Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Reporting on Governing Boards of Commonwealth Entities and Companies

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Summary

1. Most corporate Commonwealth entities (CCEs), some non-corporate Commonwealth entities (NCEs) and all Commonwealth companies are governed by a group of persons described as a ‘board’. The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 mandates the reporting of information relating to the membership of governing boards through entities’ annual reports and the Department of Finance’s Transparency Portal (refer Table 3.1).

2. Section 25 of the Auditor-General Act 1997 enables the Auditor-General at any time to cause a report to be tabled in either House of the Parliament on any matter. This is the first information report prepared by the ANAO on the governing board membership of Commonwealth entities (CCEs and NCEs) and companies. The objective of this information report is to provide transparency and insights on the governing boards of Commonwealth entities and companies and the membership of these boards.

3. The data used for this report is primarily based on information sourced from relevant Commonwealth entities’ and companies’ annual reports from 2018–19 to 2020–21. In compiling this report, the ANAO also drew upon other data sources (refer Table 1.1).

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Commonwealth entities and companies are governed by various structures, such as a single individual, or a group of persons that may be described as a governing ‘board’. Boards charged with governance of Commonwealth entities and companies are typically concerned with ensuring corporate compliance and management accountability and are required to publicly report on their structure and membership.

1.2 The three types of Commonwealth entities and companies discussed in this report are:

- Non-corporate Commonwealth entities (NCEs), which are legally and financially part of the Commonwealth and include departments of state, Parliamentary departments, and listed entities1;

- Corporate Commonwealth entities (CCEs), which have a separate legal identity from the Commonwealth, and are body corporates of the Commonwealth other than a Commonwealth company2; and

- Commonwealth companies, which are companies established under the Corporations Act 2001 (Corporations Act) that the Commonwealth controls and are legally separate from the Commonwealth.3

1.3 Under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), Commonwealth entities (NCEs and CCEs) are governed by accountable authorities, which may be an individual or a group of persons.4 Commonwealth companies are governed by directors which collectively comprise a board.5

1.4 Governing board members are subject to various legislative requirements.6 Members of the governing boards of Commonwealth entities are subject to requirements contained within the enabling legislation used to establish an entity. Board members of Commonwealth companies are subject to requirements in the Corporations Act, company constitutions, or a combination of both.7 Additionally, the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule) establishes requirements to report specific information about accountable authorities (such as the name of the individual(s)), and similar requirements regarding directors of Commonwealth companies (refer Table 3.1).

1.5 The PGPA Rule reporting requirements for governing boards are fulfilled by reporting information through annual reports and publishing annual reports using the digital reporting tool administered by the Minister for Finance, known as the Transparency Portal. The Department of Finance (Finance) is responsible for establishing and promulgating the Australian Government’s resource management framework.8 The Transparency Portal was established by Finance to provide a repository of publicly available corporate information for all Commonwealth entities and companies. From the 2018–19 reporting period, all annual reports were required to be published on and accessible from the Transparency Portal shortly after the presentation of these reports to the Parliament.9

1.6 Finance provides guidance on the implementation of the PGPA Rule reporting requirements through resource management guides (RMGs), such as:

- RMG 135 Annual reports for non-corporate Commonwealth entities;

- RMG 136 Annual report for corporate Commonwealth entities; and

- RMG 137 Annual reports for Commonwealth companies.

1.7 These RMGs set out the requirements for the publication of annual report information on the Transparency Portal. Finance also provides information on the types of Australian Government bodies, and a glossary of PGPA-related terms.10

1.8 The ANAO has undertaken a number of performance audits related to board governance. In April and May 2019, the Auditor-General presented a series of audits that reviewed whether the boards of selected CCEs had established effective arrangements to comply with selected legislative and policy requirements, and adopted practices that support effective governance.11 The ANAO also published an audit insights product from the audit series in 2019, which outlined a number of key messages that may be relevant to the operations of other governance boards as well as broader governance arrangements in Commonwealth entities.12

Rationale and approach

1.9 The purpose of the ANAO is to support accountability and transparency in the Australian Government sector through independent reporting to the Parliament, and thereby contribute to improved public sector performance.13 Section 25 of the Auditor-General Act 1997 enables the Auditor-General at any time to cause a report to be tabled in either House of the Parliament on any matter.

1.10 The objective of this information report is to provide transparency and insights on the governing boards of Commonwealth entities and companies and the membership of these boards. To achieve this, the report provides analysis of:

- governing board membership requirements outlined in relevant enabling legislation and company constitutions;

- reported information in annual reports on governing board members; and

- observations on data in relation to the reporting of governing boards.

1.11 This information report focuses on the governing boards of Commonwealth entities and companies.14 Entities may have other ‘boards’, such as advisory boards, to support the governing board. These advisory bodies are excluded from analysis. From a list of 187 Commonwealth entities and companies under the PGPA Act, 80 had a governing board.15 These consist of:

1.12 This information report is not an audit or assurance review report and does not present a conclusion. The analysis of the governing boards of Commonwealth entities and companies is based on data collated by the ANAO from various sources (refer Table 1.1). The bulk of this data was collected between January and March 2022.

Data sources

1.13 In compiling this report, the ANAO drew upon seven data sources relevant to the analysis of the governing boards of Commonwealth entities and companies, which are described in Table 1.1. All data used in this report is publicly available at no cost. In searching for documents that were publicly available, such as annual reports and company constitutions, the ANAO undertook online research as might be undertaken by a member of the general public, such as reviewing websites and conducting basic internet searches. The ANAO did not make use of its information-gathering powers, commercially-available services that require a fee or licence agreement to access information, or other non-public, fee charging sources.

Table 1.1: Data sources used in this information report

|

Data Source |

Purpose |

|

Flipchart of PGPA Act Commonwealth entities and companies as at 2 March 2022a and List of Commonwealth entities and companies under the PGPA Acta as at 2 March 2022 |

These documents are compiled by Finance and reflect the status of Commonwealth entities and companies at a point in time. This includes classification as NCEs, CCEs or Commonwealth companies under the PGPA Act and provides information on enabling legislation. The ANAO used these resources to identify Commonwealth entities and companies for inclusion in this information report. The Flipchart and List used for this report were published by Finance on 2 March 2022 and were the latest versions online when this report was drafted. |

|

The published, publicly available annual reports of Commonwealth entities and companies with governing boards |

The ANAO used annual reports from 2018–19, 2019–20 and 2020–21 to collate information related to governing board members of Commonwealth entities and companies. |

|

Enabling legislation of Commonwealth entities with governing boards |

The ANAO performed a high-level analysis of information from enabling legislation to identify and interpret membership requirements for the governing boards of Commonwealth entities. |

|

Constitutions of Commonwealth companies with governing boards |

The ANAO performed a high-level analysis of information from company constitutions that were found publicly online at no cost to identify membership requirements. |

|

Transparency Portal data |

This report includes the ANAO’s observations on publicly available data for 2018–19, 2019–20 and 2020–21 related to governing board members of Commonwealth entities and companies contained on the Transparency Portal as at January 2022. |

|

Australian Standard Classification of Educationb |

Due to variability across boards, this standard was used to identify qualifications, skills or experience requirements for governing board members specified in enabling legislation or company constitutions. |

|

Australian Qualifications Frameworkc |

This framework was used to identify qualifications of governing board members reported in annual reports. |

Note a: Department of Finance, PGPA Act Flipchart and List [Internet], Department of Finance, 2021, available from https://www.finance.gov.au/government/managing-commonwealth-resources/structure-australian-government-public-sector/pgpa-act-flipchart-and-list [accessed 28 March 2022].

Note b: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australian Standard Classification of Education (ASCED), [Internet], ABS, 2001, available from https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/1272.0 [accessed 17 December 2021].

Note c: Australian Qualifications Framework, Australian Qualifications Framework Second Edition January 2013, Australian Qualifications Framework Council, South Australia, 2013, available from https://www.aqf.edu.au/publication/aqf-second-edition [accessed 4 April 2022].

1.14 This report was prepared at a cost to the ANAO of $111,881.

2. Membership requirements of Commonwealth entities and companies

2.1 Commonwealth entities and companies with governing boards vary significantly by function, and governing boards may also vary in their composition, operating arrangements, independence and subject-matter focus, depending on the specific requirements of their enabling legislation, company constitution and other applicable laws. This chapter discusses common membership requirements prescribed in enabling legislation and company constitutions.

Scope of analysis and data availability

Data availability by entity type

2.2 Membership requirements of the governing boards of Commonwealth companies are not publicly available at no cost in all instances. The ANAO was able to use publicly available sources to identify membership requirements relating to all governing boards of non-corporate Commonwealth entities (NCEs) and corporate Commonwealth entities (CCEs), and 10 Commonwealth companies (56 per cent).18 The requirements for the remaining eight companies (44 per cent) are not included in this chapter.19 Table 2.1 shows the number and proportion of data available for membership requirements by entity type.20

Table 2.1: Availability of data for membership requirements of governing boards by entity type

|

|

Total number of entities with governing boards |

Number (proportion) of governing boards with publicly available data |

|

NCEs |

3 |

3 (100%) |

|

CCEs |

59 |

59 (100%) |

|

Commonwealth companies |

18 |

10 (56%) |

|

Total |

80 |

72 (90%) |

Source: ANAO analysis of enabling legislation and company constitutions that are publicly available at no cost.

