Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

2023–24 Performance Audit Outcomes

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Summary

1. The purpose of the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) is to support accountability and transparency in the Australian Government sector through independent reporting to the Parliament, and thereby contribute to improved public sector performance. The ANAO delivers its purpose under the Auditor-General’s mandate in accordance with the Auditor-General Act 1997, the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 and the Public Service Act 1999.

2. The executive arm of government is accountable to the Parliament for its use of public resources and the administration of legislation passed by the Parliament. The Auditor-General provides independent assurance as to whether the executive is operating and accounting for its performance in accordance with the Parliament’s intent. The ANAO’s performance audit program is one of the main assurance functions of the Auditor-General.

3. The Auditor-General Act 1997 (the Act) authorises the Auditor-General to conduct financial statements audits, performance audits, assurance reviews or audits of the performance statements and performance measures of Commonwealth entities, Commonwealth companies and their subsidiaries. The Act also authorises providing other audit services as required by other legislation or allowed under section 20 of the Act, and reporting directly to the Parliament on any matter or to a minister on any important matter that comes to the attention of the Auditor-General. Under sections 32 and 33 of the Act, the Auditor-General has extensive information-gathering and access powers to support auditing processes. The ANAO’s preference is to obtain information through cooperation with audited entities.

4. The ANAO’s primary relationship is with the Australian Parliament, particularly the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA). The ANAO consults with and has regard to the priorities of the Parliament as determined by the JCPAA when developing its Annual Audit Work Program as required under the Act.

5. Audit quality is fundamental to the reliance placed on Auditor-General reports by the Parliament, and the ANAO focuses on delivering quality audits through its Quality Management Framework and Plan. Key elements of the framework include external and internal reviews that provide assurance to the Auditor-General that the audits had been conducted in accordance with the requirements of the Act, ANAO Auditing Standards and associated methodologies.

6. In 2023–24, the Auditor-General presented 45 performance audit reports to the Parliament. In 2024–25, the target for performance audits increases to 48, consistent with the Parliament’s expectations. Resourcing the ANAO to complete the performance audit program brings challenges. There is no ‘tertiary ready’ workforce to recruit directly into the ANAO, requiring an ongoing training and coaching program to bring capability and quality. Increases in costs in mandatory financial statements auditing can reduce the resources available to undertake performance auditing.

Analysis of performance audits from 2019–20 to 2023–24

7. In October 2020, the 15th Auditor-General, Mr Grant Hehir, released a mid-term report, which provided statistics on the coverage of the performance audit program from 2015–16 to 2019–20, as well as audit outcomes by metric across the sector.1 This information report has been prepared to provide a similar analysis of performance audits from 2019–20 to 2023–24, with a particular focus on outcomes from 2023–24.

8. Performance audits conducted by the ANAO in 2023–24 identified deficiencies in public sector governance and procurement activities. Grants administration audits in 2023–24 have seen improvements when compared to the average from 2019–20 to 2023–24. The procurement and grants frameworks are established under finance law and represent a minimum expectation of compliance and administration. Getting the ‘basics right’ such as adhering to the law, whole-of-government policy and frameworks, and record keeping practices enables entities to achieve outcomes, minimise risk and make decisions in the public interest. A challenge for leaders is to ensure they consistently demonstrate the expected behaviours, professionalism and standards that promote a culture of compliance with both the letter and intent of the law, along with an expectation that results are achieved.

9. Poor record keeping practices continued to be observed through 2023–24 with every performance audit report commenting on record keeping. All public sector staff have a role to play in record keeping. The National Archives of Australia states that:

Public trust in the functions of agencies depends on accountability—our ability to show that decisions have been made on the basis of reason and evidence; Australian Government resources are being used appropriately; and that consideration of the public interest is foremost in our work.2

10. An analysis of reports from 2019–20 to 2023–243 identified the following:

- the National Disability Insurance Agency had the highest percentage of negative conclusions and the highest average number of recommendations and the Social Services and Treasury portfolios had the highest percentages of unqualified conclusions;

- audits with a negative conclusion represented 63 per cent of policy development activity audits, 60 per cent of grants administration activity audits and 53 per cent of procurement activity audits. Audits with a positive conclusion represented 66 per cent of asset management and sustainment activity audits; and

- five of the six efficiency audits had negative conclusions.

11. Entities fully agreed with more than 90 per cent of recommendations each year from 2019–20 to 2023–24, with 94 per cent of recommendations agreed to in 2023–24. Between 2017–18 and 2021–22, an average of 80 per cent of recommendations were self-reported by entities to have been implemented.4

12. From 2021–22, performance audit reports included an appendix to capture improvements made by entities observed during the course of an audit. In 2023–24, 40 of the 45 performance audits (89 per cent) tabled in the Parliament identified improvements observed during the auditing process.

