Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Acceptance into Service of Navy Capability

The objective of the audit was to report on the effectiveness of Defence’s approach to the acceptance into service of Navy capability, and to identify where better practice may be used by CDG, DMO and Navy.

Summary

Introduction

1. The Australian Defence Force (ADF) is currently midway through a major Navy capability acquisition program. Each new Navy capability project aims to respond effectively to changing defence strategic circumstances, to exploit technological advances to achieve system performance and quality requirements, while making cost-effective use of defence resources.[1]

2. The Navy capability projects underway today are the forerunners of potentially much larger acquisitions outlined in the Government’s 2009 Defence White Paper. The White Paper indicates the Government’s intention to further modernise and enhance the Royal Australian Navy (Navy), so that by the mid 2030s the Navy:

… will have a more potent and heavier maritime force. The Government intends to replace and expand the current fleet of six Collins class with a more capable class of submarine, replace the current Anzac class frigate with a more capable Future Frigate optimised for ASW [anti submarine warfare]; and enhance our capability for offshore maritime warfare, border protection and mine countermeasures.

3. The development of Navy capability involves, in the first instance, Defence’s Capability Development Group (CDG)[2] defining Navy’s capability requirements in accordance with strategic guidance and in consultation with Navy and other stakeholders. These requirements then form the basis for the development of options for consideration by government.

4. The Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO) is responsible for acquiring and sustaining the Mission System and Support System elements of defence capability approved by government. DMO manages and oversees the processes by which private sector firms design, manufacture and test Mission Systems and their Support Systems in accordance with function and performance requirements defined by CDG, the regulatory requirements defined by Navy, and the ‘readiness’ and ‘sustainability’ requirements directed by the Chief of the Defence Force (CDF).[3]

Delivering Navy capability

5. Delivering Navy capability into service is a large-scale, complex and critical undertaking, requiring close management of each capability project’s planning, acquisition and acceptance phases. It typically involves the coordinated and integrated effort of several large Defence and private sector organisations, with capability outcomes dependent on management being well positioned to identify whether projects are progressing as planned and to respond to emerging issues. Project risks need to be managed by all parties, with all organisational relationships focused on delivering the specified ADF capability within the approved cost and schedule.

6. The management arrangements for planning, acquiring and accepting Navy capability have been subject to significant changes over several decades. Since 1984, capability definition and systems development and maintenance historically performed by Navy, have been progressively transferred to other Defence Groups, and to the private sector under contract. Navy now relies on CDG and DMO to define, acquire and support its ships and submarines. In turn, DMO contracts the private sector to undertake the design and construction of Navy ships and submarines, and also to provide them with deep-level maintenance.[4] DMO also relies on private sector Classification Societies[5] to certify that Navy’s ships comply with various International Maritime Organisation design, construction and maintenance regulations.

7. As part of the Defence Reform Program, the Defence Executive in July 1998 announced a fundamental review of Defence’s capability management principles and practices across the whole capability continuum to ensure the ‘seamless management’ of whole-of-life capability.[6] The Defence Executive decided that seamless management would require it to:

… establish the appropriate underlying processes and systems needed for this, and we will assign capability output managers who are responsible for delivering effective capability. The result will be that our systems meld together all of the elements that go into building an effective defence force - people, equipment, training, acquisition, doctrine, logistics, disposition, facilities and so on.[7]

8. The following years saw continuing changes to Defence’s arrangements for achieving Navy capability. With the formation of DMO in July 2000, the acquisition and logistics support of Navy ships and submarines provided by DMO was decentralised from Canberra to DMO Maritime System Program Offices, usually located in dockyards around Australia. In 2002, new capability management processes incorporating two-pass government approvals were introduced by the then Vice Chief of the Defence Force. These processes were expanded by DMO’s adoption of more widespread systems engineering management practices, and later by the creation of CDG in 2004.

9. Over this period, Navy retained its historical responsibility for the safety and seaworthiness of its ships, and consequently for implementing technical and safety regulations. A new regulatory system was introduced by Navy in 2003.

10. Successful project management requires well-qualified and highly skilled project managers, backed by project and financial systems that provide immediate access to reliable and accurate information on project costs, schedule and performance.[8] While organisational responsibilities for delivering Navy capability have changed across the years, there has been wide acceptance of the need to complement effective project management with systems engineering principles.[9] Systems engineering involves the orderly process of bringing complicated systems into being through an integrated set of phased processes covering user requirements definition, system design, development and production, and operational system support.[10] Successful systems engineering is dependent on both technological expertise and management expertise:

the best tools/models may be available to implement [the systems engineering] process… however, there is no guarantee for success unless the proper organizational environment has been created and an effective management structure is in place. Top management must first believe in and then provide the necessary support to enable the application of system engineering methods… Specific objectives must be defined, policies and procedures must be developed, and an effective reward structure must be supportive.[11]

11. The criterion of success in Navy capability development is usually expressed as the acceptance into service of a Mission System (such as ship or submarine) as specified, on time and within budget. However, Navy capability comprises not only Mission Systems, but also other capability elements, collectively known as Logistics (or Support) Systems. These comprise maintenance planning, trained personnel, support equipment and maintenance spares, technical data and computer resources, facilities, transport and storage, and various other investments that contribute to the success of naval operations. Known in Defence as the Fundamental Inputs to Capability (FIC), DMO, CDG and other organisations in Defence play major roles in developing each capability input. All the inputs are not productive if Mission Systems are not available when required, are unfit for service, or pose unacceptable risks to personnel, public safety, and the environment.

12. Consequently, Navy capability development requires the delivery of both the Mission Systems and the other seven inputs that culminate in capability. The successful delivery of these inputs is dependent upon effective organisational structures, high standards of management cooperation and coordinated effort, supported by adherence to the best systems engineering practices available.

Audit objectives and scope

13. The objective of the audit was to report on the effectiveness of Defence’s approach to the acceptance into service of Navy capability, and to identify where better practice may be used by CDG, DMO and Navy. The audit included examination of:

-

CDG’s definition of Navy capability requirements;

-

DMO’s verification and validation that systems accepted from contractors comply with government approved requirements, and DMO’s compliance with Navy’s technical and safety regulations;

-

Navy’s certification that systems offered for release into operational service are fit for service, and only pose acceptable risks to personnel, public safety, and the environment, and Navy’s reliance on Classification Societies; and

-

Navy capability management and regulation.

14. This audit is intended to reinforce and inform the ongoing development of Navy capability acquisition and acceptance processes.

