Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Addressing Illegal Phoenix Activity

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Phoenix Taskforce to combat illegal phoenix activities.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Illegal phoenix activity occurs when a new company is created to continue the business of a company that has been deliberately liquidated to avoid paying its debts, including taxes, creditors and employee entitlements.1 Illegal phoenix activity impacts employees, creditors, competing businesses and the Government, with direct costs estimated at between $2.85 billion and $5.13 billion for 2015–16.2

2. Australian Government activities to address illegal phoenix activity date back to the 1970s and 1980s in relation to Bottom of the Harbour schemes. The first major intergovernmental arrangement occurred in 2011 with the establishment by the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) of an Inter-Agency Phoenix Forum to address illegal phoenix behaviour. This was not a prescribed taskforce for the purposes of the Taxation Administration Regulations and the ATO consequently faced considerable limitations in sharing information with other forum members about potential phoenix cases.

3. In response to the information sharing limitations for tax officers, the Phoenix Taskforce (Taskforce) was established on 17 November 2014 through an amendment to the Taxation Administration Regulations.3 The Taskforce’s purposes are to: bring together key Government entities to allow the effective exchange of information and a collaborated approach to mitigate and deter fraudulent phoenix behaviour; and develop a course of action and preferred alternatives. The Taskforce also has five goals and deliverables.4

4. In December 2018, the Taskforce comprised 13 Commonwealth entities and 21 state and territory government entities working together through information sharing and data matching to identify, manage, monitor and take enforcement action against suspected illegal phoenix operators. The Taskforce Steering Committee has five members; the ATO, Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), Fair Work Ombudsman, Department of Jobs and Small Business, and Australian Border Force. The ATO provides the Chair and secretariat services for the Taskforce and the Steering Committee.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

5. The Australian National Audit Office selected illegal phoenix activity for audit because the activity imposes considerable costs on the Australian community (estimated up to $5.1 billion for 2015–16), is a long-standing problem and requires extensive cooperation between government entities, which is often challenging to implement. The audit was intended to provide assurance on whether the Phoenix Taskforce is effectively addressing illegal phoenix activity at a whole-of-government level.

Audit objective and criteria

6. The audit assessed the effectiveness of the Phoenix Taskforce to combat illegal phoenix activities.

7. The audit criteria are:

- Does the Phoenix Taskforce have effective governance arrangements?

- Has the Phoenix Taskforce developed and implemented effective strategies and processes to combat illegal phoenix activities?

- Do the Phoenix Taskforce performance measurement arrangements enable it to assess effectiveness?

Conclusion

8. The Phoenix Taskforce is making progress against its purposes and goals in combating illegal phoenix activity, including through implementing cross-entity strategies, increasing the exchange of information between Government entities on potential cases, collaborating in the conduct of compliance cases and progressing reforms to strengthen compliance powers. Most member entities advised the ANAO that taskforce participation has provided them with benefits in addressing phoenix risks. Importantly, the ATO has significantly increased the amount of tax revenue collected from illegal phoenix operators through audits it has conducted. However, Taskforce joint compliance and enforcement operations are at relatively early stages and have not yet demonstrated major results.

9. Governance arrangements are generally fit for purpose, and support the development of strategies and conduct of operational activities to address illegal phoenix activity as a multi-entity taskforce. These arrangements include the Charter, and the structure and responsibilities of the Steering Committee and working groups. Arrangements are in place for the ATO to share its information with other Taskforce members. The Phoenix Taskforce has an ongoing strategy to develop proposals for law reforms that would help overcome barriers to it addressing illegal phoenix activity, including in sharing information.

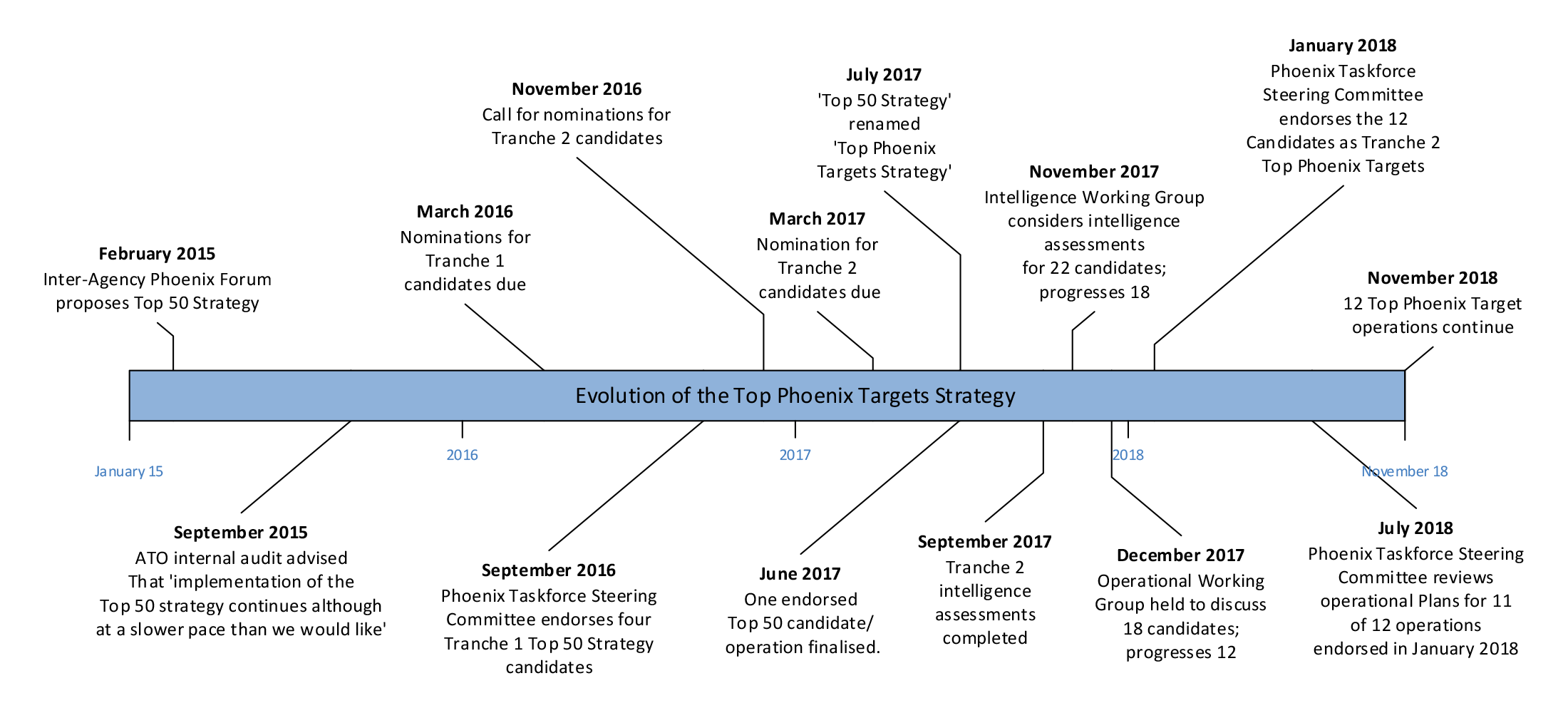

10. The Phoenix Taskforce has developed and is implementing a suite of strategies and processes to combat illegal phoenix activity. This includes commencing 16 Top Phoenix Target operations where agencies from across government work together to address some of the most egregious cases of illegal phoenix activity. Although some successes have been reported, most strategies have only recently been created and it cannot yet be determined if the Taskforce has had a substantial effect in combatting illegal phoenix activity given the size of the problem.

11. Performance measures are in place and an evaluation has been conducted of the Phoenix Taskforce, but misalignment of the Evaluation Framework to the stated purposes and goals of the Phoenix Taskforce has undermined the assessment of effectiveness. There is detailed internal quarterly reporting on progress to the Phoenix Taskforce Steering Committee and half-yearly reporting to the Minister. Taskforce outcomes are published on the ATO’s website.

