Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

2017–18 Major Projects Report

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

The objective of this report is to provide the Auditor-General’s independent assurance over the status of the selected Major Projects. The status of the selected Major Projects is reported in the Statement by the Secretary of Defence and the Project Data Summary Sheets (PDSSs) prepared by Defence. Assurance from the ANAO’s review is conveyed in the Independent Assurance Report by the Auditor-General.

Due to the complexity of material and the multiple sources of information for the 2017-18 Major Projects Report, we are unable to represent the entire document in HTML. You can download the full report in PDF or view selected sections in HTML below. PDF files for individual Project Data Summary Sheets (PDSS) are also available for download.

!Part 1. ANAO Review and Analysis

Summary and Review Conclusion

About the Major Projects Report

1. Major Defence equipment acquisition projects (Major Projects) continue to be the subject of parliamentary and public interest. This is due to their high cost and contribution to national security, and the challenges involved in completing them within the specified budget and schedule, and to the required capability.

2. The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) has reviewed 26 of Defence’s Major Projects in this eleventh annual report (2016–17: 27). The Major Projects Report (MPR) reviews overall issues, risks, challenges and complexities affecting Major Projects and also reviews the status of each of the selected Major Projects, in terms of cost, schedule and forecast capability.1 The objective of the report is ‘to improve the accountability and transparency of Defence acquisitions for the benefit of Parliament and other stakeholders.’2

3. The Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG) within the Department of Defence (Defence), manages the process of bringing new capabilities into service.3 In 2017–18 Defence was managing 198 active major and minor capital equipment projects worth $103.5 billion, with an in-year budget of $6.9 billion.4 Defence capitalised some $7.5 billion from these projects in 2017–18.5

4. The February 2016 Defence White Paper established the Government’s priorities for future capability investment for the next 20 years and provided for additional spending of over $29 billion across the next decade. The 2018–19 Defence Portfolio Budget Statements indicated that the Defence budget would grow approximately $200 billion over the coming decade, for investing in Defence capability.6 The Government commenced its $89 billion investment in Australia’s future shipbuilding industry in April 20177, and on 29 June 2018 announced Second Pass Approval of the $35 billion Future Frigate program.8

Major Projects selected for review

5. Major Projects are selected for review based on the criteria included in the 2017–18 Major Projects Report Guidelines (the Guidelines), as endorsed by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA).9 They represent a selection of the most significant Major Projects managed by Defence.

6. The total approved budget for the Major Projects included in this report is approximately $59.4 billion, covering 57 per cent of the total budget of active major and minor capital equipment projects of $103.5 billion.10 The selected projects are listed in Table 1.

Table 1: 2017–18 MPR projects and approved budgets at 30 June 2018 1, 2, 3

|

Project Number (Defence Capability Plan) |

Project Name (on Defence advice) |

Abbreviation (on Defence advice) |

Approved Budget $m |

|

AIR 6000 Phase 2A/2B |

New Air Combat Capability |

Joint Strike Fighter |

15,504.0 |

|

SEA 4000 Phase 3 |

Air Warfare Destroyer Build |

AWD Ships |

9089.3 |

|

AIR 7000 Phase 2B |

Maritime Patrol and Response Aircraft System |

P-8A Poseidon |

5212.0 |

|

AIR 9000 Phase 2/4/6 |

Multi-Role Helicopter |

MRH90 Helicopters |

3771.1 |

|

AIR 5349 Phase 3 |

EA-18G Growler Airborne Electronic Attack Capability |

Growler |

3430.4 |

|

AIR 9000 Phase 8 |

Future Naval Aviation Combat System Helicopter |

MH-60R Seahawk |

3430.3 |

|

LAND 121 Phase 3B |

Medium Heavy Capability, Field Vehicles, Modules and Trailers |

Overlander Medium/Heavy |

3428.9 |

|

JP 2048 Phase 4A/4B |

Amphibious Ships (LHD) |

LHD Ships |

3091.7 |

|

LAND 121 Phase 4 |

Protected Mobility Vehicle – Light |

Hawkei |

1952.0 |

|

AIR 8000 Phase 2 |

Battlefield Airlift – Caribou Replacement |

Battlefield Airlifter |

1433.3 |

|

SEA 1654 Phase 3 |

Maritime Operational Support Capability |

Repl Replenishment Ships |

1066.8

|

|

AIR 5431 Phase 3 |

Civil Military Air Traffic Management System |

CMATS |

974.2 |

|

JP 2072 Phase 2B |

Battlespace Communications Systems |

Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) 2B |

920.1 |

|

AIR 7403 Phase 3 |

Additional KC-30A Multi-role Tanker Transport |

Additional MRTT |

887.8 |

|

SEA 1448 Phase 2B |

ANZAC Anti-Ship Missile Defence |

ANZAC ASMD 2B |

678.7 |

|

SEA 3036 Phase 1 |

Pacific Patrol Boat Replacement |

Pacific Patrol Boat Repl |

501.2 |

|

AIR 9000 Phase 7 |

Helicopter Aircrew Training System |

HATS |

481.5 |

|

SEA 1439 Phase 4A |

Collins Replacement Combat System |

Collins RCS |

450.5 |

|

JP 2072 Phase 2A |

Battlespace Communications System |

Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) 2A |

438.0 |

|

SEA 1442 Phase 4 |

Maritime Communications Modernisation |

Maritime Comms. |

437.7 |

|

SEA 1429 Phase 2 |

Replacement Heavyweight Torpedo |

Hw Torpedo |

427.6 |

|

JP 2008 Phase 5A |

Indian Ocean Region UHF SATCOM |

UHF SATCOM |

419.9 |

|

SEA 1439 Phase 3 |

Collins Class Submarine Reliability and Sustainability |

Collins R&S |

411.6 |

|

SEA 1448 Phase 2A |

ANZAC Anti-Ship Missile Defence |

ANZAC ASMD 2A |

386.8 |

|

LAND 75 Phase 4 |

Battle Management System |

BMS |

367.9 |

|

JP 2048 Phase 3 |

Amphibious Watercraft Replacement |

LHD Landing Craft |

236.7 |

|

Total 26 |

|

|

59,430.0 |

Note 1: Once a project is selected for review, it remains within the portfolio of projects under review until the JCPAA endorses its removal, normally once it has met the capability requirements of Defence.

Note 2: SEA 1654 Phase 3 Maritime Operational Support Capability (Repl Replenishment Ships), JP 2072 Phase 2B Battlespace Communications System (Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) 2B) and SEA 3036 Phase 1 Pacific Patrol Boat Replacement (Pacific Patrol Boat Repl) are included in the MPR for the first time in 2017–18.

Note 3: SEA 1439 Phase 3 Collins Class Submarine Reliability and Sustainability is a group of 22 activities primarily sustainment in nature. While not an acquisition project, it has been included at the JCPAA’s request.

Source: The Project Data Summary Sheets in Part 3 of this report.

Report objective and scope

7. The objective of this report is to provide the Auditor-General’s independent assurance over the status of the selected Major Projects. The status of the selected Major Projects is reported in the Statement by the Secretary of Defence and the Project Data Summary Sheets (PDSSs) prepared by Defence. Assurance from the ANAO’s review is conveyed in the Independent Assurance Report by the Auditor-General.

8. The following forecast information is excluded from the scope of the ANAO’s review:

- Section 1.2 Current Status—Materiel Capability Delivery Performance and Section 4.1 Measures of Materiel Capability Delivery Performance;

- Section 1.3 Project Context—Major Risks and Issues and Section 5 – Major Risks and Issues; and

- forecast dates where included in each PDSS.

- Accordingly, the Independent Assurance Report by the Auditor-General does not provide any assurance in relation to this information. However, material inconsistencies identified in relation to this information, are required to be considered in forming the conclusion.

9. The exclusions to the scope of the review noted above are due to a lack of Defence systems from which to provide complete and accurate evidence11, in a sufficiently timely manner to facilitate the review. This has been an area of focus of the JCPAA over a number of years12, and it is intended that all components of the PDSSs will eventually be included within the scope of the ANAO’s review.

10. Separate to the formal review, the ANAO has undertaken an analysis of key elements of the PDSSs — including cost, schedule, progress towards delivery of required capability, project maturity, and risks and issues. Longitudinal analysis across these key elements of projects has also been undertaken.

11. Defence provides further insights and context in its commentary and analysis. This commentary and analysis is not included within the scope of the ANAO’s review.

Review methodology

12. The ANAO has reviewed the PDSSs prepared by Defence as a priority assurance review under subsection 19A(5) of the Auditor-General Act 1997. The criteria to conduct the review are provided by the Guidelines approved by the JCPAA, and include whether Defence has procedures in place designed to ensure that project information and data was recorded in a complete and accurate manner, for all 26 projects.

13. The review included an assessment of Defence’s systems and controls, including the governance and oversight in place, to ensure appropriate project management. The ANAO also sought representations and confirmations from Defence senior management and industry in relation to the status of the Major Projects in this report.

