Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of Deductible Gift Recipients (Non-profit Sector)

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the ATO’s administration of DGR endorsements and associated arrangements.

Summary

Introduction

The non-profit sector

1. The Government recognises that ‘the non-profit sector is a key partner in delivering major social policy reforms and in creating opportunities for Australians to participate in work, engage in lifelong learning and live with dignity and respect. The non-profit sector also enriches communities through sport and recreation, arts and culture, and through protecting the environment and providing emergency services in times of crisis.’[1]

2. The non-profit sector (also known as the third sector) is made up of a diverse range of entities. It includes unincorporated bodies operating on a voluntary basis outside the market economy such as baby-sitting clubs, and small incorporated bodies such as school parents and citizens associations. The sector also includes professional and trade union associations, special interest groups and clubs. A number of large organisations, which may or may not be religiously aligned, have taken on national roles across a range of activities such as delivering shelter for the homeless, aged care facilities and assistance for the long-term unemployed as well as international aid programs.

3. The non-profit sector makes a significant contribution to the Australian economy. There are an estimated 600 000 non-profit sector bodies that employ 889 000 employees and engage some 4.6 million volunteers. They contribute approximately $43 billion to the Australian economy, representing over four per cent of Australia’s Gross Domestic Product.[2] In recognition of the sector’s contribution to Australian communities, especially in supporting the most vulnerable and disadvantaged members of our society, the Government committed to the National Compact: working together, which outlines how the Government and the sector will work together under the National Compact.[3]

ATO responsibilities with respect to the non-profit sector

4. The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) defines a non-profit organisation as one that is not operating for the profit or gain of its individual members, with any profits gained going back into its operation to carry out its purpose. The constitution or governing documents of a non-profit entity must reflect these characteristics.

5. The ATO has administrative responsibility for two areas of legislation, which pertain specifically to the non-profit sector:

- Division 30 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (ITAA 1997) that identifies the gifts and contributions that are income tax deductible to the donor, as well as the requirements for entities to be endorsed as a deductible gift recipient (DGR) in order to receive income tax deductible gifts and contributions; and

- Division 50 of ITAA 1997 that specifies the entities that are exempt from income tax and those that are required to be endorsed by the Commissioner to receive tax concessions as tax concession charities (TCCs).[4]

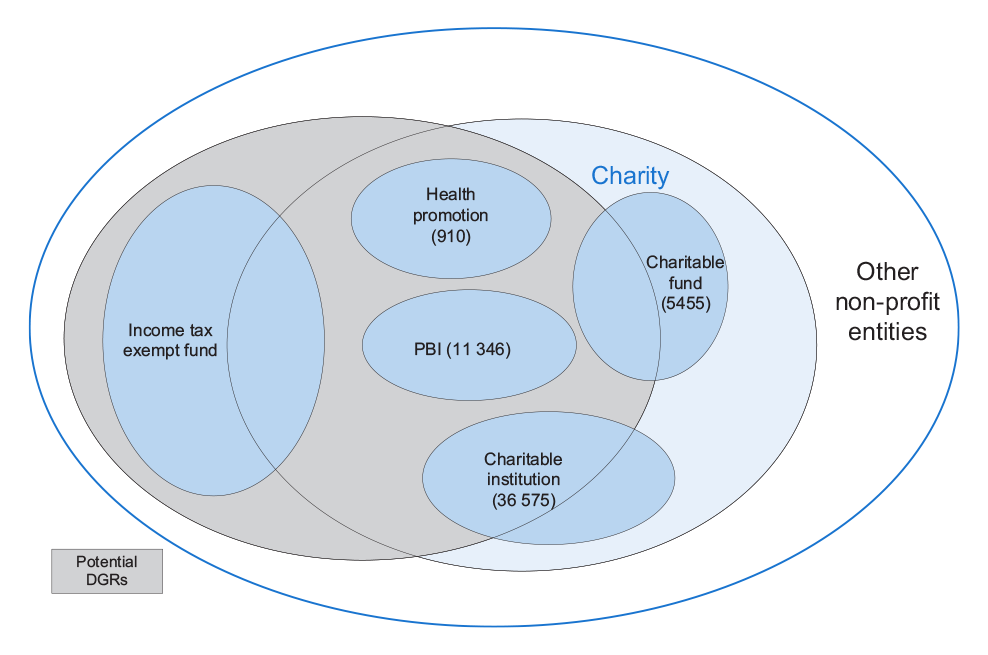

6. In summary, the ATO classifies non-profit entities as follows:

- charities[5]—these include: charitable institutions which are run solely to advance or promote a charitable purpose; public benevolent institutions (PBIs) that have a predominant purpose of the direct relief of poverty, sickness, destitution, suffering or misfortune;

- health promotion charities whose principal activity is promoting the prevention or control of human diseases; and charitable funds, which are trusts established for a charitable purpose; income tax exempt funds—trust funds which donate to DGRs that are not other income tax exempt funds[6]; and

- other non-profit organisations—such as sports clubs, community service groups and recreational clubs.