Themes from 2023–24 performance audits

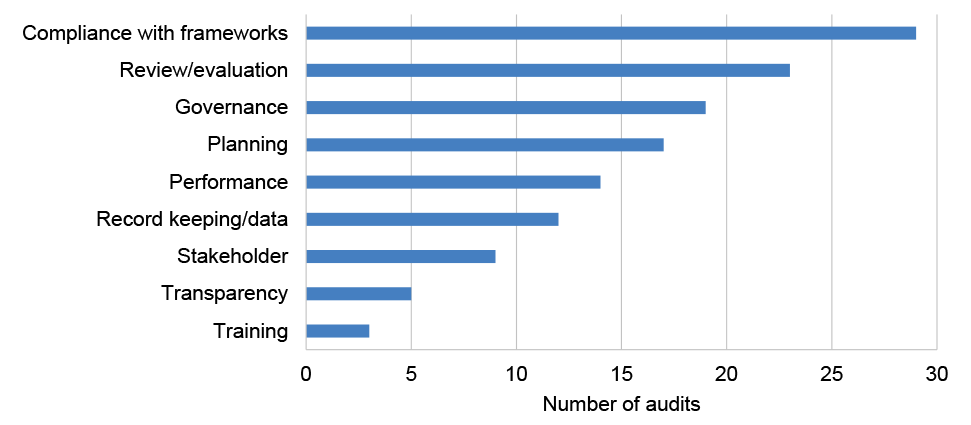

13. The ANAO’s performance audit activities involve independent, objective and evidenced-based assessment of all or part of an entity’s operations and administrative support systems. Through this assessment, the ANAO identifies key messages that arise from both good practice and deficiencies. Themes arising from performance audit reports tabled in 2023–24 are summarised below.

Assurance of the operation of government frameworks

14. There are a number of mandatory whole-of-government frameworks with which the public sector needs to comply. Policy owners for these frameworks establish their rules of operation and then largely rely on Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) accountable authorities and Australian Public Service agency heads to ensure compliance with the frameworks. The ANAO has for a number of years suggested that the policy owners of frameworks in areas such as resource management, procurement, grants administration, cyber security, record keeping, freedom of information, and ethical conduct should take a stronger or more active regulatory posture. In 2023–24, compliance with frameworks continued to be arising from performance audits.

Integrity, probity and ethics

15. In 2023–24, the ANAO tabled six performance audit reports in the Parliament that focused on compliance with selected public service legislative and policy requirements for corporate credit cards and gifts, benefits and hospitality. Findings from these performance audits can provide indicators of areas of risk to integrity, probity and ethics, including where action may be necessary to avert systemic issues. Compliance with credit card requirements, particularly by senior executives, can be indicative of the tone set for the entity. Likewise, establishing a guiding principle for officials to generally avoid the acceptance of gifts, benefits and hospitality and creating transparency of the acceptance of gifts, benefits and hospitality can help to promote a culture of integrity.

Planning and implementation

16. Over 2019–20 to 2023–24, 63 per cent of performance audits classified as policy development activity audits were found to be either ‘not effective’ or ‘partly effective’. In 2023–24, the themes of governance and planning were included in key messages set out in audit reports. Performance audits have identified that early and proactive planning is more likely to result in good implementation and governance.

Evaluation

17. In December 2021, the Commonwealth Evaluation Policy was released.5 The policy applies to all Australian Government entities subject to the PGPA Act. The need to plan for evaluation at the commencement of a program, with a particular focus on identifying what data will be needed for evaluation purposes, was a recurring key message from performance audits in 2023–24.

Procurement and contract management

18. ANAO performance audits assess procurement in Australian Government entities against the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (or their equivalent) and the PGPA Act. There were 36 performance audits of procurement and contract management conducted over 2019–20 to 2023–24, with 53 per cent found to be either ‘not effective’ or ‘partly effective’. In 2023–24, audits on procurement activities had some of the highest number of recommendations with improvements required in planning and record keeping practices as well as compliance with the rules framework.

Cyber security

19. Australian Government entities are expected to be ‘cyber exemplars’ as they process and store some of Australia’s most sensitive data to support the delivery of essential public services. Low levels of cyber resilience make entities more susceptible to cyber attack and reduce business continuity and recovery prospects following a cyber security incident. Preparedness to respond to and recover from a cyber attack is a key part of cyber resilience particularly in the public sector which relies on IT to deliver services. Auditor-General Report No. 38 2023–24, Management of Cyber Security Incidents and a previous audit report6 detailed potential deficiencies of which entities need to be aware when implementing cyber security requirements.