Report structure

14. The report is organised into four parts:

- Part 1 comprises the ANAO’s review and analysis;

- Part 2 comprises Defence’s commentary, analysis and appendices (not included within the scope of the Independent Assurance Report by the Auditor-General);

- Part 3 incorporates the Independent Assurance Report by the Auditor-General, the Statement by the Secretary of Defence, and the PDSSs prepared by Defence as part of the assurance review process; and

- Part 4 reproduces the 2017–18 Major Projects Report Guidelines endorsed by the JCPAA, which provide the criteria for the compilation of the PDSSs by Defence and the ANAO’s review.

Figure 1, below, depicts the four parts of this report.

Figure 1: 2017–18 Report structure

Note: To assist in conducting inter-report analysis, the presentation of data in the PDSSs remains largely consistent and comparable with the 2016–17 MPR.

Project Data Summary Sheets

15. The PDSSs include unclassified information on project performance, prepared by Defence.13 As projects appear in the MPR for multiple years, changes to the PDSS from the previous year are depicted in bold orange text in the PDSS.

16. Each PDSS comprises:

- Project Header: including name; capability and acquisition type; Capability Manager; approval dates; total approved and in-year budgets; stage; complexity; and an image;

- Section 1—Project Summary: including description; current status including financial assurance and contingency statement; and context, including background, uniqueness, major risks and issues, and other current sub-projects;

- Section 2—Financial Performance: including budgets and expenditure; variances; and major contracts in place (in addition to quantities delivered as at 30 June 2018);

- Section 3—Schedule Performance: providing information on design development; test and evaluation; and forecasts and achievements against key project milestones, including Initial Materiel Release (IMR), Final Materiel Release (FMR)14, Initial Operational Capability (IOC) and Final Operational Capability (FOC)15;

- Section 4—Materiel Capability Delivery Performance: provides a summary of Defence’s assessment of its expected delivery of key capabilities, the extent to which milestones were achieved (particularly where caveats are placed on the Capability Manager’s declaration of significant milestones), and a description of the constitution of each key milestone;

- Section 5—Major Risks and Issues: outlines the major risks and issues of the project and remedial actions undertaken for each;

- Section 6—Project Maturity: provides a summary of the project’s maturity, as defined by Defence16, and a comparison against the benchmark score;

- Section 7—Lessons Learned: outlines the key lessons that have been learned at the project level (further information on lessons learned by Defence are included in Defence’s Appendix 2); and

- Section 8—Project Line Management: details current project management responsibilities within Defence.

Overall outcomes

Statement by the Secretary of Defence

17. The Statement by the Secretary of Defence was signed on 11 December 2018. The Secretary’s statement provides his opinion that the PDSSs for the 26 selected projects ‘comply in all material respects with the Guidelines and reflect the status of the projects as at 30 June 2018’.

18. In addition, the Statement by the Secretary of Defence details significant events occurring post 30 June 2018, which materially impact the projects included in the report, and which should be read in conjunction with the individual PDSSs. These include: Joint Strike Fighter, AWD Ships, P-8A Poseidon, Growler, Overlander Medium/Heavy, LHD Ships, Hawkei, Repl Replenishment Ships, Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) 2B, ANZAC ASMD 2A and 2B, Pacific Patrol Boat Repl, HATS, Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) 2A, Maritime Comms, Collins RCS, Hw Torpedo and LHD Landing Craft.

19. The 2017–18 MPR Guidelines require Defence to report in the Statement by the Secretary of Defence on projects which have been removed from the MPR which still have outstanding caveats. The status of the caveats of the ARH Tiger Helicopter Project, which achieved FOC in 2016 with caveats, has been reported in the Statement in Part 3 of this report.

Conclusion by the Auditor-General

20. The Auditor-General has concluded in the Independent Assurance Report for 2017–18 that ‘nothing has come to my attention that causes me to believe that the information in the 26 Project Data Summary Sheets in Part 3 (PDSSs) and the Statement by the Secretary of Defence, excluding the forecast information, has not been prepared in all material respects in accordance with the 2017–18 Major Projects Report Guidelines (the Guidelines), as endorsed by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit.’

21. Additionally, in 2017–18, a number of observations were made in the course of the ANAO’s review, as summarised below:

- non-compliance with corporate guidance resulting in inconsistent approaches taken to contingency allocation (Section 1 of the PDSS). See further explanation in paragraphs 1.34 to 1.41;

- a change to the basis of financial reporting (Section 2 of the PDSS). See further explanation in paragraphs 1.42 to 1.44;

- enhanced transparency by reporting cost variations since Second Pass Approval and personnel costs. See further explanation in paragraphs 1.45 to 1.49;

- a lack of oversight, non-compliance with corporate guidance and the use of spreadsheets in the management of risks and issues (Section 5 of the PDSS). See further explanation in paragraphs 1.50 to 1.5617;

- outdated policy guidance for the project maturity framework (Section 6 of the PDSS). See further explanation in paragraphs 1.57 to 1.6018; and

- a decrease in the number of MPR projects which have achieved significant milestones with caveats. See further explanation in paragraphs 1.61 to 1.62.

ANAO’s analysis of project performance

22. As discussed, the ANAO has undertaken an analysis of key elements of the Defence PDSSs — cost, schedule, progress towards delivery of required capability, project maturity, risks and issues, and longitudinal analysis across these key elements of projects. Table 2 provides: summary data on Defence’s progress toward delivering the capabilities for the Major Projects covered in this report; and compares current data against that reported in previous editions of the MPR. This section also contains a summary analysis of the three principal components of project performance: cost, schedule and capability.

Table 2: Summary longitudinal analysis1

|

|

2015–16 MPR |

2016–17 MPR |

2017–18 MPR |

|

Number of Projects |

26 |

27 |

26 |

|

Total Approved Budget |

$62.7 billion |

$62.0 billion |

$59.4 billion |

|

Total Expenditure Against Total Approved Budget |

$29.4 billion (46.9%) |

$32.1 billion (51.7%) |

$32.4 billion (54.5%) |

|

Total In-year Expenditure Against In-year Budget |

$3.9 billion (91.2%) |

$4.1 billion (96.6%) |

$4.6 billion (98.6%) |

|

Total Budget Variation since initial Second Pass Approval 2 |

$23.6 billion (37.6%) 3 |

$22.3 billion (36.0%) 3 |

$23.0 billion (38.7%) |

|

Total Budget Variation since final Second Pass Approval 4 |

$9.8 billion (15.7%) |

$8.5 billion (13.7%) |

$9.2 billion (15.5%) |

|

In-year Approved Budget Variation |

$4.9 billion (7.8%) |

-$1.6 billion (-2.6%) |

-$0.3 billion (-0.5%) |

|

Total Schedule Slippage 5 |

708 months (26%) |

793 months (29%) |

801 months (32%) |

|

Average Schedule Slippage per Project |

28 months |

30 months |

32 months |

|

In-year Schedule Slippage 6 |

42 months (1%) |

149 months (6%) |

104 months (5%) |

|

Total Project Maturity 7 |

1479 / 1820 (81%) |

1531 / 1890 (81%) |

1484 / 1820 (82%) |

|

Total Reported Risks and Issues 8, 9 |

123 |

136 |

138 |

|

Expected Capability (Defence Reporting) High level of confidence of delivery (Green) |

99% |

98% |

99% |

|

Under threat, considered manageable (Amber) |

1% |

2% |

1% |

|

Unlikely to be met (Red) |

0% 10 |

0% 10 |

0% |

Refer to paragraphs 22 to 36 in Part 1 of this report.

Note 1: The data for the 26 Major Projects in the 2017–18 MPR compares the data from projects in the 2016–17 MPR and 2015–16 MPR. The Major Projects included within each MPR are based on entry and exit criteria in the Guidelines, which have been included in Part 4 of this report. The entry and exit of projects should be considered when comparing data across years.

Note 2: Where a project has multiple Second Pass Approvals, the MPR has historically reported budget variations from the initial Second Pass Approval. The figures in this row are consistent with prior year reporting. See Table 3 for a breakdown of the major components of this variance.

Note 3: These figures include a $0.8 billion correction to an error in prior year data.

Note 4: In the 2017–18 PDSSs, where a project has multiple Second Pass Approvals, the budget at Second Pass Approval reported in the Header refers to the total budget as at the final Second Pass Approval. The figures in this row use this methodology.

Note 5: Slippage refers to the difference between the original government approved date and the current forecast date. Slippage can occur due to late delivery, increases in scope or at times can be a deliberate management decision. These figures exclude schedule reductions over the life of the project. However, Figure 10 reports in-year schedule reductions.

Note 6: Based on the 23 repeat projects from the 2014–15 MPR, 25 repeat projects from the 2015–16 MPR plus one new project (CMATS) that had slippage in 2016–17, and 23 repeat projects from the 2016–17 MPR respectively.

Note 7: The figures represent the total of the reported maturity scores divided by the total benchmark maturity score, in the PDSSs across all projects.

