Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of Commonwealth Responsibilities under the National Partnership Agreement on Preventive Health

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Health and Ageing and the Australian National Preventive Health Agency in fulfilling the Commonwealth’s role in implementing the Council of Australian Government’s National Partnership Agreement on Preventive Health, to achieve the Agreement’s objectives, outcomes and outputs, including supporting all Australians to reduce their risk of chronic disease.

Summary

Introduction

1. Chronic diseases—illnesses that are prolonged in duration, do not often resolve spontaneously, and are rarely cured completely—are the leading causes of death and disability in Australia, and their prevalence is increasing in Australia and many parts of the world.1 For these reasons, and to contain the high and growing cost of health care2, preventing chronic diseases has been a major health priority of the Australian, state and territory governments in recent years.

2. To address the rising prevalence of lifestyle-related chronic diseases, the Australian Government has committed $932.7 million over nine years, commencing in 2009–10, to a new National Partnership Agreement on Preventive Health (the Agreement), agreed with state and territory governments through the Council of Australian Governments (COAG).3 The Agreement sets out five high-level objectives, relating to:

- providing support to Australians in reducing their risk of chronic disease in various settings (including schools, workplaces and communities);

- working with industry sectors (including food, sport, recreation and fitness) to offer healthy food choices and increase physical activity;

- supporting behavioural change through public education and social marketing;

- investment in the evidence base and a national workplace audit; and

- the establishment of a new national preventive health agency.

