Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

2014-15 Major Projects Report

The objective of this report is to provide the Auditor-General’s independent assurance over the status of the selected Major Projects, as reflected in the Statement by the Secretary of Defence, and the Project Data Summary Sheets (PDSSs) prepared by Defence, in accordance with the Guidelines endorsed by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit.

!Part 1. ANAO Review and Analysis

Foreword

Defence’s Major Projects have continued to be the subject of considerable parliamentary and public interest throughout 2014–15, and are expected to remain so into the foreseeable future. With acquisition expenditure expected to nearly double over the period to 2018–19, and government investment in Defence acquisitions covering major land, sea and air platforms, there is also strong justification to maintain a high level of transparency and accountability over this activity.

Following the delisting of the Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO) from 1 July 2015, and consistent with the recommendations of the Government’s First Principles Review: Creating One Defence, the functions of the DMO were merged back into Defence under the new Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group. The ongoing reporting of the status of Major Projects under the new Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group is the subject of this, the eighth Major Projects Report.

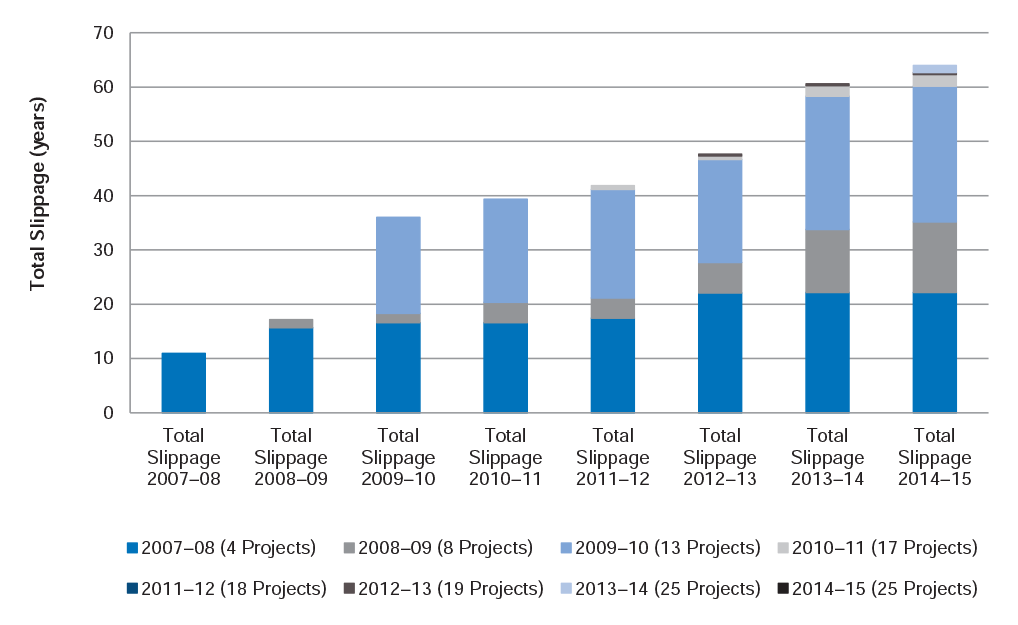

The former DMO oversaw the introduction of a Military-Off-The-Shelf focused acquisition strategy for Major Projects, following the Defence Procurement Review 2003 (Kinnaird Review). This has resulted in an improvement in schedule performance over time, with current analysis showing that 73 per cent of the total schedule slippage across the Major Projects relates to projects approved prior to DMO’s demerger from Defence in 2005. It is important that Defence continue to pursue these improvements in project delivery.

For the first time, the 2014–15 Major Projects Report’s scope includes the project financial assurance statement, which provides readers with an articulation of each project’s financial position in relation to delivering project capability. The independent conclusion now provides assurance over these statements within each Project Data Summary Sheet.

The ongoing support of the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) remains important to the development of the Major Projects Report, providing guidance and insight through their considerations. Each year the JCPAA endorses the Guidelines for the review, and provides direction and recommendations to assist the development of future Major Projects Reports.

As previously, this year’s review continued the strong working relationship between the ANAO and Defence departmental staff. The three Defence service chiefs and the Chief Information Officer, and industry, also provided valuable input to the review.

Summary

Introduction

1. Due to the high cost and impact on the economy, contribution to national security and the challenges involved in completing them within budget, on time and to the required level of capability, major Defence equipment acquisition projects (Major Projects) have continued to be the subject of considerable parliamentary and public interest throughout 2014–15. In this respect, the proposed Defence White Paper is expected to set out the Government’s priorities for future capability investment over the next 20 years. This is expected to include investment of over $89 billion in the acquisition of new submarines, frigates, offshore patrol vessels and other specialist naval vessels, following the Government’s commitment to a ‘continuous build’ of surface warships in Australia.1 Additionally, the land vehicle fleet will be replaced, new and improved air capabilities will be delivered, and investments will be made in supporting infrastructure, personnel and information technology systems.2

2. The proposed Defence White Paper is to be released during the implementation of the recommendations from the Government’s First Principles Review: Creating One Defence (First Principles Review). Notably, as an outcome of this process, the former Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO) was delisted from 1 July 2015, and its functions merged back into the Department of Defence (Defence), under the new Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group.3 Previously, the DMO had provided support to the Australian Defence Force’s (ADF) operations through the acquisition and sustainment of ADF capabilities4, expending some $5.3 billion on major and minor capital acquisition projects in 2014–15.5

3. While acquisition alone does not generate new capability for the ADF, the DMO performed a significant role in Defence acquisition. As such, the DMO was the focus of the Australian National Audit Office’s (ANAO’s) review work on Major Projects, including for the majority of this, the 2014–15 Major Projects Report (2014–15 MPR).

4. Following prescription as a Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997 agency in 2005, the DMO oversaw the introduction of a Military-Off-The-Shelf focused acquisition strategy, the analysis of which is depicted in Figures 8 and 9. The DMO also introduced a performance reporting regime in 2004, the Maturity Score Framework (discussed further at paragraphs 1.48 to 1.58), the data from which has been included within the analysis in the MPRs, to assist users in assessing the progress of projects over time. The DMO was responsible for acquisition risk management and financial management frameworks; assisted in the development of Materiel Acquisition (and Sustainment) Agreements, which progressed the level of governance in Defence acquisition; and introduced programs of professionalisation for project managers throughout Defence and Defence Industry.

5. The newly formed group will now manage the process of bringing new capabilities into service, including the Fundamental Inputs to Capability6, for example, the provision of personnel, training and command. The ANAO will continue to review Defence acquisition in the 2015–16 MPR, as the group assumes its acquisition responsibilities, and while progress on the implementation of the First Principles Review recommendations is ongoing.7

The 2014–15 Major Projects Report

6. This eighth report covers 25 of Defence’s Major Projects (2013–14: 30; 2012–13 and 2011–12: 29), and builds on the earlier work to improve the transparency of, and accountability for, the status of Major Projects. The Major Projects review is supported by the commitment of the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA), ‘…to maximise transparency and accountability in the Defence acquisition process for Major Projects that have been managed by DMO and will continue to be managed by the Department of Defence in future.’8

7. The benefits of this report have been noted by a variety of stakeholders, including Ministers, Parliamentary Committee members, industry and the media.

8. The ANAO’s review of Major Projects is completed in conjunction with the regular program of performance and financial statement audits conducted within the Defence portfolio. While by its nature, the report is not as in depth as a performance audit, it provides an opportunity to analyse data across a consistent range of projects over time, and complements the ANAO’s other Defence auditing and assurance functions.

2014–15 Major Projects selected for review

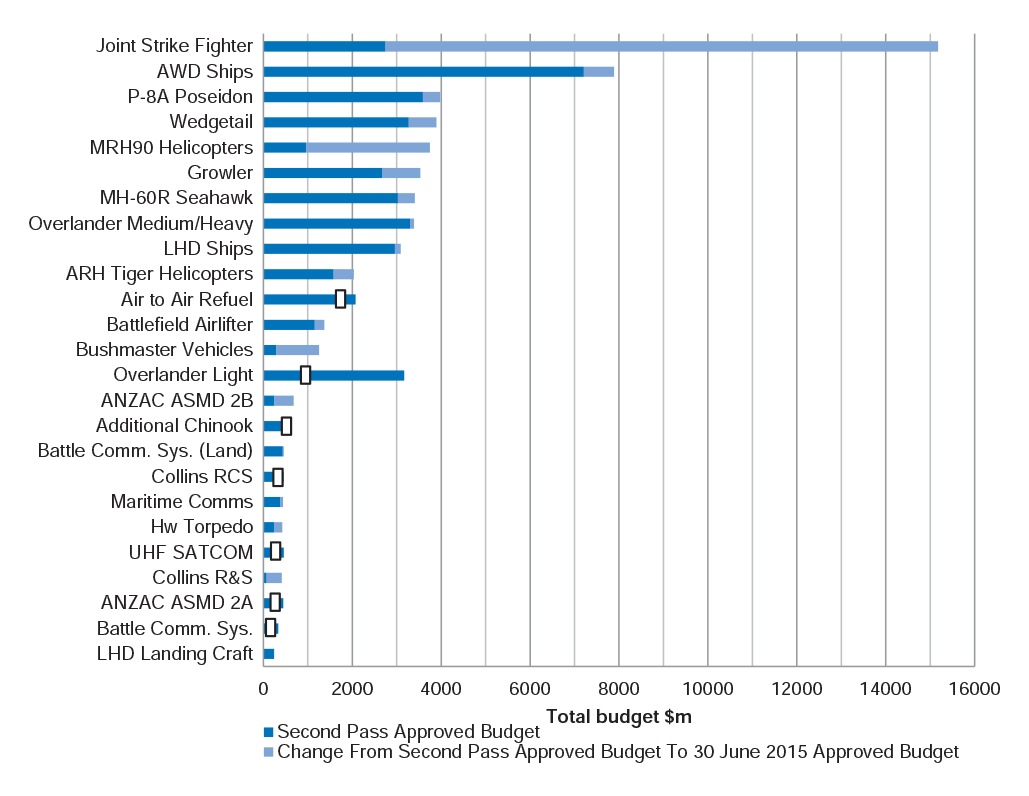

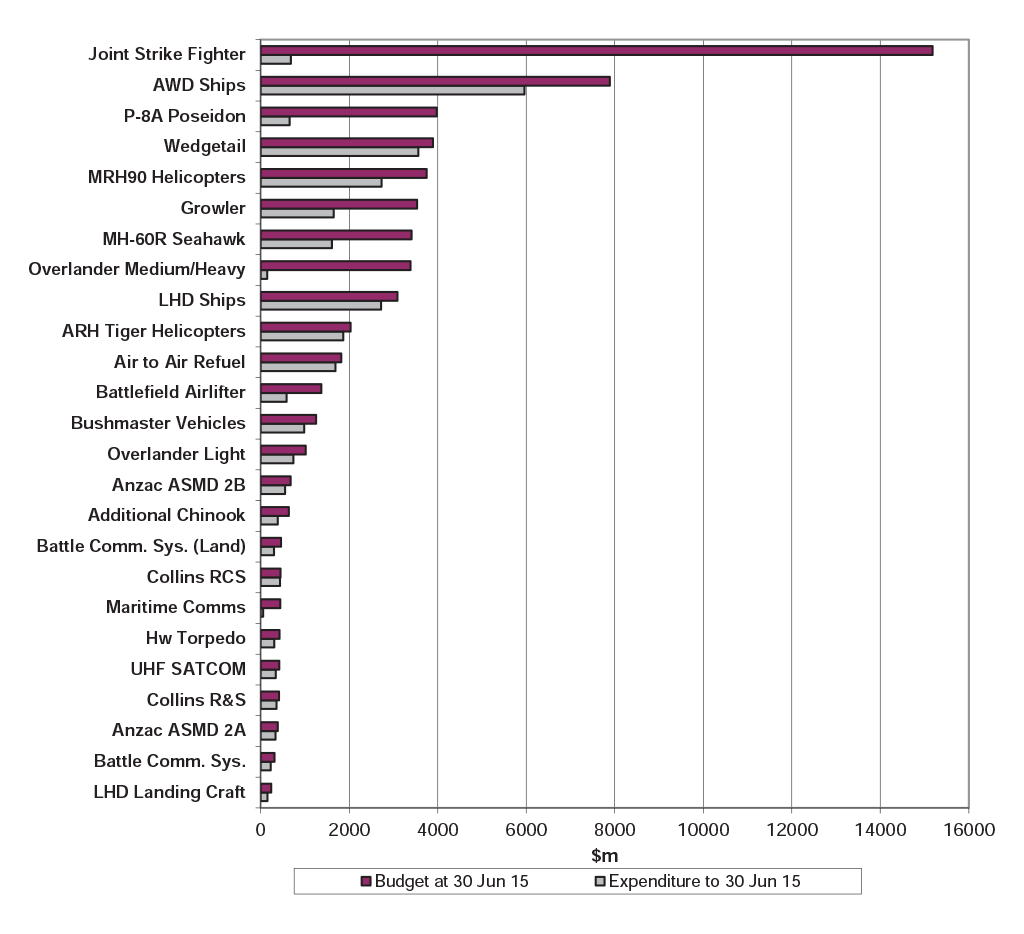

9. Projects are selected based on criteria included in the 2014–15 Major Projects Report Guidelines (the Guidelines), as endorsed by the JCPAA9, and provide a selection of the most significant Major Projects managed by Defence. The total approved budget for the Major Projects included in the report is approximately $60.5 billion, covering nearly 63 per cent of the budget within the Approved Major Capital Investment Program of $96.1 billion.10 The projects and their approved budgets are listed in Table 1, below.