Observations on record keeping practices

20. In 2023–24, the ANAO made negative findings on record keeping practices in all 45 performance audit reports tabled in the Parliament. Getting the ‘basics right’ in terms of record keeping processes continues to be a challenge for entities. Good record keeping is required by law and supports effective corporate governance, accountability and performance.

Further guidance material

21. The ANAO has published audit ‘Insights’ products7 on risk management, procurement and contract management, grants administration, cyber security and other areas of note to assist entities improve their performance. In September 2024, the ANAO published its inaugural quarterly Audit Matters newsletter to inform external audiences of updates on the ANAO’s work and provide insights on what we are seeing in the Australian Government sector.8

1. Introduction

Chapter coverage

This chapter explains the importance of the performance audit program in providing assurance to the Parliament and to promote accountability, transparency and improvement in public administration. It provides the context for performance audits conducted by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO), selected from the Annual Audit Work Program (AAWP).

Summary

The role of the Auditor-General is to provide independent reporting and assurance to the Australian Parliament on whether the executive government is operating in accordance with the Parliament’s intent, and within the executive’s own policy and rule framework, to achieve desired objectives. The ANAO’s performance audit program is one of the assurance functions of the Auditor-General.

The ANAO’s primary relationship is with the Parliament, particularly the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA). The ANAO consults with and considers the priorities of the Parliament when developing its AAWP. The Parliament has provided the Auditor-General with strong information-gathering powers to support the pursuit of evidence in the audit process and ensure that reports are reliable.

Audit quality is fundamental to the reliance placed on Auditor-General reports by the Parliament, and the ANAO focuses on delivering quality audits through its Quality Management Framework and Plan. Key elements of the framework include external and internal reviews that provide assurance to the Auditor-General that the audits had been conducted in accordance with the requirements of the Auditor-General Act 1997, ANAO Auditing Standards and associated methodologies.

1.1 All performance audit reports are tabled in the Parliament and are considered parliamentary products. Performance audit reports provide the Parliament with valuable information about an entity’s performance, commensurate with the audit objective, and can be used to scrutinise executive government operations and hold the executive to account. Performance audits have been the subject of a range of inquiries by the JCPAA, some of which have resulted in legislative changes by Parliament, and changes to the Commonwealth Procurement Rules9 and the Commonwealth Grants Framework. 10

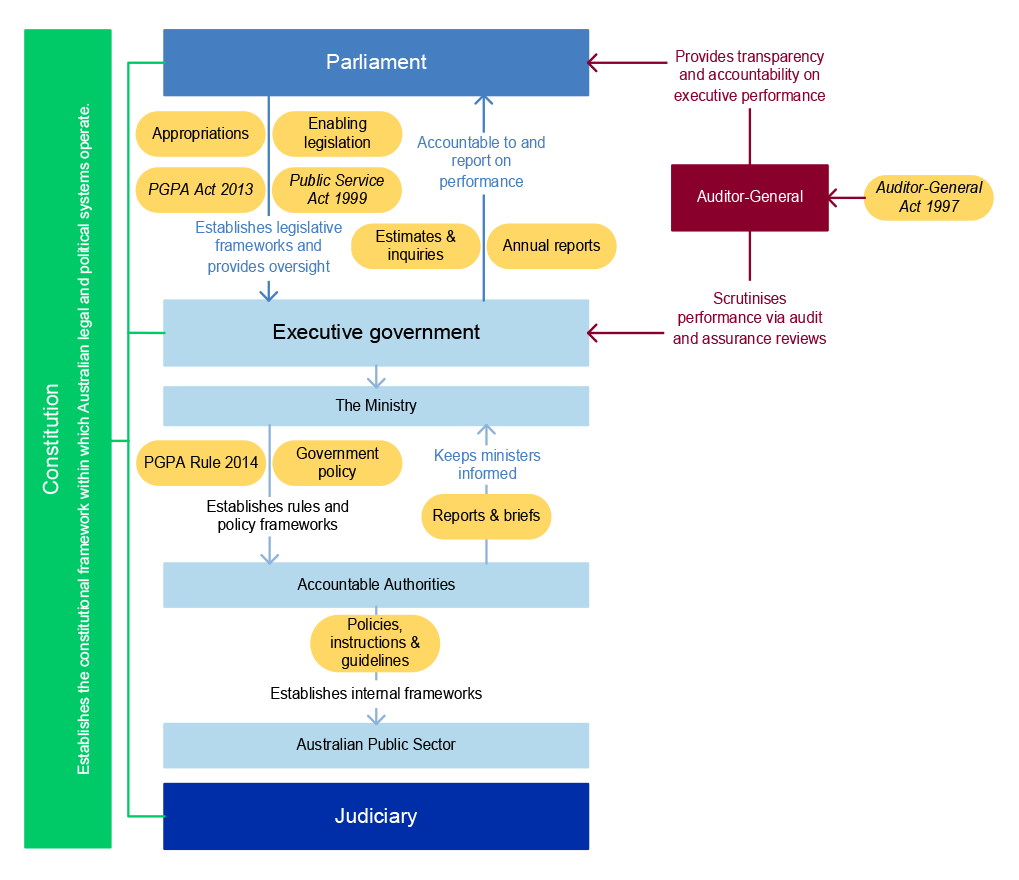

1.2 The Australian public sector operates under an accountability model that consists of interconnected legal and regulatory frameworks, creating vertical and horizontal accountability relationships between the electorate, the Parliament, the government and public officials (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1: Australian public sector accountability framework

Source: ANAO.

