provides the Commonwealth with the same rights as a creditor of the company and the same right of priority of payment in the winding up of the company as the person who received the advance would have had.

1.8 To provide the department with access to information necessary to assess claims, the FEG Act sets out the terms for the use and disclosure of personal information by the department, insolvency practitioners (IPs), and other intermediaries involved in making payments to former employees. It also provides for the department to disclose personal information to certain other agencies.32 The department relies upon this provision to share information with the Australian Securities Investments Commission (ASIC) and the Australian Taxation Office (ATO). Once an advance has been made, the department shares details of this advance with other government agencies to allow necessary adjustments to be made if the claimant is the recipient of other government support.

Funding

1.9 Provision is made in forward estimates of budget expenditure for expected payments under FEG but as a demand driven program, actual payments reflect the total number of eligible recipients in a given year. For

2013–14, the provision for payments under the entitlements scheme was $192 million, with actual expenditure for this period reported as $197 million. The amounts allocated to FEG for the period to 2017–18 are shown in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: FEG and GEERS appropriations to 2017–18

|

|

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

|

Allocation for advances and fees paid to insolvency practitioners |

$218m(a) |

$200m |

$201m |

$198m |

Source: Data provided to ANAO by the Department of Employment.

Note (a): For the 2014–15 financial year only, the allocation includes outstanding GEERS advances and fees paid to insolvency practitioners relating to the remaining GEERS claims.

How the Fair Entitlements Guarantee operates

1.10 To be considered for an advance under FEG, an individual must qualify as an eligible claimant. Directors of the company and their relatives are not eligible for assistance. Contractors, including new employees that previously worked as contractors, are also excluded. An eligible claimant under FEG is a person:

- whose employment has ended;33

- who is an Australian citizen or the holder of a permanent visa, at the time their employment ended;

- whose former employer suffered an insolvency event34 on or after 5 December 2012;

- who is owed certain employee entitlements by the former employer; and

- who has taken reasonable steps to prove those debts in the winding up or bankruptcy of the employer.

1.11 The claimant must also submit an ‘effective’ claim. An effective claim uses the FEG claim form, is accurate and includes all mandatory information. It also includes supporting documentation that proves the claimant’s Australian citizenship, or possession of a permanent or special category visa at the time the employment ended. An effective claim must also be made before the end of 12 months after either the insolvency event or the end of employment, whichever is later.35

1.12 The primary source of information needed to assess outstanding employment entitlements for eligible claimants is provided by the insolvency practitioner (IP),36 appointed to administer the employer’s insolvency.37 The department relies upon the IP to provide information from the former employer’s books and records to verify claimant’s eligibility for a FEG advance and the amount of any advance. The department also relies on IPs to distribute FEG advances. There is no requirement for an IP to assist the department and in some cases the IP may be unwilling to assist, for example where there are insufficient funds to be realised from winding up the company. Where this occurs, the department may engage another service provider to undertake this work (generally a qualified accountant), or depending upon the circumstances of the insolvency and the number of claimants involved, the department may undertake some of this work itself. The service providers are also able to distribute payments on behalf of the department38 and may also assist investigate issues associated with complex claims, or suspected fraud and noncompliance.

1.13 The department also relies upon information provided by the claimant as part of the application process, including details of their employment contract, terms and conditions of employment and entitlements they are owed as well as an estimate of the value of these. There are circumstances where the department may gather information from alternative sources to validate, or supplement information provided by the IP and claimant, particularly where the employer’s books and records are of poor quality, or are not available, or the information provided by the IP and claimant is inconsistent.

1.14 A claimant’s employment entitlements are determined through reference to the governing instrument39 in relation to the claimant’s employment. The governing instrument sets out the terms and conditions of each individual’s employment and can take the form of an industrial award, collective agreement, or contract of employment.40 Determining the appropriate instrument is relatively straightforward where an agreement applies to the former employer. However, where there are no agreements in place this process is more difficult and relies upon an assessment of the type of work performed by the claimant and the nature of the business of the employer at the time the employment ended. In some circumstances, more than one governing instrument may be applicable.

1.15 As a safety-net scheme, FEG does not necessarily compensate claimants for all their unpaid employee entitlements. As such, the advance is determined with reference to caps that limit the amount payable to claimants. Applicable to all entitlements is the ‘maximum weekly wage’, which is used for calculating entitlements where the weekly rate of pay, as set out in the relevant governing instrument, exceeds the maximum weekly wage amount.41 The entitlements available under FEG and the caps applicable to each are described in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: Employee Entitlements covered by FEG and GEERS

|

Entitlement |

Conditions (a) |

|

Wages |

The person’s wages entitlement is the amount of wages the person is entitled to under the governing instrument from the employer for work done, or paid leave taken, in the wages entitlement period. A cap of 13 weeks’ pay applies. |

|

Annual leave |

The amount that the person is entitled to under the governing instrument and which has accrued at the end of employment but had not been taken. |

|

Long service leave |

The amount that the person is entitled to under the governing instrument and which has accrued at the end of employment but which had not been taken, or on account of long service leave that, had the person’s employment continued until the person qualified for long service leave, would have been attributable to the period until the actual end of the person’s employment. |

|

Payment in lieu of notice |

The shortfall in the period of notice of termination of employment. This is capped so that it does not exceed 5 weeks’ pay. |

|

Redundancy(b) |

The amount an employee is entitled to under the governing instrument for the termination of the employment. This amount is capped so that it does not exceed four weeks’ pay for each full year of service and pro-rated for less than a full year of service. |

Source: ANAO.

Note (a): Applicable to all entitlements is the maximum weekly wage, which is used to calculate the amount of the entitlement where the employee’s weekly rate of pay exceeds the maximum weekly wage amount.

Note (b): Prior to January 2011, the GEERS scheme capped redundancy entitlements to 16 weeks. From this date, the then government increased the cap to four weeks per completed year of service.