Note 8: The figures represent the combined number of open high and extreme risks and issues reported in the PDSSs across all projects. Risks and issues may be aggregated at a strategic level.

Note 9: The grey section of the table is excluded from the scope of the ANAO’s priority assurance review, due to a lack of systems from which to obtain complete and accurate evidence in a sufficiently timely manner to facilitate the review.

Note 10: Defence advised in these years that Joint Strike Fighter would not deliver one element of capability at FOC (which equated to approximately one per cent). However, across all the Major Projects this percentage rounded to zero per cent.

Cost

23. Cost management is an ongoing process in Defence’s administration of the Major Projects. While all projects reported that they could continue to operate within the total approved budget of $59.4 billion, CMATS was granted a Real Cost Increase of $240.7 million by government in February 2018.19,20 In addition, MRH90 Helicopters, Battle Comm. Sys (Land) 2B, UHF SATCOM and BMS have been required to draw upon contingency funds to complete project activities.

24. The approved budget for Major Projects included in this MPR has increased by $23.0 billion (38.7 per cent) since initial Second Pass Approval. Budget variations greater than $500 million are detailed in Table 3, below. However, as the MPR predominantly focusses on the approved capital budget, the ongoing costs of Project Offices21 (acquisition), training, replacement capability, etc., are not reported here.

Table 3: Budget variation over $500m post initial Second Pass Approval by variation type 1, 2

|

Project |

Variation |

Explanation |

Year |

Amount $b |

|

|

|

Scope Increases |

|

|

|

14.1 |

|

MRH90 Helicopters |

|

34 additional aircraft at Phase 4/6 Second Pass Approval |

2005–06 |

2.3 |

|

|

Joint Strike Fighter |

|

58 additional aircraft at Stage 2 Second Pass Approval |

2013–14 |

10.5 |

|

|

P-8A Poseidon |

|

Four additional aircraft |

2015–16 |

1.3 |

|

|

|

Real Cost and other Increases |

|

|

|

1.8 |

|

AWD Ships |

|

Real Cost Increase of $1.2b offset by $0.1b transfer for facilities in 2014 |

2013–14 and 2015–16 |

1.1 |

|

|

Overlander Medium/Heavy |

|

Project supplementation ($684.2m) and additional vehicles, trailers and equipment ($28.0m) at Revised Second Pass Approval |

2013–14 |

0.7 |

|

|

|

Other budget movements |

|

|

|

1.1 |

|

Other |

Scope increase/budget transfers (net) |

Other scope changes and transfers |

Various |

1.1 |

|

|

|

Price Indexation – materials and labour (net) (to July 2010) 3 |

|

3.0 |

||

|

Exchange Variation – foreign exchange (net) (to 30 June 2018) |

|

3.0 |

|||

|

|

Total |

|

|

|

23.0 |

Note 1: For the variations related to all projects and values refer to Table 8 of this report. For the breakdown of in-year variation, refer to Table 9 of this report.

Note 2: For projects with multiple Second Pass Approvals, this table shows variations from the initial approval.

Note 3: Prior to 1 July 2010, projects were periodically supplemented for price indexation, whereas the allocation for price indexation is now provided for on an out-turned basis at Second Pass Approval.

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2017–18 PDSSs.

Schedule

25. Delivering Major Projects on schedule continues to present challenges for Defence22; affecting when the capability is made available for operational release and deployment by the Australian Defence Force, as well as the cost of delivery.

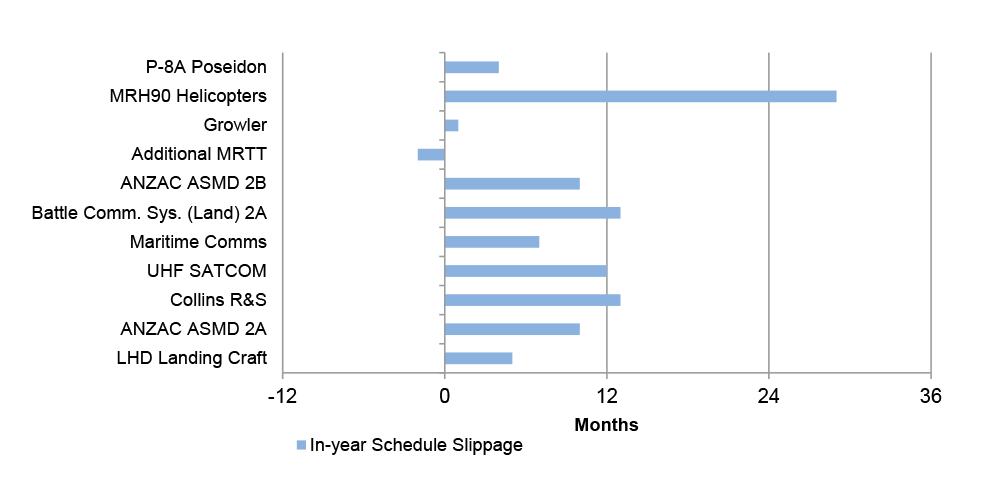

26. The total schedule slippage for the 26 selected Major Projects, as at 30 June 2018, is 801 months (2016–17: 793 months) when compared to the initial schedule.23 This represents a 32 per cent (2016–17: 29 per cent) increase since Second Pass Approval. Table 4 below includes details of in-year and total schedule slippage by project. While the table shows a five per cent in-year slippage for 2017–18, the removal of completed projects (ARH Tiger Helicopters, Bushmaster Vehicles, Overlander Light, and Additional Chinook) has removed 98 months of slippage. The effect of these projects exiting the review explains the difference between the total schedule slippage in 2017–18 (8 months) and the total in-year slippage amount (104 months). Additionally, the Pacific Patrol Boat Replacement project added two months of slippage to the total of 801 months; the slippage occurred in 2015–16 but the project was reported in the MPR for the first time in 2017–18.

Table 4: Schedule slippage from original planned Final Operational Capability 1

|

Project |

In-year (months) |

Total (months) |

|

Joint Strike Fighter 3 |

0 |

2 |

|

AWD Ships |

0 |

35 |

|

P-8A Poseidon |

4 |

28 |

|

MRH90 Helicopters |

29 |

89 |

|

Growler |

1 |

1 |

|

MH-60R Seahawk |

0 |

0 |

|

Overlander Medium/Heavy |

0 |

5 |

|

LHD Ships 3 |

0 |

37 |

|

Hawkei |

0 |

0 |

|

Battlefield Airlifter |

0 |

24 |

|

Repl Replenishment Ships |

0 |

0 |

|

CMATS 3 |

0 |

28 |

|

Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) 2B |

0 |

0 |

|

Additional MRTT |

0 |

21 |

|

ANZAC ASMD 2B |

10 |

67 |

|

Pacific Patrol Boat Repl |

0 |

2 |

|

HATS |

0 |

0 |

|

Collins RCS |

0 |

109 |

|

Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) 2A |

13 |

30 |

|

Maritime Comms |

7 |

7 |

|

Hw Torpedo |

0 |

63 |

|

UHF SATCOM 3 |

12 |

21 |

|

Collins R&S |

13 |

112 |

|

ANZAC ASMD 2A |

10 |

82 |

|

BMS 2 |

N/A |

N/A |

|

LHD Landing Craft 4 |

5 |

38 |

|

Total (months) |

104 |

801 |

|

Total (%) |

5 |

32 |

Note 1: Refer to footnote 23.

Note 2: BMS does not have IOC or FOC milestones. These were to be linked to Work Packages B-D which received government approval in September 2017 under LAND 200. Work Package A achieved FMR in December 2017. MAA closure did not occur in October 2018 as forecast.

Note 3: These projects have been identified by Defence as Projects of Interest (see paragraph 1.17 in Part 1).

Note 4: The LHD Landing Craft PDSS shows an FOC forecast of ‘TBA’ (See the PDSS in Part 3 of this report). For the purposes of slippage analysis in this report, the ANAO has reflected the slippage that had occurred for the project at the time of this report. The Statement by the Secretary of Defence in Part 3 of this report notes that since 30 June 2018, FOC for this project has been rescheduled for the second half of 2019.

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2017–18 PDSSs.

27. Platform availability has contributed to the slippage experienced within some projects. For example, the submarine programs have been impacted by changes to docking schedules, following government commissioned reviews. Significant delays have also been experienced by those projects with the most developmental content: AWD Ships, MRH90 Helicopters, CMATS and ANZAC ASMD 2B. Additionally, delays to operational test and evaluation activities have led to delays to the LHD Ships and LHD Landing Craft projects.

28. Table 5, below, provides details of total schedule slippage by project, for projects that have exited the MPR. Compared to the 801 months total schedule slippage for the current 26 Major Projects, the 18 projects which have exited the MPR have reported accumulated schedule slippage of 699 months, as at their respective exit dates. Again, schedule slippage was more pronounced in projects with the most developmental content.

