Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Acquisition, Management and Leasing of Artworks by Artbank

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- The Artbank program is a contemporary art collection and rental scheme with nearly 11,000 works spanning media that includes painting, sculpture, video and photography.

Key facts

- The program was established by a Charter of Operations in 1980.

- As a support program for contemporary Australian artists, the collection was valued at over $42 million, as at 1 July 2022.

- As an art leasing program, the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts (the department) leased 4360 artworks in 2021–22 to 390 clients.

What did we find?

- The department’s approach to acquiring, managing and leasing Australian contemporary art under the Artbank program has not been appropriate.

- An overarching strategy to support the direction of the program and measure its success has not been developed to replace the 1991 Charter of Operations.

- Acquisitions for the Artbank program have not been in accordance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules and have not demonstrated a strong alignment with the targets established in the collection plan.

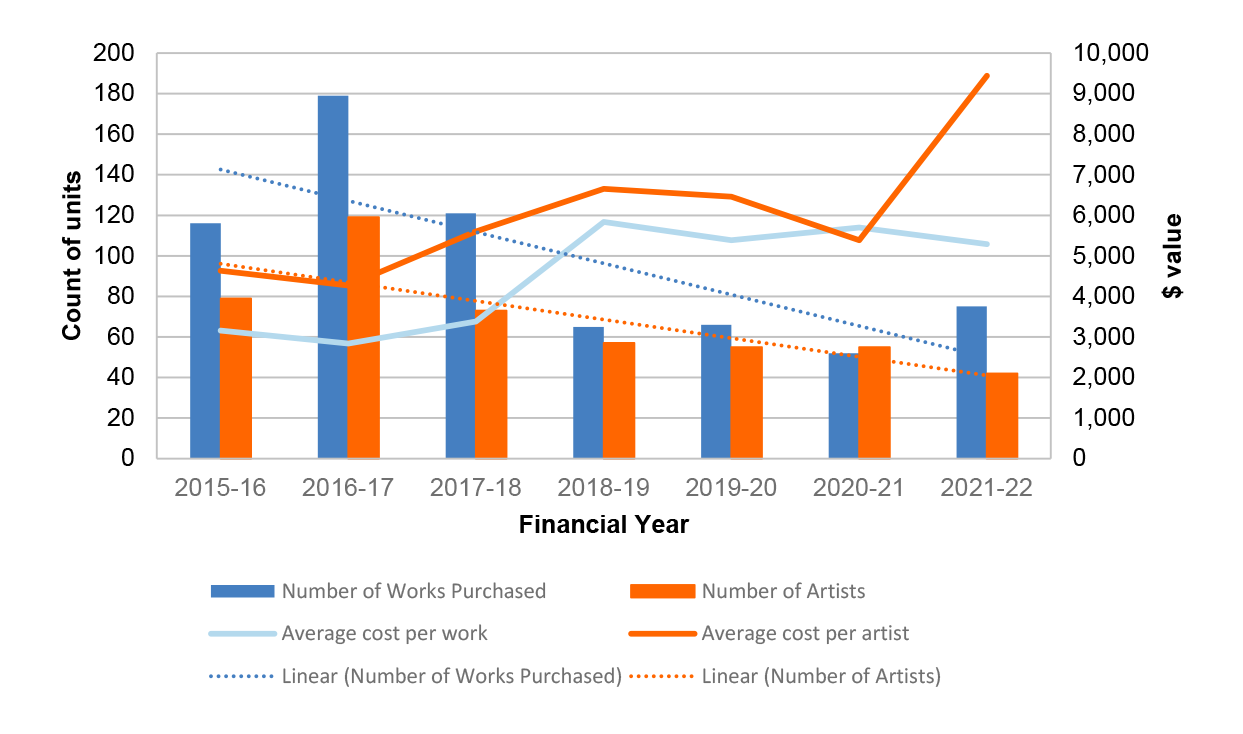

- The department’s management of the Artbank collection has been insufficient to ensure the integrity of the collection.

- The department’s approach to leasing has not been appropriate.

What did we recommend?

- There were eight recommendations to the department focused on governance of the program, procurements, conservation and rental approaches.

- The department agreed to four recommendations, agreed in part to two recommendations, noted one recommendation and did not agree to one recommendation.

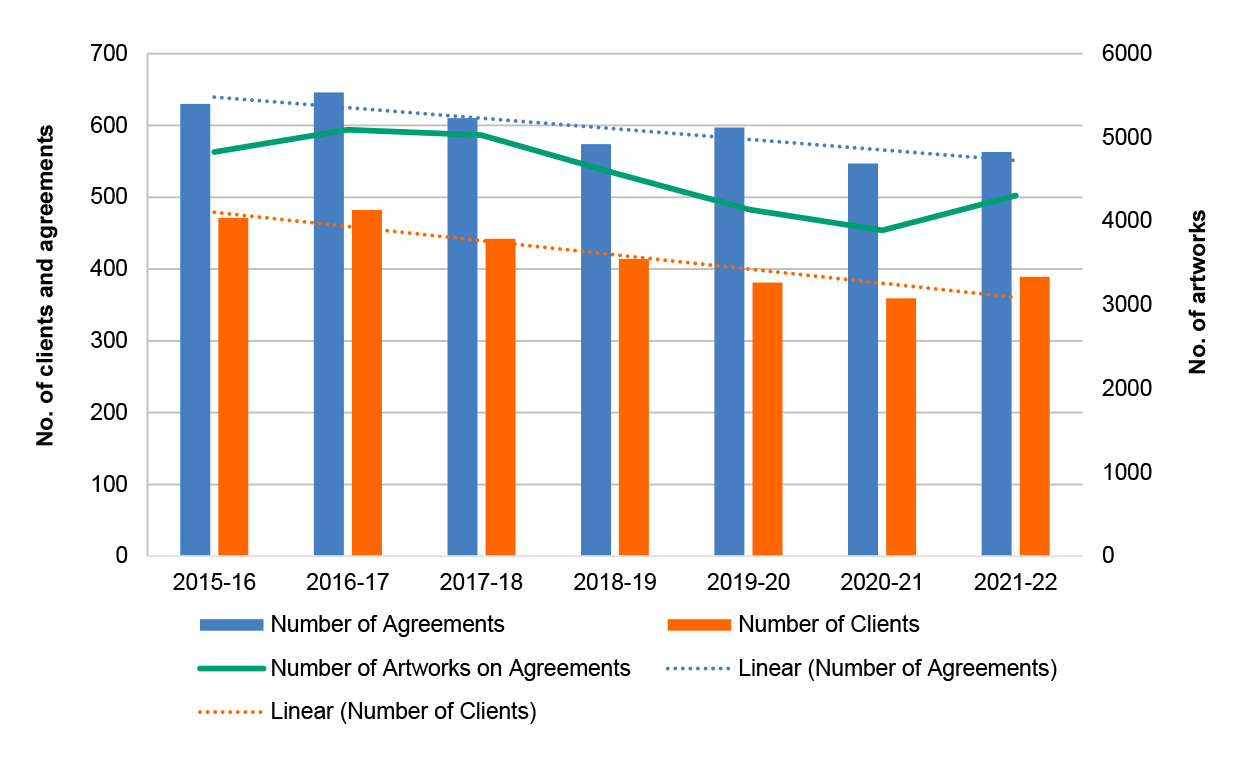

$400,000

annual acquisition budget for the Artbank program since 2019–20.

70%

leasing rate target for the collection.

30%

of the collection was not leased between 1 July 2015 and 30 June 2022.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Artbank program was established in 1980, to support Australia’s contemporary art sector by: providing direct support to Australian contemporary artists through the acquisition of their work; and promoting the value of Australian contemporary art to the broader public.1 The program, designed to be a self-sustaining program by generating revenue through the leasing of the Artbank collection to individuals, companies and governments (at all levels), is administered by the Office for the Arts in the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts (the department).2

2. The Artbank collection was initially endowed 600 artworks from the National Gallery of Australia’s Loan Collection. At the time of this audit, the Artbank collection consisted of 10,950 works valued at over $42 million. In the department’s 2021–22 annual report, the Artbank program had a reported revenue of $2.8 million through the art leasing scheme and expenditure of $566,000 (or 20 per cent of the annual revenue) on 71 new acquisitions.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

3. This performance audit was conducted to provide assurance to Parliament on the administration of the Artbank program, which is a significant contemporary art collection and rental scheme with more than 10,000 works spanning media that includes painting, sculpture, video and photography.

