Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Participation Targets in Major Procurements

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- The mandatory minimum requirements (MMRs) are the Australian Government’s principal mechanism for applying Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participation targets in major procurements.

- The audit was undertaken to provide assurance the MMRs are being administered effectively and entities are complying.

Key facts

- The MMRs apply to non-corporate Commonwealth entity procurements valued over $7.5 m in eight services industry sectors (expanding to 19 from July 2020).

- Entities must ensure contractors commit to participation targets of at least 4% for the project or 3% for the organisation.

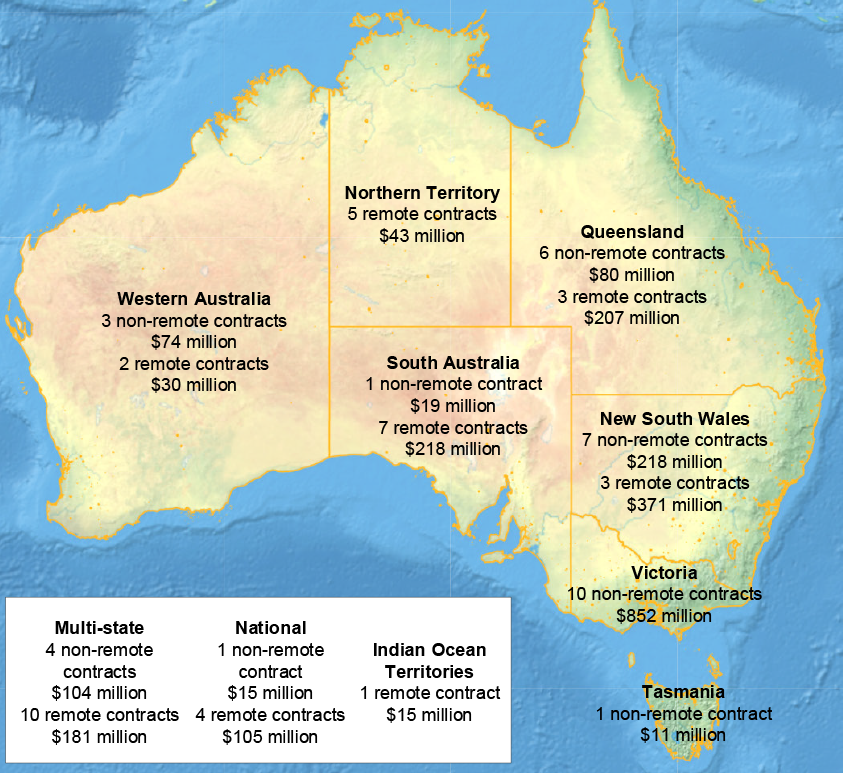

- The ANAO examined a sample of 69 active MMR contracts from six selected entities to test compliance with the MMRs. 35 contracts had a component delivered in a remote area.

What did we find?

- The effectiveness of the MMRs has been undermined by ineffective implementation and insufficient compliance.

- While the design of the MMRs supports the Government’s policy settings, the MMRs have been ineffectively implemented and monitored by the policy owner.

- Selected entities’ compliance with the MMRs fell short of standards. Most contracts assessed failed to comply with required steps.

What did we recommend?

- The Auditor-General made three recommendations to the National Indigenous Australians Agency aimed at improving the implementation and monitoring of the MMRs.

- The Auditor-General also made three recommendations to all audited entities aimed at increasing compliance levels.

- Audited entities agreed to the recommendations.

30%

Estimated proportion of the value of procurement by non-corporate Commonwealth entities covered by the MMRs from July 2020.

52%

Percentage of tested contracts that created a contractual requirement to meet MMR targets.

4.3%

Percentage of tested contracts that were actively reporting in the monitoring system as at 30 June 2019.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Over the past three decades the Australian Government has sought to use its position as a major procurer of goods and services in the Australian economy to generate economic opportunities for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

2. In May 2015 the government introduced the Indigenous Procurement Policy (IPP), which includes a requirement for Australian Government entities to apply mandatory minimum requirements (MMRs) for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participation to high value contracts in certain industry categories. Responsibility for the IPP transferred from the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) to the newly created National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA) on 1 July 2019 through a machinery-of-government change.

3. In 2017 the Senate Finance and Public Administration References Committee (the committee) held an inquiry into the Community Development Program. The committee recommended that the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) conduct an audit of Australian Government contracts that relate to service delivery in remote locations with a specific focus on the use of, and compliance with, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander employment targets.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

4. The MMRs are the Australian Government’s principal mechanism for applying Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participation targets in major procurements. As the MMRs have been in operation since July 2015, and binding on contractors since July 2016, their administration by the policy owner (PM&C until June 2019 and NIAA since July 2019) and application by government entities should be relatively mature.

5. This audit was undertaken to provide assurance that the MMRs are being effectively administered and entities are complying with them. The audit includes a focus on the application of the MMRs in remote areas, to address the Senate Finance and Public Administration References Committee’s recommendation that the ANAO conduct an audit of Australian Government contracts relating to service delivery in remote locations. The audit timing also presents an opportunity for NIAA to address any identified areas for improvement prior to expanding the MMRs to cover eleven additional industry categories from 1 July 2020.

Audit objective and criteria

6. The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the administration of the MMRs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participation in major government procurements in achieving policy objectives.

7. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level audit criteria:

- Are the MMRs designed to achieve the government’s policy objectives?

- Are the MMRs being implemented and monitored effectively?

- Are entities complying with the MMRs in major procurements?

8. Six entities were selected for examination in the entity compliance component of the audit, based on the number and nature of MMR contracts they held: Department of Defence (Defence); Department of Education (Education); Department of Employment, Skills, Small and Family Business (Employment); Department of Home Affairs (Home Affairs); Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Cities and Regional Development (Infrastructure); and NIAA.1

Conclusion

9. While the MMRs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participation were effectively designed, their administration has been undermined by ineffective implementation and monitoring by the policy owner and insufficient compliance by entities.

10. The design of the MMRs supports the achievement of the government’s policy objectives. The MMR policy settings are reasonable and supported by evidence.

11. The MMRs have not been implemented and monitored effectively due to inadequate implementation planning and delays in establishing a centralised monitoring system. While the policy owner has publicised the MMRs, it has not provided entities and contractors sufficient guidance on complying with the MMRs. The current regime for enforcing compliance with MMR reporting requirements is not operating effectively and, as a result, the policy outcomes have not been evaluated.

12. Selected entities’ compliance with the MMRs fell short of the standard required for managing major procurements. In the procurement phase, while selected entities mostly recognised when the MMRs applied, they failed to comply with all required steps. In the contract management phase, entities have not established appropriate performance reporting arrangements. Where reporting has been occurring, entities have not gained appropriate assurance over reported performance.

Supporting findings

Policy design

13. The design of the MMRs aligns with the government’s policy objectives, which were to drive growth in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander businesses and employment.

14. The design of the MMRs was partially informed by stakeholder views and previous experience. The MMRs addressed concerns raised with the previous Indigenous Opportunities Policy, and PM&C consulted government entities with significant procurement activities. PM&C did not consult non-Indigenous businesses that would be affected by the MMRs and did not adequately consider previous experience with implementation challenges.

15. The industry coverage criteria and contract value threshold for the MMRs support the government’s policy objectives by achieving broad coverage while limiting compliance burden. Categories for exempting or excluding contracts from the MMRs are appropriate. Applying the policy to Commonwealth corporate entities and companies would broaden opportunities for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to gain skills and economic benefit from large government projects.

16. The criteria established under the MMRs for setting participation targets are appropriate. The minimum target requirements allow contractors flexibility to choose targets appropriate to their situation. The criteria for remote targets allow flexibility to set targets above the minimum requirements that are appropriate to the services being procured and the remote area in which they will be delivered.

Policy implementation and monitoring

17. PM&C did not develop an appropriate implementation plan for the MMRs in 2015. NIAA has developed an implementation plan for the 2020 expansion of the MMRs.