Table 5: Schedule slippage for projects which have exited the MPR

|

Project |

Total (months) |

|

Wedgetail (Developmental) |

78 |

|

Super Hornet (MOTS) |

0 |

|

Hornet Upgrade (Australianised MOTS) |

39 |

|

ARH Tiger Helicopters (Australianised MOTS) |

82 |

|

C-17 Heavy Airlift (MOTS) |

0 |

|

Air to Air Refuel (Developmental) |

64 |

|

FFG Upgrade (Developmental) |

132 |

|

Bushmaster Vehicles (Australianised MOTS) |

1 |

|

Overlander Light (Australianised MOTS) |

9 |

|

Next Gen Satellite 1 (MOTS) |

0 |

|

Additional Chinook |

6 |

|

HF Modernisation (Developmental) |

147 |

|

Armidales (Australianised MOTS) |

45 |

|

SM-2 Missile (Australianised MOTS) |

26 |

|

155mm Howitzer (MOTS) |

7 |

|

Stand Off Weapon (Australianised MOTS) |

37 |

|

Battle Comm. Sys. (Australianised MOTS) |

24 |

|

C-RAM (MOTS) |

2 |

|

Next Gen Satellite 1 (MOTS) |

0 |

|

Additional Chinook |

6 |

|

HF Modernisation (Developmental) |

147 |

|

Armidales (Australianised MOTS) |

45 |

|

SM-2 Missile (Australianised MOTS) |

26 |

|

155mm Howitzer (MOTS) |

7 |

|

Stand Off Weapon (Australianised MOTS) |

37 |

|

Battle Comm. Sys. (Australianised MOTS) |

24 |

|

C-RAM (MOTS) |

2 |

|

Total |

699 |

Note 1: Next Gen Satellite shows slippage in Figure 8, which related to the final capability milestones at the time. By the time it reached FOC, a new final capability milestone had been introduced and slippage was reduced.

Source: PDSSs in published Major Projects Reports and ANAO analysis.

29. Additional ANAO analysis (refer to Figure 7) has compared project slippage against the Defence classification of projects as Military Off-The-Shelf (MOTS), Australianised MOTS or developmental.24 These classifications are a general indicator of the difficulty associated with the procurement process. This analysis highlights, prima facie, that the more developmental in nature a project is, the more likely it will result in a greater degree of project slippage, as well as demonstrating one of the advantages of selecting MOTS acquisitions.25

30. Figure 8 provides analysis of projects either completed, or removed from the MPR review, and shows that a focus on MOTS acquisitions has assisted in reducing schedule slippage. Figure 8 was requested by the JCPAA in May 2014.26

31. Longitudinal analysis indicates that while the reasons for schedule slippage vary, it primarily reflects the underestimation of both the scope and complexity of work, particularly for Australianised MOTS and developmental projects (see paragraphs 2.29 to 2.33).

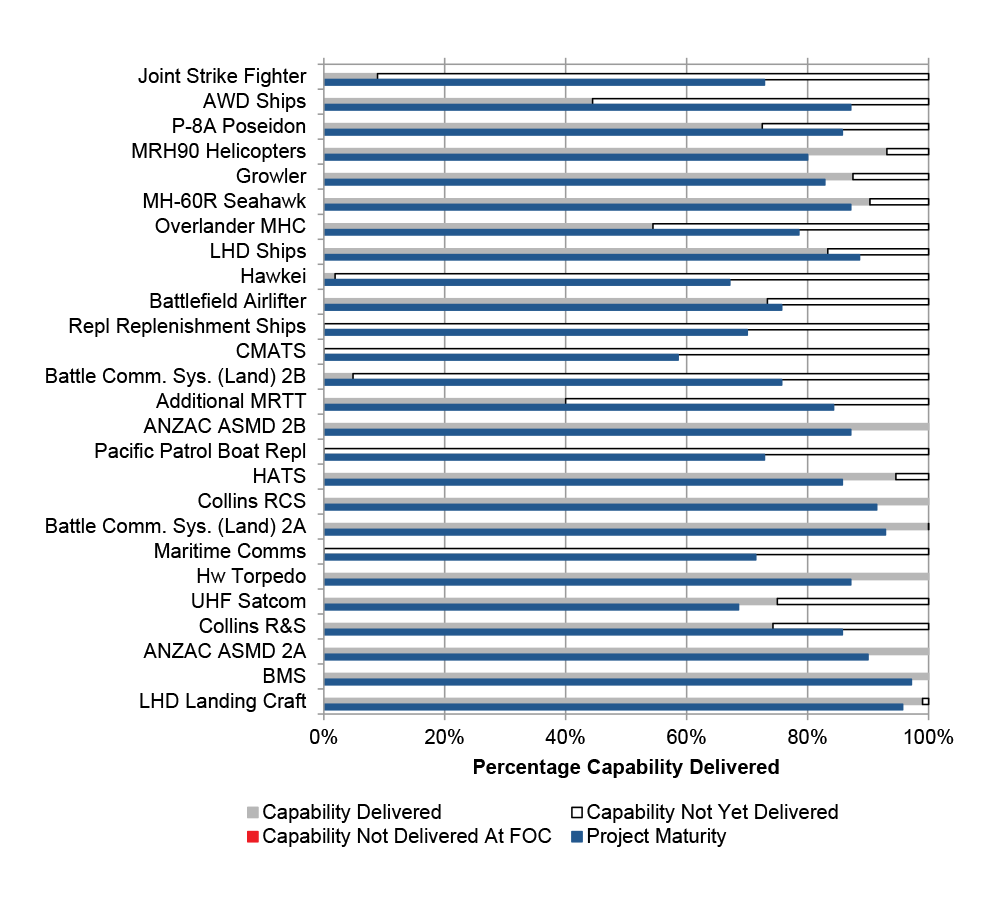

Capability

32. The third principal component of project performance examined in this report is progress towards the delivery of capability required by government. While the assessment of expected capability delivery by Defence is outside the scope of the Auditor-General’s formal review conclusion, it is included in the analysis to provide an overall perspective of the three principal components of project performance.

33. The Defence PDSSs report that 23 projects in this year’s report will deliver all of their key capability requirements. Defence’s assessment indicates that some elements of the capability required may be ‘under threat’, but the risk is assessed as ‘manageable’. The three project offices experiencing challenges with expected capability delivery (2016–17: three) are Joint Strike Fighter, MRH90 Helicopters, and LHD Landing Craft. No project offices report that they are currently unable to deliver all of the required capability by FOC.

34. Defence’s presentation of capability delivery performance in the PDSSs is a forecast and therefore has an element of uncertainty. In 2015–16, the ANAO developed an additional measure of the status of current capability delivery progress to assist the Parliament — Capability Delivery Progress — which is a tally of the capability delivered as at 30 June 2018, as reported by Defence. Table 6 below provides a worked example of the ANAO’s methodology, utilising the performance information provided in the relevant PDSS.

Table 6: Capability Delivery Progress assessment — Additional MRTT (multi-role tanker transport)

|

Capability elements as per Section 4.2 of the PDSS |

No. of elements approved |

No. of elements delivered at 30 June 2018 |

Comments |

|

Delivery of first aircraft, and delivery of initial spares and support equipment (IMR) |

2 |

2 |

First aircraft and initial spares delivery completed. |

|

Delivery of second aircraft, delivery of remaining spares and support equipment, and delivery of Aircraft Stores Replenishment Vehicle (FMR) |

3 |

0 |

Second aircraft, remaining spares and support equipment, and Aircraft Stores Replenishment Vehicle are yet to be delivered. |

|

Total (number) |

5 |

2 |

— |

|

Total (%) |

100 |

40 |

— |

Source: PDSSs in published Major Projects Reports and ANAO analysis.

35. Table 7 below, summarises expected capability delivery as at 30 June 2018 — as reported by Defence and using the ANAO’s Capability Delivery Progress measure.

Table 7: Capability delivery

|

Expected Capability |

2015–16 MPR (%) |

2016–17 MPR (%) |

2017–18 MPR (%) |

Capability Delivery Progress |

2017–18 MPR (%) |

2017–18 MPR (%) Adjusted 2 |

|

High Confidence (Green) |

99 |

98 |

99 |

Delivered |

72 |

61 |

|

Under Threat, considered manageable (Amber) |

1 |

2 |

1 |

Not yet delivered |

28 |

39 |

|

Unlikely (Red) |

0 1 |

0 1 |

0 |

Not delivered at FOC |

0 |

0 |

|

Total |

100 |

100 |

100 |

Total |

100 |

100 |

Note 1: Defence advised that in these years Joint Strike Fighter would not deliver one element of capability at FOC, of a total of 79 elements required for the project (which equated to approximately one per cent). However, across all the Major Projects this percentage rounds to zero.

Note 2: In prior years, ANAO adjusted for projects that disproportionately weighted the calculation of Capability Delivery Progress (those projects with large numbers of deliverables) by excluding them from the analysis. In 2017–18, the ANAO has used a different adjustment method. While the left-hand column reports the total percentage of elements delivered across all 26 Major Projects, the right-hand adjusted column reports the average percentage of elements delivered per project. This adjustment results in an analysis where all projects have equal weight and the percentage is not affected by the numbers of deliverables per project.

