Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

COVID-19 Pandemic — ANAO Audit Activity

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Summary

1. Since its emergence in late 2019, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) became a global pandemic that impacted on human health and national economies. A variety of funding and delivery mechanisms were employed by the Australian Government to address the immediate health and economic needs arising from the COVID-19 pandemic. These included income support payments, grants, procurements, loans and tax relief.

2. To support the Australian Government’s COVID-19 pandemic response priorities, the Australian Public Service (APS) quickly adapted its workplace practices and deployed resources to priority areas, while continuing to deliver business-as-usual activities.

3. In 2019–20, eight entities were significantly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and required either additional funding, letters of support or a restructuring of operations.1

4. At the request of the Chief Operating Officers Committee (COO Committee)2, the ANAO developed an Insights product, Rapid Implementation of Australian Government Initiatives, based on key lessons learned from audits of past activities, likely to have wider applicability to the APS in supporting the national COVID-19 pandemic response.3 The product was published on 16 April 2020.

5. The ANAO responded to the emerging sector-wide risks for public administration by developing a strategy for a program of audits examining the delivery of the Australian Government’s COVID-19 pandemic response (COVID-19 audit strategy). This information report summarises and consolidates the learnings from the audits and reviews conducted by the ANAO under the COVID-19 audit strategy.

6. As a public sector entity, the ANAO also adapted its work practices to ensure the continued delivery of its assurance services while safeguarding the health and wellbeing of its staff. The ANAO’s operations were identified as critical during the COVID-19 pandemic as the ANAO supports government accountability and transparency through its independent reporting to Parliament. Financial and performance reporting requirements for government entities — and therefore the audit mandate for the ANAO — remained unchanged during the COVID-19 pandemic, except to the extent accountable authorities considered it not reasonably possible to meet the existing reporting deadlines for their 2020–21 corporate plans and 2019–20 annual reports.4

7. Prior investment in new IT capabilities, including transition to ‘PROTECTED’ cloud services in 2018 and the rollout of laptops and wireless peripherals to staff to facilitate a mobile and connected workforce commenced in early 2019. This investment enabled the ANAO to respond quickly to the COVID-19 pandemic and support the majority of ANAO staff to continue to work remotely, including from home from late March 2020. Entities also assisted the ANAO by making remote access to their systems available to enable audit work to continue.

8. During April 2020, the ANAO implemented an engagement ‘pause’ for performance audits in recognition of the work that audited entities were undertaking to adjust to new working arrangements and, for many, implementing the COVID-19 pandemic response measures announced by the Australian Government. Audits with fieldwork that involved interstate travel — such as the audits on the Northern Territory Land Councils — were put on hold to comply with lockdowns and other public health measures.

9. The engagement pause, while well received within the sector, impacted the delivery of the 2019–20 performance audit program, with the Auditor-General tabling 42 audit reports in the Parliament in 2019–20 against a target of 48.5 The target of 42 performance audits in 2020–21 was met.6 For financial statements audits, the ANAO completed 243 of 249 (98 per cent) mandated financial statements audits for the year ended 30 June 20197 in 2019–20, and 246 of 246 (100 per cent) mandated financial statements audits for the year ended 30 June 2020 in 2020–21.8

10. In the first set of audits conducted under the COVID-19 audit strategy, the ANAO focused its audit approach on identifying areas of risk and emerging lessons for the public sector entities, reflecting the operating environment and challenges associated with rapid implementation of government initiatives. As such, three of four COVID-19 audits tabled in December 2020 did not contain recommendations for the audited entities and identified key messages for Australian Government entities to consider in identifying and responding to the challenges and risks associated with the rapid implementation of initiatives. The key messages were consolidated in an Audit Lessons product on Emergency Management — Insights from the Australian Government’s COVID-19 Response, which was published on 28 May 2021.

11. This information report was developed to summarise and consolidate the lessons from the audits and reviews undertaken by the ANAO under its COVID-19 audit strategy. The APS undertook many activities to support the Australian Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic in sometimes very short timeframes and often on a much larger scale than business-as-usual activities. The lessons from the ANAO’s work can contribute to preparedness for future crisis events. As the themes arising from the COVID-19 performance audits analysed in this report indicate, capturing and implementing lessons learned for continuous improvement is an important element of effective program delivery. Key lessons for planning and responding to crises identified through the ANAO’s audits and reviews conducted under the COVID-19 audit strategy are outlined in Appendix 1.

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in significant disruptions to people’s lives. As at 31 May 2024, Australia recorded 17,920 COVID-19 related deaths nationally.9 Worldwide, 7.05 million COVID-19 deaths were reported to the World Health Organization from 227 countries as at 30 June 2024.10

1.2 The COVID-19 pandemic led to an increase in government spending, as the Australian Government introduced measures to safeguard public health, protect critical infrastructure and support the economy through the global health crisis. According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), over the period 2019–20 to 2021–22, an estimated $47 billion was expended by the Australian Government in health-related COVID-19 activities. The Department of the Treasury (Treasury) reported that the JobKeeper program cost the Australian Government a total of $88.9 billion from 30 March 2020 until it was ceased on 28 March 2021. There were also direct funding packages and subsidies announced throughout the pandemic, including around $13 billion in income support payments provided to individuals affected by state or territory lockdowns or quarantine requirements. As at the March 2022 Budget, the Australian Government reported that it had provided $343 billion in total direct economic and health support since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

1.3 The COVID-19 pandemic also had an impact on the risk environment faced by the Australian public sector. From the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia, the Australian Public Service (APS) had to adapt within a short timeframe to a new operating environment and position itself to handle a surge in demand for government services. This included monitoring and reporting on the evolving situation around the country as well as globally; establishing arrangements to ensure business continuity while deploying staff on a large scale to support critical government functions; and rapidly designing and implementing a new suite of government policies announced during the COVID-19 pandemic. This evolving operating environment was taken into account in the ANAO’s audit work.

1.4 To account for the change in risk environment faced by the Australian public sector, the ANAO developed a multi-year strategy for COVID-19 audits (COVID-19 audit strategy) outlining its approach to auditing COVID-19 related measures being implemented by the Australian Government. The COVID-19 audit strategy was published on the ANAO website in July 2020 and outlined:

- a three-phase work program of performance audits; and

- monthly assurance reviews of the Advances to the Finance Minister (AFM) from April to October 2020.

1.5 The ANAO also produced two Audit Lessons summarising key learnings for dealing with risks arising from the rapid implementation of policy and program initiatives in crisis situations to help guide entities in their COVID-19 pandemic responses:

- Rapid Implementation of Australian Government Initiatives, published 16 April 202011; and

- Emergency Management — Insights from the Australian Government’s COVID-19 Response, published 28 May 2021.12

About this report

1.6 The APS undertook many activities to support the Australian Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic often in very short timeframes and often on a much larger scale than business-as-usual activities. This information report was developed to summarise and consolidate the lessons from the audits undertaken by the ANAO under its COVID-19 audit strategy. The lessons from the ANAO’s work can contribute to preparedness for future crisis events.

1.7 The first part of the report analyses key themes arising from the COVID-19 audits, by the three phases outlined in the COVID-19 audit strategy. It examines the common findings and good practice examples arising from the audits and outlines how the lessons from these audits can be applied to better prepare for and respond to future crises. Appendix 1 outlines key lessons for planning and responding to crises. Appendix 2 lists the implementation status of agreed recommendations made in the COVID-19 performance audits.

1.8 The second part of the report summarises the results of the assurance reviews of AFM undertaken by the ANAO from April to October 2020.

1.9 This information report is not an audit or assurance review report and does not present a conclusion. The report does not provide assurance over the effectiveness or efficiency of the Australian Government’s COVID-19 pandemic response beyond the conclusions reached in the audits tabled in the Parliament examined in this report.

1.10 The report was prepared at a cost to the ANAO of $30,048.

2. COVID-19 audits

Chapter coverage

This chapter examines the 13 performance audits conducted under the ANAO’s multi-year strategy for COVID-19 audits (COVID-19 audit strategy) and the audits of the financial statements of Australian Government entities. It analyses the key themes arising from the COVID-19 audits by the three phases outlined in the COVID-19 audit strategy: early response; program delivery; and readiness for future crises. It focuses on findings and conclusions arising from the audits to draw out key messages and good practice examples for the broader Australian public sector, particularly in preparation for future crises.

