Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of Communities for Children under the Family Support Program

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of FaHCSIA’s administration of Communities for Children under the Family Support Program.

Summary

Introduction

1. In Australia, statutory child protection is the responsibility of state and territory governments.1 Under these arrangements, children and families generally come into contact with the child protection system in an emergency or crisis situation through the reporting of suspected neglect or abuse. Statistics produced by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare2 (AIHW) show that the demand for child protection services in Australia has been steadily increasing, putting pressure on the state and territory statutory systems.3 Further, research by the AIHW indicates that engagement with the child protection system, particularly with out‑of‑home care, does not protect children from poor long‑term outcomes.4

2. With the goal of achieving better long term outcomes for children who are at risk of abuse and neglect, the Australian Government, in partnership with the state and territory governments and the not‑for‑profit sector, is now moving towards a public health model to protect these children. This involves shifting the emphasis to prevention and early intervention rather than focusing efforts on statutory interventions. In 2009, the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) endorsed Protecting Children is Everyone’s Business: The National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children 2009‒2020 (the National Framework). The National Framework represents a long‑term, nationally coordinated effort by the Australian Government, state and territory governments and the not‑for‑profit sector to protect the safety and wellbeing of Australia’s children.5

3. Communities for Children (CfC) was originally established in 2004 following a decision by the then Australian Government to establish the Stronger Families and Communities Strategy (2004–08). CfC was one of four streams of the Stronger Families and Communities Strategy, with an allocation of $110 million for 35 disadvantaged communities over four years. The aim of CfC was to address the risk factors for child abuse and neglect before they escalate, and help parents of children at risk to provide a safe, happy and healthy life for their children.

4. A key feature of the original CfC was that a lead non government organisation (NGO) would be responsible for working with the local community, including other community organisations, to develop a child friendly community plan. Funding for an initial seven CfC sites was provided under the Stronger Families and Communities Strategy in 2004. Further sites were added in 2005 and 2006, and again in 2009. The strategy sought to engage adults in activities with and for their children, and included home visiting, early learning and literacy programs, early development of social and communication skills, parenting and family support programs, and child nutrition.

5. In 2008, the Australian Government commenced a strategy of widespread reform of children, families and communities grant programs to more comprehensively support families and build socially inclusive communities. The rationalisation and restructuring of community support programs into a better targeted and more integrated strategy, aimed to improve the focus on government priorities, increase flexibility in the application of government funds at a local level, and reduce program duplication and administrative costs. The Minister for Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs announced the creation of the Family Support Program (FSP) in February 2009, and signalled the commencement of a two year transition phase to undertake the reforms.

6. On 1 July 2009, CfC became an activity6 under the FSP, as one of a suite of activities aimed at supporting the wellbeing of children and families; ensuring children are protected; and contributing to building stronger, more resilient communities. The original model of service delivery, of a lead NGO working within the community to develop community responsive services, was transferred into the FSP as the CfC Facilitating Partner model. Within this model, the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) provides grant funding to NGOs in targeted locations across Australia to develop local, community‑based networks that build on existing community resources, and develop strategies to address acknowledged service gaps. These NGOs are referred to as Facilitating Partners, and are assigned an Activity Delivery Area7 in which they operate. Facilitating Partners build networks of smaller and/or specialised service providers (known as Community Partners) and subcontract them to develop and/or deliver services to meet existing and emerging local priorities. A committee of local community representatives is the key decision‑making mechanism that meets to identify community resources, service needs, and gaps in service delivery.