Deductible gift recipients

7. There are two means by which a non-profit entity can become a DGR and accept gifts and contributions that are income tax deductible for the donor:

- listed by name in the ITAA 1997, which requires a legislative amendment for inclusion.[7] As at 9 June 2010, there were 214 entities named in legislation; or

- endorsed as a DGR by the ATO.

8. As at July 2010, there were 24 290 DGR organisations. The estimated value of tax deductible donations to these entities was $2.1 billion for 2008–09.[8]

9. Division 30 of the ITAA 1997 identifies 49 different categories of non-profit entities that are eligible for DGR endorsement. These categories broadly include health promotion charities, welfare and rights entities as well as cultural organisations.

10. Entities with the potential to be endorsed as DGRs may also overlap with the classifications that the ATO uses to define the non-profit sector. Figure S.1 illustrates this relationship.

Figure S.1: Relationship between potential DGRs and the classes of non-profit entities

Source: Data on the number of entities from the following sources: charitable funds and institutions from Australian Taxation Office, op. cit.; PBIs and health promotion charities from internal ATO document as at 12 July 2010.

Note: Health promotion organisations, public benevolent institutions and charitable institutions may also separately operate charitable and income tax exempt funds.

Arrangements for administrating the ATO’s non-profit clients

11. The Non-Profit Centre (NPC), within the Small and Medium Enterprises business line in the ATO has responsibility for administering tax legislation specific to the non-profit sector. The principal responsibilities of the NPC include:

- providing advice and education to non-profit entities on compliance with specific legislative requirements;

- assessing eligibility for DGR endorsement status and tax concessions, as well as making determinations on behalf of the Commissioner of Taxation; and

- monitoring the ongoing compliance of entities endorsed as DGR and tax concession charities, and of other non-profit organisations self-assessed as income tax exempt.

12. Since 1 July 2000, non-profit entities have been required to apply for DGR endorsement in order to receive income tax deductible donations. Prior to that time organisations self-assessed, but could apply to the ATO for a gift certificate that demonstrated their compliance with legislative requirements. For most categories, entities apply to the ATO for endorsement. A small number of categories require entities to apply initially to other Commonwealth agencies—these applications need to be approved by the responsible Minister and the Assistant Treasurer.[9]

Other government requirements

13. While endorsement as a DGR allows an entity to raise funds that are deductible against income for the donor, the states and the ACT have separate requirements regulating fundraising events, for example the NSW Charitable Fundraising Act 1991 and ACT Charitable Collections Act 2003.[10] The legislation, primarily focused on accountability and consumer protection, varies across jurisdictions as to the type and purpose of the fundraising activities allowed and the organisations regulated.

14. Non-profit entities may also be required to comply with other legislation depending on their organisational structure. For example, companies are registered under the Corporations Act 2001, which is administered by the Australian Securities and Investment Commission, whereas incorporated associations are regulated through state and territory legislation.

Recent developments

15. In 2009, the Productivity Commission undertook a research study into the contributions of the not-for-profit sector. An area for review included the removal of obstacles to maximise the sector’s contributions to society. The Productivity Commission’s report was published in January 2010 and recommended a national one-stop-shop for non-profit sector regulation, including administering the endorsements currently undertaken by the ATO.[11]

16. The Government subsequently announced in the 2011–12 Federal Budget that the Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission would be established from 1 July 2012. The Commission is expected to have sole responsibility for determining charitable, PBI and other not-for-profit sector status for all Commonwealth purposes, as well as providing education and support to the sector and implementing a general reporting framework for charities; and the ATO will retain responsibility for administering tax concessions for the not-for-profit sector, and will provide corporate support for the Commission. Effectively, under this approach, applicants for DGR categories requiring entities to be charities will have their charity status determined by the Commission prior to DGR endorsement assessment by the ATO.