Table 1: 2014–15 MPR projects and approved budgets at 30 June 2015

|

Project Number (Defence Capability Plan) |

Project Name (on Defence advice) |

Defence Abbreviation (on Defence advice) |

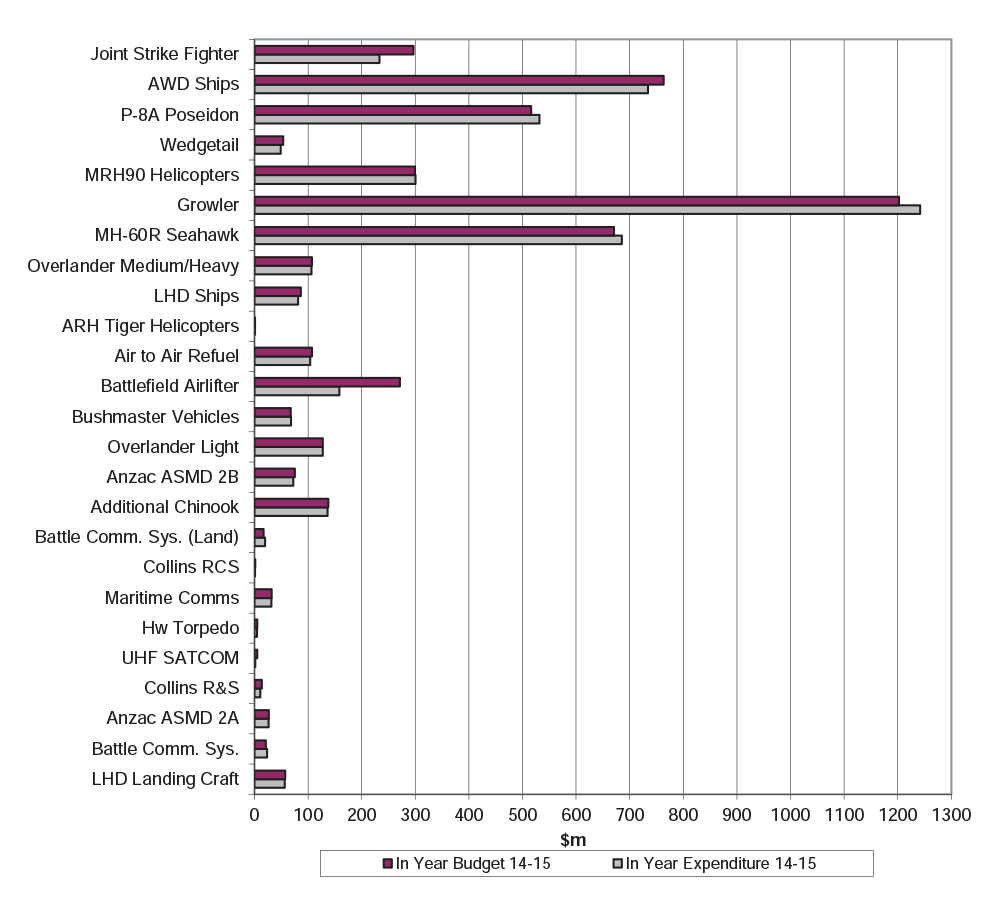

Approved Budget $m |

|

AIR 6000 Phase 2A/2B |

New Air Combat Capability |

Joint Strike Fighter |

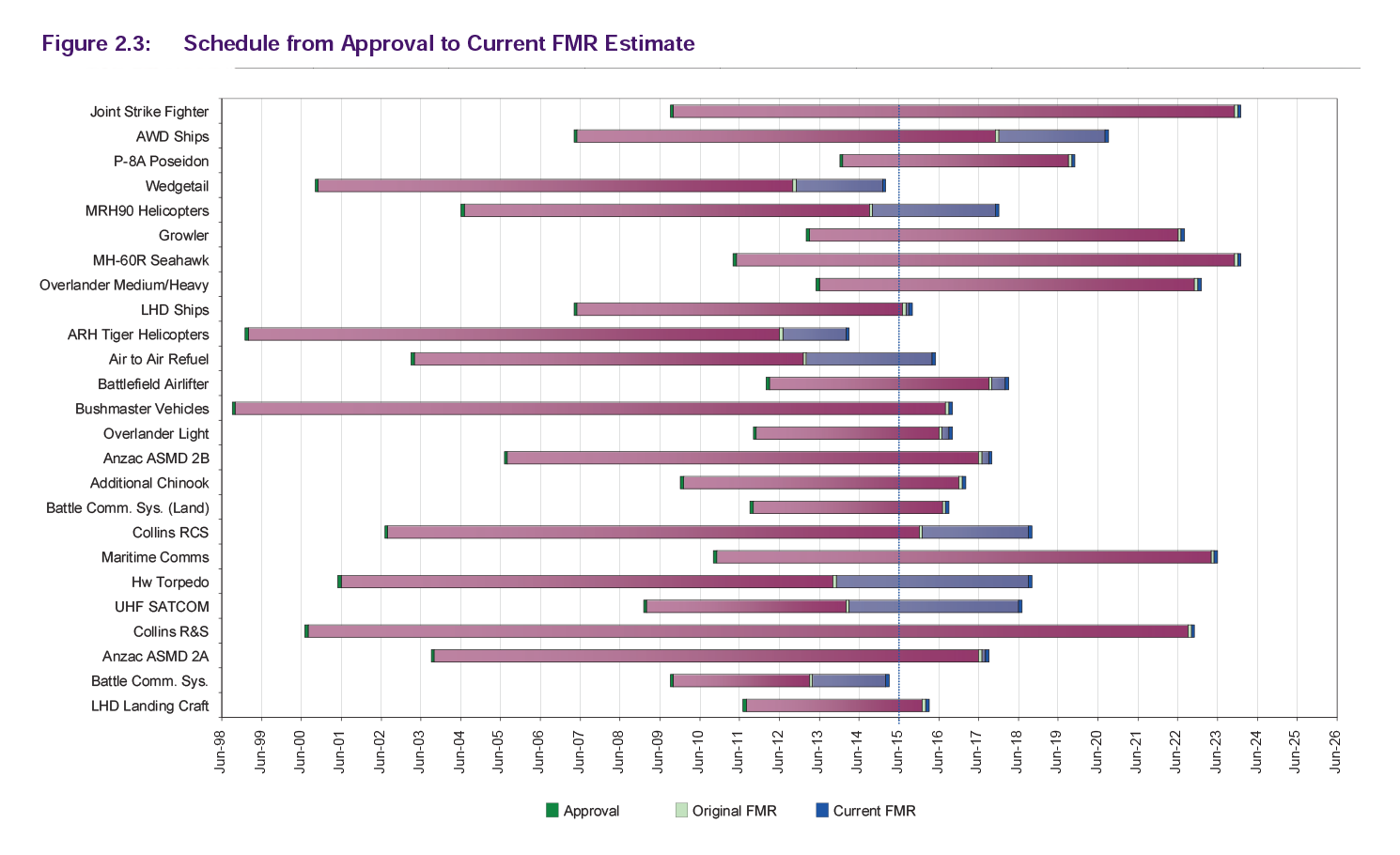

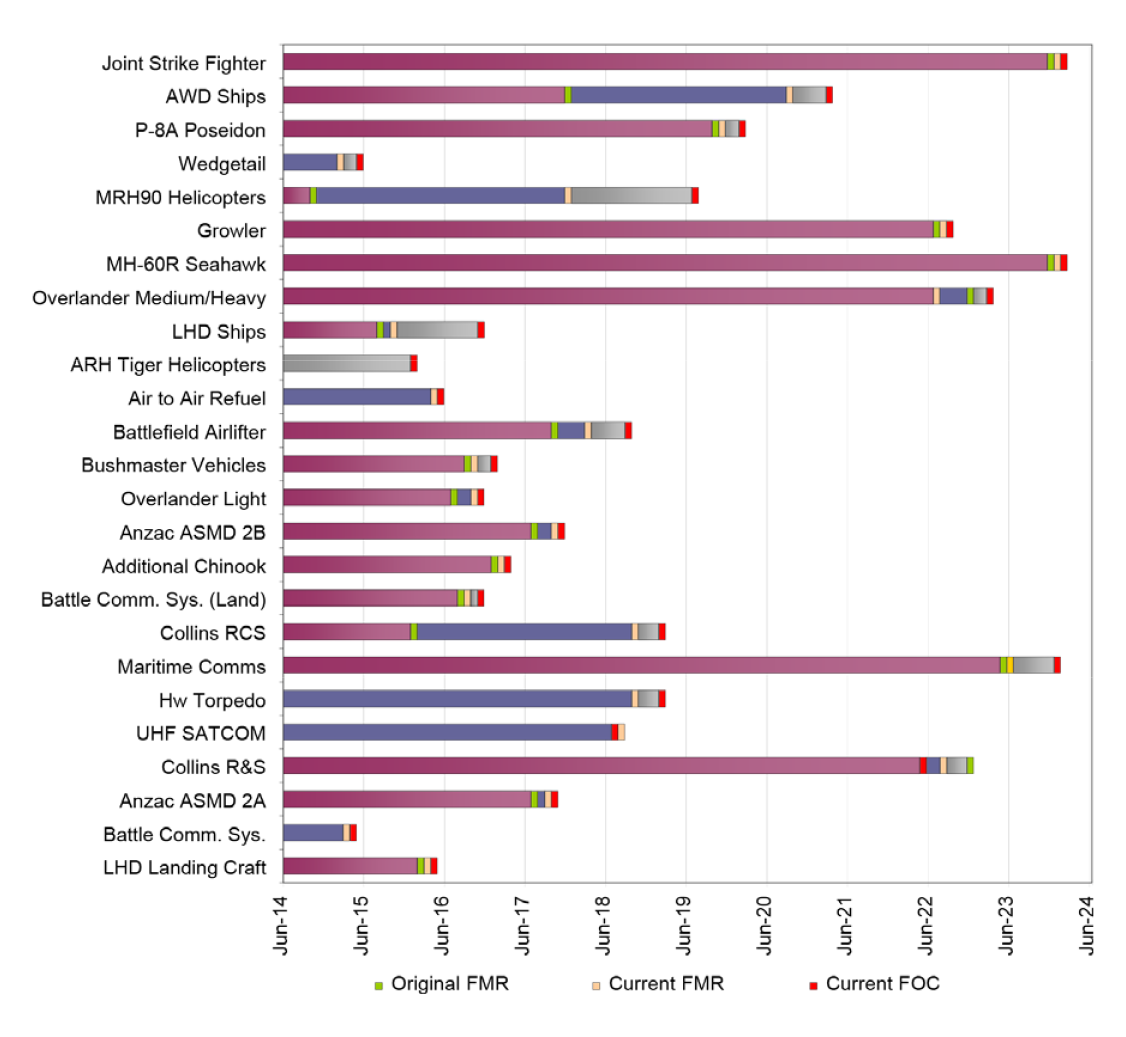

15 181.1 |

|

SEA 4000 Phase 3 |

Air Warfare Destroyer Build |

AWD Ships |

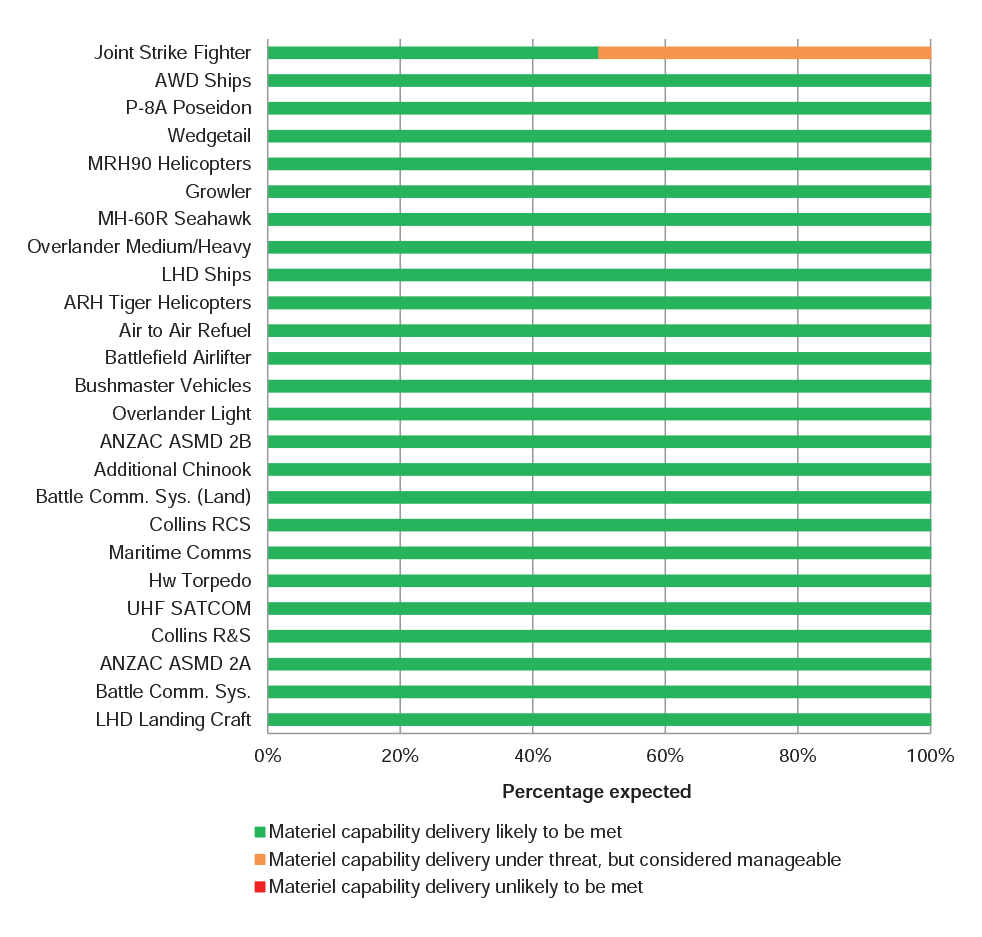

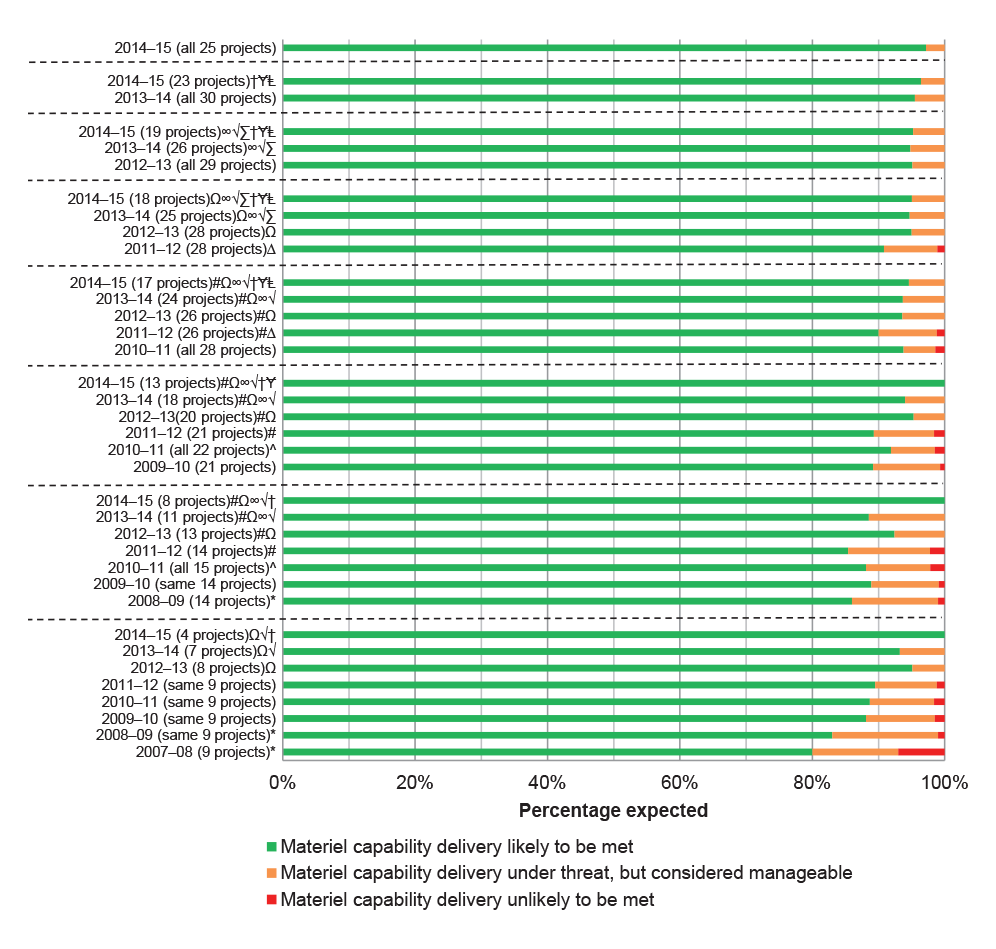

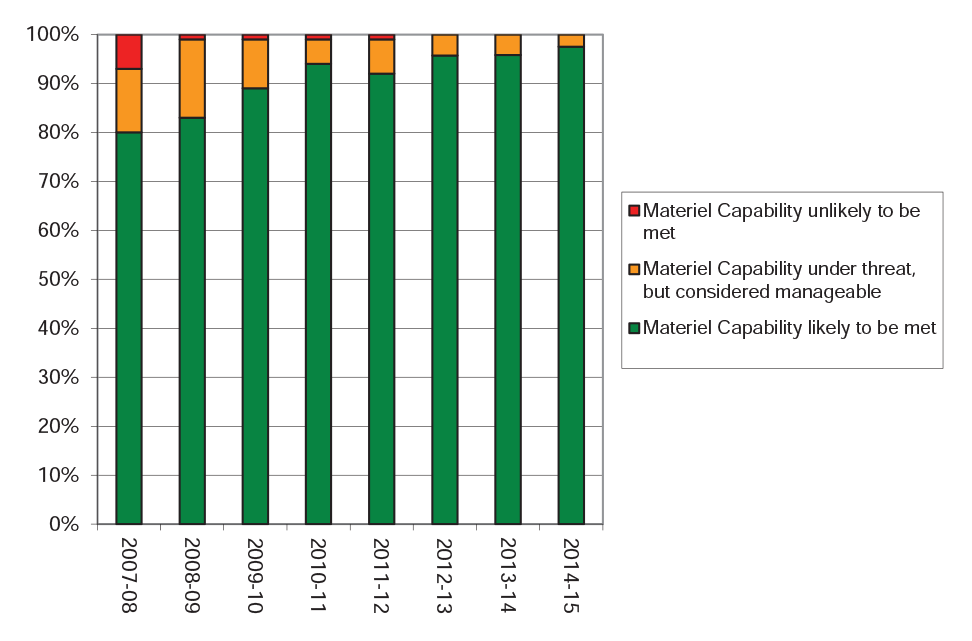

7 891.1 |

|

AIR 7000 Phase 2B |

Maritime Patrol and Response Aircraft System |

P-8A Poseidon1 |

3 977.8 |

|

AIR 5077 Phase 3 |

Airborne Early Warning and Control Aircraft |

Wedgetail |

3 893.2 |

|

AIR 9000 Phase 2/4/6 |

Multi-Role Helicopter |

MRH90 Helicopters |

3 747.5 |

|

AIR 5349 Phase 3 |

EA-18G Growler Airborne Electronic Attack Capability |

Growler |

3 531.4 |

|

AIR 9000 Phase 8 |

Future Naval Aviation Combat System Helicopter |

MH-60R Seahawk |

3 408.5 |

|

LAND 121 Phase 3B |

Medium Heavy Capability, Field Vehicles, Modules and Trailers |

Overlander Medium/Heavy |

3 387.6 |

|

JP 2048 Phase 4A/4B |

Amphibious Ships (LHD) |

LHD Ships |

3 091.0 |

|

AIR 87 Phase 2 |

Armed Reconnaissance Helicopter |

ARH Tiger Helicopters |

2 032.7 |

|

AIR 5402 |

Air to Air Refuelling Capability |

Air to Air Refuel |

1 822.3 |

|

AIR 8000 Phase 2 |

Battlefield Airlift – Caribou Replacement |

Battlefield Airlifter |

1 369.2 |

|

LAND 116 Phase 3 |

Bushmaster Protected Mobility Vehicle |

Bushmaster Vehicles |

1 250.5 |

|

LAND 121 Phase 3A |

Field Vehicles and Trailers |

Overlander Light |

1 015.7 |

|

SEA 1448 Phase 2B |

ANZAC Anti-Ship Missile Defence |

ANZAC ASMD 2B |

678.6 |

|

AIR 9000 Phase 5C |

Additional Medium Lift Helicopters |

Additional Chinook |

633.8 |

|

JP 2072 Phase 2A |

Battlespace Communications System |

Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) |

461.9 |

|

SEA 1439 Phase 4A |

Collins Replacement Combat System |

Collins RCS |

450.4 |

|

SEA 1442 Phase 4 |

Maritime Communications Modernisation |

Maritime Comms1 |

442.1 |

|

SEA 1429 Phase 2 |

Replacement Heavyweight Torpedo |

Hw Torpedo |

427.9 |

|

JP 2008 Phase 5A |

Indian Ocean Region UHF SATCOM |

UHF SATCOM |

420.4 |

|

SEA 1439 Phase 3 |

Collins Class Submarine Reliability and Sustainability |

Collins R&S |

411.7 |

|

SEA 1448 Phase 2A |

ANZAC Anti-Ship Missile Defence |

ANZAC ASMD 2A |

386.8 |

|

LAND 75 Phase 3.4 |

Battlefield Command Support System |

Battle Comm. Sys. |

313.0 |

|

JP 2048 Phase 3 |

Amphibious Watercraft Replacement |

LHD Landing Craft |

236.2 |

|

Total |

60 462.4 |

||

Note 1: P-8A Poseidon and Maritime Comms are included in the MPR program for the first time in 2014–15.