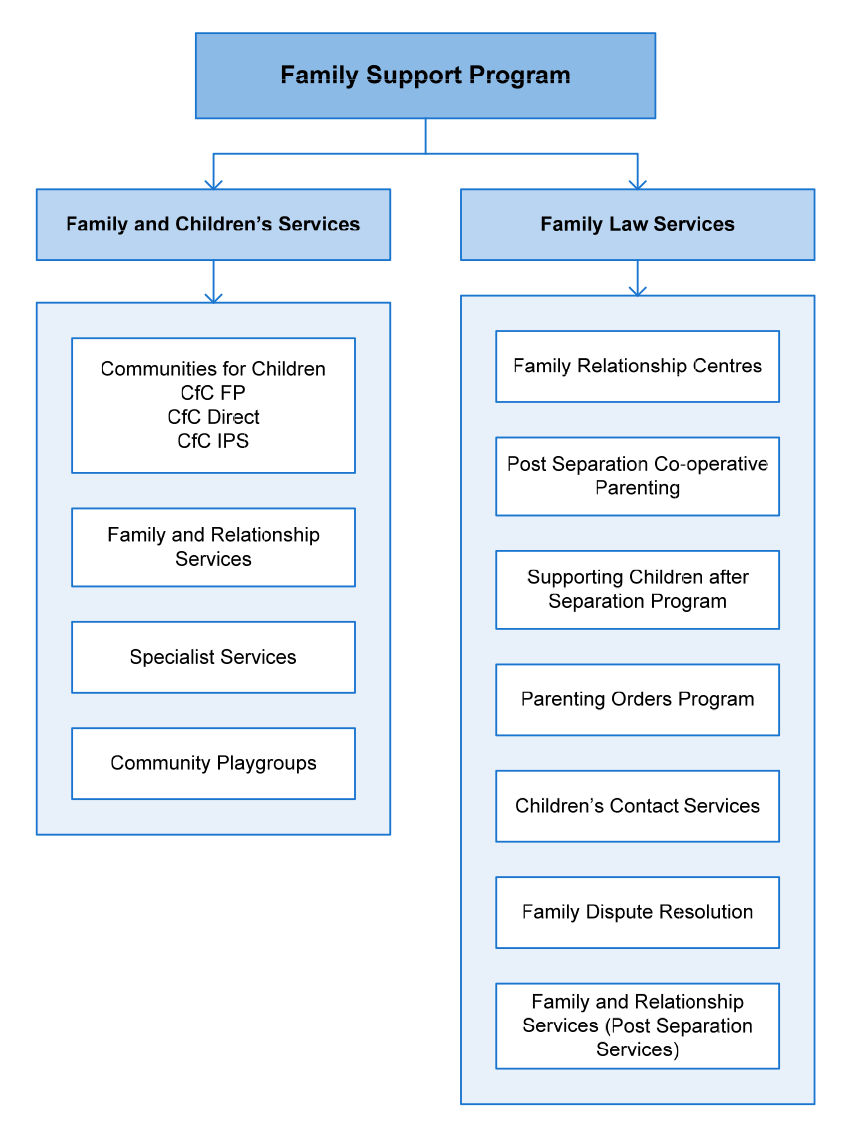

7. During 2011, FaHCSIA further restructured and streamlined the FSP, resulting in the addition to the FSP of services that were being delivered under other programs, and reduced the three FSP streams into two. The current structure is shown in Figure S1. As part of this process a large number of children and parenting programs were incorporated into CfC, and existing service providers were transitioned to the new service arrangements following an assessment of their performance, and ability to meet the new program requirements. This significantly increased CfC funding and expanded the service delivery types to three service delivery arrangements—CfC Facilitating Partner (CfC FP), CfC Direct Services (CfC Direct), and CfC Indigenous Parenting Services (CfC IPS).8 As at October 2012 there were 370 CfC service activities funded by FaHCSIA, including 52 CfC FP sites.

Figure S1 Revised structure of the Family Support Program from 1 July 2011

Source: ANAO adaptation of diagram from the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, Family Support Program Guidelines Part A, FaHCSIA, Canberra, 2012, p. 6.

Note: These two streams are also supported by national services, including the Family Relationships Advice Line, Family Relationships Online and the Raising Children Network.