17. The Government also announced in the 2011–12 Budget that it would be undertaking negotiations with the states and territories on national regulation and a new national regulator for the sector, with the aim of minimising reporting and other regulatory requirements through coordinated national arrangements. These consultations are expected to be extended more broadly on the development of a definition of ‘charity’ that could be adopted on a consistent basis across jurisdictions. The Government foreshadowed legislation to introduce a statutory definition of ‘charity’ for all Commonwealth laws from 1 July 2013.

Audit objective and criteria

18. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the ATO’s administration of DGR endorsements and associated arrangements. Particular emphasis was given to the:

- governance arrangements supporting the management of DGR processes;

- DGR endorsement assessment process to achieve consistent outcomes that are timely and in line with legislation;

- communication and coordination of DGR application requirements to assist applicants to achieve DGR endorsement and minimise unnecessary administrative requirements for applicants; and

- compliance approach, which provides assurance that fundraising entities comply with DGR endorsement requirements.

19. The scope of the audit did not include compliance by taxpayers with requirements for claims of gifts and donations as income tax deductions.

Overall conclusion

20. For many taxpayers the focus of their philanthropy is through donations to DGRs, which are subsequently claimed as tax deductions against their gross income. For the 2008–09 financial year some 4.6 million taxpayers claimed deductions for donations to DGRs totalling $2.1 billion, an average claim of approximately $450. While the proportion of taxpayers making such claims has remained largely static, the amount claimed as donations has increased dramatically in recent times. In particular, over the seven years to 2008–09, donations increased in value by an average of 20 per cent per annum. During the same period, the average taxable income increased at a rate of approximately five per cent per annum.[12]

21. There are many aspects of the DGR and related tax concession legislation that are administratively challenging for both the ATO and for fundraising bodies. In particular, there are 49 separate DGR categories that have been progressively introduced into legislation since the mid-1930s. Some categories require public funds to be established under trust arrangements, while others endorse the organisation itself. Further, the specific requirements of these categories are such that organisations may be ineligible for DGR endorsement because their work falls across a number of categories but is not predominate in one particular DGR category. Similarly, certain characteristics of the tax concession legislation create anomalies in the type of endorsement that organisations may apply for because some categories allow access to a broader range of tax concessions. As a consequence, organisations apply for status in categories that may not reflect the activities undertaken by them in an attempt to access the broader tax concessions. It is within this context that the ATO carries out its administrative responsibilities to endorse entities as DGRs.

22. The ATO has implemented appropriate arrangements to effectively administer DGR endorsements and the associated tax concessions. The Non-Profit Centre’s (NPC’s) business planning and internal reporting are well integrated into the ATO’s broader business approach. The NPC also undertakes internal monitoring of its operations and, within the constraints of its resourcing and capabilities, takes action to address required improvements. However, scope exists for the ATO to improve the consistency of its decision-making on DGR endorsement applications and to more effectively monitor compliance by organisations that are endorsed as DGRs.

23. To support consistency in decision-making when assessing DGR endorsement applications, the ATO has implemented a two-stage quality assurance process that reviews results prior to, and following, finalisation of cases. In addition, all disallowed applications are checked by supervisors. However, the rate of disallowed decisions subject to objections which are subsequently overturned suggests that approximately five per cent of all decisions (300 decisions) in the three years to June 2010 were inconsistent. These inconsistencies relate to differences: across the locations of assessment teams; in the relevance of documentation on which the assessment was based; and in the level of scrutiny applied to an application, resulting in a decision at odds with the ATO’s contemporary view on the legislation. The quality assurance process has not been fully effective in identifying these inconsistencies.

24. The ATO faces a number of challenges in assessing the extent to which organisations, once endorsed, comply with the requirements of their DGR status. Over the past two years to June 2010, there have been some 9600 DGR and tax concession charity endorsement applications decided. The volume of applications has meant that the focus of the NPC’s work has been assessing these applications. As a consequence, there were limited resources available to properly assess the compliance risks associated with the sector and to undertake an appropriate level of post-endorsement compliance reviews and audits. The NPC’s compliance work is further limited by a lack of quantitative data. The sources of information held on DGRs within the ATO and by other government agencies are not collated and interrogated to identify organisations at risk of non-compliance that warrant further investigation.