1.16 Once the governing instrument has been identified and it has been determined whether the maximum weekly wage applies, the basic amounts for each of the entitlements can be calculated in accordance with the guidance contained in the FEG Act. Prior to authorisation of the payment by the departmental delegate, the department will verify the advance amount with the IP and seek their agreement to it. The department seeks verification of the advance with the IP to validate the basis for its calculation and because in the event that funds can be paid to creditors at conclusion of the winding up of the employer, the department can assume that this amount will be paid by the IP as a dividend.

1.17 The claimant is notified of the outcome of their claim through a letter detailing the advance amount for each entitlement and the basis for its calculation. If the claimant believes there has been an error in the determination of their eligibility or the calculation of their advance, the FEG Act provides for claimants to request a review of their claim by the department, or by the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT). The FEG Act also provides for the department to initiate an internal review where it identifies potential errors, or issues.

1.18 The advance is paid by the department to an intermediary (generally, the IP or bankruptcy trustee of the employer, or a third party nominated by the department). The advance is then paid to the claimant by the intermediary subject to any withholding or deductions required by law. Once the advance has been paid, the government assumes the same rights and priority as the employee in the recovery of the amount of the advance as part of the winding up of the employer.

Audit objective, criteria and methodology

Audit objective

1.19 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Employment’s administration of the Fair Entitlements Guarantee.

Audit criteria

1.20 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO’s

high-level criteria considered whether operational elements of the scheme are well managed, the treatment of claimants, and whether performance of the scheme is effectively measured, monitored and reported.

Audit methodology

1.21 The audit focused on the current employee entitlements scheme, the Fair Entitlements Guarantee (FEG), under which claims have been processed since 5 December 2012. The scope of the audit included the department’s processing of FEG claims, from lodgement and assessment of eligibility through to payment of advances to eligible employees, with particular attention to the management of operational risks associated with processing accuracy and timeliness; and fraud control measures. The ANAO examined the appeals processes available to applicants and claimants seeking internal review of their case, or external review by the Administrative Appeals Tribunal, and the department’s procedures for recovery of advances as a creditor in the winding up of the employer.

1.22 The audit methodology included examination of: business and system processes and procedures associated with assessment of claims and payment of advances as well as the recovery of entitlements; scheme related documentation; scheme monitoring and reporting; processing systems used to store information and process claims; and program monitoring and reporting.

1.23 The approach also involved interviews with stakeholders, including: departmental staff and managers; insolvency practitioners and their peak body association; third party service providers; and representatives from the Australian Taxation Office, Australian Securities and Investments Commission and Attorney General’s Department. The ANAO also met with representatives of other government agencies with responsibility for administration of similar payment initiatives to examine specific operational aspects including identity proofing and fraud control.

1.24 The audit methodology included drawing a sample of claims from the department’s claims processing system. The sample was examined to assess whether claims have been processed in accordance with the FEG Act.

1.25 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of $440,000.

Report structure

The remainder of this report is structured as follows:

|

Chapter |

Overview |

|

Chapter 2— Managing Scheme Risks |

This chapter examines the key operational priorities in relation to administering the financial assistance provided under FEG, and in the context of these priorities, the Department of Employment’s approach to managing risks to effective service delivery. This chapter also considers the recovery of advances as part of the winding up of the employer’s business. |

|

Chapter 3— Stakeholder Engagement |

This chapter examines the effectiveness of the Department of Employment’s engagement with key stakeholders for FEG, including claimants, insolvency practitioners and other agencies. |

|

Chapter 4— Reporting and Evaluation |

This chapter examines the Department of Employment’s framework for monitoring and reporting the scheme’s performance against the government’s objectives, focusing on program evaluation, the Portfolio Budget Statements and reporting in the department’s annual report. |

2. Managing Scheme Risks

This chapter examines the key operational priorities in relation to administering the financial assistance provided under FEG, and in the context of these priorities, the Department of Employment’s approach to managing risks to effective service delivery. This chapter also considers the recovery of advances as part of the winding up of the employer’s business.

Introduction

2.1 As a scheme aimed at protecting employees who have been made unemployed as a result of the insolvency of their employer, timely processing of FEG claims is a priority. This priority is balanced by the need to ensure that advances are calculated accurately and that they are paid to the right recipients. This chapter examines the department’s recent performance against these priorities.

Scheme activity

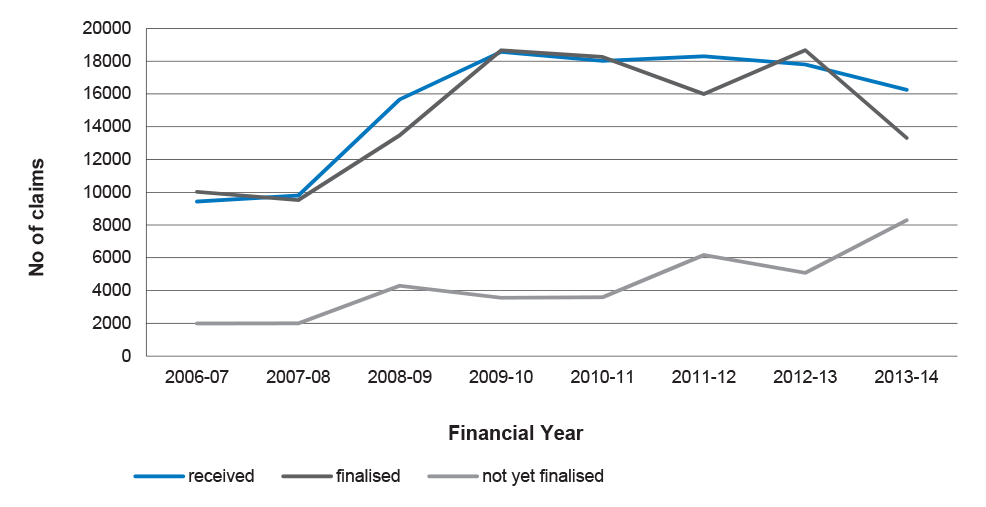

2.2 The global economic crisis42 increased demand for support provided by the then GEERS scheme. The department received 15 666 claims for assistance during 2008–09, a 60 per cent increase on 2007–08. While it attempted to keep pace with the demand—finalising 13 473 claims—the backlog of claims to be finalised grew, reaching 4 291 (as at 30 June 2008), nearly double the previous year. Demand for the scheme remained high between 2009–10 and 2012–13, with the number of claims received averaging approximately 18 000 each year.43