18. Current arrangements for communicating the MMRs are partially effective. PM&C and NIAA have promoted awareness of the MMRs to relevant stakeholders through their communication activities. However, they have provided ineffective guidance and advice to entities and contractors on how to comply with the MMRs throughout the contract lifecycle to ensure intended outcomes are achieved.

19. PM&C has established a central database, the IPP Reporting Solution, which has the potential to monitor compliance and report on implementation of the MMRs. However, the system has not delivered on this potential due to delays in its rollout and low levels of uptake by entities and contractors. As a result, information in the system for MMR contracts is incomplete and cannot be used to assess contractors’ previous MMR performance or report on implementation.

20. The most recent evaluation of the IPP was completed in 2019. It did not evaluate the MMRs or assess their contribution to closing the gap in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous economic outcomes due to the lack of monitoring data on MMR contracts.

Entity compliance in major procurements

21. Selected entities mostly provide appropriate guidance to staff on complying with the MMRs. Once NIAA has updated its guidance information on the MMRs, there is scope for central procurement teams within entities to provide greater support to officers managing MMR procurements to ensure they comply with requirements.

22. None of the selected entities fully complied with the MMRs during the procurement phase. Entities generally recognised the need to apply the MMRs to major procurements but did not comply with all required steps. Key compliance issues identified were: excluding contracts for invalid reasons; and not creating a contractual requirement to meet targets.

23. Entities agreed MMR participation targets that met or exceeded the minimum levels for most assessed contracts. For contracts that included a remote delivery component, entities did not comply with the requirement to ensure targets deliver significant participation outcomes.

24. Entities have not established appropriate performance reporting arrangements, as less than half of the contractors that are required to report on their compliance with the MMRs have been doing so. Contractors have not been using the IPP Reporting Solution for reporting.

25. Entities have not established appropriate controls and risk-based assurance activities to gain assurance over contractors’ reported MMR performance.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 3.17

National Indigenous Australians Agency develops tailored guidance on managing the MMRs throughout the contract lifecycle in consultation with entities and contractors.

National Indigenous Australians Agency response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 3.35

National Indigenous Australians Agency implements a strategy to increase entity and contractor compliance with MMR reporting requirements to ensure information in the IPP Reporting Solution is complete.

National Indigenous Australians Agency response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.3

Paragraph 3.46

National Indigenous Australians Agency implements an evaluation strategy for the MMRs that outlines an approach to measuring the impact of the policy on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander employment and business outcomes.

National Indigenous Australians Agency response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.4

Paragraph 4.19

All audited entities review and update their procurement protocols to ensure procuring officers undertaking major procurements that trigger the MMRs comply with required steps in the procurement process.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Department of Education, Skills and Employment response: Agreed.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications response: Agreed.

National Indigenous Australians Agency response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.5

Paragraph 4.37

All audited entities establish processes, or update existing processes, to ensure contract managers and contractors regularly use the IPP Reporting Solution for MMR reporting.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Department of Education, Skills and Employment response: Agreed.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications response: Agreed.

National Indigenous Australians Agency response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.6

Paragraph 4.48

After guidance has been provided by the policy owner, all audited entities establish appropriate controls and risk-based assurance activities for active MMR contracts.

Department of Defence response: Agreed.

Department of Education, Skills and Employment response: Agreed.

Department of Home Affairs response: Agreed.

Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications response: Agreed.

National Indigenous Australians Agency response: Agreed.

Summary of entity responses

26. Summary responses from audited entities are below. Entities’ full responses are at Appendix 1.

National Indigenous Australians Agency

The National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA) welcomes the Australian National Audit Office’s (ANAO) report on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Participation Targets in Major Procurements.

It is pleasing the ANAO has concluded that the design of the mandatory minimum requirements (MMR) element of the Indigenous Procurement Policy (IPP) supports the achievement of the Government’s policy objectives and that the policy settings are reasonable and supported by evidence.

The IPP is a key plank of the Government’s approach to driving growth in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander businesses and employment, by creating opportunities for Indigenous Australians to enter the government’s supply chain. The positive impact the IPP has made, in a relatively short period of time, has attracted the attention of many governments in Australia and abroad.

The NIAA considers the audit would have benefited from greater acknowledgement of the scale of the reform. The IPP represents a significant change to how the Australian Government procures goods and services. It challenges procurement officers to step outside often deeply ingrained and, in some cases, rigid procurement processes to consider how they could preference their procurement activities to benefit Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people while still achieving value for money for the Government.

The ANAO has identified a number of opportunities for the NIAA to improve the implementation of the MMR. While the NIAA has been active in informing and supporting stakeholders to implement the MMR, it is acknowledged that there is a need to build on existing MMR guidance materials and communications strategies by adopting a more tailored approach.

The NIAA also acknowledges that our ability to report fully on the impact of the MMR is hampered by the underuse of the IPP Reporting Solution (IPPRS) by the entities managing these contracts. While the NIAA stands by the IPPRS as an effective tool to manage the MMR, the NIAA is committed to seeing it continually evolve as lessons are learnt and new technology is released.

The NIAA agrees with each of the recommendations and will increase implementation efforts in the lead up of the expansion of the MMRs from 1 July 2020.

Department of Defence

Defence acknowledges the findings contained in the audit report on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Participation Targets in Major Procurements and agrees to the recommendations.

Overall, Defence considers the findings presented by the ANAO are weighted toward observations of non-compliance with limited consideration given to better practice. The Defence Indigenous Procurement Strategy outlines Defence’s commitment and pathway to delivering Indigenous Procurement Policy outcomes. As the Commonwealth’s largest procurer, Defence continues to exceed portfolio targets for contracts awarded to Indigenous suppliers. A number of Defence contracts voluntarily include Mandatory Minimum Requirements (MMRs), despite being exempt or categorised outside of a specified industry sector. Inclusion of this information would present a more balanced view of Defence’s management of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participation targets in major procurements.

Defence is proud to have been awarded the 2017 and 2019 Supply Nation Government member of the year award, in recognition of its significant commitment towards supporting the long term growth and sustainability of the Indigenous business sector. Defence will continue working with National Indigenous Australians Agency to improve the implementation and monitoring of the MMRs.

Department of Education, Skills and Employment

The Department of Education, Skills and Employment (the department) acknowledges the Australian National Audit Office’s (ANAO) report and its conclusions on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Targets in Major Procurements and welcomes its findings.

The department notes and agrees with recommendations made by the ANAO within its report and will use these recommendations to further strengthen its commitment to leveraging the department’s annual procurement spend to drive demand for Indigenous goods and services, stimulate Indigenous economic development and grow the Indigenous business sector.

Department of Home Affairs

The Department is committed to assist in the implementation of the Government’s policy objective to drive growth in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander businesses and employment.

The Department agrees with the three recommendations made to audited entities by the Auditor-General aimed at increasing compliance with the MMRs and will review and update its existing guidance and processes to better support compliance with the MMRs.

Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications2

The Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Cities and Regional Development (the Department) acknowledges the ANAO’s overall conclusions and welcomes the recommendations to improve guidance and monitoring of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participation in major procurement projects. The audit process was a valuable exercise and the feedback provided by the ANAO will assist the department in refining its approach to strengthen future compliance.

The Department remains committed to ensuring compliance with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participation targets in major procurement. While the ANAO report indicates that the Department excluded two contracts from the Mandatory Minimum Requirements (MMRs) for an invalid reason, these contracts were excluded on the basis of advice provided by the policy owner. In line with the recommendations the Department would welcome clearer guidance from the policy owner in future on the application of exclusion categories for the MMRs.

The Department also notes the requirement to deliver significant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander employment or supplier use outcomes in remote area contracts is very difficult to achieve on a contractual basis in some of Australia’s external Territories which have very low Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Procurement

Contract management

1. Background

1.1 Reducing the disparity between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander3 and non-Indigenous economic outcomes has been a longstanding goal of Australian governments. In March 2008 the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) set a target to halve the gap in employment outcomes by 2018. However, as noted in the Prime Minister’s Closing the Gap Report 2020, the COAG employment target was ‘not met’ (see Figure 1.1).4

Figure 1.1: Progress towards halving the gap in employment outcomes by 2018a

Note a: Data sources used to assess progress against this target include the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey and Social Survey, which are not conducted annually. Employment data for 2008 and 2012 included participants in Community Development Employment Projects.