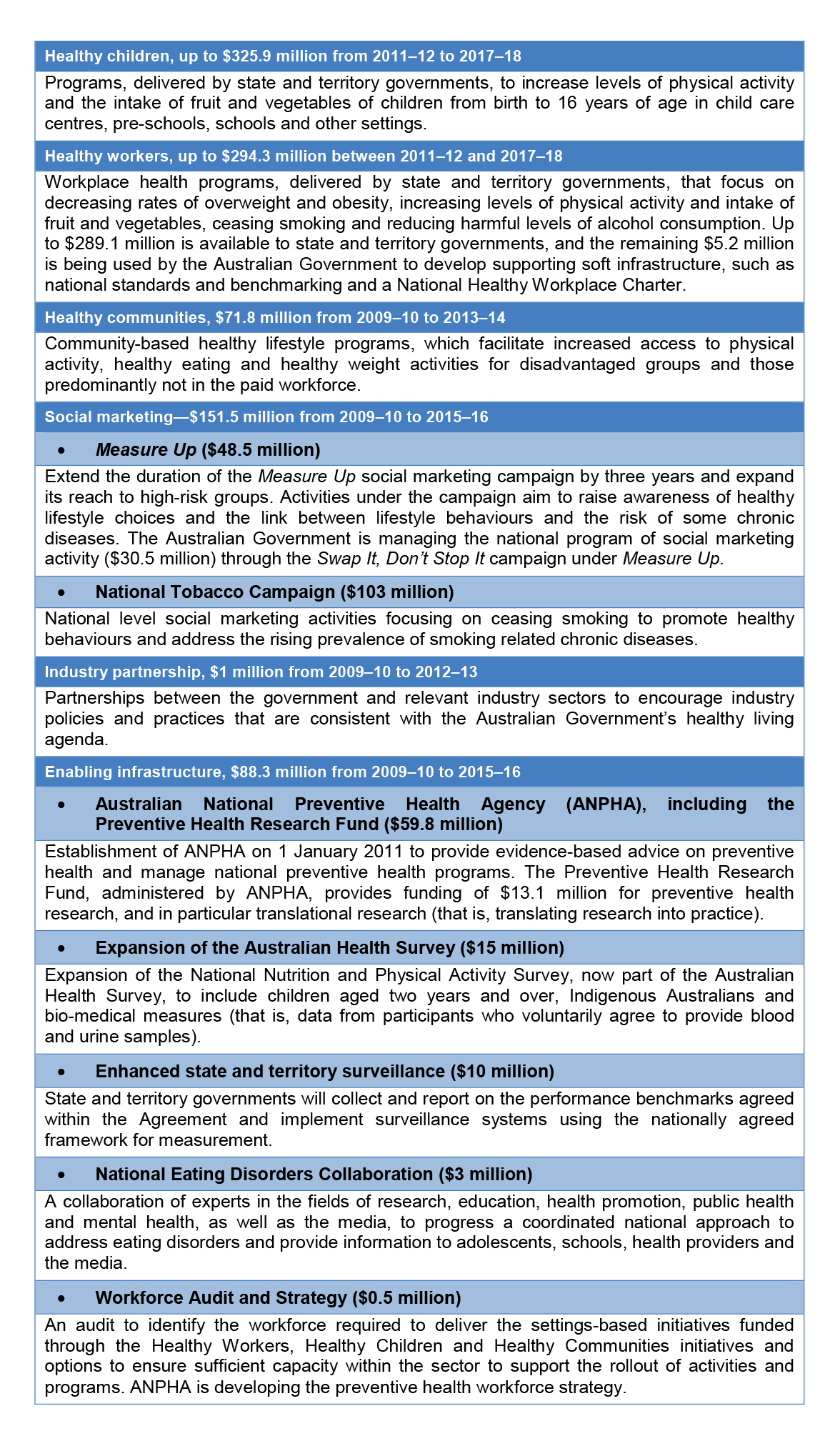

3. To achieve these objectives, the Agreement outlines the delivery of 11 initiatives or outputs, summarised at Table S1.

Table S1: Initiatives under the National Partnership Agreement on Preventive Health

4. State and territory governments are responsible for implementing two initiatives under the Agreement—Healthy Children and Healthy Workers—and undertaking social marketing that complements Commonwealth activity as well as enhanced state and territory surveillance. The Department of Health and Ageing (DoHA), which is responsible for achieving the Australian Government’s health priorities (outcomes), including reducing the incidence of preventable mortality and morbidity throughout Australia, and the Australian National Preventive Health Agency (ANPHA), which was established as part of the Agreement, are responsible for implementing the remaining initiatives in consultation with the states and territories.4

5. The Agreement was originally intended to be implemented over the period 2009 to 2015. However, in June 2012, the Agreement was varied and it is now scheduled to conclude in 2018.5 It provides for both ‘facilitation’ and ‘reward’ payments, totalling $643 million, to be made to states and territories. The facilitation payments are used to fund activities undertaken to implement Agreement-related reforms, while the reward payments reward jurisdictions for achieving agreed improvements in aspects of healthy living.6 At the time of audit fieldwork to October 2012, none of the components relating to the reward payments had been assessed or made.

6. The reward payments will be assessed against a number of performance benchmarks that are specified in the Agreement and translate its medium to long term outcomes to the period of the Agreement. From 1 July 2009 to 30 June 2018, the Agreement aims to:

- prevent any rise in the level of obesity of both children and adults in the Australian community;

- lead to increases of 0.6 and 1.5 respectively in the mean number of daily serves of fruits and vegetables consumed by children and adults; and

- lead to increases in the proportion of children and adults participating in moderate physical activity every day of at least 60 minutes for children and 30 minutes for adults.

7. The Agreement also aims to lead to a 3.5 per cent reduction in the proportion of adults smoking daily by 2013, against a 2007 baseline.7

Audit objective and criteria

8. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of DoHA and ANPHA in fulfilling the Commonwealth’s role in implementing the COAG National Partnership Agreement on Preventive Health, to achieve the Agreement’s objectives, outcomes and outputs, including supporting all Australians to reduce their risk of chronic disease. The high-level audit criteria used to make this assessment were that DoHA and ANPHA:

- were effectively fulfilling the Commonwealth’s roles to plan for, contribute to and monitor the achievement of the Agreement’s objectives, outcomes and outputs;

- have developed the enabling infrastructure to support initiatives for healthy living, including by effectively establishing ANPHA;

- were efficiently and effectively conducting social marketing campaigns; and

- were effectively implementing other initiatives under the Agreement.

Overall conclusion

9. To target the lifestyle risk factors of chronic disease, the Australian Government has committed $932.7 million to the National Partnership Agreement on Preventive Health (the Agreement). The Government, through the Department of Health and Ageing (DoHA) and the new Australian National Preventive Health Agency (ANPHA), is responsible for implementing the Agreement, in conjunction with the states and territories.8 The Agreement is at a relatively early stage of implementation, having commenced in 2009–10, and is now scheduled to terminate in June 2018.