2.3 Providing some respite, in 2013–14, the number of new claims received by the department dipped to 16 246, 9 per cent less than the previous year. However, during this year, only 13 313 claims were finalised by the department—representing a 29 per cent reduction on the number finalised the previous year. Claims received, finalised and unprocessed since 2006–07 are shown in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: Claims received and processed since 2006–07

Source: Department of Employment data.

2.4 Consistent with these trends, the backlog of claims to be finalised gradually increased reaching 5 081 by the end of 2012–13 and 8 297 by the end of June 2014—at that time, the highest level since the employee entitlements schemes commenced in 2000.

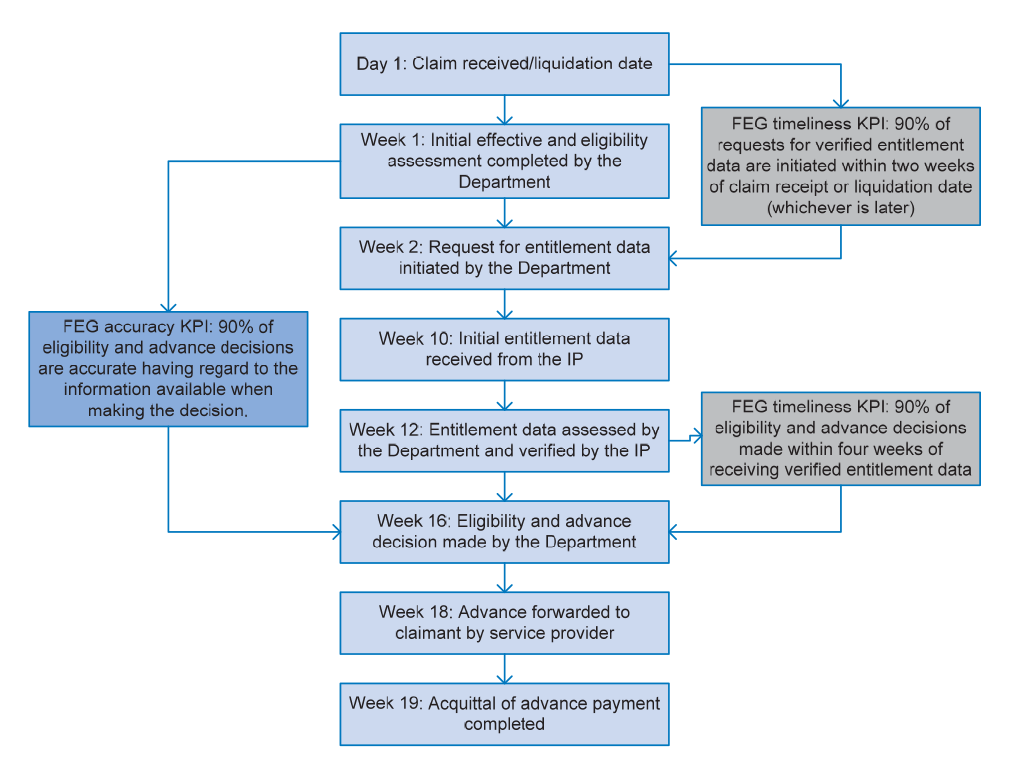

Timeliness of claims processing

2.5 The impact of the high levels of demand on the timeliness of claims processing is demonstrated by the timeliness measures reported by the department for finalisation of FEG claims. Prior to 2013–14, the department reported the scheme performance against an ‘ideal’ processing timeframe of 16 weeks.44 The proportion of finalised claims processed within the 16 week timeframe since 2007–08 is shown in Table 2.1, highlighting a gradual deterioration in performance against this measure since 2008–09, and a sharp decline in performance in 2013–14.

Table 2.1: Percentage of finalised claims processed within 16 weeks

|

2007–08 |

2008–09 |

2009–10 |

2010–11 |

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

|

93 |

93.6 |

91.7 |

88.6 |

79 |

81.4 |

36.3 |

Source: Data provided by the Department of Employment.

2.6 The introduction of the FEG Act in December 2012 and more critically, the move to a new claims processing model commencing in August 2013 resulted in further delays in finalising claim assessments. In its 2013–14 Annual Report the department summarised the challenges it faced as a result of these changes as follows:

During 2013–14, significant changes were made to the administration of claims under the Fair Entitlements Guarantee to finalise the transition to the legislative arrangements for the scheme that were introduced in 2012–13. Business processes and workflows were redesigned and business systems were reconfigured to increase the quality and efficiency of the administration of the programme and achieve stronger programme compliance. These changes to the operating environment resulted in transitional disruptions to the claims workflow and delays in finalising claims assessments. The department is closely monitoring the timeliness of claims processing and ensuring that there are minimal delays for claimants.45

Transition to a legislative framework

2.7 The FEG Act substantially replicates the administrative arrangements under which the GEERS scheme operated; key changes include provision of a more transparent process for determining eligibility, provision for the department to initiate internal review of decisions and a statutory right for claimants to seek review to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT).