Source: National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA) internal documentation.

1.2 Reasons for this disparity, identified through research into the determinants of lower Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander employment rates, include: ‘lower levels of education, training and skill levels (human capital), poorer health, living in areas with fewer labour market opportunities, higher levels of arrest and interactions with the criminal justice system, discrimination, and lower levels of job retention’.5

1.3 To address the issue of ‘fewer labour market opportunities’, over the past three decades the Australian Government has sought to use its position as a major procurer of goods and services in the Australian economy to generate economic opportunities for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. In 2018–19 the total value of Australian Government procurement contracts reported on AusTender (the government’s procurement information system) was $64.5 billion.6

Procurement initiatives to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander economic opportunities

1.4 The Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) outline the rules officials undertaking procurement must follow.7 The core requirement of the CPRs is achieving value for money. Price is not the sole factor for assessing value for money — procuring officers must consider other factors such as quality, fitness for purpose, environmental sustainability and whole-of-life costs. For procurements over $4 million (or $7.5 million for construction services), officers must also consider the broader benefits to the Australian economy. In addition, officers must comply with any relevant ‘procurement-connected policies’.8 Since the 1990s the Australian Government has implemented several procurement-connected policies to promote economic opportunities for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Indigenous Opportunities Policy (1998–2015)

1.5 In 1993 procurement-connected policies to promote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander employment opportunities were introduced in response to recommendations of the 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. Revised requirements were developed in 1998, which became known as the Indigenous Opportunities Policy (IOP). The IOP applied to procurements over $5 million ($6 million for construction projects) in locations with significant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations and limited employment and training opportunities.

1.6 From 1 July 2011 a revised IOP was introduced. This retained the same value threshold as the previous policy but expanded its geographic application to regions where the percentage of population who identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander was equal to or higher than the national average. For government contracts that met the value and geographic criteria, the 2011 IOP required tenderers to: develop an Indigenous Training, Employment and Supplier Plan; obtain approval of the plan from the IOP Administrator9; and, if awarded the contract, implement the plan and report annually to the policy owner on outcomes achieved.10 In addition to the IOP, in 2011 an ‘Indigenous business exemption’ was introduced into the CPRs that allowed officers to undertake a streamlined process for procurements over $80,000, avoiding the need for an open tender if they directly approached Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander businesses.11

Indigenous Procurement Policy (2015–present)

1.7 In May 2015 the government introduced the Indigenous Procurement Policy (IPP). The objective of the IPP is to ‘stimulate Indigenous entrepreneurship and business development, providing Indigenous Australians with more opportunities to participate in the economy’.12 Under the IPP, since 1 July 2015 non-corporate Commonwealth entities have been required to:

- achieve annual targets for procuring goods and services from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander enterprises;

- ‘set aside’ all remote area procurements, and all non-remote area domestic procurements with a value of $80,000 to $200,000 (other than in certain exempt categories), to determine whether an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander business could deliver value for money before approaching the broader market; and

- apply mandatory minimum requirements (MMRs) for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participation to high value contracts in certain industry categories.13

1.8 As a procurement-connected policy under the CPRs, compliance with the IPP is mandatory for non-corporate Commonwealth entities under sections 15 and 21 of the Public, Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013.

1.9 In February 2019 the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) reported that the IPP had resulted in 1,473 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander enterprises delivering 11,933 contracts worth over $1.83 billion. Noting that the majority of the contracts won had been low value contracts, it announced the following updates to the IPP:

- from 1 July 2019, additional entity procurement targets based on a percentage of the value of contracts awarded, with new targets increasing from one per cent in 2019–20 to three per cent in 2027–28; and

- from 1 July 2020, expansion of the MMRs to cover additional industry categories.14

1.10 Responsibility for the IPP transferred from PM&C to the newly created National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA) on 1 July 2019 through a machinery-of-government change.

Mandatory minimum requirements for major procurements

1.11 The objective of the MMRs is to ‘ensure that Indigenous Australians gain skills and economic benefit from some of the larger pieces of work that the Commonwealth outsources, including in Remote Areas’.15 Under the MMRs, for contracts with a value of $7.5 million or above in specified industry categories (see Table 1.1), contractors must achieve over the term of the contract:

- an average of at least four per cent Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander employment and/or supplier use for the project (contract-based); or

- an average of at least three per cent Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander employment and/or supplier use across their organisation (organisation-based).

1.12 Contractors must specify how they plan to achieve the MMRs in an Indigenous Participation Plan, which forms a schedule to the resultant contract. Where a component of the contract will be delivered in a remote area, the contracting entity and contractor must also ensure the contract delivers ‘significant Indigenous employment or supplier use outcomes in that area’.16

Table 1.1: MMR industry category coverage

|

Original MMR industry categories from 1 July 2015 |

Additional MMR services industry categories from 1 July 2020 |

|

|

Note a: Sub-category exclusions apply to these categories.

Source: PM&C, Commonwealth Indigenous Procurement Policy, Commonwealth of Australia, 2015; PM&C, Changes to the Indigenous Procurement Policy [Internet], 13 February 2019.

Previous audit coverage

1.13 Auditor-General Report No.1 2015–16 Procurement Initiatives to Support Outcomes for Indigenous Australians examined the effectiveness of the 2011 IOP and Indigenous business exemption. Issues identified through the audit included:

- practical challenges in determining whether the ‘main contract activities’ were within an IOP region, particularly in cases where contracted activities occurred in multiple locations;

- entities not complying with the IOP requirements for procurements that met the value and geographic criteria;

- entities not being required to include suppliers’ IOP commitments in contracts or monitor their implementation; and

- challenges for the policy owner in centrally monitoring implementation of the IOP and Indigenous business exemption due to AusTender not holding data on the geographic location of procurements or use of the exemption.17

1.14 The ANAO made three recommendations, which were agreed by PM&C and supported by the Department of Finance, aimed at developing alternative models to the regional approach of the IOP, and better promoting and monitoring of the Indigenous business exemption.18

2017 Senate Inquiry into the Community Development Program

1.15 In 2017 the Senate Finance and Public Administration References Committee (the committee) held an inquiry into appropriateness and effectiveness of the objectives, design, implementation and evaluation of the Community Development Program. The Community Development Program is an employment program administered by NIAA that requires job seekers in remote areas to engage in ‘work-like activities that benefit their community’.19 The majority (around 84 per cent) of participants are Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people, often living in areas with few labour market opportunities.

1.16 Noting the importance of using Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander employment targets in government procurement contracts as a tool for increasing economic activity in remote areas, the committee made the following recommendation relating to this issue:

Recommendation 17: The committee recommends that the Australian National Audit Office conduct an audit of Australian Government contracts that relate to service delivery in remote locations. This audit should have a specific focus on the use of, and compliance with, Indigenous Employment Targets. As part of this audit, the committee recommends that the Australian National Audit Office include state and territory government contracts where the Australian Government has made a funding contribution for a particular purpose. The audit should also report on how these contracts impact on Closing the Gap employment targets.20

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.17 The MMRs are the Australian Government’s principal mechanism for applying Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participation targets in major procurements. As the MMRs have been in operation since July 2015, and binding on contractors since July 2016, their administration by the policy owner (PM&C until June 2019 and NIAA since July 2019) and application by government entities should be relatively mature.

1.18 This audit was undertaken to provide assurance that the MMRs are being effectively administered and entities are complying with them. The audit includes a focus on the application of the MMRs in remote areas, to address the Senate Finance and Public Administration References Committee’s recommendation that the ANAO conduct an audit of Australian Government contracts relating to service delivery in remote locations. The audit timing also presents an opportunity for NIAA to address any identified areas for improvement prior to expanding the MMRs to cover eleven additional industry categories from 1 July 2020.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.19 The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of the administration of the MMRs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participation in major government procurements in achieving policy objectives.