Source: PDSSs in published Major Projects Reports and ANAO analysis.

36. In addition to reporting on expected capability delivery, Defence has continued the practice of including declassified information on settlement actions for projects. Prior settlements for projects within this report related to MRH90 Helicopters, LHD Ships and Maritime Comms.

1. The Major Projects Review

1.1 This chapter provides an overview of the review’s scope and approach, as implemented by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO), for the review of the 26 Project Data Summary Sheets (PDSSs) prepared by the Department of Defence (Defence). This chapter also provides the results of the Major Projects Report (MPR) review.

Review scope and approach

1.2 In 2012 the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) identified the review of the PDSSs as a priority assurance review, under subsection 19A(5) of the Auditor-General Act 1997 (the Act). This provided the ANAO with full access to the information gathering powers under the Act. The ANAO’s review of the individual project PDSSs, which are reproduced in Part 3 of this report, was conducted in accordance with the auditing standards set by the Auditor-General under section 24 of the Auditor-General Act 1997 through its incorporation of the Australian Standard on Assurance Engagements (ASAE) 3000 Assurance Engagements Other than Audits or Reviews of Historical Financial Information, issued by the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards Board.

1.3 The following forecast information is excluded from the scope of the ANAO’s review: capability delivery, risks and issues, and forecast dates. These exclusions are due to the lack of Defence systems from which to provide complete and accurate evidence27, in a sufficiently timely manner to complete the review. Accordingly, the Independent Assurance Report by the Auditor-General does not provide any assurance in relation to this information. However, material inconsistencies identified in relation to this information, are required to be considered in forming the conclusion.

1.4 The ANAO’s work is appropriate for the purpose of providing an Independent Assurance Report in accordance with the above auditing standard. However, the review of individual PDSSs is not as extensive as individual performance and financial statement audits conducted by the ANAO, in terms of the nature and scope of issues covered, and the extent to which evidence is required by the ANAO. Consequently, the level of assurance provided by this review, in relation to the 26 major Defence equipment acquisition projects (Major Projects), is less than that provided by the ANAO’s program of audits.

1.5 Separately, the ANAO undertakes analysis of key elements of the PDSSs and examines systemic issues and provides longitudinal analysis for the 26 projects reviewed.

1.6 The review was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $2.1 million.

Review methodology

1.7 The ANAO’s review of the information presented in the individual PDSSs included:

- examination and assessment of the governance and oversight in place to ensure appropriate project management;

- an assessment of the systems and controls that support project financial management, risk management, and project status reporting, within Defence;

- an examination of each PDSS and the documents and information relevant to them;

- a review of relevant processes and procedures used by Defence in the preparation of the PDSSs;

- interviews with persons responsible for the preparation of the PDSSs and management of the projects;

- analysis of project information, for example, cost and schedule variances;

- taking account of industry contractor comments provided on draft PDSS information;

- assessing the assurance by Defence managers attesting to the accuracy and completeness of the PDSSs;

- examination of the representations by the Chief Finance Officer supporting the project financial assurance and contingency statements;

- examination of confirmations, provided by the Capability Managers, relating to each project’s progress toward Initial Materiel Release (IMR), Final Materiel Release (FMR), Initial Operational Capability (IOC) and Final Operational Capability (FOC); and

- examination of the ‘Statement by the Secretary of Defence’, including significant events occurring post 30 June, and management representations by the Secretary of Defence.

1.8 The ANAO’s review of PDSSs also focused on project management and reporting arrangements contributing to the overall governance of the Major Projects. The ANAO considered:

- resolution of matters described in the Auditor-General’s prior year (2016–17) qualified Independent Assurance Report, relating to the ARH Tiger Helicopter PDSS28;

- developments in acquisition governance (See paragraphs 1.10 to 1.25, below);

- the financial framework, particularly as it applies to the project financial assurance and contingency statements, and Defence’s advice that project financial reporting during 2017–18 would be prepared on the same basis as project approvals and expenditure represented in the Portfolio Budget Statements and the Defence Annual Report (i.e. on a cash basis) (Section 2 of the PDSSs);

- schedule management and test and evaluation processes (Section 3 of the PDSSs);

- capability assessments, including Defence statements of the likelihood of delivering key capabilities, particularly where caveats are placed on the Capability Manager’s declaration of significant milestones (Section 4 of the PDSSs);

- the ongoing reform process for the Enterprise Risk Management Framework, and the completeness and accuracy of major risk and issue data (Section 5 of the PDSSs);

- the project maturity framework along with its related reporting and the systems in place to support the consistent and accurate application and the provision of this data (Section 6 of the PDSSs); and

- the impact of acquisition issues on sustainment to ensure the PDSS is a complete and accurate representation of the acquisition project.

1.9 This review informed the ANAO’s understanding of the systems and processes supporting the PDSSs for the 2017–18 review period. It also highlighted issues in those systems and processes that warrant attention.

Acquisition governance

1.10 Consistent with previous years, the context of acquisition governance processes are covered in the ANAO’s review and informs the review planning process. While some of these processes are now established, others continue to mature or require further development to achieve their intended impact.

Defence Independent Assurance Reviews

1.11 The Defence Independent Assurance Review process provides the Defence Senior Executive with assurance that projects and products will deliver approved objectives and are prepared to progress to the next stage of activity. Reviews allow early identification of problem projects and products, facilitating their timely recovery.29,30

1.12 Formerly called Gate Reviews, Independent Assurance Reviews are intended to be conducted at key acquisition and sustainment ‘gates’ in the Capability Life Cycle.31

1.13 Seventeen of the 26 projects included in this report had an Independent Assurance Review conducted during 2017–1832, which formed key corroborative evidence for the ANAO’s review.

Projects of Concern

1.14 The Projects of Concern process is intended to focus the attention of the highest levels of government, Defence and industry on remediating problem projects. The process has continued to play a role across the portfolio of MPR projects.33,34 As at 30 June 2018, one MPR project, MRH90 Helicopters was a continuing project of concern. The project was placed on the list in November 2011 due to contractor performance relating to significant technical issues preventing the achievement of milestones on schedule.35

1.15 In August 2017, the Ministers for Defence and Defence Industry announced36 that the Civil Military Air Traffic Management System (CMATS) project was being placed on the list due to substantial challenges getting into contract.37,38 The Ministers for Defence and Defence Industry subsequently announced in February 201839 that the project would be removed from the Projects of Concern list due to having achieved this milestone.40

Quarterly Performance Report

1.16 The Quarterly Performance Report (QPR) aims to provide senior stakeholders within government and Defence with a clear and timely understanding of emerging risks and issues in the delivery of capability to the Australian Defence Force’s end-users.41 Defence has advised that the report is provided to the Minister for Defence and the Minister for Defence Industry on a quarterly basis.42

1.17 In 2017–18, further to the MRH90 Helicopters MPR project of concern noted above, the June 2018 QPR also identified four MPR projects as Projects of Interest43:

- Joint Strike Fighter, noting risks related to affordability, IOC and FOC deliverables, with consideration being given to de-scoping the project to address these risks;

- Civil Military Air Traffic Management System (CMATS), noting risks to schedule due to execution of design milestones and poor scope definition, planning and dedicated resources attributed to the Four Alternate Tower Solution;

- LHD Ships due to the late delivery of ships, a large number of outstanding requirements, defects and deficiencies, and an immature support system; and

- UHF SATCOM, due to issues with the modification of Commercial Off-The-Shelf software (an element of the project now considered developmental) and delays in the security accreditation process.

1.18 The ongoing issues highlighted above for Joint Strike Fighter, LHD Ships, CMATS, and UHF SATCOM align with the results of the ANAO’s review. Delays to progress have impacted the delivery schedule of UHF SATCOM during 2017-1844 (see Table 4).

Joint Project Directives and Materiel Acquisition Agreements

1.19 Joint Project Directives (JPDs) state the terms of government approval and are used to inform internal documentation such as Materiel Acquisition Agreements (MAAs) between Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG) and the Service Chiefs.45,46

1.20 In some cases JPDs have been finalised after the MAAs they are intended to inform and, as a result, care is required to ensure that JPDs properly reflect the relevant government decision, and that MAAs are appropriately aligned with the relevant JPD. For all three new projects entering the 2017–18 MPR, the projects had their JPD signed prior to the MAA which demonstrates improvement in this regard.

1.21 In 2017–18, 16 of the 17 MPR projects approved from 1 March 2010, have completed a JPD.47 However, the ANAO requires access to original approval documents to validate the requirements of projects. At this time, validation based on internal Defence documentation is not always possible.

1.22 The ANAO will continue to take JPDs into account in its review program in future years. The extent to which they can be relied upon will be dependent on the completeness and accuracy of JPDs, in relation to recording the detail of government approvals.