2.8 Overall, the department’s approach to the transition was effective. To ensure the efficient transition from GEERS to FEG, the department commenced preparatory work during 2012. This included: communication of the change and its impact to key stakeholders, including insolvency practitioners (IPs) and potential claimants; training of staff; and development of new guidance material, procedures, correspondence and application forms as well as changes to support parallel processing of FEG and GEERS related claims. These activities were managed by the department as part of a discrete project that was finalised in early 2013. During this time, the department gave priority to external facing elements of the transition to ensure stakeholders were informed of the change and that potential claimants could access the new claims form, lodge their claim and receive their FEG payment. Elements such as refinement of the processing system, documentation and staff training, were given less priority, with the view that these would be refined progressively as experience with the new scheme developed and in parallel with the natural increase in the number of claims expected to be received during the initial months.46 Phasing out of the GEERS scheme and full implementation of FEG occurred over 2012–13, extending into 2013–14, as the flow of FEG claims gradually increased.

2.9 To inform IPs of the FEG legislation, the department circulated an information bulletin to each IP that had been involved with the scheme during the preceding 12 month period. The department also discussed the legislation with the IP representative body, the Australian Restructuring, Insolvency and Turnaround Association (ARITA), and provided information for inclusion on the ARITA website and quarterly magazine. The IPs interviewed by the ANAO as part of this audit indicated that they were generally satisfied with the department’s work to inform them of the FEG legislation and with the guidance material provided by the department. Similarly, representatives from ARITA also noted their general satisfaction with the department’s process for implementing and consulting with them regarding the FEG legislation.

Transition to a new claims processing model

2.10 While the transition of the scheme to a legislative base under the FEG Act did not result in significant changes to the conditions of the scheme, or the manner in which claims are assessed, the legislation’s more precise expression of the conditions and the evidence required to support decisions, removed some of the flexibility, as well as complexity, of the previous arrangements. This placed greater emphasis on internal processes to ensure consistent and objective decision making underpinned by clear delegations, accurate information and complete records.

2.11 To better position the scheme to meet these expectations, in August 2013, the department moved to a new stage-based model for processing FEG claims. Prior to August 2013, claims were managed at the company-level (referred to as a ‘case’), with a case manager responsible for managing each case and the individual employee claims it comprised. The case manager was responsible for all steps in the claims process from the initial determination of eligibility, through to assessment of the entitlements and informing the claimant of the final decision (a decision-maker with appropriate delegation reviewed the claim determination and authorised the claimant’s advance). This approach provided a number of benefits; case managers would gain a high level of familiarity with each case and provide a single point of contact for both the IP and the company’s former employees. However, this approach required case managers to be knowledgeable and proficient across all aspects of the claims process. In addition, the high volume of claims being managed at any point in time made it challenging to track claims and ensure the quality of decision-making and compliance with the operational arrangements.

2.12 By contrast, the new claims processing model involves processing claims in ‘stages’, with staff responsible for a set of common tasks associated with each stage. This approach moved the focus from managing claims at the company-level to managing at the individual claim or employee level. This aligns with the FEG legislation which expresses provisions at the individual claim level, rather than the case level. The stage-based approach also provides greater flexibility in the distribution of work to staff, and for quality checking and monitoring of claims as they progress from one stage to the next.

2.13 This change was significant and high risk; every element of the claims assessment process was affected, staff were required to learn and adjust to a new way of operating and the claims processing system required significant enhancements in order to fully support stage-based claims processing at the individual claim level and to provide the visibility necessary to monitor workflow and report status. Notwithstanding, the department did not, prior to proceeding, seek to identify, assess and manage risks to its successful implementation. The department proceeded with the change despite having only limited documentation defining roles and responsibilities and describing the new claims processing arrangements. The department was also aware that the existing processing system had limitations that impacted its ability to provide visibility of the workflow of claims and to report on the status of the claims assessment process.47

2.14 In addition, the department did not formally communicate with IPs its plan to undertake this change and the impact it would have on procedures directly relevant to IPs. A number of IPs interviewed by the ANAO stated that the change was not broadly communicated prior to its implementation, or once issues arose. IPs also noted difficulties contacting departmental staff responsible for the claims they were working on—a situation made more difficult by the need for IPs to work with various staff depending upon the processing stage of the claim, rather than a single case manager, as with the previous arrangements.48

2.15 The new processing model was implemented in August 2013. Between October and December 2013, a relatively high number of claims were finalised giving the impression that the new model was functioning well. However, a sharp drop in the number of claims finalised between January and April 2014—coinciding with a gradual increase in claims received—led to a rise in the backlog of claims, with the number of unprocessed claims increasing by 34 per cent between January and June 2014.

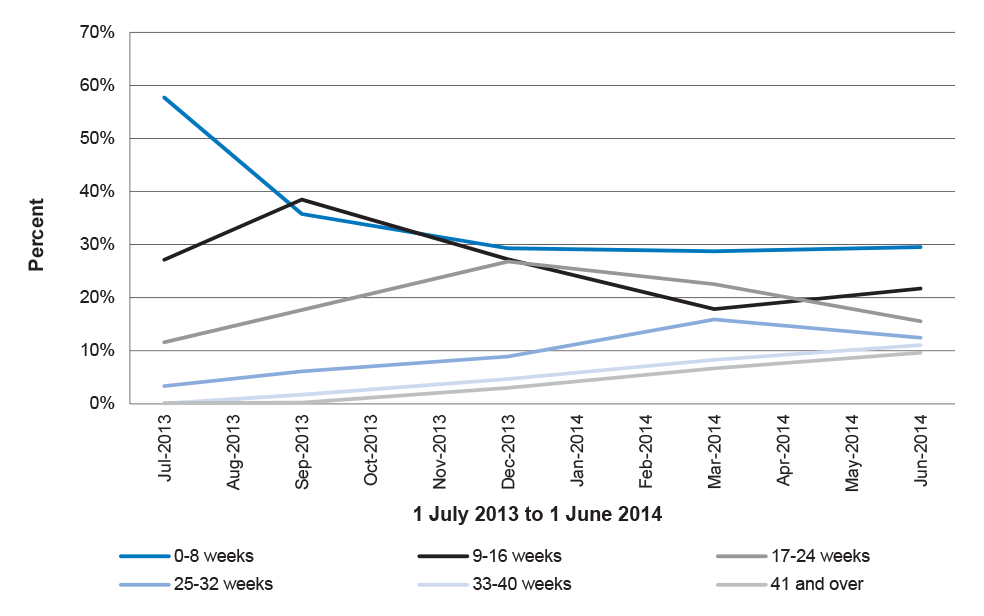

2.16 As a result of these issues, the average time to finalise a claim doubled and the number of claims older than 16 weeks increased from 878 to 4 467 between July 2013 to June 2014. Increases in the proportion of ‘aged claims’ is shown in Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2: Proportion of claims held each month, by age