Audit objective and criteria

4. The audit objective was to examine the appropriateness of the department’s approach to acquiring, managing, and leasing Australian contemporary art in the Artbank collection.

5. To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- Is there a clear and cohesive strategic direction?

- Is the approach to acquisition appropriate?

- Is there an appropriate approach to managing the collection?

- Is the approach to leasing artwork appropriate?

Conclusion

6. The Artbank program’s approach to acquiring, managing and leasing Australian contemporary art has not been appropriate.

7. While the 1991 Artbank Charter of Operations established a clear purpose for the program, the department has not developed an overarching strategy to support the direction of the program or measure its success. The department commenced developing operational strategies in 2019 to focus on separate parts of the program’s purpose, being future artwork acquisitions and the rental scheme. These strategies were endorsed respectively in 2019 and 2021 by the Artbank Governance Committee, which was established in November 2019 to oversee the program and monitor the achievement of key activities on a quarterly basis. The committee has only held three meetings, with reporting on the overall financial performance of the program not developed for or provided to the committee. This diminishes the department’s management of the program and its performance.

8. The department’s approach to acquisitions under the Artbank program has not been in accordance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) and has not demonstrated strong alignment with the targets established in the program’s collection plan designed to illustrate the department’s strategy to deliver against the program’s policy intent. Key shortcomings in the acquisition approach were: no open or competitive processes; value for money not being documented or demonstrated; and limited public reporting. Alignment with the program’s purpose and objectives was not evident due to deviations from the department’s Collection Plan for the Artbank program.

9. The department’s management of the Artbank collection is insufficient to ensure the integrity of the collection. Conservation activities are not consolidated, prioritised, committed and reviewed against a planned, wholistic schedule. Records of deaccessioning, the formal removal of artworks from a collection, are unreliable. Approvals were obtained retrospectively for the deaccessioning of over 70 artworks from the collection, with the records for those approvals not identifying that the artworks had already been disposed of via sale over four years earlier. Where deaccessioning has been recorded appropriately, it has not been undertaken in a timely manner with the artworks continuing to add to the costs of the program through storage, management and conservation expenses, rather than being activated (through rental or sale) to continue to support contemporary Australian artists. The integrity of the collection has been placed at risk by the absence of a policy to guide the management of digital or time-based artworks. Fifteen duplicate copies of 14 time-based digital works were created so that those works could be rented 22 times to more than one client at a time.

10. The department’s approach to leasing the Artbank collection has not been appropriate. Rental revenue has been in decline since 2017–18. The department’s documented target is to have at least 70 per cent of the Artbank collection out on rent. The department has recognised that its performance has leased approximately 40 per cent of the collection, which is well below this target. Between 1 July 2015 and 30 June 2022, nearly 60 per cent of the collection was either not leased at all during the period (30 per cent) or had spent more time stored than rented (29 per cent).3 There was no recorded basis for how the pricing methodology for individual artworks was established. Given the extent of undocumented deviations from that methodology, it is not clear how the majority of rental prices (and discounts, where applicable) were ultimately set. Achievement of the full breadth of the program’s purpose has not been a focus, with no reporting to provide assurance that the department’s approach to leasing supports artists or the reputation of contemporary Australian art.

Supporting findings

Strategic direction

11. The last clear and comprehensive endorsement of the Artbank program’s purpose was provided in the 1991 update to its original establishment document, the Charter of Operations. The high-level objectives, as articulated on the Artbank program’s website to ‘provide direct support to Australian contemporary artists through the acquisition of their work; and promote the value of Australian contemporary art to the broader public’, remain reasonably well-aligned with the program’s stated purpose. While the department agreed to ANAO recommendations in 2006 to review the Charter, no review was undertaken and no equivalent overarching strategic plan, aligned with the current legislative framework, to implement the program’s purpose has been developed. Two operational strategies were developed in 2019 (and endorsed in 2019 and 2021) to focus on separate parts of the programs purpose, being the rental scheme and future artwork acquisitions. There is no overarching strategy to address the Artbank program’s purpose. (See paragraphs 2.2 to 2.12)

12. The Artbank Governance Committee was established in November 2019 to oversight the program’s activities; monitor achievement of key activities; and review compliance with government rules and processes. The committee did not meet quarterly in accordance with its terms of reference. As of December 2022, the committee had met three times. This diminished the management of the performance of the Artbank program against its purpose and operational strategies. (See paragraphs 2.15 to 2.24)

Acquisition approach

13. The department’s acquisition approach for the Artbank program has not been undertaken in accordance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs). Shortcomings in the approach include:

- while value for money is the core rule of the CPRs, there is no available evidence demonstrating that value for money has been considered by the department throughout its acquisition process;

- while there is a collection plan to identify acquisition needs, it lacks measurable targets and has not been used to guide acquisition activity;

- the department does not undertake open and transparent procurements, undertake and record comparative assessments of potential acquisitions, including assessing value for money, in its acquisition process for procurements under the Artbank program; and

- since 2015–16, 380 (56 per cent) acquisitions of artworks each valued at less than $10,000 and five (1 per cent) acquisitions of artworks valued at more than $10,000 did not have clear, recorded delegate approval. There was a marked improvement in the recording of delegate approval on all acquisitions after 2019–20. (See paragraphs 3.4 to 3.41)

14. The effectiveness of the Artbank program in supporting artists through its acquisitions has progressively declined over time, from a high of 179 acquisitions in 2016–17 to 75 in 2021–22. Accordingly, the amount of financial support provided to artists through acquisitions for the Artbank collection has also been declining, with the $396,462 spent on acquisitions in 2021–22 being less than the $507,993 spent five years earlier in 2016–17. The program has budgeted $400,000 each year for the acquisition of artworks since 2019. Decisions taken to acquire more than one artwork from an individual artist in a financial year further limits the program’s ability to support a broader range of artists. The cohorts of artists intended to be targeted through the department’s Collection Plan, are often not the artists actually targeted by the program’s acquisition approach. (See paragraphs 3.52 to 3.62)

Managing the collection

15. The department’s preservation activities for the Artbank collection are focused on artworks: being prepared for imminent leasing; returning from lease; or identified as having a high prospect of rentability. While the results of individual condition checks are recorded, this information is not consolidated, or used to develop a preservation or maintenance plan for the Artbank collection, leaving conservation activity ad hoc rather than systematic and strategic. (See paragraphs 4.3 to 4.25)

16. Deaccessioning activities are not timely and rarely initiated. Once initiated there are significant delays throughout the deaccessioning process, particularly between the receipt of approval and disposal of artworks, leading to increased storage and maintenance costs. Processes to establish the timely deaccessioning of artworks after receipt of approvals have not been successfully implemented.

- In 2018, 78 artworks were approved for deaccessioning from the collection by sale while only 10 artworks have been recorded as sold since 2015–16.

- Approvals to deaccession a further 424 artworks prior to 2015 were not implemented for over seven years, with 288 of these artworks placed back into the collection in 2021.

- Since establishment in November 2019, the Artbank Governance Committee has only once discussed and endorsed deaccessioning activities from the collection. (See paragraphs 4.26 to 4.42)

17. The department’s approach to collection management does not appropriately support artists or the reputation of Australian contemporary art. The Artbank program does not actively engage in a deaccessioning approach that increases the public’s awareness of and appreciation for Australian contemporary art. The integrity of the collection has been placed at risk by the absence of a policy to guide the management of digital or time-based artworks. Fifteen duplicate copies of 14 original digital artworks were created to enable those artworks to be leased concurrently to more than one client on 22 occasions. (See paragraphs 4.49 to 4.67).