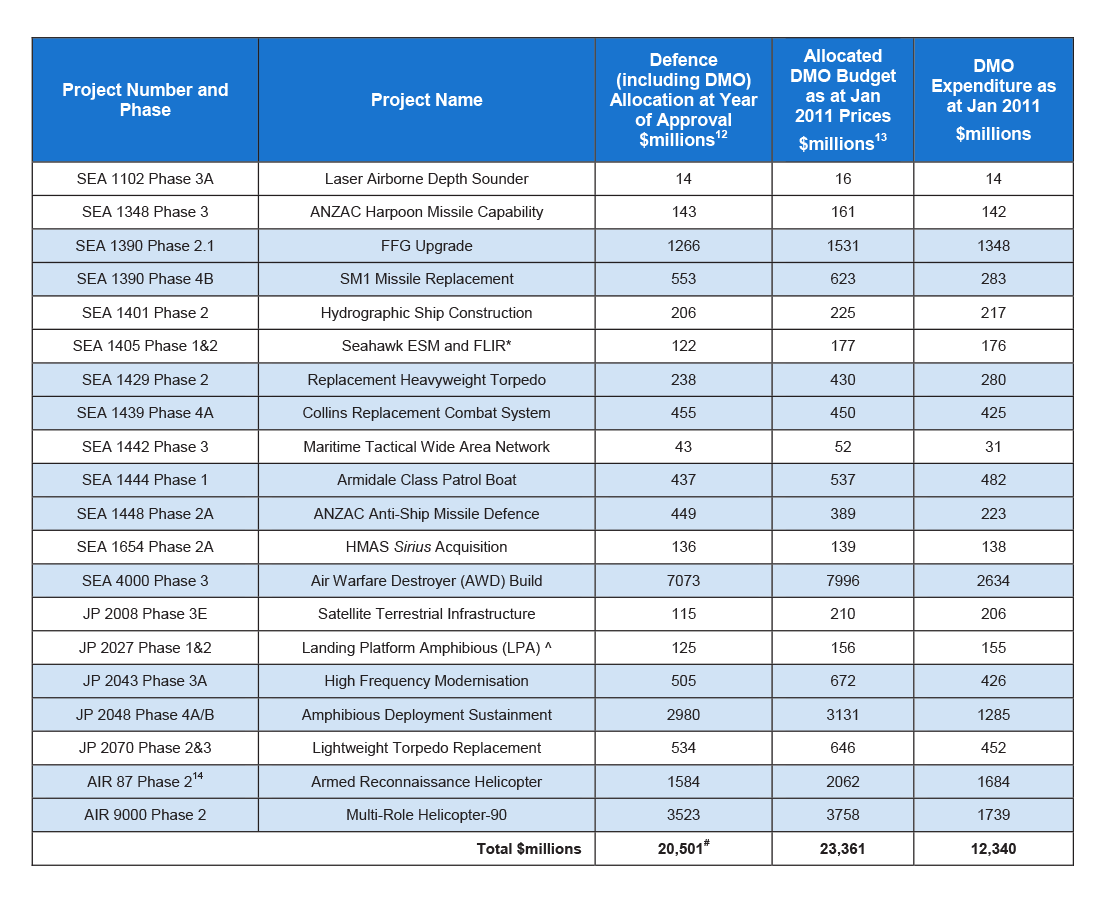

15. Table S.1 lists the projects considered by the ANAO during the course of this audit.

Table S.1: Projects and Approved Budgets and Expenditure as at January 2011

Source: Compiled from Department of Defence and Defence Materiel Organisation advice, June 2011.

Notes:

* Due to the project’s closure, the DMO figures are in January 2010 dollars.

^ Due to the project’s closure, the DMO figures are in September 2004 dollars.

# Aggregated total of the projects’ approved budgets, with their price basis based on individual project approval dates.

16. Of the 20 projects considered in this audit, 11 are also included in the DMO 2009–10 Major Projects Report;[15] these are shaded in light blue in Table S.1. Seven of the projects have previously been the subject of ANAO performance audits, which are listed in Appendix 2.

17. Eight of the projects have Mission Systems and Support Systems undergoing naval operational test and evaluation, as part of the Initial Operational Release phase.[16] A further seven projects have successfully completed Navy’s operational test and evaluation and have been accepted into naval service, a state now known as Operational Release.[17] Of the remaining five projects, four are progressing through their development and contractual acceptance test and evaluation phase managed by the DMO. In May 2011, the remaining project, the JP 2027 Landing Platform Amphibious (LPA) project, was in a seaworthiness remediation phase for one ship (HMAS Kanimbla) and a decommissioning phase for the other ship (HMAS Manoora).[18] In 2003, the LPA project entered its sustainment phase, on the closure of its acquisition phase.

18. Fieldwork for the audit was conducted from January 2010 to March 2011, at the Canberra central offices of CDG, DMO, and Navy. Interstate fieldwork was also conducted at the Navy’s Test, Evaluation and Acceptance Authority (RANTEAA) at Garden Island, Sydney; and at relevant DMO Project Offices. The audit team held meetings with United States of America (USA), United Kingdom (UK) and Canadian Defence authorities involved in Navy capability acquisition, test and evaluation and capability management. This enabled international comparisons of initiatives used to address particularly challenging management issues revealed by the audit.

Overall conclusion

19. Particularly since 1998, Defence has sought to put in place the seamless management of ADF capability from requirements definition through to withdrawal from service. After a series of changes to Defence’s organisational structures and processes, there is still some way to go before Defence achieves the objective of seamless, well-developed processes and systems underlying the effective and efficient delivery of Navy capability.

20. DMO, CDG and Navy have sought to design management practices based on better practice in the commercial and naval sectors. These include formally setting out their respective roles and management responsibilities, and adopting systems engineering as the basis for acquiring and supporting ADF capability.

21. However, the overall picture is of a capability development system that has not consistently identified and responded, in a timely and comprehensive way, to conditions that adversely affected Navy capability acquisition and support. Opportunities to identify and mitigate cost, schedule and technical risks have been missed, resulting in chronic delays in Navy Mission Systems achieving Final Operational Capability.[19]

22. At the highest level, the Acquisition Business Cases, project plans and inter-group agreements for some of the projects examined have not set out clearly the government-authorised parameters for each project in terms of scope, cost and schedule at the time of each project’s approval. Consequently, compliance with government requirements, which is a fundamental responsibility of Defence, could not be confirmed by Defence.[20] In addition, other significant deficiencies which adversely affect the projects subject to this audit included:

- Navy as Capability Manager, and DMO as acquirer, not fully and formally setting out their respective roles and responsibilities in the form of comprehensive CDG-DMO-Navy Materiel Acquisition Agreements for all acquisition projects. This requirement was agreed to in 2009,[21] and developing these agreements for Navy projects has been a slow process, with completion now expected by December 2011;

- the process of gaining agreement on requirements and on the procedures for verifying and validating that equipment fully meets contractual requirements was not adopted as standard practice by DMO and Navy. The aggregation of the requirements specified in the three key Capability Development Documents (the Operational Concept Document, the Function and Performance Specifications and the Test Concept Document)[22] should align with Navy’s criteria for determining that materiel offered by DMO at the end of the acquisition phase matches the Government approval and is ‘fit for service’ — where fitness for service relates to the materiel’s ability to satisfy operational requirements.[23] The adoption of the essential systems engineering process of ensuring that agreement is reached on these matters at the outset of, and throughout, projects, is critical to facilitating the transition from acquisition to operational acceptance and is now being considered by DMO’s Standardisation Office;

- records of testing and evaluation, contractual acceptance, and configuration management were not maintained in a systematic and complete fashion by DMO. This practice is essential for capability acceptance, and for the provision of ongoing assurance that materiel remains fit for service and poses only acceptable risk to personnel, public safety, and the environment. This is a significant systems engineering deficiency and a regulatory non-compliance issue; and

- Navy’s administration of its technical and regulatory responsibilities, including verifying regulatory compliance, was not as complete and thorough as necessary in the circumstances. In some essential systems engineering, technical regulatory elements and capability integration management areas, there are insufficient numbers of qualified staff, and this needs to be addressed as a priority.

23. In such cases, Navy capability acquisition schedules have suffered, and continue to do so, with some materiel delivered to Navy having incomplete requirements verification and configurations records, resulting in difficulties in determining safety and fitness for service. It is evident that such problems have proliferated because of the lack of effective mitigation through the definition, acquisition and acceptance phases. The pathway to better capability outcomes here is reliant on clear up-front agreements on capability requirements definition, verification and validation procedures, and configuration management. These agreements, which would supplement the higher-level Materiel Acquisition Agreements, are necessary to minimise the likelihood of disagreement about the capability requirements expected to be delivered, and the adequacy of the validation and verification procedures applied to confirm delivery of these requirements, arising when a project is transitioning from acquisition to acceptance into service. Such agreements should allow the focus to be kept on resolving any capability deficiency that remains.