Source: Compiled by the ANAO using data provided by the department.

2.17 A key contributor to this backlog was the department’s decision to change the sequencing of processing activities at the same time it introduced the new processing model in August 2013. As part of this arrangement, the relevant governing instrument for each claim was identified by the department prior to seeking information from the IP—this task was previously undertaken by the IP as part of their role to verify the claimant’s data.

2.18 The department has extensive knowledge of the different governing instruments and considered it was in a better position than the IP to identify the relevant governing instrument for each claimant. On this basis, the department sought to streamline the process by identifying the governing instruments prior to seeking claimant information from the IP and reducing its reliance on the IP to complete this task. However, the department did not assess the risks associated with the change and underestimated the complexity and time it would take to perform the task. The sequencing change lead to a bottleneck occurring early in the claim assessment process. The department’s failure to quickly identify and address the issue contributed to the resulting backlog of claims.

2.19 In early 2014, to address the resulting bottleneck, resources were reallocated to improve the balance between the number of staff and workload demands. The department also implemented a two stream processing approach to focus on clearing the backlog of older claims. Despite these changes a performance report prepared by the department for the December 2014 quarter showed that the backlog of unprocessed claims was continuing to increase, reaching 9 153 by the end of December 2014. The proportion of claims older than 16 weeks also deteriorated during period, increasing from approximately 50 to 59 per cent of all claims.

2.20 The transition to the new processing model could have been better managed by the department. The significance of the change and the risks it posed warranted a higher level of management and oversight than initially applied by the department. More thorough planning, including early identification and ongoing management of risks would have better positioned the department to undertake this change.

Accuracy of payments

2.21 The accurate assessment of claim entitlements is important to ensuring that claimants are not disadvantaged by receiving lower entitlements than they are due, or delayed in accessing their funds. Equally important is the avoidance of overpayment of funds to claimants, particularly as it is less likely that these will come to light as the result of an appeal by the claimant, placing greater reliance for detecting these errors as part of internal checks and controls. Accurate claims assessment also contributes to greater efficiency by reducing costs associated with reviews, re-work and the pursuit of debts in cases of overpayment.

2.22 Interviews with departmental staff and managers involved with FEG claims processing indicate a high-level of awareness of the importance of accuracy of payments and quality decision making is well-understood by staff involved in the FEG claim process. This focus largely stems from the recent transition to the legislative base and recognition of raised expectations associated with this change, particularly in regard to the requirement for consistent, accurate and supportable decision-making. However, with the FEG scheme in place since December 2012, it is timely for the department to develop a more systematic approach to quality assurance underpinned by a program of staff training, detailed procedural documentation covering all aspects of the claims process and clearly defined roles and responsibilities.

2.23 To support staff, an operations manual was developed at the time FEG commenced in late 2012 and this document has been regularly updated. A central knowledge repository has also been established and is regularly updated and accessed by staff. A number of the processing staff have also developed their own guidance material covering their areas of responsibility. There would be benefit in centrally coordinating development of detailed procedural documentation to ensure alignment with other guidance and reference material, including the operations manual.

2.24 To monitor and measure quality, the department currently refers to the number of requests from claimants for review of decisions relation to the eligibility and advance amounts. While the level of accuracy reported by the department is consistently high (above 98 per cent), there would be advantage in the department adopting an approach to checking and monitoring quality in real-time. This would provide assurance that decisions are correct and that information supporting decisions is accurate. This approach could include establishment of quality controls at each stage of processing to monitor the quality of tasks specific to the stage and periodic examination of a random sample of finalised claims aimed at testing the accuracy of decisions and compliance with procedures and the legislation.

Managing non-compliance

2.25 Non-compliance49 is a particular risk for programs such as FEG which involve the provision of direct financial assistance. To provide guidance on the management of compliance and to assist departmental staff meet their responsibilities under the department’s fraud control plan, the department developed a document, referred to as the Basics of Compliance50. This document sets out responsibilities for compliance as follows:

In short, all employees are responsible for compliance. Responsibility for management of compliance, particularly in establishing and implementing a compliance programme, sits with policy, business or programme areas of the department. Policy/program areas have a detailed knowledge of the relevant programme, providers, services and/or policy which equip them to effectively tailor a programme to ensure compliance. Only where non-compliance may be criminal in nature, should the matter be referred to the Investigations Branch (which has expertise in conducting criminal investigations).51

2.26 Non-compliance may occur because of a lack of understanding or awareness of obligations or because of disregard, or carelessness. For fraud to be established there must be intent to commit the fraud. Where fraud is suspected the program area must consider whether it meets the department’s fraud referral threshold, as follows:

There has been non-compliance (a breach) with a legally enforceable obligation and it appears more likely than not that dishonesty is the cause (as opposed to incompetence, mistake or misinterpretation of contractual or legislative parameters).52

2.27 Suspected fraud is referred to the Shared Service Centre’s (SSC’s)53 Investigations Branch which then assesses the circumstances of the alleged fraud to determine whether to proceed with an investigation. This assessment is based on consideration of the following factors:

- there is evidence of an offence against the Commonwealth;

- the department has jurisdiction to investigate the matter (some cases are referred to the State or Territory police or other agencies if appropriate, depending on issues of criminal jurisdiction);

- there are reasonable prospects of a successful prosecution (if an investigation proceeds);

- prosecution of the matter would have a stronger deterrent effect for the programme than an administrative sanction; and/or

- a costly investigation will result in the identification of vulnerabilities for the department (and ultimately continuous improvement of the department’s fraud control mechanisms).54

2.28 Where the Investigations Branch does not proceed with an investigation, the alleged fraud is referred back to the program area for resolution. This may include further investigation, or administrative or civil sanctions. Similarly, issues of non-compliance that do not meet the fraud referral threshold (referred to in paragraph 2.26) are also managed by the program area.