1.20 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high level audit criteria:

- Are the MMRs designed to achieve the government’s policy objectives? (Chapter 2)

- Are the MMRs being implemented and monitored effectively? (Chapter 3)

- Are entities complying with the MMRs in major procurements? (Chapter 4)

1.21 While the scope of the audit includes examining the design, implementation and management of the MMRs, it does not include examining the operation of other components of the IPP; namely, the operation of the annual entity procurement targets, mandatory set aside and Indigenous business exemption.

1.22 The ANAO is also conducting a related performance audit examining the use of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participation targets in intergovernmental agreements, which is due to be tabled in 2020. The related audit focuses on the use of participation targets for major intergovernmental infrastructure projects, particularly in remote locations, and the Australian Government’s approach to coordinating procurement policies across jurisdictions.

Audit methodology

1.23 Six entities were selected for examination in the entity compliance component of the audit, based on the number and nature of MMR contracts they held: Department of Defence; Department of Education; Department of Employment, Skills, Small and Family Business; Department of Home Affairs; Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Cities and Regional Development; and NIAA.21

1.24 The audit methodology included:

- conducting compliance testing of a representative sample of 139 major procurement contracts that had triggered the MMR criteria from the six selected entities;

- analysing relevant datasets and examining other entity documentation;

- interviewing entity personnel, including procuring officers and contract managers for MMR contracts; and

- interviewing external stakeholders, including contractors subject to the MMRs.

1.25 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $316,000.

1.26 The team members for this audit were Daniel Whyte, Lynette Tyrrell, Iain Gately, James Woodward and Deborah Jackson.

2. Policy design

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) and National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA) have designed the mandatory minimum requirements (MMRs) to achieve the government’s policy objectives.

Conclusion

The design of the MMRs supports the achievement of the government’s policy objectives. The MMR policy settings are reasonable and supported by evidence.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made one suggestion regarding extending coverage of the MMRs to Commonwealth corporate entities and companies.

2.1 The design of policy settings such as coverage and exemption criteria is important because inappropriate settings can lead to inconsistent application of the policy requirements, unintended consequences and failure to achieve desired policy outcomes. In order to assess whether the policy owner (PM&C until June 2019 and NIAA from July 2019) designed the MMRs to support the achievement of the Australian Government’s policy objectives, the ANAO examined whether:

- the design aligned to the government’s policy objectives;

- the design was informed by stakeholder views and previous experience;

- the coverage of the MMRs supports the objectives; and

- appropriate criteria have been established for setting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participation targets against which to measure performance.

Was the design of the MMRs aligned to the Australian Government’s policy objectives?

The design of the MMRs aligns with the government’s policy objectives, which were to drive growth in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander businesses and employment.

2.2 In late 2014, in response to the 2014 Creating Parity – The Forrest Review report22, the government decided to strengthen the Indigenous Opportunities Policy (IOP) by including MMRs in all contracts in regions with significant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations. Policy documents to support the government’s decision provided limited detail on the policy settings for the MMRs, and noted that requirements would vary based on the value of the contract and potentially on the location and type of procurement.

2.3 The Minister for Indigenous Affairs and Minister for Finance agreed to the approach for implementing the policy in May 2015, and wrote a joint letter to the Prime Minister noting the approach was ‘slightly broader’ than what had been envisaged by the government. Refinements of the policy included: expanding the geographical coverage of the requirements to the whole of Australia; limiting coverage to eight specified industry categories; and applying a contract value threshold of $7.5 million.

2.4 Policy documents for the Indigenous Procurement Policy (IPP), prepared in late 2014, indicate that the policy rationale was to close the gap in employment outcomes between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and non-Indigenous Australians by driving growth in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander businesses and employment. The policy objective outlined in the IPP, released in May 2015, is to ‘stimulate Indigenous entrepreneurship and business development, providing Indigenous Australians with more opportunities to participate in the economy’.23 The IPP also notes ‘Indigenous enterprises are around 100 times more likely to employ Indigenous people than non-Indigenous enterprises and strengthening the Indigenous business sector will also have a significant flow-on impact on Indigenous employment’.24

2.5 The objective of the MMRs is to ensure Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people ‘gain skills and economic benefit’ from large projects outsourced by the government.25 The MMRs also have the potential to lead to direct employment outcomes if contractors undertake actions they would not otherwise have taken to achieve a MMR employment target. As such, the design of the MMRs aligns with the government’s policy objectives, which were to drive growth in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander businesses and employment.

Was the design of the MMRs informed by stakeholder views and previous experience?

The design of the MMRs was partially informed by stakeholder views and previous experience. The MMRs addressed concerns raised with the previous Indigenous Opportunities Policy, and PM&C consulted government entities with significant procurement activities. PM&C did not consult non-Indigenous businesses that would be affected by the MMRs and did not adequately consider previous experience with implementation challenges.

2.6 The Department of Finance’s guidance on developing procurement-connected policies states that the policy owner must ‘undertake appropriate consultation with affected stakeholders’.26 Further, as there has been several previous procurement-connected policies to achieve Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander economic outcomes, good practice would be to consider lessons learnt from previous experience with these policies in designing the MMRs. This section examines these two components of the design of the MMRs.

Consultation with affected stakeholders

Consultation with government stakeholders

2.7 In developing the IPP, PM&C undertook targeted consultation within government through the Indigenous Procurement Cross Agency Working Group. The working group comprises senior executive officers from PM&C, the Department of Finance (Finance), the Treasury and government entities with significant procurement activities.27 It has continued to meet since 2014 to consider aspects of the design of the IPP requirements, including the MMRs.

2.8 As a result of consultation with the Cross Agency Working Group, ministers agreed to: expanding the geographical coverage of the requirements to the whole of Australia; limiting coverage to eight specified industry categories; and applying a contract value threshold of $7.5 million.

Consultation with stakeholders outside government

2.9 Stakeholders outside of government had been consulted in 2013 and 2014 to inform the Creating Parity – The Forrest Review report, and some provided submissions regarding procurement policy matters.28 Between December 2014 and May 2015, the period during which the IPP was being developed, PM&C consulted Indigenous Business Australia, Supply Nation29 and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander businesses about the IPP in general.

2.10 PM&C’s implementation plan for the IPP, developed in December 2014, committed to testing the proposed approach for the MMRs and discussing compliance burden with non-Indigenous suppliers to government prior to finalising the policy settings. As a number of suppliers that would be affected by the MMRs had previously held IOP contracts, there would have been benefit in consulting suppliers or their representative bodies on the proposed policy settings. However, consultation with non-Indigenous businesses that would be affected by the MMRs did not occur.

Previous experience with procurement-connected policies to achieve Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander economic outcomes

Previous experience with the IOP

2.11 The Creating Parity review found the IOP had ‘failed to deliver meaningful results’ and ‘lacked any kind of accountability, sanctions or incentives to compel agencies or their contracted suppliers to comply’.30 To address this, the review team made a series of recommendations about government procurement, including that government entities require non-Indigenous contractors to commit to meeting minimum Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participation targets.31 Components of the 2014 Creating Parity review’s recommendations that were integrated into the design of the MMRs include:

- requiring contracting entities to include targets in contracts and enforce compliance;

- setting higher targets in remote areas, having regard to the local Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander population; and

- factoring contractors’ prior MMR performance into future procurement decisions.

2.12 The changes from the IOP to the MMRs also addressed Recommendation No.1 of Auditor-General Report No.1 2015–16 that PM&C review the regional approach of the IOP and advise the government on alternative models for applying minimum participation requirements.32

Previous experience with implementation challenges

2.13 While the design of the MMRs responded to previous experience with the IOP, and directly addressed issues identified in the Creating Parity report and Auditor-General Report No.1 2015–16, procurement-connected policies to promote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander economic development have historically experienced implementation challenges.