Data availability by portfolio

2.3 The ANAO examined the extent to which common requirements for governing board members varied by the portfolio of the relevant entity.21 Data on governing board membership requirements varied by portfolio, due to both the number of boards in each portfolio, and the availability of data for these boards. The Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications portfolio had the largest number of entities governed by boards (25), of which data was available for the boards of 22 entities (refer Table 2.2). All other portfolios had 10 or fewer entities governed by boards.

Table 2.2: Availability of data for membership requirements of governing boards by portfolio

|

Portfolios |

Total number of entities having governing boards |

Number (proportion) of governing boards with publicly available data |

|

Agriculture, Water and the Environment |

7 |

7 (100%) |

|

Attorney-General’s |

1 |

1 (100%) |

|

Defence |

10 |

10 (100%) |

|

Education, Skills and Employment |

4 |

4 (100%) |

|

Finance |

3 |

1 (33%) |

|

Foreign Affairs and Trade |

2 |

2 (100%) |

|

Health |

7 |

6 (86%) |

|

Industry, Science, Energy and Resources |

6 |

5 (83%) |

|

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications |

25 |

22 (88%) |

|

Prime Minister and Cabinet |

9 |

9 (100%) |

|

Social Services |

2 |

2 (100%) |

|

Treasury |

3 |

2 (67%) |

|

Veterans’ Affairs (part of the Defence portfolio) |

1 |

1 (100%) |

|

Total |

80 |

72 (90%) |

Source: ANAO analysis of enabling legislation and company constitutions that are publicly available at no cost.

2.4 Additionally, the board requirements examined by the ANAO are those applying to the majority of governing board members. Due to variability in board conditions, the ANAO did not analyse requirements that may only apply to a small number of individuals, or a specific position title (such as a Chief Executive Officer or Managing Director). This means that some requirements that typically apply only to a specific position title (such as the Chair of the board) may not be represented in the below analysis. Refer to Appendix 1 for examples of the approach undertaken by the ANAO to interpret information in enabling legislation.

Common requirements for board membership and composition

2.5 Based on a high-level analysis of the enabling legislation of 62 Commonwealth entities and 10 company constitutions, the ANAO identified a selection of common requirements that applied to multiple governing boards. These generally related to size, period of appointment and qualifications, skills, or experience (refer Table 2.3).

Table 2.3: Total number and proportion of entities which specified governing board requirements by entity type

|

|

Minimum number of members |

Maximum number of members |

Maximum years per appointment |

Maximum combined years of servicea |

Qualifications, skills or experience |

|

NCEs (proportion of total)b |

3 (100%) |

3 (100%) |

3 (100%) |

0 (0%) |

1 (33%) |

|

CCEs (proportion of total)b |

59 (100%) |

55 (93%) |

54 (92%) |

16 (27%) |

33 (56%) |

|

Commonwealth companies (proportion of total)b |

10 (100%) |

9 (90%) |

8 (80%) |

0 (0%) |

2 (20%) |

Note a: Includes multiple appointments when members are eligible for reappointment.

Note b: The proportion of total calculations are based on a total of three NCEs, 59 CCEs and 10 companies.

Source: ANAO analysis of enabling legislation and company constitutions that are publicly available at no cost.

Number of members

2.6 The ANAO analysed the membership requirements of governing boards to report the prescribed minimum and/or maximum number of members. All 72 governing boards specified a minimum membership size, and 67 specified a maximum membership size.22 Table 2.4 shows the range in minimum and maximum number of board members (where specified) across the three entity types examined. The governing board of the Torres Strait Regional Authority had both the highest minimum and maximum number of board members.23

Table 2.4: Minimum and maximum number of governing board members by entity type

|

|

Minimuma |

Maximumb |

||||

|

|

Lowest |

Median |

Highest |

Lowest |

Median |

Highest |

|

NCEs |

2 |

5 |

8 |

5 |

5 |

8 |

|

CCEs |

1c |

7 |

20 |

4 |

9 |

23 |

|

Commonwealth companies |

1d |

3 |

5 |

7 |

9 |

12 |

Note a: These figures present data for governing boards of three NCEs, 59 CCEs, and 10 Commonwealth companies.

Note b: These figures present data for governing boards of three NCEs, 55 CCEs, and nine Commonwealth companies.

Note c: The ANAO has interpreted the Services Trust Funds Act 1947 to specify a minimum of one member for the governing boards of the Australian Military Forces Relief Trust Fund, Royal Australian Air Force Welfare Trust Fund and Royal Australian Navy Relief Trust Fund.

Note d: The ANAO has interpreted the company constitution for Bundanon Trust to specify a minimum of one governing board member as it makes explicit reference to the Chairperson only (refer Appendix 1). Other legislation, such as the Corporations Act, may impose minimum board membership requirements, however this was outside the scope of this report.

Source: ANAO analysis of enabling legislation and company constitutions that are publicly available at no cost.

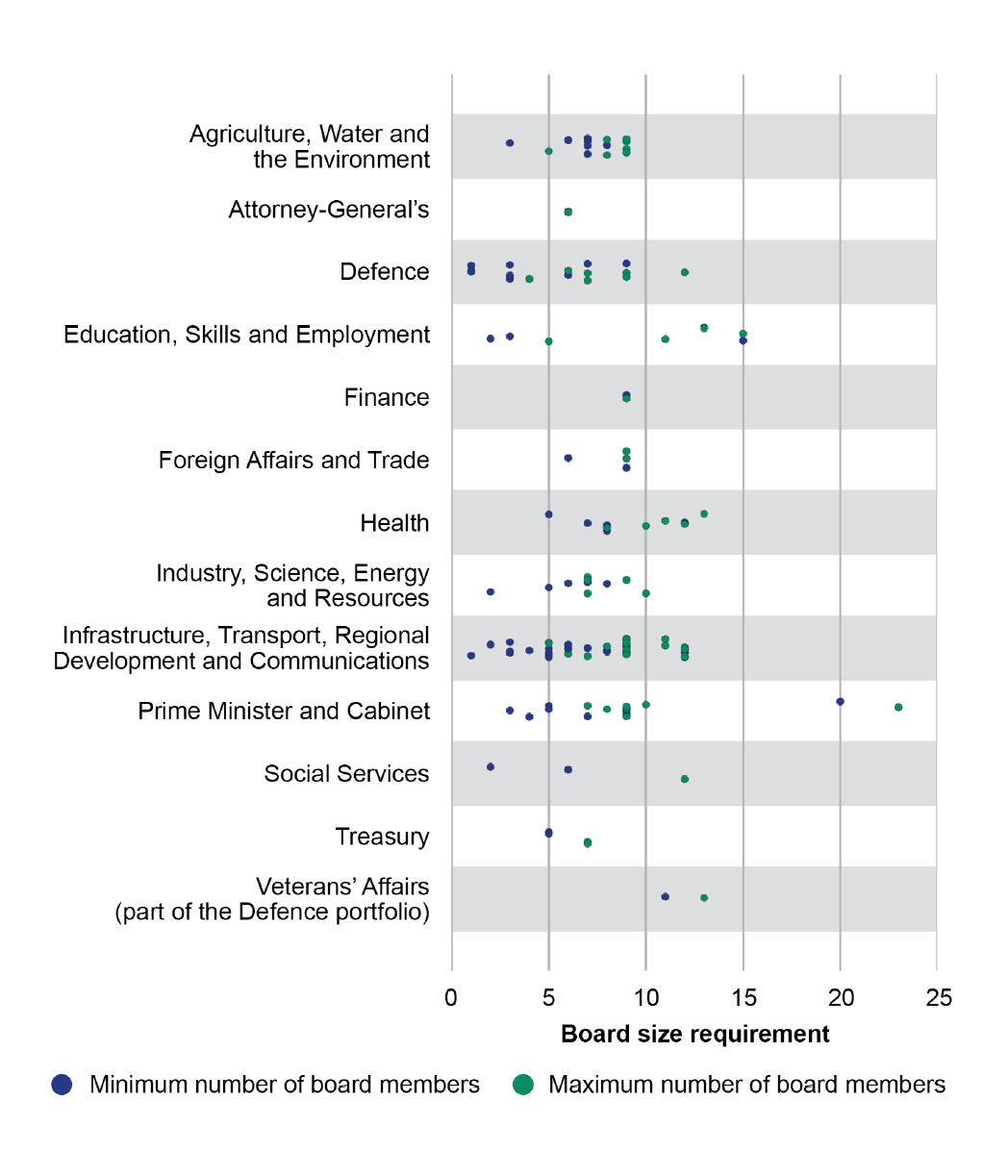

2.7 Figure 2.1 shows the number of governing boards for which minimum and maximum membership requirements were specified, and the variability of these requirements, across portfolios. The overlap between minimum and maximum membership requirements within portfolios shows the range of these requirements, while portfolios with more data points indicate a greater number of boards, or a greater number of boards with such requirements.