FEG compliance strategy

2.29 There is no single approach to addressing non-compliance and it is generally accepted that a range of response options are needed that are proportionate to the perceived risk. This point is reinforced in the department’s fraud control plan which notes the importance of having a ‘graduated and proportionate’ response to both non-compliance and to fraud that does not warrant investigation, including where appropriate, administrative sanctions.55

2.30 The department’s Basics of Compliance document emphasises the importance of programs having a compliance strategy and provides guidance—adapted from the relevant Australian Standard56—on the minimum elements of a compliance strategy. These are summarised as:

[The] Compliance Strategy needs to identify who is responsible for the prevention, detection and correction mechanisms for that programme and ensure that those personnel are aware, resourced and trained to fulfil those responsibilities. The risk assessment assesses the risk and provides possible treatments, but the compliance strategy mobilises staff, communicates how, when and why and provides the plan for addressing risks identified.57

2.31 The FEG compliance strategy is outlined in a document titled, FEG Programme Compliance Strategy58. However, the strategy outlined in this document lacks the detail necessary to inform and equip staff to identify and manage non-compliance. The document is high-level and descriptive, with limited focus on the specific areas of compliance risk associated with the FEG operating environment. Similarly, there is no cross-reference to the FEG risk assessment and the fraud or compliance risks identified as part of this process.

Monitoring non-compliance

2.32 It is generally considered sound practice for all compliance decisions, along with the reasons for the decisions and the evidence relied upon in reaching the decisions to be documented. This supports transparency and accountability, particularly where a decision may be challenged at a later date.59

2.33 Documentation providing details of actual and alleged cases of fraud within FEG was sound where matters were accepted for investigation by the SSC Investigations Branch. For these cases, the departmental executive and the audit committee have visibility of the details of each case, and the status and outcome of the investigation. However, the documentation of matters that do not meet the threshold for further consideration, or matters that are not accepted by the Investigations Branch, was less complete and reporting processes less well defined.

2.34 The department advised that the audit committee had visibility of the fraud risks and the control environment (including any actual, alleged or suspected material fraud—both internal and external). However in practice, there is no formal requirement for the program area to regularly report non-compliance and alleged fraud to the audit committee. Within FEG, there is currently no single register that captures all incidences of non-compliance and alleged fraud and records details of their status and treatment. The department advised that a register was not necessary given the low incidence of non-compliance, the existence of the Tip-off register60 and the arrangement for referral of fraud issues to the Investigations Branch. While the incidence of non-compliance detected by the department may be low, it may also be a consequence of the weaknesses in the FEG compliance strategy. The approach adopted means that there is no single point of reference for managing and monitoring the progress of all non-compliance issues, for identifying the extent and materiality of non-compliance for FEG and importantly, for assessing the non-compliance risk for the scheme.

Fraud control arrangements

2.35 Sound fraud control61 is fundamental to programs such as FEG that rely on third-parties to verify claimant data and to distribute advance amounts to claimants. For FEG, the fraud risk is further elevated as a result of frequently unavailable or poor quality documentation to assess and determine advance amounts, and pressures associated with the current high level of demand and the large backlog of claims.

2.36 Integral to the Australian Government’s risk based approach to fraud prevention and detection is the fraud risk assessment process. It is through this process that the level of fraud risk exposure for initiatives is assessed, management strategies developed and importantly, the fraud control plan is tailored to address areas of potential fraud exposure.62 The department’s fraud risk assessment process forms part of the department’s general risk management framework. As part of this arrangement departmental staff are required to consider internal and external fraud risks as part of their regular monitoring and review of risks and their treatments.63 While the Commonwealth’s fraud guidance64 generally supports the integration of fraud risks within the entity’s risk control framework, it cautions that where a program has an inherent risk of fraud due to the nature of its business—for example, revenue collection, payment of benefits or contract procurement activities—the entity should consider developing a fraud risk assessment process that is specific to a particular policy or program area.65

2.37 The Commonwealth fraud guidance emphasises the importance of having access to specific fraud expertise when undertaking risk assessment and fraud control planning:

Risk assessments can be undertaken using in-house resources, but it is important to ensure that the risk assessment team has access to the range of skills, knowledge and expertise necessary to provide coverage of the categories of risk to be considered.66

2.38 At the time of the audit, there had generally been little active support provided to FEG staff to access relevant expertise and notwithstanding the level of risk for FEG, the FEG fraud risk management plan identified only two fraud related risks. Based on the treatments identified to mitigate these risks, the residual risk67 for FEG was rated as ‘low’. The fraud risks and proposed treatments are set out in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: GEERS and FEG fraud related risks and treatments

|

No. |

Risk |

Treatment |

|

1 |

Provision of misleading or fraudulent advice by external claimants |

|

|

2 |

Misappropriation of funds by insolvency practitioners working in collusion with GEERS and FEG claimants |

|

Source: Department of Employment.

Note (a): GOLD is the name given to the system used to process claims and store claimant information.

Note (b): In September 2014, the department confirmed that this work is at the initial scoping phase.

Note (c): Refers to the former Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations.