1.3 The executive arm of government is accountable to the Parliament for its performance and operates under legislative frameworks set by the Parliament, such as entities’ enabling legislation and importantly, the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), which governs the proper use and management of public resources. Consistent with relevant legislation, the Australian Government develops rules and sets out policy frameworks to be implemented by departments and other agencies. Accountable authorities of each Australian Government entity set in place internal frameworks to instruct officials on certain matters.

1.4 The Australian public sector is expected to operate within these frameworks when carrying out its functions. The maintenance of clear lines of accountability within the public sector is essential to providing confidence to the Parliament and the Australian public that the public sector is delivering advice and services in a transparent and accountable way.

Role of the Auditor-General

1.5 The office of the Auditor-General was the first statutory integrity agency established by the Australian Parliament, following the passage of the Audit Act 1901. The functions and role of the Auditor-General are well established in the accountability framework of the Australian public sector. The role of the Auditor-General is to provide independent reporting and assurance to the Parliament on whether the executive is operating in accordance with the Parliament’s intent, and within the executive’s own policy and rule framework, to achieve desired objectives. The ANAO’s performance audit program, to which this information report relates, is one of the main assurance functions of the Auditor-General.

1.6 Performance auditing has been a key part of the ANAO audit program since its introduction in the late 1970s, following a recommendation from the Royal Commission on Australian Government Administration (Coombs Inquiry) in 1976 that the quality of departmental managers’ performance be subject to review by the Auditor-General.11 The first performance audit (then known as efficiency audit) was tabled in the Parliament in 1980. By the 1990s, performance audit was embedded as an established practice and recognised by the Parliament as an important function of the ANAO.12

1.7 Performance audit reports are independent, evidence-based products that are conducted under auditing standards and seek to report to the Parliament on the Commonwealth entities’ proper use of public resources, including whether they are efficient, effective, economical and ethical. Performance audit reports provide the Parliament with information it can use to scrutinise executive government operations and hold the executive to account.

1.8 To ensure the independence of the Auditor-General in delivering functions, the Auditor-General Act 1997 (the Act) establishes the Auditor-General as an independent officer of the Parliament and provides that the Auditor-General has complete discretion in the performance or exercise of functions or powers. In particular, the Auditor-General is not subject to direction from anyone in relation to:

- whether or not a particular audit is to be conducted;

- the way in which a particular audit is to be conducted; or

- the priority to be given to any particular matter.

1.9 Along with performance audits of entities, Commonwealth companies and their subsidiaries, the Act authorises the Auditor-General to conduct a performance audit of a Commonwealth partner. Audits of Commonwealth partners that are part of, or controlled by, state or territory governments, must be requested by the responsible minister or the JCPAA. Audits of Commonwealth Government Business Enterprises must be requested by the JCPAA. The Act enables the Auditor-General to propose that the JCPAA make such a request.

1.10 The Act imposes strict obligations on the Auditor-General and the ANAO to protect the confidentiality of all information obtained in the course of performing an Auditor-General function (see paragraphs 1.22 and 1.23). The Auditor-General is exempt from Freedom of Information laws.