10. Overall, a good start has been made in implementing the Commonwealth’s roles under the Agreement. Between them, DoHA and ANPHA have commenced all Australian Government initiatives under the Agreement, with some well underway. In particular, the agencies have: contributed to planning for the implementation of the Agreement; commissioned social marketing campaigns to encourage Australians to reduce the incidence of smoking and obesity; provided grants to organisations to deliver community-based healthy lifestyle programs; liaised with, and entered partnerships with, industry sectors to promote a healthy living agenda; and helped fund and arrange the expansion of the Australian Health Survey, the initial results of which will progressively become available between October 2012 and June 2014.

11. ANPHA, itself a key element of the enabling infrastructure under the Agreement, was established on 1 January 2011 with effective support from DoHA. ANPHA has made good progress in meeting its legislative requirements and strategic goals. Particular achievements include the development of a knowledge hub, completion of an initial round of

13 research grants, undertaking the development of a framework for the evaluation of the Agreement and development of an interim research strategy. In the first 18 months of operations, ANPHA has also established the key elements of governance envisaged under the Commonwealth Australian National Preventive Health Agency Act 2010 (ANPHA Act) and the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (FMA Act), including its Advisory Council, expert committees and Audit Committee.

12. While a good start has been made in implementing the Australian Government initiatives specified in the Agreement to deliver the associated outputs, challenges remain in measuring performance against the outcomes and objectives specified in the Agreement. To provide a sound basis for measuring performance against the benchmark targets in the Agreement, against which reward payments will be assessed from June 2016, DoHA still has work to do with the states and territories to finalise: the baseline data for the benchmarks specified in the Agreement9; the detailed methodology for collecting performance data; and the division of responsibilities between the Commonwealth and the states and territories for collecting the data. This work is also central to allowing an assessment of the Agreement in meeting its outcomes. It is also important that DoHA, in conjunction with states and territories, actively monitor their performance in achieving the Agreement’s objectives, and identify opportunities to improve performance and support Australians to reduce their risk of chronic disease.

13. COAG did not intend that ANPHA hold exclusive responsibility for preventive health, with significant functions continuing to be the responsibility of DoHA and state and territory health departments. Nonetheless, the Australian Government has made a substantial investment in establishing ANPHA as a standalone agency with national responsibilities, necessitating a clear allocation of roles and responsibilities between agencies so as to avoid unnecessary overlap and duplication. To minimise confusion about the respective roles of DoHA and ANPHA (and other health agencies) going forward, there would be benefit in DoHA and ANPHA actively reviewing the alignment of their responsibilities, particularly as ANPHA’s role in preventive health continues to develop.

14. As an agency subject to the FMA Act, ANPHA is expected to observe the requirements of the Australian Government’s campaign advertising framework and the 2010 Guidelines on Information and Advertising Campaigns by Australian Government Departments and Agencies (Advertising Guidelines). The audit assessed the effectiveness of ANPHA’s administration in developing the second and third rounds of the Swap It, Don’t Stop It advertising campaign and its adherence to the requirements of the advertising framework. While ANPHA adhered to the certification, publishing and reporting requirements of the Advertising Guidelines, there was scope to more clearly correlate the factual information with the messages being delivered in the campaigns by including, in compliance statements, a list of statements appearing in creative materials that is clearly linked to the references backing the claims.

15. The audit also assessed ANPHA’s administration of the first round of grants under its Preventive Health Research Fund against the Commonwealth Grant Guidelines (CGGs). While the key processes adopted by ANPHA were generally consistent with the CGGs, ANPHA did not ensure that the Health Minister was contemporaneously briefed on her specific obligations as a funding approver under the FMA Act, Financial Management and Accountability Regulations 1997 (FMA Regulations) and the CGGs. Further, the CEO of ANPHA approved a variation to the research grants funding that the Minister had originally approved. While the CEO had authority to approve the variation, it would have been prudent for ANPHA to advise the Minister at that time of the need for the variation and subsequent new approval, as the research grant guidelines informed applicants that the Minister would be the funding approver. Subsequent advice provided to the Minister to address these matters contained some minor errors, indicating that there is scope for ANPHA to improve quality control over its briefing material.