2.39 The risks are broadly defined and as such, encompass a number of important risks that under the circumstances, warrant separate identification and management; for example the department’s process for proofing the identity of FEG applicants. The requirement that all claimants provide identification documentation is identified in the FEG risk register as a treatment for both risks. However, the department’s reliance on certified photocopies, rather than originals to verify the claimant’s identity itself presents a risk.

2.40 The department advised that it considered the existing identity proofing arrangements were reasonable and practical having regard to the size and nature of FEG. However, given FEG payments are a single one-off payment and the amounts paid to individual claimants can approach $300 000,68 there would be benefit in the identity proofing process being identified as a risk in order for it to be managed and mitigated, and for this information to inform the overall risk rating for the scheme.

2.41 Routine testing of the effectiveness of proposed fraud risk treatments would strengthen the department’s approach for FEG and may result in the reassessment of the scheme’s overall fraud risk. For example, the department identified the ‘separation of roles between DEEWR69 and IPs to verify authenticity of claims’ as a treatment for the risk that IPs may collude with claimants to misappropriate funds. The department is reliant upon the IP administering the insolvency of the employer to provide and verify employment information which it then uses to calculate the advance amount for eligible claimants. While the department and the IP have separate roles, this does not mitigate the risk of the IP misappropriating funds, as the department has no alternative source against which to verify the information being provided by the IP—under circumstances where the IP was potentially colluding with the employer or employee, information provided by these sources would be equally unreliable.

2.42 The management of compliance and fraud for the FEG is influenced by the department’s overall fraud control framework. This framework adopts an approach reliant on conducting investigations after fraud has occurred, with limited focus on the areas of fraud prevention and detection. As part of this framework, responsibility for the fraud prevention and detection is largely devolved to program staff and managers with only basic levels of fraud training and with limited active support from fraud specialists to assist them fulfil these responsibilities. At the time of the audit, staff were expected to complete fraud awareness training, however this training was not sufficient to equip staff to effectively fulfil the responsibilities outlined for them in the fraud control plan. If the department is to be assured that compliance and fraud is being effectively managed, it is important that the specialist nature of fraud control be recognised along with the risks associated with delegating this responsibility without adequate training or appropriate guidance from qualified fraud control experts.

Recommendation No.1

2.43 To enhance the effectiveness of fraud controls for the Fair Entitlements Guarantee, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Employment strengthen its focus on the areas of fraud prevention and detection.

Department of Employment’s response:

2.44 Agreed. The Department of Employment is modifying its fraud control framework to introduce greater support around fraud and non-compliance for specific programme areas.

Recovery of advances

2.45 Arrangements have always been in place to allow the department to recover advances made to employees through insolvency processes. As part of the liquidation of an insolvent company the liquidator winds up the company and realises the company assets. If there are funds left over after payment of the costs of the liquidation, and payments to other priority creditors (including employees) the liquidator will pay these to unsecured creditors as a dividend. Generally, the order in which funds are distributed is:

- costs and expenses of the liquidation, including liquidators’ fees;

- outstanding employee wages and superannuation;

- outstanding employee leave of absence (including annual leave, sick leave—where applicable—and long service leave);

- employee retrenchment pay; and

- unsecured creditors.

2.46 Once an advance has been made to a claimant, government is subrogated into the position of the employee and assumes the rights of the employee as a creditor in the winding up of the former employer’s business. In the event that the company is able to realise sufficient funds, the government recovers the amount of the advance and employees receive amounts outstanding beyond the advance. Notwithstanding the Commonwealth’s priority creditor status as part of the winding up of the company, less than $200 million (13 per cent) of the $1.5 billion distributed since the various employee entitlements schemes commenced in 2000, has been recovered—this is consistent with the generally low rate of recovery for unsecured creditors; in 2013–14 the Australian Securities and Investments Commission reported that in 97 per cent of cases the dividend payable to unsecured creditors was estimated to be less than 11 cents in the dollar.70

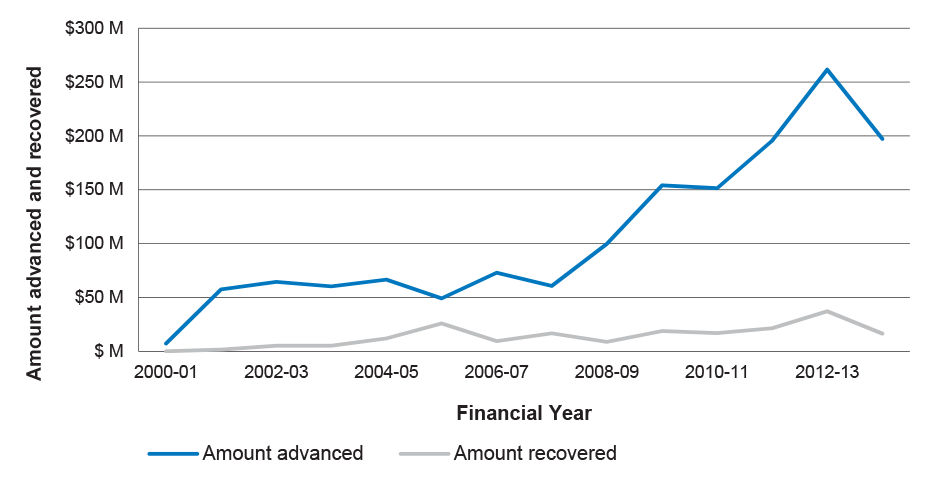

2.47 The amount recovered by government since 2000–01 against the amount paid by government in advances over this same period is shown in Figure 2.3. While the increase in the amount advanced from 2008–09 to date, may be attributable to the impact of the global economic crisis and the removal of the cap on redundancy payments, the department has not undertaken any analysis of this, or how it correlates to the proportion recovered each year.

Figure 2.3: Advances to employees and recovery from employers (a),(b)

Source: ANAO compilation of data from the Department of Employment.