1.23 Product Delivery Agreements (PDAs) were being developed to replace the existing MAAs and Materiel Sustainment Agreements (MSAs)48, however Defence has since advised that this initiative has not progressed.

Business systems

1.24 Defence continues to review its business systems with the aim of consolidating processes and systems in order to provide a more manageable system environment.49 During 2018–19, and at the time of this report, the Monthly Reporting System (MRS), which provides much of the data for the PDSSs, remains in place although replacement of this system is still under consideration. As reported to the JCPAA on 31 March 2017, Defence stated that there was a ‘need to get a single unified system of accountability and reporting inside the organisation’.

1.25 In October 2018, Defence advised that it had concluded its trial of the Project Performance Review in November 2017. The PPR is a spreadsheet with project performance information intended to be used by project managers to inform discussions with Project Directors and Branch Heads. In January 2018 Defence initiated a plan to implement the PPRs across CASG. Defence has advised that seven MPR projects are currently preparing a PPR in Microsoft Excel form.50 Defence planned to then implement a streamlined ICT system to 31 projects commencing in November 2018. Defence has advised that it now expects this implementation to commence in December 2018, however it is not clear whether this will take the form of spreadsheets or a bespoke ICT system.

Results of the review

1.26 The following sections outline the results of the ANAO’s review, which inform the overall conclusion in the Independent Assurance Report by the Auditor-General for 2017–18.

Financial framework

1.27 The project financial assurance statements were introduced in the 2011–12 Major Projects Report and have been included within the scope of the Independent Assurance Report by the Auditor-General since 2014–15. The contingency statements were introduced for the first time in the 2013–14 report and these describe the use of contingency funding to mitigate project risks. Together, they are aimed at providing greater transparency over projects’ financial status.

1.28 A project’s total approved budget comprises:

- the allocated budget, which covers the project’s approved activities, as indicated in the MAA; and

- the contingency budget, which is set aside for the eventuality of risks occurring and includes unforeseen work that arises within the delivery of the planned scope of work.51

1.29 In 2017–18, the ANAO reviewed the financial framework as it applied to managing project budgets and expenditure, including: contingency, project financial assurance, the reporting environment, and reporting cost variations and personnel costs.

Project financial assurance statement

1.30 The project financial assurance statement was added to the PDSSs to enhance transparency by providing readers with information on each project’s financial position (in relation to delivering project capability) and whether there is ‘sufficient remaining budget for the project to be completed’.52 Defence advised on 27 October 2017 that the administrative policy supporting this statement was ‘no longer current as it is an artefact of the previous DMO agency’. Defence then advised in January 2018 that there is no Defence policy in place supporting the current administrative practice, but that the previously used policy would represent ‘good practice’.

1.31 In 2017–18 the CMATS project was granted a significant Real Cost Increase of $240.7 million by government in February 201853 which has enabled the project to state that ‘there is sufficient budget remaining for the project to complete against the agreed scope’, which had not been possible in the previous MPR.54

1.32 Unlike in previous years, Defence advised in January 2018 that it would no longer subject a sample of project financial assurance statements to a third-party agreed-upon procedures engagement to support the Chief Finance Officer in determining the appropriateness of the statements. The ANAO agreed with this approach which was endorsed by the JCPAA in the 2017–18 MPR Guidelines.

1.33 In conclusion, for the 2017–18 Major Projects Report, the Chief Finance Officer’s representation letter to the Secretary on the project financial assurance statements was unqualified. The project financial assurance statement is restricted to the current financial contractual obligations of Defence for these projects, including the result of settlement actions and the receipt of any liquidated damages, and current known risks and estimated future expenditure as at 30 June 2018.

Contingency statements and contingency management

1.34 The purpose of the project contingency budget is ‘to provide adequate budget to cover the inherent risk of the in-scope work of the project’.55 Defence policy requires project offices to maintain a contingency budget log to identify and track components of the contingency budget.56

1.35 PDSSs are required to include a statement regarding the application of contingency funds during the year, if applicable, as well as disclosing the risks mitigated by the application of those contingency funds. Defence’s Project Risk Management Manual (PRMM version 2.4, page 110) requires that contingency be applied for identified risk mitigation activities which have been assessed as being cost effective and representing value for money.

1.36 Contingency provisions for projects are not programmed into a project’s cash budget. As such, projects are encouraged to rely on cash budget management and savings to mitigate risks. Where this is not sufficient, projects can submit a request to Defence Finance Group to access contingency. If this cannot be managed within the Approved Major Capital Investment Program cash budget, consideration by the Defence Investment Committee is sought on how best to manage the call within the overall Integrated Investment Program.

1.37 A Defence internal audit, finalised in August 2018, concluded that Defence has been able to fund contingency calls through internal project or program management decisions and project slippage.57 The advent of large scale, high cost and high risk projects has created an environment whereby Defence Senior Executives consulted by the internal audit team expressed concern that it may become more difficult for Defence to redistribute cash funding to manage contingency events without compromising either the timeliness or level of capability delivered.58

1.38 The ANZAC ASMD 2B project PDSS59 notes that access to contingency funding to remediate unplanned obsolescence issues was denied during Defence budget processes.60

1.39 The four project offices which had contingency funds applied in 2017–18 were MRH90 Helicopters (supportability and performance risks), Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) 2B (Interface Control Integration), UHF SATCOM (software review and system security) and BMS (Risk Reduction Activities related relating to the M1A1 Tank Weapons Integrated Battle Management System).

1.40 The ANAO’s examination of the contingency statements as at 30 June 2018 also highlighted that:

- the clarity of the relationship between contingency application and identified risks continues to be an issue. Of the 25 project offices that have a formal contingency allocation61, seven projects (Joint Strike Fighter, Overlander Medium/Heavy, Repl Replenishment Ships, Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) 2B, CMATS, Pacific Patrol Boat Repl and BMS) did not explicitly align their contingency log with their risk log, by including risk identification numbers as required by PRMM version 2.4;

- the method for allocating contingency varied, with 22 project offices using the ‘expected costs’ of the risk treatment (as required by PRMM version 2.4), with Pacific Patrol Boat Repl and Repl Replenishment Ships having not yet allocated contingency against risks. The Overlander Medium/Heavy project used the proportionate allocation of the likelihood of the risk eventuating (the method outlined in PRMM version 2.2); and Collins R&S does not have a formal contingency allocation;

- there were 16 project offices that did not meet all the requirements of PRMM version 2.4 in terms of keeping a record of review of contingency logs, however, the ANAO observed that the information required could be located in other documents.

1.41 Non-compliance with PRMM version 2.4 has resulted in inconsistent approaches taken to the management of contingency, with some projects advising that they will not remedy these non-compliances until the outcomes of the risk management reform within CASG are known (see paragraph 1.53).

Reporting environment

1.42 On April 4 2018, following a submission to the JCPAA hearing held on 23 March 2018, Defence advised project offices that project financial reporting for 2017–18 PDSSs would be prepared on the same basis as project approvals and expenditure represented in the Portfolio Budget Statements and the Defence Annual Report (i.e. on a cash basis). Therefore actual expenditure in the PDSSs may not be consistent with that reported in previous MPRs which had been prepared on an accrual basis. ANAO analysis of the overall variance showed that the difference was approximately 1.5 per cent between accrual and cash expenditure in the 2016–17 MPR.62

1.43 Defence obtains cash expenditure data using a management reporting tool called BORIS. In previous MPRs, accrual expenditure data was extracted from the Financial Management Information System known as ROMAN. Given the change in the extraction method, the ANAO requested evidence from Defence to support that the outputs of the BORIS tool were complete and accurate at the project level.

1.44 Defence was unable to provide sufficient evidence to support this position at the project level, so the ANAO requested that Defence conduct a reconciliation of all cash expenditure data from BORIS to the ROMAN Financial Management Information System which holds the transaction data. This activity concluded in early November 2018 and enabled assurance over the cash expenditure to be obtained by the ANAO.

Reporting cost variations since Second Pass Approval and personnel costs

1.45 In May 2018, the JCPAA wrote to the Auditor-General to request that the ANAO report back to it on how Defence Major Projects cost variations and the cost of retaining project staff might be reported annually in future MPRs.63 The JCPAA further asked the Auditor-General to consider presenting any relevant available data in the 2017–18 MPR.

1.46 The JCPAA indicated that it would consider whether inclusion of such information adds value to the MPR, with a view to amending the associated guidelines for future MPRs if the information proved to be useful in increasing oversight of expenditure.

1.47 In consultation with Defence, the PDSSs in this report have been amended to include the project budget at Second Pass Approval64 in addition to the project’s current approved budget to show any variations between them. In September 2018, the JCPAA endorsed the 2018–19 MPR Guidelines which require that this information is provided in future MPRs.65

1.48 A table of all budget variations post initial Second Pass Approval for the projects is also provided at Table 8.

1.49 The reporting of the costs of project staff has proven to be more challenging. Defence advised the ANAO in November 2018 that its current IT systems do not provide a direct mapping of personnel to projects, with personnel often working on multiple projects and sustainment activities at any given time. Defence has advised the ANAO that while it is not yet in a position to provide the staff cost component of projects, it has begun to collect information on the numbers of staff (including Australian Defence Force and Australian Public Service, but not contractors) for projects.66 Further information on staff numbers will be reported in the 2018–19 MPR.