16. The facilitation payments that have been made to the states and territories to the end of June 2012 greatly exceed the $84.7 million that they had budgeted to spend to that time in their implementation plans. This occurred as a result of the variation to the Agreement, which re-profiled the funding allocation resulting in an additional payment of $82.5 million to the states and territories. These additional funds were part of the facilitation payments initially scheduled to be paid in July 2012. As a consequence, the states and territories rather than the Commonwealth will receive the benefit of the early payment of those funds. In this regard, the ANAO has previously reported on the opportunity costs of making significant pre-payments and recommended that DoHA provide advice to the Health Minister on the risks, if any, and opportunity costs of making such payments in advance of need.10

17. The ANAO has made two recommendations relating to the implementation of the Agreement. One recommendation is directed at DoHA, to give priority to progressing the means for measuring performance against the benchmarks in the Agreement. The other recommendation is directed at ANPHA, to more clearly demonstrate the factual basis for statements appearing in campaign advertisements.

Key findings by chapter

Implementation framework for the National Partnership Agreement on Preventive Health (Chapter 2)

18. DoHA has established consultative and decision making forums to manage the implementation of Commonwealth, state and territory responsibilities under the Agreement. While these have worked reasonably well, state and territory health departments consulted in the course of the audit indicated that, as a means of strengthening national coordination arrangements, there would be benefit in reviewing the roles, responsibilities and operations of the two main management committees—the Implementation Working Group and the Healthies Steering Committee. These committees, which have Commonwealth, state and territory health department representation, were established to consider strategic and operational issues respectively. The Implementation Working Group did not meet between 2010 and 2012, and state and territory health departments consulted in the course of the audit saw benefit in the group continuing to meet to consider higher level strategic issues, with the focus of the Healthies Steering Committee being on operational matters. Reflecting these concerns, the Implementation Working Group agreed in September 2012 to a review of the terms of reference of the group and its sub-committees.

19. As indicated at paragraphs 5 and 6, the Agreement lists national performance benchmarks for reductions in health risk factors that the Commonwealth, state and territory governments agreed to meet over specified periods. The degree to which the benchmarks are met will determine the reward payments that are made to the states and territories under the Agreement.

20. While the Agreement clearly lists the national benchmarks, specification of the methods of collecting reliable and consistent data required to measure performance against the benchmarks has proved difficult. A broad framework for measuring performance benchmarks was approved by Health Ministers in November 2010, however the baseline data for the benchmarks have not yet been collated and how the data will be collected has still to be finalised.11 These delays put at risk the consistent measurement of performance against the national benchmarks and the determination of reward payments to the states and territories. It is therefore important that DoHA places a high priority on finalising the baseline data and specifications and arrangements for collecting data to assess performance against the benchmarks.

21. Under the revised Agreement, the amounts of facilitation payments to the states and territories have been increased and the amounts of reward payments have been reduced commensurately. There have been large pre-payments of facilitation payments to the states and territories to the end of June 2012, including $82.5 million being paid by way of advance payments in June 2012, without advice to the Commonwealth Health Minister on the opportunity costs of the payments.

22. DoHA and ANPHA have actively engaged with a range of key stakeholders involved in implementing preventive health programs. DoHA has liaised closely with the food industry in the implementation of the Food and Health Dialogue under the Industry Partnership Agreement. Key stakeholders also advised that ANPHA had actively engaged with their organisations since its establishment. While there was some delay against the original scheduling of ANPHA’s planned publication of its Stakeholder Engagement Strategy, a final version was published in June 2012. ANPHA has also organised and participated in seminars and working groups with other agencies.

Australian National Preventive Health Agency (Chapter 3)

23. ANPHA has prepared a five-year strategic plan, and operational plans for 2011–12 and 2012–13, which have met requirements to be approved by the Minister for Health, after consultation with state and territory ministers for health. The first full performance report against the operational plan for ANPHA will be for the 2011–12 financial year. While ANPHA generally performed well against the 2011–12 operational plan, there was some slippage or adjustment to timelines and tasks, which is reflected in the 2012–13 operational plan.

24. ANPHA is required to meet governance and financial management arrangements under its enabling legislation (the ANPHA Act) and the FMA Act. ANPHA has established the key governance requirements required under the ANPHA Act and the FMA Act, including establishing the Advisory Council, expert committees and an Audit Committee, with a charter and work program covering risk management, fraud control and development of an internal audit plan. All committees have terms of reference and appointees to the committees have appropriate experience and qualifications.

25. ANPHA has established a risk management framework based on risk management standard AS/NZS/ISO 31000:2009. The Fraud Control Plan is generally in line with the Commonwealth Fraud Control Guidelines. While the risk management framework is generally sound, there would be benefit in ANPHA completing its business continuity and disaster recovery plans as soon as practicable. ANPHA should also satisfy itself that it has suitable risk mitigation strategies in place in relation to its outsourced services.