Note 2: Once a project is selected for review, it remains within the portfolio of projects under review until the JCPAA endorses its removal, normally once it has met the capability requirements of the Australian Defence Force.

Source: See the Project Data Summary Sheets in Part 3 of this report.

Report objective and structure

10. The objective of this report is to provide the Auditor-General’s independent assurance over the status of the selected Major Projects, as reflected in the Statement by the Secretary of Defence, and the Project Data Summary Sheets (PDSSs), prepared by Defence. Assurance from the ANAO’s review of the preparation of the PDSSs is conveyed in the Independent Review Report by the Auditor-General, prepared pursuant to the endorsed Guidelines, and included in Part 3 of this report (pp. 141–144).

11. For the first time in 2014–15, the review’s scope includes the project financial assurance statement within each PDSS, which was first introduced in the 2011–12 review. The Independent Review Report by the Auditor-General now provides assurance over these statements within each PDSS.

12. Excluded from the scope of the ANAO’s review is PDSS data on the identification of Risks and Issues, the Measures of Materiel Capability Delivery Performance, and ‘forecasts’ of future dates and the achievement of future outcomes. Accordingly, the Independent Review Report by the Auditor-General does not provide any assurance in relation to this information.

13. It is intended that all components of the PDSSs will be included within the ANAO’s scope of review, once Defence and ANAO work programs can facilitate the review and conclusion over all of the components of the PDSSs. However, the exclusions to the scope of the review noted above, are due to the lack of a system or systems from which to provide complete and accurate evidence11, in a sufficiently timely manner to facilitate the review. This has been an area of focus of the JCPAA over a number of years12, and will continue to be a part of the Defence and ANAO work program into the future.

14. The ANAO’s analysis on the three key elements of the PDSSs—cost, schedule and the progress towards delivery of required capability, and in particular, longitudinal analysis across these key elements of projects over time, are contained in Part 1 (pp. 1–80). The ANAO’s analysis over other elements of the PDSSs, for example, project maturity and elements excluded from the formal scope of the review, is also included in this part, to provide readers with a balanced perspective over all key acquisition elements.

15. Further insights and context by Defence on issues highlighted during the year are contained in Part 2 (pp. 81–138)—although not included within the scope of the review by the ANAO.

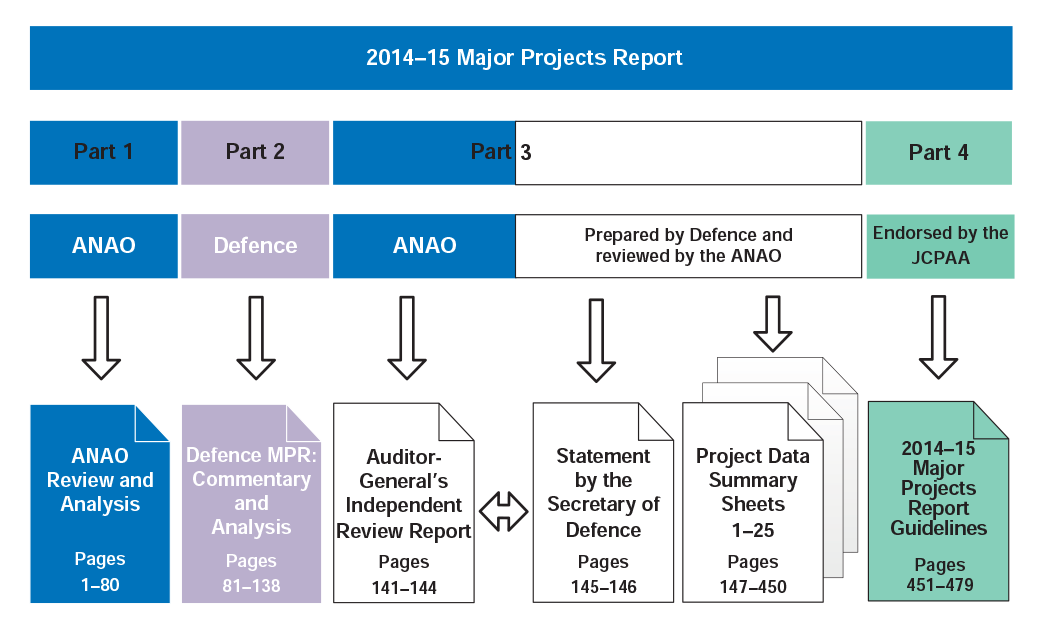

16. Part 4 includes the Guidelines endorsed by the JCPAA (pp. 451–479), which provide the criteria for the compilation of the PDSSs by Defence and the ANAO’s review. Figure 1, below, depicts the key parts of this report.

Figure 1: 2014–15 Report structure

Refer to paragraphs 10 to 16 in Part 1 of this report.

Note: To assist in conducting inter-report analysis, the presentation of data remains largely consistent and comparable with the 2013–14 MPR.

17. For each Major Project, a corresponding PDSS includes unclassified information on project performance, prepared by Defence in accordance with the Guidelines. Additionally, as projects appear in the MPR for multiple years, changes to the PDSS from the previous year are depicted in bold purple text.

18. Each PDSS comprises:

- Project Header: including name; capability and acquisition type; approval dates; total approved and in-year budgets; stage; complexity; and image;

- Section 1—Project Summary: including description; current status, financial assurance and contingency statement; context, including background, uniqueness, major risks and issues; and other current sub-projects;

- Section 2—Financial Performance: including budgets and expenditure; variances; and major contracts in place (in addition to quantities delivered as at 30 June 2015);

- Section 3—Schedule Performance: providing information on design development; test and evaluation; and forecasts and achievements against key project milestones including Initial Materiel Release (IMR), Final Materiel Release (FMR)13, Initial Operational Capability (IOC) and Final Operational Capability (FOC)14;

- Section 4—Materiel Capability Delivery Performance: provides a summary of Defence’s assessment of its progress on delivering key capabilities and whether the milestones were achieved15;

- Section 5—Major Risks and Issues: outlines the major risks and issues of the project and remedial actions undertaken for each;

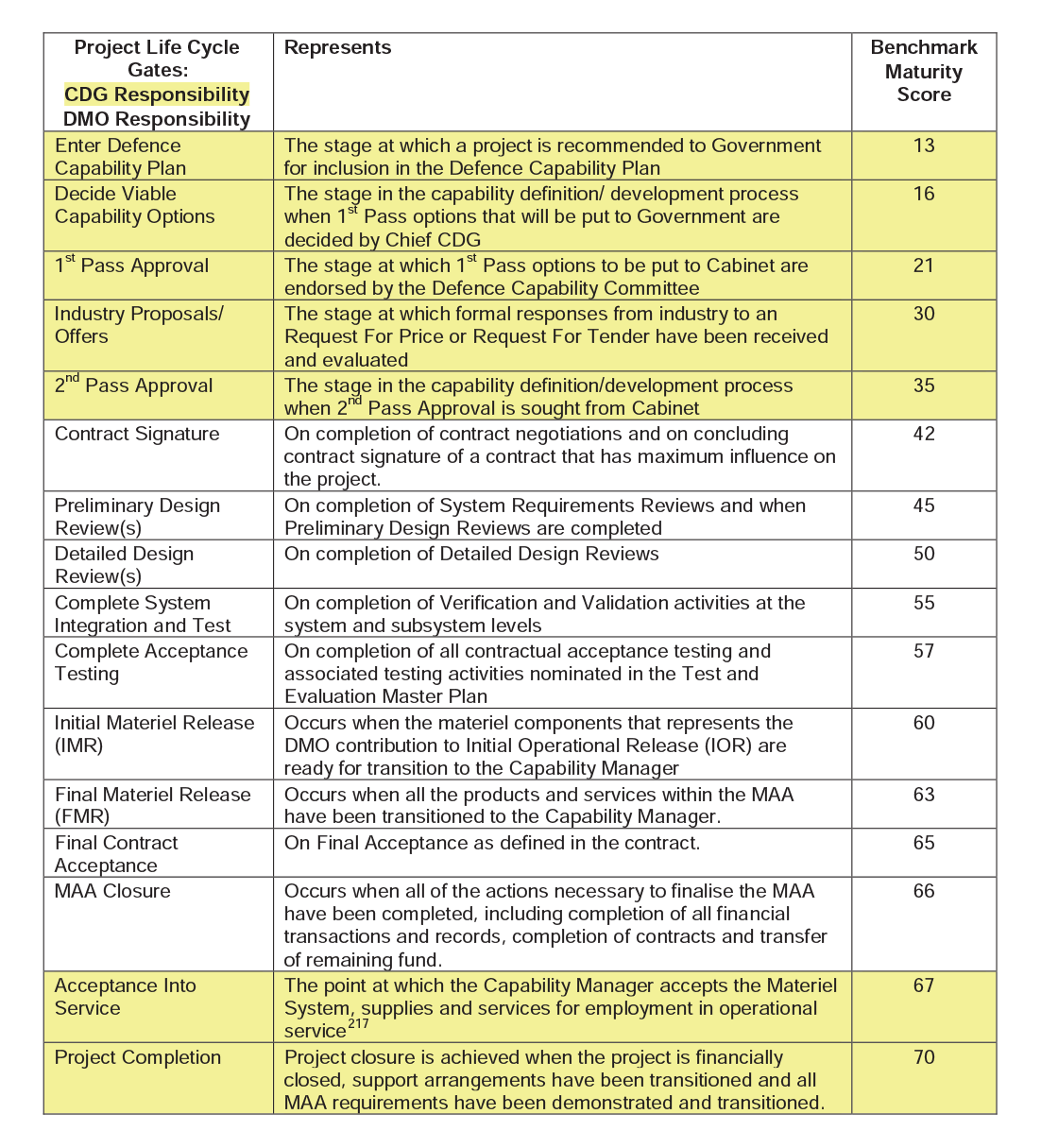

- Section 6—Project Maturity: provides a summary of the project maturity as defined by Defence and a comparison against the benchmark score;

- Section 7—Lessons Learned: outlines the key lessons that have been learned at the project level (further information on lessons learned by Defence are included in Defence’s Appendix 3); and

- Section 8—Project Line Management: details current project management responsibilities within Defence.

The role of the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit

19. Influential in establishing the MPR, the JCPAA has taken an active role in the development and review of the MPR program. Each year, the Committee considers the draft Guidelines, incorporating the selection of projects for review, and provides the Committee’s views in relation to the Guidelines’ content and development, prior to their endorsement. Following endorsement by the Committee, the Guidelines provide the criteria for Defence’s preparation of the PDSSs and the ANAO’s review.16

20. The main changes to the 2014–15 MPR Guidelines follow on from the recommendations made by the JCPAA in Report 442, Review of the 2012–13 Defence Materiel Organisation Major Projects Report, May 2014. Recommendations 2 and 7 from this report requested changes to the PDSS template to increase analysis and disclosure in relation to published estimates figures and 30 June actual expenditure17, and additional detail supporting the capability performance information. Implementation of these changes became effective in 2014–15.

21. Following the tabling of the 2013–14 MPR, the Committee published Report 448, Review of the 2013–14 Defence Materiel Organisation Major Projects Report, in May 2015. The JCPAA’s recommendation is set out below18:

Recommendation 1

The Committee recommends that the reformed Department of Defence continues to provide the same priority and appropriate resources to the Major Projects Report in the future as DMO have done in the past so that the achievements of the past eight years are not lost. The same level of effort should also apply to the future development of sustainment reporting.

22. As noted previously, the Committee’s recommendations contribute to the development of the MPR each year and the ANAO was advised that the formal response by Defence to this recommendation was provided to the Committee in late November 2015. At the time of preparing this report actioning of the recommendation is summarised below:

- Recommendation 1—to progress the enhancement of Defence sustainment reporting, an in-camera briefing was provided by Defence in November 2015. This provided the JCPAA with the opportunity to seek answers to (classified) sustainment matters directly from the relevant Capability Managers, expanding on information already provided in publicly available documents including the Defence Capability Plan, Portfolio Budget Statements, the Defence Annual Report and the MPR. To support this process, the JCPAA requested a sustainment brief from the ANAO, which was provided on 7 October 2015, and discussed at a private briefing of the JCPAA on 22 October 2015.

23. While Defence sustainment19 projects are generally outside the scope of the review, the Collins R&S project (which is defined as a sustainment project by Defence) has been included within the review at the request of the JCPAA since 2009–10. In addition, while ARH Tiger Helicopters and Collins RCS have been transferred to ‘sustainment’ by Defence, they remain included within the 2014–15 review, following the endorsement of the 2014–15 Guidelines.

24. In 2014–15, the ANAO also completed two performance audits on the former DMO’s outcomes from its Programme 1.2: Management of Capability Sustainment. The performance audit examining the management of the disposal of specialist military equipment was tabled in February 201520, and the performance audit examining the contribution made by Materiel Sustainment Agreements to the effective sustainment of specialist military equipment, was tabled in April 2015.21

Overall outcomes

25. This eighth report continues to review four of the nine Defence Major Projects which were initially introduced in the 2007–08 MPR22, and has continued to introduce new projects up to the originally agreed maximum of 30 projects. In 2014–15, 25 projects are reviewed. Maintaining a stable portfolio of projects over time has facilitated transparency and accountability for performance relating to cost, schedule and progress towards delivering the key capabilities of Major Projects, and provides opportunities for further longitudinal and other analysis into the future.

The 2014–15 Major Projects review (Chapter 1)

26. Under section 19A(5) of the Auditor-General Act 1997, the ANAO has reviewed the PDSS data as a priority assurance review and presents the Independent Review Report by the Auditor-General. As part of this review, the ANAO assessed the progress of Defence in addressing previously raised issues in relation to the administration of Major Projects.

27. In 2014–15, issues were noted within the following areas of project management:

- budget and project management, with acknowledgement by AWD Ships that the project did not have sufficient funds to complete delivery of the approved capability and required $1.2 billion in additional funding.23 See further explanation in paragraph 1.24;

- price indexation and budget allocations, and inconsistency in the determination and recording of contingency funds (Section 1 of the PDSS). See further explanation in paragraphs 1.32 to 1.35;

- variability in the interpretation of project progress towards delivering required capability (Section 4 of the PDSS). See further explanation in paragraph 2.60;

- inconsistency in the recording and reporting of major risks and issues by project offices, and reporting within the mandated Predict! and Excel risk management systems24 (Section 5 of the PDSS). See further explanation in paragraphs 1.40 to 1.44; and

- inconsistency in the application of the project maturity framework25 (although improved from 2013–14), which is weighted towards pre Second Pass Approval processes, reducing the ability to adequately indicate progress during the acquisition phase (Section 6 of the PDSS). See further explanation in paragraphs 1.48 to 1.58.

28. In 2014–15, the results of the ANAO’s priority assurance review of the 25 PDSSs, was that nothing has come to the attention of the ANAO that causes us to believe that the information and data in the PDSSs, within the scope of our review, has not been prepared, in all material respects, in accordance with the Guidelines.

Analysis of projects’ performance (Chapter 2)

29. The data reviewed in the PDSSs covers the three major dimensions of project performance: cost, schedule, and progress towards delivering the planned capability. Table 2 below, provides summary data on the Defence approved budget, schedule performance and progress toward delivering capabilities for the Major Projects covered in this report, and compares data against that reported in previous MPR editions.

30. A significant contributor to the reduction of slippage shown in the 2014–15 MPR (1 115 months to 768 months), is the removal of a number of projects which had not reached Final Operational Capability (FOC) by 30 June 2014. These projects are Hornet Upgrade (39 months), FFG Upgrade (132 months), HF Modernisation (147 months) and SM-2 Missile (26 months), totalling 344 months of the total net decrease shown of 347 months.