25. The inadvertent non-compliance with legislative requirements by fundraising organisations is recognised by the ATO as being a high risk, particularly given that many of these organisations are managed by volunteer committees that experience regular turnover. The management of this risk is not commensurate with its assessed level of potential non-compliance. There are also ongoing concerns in the ATO that a proportion of DGRs registered at the time of the introduction of DGR endorsement requirements, if subjected to the scrutiny currently given to applications, would not be endorsed. In the 18 months to the end of 2000–01, approximately 21 000 applications were decided, seven times the current submission rate. Of these, only 17 per cent were disallowed or withdrawn, compared with double that rate that are disallowed or withdrawn under a business-as-usual approach.

26. There is no requirement for most DGRs to report regularly to the ATO—an exception is the 800 DGRs in the category ‘private ancillary funds’.[13] As a result, the ATO is not in a position to determine whether the DGRs continue to offer those services on which their endorsements were based. It is also noted that there are currently at least 3500 fundraising bodies registered with state and ACT governments that are not DGRs. Information expected to be reported to the future Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission and outcomes from planned negotiations with the states and territories on coordinated national reporting requirements, may assist in assessing compliance risks in the future.

27. With Government initiatives underway directed at reform in the not-for-profit sector, it is timely for the ATO to review its existing administrative arrangements. To this end, the ANAO has made two recommendations to improve the compliance with the legislative requirements relating to DGR administration.

Key findings by chapter

Governance arrangements (Chapter 2)

28. The NPC’s oversight, planning, reporting and monitoring arrangements enable its operations to be well integrated into the ATO’s broader business approach. It has formal arrangements with other areas of the ATO that also have non-profit clients, such as those with responsibility for debt, lodgment, excise and superannuation. These arrangements facilitate a whole-of-ATO approach to managing the strategic risks that may arise within the market segment. Consistent with this integration, the NPC’s work contributes to the overall external reporting by the ATO in its annual report on its performance against client service standards. However, the performance of NPC operations is aggregated with that of other areas of the ATO. While noting that the NPC’s work forms a small part of ATO operations, the lack of performance reporting specifically on non-profit sector activities limits the accountability and transparency of the ATO’s performance in this area.

29. The NPC comprises approximately 60 FTE working in five functional teams[14] that cover the key legislative responsibilities particular to the non-profit sector—each contributes to DGR administration. The NPC has a range of strategies in place to coordinate its operations across the six locations of its five teams. While these strategies have been successful in managing the NPC as a whole and integrating the work of the Risk and Intelligence and Active Compliance teams, they have been less successful in ensuring a national practice across one of the teams, the Interpretative Assistance team, which is spread over four locations.

30. With respect to resourcing, staff turnover has meant that there has been a loss of expertise in the small number of non-profit tax legislation specialists working in each location. Further, the introduction of the client contact – work management – client management (CWC) IT system in August 2009 has meant additional resources are now required to assess endorsement applications because more details must be entered into the new system. Both factors have led to a decrease in performance against timeliness standards.

31. Endorsement assessment workloads are demand driven, and the NPC has introduced changes to assist productivity and also increased staff resourcing to address timeliness concerns. However, a lack of management and performance information to monitor the number of complex, high-risk cases, the impact on processing efficiency from high individual case loads, and the ongoing effects from the CWC system, limits the ability of the NPC to assess the effectiveness of the changes and to determine adequate resource levels against demand.

32. The NPC places an emphasis on consultation and communication with the sector. Its primary formal community consultative forum, the Charities Consultative Committee, largely comprises Christian churches or associated community services arms, and key peak bodies whose members have access to relevant tax concessions.[15] Some groups with an interest in charitable fundraising are under-represented in this forum. These include professional advisers that assist organisations with DGR endorsements such as specialist charity lawyers, and those whose community work falls outside the major charity focus. There is no regular, two-way communication between the ATO and such groups to discuss matters relating to DGR endorsement.

Assessing DGR endorsement applications (Chapter 3)

33. The key risks in processing applications relate to timeliness and consistency in applying the ATO’s view on the legislation.

Timeliness of decision-making

34. For applications where all the necessary information required for decision-making has been provided, the timeliness standard for processing applications is 28 days elapsed time. On average, the elapsed time to process DGR applications in 2009–10 was 36.7 days. While this result arises in part from the NPC not meeting the timeliness standards, many applications do not initially include all the information needed by the ATO to make a decision. Some are delayed in other areas of the ATO, prior to receipt by the NPC.