- A 1996 evaluation of the procurement-connected policies arising from the 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody found they had been unsuccessful due to implementation problems, including a lack of accountability, insufficient monitoring and enforcement, and inadequate awareness and understanding of the requirements.33

- The effectiveness of the 2011 IOP was undermined by entities not understanding or complying with the requirements, and challenges experienced by the policy owner in monitoring compliance and outcomes.34

2.14 PM&C’s implementation plan for the IPP was developed in December 2014, before the detailed policy settings for the MMRs were agreed, and did not contain any detail on implementation and monitoring arrangements for the MMRs. PM&C did not subsequently develop an updated implementation plan after the MMR policy details had been settled. Further, its planning did not adequately address how implementation challenges that had been experienced with previous policies would be managed for the MMRs.35

Does the coverage of the MMRs support the achievement of policy objectives?

The industry coverage criteria and contract value threshold for the MMRs support the government’s policy objectives by achieving broad coverage while limiting compliance burden. Categories for exempting or excluding contracts from the MMRs are appropriate. Applying the policy to Commonwealth corporate entities and companies would broaden opportunities for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to gain skills and economic benefit from large government projects.

2.15 Coverage is an important consideration in developing regulatory policies. If coverage is too broad, a regulation can impose unnecessary compliance burden on businesses with limited capacity to achieve the policy objectives. If coverage is too narrow, a regulation will fail to deliver its intended outcomes. This section examines the coverage of the MMRs, focusing on:

- specified industry sectors;

- the contract value threshold;

- exemption and exclusion criteria; and

- Commonwealth corporate entities and companies.

Specified industry sectors

2.16 When government entities undertake procurements through AusTender, the category of goods or services procured is recorded using the United Nations Standard Products and Services Code (UNSPSC). There is no requirement to record the location where goods or services will be used or delivered, and in many cases supply chains span various locations. Consequently, limiting the coverage of the MMRs by industry category rather than by location presents practical benefits, as it is easier to identify if contracts trigger the requirements.

2.17 In March 2015 PM&C proposed applying the MMRs to industry categories that ‘present strong opportunities for Indigenous participation’.36 It initially suggested five UNSPSC categories that had high levels of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander employment or businesses, based on 2011 Census data. Through consultation with the Cross Agency Working Group, the categories were revised to the eight included in the May 2015 IPP (see Table 1.1).

2.18 The IPP states that MMR contracts will be ‘reviewed each year to ensure that the targeted group of contracts are achieving the intended outcome’.37 While such reviews did not occur for the first two years of the IPP38, in 2018 PM&C commissioned a ‘third year’ evaluation of the IPP that considered this question. The draft evaluation report provided to PM&C in November 2018 noted that ‘it cannot be confirmed that the MMR is delivering intended increased business to Indigenous businesses’ due to data limitations.39 Nevertheless, the evaluation team recommended expanding the MMRs to cover all industry categories on the basis that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander businesses had demonstrated growth in a broad range of industries.

Expansion of industry coverage from mid-2020

2.19 In late 2018 the government agreed to increase the number of UNSPSC categories relating to the procurement of services that trigger the MMRs from 1 July 2020, with final details to be determined by the ministers for Indigenous Affairs and Finance in the first half of 2019. PM&C analysed AusTender data and consulted with government entities through the Cross Agency Working Group in early 2019, and in April 2019 the Indigenous Affairs and Finance ministers agreed to expand the MMRs to cover 19 of the 20 UNSPSC services categories used by AusTender. Based on consultation with procuring entities, one services category was excluded in full (public utilities and public sector related services) and sub-category exclusions were agreed for three other categories. Appendix 2 provides a full list of UNSPSC categories covered by the MMRs from July 2015 and July 2020.

2.20 Table 2.1 shows the proportion of AusTender contract notices from 2017–18 and 2018–19 that fall within the original eight UNSPSC categories and the expanded set of 19 UNSPSC categories by number and value. This analysis indicates the expansion of industry coverage from 2020 could more than double the number of contracts triggering the MMRs and triple the value of procurement covered. Around half of contracts triggering the MMRs fall within the Defence portfolio (analysis by portfolio is at Appendix 3).

Table 2.1: Number and total value of 2017–18 and 2018–19 AusTender contracts triggering the 2015 and 2020 MMR industry coverage criteriaa

|

|

Number of contracts |

Total value of contracts |

||

|

|

2015 MMR categories |

2020 MMR categories |

2015 MMR categories |

2020 MMR categories |

|

Contracts over $7.5 million |

176 |

453 |

$9,145,683,296 |

$29,946,808,572 |

|

Proportion of all contracts |

0.15% |

0.38% |

10.18% |

33.34% |

Note a: Some of these contracts will be exempt from the MMRs for reasons discussed later in this chapter.

Source: ANAO analysis of non-corporate Commonwealth entity AusTender contract notice data.

Contract value threshold

2.21 The 2014 Creating Parity review recommended including minimum participation requirements in all government contracts. In developing the MMRs in consultation with the Cross Agency Working Group, PM&C proposed a $7.5 million contract value threshold to achieve the greatest ‘bang for buck’. Its analysis of AusTender data demonstrated that a $7.5 million threshold would capture a relatively small proportion of contracts that account for a large proportion of government procurement expenditure. The $7.5 million threshold was agreed by the ministers for Finance and Indigenous Affairs in May 2015. As shown in Table 2.1, the 176 contracts (0.15 per cent of all contracts) that triggered the MMRs in 2017–18 and 2018–19 account for 10.18 per cent of the total value of contracts. This demonstrates that the contract value threshold achieves broad coverage, which supports the achievement of the government’s policy objectives, while limiting the compliance burden.

Exemption and exclusion criteria

2.22 The 2015 IPP outlines one explicit exemption from the MMRs for contracts that are subject to paragraph 2.6 of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs). This relates to procurements:

… necessary for the maintenance or restoration of international peace and security, to protect human health, for the protection of essential security interests, or to protect national treasures of artistic, historic or archaeological value.40

2.23 The IPP also states that the MMRs apply only to new contracts from non-corporate Commonwealth entities, which are delivered in Australia, and where the approach to market occurred after 1 July 2015. This creates four additional categories of contracts that are not covered by the MMRs:

- contracts that have an original value below the MMR threshold but subsequently meet the threshold through a contract variation (as these are not new contracts);

- contracts held by Commonwealth corporate entities or companies;

- contracts that are delivered outside Australia; and

- contracts resulting from approaches to market that pre-date the policy requirement.

2.24 In developing the IPP Reporting Solution, an online monitoring system for the IPP launched in 2018 (discussed in more detail in Chapter 3), PM&C built in five categories for exempting or excluding contracts from the MMRs: CPR exemption 2.6; original value below MMR threshold; non-mandated agency; international delivery; and other (which can be used to exclude procurements that pre-date the requirement). As at 30 June 2019, entities had used four of these categories to exempt or exclude 109 contracts from the MMRs through the system, with the majority (76 per cent) using the ‘other’ category (see Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1: Exemption and exclusion categories used by entities, as at 30 June 2019

Source: ANAO analysis of data from the IPP Reporting Solution

2.25 The categories in the IPP Reporting Solution for exempting or excluding contracts from the MMRs are reasonable and supported by the policy.41

Commonwealth corporate entities and companies

2.26 Commonwealth corporate entities and companies do not currently have mandated targets for procuring goods and services from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander businesses. Under the IPP, annual supplier use targets apply only to non-corporate Commonwealth entities. The IPP states:

Prescribed corporate Commonwealth entities listed in section 30 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 and Commonwealth entities that are not required to comply with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules are encouraged to use best endeavours to apply this policy.42

2.27 Based on a review of the 2017–18 annual reports of Commonwealth corporate entities and companies, only one (Australian Postal Corporation) had a published commitment to an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander supplier use target.