24. Analysis of project documentation by the ANAO shows overall project management improvements have occurred since around 2003, when Defence increased the application of systems engineering concepts to the requirements definition phase of its projects, resulting in better developed operational concepts, function and performance specifications and test concepts. Those improvements are reflected in Defence’s contracting template, which clarifies the accountability for design, and underscores the vital importance of progressive verification and validation that ADF capability requirements have been met. Of the 20 projects considered in the course of this audit, these improvements apply to the five post-2003 projects, and to a lesser extent to the remaining 15 pre-2003 projects,[24] as most often the improvements could not be fully retrospectively applied to these older projects.

25. Nevertheless, despite the improvements in requirements definition and verification and validation processes, there remains scope for improvements in process implementation that should further assist in achieving better capability outcomes. While some factors, such as those relating to industry capability, may be outside of Defence’s direct control, Defence’s Navy capability development management arrangements can be further improved. Customer-supplier agreements in the form of Materiel Acquisition Agreements that include the Navy Capability Manager as a co-signatory as well as CDG and DMO, were being developed during the course of this audit. Although long overdue,[25] these three-way agreements are expected to clarify the customer-supplier arrangements and create the conditions for projects to more smoothly transition from acquisition to acceptance into service.[26]

26. In an environment where project durations can extend over many years, it is not uncommon for technological advances to occur and/or operational requirements to change during a project’s course. It is to be expected that reasonable efforts are made to keep pace with those changes, including seeking prior necessary government approvals. It is also reasonable to expect that, from the systems engineering perspective, adherence to properly conducted configuration management processes will enable agreed changes to occur in a controlled manner.

27. Uncertainty regarding acquisition requirements and the adequacy of verification records needs to be avoided as far as is possible - especially for fixed-price contracts, where contractors are sensitive to changes, or perceived changes, in the contracted scope of work. This underscores the importance of Defence’s post-2003 policy of having in place, prior to contract signature, agreed Capability Definition Documents to serve as the basis for acquisition contract Statements of Work. It also underscores the key role of System Definition Reviews that enable timely agreement between DMO, Navy and contractors on acquisition requirements, and their verification and validation procedures.

28. When Defence contracts involve system design and development, the implementation of effective project management and systems engineering processes are central to achieving better outcomes. When the acquisition involves military off-the-shelf (MOTS) or commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) equipment that needs no further development or integration into other systems, Defence may choose to rely on the vendor’s systems engineering processes. However, it remains fundamental that senior responsible officials managing the definition, acquisition and acceptance phases of such equipment must have clear visibility of the key decisions, assumptions, and test and evaluation data that led the vendor to offer the equipment as off-the-shelf. In all cases, CDG, DMO and Navy would benefit from working more closely during important phases of the development of major systems; notably when systems are first specified, during the day-to-day management of construction of major systems, during acceptance and operational testing, and while verifying compliance with technical and operational regulations.

29. At key stages of each project, all parties would benefit from a definite agreed view of the risks that must be managed in order to achieve a successful outcome. Experience in the USA and the UK underscores the importance of the acquisition organisation and Navy working together to ensure that handoffs to Navy do not become ‘voyages of discovery’ in the final stages of the project.[27] Knowledgeable people need to be in position at the right time, to give proper consideration to each system-under-development’s functional, physical and regulatory requirements, as well as to the procedures used to verify and validate the achievement of those requirements. The overall aim is to ensure that projects move smoothly forward in the clear knowledge of the risks and issues that need to be managed at each point in time.

30. Ideally, cooperation between the parties would be underpinned by improved horizontal responsibility and accountability arrangements. For Defence’s current organisational and management models to work more effectively to deliver the anticipated efficiencies, there is a need for clearer, more specific agreements and accountabilities between the various organisations that assist the Chief of Navy to acquit his overall responsibility for delivering the Navy capability outcomes agreed to by government.[28] This is because the current customer-supplier model adopted by Defence results in the Chief of Navy having no direct authority over key Defence Groups (including DMO) that develop capability elements needed to achieve these outcomes.[29] This is a significant issue in any matrix management model such as that employed by Defence. At the time of the audit, CDF and the Secretary were considering proposed changes to Defence’s accountability and authority structure. [30]

31. As previously mentioned, the audit has highlighted that Defence’s objective of developing the ‘seamless management’ of whole-of-life capability still has some way to go. The approach currently employed has a number of gaps and accordingly there is a need for Defence to:

- improve the overall transition of Navy capability agreed to by government, from its capability definition phase, through its acquisition phase and into acceptance into operational service, by improving managerial control by Defence over the setting of the detailed Navy capability requirements flowing from government’s overall project approvals. This includes the formal endorsement of these requirements by CDG, DMO and Navy based on government approval at Second Pass, and the application of an authorised change management process (which includes obtaining government approval where required) for any changes to the project’s requirements and/or its test and evaluation program throughout the project’s life;

- improve its systems engineering processes and their efficiency through compiling, from existing documents, authoritative systems engineering guidance for use by all materiel projects. This would clarify and streamline what is expected of Defence personnel employed in systems engineering roles, and remove processes that are no longer cost effective in the delivery of capability;

- support the maintenance of adequate standards of requirements management and verification and validation, throughout each phase of Navy capability definition, acquisition and acceptance into service, by increasing the sharing of information on project requirements, and on the test and evaluation program used to verify and validate that project requirements have been fulfilled;

- effectively address significant systems engineering and technical regulation issues concerning Configuration Management, which have remained unresolved for over a decade; and

- strengthen the critical System Acceptance process by ensuring that the DMO delegate authorised to approve Systems Acceptance is an executive with seniority commensurate with the importance of the project, who is external to the Systems Program Office and who is designated in the Project Certification Plan.

32. The scale and complexity of projects to deliver Navy capability are key reasons why it is unsurprising that not all projects progress as planned, but these inherent characteristics of many Navy capability projects are also important reasons why Defence needs to improve its implementation approach, and related accountabilities, leading to acceptance into service of new or upgraded capability. The notion of seamless management of ADF capability initiated by Defence more than a decade ago is a sound concept, but more needs to be done to operationalise it and streamline existing approaches for accepting Navy capability into service.

33. In addition, it is evident from the audit that greater emphasis needs to be applied by Navy, CDG and DMO, in maintaining a shared understanding of the risks to the delivery of the Navy capability agreed to by government. Importantly, there also needs to be sharing of the responsibly for mitigating those risks, including in relation to implementing effective recovery actions, when issues arise that threaten the acquisition of that capability. Without the application of greater discipline by Defence in the implementation of its own policies and procedures (including by having the required technical personnel in place to execute these), improved communication and collaboration across the relevant parts of Defence during a project’s lifecycle, and the maintenance of adequate records to support appropriate monitoring of capability development performance, the necessary improvements in acquisition outcomes will not be achieved.

34. The ANAO has made eight recommendations designed to improve Defence’s management of the acquisition and transition into service of Navy capability, including reducing delays in achieving operational release of such capability.

Key findings by chapter

Chapter 2 – Capability management process development

35. The Defence Procurement Review 2003 (also known as the Kinnaird review) sought to strengthen Defence’s two-pass project approval process for acquisitions. It also led to the formation of the CDG in February 2004,[31] and to the DMO becoming a financially autonomous project management and service delivery organisation within the Defence portfolio in July 2005.[32] Under these arrangements the Service Chiefs relied on CDG, through the CDG-DMO Materiel Acquisition Agreement Process, to oversee, co-ordinate, and report on all elements necessary for the acquisition of ADF Mission and Support Systems.