35. The NPC has implemented initiatives to improve its processing of applications. These include:

classifying applications according to risks and the consequential level of scrutiny required[16]; writing up assessments against each disallowed criterion to minimise re-submissions that are likely to fail; and encouraging applicants who are likely to be disallowed for DGR endorsement to withdraw their applications, eliminating the requirement for decision write-ups.

36. A recent business case seeking extra resources to undertake assessments has been successful in securing more staff, providing the potential for improved timeliness. In addition, an interactive, online application form could assist the timeliness of processing by eliminating delays in allocating applications to the NPC from other areas of the ATO. A project outline for such a form has been developed, but as yet the ATO has not identified a timeframe for its implementation.

Consistency of assessment decisions

37. There are a number of mechanisms in place for promoting consistency in decision-making in the assessment of DGR endorsement applications. These include: standard training packages; documentation on processing and eligibility criteria; processes to escalate eligibility issues through team leaders; internal communication processes; and quality assurance procedures. Nonetheless, of the eleven law firms involved in assisting DGR applicants that were interviewed by the ANAO, nine raised concerns regarding the consistency of decision-making. The ANAO reviewed 55 selected DGR cases to assess whether decisions were consistent with the guidance material available at the time. This analysis identified inconsistencies in the decision-making on DGR endorsement for the categories relating to: volunteer fire brigades; school building funds; and school library gift funds operated by school foundations or parents and citizens associations. In addition, over 12 per cent of disallowed decisions are subject to an objection with more than 40 per cent of these resulting in the original decision being overturned.

38. Inconsistencies were also identified in the processing of similar cases in different locations, suggesting that the current processes for ensuring a national practice in application processing has not been fully effective. A factor contributing to a perception of inconsistency is a delay by the ATO in providing advice to staff on the impact of a recent High Court decision on DGR endorsement decisions. Updated tax rulings have not been finalised, some two years after the decision was handed down.[17]

Quality assurance arrangements for assessments

39. Quality assurance processes are undertaken on decisions prior to, and following, finalisation of applications. The pre-finalisation assessor is chosen by the case officer and is typically a team member within the same office as the original decision-maker. In the 12 months to October 2010, no inconsistent or incorrect cases were identified through the pre-finalisation quality assurance process, suggesting, in the light of inconsistencies previously discussed, limited independent review by the quality assessor.

40. The post-finalisation quality assessment process also has shortcomings as a remedy for inconsistent or incorrect decision-making, particularly when ATO decisions may have been actioned by non-profit bodies. While the post-finalisation assessment is independent of the original decision-maker, it has covered only one per cent of DGR endorsement decisions over the past two years. In the two years to October 2010, these assessments have determined that there is an error rate of five per cent in DGR endorsement decisions. However, given the small sample on which this was based, the estimated error rate across all DGR endorsement decisions is up to 12 per cent at the 95 per cent confidence level. The current quality assurance processes could be more effective in identifying potentially inconsistent decisions.

Communicating and coordinating DGR application requirements (Chapter 4)

41. A range of general advice is available to potential DGR applicants through ATO publications and via the telephone. There are, however, limitations on the availability of timely advice and information available to organisations that is specific to their circumstances. Almost one in three DGR endorsement applications was disallowed, mainly because applicants did not: fully understand the requirements of specific DGR categories, nor provide required documentation supporting their application.

42. Initiatives are underway to determine the effectiveness of guidance material and, as a preparatory step to the development of an online, interactive form, to identify the eligibility requirements through a step-by-step guidance map.

43. There is coordination between the ATO and other Commonwealth agencies responsible for assessing applications for DGR endorsement to enable applicants to only submit their application once. Currently, there is no single agency with accountability for the whole assessment process across agencies. Applications requiring assessment by Commonwealth agencies other than the ATO take up to two years to determine. While this length of time potentially discourages applications for these categories, there is no means to measure the impact on clients of processes involving multiple agencies.

Managing DGR compliance (Chapter 5)

44. Compliance activity related to DGR endorsement is focused on determining eligibility through the assessment of applications for DGR endorsement. Two other elements important for compliance activity relate to:

- fundraising activities promoted explicitly or implicitly as income tax deductible are only undertaken by DGR entities; and

- endorsed DGR entities continue to comply with the eligibility requirements that resulted in their original endorsement.