Leasing approach

18. The approaches to setting rental prices, including the approach to setting individual rental agreement prices, including discounts, have not been appropriately documented and it is not clear how or on what basis the pricing methodology was decided. Implementation of the pricing methodology was incomplete and where there have been deviations from the methodology there is no recorded rationale as to why. While there was a reasonable basis for offering discounts and concessions during the COVID-19 pandemic, the reasons for other discounts and concessions being provided were not documented. The approach to collecting rent has been sound for new agreements, and the department undertakes weekly monitoring of debts to manage the existence and age of bad debtors. (See paragraphs 5.2 to 5.23)

19. Progressively declining rental income since 2017–18 has reduced the department’s ability to fund new acquisitions for the Artbank program. A large contribution to this was that nearly 60 per cent of the Artbank collection (as an income generating asset) spent more time stored than rented. This was recognised by the department in 2020, where an estimated actual leasing rate of 40 per cent was identified by the department as well below the 70 per cent program target, established in the Business Plan. Thirty per cent of the Artbank collection, while available for lease, was not rented at all between July 2015 and June 2022. A further 29 per cent of the collection was leased for less than half of the time the work was available for lease. The Artbank program’s client base — both by number of clients and by number of artworks per client — has also been declining. (See paragraphs 5.24 to 5.30)

20. The department measures the success of the leasing program by the number of artworks leased in a period. Of the four purposes outlined in the program’s Charter of Operations, the focus of the program has been on supporting artists through new acquisitions, with limited attention given to supporting artists and the reputation of Australian contemporary art through the leasing program. The department does not measure the achievement of the full breadth of the program’s purpose, including the location at which works are displayed, and the public accessibility of those locations. (See paragraphs 5.31 to 5.42)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 2.13

The Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts implement an overarching business plan or wholistic program-wide strategy that articulates how the Artbank program will achieve each of its purposes and objectives, including details on how performance will be measured and reported.

Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 2.25

The Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts ensures the Artbank Governance Committee appropriately monitors the Artbank program’s performance against its purpose and objectives, as set out in the committee’s terms of reference.

Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 3

Paragraph 3.42

The Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts:

- increase the transparency of, and accessibility to, Artbank program acquisitions by publishing the Artbank program’s annual procurement activities as part of the department’s annual procurement plan on AusTender, to guide and provide advanced notice to the market about the program’s upcoming procurement activities; and

- ensure that complete, accurate and appropriate data is collected and used effectively to monitor procurements and report against planned collection targets.

Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts response: Agreed in part.

Recommendation no. 4

Paragraph 3.47

The Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts develop a fit for purpose procurement framework for the Artbank program which is consistent with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules, including open and transparent opportunities for Australian contemporary artists (or their representatives) to submit their artwork for acquisition, with clear records made at each step throughout the procurement processes employed.

Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts response: Noted.

Recommendation no. 5

Paragraph 4.17

The Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts:

- develop and implement a conservation work plan with a more strategic and systematic approach to the conservation (or deaccessioning) of artworks; and

- maintain complete and accurate data on condition checking and conservation activities for reporting on the condition and status of all artworks.

Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts response: Not Agreed.

Recommendation no. 6

Paragraph 4.43

The Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts:

- revisit its deaccessioning policy to ensure it is consistent with Artbank program objectives, including the maintenance of an appropriately sized collection that is suitable for leasing; and

- ensure that the Artbank Governance Committee meets at in accordance with its Terms of Reference, such that decisions on deaccessioning may be actioned in a timely manner.

Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts response: Agreed in part.

Recommendation no. 7

Paragraph 5.12

The Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts undertake a review of the rental pricing methodology, with a view to ensuring among other things, that:

- rates are appropriately informed by all relevant strategic, operational, client and market-related factors; and

- appropriate processes and procedures are established to ensure:

- periodic reviews of rates against these factors are conducted with the analysis, results and any changes to rates approved and documented in writing; and

- new rates and pricing details are implemented accurately across all artworks and in a timely manner across all relevant departmental systems.

Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts response: Agreed.

Recommendation no. 8

Paragraph 5.19

The Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts review the approach to providing discounts to clients to ensure:

- approvals are provided by officials with the appropriate financial delegations; and

- the rationale and value for money considerations informing these approvals are recorded before offering and entering into discounted agreements.

Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

The Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications and the Arts (the Department) welcomes the ANAO report and broadly supports its recommendations.

Artbank plays an essential role in both supporting emerging artists, and making Australian artworks accessible to the broader community. The Department is committed to the continuous improvement of the Artbank program, which is unique in its nature, to ensure it continues to achieve its objectives.

The Department recognises that the audit considers activities over a period of years, and notes that there has been a linear progression over time.

The report notes that the Artbank program has not been administered in accordance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs). Artbank is relying on Rule 10.3(d)(i) which permits for works of art to be acquired through limited tender.

The Department took actions during the COVID-19 pandemic, to safeguard the revenue earnings of the Commonwealth. Like most commercial businesses, the pandemic had a profound impact on Artbank’s ability to perform business as usual activities from 2020–22, a significant component of the time covered in this audit.

During the course of the audit, to strengthen the administration of Artbank, the Department identified and implemented a number of improvements and changes to its processes, including: amending documentation of procurement processes; formally changing its practice of dealing with video art; addressing historic non-registration of relevant procurements on the AusTender platform; and improving minuting of meetings where value for money, suitability and rentability of proposed acquisitions are discussed.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

Policy/program implementation

Performance and impact measurement

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The Artbank program was established in 1980, with an initial endowment of 600 artworks from the National Gallery of Australia’s Loan Collection. Artbank is an Australian Government program designed to support Australia’s contemporary art sector by: providing direct support to Australian contemporary artists through the acquisition of their work; and promoting the value of Australian contemporary art to the broader public.4 Administered by the Office for the Arts in the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts (the department)5, the Artbank collection now comprises nearly 11,000 artworks valued at over $42 million as at 1 July 2022.

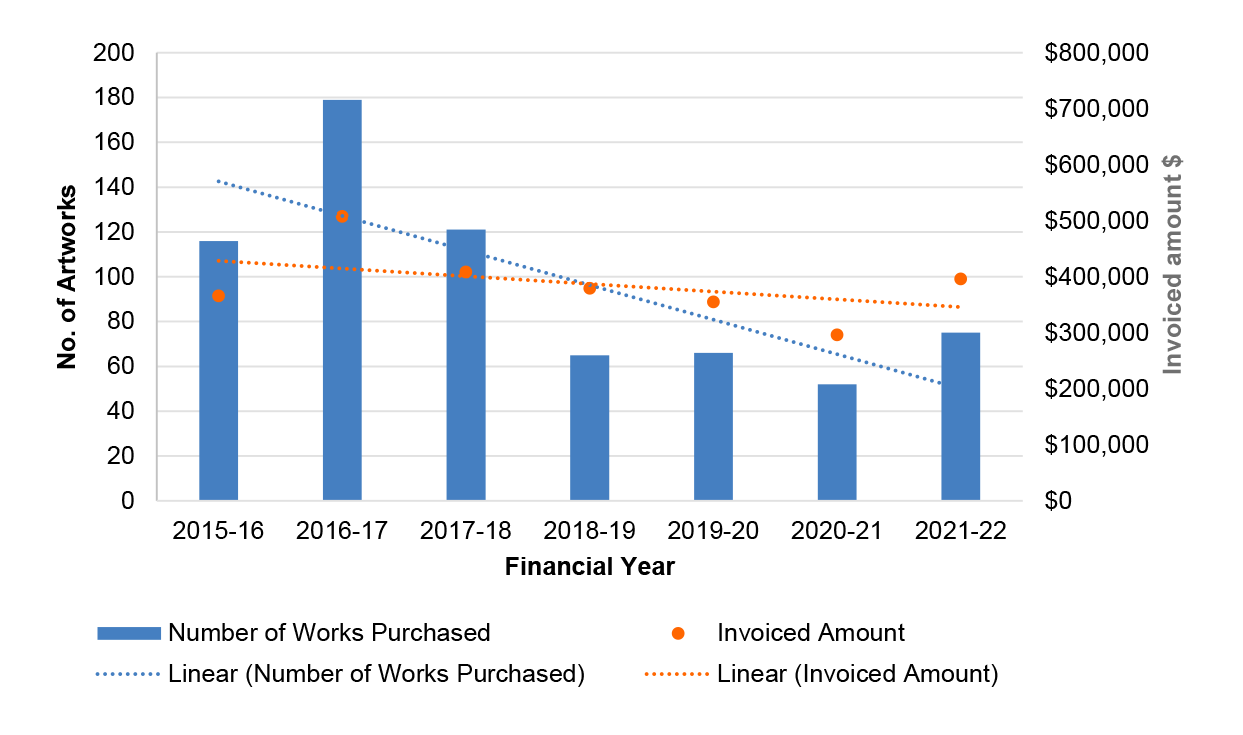

1.2 Public reporting on the revenue generated by the Artbank Rental Scheme and the number and value of artworks in the collection has varied over time (illustrated by Figure 1.1). In the department’s 2021–22 annual report, the Artbank program had a reported revenue of $2.8 million through the art leasing scheme and expenditure of $566,000 (or 20 per cent of the annual revenue) on 71 new acquisitions.6

Figure 1.1: New artwork acquisitions and annual rental income for the Artbank program

Note: Gaps in data indicate that reporting information was not publicly reported in that financial year.