Supporting findings

Phoenix Taskforce governance

12. The Phoenix Taskforce has developed, implemented and updated a Taskforce Charter to reflect the evolving focus of the Taskforce in collaborating on illegal phoenix matters. The Charter is supported by members exchanging letters to agree to participate in the Taskforce and accepting the Statement of Principles for Information Exchange. Member participation involves the ATO undertaking most activities on behalf of the Taskforce, with Steering Committee members providing support and guidance for operational and some strategic matters, and other members participating on an opt-in basis. Arrangements for working groups, including terms of reference and membership, have not been clearly articulated.

13. Partially effective information sharing arrangements have been established to support the Taskforce’s intelligence and operational matters. Establishing the Phoenix Taskforce under taxation legislation has enabled the ATO to share information on potential high-risk phoenix operators with other Taskforce entities. The extent of this information sharing by the ATO has increased dramatically, from two instances in 2014–15 to 687 instances across 28 entities in 2017–18, when a single disclosure encompassed as many as 4412 companies and trusts related to 110 persons of interest. The ANAO’s analysis identified instances of inconsistency with the ATO’s disclosure process requirements. The ATO also shares non-protected information at Taskforce meetings and through its website on aspects of the Phoenix Taskforce strategies, activities and successes.

14. Most Taskforce entities’ legislation prevents them from sharing information with all Taskforce member entities or the ATO from ‘on-disclosing’ the shared information to other members. These provisions limit the intelligence and operational activities of the Taskforce. Records of information shared with the ATO by Taskforce agencies and any on-disclosure limitations are not centrally maintained.

15. The ATO has developed and issued guidance to member entities to support the coordination of Phoenix Taskforce operations. However, there is limited guidance on developing intelligence for the Taskforce (beyond information sharing) or to support decision-making at intelligence and operational working groups when selecting cases to pursue.

16. Barriers to addressing illegal phoenix activity have been identified over a number of years, including by the ATO, other Taskforce members and research entities such as the Productivity Commission. Building on previous legislative reforms, in 2017 the Phoenix Taskforce Steering Committee developed a law reform proposal that was progressed by Treasury. Seven reforms were accepted by Government, with two implemented and five introduced to Parliament as legislation for consideration. The Taskforce has an ongoing program of work to propose law reforms to help overcome barriers to it addressing illegal phoenix activity.

Strategies and processes to combat illegal phoenix activity

17. The Phoenix Taskforce, through the work of the ATO, has developed a suite of strategies and processes to address illegal phoenix activities across the regulatory spectrum of educate, engage and enforce. While there have been some successes, most strategies have not been in place long enough to produce significant impacts. The Australian Securities and Investments Commission developed its own strategy, which focused on addressing illegal phoenix activity in its role as a corporate regulator. No other Phoenix Taskforce members reported having specific strategies or processes to address illegal phoenix activity.

18. The Phoenix Taskforce has mostly effective risk-based processes for the selection of matters that are referred for compliance and enforcement activities. The ATO’s risk-based processes are used to identify matters to be referred to the Phoenix Taskforce’s Intelligence and Operational Working Groups. However, the Working Groups do not have further risk and materiality concepts to apply when selecting suitable individuals to become Top Phoenix Targets. Where phoenix matters involve potential breaches of criminal law, the Phoenix Taskforce, through the ATO, has established processes for referring the matter for treatment.

19. The ATO, as the lead entity of the Phoenix Taskforce, and ASIC both manage programs of business as usual compliance activities. Under these programs, in 2017–18: the ATO completed 340 reviews and audits of phoenix operators and collected $190 million in cash (which was a large increase on $17 million collected in 2014–15); and ASIC completed 53 investigations and banned 45 company directors relating to illegal phoenix activity. Since adopting an operational focus in August 2016, the Phoenix Taskforce has commenced 16 cross-entity operations under its Top Phoenix Targets Strategy, which target some of the most egregious illegal phoenix operators. These operations have had initial successes, such as in raising liabilities and issuing garnishees, but have not run their course in progressing through civil or criminal enforcement and prosecution activities.

Performance measurement arrangements

20. The endorsed Phoenix Taskforce Evaluation Framework is not adequate as it does not clearly assess achievement of the Taskforce’s purposes and goals, instead focusing on effectiveness of high-level treatment strategies (output groups). An evaluation was conducted in February 2018 that identified mixed effectiveness in achieving Taskforce strategies. The evaluation noted shortcomings in effectiveness measures and supporting data, which are being addressed.

21. The Phoenix Taskforce monitors and reports on Taskforce activities in a detailed quarterly report to the Steering Committee, which was introduced in 2017–18. A separate quarterly report to the Minister was introduced at the same time. The reports have an action and activity focus and do not include performance indicators from the Evaluation Framework. While the reports include some statistics, they rarely report these statistics against baselines, targets and benchmarks. The reports reflect all phoenix activities of the ATO, some activities of the Steering Committee and other members involved in operations. The majority of Taskforce members do not contribute to Taskforce reporting, and there is no consolidated reporting of the extent of Taskforce members’ efforts and their successes overall in combatting illegal phoenix activity.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 2.37

The Phoenix Taskforce provides guidance to clarify the basis on which intelligence and operational working groups refer, and recommend pursuing, potential illegal phoenix cases.

Phoenix Taskforce Steering Committee entity response: Agree.

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 3.40

The Phoenix Taskforce captures lessons learnt from its operations, and refines future operations accordingly to support their effective conduct.

Phoenix Taskforce Steering Committee entity response: Agree.

Recommendation no.3

Paragraph 4.9

The Phoenix Taskforce:

- aligns the purposes, goals and outcomes in its Charter and Evaluation Framework;

- ensures the purposes and goals clearly state the outcomes the Taskforce seeks to achieve; and

- includes baselines or targets for performance indicators in the Evaluation Framework.

Phoenix Taskforce Steering Committee entity response: Agree.

Summary of entity responses

22. The proposed report was provided to the five Phoenix Taskforce Steering Committee entities listed at paragraph 4 and an extract of the proposed report was provided to the Department of the Treasury. The ATO provided a response on behalf of the Phoenix Taskforce, the summary response is set out below. The Department of the Treasury also provided a summary response which is set out below. All Steering Committee entities confirmed with the ANAO that they supported the ATO’s response. The full responses from entities that provided a formal response are reproduced at Appendix 1.

Australian Taxation Office (on behalf of the Phoenix Taskforce)

The ATO welcomes the audit findings and considers the report supportive of the Phoenix Taskforce’s overall approach to combating illegal phoenix activity which has a significant impact on the Australian community and government.

The audit recognises the progress that the Phoenix Taskforce and the ATO are making by engaging in a whole-of-government approach to combat illegal phoenix activity. This includes implementing cross-agency strategies, increasing the exchange of information between government entities, collaborating in the conduct of compliance cases and progressing potential law reform. As noted in the audit report, the ATO has also significantly increased the amount of tax revenue collected from illegal phoenix operators through its audits.

The ANAO audit found the Phoenix Taskforce is making progress against its purposes and goals in combating illegal activity, while acknowledging that the Taskforce’s joint compliance approaches to addressing illegal phoenix activity have not been in place long enough to fully determine their impact. The audit identified opportunities to improve Taskforce guidance, information sharing, intelligence, candidate development, debriefs, performance measurement and evaluation processes.

The ATO agrees with the three recommendations contained in the report. We are already implementing a number of measures to address these recommendations and suggestions.

The ATO notes the ANAO’s comments regarding inconsistencies in the management of information disclosures to Taskforce members and is taking steps to automate and improve the processes. The ATO welcomes the ANAO’s comments regarding improvements to our processes, but we consider that no legislative breaches have occurred.

Department of the Treasury

The Treasury welcomes the ANAO’s assessment of the effectiveness of the Phoenix Taskforce to combat illegal phoenix activities, and its examination of law reform efforts in this area.

While the report does not contain any recommendations for Treasury, we will consider the key insights from the report in the context of our policy responsibility for relevant corporations and tax laws and for law reform to combat illegal phoenix activity.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages from this audit that may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Performance and impact measurement

Governance and risk management

1. Background

Nature and impact of illegal phoenix activity

1.1 Illegal phoenix activity occurs when a new company is created to continue the business of a company that has been deliberately liquidated to avoid paying its debts, including taxes, creditors and employee entitlements.5 Sometimes referred to as fraudulent phoenix behaviour, illegal phoenix activity is distinct from standard phoenix activity where corporate structures are replaced for legitimate business purposes.