36. The 2008 Defence Procurement and Sustainment Review (known as the Mortimer Review),[33] sought to improve the capability development process by, amongst other things, increasing the role of the Service Chiefs in the capability development and reporting process. However, the Chief of Navy presently has no direct authority over key Defence Groups (such as DMO) that develop capability inputs needed to achieve the capability outcomes agreed to by government for which he has overall responsibility. This is a significant issue in any matrix management model such as that employed by Defence.[34] CDF and the Secretary were considering proposed changes to Defence’s accountability and authority structure during this audit.[35]

37. As of February 2011, the Capability Managers’ role of bringing together all the fundamental inputs required to achieve the capability outcomes agreed to by government, had yet to be drafted into Project Directives for any of the 20 projects included in this audit.[36] Defence was producing Project Directives only for new projects currently being approved by government. With respect to the 20 projects included in this audit, Materiel Acquisition Agreements that include the Capability Manager had only been signed for the JP 2070 Lightweight Torpedo Replacement project. Consequently, the effectiveness of these new arrangements could not be examined during this audit.

Chapter 3 - Defining Navy capability requirements

38. Since 2003, Defence has made improvements to project management and the application of systems engineering concepts when defining the requirements for projects, resulting in better developed operational concepts, function and performance specifications and test concepts. Defence’s CDG is, among other things, responsible for defining Navy capability requirements in systems engineering terms. Since its formation in 2004, CDG has defined new or upgraded Navy capability through three key capability definition documents:

- the Function and Performance Specification, which specifies the functional characteristics of systems to be acquired, and the level of intended performance;

- the Operational Concept Document that sets out how the systems will be operated in their intended operational environment; and

- the Test Concept Document that sets out the tests that need to be conducted to demonstrate that the systems will comply with their specified requirements, and thus are fit for service and only pose acceptable risks to personnel, public safety, and the environment.

39. The ANAO found five of the 20 projects included in the audit were established after 2004, and each of these has approved versions of all three capability definition documents, as required by Defence policy following the 2003 Defence Procurement Review. The documents for the remaining 15 projects established prior to 2004 were to varying degrees less defined. For these projects, Defence was exposed to risks in gaining agreement with contractors (often a year or more into a fixed-price contract)[37] regarding Defence’s requirements for system function and performance, and on the test and evaluation procedures to be used to verify compliance with contractual requirements.

40. There remain opportunities for Defence to further improve its project definition process by including better coverage of Navy’s regulatory requirements, and more generally by improving the overall flow of the acquisition management process. To this end, DMO’s Standardisation Office has commenced developing a DMO Systems Engineering Manual which, although long overdue, should lead to improved systems engineering in DMO, from which it may be expected there would be better process interfaces with CDG and Navy.[38] It should also provide a basis for the application of standardised processes, which would assist Defence personnel to continuously improve their systems engineering skills and the delivery of defence capability.

41. Post-2004 projects such as SEA 4000 Phase 3 Air Warfare Destroyer project and JP 2048 Phase 4A Amphibious Deployment and Sustainment projects also show significant improvements in certification planning. Certification provides assurance that a product, service or organisation complies with a stated specification standard or other requirements.[39] The ADF’s philosophy is that the organisations responsible for delivering supplies or services will certify that the materiel for which they are responsible complies with specified standards and is technically fit for service in the intended role. However, for most of the projects in the ANAO’s audit sample, Certification Plans were not authorised until some years after the project’s approval by government and the signing of prime contracts.[40]

42. Changes brought about by the 2008 Defence Procurement and Sustainment Review include the progressive redrafting of the Materiel Acquisition Agreements between CDG and DMO to include the Capability Managers and their recently defined role of capability development coordination and reporting.[41] The new Materiel Acquisition Agreement provisions more clearly set out responsibility for defining requirements and agreeing procedures for determining compliance with the requirements.

43. There is little doubt that, besides needing effective management structures, Navy capability development requires standardised management processes that enable the smooth handoff of systems engineering work across organisational boundaries. CDG and DMO have achieved progress in this area. However, improving the handoff of work between DMO and Navy is a more challenging task, as it requires sound systems engineering to detect risks and issues that may develop and compound during each project’s system definition and acquisition phases. Risks and issues need to be recognised and reduced to manageable levels more effectively than has been demonstrated to date in many projects.

44. The ANAO has recommended (Recommendation 1) that to achieve the ‘seamless management’ of whole-of-life capability envisaged in 1998, CDG, DMO and Capability Manager organisations further rationalise and streamline all key capability definition, acquisition and materiel support processes, and ensure that these processes are integrated, practical and focused on the efficient and reliable delivery of ADF capability. The ANAO considers that this task would generally not involve developing new processes, but rather ensuring more efficient, effective and streamlined use of existing processes, and the removal of processes that have proven to be not cost effective. In progressing this work, Defence could leverage off DMO’s engineering policies, procedures and guidance standardisation program, to achieve important elements of its seamless management concept.

Chapter 4 – Requirements management and regulatory compliance

45. DMO project offices are required to monitor and report the cost and schedule performance of the projects they are responsible for, and to verify and validate that materiel delivered by contractors complies with the function and performance requirements specified in the acquisition contracts. It may be extremely costly to fix requirements or design defects found late in a project’s design and test phase. This underscores the critical importance of systems engineering processes that incorporate system definition and design reviews, and progressive verification and validation of a system’s compliance with specified requirements. The intent should be to detect and correct requirements and design defects as early as possible, while there are still sufficient resources within the project’s budget to correct any defects and to limit any impact on schedule.

46. It would be desirable for Defence to reinstate the mandatory application of a Technical Risk Identification and Mitigation System, so that risks associated with each project’s engineering management can be identified and mitigated in a timely way. It would also be desirable for DMO to further develop its progress measurement techniques and its Improved Project Scheduling and Status Reporting (IPSSR) program to better monitor and report project status.

47. Of the 20 projects considered during the course of this audit, the ANAO found only nine had current statistics to evidence that the verification and validation acceptance process was in operation. Defence regulations require that data applied to, and derived from, technical activities (including verification and validation statistics) must be authoritative, accurate, appropriate and complete.[42] To that end, Defence’s strategic materiel contracting template has, since 2002, mandated the use of the DOORS® requirements management system for Defence’s strategically important complex projects. However, the ANAO found some projects were using ad-hoc requirements management systems based on spreadsheets and databases developed by project personnel.[43] The projects using the mandated DOORS® system were in need of more personnel trained and experienced in its use.

48. The ANAO has recommended (Recommendation 2) that DMO takes steps to ensure that project offices use only approved requirements management systems and that its personnel are adequately trained in their use. Improvements in requirements management would benefit DMO in its contract management role, and would also assist Navy’s technical and safety regulators to gain sufficient, appropriate evidence to assess and manage the residual risk that the Chief of Navy accepts when releasing new or upgraded capability into service.

49. The ANAO also observed that DMO and Navy would benefit from working more closely during acceptance test and evaluation. A close working relationship is specified in DMO’s System Acceptance criteria, but in practice this does not always eventuate. For example, in December 2009, DMO completed contractual acceptance of all four upgraded RAN FFG Guided Missile Frigates with limited engagement of Navy in the verification and validation process leading to contractual acceptance. To date there are significant elements of the upgraded FFG Combat System that are yet to demonstrate the performance, reliability, availability and maintainability expected by Navy, but recourse to contractual remedies is now significantly reduced.

50. The Lightweight Torpedo Replacement project is in a similar situation. DMO provided the contractors with Supplies Acceptance Certificates for torpedos delivered by November 2010, albeit in the absence of completed verification and validation of the torpedos’ performance against their specifications. Also absent were a Navy approved Test and Evaluation Master Plan, and a regulatory Certification Plan endorsed and authorised by Navy.[44]

51. In the light of these findings, a more integrated approach to test and evaluation would:

-

enable Navy’s operational test and evaluation personnel to assist DMO to identify the early emergence of issues that may adversely impact on operational release of new or upgraded capability;

-

avert the repetition of operational tests that could more efficiently and effectively be conducted as part of verification and validation acceptance testing; and

-

avoid contractual difficulties resulting from supplies acceptance by DMO prior to Navy completing technical and safety regulatory reviews.