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental records.

1.3 In May 2006, a performance audit conducted by the ANAO7 made seven recommendations regarding the Artbank program’s strategic direction8 and management of the collection. All seven recommendations were agreed to and four of these recommendations were particularly relevant to the scope of this current audit:

- the 1991 Artbank Charter be redrafted to align more closely to the broader legislative and governance frameworks in place at the time of the audit (discussed in paragraphs 2.2–2.4 and 2.17–2.19);

- focused and documented acquisition criteria based on Artbank’s collection needs and policy direction be developed and made publicly available (discussed in paragraphs 3.6–3.8 and 3.25–3.34);

- the transparency and accountability of artwork acquisitions be improved by:

- any submissions received from artists being assessed against the acquisition criteria and those assessments documented (see paragraphs 3.19, 3.23–3.24);

- documenting the reasons that artworks are selected for acquisition against acquisition criteria (see paragraphs 3.28–3.41); and

- report purchases over $10,000 on AusTender (see paragraphs 3.36–3.41); and

- alternative acquisition strategies to engage directly with artists be considered9 (see paragraphs 3.19, 3.21–3.22 and Table 3.1).

1.4 A 2014 departmental functional review made eight recommendations similar to those in the 2006 performance audit report, including the development of a ‘strategic plan with defined KPIs’ and that the department review and ‘immediately clarify governance arrangements’ for the Artbank program.10

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.5 This performance audit was conducted to provide assurance to Parliament on the administration of the Artbank program, which is a significant contemporary art collection and rental scheme with more than 10,000 works spanning media that includes painting, sculpture, video and photography.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.6 The audit objective was to examine the appropriateness of the department’s approach to acquiring, managing, and leasing Australian contemporary art in the Artbank collection.

1.7 To form a conclusion against the objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- Is there a clear and cohesive strategic direction?

- Is the approach to acquisition appropriate?

- Is there an appropriate approach to managing the collection?

- Is the approach to leasing artwork appropriate?

Audit methodology

1.8 The audit methodology included: examination and analysis of entity records; discussions and meetings with relevant departmental staff; and analysis of reports from the information management systems used by the department (including the collections management system).

1.9 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $437,000. The team members for this audit were Hannah Conway, Lachlan Miles, Tamara Duncan, Josh Carruthers, Calli Stewart, Amy Willmott and Brian Boyd.

2. Strategic direction

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether there this a clear and cohesive strategic direction for the Artbank program that is supported by appropriate governance arrangements.

Conclusion

While the 1991 Artbank Charter of Operations established a clear purpose for the program, the Department of infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts (the department) has not developed an overarching strategy to support the direction of the program or measure its success. The department commenced developing operational strategies in 2019 to focus on separate parts of the program’s purpose, being future artwork acquisitions and the rental scheme. These strategies were endorsed respectively in 2019 and 2021 by the Artbank Governance Committee, which was established in November 2019 to oversee the program and monitor the achievement of key activities on a quarterly basis. The committee has only held three meetings, with reporting on the overall financial performance of the program not developed for or provided to the committee. This diminishes the department’s management of the program and its performance.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at improving the performance reporting and governance oversight arrangements for the Artbank program.

2.1 Public sector governance involves the set of responsibilities and practices, policies and procedures, exercised by an entity’s accountable authority, to provide strategic direction, ensure objectives are achieved, manage risks and use resources responsibly and with accountability.11 This should be done within the framework of Commonwealth finance law which, since 2014, has comprised the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) and Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule).

Is there a clearly articulated purpose and strategy for Artbank?

The last clear and comprehensive endorsement of the Artbank program’s purpose was provided in the 1991 update to its original establishment document, the Charter of Operations. The high-level objectives, as articulated on the Artbank program’s website to ‘provide direct support to Australian contemporary artists through the acquisition of their work; and promote the value of Australian contemporary art to the broader public’, remain reasonably well-aligned with the program’s stated purpose. While the department agreed to ANAO recommendations in 2006 to review the Charter, no review was undertaken and no equivalent overarching strategic plan, aligned with the current legislative framework, to implement the program’s purpose has been developed. Two operational strategies were developed in 2019 (and endorsed in 2019 and 2021) to focus on separate parts of the programs purpose, being the rental scheme and future artwork acquisitions. There is no overarching strategy to address the Artbank program’s purpose.

Purpose

2.2 Purpose statements should be succinct and make it clear why an entity or program exists, who benefits from its key activities and how they benefit. The Artbank program’s purpose was first set out in 1980 in its establishment document, the Charter of Operations. The charter, updated in 1991, by the Minister for the Arts, Sport, the Environment and Territories, stated that the scheme was ‘established to:

- encourage contemporary Australian artists by acquiring their work;

- stimulate a wider public appreciation of Australian art by making it available for display in public places, particularly work locations, throughout Australia and in official posts overseas;

- operate an Art Rental Scheme directed to both private and public sector clients; and

- manage the Artbank collection on behalf of the Commonwealth.’

2.3 The policy objectives for the Artbank program have remained relatively consistent since its establishment, and are currently articulated on its website as being to:

- provide direct support to Australian contemporary artists through the acquisition of their work; and

- promote the value of Australian contemporary art to the broader public.12

2.4 The 2006 ANAO performance audit of the Artbank program made recommendations regarding the strategic direction of the program, including that the 1991 Artbank program’s Charter of Operations be redrafted to align more closely to the broader legislative and governance frameworks in place at the time of the audit (see paragraph 1.3), including establishing program guidelines (or a business plan) setting out the way the Artbank program operates, as a departmental program. At the time of the audit, alignment was assessed against the then Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997, the legislative framework in place at the time. That framework has been replaced by the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013. The Charter of Operations has not been updated.

Funding model

2.5 The Artbank program was appropriated through the annual budget process for both artwork acquisitions and operational requirements until 1992. For the three years between 1989 and 1992 the appropriation to the Artbank program was limited, with the program to transition to its current ‘self-sustaining’ funding model.13 Under this model, rental revenue generated from the Artbank collection (and other receipts credited to its trust account14) would fund all activities, including the acquisition of new art.15

Strategy

2.6 The ANAO examined whether the department had a strategy in place clearly articulating how it directs activity against each of the program’s four objectives (see paragraph 2.2).

2.7 A program-wide strategy or overarching business plan has not been developed. A range of policy and planning documents have been approved since 2019 that focus on discrete parts of the program. Specifically, the policies include:

- 2019 Acquisition Policy (see paragraphs 2.22, 3.26–3.27, 4.63 and 4.66);

- 2019 Artbank Deaccession Policy (see paragraphs 4.6, 4.26–4.31, 4.34–4.35, 4.49–4.51, 4.53 and 4.63);

- Artbank Collection Plan 2019–21 (see paragraphs 2.9, 2.12, 3.6–3.8, 3.20, 3.26, 3.58, 3.60–3.62, 4.6, 4.55 and Case Study 1);

- 2021 Artbank Condition Checking Policy (see paragraphs 4.9–4.13);

- 2021 Artbank Client Leasing Policy;

- 2020 Artbank Business Plan (see paragraphs 2.8–2.9, 2.12, 4.6, 5.25–5.26, 5.35, 5.41); and

- 2021 Preservation Policy and Conservation Plan (see paragraphs 4.5–4.9, 4.25, 4.56–4.57).

2.8 The May 2020 Artbank Business Plan was developed in response to a decline in the recorded collection leasing rate from 70 per cent of artworks to ‘approximately 40%’. The plan was endorsed by the Artbank Governance Committee (see paragraphs 2.17–2.25) in January 2021, with the committee advised that there was ‘nothing similar in place previously’.16 This plan recognised that an increased leasing rate represented progress towards or achievement of part of the program’s purpose. Specifically: stimulating a wider public appreciation of contemporary Australian art through the art leasing program; and a ‘greater ability to live up to Artbank’s other core objective of supporting contemporary Australia artists and the visual arts sector through greater budget for the acquisition of new Australian contemporary art.’17 The Business Plan established goals and targets for the Artbank Rental Scheme based on historical rental data. The Business Plan did not include analysis of the expected impact the achievements of the goals and targets would have on the annual acquisition budget, nor on delivery of other aspects of Artbank program’s purpose.