Selecting topics for audit

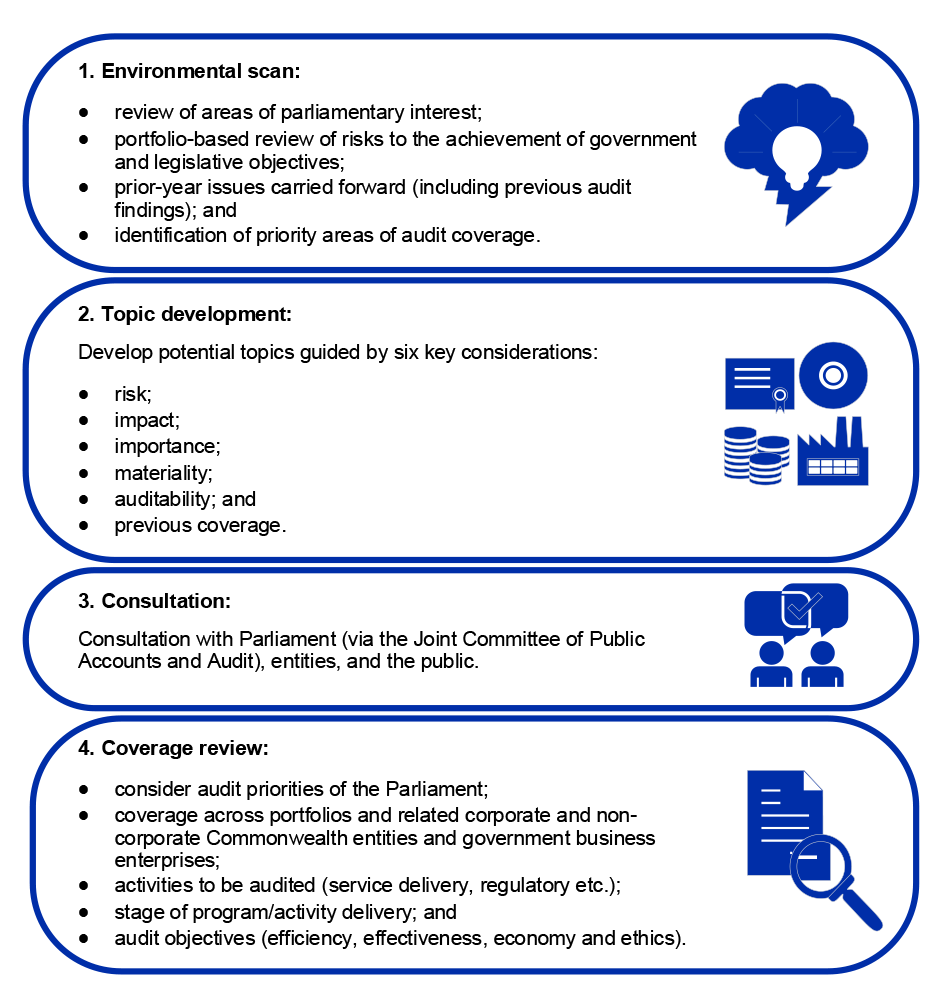

1.11 In July each year, the ANAO publishes an Annual Audit Work Program (AAWP) outlining the planned audit coverage for the Australian Government sector for the financial year. In 2023–24, 95 potential performance audit topics were included in the AAWP and 45 audits were tabled in the Parliament, meeting the ANAO’s performance measure for the year. The AAWP enables early engagement with entities and signals to entities that certain programs may be the subject of an ANAO audit.

1.12 Figure 1.2 outlines the AAWP development process, which is guided by the following objectives:

- having regard to the audit priorities of the Parliament as determined by the JCPAA along with any reports of the JCPAA13 (see Appendix 1);

- providing a balanced program of activity that is informed by risk, and promotes accountability, transparency and improvements in public administration14;

- following up on past Auditor-General and selected parliamentary recommendations to identify trends for improvement, or declines in performance across government; and

- applying all of the Auditor-General’s mandate.