52. The ANAO has recommended (Recommendation 3) that Navy and DMO take steps to streamline and integrate verification and validation and acceptance testing, and overall regulatory review processes.

53. The strategy adopted by DMO increasingly over the last decade is to no longer implement the earned value progress payment strategy recommended by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts in 1986.[45] Rather DMO provides progress measurements and payments based on a mix of engineering and production metrics, software metrics, cardinal milestones, and a suite of project performance metrics based on Earned Value Management-like principles. However, there remains a risk that contractors may focus more on delivering equipment and less on maintaining a holistic perspective on contractual progress management, which includes other deliveries such as logistics items relating to equipment reliability and maintainability, and configuration management.[46] The result is the loss of a comprehensive progress measurement and payment incentive system, based on work package milestones and other objective measures of achievement, which is an important feature of an earned value system. It may also result in greater costs during the in-service phase, when logistics shortfalls and other deficiencies need to be addressed.

54. The ANAO observed that about a third of the DMO projects considered in this audit achieved Initial Operational Release and Operational Release without having complete configuration audit records relating to both system functional and system physical characteristics. DMO project teams are responsible for maintaining accurate configuration records in order to ensure that the risks to technical integrity and safety are adequately identified and managed. Reviews of Configuration Management in DMO and Navy conducted in 1999 and 2010, revealed significant non-compliance with adequate levels of configuration management. This is a significant systems engineering and technical regulation issue and the ANAO has recommended (Recommendation 4) that DMO improves the configuration management of naval materiel, and that Navy rejects materiel that is offered for acceptance into service without sufficient Configuration Management.

55. When Defence contracts involve system design and development, the implementation of effective project management and systems engineering processes are central to achieving improved outcomes. On the other hand, when capability acquisitions involve military off-the-shelf (MOTS) or commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) equipment that needs no further development or integration into other systems, Defence may choose to rely on the vendor’s systems engineering processes. However, even though technical risks are seen to decrease as projects move from developmental systems toward off-the-shelf solutions, in practice this has not entirely been the case.[47] The acquisition of off-the-shelf equipment still needs to be accompanied by sufficient and appropriate test and evaluation data suitable for the Services to assess the equipment’s fitness for service, and its risk to personnel, public safety, and the environment. In all cases, it is fundamental that senior responsible officials managing the definition, acquisition and acceptance phases have clear visibility of the key decisions, assumptions and test and evaluation data that led the vendor to offer the equipment as off-the-shelf.

56. The ANAO has recommended (Recommendation 5) that Defence strengthen the critical System Acceptance process by requiring Navy capability Project Certification Plans to designate a responsible officer for System Acceptance, who has seniority commensurate with the importance of the project, and who is external to the Systems Program Office.

Chapter 5 - Navy Materiel Certification

57. When Navy Mission Systems reach a point near System Acceptance from contractors, DMO and Navy engage in certifying that these systems are sufficiently safe for Navy to commence operational test and evaluation at sea. The release of new Navy capability into operations is likely to present Navy with new risks to operational capability and reliability, personnel safety and environmental protection. Accordingly, the Chief of Navy requires assurance that, when new or upgraded systems are offered for Initial Operational Release or Operational Release into Navy service, the systems’ mission and support risks are identified, assessed, eliminated or controlled, and subsequently accepted by Navy at an appropriate level.[48] The intention is that this assurance is provided by the Navy Regulatory System, which sets out the requirement for DMO to develop Safety Cases and Reports on Materiel and Performance State (known as TI 338s).[49]

58. The ANAO found that the TI 338s for all 13 Navy projects considered in the course of this audit that had received Initial Operational Release, and Operational Release had been reviewed and endorsed by the regulators prior to the respective Initial Operational Release and Operational Release authorisation by the Chief of Navy. All but one of these projects also had approved Safety Cases. The safety of the remaining project had been assured by safety assessments provided by the Classification Society and other firms engaged by DMO.

59. Leading up to this stage, the ANAO’s analysis showed that projects that delivered the specified capability and adhered best to approved management processes and record-keeping were less likely to experience delays in achieving Initial Operational Release and Operational Release. Those qualities point to sound processes within DMO, and provide Navy’s technical and safety regulators and its test and evaluation personnel with better information on which to gauge how the risks to safety and fitness for service are being managed.

60. ANAO examined evidence of the timeliness and quality of documents provided by DMO for Navy regulatory review. In some instances, there were issues with the adequacy and completeness of the information provided by DMO in support of Safety Cases and TI 338s. In other cases, DMO provided the information but at very late notice, in one instance leaving very little time for Navy to assess the safety of live missile firings. The ANAO has recommended (Recommendation 6) that Navy adopts streamlined regulatory review processes through improved verification cross referencing and that DMO mandates the adherence to the Navy’s regulatory review schedule requirements.

61. Over the last decade, Defence has become increasingly reliant on shipping industry Classification Societies to provide independent verification that each naval vessel complies with design, construction and operation requirements that govern the vessel’s particular class.

62. Since 2005, Navy has been formulating a Navy Flag Authority arrangement that will, for RAN vessels, establish contractual and formal relationships with the Classification Societies that, with respect to Navy vessels, will facilitate improved requirements-setting and design and construction rule interpretations.

63. As at February 2011, the respective Defence Instructions for the Navy Flag Authority arrangement and the Certification Society engagement arrangements remained under development. The ANAO has recommended (Recommendation 7) that Navy and the DMO seek an early agreement on the arrangements for the Navy Flag Authority arrangements.

Chapter 6 - Navy Operational Release

64. Operational release milestones are a measure of the development and integration of all eight Fundamental Inputs to Capability and the degree of maturity of a new or upgraded capability. Navy accepts that Final Operational Capability may not be available at System Acceptance by the DMO.[50] It may take some time for all Fundamental Inputs to Capability to be fully realised, and the two steps of Initial Operational Release and Operational Release reflect Navy’s progressive acceptance of capability, typically through a series of operational tests and evaluations.

65. Both DMO’s System Acceptance process and the progressive realisation of the Fundamental Inputs to Capability, raise the need for acquisition contract provisions that allow operational test and evaluation involvement by Navy, and for DMO’s test and evaluation schedule and resources to have the flexibility to facilitate Navy’s involvement in system validation leading to System Acceptance. This flexibility also requires DMO to remain engaged following Initial Operational Release and during operational test and evaluation conducted by Navy, to provide resources and to remediate capability deficiencies identified against the approved project requirements.

66. The recent experience of the SEA 1448 Anzac Class Anti-Ship Missile Defence project indicates that this approach is feasible: the integration of system verification and system validation through operational test and evaluation led to successful results for Navy, DMO and its contractors.

67. An integrated and consistent approach would also provide greater assurance to key decision-makers. To date, the overall scope and content of Initial Operational Release Submissions and Operational Release Submissions to the Chief of Navy have varied considerably. At the time of the audit, RANTEAA was seeking to reduce this variability by implementing a more consistent and systematic approach to developing Initial Operational Release and Operational Release Reports and Operational Capability Statements. RANTEAA has now implemented a standard format for these reports, which is now managed under RANTEAA’s accredited Quality Management System.

68. Once systems are delivered by DMO to Navy, they are included in the Materiel Condition Assessments carried out by ships crews. These assessments occur during the force preparation phase of a ship’s activity program, and as a minimum, they are to be conducted within 12 months of delivery.[51] Materiel Condition Assessments would provide important information on Navy equipment reliability, availability and maintainability as demonstrated in its operating environment. However, their timely completion is presently hampered by deficiencies in configuration management conducted by DMO, and deficiencies in the state of the various Configuration Management Information Systems used by DMO and Navy, as reported by various internal reviews.[52]

69. The Materiel Condition Assessments include Combat System Qualification Trials, which validate that an individual ship’s combat system has been installed correctly (including software upgrades) and can be operated and maintained in a safe and effective manner. These trials were once conducted by the former Fleet In Service Trials (FIST) section of the former Maritime Command Australia, but are now conducted by each ship’s officers and crew. This practice may not be ideal, as the ship may not have available suitably skilled and resourced trials personnel and facilities, or may be subject to scheduling pressures due to other commitments. For preparedness and cost reasons, in-service guided weapon live firings are generally restricted to systems qualification and testing activities. Wherever possible, these firings are also optimised for operator proficiency training and tactical development. Navy advised the ANAO that it has reviewed the allowances for guided weapon live firings and has developed a pragmatic firing policy that balances the cost of conducting live firings against the need for system testing and operator training.