2.9 The May 2020 Business Plan focused solely on establishing a target of increased rental collections, to 70 per cent of the collection. A collection plan (see paragraph 3.7) was first established in 2019 to guide acquisition decisions to address the gaps identified within the collection.

Performance measures

2.10 Performance measures, at the project, program and entity level, exist to provide a basis for tracking and reporting of progress towards agreed goals, and in turn, the achievement of government policy objectives. Examples of measures include: whether a service was delivered within a certain timeframe; whether it reached an agreed number of people or businesses; and whether it had a particular economic or social impact.18

2.11 The department has reported publicly against the Artbank program objectives from time to time. As illustrated by Figure 1.1, this reporting has been through the department’s annual reports. Reporting for the Artbank program was most recently included in the department’s 2020–21 Annual Report, in the annual performance statements.19 While no targets were set, the department reported on the: number of artworks purchased; number of artworks leased; and number of clients.20 These measures were to be removed after the 2021–22 annual report, with the 2022–23 Corporate Plan for the department noting that ‘the department [had] limited to no control over the outcome or [the] data was not available or reliable’.21,22

2.12 Reporting to the Artbank Governance Committee is limited to reporting against the endorsed Business Plan (leasing rate, number of new clients) and annually updated collection plans (number of new acquisitions, breadth of new acquisitions against the collection plan marker) (see paragraph 2.7–2.9). During the development of both the Collection Plan (in 2019) and Business Plan (in 2020), and early commencement of activities, the Governance Committee was also established. As such maturity of reporting against each plan, and to the governance committee has evolved over time. Notably, while the committee was expected to meet quarterly according to its terms of reference (12 times to date), the committee has only held three meetings since its establishment. While the detail and the data in the reporting has improved with each of the three meetings, it has not been considered by the committee on a regular basis as contemplated by the terms of reference.23 ANAO analysis of the Artbank program’s records against potential program metrics outline that the program’s performance has been progressively declining across a number of key aspects since 2015 (see Table 2.1).

Table 2.1: Measuring the Artbank program’s performance against its purpose

|

Financial year |

1. To encourage contemporary Australian artist by acquiring their work |

2. To stimulate a wider public appreciation of Australian art by making it available for display in public places particularly work locations throughout Australia and in official posts overseas |

3. To operate an Art Rental Scheme directed to both private and public sector clients |

4. To manage the Artbank collection on behalf of the Commonwealth |

||||||

|

|

# of Artworks purchased and value |

# of Artists artwork is purchased from |

# of artworks purchase from gallery: artist: other |

# of artworks leased in public places: private offices: overseas postsa |

# of public access exhibitions held by the Artbank program |

# of artworks available for rental |

# of Public Clients : Private Clients |

# of Artworks leased |

# of Artworks under Conservation activity |

# of Artworks deaccessioned |

|

2015–16 |

116, $365,983 |

79 |

85:16:15 |

992 : 2556 : 952 |

6 |

10,452 |

69:402 |

4824 |

Unable to provide |

4 |

|

2016–17 |

179, $507,993 |

119 |

103:68:8 |

1085 : 2613 : 1026 |

2 |

10,626 |

75:407 |

5091 |

1 |

|

|

2017–18 |

121, $408,808 |

73 |

83:36:2 |

1037 : 2587 : 1053 |

4 |

10,782 |

66:377 |

5027 |

9 |

|

|

2018–19 |

65, $379,348 |

57 |

42:17:6 |

919 : 2340 : 1012 |

4 |

10,837 |

63:351 |

4573 |

0 |

|

|

2019–20 |

66, $355,415 |

55 |

45:13:8 |

801 : 2118 : 1015 |

5 |

10,873 |

60:322 |

4138 |

12 |

0 |

|

2020–21 |

52, $296,375 |

55 |

36:4:12 |

733 : 2120 : 747 |

3 |

10,968 |

46:313 |

3864 |

19 |

5c |

|

2021–22 |

75, $390,962 |

42 |

54:14:6 |

857 : 2328 : 882 |

10b |

11,002 |

60:331 |

4336 |

10 |

22c |

|

Total |

674, $2,710,384 |

480 |

448:168:57 |

1995 : 4971 : 1509 |

34 |

N/A |

N/A |

7669 |

41 |

74 |

Note a: These numbers do not add to the total number of artworks leased as artworks leased to private individuals (private residences) have not been included in these figures. Lease arrangements may cease throughout a year, and artworks may be leased to different clients in different locations in the same financial year.

Note b: In 2021–22, the Sydney office’s window display was updated with a curated staging of selected artworks on 8 separate instances. These window displays can be viewed from the street by passers-by. While not exhibitions in the traditional sense, these displays do make the work available in public locations.

Note c: Three plinths were removed from this figure in 2020–21 and 30 were removed from 2021–22. These were lost or destroyed in the 2014 change in Sydney offices.

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental records.

Recommendation no.1

2.13 The Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts implement an overarching business plan or wholistic program-wide strategy that articulates how the Artbank program will achieve each of its purposes and objectives, including details on how performance will be measured and reported.

Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts response: Agreed

2.14 The Department appreciates the value an overarching program-wide strategy would provide to the Artbank program. The Department envisages the development of such a plan would sit within the Artbank Charter (as currently in force) and the policy objectives contained within it.

How is performance of Artbank against purpose and strategy managed?

The Artbank Governance Committee was established in November 2019 to oversight the program’s activities; monitor achievement of key activities; and review compliance with government rules and processes. The committee did not meet quarterly in accordance with its terms of reference. As of December 2022, the committee had met three times. This diminished the management of the performance of the Artbank program against its purpose and operational strategies.

2.15 Effective governance arrangements drive accountability for performance by allowing appropriate oversight of program or policy delivery. Establishing and defining the group or body that is to provide this oversight — consistent with relevant legislative requirements — and setting formal expectations for reporting to it by management are important elements of these arrangements.24

Governance oversight

2.16 A terms of reference document (or charter) provides a single reference point that clearly sets out roles, responsibilities and accountabilities, and should be a living document subject to thoughtful consideration and periodic review.25

2.17 The Artbank program’s Charter of Operations established the Artbank Board in 1980, which played an advisory role for the scheme until 2015.26 Its charter was last updated in 1991.

2.18 The Artbank Board was abolished in 2015 as part of the Australian Government’s Smaller Government Reform Agenda.27 The department relied on internal governance lines of oversight, with no replacement governance oversight board or committee implemented until November 2019.

2.19 The Artbank Governance Committee was established in November 2019. The committee’s terms of reference include that the committee is to provide governance oversight for the program’s activities and monitor whether the Artbank program is meeting key objectives and is compliant with government rules and processes. The 1991 Charter of Operations remained unchanged. The Governance Committee’s terms of reference do not refer to the Charter.

2.20 In November 2019 the Artbank Governance Committee (the committee) was established, its inaugural meeting held, and its terms of reference endorsed. This departmental committee is chaired by the Deputy Secretary responsible for the Artbank program, and includes the Chief Financial Officer, the Chief Operating Officer, and representatives from the governance and risk sections of the department.

2.21 The committee’s terms of reference stated that the committee ‘is responsible for the governance oversight of Artbank’s activities, including: acquisitions to and deaccessions from the Artbank collection; the outreach and promotion of Artbank’s collection including its exhibition program and partnership agreements; and Artbank’s leasing scheme.’ The November 2019 meeting minutes recorded that the committee did not consider itself to be an ‘approving committee’. Instead, the committee noted that it is ‘one that ensures [that] Artbank’s functions are compliant and provide support to the Chief Financial Officer for information on assets’; and ‘is a conduit to the [department’s] Executive Leadership Team and the Secretary’s Business Committee, providing assurances to them that Artbank is meeting key objectives and complies with government rules and processes’.