Note (a): The data does not include the advances relating to the special scheme for Ansett employees.

Note (b): Recoveries do not necessarily correlate to the year in which the advances were made due to the time lag between advances to employees and recovery from the employer’s liquidation.

2.48 As a creditor in the winding up of the former employer’s business, in addition to participating in dividends, government has the right to: participate in creditors’ meetings; receive reports from the liquidator about the liquidation; inform the liquidator about matters relevant to the affairs of the company in liquidation; and raise issues with ASIC or the court about the liquidator’s conduct in connection with their duties. In certain circumstances where the company is without sufficient assets, creditors may agree to fund the liquidator to take action to recover further assets. If this action is successful, the liquidator or creditor can apply to the court for the creditor to be compensated for the risk involved in providing these funds.

2.49 While the department is aware of its rights as a creditor and monitors the progress of liquidations through reports provided by IPs, it does not generally participate in creditor meetings, or provide funding to support recovery action. In the past, the department has tested a more active role in the recovery of advances through conducting a pilot litigation program (2006). However, the pilot was discontinued after a year due to the low rate of return on investment. The department could more to actively pursue recovery of insolvency related debt, however it would need to consider the costs and benefits of this type of action, as well as the time lags associated with recovery. The Department of Employment has advised that it does not have the agreement of the then Government or dedicated funding to pursue a more active debtor role.

Conclusion

2.50 Changes initiated in August 2013 to align internal processes with the FEG legislation were poorly managed by the department and resulted in a large backlog of claims and delays for claimants receiving their FEG advance. This has been a significant setback for the department as it continues to place a priority on addressing the high number of unprocessed and aged claims. Issues that led to the backlog of claims could have been avoided or mitigated if greater focus had been given to identifying and managing risks associated with the change to the new processing model. However, the department proceeded with the change despite having only limited documentation defining the new roles and responsibilities and despite the claim processing system not having the functionality necessary to manage, track and report the status of individual claims and to monitor the claims workflow.

2.51 In early 2013, when issues were identified with the new claims processing arrangements, action was taken by the department to re-assign resources and for staff to work overtime to focus on bottlenecks in the claims process and to address the growing backlog of claims. The average time to process a claim reduced from 32 to 18 weeks over the July to September 2014 quarter, although high claim volumes during this quarter resulted in this extending to 26 weeks by the end of December 2014. The proportion of claims older than 16 weeks also increased to 59 per cent of all claims by the end of December 2014.

2.52 As a scheme that makes payments to claimants based upon information provided by a third party and sometimes with limited available documentation, these features imply an elevated level of non-compliance and fraud risk. Notwithstanding, the department has provided only limited information to instruct staff in the identification and management of non-compliance. While staff are required to undertake fraud awareness training, this basic level of training is not sufficient to equip staff with the knowledge to meet responsibilities devolved to them in the department’s fraud control plan. In addition, there is also no single register for recording, tracking and reporting non-compliance and no formal requirement that non-compliance issues being managed by the program areas are regularly reported to the departmental executive and audit committee. As a result, this information is not readily available to allow the executive and audit committee to make an informed assessment of the full extent of non-compliance and the overall fraud risk exposure for the scheme. There would be benefit in the department establishing a more active approach to fraud control for FEG by strengthening its focus on fraud prevention and detection. This could include as a practical step, increasing the level of support currently provided to FEG staff in relation to fraud control.

2.53 Arrangements have always been in place to allow the department to recover advances made to employees through insolvency processes. The ANAO examined the department’s work to recover advances from employers. Less than $200 million (13 per cent) of the amount distributed by the government since the commencement of the entitlements schemes has been recovered. While the department is aware of its rights as a creditor, it considers that it is currently not resourced to fulfil this role more actively.

3. Stakeholder Engagement

This chapter examines the effectiveness of the Department of Employment’s engagement with key stakeholders for FEG, including claimants, insolvency practitioners and other agencies.

Introduction

3.1 Effective engagement and communication with stakeholders is an important element of all government initiatives and should form a key consideration in their design, ongoing delivery and during periods of change. Genuine engagement and collaboration between the department and stakeholders helps to establish a sound basis for delivering services under FEG.

3.2 With the aim of the scheme to protect employers from loss of entitlements, scheme claimants are the department’s primary stakeholder group and key priorities for this group include: availability of information about the scheme; ready access; and timely payment. IP’s and other service providers are crucial to the delivery of the government’s employee entitlements scheme in that they verify claimant information and distribute advances to claimants. In administering FEG, the Department of Employment collaborates with a number of other Commonwealth agencies71, (including the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) and Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC)) to assist these agencies in their responsibilities regulating and overseeing company directors and IPs.

Engaging with scheme claimants

3.3 In general, effective delivery of support to claimants rests on claimants being aware of:

- the scheme, their eligibility and how to apply;

- approximate timeframes for processing claims;

- the progress of their claim;

- the basis for decisions regarding eligibility and advance amounts; and

- avenues for seeking a review or appealing a decision and for providing feedback, and complaints.

Awareness of the scheme

3.4 The FEG claims process is not initiated automatically when a business becomes insolvent. Instead, it is initiated by the employee once the insolvency event has occurred. In most cases, employees are informed of FEG by the IP responsible for managing the insolvency or liquidation of the employer, who will generally direct them to the FEG website or FEG hotline for further information and to lodge a claim.

3.5 IPs are well placed to inform employees about FEG; they are in contact with the employees, are able to identify and contact affected employees and are aware of the financial position of the business including whether employee entitlements can be paid. As at January 2015, details of FEG were also included on a number of websites likely to be visited by affected employees, including the Department of Human Services (DHS). The program is referenced in material available on the ASIC website, the Fair Work Ombudsman and the Fair Work Building and Construction Commission. These websites provide summary information and direct employees to the Department of Employment’s website or FEG hotline for further information.