Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of the Australian Apprenticeships Incentives Program

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the (former) Department of Industry’s administration of the Australian Apprenticeships Incentives Program.

Summary

Introduction

1. Australia’s vocational education and training (VET) system is designed to help individuals develop or enhance workplace skills and knowledge. Supporting people to develop workplace skills is a key factor in improving productivity and workforce participation, and plays a central role in strengthening economic and social wellbeing.1

2. Apprenticeships and traineeships—hereafter referred to as Australian Apprenticeships—are an important component of Australia’s VET system. An Australian Apprenticeship is an employment arrangement that combines paid work with a structured program of ‘on-the-job’ and ‘off-the-job’ training. Australian Apprenticeships enable employees to gain experience, develop practical skills and acquire nationally-recognised qualifications. As at 30 June 2014, there were approximately 351 000 apprentices and trainees ‘in-training’.2 Of these, approximately 55 per cent were classified as technicians and trades workers.3

3. The Australian Government has a number of programs in place to support Australia’s VET system, and Australian Apprenticeships in particular. The largest component of the Australian Government’s financial support for Australian Apprenticeships is the Australian Apprenticeships Incentives Program (AAIP).

Australian Apprenticeships Incentives Program

4. The objective of the AAIP, which commenced in 19984, is to contribute to the development of a highly skilled and relevant Australian workforce that supports economic sustainability and competitiveness. The Australian Government aims to achieve this objective by:

- providing genuine opportunities for skills-based training and development of employees by providing incentives to employers of eligible apprentices; and

- encouraging people to enter into skills-based training through an Australian Apprenticeship by providing personal benefits.5

5. A key part of the AAIP is the delivery, under contract to the Australian Government, of Australian Apprenticeships Support Services (Support Services) by Australian Apprenticeships Centres (AACs). Since the AAIP commenced, there have been five separate contract rounds for the delivery of Support Services—the current round commenced on 1 July 2012 and is scheduled to end on 30 June 2015.6 A broad range of Support Services are required to be provided in the current contract round, including: assessing the eligibility of applications and claims for financial assistance under the AAIP; providing information and advice to potential applicants; and marketing and promoting Australian Apprenticeships. The AACs are paid a fee for each Australian Apprenticeship that they administer as part of delivering the Support Services.

6. In September 2014, the then Minister for Industry—now the Minister for Industry and Science—announced the establishment of the Australian Apprenticeships Support Network (Support Network) to replace the current round of Support Services from 1 July 2015. At the time, the then Department of Industry’s website noted that:

the Support Network [is designed to] make it easier for employers to recruit, train and retain apprentices and better support individuals in a proven earning and learning pathway, helping improve completion rates.7

7. To the end of December 2014, total AAIP expenditure in the current Support Services contract round has been approximately $2.8 billion—$2.3 billion in financial assistance and $0.5 billion in fees paid to AACs.8

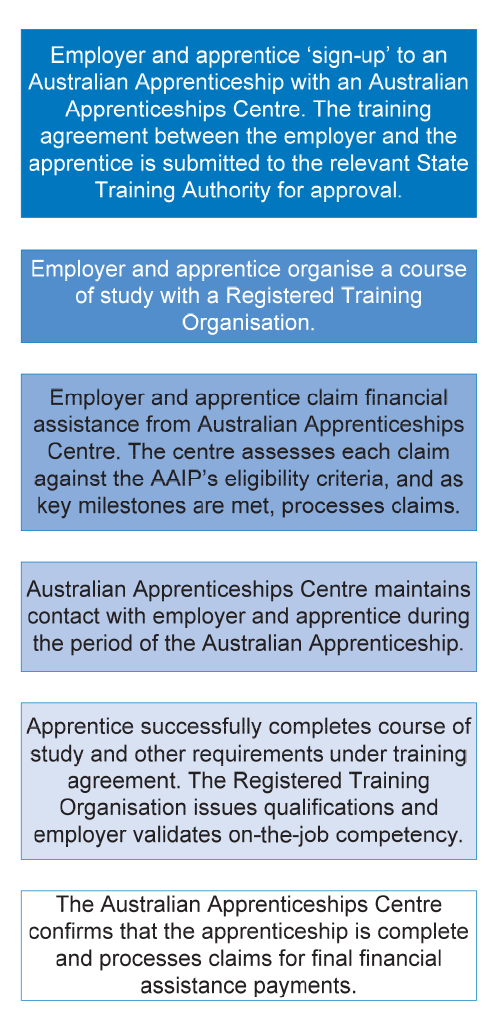

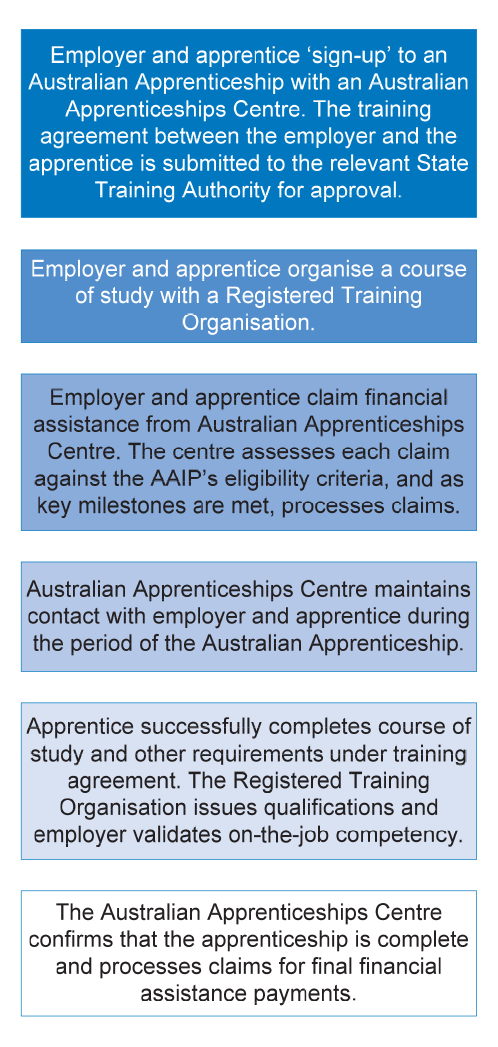

8. The key steps involved in the life of an Australian Apprenticeship are shown in Figure S.1.

Figure S.1: Key steps in an Australian Apprenticeship

Source: ANAO, adapted from A shared responsibility. Apprenticeships for the 21st Century, Final Report of the Expert Panel. January 2011.

Administrative arrangements

9. In December 2011, responsibility for the administration of the AAIP was transferred from the former Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR) to the then Department of Industry, Innovation, Science, Research and Tertiary Education (DIISRTE). As part of further changes to its responsibilities, the department was renamed twice during 2013: in March 2013, to the Department of Industry, Innovation, Science, Climate Change, Research and Tertiary Education (DIICCSRTE); and in September 2013, to the Department of Industry (Industry). On 23 December 2014, the Australian Government transferred responsibility for the administration of the AAIP from Industry to the newly established Department of Education and Training (Education and Training).9 At the same time, Industry was renamed the Department of Industry and Science.

10. Apart from references to activity prior to December 2011, the discussion of audit findings in this audit report refers to Industry—the administering department’s name at the time of the audit. However, the audit recommendation and other suggestions for improvement made in the report have been addressed to Education and Training, the responsible department at the time of preparing the audit report.

Audit objectives, criteria and scope

11. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of Industry’s administration of the AAIP. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- an effective governance framework for the AAIP has been implemented and Industry provided suitable guidance, processes and tools to support the AACs to effectively deliver AAIP services;

- suitable contractual arrangements, including sound contract management practices, were in place to support service delivery by the AACs and overall program management by Industry; and

- appropriate program management, performance monitoring and reporting structures were in place and used to inform the administration of the AAIP.