2.22 The terms of reference also stated that the committee will, among other things:

- ‘meet quarterly’;

- the committee has met a total of three times since it was established, November 2019, January 2021 and March 2022. If the committee had met quarterly, it would be expected that the committee would have held 12 meetings since establishment in November 2019;

- ‘provide guidance around the strategic direction and oversight of the Artbank program to ensure efficient and effective delivery of quality outcomes’;

- ‘review and endorse Artbank’s policies and strategies’;

- see paragraph 2.7.

- ‘regularly monitor Artbank’s leasing activity; and all acquisitions to ensure that they meet the Acquisition Policy’. The committee has:

- reviewed the Acquisition Proposal template form in 2019;

- receives reports from the Artbank program on leasing and acquisitions activities completed since the previous meeting.

- ‘endorse all deaccessioning recommendations prior to being provided to the appropriate delegate for approval’; and

- the committee approved a range of deaccessions in March 2022.

- ‘endorse the annual budget for acquisition of artwork to the Artbank collection.’

2.23 The Artbank program team prepares reports for the committee in advance of its meetings. These reports have been growing in maturity and detail (see paragraph 2.12) across the three iterations prepared for and reviewed by the committee, and report on progress against the discrete purposes and plans.

2.24 In the absence of other records or out-of-session considerations, it is not clear how the Artbank Governance Committee has discharged its duty of being ‘responsible for the governance oversight of Artbank’s activities’ with yearly meetings (on average).

Recommendation no.2

2.25 The Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts ensures the Artbank Governance Committee appropriately monitors the Artbank program’s performance against its purpose and objectives, as set out in the committee’s terms of reference.

Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts response: Agreed.

2.26 The Department is committed to the good governance (ie transparency, effectiveness, accountability and participatory governance processes) of the Artbank program including monitoring Artbank’s performance against the measures articulated in an overarching program-wide strategy. A return to more normal conditions post-pandemic will include resumption of convening governance committee meetings in line with the Artbank Governance Committee’s terms of reference.

3. Acquisition approach

Areas examined

The ANAO examined whether artwork acquisitions have been consistent with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) and the policy intent of the Artbank program.

Conclusion

The department’s approach to acquisitions under the Artbank program has not been in accordance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) and has not demonstrated strong alignment with the targets established in the program’s collection plan designed to illustrate the department’s strategy to deliver against the program’s policy intent. Key shortcomings in the acquisition approach were: no open or competitive processes; value for money not being documented or demonstrated; and limited public reporting. Alignment with the program’s purpose and objectives was not evident due to deviations from the department’s Collection Plan for the Artbank program.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at improving and publishing upcoming procurement activities for the Artbank program on AusTender and demonstrating value with relevant money by implementing open and transparent processes for Artbank collection acquisitions.

3.1 Under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), an entity’s accountable authority has a duty to promote the proper (efficient, effective, economical and ethical) use and management of public resources. The Finance Minister issues the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) under the PGPA Act for officials to follow when performing duties in relation to procurement. The CPRs govern how entities buy goods and services and are designed to ensure the government and taxpayers get value for money. The acquisition of artworks for the Artbank program is a procurement activity governed by the CPRs.

3.2 In May 2006, an ANAO performance audit of the Artbank program28 included three recommendations that were agreed to by the department in respect of its artwork acquisitions (see paragraph 1.3). The areas that those recommendations sought to address remain relevant to the findings of this audit, and in summary, were aimed at:

- establishing and publishing acquisition criteria based on the collection needs and endorsed policy direction;

- improving the transparency of, and accountability for, acquisitions by documenting the reasons that artworks were selected against the acquisition criteria and publishing purchases above $10,000 on AusTender; and

- developing strategies, as an arts support program, to engage directly with artists.

3.3 Procurement continues to be a core activity for the Artbank program, with 674 new artworks acquired for the Artbank collection between 2015–16 and 2021–22, according to the Artbank program’s records as at 27 July 2022.

Is the acquisition approach in accordance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules?

The department’s acquisition approach for the Artbank program has not been undertaken in accordance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules. Shortcomings in the approach include:

- while value for money is the core rule of the CPRs, there is no available evidence demonstrating that value for money has been considered by the department throughout its acquisition process;

- while there is a collection plan to identify acquisition needs, it lacks measurable targets and has not been used to guide acquisition activity;

- the department does not undertake open and transparent procurements, undertake and record comparative assessments of potential acquisitions, including assessing value for money, in its acquisition process for procurements under the Artbank program; and

- since 2015–16, 379 (76 per cent) acquisitions of artworks each valued at less than $10,000 and four (12 per cent) acquisitions of artworks valued at more than $10,000 did not have clear, recorded delegate approval. There was a marked improvement in the recording of delegate approval on all acquisitions after 2019–20.

Planning the procurement

Determining a need

3.4 The CPRs state that a procurement begins when a need has been identified and a decision has been made on the procurement requirement.29

3.5 The need to procure artworks for the collection has existed since the Artbank program was established in 1980 (see paragraph 2.2).

3.6 The Artbank Collection Plan30 was first developed in July 2019.31 The plan is used to refine the program’s acquisition needs by establishing ‘five primary markers of breadth’ against which to assess the collection profile. From this assessment, gaps identified across these markers were to be used to refine the requirements for and basis of acquisition decisions each year. The Collection Plan is intended to:

enable[s] the Director and the curatorial team to recommend acquisitions based on an assessment of the current collection strengths, collection gaps, client service requirements and an understanding of the future direction of the Australian contemporary art market.

3.7 The breadth markers, which have remained consistent across each version, are:

- artwork medium (collection area);

- regional distribution;

- diversity demographics of artist;

- career stage; and

- market (from which art is acquired).

3.8 Targets associated with each ‘breath marker’ have been established to support program goals around collection diversity. These breadth markers can be used to measure degree of direct support provided to artists through the program’s acquisitions (see paragraph 3.62). ANAO’s analysis is that the requirements established in the Collection Plan, at the program level, were not effectively used to scope the individual procurements undertaken or any approaches to market. Performance against each of these breath markers is included in 3.60–3.62, Figure 3.4 and Figure 3.5. ANAO’s analysis is that the program’s performance has not been closely aligned to the goals and targets established.

Estimating the value of the procurement

3.9 The department has a procurement-related Accountable Authority Instruction (AAI) established in accordance with section 20A of the PGPA Act.32 Updated from time to time, the July 2020 AAI sets out that officials undertaking a procurement must, among other things:

- comply with the department’s Procurement Guide and other relevant AAIs, policies and procedures; and

- estimate the expected value33 of the procurement before deciding the appropriate procurement method: open tender or limited tender.

3.10 The expected value is used to identify which procurement method must be adopted, and accordingly, which sections of the CPRs apply to the procurement. Specifically, for non-corporate Commonwealth entities including the department, procurements (other than those for construction services) with expected values of more than $80,000 (GST inclusive) must be conducted by open tender and in accordance with both Divisions 1 and 2 of the CPRs.34

3.11 For procurements below this threshold, the department’s AAI outlines that where procurements are valued:

- at or above $10,000 and under $80,000 (GST inclusive), ‘officials should undertake market research and seek sufficient quote(s) to be satisfied that value for money is achieved with the chosen supplier. The number of quotes will depend on the nature of the procurement and familiarity with the market’; and

- under $10,000 (GST inclusive), ‘officials can obtain a quote or quotes via phone, online or email.’ 35

Selecting the procurement method

3.12 Consistent with the AAI, the department’s Procurement Guide encourages officials to conduct research to, among other things: understand the market and what competition exists; and determine the type of approach to the market that is most appropriate to the particular circumstances. In addition to the estimated value of the artworks to be acquired, the characteristics of the Artbank program as an artist support program warrant careful consideration when determining the most appropriate procurement method to adopt, as required by the CPRs.

3.13 The internal budget for new acquisitions by the Artbank program has been set to at least $400,000 for each of the past six years (see Figure 3.1). While this provides a reliable estimate for annual planning of the program’s procurement activity, departmental records indicate that acquisitions have been ad hoc and not undertaken in a coordinated or open approach. The closed and uncoordinated approach to procurement is reflective of the lack of overarching program strategy to deliver against the program’s purpose. This approach is also at odds with the CPRs and the department’s procurement guide, which state that when a procurement is to be conducted in multiple parts with contracts awarded either at the same time or over a period of time, with one or more suppliers, the expected value of the goods and services being procured must include the maximum value of all the contracts.