2.28 Further, Commonwealth corporate entities and companies do not currently have mandated targets for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander employment. On 1 July 2015 the Australian Public Service Commission implemented a whole-of-government Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander employment strategy, which aimed to ‘increase the representation of Indigenous employees across the Commonwealth public sector to three per cent by 2018’.43 The strategy, which applied to all corporate and non-corporate Commonwealth entities and any other bodies that employed staff under the Public Service Act 1999, expired at the end of 2018.

2.29 Requiring Commonwealth corporate entities and companies to achieve Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participation targets, both for procurement and employment, would broaden opportunities for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to gain skills and economic benefit from large government projects (the government’s objective for the MMRs). Further, if the government establishes a Commonwealth company to deliver a project within the MMR categories rather than outsourcing it to a contractor, an anomaly of the current arrangements is that the Commonwealth company would not have to meet the MMRs.

2.30 Accordingly, NIAA should provide advice to the government on how the policy requirements could be extended to Commonwealth corporate entities and companies. Such advice should have regard to the capacity of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander business sector to respond to increased demand.

Have appropriate criteria been established for setting participation targets?

The criteria established under the MMRs for setting participation targets are appropriate. The minimum target requirements allow contractors flexibility to choose targets appropriate to their situation. The criteria for remote targets allow flexibility to set targets above the minimum requirements that are appropriate to the services being procured and the remote area in which they will be delivered.

2.31 In developing regulatory policies, entities should ensure requirements are designed to achieve policy objectives while also allowing sufficient flexibility to account for the varying circumstances of regulated parties. This section examines the appropriateness of the criteria for setting minimum targets and remote area targets.

Criteria for setting minimum targets

2.32 For MMR contracts, over the course of the contract contractors must commit to achieving:

- an average of at least four per cent Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander employment and/or supplier use for the project (contract-based); or

- an average of at least three per cent Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander employment and/or supplier use across their organisation (organisation-based).

2.33 The ability to choose between these two options, and to split the target across employment and supplier-use targets, allows contractors the flexibility to nominate targets appropriate to their situation. Contractors interviewed by the ANAO indicated they appreciated having this flexibility, describing situations where it would have been challenging to meet either contract-based or organisation-based targets (for example, where the contract required a small number of staff with specific skills, such as fluency in Mandarin or Arabic, or where there were limitations on suppliers that could be used).

2.34 Box 1 provides two scenarios that illustrate the flexibility of the MMR targets.

|

Box 1: Options for setting MMR targets |

|

Scenario 1 — Delivery of specialist training services

Scenario 2 — Major construction project

|

Criteria for setting remote area targets

2.35 When the ministers for Indigenous Affairs and Finance approved the approach to implementing the policy in May 2015, it was decided that entities and contractors would need to agree targets higher than the minimum requirements where a part of the contract will be delivered in a remote area. In line with this, the IPP states that, where a component of an MMR contract will be delivered in a remote area, the contracting entity and contractor must ensure the contract delivers ‘significant Indigenous employment or supplier use outcomes in that area’ and targets should ‘have regard to the size of the local Indigenous population relative to the non-Indigenous population and the nature of the contracted goods and services’.44

2.36 These criteria provide substantial flexibility to contracting entities and contractors to agree targets greater than the minimum requirements that are appropriate to the services being procured and the remote area in which they will be delivered.45

3. Policy implementation and monitoring

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) and National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA) have implemented and monitored the mandatory minimum requirements (MMRs) effectively.

Conclusion

The MMRs have not been implemented and monitored effectively due to inadequate implementation planning and delays in establishing a centralised monitoring system. While the policy owner has publicised the MMRs, it has not provided entities and contractors sufficient guidance on complying with the MMRs. The current regime for enforcing compliance with MMR reporting requirements is not operating effectively and, as a result, the policy outcomes have not been evaluated.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made three recommendations aimed at: improving guidance available to entities on operationalising the MMRs; increasing compliance with MMR reporting requirements; and developing an appropriate evaluation strategy.

3.1 To implement and monitor a procurement-connected policy effectively, the policy owner should:

- develop an appropriate implementation plan;

- effectively communicate the policy requirements to support implementation;

- establish appropriate mechanisms for monitoring compliance and reporting on implementation; and

- regularly review the policy’s effectiveness in achieving its stated purpose and outcomes.46

3.2 This chapter examines whether the policy owner (PM&C until June 2019 and NIAA from July 2019) has addressed these elements in implementing and monitoring the MMRs.

Was an appropriate implementation plan developed for the MMRs?

PM&C did not develop an appropriate implementation plan for the MMRs in 2015. NIAA has developed an implementation plan for the 2020 expansion of the MMRs.

3.3 Implementation planning is an essential part of the policy design process. The MMRs impose regulatory requirements on contractors delivering a significant volume of services to the Australian Government (approximately 10 per cent of the goods and services procured by non-corporate Commonwealth entities by value). Further, policy owners have previously experienced challenges implementing similar procurement-connected policies to promote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander economic outcomes. Accordingly, PM&C should have developed an appropriate implementation plan for MMRs that covered:

- project phases, deliverables, timeframes and resources;

- implementation challenges, risks and mitigation strategies;

- key stakeholders and communication activities;

- governance arrangements; and

- mechanisms for monitoring and evaluating outcomes.47

3.4 PM&C developed an implementation plan for the Indigenous Procurement Policy (IPP) in December 2014. As the plan was developed before the detailed policy settings for the MMRs were agreed, it did not contain detail on implementation and monitoring arrangements for the MMRs. PM&C did not subsequently develop an updated implementation plan after the MMR policy details had been settled. Insufficient implementation planning, particularly regarding communicating detailed requirements and establishing a central monitoring system, undermined the effectiveness of the implementation and monitoring of the MMRs.

3.5 In mid-2019 PM&C announced that the MMRs would be expanded by eleven industry categories to cover a total of nineteen services industry categories. The expansion is expected to significantly increase the regulatory scale of the MMRs — more than doubling the number of contracts covered each year, and expanding coverage of non-corporate Commonwealth entity procurement to approximately 30 per cent by value.

3.6 In deciding to expand the MMRs, the government agreed that the ministers for Indigenous Affairs and Finance would develop an implementation approach for applying the expanded MMRs by mid-2019, including identifying the industry categories that would be covered. While the ministers agreed to the expansion of industry category coverage, an implementation approach was not developed.

3.7 In December 2019 NIAA developed an implementation plan to support the expansion of the MMRs from 1 July 2020 that covers the components outlined in paragraph 3.3 and includes implementation activities that address the recommendations in this chapter.

Have the MMRs been effectively communicated to support implementation?

Current arrangements for communicating the MMRs are partially effective. PM&C and NIAA have promoted awareness of the MMRs to relevant stakeholders through their communication activities. However, they have provided ineffective guidance and advice to entities and contractors on how to comply with the MMRs throughout the contract lifecycle to ensure intended outcomes are achieved.

3.8 To support the implementation of a policy requirement, it is good practice for the policy owner to identify who the key stakeholders are, what information they need and how best to communicate with them. If stakeholders lack awareness or understanding of what they need to do to comply with the policy, compliance will be low and intended policy outcomes will not be realised. This section examines the policy owners’ communication of the MMRs.

3.9 Since the launch of the IPP in May 2015, PM&C and NIAA have used various mechanisms to promote awareness and understanding of its requirements, which are outlined in Box 2. While communication activities have primarily focussed on the IPP as a whole, they have generally also included high-level coverage of the MMRs.

|

Box 2: Communication activities for the IPP |

|

Online guidance information Guidance material for the IPP has been published on PM&C’s and NIAA’s websites, including fact sheets, policy guides and model clauses for the MMRs. Social media and electronic mailing lists PM&C and NIAA have used social media channels and electronic mailing lists to publicise IPP events and policy updates. In particular, they have regularly included items in the Department of Finance’s monthly electronic procurement bulletin to entities. Formal consultative arrangements Cross Agency Working Group: Since late 2014 PM&C and NIAA have consulted with Australian Government entities through the Indigenous Procurement Cross Agency Working Group. National Indigenous Business Trade Fairs: Since 2017 Supply Nation has been funded through an Indigenous Advancement Strategy grant to run a series of trade fair events in Australian capital cities and regional locations, designed to connect Australian Government and corporate buyers with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander businesses and other support services. These events have included components designed to support businesses with MMR contracts in meeting their employment and supplier use targets. Informal processes PM&C and NIAA have maintained a shared email inbox for the IPP, which they have used to respond to stakeholder queries and requests for guidance. They have also held ad hoc meetings with stakeholders. |

3.10 PM&C commissioned a review of the IPP after its first year of operation (2015–16) and an evaluation after its third year (2017–18). Both the ‘year one’ review and ‘third year’ evaluation noted the need for increased education and training for government procuring officers, non-Indigenous suppliers and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander businesses. The integration of MMR components into the National Indigenous Business Trade Fair program was designed to address this suggestion, and has been well received by attendees.