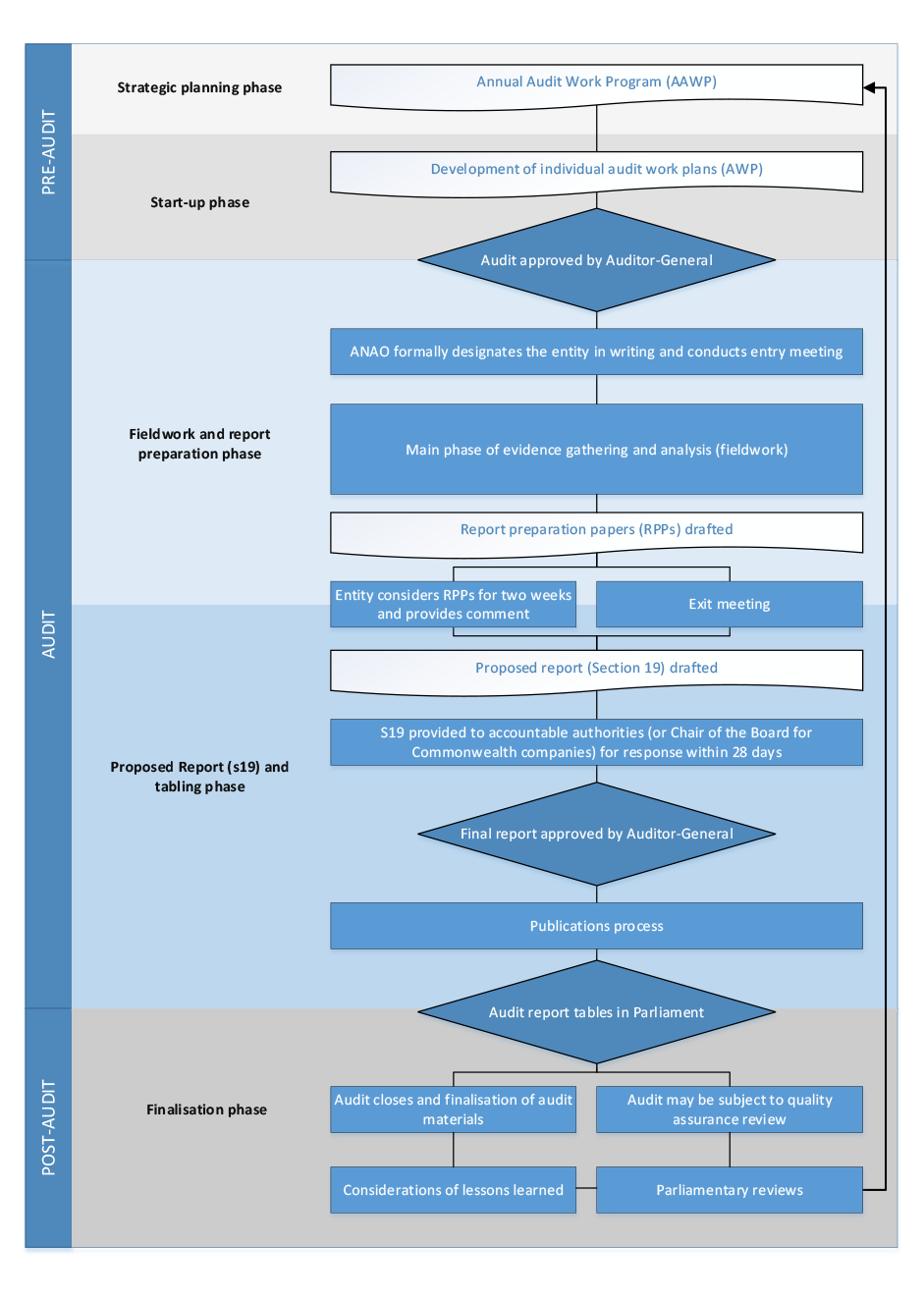

Figure 1.2: Annual Audit Work Program development process

Source: Australian National Audit Office, Annual Audit Work Program 2024–25: Overview, ANAO, Canberra, 2024, available from https://www.anao.gov.au/work-program/overview [accessed 14 October 2024].

1.13 Through an environmental scan, the ANAO determines areas of audit focus based on:

- portfolio-specific risks identified in prior-year audits of all types and other reviews;

- emerging sector-wide risks from new investments;

- announcements by government of new programs; and

- public sector operating environment changes.

- Following the development of potential performance audit topics, the Parliament (through the JCPAA), accountable authorities of entities, the Commonwealth Ombudsman, Inspector-General of Taxation and the Commissioner of the National Anti-Corruption Commission are consulted on the draft AAWP and invited to provide comments and feedback. The draft AAWP is released for public consultation through the ANAO’s website.

1.14 To assess the appropriate audit coverage of the public sector, the ANAO considers four key categories in the development of the AAWP and before the commencement of a performance audit:

1.15 From time to time, the Auditor-General receives recommendations from parliamentary committees, and requests from ministers and secretaries of departments, as well as individual members of Parliament, to conduct audits into particular areas of public administration. Where the Auditor-General determines that examination is warranted as a result of an audit request, a response can be provided through a range of mechanisms, including by initiating a performance audit, undertaking work in the course of a financial statements audit, undertaking an assurance review, and through correspondence or inclusion in future audit work programs.

1.16 In 2023–24, the Auditor-General received eight requests for audit from members of Parliament. This is equal to the total number of requests for audit received in 2022–23.

1.17 Throughout the year, the Auditor-General determines the performance audits that will commence, based on consideration of the Auditor-General’s functions and jurisdiction, audit priorities of the Parliament, an assessment of strategic risk, auditability of potential topics, achieving sufficient breadth and depth across the government sector, and the availability of skilled staff to undertake audits. The Auditor-General further considers any recent developments in the public sector, areas of public interest, opportunities to demonstrate good practice in public administration and accountability, and requests for audit.

1.18 Appendix 2 provides an overview of the performance audit process from developing the AAWP through to tabling of the performance audit and post-audit inquiries/hearings by the Parliament.

Accessing information

1.19 The Parliament has provided the Auditor-General with strong information-gathering powers to support the pursuit of evidence in the audit process and ensure that reports are reliable. Auditing standards set by the Auditor-General (see paragraph 1.29 and 1.30) require the auditor to obtain sufficient and appropriate audit evidence to reduce the risk of forming an incorrect conclusion to an acceptably low level. If an auditor is prevented from accessing the information required to form an audit conclusion, the auditor is required to consider the implications for the audit conclusion.

1.20 The information-gathering and access provisions are specified under sections 32 and 33 of the Act (see Box 1). Failure to comply with these requirements can attract penalties.

|

Box 1: Auditor-General Act 1997 information gathering powers |

|

Section 32 Section 32 provides that the Auditor-General can, by written notice, direct a persona to: provide any information that the Auditor-General requires; attend and give evidence (including under oath or affirmation); or produce any documents in the custody or under the control of that person. The section 32 powers apply to any information and documents including, but not limited to, Cabinet documents, advice and decisions, commercially sensitive information including contracts, advice attracting legal professional privilege, classified documents and information. Section 33 Section 33 provides that the Auditor-General, or an authorised official: may at all reasonable times enter and remain on any premises that are occupied by an Australian Government entity, company or partner; is entitled to full and free access at all reasonable times to any documents or other property; and may examine and make copies of any document. ANAO authorised officials have authority from the Auditor-General for the purpose of section 33 of the Act. This authority can be produced on request. |

Note a: This includes ministers, communities and businesses.

1.21 The ANAO’s information-gathering and access powers override secrecy or prohibition of disclosure provisions in any other law, except to the extent that the other law expressly excludes the operation of sections 32 and 33 of the Act. The operation of sections 32 and 33 of the Act is not limited by any rule of law relating to legal professional privilege or any other privilege, or the public interest, in relation to the disclosure of information or the production of documents. The Auditor-General’s section 32 and 33 powers may also be exercised if entities or persons do not co-operate with the ANAO.

1.22 The ANAO’s information-gathering powers are balanced by strict confidentiality obligations applying to ANAO officials, and provisions preventing to the disclosure of information that would be contrary to public interest. Subsection 36(1) of the Act provides that if a person has obtained information in the course of performing an Auditor-General function, the person must not disclose the information. They may only do so for the purpose of performing their function — such as informing relevant ANAO colleagues and communicating with relevant entity officials about the audit.

1.23 Section 37 of the Act provides that the Auditor-General must not include particular information in a public report if:

- the Auditor-General is of the opinion that disclosure of the information would be contrary to the public interest; or

- the Attorney-General has issued a certificate to the Auditor-General stating that, in the opinion of the Attorney-General, disclosure of the information would be contrary to the public interest.

1.24 A certificate by the Attorney-General under section 37 of the Act has been issued once on 28 June 2018 in relation to information in Auditor-General Report No. 6 2018–19, Army’s Protected Mobility Vehicle — Light. No certificates have been issued by the Attorney-General since.

1.25 It is rare for the ANAO to issue a section 32 notice, preferring a cooperative approach with entities. In 2023–24, the ANAO issued an increased number of section 32 notices under the Act for performance audits with 11 section 32 notices issued to five entities (see Appendix 3). The ANAO has observed two factors driving this increase — comfort for agencies who operate under secrecy, privacy or other legislative provisions, and to fill evidence gaps due to poor record keeping. The latter case has led to an increased need for the ANAO to access bulk entity datasets (for example, email records) and use e-discovery tools in audits. Notices may be required when an entities provision of requested documents is not timely and key records such as emails are not stored in entity record keeping systems. Entities have advised the ANAO that a section 32 notice is required as information subject to privacy and secrecy provisions may be contained in emails.

1.26 Beyond these examples, requests for documents containing sensitive information are at times initially resisted, including access to: Cabinet-in-Confidence documents and information; legal advice that is relevant to the subject matter of the audit18; and contracts and commercially sensitive information despite the extent of the Auditor-General’s information-gathering powers.

1.27 The ANAO has observed an increase in instances where entities need to be reminded or advised of the ANAO’s section 33 powers, to provide the necessary audit evidence where there are no other perceived legislative factors or impediments. In 2023–24, section 33 of the Act was used to access information seven times from five entities for performance audits (see Appendix 3). The increased use of powers under the Act to gather evidence for auditing purposes has contributed to a revised approach to the ANAO’s engagement with the public sector. More effort is being applied to educate entities through the audit process and through products and engagement designed to grow knowledge of the ANAO’s powers and processes within the sector.

Delivering quality audits

1.28 Audit quality is fundamental to the reliance placed on Auditor-General reports by the Parliament. The ANAO defines audit quality as the provision of timely, accurate and relevant audits that are valued by the Parliament and performed independently in accordance with the requirements of the Act, ANAO Auditing Standards and associated methodologies.