26. While ANPHA has prepared Chief Executive Instructions, the detailed rules and manuals which support them (with the exception of rules and manuals on procurements and grants) have not yet been completed. ANPHA has committed to completing the business rules by 31 December 2012. Once the necessary supporting financial rules and manuals for the Chief Executive Instructions have been completed, ANPHA will have established the key elements of its governance and financial management framework, as envisaged under the ANPHA and FMA Acts.

Preventive health social marketing campaigns (Chapter 4)

27. The Australian Government, through DoHA, has a long history in running social marketing campaigns aimed at encouraging Australians to adopt healthy lifestyles and reduce the risk of contracting chronic diseases. The Swap It, Don’t Stop It campaign, focusing on overweight and obesity prevention, and the National Tobacco Campaign, focusing on reducing smoking, are two campaigns that were originally developed by DoHA, but are now conducted by ANPHA. Phase 2 of the Measure Up obesity prevention/active lifestyle social marketing campaign and the National Tobacco Campaign transferred to ANPHA upon its establishment. The development and implementation of the two campaigns was undertaken by the department on behalf of ANPHA until December 2011. During this period of co-administration there was some initial confusion as to which agency had the primary responsibility for reporting expenditure against the campaign, as evidenced in the lack of procurement reporting for Swap It, Don’t Stop It in DoHA’s and ANPHA’s Murray Motion (Senate Order 192)12 reporting for 2010–11. ANPHA has since included the relevant Swap It, Don’t Stop It contracts as part of its 2011–12 financial year Senate Order reporting.

28. The ANAO assessed the Swap It, Don’t Stop It campaign’s compliance with the Advertising Guidelines.13 Compliance assessments prepared for the Independent Communications Committee for the second and third rounds of the campaign contained reasonable representations of compliance with the five Information and Advertising Campaign Principles in the Advertising Guidelines. The chief executive’s certification was signed by the appropriate authority and uploaded to the Department of Finance and Deregulation’s website in a timely way.

29. Principle 2 of the Advertising Guidelines provides that campaign materials should enable the recipients of the information to distinguish between facts, comment, opinion and analysis (paragraph 20) and, where information is presented as a fact, it should be accurate and verifiable (paragraph 21). The Swap It, Don’t Stop It campaign provides ‘suggestions’ for better health. Nonetheless, these suggestions should be evidence-based. The Statement of Compliance did not contain an evidence matrix or other document outlining the factual basis for statements made in the Swap It, Don’t Stop It creative materials. While the Advertising Guidelines do not specify the use of such a document, the inclusion in future compliance statements of a mechanism to clearly correlate the factual statements appearing in creative materials to the references backing the claims would strengthen the transparency of ANPHA’s conduct of social marketing campaigns.

30. Principle 4 of the Advertising Guidelines provides that campaigns should be evaluated to determine their effectiveness (paragraph 33). There have been two evaluations using a selection of Australians within the intended audience and charting their recall, views and the effect of the Swap It, Don’t Stop It advertisements. The results of evaluations of the Swap It, Don’t Stop It campaign have been encouraging, and other indications of the effectiveness of these campaigns (and other related measures) will be provided once the results of the current National Health Survey are available from October 2012 and after completion of ensuing National Health Surveys, which are usually conducted every two years.

Preventive health research and other preventive health initiatives (Chapter 5)

31. ANPHA has made good progress in establishing national preventive health infrastructure, including through the administration of an initial round of 13 research grants and the development of an interim research strategy. However, it remains a priority for ANPHA to finalise and start implementing its final research strategy so that its objectives can be realised as soon as possible.

32. As mentioned in paragraph 15, there was evidence of imprecision in ANPHA advice to the Minister on financial framework issues and financial variations relating to the first round of research grants, indicating there is scope for improved quality control over material going to the Minister.

33. The ANAO’s analysis of DoHA’s administration of the Healthy Communities initiative, and administration of Local Government Area grants under that initiative, found that key processes were generally consistent with the CGGs. As the Local Government Area grants are at an early stage of implementation, it is too early to assess the benefits of the program for participants. However, early indications from an evaluation of the pilot sites in Phase 1 showed a general increase in participant awareness of health risk factors and the skills needed to address these risks.