31. Of the above projects, Hornet Upgrade achieved FOC for Phase 2.3 in October 2014. The HACTS/HIP component, which will upgrade aircraft simulators, was transferred out of the project, and is currently due to achieve FOC in January 2017. In addition, SM-2 Missile, which was reported in the 2013–14 MPR with a forecast FOC date of February 2015, achieved FOC in June 2015. The FFG Upgrade and HF Modernisation projects have not achieved FOC as yet, with current forecast dates of March 2016 and December 2016 respectively.

Table 2: Summary longitudinal analysis

|

|

2012–13 MPR |

2013–14 MPR |

2014–15 MPR |

|

Number of Projects |

29 |

30 |

25 |

|

Total Approved Budget |

$44.3 billion |

$59.4 billion |

$60.5 billion |

|

Total Budget Variation since Second Pass Approval |

$6.5 billion (14.7 per cent) |

$16.8 billion (28.3 per cent) |

$18.5 billion (30.6 per cent) |

|

In-year Approved Budget Variation |

-$1.5 billion (-3.4 per cent) |

$12.8 billion (21.5 per cent) |

$2.9 billion (4.9 per cent) |

|

Total Schedule Slippage1,2 |

957 months (36 per cent) |

1 115 months (36 per cent) |

768 months (28 per cent) |

|

Average Schedule Slippage per Project |

35 months |

38 months |

31 months |

|

In-year Schedule Slippage3 |

147 months (5 per cent) |

205 months (7 per cent) |

41 months (2 per cent) |

|

Expected Capability4 |

|||

|

High level of confidence of delivery (Green) |

95 per cent |

96 per cent |

97 per cent |

|

Under threat, considered manageable (Amber) |

5 per cent |

4 per cent |

3 per cent |

|

Unlikely to be met (Red) |

0 per cent |

0 per cent |

0 per cent |

Refer to paragraphs 29 to 44 in Part 1 of this report.

Note 1: The data for the 25 Major Projects in the 2014–15 MPR compares the data from projects in the 2013–14 MPR and 2012–13 MPR.

Note 2: Slippage refers to the difference between the original government approved date and the current forecast date. These figures exclude schedule reductions over the life of the project.

Note 3: Based on the 29 projects from the 2011–12 MPR, 26 projects from the 2012–13 MPR and 23 projects from the 2013–14 MPR respectively.

Note 4: The grey section of the table is excluded from the scope of the ANAO’s priority assurance review. See further explanation in paragraph 12 in Part 1 of this report.

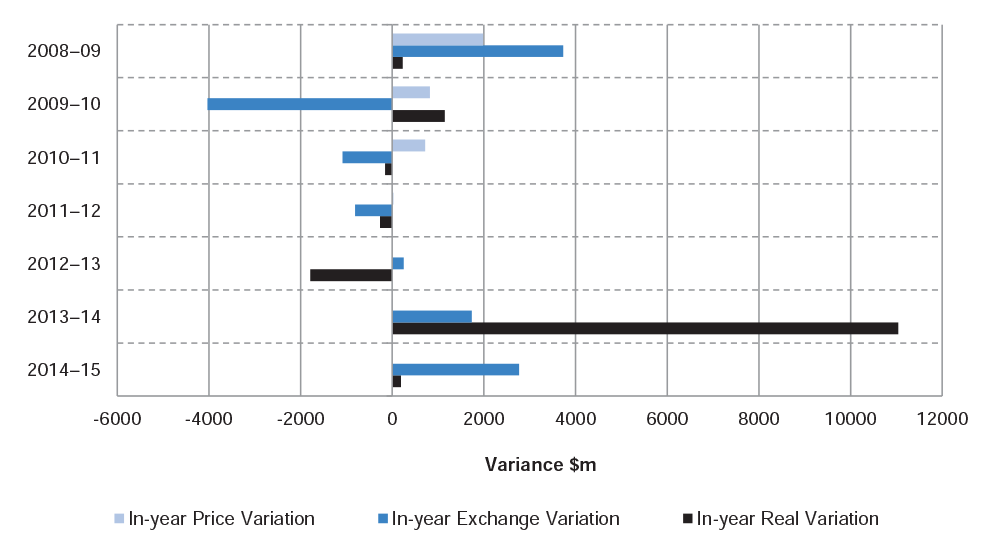

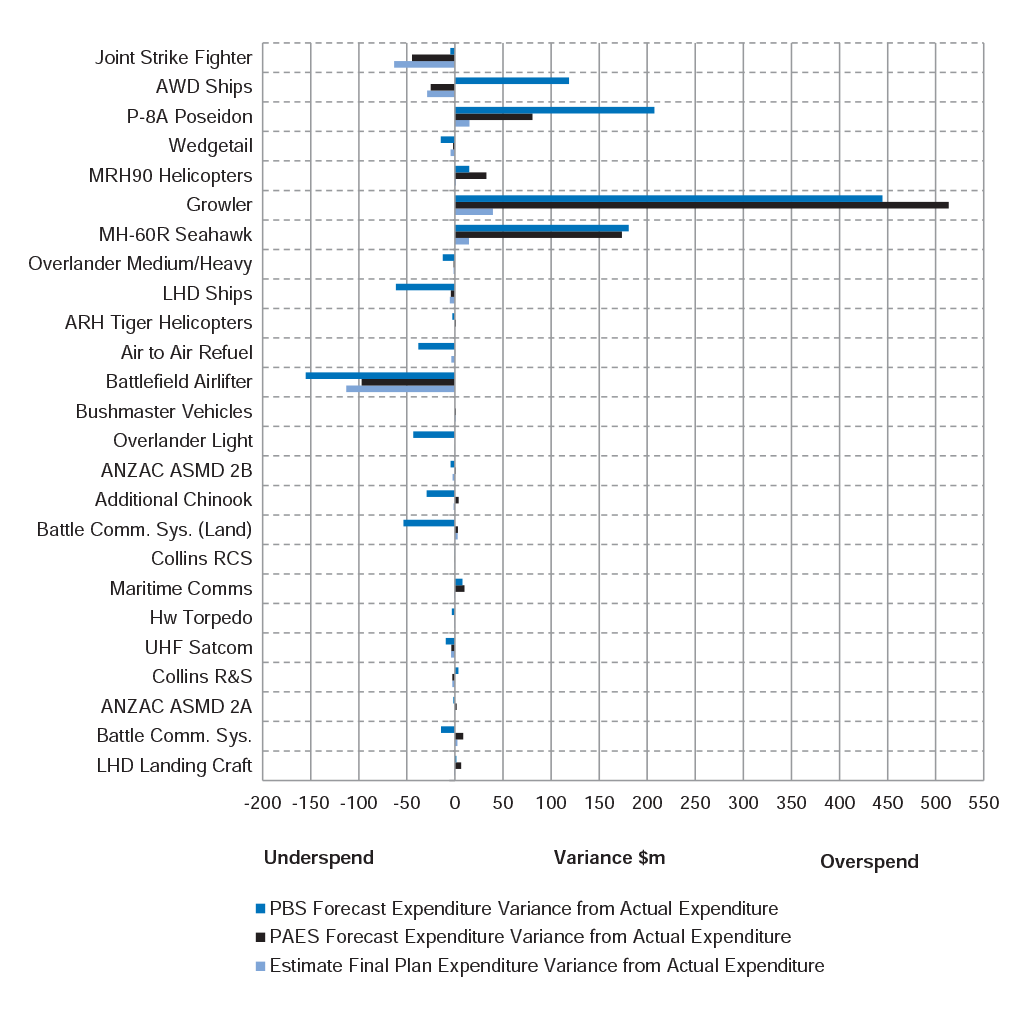

Cost

32. Within the review period, all projects except for AWD Ships, reported that they could continue to operate within the total approved budget of $60.5 billion.26 The joint Ministerial announcement on 22 May 2015, by the then Minister for Defence and Minister for Finance, stated that the AWD Ships project would require additional approved funding of $1.2 billion to deliver the required capability (approved July 2015).27

33. The total budget for Major Projects included in this MPR has increased by $18.5 billion (44.0 per cent) since Second Pass Approval. Refer to Table 3, below.

Table 3: Budget variation post Second Pass Approval by Variation type

|

Project |

Variation |

Explanation |

Year |

Amount $b |

|

|

Joint Strike Fighter |

Scope increase |

58 additional aircraft |

2013–14 |

10.5 |

|

|

MRH90 Helicopters |

Scope increase/budget transfers |

34 additional aircraft |

2005–06 |

2.4 |

|

|

Overlander Medium/Heavy |

Scope increase/budget transfers |

General program supplementation |

2013–14 |

0.7 |

|

|

Bushmaster Vehicles |

Scope increase |

715 additional vehicles |

Various |

0.8 |

|

|

Other |

Scope increase/budget transfers (net) |

Other scope changes and transfers |

Various |

(2.5) |

|

|

|

Sub-total |

|

11.9 |

||

|

Price Indexation – materials and labour (net) |

|

5.1 |

|||

|

Exchange Variation – foreign exchange (net) |

|

1.5 |

|||

|

|

Total |

18.5 |

|||

Note: Variations greater than $500 million are depicted in this table. For the breakdown of in-year variation, refer to Table 6 of this report.

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2014–15 PDSSs.

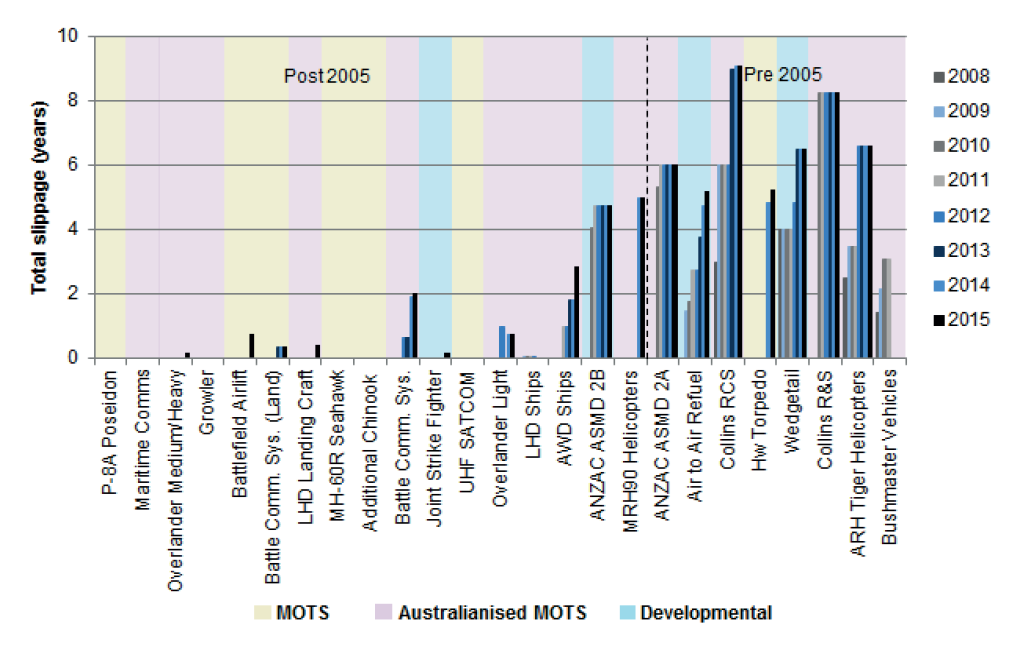

Schedule

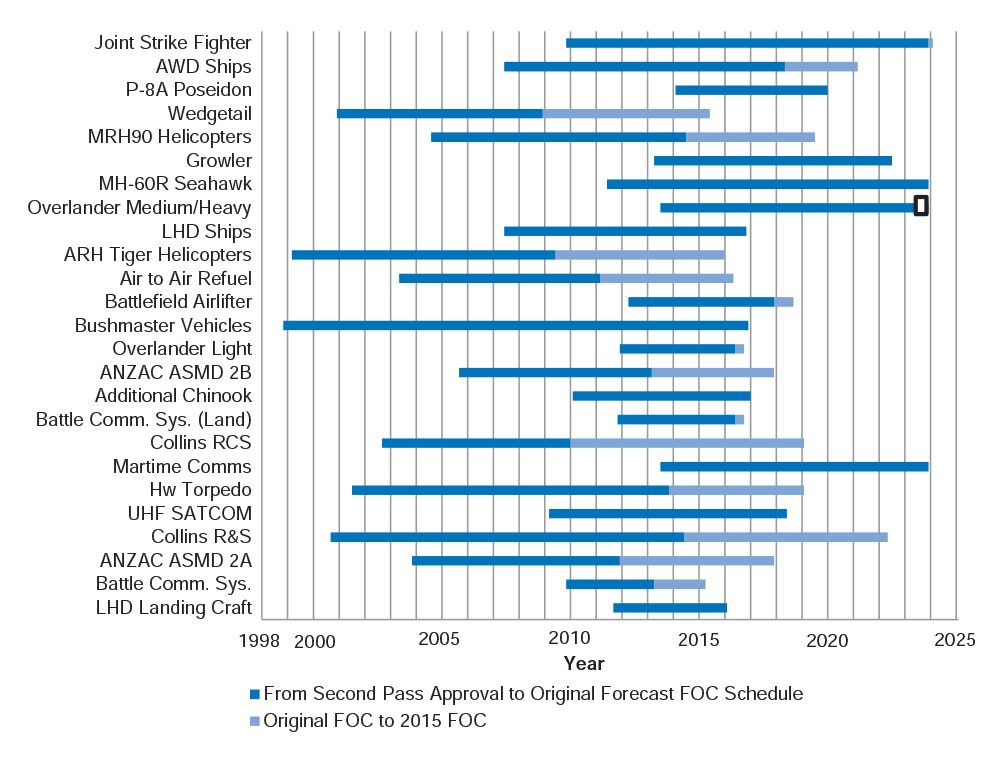

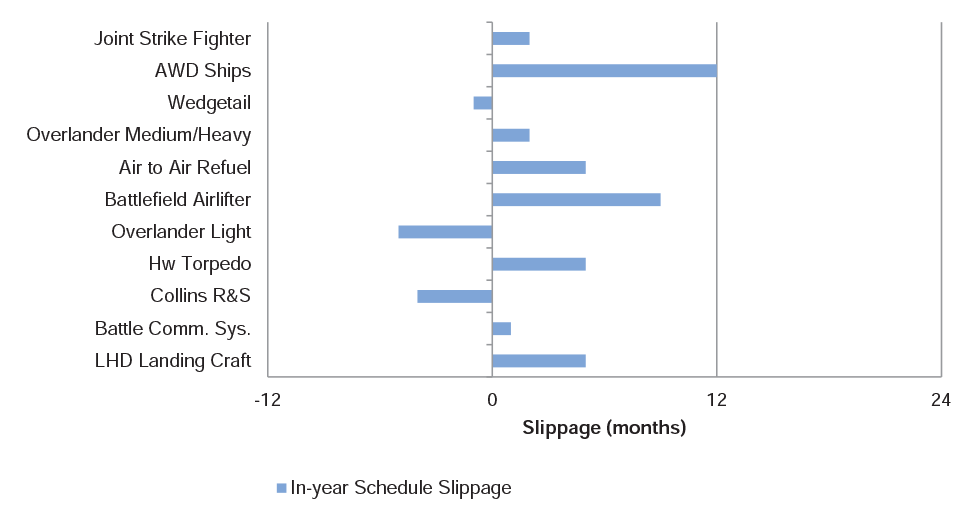

34. Maintaining Major Projects on schedule remains an ongoing challenge for Defence28; in turn affecting when the capability is made available for operational release and deployment by the ADF, and increasing the cost to delivery.29 In the 2014–15 MPR, the total schedule slippage for the 25 Major Projects as at 30 June 2015 is 768 months (2013–14: 1 115 months) when compared to the initial schedule first approved by government. This represents a 28 per cent (2013–14: 36 per cent) increase on the originally approved schedule. Refer to Table 4, below for details of in-year and total schedule slippage by project, for projects in the 2014–15 MPR.

Table 4: Schedule slippage from original planned Final Operational Capability

|

Project |

In-year (months) |

Total (months) |

Project |

In-year (months) |

Total (months) |

|

Joint Strike Fighter |

2 |

2 |

Overlander Light |

0 |

9 |

|

AWD Ships |

12 |

34 |

ANZAC ASMD 2B |

0 |

57 |

|

P-8A Poseidon |

0 |

0 |

Additional Chinook |

0 |

0 |

|

Wedgetail |

0 |

78 |

Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) |

0 |

4 |

|

MRH90 Helicopters |

0 |

60 |

Collins RCS |

0 |

109 |

|

Growler |

0 |

0 |

Maritime Comms |

0 |

0 |

|

MH-60R Seahawk |

0 |

0 |

Hw Torpedo |

5 |

63 |

|

Overlander Medium/Heavy |

2 |

2 |

UHF SATCOM |

0 |

0 |

|

LHD Ships |

0 |

0 |

Collins R&S |

0 |

99 |

|

ARH Tiger Helicopters |

0 |

79 |

ANZAC ASMD 2A |

0 |

72 |

|

Air to Air Refuel |

5 |

62 |

Battle Comm. Sys. |

1 |

24 |

|

Battlefield Airlifter |

9 |

9 |

LHD Landing Craft |

5 |

5 |

|

Bushmaster Vehicles |

0 |

0 |

|

|

|

|

Total |

|

|

|

41 |

768 |

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2014–15 PDSSs.