Enterprise Risk Management Framework

1.50 While major risks and issues data in the PDSSs remains excluded from the formal scope of the Auditor-General’s Independent Assurance Report67, material inconsistencies identified in relation to this information are required to be detailed in the report. The following information is included to provide an overall perspective of how risks and issues are managed within Defence and the selected Major Projects.

1.51 Risk management has been a focus of the MPR since its inception. The CASG risk management environment consists of multiple policies and varying implementation mechanisms and documentation. There are multiple group-level (i.e. CASG), sub-group (i.e. Divisional) and project-level risk management documents. The primary focus of the ANAO’s examination of risk management is at the project level, in order to provide assurance over the PDSSs.

1.52 At the Group level, Deputy Secretary CASG issued a directive in May 2017 establishing a CASG Risk Management Reform Program to implement a risk management model that is situated within Defence’s risk management framework. CASG is part way through the reform initially intended to be completed by June 2019, with Defence advising that completion is now expected to occur by the end of 2019, and then taking a number of annual cycles to reach maturity.68

1.53 The next stage of the reform will provide project specific guidance and tools to support risk management practices of projects. The ANAO has observed that some projects chose not to review risk and issues management procedures until this stage has completed, as noted at paragraph 1.41. The ANAO will continue to monitor the implementation of the reform as part of future reviews, but will not be able to consider including risks and issues in the scope of the MPR until the reform is sufficiently progressed.

1.54 In 2017–18, the ANAO again examined project offices’ risk and issue logs at the Group and Service level, which are predominantly created and maintained utilising spreadsheets and/or Predict! software.69 Overall, the issues with risk management that the ANAO observed related to:

- variable compliance with corporate guidance, for example all projects had a Risk Management Plan, however; 11 out of 26 Major Projects did not validate the currency of the Risk Management Plan in line with PRMM version 2.470;

- the visibility of risks and issues when a project is transitioning to sustainment;

- for four projects (JSF, HATS, Collins RCS and Hw Torpedo), sustainment and acquisition risks are managed together, despite Defence risk management policy for acquisition and sustainment providing inconsistent guidance71;

- one project (Repl Replenishment Ships) early-adopted draft guidance from Defence intended to be used to prompt discussion as part of the CASG risk reform, only to be advised by the Defence Enterprise Risk Management Branch that this was not compliant with current Defence acquisition risk management guidance;

- the frequency with which risk and issue logs are reviewed to ensure risks and issues are appropriately managed in a timely manner, and accurately reported to senior management;

- risk management logs and supporting documentation of variable quality, particularly where spreadsheets are being used72; and

- lack of quality control resulting in inconsistent approached in the recording of issues within Predict!

1.55 The ANAO has previously observed that Defence’s use of spreadsheets as a primary form of record for risk management is a high risk approach. Spreadsheets lack formalised change/version control and reporting, thereby increasing the risk of error. This can make spreadsheets unreliable corporate data handling tools as accidental or deliberate changes can be made to formulae and data, without there being a record of when, by whom, and what change was made. As a result, a significant amount of quality assurance is necessary to obtain confidence that spreadsheets are complete and accurate at 30 June, which is not an efficient approach. The ANAO’s review of CASG’s 26 project offices indicates that 13 utilise spreadsheets73 as their primary risk management tool, seven utilise Predict!74, one (LHD Ships) utilises both Microsoft Excel and Predict!, two (JSF and CMATS) utilise a bespoke SharePoint based tool, one (MH-60R Seahawk) utilises Microsoft Word and two (Collins RCS and Hw Torpedo) do not currently manage any risks given the delivery of all primary project elements. Defence has advised that a risk management system will not be mandated until the outcomes of the CASG risk reform are known (see paragraph 1.52).

1.56 The JCPAA made a recommendation in September 2018 for Defence to plan and report a methodology to the Committee which shows how acquisition projects can transition from the use of spreadsheet risk registers to tools with better version control.75

Project maturity framework

1.57 Project Maturity Scores have been a feature of the Major Projects Report since its inception in 2007–08. The DMO Project Management Manual 2012, defined a maturity score as:

The quantification, in a simple and communicable manner, of the relative maturity of capital investment projects as they progress through the capability development and acquisition life cycle.76

1.58 Maturity scores are a composite indicator, cumulatively constructed through the assessment and summation of seven different attributes. The attributes are: Schedule, Cost, Requirement, Technical Understanding, Technical Difficulty, Commercial, and Operations and Support, which are assessed on a scale of one to 10.77 Comparing the maturity score against its expected life cycle gate benchmark provides internal and external stakeholders with a useful indication of a project’s progress.

1.59 The ANAO has previously identified that the policy guidance underpinning the attribution of maturity scores would benefit from a review for internal consistency and the relationship to Defence’s contemporary business. For example, allocating approximately 50 per cent of the maturity score at Second Pass Approval, regardless of acquisition type, is often inconsistent with the proportion of project budget expended, and the remaining work required to deliver the project. Further, the existing project maturity score model does not always effectively reflect a project’s progress during the often protracted build phase, particularly for developmental projects. During this phase it can be expected that maximum expenditure will occur, and that many risks will be realised, some of which will only emerge as test and evaluation activities are pursued through to acceptance into operational service.

1.60 In May 2016, the JCPAA recommended ‘that the Department of Defence work with the Australian National Audit Office to review and revise Defence’s policy regarding Project Maturity Scores in time for the new approach to be implemented in the next Major Projects Report.’78 Again in October 2017, the JCPAA recommended ‘that the Department of Defence commence discussions with the Australian National Audit Office on updating Project Maturity Scores.’79 At the JCPAA hearing held on 23 March 2018, Defence undertook to update the framework by mid-2018 with a two-stage process: first to remediate inconsistencies in the policy and accommodate Interim Capability Life Cycle terminology; then to undertake a more substantial amendment of the policy.80 Defence advised the ANAO in September 2018 that the maturity score process is now being re-considered within the CASG risk reform context.

Caveats

1.61 In 2017–18, the ANAO noted a reduced trend of Major Projects which have achieved significant milestones with caveats.81 The ANAO also notes advice from Defence that it discourages Independent Assurance Reviews recommending caveats at FOC. Growler is the only MPR project which has achieved a major milestone with caveats, related to training requirements for IMR in 2017, which have since been resolved.82

1.62 The ANAO will continue to monitor the declaration and resolution of caveats in future reviews, including those related to projects which have been removed from the MPR with outstanding caveats which are required to be reported by Defence in the Statement by the Secretary of Defence until their final status is accepted by the Capability Manager.83 In 2017–18, the ARH Tiger Helicopters project, which has exited the MPR, reported the closure of remaining caveats.84

2. Analysis of Projects’ Performance

2.1 Performance information is important in the management and delivery of major Defence equipment acquisition projects (Major Projects). It informs decisions about the allocation of resources, supports advice to government, and enables stakeholders to assess project progress.

2.2 Project performance has been the subject of many of the reviews of the Department of Defence (Defence), and a consistent area of focus of the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) since the first Major Projects Report (MPR). This chapter progresses previous Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) analysis over project performance.

Project performance analysis by the ANAO

2.3 The ANAO utilises three key performance indicators to analyse the major dimensions of projects’ progress and performance. These indicators are the:

- percentage of budget expended (Budget Expended) — which measures the total expenditure as a percentage of the total current budget;

- percentage of time elapsed (Time Elapsed) — which measures the percentage of time elapsed from original approval to the forecast Final Operational Capability (FOC)85; and

- percentage of key materiel capabilities delivered (Capability Delivery Progress) — which measures the total capability elements delivered as a percentage of the total capability elements across all Major Projects.

2.4 The ANAO has previously utilised Defence’s prediction of expected final capability, as reported in Section 4.1 of each Project Data Summary Sheet (PDSS). In 2015–16, the ANAO derived an indicator for ‘Capability Delivery Progress’, which aims to show the current capability delivered, in terms of capability elements included within the agreed Materiel Acquisition Agreements (MAAs). These performance indicators are measured in percentage terms, to enable comparisons between projects of differing scope, and to provide a view across the selected projects of progress and performance.

2.5 The following sections of this chapter provide analysis relating to the three principal components of project performance. This includes in-year information, longitudinal analysis and the results of project progress for the year-ended 30 June 2018. The first piece of analysis, in Figure 2 below, sets out each project’s Budget Expended and Time Elapsed.86

Figure 2: Budget Expended and Time Elapsed

Note: BMS does not have IOC or FOC milestones. These were to be linked to Work Packages B-D which received government approval in September 2017 under LAND 200. Work Package A achieved FMR in December 2017. MAA closure did not occur in October 2018 as forecast.