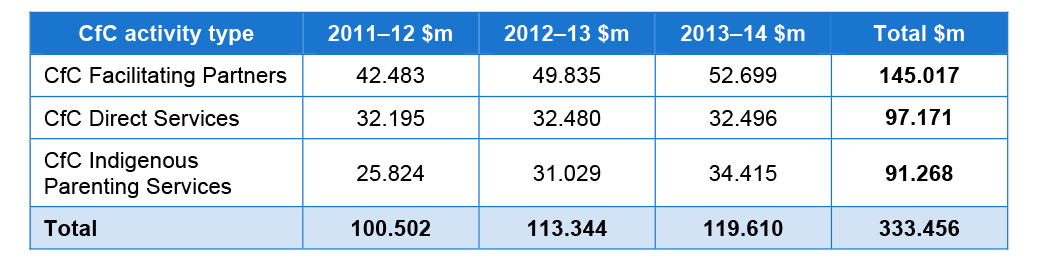

8. The Australian Government allocated a total of $333.456 million to CfC for the three years commencing 2011–12. The distribution of funding is shown in Table S1.

Table S1 Communities for Children funding 2011–2014

Source: FaHCSIA financial information. This table reflects the expected allocations by financial year.

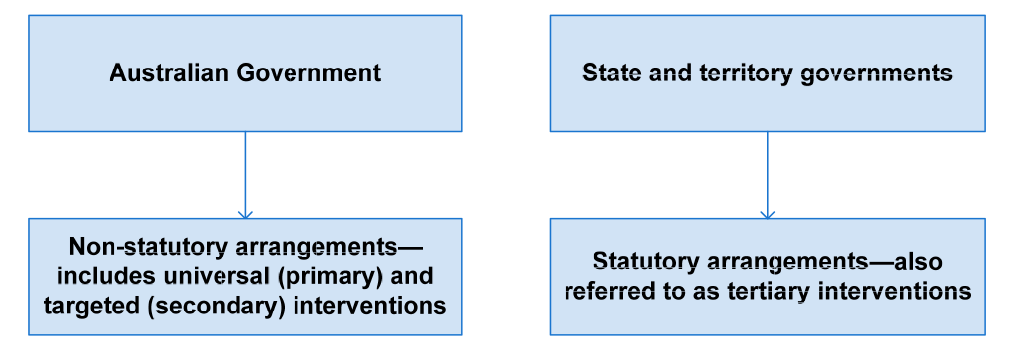

9. As noted in paragraph 1, state and territory governments are responsible for statutory, also known as tertiary, intervention in child protection, while the Australian Government implements non‑statutory arrangements. These include:

- universal (primary) interventions—strategies that target whole communities to build public resources to address social factors that contribute to child neglect and abuse; and

- targeted (secondary) interventions—strategies that target vulnerable families or children and young people who are at risk of child neglect and abuse.

The child protection responsibilities of the Australian, and state and territory governments for child protection are shown in Figure S2.

Figure S2 Government responsibilities for child protection in Australia

Source: ANAO, adapted from information from Australian Research Alliance for Children & Youth, Working together to prevent child abuse and neglect—a common approach for identifying and responding early to indicators of need, ARACY, Canberra, 2010, p. 12.

10. An important design feature of CfC is its relationship to the statutory child protection system and, in particular, the opportunities it provides to help alleviate the pressure on that system from growing demand for statutory child protection services. Child Protection Australia, a report produced annually by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), provides a comprehensive national analysis of child protection statistics. This report compiles detailed statistical information including the characteristics of children receiving child protection services, trends over time, and factors possibly contributing to changes in statistics. The key descriptors reported are:

- the number of children subject to a notification9;

- the number of children subject to a substantiation10; and

- the number of children on care and protection orders and in out‑of‑home care.11

11. Substantiations of notifications are classified nationally into one of the following four categories: physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse or neglect. In the Child Protection Australia 2010–11 report the most common type of substantiated notification nationally was emotional abuse (36 per cent), followed by neglect (29 per cent), physical (21 per cent), and sexual (14 per cent).