35. While it should be noted that platform availability can contribute to the slippage within some projects, significant delays relate to those projects with the most developmental content. For example, AWD Ships, Wedgetail, MRH90 Helicopters and ANZAC ASMD 2B.

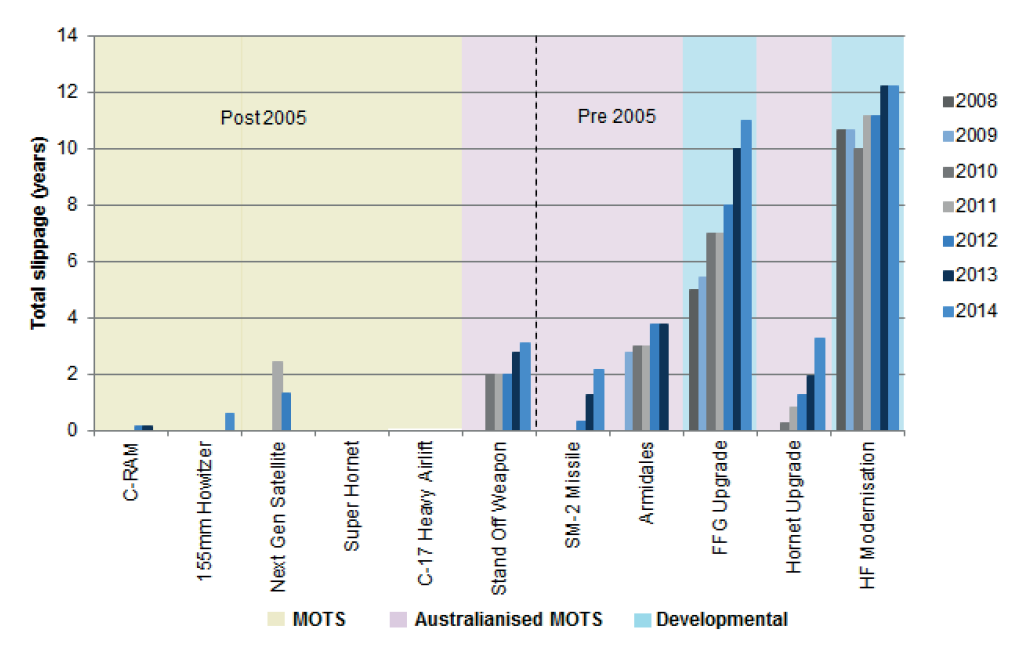

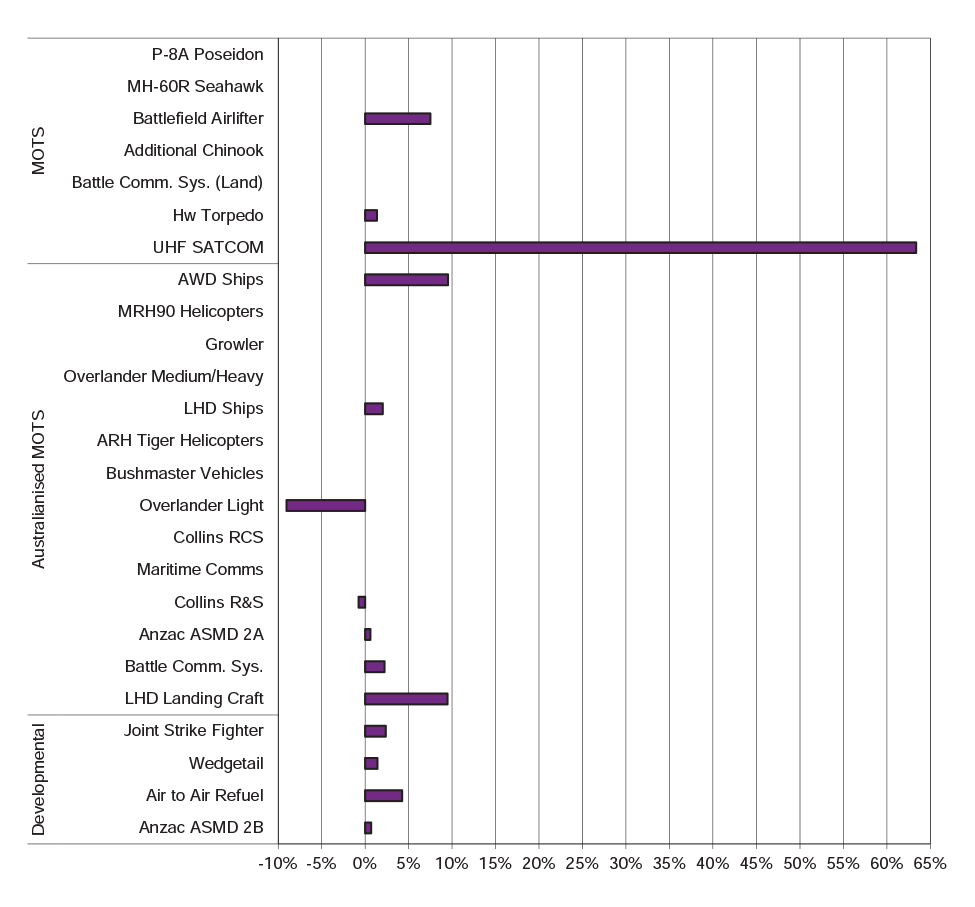

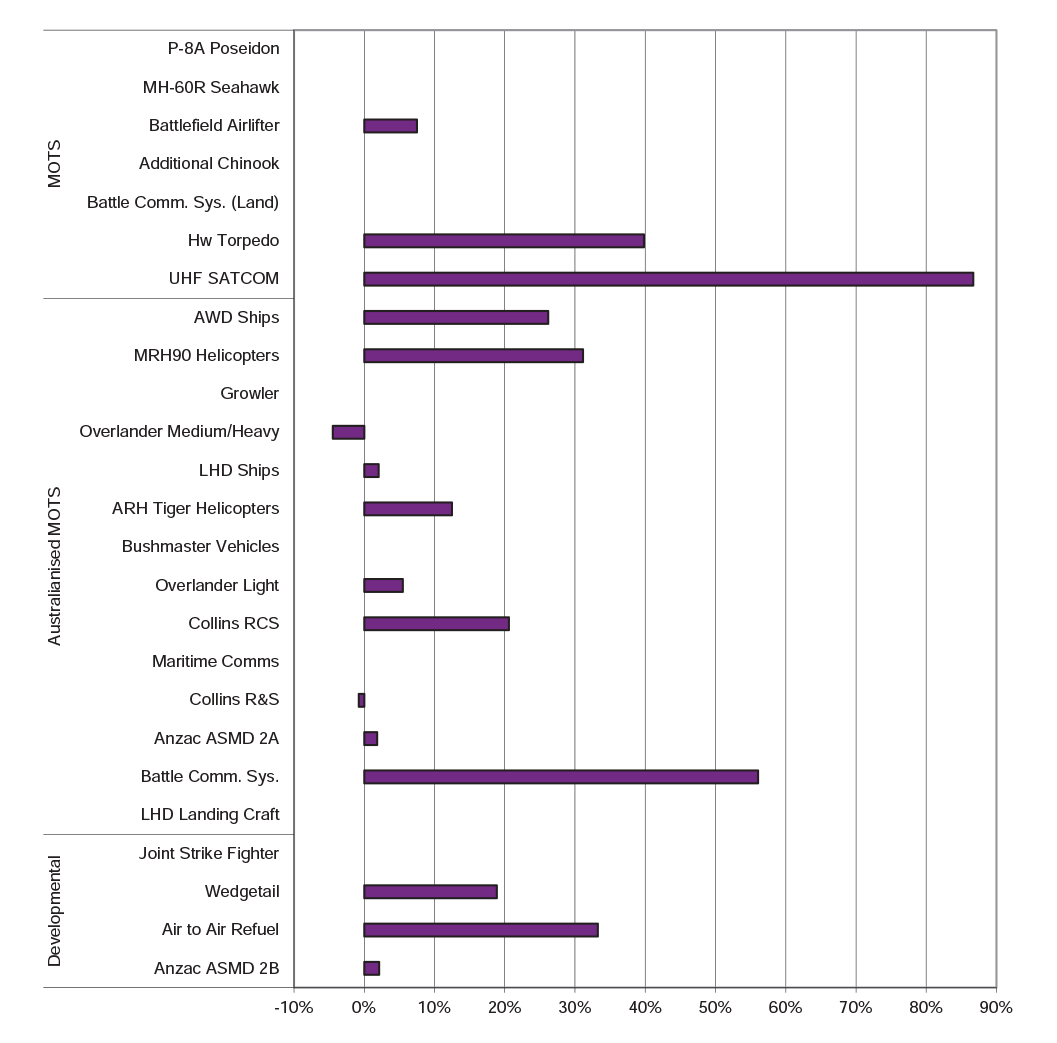

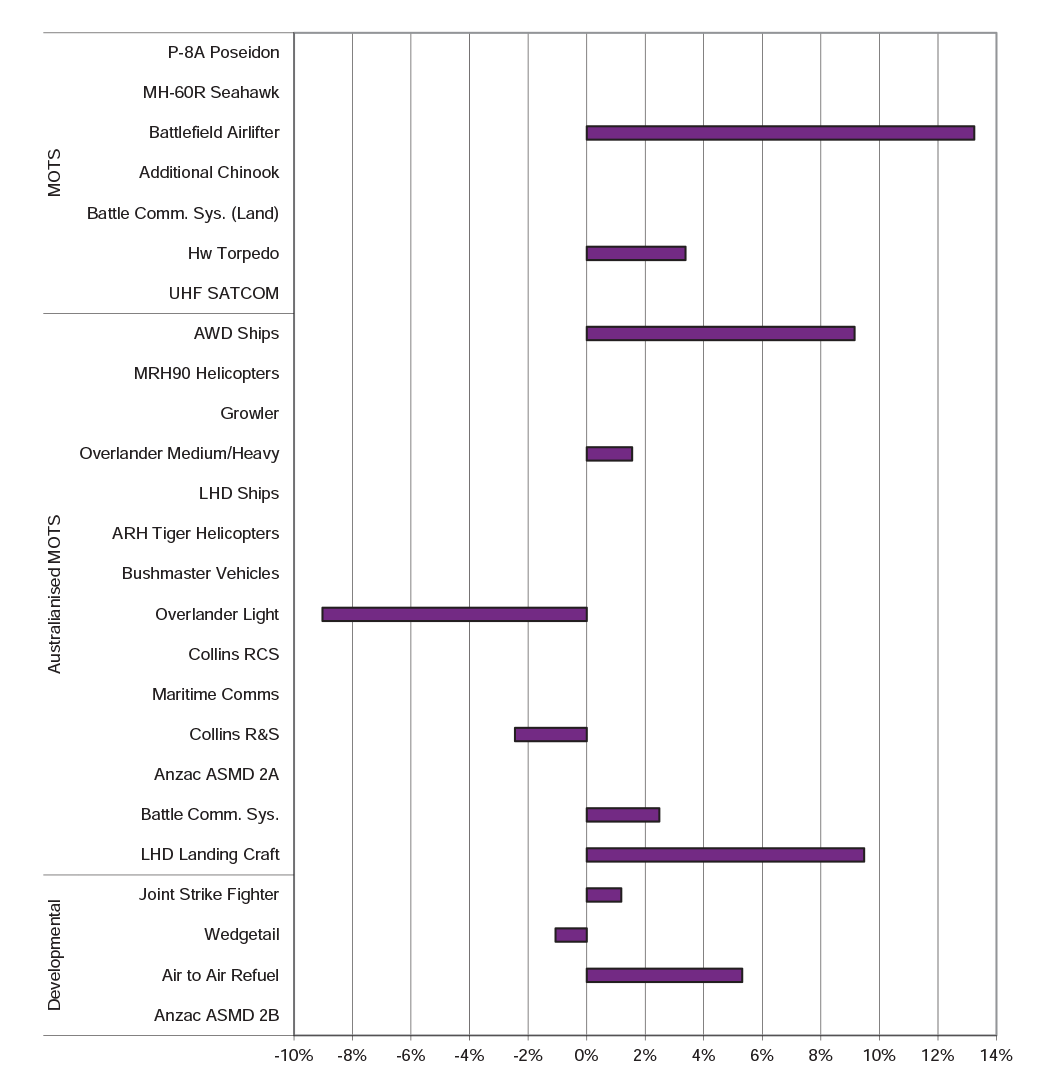

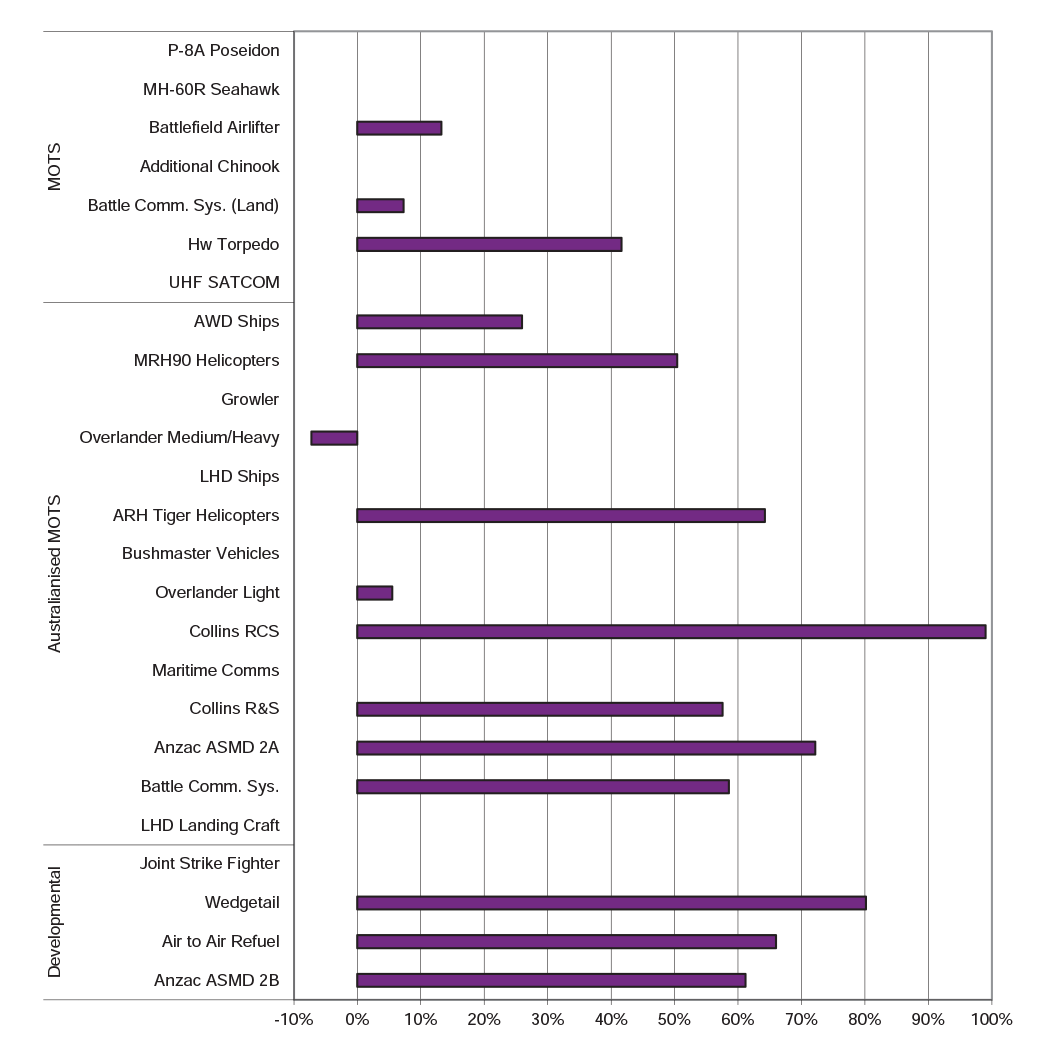

36. Additional ANAO analysis (refer to Figure 8) presents project slippage as reported in each of the eight reports against the Defence classification of projects as Military-Off-The-Shelf (MOTS), Australianised MOTS or developmental.30 These classifications are a general indicator of the difficulty associated with the procurement process. This figure highlights, prima facie, that the more developmental in nature a project is, the more likely it will result in project slippage, as well as demonstrating one of the advantages of selecting MOTS acquisitions.31 First included in the 2013–14 report, Figure 9 provides analysis of projects either completed, or removed from the review. While initial suggestions by Defence were that analysis in Figure 8 did not allow for future slippage in MOTS projects, Figure 9 shows that MOTS acquisitions assist in reducing schedule slippage.