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2017–18 PDSSs.

2.6 Figure 2 shows that for most projects (22 of 26), Budget Expended is broadly in line with, or lagging, Time Elapsed. This relationship is generally expected in an acquisition environment predominantly based on milestone payments. However, due to the varying complexity, stages and acquisition approaches across the portfolio of projects, further analysis of these simple performance measures is required to provide a better understanding of key variances.

2.7 Where Budget Expended is significantly lagging Time Elapsed the project schedule may be at risk, i.e. expenditure lags may indicate delays in milestone achievement. However this is not the case for the four projects where the Budget Expended is over 20 per cent less than the Time Elapsed in 2017–18, as detailed below:

- Joint Strike Fighter (Budget Expended 17 per cent, Time Elapsed 62 per cent) — a large scope increase ($10.5 billion) for the purchase of additional aircraft was approved in April 2014, with the project now beginning to enter into main production contracts, as aircraft development continues;

- Battlefield Airlifter (Budget Expended 55 per cent, Time Elapsed 80 per cent) — the project is yet to enter contracts relating to the acquisition of training devices. However, all ten aircraft have been delivered;

- Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) 2B (Budget Expended 36 per cent, Time Elapsed 58 per cent) — the project is still in design phases for some elements, with the project’s payment schedule structured so that the majority of payment milestones fall towards the end of the project’s life; and

- LHD Landing Craft (Budget Expended 74 per cent, Time Elapsed 94 per cent) — the variance reflects contingency and unallocated funds remaining as the project approaches closure.

2.8 Where Budget Expended leads Time Elapsed the project budget may be at risk, i.e. expenditure increases may indicate real cost increases. However, for the three projects where Budget Expended leads Time Elapsed by 10 per cent or more, the actual reasons are related either to early procurement of major equipment due to production timing, or schedule delays caused through platform availability, as detailed below:

- P-8A Poseidon (Budget Expended 66 per cent, Time Elapsed 53 per cent) — the majority of project expenditure is aligned with aircraft production, with seven out of 12 aircraft already delivered and the final aircraft scheduled for delivery in 2019–20, with FOC not scheduled until May 2022;

- Growler (Budget Expended 67 per cent, Time Elapsed 56 per cent) — expenditure reflects aircraft production costs (which represent a large proportion of project costs) having occurred before a large decrease in annual expenditure over the following years as work continues on the Mobile Threat Training Emitter System. All aircraft have now been delivered to Defence. The variance is also exacerbated by the length of time between Initial Operational Capability (IOC) (July 2018) and FOC (June 2022) with most of the major equipment being delivered by 2018; and

- Collins R&S (Budget Expended 91 per cent, Time Elapsed 78 per cent) — most of the materiel has been acquired and expenditure undertaken. In addition, originally planned installation dates have been extended based on submarine availability, reducing the proportion of time elapsed. Furthermore, in 2017–18, the project schedule was extended due to additional scope transferred from other projects, but additional budget to fund this scope was not transferred during the financial year, reducing Time Elapsed without reducing Budget Expended.

2.9 In each case, the performance information highlights projects requiring further attention. This is to ensure that surplus funds are returned to the Defence budget for re-allocation in a timely manner, the timing of key deliverables remains in focus, or planning focuses on bringing together all elements in a timely manner, as equipment is delivered.

Cost performance analysis

Budget Expended and Project Maturity

2.10 Figure 3, below, sets out each project’s Budget Expended against Project Maturity87 and shows that Budget Expended lags Project Maturity for the majority of projects (19 of 26). This relationship is expected for two reasons:

- in an acquisition environment predominantly based on milestone payments, projects will typically develop confidence in delivering their scope through design reviews, testing and demonstration, ahead of formal acceptance of milestone achievement or equipment deliveries (and expenditure of budget); and

- more generally, Budget Expended will often lag Project Maturity as the result of Defence’s project maturity framework attributing approximately 50 per cent of total Project Maturity at Second Pass Approval (the main investment decision by government)88 prior to any significant expenditure of budget.

2.11 In both cases, the Budget Expended is expected to catch up to Project Maturity over the course of the project’s life, with projects approaching closure expected to show Budget Expended and Project Maturity broadly in line with each other.

2.12 Budget Expended lags Project Maturity with a variance of 20 per cent or more in 13 projects. As expected, the majority of these projects are at relatively early stages and have expended minimal budget while progressing through design and testing phases, or are waiting on significant amounts of equipment to be delivered. The exceptions to this are projects that have delivered the majority of their major equipment, leading to an advanced maturity score, while the budget expended is lagging as items such as training equipment or weapons are yet to be delivered and paid for. Projects fitting this pattern are MH-60R Seahawk (all helicopters delivered while some weapons and training devices are outstanding), Battlefield Airlifter (all aircraft delivered while some training devices are outstanding), and HATS (all helicopters delivered while some training devices are outstanding). Additionally, LHD Landing Craft’s Budget Expended lags Project Maturity as this project has delivered all 12 vessels and other scope without requiring the full budget to be expended.

2.13 Where Budget Expended leads Project Maturity by a significant amount, this may indicate that the project is behind in development or achievement of its scope, or that the required scope is not affordable. There are no instances where Budget Expended leads Project Maturity by 20 per cent or more. The largest variance is for UHF SATCOM, where Budget Expended leads Project Maturity by 17 per cent. The project’s maturity score has been affected by delays in software development, while the majority of budget has been expended and the project is funding further development with contingency.

Figure 3: Budget Expended and Project Maturity

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2017–18 PDSSs.

Second Pass Approval and 30 June 2018 approved budget

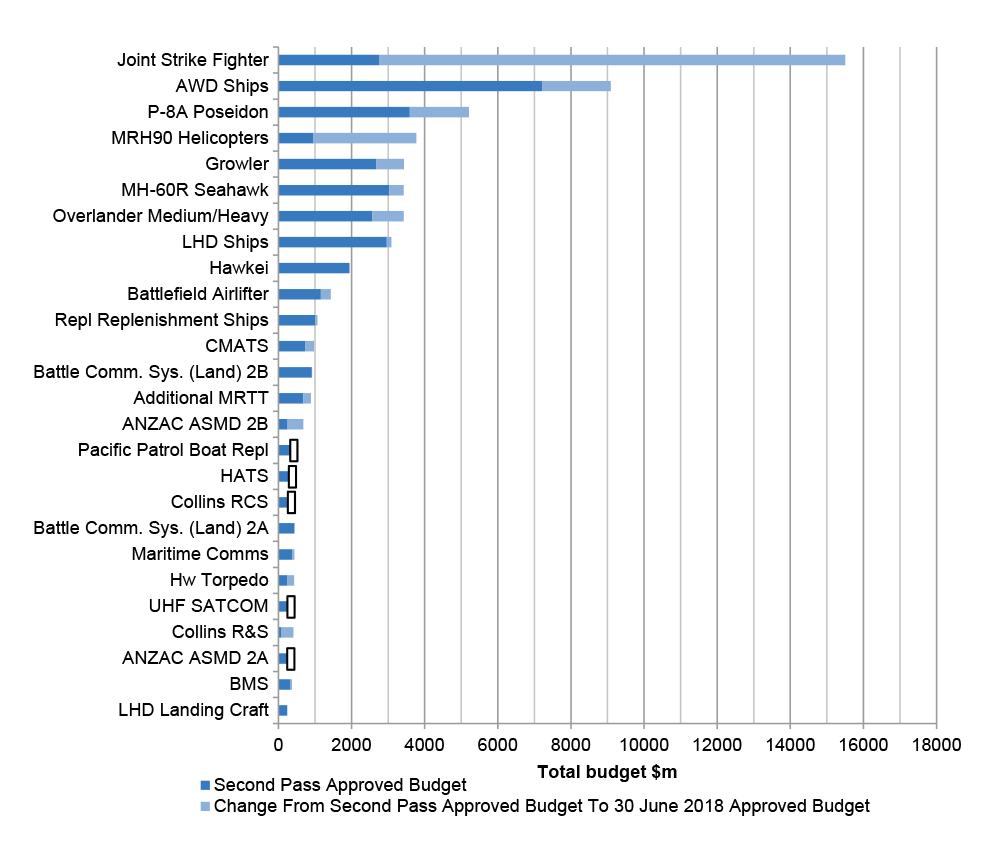

2.14 Figure 4, below, compares each project’s approved budget at initial Second Pass Approval and its approved budget at 30 June 2018.

2.15 The total budget for the 26 projects at 30 June 2018 was $59.4 billion, a net increase of $23.0 billion, when compared to the approved budget at initial Second Pass Approval of $36.5 billion.89

2.16 Figure 4 indicates all relative budget variations from initial Second Pass Approval. Six projects have variations of $500 million or more. The list below describes the components of these variations:

- Joint Strike Fighter — increase of $12.8 billion, comprising $10.5 billion for 58 additional aircraft in 2013–14, $1.9 billion for exchange rate variation and $0.4 billion for price indexation;