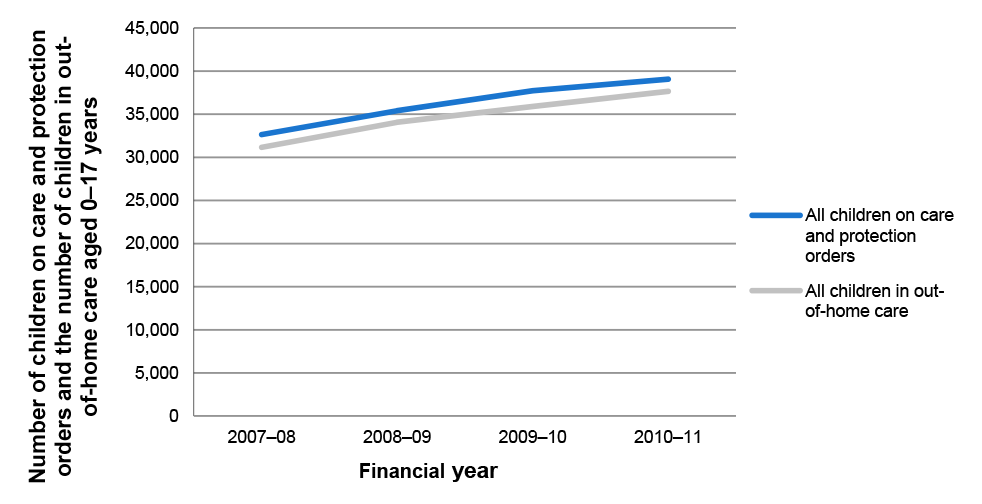

12. Overall, the Child Protection Australia reports show that the demand for child protection services in Australia has been steadily increasing. Figure S3 illustrates the increase in the numbers of children on care and protection orders, and the number of children in out‑of‑home care, from 2007–08 to 2010–11.12 While the rate of increase may reflect changes in state and territory policies and processes, increasing community awareness of child neglect and abuse, and broadened definitions of child neglect and abuse, on balance, the trend is that the number of children in child protection systems across Australia is increasing.

Figure S3 All children on care and protection orders or in out‑of‑home care, aged from birth to 17 years, from 2007–08 to 2010–11 at 30 June each year

Source: ANAO analysis from Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) reports Child Protection Australia 2007–08, Child Protection Australia 2008–09, Child Protection Australia 2009–10 and Child Protection Australia 2010–11.

13. The rise in the number of children on care and protection orders and in out‑of‑home care has significantly increased demand on child protection agencies, and more broadly on government resources. Further, some research indicates that engagement with child protection systems, particularly with out of home care, does not protect children from poor long term outcomes.13 The November 2012, AIHW publication, Children and young people at risk of social exclusion: links between homelessness, child protection and juvenile justice14, reports strong evidence that children who suffer abuse or neglect are more likely to engage in future criminal activity, and be over represented among the homeless.

14. The report proposes several possible reasons for the links between child maltreatment, criminal activity and homelessness. Children who are mistreated typically have parents or guardians who are unable to provide adequate supervision, usually due to economic or social stress. The lack of adequate supervision increases the child’s likelihood to become involved in delinquent activities. Further, children who have come into contact with the child protection system are more likely to be homeless, and often have low levels of education and employment leading to survival crimes such as theft.15

15. Addressing the incidence of child neglect and abuse, and the subsequent life trajectory has, therefore, significant social and economic implications. As a result, the focus of CfC is on mainstream intervention and prevention services. These services are targeted in communities identified as suffering economic stress nationally. This is to contribute to a potential reduction in the numbers of children coming into formal contact with the statutory system and requiring tertiary interventions.

16. Reducing the likelihood of child neglect and abuse through a preventative approach represents a significant challenge. The range of factors that contribute to child abuse and neglect is broad and the numbers of children in care, and on protection orders has been increasing. Further, while child protection statistics report the number of children who come into contact with statutory authorities or child protection services, it is often regarded as a conservative estimate of the occurrence of child maltreatment. The Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS) reports that child neglect and abuse often goes undetected due to the private nature of the crime, the difficulties children experience in making disclosures and being believed, and the lack of evidence to substantiate the occurrence.16

Audit objective, scope and criteria

17. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of FaHCSIA’s administration of Communities for Children under the Family Support Program.

18. The audit focuses on the period from 1 July 2009. This period encompasses the:

- finalisation of the first three year Implementation Plan (2009‒12) of the National Framework;

- restructuring of the Family Support Program; and

- implementation of revised funding and performance management frameworks for service providers to better target vulnerable and disadvantaged children and families.