Figure 2.1: Minimum and maximum number of governing board members by portfolio

Source: ANAO analysis of enabling legislation and company constitutions that are publicly available at no cost.

Period of appointment

2.8 The ANAO analysed requirements relating to the maximum period (years) for each appointment as a governing board member. Among the 72 governing boards analysed, 65 had specified a maximum number of years for each appointment. This was generally consistent across the governing boards of all three entity types, with five years being the longest period of appointment (refer Table 2.5). Members can be eligible for reappointment depending on enabling legislation and applicable laws. The enabling legislation of 16 CCEs (27 per cent) specified a maximum combined number of years that a member can serve on a particular governing board (refer Table 2.3). This ranged from six to 10 years. None of the enabling legislation of NCEs or publicly available company constitutions specified this requirement.

Table 2.5: Maximum years per appointment and maximum combined years of governing board service by entity type

|

|

Maximum years per appointmenta |

Maximum combined years of serviceb |

||||

|

|

Lowest |

Median |

Highest |

Lowest |

Median |

Highest |

|

NCEs |

4 |

5 |

5 |

N/S |

N/S |

N/S |

|

CCEs |

1c |

3 |

5 |

6 |

9 |

10 |

|

Commonwealth companies |

3 |

3 |

5 |

N/S |

N/S |

N/S |

Note a: These figures present data for the governing boards of three NCEs, 54 CCEs, and eight Commonwealth companies. There were requirements relating to maximum number of years per appointment which exceeded five years, however these did not apply to the majority of the governing board members.

Note b: These figures present data for the governing boards of 16 CCEs and ‘N/S’ denotes that this requirement was not specified.

Note c: The ANAO has interpreted the Aboriginal Land Grant (Jervis Bay Territory) Act 1986 to specify a maximum period of appointment of one year for the governing board of the Wreck Bay Aboriginal Community Council, as members are elected on an annual basis but can be re-elected.

Source: ANAO analysis of enabling legislation and company constitutions that are publicly available at no cost.

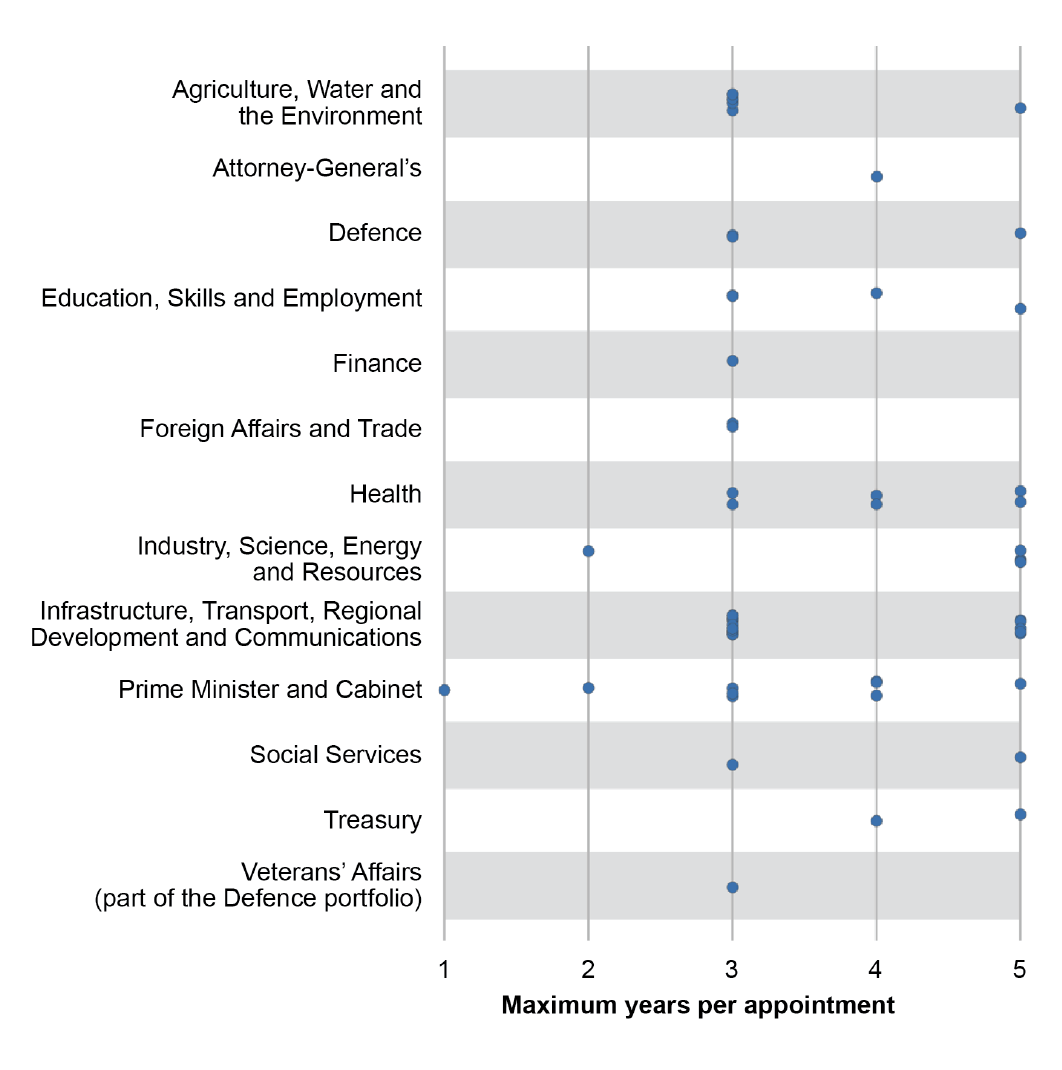

2.9 The maximum number of years per appointment requirement was generally consistent across portfolios, with three years being the most common period of appointment (see Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2: Maximum years per appointment of governing board members by portfolio

Note: There were requirements relating to maximum number of years per appointment which exceeded five years, however these did not apply to the majority of the governing board members. The ANAO has interpreted the Aboriginal Land Grant (Jervis Bay Territory) Act 1986 to specify a maximum period of appointment of one year for the governing board of the Wreck Bay Aboriginal Community Council, as members are elected on an annual basis but can be re-elected.

Source: ANAO analysis of enabling legislation and company constitutions that are publicly available at no cost.

2.10 Seven out of the 13 portfolios specified requirements relating to maximum combined years of service.24 Only the Infrastructure, Transport, Regional, Development and Communications portfolio had more than one CCE specifying this requirement with all 10 entities either specifying nine or 10 years. This was on the higher end of the range based on the data available.

Qualifications, skills or experience

2.11 The ANAO analysed the qualifications, skills, or experience requirements for governing board members specified in enabling legislation and company constitutions. In doing so the ANAO examined descriptive text to determine the relevant broad field of education for the requirement, as outlined in the Australian Standard Classification of Education (ASCED).25

2.12 For the 72 governing boards, 36 specified qualifications, skills or experience requirements for their governing board members and a further six stated governing board members should have knowledge or experience relevant to the entity. Table 2.6 shows that qualifications, skills or experiences relating to ‘management and commerce’, and ‘society and culture’ were most common at 83 per cent and 72 per cent of the 36 governing boards with specific requirements, respectively.

2.13 An understanding of information technology, cyber security and associated risks is increasingly relevant to organisations and their boards.26 Eight per cent of boards identified requirements relating to information technology, and none explicitly stated requirements for cyber security.27

Table 2.6: Top 10 qualifications, skills and experience requirements of governing board members

|

Broad field of education classification |

Number of governing boards with specified requirements |

Proportion of governing boards with specified requirements |

|

Management and Commerce |

30 |

83% |

|

Society and Culture |

26 |

72% |

|

Engineering and Related Technologies |

13 |

36% |

|

Agriculture, Environmental and Related Studies |

11 |

31% |

|

Natural and Physical Sciences |

8 |

22% |

|

Health |

6 |

17% |

|

Creative Arts |

5 |

14% |

|

Architecture and Building |

4 |

11% |

|

Education |

4 |

11% |

|

Information Technology |

3 |

8% |

Note: Each governing board can have multiple qualification, skills and experience requirements. This analysis presents data for the governing boards of one NCE, 33 CCEs, and two Commonwealth companies based on the ASCED’s broad field of education classification.

Source: ANAO analysis of enabling legislation and company constitutions that are publicly available at no cost.

3. Reporting on governing board membership of Commonwealth entities and companies

3.1 Commonwealth entities and companies are required to publicly report information relating to individual members of their governing boards. This chapter describes the type of member information boards are required to report and provides insights into the characteristics of governing board members based on this reporting.