34. One area where there is room for improvement in DoHA’s administration of the Healthy Communities initiative is the Quality Framework. Notably, only a small number of applications have received service provider and program registration since the Healthy Living Network went live on 20 March 2012, although all six National Program Grants are now registered. DoHA has advised that it is now working closely with the external service provider and local government areas on the promotion of the Healthy Living Network and encouraging local government areas to register.

35. The implementation of the Australian Health Survey is proceeding within expected timeframes. The expected completion of the survey is in contrast to the implementation of the Preventive Health Workforce Audit and Strategy. While the audit was completed after difficulties in defining workforce boundaries were resolved, the finalisation of the Preventive Health Workforce Strategy is not expected to be presented to the COAG Standing Council on Health until the second half of 2013. To limit the risk that there will be only a limited opportunity to achieve significant outcomes before the Agreement term expires, ANPHA should consider placing a higher priority on the implementation of the Preventive Health Workforce Strategy.

ANPHA’s response to the audit

36. The ANAO’s examination of the governance framework and the program implementation arrangements will contribute to the agency’s compliance framework and continued sound governance.

DoHA’s response to the audit

37. The Department agrees to Recommendation No. 1 and adds that processes are currently underway to address this through established governance arrangements under the Agreement. Consultation with relevant technical experts and with the states and territories, for resolving data issues to measure performance for reward payments as highlighted in this recommendation, are currently being progressed by the Department.

Footnotes

[1] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Risk factors contributing to chronic disease, Canberra, 2012, p. 5.

[2] While the cost of chronic disease in Australia is not known, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare has reported that the cost of services for health conditions that involve chronic diseases was well over $13 billion in 2004–05. ibid., p. 10.

[3] National Partnership Agreements are one of three different mechanisms for making payments to states and territories under the Federal Financial Framework agreed by COAG. The other two mechanisms are National Specific Purpose Payments, for spending in key service delivery sectors, and general revenue assistance, consisting of Goods and Services Tax payments and other general revenue assistance.

[4] ANPHA was established under the Australian National Preventive Health Agency Act 2010 and, under Section 2A(1) of the Act, advises on and manages national preventive health programs. At June 2012, ANPHA had 39 full-time equivalent staff and, in the revised Budget for the 2012–13 financial year, a total resourcing allocation of $69.4 million. ANPHA is a prescribed agency under the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997.

[5] The Australian Government varied the Agreement to extend its duration by three years in recognition of the difficulties inherent in achieving population change within the short time period of the original Agreement and difficulties being encountered in measuring the outcomes (described in the following paragraph) required to assess the performance of states and territories and their eligibility for reward payments.

[6] Originally, the reward payments under the Healthy Children and Healthy Workers initiatives for achievement of seven performance benchmarks equalled the facilitation payments for these initiatives (that is, they were 50 per cent of the total maximum payment to the state or territory). However, following the renegotiation of the agreement in June 2012, the reward payments were reduced and now amount to 25 per cent of the total maximum payments to states and territories for these initiatives. The facilitation payments were correspondingly increased and now amount to 75 per cent of total payments.

[7] See Part 4 of the Agreement—Performance benchmarks and indicators.

[8] To date, 11 initiatives have been pursued to realise the objectives set out in the Agreement, three of which are the responsibility of state and territory governments.

[9] The baseline data for the national performance benchmarks, as indicated in paragraphs 5 and 6, is specified in the Agreement as the last available data at June 2009—apart from the 2007 adult smoking benchmark.

[10] ANAO Report No. 45 2011–12, Administration of the Health and Hospitals Fund, pp. 109–114.

[11] The Chairman of the COAG Reform Council, Paul McClintock, AO, has referred to the need for adequate data to report progress against performance indicators and benchmarks, noting that ‘all National Agreements have examples of performance indicators which have no data or have inadequate data to report progress’. Paul McClintock, AO, The COAG Reform Agenda: How are governments performing so far, CED, Melbourne, September 2010.

[12] The Senate Order for Departmental and Agency Contracts was introduced in 2001 to improve public access to information about Australian Government contracting. The main principle on which the Order is based is that parliamentary and public access to government contract information should not be prevented, or otherwise restricted, through the use of confidentiality provisions, unless there is sound reason to do so.

[13] The Independent Communications Committee was established in March 2010 to provide advice to agency Chief Executives on advertising campaigns with expenditure over $250 000, including advice on compliance with principles 1 to 4 of the Advertising Guidelines.