Chapter 7 - Capability Management in Navy Headquarters

70. Since 1984, Navy has undergone a range of significant organisational changes mainly brought about by the establishment of the Capital Procurement Organisation in 1984, the commencement of the Defence Commercial Support Program in 1991,[53] and the Defence Reform Program in 1998. These changes included the transfer of all Navy design, construction, and deep-level maintenance to the private sector,[54] and the transfer of the functional responsibility for Navy’s materiel requirements definition, materiel acquisition and logistics support functions to other Defence Groups, principally to CDG and DMO.

71. The changes have had a significant impact on Defence’s ability to attract and retain qualified engineering staff. Currently, Navy has filled only two-thirds of its own engineering positions, 72 per cent of the Navy engineer positions in DMO, and only about one-third of the Navy engineer positions in CDG. This limits the availability of Navy engineers to perform the vitally important role of bringing their knowledge of the operating environment into the capability definition and acquisition stages of the capability life-cycle.

72. The effects of ongoing skills shortages are evident in the application of the Navy Technical Regulatory System, which is dependent on qualified and experienced engineering staff. The 2006 and 2009 internal reviews of Navy’s Regulatory system found that the integrity of the Navy Technical Regulatory System was vulnerable to staffing deficiencies, that this presented a significant risk to regulatory framework assurance, and had led to significant deficiencies in the implementation of Navy’s Technical Regulations.[55] While obviously a challenge, this needs to be reviewed as a priority.

73. The findings of these internal reviews are corroborated by the significant variations in the quality and completeness of the evidence supporting critical stages of the systems engineering cycle set out in Chapter 4 of this report. This is especially so with respect to information concerning system verification and validation, configuration management, and System Acceptance.

74. The Acceptance into Service process has been adversely affected by mis-matched expectations between DMO and Navy with regard to requirements verification and validation prior to System Acceptance by DMO.[56] Under these circumstances, it is likely that risks and issues propagating through the system definition, verification and validation and configuration management processes may not be adequately addressed, resulting in some materiel delivered to Navy not being fully fit for service. Clear up-front agreement, including contractual agreements, on requirements and their verification and validation procedures, may minimise the likelihood of disagreement about requirements and the adequacy of verification and validation, thus ensuring that the focus remains on delivering government agreed capability.

Summary of agency response

Defence welcomes the ANAO audit report on Acceptance into Service of Navy Capability and notes that the recommendations provide opportunities to build upon the progress made by Defence in recent years in delivering improved acquisition outcomes. This report demonstrates the complexity of the acquisition and subsequent transition into service of naval platforms, and emphasises the close collaboration that must exist between the Capability Manager, the Defence Materiel Organisation and Capability Development Group, for success. The Government's Force 2030 white paper has a significant maritime component and this audit report is timely, noting the planned introduction of a number of major capabilities in the near future. Defence accepts the eight recommendations of the ANAO report.

Since early 2000, Defence has implemented a suite of acquisition and systems engineering initiatives. These improvements, together with those introduced following the Defence Procurement (Kinnaird) Review 2003 and the Mortimer Review (2008), have further strengthened the acquisition practices of Defence. These improvements address many of the risks that the Australian National Audit Office has highlighted. The audit notes that the current processes to deliver naval capability into service are based upon best practice system engineering processes. The five 'post 2003' naval capability projects detailed by the audit team have been recognised as positive examples of better requirements management and the effective planning of test and acceptance regimes against the approved capability envelope.

Defence acknowledges that there is scope to achieve better capability outcomes through further process alignment, and some of these improvements can be made in the near term. However, the challenge for Defence will continue to be our ability to recruit, develop and retain suitably experienced people to manage the acquisition and transition into service of new capability.

Footnotes

[1] Department of Defence, Defending Australia in the Asia Pacific Century: Force 2030, Defence White Paper 2009, May 2009, pp.13, 53, 60, 63-64, 67, 70-73.

[2] CDG is one of the Groups within the Department of Defence. The Defence portfolio consists of a number of component organisations that together are responsible for supporting the defence of Australia and its national interests. The three most significant bodies are:

- the Department of Defence — a department of state headed by the Secretary of the Department of Defence;

- the ADF — which consists of the three Services (including Reserves) commanded by the Chief of the Defence Force (CDF);

- the Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO) — a prescribed agency within Defence, headed by its Chief Executive Officer (CEO) DMO.

In practice, these bodies work together and are broadly regarded as one organisation known as Defence (or the Australian Defence Organisation).

[3] Readiness is the ability to prepare a capability for operations within a designated time. Sustainability is the ability to maintain a capability on operations for a specified period.

[4] Deep-level maintenance includes scheduled maintenance, unscheduled maintenance and repairs, which require extensive Repairable Item dismantling in specialised jigs, and the use of specialised support equipment, technical skills or industrialised facilities.

[5] Over the last 10-15 years, Defence has become increasingly reliant on shipping industry Classification Societies to provide independent verification that each naval vessel complies with design, construction and operation requirements relevant to the vessel’s particular class. This aligns with commercial shipbuilding practice whereby, for finance and insurance purposes, shipbuilders contract Classification Societies to independently verify, and then certify, that ship designs and construction comply with engineering standards, international conventions, rules and regulations. See http://www.iacs.org.uk/document/public/explained/Class_WhatWhy&How.PDF

[6] ANAO Audit Report No.13, 1999–2000, Management of Major Equipment Acquisition Projects, Department of Defence, October 1999, pp.18, 19, 44, 58-65. When the Defence Executive was formed in 1998 it was to be Defence's highest decision-making body and was comprised of all ten of the Organisation's senior managers along with COMSPTAS [Commander Support Australia]. Two external members were to be invited to join the Executive to provide a wider perspective. It established a Capability Management Improvement Team to explore options and make recommendations for improving Defence’s capability management. Defence Executive: A Message to all Defence Personnel from the Executive (internal memorandum), Canberra 6 July 1998. Department of Defence, DEFGRAM NO 187/98, Formation of Capability Management Improvement Team, 6 August 1998, Annex A: Capability Management Improvement Terms of Reference.

[7] Defence Executive: A Message to all Defence Personnel from the Executive (internal memorandum), Canberra 6 July 1998.

[8] Department of Defence, Defence Procurement Review 2003, August 2003, pp.vii, viii, 16, 17, 39, 40, 41.

[9] In 2003, DMO recognised the need to establish a project management certification framework that identified mandated levels of education, training and experience in project management for the management of projects with different levels of complexity. This framework was to contain the various levels of software and systems engineering education, training and experience that were applicable to people managing complex safety and mission critical software intensive projects. Keynote address by the Head Electronic Systems Division, Defence Materiel Organisation, to the Systems Engineering, Test and Evaluation Conference 2003, DMO Reform - Implementing a Systems Philosophy in the Defence Materiel Organisation, 29 October 2003 Canberra, p.12. In 2010, DMO reported that its workforce development program continued to expand the range of development activities, especially competency based skilling and a strong professionalisation program aligned to DMO’s business needs. Department of Defence, Defence Annual Report 2009-10, Vol. 1, p.149.