Summary

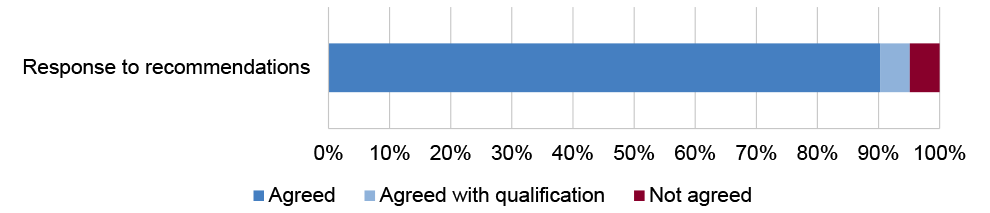

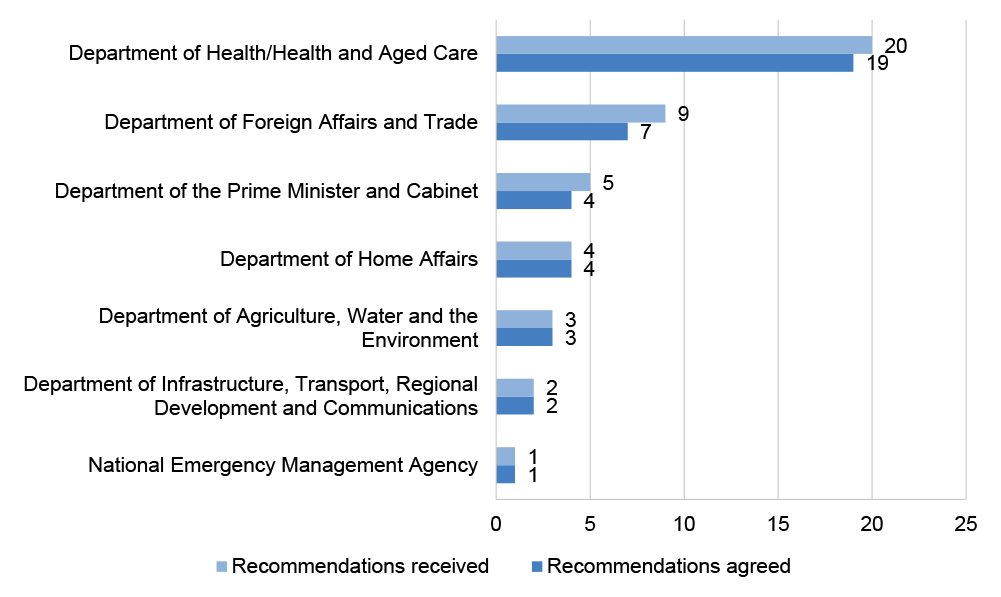

Across 13 performance audit reports, the ANAO examined the performance of 12 entities within 10 portfolios and made 41 recommendations.

The five phase 1 COVID-19 audits examined the Australian Government’s early response to the pandemic. The key themes and lessons that emerged from phase 1 audits emphasised the importance of everyday fundamentals such as establishing appropriate governance arrangements and proactively managing risks. The seven phase 2 audits highlighted that systems and controls that were considered sufficient for business-as-usual were not adequate to deal with the demands of rapid implementation during the COVID-19 pandemic, and necessitated a more disciplined approach to adapt to and manage changes to ensure effective program delivery.

Under phase 3, two elements of crises preparedness and response were emphasised: the need for comprehensive and up-to-date crisis management frameworks; and the importance of incorporating and actioning lessons learned from the experience. Notably, these elements reflect some of the key themes that emerged in phase 1 audits. Effective preparation for future crises enables a more effective and efficient response when crises occur.

Background

2.1 The ANAO’s performance audit activities involve the independent and objective assessment of all or part of an entity’s operations and administrative support systems. Performance audits may involve multiple entities and examine common aspects of administration or the joint administration of a program or service.

2.2 The ANAO conducted 13 performance audits under the COVID-19 audit strategy. Across these audit reports, the ANAO examined the performance of 12 entities within 10 portfolios and made 41 recommendations (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1: Performance audits conducted under the COVID-19 audit strategy

|

Audit title |

Entity/entities audited |

Audit conclusion |

Tabled date |

|

Phase 1 — early response |

|||

|

Australian Public Service Commission (APSC); Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) |

Effective |

1/12/2020 |

|

|

Department of Health (Health); Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources (DISER) |

Largely effective |

10/12/2020 |

|

|

Services Australia |

Largely effective |

10/12/2020 |

|

|

Australian Taxation Office (ATO) |

Effective |

14/12/2020 |

|

|

Health; DISER |

Largely effective |

27/05/2021 |

|

|

Phase 2 — program delivery |

|||

|

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT); Health; Department of Home Affairs (Home Affairs); Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications (DITRDC); PM&C |

Largely effective |

8/12/2021 |

|

|

Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment (DAWE); Health; Home Affairs; DITRDC |

Largely effective |

24/03/2022 |

|

|

Auditor-General Report No. 22 2021–22 Administration of the JobKeeper Scheme |

Department of the Treasury (Treasury); ATO |

Largely effective |

4/04/2022 |

|

DFAT |

Partly effective |

21/06/2022 |

|

|

Auditor-General Report No. 40 2021–22 COVID-19 Support to the Aviation Sector |

DITRDC |

Largely effective |

22/06/2022 |

|

Auditor-General Report No. 3 2022–23 Australia’s COVID-19 Vaccine Rollout |

Health |

Partly effective |

17/08/2022 |

|

Auditor-General Report No. 10 2022–23 Expansion of Telehealth Services |

Health |

Largely effective |

19/01/2023 |

|

Phase 3 — readiness for future crises |

|||

|

Auditor-General Report No. 5 2024–25 Australian Government Crisis Management Framework |

PM&C; National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) |

Largely effective |

21/10/2024 |

Source: ANAO summary of COVID-19 performance audits. A list of the audits can be found on ANAO website: https://www.anao.gov.au/work-program/covid-19.

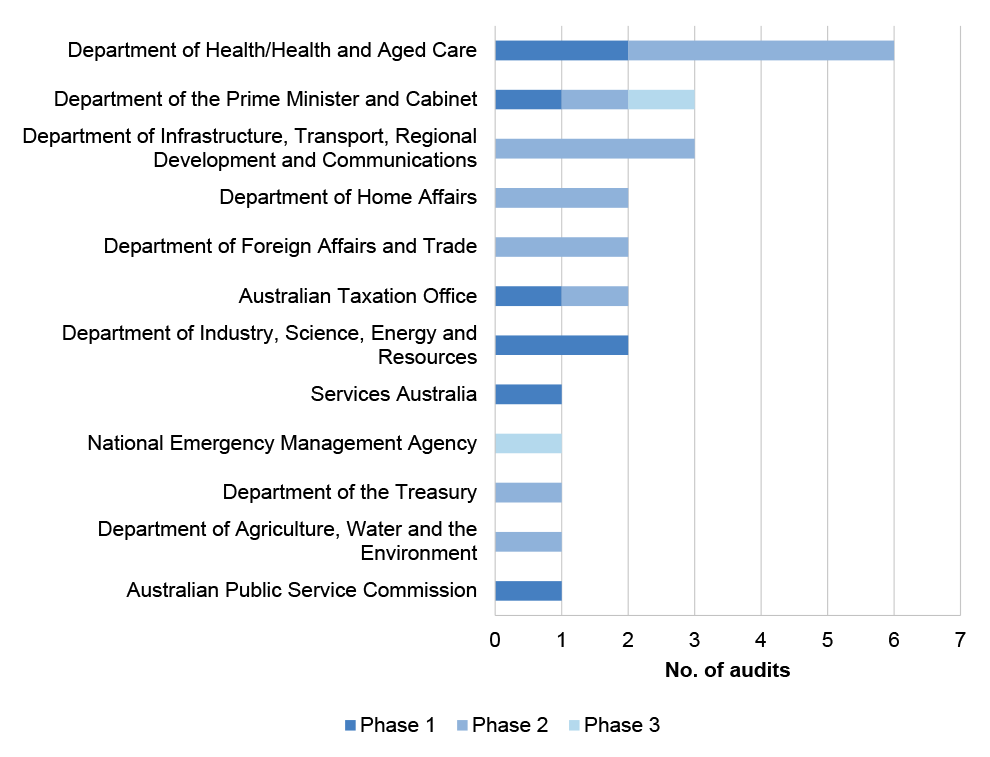

2.3 The Department of Health (and its successor Health and Aged Care) was involved in the highest number of audits (six audits), followed by PM&C and DITRDC at three audits each (Figure 2.1). PM&C was audited under all three phases of the COVID-19 audit strategy.

Figure 2.1: Entities involved in COVID-19 performance audits

Source: ANAO summary of COVID-19 performance audits.