19. The three high level criteria used to assess FaHCSIA’s performance against the objective were:

- governance and planning arrangements were clearly defined and allowed for close alignment of program activities to program objectives;

- management of service providers was active and balanced accountability requirements with an outcomes focus; and

- the performance management framework enabled the department to effectively monitor program progress, the ongoing performance of providers, and make adjustments to service delivery as required.

Overall conclusion

20. Under the National Framework, the Australian Government, in partnership with the state and territory governments and the not‑for‑profit sector, committed to a coordinated and cooperative approach in order to break the cycle of disadvantage, and work towards prevention and early intervention to reduce the incidence of child abuse and neglect. Communities for Children (CfC), one of several initiatives funded under the Australian Government’s Family Support Program, seeks to contribute to this goal by using community based services to target the most vulnerable and disadvantaged members in society, with the goal of reducing risk factors and improving family functioning and wellbeing. CfC services initially commenced in 2004, working in 35 disadvantaged communities across Australia. As at October 2012, there were 370 CfC services working across 52 disadvantaged locations in all Australian states and territories, with the exception of the Australian Capital Territory.

21. Reducing the likelihood of child abuse and neglect through a preventative approach represents a significant challenge. To maximise their effectiveness, government programs need to be well targeted, have the ability to be tailored to particular community needs and situations, and be well aligned with the overall policy objectives set by government. Since 2009, FaHCSIA has implemented a range of reforms to family and community related programs, designed to reduce fragmentation and better align existing activities to the goals of the National Framework.

22. FaHCSIA’s management of the implementation of program reforms has been active, and effective improvements have been made. Management of CfC has now been incorporated into the management of the umbrella Family Support Program, which has facilitated alignment between CfC and the goals of the National Framework, and also provided a platform for consistent management of activities. FaHCSIA has also implemented a range of initiatives to simplify funding agreement management and reduce unnecessary requirements, although there is further work to consolidate these changes. Planning arrangements are generally well developed in respect of the CfC Facilitating Partner (CfC FP) model. However, as a result of program reforms which saw the addition of a large range of other similar services into CfC in 2011, further work is required to develop more integrated planning approaches that, reflecting the benefits of collaborative service delivery that underpin the CFC FP model, consider the types of services funded across all CfC streams and confirm the appropriateness of the current distribution of CfC activities.

23. Monitoring and reporting arrangements have been established which provide FaHCSIA with information about the implementation of activities on the ground. These arrangements could usefully be augmented by making greater use of site visits to the various community delivery sites. Further, while these arrangements allow for monitoring of providers who are directly contracted to FaHCSIA, they do not allow for a similar level of visibility over the activities of the community organisations who are subcontracted by the lead non government organisations (NGOs) in the Facilitating Partner model, as the responsibility for providing funding and monitoring performance has been given to the Facilitating Partner on behalf of FaHCSIA. The performance information collected from service providers places FaHCSIA in a good position to monitor the performance of service providers. However, more limited use is made of this information to contribute to continuous improvement of service delivery by providers, for example through sharing better practice insights with providers. Performance information is also collected from providers in relation to service delivery outcomes for people using the services which, in conjunction with established evaluation arrangements, will facilitate better understanding of the impact of CfC in communities.

24. The ANAO has made one recommendation directed towards improved planning and targeting of all CfC service delivery. Aspects of FaHCSIA’s grant administration could also be improved. No recommendation on grants administration has been made in this report as FaHCSIA has been included in relevant recommendations made in ANAO Audit Report No. 21 2011–12 Administration of Grant Reporting Obligations.

Key findings by chapter

Program management arrangements (Chapter 2)

25. There are known to be linkages between child maltreatment and levels of economic and social stress which, in turn, are generally prevalent in areas of relative disadvantage. Accordingly, to guide initial planning, and select locations for CfC, FaHCSIA made use of available data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), in particular the Socio Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), to identify areas of relative disadvantage. Similarly, this data was used in subsequent reviews of service locations and complemented by the use of other administrative data held by FaHCSIA, and information from service providers to confirm the alignment of the Activity Delivery Areas (ADA) with the target population. FaHCSIA sought to define the boundaries of ADAs so as to cover a population of at least 40 000 people in each ADA and where 10 per cent of this target population was made up of children under five years of age. As at October 2012 there were 52 ADAs. The majority of these included areas ranked as having the highest relative disadvantage compared to the rest of Australia.