45. In both of these areas, the onus is on the non-profit entities to understand and comply with requirements. The NPC’s primary approach to managing the risk of non-compliance is through marketing and communications activities. These activities can include information products, community engagement through the Charities Consultative Committee and mail-outs of compliance information to DGR endorsed non-profit entities. In addition, with respect to those DGRs already endorsed, entities are encouraged to self-assess their continued eligibility on an annual basis and are required to advise the ATO of any changes that would impact on their eligibility.

46. Complementing these risk management processes, the NPC has a structured approach to risk identification and management that includes follow-up directly with organisations. Risk identification, its assessment, and the development of an overall risk strategy for the non-profit sector is undertaken by a dedicated Risk and Intelligence team. The NPC Active Compliance team works with the Risk and Intelligence team to directly contact organisations to further refine the scope and level of particular risks. The Active Compliance team conducts audits and other campaigns on high-risk entities that have been identified as being non-compliant either by being referred by the Risk and Intelligence team or as part of a project in line with the risk strategy plan for each year.

47. The NPC’s work in this area has been limited by resource constraints. The ATO has 1.5 FTEs assigned to the Risk and Intelligence team, and seven FTE staff to the NPC Active Compliance team. Allocation of additional general compliance staff is on an ad hoc basis. The NPC’s compliance work is further limited by a lack of quantitative data. The sources of information held on fundraising organisations (including endorsed entities) within the ATO and by other government agencies are not collated and interrogated to identify organisations at risk of non-compliance. The ATO advised that it is planning to develop a risk rating engine for the non-profit sector in 2010–11,[18] providing the potential to assist selection of cases for compliance activity.

48. There is no requirement for most DGRs to report regularly to the ATO, nor for taxpayers to identify recipients of their donations in tax returns. As a result the ATO has very limited internal information on which to assess the risk that income tax deductibility is only promoted in respect of fundraising activities associated with DGRs or, more broadly, that taxpayers are claiming for donations that are not made to DGRs. The potential for such risks materialising is illustrated by the ANAO’s identification of some 3500 organisations that may be undertaking fundraising activities under state/territory legislation but are not DGRs. Currently, the ATO does not seek or analyse this information to determine the extent to which fund-raising bodies are non-compliant with DGR requirements. The information expected to be reported to the new Australian Charities and Not-for-profits Commission and the outcomes from planned negotiations with state and territories on national reporting requirements may provide an indication of the scale of this risk.

49. Limited resources and quantitative tools have resulted in risk and intelligence assessments being broadly based on qualitative information from media reports, individuals and other entities, and analysed on an ‘intuitive basis’. It has also limited the number of direct assessments able to be conducted by the Active Compliance teams. In particular, during 2009–10, the ATO completed four audits and 38 other reviews involving 40 DGRs (from the population of some 24 000 DGRs). The outcome of this compliance activity was that 13 DGRs (32 per cent) had their DGR endorsement revoked.

50. The level of resources assigned to risk assessment and active compliance is not commensurate with the ATO’s determination that the risk of non-compliance by DGRs is high. The ATO’s findings estimate that only a third of DGRs currently undertake regular self-assessment. Further, the length of time that organisations have been endorsed increases the risk of non-compliance. Many DGRs gained endorsement based on limited assessment at the introduction of DGR endorsements in 2000. Since that time, the ATO has evolved its interpretation of tax legislation in this area, without a commensurate review of whether previous DGR endorsements still align with the ATO’s current view. The Government has foreshadowed legislation to introduce a statutory definition of ‘charity’ for all Commonwealth laws from 1 July 2013, with proposed funding to the Commission to re-assess the charitable status of entities on the basis of the new definition.

Summary of agency response

51. The Tax Office’s summary response to the report is reproduced below. The full response is at Appendix 1.

The ATO welcomes the ANAO audit report on Administration of Deductible Gift Recipients (Non-profit Sector).

While the report makes two recommendations about how the ATO can improve its administration of deductible gift recipients (DGRs) it also notes that:

“The ATO has implemented appropriate arrangements to effectively administer DGR endorsements and associated tax concessions.”

The ATO agrees with both recommendations made in the report and will work to implement them as part of the required structural changes in the ATO in preparation for the commencement of an Australian Charities and Not-for-profit Commissions (ACNC) from July 2012. Where necessary, the ATO will implement the recommendations in consultation with the commissioner-designate of the ACNC to ensure the best outcomes for the community.