Key themes arising from COVID-19 performance audits

Phase 1 — early response

2.4 The five phase 1 COVID-19 audits examined the Australian Government’s early response to the pandemic. They examined whether the entities had sufficient planning, including pre-pandemic planning where appropriate, to inform their COVID-19 pandemic responses; and how they adapted to and managed the changing risk environment in which they were operating to deliver on government priorities. The audited entities were: APSC, PM&C, Health, DISER, Services Australia, and the ATO.

2.5 The key themes and lessons that emerge from phase 1 audits largely reflect the good practice observed by the ANAO in non-crisis situations. That is, entities that responded effectively to the COVID-19 pandemic: focused on establishing appropriate governance structures; proactively managed risks; developed fit-for-purpose frameworks or policies; and considered assurance, review or evaluation mechanisms early in their response arrangements to capture lessons learned and for continuous improvement.

Governance structures

2.6 Entities had generally established sound governance structures. A ‘taskforce’ model was a common structure adopted by the entities for governance and delivery in the early stages of their response to the COVID-19 pandemic. According to the APSC:

Taskforces bring people together for a limited period of time to focus on addressing specific problems across organisational or functional boundaries. They are an important part of the Australian Public Service (APS) landscape and are commonly used to tackle high-priority issues.13

2.7 The APSC established a COVID-19 Taskforce to provide consolidated guidance to APS staff, and a Workforce Management Taskforce to facilitate the deployment of APS employees to support critical functions. Health and DISER both implemented a taskforce approach for the National Medical Stockpile (NMS) procurements, with Health establishing three procurement teams and DISER establishing four taskforces focusing on masks, Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), test kits and ventilators. Services Australia established a COVID-19 Taskforce to provide general coordination, identify critical functions and oversee initial work health and safety matters.

2.8 The relevant taskforces and teams reported to existing or ‘bespoke’ executive bodies, and facilitated reporting to other stakeholders such as ministers and the Parliament.

2.9 The phase 1 audits found examples of good practice in relation to these structures. In establishing governance arrangements, it is important to consider where legislative authority is vested so that decisions can be made by the appropriate decision-maker.14 The audit of APS workforce management15 noted that the APSC’s governance arrangements for the two taskforces were appropriate and consistent with the APS Commissioner’s responsibilities under the Public Service Act 1999. The Chief Operating Officers (COO) Committee16, which oversaw the two taskforces, played an advisory role as it did not have decision-making power over APS workforce matters. The APS Commissioner remained responsible for decisions relating to the taskforces. These arrangements ensured clarity of roles and responsibilities for the pandemic response.

2.10 Keeping sufficient documentation of decision-making processes and outcomes is a requirement of Commonwealth legislation17, as well as fundamental to effective governance, accountability and transparency.18 In emergency situations where critical decisions are being made in-flight, it is important to ensure they are still being captured and documented. In the Services Australia audit19, the ANAO noted that Services Australia maintained good records of its key governance forums.

- Meeting minutes of its Executive Committee captured key areas of discussion as well as key actions agreed.

- There were minutes of daily meetings with the minister that reflected discussion and input from relevant attendees.

- The Stimulus Multi-disciplinary Team, established to manage the design and delivery of the COVID-19 stimulus packages, produced status reports which included a register that captured issues, risks and key decisions.

- The Command Centre, which managed and authorised the release of system changes required to support the stimulus payments, maintained a log outlining risks, issues, actions and key decisions, and tracked progress against a timeline.

2.11 In mid-April 2020, Services Australia developed an operational policy for documenting ministerial and senior executive decisions made during the COVID-19 pandemic. The policy stated that all COVID-19 pandemic actions requiring a ministerial decision must be submitted to the minister’s office through normal ministerial and parliamentary process, and identified ‘acceptable mechanisms’ for documenting decisions requiring CEO approval, such as via briefs, emails and records of meetings. A ‘decisions assurance report’ was produced in May 2020 containing a total of 56 decisions made since March 2020. This enabled key decisions relating to Services Australia’s COVID-19 pandemic response to be recorded for transparency and accountability.

2.12 Leveraging existing governance mechanisms can provide an effective means to support the rapid implementation of measures, and reduce the administrative burden on the entity for standing up new arrangements during crisis situations.20 The ANAO observed in the audit of the ATO’s management of risks21 that the ATO largely drew on its existing governance committees and processes to deliver on the new COVID-19 pandemic policy measures, and introduced specific additional structures where needed. The ATO also used its internal audit staff to support the measure-specific project teams by establishing ‘decision logs’ for each of the measures. This demonstrated an efficient use of existing resources to provide for fit-for-purpose accountability, oversight and reporting arrangements.

Risk management

2.13 The phase 1 entities’ performance in relation to risk management was mixed.

2.14 Audits of Services Australia and the ATO were largely positive regarding their risk management practices. Services Australia drafted a revised pandemic risk management plan in March 2020 and developed risk management plans specific to its COVID-19 pandemic response, which also captured changes in business-as-usual risks due to COVID-19 pandemic impacts or activities. The risk management plans reviewed in the audit were completed using the agency’s standard risk management template and included overviews of the strategic context, as well as risk controls, risk level rating, risk owner and proposed treatments where appropriate.

2.15 The Services Australia audit noted that risks were communicated to the responsible minster, the agency’s executive, committees, staff and other entities, and that there was evidence that risks were considered and actions arising were documented. While one risk management plan met its scheduled review date, three out of five examined by the ANAO were reviewed and there was evidence of ongoing consideration and review of risks including by the Executive Committee and the minister.

2.16 The ATO used risk registers for early and iterative risk management for the relevant measures it was delivering, and then prepared risk plans ‘post-decision’ to retrospectively capture a consolidated view of its risk management. Information on risk profiles and a summary of the risk and decision process for each measure was provided to the ATO’s Executive Committee. The audit also commented on a good practice example of shared risk management by the ATO as part of the JobKeeper Program Risk and Integrity Working Group.

2.17 The APS workforce audit and the two audits on the National Medical Stockpile (NMS)22 found that there was room for improvement in the entities’ risk management practices. The APS workforce audit noted that a whole-of-government plan for managing APS workforce risks in a crisis had not been developed. Consequently, key workforce risks — arising from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic directly on staff and in managing government response to the pandemic — were largely managed reactively.

2.18 Two working groups — on assurance and risk — were established by the COO Committee and delivered papers that contained useful insights and analysis. However, the audit noted that neither group conducted structured analysis of shared APS-wide risks from COVID-19 with the aim of identifying opportunities to strengthen existing controls or establish mitigation strategies.

2.19 Similarly, the audit found that neither the COVID-19 Taskforce nor the Workforce Management Taskforce conducted a structured risk assessment at commencement in line with APSC’s risk framework. This meant that some risks were proactively managed, and other risks were managed reactively after issues emerged and were brought to the attention of the taskforces.

2.20 The NMS audits found varying levels of risk management activities by Health and DISER in relation to NMS procurement. Both Health and DISER applied their existing risk tolerance and appetite levels to the COVID-19 pandemic procurement processes. Health did not complete an overarching risk profile for the COVID-19 procurements of the NMS as required by its procurement plan template. DISER established a risk management plan for DISER taskforces involved in procurements in April 2020.

2.21 Both Health and DISER considered risks to the proper use of public resources and achievement of procurement outcomes throughout their procurement-related activities. However, none of the mask or PPE procurements tested in the audit had a documented risk or contract management plan, and an NMS risk register had not been updated since it was initially drafted in 2015.

2.22 Crisis situations can impose an imperative to commence implementation as soon as possible to ensure delivery of essential services and government priorities within tight timeframes. However, it is critical to the successful delivery of government initiatives to proactively consider and manage risks. Time spent upfront on developing a fit-for-purpose risk plan can mitigate the need to react to unforeseen risks or issues during implementation. Like Services Australia, entities should not only consider new risks arising due to the changing environment, but also assess the impact of the crisis on business-as-usual risks, which may increase in likelihood or have a higher consequence if realised. Like the ATO, if a contemporaneous formal risk assessment is difficult to establish from the outset due to lack of resources or time, managing risks via a risk register or alternative means and documenting risk management approaches later can also be an option.

Frameworks and planning

2.23 Phase 1 audits emphasised the importance of having appropriate frameworks in place to ensure crisis preparedness. Having relevant protocols in place prior to an emergency helps entities focus their attention on the emergency response without needing to divert resources to establish systems and procedures in-flight.