3.14 While the department has typically acquired one or two artworks from each gallery it has purchased from in a single year, 34 works were acquired from a single gallery in 2017–18. Each individual artwork was less than $10,000 and while there was approval from the then Director of the Artbank program for the acquisition, the value for one of the three invoices (being for 32 works) was $43,636.36 The two other invoices were for $8200 and $5800 (each for a single artwork), leading to a cumulative total spend at that gallery of $67,636.

3.15 The department advised the ANAO in November 2022 that it relies upon research and ‘the expertise of the program’s curatorial staff gained from tertiary qualifications and visual art sector experience to identify suitable works for potential acquisition into the Artbank collection.’ These works have predominantly been identified through professional market knowledge and experience to:

… assess [works] on a consistent basis throughout the year [identified through]:

- Catalogues in hard copy and digital format

- Individual submissions from galleries and artists made to us

- Gallery visits

- Key art fair attendance and preparation

- Biennales

- Online festivals/ fairs (especially during the pandemic)

- Contemporary art journals

3.16 Rather than informing the decision about which procurement method would be appropriate to adopt, this research is used to identify artworks to purchase. The works identified as suitable for the collection are recorded in acquisition proposals and provided to the program delegate for approval. The department advised the ANAO in November 2022 that only the works intended to be acquired are included in these proposals as it would not be possible to document every work reviewed by the team.

Approaching the market

3.17 The department’s August 2021 Procurement Guide outlines that ‘Procurement Approval Requests’ (or procurement plans) are mandatory for all procurements, with the format of that approval or plan depending on the value, risk and complexity of the activity. Regardless of the format, it must contain sufficient information on the project objectives, methodology and risk for the delegate to make an informed decision about whether undertaking the procurement would be value for money. This includes documenting and agreeing the procurement method to be used before approaching the market.

3.18 Approvals to approach the market (procurement plans) have not been documented for Artbank program-related procurement activities. Other Artbank program specific policies and strategy documents do not address how the art market is to be notified of a procurement opportunity or are otherwise to be approached to participate. Nor do they refer to, or otherwise seek to promote open, competitive and transparent processes. Accordingly, no coordinated approaches to market, or open calls for submissions from artists (or their representatives) have been employed.37 The description included in the Artbank Acquisition Strategy of the procurement method to be employed was limited to:

The Artbank collection can be acquired through purchase … Artworks are primarily purchased by Artbank on the primary market from Australian artists or their appointed agents (including galleries and dealers)’.

3.19 The department agreed to an ANAO recommendation in 2006 (see paragraph 1.3) to ‘consider alternative acquisition strategies to engage directly with artists [including], for example, a set period for submissions, an annual round similar to the Artbank Canada approach38 and/or a competition.’39 In response to an ANAO query seeking to confirm if the department had conducted an open call for applications, the department advised the ANAO, in November 2022 other than the now disbanded Roadshow program (see paragraphs 3.21–3.22 and Table 3.1), the department relies on the ‘existing visual arts infrastructure’ and considered it better relying on existing network of artist run initiatives, galleries and dealers. The department’s approach of visiting galleries and art fairs and identifying and selecting works for acquisition from an undocumented cohort of galleries does not support accountability and transparency in its processes. The lack of an overarching program strategy enables the department’s uncoordinated and closed approach to acquisitions.

3.20 Although the CPRs do not require artworks to be procured via an open tender, an open approach would afford potential suppliers fair and equitable access to opportunities to compete for the purchase of their work. Such an approach would also enhance the transparency and integrity of the department’s processes. While a public version of the Artbank Collection Plan40 is available on the Artbank program’s website, the annual procurement activities associated with it are not included in it or foreshadowed as part of the department’s annual procurement plan on AusTender.41

Artbank Roadshows

3.21 The majority of art has been acquired from commercial galleries, with the identification of those galleries selected and approached not recorded. The closest resemblance to a documented process for identifying potential acquisitions were the Artbank program’s series of ‘roadshows’ (see Table 3.1), conducted in 2016–17, 2018–19, 2020 and 2021. This involved departmental officials travelling to selected metropolitan and regional locations for artists to ‘pitch’ their work. While this approach has the potential to be consistent with the CPRs, the available records did not capture the full list of applicants; how artists were selected for interview from those who had applied; or identify whether any assessment was undertaken to inform acquisition decisions. Within the details that were captured by the available records, there were inconsistencies between what was recorded as to be purchased and which artworks were physically acquired.42

3.22 As illustrated by Table 3.1, Roadshows have generated a declining number of applications each year, with a significant reduction in the number of interviews and resulting acquisitions (in terms of both the number and value, and also as a proportion of total acquisitions each year).

Table 3.1: Key Roadshow metrics 2016–2017 to 2021

|

Roadshow Year |

# of Applicants |

# of Interviews |

# of Acquisitions from Roadshow |

Value of Roadshow Acquisitions |

|

2016–17 |

558 |

292 (52.33%) |

40a |

$108,616.10 |

|

2018–19 |

393 |

172 (43.77%) |

9b |

$30,445.22 |

|

2020 (Covid Impacted) |

167 |

15 (8.98%) |

4c |

$9,966.37 |

|

2021 (Covid Impacted) |

24d |

5e (20.83%) |

3f |

$7,391.00 |

Note a: With the exception of Alice Springs and Kandos, at least one artwork was acquired from each of the cities visited on the 2016–17 Roadshow. Of the 518 unsuccessful applicants, there were acquisitions totalling $58,769 from 11 of these artists at later dates: two in 2018 ($10,877), three in 2019 ($17,421), two in 2021 ($3100), and four in 2022 ($27,371).

Note b: Of the nine artworks acquired: one was from an artist already included in the Artbank collection; and another was from an artist for which there is no record of an interview. Of the 384 unsuccessful applicants, there were acquisitions totalling $13,056 from five of these artists at later dates: two in 2020 ($4700), two in 2021 ($4165), and one in 2022 ($4191).

Note c: Of the four artworks acquired, two were acquired from artists for which there is no record of an interview being conducted, $5555 of the total acquisition value. Of the 163 unsuccessful applicants, acquisitions were made from three of these artists later in 2022, for a total value of $26,091. For two of these subsequent acquisitions, the ANAO could not identify evidence indicating that Artbank program officers interviewed the artist during the 2020 Roadshow.

Note d: In November 2022, the department advised ANAO, in response to a request for updated data for the 2021 number of applicants and interviews that 25 submissions were received. ANAO can only locate 24 submissions in the department’s records.

Note e: This round of the program was only open to applications from artists in Canberra. The interviews were conducted using online video conferencing. The five interviews held includes a scheduled interview with an artist where no 2021 application can be located.

Note f: Two of the three artworks were acquired from new artists who were interviewed during the 2021 Roadshow. The other artist who had work acquired through the 2021 Roadshow was previously represented in the Artbank collection, with a work acquired in 1989 (the piece was since deaccessioned). An alternative work from this artist was identified for provisional acquisition into the collection in August 2022, with a value of $2800 that has yet to be accessioned (as of January 2023).

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental records

Unsolicited proposals

3.23 The department advised the ANAO in August 2022, that the Artbank program is open to, and does receive, unsolicited submissions directly to the Artbank program’s Curator and Director by way of: email; direct conversation at galleries; social media direct messaging; and word of mouth. These unsolicited proposals have not been documented, formally assessed or their associated risks outlined and reported upon. It is not clear which acquisitions, or how many, have resulted from unsolicited proposals.

3.24 In response to ANAO’s request to confirm or provide data on the number and assessment of unsolicited submissions and the number of acquisitions stemming from these submissions; the department did not provide any data, or figures outlining the number of unsolicited submissions or the number of acquisitions. Instead, the department noted that:

Of the unsolicited artwork acquisition suggestions, we receive from individual artists – none have been purchased for the last four years since the current senior curator commenced employment. This is predominantly because the work is not of a standard suitable for Artbank – the artist may be before what we would call even the emergent phase of a professional career not only in artistic merit, but also in artistic scale and ambition. We have acquired works from more established artists through unsolicited donation, with donations going through the Cultural Gifts program (so the artist gets a financial return in the form of a tax break) – because they are artists working at a standard and scale suitable for Artbank – i.e. highly rentable.