12. The audit focussed on arrangements in place since 1 July 2012—the commencement of the current round of Support Services contracts. The ANAO examined relevant AAIP documentation, including a sample of contracts between the Australian Government and the AACs, and conducted interviews with key staff from Industry and a selection of AACs. The ANAO also analysed data from the Training and Youth Internet Management System (TYIMS).10

13. The audit did not examine the management of individual Australian Apprenticeships or of the AACs. In addition, the audit did not examine the procurement undertaken by the then DEEWR in 2011–12 to establish the current round of contracts, nor the procurement undertaken by Industry to establish the Support Network.

14. The AAIP was previously audited by the ANAO in Audit Report No.9 2007–08, Australian Apprenticeships. That audit assessed the effectiveness of the former Department of Education, Science and Training’s (DEST) administration of its role in Australian Apprenticeships. The audit found that the program was appropriately used by employers, that financial assistance payments to employers were accurate, and that contract management practices were sound.11 The audit did however identify an opportunity to improve performance monitoring and evaluation activities and recommended (Recommendation No.2) that DEST:

- analyse program usage by employers of apprentices and trainees in occupations in national demand; and

- perform a sensitivity analysis of incentives payments to employers compared with Australian Apprenticeships completions.12

15. The current audit examined whether the two parts of the recommendation have been implemented.

Overall conclusion

16. Administered by the Department of Industry (Industry) at the time of the audit13, the Australian Apprenticeships Incentives Program (AAIP) aims to contribute to the development of a highly skilled and relevant workforce by providing financial incentives to support employers and apprentices undertake Australian Apprenticeships. A key component of the program is the delivery of Australian Apprenticeships Support Services (Support Services) under contract by Australian Apprenticeships Centres (AACs). The current contract round commenced on 1 July 2012, and is scheduled to end on 30 June 2015. To the end of December 2014, total AAIP expenditure in the current contract round has been approximately $2.8 billion—comprising $2.3 billion in financial assistance grants and $0.5 billion in fees paid to the AACs.

17. Overall, Industry’s administration of the AAIP in the current Support Services contract round was generally effective.14 Appropriate contract and program management arrangements were largely in place, and operating as intended. Notably, Industry’s processes for monitoring the performance of the contracted service providers (the AACs), including arrangements for assessing AACs’ compliance with contractual requirements, were soundly-based and well-targeted. The majority of AACs were performing reasonably well against most performance measures, and over the two completed years of the current contract round, the combined total of reported employers and apprentices assisted by the AAIP has been in-line with Industry’s targets.15 Generally, AAIP payments made from 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2014 examined by the ANAO accorded with the program’s eligibility criteria and related policy conditions. Nonetheless, the audit highlighted some opportunities to further strengthen the AAIP’s management and oversight arrangements. This includes more regular data analysis to help assess the integrity of apprenticeship records and identify incorrect payments, and the development of a structured evaluation framework to help assess the program’s performance against its policy objective and intended outcomes.

18. In the current contract round, Industry implemented relevant contract and program management arrangements and practices, which contributed to the overall effectiveness of the delivery of the AAIP and the Support Services. These arrangements included:

- fit-for-purpose contracts with the AACs, including clear service delivery requirements and performance measurement arrangements;

- a multi-faceted and well-targeted approach to monitoring the activities of the AACs, including assessing compliance against contractual requirements. A central part of these monitoring activities was a structured approach to assessing the validity of AACs’ eligibility assessments;

- generally well-designed risk management arrangements, including processes for assessing and managing the risks associated with fraud and conflicts of interest; and

- well-founded and instructive internal management reporting arrangements.

19. Industry’s internal performance measurement and reporting arrangements provided departmental management with a range of useful and relevant information. In particular, the program’s performance measures included a useful mix of intermediate and proxy targets. However, these measures did not enable a complete assessment of the extent to which the AAIP is achieving its objective or intended outcomes. Further, Industry did not put in place an evaluation plan for the AAIP, and had not, at the time of the program’s transfer to Education and Training, conducted a formal evaluation of the effectiveness or performance of the AAIP during the current contract round. A program of structured evaluation activity would assist Education and Training to better assess the AAIP’s performance.

20. The ANAO’s examination of AAIP-related records in the Training and Youth Internet Management System (TYIMS) identified shortcomings in record-keeping arrangements, as well as some 960 incorrect financial assistance payments with a value of approximately $970 000.16 Although the incorrect payments identified are financially immaterial—representing less than 1 per cent of total program expenditure in the period 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2014—the results suggest that there would be benefit in regularising data analysis activities and upgrading data matching and validation functions.

21. The ANAO has made one recommendation to Education and Training aimed at improving the evaluation framework for AAIP, noting that well-designed monitoring and review arrangements can assist entities, and other interested stakeholders, make informed assessments about a program’s progress and relative contribution towards its intended outcomes and expected benefits.

Key findings by chapter

Program Management (Chapter 2)

22. The risk assessments maintained by Industry relating to the administration of the AAIP covered a broad range of risks and controls. Most risks were described in sufficient detail so as to be informative, and for the most part, the controls and treatments listed in the assessments were suitable and appropriate. However, a particular shortcoming was that no controls were documented for one of the identified risk events—which was focussed on false information provided in relation to eligibility criteria—and there would be benefit in doing so.17 The accuracy and suitability of the risk assessments related to the AAIP could be further enhanced by strengthening arrangements for monitoring and review. A structured program of review can help confirm the ongoing accuracy of the identified risks, and contributes to an assessment of whether risk mitigation measures are well-targeted and operating as intended.

23. Under their contracts with the Australian Government, the AACs are required to develop and maintain a risk management plan (RMP) and a conflict of interest management plan (COIMP). The ANAO’s analysis of a sample of COIMPs showed that most contained practical strategies and relevant processes—including clear accountabilities—for dealing with conflict of interest situations. However, the ANAO identified some variation in the quality and relevance of the AACs’ RMPs. In particular, many of the plans examined only outlined the AAC’s risk management policy (without identifying specific risks) or identified risks not tailored to the services being delivered. Education and Training advised that it would encourage greater consistency in the form and content of the RMPs into the future, by providing guidance to the providers engaged in the delivery of the Support Network. There would also be merit in Education and Training examining ways to gain assurance of the continued effectiveness and operation of the service providers’ RMPs.

24. Industry did not assess whether the AAIP was affected by amendments to the former Financial Management and Accountability Regulations in May 2013, which altered the definition of a grant. Following the ANAO’s enquiries, Industry established that the AAIP was a grants program, according to the new definition, and then acted in a timely manner to consider the application of the Australian Government’s grants administration framework18 to the program.

25. Industry had a range of well-designed and informative guidance and support arrangements in place to assist staff and the AACs administer the program. In addition, the department had well–established internal performance monitoring and reporting arrangements for the AAIP, providing managers with access to a range of useful and relevant information to assist their oversight of the program. In large part, however, the AAIP’s Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) are designed to measure the program’s outputs, and not the program’s outcomes. In this context, a number of the performance measures are akin to intermediate19 and proxy20 performance measures. While these measures afford some useful insights about the performance of the program they do not enable the administering department, or other interested stakeholders to assess the extent to which the AAIP is achieving its overall objectives.

26. Industry did not have an evaluation plan in place for the AAIP, and had not, at the time of this audit, conducted a formal evaluation of the AAIP in the current contract round.21 To enable greater insights into the effectiveness of the AAIP, including the performance of the program against its objective, Education and Training would benefit from implementing a program of evaluation activities for the AAIP. The development of a structured evaluation program in the context of Education and Training’s new approach to service delivery—the Support Network—would be particularly timely.

27. Industry and its predecessor departments largely addressed the intent of Recommendation No.2 from the ANAO‘s 2007 audit of the AAIP (see paragraph 14). Industry advised the ANAO that in light of changes to employer incentive rules in 2011 and 2012, it had decided to discontinue conducting sensitivity analysis of incentive payments and apprenticeship completions—which was related to the second part of the recommendation in the 2007 ANAO report.