26. To promote a more collaborative and integrated approach to service delivery, FaHCSIA has made use of a place based model of service delivery where a lead organisation, the Facilitating Partner, is engaged to design and oversee the delivery of location specific services in ADAs. A community committee structure enables the Facilitating Partner to interact with community stakeholders in the design and delivery of services which are delivered through subcontracted community organisations. This model aims to facilitate greater local level collaboration and integration so as to provide more inclusive services for target groups identified as vulnerable and disadvantaged.

27. Following reforms made by the Australian Government in 2011 to a range of community focused programs, two additional sets of existing services were added to the CfC program. This had the effect of tripling the funding provided under CfC and the development of two additional service delivery streams, CfC Direct Services (CfC Direct) and CfC Indigenous Parenting Services (CfC IPS), alongside the original CfC FP model. FaHCSIA’s approach to the planning and distribution of these additional services is not integrated into the place based model that underpins the CfC program, with the result that there are some ADAs where all three streams of CfC operate but with limited interaction between each other. Now that services have been brought under CfC, developing a more comprehensive approach to planning for CfC services will be a further important administrative reform for FaHCSIA to undertake in the lead up to the new phase of CfC funding which is planned to take effect from July 2014.

28. Community based grant activities generally involve a high number of delivery partners and are usually dispersed widely. There is growing recognition that integrating the management of a large number of relatively small activities can facilitate a more coordinated approach to service delivery, as well as support more consistent administration. In this respect, FaHCSIA has brought the administration of CfC under the management arrangements of the broader FSP and has allocated responsibilities, such as program design, operations or reporting, to specialised areas which undertake their roles across all parts of the FSP, rather than having a single area maintain responsibility for the complete delivery of CfC activities. This has enabled FaHCSIA to manage a range of activities more consistently, however, the management structure, in which individual sections manage different components of program delivery has led to some segmentation of knowledge within National Office.

Communities for Children service delivery (Chapter 3)

29. As part of broader program reforms initiated by the Australian Government, CfC activities were transitioned from being standalone activities to be part of a more integrated program, the Family Support Program, in 2009. The transition of CfC activities was a key activity to be undertaken by FaHCSIA as one of the Australian Government’s implementation commitments under the National Framework, agreed by the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) in 2009. The incorporation of CfC into the FSP was the first phase of a process of consolidating a large number of discrete grant programs to improve their targeting of client groups and streamline administration. A second phase of reform involving CfC occurred in 2011, when services funded under 18 different grant programs were integrated into CfC. Maintaining a level of stability amongst service providers during the two phases of reform was an important consideration for the Australian Government, and approval was given in both phases to negotiate new funding agreements with existing service providers.

30. In choosing selection methods for grant programs, the principal consideration is to adopt a process through which the projects most likely to contribute to the cost-effective achievement of the program’s objectives will be consistently and transparently selected for funding consideration. In this context, competitive selection processes are recognised as representing best practice in the context of grants administration, and the Commonwealth Grant Guidelines (CGGs) outline that, unless specifically agreed otherwise, competitive, merit based selection processes should be used, based upon clearly defined selection criteria.

31. In most cases, CfC providers had been initially selected using competitive processes. During the two phases of reform, FaHCSIA, in line with government decisions, undertook non competitive selection processes, in which existing providers were assessed on the basis of current performance and ability to provide services aligned with the requirements of the FSP. This had the effect of aligning the end dates of all CfC funding agreements and maintaining stability in the services delivered to support the implementation of program reforms. A further effect is that most service providers have now received several funding extensions since their initial selection. In seeking approval for the selection process to be undertaken, FaHCSIA’s briefings to the Minister did not refer to any requirements or principles of the CGGs, including the emphasis on using competitive selection processes. In addition, although those briefings identified the providers the department proposed be offered further funding, they did not clearly identify the selection criteria that had been used in reaching the recommendation.