Identifying artworks to acquire

Evaluating candidates for acquisition, including the value for money proposition

3.25 Under the CPRs evaluation criteria should be included in relevant request documentation to enable the proper identification, assessment and comparison of submissions on a fair, common and appropriately transparent basis.43

3.26 The Artbank Acquisition Policy contains eligibility criteria that all artworks must meet to qualify for purchase through the program. If used in conjunction with one another, the Acquisition Policy and Collection Plan could provide a framework from which to develop appraisal criteria for evaluating acquisitions.44 The CPRs outline a range of factors to consider when assessing value for money45, including whole of life costs46 and benefits, and fitness for purpose. In addition to these, the Artbank program’s specific business requirements include considerations such as: rentability and appeal to client base; alignment with collection goals; suitability to the rental nature of the collection; and collection management considerations.47

3.27 As illustrated by Case Study 1, the department does not undertake a transparent assessment and comparison of available artworks. Instead, ‘Acquisition Proposals’ are generated only for the preferred artworks already determined by Artbank program officers. The considerations applied and basis for these determinations by the Artbank program officers have not been documented. Acquisition proposals consider only the single preferred work and include: an assessment against eligibility criteria; and narrative commentary from the officers managing the art rental scheme, the officer responsible for the storage and maintenance of the collection, and from the curatorial team. The recorded comments are limited to views on the eligibility criteria in the Artbank Acquisitions Policy, specifically: rentability; storage; conservation and installation considerations; and artistic merit. The proposals do not:

- consider alternative artworks, or alternatively, apply a score against a baseline standard expected for the program’s acquisitions;

- inform the delegate on how the work was identified and selected;

- include a value for money assessment; and

- apply weightings to the considerations provided by the three program teams. There is no evidence that comparative analysis is applied to the considerations and selection of artworks for acquisition to demonstrate competition.

Approval by the delegate

3.28 Since October 2018, Acquisition Proposal templates have been completed by the program’s curatorial team when seeking delegate approval to acquire an artwork.48 A proposal is developed only for artworks that have been selected for acquisition (see paragraph 3.27). The ANAO has not identified any acquisitions proposals where the delegate has sought further information, such as:

- references in these proposals to suggest other artworks have been considered, or that the program officers considered some works to be more meritorious or more value for money than alternative artworks; nor

- evidence of any assessments of works considered but determined not to be a suitable or appropriate acquisition.

3.29 This approach limits the delegate’s ability to make an informed decision as it does not provide a comparative assessment between alternatives on which the delegate’s decision and approval should be based.

3.30 Almost all acquisition proposals provided to the delegate for approval are approved. For the two instances where proposals were not approved (between 2019 and 2022), the basis for this decision was not recorded on the acquisition proposal.

3.31 The department advised the ANAO in September 2022 that since 2019, the approach to evaluation of potential acquisitions involves whole of program office discussions to compare the relative merits of artworks being considered. The department further advised in November 2022 that these meetings are held weekly and if out of session discussion is required, for example ‘during an art fair where decisions need to be made quickly to secure works’, then the curatorial team may discuss the works at other set meetings or ‘convene an urgent ad hoc meeting of all staff available’.

3.32 These discussions have not been recorded, and consistent with previous practices, the details of the artworks or artists that were not proposed to the delegate for approval were not recorded. The lack of documentation around key decisions, including how value for money was determined is not consistent with the CPRs and does not promote transparency and accountability.

3.33 In response to the ANAO’s queries in August 2022 about written comparative evaluations and value for money assessments, the department adjusted its approach by recording in writing at a September 2022 program office meeting the group of artworks to be assessed and considered to determine which work or works to propose to the delegate for approval. Case Study 1 provides an overview of this process.

|

Case study 1. Artbank program all staff acquisition meeting in September 2022 |

|

Artbank program officials held an acquisition meeting to discuss potential acquisitions identified at the Sydney Contemporary art fair. Information on seven artworks from six artists were compiled and circulated to all 13 attendees. The information included: artist name, location, artwork title and details, purchase price and expected rental price. A new artwork was introduced during the meeting that was not previously in the list circulated. Three decisions-makers were identified in the meeting records: the Artbank program Director, Curator and Assistant Curator. The other 10 staff in attendance participated in the discussion. Records from the meeting indicate that votes were taken against each artwork, with staff in attendance to indicate whether they agreed that that artwork was suitable for the collection or not. While concerns and other comments were noted, they were not clearly linked to assessment criteria nor the expertise of the staff making the contribution (see paragraph 3.26). Where comments were reported to be ‘overwhelming yes’ there were no documented comments on the rentability, conservation needs/requirements of the work; alignment to Collection Plan; or any other value for money considerations. Of the eight works considered in the meeting, six works were agreed by the majority of the officials in attendance to be ‘suitable for the Artbank Collection’. It is not clear from these records how this suitability was determined; which of the six works were to proceed to Acquisition Proposal; at what point a value for money assessment would be completed; and how (and when) the Artbank Collection Plan and budget limitations would be considered when determining which works to acquire, and where these decisions would be recorded. |

3.34 There would be benefit in the department examining the acquisition approach taken by other similar entities as well as entities such as the Australia Council. For example, both Canada Council for the Arts and the Australia Council employ open funding rounds and identify successful applicants through a peer assessment process.

Recording the procurement decisions and approvals

3.35 Consistent with the CPRs, the department’s Procurement Guide requires officials to document how value for money was considered and achieved, including sufficient information to justify the recommendations to the delegate on the procurement outcome. In particular, documentation for each procurement should capture:

- the requirement for the procurement;

- the process that was followed;

- how value for money was considered and achieved;

- relevant approvals; and

- relevant decisions and the basis for those decisions’.49

3.36 Records of approvals and rationale for decisions, especially for artworks acquired for a value less than $10,000 were not available for all acquisitions.

3.37 Since October 2018, all artworks acquired have required the Acquisition Proposal template to be completed, and written approval from the delegate, Assistant Secretary Creative Industries which is recorded by their signing the template (see paragraph 3.27). The template does not include any reference to ensuring and recording how value for money was achieved in the absence of a competitive process.

3.38 Prior to October 2018, according to the department’s financial delegations, the Artbank program’s Director had delegated authority to approve a commitment of money and to enter into, vary and administer arrangements, providing the terms and basis of the approval were recorded and the delegation was exercised in accordance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules.

3.39 The administrative processes and arrangements specific to the Artbank program in place prior to 201950 limited the Director’s authority to commit up to $10,000 excluding GST.51 For acquisitions greater than this, it was the Artbank program’s policy that an Acquisition Proposal52 be developed by the Artbank Curatorial team, endorsed by an EL1 equivalent53 and by the Director, before seeking approval from the Assistant Secretary responsible for the Artbank program. As set out in Table 3.2, there are a number of acquisitions where the ANAO was unable to locate written evidence of delegate approval.

Table 3.2: Acquisitions for the Artbank program: 2015–16 to 2021–22

|

Year |

Total acquisitions |

Acquisitions greater than $10,000 |

Acquisitions equal or less than $10,000 |

|||||

|

|

# |

Invoice amount |

# |

Invoice amount |

# with clear delegate sign off |

# |

Invoice amount |

# with clear delegate sign off. |

|

2015–16 |

116 |

$365,983 |

2 |

$25,345 |

0 (0%) |

114 |

$340,637 |

3 (3%, 5% of invoiced amount) |

|

2016–17 |

179 |

$507,993 |

5 |

$97,152 |

5 (100%) |

174 |

$410,841 |

2 (1%, 2% of invoiced amount) |

|

2017–18 |

121 |

$408,808 |

3 |

$80,916 |

2 (67%, 57% of invoiced amount) |

118 |

$327,892 |

63 (53%, 33% of invoiced amount) |

|

2018–19 |

65 |

$379,348 |

7 |

$152,038 |

6 (86%, 93% of invoice amount) |

58 |

$227,310 |

21 (36%, 32% of invoiced amount) |

|

2019–20 |

66 |

$355,415 |

7 |

$138,745 |

6 (86%, 78% of invoice amount) |

59 |

$216,670 |

58 (98%, 98% of invoiced amount) |

|

2020–21 |

52 |

$296,375 |

6 |

$117,797 |

6 (100%) |

46 |

$178,578 |

46 (100%) |

|

2021–22 |

75 |

$396,462 |

8 |

$152,545 |

8 (100%) |

67 |

$243,916 |

67 (100%) |

|

Total |

674 |

$2,710,384 |

38 |

$764,540 |

30 (88%, 89% of invoice amount) |