2.24 The nature of the COVID-19 pandemic meant that most of the existing frameworks in the public sector were not wholly suited to dealing with the situations that emerged. For instance, the APS workforce audit noted that existing whole-of-government crisis management documents23 did not include information on managing the APS workforce in response to a pandemic. Similarly, Services Australia’s pandemic plans did not fully consider the level of action required to manage a pandemic on the scale of the COVID-19 pandemic, with the plans focusing on responding at an operational level to minimise impacts on business-as-usual activities and provide services on behalf of other entities, but not fully reflecting the potential scale of impact on Services Australia’s staff and consequential capacity to deliver. The NMS audit stated that there were no planning documents that set out operational principles or specific protocols for an emergency procurement of medical supplies for the NMS or for a coordinated national response to procurement in business as usual or emergency conditions.

2.25 When existing frameworks are not suited to addressing the needs of the entity during a crisis, adequate planning becomes critical. As noted in the APS workforce audit:

In such circumstances, planning documentation does not need to be elaborate. It is more important to apply a structured process to planning key aspects of the project (such as governance, risk and stakeholder engagement).24

2.26 The NMS audit noted that although Health did not develop a single strategic or operational procurement plan for the COVID-19 NMS procurements, elements of a plan were contained in various documents, including procurement objectives, timeframes and procurement method. Similarly, DISER’s procurement taskforces managed planning via operational plans, templates for email correspondence, process maps, and procurement checklists.

2.27 Both the ATO and Services Australia undertook early planning to identify and obtain required resources and capabilities for the delivery of new measures. On 26 March 2020, the Prime Minister issued a direction requiring all APS agency heads to identify critical functions and staff available for temporary deployment. Before this direction was issued, on 17 March 2020, the ATO had tasked its groups to collate a list of both critical functions that would be a priority for staffing, and those functions that could cease work immediately and redeploy to support priority areas. Similarly, Services Australia’s COVID-19 Taskforce had met on 19 March 2020 to prepare a plan identifying critical roles across Services Australia functions and the minimum staff required to continue delivering these critical functions. Services Australia also undertook an agency-wide skills survey in March 2020 to identify staff with skills to process claims to help meet additional demand in those functions.

2.28 As these cases demonstrate, clear assessment of business priorities and early planning can help support an appropriate crisis response.

Review and evaluation

2.29 The Australian Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic provided an opportunity for the public sector to learn from its experience to be better prepared for future crises. Phase 1 audits particularly emphasised the benefits of establishing review and evaluation mechanisms early during planning, and as responses were implemented, to incorporate feedback and learnings into their activities.

2.30 The APS workforce audit reported that the COO Committee established a Lessons Learned Working Group in April 2020. The Working Group presented a paper to the COO Committee in July 2020 reviewing operations from May to June 2020 to inform and embed improvements post the COVID-19 pandemic. In April and May 2020, the APSC COVID-19 Taskforce undertook targeted consultation with officers from agency HR teams seeking feedback on its COVID-19 advice and guidance, which allowed them to adjust and improve on their approach for subsequent guidance released.

2.31 Services Australia engaged an external consultant in May 2020 to validate key action and risk plans underpinning the agency’s response to COVID-19 and develop a suite of new pandemic planning documents. Services Australia also commissioned external reviews of its health and aged care programs pandemic response, and of its workplace health and safety strategies; conducted a major incident review of the myGov system degradation; and completed a review of its response to a site closure following reporting of a confirmed case of COVID-19.

2.32 The phase 1 audits also highlighted the importance of implementing the recommendations and lessons from these reviews in a timely manner. The NMS audits noted that various audits and reviews of the NMS since 2007 have commented on consideration of risk in NMS procurement planning, but risk was not fully incorporated into NMS planning frameworks. A 2010–11 Department of Finance review of the NMS, and a 2011 Health review of Australia’s response to the 2009 H1N1 (swine flu) pandemic, had identified a need for better information sharing between Health and the states and territories regarding available inventory and distribution, and inconsistencies and communication issues between jurisdictions regarding the NMS and stockpiling responsibilities. These issues remained largely unaddressed at the time of the COVID-19 pandemic response, which meant they had to be managed in-flight.

2.33 Commissioning and conducting reviews is an important step in capturing lessons learned for future planning; however, adequately addressing the review findings and implementing agreed recommendations in a timely manner is required to realise the full benefit of those reviews. Frameworks and policies should be revised to incorporate the new learnings and kept updated to ensure they remain fit for purpose.

Phase 2 — program delivery

2.34 There were seven phase 2 COVID-19 audits examining the performance of eight entities: Health25; PM&C; DITRDC26; Home Affairs; DFAT; ATO; Treasury; and DAWE.27 The phase 2 audits focused on the three main stages of program delivery — design; implementation; and performance measurement and evaluation — in the context of rapid response required in crisis situations.

2.35 Compared to phase 1 audits, which highlighted the importance of everyday fundamentals for an effective early response to the pandemic, lessons from phase 2 audits emphasised the different arrangements required in crisis situations compared to non-crisis situations. Some systems and controls that were considered sufficient for business-as-usual were not adequate to deal with the demands of rapid implementation during the COVID-19 pandemic. This was particularly evident in entities’ efforts to: ensure effective coordination with other entities; mobilise the required workforce and capability for implementation; establish performance measurement arrangements; and conduct effective stakeholder engagement and communication activities.

Coordination between entities

2.36 A notable theme emerging from phase 2 audits was the need for effective coordination arrangements between entities, and often between jurisdictions, in implementing the relevant COVID-19 pandemic measures. Managing Australia’s international travel restrictions required the involvement of five Australian Government departments — Health, Home Affairs (including the Australian Border Force), PM&C, DFAT and DITRDC. Human biosecurity practices for international air travel similarly required close coordination between Health, DAWE (now the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry), Home Affairs, DITRDC, and state and territory human health biosecurity officers. The ATO engaged closely with Treasury in its administration of JobKeeper payments, and Treasury’s role in turn involved reporting JobKeeper data to other government entities, including PM&C for forwarding to state and territory agencies. DFAT led an interagency taskforce to assist Australians to return from overseas. The administration of the COVID-19 vaccine required Health to coordinate its rollout with state and territory health authorities, and the introduction and expansion of telehealth services required a change to the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS), which is jointly administered by Health and Services Australia.

2.37 Phase 2 audits found that audited entities generally undertook adequate coordination and information sharing during the pandemic, but that better documentation of coordination arrangements would have enhanced role clarity, accountability and efficiency of their joint activities. For example, the human biosecurity audit28 noted that a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) was in place between Health and DAWE relating to human health biosecurity arrangements, however details regarding human biosecurity emergency response services were intended to be covered in a separate schedule that was drafted and not finalised. The audit stated:

The absence of pre-planned contingency arrangements for human biosecurity emergencies contributed to an initially indistinct allocation of responsibility between DAWE and state and territory healthcare workers deployed to airports.29

2.38 The airport corporations interviewed in the audit expressed that the absence of a nominated lead from either the Australian Government or state and territory governments complicated the implementation of arrangements to process passengers into mandatory quarantine. The audit noted that following this initial period, appropriate local coordination arrangements and inter-agency working relationships were established to support the processing of passengers into mandatory quarantine.

2.39 Similarly, the audit on international travel restrictions30 noted that largely appropriate coordination arrangements were established between entities, including by deploying liaison officers to other entities’ COVID-19 response teams, and establishing various bodies — such as interdepartmental committees (IDCs) and working groups — at different levels for coordination and information-sharing. The audit found, however, that not all arrangements were fully effective — in particular, there was a high number of working groups and IDCs established without terms of reference to clearly articulate their purpose and scope of work, with unclear reporting lines, and undocumented meeting minutes and action items, which reduced their effectiveness.

2.40 A good practice in relation to documentation of roles and responsibilities was observed in the COVID-19 vaccine audit.31 It noted that Health had set out the high-level responsibilities of the Australian, state and territory governments and other key stakeholders in the Australian COVID-19 vaccination policy, as well as in the Jurisdictional Implementation Plans agreed with each state and territory, and in the implementation plans developed for specific sectors such as residential aged care and people with disabilities. This enabled a clear understanding of the role of each participant in relation to the program, and aided in the rollout of the vaccines across the country during the height of the pandemic.

2.41 In a business-as-usual environment, ad hoc or informal arrangements based on established practice or working relationships may be sufficient to coordinate joint activities between entities or jurisdictions. However, in a crisis situation clarity of roles and responsibilities becomes critical for effective coordination. Usual staff may not be available as they, too, are affected by the crisis, or entities may receive a surge workforce inexperienced in the relevant practice area. Different reporting and accountability arrangements may be established involving bespoke committees or new leadership positions, and the scale or nature of a crisis may require entities to work with a body or a sector that they have not previously engaged with. In these circumstances, counting on business-as-usual arrangements to see them through or hoping that adequate processes will eventually be established will not be sufficient. Adopting a disciplined approach to documenting the required changes to responsibilities, processes and operational requirements to meet the needs of the crisis will allow entities to deliver a more efficient and effective response.

Workforce and capability

2.42 Phase 1 audits noted the importance of early planning to identify and obtain required resources and capabilities for the delivery of new measures. In phase 2, a number of audits highlighted the importance of establishing sufficient processes and controls to ensure these resources and capabilities are deployed in a manner that is effective, efficient and compliant with legislative requirements.

2.43 A well-trained workforce is a key asset in a crisis. Ensuring that staff assigned to relevant roles have obtained the required qualifications and completed their mandatory training provides assurance that they have the capability to perform their duties to the expected standard. Identifying and monitoring the completion of training requirements is also critical to business continuity planning. It is important for entities to consider whether there is a suitably qualified and sufficiently trained pool of staff to call upon in emergencies to ensure continued delivery of critical functions while meeting the demands of a crisis response.

2.44 Phase 2 audits found some shortcomings in relation to entities’ monitoring of required training and qualifications for their staff. The human biosecurity audit found that Health did not check for training and qualifications required under legislation when appointing human biosecurity officers, and that mandatory training introduced by Health and DAWE for their respective cadre of biosecurity officers were not completed by all officers.

2.45 The audit into DFAT’s crisis management arrangements32 found that the compliance rates for the completion of mandatory crisis management training for staff who were due to be deployed were 95 per cent in 2020 and 99 per cent in 2021. The audit noted that:

DFAT does not monitor or report on conformance with mandatory consular and crisis management training requirements beyond training required for deployment overseas. There is no consolidated reporting on training for non-deployed staff.33

2.46 Further, the audit stated that it was unclear whether DFAT’s crisis management training was fit for purpose because DFAT had not specified the competencies expected of its workforce.

2.47 Systems and IT capability is another key success factor in the rapid implementation of programs. Appropriate automation of manual processes can reduce administrative burden, increase efficiency, and support accurate and timely monitoring and reporting of progress.

2.48 The ANAO routinely comments on the risks associated with using manual spreadsheets to administer key government programs in its audits. Spreadsheets lack change and version controls, increasing the risk of data integrity errors, and often contain unstructured or inconsistently formatted information, making analysis and reporting difficult. In phase 2 audits, the ANAO observed the benefits of entities developing an IT system to replace their manual processes to support their implementation and monitoring activities.

2.49 In July 2020, to better manage international travel exemption requests, Home Affairs developed a Travel Exemption Portal (TEP) to replace the use of emails and spreadsheets, with enhancements made in December 2020 to improve its efficiency and functionality. The audit noted that the TEP enabled Home Affairs to: triage and track exemption cases through largely automated workflows; identify previous cases from an applicant and consolidate concurrent cases; and conduct more comprehensive reporting on travel exemption processing, including the ability to report on timeliness.

2.50 The human biosecurity audit noted that at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the traveller with illness checklist (TIC) was a paper-based form completed by biosecurity officers when attending an aircraft, which was then scanned into DAWE’s electronic records and emailed to Health. In November 2020 an electronic version of the TIC (eTIC) was deployed to smart devices carried by the biosecurity officers, using a smart form technology to ensure the checklist is completed correctly and automatically submitted to Health. Similarly, at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic DFAT overseas posts used spreadsheets to track the number of Australians registered with the department. In April 2020, DFAT implemented the Traveller Registration System, which was an online portal on the Smartraveller website used for registering and monitoring Australians overseas seeking to return to Australia.

2.51 When developing and deploying new IT systems, it is important to ensure that appropriate controls are put in place to protect the integrity, privacy and security of the data collected using these systems. Weaknesses in IT general controls is a common finding in the ANAO’s financial statements audits, and phase 2 audits also observed opportunities for entities to improve in this area. The TEP allowed Home Affairs to process travel exemption requests more efficiently. The audit noted some weaknesses in TEP system controls, including indications that cases had been deleted from TEP, which meant that Home Affairs could not have assurance over the completeness and accuracy of its travel exemption data. The audits of COVID-19 vaccine rollout and telehealth services34 commented on Health’s outsourcing of data collection and IT management to other parties, and noted that Health did not have assurance that third parties had IT controls in place to ensure the confidentiality, integrity and availability of data, which remained its responsibility under various pieces of legislation.

2.52 Effective deployment of workforce and capability for an emergency response can be challenging due to the fast-changing nature of a crisis and tight timeframes required for implementation of measures. In these circumstances, the required resources and essential training needs should be identified as quickly as possible to ensure that staff are adequately supported to perform their roles in line with legislative requirements. Similarly, as phase 2 entities have demonstrated, manual processes such as emails and spreadsheets should be a temporary workaround while necessary IT system enhancements to support rapid program delivery are quickly identified and addressed. Entities should always maintain a focus on their internal controls to manage the risks relating to data integrity and security.

Performance measurement

2.53 Performance measurement plays a role in ensuring delivery and providing accountability to the Parliament and the government. At its simplest, a performance framework is the means by which an entity can see how it is performing against its objectives. It is a key tool for strategic planning because it requires a clear articulation of what the entity is trying to achieve and how success will be measured and assessed — which is crucial in a fast-moving environment where competing, and at times conflicting, priorities can arise.

2.54 One of the lessons arising from phase 1 audits was the benefit of establishing review and evaluation mechanisms early during planning to incorporate feedback and learnings into program activities. Phase 2 audits showed the importance of establishing a robust performance measurement framework to support and supplement the work of these reviews.

2.55 The ATO’s administration of JobKeeper scheme35 stood out as an example of good practice in relation to performance measurement. The ATO provided a paper to the JobKeeper Program Board in its first April 2020 meeting, outlining its intentions to establish monitoring and reporting of key performance indicators and milestones to support the government’s policy objective. The audit noted that the ATO monitored and reported internally on its performance in a number of different reports throughout the administration of the program.

2.56 In February 2021, the ATO presented a paper to the JobKeeper and JobMaker Hiring Credit Program Board on what effective ATO administration would look like and proposed five performance criteria for the JobKeeper scheme. The audit noted that the five performance measures were first reported on, in draft, to the JobMaker Hiring Credit Steering Committee on 27 July 2021, providing a provisional assessment of performance against the five measures.

2.57 Other phase 2 audits found that there was room for improvement in entities’ performance measurement frameworks. The telehealth audit found that Health did not establish performance measures for the expansion of telehealth services or identify what data would be necessary to measure performance. It also did not document the allocation of roles and responsibilities for monitoring performance, the frequency and format of performance reporting, or the approval of these arrangements by senior officials.

2.58 Similarly, the human biosecurity audit noted that service agreements between Health and state and territory governments for human biosecurity services did not specify performance indicators or measures of performance. The audit further noted that:

With the exception of electronic traveller with illness checklists (eTICs), Health does not obtain regular performance reporting from DAWE on the exercise of regulatory powers or functions under the Biosecurity Act in relation to human biosecurity. The Health–DAWE MOU does not provide for the regular provision of performance data or periodic performance reporting.36

2.59 The audit stated that DAWE’s ability to provide performance information to Health was constrained by inadequate record keeping for human biosecurity functions undertaken by its biosecurity officers, most of which were compiled manually in spreadsheets.

2.60 The audit examining COVID-19 support to the aviation sector37 noted that while DITRDC established consistent processes to review the performance of individual support measures, it did not define monitoring at an objective or aggregated level. The audit stated:

Given the number of measures established to support the aviation sector, and the interrelationships between the measures, there would be value in the department establishing a framework to monitor and evaluate the collective performance of the measures in achieving the Australian Government’s objectives.38

2.61 When designing and implementing government initiatives in an unfolding emergency, it can be tempting to relegate performance measurement and monitoring to the back of mind and focus on the logistics of immediate delivery. However, high-quality performance information is a valuable strategic asset that should be used in all situations, including in a crisis, as it can help entities determine if they are achieving their objectives, provide assurance that they are making the best possible use of their resources, and identify and manage risks and issues as programs are implemented. Performance frameworks also support transparency and accountability, which remain critical in crisis situations that often bring about increased government spending and significant levels of intervention into the community. Entities should incorporate performance measurement and monitoring as an integral part of all business planning activities, including in frameworks for crisis preparedness.

Stakeholder engagement and communication

2.62 Unlike in business-as-usual circumstances, crisis situations requiring rapid development and implementation of government initiatives can make comprehensive stakeholder engagement challenging. Phase 2 audits highlighted instances where entities were required to implement and operationalise changes at very short notice, sometimes within 24 hours. During the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, some decisions were announced to the public via the daily press conferences or ministerial media releases before they were communicated to operational staff to be implemented. This limited opportunities for entities to conduct broad consultation, and receive and consider advice from experts and other stakeholders on implementation risks. It also created challenges for operational or coordinating bodies as they were not always prepared to implement the changes or respond to questions from the public.

2.63 Noting the pace at which the measures were developed during the early stages of the pandemic response, phase 2 audits commented positively on some entities’ efforts to consult on the design of the relevant measures with key stakeholders. The audit examining COVID-19 pandemic support to the aviation sector noted that DITRDC relied primarily upon representations made by industry (for example, via letters and emails), which had been received following the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, as the mechanism for determining the industry position on potential support mechanisms. It consulted with the aviation sector predominantly through email, telephone or virtual meetings, and engaged with other government entities regarding the development of the Australian Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic and in the design of various measures.

2.64 Similarly, the telehealth expansion audit noted that the introduction of temporary telehealth services in March 2020 was not subject to a formal or structured consultation process, reflecting the short period in which rapid changes were required.

However, during the 28-day period in which the fundamental policy options for temporary telehealth were developed and implemented, Health discussed telehealth proposals with primary health care stakeholders at ad hoc and standing meetings used to share broader information on the COVID-19 pandemic response.39

2.65 For the subsequent proposal to make telehealth services permanent, Health consulted with General Practitioners and allied health providers under a stakeholder engagement strategy developed for the Primary Health Care 10 Year Plan. Health engaged with four peak bodies to request suggestions for policy settings and seek support for the Australian Government’s primary healthcare reform package, and held meetings and sought feedback from seven peak bodies on proposed policy options.

2.66 DITRDC and Health’s consultation activities show different ways to consult within constrained timeframes. Use of standing, ad hoc or informal arrangements can be practical ways to discuss policy proposals and share information with stakeholders. Where broad public consultation is not possible, identifying and engaging with industry peak bodies or representative organisations can be an efficient way to determine broader sector views on various issues.

2.67 In a rapidly changing environment, people look to government entities as a source of authoritative information. There is an obligation on administering entities to clearly communicate the elements of new initiatives and programs they are implementing to stakeholders and the broader community. Phase 2 audits found examples of good practice in relation to entities’ communication activities. Most entities used their websites as their primary channel to disseminate information. The audits found that the relevant websites generally contained links to other relevant Australian, state and territory government websites, and were updated regularly to reflect policy changes.

2.68 Entities also took measures to ensure their communication was accessible. For instance, the international travel restriction audit noted that Home Affairs provided information in 18 languages other than English on its website. Similarly, DAWE provided guidance for airline and aircraft operators on its website, including multimedia files containing mandatory passenger announcements in Arabic, Cantonese, French, Hindi, Japanese, Korean and Mandarin. DFAT’s Smartraveller website provided general advice in seven languages.

2.69 Other common channels of communication included factsheets; social media; emails; and call centre functions. Some entities established communication strategies or plans to guide their communication activities. DITRDC developed communication plans for aviation sector support measures that targeted airlines, outlining communication activities, key messages, communication channels, objectives and timelines. Health developed a communication strategy for the rollout of the COVID-19 vaccine, which the audit noted was evidence-based, informed by market research on vaccines and COVID-19, including monitoring of public sentiment, and expert advice on communication materials and appropriate channels for target audiences. Health’s communication strategy also considered communication and rollout risks.

2.70 Communication is a two-way process, and it is important for entities to establish appropriate channels to receive feedback on the effectiveness of their activities for continuous improvement. Phase 2 audits found shortcomings in relation to entities’ management of complaints. The international travel restriction audit observed that the Commonwealth Ombudsman reviewed complaints regarding Home Affairs’ management of travel exemption processes, and noted that the ‘lack of access to an effective complaint mechanism’ was a ‘recurring theme in the complaints’ it had received. The existing complaints mechanism provided by Home Affairs was found by the Ombudsman to be ‘not effective in providing or facilitating a better explanation of decisions’.40

2.71 In the aviation sector support audit, the published grant guidelines for the relevant programs instructed complainants to contact DITRDC’s governance team rather than the program teams, which was inconsistent with the department’s complaints management policy. In response to an internal audit in June 2021, the department committed to developing a formal, consistent process for managing complaints, and the department’s governance board instructed that program teams should develop logs of complaints received and respond to complaints within 10 days. The audit noted that no program teams developed complaints logs, and that subsequent grant guidelines continued to refer complainants to the governance team.

2.72 The audit on DFAT’s crisis management arrangements noted that DFAT did not have a department-wide complaints management policy and process, or standard processes for complaints handling across its overseas network of posts. It noted that:

[DFAT] cannot report on the total number of complaints received and whether these were appropriately managed or identify common themes in complaints. The scope for DFAT to address systemic problems on the basis of information obtained through complaints and improve the delivery of consular services is limited.41

2.73 Entities in phase 2 audits utilised both existing and bespoke arrangements to consult and communicate with their key stakeholders during program delivery. Like most elements of program delivery, business-as-usual arrangements for stakeholder consultation and communication may not always be sufficient to meet the entity’s needs in a crisis. In these circumstances, reassessing the needs and adapting the arrangements to suit the entity’s current purposes will help keep stakeholders and the community informed of government policy settings and delivery arrangements. Entities should also ensure that there are adequate channels established to receive feedback and monitor complaints.

Phase 3 — readiness for future crises

2.74 Phase 3 of the ANAO’s COVID-19 audit strategy focused on the Australian Government’s readiness for future crises. The ANAO conducted one audit under phase 3 on PM&C and NEMA, examining whether the Australian Government has established an appropriate framework for responding to crises.42 For the purpose of analysis in this section, the ANAO also drew upon lessons on crisis preparedness and response identified by other audit offices in Australia and around the world, as well as other reviews into the COVID-19 pandemic and disaster management that had been undertaken by various bodies over the past few years (Table 2.2). These are collectively referred to as ‘COVID-19 pandemic lessons learned publications’ in this section.

Table 2.2: Other publications and reviews examined for phase 3 analysis

|

Entity |

Publication title |

Published date |

|

Audit office publications |

||

|

Office of the Auditor-General of Canada (OAG Canada) |

Pandemic Preparedness, Surveillance, and Border Control Measures |

March 2021 |

|

Tasmanian Audit Office |

COVID-19 – Pandemic response and mobilisation |

March 2021 |

|

UK National Audit Office (NAO) |

Initial learnings from the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic |

May 2021 |

|

Audit Office of NSW (NSWAO) |

Coordination of the response to COVID-19 (June to November 2021) |

December 2022 |

|

New Zealand Office of the Auditor-General (NZ OAG) |

Co-ordination of the all-of-government response to the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 |

December 2022 |

|

US Government Accountability Office (GAO) |

COVID-19: GAO Recommendations Can Help Federal Agencies Better Prepare for Future Public Health Emergencies |

July 2023 |

|

Other reviews |

||

|

Royal Commissioners (Air Chief Marshal Mark Binskin AC (Retd); the Honourable Dr Annabelle Bennett AC SC; and Professor Andrew Macintosh) |

Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements |

October 2020 |

|

Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade |

Inquiry into the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for Australia’s foreign affairs, defence and trade |

December 2020 |

|

Senate Select Committee on COVID-19 |

Senate Select Committee on COVID-19 – Final report |

April 2022 |

|

Hon. Professor Jane Halton AO PSM |

Review of COVID-19 Vaccine and Treatment Purchasing and Procurement |

September 2022 |

|

Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) |

Report 494: Inquiry into the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s crisis management arrangements |

March 2023 |

|

House of Representatives Standing Committee on Health, Aged Care and Sport |

Inquiry into Long COVID and Repeated COVID Infections |

April 2023 |

Source: ANAO summary.

2.75 There were two common elements of crises preparedness and response that were emphasised across these publications: the need for comprehensive and up-to-date frameworks for emergency preparedness; and the importance of incorporating and actioning lessons learned from the experience. Notably, these elements reflect the key themes that emerged in phase 1 audits, on the importance of having appropriate frameworks and plans in place for an effective crisis response; and ensuring that there are review and evaluation arrangements to capture lessons learned and for continuous improvement. Effective preparation for future crises enables a more effective and efficient response when crises occur.

Need for comprehensive and up-to-date frameworks and planning

2.76 A common theme that emerged from various COVID-19 pandemic lessons learned publications was the inadequacy of existing frameworks for the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic and government response. While there were pre-existing plans and arrangements for emergency preparedness and response in Australia and other countries, the publications noted that some were more focused on responding to defined and time-limited events such as bushfires and floods; some were outdated and confusing, with references to structures, agencies and arrangements that no longer existed; some were not updated to incorporate learnings from previous reviews or other jurisdictions, or as the COVID-19 pandemic progressed; and many did not cover key elements of the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The UK NAO noted, for instance, that that its government ‘lacked a playbook for many aspects of its response’, and observed:

No playbook can cover all the specific circumstances of every potential crisis. Nevertheless, more detailed planning for the key impacts of a pandemic and of other high-impact low-likelihood events can improve government’s ability to respond to future emergencies. It may also bring other benefits such as creating new relationships and improving understanding between organisations.43

2.77 Due to the scale and nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, the COVID-19 pandemic lessons learned publications emphasised the importance of taking a holistic, whole-of-government approach when developing emergency frameworks and plans. In Australia, the Joint Standing Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade, in its inquiry into the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for Australia’s foreign affairs, defence and trade, noted that the COVID-19 pandemic revealed weaknesses in Australia’s capacity to deal with future emergencies and to survive large disruptions to supply chains. It noted that while some analytical work has been undertaken to understand the risk to various individual sectors, there was a need to broaden analysis to the economy as a whole to assess which elements of Australia’s critical national systems are vulnerable to supply-chain disruptions, and establish a ‘national resilience framework’ to help prepare the Australian economy for future crises.

2.78 A common barrier to an effective emergency response noted by almost all phase 3 publications was a lack of clarity in roles and responsibilities as the emergency response unfolded. This was particularly pronounced with respect to the relationship between the Australian Government and state and territory governments. The publications commented that the delineation of roles between the jurisdictions was often unclear, resulting in ‘highly-localised and often highly-differentiated responses’44 and inconsistency when implementing national decisions, which led to confusion and uncertainty for the public.

2.79 In the ANAO’s audit of the Australian Government Crisis Management Framework (AGCMF), the ANAO observed that, as crises become more complex, concurrent, and cut across multiple sectors, the breadth of consequences increases, and more stakeholders are involved. This necessitates a governance structure where roles and responsibilities are clearly articulated. The ANAO also identified a key message for the public sector emphasising the importance of regular tests, exercises and evaluation of preparedness for crises responses in non-crisis settings. Regular evaluation of preparedness, including to identify new and emerging risks and threats, allow for minor course corrections over time, rather than requiring a significant shift without sufficient testing.

2.80 The COVID-19 pandemic lessons learned publications highlight the importance of emergency preparedness frameworks clearly outlining the governance and coordination arrangements to be stood up in a crisis to determine the government’s early response and being regularly reviewed and updated reflect changes in government structure, policies, and processes. The publications also emphasise the need to take a holistic view of the economy and consider the needs, roles and responsibilities of all levels of government, as well as public and private sector enterprises and community organisations.

Learning from the COVID-19 pandemic and other crises

2.81 The second common theme emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic lessons learned publications is the need for governments to properly incorporate learning from the COVID-19 pandemic and other crises to inform future crisis preparations. In particular, the publications emphasised the importance of going beyond the immediate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic to take steps to embed the lessons into broader crises management frameworks, practices, and culture. For instance, the UK Comptroller and Auditor-General stated in his foreword to the UK NAO report on Initial learnings from the government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic that:

The challenges posed by the pandemic have highlighted the importance for government of adopting a systematic approach to preparing for high-impact events, evaluating its performance frequently, and acting quickly on learning points while adhering to required standards of transparency and accountability even in emergencies. This goes beyond meeting legal (or audit) requirements. It involves adhering to the standards that government has set for itself to maintain and strengthen public trust.45

2.82 The publications emphasised different aspects of the lessons learned process. For example, the NZ OAG noted the need for ‘a more formalised and systematic approach to recording and reporting [on the government’s] progress against recommendations from reviews and other work’ to provide transparency and assurance to public that improvements are being made.46 UK NAO and US GAO both commented on the need for their governments to reflect on how the COVID-19 pandemic and its responses may have affected or exacerbated inequalities in society, and address the challenges faced by certain vulnerable subsets of population. Australia’s 2020 Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements observed that there is a need for quality assurance mechanisms to enable ongoing learning, continuous improvement and promote best practice at the Australian Government level, and emphasised the value of independent external bodies in delivering these assurance functions.

2.83 The ANAO’s audit of the AGCMF noted that there are gaps in lessons management at the whole-of-government level. As the lessons management capability matures, implementation of actions to address identified lessons is improving. The audit noted that the increased oversight and additional continuous improvement activities established in the revised AGCMF released in September 2024 will be important to ensure the framework remains appropriate for responding to crises over time as threats and the environment continue to evolve.

Audits of the financial statements of Australian Government entities

2.84 In preparing financial statements, management is required under the Australian Accounting Standard AASB 101 Presentation of Financial Statements (AASB 101), paragraph 25 to make an assessment of an entity’s ability to continue to meet its financial obligations as they are due. When making this assessment, management is required to take into account all available future information for a period of at least 12 months from the end of the reporting period.

2.85 Financial sustainability measures the ability of an entity to manage its financial resources so it can meet present and future spending commitments. This can provide an indication of financial management issues or can point to an increased risk that entities may require additional government funding.

2.86 In 2019–20, eight entities were significantly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic or the Australian bushfires and required either additional funding, letters of support or a restructuring of operations.47 These entities and the effect on the 2019–20 financial statements are outlined in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3: ANAO analysis of entities impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic

|

Entity |

Effect on the entities 2019–20 financial statements |

The entity’s response relating to the impact of the Australian Bushfires and or the COVID-19 pandemic |

|

Airservices Australia |

Decrease in revenue by 25% and an increased long term and short term borrowings of $1.2 billion. |

Letter of intent provided by the minister and additional funding from government. |

|

Civil Aviation Safety Authority |

The aviation fuel excise decreased by 17% from the prior year. Increase of 26% in appropriation funding in 2019–20. |

Letter of intent provided by the minister and additional funding from government. |

|

Royal Australian Navy Central Canteens Board (RANCCB) |

Decrease in revenue of 9%. |

RANCCB restructured its operations, reducing staffing and terminating casual employees. |

|

Bundanon Trust |

Decrease in own-source revenue of 40%. |

Additional funding provided by the government and access to financially liquid investments |

|

Director of National Parks |

Park entry and camping fees reduced by 34%. |

Additional appropriation funding provided by the government and camping fees to recommence in January 2021. |

|

Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority |

24% reduction in revenue. |

Government funding will continue into the new financial year for operations and additional capital works on its HQ Aquarium, with environmental management fees to recommence in January 2021. |

|

Sydney Harbour Federation Trust |

Decrease in own-source revenue of 13%. |

Government approved access to cash reserves. |

|

Voyages Indigenous Tourism Australia Pty Ltd |

Decrease in own-source revenue of 26%. |

Letter of support provided by Indigenous Land and Sea Corporation (parent entity). |

Source: Summary of information presented in Table 2.6 of Auditor-General Report No. 25 2020–21, Audits of the Financial Statements of Australian Government Entities for the Period Ended 30 June 2020.

2.87 Crisis situations can change the environment entities are operating in and may impact revenue sources. It is important for entities to consider early in a crisis any potential financial impacts and the likely need for financial support.

3. Assurance reviews of Advances to the Finance Minister

Chapter coverage

This chapter summarises the limited assurance reviews conducted by the ANAO over the Advances to the Finance Minister (AFM) from April to October 2020.

Summary

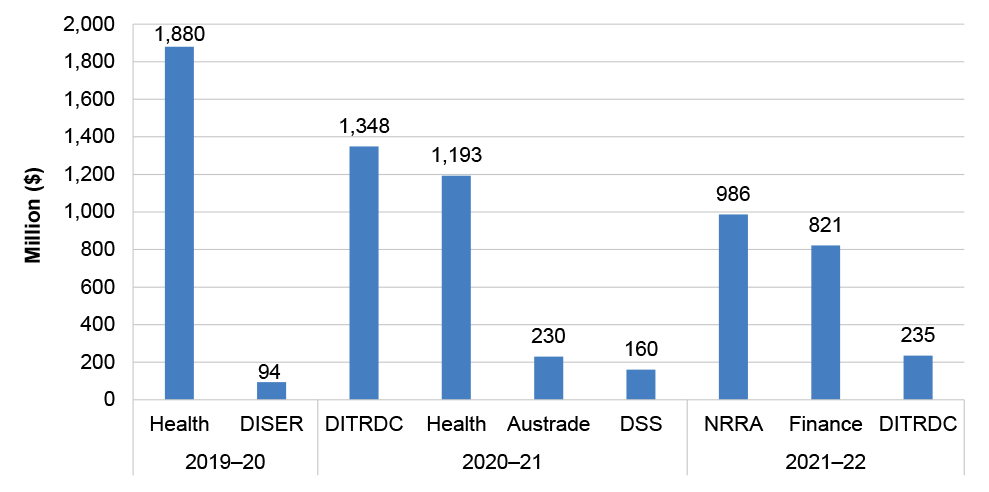

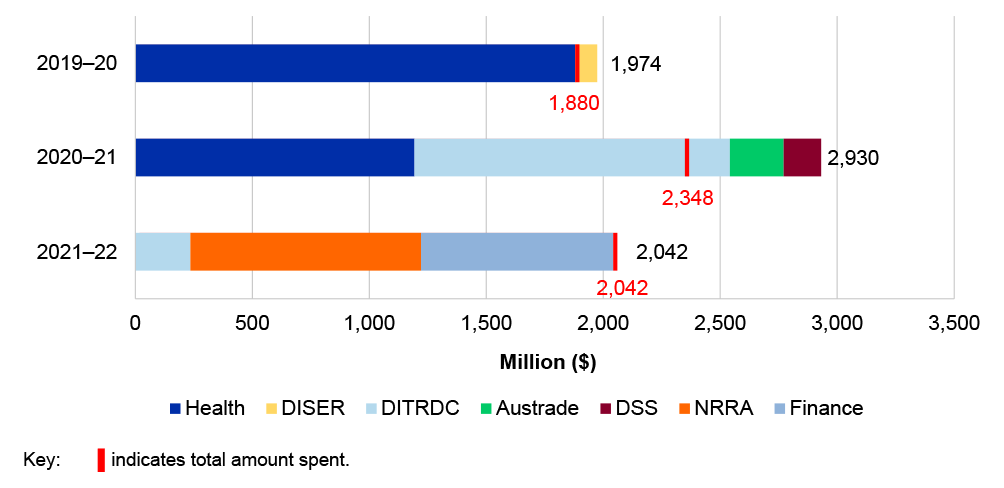

There was a significant increase in available AFM in 2019–20 to 2021–22 compared to previous years, as additional appropriations were passed to support increased government spending in response to COVID-19. Total AFM of $42.975 billion was available to be allocated in 2019–20, $50.384 billion in 2020–21, and $11.807 billion in 2021–22. Of these available AFM amounts, $1.974 billion, $2.930 billion, and $2.042 billion were provided in respective years.

Health received the highest amount of advances over the period ($3.073 billion), followed by DITRDC ($1.583 billion).

The ANAO’s COVID-19 assurance reviews examined a total advance of $1.974 billion issued in 2019–20 and $1.673 billion issued in 2020–21 to 30 October 2020. The Auditor-General issued unmodified conclusions for all seven assurance reviews.

3.1 The Advance to the Finance Minister (AFM) is a provision in the annual Appropriation Acts48 which enables the Minister for Finance to provide additional urgently needed appropriation to agencies for expenditure in the current year. The Finance Minister may only agree to provide additional appropriation from the advance if satisfied that there is an urgent need for expenditure that is either not provided for or has been insufficiently provided for in the existing appropriations of the entity. The Finance Minister provides the additional appropriation by means of a determination.

3.2 To ensure transparency, AFM determinations are:

- registered on the Federal Register of Legislation (FRL);

- tabled in Parliament at the next available opportunity; and

- listed on the Department of Finance (Finance) website with a link provided to it on the FRL.

3.3 At the end of the financial year, Finance prepares an AFM annual report, which is subject to review by the ANAO, detailing all AFMs that have been issued in that financial year. The AFM annual report is tabled in the Parliament and is made available on the Department of Finance’s website.49

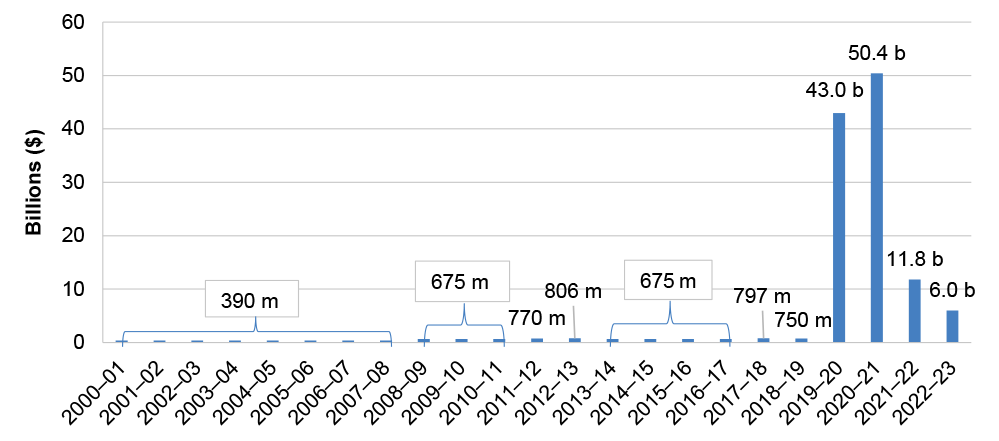

3.4 The AFMs available for allocation increase from $750 million in 2018–19 to $43 billion in 2019–20, as additional advances were made available to support Australian Government activities during the COVID-19 pandemic (see Figure 3.1). The ANAO undertook monthly assurance reviews of the AFM from April to October 2020, which were tabled in Parliament.50 From November 2020, the ANAO determined that the heightened risks resulting from increased appropriation and spending of AFM had reduced, and resumed its annual reviews of AFMs.

Available Advances to the Finance Minister

3.5 The amounts that can be appropriated under the AFM provisions are limited to amounts identified in the Appropriation Acts. Figure 3.1 shows the amount of AFM available for appropriation over the years from 2000–01 to 2022–23.

Figure 3.1: Available AFM, 2000–01 to 2022–23

Source: ANAO analysis.

3.6 As the figure shows, there was a significant increase in available AFM from 2019–20, compared to previous years. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, on 24 March 2020, Appropriation (Coronavirus Economic Response Package) Act (No. 1) 2019-2020 and Appropriation (Coronavirus Economic Response Package) Act (No. 2) 2019-2020 were enacted, making available additional AFM of $0.8 billion and $1.2 billion respectively for 2019–20. At the same time, Supply Act (No. 1) 2020-21 and Supply Act (No. 2) 2020-21 were passed by Parliament for 2020–21, which included AFM of $16 billion and $24 billion respectively. Subsequently, on 9 April 2020, Appropriation Act (No. 5) 2019-2020 and Appropriation Act (No. 6) 2019-2020 were passed with the effect of making the AFM in the 2020–21 Supply Acts available to be advanced in 2019–20.

3.7 Table 3.1 summarises the legislative sources of AFM available from 2019–20 to 2022–23.

Table 3.1: Advances available in 2019–20 to 2021–22

|

Financial year |

Legislation |

AFM amount ($) |

|

2019–20

|

Appropriation Act (No. 1) 2019-2020 |

295,000,000 |

|

Appropriation Act (No. 2) 2019-2020 |

380,000,000 |

|

|

Appropriation (Coronavirus Economic Response Package) Act (No. 1) 2019-2020 |

800,000,000 |

|

|

Appropriation (Coronavirus Economic Response Package) Act (No. 2) 2019-2020 |

1,200,000,000 |

|

|

Appropriation Act (No. 3) 2019-2020 |

– |

|

|

Appropriation Act (No. 4) 2019-2020 |

300,000,000a |

|

|

Appropriation Act (No. 5) 2019-2020 |

16,000,000,000 |

|

|

Appropriation Act (No. 6) 2019-2020 |

24,000,000,000 |

|

|

Total AFM available 2019–20 |

42,975,000,000 |

|

|

2020–21

|

Supply Act (No. 1) 2020-2021 |

16,000,000,000 |

|

Supply Act (No. 2) 2020-2021 |

23,908,500,000b |

|

|

Total AFM available (from 1 July 2020 to 3 December 2020)c |

39,908,500,000 |

|

|

Appropriation Act (No. 1) 2020-2021 |

4,000,000,000 |

|

|

Appropriation Act (No. 2) 2020-2021 |

6,000,000,000 |

|

|

Appropriation Act (No. 3) 2020-2021 |

475,816,000d |

|

|

Appropriation Act (No. 4) 2020-2021 |

– |

|

|

Total AFM available (from 4 December 2020 to 30 June 2021)c |

10,475,816,000 |

|

|

Total AFM available 2020–21 |

50,384,316,000 |

|

|

2021–22

|

Appropriation Act (No. 1) 2021-2022 |

2,000,000,000 |

|

Appropriation Act (No. 2) 2021-2022 |

3,000,000,000 |

|

|

Appropriation (Coronavirus Response) Act (No. 1) 2021-2022 |

2,000,000,000 |

|

|

Appropriation (Coronavirus Response) Act (No. 2) 2021-2022 |