3.11 As at October 2019 NIAA’s website provided guidance information on:

- the start date, industry category coverage and contract value threshold for the MMRs;

- steps entities need to follow when undertaking MMR procurements and managing MMR contracts;

- model clauses for inclusion in approaches to market and contracts; and

- how contractors can determine contract-based or organisation-based MMR targets and report against them.

3.12 While the guidance information explains policy requirements and processes at a high-level, it is difficult to navigate and not well tailored for different audiences. For example, all of the IPP information is grouped together with no indication of which guidance is relevant to particular stakeholders and there are no links on the website to guidance on the IPP Reporting Solution.

3.13 As the policy owner, NIAA is accountable for ensuring that the MMRs operate effectively and entities and contractors comply with their obligations. Procuring officers, contract managers and contractors interviewed by the ANAO felt they lacked understanding of the policy requirements and would have benefited from additional guidance. Based on this feedback, and the ANAO’s finding that entities have not been adequately complying with the MMRs (discussed in Chapter 4), specific areas where additional guidance is needed to increase compliance and support effective implementation of the MMRs are outlined in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1: Topics requiring additional guidance for the MMRs

|

Entity procuring officers |

Entity contract managers |

Contractors |

|

|

|

Source: ANAO analysis.

3.14 The ANAO also identified instances where PM&C provided inconsistent or incorrect guidance information and advice about the MMRs, which has caused confusion for stakeholders or led to cases of non-compliance.

- The IPP states the MMRs apply to contracts that meet the coverage criteria ‘where the Approach to Market commences after 1 July 2015’.48 However, guidance for the IPP Reporting Solution developed in 2018 stated the MMRs apply to contracts that commence ‘on or after 1 July 2016’, which was inconsistent with the policy.49 This caused confusion for one of the selected entities for this audit, which had several MMR contracts that commenced before 1 July 2016.

- While the IPP states the MMRs cover contracts within the ‘education and training services’ industry category, a factsheet published in 2015 (and available on PM&C’s website until 2017) omitted a key sub-category. This error led one of the selected entities to not comply with the MMRs for two education and training services contracts valued over $100 million.

- The IPP only includes one exemption category for the MMRs: for contracts subject to paragraph 2.6 of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs). However, the ANAO identified one instance when PM&C advised an entity that contracts with Commonwealth, state and territory entities are not covered by the MMRs, which led to contracts being incorrectly excluded.

3.15 To increase compliance and achieve policy outcomes, NIAA needs to develop a more comprehensive set of MMR guidance information that is tailored to key stakeholder groups and includes coverage of the topics identified in Table 3.1. It should also ensure that its advice to entities and contractors is consistent with the policy requirements and associated guidance information. In developing revised guidance, there is scope for NIAA to further leverage off the Department of Finance’s existing mechanisms for communicating procurement requirements under the CPRs.

3.16 In September 2019 NIAA advised the ANAO that it is working to develop new guidance information for specific stakeholder groups. It will be important to consult with entities and contractors to ensure the guidance meets their needs, and incorporate case studies and worked examples on how the requirements can be operationalised in different contexts.

Recommendation no.1

3.17 National Indigenous Australians Agency develops tailored guidance on managing the MMRs throughout the contract lifecycle in consultation with entities and contractors.

National Indigenous Australians Agency response: Agreed.

3.18 The NIAA will publish a revised IPP policy document and new guidance materials during the first quarter of 2020. This will include tailored guidance on the implementation of the mandatory minimum requirements for Commonwealth entities, major contractors and Indigenous businesses, developed in consultation with stakeholders.

Have appropriate mechanisms been established to monitor compliance and report on implementation?

PM&C has established a central database, the IPP Reporting Solution, which has the potential to monitor compliance and report on implementation of the MMRs. However, the system has not delivered on this potential due to delays in its rollout and low levels of uptake by entities and contractors. As a result, information in the system for MMR contracts is incomplete and cannot be used to assess contractors’ previous MMR performance or report on implementation.

3.19 The Department of Finance’s guidance on developing procurement-connected policies states that such policies ‘must be monitored and have an appropriate regime for addressing non-compliance’.50 This section examines:

- PM&C’s development of a central database for the MMRs, the IPP Reporting Solution;

- entity and contractor compliance with MMR reporting obligations; and

- the effectiveness of the system in facilitating assessment of contractors’ previous MMR performance and reporting on the implementation of the MMRs.

Development of the IPP Reporting Solution

3.20 PM&C’s March 2015 discussion paper to the Cross Agency Working Group, which outlined the proposed policy settings for the MMRs, included the following statements about the need for an efficient and effective monitoring system for the MMRs:

Effective enforcement of the [MMRs] will rely on agencies assessing Indigenous participation as part of the RFT process, and taking past performance into account. To do this efficiently, there will need to be a central database where contract managers can record performance against the contractual requirements, so that other agencies can assess past performance.

It is proposed that this central database be developed over the 2015-16 FY, so that it becomes available from 1 July 2016…

Agencies will be responsible for monitoring compliance and for entering information into a central database. The system will hinge on how effectively agencies do this.51

3.21 PM&C started planning the development of a central monitoring system for the MMRs in mid-2016 and briefed the Cross Agency Working Group on options in September 2016. Options considered at that time included: capturing MMR data in an Excel spreadsheet; developing a MMR reporting module through SAP (a software package many entities use for financial reporting); modifying a database used for Indigenous Opportunities Policy; and developing a custom database through PM&C’s Information Services Branch.

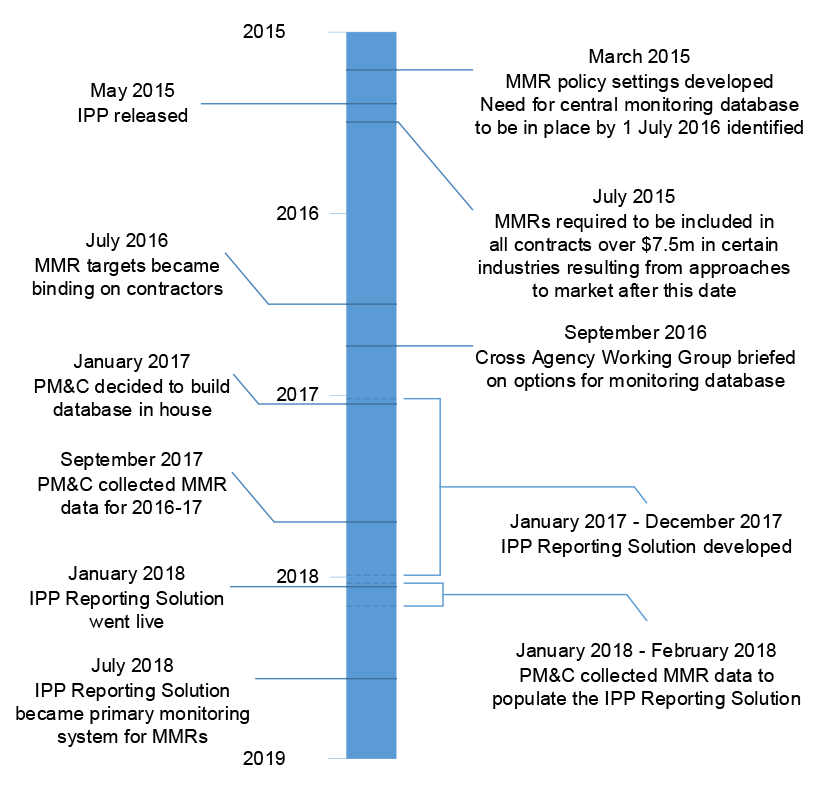

3.22 In January 2017 PM&C decided to build a custom database in house to automate the IPP reporting process, including for MMR contracts. It allocated $2 million funding over 2016–17 and 2017–18 for its development. The database, called the IPP Reporting Solution, was developed during 2017 and launched in January 2018. A timeline of key milestones in its development is at Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1: Timeline of IPP Reporting Solution development, 2015–2018

Source: ANAO analysis.