37. It should also be noted that the impact of a MOTS focused acquisition strategy has received significant attention since the inception of the 2007–08 review and Figure 9 shows the benefit of collating data over a consistent portfolio of projects across time, to allow the longitudinal analysis first sought by the JCPAA. Further development and results in this area will be covered in the 2015–16 report.

38. The reasons for schedule slippage vary but primarily reflect the underestimation of both the scope and complexity of work, particularly for Australianised MOTS and developmental projects (see paragraphs 2.29 to 2.31 in Part 2).

Capability

39. The third major aspect of project performance examined in this report is progress towards the delivery of capability required by government and specified by the Australian Defence Force. Assessment of expected capability delivery by Defence is outside the scope of the Auditor-General’s formal review conclusion, but is included in the analysis to provide an overall perspective of the three major components of project performance.

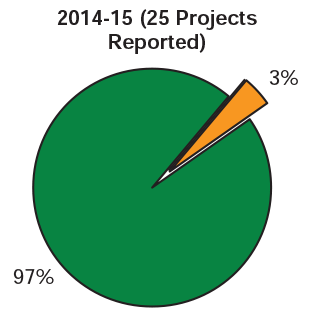

40. The Defence PDSSs reflect that the 25 projects in this year’s report will deliver all of their key capability requirements, recognising that some elements of the capability required may be under threat, but are considered manageable (assessed as either green or amber). This is consistent with the 2013–14 presentation, and reflects only one project office currently having significant challenges (2013–14: five). Refer to Table 5, below.

Table 5: Longitudinal Expected Capability Delivery

|

Expected Capability |

2012–13 Major Projects Report |

% |

2013–14 Major Projects Report |

% |

2014–15 Major Projects Report |

% |

|

High Confidence (Green) |

All Projects |

95 |

All Projects |

96 |

All Projects |

97 |

|

Under Threat, considered manageable (Amber) |

Joint Strike Fighter (Developmental) Wedgetail (Developmental) MRH90 Helicopters (AMOTS) Air to Air Refuel (Developmental) FFG Upgrade (Developmental) 155mm Howitzer (MOTS)1 |

5 |

Joint Strike Fighter (Developmental) Wedgetail (Developmental) MRH90 Helicopters (AMOTS) Air to Air Refuel (Developmental) FFG Upgrade (Developmental)2 |

4 |

Joint Strike Fighter (Developmental) |

3 |

|

Unlikely (Red) |

|

0 |

|

0 |

|

0 |

|

Total |

|

100 |

|

100 |

|

100 |

Note 1: 155mm Howitzer was removed from the MPR in 2014–15. However, the Course Correcting Fuze element of the project has been transferred to another project and will be delivered by LAND 17 Phase 1C1 Lightweight Howitzer.

Note 2: FFG Upgrade was removed from the Major Projects Report in 2014–15 prior to achieving Final Operational Capability.

Source: PDSSs in published Major Projects Reports.

41. However, the results of analysis by the ANAO show that some project managers may have taken different perspectives in assessing future achievements in relation to delivering final capability. For example, the ARH Tiger Helicopters project, faces significant capability risks and issues in relation to delivering the required Rate of Effort (flying hours), and technological obsolescence caused by delays in delivery, which impact future use. The expected impact of these risks and issues has not translated into Defence’s assessment of future capability performance, although it could reasonably be assumed to have a long term capability effect.

42. Similarly, the initial results of testing for the LHD Landing Craft project, highlight issues of significance to be addressed prior to project conclusion, not disclosed as impacting expected capability delivery. This is reflective of reporting against arrangements, post government approval, where responsibilities have been allocated within the acquisition and capability delivery framework, to the Chief of Navy post FMR (see also paragraph 2.60).

43. This year, as reported by Defence, the delivery of only three per cent (2013–14: four per cent) of the key capabilities is considered to be under threat but manageable, which as noted above, may be overly optimistic. The project with some elements under threat but considered manageable is Joint Strike Fighter. Further details are outlined at paragraph 2.65.

44. In addition to expected capability delivery, Defence has continued the practice of including declassified information on settlement actions for projects, in the interests of providing greater transparency to readers of this report. As well as prior settlements for projects included in this report32, in 2014–15, five project offices reported receiving goods and services as a result of liquidated damages. These are LHD Ships33, ARH Tiger Helicopters34, Air to Air Refuel35, Maritime Comms36 and Battle Comm. Sys.37

Developments in acquisition governance (Chapter 3)

45. Consistent with previous years, developments in acquisition governance processes are covered in the ANAO’s review, with general indications of positive impacts from some of the more recent initiatives. As might be anticipated, while some initiatives continue to mature, others require further progress prior to achieving their intended impact. These developments broadly relate to the following key acquisition governance areas.

Gate Review Boards

46. First introduced in 2008, the Gate Review (acquisition) process38 was designed to provide the Senior Executive with assurance that all identified risks for a project are manageable, and that costs and schedule are likely to be under control prior to a project passing various stages of its life cycle. The Gate Review process continues to evolve, with additional types of Gate Reviews introduced in 2013–14, as fewer acquisition projects will be eligible for (acquisition) Gate Reviews, and more projects are transferred into sustainment. These include Project Initiation Gate Reviews, Acquisition and Support Concept Gate Reviews (pre First Pass), and Sustainment Gate Reviews. The introduction of Sustainment Gate Reviews in particular, provides continuing oversight of sustainment capabilities, which was previously not available.

Projects of Concern

47. First established in 2008, the Projects of Concern process was implemented to focus the attention of the highest levels of government, Defence and industry on remediating problem projects. The process has continued to play an important, although limited role, across the portfolio of MPR projects. As at 30 June 2015, two MPR projects were continuing projects of concern: AWD Ships and MRH90 Helicopters. The Air to Air Refuel project was removed from the Projects of Concern list in March 2015.

Quarterly Project Performance Report

48. The Quarterly Project Performance Report (QPPR) was implemented in 2014 to replace the Early Indicators and Warnings system (first announced in May 2011), to identify problems with projects in the formative stages of the life cycle. The QPPR aims to provide senior stakeholders within government and Defence with a clear and timely understanding of key risks facing projects, and their progress against cost, schedule and capability performance. In 2014–15, the QPPR identified three MPR projects for continuing underperformance: Battlefield Airlifter, Overlander Light and UHF SATCOM. The Overlander Light project was removed from the list of underperforming projects in the April–June 2015 QPPR. The ongoing issues highlighted for Battlefield Airlifter and UHF SATCOM align with the results of the ANAO’s review, where delays to progress have impacted the delivery schedule of the two projects.

Joint Project Directives

49. There has been a longstanding issue for Defence in maintaining complete and accurate records of government approvals for Major Projects39, which led to the development of Joint Project Directives (JPDs). The implementation of JPDs is intended to provide an appropriately declassified means of promulgating, accurately and completely, the details of project approvals by government.

50. The introduction of a requirement for JPDs40 in 2009–10, for all projects approved by government from March 2010, is maturing and expected to have a greater influence over the portfolio of MPR projects in future years. To date, all of the eleven MPR projects, approved from 1 March 2010, have completed a JPD.41 The ANAO will continue to take JPDs into account in its review program in future years, where these have been prepared. However, this will be dependent on the completeness and accuracy of JPDs, in relation to recording the detail of government approvals.

Business systems rationalisation

51. Defence’s business systems42 rationalisation is aimed at consolidating processes and systems in order to provide a more manageable system environment. The new Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group’s Business Information Management Branch advised that it is making progress in this area through the development of an Integrated Project Management System, which was being progressively built into the then DMO corporate data warehouse in 2014–15.

Project management and skills development

52. Project management and skills development within Defence and the Defence Industry is a key challenge for the Government and industry alike. Over the last decade, more than $300 million has been provided by government to assist with professionalising Defence staff and up-skilling participants within the Defence Industry. While it is widely believed that Defence activities have increased professional competencies held by Defence staff, the measurement of the impact within industry has been limited. The ANAO will continue to review project management and skills development programs in the 2015–16 MPR.

53. Consistent with previous years, the ANAO’s detailed assessment of these governance initiatives is contained in Chapter 3 of Part 1.

1. The 2014–15 Major Projects Review

Introduction

1.1 This chapter provides an overview of the 2014–15 Major Projects Report (2014–15 MPR) review’s scope and approach, implemented by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) for the review of the Project Data Summary Sheets, and the subsequent results of the MPR review.

1.2 During the 2014–15 review period the Government released the First Principles Review: Creating One Defence (First Principles Review), a major government review of the Australian Defence Organisation. As a result, the Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO), the focus of the majority of this review, was delisted from 1 July 2015, and merged back into the Department of Defence (Defence).

1.3 The re-merger of the DMO, a large project management organisation, into the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group of Defence, is complex, and expected to take time to fully complete. Consequently, broader managerial changes are in the process of being developed and implemented within Defence, at the time of this report. The ANAO has referred to the effects of the change process where appropriate, however, the development and implementation of changes within Defence following the recommendations of the First Principles Review are not expected to be completed until 2017–18.

The impact of the First Principles Review on materiel acquisition

1.4 The First Principles Review was released on 1 April 2015. The First Principles Review is the thirty-sixth substantive government review of Defence since the 1973 Tange Review, Australian Defence, Report on the reorganistion of the Defence group of departments.43 The First Principles Review’s approach to reforming Defence includes addressing ‘waste, inefficiency and rework’44 by looking holistically at Defence’s business structures, materiel acquisition and sustainment capability, and the efficiency and effectiveness of practices within the department.

1.5 The review made 76 recommendations, and supports a business model which is comprised of three identifiable key features:

- a stronger and more strategic centre within the department;

- an end-to-end approach for capability development with Capability Managers assigned clear authority and accountability; and

- enablers that are integrated and customer-centric.45

1.6 The First Principles Review has recommended that the DMO’s functions, with part of the Capability Development Group’s previous responsibilities46 be remerged into the Department of Defence in the newly created group, led by a single Deputy Secretary, who reports directly to the Secretary of Defence. The appointment of the permanent Deputy Secretary of the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group, occurred on 31 August 2015. Defence has provided advice on impacts to their organisation as a result of the First Principles Review in Part 2.

Review scope and approach

1.7 In 2012 the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) identified the review of the Project Data Summary Sheets (PDSSs) as a priority assurance review under section 19A(5) of the Auditor-General Act 1997, providing the ANAO full access to the information gathering powers under the Act. The ANAO’s review of the individual project PDSSs, which are contained in Part 3 of this report, was conducted in accordance with the Australian Standard on Assurance Engagements (ASAE) 3000 Assurance Engagements Other than Audits or Reviews of Historical Financial Information issued by the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards Board. In addition, and for the first time in 2014–15, review of the project financial assurance statement, included within each PDSS, has been included in the scope of the Independent Review Report by the Auditor-General. See paragraph 1.23 below, for more detail.

1.8 Excluded from the scope of the ANAO’s review is PDSS data on the identification of Risks and Issues, the Measures of Materiel Capability Delivery Performance, and ‘forecasts’ of future dates and the achievement of future outcomes, due to the lack of a system or systems from which to provide complete and accurate evidence47, in a sufficiently timely manner to complete the review. Accordingly, the Independent Review Report by the Auditor-General does not provide any assurance in relation to this information.

1.9 While the ANAO’s work is appropriate for the purpose of providing an Independent Review Report in accordance with ASAE 3000, the review of individual PDSSs is not as extensive as individual performance and financial statements audits conducted by the ANAO, in terms of the nature and scope of issues covered, and the extent to which evidence is required by the ANAO. Consequently, the level of assurance provided by this review in relation to the 25 Major Projects is less than that provided by our program of audits.

1.10 However, the Major Projects Report examines systemic issues and provides longitudinal analysis for the 25 projects reviewed, and may also reflect on, or have implications for, general project management practices, including overall performance, or financial matters.

1.11 The review was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $2.2 million.

Areas of review focus

1.12 The ANAO’s review of the information presented in the individual PDSSs included:

- examination of each PDSS and the documents and information relevant to them;

- review of relevant processes and procedures used in the preparation of the PDSSs;

- assessment of the systems and controls that support project financial management, risk management, and project status reporting;

- interviews with persons responsible for the preparation of the PDSSs and those responsible for the management of the 25 projects;

- taking account of industry contractor comments provided to the ANAO and Defence regarding draft PDSS information;

- assessing the assurance by Defence managers attesting to the accuracy and completeness of the PDSSs;

- examination of the representations by the Chief Finance Officer of Defence supporting the project financial assurance and contingency statements, and the independent third-party review of the project financial assurance statements;

- examination of representations, provided by the Capability Managers, relating to each project’s progress toward Initial Materiel Release (IMR) and Final Materiel Release (FMR), and Initial Operational Capability (IOC) and Final Operational Capability (FOC); and

- examination of the ‘Statement by the Secretary of Defence’, including significant events occurring post 30 June, and any supporting management representations.

1.13 The ANAO’s processes and procedures to provide independent assurance over the PDSSs also focused on reviewing project management and reporting arrangements in place that contribute to the overall governance of Major Projects. These included:

- the financial framework, particularly as it applies to the project financial assurance and contingency statements and managing project budgets in the out-turned budget environment (Section 2 of the PDSSs);

- schedule management and test and evaluation processes (Section 3 of the PDSSs);

- the capability assessment framework, as it relates to Defence’s evaluation of the likelihood of delivering key capabilities (Section 4 of the PDSSs);

- ongoing review of the implementation of the Enterprise Risk Management Framework and major risk and issue data (Section 5 of the PDSSs);

- the project maturity framework and reporting and the systems in place to support the provision of this data (Section 6 of the PDSSs); and

- developments in the areas of acquisition governance (Chapter 3 in Part 1).

1.14 This review informed the ANAO’s understanding of the systems and processes supporting the PDSSs for the 2014–15 review period, and highlighted issues in those systems and processes that could be beneficially addressed in the longer term.

Results of the review

1.15 The following sections outline the results of the ANAO’s review, which contribute to the overall conclusion in the Independent Review Report by the Auditor-General for 2014–15.

Financial framework

1.16 The project financial assurance statement was introduced in the 2011–12 Major Projects Report and the contingency statements were introduced for the first time in the 2013–14 report. Together, they are aimed at providing greater transparency of projects’ financial status in the out-turned environment, following the move to out-turned budgeting in 2010, and highlight the use of contingency funding to mitigate projects risks.

1.17 In 2013–14, the ANAO reviewed the financial framework, as it applied to managing project budgets and expenditure in the out-turned budget environment, although the project financial assurance statements were formally excluded from the scope of the review and the Independent Review Report by the Auditor-General. The review indicated that all project offices expected to deliver all required capabilities within the allocated budget. However, for AWD Ships, the CEO DMO indicated that the project may have insufficient approved funds to complete the program.48

1.18 In addition, in 2013–14, a number of project offices added additional disclosures to their PDSSs, and in particular, AWD Ships, LHD Ships and ANZAC ASMD Phase 2B, recognised that available funding for price indexation was a key concern. Prior to 1 July 2010, projects were periodically supplemented for price indexation, whereas the allocation for price indexation is now provided for on an out-turned basis at Second Pass Approval.49 This change in supplementation policy has meant that price Indexation has emerged as a risk for some projects, which is required to be managed individually, by each project office.

1.19 In effect, projects which slip past original delivery dates must now access contingency funding where pre-calculated indexation is insufficient. Previously, the separation of yearly indexation funding from other budget components allowed for greater transparency in reporting and fewer risks for project offices to manage.50

1.20 A project’s total approved budget comprises:

- the programmed budget, which covers the project’s approved activities, for both contractual and departmental aspects of each project; and

- the contingency budget, which is established to provide adequate budget to cover the inherent cost, schedule and technical risks involved in managing complex acquisitions.51

1.21 The then DMO’s management of financial risk was based on a portfolio management approach, within the responsibilities of the Chief Finance Officer of DMO (refer to paragraph 1.12 in Part 2 of the 2011–12 Major Projects Report). It is expected that Defence will review this approach as part of the implementation of the First Principles Review, and the ANAO will consider any proposed or implemented changes in 2015–16.

1.22 In 2014–15, the ANAO reviewed the financial framework as it applied to managing project budgets and expenditure, including contingency, in the out-turned budget environment, and the project financial assurance and contingency statements.

Project financial assurance statement

1.23 The project financial assurance statement was added to the PDSSs to provide readers with an articulation of a project’s financial position in relation to delivering project capability and to provide transparency in regard to whether there is ‘sufficient remaining budget for the project to be completed’.52

1.24 In 2014–15, while most projects again continued to operate within their total approved budget, the AWD Ships, LHD Ships and ANZAC ASMD 2B project offices continued to recognise that available funding may be insufficient as contracted indices escalation may be greater than the approved project budget. The AWD Ships53 project also included reference in its project financial assurance statement to the announcement by the Ministers for Finance and Defence on 22 May 2015, that the project would require an additional $1.2 billion to be completed, and that this would be funded at the expense of other Defence acquisitions.54 The 2014–15 Statement by the Secretary of Defence disclosed the approval of this real cost increase by government in July 2015. In addition, Battlefield Airlifter disclosed a cost risk for contracts yet to be executed.