[10] Blanchard, Bengamin. S., System Engineering Management, John Wiley & Sons, Second Edition, 1998, pp.1, 10-12, 35–48.

[11] ibid., pp. 25–26.

[12] Price basis is at the year in which the project was approved by government and does not include price indexation, scope changes, or any exchange rate variations since approval of the project. Source: Department of Defence, June 2010. Rounded to the nearest $million.

[13] DMO Project budgets against which cost performance is measured are subject to variations arising from price indexation (inflationary) effects, exchange rate variations, changes in scope, transfers to Defence Groups and DMO cost performance. Source: Defence Materiel Organisation, January 2011. Rounded to the nearest $million.

[14] The Army AIR 87 ARH and AIR 9000 MRH helicopter projects were included in the audit as their specifications include operations from Navy platforms.

[15] This DMO Major Projects Report was published in ANAO Report No.17, 2010–11, 2009–10 Major Projects Report Defence Materiel Organisation, November 2010, pp.67–128, 135–406.

[16] The Initial Operational Release milestone marks the point in time at which the control and responsibility of new or upgraded Mission and Support Systems transfers from the DMO to Navy, and the Chief of Navy, in his Capability Manager role, accepts all Mission and Support System technical and operational risks from the DMO.

[17] The Operational Release milestone marks the point in time at which the Capability Manager is satisfied that a Capability System, or subset, has proven effective and suitable for the intended role and, that in all respects, it is ready for operational service.

[18] On 6 April 2011 the Minister for Defence and the Minister of Defence Materiel confirmed that Australia had been successful in its bid to acquire a Bay Class ship, Largs Bay, for £65 million (approximately $100 million). Largs Bay is a Landing Ship Dock (LSD) which was commissioned into service in 2006. It became surplus to UK requirements as a result of the UK Government’s 2010 Defence Strategic Review. Minister for Defence, MIN80/11, Largs Bay acquisition, 6 April 2011, p.1.

[19] Final Operational Capability is the point in time at which the final subset of a Capability System that can be operationally employed is realised. Final Operational Capability is a capability state endorsed at project approval at Second Pass, and reported as having been reached by the Capability Manager. Defence Instructions (General) OPS 45-2, Capability Acceptance into Operational Service, February 2008, p.A1.

[20] At the time of the audit, DMO was not able to provide the relevant government approval for the projects in the audit sample. In May 2011, Defence advised the ANAO that:

In early 2011, the DMO started a Project Baseline Review (otherwise known as a project 'due diligence') to ensure alignment between current project objectives and each corresponding Government project approval. Noting the extended duration of many major capital acquisition projects, the DMO is conducting this review to ensure the current key project elements of scope, budget and schedule match each related Government project approval (tracing from the original approval through to any subsequent Government-authorised changes). This work requires reference to Cabinet and other Government documents from across each project's life; as the majority of these documents are not held in the DMO (or Defence), external liaison is required to establish an authoritative record. Once this research is completed, the DMO will then assess the degree of alignment between the current project objectives and Government approval. Any significant deviation is then expected to be addressed with Government. The DMO plans to finalise this work by December 2011. Defence advice to the ANAO 29 May 2011.

[21] Department of Defence, The Response to the Report of the Defence Procurement and Sustainment Review The Mortimer Review, May 2009, pp.9, 26. At the time of the audit, all but one of the projects considered by the ANAO during the course of this audit continued to have Materiel Acquisition Agreements in place that were solely between CDG and DMO, thus excluding the Capability Manager.

[22] Operational Concept Documents (OCDs) are intended to inform system acquirers and developers of the ADF’s operational requirements. Without specifying particular solutions, OCDs: describe the characteristics of the required capability from an operational perspective; facilitate an understanding of the overall system goals from both the Mission System and Support System perspectives; detail missions and scenarios associated with operations and support from both the Mission System and Support System perspectives; provide a reference for determining ‘fitness for service’; and provide a justifiable basis for the formal requirements for both the Mission System and Support System.

Function and Performance Specifications (FPSs) define what the ADF requires. They specify the system’s functional requirements from the perspective of the needs of final users; specify, in quantifiable terms, the system’s critical performance requirements that are the basis for design acceptance and qualification testing of the system; and provide the basis for the contracted Mission System and Support Systems’ design specifications.

Test Concept Document (TCD) outlines the test approach and strategy to be used to verify and validate that the design and operational requirements of the new or upgraded capability have been met. It defines the ADF’s intended test and evaluation approach and strategy for accepting the system, agreed between the DMO and Defence; it forms the basis for the project’s Test and Evaluation Master Plan and identifies the funding and resources required for the project’s test and evaluation program that culminates with System Acceptance and Operational Release; it defines the Critical Operational Issues (identified in the Operational Concept Document) that are to be tested and evaluated to assess the system’s ability to perform its mission; it defines the Critical Technical Parameters derived from the critical requirements identified in the Function and Performance Specification; and finally it defines the agreed operational scenarios that need to be successfully trialled in order for the delivered capability to receive Operational Release.

[23] Defence Instructions (General) LOG 4-5-012, Regulation of technical integrity of Australian Defence Force materiel, September 2010, p.2 and Definition of Terms.

[24] SEA 1390 Phase 4B, SEA 1448 Phase 2A, SEA 4000 Phase 3, JP 2048 Phase 4A/B and AIR 9000 Phase 2.

[25] The need for Capability Managers to sign the Materiel Acquisition Agreements was established in May 2009. See Recommendation 3.1 of Department of Defence, The Response to the Report of the Defence Procurement and Sustainment Review The Mortimer Review, May 2009, p.26.

[26] Defence advised that the planned completion date for the revised tripartite Materiel Acquisition Agreements that include the Navy Capability Manager introduction is December 2011.

[27] In December 2008, the US Department of Defense issued revised defense system acquisition instructions concerning collaboration between developmental and operational testers to build a robust integrated test program, and to increase the amount of operationally relevant data that can be used by both communities. Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics, Report of the Defense Science Board Task Force on Developmental Test & Evaluation, May 2008, p.8. Department of Defense Instruction 5000.002, Operation of the Defense Acquisition System, December 2008, Enclosure 6, Integrated T&E.

[28] The Chief of Navy is responsible for exercising oversight and coordination of all elements necessary to introduce the full level of operational capability into service within scope, cost, workforce, schedule and risk parameters agreed to by government. Department of Defence, Joint Directive by Chief of the Defence Force and Secretary, Department of Defence for Project XXX Phase NN, Post Second Pass Implementation Stage, Draft declassified template, March 2011.

[29] This includes DMO for Mission System and Support Systems, Defence Support Group for Defence Facilities, and the Chief Information Officer Group for information and communications technology.

[30] Department of Defence, The Defence Accountability Framework, Review of accountability and governance in the Department of Defence, January 2011.

For newly approved projects from February 2011, Project Directives will hold the Chief of Navy responsible for exercising oversight and coordination of all the elements necessary to introduce the full level of operational capability into service within scope, cost, workforce, schedule and risk parameters agreed to by government. This includes applying a regulatory system to assure that Navy capability is fit for service and only poses acceptable risks to personnel, public safety, and the environment. Department of Defence, Joint Directive by Chief of the Defence Force and Secretary, Department of Defence for Project XXX Phase NN, Post Second Pass Implementation Stage, Draft declassified template, March 2011. Department of Defence, Defence Capability Development Handbook (Interim), April 2010, paragraph 4.58. Defence Instructions (General) OPS 45-2, Capability Acceptance into Operational Service, February 2008. Defence Instructions (General) Log 4-5-012, Regulation of technical integrity of Australian Defence Force materiel, September 2010.

[31] Department of Defence, Defence Procurement Review 2003, August 2003, pp.iv, v, 11.

[32] ibid., pp.iv, 33-37.