3.23 As shown in Figure 3.1, there were two spreadsheet-based data collections for the MMRs in 2017 and 2018. In September 2017, prior to the implementation of the IPP Reporting Solution, PM&C collected 2016–17 MMR reporting data from entities for aggregate public reporting. In December 2017 PM&C asked entities to submit quarterly reports for July 2016 to December 2017, which were entered into the system in January and February 2018. The quality of the reporting received from entities was inconsistent. From mid-2018, two years after the reporting requirement was established, entities were requested to use the IPP Reporting Solution for MMR reporting. The significant delays in establishing the system impacted on levels and quality of compliance with reporting obligations.

Compliance with MMR reporting obligations

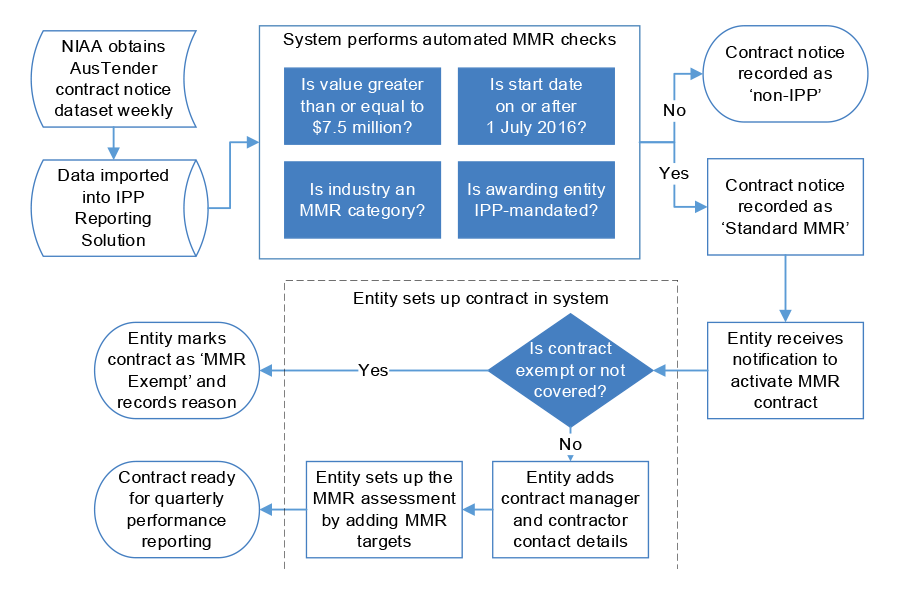

3.24 NIAA uses the IPP Reporting Solution to identify Australian Government contracts that have triggered the MMRs and establish what targets have been agreed between entities and contractors. As outlined in Figure 3.2, the process primarily involves: automated system checks of AusTender contract notice data; and entities setting up their MMR contracts in the system.

Figure 3.2: Process for setting up MMR contracts

Source: ANAO analysis of IPP Reporting Solution documentation.

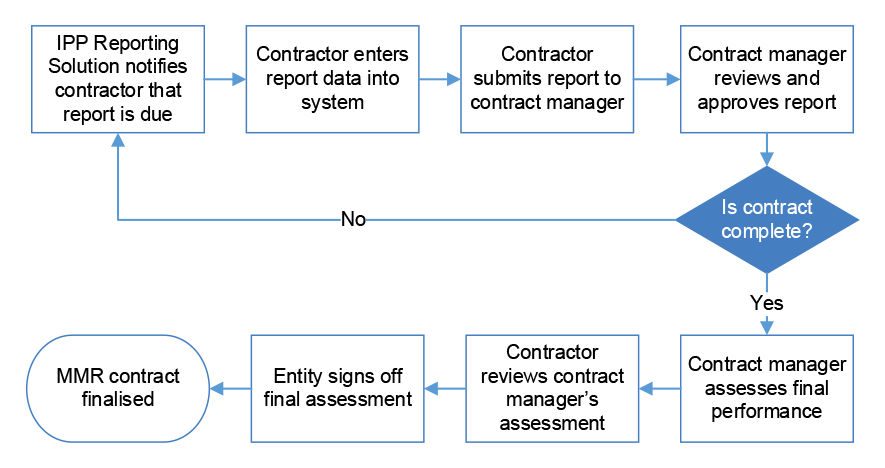

3.25 The IPP Reporting Solution also includes a Contractor Portal through which contractors need to submit quarterly performance reports outlining performance against their MMR targets for entity approval. When a MMR contract ends, the contracting entity needs to sign off a final assessment of compliance against the MMR participation targets. Figure 3.3 outlines this process.

Figure 3.3: Process for managing MMR performance reporting

Source: ANAO analysis of IPP Reporting Solution documentation.

3.26 There have been three key issues with the implementation of the IPP Reporting Solution that have limited its effectiveness for monitoring the MMRs:

- automated system checks not identifying all potential MMR contracts;

- entities not setting up or excluding contracts within the system; and

- entities and contractors not using the system to report on MMR performance.

Automated system checks are not identifying all potential MMR contracts

3.27 The ANAO obtained a data extract from the IPP Reporting Solution as at 30 June 2019 and tested its completeness and accuracy. No issues were identified with the completeness or accuracy of data imported from AusTender. However, two issues were identified relating to the automated system tests (see Box 3). As a result of these issues, contracts labelled as ‘Standard MMR’ within the IPP Reporting Solution as at 30 June 2019 were not a complete record of contracts that had triggered the MMR criteria.

|

Box 3: Issues with IPP Reporting Solution automated MMR checks |

|

Start date check based on incorrect premise The MMRs apply to all contracts meeting the coverage criteria with an approach to market after 1 July 2015, but targets did not become binding until 1 July 2016. The IPP Reporting Solution does not record the approach to market date for contracts. The IPP Reporting Solution has an automated MMR check that only captures notices with a contract start date on or after 1 July 2016. Consequently, the IPP Reporting Solution does not identify MMR contracts with a start date before 1 July 2016. There are 87 contracts with a total combined value of $6.3 billion that commenced in 2015–16 and potentially meet the MMR coverage criteria. Any that meet the coverage criteria are currently not included in NIAA’s dataset. To resolve this issue, NIAA could revise the IPP Reporting Solution’s automated MMR check to capture contracts with a start date on or after 1 July 2015, then request entities to exclude any contracts not covered. Contracts with incomplete data incorrectly labelled as ‘non-IPP’ Through data matching with procurement system datasets from selected entities52, the ANAO identified 28 contracts (which commenced in 2016–17, 2017–18 or 2018–19) with a combined total value of $2.4 billion that were incorrectly labelled as ‘non-IPP’ contracts within the IPP Reporting Solution. This represents approximately 10 per cent of the total number and value of contracts that triggered the MMR value threshold and industry coverage criteria over that period. The system failed to identify these contracts as ‘Standard MMR’ contracts because the AusTender contract notice data was incomplete when it was first imported. After the ANAO informed NIAA of this issue, NIAA indicated it had developed a report within the system that will enable it to identify any similar issues in the future and manually fix them. It stated that it would run a report after each import of data from AusTender. |

Entities are not setting up or excluding contracts within the system