1.25 As noted previously, for the first time in 2014–15, the ANAO has included the project financial assurance statements within the scope of the Independent Review Report by the Auditor-General, reflecting the increased level of confidence sought by stakeholders in the accuracy and completeness of the related disclosures and the work completed by the ANAO and the then DMO in this area, since the introduction of the statement.

1.26 Defence has continued to support the project financial assurance statements with an independent third-party review, which considered the following in selecting the review sample: remaining budget, Projects of Concern listing, complexity, diversity across divisions and past history. This independent review remains critical to the ongoing validation of the project financial assurance statements.

1.27 In reality, until systems and processes are improved, from end-to-end in the project acquisition life cycle, the ANAO’s assurance in this area will remain one of the higher risk elements of the review. For example, while Joint Project Directives55 mature and until they can be relied upon to completely and accurately reflect the approval outcome of government, the ANAO will require access to original approval documents to validate the requirements of projects. At this time, validation by internal Defence documentation is not always possible.

1.28 In addition, the current status of performance information, including for contingency management, project maturity scores, and capability delivery (excluded from the scope of this review) are being impacted by inconsistent application and supporting systems, and lack of management review. All of the above are discussed in more detail elsewhere in this report, and directly relate to the validation of expected project delivery, within budget.

1.29 Projects selected for the 2014–15 third-party review, in support of the financial assurance statement assurance process included:

- detailed review—ANZAC ASMD 2B and ANZAC ASMD 2A; and

- compliance review—P-8A Poseidon, MRH90 Helicopters and Maritime Comms.

1.30 Observations from the review included that there were inconsistent approaches to the weighting of risks and assigning of contingency against risks, with only two of the five project offices being assessed as compliant with the Defence Materiel Instruction for project financial assurance statements.56 However, it was determined that the three project offices in question had sufficient contingency despite this non-compliance and that price escalation risk was manageable for ANZAC ASMD 2B. The ANAO’s review also noted a number of issues in terms of compliance with Project Risk Management Manual version 2.4 across project offices, which have been reported to management.

1.31 In conclusion, while for the 2014–15 Major Projects Report, the Chief Finance Officer’s representation letter to the Secretary on the project financial assurance statements was unqualified (except for the known injection of $1.2 billion required for AWD Ships and the affordability risk for Battlefield Airlifter), the project financial assurance statement is restricted to the current financial contractual obligations of Defence for these projects, including the result of settlement actions and the receipt of any liquidated damages; and current known risks and estimated future expenditure as at 30 June 2015.

Contingency statements and contingency management

1.32 As noted above, the 2013–14 Guidelines introduced the requirement for a ‘contingency statement’ within each PDSS. PDSSs are now required to include a statement as to whether contingency funds have been applied during the year, as well as disclosing the risks mitigated by the application of those contingency funds. The five project offices which had contingency funds applied in 2014–15 were AWD Ships (indexation funding shortfall and Counter Measure Lockers for storing explosive ordnance), MRH90 Helicopters (technical and integration risks), ARH Tiger Helicopters (for discounts on upgrades to Ground Mission Equipment received as liquidated damages), Air to Air Refuel (risks related to the modification program and spares) and Battlefield Airlifter (divestiture and contracting risk).57

1.33 The examination of the contingency statements as at 30 June 2015 also highlighted that:

- where project offices had contingency funds applied, the purpose was within the approved scope of the project;

- the clarity of the relationship between contingency application and identified risks varied. Of the 24 project offices that have a formal contingency allocation58, two did not explicitly align their contingency log with their risk log, and of the 22 project offices that could demonstrate alignment, 10 did not always meet all the requirements of Project Risk Management Manual (PRMM) version 2.4; and

- the method for applying contingency varied, with only four project offices using the ‘expected costs’ of the risk treatment (as required by PRMM version 2.4), seven for which no application of contingency was necessary (as there were no high/extreme risks or no cost implications), and the remaining 13 using either a proportionate allocation of the likelihood of the risk eventuating (the method outlined in PRMM version 2.2), an alternate method, or having no application of contingency against risk.

1.34 Although the ANAO found that all project offices tracked their contingency budget in some form, the methods of recording the balance of contingency budgets and application of contingency funds differed between projects. For example, project offices varied in whether they maintained an up to date record of reviews of their contingency log, and its adequacy, or included the expected cost for all high/extreme risks in the risk log with corresponding entries in the contingency log, or risk identifiers and descriptors for allocations of their contingency budget, all of which are requirements outlined in PRMM version 2.4.

1.35 The purpose of the project contingency budget is identified as being ‘to provide adequate budget to cover the inherent risk of the in-scope work of the project’.59 Defence policy requires project offices to maintain a contingency budget log to identify and track components of the contingency budget. However, the lack of oversight of compliance with this policy has resulted in inconsistent approaches taken to contingency allocation. For example, in 2014–15, the ANAO observed that half of the project offices were unable to demonstrate clear links in compliance with PRMM version 2.4 for the contingency allocation to individual risks.

Enterprise Risk Management Framework

1.36 In 2013–14, the ANAO’s review concluded that while the standards of risk management arrangements applying to Major Projects have continued to improve, the inherently uncertain nature of risks and issues meant that PDSS data could not be considered complete due to unknown risks and issues that may emerge in the future. In 2014–15, major risks and issues data in the PDSSs continues to remain out of scope of the Independent Review Report by the Auditor-General under arrangements for the priority assurance review, but is included in the analysis to provide an overall perspective of how risks and issues are managed within Defence.

1.37 The ANAO monitors developments in risk management at the enterprise and project level, in order to maintain its understanding of the new Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group’s risk management systems and processes. Organisationally, the development of the former DMO’s Enterprise Risk Management Framework, was identified by the ANAO in 2008–09, as a challenging but necessary step for the then DMO in achieving its goal of improving project management.60 In 2014–15, the ANAO again monitored the progress of the Enterprise Risk Management Framework and its associated policies and guidance, which continues to mature.

1.38 Finalised in July 2014, Defence conducted an internal audit on Risk Management and the Enterprise Risk Management Framework in Defence. With a broader scope than the ANAO’s examination of project level risk management, the findings of the audit were as follows:

- risk management in Defence is inadequately mandated and implemented and also has deficient senior ownership;

- risk management in Defence is inadequately integrated with other Defence processes61;

- the enterprise risk deep dive process is incomplete and the enterprise risks are not widely communicated or fully understood;

- the application of risk management in Defence is inconsistent, lacks quality and fails to cascade through the organisation; and

- many Defence risk managers are inadequately and inconsistently skilled.62

Defence advised in August 2015 that work on the Enterprise Risk Management Framework continues in the new Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group.

1.39 The Interdependent Mission Management System (IMMS) was developed in response to a recommendation from the 2011 Plan to Reform Support Ship Repair and Management Practices (Rizzo Report) to ‘establish an integrated risk management system’.63 The Rizzo Report stated that in relation to risk management, ‘Navy and DMO need to improve coordination and integrate their interdependent activities more effectively’.64 The IMMS is intended to provide joint visibility of risks at the enterprise level, and facilitate greater accountability in relation to risk management. Following the Navy Reform Board’s May 2014 endorsement of the use of IMMS to manage interdependent risks in Navy, in January 2015, a Materiel Sustainment Agreement65 was signed between Navy and the then DMO, providing the governance framework for interdependent risk management. Currently, IMMS is in the pilot stage with the Guided Missile Frigate (FFG) System Program Office, with final testing forecast for completion in October 2015.66

1.40 In 2014–15, the ANAO again examined project offices’ risk and issue logs, which are created and maintained utilising the new group’s mandated Excel or Predict! software.67 The ANAO’s review indicates that the majority of project offices maintained risk and issue logs appropriately, but not consistently. The ANAO has continued to note inconsistencies in the practices of various project offices, including:

- where Excel and Predict! logs are maintained concurrently for the same project, risks are not always consistently recorded; and

- where Excel is used, there is variability in the information content of the log and in some cases, evidence that it has not received appropriate management attention.

1.41 While some project offices will experience greater challenges with risks and issues administration, considering project complexity, scale and timing, it is important that Defence provide systems and processes to ensure risks are appropriately managed and reviewed across the life of the project. Large complex projects, which are more likely to have a higher number of risks and issues, face the challenge of putting internal systems in place to meet organisational requirements. Particularly in the case of higher cost developmental projects, which also tend to exist in an environment of often considerable scrutiny and political risk.

1.42 In this context, the Joint Strike Fighter project is an example where the project has developed a hierarchical view of risks, due to the number of risks in existence. For example, the project has 51 ‘high’ rated risks (pre-mitigation). By necessity, these are summarised in the Joint Strike Fighter PDSS at a strategic level. However, consideration of the Joint Strike Fighter’s risks is made more difficult given that the project has not finalised its Risk Management Plan, which has remained in draft since 2014.

1.43 Smaller projects, while typically having fewer risks and issues, also have fewer and less experienced staff, and are less likely to have experienced dedicated risk managers as part of their staffing profile. The Battlefield Airlifter project is an example where the ANAO was provided with both Predict! and Excel risk logs, which were inconsistent.

1.44 Overall, the issues with risk management that the ANAO observed related to:

- variable compliance with corporate guidance to ensure complete, timely and accurate representation of project risks and issues;

- the currency of Risk Management Plans and the frequency of their update to capture changes in policy and practice68;

- the frequency with which risk and issue registers are reviewed to ensure risks and issues are appropriately managed and reported to senior management; and

- risk management logs and supporting documentation of variable quality, particularly when Excel is used.

1.45 The Standardisation Office is the corporate area responsible for the development, amendment and publishing of corporate risk management policy within the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group. Gate Reviews held by the Independent Project Performance Office also have a degree of oversight over project risk management processes.69 In 2014–15, both areas confirmed that they provide guidance and advice only. Neither have the mandate or resources for systematic compliance monitoring of risk management.

1.46 Since 2007–08, risks and issues have been a consistent focus of review, although excluded from the formal scope of the Independent Review Report by the Auditor-General, due to issues with completeness, supporting systems and executive oversight. Throughout this time the ANAO has identified deficiencies and worked with project offices to improve compliance with the risk management policies applicable in the then DMO. It is clear that increased scrutiny and accountability of project performance is required to identify shortcomings in corporate performance to support project offices manage their risks, and deficiencies in local project risk management performance.

1.47 To achieve greater consistency in the approach to risk management and in response to the release of a Commonwealth Risk Management Policy on 1 July 2014, the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group is developing a single Risk Management Manual, which is expected to be finalised at the end of 2015.70

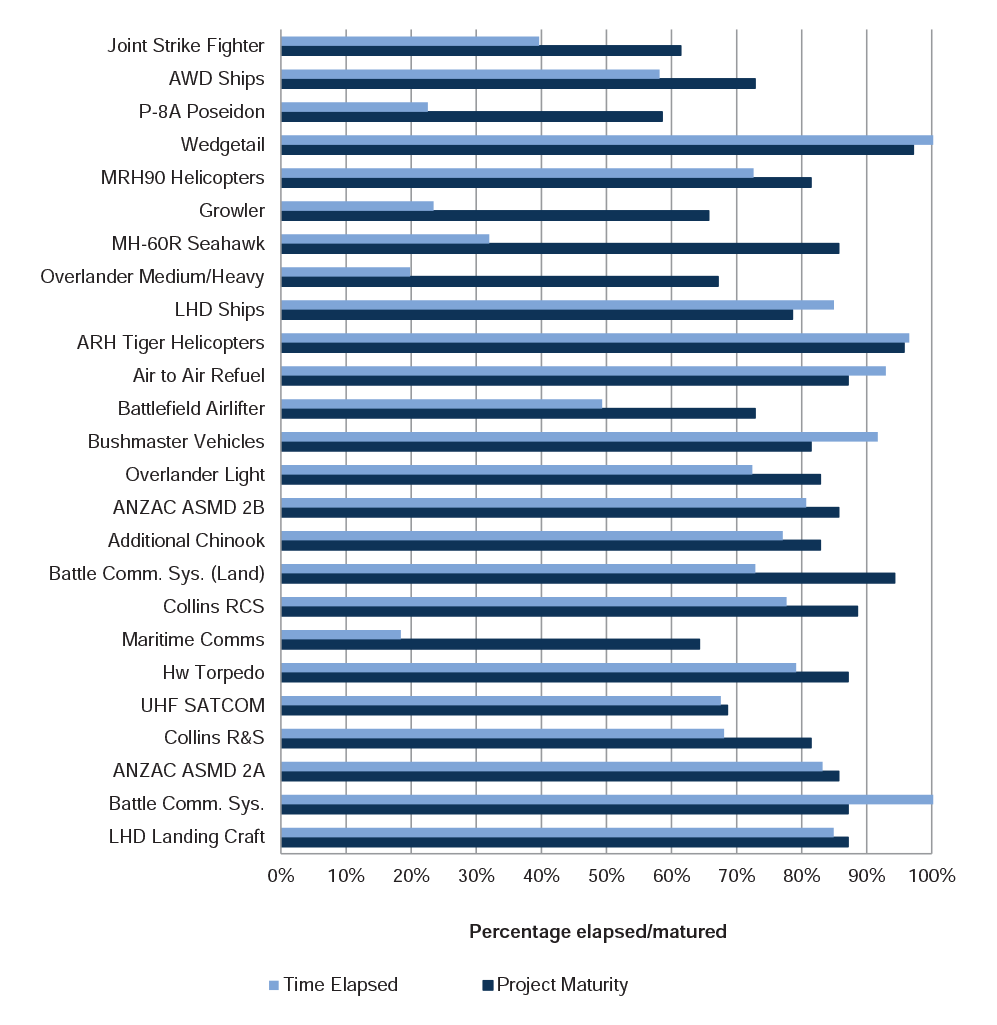

Project maturity framework

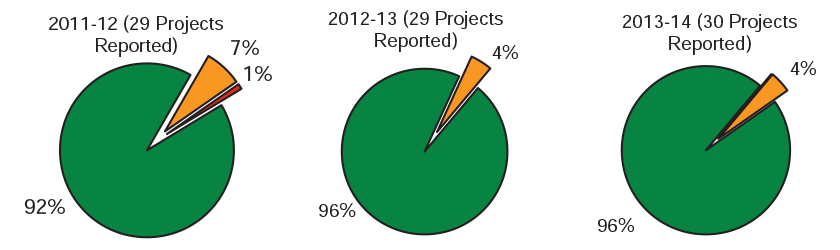

1.48 Initially introduced as Project Risk Scores in 2004, and later renamed Project Maturity Scores in 2005, they have been a feature of the Major Projects Report since inception in 2007–08. The DMO Project Management Manual 2012, defines a maturity score as:

The quantification, in a simple and communicable manner, of the relative maturity of capital investment projects as they progress through the capability development and acquisition life cycle.71

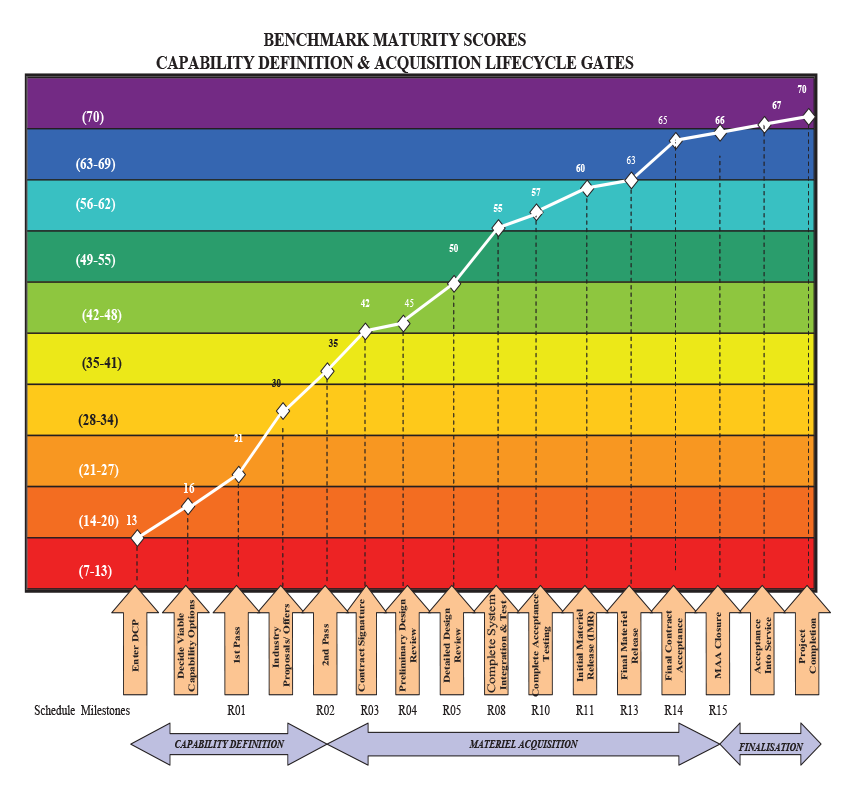

1.49 Maturity scores are a composite indicator, constructed through the assessment and summation of seven different attributes, which cumulatively form a project ‘maturity score’. The attributes are: Schedule, Cost, Requirement, Technical Understanding, Technical Difficulty, Commercial, and Operations and Support, which are assessed on a scale of one to 10.72 Project Maturity is a composite performance indicator available for all Major Projects, for decision making, and to assess their overall status.73

1.50 Historically, while the DMO had raised some doubts about the effectiveness of their maturity score framework, they agreed to retain maturity scores following a JCPAA recommendation that ‘DMO maintain the ability to publish maturity scores in future Major Projects Reports until these are no longer required by the guidelines endorsed by the JCPAA’.74 The Committee viewed the retention of maturity scores as important in relation to providing a measure of capability delivered for each project, until a measure equal to or better than current arrangements is available. Recently, the decision to maintain maturity scores, while seeking to develop an improved measure, was again reaffirmed by Defence to the ANAO in the context of this 2014–15 review.