[33] In May 2008, the Government commissioned the Defence Procurement and Sustainment Review. The Review report provided to the Government in September 2008 made 46 recommendations aimed at addressing the five principal areas of concern identified by the Review: inadequate project management resources in the Capability Development Group; the inefficiency of the process leading to Government approvals for new projects; shortages in DMO personnel; delays due to inadequate industry capacity; and difficulties in the introduction of equipment into full service.

[34] The matrix management model reflects organisational arrangements where the traditional hierarchical functional group structures, that have vertical authority and accountability for function (process) execution and skills development, are supplemented by project management structures that have horizontal authority and accountability for product development coordination and delivery, across multiple functional groups.

[35] Department of Defence, The Defence Accountability Framework, Review of accountability and governance in the Department of Defence, January 2011.

[36] The Project Directives will hold the Capability Managers responsible for exercising oversight and coordination of all elements necessary to introduce the full level of operational capability into service within scope, cost, workforce, schedule and risk parameters agreed to by government. Department of Defence, Joint Directive by Chief of the Defence Force and Secretary, Department of Defence for Project XXX Phase NN, Post Second Pass Implementation Stage, Draft declassified template, March 2011. Department of Defence, Defence Capability Development Handbook (Interim), April 2010, paragraph 4.58.

[37] This situation presented particular difficulties for DMO Project Directors. ANAO Audit Report No.11, 2007-08, Management of the FFG Capability Upgrade, Department of Defence, Defence Materiel Organisation, October 2007, pp.14, 15, 66-67. Fixed-price contracts are generally considered to be the lowest risk to the government, because the onus is on the contractor to provide the deliverable at the time, place, and price specified in the contract. In addition, the contractor is responsible for bearing any costs associated with a delay or inadequate performance, assuming that the government has not contributed to contractor performance issues through issues such as late delivery of government-furnished equipment or changed requirements.

[38] DMO recognised the need to develop a DMO Systems Engineering Manual in 2002, when it commenced a Systems Engineering Improvement Program. Department of Defence, Defence Materiel Organisation, Systems Engineering Improvement Program (SEIP) Phase One Overview Improving Capability Through the Application of Systems Engineering, Edition 1, September 2003, p.3

[39] Department of Defence, Defence Instructions (General) LOG 08-15, Regulation of technical integrity of Australian Defence Force materiel, June 2004, Definition of Terms. Defence Instructions (General) LOG 4-5-012, Regulation of technical integrity of Australian Defence Force materiel, September 2010, p.2 and Definition of Terms.

[40] SEA 1102 Ph 3A, SEA 1348, SEA 1390 Ph 2.1, SEA 1390 Ph 4B, SEA 1401 Ph 2 – Survey Motor Boats, SEA 1429 Ph 2, SEA 1439 Ph 4A, SEA 1654 Ph 2A, JP 2008 Ph 3E, and JP 2043 Ph 3A.

[41] Department of Defence, The Response to the Report of the Defence Procurement and Sustainment Review The Mortimer Review, May 2009, pp.9, 26, 27.

[42] Such data must always be accessible, but need not be retained in-house. Department of Defence, Defence Instructions (General) LOG 08-15, Regulation of technical integrity of Australian Defence Force materiel, June 2004, p.4. Defence Instructions (General) LOG 4-5-012, Regulation of technical integrity of Australian Defence Force materiel, September 2010, p.3.

[43] This practice is not encouraged by DMO’s senior management, since it does not enforce the rigour necessary for requirements management, nor do they make it easy to establish and maintain traceability between the requirements specified in the function and performance specification, and their derived requirements allocated to systems specifications and Support Systems specifications. Defence Materiel Organisation, Defence Materiel Verification and Validation Manual, November 2008. p.27.

[44] Defence advised the ANAO in June 2011 that: ‘the [JP 2070 acquisition] contract provides robust protection to the Commonwealth should the torpedoes subsequently prove to be deficient against the specifications.’ Defence advice to the ANAO DMO Additional Information and Proposed Amendments – Revised S.19 Summary, 8 June 2011.

[45] Joint Committee of Public Accounts, Report 243, Review of Defence Project Management, Vol. 1 Report, 1986, pp.73-76, 115,116. Department of Defence, Defence Annual Report 1989-90, pp.51, 52.

[46] A key lesson learned by DMO on the SEA 1390 Ph 2.1 FFG Upgrade project, was that milestones which enable use of the equipment and supplies (such as integrated logistics support and training) should be given similar weight as delivery of the equipment itself. ANAO Report No.17, 2010-11, 2009-10 Major Projects Report Defence Materiel Organisation, November 2010, pp.263, 264.

[47] ANAO Audit Report No.37, 2009-10, Lightweight Torpedo Replacement Project, Department of Defence, May 2010, pp.18, 19, 65-67, 189. ANAO Audit Report No.11, 2007-08, Management of the FFG Capability Upgrade, Department of Defence, Defence Materiel Organisation, October 2007, p.17. ANAO Audit Report No.36 2005-2006, Management of the Tiger Armed Reconnaissance Helicopter Project – Air 87, Department of Defence, Defence Materiel Organisation, May 2006, pp.11, 18, 38. ANAO Report No.13, 2009-10, 2008-09 Major Projects Report Defence Materiel Organisation, November 2009, pp.177-178, 212, 218.

[48] Department of Defence, Defence Instructions (Navy) ADMIN 37-15, Assuring the safety, fitness for service and environmental compliance of naval capability, April 2007, p.3.

[49] Safety Cases are developed by DMO System Program Offices and describe how safety has been considered with regard to the workplace, Mission and Support System hardware and software, personnel and management systems. They are to formally demonstrate that due diligence has been given to the occupational health and safety implications of the introduction into service of new capability, and they facilitate the management of hazards throughout the life of the capability through to disposal. Royal Australian Navy, ABR 6303, Navy Safety Systems Manual, Edition 4, 2011, Annex F to Chapter 5.

The TI 338 reports are developed by DMO System Program Offices and provide key risk information to Navy’s Commanding Officers and Force Commanders. They provide an account of the materiel state of the Mission and Support Systems, in terms of operational limitations within the parameters approved by government at Second Pass, and hazard risk assessments of the remaining risks at the time of materiel release by DMO to Navy. Royal Australian Navy, ABR 6205, Naval Operational Test and Evaluation Manual (NOTEMAN), Edition 4, 2011, Annex A to Chapter 5.

[50] Ideally, Initial Operational Release would occur soon after Mission and Support Systems have undergone System Acceptance by the DMO. Department of Defence, Defence Instructions (General) OPS 45-2, Capability Acceptance into Operational Service, February 2008, p.A-2

[51] At the time of the audit, the Defence Instructions (General) Ops 45-2, Capability acceptance into operational service, February 2008, was being revised to include an Initial Materiel Release milestone, at which time materiel is delivered by DMO to the Chief of Navy for acceptance.

[52] Defence Materiel Organisation, Maritime Systems Division, Configuration Management Improvement (CMI) Project Summary Report, September 2010, Executive Summary. Review of Configuration Management in the RAN, August 1999.

[53] ANAO Audit Report No.2, 1998-99, Commercial Support Program, July 1998.

[54] Deep-level maintenance includes scheduled maintenance, unscheduled maintenance and repairs (which require extensive Repairable Item dismantling in specialised jigs) and the use of specialised support equipment, technical skills or industrialised facilities.

[55] Royal Australian Navy, Report on the Strategic Review of Naval Engineering, November 2009.

[56] System Acceptance by DMO normally involves the issue of a Supplies Acceptance Certificate (Form SG1), which provides for an authorised representative of the supplier to certify that the supplies conform in all respects to the conditions and requirements of the contract. Provision is also made for the supplier to record details of any non-compliance with the terms and conditions of the contract. Any non-compliance with contractual requirements must be approved by, or on behalf of, the Commonwealth Representative prior to acceptance.