32. The CGGs, and related changes to the financial framework legislation, were expected to improve the quality of grants administration and ensure Australian taxpayers receive the best possible value for money from Australian Government grants. Accordingly, it is important that FaHCSIA reflect upon the administration of grant programs that predated the CGGs, including by seeking opportunities to enhance value for money through the adoption of competitive selection processes (at appropriate intervals). The Australian Government is also seeking to improve the accessibility of the Not for Profit sector to grant funding opportunities. Enabling other potential providers to compete for CfC funding would be consistent with that goal, and is possible under the current FSP program guidelines. In this context, as CfC is now in a period of consolidation, and with all existing agreements expiring in June 2014, it would be reasonable to expect FaHCSIA’s planning for further grant funding would give appropriate consideration to the use of competitive, merit-based selection processes for future delivery of CfC, and that the reasons to do otherwise would be clearly canvassed in advice provided to government.

Performance monitoring and reporting (Chapter 4)

33. FaHCSIA has established detailed reporting arrangements under its performance framework to gather information from service providers about the performance of CfC activities. Through structured arrangements FaHCSIA receives information about levels of client activity and the types of services used, as well as assessments by service providers about their performance against the requirements of funding agreements. Information is also collected from providers on immediate and intermediate outcomes experienced by people using CfC services. FaHCSIA collects a significant amount of data from service providers, however, the data did not always reflect key aspects of service delivery and service providers had limited awareness of the application of this data. Service providers also informed the ANAO that formal feedback mechanisms, such as the distribution of case studies, best practice examples and information regarding the performance of the program nationally, are currently under developed and would be useful ways to contribute to continuous improvement in service delivery. FaHCSIA could improve its interaction with providers to increase its understanding of the reliability and validity of performance data.

34. Assessing the overall impact of CfC is challenging and, in addition to collecting reliable and relevant performance information, periodic evaluations are an important aspect of performance management. FaHCSIA has implemented a sound evaluation approach by conducting longitudinal evaluations spanning several years. The first phase of the CfC evaluation was completed in 2008, and in addition to providing FaHCSIA with a view on the impact of CfC, the evaluation also provided a baseline against which further assessments of impact could be made. A second phase of the evaluation is currently underway. This evaluation will be able to draw on the performance information now collected by FaHCSIA from service providers to provide insight into the specific contributions made by CfC to improvements in community-level indicators of family functioning.

35. FaHCSIA undertakes various monitoring activities to maintain oversight of contracted service providers. Primarily, this takes the form of reporting by service providers, although staff in FaHCSIA’s network of state and territory offices undertake a varying level of site visits. In a program like CfC, with dispersed service provision and relatively small and localised activities, site visits can be an effective form of monitoring which enables departments to better understand issues and risks to service delivery outcomes, and also to understand the less tangible results of projects which may not be easily captured in formal reporting. A more systematic approach to site visits would assist the department in its oversight role. In relation to the Facilitating Partner model, FaHCSIA has given the lead NGOs considerable autonomy in their operations. While this allows for a flexible approach to service delivery at the local level, it does expose the department to additional delivery risks, in that FaHCSIA would normally undertake a provider risk assessment in the normal course of engaging a service provider. Under the Facilitating Partner model this is not done as the Community Partner organisations that ultimately deliver services are engaged by the Facilitating Partner. Under current monitoring arrangements FaHCSIA has limited oversight of the relationship between Facilitating Partners and the subcontracted Community Partners. To improve this situation, without unduly restricting flexibility, FaHCSIA could consider options such as regular surveys of Community Partners to gain their perspective on operations and the relationship with Facilitating Partners. Developing and contracting specialised third party monitoring services may also be an option for the department to consider as a way of strengthening its monitoring of on the ground delivery.

36. A key initiative undertaken by FaHCSIA as part of streamlining the administration of the FSP has been to reduce red tape. Some positive progress has been made on this initiative with some useful reductions to service provider reporting and efforts to increase electronic reporting. However, other program initiatives have served to increase reporting requirements on providers and consequently reduce the benefits of the administrative streamlining. It will be important for FaHCSIA to continue its efforts to strike an appropriate balance between accountability and outcomes; reviewing the FSP Administrative Approval Requirements is one area where this work could continue.