1.51 In 2014–15, Defence also indicated that the organisation is relying less on project maturity scores and are instead moving towards other project management tools, such as the Materiel Implementation Risk Assessment (MIRA). The MIRA is used during the First Pass Approval stage for projects and is designed to assist project offices in submitting details of their top five risks in the acquisition business case for cabinet submission. The DMO Project Risk Management Manual 2013 defines MIRA as:

A summary of the most significant risks (as recorded in the project risk register) that will impact on DMO’s ability to deliver the Materiel System (Mission and Support System) outcomes on time, within budget, and to the required scope and quality.75

1.52 As the MIRA outlines a project’s key risks at only one point in time, government First Pass Approval, the ANAO notes that for reporting purposes, the MIRA does not provide the same level of oversight on a project’s delivered capability as maturity scores. During the course of the review, the ANAO reviewed the MIRA for new projects, to ensure that the risks disclosed in the MIRA were included in the project risk registers. The results of which were consistent with general alignment with current PDSS disclosures, with any differences due to the passage of time, increased project knowledge, and risk management efforts.

1.53 However, comparing the maturity score against its expected life cycle gate benchmark provides internal and external stakeholders with an indication of a project’s progress. This may trigger further management attention or provide confidence that progress against the appropriate maturity score benchmark is satisfactory.

1.54 While the ANAO has previously raised inconsistency in the application of project maturity scores as an issue, and as maintained in this review, the ANAO noted that project offices were more consistently assigning maturity scores than in previous years. While some subjectivity remains, in the context of a framework that relies upon the application of professional judgement, across a diverse range of project circumstances, with the detailed guidance available, assigning a maturity score is a repeatable process, and is appropriate for external review or audit.

1.55 As previously noted by the ANAO, the guidance underpinning the attribution of maturity scores would benefit from a review for internal consistency and relationship to the Defence’s contemporary business. For example, allocating approximately 50 per cent of the maturity score at Second Pass Approval, regardless of acquisition type, is often inconsistent with the proportion of project budget expended, and the remaining work required in order to deliver the project.

1.56 Further, the existing project maturity score model does not always effectively reflect a project’s progress during the often protracted build phase, particularly for developmental projects. During this phase it can be expected that maximum expenditure will occur, and risks realised, some of which will only emerge as test and evaluation activities are pursued through to acceptance into operational service.

1.57 Finally, while the guidance underpinning maturity scores was due for review in September 201276, this review is not yet finalised. The ANAO was advised that while work had occurred to review the guidance, the release of the First Principles Review meant that the guidance would require further consideration.

1.58 The ANAO will continue to review the framework and attribution of maturity scores in subsequent reviews.

Efficiency of the Major Projects Report process

1.59 As in previous years, project offices prepared indicative PDSSs and supporting evidence prior to 30 June 2015 to support the initial stage of ANAO fieldwork for the 2014–15 review. In general, project offices provided high quality PDSSs, with a few exceptions.

1.60 However, while more recent requirements of the review, such as the provision of the contingency statement, are still maturing, the provision of core project information on cost, schedule and the progress towards delivery of required capability, remains a largely manual process. Additionally, a significant amount of project information is not centrally maintained, requiring extensive contact with individual project offices to obtain evidence to assure the information in the PDSSs. Further, inconsistent application of Defence policies for project management increases these difficulties.77

1.61 The ANAO will continue to assess the application of policy and maintain its focus on the efficiency and consistency of the production and assurance of the PDSSs.

Review conclusion

1.62 The Independent Review Report by the Auditor-General takes into account the overall governance of Major Projects, the results of the ANAO’s examination of the then DMO’s project management and reporting arrangements, and the results of the ANAO’s substantive procedures to gain assurance in relation to key information reported in PDSSs. In 2014–15, the results of the ANAO’s priority assurance review of the 25 PDSSs, was that nothing has come to the attention of the ANAO that causes us to believe that the information and data in the PDSSs, within the scope of our review, has not been prepared, in all material respects, in accordance with the Guidelines.

2. Analysis of Projects’ Performance

Introduction

2.1 Performance information is important in the management and delivery of major Defence equipment acquisition projects (Major Projects) as it informs decisions about the allocation of resources, supports advice to government on project progress and performance, and allows for the Parliament and the public to assess the progress of projects. Project performance information has been the subject of many of the reviews of Defence and a consistent area of focus of the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) over the time of the Major Projects Report (MPR). This chapter progresses previous Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) analysis of project performance, and utilises data collected over the life of the MPR, to provide updated analysis across the portfolio of MPR projects.

Project performance analysis by the ANAO

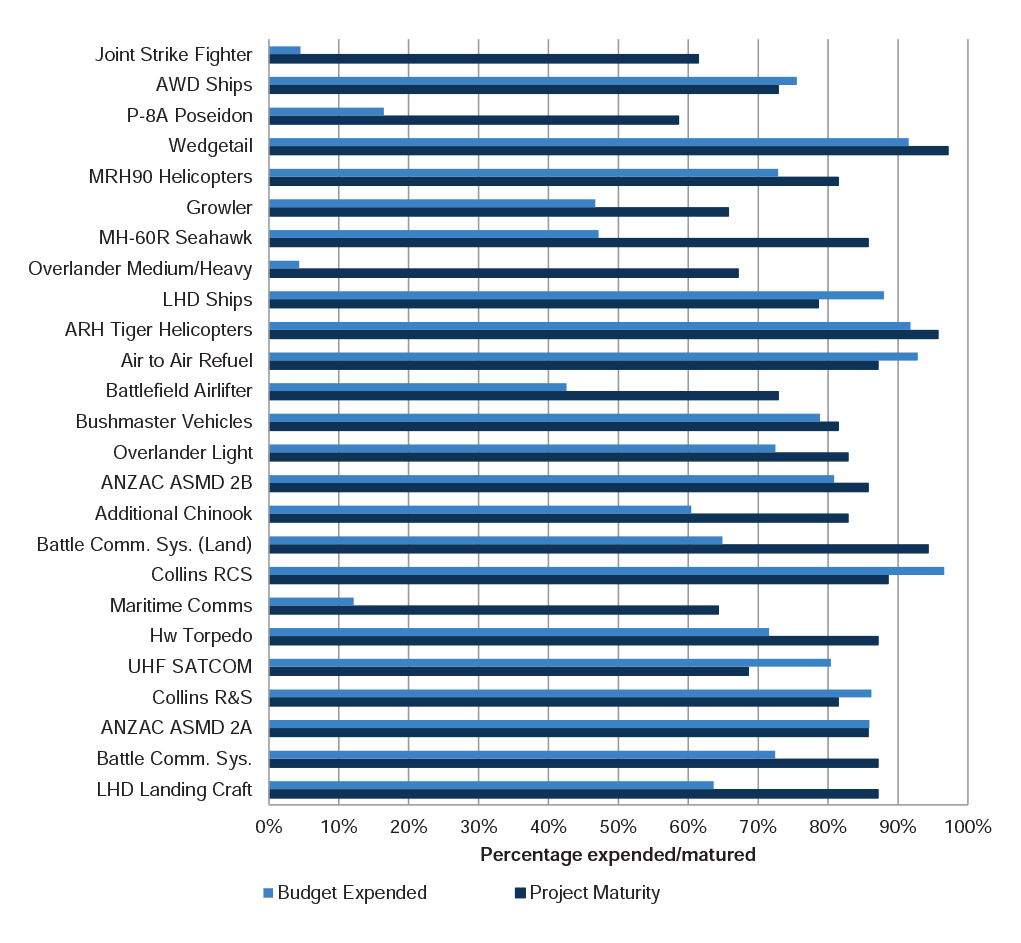

2.2 The ANAO utilises three key performance indicators to lead analysis over the three major dimensions of projects’ progress and performance against Defence’s Project Maturity scores.78 These indicators are the:

- percentage of budget expended (Budget Expended)—which measures the total expenditure as a percentage of the total current budget;

- percentage of time elapsed (Time Elapsed)—which measures the percentage of time elapsed from original approval to the forecast Final Operational Capability (FOC)79; and

- percentage of key materiel capabilities expected to be delivered (Expected Capability)—which is Defence’s assessment of the likelihood of delivering the required level of capability.

These are measured in percentage terms, to enable comparisons between projects, and to provide a portfolio view across project progress and performance.

2.3 Following this analysis, each section then provides additional analysis of each of the three major dimensions, with key in-year information, longitudinal analysis compiled since the inception of the review, and results of project progress for the year-ended 30 June 2015.

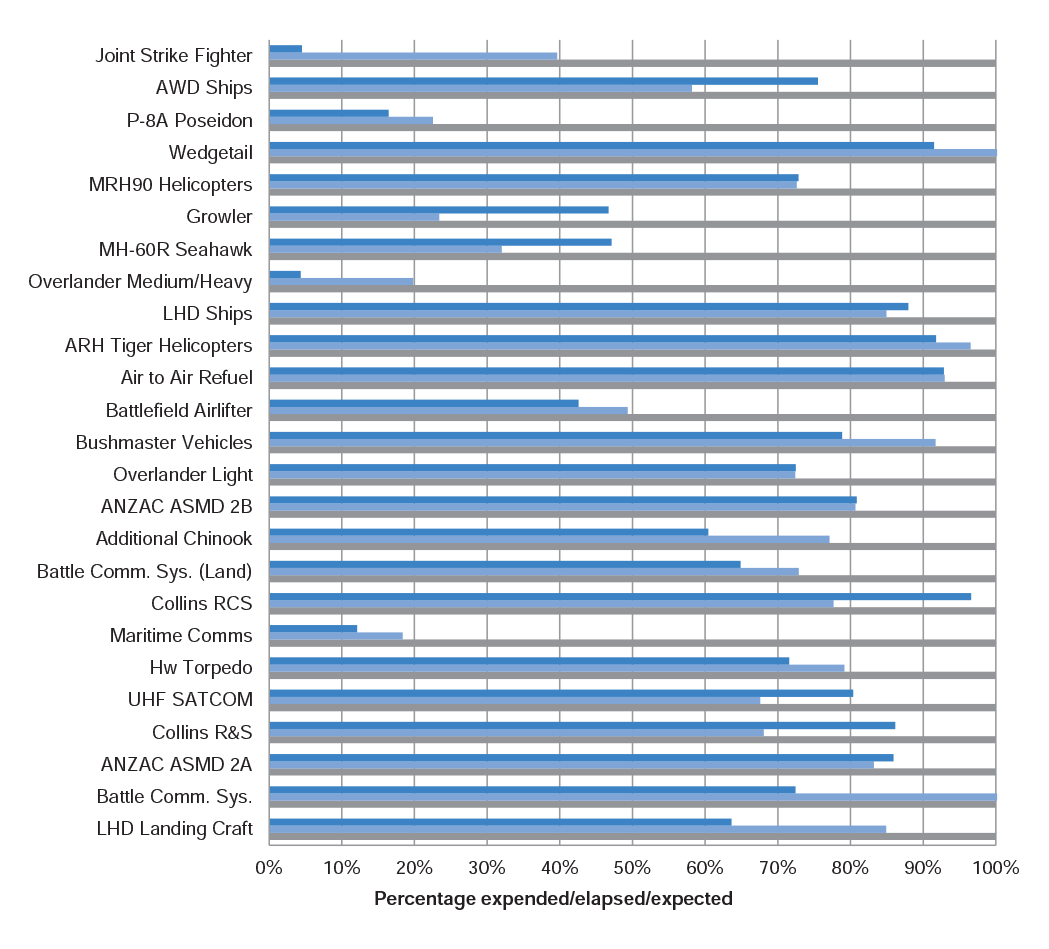

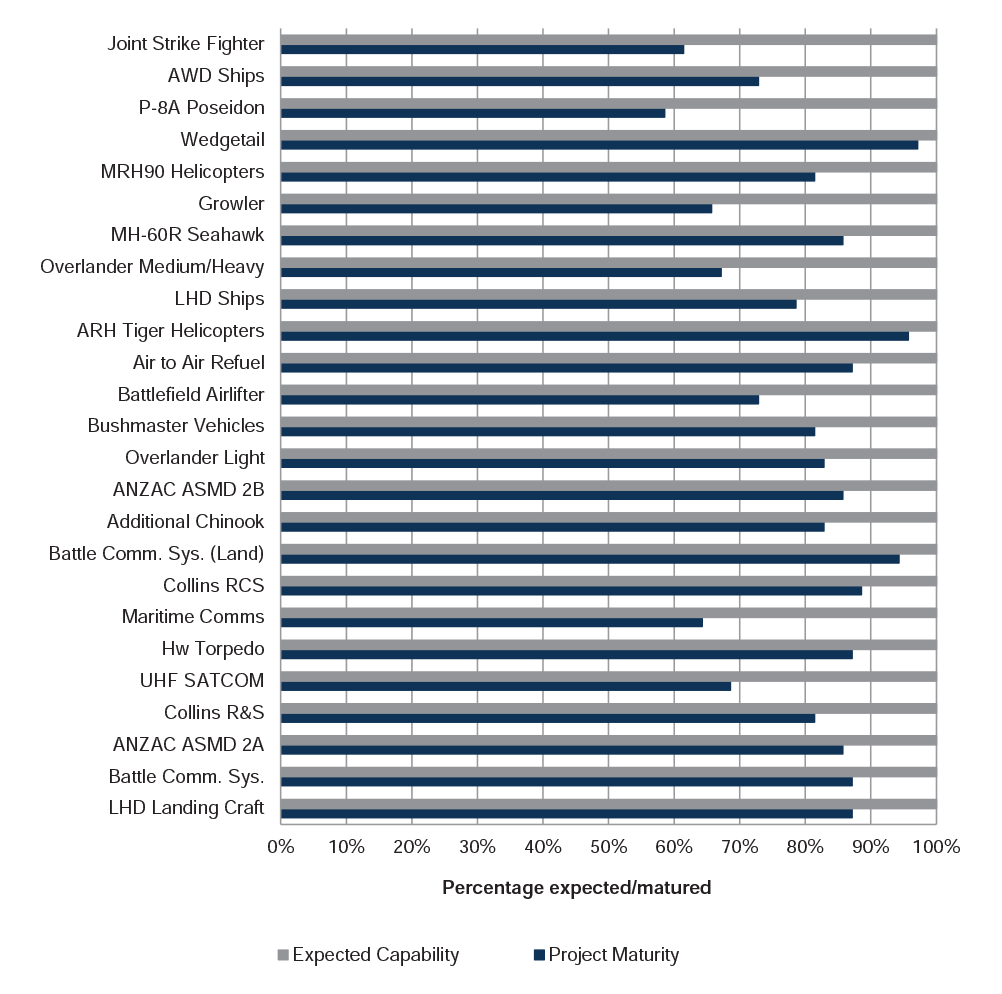

2.4 Prior to disaggregation and analysis against Project Maturity scores, Figure 2 below, provides an overview of the three major dimensions of project performance, and sets out Budget Expended, Time Elapsed80 and Expected Capability.81

Figure 2: Budget Expended, Time Elapsed and Expected Capability

Note: The Expected Capability for Wedgetail has been assessed against the Supplies section of the Materiel Acquisition Agreement, which lists the equipment to be delivered.

Source: The ANAO’s analysis of Budget Expended and Time Elapsed of the 2014–15 PDSSs. Refer to paragraphs 2.4 to 2.9 in Part 1 of this report. Expected Capability is as presented in the PDSSs.

2.5 The figure shows that for most projects (19 of 25), Budget Expended is broadly in line with, or lagging, Time Elapsed.82 This relationship is generally expected in an acquisition environment predominantly based on milestone payments. However, due to the varying complexities, stages and acquisition approaches across the portfolio of projects, further analysis of these simple performance measures provides an overall picture of key variances.

2.6 Where Budget Expended is lagging Time Elapsed the project schedule may be at risk or milestones not met. For example, projects where the Budget Expended is approximately 20 per cent less than the Time Elapsed, include: