Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of the Child Dental Benefits Schedule

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Health’s and the Department of Human Services’ management and administration of the Child Dental Benefits Schedule.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Good dental health is an essential part of good general health and wellbeing.1 It is increasingly recognised that a good dental health foundation in childhood, including appropriate dental visiting patterns, is a key determinant of dental health throughout life.2 The impact of poor dental health extends beyond the individual to the wider economy through lost productivity and costs to the health system.3

2. The $2.7 billion Child Dental Benefits Schedule (CDBS or the program) is a means tested program intended to provide children with capped benefits for basic dental services. The CDBS commenced on 1 January 2014 and provides up to $1000 in benefits over two calendar years for basic dental services (preventive and treatment) for eligible children aged 2 to 17 years. The CDBS replaced the previous Medicare Teen Dental Plan, which operated between 2008 and 2013.

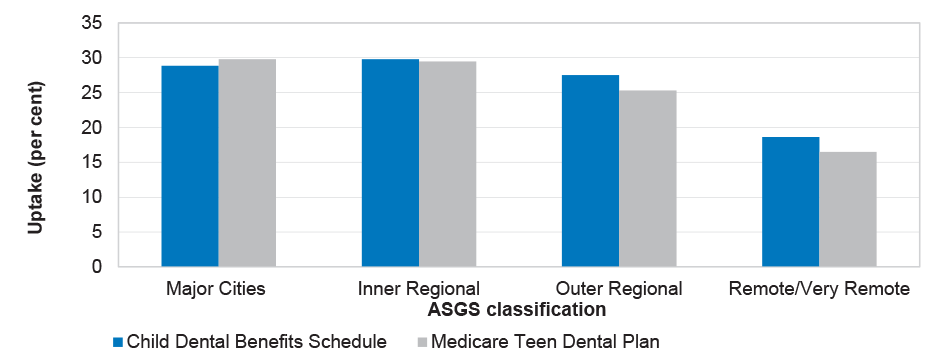

3. The Department of Health (Health) and Department of Human Services (Human Services) are responsible for administering and managing the CDBS. Health is responsible for policy design, while Human Services is responsible for delivering administrative services under the CDBS. The departments have a hierarchy of formal agreements which outline their respective roles and responsibilities.

4. Health has identified that the purpose of the CDBS is to address declining child oral health and support the longer-term strategy of improving population-wide oral health. The CDBS contributes to Outcome 3 (Access to Medical and Dental Services) in Health’s Portfolio Budget Statements. The relevant program objective under this outcome is to ‘improve access to dental services for children’.4

Audit objectives and criteria

5. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Health’s and the Department of Human Services’ management and administration of the Child Dental Benefits Schedule.

6. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level audit criteria:

- Health and Human Services have effective governance and administrative arrangements to support the delivery of the Child Dental Benefits Schedule;

- Human Services has implemented systems and processes to administer payments to eligible clients in an accurate and timely manner; and

- Health and Human Services effectively monitor, evaluate and report on compliance5 and performance to inform delivery of the Child Dental Benefits Schedule.

Conclusion

7. Health and Human Services’ day-to-day administration of the Child Dental Benefits Schedule has been largely effective. The ANAO identified scope for improvement in relation to Health’s risk management planning for the program and Human Services’ quality framework for the manual data matching process used to maintain the integrity of program data.

8. The policy design of the program has addressed some of the shortcomings of the previous Medicare Teen Dental Plan. In common with the previous program, the CDBS continues to attract relatively low customer uptake—around 30 per cent in the 2014 and 2015 calendar years—as compared to Health’s projections, resulting in a significant underspend of allocated funding. In the context of low program uptake, there should be a focus on improved communication with the target population and review activity to inform advice to government on the progress and future directions of the CDBS. The program’s second year of operation ends in December 2015 and is an appropriate point for Health to take stock.

Supporting findings

Establishing the Child Dental Benefits Schedule

9. The policy rationale and initial design of the CDBS were informed by a national advisory body, data analysis and previous experience in the delivery of dental benefits schemes, including the Medicare Teen Dental Plan.

10. Health developed a project timeline which outlined expected timeframes and deliverables against key stages of program implementation. To inform the detailed design of the CDBS, Health also sought expert advice and considered how known issues from the operation of previous dental schemes could be addressed. Health’s implementation approach provided sufficient time for Human Services to develop the enabling systems and processes necessary to implement the CDBS on 1 January 2014.

11. Human Services developed a project management plan that reflected the department’s service delivery responsibilities and specified project deliverables and key outcomes to support the timely implementation of the CDBS on 1 January 2014. Adequate support tools were also developed including business requirements, communication strategies, risk plans and a compliance program.

12. During the design and implementation of the CDBS, Health consulted with key stakeholders on the operational aspects of the program and the composition of the Dental Benefits Schedule, which specifies the items and associated benefits covered by the CDBS.

Administering the Child Dental Benefits Schedule

13. The Business Agreement between Health and Human Services clearly sets out the administrative arrangements intended to support the operation of the CDBS and establishes a sound overall framework for administration of the program. Health has met and Human Services has substantially met the Business Agreement obligations relating to the CDBS.

14. Human Services provides quarterly reports to Health on its achievements against two key performance indicators in the Business Agreement: the timeliness of claims processing; and reporting and exchange of information.

15. Health identified the key areas of risk for the CDBS during the design and policy development phase. The department did not subsequently develop a formal risk management plan to document risks associated with the ongoing management and implementation of the CDBS, and risk treatments. The ANAO has made a recommendation on this matter.

16. Human Services developed a risk management plan for the project phase of the CDBS and finalised an operational risk management plan in August 2015, one year after the closure of the project phase.

Delivery of client services

17. Human Services developed clear guidance material and operational procedures to assist staff in meeting their program responsibilities. A targeted education strategy was delivered to dental providers to encourage compliance and provide operational support on servicing requirements.

18. The ANAO’s analysis of claiming data to 1 May 2015 identified that Human Services had applied relevant controls and checks intended to ensure that dental providers had met the requirements for accessing the program.

19. The automated process for identifying and notifying eligible children is largely accurate and timely. A reliance on regular manual data matching to identify eligible children continues to delay program access for affected customers and despite the risk of error, manual data matching activities do not incorporate a quality control process. Human Services advised the ANAO that administrative processes for customers who have been affected by complications in data matching are determined on a case-by-case basis.

20. The main ICT system used to communicate eligibility information to dental providers has experienced intermittent technical issues in receiving and displaying eligibility information over the course of the program and the design of the system audit log does not provide Human Services with assurance about the accuracy of information communicated to dental providers.

21. In consultation with Health, Human Services developed a communications strategy, relevant materials and a notification process to inform eligible children and their carers about the program. Notwithstanding this effort, there has been limited evaluation of the approach to inform ongoing communication needs and activity, and the ANAO has recommended a review of communications and the development of a strategy. There has also been limited engagement with community groups and third party organisations.

22. The ANAO’s analysis of claims made between 1 January 2014 and 1 May 2015 indicated that Human Services’ systems-based business rules and calculation of benefits provide reasonable assurance that claims are paid in accordance with program requirements.

23. Human Services has incorporated a range of quality checking processes to mitigate the risk of administrative error in CDBS processes. The quality framework could be improved by incorporating regular monitoring and internal reporting of error rates for manual data matching processes, which are routinely applied to help reconcile data which cannot be matched through automated processes. The department should also establish performance indicators and benchmarks for manual processes. The ANAO has also made a recommendation on these matters.

24. Consistent with Human Services’ broader compliance strategy, the department has adopted a risk-based approach to managing compliance under the CDBS that is informed by analysis of program data. Compliance activity commenced during the course of this performance audit and it is therefore too early to determine whether the department’s approach has been effective.

Program outcomes

25. Despite an expansion of the eligibility criteria and services offered through the CDBS, only around 30 per cent of eligible children claimed benefits in 2014 and 2015, resulting in a substantial underspend of program funds. The low rate of uptake by the eligible population reduces the program’s contribution to Health’s Outcome 3 (relating to access to medical and dental services) and affects the achievement of the program objective, which is to improve access to dental services for children.

26. While detailed program data has been collected on the operation and utilisation of the CDBS, Health has not focussed on identifying the key drivers behind low program uptake. December 2015 marks the end of the first two years of operation and is an appropriate point for Health to review its initial modelling for the program, including anticipated expenditure and uptake rates. A review would help identify actions to address the low uptake in the short term and provide a baseline for future program reviews or evaluations.

27. Human Services collects a large volume of administrative data on the CDBS and during the course of the audit developed and commenced performance monitoring against two internal key performance indicators.