Summary of agency response

FaHCSIA provided a formal response to the audit which is contained in full in Appendix 1. A summary of FaHCSIA’s response was also provided:

37. FaHCSIA welcomes the ANAO report as an informative and constructive appraisal of FaHCSIA’s management of the three Communities for Children activities under the Family Support Program—Communities for Children Facilitating Partner; Communities for Children Direct; and Communities for Children Indigenous Parenting Services.

38. FaHCSIA aims to provide an integrated suite of family support services. The Family Support Program, created in 2009, brought together a range of children and family service elements and further reforms in 2011 added additional service types to the program. FaHCSIA remains committed to improving the effectiveness of the Family Support Program and its efficient management, and has recently initiated the Family Support Program Future Directions review aimed at strengthening the design, management and delivery of the program. The review will pay particular attention to the level of integration, planning and targeting processes for the three Communities for Children types.

Recommendations

Footnotes

[1] Statutory child protection is also referred to as tertiary intervention. Tertiary interventions are strategies that target families in which child neglect or abuse has already occurred. These strategies seek to reduce the long‑term implications of neglect and abuse and prevent it from reoccurring.

[2] AIHW produces the Child Protection Australia report annually, which contains comprehensive information on state and territory child protection and support services, and the characteristics of Australian children within the child protection system.

[3] The rate of increase in child abuse and neglect may reflect changes in state and territory policies and processes, increasing community awareness of child neglect and abuse, and broadened definitions of child neglect and abuse. However, AIHW reports that children on care and protection orders have been increasing for at least 15 years.

[4] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Educational outcomes of children on guardianship or custody orders, Child Welfare Series no. 42, AIHW, Canberra, 2007.

[5] Council of Australian Governments, Protecting children is everyone’s business: National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children 2009–2020, COAG, Canberra, 2009.

[6] Activity means any tasks, activities, services or other purposes for which funding is provided.

[7] The Activity Delivery Area is based on a population demographic identified using the Australian Standard Geographical Classification (ASGC). The ASGC is used by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) for the collection and dissemination of geographically classified statistics. The ASGC is used to improve the comparability and usefulness of reporting generally, and to ensure that outcomes and statistical data may be comparable to other programs and initiatives.

[8] CfC Direct and CfC IPS do not operate as place‑based models as CfC FPs do. They deliver a specific activity in a specified area defined in their funding agreement.

[9] Notifications consist of contacts made to an authorised department by persons or other bodies making allegations of child abuse or neglect, child maltreatment or harm to a child.

[10] Substantiation refers to a possible outcome of an investigation of a notification. To substantiate means that there is reasonable cause to believe that the child has been, was being, or was likely to be abused, neglected or otherwise harmed.

[11] At any point in the child protection process (from notification, through investigation to substantiation), an agency responsible for child protection can apply to the relevant court to place a child on a care and protection order. This may occur in situations where the family resists supervision and counselling, where other avenues for resolution of the situations have been exhausted, or where removal of a child into out‑of‑home care requires legal authorisation. Out‑of‑home care provides alternative accommodation for children where parents are incapable of providing adequate care; where alternative accommodation is required during times of family conflict; or where the child is the subject of a substantiation and requires a protective environment.

[12] Many children on care and protection orders are in out-of-home care. Differences in data provided by the states and territories should be taken into account when making comparisons and drawing conclusions on totals of state and territory statistics. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Child Protection Australia 2010-11, AIHW, Canberra, 2011, pp. 1–2.

[13] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Educational outcomes for children on guardianship or custody orders, Child Welfare Services no. 42, AIHW, Canberra, 2007.

[14] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2012. Children and young people at risk of social exclusion: links between homelessness, child protection and juvenile justice. Data linkage series no. 13 Cat. No. CSI 13. Canberra: AIHW.

[15] AIHW 2012. Children and young people at risk of social exclusion: links between homelessness, child protection and juvenile justice. Data linkage series no. 13. Cat. No. CSI 13. Canberra: AIHW. pp. 5–-6.

[16] <http://www.aifs.gov.au/cfca/pubs/factsheets/a142086/index.html> accessed 7 October 2012.