Managing Delivery of Australian Apprenticeships Support Services (Chapter 3)

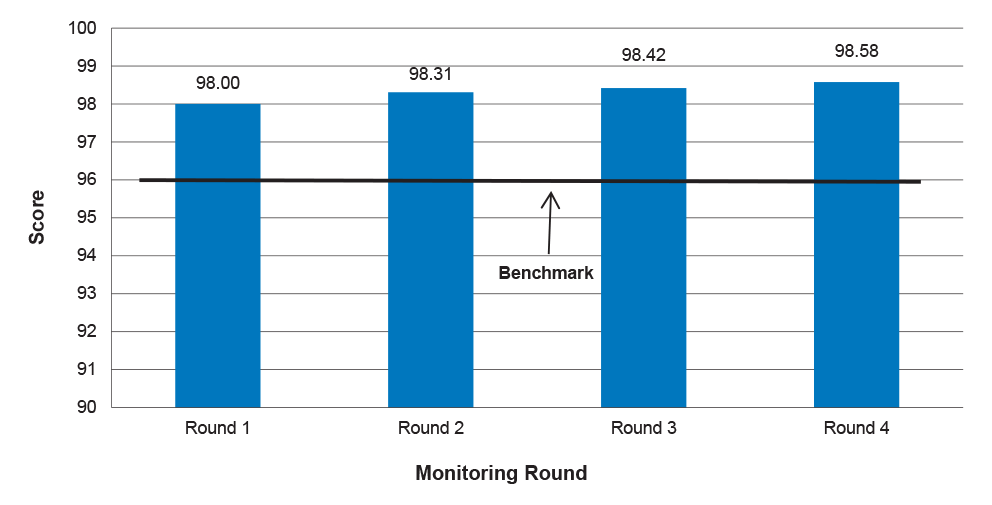

28. The contracts with the AACs are fit-for-purpose and contain terms and conditions consistent with better practice.22 In particular, the key service requirements are clear, and the five key performance indicators (KPIs) and 15 performance measures are useful to help assess the AACs’ performance against those requirements. However, most of the benchmarks associated with two of the five KPIs are based on information dating from 31 December 2010. The moderate (and growing) time-difference between the date of the data used to set the benchmarks, and the dates of the actual assessments of the AACs’ performance, affects the usefulness and reliability of these measures.

29. Industry adopted a multi-faceted and well-targeted approach to monitoring the performance of the AACs, which examined key areas of the AACs’ service delivery policies, practices and decision-making. In this context, Industry’s performance monitoring included arrangements for assessing the AACs’ compliance with contractual requirements, including requirements relating to the assessment of eligibility. The ANAO’s analysis indicated that, for the most part, Industry’s performance monitoring processes were operating as intended.

30. Monitoring undertaken by Industry indicated that the majority of AACs were performing reasonably well against most performance targets. In particular, the results indicated that there had been a general improvement in the quality of the AACs’ administration. In addition, the majority of AACs were meeting targets associated with the majority of measures relating to apprenticeship commencement and completion measures—measures relevant for analysing achievement against the program’s outcomes. On the other hand, the majority of AACs were not meeting benchmarks for most measures relating to apprenticeship retention rates. Industry advised that a number of external factors were likely to have affected performance in relation to retention rates, including a downturn in economic conditions and the associated tighter labour market.

31. The ANAO’s analysis indicated that the controls in place to protect the confidentiality and integrity of data in TYIMS were largely operating as intended. Furthermore, the fee-for-service (FFS) and financial assistance expenditure during the period 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2014 examined by the ANAO was materially correct. However, as outlined in Table S.1, the ANAO’s analysis of nearly 920 000 financial assistance payment records, worth approximately $1.2 billion, identified some 960 incorrect payments, albeit with a relatively low value (almost $970 000) compared to overall program expenditure.

Table S.1: Incorrect financial assistance payments during 1 July 2012 and 30 June 2014 identified by ANAO analysis

|

Category |

Number |

Amount ($) |

|

Ineligible or overpaid financial assistance |

468 |

621 432 |

|

Duplicate records resulting in overpaid financial assistance |

232 |

214 885 |

|

Assessment error—underpayment of financial assistance |

259 |

131 194 |

|

Total errors A |

959 |

967 511 |

Source: ANAO analysis.

Note A: The value of the actual payment errors identified by the ANAO is financially immaterial—representing less than 1 per cent of total financial assistance expenditure recorded in TYIMS for the period 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2014. At the time of this report, Education and Training was investigating a further four financial assistance payments with a value of $6 700 that were also potentially paid incorrectly.

32. The ANAO identified a number of further inaccuracies among the data recorded in TYIMS. Most significantly, the ANAO found:

- more than 27 600 apprentice records that are potentially duplicated; and

- around 2 500 payment records containing invalid Australian Business Numbers (ABNs).

33. During the audit, Industry advised that it was examining ways of ‘cleaning’ the data in TYIMS, including merging duplicate records, prior to migrating data from TYIMS to the proposed replacement system—the Australian Apprenticeship Management System (AAMS).23 Further, Industry advised that the data matching and validation functionality in AAMS would be more robust than TYIMS. In addition, to further strengthen the department’s monitoring and compliance activities and help assure the continued accuracy and integrity of program expenditure, there would be merit in Education and Training examining options to regularise data analysis and data mining activities in relation to the AAIP. The design of a program of data analysis could focus on areas of higher risk and exposure to fraud.

Summary of entity responses

34. Education and Training, and Industry and Science each provided responses to the proposed audit report. A summary of these responses is below, with the full responses provided in Appendix 1.

Education and Training

The Department of Education and Training (the department) is committed to providing targeted and relevant investment in training to ensure the development of a more skilled Australian workforce that delivers long−term benefits for our nation and our international competitiveness.

The rigorous administration of the Australian Apprenticeships Incentives Program by the department has been acknowledged by the ANAO in its identification of optimal or “better practice” measures in contractual terms and conditions including performance monitoring as well as operating guidance materials.

The department will implement a program of structured evaluation activity as recommended.

The department has already implemented, or is intending to implement, many of the suggestions contained in this report including those relating to risk assessments at the program and provider levels.

The department is committed to better practice in the delivery of the Australian Apprenticeships Incentives Program.

Industry and Science

I am pleased that the ANAO has found that the overall administration of the AAIP has been generally effective. The audit finding that appropriate contract and program management arrangements were in place and that performance monitoring processes were soundly-based and well-targeted is positive.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 2.62 |

To assist the Department of Education and Training better assess the efficiency and effectiveness of the Australian Apprenticeships Incentives Program, including performance against the program’s policy objective, the ANAO recommends that the department implement a program of structured evaluation activity. Education and Training’s response: Agreed. |

1. Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the Australian Apprenticeships Incentives Program, as well as the audit objective and approach.

Introduction

A skilled and flexible workforce … will be critical to Australia’s future standard of living.24

1.1 Australia’s vocational education and training (VET) system is designed to help individuals develop or enhance workplace skills and knowledge. Supporting people to develop workplace skills is a key factor in improving productivity and workforce participation, and plays a central role in strengthening economic and social wellbeing.25

1.2 Apprenticeships and traineeships26, hereafter referred to as Australian Apprenticeships, are an important component of Australia’s VET system. In June 2013, approximately 25 per cent of students enrolled in the VET system were associated with an Australian Apprenticeship.27 An Australian Apprenticeship is an employment arrangement that combines paid work with a structured program of ‘on-the-job’ and ‘off-the-job’ training. Australian Apprenticeships enable employees to gain experience, develop practical skills and acquire nationally-recognised qualifications. As at 30 June 2014, there were approximately 351 000 apprentices and trainees ‘in-training’.28 Of these, approximately 55 per cent were classified as technicians and trades workers.29

1.3 Australian Apprenticeships are managed under the terms of a training agreement between an employer and the apprentice. Among other things, training agreements are required to set out the employer’s obligations relating to training, and the qualifications to be obtained by the apprentice. The effectiveness of an Australian Apprenticeship is shaped by the employer’s and the apprentice’s level of commitment to the success of, and the outcomes from, the agreement. In this regard, the Australian Government has published a ‘Code of good practice for Australian Apprenticeships’ to help employers and apprentices better understand their obligations and expectations.30

1.4 The Australian Government has a number of programs in place to support Australia’s VET system, and Australian Apprenticeships in particular. The largest component of the Australian Government’s financial support for Australian Apprenticeships is the Australian Apprenticeships Incentives Program (AAIP).

Australian Apprenticeships Incentives Program

1.5 The AAIP commenced in 1998—at that time it was known as the Commonwealth Incentives Programme, before being renamed the New Apprenticeships Incentives Programme. Since 1998 there have been a number of adjustments and refinements to the range of incentives available in relation to Australian Apprenticeships. Fundamentally, however, the aims and structure of the AAIP have broadly remained unchanged.31

1.6 The objective of the AAIP is to contribute to the development of a highly skilled and relevant Australian workforce that supports economic sustainability and competitiveness. The Australian Government aims to achieve this objective by:

- providing genuine opportunities for skills-based training and development of employees by providing incentives to employers of eligible apprentices; and

- encouraging people to enter into skills-based training through an Australian Apprenticeship by providing personal benefits.32

Australian Apprenticeships Support Services

1.7 A key part of the AAIP is the delivery of a broad range of services relating to Australian Apprenticeships—known as the Australian Apprenticeships Support Services (Support Services). The Support Services are delivered under contract by a cohort of organisations, known as Australian Apprenticeships Centres (AACs). Since 1998, there have been five separate contract rounds for the delivery of Support Services:

- Round one—1 May 1998 to 30 November 1999;

- Round two—1 December 1999 to 30 June 2003;

- Round three—1 July 2003 to 30 June 2006;

- Round four—1 July 2006 to 30 June 2012; and

- Round five—1 July 2012 to 30 June 2015.33

1.8 For the fifth contract round, the Australian Government entered into 72 contracts with 23 different organisations to provide services at around 300 sites across Australia.34 During the current contract round, approximately 1 000 people were engaged by the AACs to deliver Support Services. In the fifth contract round, the Support Services include:

- providing information, advice and support to employers and apprentices;

- working towards improving apprenticeship participation rates in the key priority groups—Indigenous Australians; people with a disability; school-based apprentices; mature age workers; and occupations identified as having a ‘skill need’;

- undertaking a range of promotion and marketing activities;

- maintaining effective working relationships with key stakeholders (such as State Training Authorities, Registered Training Organisations and Group Training Organisations);

- assessing the eligibility of applications and claims for incentives and personal benefits; and

- processing applications and claims for financial assistance in the Training and Youth Internet Management System (TYIMS) accurately and in a timely manner.35

1.9 In September 2014, the then Minister for Industry—now the Minister for Industry and Science—announced the establishment of the Australian Apprenticeships Support Network (Support Network) to replace the Support Services from 1 July 2015. On 21 October 2014, the former Department of Industry released a Request for Tender (RFT) for the establishment of the Support Network. The Australian Government’s online Tender System, AusTender, stated that:

The new [Support Network] arrangement aims to:

- simplify and improve user access to and engagement with the Australian Apprenticeships system by establishing Network Providers as hubs for the delivery of quality end-to-end advice and Support Services to Australia’s apprentices and their employers;

- improve apprenticeship completion and satisfaction rates through the provision of new services designed to deliver integrated, targeted support to apprentices and employers prior to commencement and while they are in-training;

- provide services to assist individuals to find the right VET or employment pathway for them; and

- reduce red tape and the administrative burden on providers, stakeholders and system users, particularly employers.36

1.10 At the time of preparing this report, the successful tenderers had not been announced.

Types of financial assistance

1.11 Table 1.1 shows the categories of financial assistance available to eligible employers and apprentices under the AAIP in the current contract round.

Table 1.1: Categories of financial assistance available under the AAIP

|

Financial assistance |

|

To employers |

|

Commencement incentive |

|

Recommencement incentive |

|

Completion incentive |

|

Rural and Regional Skills Shortage incentive |

|

Group Training Organisations Certificate II Completion incentive |

|

Declared Drought Area incentive |

|

Mature Aged Workers incentive |

|

Australian School-based Apprenticeship incentive |

|

Assistance for Australian Apprentices with a Disability |

|

Support for Adult Australian Apprentices (employer component) |

|

To apprentices |

|

Tools for Your Trade A |

|

Living away from home allowance |

|

Support for Adult Australian Apprentices (apprentices component) B |

Source: ANAO analysis.

Note A: Tools for Your Trade payments were replaced by the Trade Support Loans scheme from 1 July 2014.

Note B: The Australian Government announced in the 2014–15 Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook Statement that the financial assistance to apprentices under Support for Adult Australian Apprentices would cease from 1 July 2015.

Eligibility criteria

1.12 The provision of the incentives and personal benefits available under the program is subject to employers and apprentices satisfying the AAIP’s eligibility criteria. As shown in Table 1.2, there are two broad categories of eligibility criteria—the primary and targeted criteria. The primary criteria are common to all incentives and personal benefits, while the targeted criteria determine the level of certain payments.

Table 1.2: AAIP primary and targeted eligibility criteria

|

CriteriaA |

Description |

|

Primary |

|

|

Employment and Training |

The apprentice must be employed within Australia under an approved training agreement, and be undertaking accredited training leading to a nationally recognised qualification. |

|

Citizenship |

The apprentice must be: an Australian citizen; a foreign national with permanent residency status; or a New Zealand passport holder resident in Australia for at least six months. |

|

Existing Worker |

Existing workers must have an employment relationship with their employer for more than three full-time equivalent months. |

|

Previous or Concurrent Qualifications |

Eligibility may be affected by previous or concurrent qualifications, including the level and occupational outcome of the other qualification and when it was undertaken. |

|

Waiting Period |

A waiting period applies to all incentive payments. The waiting period is the greater of three months from date of commencement or recommencement, or the probationary period specified by the State or Territory Training Authority. |

|

Time Limits |

Time limits for lodging applications and claim forms apply to all payments. Typically, 12 months is allowed for claims to be lodged. |

|

Targeted |

|

|

Occupations on the National Skills Needs List (NSNL) |

Additional incentive and personal benefit amounts are payable where the apprentice is working towards an occupational outcome identified on the NSNL. |

|

Custodial apprentices |

Separate rules are in place to enable custodial apprentices (as defined) to access a range of incentives and personal benefits. |

|

Nominated Equity Groups |

A separate commencement incentive is available for employers of apprentices in one of six nominated equity groups who are undertaking a Certificate II qualification. |

Source: ANAO analysis, based on the AAIP Program Guidelines.

Note A: Over the course of the current contract round, there have been a number of policy changes that have affected the AAIP’s eligibility criteria. During the audit, Industry advised the ANAO that these policy changes represented efforts by the Australian Government to rationalise the level and type of support available to the Australian Apprenticeships system from the AAIP, and in particular, to better target and prioritise the funding available to more effectively support Australia’s skills needs. Appendix 3 contains a summary of these policy changes.

Note B: The NSNL was developed by the former Department of Education, Employment, and Workplace Relations to help ensure that incentives were directed towards occupations experiencing persistent skill shortages.

1.13 The key steps in the life of an Australian Apprenticeship under the AAIP are shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Key steps in an Australian Apprenticeship

Source: ANAO, adapted from A shared responsibility. Apprenticeships for the 21st Century, Final Report of the Expert Panel. January 2011.

AAIP financial and performance information

1.14 To the end of December 2014, total AAIP expenditure in the current Support Services contract round has been approximately $2.8 billion—$2.3 billion in financial assistance and $0.5 billion in fees paid to AACs. A breakdown of estimated and actual AAIP expenditure in each year of the current contract round is shown in Appendix 2.