1.2 Illegal phoenix activity impacts employees, creditors, competing businesses and the Government.6 It has particular impacts on:

- tax revenue — reduced Commonwealth and State taxation revenue, including income tax, goods and services tax and payroll tax;

- employee entitlements — reduced superannuation and other entitlements;

- compliant businesses — phoenix operators receive an unfair advantage by ‘undercutting’ competitors due to their artificially low cost structures;

- contractors/sub-contractors — non-payment for work performed. This can have a flow on effect resulting in business failures and financial distress; and

- Government expenditure — increased spending on monitoring and enforcement.

1.3 Since 1996, there have been three main estimates of the cost of illegal phoenix activity:

- in 1996, the Australian Securities Commission estimated the cost to the Australian economy to be as much as $1.3 billion annually7;

- in 2012, the Fair Work Ombudsman estimated the total impact to be between $1.78 billion and $3.19 billion per annum8; and

- in 2018, PricewaterhouseCoopers estimated the annual direct cost to the Australian community to be between $2.85 billion and $5.13 billion for 2015–16.9

Phoenix Taskforce

The precursor Inter-Agency Phoenix Forum

1.4 Australian Government activities to address illegal phoenix activity date back to the 1970s and 1980s in relation to Bottom of the Harbour schemes10, and includes the Cole Royal Commission into the Building and Construction Industry in 2003.

1.5 To assist in addressing illegal phoenix activity, the Department of the Treasury (Treasury) sought a range of reforms in 2009. Four of the 11 proposed law reforms were introduced between 2010 and 2012 through amendments to legislation.11

1.6 During the period that law reforms were considered and introduced, the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) established an Inter-Agency Phoenix Forum (the Forum) to address illegal phoenix behaviour. Adopting a whole-of-government approach to addressing phoenix risk was consistent with Government expectations and ATO strategic approaches. The Forum was led by the ATO, with the first meeting held in March 2011. The terms of reference for the Forum were developed in 2011, establishing the purpose of the Forum as:

…bringing together key government agencies in order to identify, design and implement cross agency strategies to mitigate and deter fraudulent phoenix activity.

The Inter-Agency Phoenix Forum (the forum) will also assist the ATO in delivering on a Government commitment to address fraudulent phoenix behaviour, with particular emphasis on delivering on specific commitments to government during the 2011-2015 financial years. The forum will achieve this through the timelier sharing of “intelligence” and also by Agencies jointly focussing on the more egregious phoenix operators.12

The ATO’s information disclosure restrictions affecting the Inter-Agency Phoenix Forum

1.7 Section 355-25 of the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Tax Act) states that it is an offence for a taxation officer to disclose protected information to another entity.13 However, under section 355-70 of the Tax Act, protected taxation information can be disclosed to an officer of a Prescribed Taskforce for the purposes of the Taskforce (where a Taskforce can be prescribed in the Taxation Administration Regulations). Section 355-70 of the Tax Act includes that section 355-25 does not apply if:

- the record is made for or the disclosure is to a prescribed taskforce; and

- the record or disclosure is for or in connection with a purpose of the prescribed taskforce, where a major purpose of the taskforce must be protecting the public finances of Australia.14

1.8 Almost immediately the Forum recognised significant limitations on information sharing in relation to potential phoenix cases, including on the ATO’s information sharing powers under section 355 of the Tax Act, as it was not a prescribed taskforce.

1.9 The Forum considered and initially dismissed the idea of seeking to establish a prescribed taskforce under the Tax Act in June 2011. However, the issue of establishing a prescribed taskforce was reconsidered in November 2011, leading to individual Forum member entities canvassing support from their executive for a prescribed taskforce. By April 2012 members of the Forum reported that their entities would support the establishment of a taskforce to address the difficulty of information sharing between government entities. Over the subsequent 24 months, the ATO wrote to Forum entities about the establishment of a Taskforce seeking a formal response to the proposal. By March 2014 a proposal had been made to Government to establish a prescribed taskforce to overcome restrictions on the dissemination of the ATO’s information. The ATO intended that, once approved, the Taskforce arrangement would enable the ATO to act as a clearing house where it would receive information and then disclose the information to other Taskforce entities (where such on-disclosure was not prohibited by the originating entity).

Establishing the Phoenix Taskforce

1.10 The Phoenix Taskforce was established on 17 November 2014 through an amendment to the Taxation Administration Regulations. The Taxation Administration Regulations 201715, regulation 67, includes the Phoenix Taskforce as a prescribed taskforce for the purposes of section 355-70 of the Tax Act.

1.11 The Phoenix Taskforce is a prescribed taskforce to ‘allow for disclosure of protected tax information by taxation officers to officers of the Taskforce for the purposes of the Taskforce’. On-disclosure rules in the Tax Act continue to protect taxation information once it is disclosed. This means that authorised officers from Taskforce member entities (referred to as ‘taskforce officers’) may only on-disclose taxation information that was provided by the ATO for taskforce purposes.

Operation of the Phoenix Taskforce

1.12 In December 2018, the Phoenix Taskforce comprised 34 Commonwealth, state and territory government agencies working together through information sharing and data matching to identify, manage, monitor and take enforcement action against suspected illegal phoenix operators. There are 13 Commonwealth entities and 21 state and territory entities (see Appendix 2).

1.13 Arrangements for the Phoenix Taskforce include all member entities meeting on an annual or biannual basis at Phoenix Taskforce meetings. A Phoenix Taskforce Steering Committee has also been established and meets on a quarterly basis. There are five Steering Committee members; the ATO, Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), Fair Work Ombudsman, Department of Jobs and Small Business, and Australian Border Force (in the Department of Home Affairs).16 The ATO provides both the Chair and secretariat services for the Taskforce and the Steering Committee. The Phoenix Taskforce also works in collaboration with the Serious Financial Crime Taskforce17 to identify and treat serious financial crime.

Phoenix Taskforce purposes, goals and deliverables

1.14 The Taskforce’s purposes are to: bring together key Government agencies to allow the effective exchange of information and a collaborated approach to mitigate and deter illegal phoenix behaviour (thereby protecting the public finances of Australia); and develop a course of action and preferred alternatives.

1.15 The Phoenix Taskforce has five key goals and deliverables with respect to mitigating and deterring illegal phoenix activity, as shown in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: Phoenix Taskforce goals and deliverables

|

|

Goals |

Deliverables |

|

1. Protect the public finances of Australia by identifying, designing and implementing cross agency strategies to mitigate and deter fraudulent phoenix activity.a |

✔ |

✔ |

|

2. Coordinate the enforcement of State and Federal laws against egregious fraudulent phoenix activity.a |

✔ |

✔ |

|

3. Enable the effective sharing of information, knowledge and experience across taskforce agencies. |

✔ |

✔ |

|

4. Support the reform of administrative practice, policy and where applicable, recommend legislative changes. |

✔ |

✔ |

|

5. Promote community awareness and education as a means of increasing voluntary compliance and community confidence. |

✔ |

✔ |

Note a: The 2018 Prescribed Phoenix Taskforce Statement of Principles updates the purposes to refer to illegal rather than fraudulent phoenix activity.

Source: Prescribed Phoenix Taskforce Charter, September 2017 and Prescribed Phoenix Taskforce Statement of Principles, May 2018.

Law reform

1.16 In February 2017, the Phoenix Taskforce submitted a law reform proposal to the Minister for Revenue and Financial Services. Subsequently, Treasury released a consultation paper Combatting Illegal Phoenix Activity in September 2017, canvassing a range of options for reforms to laws to address illegal phoenix activity. In the 2018–19 Budget, the Government announced a package of reforms to the corporations and tax laws to combat illegal phoenix activity. Two pieces of legislation addressing phoenix law reforms and director identification numbers were introduced to Parliament on 13 February 2019 for consideration and subsequently referred to the Senate Economics Committee.18 The Senate Economics Committee is due to report on these bills by 26 March 2019.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.17 The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) selected illegal phoenix activity for audit because the activity imposes considerable costs on the Australian Community (estimated as up to $5.1 billion for 2015–16), is a long-standing problem and requires extensive cooperation between government entities, which is often challenging to implement. The audit was intended to provide assurance on whether the Phoenix Taskforce is effectively addressing illegal phoenix activity at a whole-of-government level.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.18 The audit assessed the effectiveness of the Phoenix Taskforce to combat illegal phoenix activities.