Footnotes

[1] Julia Gillard (2010): Strengthening the Non-profit Sector, August 2010. <http://www.alp.org.au/federal-government/news/strengthening-the-non-profit-sector/> [accessed 24 August 2010].

[2] Data drawn from: Productivity Commission Research Report (January 2010), Contribution of the Not-for-Profit Sector, p. xxvi. <http://www.pc.gov.au/projects/study/not-for-profit/report> and Australian Bureau of Statistics (2009), 2006-07 Australian National Accounts: Non-Profit Institutions – Satellite Account, (Publication 5256.0). <http://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/Ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/661F486077ACD72BC A2576340019C6C8/$File/52560_2006-07.pdf> [accessed 6 August 2010].

[3] The National Compact sets out: shared principles; shared aspirations on the relationship between the parties, on the achievement of better results and for a more sustainable non-profit sector; and priorities in the development of joint action plans, including for the reduction of red tape and streamlined reporting. Commonwealth of Australia (2010), National Compact: working together. <http://www.nationalcompact.gov.au/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/Nat_compact.pdf> [accessed 12 November 2010].

[4] There is related legislation pertaining to GST concessions, FBT exemptions and rebates, and refunds of franking credits for non-profit entities, that draws on the requirements in Divisions 30 and 50 of ITAA 1997.

[5] Charities can apply to be endorsed as TCCs.

[6] Income tax exempt funds are also known as ‘ancillary funds’.

[7] Amendments to this legislation are brought forward to Government by Treasury in consultation with the ATO.

[8] Australian Taxation Office (2011), Taxation Statistics 2008–09. (NAT 1001-03.2011), p. 17. <http://www.ato.gov.au/content/downloads/cor00268761_2009TAXSTATS.pdf> [accessed 7 April 2011]. At the time of preparing this report, 2009–10 figures were not available. However, the value of revenue foregone from donors’ tax deductions in 2009–10 is estimated at $1.1 billion, a decrease of 12 per cent compared with the previous year. (Department of the Treasury (2011), Tax Expenditures Statement 2010. <http://www.treasury.gov.au/documents/1950/PDF/2010_TES_consolidated.pdf> [accessed 31 January 2011].)

[9] These categories include: environmental organisations; cultural organisations; harm prevention charities; and overseas aid funds.

[10] The Northern Territory Government does not have legislation regulating this function.

[11] Productivity Commission, op. cit.

[12] Australian Taxation Office (2011), op. cit., pp. 13, 17, and Australian Taxation Office (2004), Taxation Statistics 2001–02. <http://www.ato.gov.au/content/downloads/2002PER1.pdf> [accessed 5 April 2011].

[13] Private ancillary funds are trust funds established by individuals, families and businesses that donate to other DGRs that are not ancillary funds.

[14] The teams are: Interpretative Assistance, Risk and Intelligence/Communications, Active Compliance, Technical Advice and Government Liaison.

[15] Current community membership comprises: Anglicare, Australian Catholic Bishops Conference, Mission Australia, Salvation Army, UnitingCare Australia, Australian Council of Social Services, Community Housing Federation, Independent Schools Association, St John’s Ambulance Australia, and Queensland University of Technology—Centre of Philanthropy and Non-Profit Studies.

[16] The classifications, ‘fast-tracked’, ‘verified’, and ‘fully examined’, are subject to increasing levels of scrutiny.

[17] The judgment on the case, Commissioner of Taxation vs Word Investments Ltd, effectively broadened the scope of a charity to include commercial enterprises whose profits are ultimately applied for a charitable purpose, overturning two tax rulings, TR 2005/21 and TR 2005/22, on which the ATO had based its determination. In May 2011, the Commissioner of Taxation withdrew TR 2005/21, and released for public comment the draft tax ruling TR 2011/D2 that seeks to replace TR 2005/21. In the 2011–12 Federal Budget the Government foreshadowed legislative changes to limit access to tax concessions by non-profit entities with unrelated commercial activities, which when implemented may change some areas of the law covered by the draft ruling and TR 2005/22. Australian Government, 2011, Budget Paper No. 2 Budget Measures 2011–12, p 36. <http://cache.treasury.gov.au/budget/2011-12/content/download/bp2.pdf> [accessed 18 May 2011].

[18] A risk rating engine is generally the primary tool used in other areas of the ATO to identify high-risk non-compliance targets.