Reporting requirements

3.2 The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule) sets out reporting requirements for annual reports of Commonwealth entities and companies in relation to their governing board members (refer Table 3.1). This chapter uses published annual reports that are publicly available at no cost to report on information relating to the governing board membership of Commonwealth entities and companies.

Table 3.1: PGPA Rule annual report reporting requirements relating to membership of governing boards

|

Entity type |

PGPA Rule reference |

Membership reporting requirement |

|

Non-corporate Commonwealth entity (NCEs)

|

Paragraph 17AE(1)(aa)

|

Name of the accountable authority or member |

|

Position title of the accountable authority or member |

||

|

Period as the accountable authority or member within the reporting period |

||

|

Corporate Commonwealth entity (CCEs)

|

Subsection 17BE(j)

|

Name of the accountable authority or member |

|

Qualifications of the accountable authority or member |

||

|

Experience of the accountable authority or member |

||

|

Number of meetings of the accountable authority attended by the member |

||

|

Whether the member is an executive or non-executive |

||

|

Commonwealth company |

Subsection 28E(f) |

Name of the director |

|

Qualifications of the director |

||

|

Experience of the director |

||

|

Number of meetings of the board of the company attended by the director |

||

|

Whether the director is an executive or non-executive |

||

|

All |

Sections 17CA and 28EA |

Information on remuneration of key management personnela |

Note a: RMG 138 Commonwealth entities’ executive remuneration reporting guide for annual reports and RMG 139 Commonwealth companies’ executive remuneration reporting guide for annual reports provides guidance for reporting remuneration details for key management personnel (KMP). As defined in AASB 124 Related Party Disclosures, KMP are those persons having authority and responsibility for planning, directing and controlling the activities of the entity, directly or indirectly, including any director (whether executive or otherwise) of that entity.

Source: PGPA Rule.

3.3 This report does not conclude on the compliance of Commonwealth entities and companies with reporting requirements.

3.4 This chapter provides analysis of the characteristics of governing board members using information reported in annual reports between 2018–19 and 2020–21.28 There were 932 separate individual members occupying 2340 governing board positions with a total reported pay of $169,695,127 across the three reporting periods.29 When analysing the characteristics of specific individual members, such as gender, qualifications, skills or experience, the ANAO has reported results by board position per reporting period, as these characteristics may change over time. When analysing factors such as the service length of a member, which are cumulative or do not change, the ANAO has reported results by individual member.

Board size

3.5 Table 3.2 shows there was minimal variation in the median size of governing boards by entity type over the three reporting periods.

Table 3.2: Median governing board size by entity type

|

|

2018–19 |

2019–20 |

2020–21 |

|

NCEs |

5 |

4 |

5 |

|

CCEs |

9 |

9 |

8 |

|

Commonwealth companies |

8 |

8 |

8 |

Note: For each individual board, a board member is considered to be a member of the board at 30 June of each financial year if they have not been explicitly stated to have ceased or have not reported a cessation date prior to 1 July the following financial year.

Source: ANAO analysis of annual reports published between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

3.6 Table 3.3 shows that in 2020–21, most governing boards had between six and 10 members. No governing board had over 20 members at 30 June 2021 and the largest governing board was the Torres Straight Regional Authority consisting of 20 members.

Table 3.3: Distribution of governing board sizes as at 30 June 2021 by entity type

|

|

≤ 5 members |

6-10 members |

11-15 members |

≥ 16 members |

Total |

|

NCEs |

2 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

|

CCEsa |

3 |

44 |

11 |

1 |

59 |

|

Commonwealth companies |

2 |

15 |

1 |

0 |

18 |

|

Total |

7 |

60 |

12 |

1 |

80 |

Note: For each individual board, a board member is considered to be a member of the board at 30 June 2021 if they have not been explicitly stated to have ceased or have not reported a cessation date prior to 1 July 2021.

Note a: The Australian National University has been calculated at 31 December 2020 as its reporting period is from 1 January to 31 December.

Source: ANAO analysis of annual reports published in 2020–21.

3.7 Table 3.4 shows the 13 largest governing boards in 2020–21 (those having 11 or more board members), of which nine are of the maximum size outlined in their relevant enabling legislation or company constitution.

Table 3.4: Thirteen largest governing boards as at 30 June 2021

|

Name of entity |

Portfolio |

Governing board sizea |

Maximum governing board sizeb |

|

Torres Strait Regional Authority |

Prime Minister and Cabinet |

20 |

23 |

|

Australian National Universityc |

Education, Skills and Employment |

15 |

15 |

|

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority |

Education, Skills and Employment |

13 |

13 |

|

Australian War Memorial |

Veterans’ Affairs (part of the Defence portfolio) |

13 |

13 |

|

Australian National Maritime Museum |

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications |

12 |

12 |

|

Australian Strategic Policy Institute Ltd |

Defence |

12 |

12 |

|

Food Standards Australia New Zealand |

Health |

12 |

12 |

|

Infrastructure Australia |

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications |

12 |

12 |

|

Australia Council |

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications |

11 |

12 |

|

Australian Digital Health Agency |

Health |

11 |

11 |

|

National Gallery of Australia |

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications |

11 |

11 |

|

National Library of Australia |

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications |

11 |

12 |

|

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare |

Health |

11 |

N/A |

Note a: For each individual board, a board member is considered to be a member of the board at 30 June 2021 if they have not been explicitly stated to have ceased or have not reported a cessation date prior to 1 July 2021.

Note b: Figures are based on the ANAO’s interpretation of maximum governing board size based on analysis of enabling legislation and company constitutions (refer paragraph 2.6).

Note c: Figures have been calculated at 31 December 2020 as the Australian National University’s reporting period is from 1 January to 30 December.

Source: ANAO analysis of annual reports published in 2020–21.

3.8 Table 3.5 shows the seven smallest governing boards in 2020–21, of which two are of the minimum size outlined in their relevant enabling legislation. Only the Indigenous Land and Sea Corporation did not meet their minimum board size requirements at the end of the 2020–21 reporting period.30 A further 10 boards consisted of six members.

Table 3.5: Seven smallest governing boards as at 30 June 2021

|

Name of entity |

Portfolio |

Governing board sizea |

Minimum governing board sizeb |

|

Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency |

Education, Skills and Employment |

3 |

2 |

|

Regional Investment Corporation |

Agriculture, Water and the Environment |

3 |

3 |

|

Royal Australian Air Force Veterans Residences Trust Fund |

Defence |

4 |

3 |

|

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership Limited |

Education, Skills and Employment |

5 |

N/A |

|

National Capital Authority |

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications |

5 |

5 |

|

RAAF Welfare Recreational Company |

Defence |

5 |

N/A |

|

Indigenous Land and Sea Corporation |

Prime Minister and Cabinet |

5 |

7 |

Note a: For each individual board, a board member is considered to be a member of the board at 30 June 2021 if they have not been explicitly stated to have ceased or have not reported a cessation date prior to 1 July 2021.

Note b: Figures are based on the ANAO’s interpretation of minimum governing board size based on analysis of enabling legislation and company constitutions (refer paragraph 2.6).

Source: ANAO analysis of annual reports published in 2020–21.

Board gender diversity

3.9 The PGPA Rule, Corporations Act 2001 and resource management guides do not outline any legislative requirements or guidance for gender diversity in board composition. The Office for Women prepares reports on gender balance on Australian Government boards annually, which includes a broader scope of boards than this information report and uses a different approach for identifying gender.31 The Gender Balance on Australian Government Boards Report 2020–21 states:

The Australian Government is working towards a gender diversity target of women holding 50 per cent of Government board positions overall, and women and men each holding at least 40 per cent of positions at the individual board level. These targets took effect from 1 July 2016.32

3.10 The ANAO identified the gender of a governing board member by examining the pronouns used to describe the skills, experience and qualifications of a member in annual reports.33 Between 2018–19 and 2020–21, there were 562 occupied board positions (24 per cent) for which gender could not be identified. Based on the data available, the gender composition of boards has remained relatively stable over the three reporting periods.

Figure 3.1: Gender composition of governing boards

Note: The 562 occupied board positions for which gender could not be identified have been included in determining the proportion of female or male membership.

Source: ANAO analysis of annual reports published between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

3.11 Corporate Commonwealth entities and companies are required to report on whether their governing board members have executive or non-executive status (refer Table 3.1).34 The 2340 occupied governing board positions were filled by 932 individuals between 2018–19 and 2020–21. Of these 932 individuals, 91 did not have an explicitly reported executive status. Of the 1598 occupied board positions for which both gender and executive status could be identified, on average, females comprise 10 per cent of all executive board members listed in annual reports between 2018–19 and 2020–21, and comprise 38 per cent of all non-executive members.