Administrative arrangements

1.15 In December 2011, responsibility for the administration of the AAIP was transferred from the former Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR) to the former Department of Industry, Innovation, Science, Research and Tertiary Education (DIISRTE). As part of further changes to its responsibilities, the department was renamed twice during 2013: in March 2013, to the Department of Industry, Innovation, Science, Climate Change, Research and Tertiary Education (DIICCSRTE); and in September 2013, to the Department of Industry (Industry). On 23 December 2014, the Australian Government transferred responsibility for the administration of the AAIP from Industry to the newly established Department of Education and Training (Education and Training).37 At the same time, Industry was renamed the Department of Industry and Science.

1.16 Apart from references to activity prior to December 2011, the discussion of audit findings in this audit report refers to Industry—the administering department’s name at the time of the audit. However, the audit recommendation and other suggestions for improvement made in the report have been addressed to Education and Training, the responsible department at the time of preparing the audit report.

Previous audit activity

1.17 The AAIP was previously audited by the ANAO in Audit Report No.9 2007–08, Australian Apprenticeships. The earlier audit assessed the effectiveness of the former Department of Education, Science and Training’s (DEST) administration of its role in Australian Apprenticeships, including, whether it:

- monitored whether Australian Apprenticeships was achieving its objectives; and

- effectively managed the AAIP, including the contracts with the AACs.

1.18 The audit found the program was appropriately used by employers, payments were accurate, and contract management practices were sound. However, the audit did identify some limitations in relation to performance monitoring and evaluation activities. The audit report made two recommendations, one of which (Recommendation No.2) is relevant to the current audit—that the administering department improve performance monitoring and reporting processes by:

- analysing program usage by employers of apprentices and trainees in occupations in national demand; and

- performing sensitivity analysis of incentives payments to employers compared with Australian Apprenticeships completions.

Audit objective, criteria, scope and methodology

Audit objective and criteria

1.19 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of Industry’s administration of the AAIP. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- an effective governance framework for the AAIP had been implemented and Industry provided suitable guidance, processes and tools to support AACs to effectively deliver AAIP services;

- suitable contractual arrangements, including sound contract management practices, were in place to support service delivery by AACs and overall program management by the department; and

- appropriate program management, performance monitoring and reporting structures were in place and used to inform the administration of the AAIP.

Audit scope

1.20 The audit focused on arrangements in place since 1 July 2012—the commencement of the current Support Services contract round. In particular, the audit examined:

- arrangements for governing the delivery of the AAIP;

- processes for oversighting the AACs;

- guidance, practices and assurance mechanisms in place to support the:

- assessment of employers’ and apprentices’ eligibility for incentives and personal benefits; and

- accurate and complete payment of those incentives and personal benefits;

- performance management and reporting practices, including whether Industry captured information about the success of the program in terms of its objective; and

- the extent of the implementation of Recommendation No.2 in ANAO Audit Report No.9 2007–08.

Out of scope

1.21 The following aspects are not in scope for the current audit:

- an assessment of individual training agreements between apprentices and employers;

- an examination of the procurement exercise conducted by the then DEEWR in 2011–12 to set up the current round of contracts with the AACs;

- an examination of the procurement exercise conducted in 2014–15 to set up the Support Network round of contracts;

- an examination of the AACs’ operations—other than through review of Industry’s records, including copies of performance reports provided to Industry; and

- the administration of the Trade Support Loans (TSL) scheme.

Audit methodology

1.22 The audit methodology included: the examination of relevant AAIP policy and operational documents; an analysis of the results of performance monitoring activities for the current contract round of Support Services; an analysis of data extracted from TYIMS; and an assessment against relevant requirements of the Australian Government’s financial management framework. In addition, the ANAO held discussions with staff in Industry’s national office as well as three of Industry’s state contract managers; as well as with representatives from six AACs.

1.23 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO’s Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $449 000.

Structure of the Audit Report

1.24 The structure of the audit report is shown in Table 1.3.

Table 1.3: Structure of the Audit Report

|

Chapter |

Description |

|

Introduction |

Provides an overview of the Australian Apprenticeships Incentives Program, as well as the audit objective and approach. |

|

Program Management |

Examines aspects of the program management arrangements established for the Australian Apprenticeships Incentives Program, including the tools and processes in place to support consistent and appropriate decision-making. |

|

Managing Delivery of Australian Apprenticeships Support Services |

Examines Industry’s management of the delivery of Australian Apprenticeships Support Services during the current contract round, including controls and processes for managing the performance of the Australian Apprenticeships Centres. |

Source: ANAO.

2. Program Management

This chapter examines aspects of the program management arrangements established for the Australian Apprenticeships Incentives Program, including the tools and processes in place to support consistent and appropriate decision-making.

Introduction

2.1 Delivering the Australian Government’s programs and services is one of the key responsibilities of government entities. In achieving the Government’s intended outcomes, public sector entities have to deal with a range of complex challenges. Some of the contemporary challenges include: the need to continually innovate and manage risks; engaging constructively with interested stakeholders and, in some cases, the broader community; and, as necessary, collaborating with other entities, including across jurisdictional and sectoral boundaries. Within this context, effective program management arrangements and practices contribute to sound, sustainable and accountable program and service delivery performance.38

2.2 Typically, effective program management arrangements include: robust risk assessment and monitoring arrangements; clear planning and program documentation; well-targeted. operating procedures; accurate and informative guidance material; and ongoing monitoring and reporting of performance.

2.3 To evaluate the effectiveness of the Australian Apprenticeships Incentives Program’s (AAIP) program management arrangements, the ANAO examined whether Industry had:

- structured processes in place to identify and manage risks, including the risk of fraud and the risks associated with conflicts of interest;

- established suitable program guidance and support arrangements, including well-designed program guidelines;

- met key financial framework requirements relevant to the administration of the AAIP; and

- developed (and reported against) measures to provide insights into the AAIP’s performance, including performance against its objectives and outcomes, as well as key aspects of the administration of the AAIP.

Risk management

2.4 Risk management is an integral part of effective public administration and plays an important part in securing value with public money.39 Entities should adopt a structured approach to identify, assess, treat and monitor potential threats or risks to the effective administration of government programs or the achievement of policy objectives.

2.5 The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act)—which took effect from 1 July 2014—establishes a new framework for the use and management of public resources by Commonwealth entities and encourages managers to take a risk-based approach. In particular, under section 16 of the Act, the ‘accountable authority’ of a Commonwealth entity40 must ensure that appropriate systems and processes are in place relating to risk and control.

AAIP-related risk management arrangements

2.6 During the current Australian Apprenticeships Support Services (Support Services) contract round41 Industry undertook two risk assessments that are pertinent to the AAIP. These assessments relate to the:

- delivery and management of the Support Services; and

- the operation of the Training and Youth Internet Management System (TYIMS).

2.7 Overall, the ANAO’s analysis indicated that the risk assessments were well-designed While the two assessments were not integrated—having been developed at different times by different areas of the department—the ANAO’s analysis showed that the information in the plans was complementary.

2.8 Together, the two risk assessments covered a broad range of relevant risks. Most of the risks were described in sufficient detail and considered to be appropriate. Nevertheless, there are a few additional risks that the Department of Education and Training (Education and Training)—the administering entity from 23 December 2014—may wish to consider for inclusion in future risk assessments for the AAIP. This includes risks arising from:

- implementing significant changes to the program, including the eligibility criteria, at short notice;

- disruptions to the availability of AACs’ premises or staff; and

- loss of institutional knowledge about the program.

2.9 For the most part, the controls and treatments listed in the risk assessments were suitable and appropriate. However, the accuracy and usefulness of the Support Services risk assessment would be enhanced by addressing the following shortcomings:

- no controls were documented for risk 24 (false information provided in relation to eligibility criteria). That said, the ANAO observed that Industry did have a variety of controls and processes designed to help mitigate the risks around fraudulent claiming of financial assistance; and

- the description of the identified controls did not clearly align with the risk event in a number of cases, including: risk seven (AACs do not have appropriate financial management measures); risk 12 (AACs management and administration of contract is ineffective); and risk 18 (failure to act on agreed terms in the contract).

2.10 In addition, the following controls listed against risks 21 and 22 (relating to fraud) in the Support Services risk assessment were not operating as intended during the current contract round:

- ‘Audit and Investigations Group undertake performance audits of AACs’;

- ‘targeted monitoring resulting from trend analysis’; and

- ‘Audit and Investigations Group undertake data analysis’.

2.11 At the time of the audit, Industry’s entity-wide Fraud Risk Assessment (FRA) also contained information on AAIP-specific fraud risks and controls.42 The ANAO’s analysis indicated that one of the controls listed in the FRA—namely, ‘data mining to examine claiming trends’—was not operating as intended during the current contract round. Industry advised the ANAO that it did not undertake any structured data analysis or data-mining activities. However, it advised that ad-hoc enquiries would be undertaken in response to issues identified, including allegations of potential errors or fraud.

2.12 The ANAO also observed that the Support Services risk assessment did not include details of monitoring strategies for the identified risks or controls. Industry advised that risk assessments were required to be reviewed at least annually and also if there were significant changes to either the program or the Support Services contracts. However, the ANAO observed that formal reviews of the Support Services and TYIMS risk assessments did not occur as often as might be expected during the current contract round. Specifically, both assessments were only reviewed once during the current contract round—the Support Services plan in July 2013; and the TYIMS risk assessment in August 2012.

2.13 Education and Training would benefit from strengthening arrangements for monitoring and reviewing risk assessments associated with the AAIP. Monitoring and review can be particularly valuable in helping: assess the accuracy of the identified risks and the attendant risk controls and treatments; provide insights about new and emerging risks; and confirm the ongoing suitability and continued operational effectiveness of risk treatments and controls. In the case of the AAIP, regular monitoring of risks is important in light of the ongoing changes to aspects of the program’s design and fluctuations in the economy and the labour market, which can affect the take-up of apprenticeships and, in turn, the operation of the AACs.

AACs’ approach to risk management

2.14 Under their contracts with the Australian Government, the AACs are required to have a risk management plan (RMP). Each year, as part of their reporting to the department, the AACs are required to provide a copy of the plan, together with details of any actions taken under the plan.43

2.15 While each of the reports examined by the ANAO contained a copy of the relevant AAC’s RMP, none of the reports examined contained supporting commentary or analysis about the RMP, including a description of recent, current or proposed activity in relation to the RMP. In this context, the ANAO reviewed the RMPs of a selection of AACs and observed significant variation in terms of completeness, quality and focus on Support Services risks. In particular, only four of the reviewed plans had an explicit focus on the Support Services. The other plans reviewed either only outlined the AAC’s risk management policy (without identifying specific risks) or identified risks largely from their own business, rather than a Support Services perspective.

2.16 Education and Training could usefully clarify expectations about the RMPs by providing advice to the AACs on key areas of focus, such as the core service delivery risks. Such advice should encourage AACs to give greater attention to the identification and management of shared program risks. Education and Training advised the ANAO that guidance on the content of RMPs will be included in the Operating Guidelines issued under the terms of the new Australian Apprenticeships Support Network (Support Network) contractual arrangements.44 Further, there would be merit in Education and Training examining ways to gain assurance of the continued effectiveness and operation of the service providers’ RMPs.

Managing conflicts of interest

2.17 The effective management of conflicts of interest45 is an important aspect of the administration of Australian Government services. The potential for conflicts of interest is a noteworthy risk in the administration of the AAIP. For instance, departmental records showed that the majority of organisations contracted to deliver Support Services are also involved in the delivery of other services relevant to Australian Apprenticeships. Specifically, 16 of the organisations are also either a Registered Training Organisation or a Group Training Organisation or, in some cases, both. A number are also involved in the provision of other employment services, such as recruitment.

2.18 Industry had a number of processes in place to manage conflicts of interest risks associated with the delivery of the AAIP. These arrangements included processes for promoting awareness about, and obtaining up to date information on, conflicts of interest. Specifically, Industry’s ‘Code of Conduct in Contracting’ set out the expectations of staff involved with the department’s business partners, and provided practical guidance on potential conflict situations.

2.19 The AACs’ contracts with the Australian Government contained a number of provisions relating to the management of potential conflicts of interest. Among other things, the AACs are required to:

- report details of any conflicts that arise, including the steps taken to resolve the conflict46; and

- maintain a Conflict of Interest Management Plan (COIMP)— each year, as part of their contractual reporting obligations, the AACs are required to confirm whether the strategies identified in the COIMP for managing actual or perceived conflicts of interest have been effective.

2.20 The ANAO examined a sample of AACs’ COIMPs and observed that most of the plans indicated that the AACs had structured processes in place for managing conflicts of interest. In particular, many of the plans outlined practical strategies and identified clear accountabilities for dealing with conflict of interest situations.

Program guidance and support

2.21 The ANAO examined the design and content of key program guidance and support material, including: the AAIP Program Guidelines; the Support Services Operating Guidelines; and application and claim forms. In addition, the ANAO examined other arrangements for supporting the AACs, including, Industry’s processes for keeping them informed about relevant policy changes.

Program Guidelines

2.22 The design of the Program Guidelines established for a grant program can play a central role in effective and accountable grants administration. Specifically, under the Australian Government’s grants policy framework, officials must develop, and make publicly available, guidelines for all new grant programs.47

2.23 The appropriate design and the content of grant guidelines will vary depending on the size, scope and nature of the grant program. However, an underlying principle is that grant guidelines support effective grants administration by addressing those matters necessary to promote transparent and equitable access to the grant program. A number of common information elements should nonetheless be addressed in grant guidelines, including information on the:

- program’s purpose, scope and objectives;

- roles and responsibilities of those involved in administering the program;

- methods of applying for funding under the program; and

- processing of applications or claims, including assessments against the program’s eligibility criteria.48

2.24 The ANAO assessed the extent to which the design of the AAIP Program Guidelines reflected the better practice guidance on information elements contained in the ANAO’s grants administration Better Practice Guide and in the 2013 Commonwealth Grant Guidelines (CGGs). Overall, as shown in Table 2.1, the Program Guidelines largely addressed these elements.

Table 2.1: ANAO assessment of the content of the AAIP Program Guidelines

|

Key elements |

Included in the Program Guidelines |

|

Program purpose, scope, objectives and desired outcomes |

Yes |

|

Mandate for program and nature of operation |

YesA |

|

Total available funding and any limits on amounts individual applicants can seek |

YesB |

|

Eligibility criteria |

Yes |

|

Governance arrangements, including roles and responsibilities |

Yes |

|

Application process |

Yes |

|

Selection processes, including procedural and evidential requirements |

Yes |

|

Whether there is any discretion to waive or amend the eligibility criteria |

Yes |

|

Any review or appeal mechanisms |

Yes |

|

Recovery of overpayments |

Yes |

Source: ANAO analysis.

Note A: The nature of the AAIP as a grants program is not disclosed.

Note B: The total limit of program funding was not disclosed in the guidelines. However, the amounts payable for each individual incentive and personal benefit are outlined.

2.25 Overall, the ANAO’s analysis indicated that the AAIP Program Guidelines are designed to give effect to the policy intent of the program. Representatives of each of the six AACs interviewed by the ANAO indicated that the information in the Program Guidelines was useful and informative. However, a common view was that the design of the guidelines could be made more user-friendly. For instance, several of the AACs observed that interpreting technical elements, especially around eligibility, can be confusing.

Operating Guidelines

2.26 The Operating Guidelines outlined the administrative and procedural arrangements between the department and the AACs. Among other things, the Operating Guidelines:

- described the department’s approach to monitoring the performance of the AACs; and

- contained procedural and administrative detail on claim processing, reporting and other contractual requirements, including the rules relating to determining the AACs’ fees.

2.27 Overall, the ANAO’s analysis indicated that the nature and level of the information contained in the Operating Guidelines was useful and well-targeted. In particular, the design of the Operating Guidelines can be expected to: help support consistency in the delivery and management of the Support Services; and encourage effective and efficient claim management and decision-making by the AACs.

Application and claim forms

2.28 To support consistent and effective claim processes, Industry used a suite of standard application and claim forms for the different types of AAIP payments. Overall, the ANAO’s analysis indicated that the application and claim forms were well-designed. In particular, the forms:

- were sensibly structured and clearly written;

- included guidance and key messages that were consistent with the Program Guidelines;

- reflected the evidence requirements of the Program Guidelines;

- included appropriate and relevant requests for information and supporting evidence; and

- contributed to efficient and effective claims administration. In particular, the forms were designed to be largely auto-populated from information in TYIMS, minimising the need for applicants to enter information previously provided.

2.29 The ANAO observed that the relative brevity of the application and claim forms is consistent with the contractual requirements on the AACs to provide support to employers and apprentices. Given the complexity of AAIP policy, including the myriad of eligibility conditions, the provision of support by the AACs is a more effective approach to supporting claimants than adding more explanatory material to the forms.

Other support mechanisms

2.30 Industry had a number of other processes designed to support the AACs keep abreast of program developments and support their administration of the Support Services.

Advice on policy changes

2.31 Industry’s national office was responsible for ensuring that the AAIP’s policy changes were reflected in relevant reference material. The national office notified the department’s state contract managers (SCMs) when policy changes occurred. The SCMs, in turn, notified the AACs in their sphere of influence about the changes.

2.32 As outlined in chapter 1, a number of policy amendments were made to the AAIP by the Australian Government during the current contract round. The ANAO’s analysis showed that details of each of these policy changes had been accurately incorporated into the Program Guidelines; and notified to SCMs and to the AACs, in a timely manner.

2.33 The ANAO’s examination of Industry’s arrangements for dealing with issues raised by the AACs—such as seeking clarification of AAIP policy—indicated that the department’s approach was functioning appropriately. SCMs and their staff advised the ANAO that they usually respond directly to queries from the AACs, and only sought clarification from national office where they considered the query had national implications. While this approach is reasonable, to help minimise the risk of inconsistent advice being provided to AACs, there would be merit in Education and Training developing a protocol for dealing with AACs’ queries, including outlining the characteristics of queries that should be escalated to the department’s national office.

Training

2.34 As part of the transition from the fourth to the fifth Support Services contract round, Industry provided a structured program of training to all AACs. This training was delivered by SCMs and their staff using material prepared by Industry’s national office. Training on the use of TYIMS was also provided, particularly aimed at new AACs. The ANAO observed that the training materials were clear and covered key aspects of the Support Services arrangements.

2.35 The ANAO’s interviews with SCMs and representatives of the AACs indicated that further training during the current contract period had typically occurred on an informal and ad-hoc basis. For instance, the ANAO was advised that informal training sessions were provided at the time of policy changes and also following six-monthly file monitoring exercises. One AAC also advised the ANAO that the department had assisted in the provision of training to a number of new starters in one of its processing teams.

2.36 To complement the training offered by Industry, the AACs are also required to provide training and staff development activities. The ANAO’s examination of a sample of AACs’ annual Operational reports during the current contract round indicated that most AACs had provided Industry with details of training relevant to the AAIP. Among other things, this included training on: the Program Guidelines; the Operational Guidelines; TYIMS; customer service; and cultural development. An example of good practice observed in one case, was that Industry’s fraud team was scheduled to provide fraud awareness training to a selection of the AAC’s staff.

Key financial framework requirements

2.37 Industry’s administration of the AAIP was subject to the requirements of the Australian Government’s financial framework established by the former Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 (FMA Act) and the associated FMA Regulations.49 Specifically, the ANAO examined whether Industry met the following financial framework requirements:

- approval of spending proposals—former FMA Regulation 9; and

- acting in accordance with the former CGGs.

Approving spending proposals

2.38 The former FMA Regulation 9 prohibited the approval of a spending proposal unless the approver was satisfied, after making reasonable enquiries, that the spending proposal would be a proper use of Commonwealth resources.50 Industry had separate processes for obtaining approval of spending proposals for each of the key components of AAIP expenditure—fee-for-service (FFS) and financial assistance (employer incentives and personal benefits).

2.39 The ANAO’s analysis indicated that the necessary approvals under FMA Regulation 9 were obtained for the FFS expenditure associated with the current round of Support Services contracts—both the initial two-year term from 1 July 2012; and the 12 months extension of the term to 30 June 2015. In relation, to financial assistance expenditure, Industry advised that approval (under FMA Regulation 9) was obtained each time the Program Guidelines were updated. The ANAO’s analysis showed that the necessary approvals were obtained for each new version of the Program Guidelines in the current contract round from February 2013 onwards. However, while each of earlier versions of the guidelines in the current contract round—namely July 2012; August 2012; and October 2012—stated that approval under FMA Regulation 9 had been given, Industry was unable to provide evidence of such approvals.

The Commonwealth Grant Guidelines

2.40 The CGGs51—and from 1 July 2014, the Commonwealth Grants Rules and Guidelines (Grants Rules)52—set out the Australian Government’s requirements relating to the administration of grant programs. In particular, the CGGs and the Grants Rules outline seven key better practice principles to be adopted in granting activities.

2.41 Following the release of the CGGs in July 2009, the then Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR) assessed that the AAIP was not a grants program and, as such, did not fall within the scope of the CGGs. The department’s view was based on the following exemption from the CGGs listed in the then FMA Regulations:

a payment of benefit to a person, including a payment of an entitlement established by legislation or by a government program [emphasis added]. 53

2.42 Amendments to the FMA regulations in May 201354 altered the definition of grants. However, following the re-release of the CGGs in June 2013, Industry did not reassess if the financial assistance provided by the AAIP aligned with the updated definition of a grant in the FMA Regulations.55

2.43 The ANAO assessed that the AAIP met the revised definition of a grants program in the amended FMA Regulations and the 2013 CGGs (and now the Grant Rules). As such, Industry was required, for the period 1 June 2013 to 30 June 2014, to comply with the requirements of the 2013 CGGs, and from 1 July 2014, to comply with the requirements of the Grant Rules.

2.44 Following the ANAO’s enquiries, Industry acted in a timely manner to consider the application of the grants administration framework to the AAIP. Industry advised the ANAO that it established that the AAIP was a grants program according to the revised definition and indicated that:

- details of AAIP’s grants expected to be paid in 2014–15 had been reported on the department’s website;

- a breach of the reporting requirements of the Grants Rules has been recorded in the department’s Certificate of Compliance (CoC) register for the 2014–15 financial year; and

- the department’s CoC return for the 2013–14 financial year would be updated to reflect breaches of the former CGGs.

2.45 Industry’s experience in this case is a reminder that the administration of its programs needs to be consistent with the Australian Government’s financial management framework requirements—and revisions to that framework which occur from time to time—in particular, requirements around grants administration. The ANAO also identified issues relating to Industry’s understanding and application of the grants administration framework in its recent performance audit of the (then) Commercialisation Australia Program.56

Measuring program performance

2.46 Well-designed performance measurement and reporting processes can assist managers by providing:

- a solid basis against which to measure progress and performance;

- an understanding of the drivers of progress and performance; and

- insights into whether the program is being administered effectively and is delivering the outcomes expected by government.

2.47 In particular, regular and ongoing monitoring and review of a program’s performance—using, among other things, well-timed reviews and evaluations, and key performance indicators—assists entities to assess the program’s progress towards its intended outcomes and expected benefits.

Management reporting

2.48 Entities should have processes in place to disseminate relevant information about a program’s performance, including the effectiveness and efficiency of its administration. The ANAO considered whether Industry analysed and reported information to help provide insights into the AAIP’s operations, as well as its performance.

2.49 Industry had well–established internal reporting arrangements in place for assisting managers to maintain oversight of the AAIP. Among other things, the key management reports examined by the ANAO provided:

- quantitative data on Australian Apprenticeships activity levels;

- analysis of AAIP expenditure levels and trends;

- details of the performance of the AACs against their contractual requirements; and

- details on the number and amount of Special Claims.57

2.50 Overall, the ANAO considers that internal departmental reporting on the AAIP was satisfactory with reports generally containing sufficient and appropriate information. Managers had access to useful and relevant information to maintain effective oversight of the program, and to gain timely insights into trends and performance. Table 2.2 summarises the ANAO’s analysis of the usefulness of the suite of internal AAIP reports.

Table 2.2: Assessment of AAIP internal management reports

|

Internal management reports include information and analysis necessary to: |

Results |

|

Gain insight in a timely manner into current issues facing the AAIP |

M |

|

Observe current key trend information for AAIP payments |

M |

|

Retain oversight of AACs’ contract performance |

M |

|

Raise awareness of the impact of external factors with potential to influence achievement of AAIP objectives |

P |

|

Gauge performance against AAIP objectives, including the impact of changes in the AAIP |

P |

Source: ANAO analysis.

Key: M = met; P = partly met.

Key Performance Indicators

2.51 Entities should have a balanced set of key performance indicators (KPIs) in order to provide management, and other interested stakeholders, with a mix of perspectives about a program’s performance. An appropriate set of KPIs will provide information concerning the outputs delivered, the outcomes achieved, as well as information about the effectiveness and efficiency of the way the program is administered.58 In particular, when considered together, the KPIs should present a view as to whether a program is meeting its stated objective.59

2.52 As shown in Table 2.3, Industry had two sets of KPIs relevant to measuring the progress and performance of the AAIP during the current contract round. These were the:

- four measures60 set out in relevant Portfolio Budget Statements (PBS); and

- five indicators used to assess the performance of the contracted service providers in delivering the Support Services.

Table 2.3: Relevant AAIP performance measures

|

Measures |

|

|

PBS measures A |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Source: Industry’s Portfolio Budget Statements 2012–13 and 2013–14, and the Australian Apprenticeships Support Services Operating Guidelines.

Note A: In 2012–13 and 2013–14, these measures were described as ‘deliverables’. In 2014–15, the measures are described as ‘contributing component performance measures linked to an overarching performance measure’, namely: ‘Increased participation in apprenticeships and increased skills in the workforce’.

Note B: The design and operation of the five KPIs relating to measuring the performance of the AACs is examined in chapter 3.

2.53 The ANAO assessed the design of the AAIP’s performance measures against the elements of better practice outlined in ANAO Report No.28

2012–13 Pilot Project to Audit Key Performance Indicators.61 The results of the ANAO’s analysis are shown in Table 2.4.

Table 2.4: ANAO assessment of AAIP performance measures

|

Criteria |

ANAO comment |

|

The performance measures are relevant as they assist users’ decision making. In particular, the KPIs are:

|

Partly met:

|

|

The performance measures are reliable as they allow for reasonably consistent assessments of the program. In particular, the KPIs are:

|

Largely met:

|

|

The performance measures are complete, allowing for an overall assessment of the program. In particular the set of measures is:

|

Partly met:

|

|

Specified performance measures include targets, or desired levels of achievement, and expected timeframes. |

Met. |

|

Targets have a sound and documented rationale and are reasonable. |

Met. |

Source: ANAO analysis.

2.54 As shown in Table 2.4, the ANAO’s analysis indicated that the AAIP’s KPIs only partly meet the better practice criteria. In large part, the AAIP’s KPIs are designed to measure the program’s ‘outputs’, and not the extent of achievement against the program’s outcomes. In this context, a number of the AAIP’s KPIs are akin to intermediate performance measures—for instance: the numbers of employers and apprentices assisted; and the level of satisfaction with AACs’ services. Intermediate performance objectives or targets are important in cases where overall outcomes can only be achieved over the longer-term. In particular, intermediate performance measures can help demonstrate progress towards, and promote better understanding of the factors contributing to the achievement of longer-term outcomes.62

2.55 Importantly, two of the AAIP’s measures—the measures relating to apprenticeship participation rates (KPIs 2 and 3)—are useful proxy measures.63 Such measures are valuable where overall program objectives are difficult to measure because, for instance, the objectives have been set at a high level or their achievement is dependent on a number of external factors.64 In particular, these two measures provide insights into apprenticeship trends and, more broadly, the AAIP’s contribution to ‘developing a highly skilled workforce’.

2.56 Overall, while the suite of performance measures developed by Industry offers some useful insights, it is not possible to determine from these measures alone the extent that the program is achieving its overall objective. The relatively limited insights about the AAIP’s overall performance that can be obtained from the KPIs, underlines the importance of well-designed evaluation activity to support broader assessments of the program’s overall performance.

Performance against the targets in the PBS

2.57 For each of the two completed years of the current Support Services contract round, the actual level of performance for the three KPIs contained in the PBS has been reported in Industry’s annual reports. As shown in Table 2.5, Industry’s annual reports for 2012–13 and 2013–14 show that while the actual number of employers assisted in 2012–13 was significantly below target, the combined totals for employers and apprentices assisted through the AAIP in these years exceeded the combined targets. In particular, the number of apprentices assisted in both years is significantly higher than expected.

Table 2.5: Annual reporting of AAIP performance

|

|

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

||

|

Measure |

Estimate |

Actual |

Estimate |

Actual |

|

Total number of employers assisted nationally through the AAIP |

106 540 |

89 169 A |

80 000 |

77 435 |

|

Total number of Australian Apprentices receiving a personal benefit through the AAIP |

168 100 |

194 268 |

190 000 |

200 454 |

|

Total number of employers and apprentices assisted through the AAIP |

274 640 |

283 437 |

270 000 |

277 889 |

Source: ANAO analysis.

Note A: The department’s 2012–13 annual report stated that the number of employers assisted in 2012–13 fell below expectations following changes to the program that removed eligibility for some payments.

Evaluations

2.58 Program evaluations are an important part of maintaining an outcomes orientation—one of the key grants administration principles set out in the Grants Rules.65 Evaluations involve consideration of the appropriateness, effectiveness, efficiency and achievements of an initiative. By incorporating both qualitative and quantitative analysis, well-designed evaluation activity can facilitate a thorough analysis of program design and performance issues. Evaluations can also provide insights into the success of the program against its objective, and inform its future direction.

2.59 Industry did not have an evaluation plan for the AAIP, and had not, at the time of the audit, conducted a formal evaluation of the AAIP during the current contract round. Industry advised the ANAO that it monitored relevant external research activity, such as the work of the National Centre for Vocational Education Research (NCVER), to assist it to gauge the effectiveness of the AAIP.66

2.60 In 2011, the then DEEWR engaged an external reviewer to assess the efficiency and effectiveness of the range of financial assistance available under the program.67 The review report offered Industry useful insights to help it to better target the types of financial assistance provided by the AAIP. In particular, the ANAO’s analysis indicated that Industry drew on the findings of the review report in recommending many of the policy amendments adopted by government during the current contract round.

2.61 Given the economic and financial materiality of the program, Education and Training would benefit from implementing a targeted program of evaluation activities for the AAIP. A structured evaluation program would ideally include a longer–term focus—this is particularly important in the context of the new service delivery contract round starting on 1 July 2015. An overarching evaluation plan would facilitate consideration of the appropriate timing and focus of evaluation activities.

Recommendation No.1

2.62 To assist the Department of Education and Training better assess the efficiency and effectiveness of the Australian Apprenticeships Incentives Program, including performance against the program’s policy objective, the ANAO recommends that the department implement a program of structured evaluation activity.

Education and Training’s response:

2.63 Agreed.

The ANAO’s previous recommendation