28. To date the framework for monitoring and reporting on program performance has provided only limited information to assess the achievement of program objectives. As discussed, at the end of December 2015 the CDBS will have operated for two calendar years and this will be the natural time to review program results, the reasons for the lower than expected uptake, and likely future demand for the program. As program expenditure is driven by customer utilisation (demand), such analysis will inform modelling of the demand and future costs of the program. The ANAO has made a recommendation on these matters.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No. 1 Paragraph 3.9 |

To identify and treat risks to the administration of the CDBS, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Health develop, implement and monitor an overarching risk management plan. Department of Health’s response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No. 2 Paragraph 4.22 |

In the context of low program uptake the ANAO recommends that Health, in consultation with Human Services:

Department of Health’s response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No. 3 Paragraph 4.30 |

To improve performance measurement and reporting and to provide assurance on the quality of manual data matching processes under the CDBS, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Human Services:

Department of Human Services’ response: Agreed. |

|

Recommendation No. 4 Paragraph 5.26 |

To assist in assessing the achievement of program objectives, the ANAO recommends that Health:

Department of Health’s response: Agreed. |

Summary of entity responses

29. The Department of Health’s and the Department of Human Services’ responses to the proposed report are provided below, with the full responses provided at Appendix 1.

Department of Health

Health notes the findings of the audit and agrees with the recommendations.

Department of Human Services

The Department of Human Services (the department) welcomes this report.

The department notes that the ANAO has found that the day-to-day administration of the Child Dental Benefits Schedule has been largely effective. The department agrees with the ANAO’s recommendation and prior to the completion of the report commenced implementation of a quality assurance process for the five per cent of records that require manual data matching.

The department notes the ANAO finding that a high degree of accuracy of at least 95 per cent was achieved in data matching between the department’s internal systems.

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Good dental health is an essential part of good general health and wellbeing.6 It is increasingly recognised that a good dental health foundation in childhood, including regular dental visiting patterns, is a key determinant of dental health throughout life.7 The impact of poor dental health extends beyond the individual to the wider economy through lost productivity and costs to the health system.8

1.2 Over the past decade, Australian governments have increased their focus on improving access to dental services for children and adults. In July 2004, the then Government introduced limited Medicare funding for dental services for patients whose chronic health conditions were exacerbated by dental problems. In the 2007–08 Budget, these benefits were expanded under the Chronic Disease Dental Scheme as part of broader reforms to Medicare. The Medicare Teen Dental Plan was also introduced in July 2008, providing eligible families with vouchers of $150 each year to assist with dental check-ups for teenagers between 12 and 17 years of age.

1.3 In August 2012, the Australian Government announced the Dental Health Reform Package, comprising three elements: $1.3 billion for a National Partnership Agreement for Adult Public Dental Services9; a $225 million Flexible Grants Program10; and $2.7 billion for the Child Dental Benefits Schedule (CDBS or the program). The Chronic Disease Dental Scheme closed in November 2012, and the Medicare Teen Dental Plan closed in December 2013 to make way for the Dental Health Reform Package.

Child Dental Benefits Schedule

1.4 The CDBS is the primary focus of this performance audit. It is a means-tested program intended to provide eligible children with capped benefits for basic dental services.

1.5 The CDBS commenced on 1 January 2014. It is a statutory program under the Dental Benefits Act 2008 (the Act), which was amended in 2012 to enable the replacement of the Medicare Teen Dental Plan with the CDBS. It was further amended in 2014 to introduce compliance powers, aligned with the broader Medicare program.11

1.6 When the CDBS commenced, the Dental Benefits Rules 2013 (which operate subordinate to the Act) were in operation. These were repealed and replaced by the Dental Benefits Rules 2014 (the Rules).12 The Rules outline the operational framework for the CDBS and include the Dental Benefits Schedule, which outlines the items and associated benefits covered by the CDBS.

Benefit amount

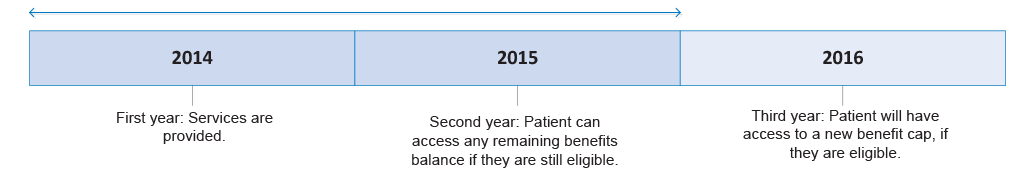

1.7 The CDBS is intended to deliver up to $1000 in benefits over two calendar years for basic dental services (preventive and treatment) for eligible children aged 2 to 17 years. If a patient does not use all of their $1000 benefit in the first year of eligibility, the patient can use the remaining benefit amount in the second year, provided they remain eligible (refer to Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1: Operation of the benefits cap

Source: Department of Health, Guide to the CDBS, p. 6.

Eligibility criteria

1.8 To be eligible under the CDBS a child must: be aged 2 to 17 for at least one day of the calendar year; be eligible for Medicare; and receive a relevant Australian Government payment for at least one day of the calendar year. The types of payments that satisfy the means test are outlined in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Types of Australian Government payments that satisfy the means test for the Child Dental Benefits Schedule

|

Payment recipient |

Receives |

|

Child’s parent, carer or guardian |

Family Tax Benefit Part A; Parenting payment; or Double Orphan Pension. |

|

Child |

Family Tax Benefit Part A; Abstudy; Carer Payment; Disability Support Pension; Parenting Payment; Special Benefit; Youth Allowance; financial assistance under the Veterans’ Children Education Scheme or the Military Rehabilitation and Compensation Act Education and Training Scheme and cannot be included as a dependent child for the purposes of Family Tax Benefit because they are 16 years or older. |

|

Teenager’s partner |

Family Tax Benefit Part A; or Parenting payment. |

Source: Department of Human Services’ website.

1.9 The Department of Human Services (Human Services) notified approximately 3.1 million children in 2014 and 2.9 million children between January and June 2015 of their eligibility under the program.

Dental services and workforce

1.10 Dental services for the CDBS can be claimed through public or private dental service providers (dental providers) who have chosen to participate in the program. A total of 73 dental services13 can be claimed through the CDBS, ranging from diagnostic, preventive and restorative services to oral surgery and prosthodontic (denture) services.

1.11 Between January 2014 and May 2015, approximately 16 147 registered general and/or specialist dentists were eligible to provide services under the CDBS. Of these, 11 321 dental providers had participated in the CDBS (around 70 per cent of eligible providers). Initially, state and territory public dental providers were eligible to provide services under the CDBS until 31 December 2014.14 Legislative changes since the CDBS commenced have allowed public dental providers to continue operating under the program until 30 June 2016.

Administrative framework

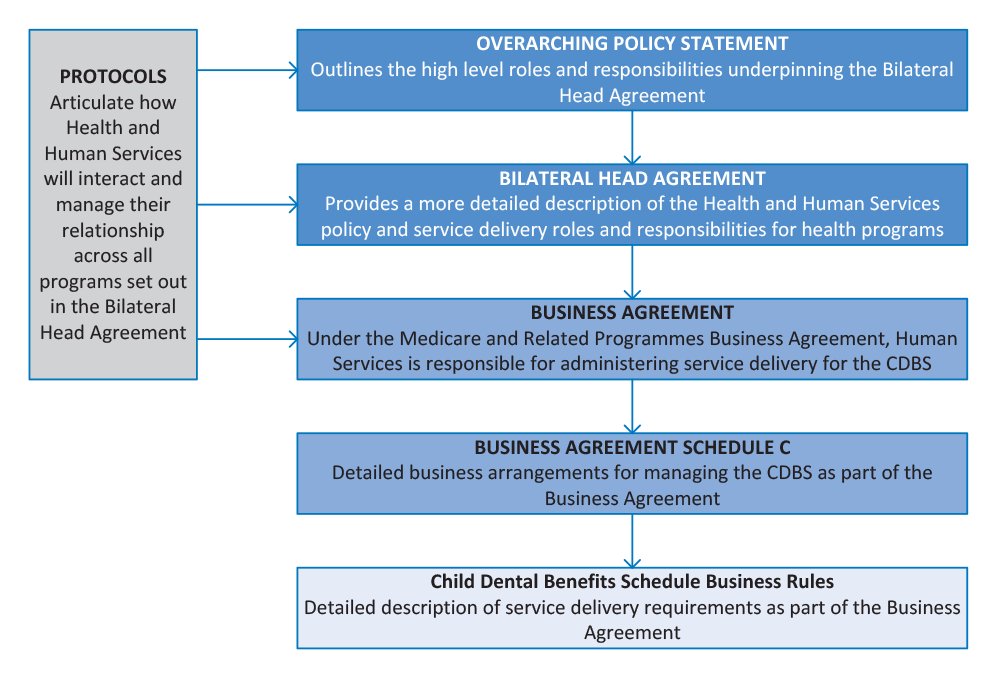

1.12 The Department of Health (Health) and Human Services are responsible for administering and managing the CDBS. Health is responsible for policy design, while Human Services is responsible for delivering administrative services. The departments have a hierarchy of formal agreements and documents which outline their respective roles and responsibilities, as outlined in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2: Administrative framework for the CDBS

Source: ANAO analysis of Health information.

Funding

1.13 Health is responsible for monitoring program expenditure relative to budget estimates and Human Services is responsible for processing eligible payments under the CDBS.

Administered funding

1.14 To provide services under the CDBS, $2.8 billion in administered funding has been allocated to the program over six years from 2012–13 comprising a special appropriation of $189 million in 2013–14, increasing to $706 million in 2017–18. An indexation pause introduced as part of savings measures in the 2015–16 Budget resulted in revised funding for the CDBS, with the Government estimating savings of $125.6 million over four years as a result.15 The original and revised program funding is outlined in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: Administered funding for the CDBS

|

Administered Funding |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

|

Original funding |

189 718 |

603 117 |

635 698 |

670 068 |

|

Revised funding |

N/A |

312 839 (actual expenditure) |

605 451 |

615 973 |

Source: Department of Health information and Department of Health Portfolio Budget Statements 2015–16, p. 85.

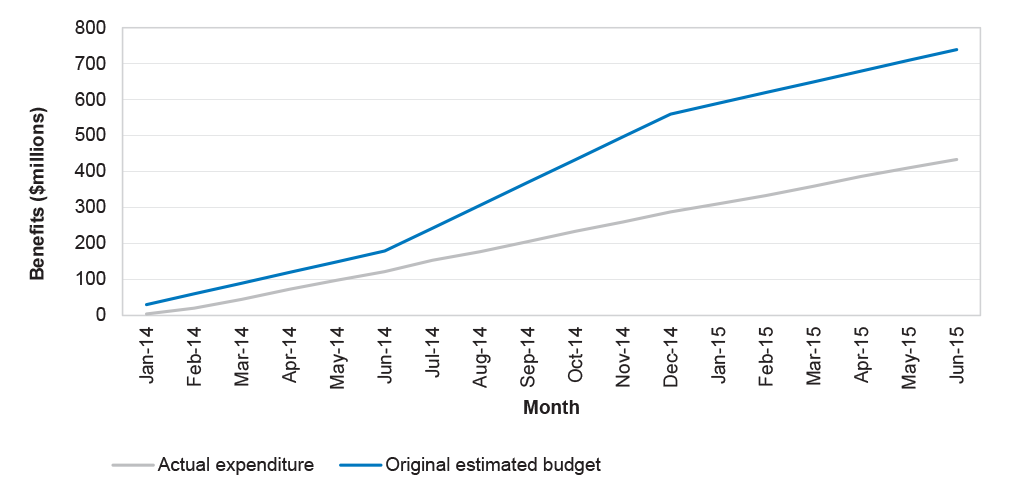

1.15 From the commencement of the CDBS on 1 January 2014 to 30 June 2015, approximately 6.8 million services were claimed at a total benefit of $433 million. This outcome was well below Health’s estimates of $739 million in program expenditure for this period, representing a significant variance between project and actual program expenditure of some $306 million, or 41 per cent, as shown in Figure 1.3.16

Figure 1.3: CDBS budget versus actual benefits paid

Source: ANAO analysis.

Departmental funding

1.16 Health received departmental funding of approximately $5.2 million for the CDBS over a four year period from 2012–13, while Human Services received departmental funding of approximately $46 million over the same period. Table 1.3 outlines Health’s and Human Services’ departmental funding for implementing and administering the CDBS.

Table 1.3: Departmental funding for Health and Human Services

|

Departmental funding |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

Total |

|

Health |

906 |

1 575 |

1 559 |

1 201 |

5 241 |

|

Human Services |

489 |

13 497 |

15 685 |

16 367 |

46 038 |

|

Total |

1 395 |

15 072 |

17 244 |

17 568 |

51 279 |

Source: Department of Health and Ageing, Portfolio Additional Estimates Statements 2012–13, p. 18; Department of Human Services, Portfolio Additional Estimates Statements 2012–13, pp. 17-18.

Previous reviews

1.17 The Dental Benefits Act 2008 (the Act) requires that a review of the Act’s operation be conducted after its first and third anniversaries and every three years following. Two statutory reviews by an independent panel into the operation of the Act have been undertaken, in 2009 and 2011. A non-statutory review was also conducted by the National Advisory Council on Dental Health (the NACDH) in 2012. A third statutory review was approved by the Minister for Health in April 2015 and is expected to be finalised in late 2015.

Statutory reviews of the Dental Benefits Act 2008

1.18 The independent panels’ reports on the first and second statutory reviews into the Act were provided to the Minister for Health on 23 December 2009 and 20 December 2011 respectively. The reports were subsequently tabled in Parliament on 15 March 2010 and 15 March 2012 respectively and outlined some of the concerns raised by stakeholders in relation to the Medicare Teen Dental Plan and the panels’ suggestions to address these concerns. Table 1.4 summarises the key stakeholder concerns, and the related suggestions made by the panels.

Table 1.4: Key stakeholder concerns with the Medicare Teen Dental Plan

|

Key stakeholder concerns |

Suggestions made by review panels |

|

The low uptake rate of the program and inconsistencies in the geographical distribution of voucher uptake. |

Advertise the program more broadly; improve the ‘branding’ of the voucher; and alter the timing of the bulk mail-out of vouchers. |

|

The level of benefit provided for the preventive dental check. |

Replace the single preventive dental check schedule item number outlined in the Dental Benefits Schedule with individual item numbers for each procedure. |

|

Teenagers being charged the full rebate amount for a short oral exam compared with a sibling or friend who received a more comprehensive service for the same price. |

Replace the single preventive dental check schedule item number outlined in the Dental Benefits Schedule with individual item numbers for each procedure. |

|

Access to, and Medicare coverage of, follow-up treatment identified during a preventive dental check. |

No suggestions made. |

Source: First and Second Reviews of the Dental Benefits Act 2008.

1.19 The design of the CDBS has addressed the suggestions made by the panels through: a higher cap balance; the introduction of specific schedule item numbers for each service provided; and the inclusion of treatment services in the Schedule of items. However, low uptake remains an issue under the CDBS, as discussed further in Chapter Five.

Audit objective, criteria and methodology

1.20 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Health’s and the Department of Human Services’ management and administration of the Child Dental Benefits Schedule.

1.21 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Health and Human Services have effective governance and administrative arrangements to support the delivery of the Child Dental Benefits Schedule;

- Human Services has implemented systems and processes to administer payments to eligible clients in an accurate and timely manner; and

- Health and Human Services effectively monitor, evaluate and report on compliance and performance to inform delivery of the Child Dental Benefits Schedule.17

1.22 The Department of Veterans’ Affairs has a limited role in administration of the CDBS, exchanging less than 300 eligible children’s details to Human Services. The Department of Veterans’ Affairs’ administration was not examined as part of this audit. Additionally, the audit did not assess the accuracy of the data provided by Centrelink and the Department of Veterans’ Affairs to Medicare18 or the processes applied to extract information from their systems to identify children eligible for the CDBS.

Audit methodology

1.23 In conducting the audit, the ANAO met with relevant staff from Health and Human Services and consulted with relevant stakeholder groups. The ANAO also conducted analysis of quantitative data from Human Services’ ICT systems and reviewed key documentation related to the CDBS, including policy and operational documents, guidelines, procedures, performance data and financial information.

1.24 The audit was undertaken in accordance with the ANAO’s Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $563 019.

2. Establishing the Child Dental Benefits Schedule

Areas examined

This chapter examines the Department of Health’s (Health) and the Department of Human Services’ (Human Services) establishment of the Child Dental Benefits Schedule (CDBS), including policy design, implementation planning and stakeholder consultation.

Conclusion

Health’s and Human Services’ design and establishment of the CDBS was well informed and adequately planned. The departments’ implementation approaches provided sufficient time to develop the enabling systems and processes necessary to implement the CDBS on 1 January 2014.

Introduction

2.1 The ANAO examined Health’s and Human Services’ roles in establishing the CDBS including the development and implementation of policy and operational requirements, and consultation with stakeholders.

Was Health’s approach to policy design evidence-based?

The policy rationale and initial design of the CDBS were informed by a national advisory body, data analysis and previous experience in the delivery of dental benefits schemes, including the previous Medicare Teen Dental Plan.

2.2 The National Advisory Council on Dental Health (NACDH) was established in September 2011 to provide advice on dental policy options and priorities for the 2012–13 Budget. Following the release of the NACDH report in February 2012, $515.5 million in dental measures were announced in the 2012–13 Budget19 along with a commitment to undertake further dental reform in the 2013–14 Budget.

2.3 Health commenced developing options for the dental reform package in early 2012, having regard to the NACDH report. The policy approach involved both additional funding and redirecting funding from the existing Chronic Disease Dental Scheme and Medicare Teen Dental Plan. Table 2.1 shows the timeline for the development, consideration and announcement of the Dental Health Reform Package.

Table 2.1: Timeline for development of the Dental Health Reform Package

|

Date |

Event |

|

Early Jun 2012 |

Based on approaches developed by the NACDH, the then Minister for Health presents a range of options for dental reform aimed at adults and children to the Government. The option for the CDBS includes multiple models with variations in the eligible population and start dates. Each option is supported with information on the financial implications for implementation and ongoing service delivery. |

|

Mid Aug 2012 |

Ministers agree to progress negotiations with the Australian Greens(a) for a dental reform package targeting low income children and adults. Under this proposal, the CDBS was due to commence in July, six months after the closure of the Medicare Teen Dental Plan in December 2013. |

|

Late Aug 2012 |

Following successful negotiations with the Australian Greens, a New Policy Proposal for the Dental Reform Package is submitted to the Government by Health allowing for the CDBS to commence in January 2014. The New Policy Proposal also includes $62.6 million for Human Services to implement and deliver the CDBS from 2012–13 to 2016–17.(b) |

|

29 Aug 2012 |

The Government announces the Dental Health Reform package, which includes $2.7 billion for the CDBS. |

|

10 Dec 2012 |

The Dental Benefits Amendment Bill 2012, which amends the Dental Benefits Act 2008, receives royal assent. Operational details, rules and service items are specified in subordinate legislation and in the administrative arrangements and approaches to be developed by Health and Human Services. |

Note a: On 1 September 2010, the Australian Greens formally declared support for the Australian Labor Party in forming government, following the results of the federal election in August 2010. This support was predicated on a formal agreement between the two parties, which included a provision to increase federal investment in dental care.

Note b: These costings were developed by Human Services and approved by the then Department of Finance and Deregulation. They were based on assumptions about the operational requirements of the CDBS and the expected system changes and resourcing that would be required within Human Services to cover CDBS implementation and ongoing administration.

Source: ANAO analysis of Health information.

2.4 In addition to the NACDH report, the proposed policy options were informed by data from the operation of the Medicare Teen Dental Plan, and population data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics and the former Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs. Information on existing demand for dental services was sourced from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and the Australian Research Centre for Population Oral Health.

Was Health’s and Human Services’ implementation planning effective?

2.5 In October 2012, Health and Human Services established separate internal project teams to develop and implement the CDBS. Within Health the project focussed on defining the detailed requirements of the policy, with consideration given to previous dental benefits schemes (in particular the Chronic Disease Dental Scheme and Medicare Teen Dental Plan). The project team within Human Services focussed on implementing the IT system changes required to support the CDBS, the development of reporting mechanisms to Health to monitor program utilisation and expenditure and the development of communication and education material for customers and dental providers.

Health

Health developed a project timeline which outlined expected timeframes and deliverables against key stages of program implementation. To inform the detailed design of the CDBS, Health also sought expert advice and considered how known issues from the operation of previous dental schemes could be addressed. Health’s implementation approach provided sufficient time for Human Services to develop the enabling systems and processes necessary to implement the CDBS on 1 January 2014.

2.6 Health was responsible for formulating the policy parameters for the CDBS. The CDBS project timeline outlined expected timeframes and deliverables against key stages of program implementation, including: planning and policy scoping; drafting of the Dental Benefits Schedule; stakeholder consultation (including a public consultation process); development and amendment of legislation; and review and evaluation of the program.

2.7 The project timeline also outlined estimated implementation dates and underwent multiple iterations as initial planned milestones changed. However, the project schedule was only tracked until April 2013 and tasks associated with the implementation of the project, including the finalisation of the Dental Benefits Rules 2013, had not been completed by this date. While remaining tasks were supported by their own separate timelines, there would have been benefit in Health managing project implementation against a formal implementation plan that considered or outlined: the expected outcomes and benefits of the project; key risks; descriptions of the project scope; a project budget; and governance arrangements.20

2.8 Following the development of the CDBS project timeline, Health prepared a series of policy scoping documents that explored how known issues from the operation of previous dental schemes could be addressed in the detailed design of the CDBS. Health also engaged dental advisers throughout the design phase to provide expert clinical advice on the appropriateness and relevance of dental services that would be required to meet the intent of the CDBS.

Human Services

Human Services developed a project management plan that reflected the department’s service delivery responsibilities and specified project deliverables and key outcomes to support the timely implementation of the CDBS on 1 January 2014. Adequate support tools were also developed including business requirements, communication strategies, risk plans and a compliance program.

2.9 Implementation of the CDBS required a substantial change to Human Services’ IT systems and the development of: communication and education materials; staff guidance and training material; and a compliance program. Human Services adopted its corporate project management framework to implement the CDBS.21

2.10 In October 2012, Human Services commenced the development of standard project planning elements including: a project plan and schedule; risk management plan; budget; and governance arrangements. The project plan covered key aspects of implementation, including: expected outcomes and benefits; identification of key risks; descriptions of the project scope, deliverables and milestones, responsibilities, available funding and a project budget; governance arrangements; and a stakeholder management plan.

2.11 The project was substantially delivered according to the planned schedule, with some minor delays in the finalisation of customer and provider letters, and education materials for providers.

2.12 Overall the project resulted in:

- changes to Medicare IT systems to identify and record eligible children and to register eligible dental providers;

- the availability of self-service channels to enable customers and providers to access program and benefit entitlement balance information;

- program reports for Health to monitor program utilisation and expenditure;

- communication material and education products for customers and providers; and

- training and operational support products for Medicare service staff.

2.13 The CDBS was officially implemented on 1 January 2014, consistent with initial Government expectations, although online systems for public and provider self-service did not go live until 13 January 2014. This timing enabled Human Services to transfer and match 2.8 million Centrelink records with customer records held by the Medicare systems. In the interim, support arrangements were put in place to allow providers and customers to manually confirm eligibility with a Service Officer.22 Human Services has incorporated the CDBS into its standard governance processes, including corporate and business planning and risk management.

2.14 At the completion of the implementation project in August 2014, Human Services prepared a project closure report. This documented the status of all project deliverables, risks, the budget and lessons learned for future projects. The department commenced a post-implementation review during the course of the audit, which was completed in September 2015.

Did Health consult with key stakeholders?

During the design and implementation of the CDBS, Health consulted with key stakeholders on the operational aspects of the program and the composition of the Dental Benefits Schedule, which specifies the items and associated benefits covered by the CDBS.

2.15 In designing the CDBS, Health identified and engaged with stakeholders through both targeted and general processes conducted from October 2012. On 1 May 2013, Health undertook a public consultation process to inform the final stages of program design, canvass the views of the dental community and give stakeholders an opportunity to voice concerns. Health contacted 23 key stakeholders23 directly through a mail-out based on a list developed as part of the department’s planning for the consultation process.24

2.16 Health also prepared a public consultation paper which included a draft proposal for the Dental Benefits Schedule.25 The paper outlined key issues for consideration and comment, including: the scope of services to be provided; access for oral health practitioners; lessons learned from previous dental schemes; compliance and reporting arrangements; and education and communication with the dental industry and patients. Health received 38 submissions that indicated general support for the CDBS, with 24 respondents recommending the inclusion of additional items on the Dental Benefits Schedule.26 Health collated the responses to identify key points and consulted with the department’s dental advisers on specific suggestions for item inclusions and amendments.27 As a consequence, Health amended restrictions on some items in the Dental Benefits Schedule and added two additional items.

3. Administering the Child Dental Benefits Schedule

Areas examined

This chapter examines the Department of Health’s (Health) and the Department of Human Services’ (Human Services) governance arrangements and risk management approaches to support the operation of the Child Dental Benefits Schedule (CDBS).

Conclusion

Health has met and Human Services has substantially met the Business Agreement obligations relating to the CDBS. Human Services provides quarterly reports to Health on its achievements against two program key performance indicators (KPIs).

While the departments identified key areas of risk for the CDBS, Health has not developed a formal risk management plan to document: risks associated with the ongoing management and implementation of the CDBS; and risk treatments.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has recommended that the Department of Health develop, implement and monitor an overarching risk management plan.

Introduction

3.1 Health and Human Services have established a formal agreement—the 2012–2015 Business Agreement (Business Agreement)—setting out their respective roles, responsibilities and accountabilities.28

Is there clarity in administrative arrangements supporting the operation of the CDBS?

The Business Agreement between Health and Human Services clearly sets out the administrative arrangements intended to support the operation of the CDBS and establishes a sound overall framework for administration of the program. Health has met and Human Services has substantially met the Business Agreement obligations relating to the CDBS.

3.2 Schedule C of the Business Agreement outlines the requirements and obligations of Health and Human Services in respect to the Dental Benefits Schedule. The Schedule reflects the requirements of the Dental Benefits Rules 2014 applying to the administration of the CDBS.

3.3 Under the Business Agreement, Health is required to provide Human Services with timely, accurate and appropriate advice about any changes to the policy, systems or administrative arrangements for the CDBS, where those changes may impact on Human Services’ ability to provide efficient services. Table 3.1 shows the ANAO’s assessment of whether Health has met its responsibilities under the Business Agreement.

Table 3.1: Health’s responsibilities under the Business Agreement

|

Health’s responsibilities |

ANAO assessment |

|

Appropriately consult and involve Human Services on any proposed amendments to relevant legislation. |

Met |

|

Take account of concerns or requests by Human Services regarding the design of services which might arise from such amendments. |

Met |

|

Ensure that Human Services is appropriately consulted and involved in ensuring that new or altered services arising from changes to government policy can be effectively and efficiently implemented by Human Services. |

Met |

|

Write to dental service provider organisations including the Australian Dental Association and state/territory governments to inform them about the CDBS and any changes that may arise in relation to the Dental Benefits Schedule. |

Met |

Source: ANAO analysis.

3.4 Under the Business Agreement, Human Services is responsible for service delivery relating to the CDBS. Key activities include: the timely and accurate registration of eligible persons and dental providers; the delivery of timely and accurate CDBS payments to eligible patients and dental providers; maintaining accurate and up-to-date data and records; supporting and maintaining existing payment systems; and maintaining effective working relationships. Table 3.2 details the ANAO’s assessment of whether Human Services has met its responsibilities under the Business Agreement.

Table 3.2: Human Services’ responsibilities under the Business Agreement

|

Human Services’ responsibilities |

ANAO assessment |

|

Development of, and adherence to, written protocols that facilitate the matching of Medicare program data with data from Centrelink programs and data provided by the Department of Veterans’ Affairs. |

Met |

|

Identifying and notifying customers of their eligibility and assessment, processing and payment of claims under the Dental Benefits Schedule. |

Met |

|

Assessment of eligibility of providers and processing of payment to providers where dental benefits have been assigned. |

Met |

|

Provision of advice via a public telephone enquiry line (132 011) and a provider telephone enquiry line (132 150). |

Met |

|

Provision of education material and information to the public and providers about the operation of the CDBS as well as the maintenance of the Human Services website. |

Met |

|

Provide all required information, reports, financial statements and claiming, benefits and dental service data within specified timeframes. |

Met |

|

Promotional and communications activities which relate specifically to the delivery of CDBS functions and services. Communication with people from diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds and Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people. |

Met |

|

Undertake its responsibilities and obligations in accordance with the Program Integrity and Risk Management Protocol made under the Agreement and subject to existing legal constraints. |

Substantially Met(a) |

|

Monitor claiming data of services and undertake targeted audits and compliance activities as appropriate, pending the passage of relevant legislation, to check if eligible providers are meeting their obligations as defined by the Dental Benefits Act 2008 and the legislative instruments made under it. |

Met |

Note a: Further detail on the ANAO’s assessment of ‘substantially met’ in relation to risk management can be found in paragraphs 3.10–3.12.

Source: ANAO analysis.

Is performance monitored under the Business Agreement?

Human Services provides quarterly reports to Health on its achievements against two key performance indicators in the Business Agreement: the timeliness of claims processing; and reporting and exchange of information.

3.5 The Business Agreement included program key performance indicators (KPIs) agreed in May 2015. They are based on the KPIs for Medicare and Related Programs found in Schedule A of the Business Agreement. Human Services provided the first quarterly report to Health in May 2015 and the second in July 2015 and reported that both KPIs had been met. The results for January to March 2015 and April to June 2015 are detailed in Table 3.3.

Table 3.3: Business Agreement KPI targets and results

|

Key performance indicator and target |

January–March 2015 result |

April–June 2015 result |

|

Timeliness of claims processing (Target: 90%) |

98.5% |

98.1% |

|

Reporting and exchange of information (Target ≥ 95%) |

100% |

100% |

Source: ANAO analysis of Human Services information.

Have key CDBS program risks been assessed?

3.6 The Program Integrity and Risk Management Protocol under the Business Agreement sets out the responsibilities and obligations of Health and Human Services in relation to program integrity and risk management. It provides that Human Services must have appropriate risk management systems in place for each administered program, while Health’s role is to address policy issues that affect program integrity and risk management and identify any new or increasing risks.

Health

Health identified the key areas of risk for the CDBS during the design and policy development phase. The department did not subsequently develop a formal risk management plan to document risks associated with the ongoing management and implementation of the CDBS, and risk treatments.

3.7 In August 2012, Health completed a Risk Potential Assessment Tool for the CDBS.29 This tool identified the key areas of risk for the CDBS, the associated severity and the likelihood of the risks materialising. Health identified multiple high risks in pursuing the CDBS, including: financial risks (due to the expected cost of the program); possible opposition from stakeholders (particularly states and territories); and the interdependency of the CDBS on other schemes.30 Based on the identified risks and associated mitigation strategies, Health considered that the CDBS carried a ‘Medium’ risk. Health also noted that implementation of the CDBS could only be considered in its context as part of the broader Dental Health Reform Package, as it would contribute to implementation of the Package as a whole.31

3.8 Health has not developed a formal risk management plan to document and guide its mitigation of risks associated with the delivery of the CDBS. The development of a risk management plan, drawing on experience to date, would contribute to Health’s overall administration of the CDBS. The end of the first two years of operation of the CDBS provides an opportunity for Health to consider and evaluate the ongoing risks associated with the administration of the program and develop a risk management plan.

Recommendation No.1

3.9 To identify and treat risks to the administration of the CDBS, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Health develop, implement and monitor an overarching risk management plan.

Department of Health’s response: Agreed.

Human Services

Human Services developed a risk management plan for the project phase of the CDBS and finalised an operational risk management plan in August 2015, one year after the closure of the project phase.

3.10 The CDBS was initially implemented as a project within Human Services, to introduce necessary changes to departmental systems and processes. The project then transitioned to business-as-usual operations, covering ongoing operations and administration of the CDBS after its commencement on 1 January 2014. A risk management plan is required for all projects and programs, as per Human Services’ Enterprise Risk Management Policy. Further, each risk management plan must: be approved within three months32; be updated monthly or when significant changes occur; and consider the transitional risk to business-as-usual operations.

3.11 In July 2013, Human Services developed a risk management plan for the project phase of the CDBS. The plan identified nine key risks relating to: compliance; communications and training material; business agreements and customer experience; privacy; and IT systems, including data accuracy. While the residual rating for each key risk was low, no review of the risk management plan occurred beyond October 2013. Following the commencement of the CDBS in January 2014, a review of the project risk management plan would have helped the department assess whether operational risks had been identified and controls were appropriately targeted.

3.12 In August 2014 Human Services developed a draft operational risk management plan for the CDBS, which was finalised in August 2015. The plan identified six key risks relating to: compliance; communications; notification of eligibility; program expenditure; and stakeholder management. Each had a residual risk rating of low. In September 2015, Human Services updated the CDBS risk management plan to include risks to data quality and integrity.

4. Delivery of client services

Areas examined

This chapter examines the systems and processes established by the Department of Human Services (Human Services) to deliver services under the Child Dental Benefits Schedule (CDBS), including operational communication with customers and dental providers, claims processing and compliance activities.

Conclusion

Human Services’ systems and processes to deliver services for the CDBS are largely effective. The department sent notifications to 3.1 million children in 2014 and 2.9 million children between January and June 2015. Approximately 6.8 million services were processed and more than $433 million in benefits were paid between 1 January 2014 and 30 June 2015.

A reliance on manual data matching continues to delay program access for affected customers and there is scope to strengthen relevant controls to provide additional assurance over the manual data matching processes. While both departments have distributed materials to promote the program, there has been limited evaluation of the communications approach to inform ongoing communication needs and activity.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has made two recommendations aimed at the Department of Health evaluating the approach to communications, and the Department of Human Services strengthening relevant controls and providing additional assurance over the manual data matching processes.

Human Services could also consider how to strengthen relevant controls so as to provide greater assurance over the accuracy of information provided through its Health Professionals Online Services portal. There would also be value in the department: reviewing its targeting of compliance activity; and identifying any emerging trends that may affect program administration, by reviewing information received through complaints, feedback and customer enquiries.

Introduction

4.1 Human Services is responsible for the day-to-day administration of the CDBS. Since the closure of the project phase, the CDBS has been integrated into Human Services’ broader service delivery operations. Administration of the program is shared among a number of branches within the department, with overall responsibility assigned to the Medicare and Veterans Branch of the Health Programmes Division.33

Do departmental staff and dental service providers have appropriate guidance?

Human Services developed clear guidance material and operational procedures to assist staff in meeting their program responsibilities. A targeted education strategy was delivered to dental providers to encourage compliance and provide operational support on servicing requirements.

Staff capability

4.2 Information on the CDBS is available to Human Services staff through the department’s Operational Blueprint34, eLearning and tailored training modules. Human Services has also established a range of program-specific procedures and guidance material for staff involved in processing, data management and customer service. As at 31 October 2015, there had been 8 428 attendances at CDBS training courses. The training and guidance material is consistent with the business rules and legislation establishing the CDBS.

Provider education

4.3 In late November 2013, Human Services sent letters to 14 382 dental providers with a Medicare provider number to inform them of the commencement of the CDBS. The letter referred to a range of reference materials published on the Human Services website.35 The reference materials on the department’s website as at August 2015 clearly outlined the servicing and claiming requirements of providers, and were developed in collaboration with the Australian Dental Association, as well as drawing on stakeholder input through Health’s public consultation process.

Is program access restricted to eligible dental service providers?

The ANAO’s analysis of claiming data to 1 May 2015 identified that Human Services had applied relevant controls and checks intended to ensure that dental providers had met the requirements for accessing the program.

4.4 In order to access the CDBS, a provider must hold general and/or specialist registration with the Dental Board of Australia and have a Medicare provider number for each practice location.36 Human Services applies a specialty code against the Medicare provider number to recognise and limit program access to eligible providers. Table 4.1 shows the figures for provider participation in the CDBS between 1 January 2014 and 1 May 2015.

Table 4.1: Dental provider participation in the CDBS

|

Provider status |

Number |

Per cent |

|

Registered general and/or specialist dentists with a Medicare provider number and specialty code |

16 147 |

N/A |

|

Eligible dentists who have participated in the CDBS |

11 321 |

70 |

Source: ANAO analysis of Human Services information.

Have eligible customers been identified and notified?

The automated process for identifying and notifying eligible children is largely accurate and timely. A reliance on regular manual data matching to identify eligible children continues to delay program access for affected customers and despite the risk of error, manual data matching activities do not incorporate a quality control process. Human Services advised the ANAO that administrative processes for customers who have been affected by complications in data matching are determined on a case-by-case basis.

The main ICT system used to communicate eligibility information to dental providers has experienced intermittent technical issues in receiving and displaying eligibility information over the course of the program and the design of the system audit log does not provide Human Services with assurance about the accuracy of information communicated to dental providers.

4.5 Eligibility for the CDBS is established annually according to an age and means test administered by Human Services and the Department of Veterans’ Affairs (Veterans’ Affairs).37 Human Services determines customer eligibility for the CDBS through a data exchange protocol between its Centrelink and Medicare programs38 and Veterans’ Affairs. Eligibility data for approximately 3.4 million children was transferred between 1 January 2014 and 1 May 2015.

4.6 Approximately 95 per cent of records were automatically matched to a Medicare customer record and the eligible child or their parent was notified of CDBS eligibility for the calendar year. The ANAO’s analysis of data exchanged up to 1 May 2015 identified that in cases where data was transferred successfully, there was a high level of integrity between the data received from Centrelink/Veterans’ Affairs and the data recorded in Medicare’s systems. There were a small number of cases where eligibility data sent by Centrelink had not been recorded in Medicare’s systems because of data processing issues, such as differences in the way a child’s date of birth or name are recorded.

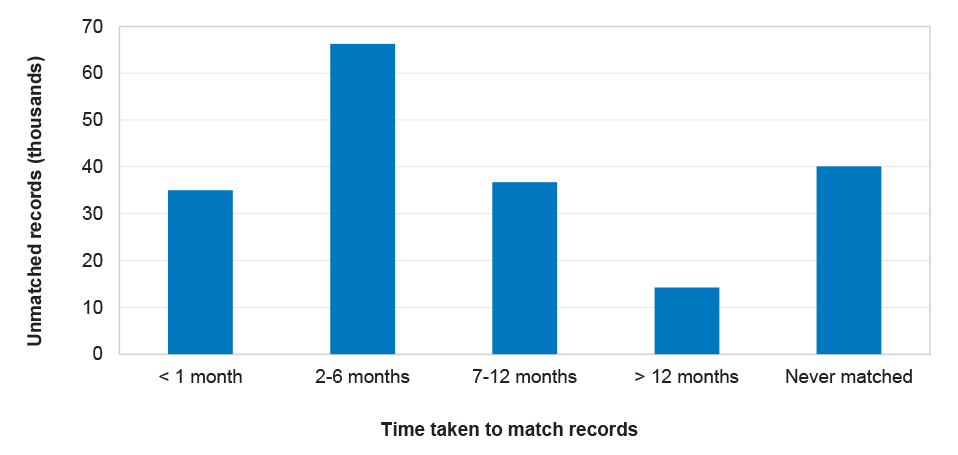

4.7 Where the automated process cannot match to a Medicare record, a manual matching process is undertaken by members of a dedicated team of 14 staff who work on a range of complex Medicare eligibility issues.39 At 1 May 2015, a total of 146 266 customer records had been manually matched. Figure 4.1 shows the timeframes taken to match these records. Around 40 000 records were yet to be matched at 1 May 2015, and more than half of these had been unmatched for the duration of the program.40 Human Services advised that some customers who are eligible for Centrelink payments are not enrolled in Medicare or not eligible for Medicare. In other cases, customers may have different information recorded on Centrelink/DVA, and Medicare systems.41 As at 31 October 2015, the number of unmatched records was 11 783.

Figure 4.1: Time taken to manually match customer records

Source: ANAO analysis of Human Services information.

4.8 Of the manually matched records at 1 May 2015, approximately 570 were assigned to the wrong Medicare customer record and later unmatched.42 Additionally, 25 records required rematching three or more times. Service Officers who had conducted fewer than 500 manual matches had a higher rate of matching error. At the time of audit fieldwork, there was no systematic quality control process in place to provide departmental management with additional assurance regarding the accuracy of these resource-intensive manual processes. Human Services advised the ANAO that it planned to commence a quality control process for manual reconciliation activities in November 2015.

4.9 The ANAO identified a number of cases where delays and errors in data matching had a direct impact on program access. For example, the ANAO identified 985 cases where eligibility data was received by Medicare in 2014 but a match was either still outstanding or not made until 2015 when the customer was no longer eligible. Human Services advised the ANAO that administrative processes for customers who have been affected by complications in data matching are determined on a case-by-case basis.

Communicating eligibility information directly to customers

4.10 In January each year, following the identification of eligible children, Human Services performs a bulk mail-out of notification letters advising customers of their eligibility for the CDBS. Mail-outs to newly eligible customers are also conducted on a fortnightly basis throughout the year.43 Unless a customer makes a specific request, the legislation does not require Human Services to issue notifications of eligibility beyond 31 October of each year.

4.11 In 2014, Human Services continued to issue letters until 15 December.44 For 2015, Human Services advised that it had decided to cease automatic notification on 31 October. The department was unable to provide a documented rationale for the changed approach to issuing notifications. In September 2015, the department made a subsequent decision to continue sending notification letters until 15 December 2015 and advised the ANAO that this arrangement would be reviewed annually.

4.12 As at 1 May 2015, Human Services had issued notification letters to approximately 3.4 million children.45 The ANAO found that each of the 258 772 newly matched children in the first quarter of 2015 were issued a corresponding notification letter and over 99 per cent of letters were issued within 30 days of the eligibility start date.46 Customers are also able to confirm eligibility and remaining cap balance through Medicare Online Services, by calling Medicare or by visiting a Service Centre.47

Communicating eligibility information to providers

4.13 Providers rely on accurate information from Human Services regarding patient eligibility before determining a patient’s service options and obtaining informed financial consent. While there is no legislative requirement for providers to confirm patient eligibility prior to performing a CDBS service, Human Services encourages providers to confirm eligibility through its Health Professionals Online Services (HPOS)48 and the Provider Hotline (132 150).49

4.14 Human Services has identified, in its risk planning for the CDBS, that the controls in place to mitigate the risk of inaccurate information provided through HPOS or the Provider Hotline involve: prompt investigation of issues; and testing any system changes. The department experienced intermittent HPOS functionality issues throughout late 2014 and early 2015, which were addressed through a system upgrade in May 2015. The most significant issue occurred in early January 2015 when the HPOS service was retrieving eligibility information from 2014. Human Services advised the ANAO that a system fix was effected within a week and the department has initiated a process to honour 1 911 CDBS items claimed on the basis of inaccurate information. The value of these payments has been estimated at $100 000.

4.15 The ANAO tested the HPOS audit logs for the period 1 January 2014 to 1 May 2015 to determine the accuracy of information displayed to providers when confirming eligibility. The testing identified that of the 1.3 million unique customer records accessed over the period, up to 31 000 (2.4 per cent) appeared to display incorrect eligibility information. Human Services advised that in these cases it is likely the server timed out and the provider was displayed an error message. Since error messages are logged in the same way as ineligibility messages, Human Services is not able to confirm whether the information displayed was accurate. The department could usefully consider how to strengthen relevant controls so as to provide greater assurance over the accuracy of information provided through HPOS50 and avoid providers potentially submitting claims based on inaccurate information. Human Services advised the ANAO that the complexity and age of existing ICT systems presents challenges in adopting cost-effective solutions to functionality issues.

Has the approach to promotion been adequate?

In consultation with Health, Human Services developed a communications strategy, relevant materials and a notification process to inform eligible children and their carers about the program. Notwithstanding this effort, there has been limited evaluation of the approach to inform ongoing communication needs and activity. There has also been limited engagement with community groups and third party organisations.

4.16 The first and second statutory reviews of the Dental Benefits Act 2008 observed that uptake for the Medicare Teen Dental Plan was low and the reviews recommended further work to more effectively promote the program. In response to the first review, Health commissioned market research that identified preferred methods of communicating with parents and providers and included an assessment of the program’s communications material.51

4.17 Prior to implementation of the CDBS, Human Services developed a communications strategy in consultation with Health outlining: key messages; operational activities to support communication to customers and providers; and management information required to assess the effectiveness of operational communication.

4.18 Under the communications strategy, Health was responsible for all policy, promotional and awareness-raising activities for the CDBS, including identifying opportunities to engage with community groups and third party organisations to address potential barriers in communication. While Health has initiated work on identifying these groups, there has been limited engagement to date. Noting there may be limited scope for additional promotion of the CDBS in a resource constrained environment, there remains benefit in Health continuing to support low‐cost and targeted promotional activity, including through relevant third parties.

4.19 Under the strategy, Human Services was responsible for operational communications relating to the CDBS, including advising customers and providers on how to access the scheme. Human Services developed a suite of CDBS communication materials including: brochures; fact sheets; radio broadcasts; print media; and a provider promotional toolkit. Table 4.2 outlines information collected by Human Services to assess the effectiveness of communication between December 2013 and June 2014.

Table 4.2: Information collected to assess the effectiveness of operational communication

|

Activity |

Result at 30 June 2014 |

|

Number of likes/shares/click throughs/re-tweets from social media posts. |

Reached approximately 10 000 users. |

|

Total number of hits to the CDBS web content across all customer sections of the website. |

104 303 unique visitors. |

|

Total number of hits to the CDBS web content across the provider section of the website. |

65 953 unique visitors. |

|

Customer feedback through social media and other departmental feedback channels. |

Not reported. |

|

Staff feedback on internal communication products. |

Not reported. |

|

Provider feedback through departmental feedback channels. |

Not reported. |

|

Media monitoring and analysis. |

Not reported. |

Source: ANAO analysis of Human Services information.

4.20 The information collected by Human Services (as outlined in Table 4.2) informed the department how often CDBS information had been accessed by customers and/or providers from a range of channels, but not how effective it was. Beyond 30 June 2014, Human Services did not collect information in regards to the communications strategy. Human Services advised the ANAO that an ad hoc report on program uptake generated during 2014 will be used to identify further communications needs and activities.

4.21 As discussed, there has been significantly lower than expected program uptake. In the circumstances, there would be benefit in Health evaluating the communication approach in consultation with Human Services. Focus areas could include the promotional and awareness raising activities and operational products adopted to date, with a view to improving engagement with the CDBS target population. Ongoing management of communication with customers (including areas of low uptake)52 would also benefit from the development of a revised communications strategy that specifies the implementation roles and responsibilities of each department and is supported by regular monitoring and reporting on the effectiveness of communications approaches in helping to achieve program objectives.

Recommendation No.2

4.22 In the context of low program uptake the ANAO recommends that Health, in consultation with Human Services:

- evaluate the approach to program communications, including the effectiveness of promotional and awareness raising activities adopted to date, with a view to improving engagement with the CDBS target population; and

- develop and promulgate a revised communications strategy that assigns clear implementation roles and responsibilities for each department and includes performance monitoring and reporting arrangements.

Department of Health’s response: Agreed.

Are claims processed accurately?

The ANAO’s analysis of claims made between 1 January 2014 and 1 May 2015 indicated that Human Services’ systems-based business rules and calculation of benefits provide reasonable assurance that claims are paid in accordance with program requirements.

4.23 Claims for CDBS services can be bulk billed or patient claimed. Customers or providers can submit electronic claims to Human Services via Medicare Online, Easyclaim, the Medicare Express Plus mobile application, in person or via mail. Human Services will pay the benefit once the service has been fully provided and a valid claim has been submitted.53

4.24 Whether a CDBS claim is entered manually by Service Officers or submitted electronically, it is processed and paid through Human Services’ Medicare claiming system.54 Claims are tested against the systems-based business rules, with manual intervention required to confirm that payment can be made if a systems-based business rule is not met.

Claiming data

4.25 Between 1 January 2014 and 1 May 2015, Human Services processed claims for 5.6 million dental services worth approximately $386 million in benefits. The ANAO’s testing indicated that approximately 90 per cent of claims were bulk billed.

4.26 The ANAO tested all claims processed during this period and identified that:

- all paid claims related to children who were eligible in the calendar year;

- the claiming limitations associated with items on the Dental Benefits Schedule were met in all processed claims55; and

- the benefit paid was equal to or less than the schedule amount in all processed claims.

4.27 The ANAO’s testing indicated that Human Services’ systems-based business rules and calculation of benefits provide reasonable assurance that CDBS claims are paid in accordance with program requirements.

Is there an adequate quality framework?

Human Services has incorporated a range of quality checking processes to mitigate the risk of administrative error in CDBS processes. The quality framework could be improved by incorporating regular monitoring and internal reporting of error rates for manual data matching processes, which are routinely applied to help reconcile data which cannot be matched through automated processes. The department should also establish performance indicators and benchmarks for manual processes.

4.28 Human Services has a Quality Framework which provides guidance to staff on quality assurance and quality control procedures. CDBS processing staff are also subject to the department’s standard quality control processes. As discussed, there is no systematic quality control procedure in place to assess the accuracy of the daily manual reconciliation of data exchanged between the department’s Centrelink and Medicare programs.56 Human Services advised the ANAO that a quality control process for manual reconciliation activities is being developed and will be introduced by November 2015.

4.29 Manual data reconciliation processes are a resource intensive and relatively costly intervention in program administration, which are intended to help maintain data integrity. As identified in other ANAO audit reports that reviewed manual data reconciliation processes in Human Services57, there is an increased risk of error, especially compared to automated processes. In developing a quality control process for manual data matching, Human Services should establish regular monitoring and reporting of error rates and determine performance indicators and benchmarks for matching errors. This approach would contribute to improved performance measurement and reporting and provide additional assurance on the quality of manual processes.

Recommendation No.3

4.30 To improve performance measurement and reporting and to provide assurance on the quality of manual data matching processes under the CDBS, the ANAO recommends that the Department of Human Services:

- establish performance indicators and benchmarks for manual processes; and

- introduce regular monitoring and internal reporting against the performance indicators.

Department of Human Services’ response: Agreed.

4.31 The department agrees with the recommendation. The department notes that 95 per cent of the customer records are automatically matched under the CDBS. Of the five per cent of records that require manual data matching, work has commenced to strengthen the quality assurance process. By the end of November 2015 a formal quality checking procedure will be introduced for a sample of the records that require manual matching. This procedure will include key performance indicators. Regular internal reports on manual data matching will also be developed for analysis and distribution to senior management.

Complaints and feedback

4.32 Customers can make a complaint or provide feedback on the CDBS through the Human Services website, by writing to Human Services or by calling the Customer Relations Unit. Information on making a complaint or providing feedback is detailed on the department’s website.58 Between January 2014 and May 2015, a total of 242 complaints were received relating to the CDBS. Of these, approximately 50 per cent of complaints related to: dissatisfaction with the information provided; program rules; decision making; and handling of a request.59 Data is collected on CDBS complaints through the Customer Feedback Tool and policy or legal complaints are escalated. A monthly report is distributed to senior management containing complaints relating to the CDBS.

4.33 To date, the majority of issues relating to CDBS program risks have been identified through provider and customer enquiries. Complaints, feedback and customer enquiries are recorded and managed as they are received, but the information is not analysed to identify systemic factors that may affect program administration. To enable process and engagement improvement, there would be value in Human Services identifying any emerging trends from the information received through complaints, feedback and customer enquiries.

Is there an adequate compliance framework?

Consistent with Human Services’ broader compliance strategy, the department has adopted a risk-based approach to managing compliance with the CDBS that is informed by analysis of program data. Compliance activity commenced during the course of this performance audit and it is therefore too early to determine whether the department’s approach has been effective.

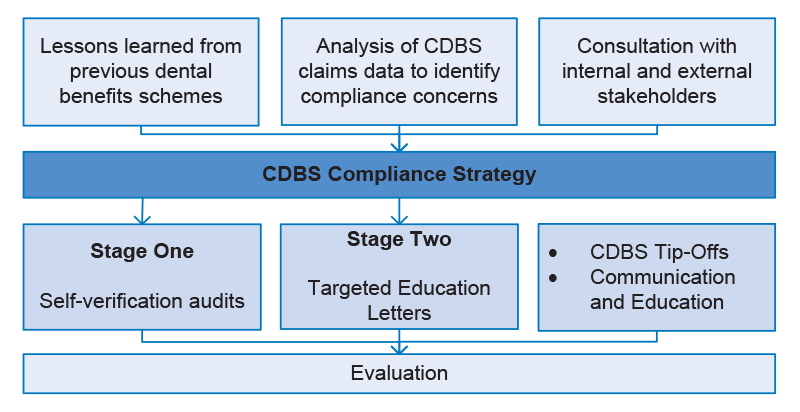

4.34 Compliance powers to support the operation of the CDBS were enacted in November 2014 through the Dental Benefits Legislation Amendment Act 2014.60 The department analysed CDBS claiming patterns to inform the development of a program-specific compliance strategy focussing on three areas of operational risk:

- non-compliance with legislative requirements;

- non-compliant/incorrect billing of CDBS services; and

- potential inappropriate practice by providing CDBS services which are not clinically relevant.61

4.35 The compliance strategy approved in November 2014 exclusively targeted private providers, on the basis that public provider eligibility beyond 2014 was subject to Ministerial determination. There would be value in the department reviewing its targeting of compliance activity, in light of the subsequent decision to extend public provider participation to June 2016 and given that approximately 18 per cent of CDBS services have been claimed by public providers.

4.36 The department has adopted a phased compliance approach to identify potentially non-compliant providers. The approach includes: analysis of claiming patterns; investigation of complaints; and auditing of providers’ documentation. The first stage of compliance activity commenced in May 2015, with self-verification audits issued to 188 providers.62 Human Services advised that it intends to issue a further 78 providers with targeted letters addressing potential inappropriate practice. The department’s approach to managing compliance under the CDBS is outlined in Figure 4.2.

Figure 4.2: Compliance framework for the CDBS

Source: ANAO analysis of Human Services information.

4.37 To support its compliance activity, Human Services developed a communication and education strategy to inform providers about the compliance framework. While the compliance strategy was approved in November 2014, implementation of the strategy has been significantly delayed with many of the activities commencing in June 2015. Human Services also developed a process for responding to CDBS tip-offs, with a total of 47 tip-offs received by July 2015. As at July 2015, a total of 38 provider debts had been raised through compliance activity to the value of approximately $28 000.63

4.38 Timely evaluation of the CDBS compliance approach, as provided for in the compliance strategy, will enable Human Services to assess the overall impact and effectiveness of compliance activities and inform the future direction of the strategy.

5. Program outcomes

Areas examined

This chapter examines the Department of Health’s (Health) and the Department of Human Services’ (Human Services) approach to performance monitoring and reporting on the Child Dental Benefits Schedule (CDBS).

Conclusion

Despite an expansion of the eligibility criteria and services offered through the CDBS, only around 30 per cent of eligible children claimed benefits in 2014 and 2015, resulting in a substantial underspend of program funds and a risk that program outcomes and objectives may not be realised. The completion of the first two years of the program in December 2015 is an appropriate point for Health to take stock.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has made one recommendation to the Department of Health to assist management in assessing the achievement of program objectives.

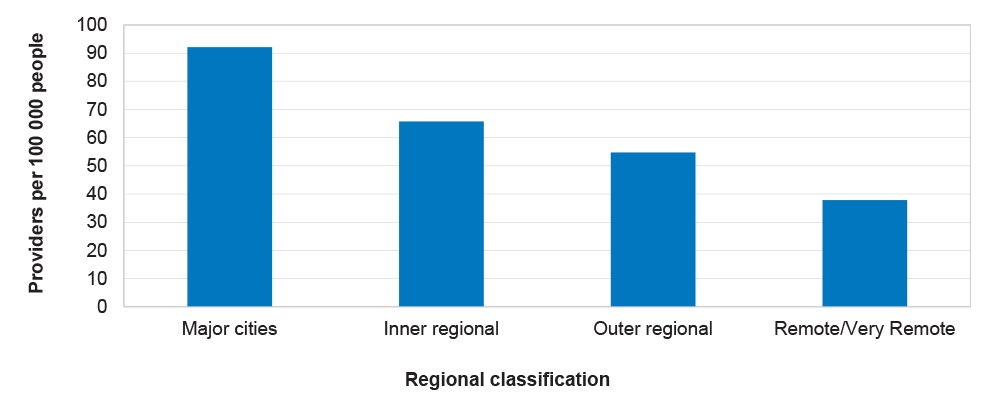

The department could also consider the implications of workforce distribution as part of its evaluation of drivers behind low program uptake.

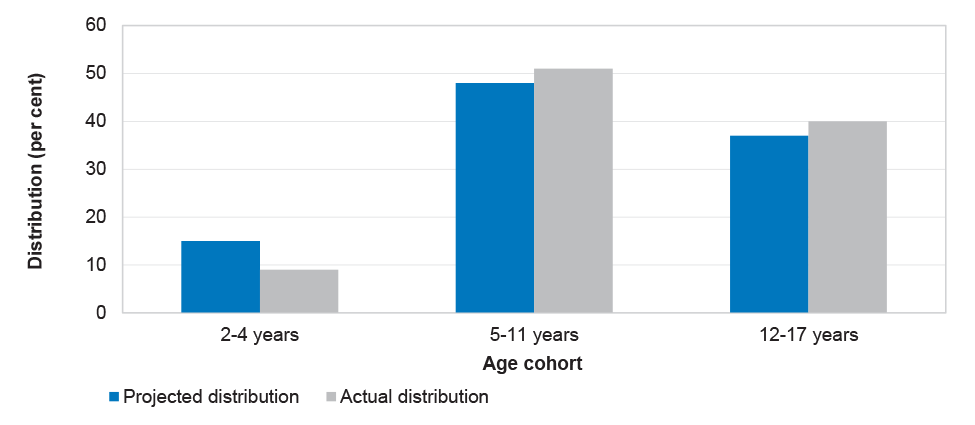

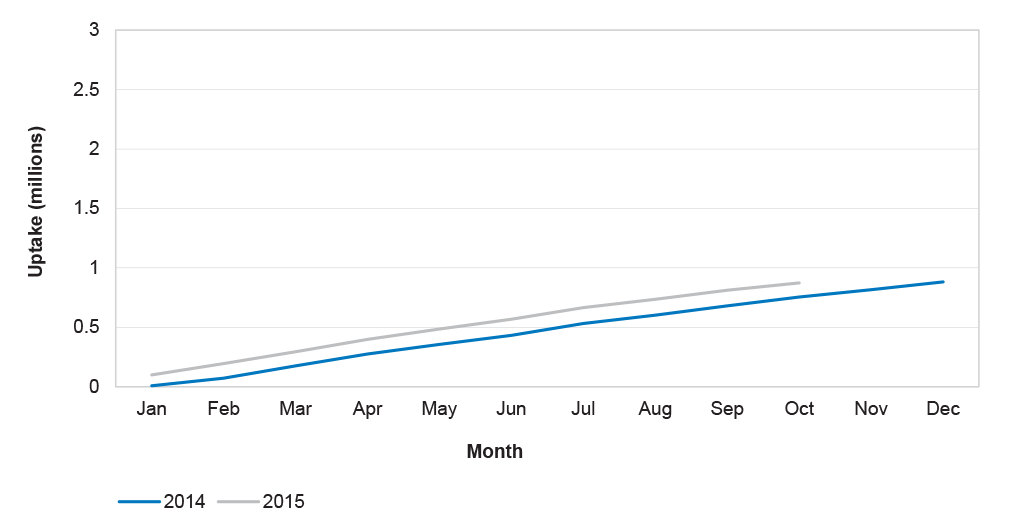

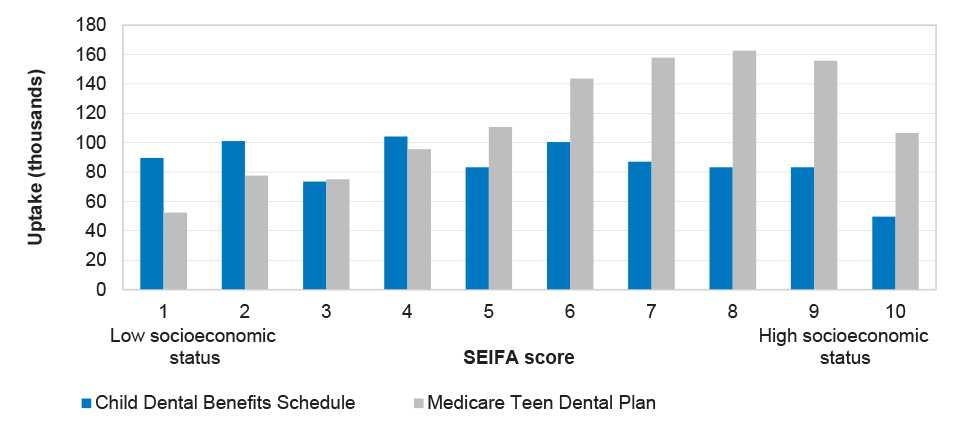

Introduction