Figure 3.2: Gender composition of governing board members by executive status

Note: This figure represents the total proportion between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

Source: ANAO analysis of annual reports published between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

3.12 Of the top 10 boards by proportion of female membership, seven had at least 67 per cent female membership (refer Table 3.6). Of the top 10 boards by proportion of male membership, nine had at least 67 per cent male membership, with four governing boards having 75 per cent or greater male membership (refer Table 3.7).

Table 3.6: Top 10 governing boards by proportion of female membership as at 30 June 2021

|

Name of entity |

Portfolio |

Proportion (number) of members identified as female |

Proportion (number) of members identified as male |

Proportion (number) of members whose gender could not be identified |

|

Regional Investment Corporation |

Agriculture, Water and the Environment |

100% (3) |

0% (0) |

0% (0) |

|

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care |

Health |

88% (7) |

12% (1) |

0% (0) |

|

Australian Institute of Marine Science |

Industry, Science, Energy and Resources |

71% (5) |

29% (2) |

0% (0) |

|

Clean Energy Finance Corporation |

Industry, Science, Energy and Resources |

71% (5) |

29% (2) |

0% (0) |

|

Wine Australia |

Agriculture, Water and the Environment |

71% (5) |

29% (2) |

0% (0) |

|

Australian Reinsurance Pool Corporation |

Treasury |

67% (4) |

33% (2) |

0% (0) |

|

Civil Aviation Safety Authority |

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications |

67% (4) |

33% (2) |

0% (0) |

|

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare |

Health |

64% (7) |

36% (4) |

0% (0) |

|

Financial Adviser Standards and Ethics Authority Ltd |

Treasury |

62% (5) |

25% (2) |

12% (1) |

|

National Film and Sound Archive of Australia |

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications |

57% (4) |

43% (3) |

0% (0) |

Note: Figures may not sum to 100% due to rounding.

Source: ANAO analysis of annual reports published in 2020–21.

Table 3.7: Top 10 governing boards by proportion of male membership as at 30 June 2021

|

Name of entity |

Portfolio |

Proportion (number) of members identified as female |

Proportion (number) of members identified as male |

Proportion (number) of members whose gender could not be identified |

|

Australian Naval Infrastructure Pty Ltd |

Finance |

17% (1) |

83% (5) |

0% (0) |

|

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership Limited |

Education, Skills and Employment |

20% (1) |

80% (4) |

0% (0) |

|

Sydney Harbour Federation Trust |

Agriculture, Water and the Environment |

25% (1) |

75% (3) |

0% (0) |

|

Torres Strait Regional Authority |

Prime Minister and Cabinet |

25% (5) |

75% (15) |

0% (0) |

|

Australian War Memorial |

Veterans’ Affairs (part of the Defence portfolio) |

31% (4) |

69% (9) |

0% (0) |

|

Food Standards Australia New Zealand |

Health |

25% (3) |

67% (8) |

8% (1) |

|

Australian National Maritime Museum |

Infrastructure, Transport. Regional Development and Communications |

33% (4) |

67% (8) |

0% (0) |

|

National Museum of Australia |

Infrastructure, Transport. Regional Development and Communications |

33% (3) |

67% (6) |

0% (0) |

|

Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency |

Education, Skills and Employment |

33% (1) |

67% (2) |

0% (0) |

|

Australian Maritime Safety Authority |

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications |

25% (2) |

62% (5) |

12% (1) |

Note: Figures may not sum to 100% due to rounding.

Source: ANAO analysis of annual reports published in 2020–21.

Board service length

3.13 Commencement and cessation dates were available for 910 occupied board positions to determine the member’s period of appointment. Of the 910 board positions, 64 per cent served on a board for four years or less.35 Figure 3.3 shows that the length served by governing board members can vary widely, with the longest period served approximately 29 years. The shortest length served was three days.36 The average length served by a governing board member reported between 2018–19 and 2020–21 was 3.7 years.

Figure 3.3: Distribution of governing board members’ service length (years)

Source: ANAO analysis of annual reports published between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

3.14 Of the top 10 governing boards by members’ average service length, five boards include members who have served for at least 10 years (refer Table 3.8).

Table 3.8: Top 10 governing boards by members’ average service length (years)

|

Name of entity |

Portfolio |

Average service length (years) |

|

ASC Pty Ltd |

Finance |

6.1 |

|

Special Broadcasting Service Corporation |

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications |

6.0 |

|

National Portrait Gallery of Australia |

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications |

6.0 |

|

Commonwealth Superannuation Corporation (CSC) |

Finance |

5.6 |

|

Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation |

Industry, Science, Energy and Resources |

5.3 |

|

Australian Rail Track Corporation Limited |

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications |

5.2 |

|

Wreck Bay Aboriginal Community Council |

Prime Minister and Cabinet |

5.1 |

|

Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation |

Industry, Science, Energy and Resources |

5.1 |

|

Royal Australian Air Force Welfare Trust Fund |

Defence |

5.1 |

|

Sydney Harbour Federation Trust |

Agriculture, Water and the Environment |

5.0 |

Source: ANAO analysis of annual reports published between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

3.15 Of the bottom 10 governing boards by members’ average service length, nine had at least one board member with a service length of less than one year (refer Table 3.9). The shortest service length reported for the Financial Adviser Standards and Ethics Authority Ltd was 1.6 years.

Table 3.9: Bottom 10 governing boards by members’ average service length (years)

|

Name of entity |

Portfolio |

Average service length (years) |

|

Indigenous Business Australia |

Prime Minister and Cabinet |

1.0a |

|

Australian Film, Television and Radio School |

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications |

1.8 |

|

Financial Adviser Standards and Ethics Authority Ltd |

Treasury |

2.0 |

|

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies |

Prime Minister and Cabinet |

2.2 |

|

AAF Company |

Defence |

2.2 |

|

Royal Australian Navy Central Canteens Board |

Defence |

2.3 |

|

National Library of Australia |

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications |

2.4 |

|

Australian Digital Health Agency |

Health |

2.4 |

|

Royal Australian Navy Relief Trust Fund |

Defence |

2.4 |

|

Civil Aviation Safety Authority |

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications |

2.4 |

Note a: There were two board members of Indigenous Business Australia for which a commencement and cessation date could be found. Both had a service length of less than 1.2 years.

Source: ANAO analysis of annual reports published between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

3.16 Due to variability in governing board member position titles to describe a member’s role or responsibility, the ANAO performed analysis by mapping the reported position titles using the list in Appendix 2. Chairs (or equivalent) on governing boards have an average service length that is 1.5 years longer than general members (refer Table 3.10).

Table 3.10: Governing board members’ average service length by board position title

|

Titlea |

Number of board positions |

Average service length (years) |

|

Chair or chair-equivalent |

97 |

4.9 |

|

Deputy chair or deputy chair-equivalent |

38 |

4.7 |

|

Member |

694 |

3.4 |

|

CEO |

52 |

4.2 |

|

Trustee |

28 |

3.6 |

|

Ex-Officio |

1 |

3.2 |

|

Total |

910 |

3.7 |

Note a: This analysis is based on the ANAO’s mapping of reported position titles and only includes occupied board positions for which commencement and cessation dates were available to determine the member’s period of appointment.

Source: ANAO analysis of annual reports published between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

3.17 Analysis of the executive status of governing board members shows no significant difference in average service length (refer Table 3.11).

Table 3.11: Governing board members’ average service length by executive status

|

Executive status |

Number of board positions |

Average service length (years) |

|

Executive |

91 |

4.1 |

|

Non-executive |

744 |

3.6 |

Note: This analysis only includes occupied board positions for which both executive status and commencement and cessation dates were available to determine the member’s period of appointment.

Source: ANAO analysis of annual reports published between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

Turnover

3.18 The ANAO calculated an annual turnover rate for each reporting period by dividing the number of board member cessations by the number of members sitting at the beginning of the period. For the purposes of this analysis, the average turnover rate is the average of these figures across the three reporting periods.

3.19 Table 3.12 shows that over half of the top 10 governing boards by average turnover rate are within the Defence and Prime Minister and Cabinet portfolios. The Australian Film, Television and Radio School had the highest average turnover rate (44 per cent).

Table 3.12: Top 10 governing boards by average turnover rate

|

Name of entity |

Portfolio |

Average turnover ratea |

|

Australian Film, Television and Radio School |

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications |

44% |

|

AAF Company |

Defence |

37% |

|

RAAF Welfare Recreational Company |

Defence |

37% |

|

Royal Australian Navy Central Canteens Board |

Defence |

36% |

|

Indigenous Land and Sea Corporation |

Prime Minister and Cabinet |

35% |

|

Aboriginal Hostels Limited |

Prime Minister and Cabinet |

34% |

|

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority |

Education, Skills and Employment |

32% |

|

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies |

Prime Minister and Cabinet |

32% |

|

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership Limited |

Education, Skills and Employment |

31% |

|

Australian Military Forces Relief Trust Fund |

Defence |

31% |

Note a: Turnover for a given entity in a given year is calculated as the number of cessations as a proportion of members who were occupying a position on 1 July for that reporting period. This is then averaged across the three reporting periods.

Source: ANAO analysis of annual reports published between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

3.20 Table 3.13 shows five governing boards with no turnover between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

Table 3.13: Governing boards with no turnover

|

Name of entity |

Portfolio |

|

Clean Energy Finance Corporation |

Industry, Science, Energy and Resources |

|

National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation (NHFIC) |

Treasury |

|

National Portrait Gallery of Australia |

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communication |

|

Royal Australian Air Force Veterans Residences Trust Fund |

Defence |

|

WSA Co Ltd |

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communication |

Source: ANAO analysis of cessations reported in annual reports published between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

3.21 The average turnover rate of governing board members for NCEs (11 per cent) is lower than CCEs (19 per cent) and Commonwealth companies (18 per cent) (refer Table 3.14).

Table 3.14: Governing board members’ average turnover rate by entity type

|

Type of entity |

Average turnover ratea |

|

NCEs |

11% |

|

CCEs |

19% |

|

Commonwealth companies |

18% |

Note a: Turnover for a given entity type in a given year is calculated as the number of cessations as a proportion of members who were occupying a position on 1 July for that reporting period. This is then averaged across the three reporting periods.

Source: ANAO analysis of annual reports published between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

Board member qualifications

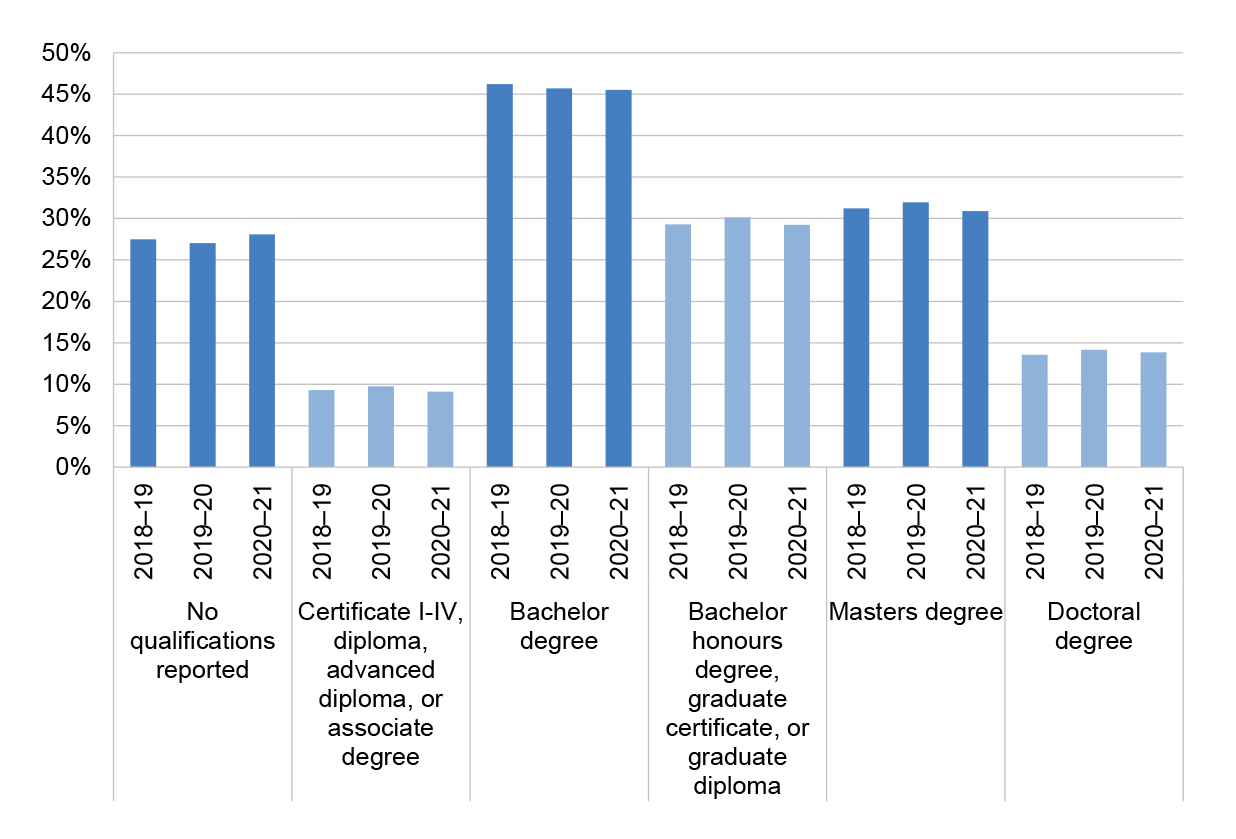

3.22 The ANAO identified qualifications of governing board members based on a quantitative analysis of qualifications that were explicitly reported in annual reports. Analysis of these qualifications were based on the levels of qualifications outlined in the Australian Qualifications Framework.37 While some boards may require members with specific qualifications, some may look for specific knowledge or experience (such as experience in Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander community life). The ANAO analysis did not include whether board members had equivalent skills or experiences in line with these qualifications.

3.23 Of the 2340 occupied governing board positions between 2018–19 and 2020–21, information regarding the experience and qualifications of the individual holding the board position was not available for 36 positions (1.5 per cent). These positions were excluded from further analysis. Where information regarding the experience or qualifications of an individual occupying a board position was provided, but specific qualifications were not identifiable, the position was considered to have no reported qualification for analysis purposes.

3.24 Figure 3.4 shows the proportion of reported qualifications by financial year, noting one board position can appear in more than one educational level if multiple qualifications were identified.38 The proportion of reported qualifications in each category were largely consistent over time. Overall, 28 per cent of occupied governing board positions analysed did not report any identifiable qualifications and 70 per cent were reported to have a bachelor’s degree or above.

Figure 3.4: Reported qualifications by financial year

Note: This presents all qualifications that could be identified by the ANAO in annual reports between 2018–19 and 2020–21. Where a governing board member has more than one qualification in the same category, these are counted only once.

Source: ANAO analysis of annual reports published between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

3.25 Figure 3.5 shows the highest reported qualification of occupied board positions by financial year. More than half of the governing board positions occupied by members with identifiable qualifications have held postgraduate qualifications in each of the financial years between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

Figure 3.5: Highest reported qualification of occupied governing board positions

Note: Based on the levels outlined in the Australian Qualifications Framework, the ANAO has defined a graduate qualification as a bachelor’s degree, and a postgraduate qualification as a bachelor’s degree with honours; graduate certificate; graduate diploma; master’s degree and doctoral degree.

Source: ANAO analysis of annual reports published between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

3.26 Figure 3.6 shows the highest reported qualification of occupied board positions by portfolio. The Prime Minister and Cabinet portfolio had the highest proportion of board positions with no reported qualifications (56 per cent) while the Treasury portfolio had the lowest (7 per cent). The Industry, Science, Energy and Resources portfolio had the highest proportion of board positions with a postgraduate qualification (73 per cent) and the Prime Minister and Cabinet portfolio had the lowest (24 per cent).

Figure 3.6: Highest reported qualification of occupied governing board positions by portfolio

Note: Based on the levels outlined in the Australian Qualifications Framework, the ANAO has defined a graduate qualification as a bachelor’s degree, and a postgraduate qualification as a bachelor with honours; graduate certificate; graduate diploma; master’s degree and doctoral degree.

Source: ANAO analysis of annual reports published between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

Non-executive board member remuneration

3.27 The total remuneration of a governing board member is comprised of their base salary, short-term incentives including bonuses, superannuation, long-service leave and other long-term incentives. The Remuneration Tribunal determines the remuneration of board members, where the board member occupies a position that meets the definition of a public office under the Remuneration Tribunal Act 1973, or where the position has been referred to the Remuneration Tribunal.39

3.28 The ANAO analysed the remuneration of non-executive board members. Executive members have been excluded as they receive remuneration for responsibilities outside their board duties. The ANAO did not analyse the remuneration of every board member, as two entities reported board member remuneration in aggregate.40 An additional 10 entities do not have paid governing board members.41

3.29 Table 3.15 shows that the remuneration of paid non-executive governing board members in 2020–21 was generally less than $60,000 (324 individuals or 59 per cent). There were 60 individuals who received $100,000 or more in 2020–21.

Table 3.15: Distribution of non-executive governing board members’ remuneration in 2020–21

|

Remuneration ($) |

Number of board positions |

Proportion of total |

|

Unpaid |

41 |

7% |

|

Greater than 0 and less than 20,000 |

120 |

22% |

|

Greater than or equal to 20,000 and less than 40,000 |

120 |

22% |

|

Greater than or equal to 40,000 and less than 60,000 |

84 |

15% |

|

Greater than or equal to 60,000 and less than 80,000 |

81 |

14% |

|

Greater than or equal to 80,000 and less than 100,000 |

51 |

9% |

|

Greater than or equal to 100,000 |

60 |

11% |

|

Total |

557 |

100% |

Source: ANAO analysis of annual reports published in 2020–21.

3.30 Table 3.16 shows that the average remuneration of non-executive governing board members of Commonwealth companies is greater than Commonwealth entities in 2020–21.

Table 3.16: Remuneration of non-executive governing board members by entity type in 2020–21

|

|

Number of board positions |

Average remuneration ($) |

Median remuneration ($) |

Total remuneration ($) |

|

NCEs |

14 |

63,102 |

28,215 |

883,434 |

|

CCEs |

441 |

43,612 |

36,295 |

19,233,100 |

|

Commonwealth companies |

102 |

66,186 |

53,949 |

6,751,013 |

|

Total |

557 |

48,236 |

37,678 |

26,867,547 |

Note: This analysis accounts for all non-executive members, including those who joined or retired from boards in the given timeframe.

Source: ANAO analysis of annual reports published between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

3.31 Table 3.17 shows the top 10 portfolios by total non-executive board members’ remuneration in 2020–21. The Finance portfolio has the highest average individual remuneration ($96,208) and the Prime Minister and Cabinet portfolio has the lowest ($30,218).

Table 3.17: Top 10 portfolios by total non-executive governing board members’ remuneration in 2020–21

|

Portfolio |

Number of board positions |

Total reported remuneration ($) |

Maximum individual remuneration ($) |

Average individual remuneration ($) |

|

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications |

194 |

10,710,937 |

248,488 |

55,211 |

|

Industry, Science, Energy and Resources |

48 |

3,434,086 |

248,683 |

71,543 |

|

Prime Minister and Cabinet |

83 |

2,508,079 |

284,084 |

30,218 |

|

Agriculture, Water and the Environment |

61 |

2,127,045 |

94,143 |

34,870 |

|

Finance |

20 |

1,924,160 |

182,088 |

96,208 |

|

Health |

34 |

1,244,595 |

130,085 |

36,606 |

|

Social Services |

18 |

1,168,808 |

162,610 |

64,934 |

|

Education, Skills and Employment |

28 |

1,053,782 |

177,870 |

37,635 |

|

Foreign Affairs and Trade |

20 |

1,041,724 |

130,502 |

52,086 |

|

Treasury |

22 |

933,006 |

121,392 |

42,409 |

Note: This analysis accounts for all non-executive members, including those who joined or retired from boards in the given timeframe.

Source: ANAO analysis of annual reports published between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

3.32 Table 3.18 shows the top 10 entities by total non-executive board members’ remuneration in 2020–21. Six of the top 10 entities are within the Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications portfolio. Snowy Hydro Limited has both the highest total reported remuneration and average individual remuneration for non-executive members in 2020–21.

Table 3.18: Top 10 entities by total non-executive governing board members’ remuneration in 2020–21

|

Name of entity |

Number of board positions |

Total reported remuneration ($) |

Maximum individual remuneration ($) |

Average individual remuneration ($) |

|

Snowy Hydro Limited |

8 |

1,152,477 |

248,683 |

144,060 |

|

Australian Postal Corporation |

8 |

1,063,232 |

211,137 |

132,904 |

|

NBN Co Limited |

8 |

1,023,505 |

248,488 |

127,938 |

|

National Disability Insurance Scheme Launch Transition Agencya |

10 |

881,205 |

162,610 |

88,121 |

|

Infrastructure Australia |

12 |

848,263 |

130,502 |

70,689 |

|

Commonwealth Superannuation Corporation |

9 |

832,659 |

154,198 |

92,518 |

|

Airservices Australia |

10 |

809,662 |

192,858 |

80,966 |

|

WSA Co Ltd |

7 |

795,077 |

182,088 |

113,582 |

|

Australian Rail Track Corporation Limited |

7 |

772,144 |

182,788 |

110,306 |

|

Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation |

9 |

728,569 |

159,439 |

80,952 |

Note a: The National Disability Insurance Scheme Launch Transition Agency has been renamed the National Disability Insurance Agency from 8 April 2022.

Source: ANAO analysis of annual reports published between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

3.33 Table 3.19 shows the top 10 board members by remuneration who were paid a total of $2,105,434. All 10 individuals held the Chair position title on each governing board. Of these 10, six individuals occupied positions on boards within the Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications portfolio.

3.34 The two lowest paid individuals in 2020–21 both occupied positions on the Australian Renewable Energy Agency governing board. Both individuals received less than $1,500 and ceased their engagement with the entity less than one month into the reporting period.

Table 3.19: Top 10 governing board members’ remunerations in 2020-21

|

Board |

Role |

Portfolio |

Total remuneration ($) |

|

Torres Strait Regional Authority |

Chair |

Prime Minister and Cabinet |

284,084 |

|

Snowy Hydro Limited |

Chair |

Industry, Science, Energy and Resources |

248,683 |

|

NBN Co Limited |

Chair |

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications |

248,488 |

|

Australian Postal Corporation |

Chair |

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications |

211,137 |

|

Australian Broadcasting Corporation |

Chair |

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications |

195,350 |

|

Airservices Australia |

Chair |

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications |

192,858 |

|

Australian Rail Track Corporation Limited |

Chair |

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications |

182,788 |

|

ASC Pty Ltd |

Chair |

Finance |

182,088 |

|

WSA Co Ltd |

Chair |

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications |

182,088 |

|

Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency |

Chair |

Education, Skills and Employment |

177,870 |

Source: ANAO analysis of annual reports published in 2020–21.

3.35 Table 3.20 shows that Chair (or equivalent) board members are paid at, on average, over double the rate of their Deputy-Chair (or equivalent) and general member counterparts. There is minimal difference between the average remuneration of Deputy-Chairs and members.

Table 3.20: Remuneration of non-executive governing board members by position title in 2020–21

|

Titlea |

Number of board positions |

Total reported remuneration ($) |

Maximum individual remuneration ($) |

Average individual remuneration ($) |

Median individual remuneration ($) |

|

Chair (or equivalent) |

65 |

6,681,280 |

284,084 |

102,789 |

87,520 |

|

Deputy-chair (or equivalent) |

30 |

1,385,513 |

129,707 |

46,184 |

40,788 |

|

Member |

462 |

18,800,718 |

148,914 |

40,694 |

30,370 |

Note a: This analysis is based on ANAO’s mapping of reported position titles and accounts for all non-executive members, including those who joined or retired from boards in the given timeframe.

Source: ANAO analysis of annual reports published in 2020–21.

Board meeting attendance

3.36 Annual reports are required by the PGPA Rule to include the number of meetings attended by members of the accountable authority or director during each reporting period. There is no requirement to provide the total number of possible meetings each member could have attended in each reporting period.

3.37 The ANAO analysed the meeting attendance of the governing boards of the 77 entities that reported both the meetings attended by board members and the total number of possible meetings to attend. Three entities did not provide information regarding their total number of possible meetings in each reporting period and as such were excluded from this analysis.42

3.38 Table 3.21 shows the aggregated average meeting attendance rates across all boards, with an average attendance rate of 92 per cent across all reporting periods. Non-corporate Commonwealth entities have the highest meeting attendance rate with the average member attending 98 per cent of possible board meetings between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

Table 3.21: Governing board members’ average meeting attendance rate by entity type between 2018–19 and 2020–21

|

|

Number of board positions |

Average meeting attendance ratea |

|

NCEs |

16 |

98% |

|

CCEs |

1693 |

92% |

|

Commonwealth companies |

475 |

91% |

Note a: This has been calculated as an aggregated average of meetings attended between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

Source: ANAO analysis of annual reports published between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

3.39 Table 3.22 shows that executive members or members of higher positions within a governing board have higher attendance rates than non-executive members. Trustees were observed to attend approximately 77 per cent of board meetings.

Table 3.22: Governing board members’ average meeting attendance rate by position title between 2018–19 and 2020–21

|

Titlea |

Number of board positions |

Average meeting attendance rateb |

|

CEO |

107 |

99% |

|

Chair |

245 |

98% |

|

Deputy-Chair |

113 |

93% |

|

Ex-Officio |

3 |

100% |

|

Member |

1658 |

91% |

|

Trustee |

58 |

77% |

Note a: This analysis is based on ANAO’s mapping of reported position titles.

Note b: This has been calculated as an aggregated average of meetings attended between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

Source: ANAO analysis of annual reports published between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

3.40 Table 3.23 and Table 3.24 show the top and bottom 10 governing boards by members’ average meeting attendance rate. Of the bottom 10 boards for average meeting attendance rate, five comprise of members with no reported remuneration.43

Table 3.23: Top 10 governing boards by members’ average meeting attendance rate between 2018–19 and 2020–21

|

Entity |

Number of board positions |

Average meeting attendance ratea |

|

Cotton Research and Development Corporation |

29 |

99% |

|

Army and Air Force Canteen Service (Frontline Defence Services) |

22 |

99% |

|

Hearing Australia |

23 |

99% |

|

Australian Broadcasting Corporation |

32 |

99% |

|

Snowy Hydro Limited |

30 |

99% |

|

WSA Co Ltd |

19 |

99% |

|

Australian Maritime Safety Authority |

20 |

98% |

|

Tourism Australia |

29 |

98% |

|

Civil Aviation Safety Authority |

24 |

98% |

|

Australian Institute of Marine Science |

23 |

98% |

Note a: This has been calculated as an aggregated average of meetings attended between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

Source: ANAO analysis of annual reports published between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

Table 3.24: Bottom 10 governing boards by members’ average meeting attendance rate between 2018–19 and 2020–21

|

Entity |

Number of board positions |

Average meeting attendance ratea |

|

Royal Australian Air Force Welfare Trust Fund |

25 |

71% |

|

Australian Digital Health Agency |

38 |

74% |

|

National Australia Day Council Limited |

30 |

78% |

|

RAAF Welfare Recreational Company |

22 |

81% |

|

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care |

31 |

81% |

|

Royal Australian Air Force Veterans Residences Trust Fund |

12 |

83% |

|

Australian Strategic Policy Institute Ltd |

41 |

84% |

|

Australian War Memorial |

28 |

85% |

|

Screen Australia |

26 |

85% |

|

Royal Australian Navy Relief Trust Fund |

25 |

85% |

Note a: This has been calculated as an aggregated average of meetings attended between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

Source: ANAO analysis of annual reports published between 2018–19 and 2020–21.

Members of multiple governing boards

3.41 Of the 932 individuals that served on the governing boards of Commonwealth entities and companies between 2018–19 and 2020–21, 63 individuals occupied positions on multiple governing boards within a single reporting period. Of these 63 individuals, 56 occupied positions on two boards and seven individuals occupied positions on three boards.44 No individual served on more than three governing boards of Commonwealth entities and companies during these three reporting periods.

4. Observations regarding data on governing board memberships

4.1 In compiling this report, the ANAO used data that is publicly available at no cost on the governing board membership of Commonwealth entities and companies from multiple sources (refer Table 1.1). The ANAO did not verify the completeness or accuracy of data from annual reports or the Transparency Portal, which is self-reported by Commonwealth entities and companies. This report does not conclude on the compliance of Commonwealth entities or companies with requirements regarding the reporting of this data. This chapter summarises observations made by the ANAO that may be relevant in understanding the extent of analysis that is possible using publicly available data on the governing boards of Commonwealth entities and companies.

Transparency Portal

4.2 As outlined in paragraph 1.5, the Transparency Portal is a digital reporting tool administered by the Minister for Finance. The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule) requires non-corporate Commonwealth entities (NCEs), corporate Commonwealth entities (CCEs) and Commonwealth companies to publish annual reports using the tool.45 From the 2018–19 reporting period, all annual reports were to be published on and accessible from the Transparency Portal shortly after the presentation of these reports to the Parliament.

4.3 The Department of Finance (Finance) has created a collection of templates for standard datasets that must be completed for each entity’s annual report. These templates were designed to populate the Transparency Portal ‘Find Data’ function, which displays both non-financial and financial information. As of January 2022, there were 23 non-financial datasets and 13 financial datasets available online for viewing mandatory PGPA Rule-related information.

4.4 Of the 23 non-financial datasets, the three related to reporting requirements for governing boards of Commonwealth entities and companies are known as:

- Details of accountable authority during the year;

- Details of director during the year; and

- Information about remuneration for key management personnel.

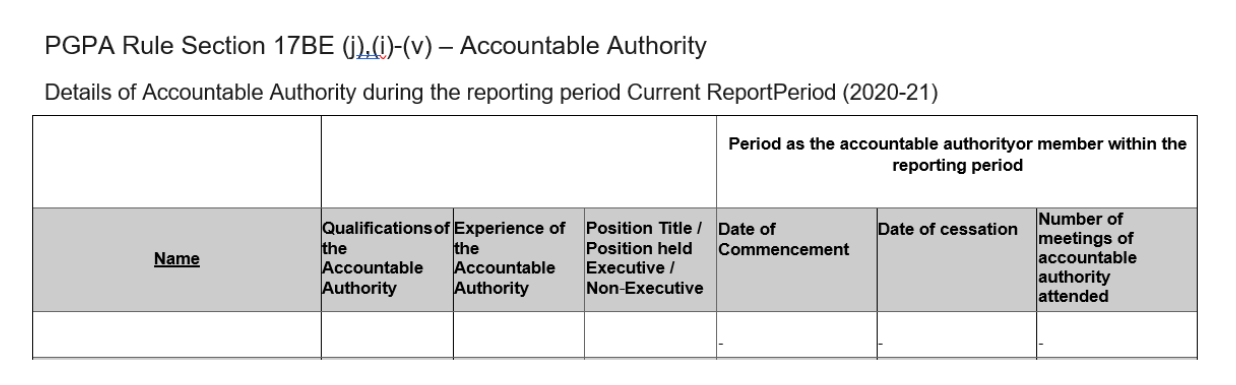

4.5 Figure 4.1 below provides an example of the data template used to provide information on the accountable authority.

Figure 4.1: Data template to report on details of accountable authority

Source: Department of Finance, RMG 136 Annual report for corporate Commonwealth entities, Appendix B: Digital Annual Reporting Tool data templates, p. 2.

4.6 In producing this report, the ANAO manually collected data from annual reports that were available publicly at no cost, and did not make use of Transparency Portal datasets. This approach was taken due to the following observations.

Availability and timeliness

4.7 Under the PGPA Rule, annual reports must be published on the Transparency Portal as soon as practicable after the annual report has been tabled in the Parliament.46 As outlined in the relevant resource management guides (RMGs) (refer paragraph 1.6), annual reports are expected to be tabled prior to the October Estimates Hearings. Commonwealth entities are required to provide the annual report to their responsible minister by the fifteenth day of the fourth month after the end of the reporting period for the entity, unless an extension has been granted.47 Commonwealth companies are required to provide the annual report to their responsible minister by the earlier of the following: 21 days before the next annual general meeting after the end of the period for the company; or four months after the end of the reporting period for the company.48 The relevant RMGs also state the completion of data templates in the Transparency Portal is mandatory.

4.8 The ANAO observed that all three non-financial datasets were available for the three reporting periods (2018–19, 2019–20 and 2020–21).49 Transparency Portal datasets indicate when an entity has not provided data, and the ANAO observed that each dataset for each reporting period listed Commonwealth entities and companies for which source data was not available. However, this list also included entities which no longer exist, and entities and/or companies that were not required to report information for the relevant dataset.50 The ANAO further observed occasions where an entity appeared to provide data but contained no information.51 Table 4.1 lists the number and proportion of Commonwealth entities and companies for which source data was not available for the relevant dataset. As at January 2022, 29 Commonwealth entities had yet to publish details of their accountable authority in the 2020–21 reporting period through the Transparency Portal.

Table 4.1: Number of entities with no relevant source data available through the Transparency Portal

|

Dataset |

2020–21a (proportion of total) |

2019–20b (proportion of total) |

2018–19c (proportion of total) |

|

Details of accountable authority during the year |

29 (18%) |

13 (8%) |

7 (4%) |

|

Details of director during the year |

2 (11%) |

1 (6%) |

3 (17%) |

|

Information about remuneration for key management personnel |

27 (15%) |

8 (4%) |

16 (9%) |

Note: These figures exclude the entities which appeared to provide data but contained no information. Figures have also been adjusted to account for the Australian Secret Intelligence Service and the Office of National Intelligence as they are not required produce a publicly available annual report, and the Australian National Preventive Health Agency as it is included within the annual report of the Department of Health.

Note a: This is based on the 6 May 2021 PGPA Flipchart which lists 187 Commonwealth entities and companies.

Note b: This is based on the 1 February 2020 PGPA Flipchart which lists 187 Commonwealth entities and companies.

Note c: This is based on the 30 May 2019 PGPA Flipchart which lists 188 Commonwealth entities and companies.

Source: ANAO analysis of Transparency Portal data.

Consistency

4.9 The Transparency Portal accepts free-text in data fields and the ANAO observed inconsistencies with the formatting of information. Table 4.2 shows examples of this variability in formatting. The variability of this formatting complicated comparisons and interpretation of data during the production of this information report.

Table 4.2: Examples of variability in formatting of free-text fields

|

Dataset |

Field |

Examplesa |

|

Details of accountable authority during the year (2020–21) |

Number of meetings of accountable authority |

The below sample illustrates variability with free-text fields. This includes outlining the total number of meetings possible for the accountable authority to attend in a range of different formats.

|

|

Details of director during the year (2018–19) |

Date of cessation |

The below sample illustrates variability with free-text fields. In one instance cessation information was included in the field ‘Date of commencement’.

|

|