1.19 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted three high-level criteria:

- Does the Phoenix Taskforce have effective governance arrangements?

- Has the Phoenix Taskforce developed and implemented effective strategies and processes to combat illegal phoenix activities?

- Do the Phoenix Taskforce performance measurement arrangements enable it to assess effectiveness?

1.20 The audit focused on the ATO’s and other taskforce entities’ (particularly Steering Committee members) contributions to the establishment and operation of Phoenix Taskforce governance arrangements, strategies and processes to combat illegal phoenix activity, and performance measurement arrangements. The audit considered how Taskforce entities collaborate to combat illegal phoenix activities. The audit did not examine the activities of state and territory members of the Phoenix Taskforce, but considered the extent of participation of all member entities in Taskforce activities, and received feedback from nearly all members against the audit objective and criteria. To date the Phoenix Taskforce has mainly coordinated intelligence, with a relatively small number of matters underway. Accordingly, more attention was given to intelligence gathering, strategies for detection, information sharing and performance measurement, with less attention to compliance, enforcement, prosecution and prevention activities.

Audit methodology

1.21 Audit procedures included:

- examining the ATO’s records relating to the Inter-Agency Phoenix Forum, Phoenix Taskforce and ATO phoenix activities, including charters and meeting records, risk assessments, strategies, disclosure documents, intelligence and operational policy and guidance, assessments and plans, evaluations, performance measures and reports to Committees and the responsible Minister;

- interviewing and collecting key documentation from Phoenix Taskforce member entities, particularly Steering Committee members, including details of information sharing arrangements, enforcement actions that could be applied to combat phoenix activities, phoenix strategies and referral processes, phoenix work programs, and details of intelligence and enforcement performance measurement; and

- examining the Treasury’s records in relation to the 2009 and 2017 consultation processes and the phoenix law reform proposals.

Entities included in the audit

1.22 The ATO was included in the audit as the lead entity and secretariat for the Phoenix Taskforce. The audit team interviewed and sought supporting documentation from nearly all taskforce members. The audit included a greater focus on the Phoenix Taskforce Steering Committee members due to their role in setting the strategic direction of the taskforce and oversight of operations. The audit also included the Treasury due to its role in the Phoenix Law Reforms.

1.23 The audit was conducted in accordance with relevant ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of $637,000.

1.24 The team members for this audit were Tracey Martin, Nathaniel Loorham, Sonya Carter, Amanda Reynolds, Elizabeth Wedgwood, Chiara Edwards, Lachlan Fraser and Andrew Morris.

2. Phoenix Taskforce governance

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Phoenix Taskforce has effective governance arrangements in place to address potential illegal phoenix activity.

Conclusion

Governance arrangements are generally fit for purpose, and support the development of strategies and conduct of operational activities to address illegal phoenix activity as a multi-entity taskforce. These arrangements include the Charter, and the structure and responsibilities of the Steering Committee and working groups. Arrangements are in place for the ATO to share its information with other Taskforce members. The Phoenix Taskforce has an ongoing strategy to develop proposals for law reforms that would help overcome barriers to it addressing illegal phoenix activity, including in sharing information.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation aimed at the Phoenix Taskforce clarifying the basis for the intelligence and operational working groups escalating cases. The ANAO also suggests that the Phoenix Taskforce Steering Committee more fully discharge its responsibilities for providing strategic direction and oversight (paragraph 2.9), the Phoenix Taskforce clearly articulate arrangements for its working groups (paragraph 2.16), and the ATO improve controls over its disclosure processes (paragraph 2.28).

Has a charter been established and implemented to support effective coordination and collaboration?

The Phoenix Taskforce has developed, implemented and updated a Taskforce Charter to reflect the evolving focus of the Taskforce in collaborating on illegal phoenix matters. The Charter is supported by members exchanging letters to agree to participate in the Taskforce and accepting the Statement of Principles for Information Exchange. Member participation involves the ATO undertaking most activities on behalf of the Taskforce, with Steering Committee members providing support and guidance for operational and some strategic matters, and other members participating on an opt-in basis. Arrangements for working groups, including terms of reference and membership, have not been clearly articulated.

2.1 The Inter-Agency Phoenix Forum and the Phoenix Taskforce have operated under a Charter (or Terms of Reference) that was first agreed in November 2011 and endorsed, subject to ATO approvals, at a Phoenix Taskforce Steering Committee meeting in September 2017. The Charter has been reviewed on several occasions to reflect changes in the nature of the cross-agency arrangements.19

2.2 The September 2017 Prescribed Phoenix Taskforce Charter includes details of the legal status, context, purpose and goals, information sharing activities, roles and responsibilities, resourcing, termination arrangements and duration of the agreement.20 The Charter does not include performance measures, agreed modes of regular review and evaluation, and approaches to identifying and sharing risks and opportunities. These matters have been largely addressed in supplementary documentation, such as the Evaluation Framework that was agreed by Steering Committee members in 2017, or through agenda items at Taskforce meetings, such as sharing phoenix risks and opportunities.

2.3 Of 28 Taskforce members interviewed by the ANAO in September and October 2018, only eight reported having reviewed charters, frameworks, risk documentation or policy and guidance for the Taskforce at least once.

Membership

2.4 In February 2015, an Inter-Agency Phoenix Forum (and Taskforce) meeting agreed that Taskforce members would be asked to exchange letters rather than enter a more formal memorandum of understanding. This approach was considered fit for purpose.

2.5 Consistent with requirements established in the Charter, the ATO has maintained a register of members21 and documentation to evidence the inclusion or removal of members. Documentation also includes correspondence from taskforce entities accepting the invitation to participate in the Taskforce and agreeing to the Prescribed Phoenix Taskforce Statement of Principles for Information Exchange between Taskforce Agency members.22

2.6 Appendix 2 provides a list of members, including the dates of letters of offer from the Chair of the Taskforce, entities’ agreement to the Statement of Principles and indication of intent to participate in the Taskforce. Membership increased from 15 member entities in February 2015 to 34 member entities in December 2018.

Roles and responsibilities

2.7 The September 2017 Charter sets out roles and responsibilities for the chair, secretariat, members and Steering Committee. The ATO is responsible for providing the Chair and secretariat for the Taskforce (and its committees and working groups). Members are expected to commit to active participation.

2.8 Roles and responsibilities remained largely unchanged between the initial terms of reference for the Inter-Agency Phoenix Forum and the September 2017 Phoenix Taskforce Charter. A key exception is the introduction of the Steering Committee for the Taskforce in August 2016. When the Steering Committee was introduced its key purpose was to manage the operational issues of the Phoenix Taskforce. In September 2017 this changed to include providing strategic direction for the Taskforce. In January 2019, the ATO advised that the broader Taskforce is largely involved in intelligence-sharing and operational matters. Table 2.1 sets out roles and responsibilities for members and the Steering Committee of the current Charter.

Table 2.1: Roles and responsibilities documented in the Phoenix Taskforce Charter

|

Position |

Roles and responsibilities |

|

Member |

The role of members will include:

|

|

Steering Committee |

The Phoenix Taskforce Steering Committee will provide strategic input and oversight of Taskforce operations. The primary focus of Phoenix Taskforce Steering Committee is to provide strategic input and oversight of Taskforce operations, including, but not limited to, the following:

|

Source: Prescribed Phoenix Taskforce Charter, September 2017.

2.9 The Steering Committee has continued to manage operational matters, provided input to and oversight of the Top Targets Strategy, commented on the ATO’s Phoenix Strategy, through ASIC contributed to the Data Fusion Project, and contributed to the development of the Evaluation Framework and its application. However, the Steering Committee has not had a broader role in formulating strategy, providing oversight of information sharing and referrals, or monitoring effectiveness (beyond contributing to and reviewing Phoenix Taskforce Steering Committee Reports).

Resourcing

2.10 The Phoenix Taskforce is not explicitly Budget funded,23 and each member entity resources its contribution to the Taskforce from business as usual budget allocations.

2.11 The ATO leads the Taskforce, and in 2018 allocated approximately 100 full time equivalent staff to addressing illegal phoenix activity.24 It develops documentation and intelligence, undertakes most activities and leads operations. The ATO considers that all its phoenix work contributes to and cannot be separated from the work and outcomes of the Taskforce. ASIC is the most active other member of the Taskforce, and estimated that in 2018–19 some 29 full time equivalent staff would contribute to phoenix activities, and 3 to specific Taskforce activities.

2.12 The other member entities did not measure their resourcing for phoenix activities but typically advised that total resourcing, including for Taskforce activities such as information sharing, intelligence and operations, would be less than one full-time equivalent staff over a 12 month period.

Governance structure

2.13 Following the establishment of the Phoenix Taskforce in November 2014, the Inter-Agency Phoenix Forum continued to meet and it was agreed that the Phoenix Taskforce would be a standing agenda item at the Forum meetings (a separate meeting was not needed). The Forum ceased on 1 August 2017, and thereafter the meetings were called Phoenix Taskforce meetings.

2.14 The Phoenix Taskforce has established a Steering Committee, four working groups and operation teams. The Taskforce reports through the Steering Committee and the ATO to the Minister. Figure 2.1 provides an overview of the Phoenix Taskforce governance structure focusing on the Taskforce and key committees, working groups, operations and reporting relationships.25

2.15 As discussed previously, the Phoenix Taskforce Steering Committee comprises five entities, was established in 2016 initially to manage operational issues of the Phoenix Taskforce and also became responsible for setting strategic direction when the Forum was ceased in August 2017. From August 2016, working groups were established for law reform, intelligence and operational matters, and a Communications Working Group was established in 2018. Phoenix Taskforce operation teams have been established since 2016.

Figure 2.1: Governance structure for Phoenix Taskforce committees, working groups and operations

Note: ABF is the Australian Border Force (part of the Department of Home Affairs), FWO is the Fair Work Ombudsman, and Jobs is the Department of Jobs and Small Business.

Source: Based on Taskforce Charter September 2017 and interviews with ATO staff and review of relevant documentation.

2.16 Table 2.2 provides an overview of arrangements for each committee and working group. There are inconsistencies in the governance arrangements established between committees and working groups, including in relation to terms of reference, membership arrangements26, planned meeting frequency compared to meetings held, standing agenda items and documentation of meetings. In January 2019, the ATO advised that the Phoenix Taskforce would develop principles to articulate arrangements for working groups, including terms of reference and membership, noting that the Taskforce takes an agile and dynamic response and aims to reduce red tape.

Table 2.2: Arrangements for Phoenix Taskforce committees and working groups, to November 2018

|

|

Phoenix Taskforce/ Inter-Agency Phoenix Forum |

Steering Committee |

Working groups |

Operation teams |

|

Charter, Terms of Reference or program of work |

Yes |

Yes |

No, except Communications Working Group |

Operation Plan and Guidelines |

|

Planned meeting Frequency |

Not specified, annual or bi-annual |

Quarterly |

Not specified |

Monthly, and as required |

|

Number of meetings held |

29 times in total for both |

14 times (either met or deliberated on matters out of session) |

2 (Intelligence Working Group) 3 (Operational Working Group) 2 (Communications Working Group) |

Varies depending on operation, some monthly, some quarterly |

|

Meeting minutes are maintained |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes for some meetings, except Law Reform Working Group |

Varies depending on team lead, usually no record |

|

Standing Agenda items |

No, some regular and frequent agenda items |

No, regular agenda items |

No |

No |

|

Members |

34 entities |

5 entities |

Variable, 3 to 26 entitiesa |

Variable, 3 to 6 entities |

Note a: Membership has been: 5 to 15 entities (Intelligence Working Group); 5 to 26 entities (Operational Working Group); 5 agencies (Law Reform Working Group); and 3 agencies (Communications Working Group).

Source: ANAO analysis of ATO meeting records and interviews with key staff, including secretariats and operation team leads.

2.17 Of 28 Taskforce members interviewed by the ANAO, 26 reported having attended taskforce meetings, with 11 entities reporting making contributions to agenda items at least once. Eighteen of the 28 entities considered there was a culture where members felt comfortable to engage, ask questions and challenge proposals and position in Taskforce meetings. Seventeen entities considered there was sufficient opportunity to participate, contribute, make decisions and/or endorse activities. Thirteen member entities reported having attended at least one working group meeting or operation team meeting.

Have effective information sharing arrangements been established and used by Taskforce members to support intelligence and operational matters?

Partially effective information sharing arrangements have been established to support the Taskforce’s intelligence and operational matters. Establishing the Phoenix Taskforce under taxation legislation has enabled the ATO to share information on potential high-risk phoenix operators with other Taskforce entities. The extent of this information sharing by the ATO has increased dramatically, from two instances in 2014–15 to 687 instances across 28 entities in 2017–18, when a single disclosure encompassed as many as 4412 companies and trusts related to 110 persons of interest. The ANAO’s analysis identified instances of inconsistency with the ATO’s disclosure process requirements. The ATO also shares non-protected information at Taskforce meetings and through its website on aspects of the Phoenix Taskforce strategies, activities and successes.

Most Taskforce entities’ legislation prevents them from sharing information with all Taskforce member entities or the ATO from ‘on-disclosing’ the shared information to other members. These provisions limit the intelligence and operational activities of the Taskforce. Records of information shared with the ATO by Taskforce agencies and any on-disclosure limitations are not centrally maintained.

Legislative provisions for information sharing powers

2.18 Prescribing the Phoenix Taskforce under Taxation Administration Regulation permits ATO officers to share taxation information with Taskforce members for the purposes of the Taskforce. Most member entities (26 or more) have information sharing provisions included in the legislation they administer that enables them to share specified information with the ATO. Only 12 member entities can share with all Taskforce members, as sharing provisions generally restrict sharing to a limited number of other Taskforce member entities. In some cases, while information can be shared with the ATO or some other Taskforce members, there are restrictions on this information being further disclosed.27 In all cases, entities had regard to the Privacy Act 1988 and the Australian Privacy Principles when considering disclosure of information that was of a personal, sensitive and/or protected nature.

Memoranda of understanding

2.19 Information sharing powers under legislation are supplemented in a number of cases by memorandums of understanding (MOUs) between specific member entities to facilitate information sharing activities. In September and October 2018, 18 Taskforce member entities advised the ANAO that they had one or more MoU with one or more Taskforce member entities to support information disclosure. In total, 30 MoUs were in place, of which 25 were examined by the ANAO.

2.20 Of the 25 MoUs provided, four were head agreements with subsidiary agreements between multiple entities28, one was an instrument of authorisation, one was a ministerial authority for information disclosure, one was a letter of agreement and the other 18 MoUs were entity to entity. The stated purpose of each MOU was similar, generally intending to provide for cooperation and mutual assistance through the exchange of information, intelligence and expertise to maximise outcomes through collective compliance, education and/or enforcement activities. Most reiterated each entity’s corporate purpose and the relevant sections of the entity’s legislation that enabled the sharing of information. Guidance on administrative protocols followed. This included procedures for requesting and receiving information, delegations for authorising the exchange, and how this was to be recorded. All MoUs included commencement and termination dates and a requirement for each entity to make the other entity(s) aware of any amendments to their governing legislation.

Information disclosures made by the ATO for the purpose of the Phoenix Taskforce

2.21 The ATO’s disclosures must comply with relevant ATO accountable authority instructions, policy and guidance, and arrangements established for the Taskforce, including the Prescribed Phoenix Taskforce Statement of Principles for Information Exchange between Taskforce Agency members and real-time referral processes established by the Taskforce.

Non-tax information disclosures

2.22 The ATO adopts an approach, in circumstances where there are no privacy or confidentiality issues, of making information publicly available. For example, on the ATO’s website the Phoenix Taskforce section includes a range of information, including its outcomes, a list of members, a description of illegal phoenix activity and details of work of the taskforce. The section also includes case studies, details of where taxpayers can access help and where to report illegal phoenix activity, and the publication of Inter-Agency Phoenix Forum meeting minutes and documents such as The economic impact of illegal phoenix activity.

Protected information disclosures

Number and volume of disclosures

2.23 The number of disclosures from the ATO to other Taskforce members has increased significantly over the life of the Phoenix Taskforce, as shown in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3: Number of protected information disclosures from the ATO to Phoenix Taskforce entities, 2014–15 to 2017–18

|

Request / disclosure |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

Total |

|

Request initiated by the ATO |

0 |

16 |

77 |

705 |

798 |

|

Request from other member entity |

2 |

20 |

15 |

10 |

47 |

|

Entities making requests |

2 |

11 |

26 |

28 |

67 |

|

Total requests made |

2 |

36 |

92 |

715 |

845 |

|

Requests rejected |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

|

Requests on hand at 30 June |

0 |

2 |

0 |

28 |

30 |

|

Total disclosures madea |

2 |

34 |

93 |

687 |

814 |

Note a: Total disclosures made in a financial year is calculated by adding total requests made to total requests on hand at the end of the previous financial year, and then deleting requests rejected and requests on hand at the end of the current financial year.

Source: ANAO summary of protected information disclosures reported in ATO annual reports 2014–15 to 2017–18.

2.24 Over the four years since the introduction of the Taskforce, the ATO’s annual reports have recorded increases in: the number of Taskforce member entities to which the ATO has disclosed information (two rising to 28 entities); the total number of disclosures (two rising to 687 disclosures); and the average number of disclosures per entity (one rising to 25 disclosures). In the first two years of the Taskforce, most disclosures were initiated by entities other than the ATO requesting information and in the third and fourth year the vast majority of disclosures were initiated by the ATO. The main entities receiving the disclosed information were state and territory revenue offices and ASIC.

2.25 The volume of information shared per disclosure also increased dramatically in 2017 and remained high in 2018. Individual disclosures can contain significant information, for example:

- the ATO has disclosed the same document to 27 agencies and has had approval to make oral disclosures for a particular purpose to 32 agencies; and

- individual disclosures have related to the phoenix behaviours of as many as 4412 companies and trusts related to 110 individuals, 70 entities, 22 groups and/or 19 operations.

Compliance with disclosure requirements

2.26 Appendix 3 sets out the process for disclosing protected information. Under the process, each Phoenix Taskforce entity nominates information ‘gatekeepers’ who request and receive protected information for that entity for the purposes of the Taskforce. All requests must identify the purpose of the disclosure, the entity to which it relates and the proposed recipient. Requests for documentary disclosures must also include the documents to be disclosed (where the request is ATO-initiated) or a description of the documents required (where initiated by other members). For oral disclosures, the request must specify the ATO officers who will disclose protected information and the time period for which they are authorised to do so. Usually these disclosure authorisations are provided for meetings, including Steering Committee, working group and operation team meetings.

2.27 The ATO Information Disclosure Team handles all requests for disclosure of protected information, including Phoenix Taskforce requests. The Team confirms that the request for disclosure is to be made to a gatekeeper/authorised officer of the Phoenix Taskforce member entity and is for, or in connection with, a purpose of the Phoenix Taskforce.29 Once satisfied the request is in order, an Information Disclosure Team officer endorses the disclosure of information for phoenix purposes, and then forwards the Phoenix Taskforce disclosure request to a Senior Executive Service officer delegated to make and authorise disclosures under the Taxation Administration Act 1953. The delegate may disagree or either: agree that the disclosure of the relevant documents is covered by subsection 355-70(1) for phoenix purposes; or authorise (and agree to) the nominated officers making oral disclosures for a specified time period.

2.28 The ANAO examined the disclosure request and approval process for 26230 of 814 disclosures made between 2014–15 and 2017–18 to determine if they were consistent with the ATO’s disclosure process requirements. The ANAO identified instances where elements of the disclosure process were inconsistent with requirements relating to approvals, disclosure periods and disclosure records. Inconsistencies mainly involved oral disclosures, and included:

- 64 oral disclosures where documented authorisation was provided after the disclosure period commenced31;

- incomplete records of oral disclosures made. Records of the 42 disclosures made in the sample prior to 1 January 2018 were stored in the Information Disclosure Officers’ personal Outlook email folders and subsequently deleted.32 The ATO advised in February 2019 that records of 83 disclosures in the sample were maintained in a folder on the Information Disclosure Team shared drive where access is restricted. Information on that drive was not provided to the ANAO during audit fieldwork. In summary, for the sample of 125 requests for oral disclosure, no records were provided to the ANAO to demonstrate how many oral disclosures were made, when they were made, by whom, to whom, or what they were about; and

- one written disclosure where documentation relied upon for approval does not clearly demonstrate the disclosure was agreed.33

2.29 In February 2019, the ATO advised that while no breaches of the law occurred, in response to the findings in the audit that it had not established adequate recordkeeping arrangements to maintain records of oral disclosures, it was taking steps to improve these recordkeeping processes.

2.30 The ANAO also sought to reconcile total disclosure numbers by year to the reported requests and disclosures in ATO’s annual reports. The number of requests and disclosures in 2016–17 and 2017–18 could not be reconciled with the numbers reported in ATO’s annual reports. For 2016–17 the number of rejected and on hand disclosure requests could not be reconciled.

ATO Phoenix records of disclosures and information received

2.31 A central record is not maintained of information disclosed to the ATO by Phoenix Taskforce agencies for Taskforce purposes, including details of on-disclosure limitations imposed on information shared with the ATO. Rather, records are kept in various electronic locations in the ATO’s intelligence systems and case management systems, and it is not possible to readily consolidate records of intelligence shared in Phoenix cases.

Have guidelines been developed to support coordinated intelligence and operational matters?

The ATO has developed and issued guidance to member entities to support the coordination of Phoenix Taskforce operations. However, there is limited guidance on developing intelligence for the Taskforce (beyond information sharing) or to support decision-making at intelligence and operational working groups when selecting cases to pursue.

2.32 Phoenix Taskforce member entities have internal intelligence and operational management guidance and processes to detect, and if appropriate take action against, potential illegal phoenix behaviour as part of their business as usual activities. Notably, the ATO has a suite of intelligence management guidance, including intelligence assessment and briefing templates, and an Intelligence Guide. The ATO’s Private Groups and High Wealth Individuals business line has a range of guidance to support intelligence, case selection and case management activities.34 The guidance and templates support decision-making, including decisions to take no further action, escalate intelligence for possible case selection, and decisions to pursue cases and refer as appropriate to other areas within ATO for action.

2.33 The Phoenix Taskforce provides an opportunity for entities to collaborate and undertake joint intelligence and operation management activities. To support these activities the ATO has developed and issued the following Phoenix Taskforce guidance notes and supporting documentation:

- Real Time Referral Process — Guidance Note for Participating Phoenix Taskforce Agencies (April 2018);

- Multi-Agency Operations — Guidance Note for Participating Phoenix Taskforce Agencies (March 2018);

- Multi-Agency Operations — Guidance Note for ATO Operation Leads and Officers (March 2018);

- Making an ATO-initiated request to disclose protected information;

- Phoenix Taskforce Phoenix Hotline — Guideline for referral process (September 2018);

- presentation on the Phoenix Taskforce Top 50 — Response Plan; and

- phoenix taskforce intelligence assessments, operation plans, and operation status report templates.

2.34 These documents provide guidance to member entities on intelligence sharing activities, including procedures for individual joint operation working groups to develop strategies and operational plans and produce quarterly case status reports. They also provide guidance on procedures for ATO staff releasing information to the Taskforce and in general.

2.35 Beyond information sharing guidance and references to intelligence actions in the Real Time Referral Process developed in April 2018, there are no intelligence development guidance notes for the Taskforce. The ATO develops the intelligence assessments for consideration by the Phoenix Taskforce Intelligence and Operational working groups — there is no guidance supporting other entities contributions to these assessments (and as a result, member contributions are not detailed or consistent). The Taskforce Secretariat advised the audit team that the intelligence assessments developed for consideration of phoenix matters by the Intelligence Working Group were not based on ATO or Phoenix Taskforce guidance documentation.

2.36 There is also limited guidance to support decision-making in the intelligence and operational working groups. The Real Time Referral Process advises that matters should be escalated if appropriate. The main guidance that supports decision processes for the Intelligence and Operational working groups is the Phoenix Taskforce Top 50 — Response Plan, which includes points for consideration, including the jurisdiction in which the behaviour is occurring and the action the Taskforce will take and what taskforce members will be involved. There would be benefit in the Taskforce developing some criteria to assist with the assessments and ratings to support decisions to proceed with or reject matters considered at working group meetings.

Recommendation no.1

2.37 The Phoenix Taskforce provides guidance to clarify the basis on which intelligence and operational working groups refer, and recommend pursuing, potential illegal phoenix cases.

Phoenix Taskforce Steering Committee entity response: Agree.

Have barriers to addressing illegal phoenix activity been identified and associated strategies implemented?

Barriers to addressing illegal phoenix activity have been identified over a number of years, including by the ATO, other Taskforce members and research entities such as the Productivity Commission. Building on previous legislative reforms, in 2017 the Phoenix Taskforce Steering Committee developed a law reform proposal that was progressed by Treasury. Seven proposals were accepted by Government, with two implemented and five introduced to Parliament as legislation for consideration. The Taskforce has an ongoing program of work to propose law reforms to help overcome barriers to it addressing illegal phoenix activity.

2.38 Since 2014, a number of studies, reviews and inquiries have identified barriers to addressing illegal phoenix activity and made recommendations to address these barriers. This work has included the:

- Senate Economics References Committee Inquiry into Insolvency in the Building & Construction Industry (2 December 2015);

- Productivity Commission report into Business set up, transfer and closure (5 September 2015);

- Black Economy Taskforce Final Report (31 October 2017); and

- Productivity Commission report on Data Availability and Use (8 May 2017).

2.39 Recommended solutions have included legislative reforms for information sharing, and for greater enforcement powers and penalties relating to security deposits, director penalties, promoter penalties and a phoenixing offence.

2.40 Between November 2015 and May 2017, the ATO briefed Treasury on areas where it considered reform would assist it to address illegal phoenix activity. The Phoenix Inter-Agency Forum (and Taskforce) has considered some recommendations from these reviews, identified that existing legislation does not provide sufficient tools for the Taskforce to address illegal phoenix activity and had a strategy of pursuing law reform since 2016. In August 2016, the Phoenix Taskforce Steering Committee members formed a Law Reform Working Group. Figure 2.2 provides an overview of the reviews and progression of proposals from the Phoenix Taskforce through Treasury leading to exposure drafts proposing amendments to tax, companies and Fair Entitlements Guarantee legislation and the subsequent introduction of legislation to Parliament.

2.41 In February 2017, the Phoenix Taskforce developed an initial law reform proposal through the Law Reform Working Group and presented the proposal to the Minister for Revenue and Financial Services to progress the law reform. Treasury released a consultation paper Combatting Illegal Phoenix Activity in September 2017, canvassing a range of options for reforms to laws to address illegal phoenix activity. The consultation period closed on 27 October 2017. Treasury received 50 submissions from a variety of sources, including ASIC, academics, individuals, professional bodies and firms that offer legal, insolvency and liquidation and accounting services. Many reforms suggested by the Taskforce were included in the 2017 consultation paper released by Treasury, although several priority reforms, such as changing the definition of director under the legislation, were not included.

2.42 The 2017 consultation paper outlined 11 areas of reform, with 14 specific proposals. Five of these broad reforms areas had been proposed in an earlier 2009 consultation (mentioned in Chapter 1).35 Seven of the 14 proposals (see Appendix 4) from the 2017 proposal were accepted by the Government and included in the 2018–19 Budget. The Phoenix Hotline was implemented in July 2018 and restricting the voting rights of related party creditors was implemented in December 2018. The draft legislation for the remaining five proposals was released for public consultation between August and September 2018 and was introduced to Parliament on 13 February 2019 and was subsequently referred to the Senate Economics Committee. The Senate Economics Committee is due to report on these bills by 26 March 2019.

Figure 2.2: Key reviews suggesting legislative reform and law reform initiatives since the Phoenix Taskforce was established

Source: ANAO analysis of reviews, reports and Phoenix Taskforce documentation.

Other Phoenix-related legislative changes underway

2.43 Other concurrent processes have also resulted in legislative changes aimed at assisting the Taskforce to more readily address illegal phoenix activity.

2.44 The review of the Fair Entitlements Guarantee Scheme administered by the Department of Jobs and Small Business consulted on a range of measures to address corporate misuse of the scheme in May to June 2017. Draft legislation released in October 2017 includes four new civil penalty provisions, amendments to existing criminal provisions, and an expansion of parties who can initiate civil recovery proceedings. The legislation is currently before the Parliament.

2.45 The Director Identification Number (which supports better matching of director’s relationships across companies by government agencies) is being progressed as part of the government’s Modernising Business Registers process. An initial consultation process was undertaken in July 2017, with a subsequent consultation process conducted from 13 July 2018 to 17 August 2018.36 Consultation on the Exposure draft of legislation closed on 26 October 2018.37 The legislation was introduced to Parliament on 13 February 2019.

Collaboration and coordination

2.46 At the August 2018 meeting of the Taskforce, the ATO proposed that a compendium of tools and strategies be compiled to provide an understanding of member entities roles and powers to address illegal phoenix activity.38 The ATO has also identified other barriers, including:

- reciprocal information sharing arrangements with Taskforce member entities;

- absence of a whole of Commonwealth intelligence repository to host and analyse data; and

- lack of unique identifiers across Commonwealth for data matching and analysis.

2.47 Taskforce member entities advised that barriers to coordination and collaboration include:

- members not having information sharing powers to support intelligence activities;

- difficulty identifying phoenix behaviour (challenges include detecting the behaviour early, determining intent and notifying other Taskforce members of suspected behaviour); and

- difficulty finding relevance as member entities do not have the same focus or do not function on the same scale as Steering Committee members.

2.48 Entities have taken action to address some of these issues. For example, some entities have sought reciprocal information sharing powers to enable sharing with the ATO, while other members have not sought these powers. The Phoenix Taskforce has identified the absence of reciprocal information as a risk to the Taskforce and its strategies, and at times has sought to raise with members the need to address reciprocal arrangements. Such change is dependent on affected member entities seeking legislative change, including government support, on an entity by entity basis, and will be impacted by broader information sharing considerations particularly concerning privacy. The information sharing barrier and its impact on addressing illegal phoenix activity was also identified in the Final Report of the Black Economy Taskforce.39

2.49 Information sharing barriers are a whole-of-government issue that extends beyond the role of the Phoenix Taskforce. Specifically, in March 2017, Productivity Commission Report No. 82, Data Availability and Use, proposed the introduction of the Data Sharing and Release Act to create consistent rules for data sharing and release, adopting a risk-based approach, and would authorise the sharing of data within the public sector where legislation is currently a barrier to sharing information.40 The Government responded to the proposed Act by indicating it will continue to improve availability and use of data, including streamlining data sharing arrangements, and has committed to taking action in response to a number of recommendations from the report.41

3. Strategies and processes to combat illegal phoenix activity

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Phoenix Taskforce has effective strategies and processes in place to combat illegal phoenix activities.

Conclusion

The Phoenix Taskforce has developed and is implementing a suite of strategies and processes to combat illegal phoenix activity. This includes commencing 16 Top Phoenix Target operations where agencies from across government work together to address some of the most egregious cases of illegal phoenix activity. Although some successes have been reported, most strategies have only recently been created and it cannot yet be determined if the Taskforce has had a substantial effect in combatting illegal phoenix activity given the size of the problem.

Recommendations and areas for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation aimed at the ATO using lessons learnt from Top Phoenix Target operations to improve operations in the future (paragraph 3.40). The ANAO also suggests that the ATO monitor newly created industry-based strategies (paragraph 3.13), better define risk and materiality concepts to be applied in selecting Top Phoenix Target operations (paragraph 3.26) and attach timeframes to key deliverables in Top Phoenix Target operational plans (paragraph 3.36).

Does the Phoenix Taskforce have effective strategies and processes in place to address potentially illegal phoenix activities?

The Phoenix Taskforce, through the work of the ATO, has developed a suite of strategies and processes to address illegal phoenix activities across the regulatory spectrum of educate, engage and enforce. While there have been some successes, most strategies have not been in place long enough to produce significant impacts. The Australian Securities and Investments Commission developed its own strategy, which focused on addressing illegal phoenix activity in its role as a corporate regulator. No other Phoenix Taskforce members reported having specific strategies or processes to address illegal phoenix activity.

3.1 The ATO has included phoenix risk as a business, enterprise and strategic risk. Under its enterprise risk management framework, the ATO addresses risk by developing, reporting on and evaluating strategies to mitigate risk. Strategies identified for addressing the phoenix risk in 2011–12 included improving relationships with key internal and external stakeholders (including other government agencies), which would lead to greater levels of collaboration in strategy design, risk mitigation and intelligence exchanges. A key achievement in that year was the establishment of the Inter-Agency Phoenix Forum, as well as promoting phoenix risk through other internal and external forums such as the ATO — ASIC Liaison Forum. Between 2012 and 2018, the ATO further developed existing phoenix strategies and introduced a range of new strategies to address the phoenix risk. Similarly, in 2013 ASIC considered that phoenix was a sufficiently significant issue to develop an ASIC Phoenix Strategy, with the first step being to establish a Phoenix Working Party (now Phoenix Committee). ASIC introduced its first Phoenix Work Program in 2015–16.

3.2 The ATO has made the major contributions to developing and implementing strategies for the Inter-Agency Phoenix Forum and Phoenix Taskforce, and considers that all its phoenix activity contributes to broader government approaches to dealing with the phoenix risk. ASIC has also developed strategies to address the phoenix risk (as discussed above and in paragraph 3.17). Unlike the ATO, ASIC does not view its business as usual activities as constituting the Phoenix Taskforce’s body of work.42 No other taskforce entities have explicit phoenix strategies.

3.3 The most comprehensive phoenix strategy is the overarching Phoenix Strategy developed by the ATO and endorsed by the Phoenix Taskforce in February 2018. While focusing on the ATO, the strategy recognises the various contributions across the ATO and partner agencies to dealing with Phoenix activities.

3.4 The Phoenix Strategy contains a work program overview, timeline of activities, opportunities for law reform and innovation, and an outcome and evaluation framework. It also contains additional guidance on the ATO’s approach to addressing illegal phoenix activity, such as governance arrangements and plans supporting the strategy.43

3.5 The Phoenix Strategy adopts an ‘outcomes logic approach’44 that focuses on the achievement of five key outcomes (four intermediate and one strategic outcomes). The outcomes were designed in December 2015 as part of an Inter-Agency Phoenix Taskforce Evaluation Framework, and endorsed by the Phoenix Taskforce Steering Committee in September 2017. The outcomes are:

- businesses are aware of and comply with legislative requirements;

- agencies collaboratively identify at risk businesses and connect with them to encourage compliance;

- cyclical phoenix operators have their business model disrupted and are either brought back into the system, removed from the business environment or penalised;

- incentives to participate in phoenix activities are removed and there is greater business and consumer confidence; and

- there is a reduction in the incidence and impact of phoenix (the ultimate outcome).

3.6 Consistent with established regulatory models that emphasise the link between non-compliance risk and regulatory action,45 the outcomes align with the key approaches of educate, engage and enforce.46 Table 3.1 outlines the link between regulatory approach, risk and relevant Phoenix Taskforce plans or activities.

Table 3.1: Relationship between regulatory approach, risk and action

|

Approach of the Phoenix Strategy |

Non-compliance risk posed by population |

Plans or activities |

|

Educatea |

Low, medium and high |

Quantification — measure the level of illegal phoenix activity in Australia (for example, through Melbourne University and PricewaterhouseCoopers research). Awareness — facilitate understanding of illegal phoenix activity, including its precursors, damage to the Australian economy and avenues to report it. Education — inform companies and directors of their financial obligations through social media, the ATO website, videos, events and external presentations. Information sharing — share data with Taskforce members to identify companies displaying phoenix risk factors. |

|

Engageb |

Medium |

Detection — use data and intelligence to identify companies, directors and others (such as facilitators and promoters) displaying phoenix risk factor. Information sharing — refer matters and intelligence between Taskforce members to enable action in accordance with member’s powers. Industry strategies — target industries at risk through pre-emptive engagement. Compliance activities — encourage compliance through increased contact, audits, investigations and scrutiny of the company, director or other person displaying phoenix risk factors. |

|

Enforcec |

High |

Operations — Phoenix Taskforce cross-agency operations that target high-risk phoenix operators. Compliance activities — monitor compliance through ongoing contact, enhanced reporting (such as monthly rather than quarterly Business Activity Statement reporting) and audits or investigations of the company or director. Enforcement (administrative) — including director disqualification, company deregistration and issuance of statutory notices or fines, disciplining of registered liquidators and actions against advisers. Enforcement (civil) — including civil penalties under the Corporations Act 2001. Enforcement (criminal) — including criminal charges and prosecution under the Criminal Code. Law reform — enhance legal powers to combat illegal phoenix activity. |

Note a: The educate strategy operates broadly and extends to medium and high-risk populations, as well as to facilitators, professional bodies and industry associations.

Note b: The engagement strategy operates broadly and is directed at entities involved in illegal phoenix activity, promoters and facilitators, as well as professional bodies and industry associations.

Note c: The enforcement strategy is directed to entities involved in illegal phoenix activity and extends to promoters and facilitators (for example, deregistration of liquidators). Enforcement activities include state-based civil and criminal remedies.

Source: ANAO analysis.

Implementation of educate, engage and enforce approaches

3.7 By addressing illegal phoenix activity through the risk-related approaches of educate, engage and enforce, the ATO has taken a broad regulatory approach to the problem. Under each approach, the ATO has developed a number of sub-strategies and plans. While some of these focus on a specific risk population, others operate broadly and cut across populations.

3.8 Table 3.2 shows the ATO’s strategies and plans, their implementation status and the approach they align to as at November 2018. Most of these are branded as specific to the ATO, while others are branded for the Phoenix Taskforce.

Table 3.2: The ATO’s phoenix strategies and plans (November 2018)

|

Strategy/work plan item |

Date of approval |

Branded as ATO or Taskforce |

Date implemented |

Completion or review date |

Educate, engage, enforce |

|

Phoenix Strategy |

February 2018 |

ATO |

February 2018 |

Ongoing |

All |

|

Phoenix [staff] Capability Strategy |

January 2018 |

Phoenix Taskforce |

Not clear |

November 2018a |

Educate |

|

Phoenix Research Partnerships |

Ongoing |

ATO |

Ongoing |

Ongoing |

Educate |

|

Communications Strategyb |

Undated |

ATO |

July 2018 |

June 2019 |

Educate and engage |

|

Law Reform Strategies |

Ongoing |

Taskforce |

Ongoing |

Ongoing |

Educate and enforce |

|

Phoenix Early Intervention Strategy |

May 2018c |

ATO |

December 2008c |

July 2019 |

Engage |

|

Facilitators and Promoters Strategy |

October 2018 |

ATO |

October 2018 |

June 2019 |

All |

|

Labour Hire Strategy |

September 2018 (draft) |

ATO |

Not yet implemented |

December 2019 |

Engage |

|

Property and Construction Strategy |

October 2018 (draft) |

ATO |

Not yet implemented |

June 2019 |

All |

|

GST Disengaged Property Developers Strategy |

Ongoing |

ATO |

Ongoing |

Ongoing |

Engage and enforce |

|

ATO Business as Usual Compliance Program |

Ongoingd |

ATO |

Ongoing |

Ongoing |

Engage and enforce |

|

Top Phoenix Targets Strategy |

February 2017e |

Taskforce |

November 2017 |

Ongoing |

Enforce and engage |

Note a: From December 2018, staff capability has been undertaken as part of the ATO’s broader Tax Evasion and Crime staff capability development program, which identifies phoenix as a priority topic.