1.29 The ANAO’s audit work is governed by the ANAO Auditing Standards, established by the Auditor-General in accordance with section 24 of the Act. The ANAO Auditing Standards incorporate the standards issued by Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards Board and are consistent with the key requirements of the International Standards of Supreme Audit Institutions (ISSAI). The ANAO Auditing Standards adopt ASAE 3500 Performance Engagements, except in relation to reporting requirements, internal controls and non-compliance with laws and regulations. The reporting requirements of ASAE 3500 are replaced with those contained in the International Organisation of Supreme Audit Institutions Standard ISSAI 3000 Performance Audit Standard (ISSAI 3000). The use of ISSAI 3000 reporting requirements allows greater flexibility for the inclusion of positive aspects of an entity’s performance in the audit conclusion.

1.30 The ANAO Auditing Standards incorporate Auditing Standard ASQM 1: Quality Control for Firms that Perform Audits and Reviews of Financial Reports and Other Financial Information, Other Assurance Engagements and Related Services Engagements. The ANAO is required to establish and maintain a system of quality control designed to provide it with reasonable assurance that it complies with the ANAO standards and applicable legal and regulatory requirements, and that reports issued by the ANAO are appropriate in the circumstances. The ANAO’s Quality Management Framework and Plan is the system of control that has been adopted.19

External audits and reviews

1.31 Section 41 of the Act establishes the position of the Independent Auditor. Under subsection 45(1) of the Act, the Independent Auditor may at any time conduct a performance audit of the ANAO. The Independent Auditor is appointed by the Governor-General on the recommendation of the Prime Minister with the approval of the JCPAA. The Act requires a vacancy in the position of Independent Auditor to be filled as soon as practicable, with a term of at least three but not more than five years.

1.32 The Governor-General appointed Mr Shane Bellchambers as the ANAO’s Independent Auditor, commencing 1 April 2024 for a period of four years. The Independent Auditor conducts audits of the ANAO’s financial and performance statements and can undertake performance audits within the ANAO. The most recent Independent Auditor performance audit report — Performance Audit of Attraction, Development, and Retention of Capability — was tabled in the Parliament on 15 August 2022.20

1.33 The ANAO and the Office of the Auditor-General New Zealand (OAG NZ) have a long-standing arrangement to conduct annual reciprocal performance audit peer-reviews, on a rotating basis. The OAG NZ has conducted four peer review reports since 2016. This arrangement seeks to strengthen performance auditing, through the provision of constructive feedback and sharing of better practices. The peer review methodology includes examining two published audit reports against agreed criteria, drawing on information from related planning documents, audit working papers and discussion with ANAO staff.21

Entity feedback on performance audit work

1.34 In 2023–24, the ANAO engaged a research firm, ORIMA Research, to conduct an independent survey to obtain audit entity feedback on the impact of ANAO performance audits. The survey asks entities to provide an assessment of the value of ANAO services on improving entity performance and provide a score in index points. The results of the survey are used as a reporting mechanism for one of the ANAO’s performance measures in the annual performance statements.22

1.35 The ANAO sets a target for 70 per cent positive feedback from surveyed entities on the impact of audits, based on the percentage of respondents agreeing or strongly agreeing to the following four statements.

- The audit made a valuable contribution by providing our organisation with a sense of assurance regarding the administration of the audited activity.

- The audit will help us improve the performance of the audited activity.

- The entity benefits from good practice lessons, and related issues, raised in other ANAO performance audit reports.

- I value the independent opinion expressed by the ANAO.

1.36 For 2023–24, the performance audit survey had a response rate of 59 per cent, which is nine per cent lower than the response rate from the prior year. The survey achieved a result of 89 per cent positive feedback from entities on the impact of audits, representing an eight per cent increase from the prior year.

1.37 The performance audits survey also asked entities to rate the overall value of ANAO’s performance audit services. Overall, 82 per cent of survey respondents agreed that they value performance audit services, an increase of seven per cent from the prior year.

Internal reviews and developments in audit methodology

1.38 A key element of the ANAO Quality Management Framework is the monitoring of compliance with policies and procedures through internal quality assurance reviews of the ANAO’s audits and other assurance engagements. The monitoring program is designed to provide the Auditor-General with assurance that engagements comply with the ANAO Auditing Standards, relevant regulatory and legal requirements, and ANAO policies, and that reports issued are appropriate in the circumstances.

1.39 The ANAO selects audits and other engagements for quality assurance review in accordance with the requirements of the ANAO Audit Manual to provide coverage of all responsible Engagement Executives23 at least once every three years. Results of the quality assurance reviews are published in the ANAO’s annual Audit Quality Report, which is available on the ANAO website.24

1.40 The ANAO regularly reviews and updates its methodology to reflect changes in the ANAO Auditing Standards, industry better practice, and new and emerging products, and to address findings from the ANAO’s quality assurance program.

Presenting performance audits for tabling in the Parliament

1.41 Under section 19 of the Act, the ANAO provides a copy of the proposed performance audit report, including recommendations to the accountable authority of audited entities, before the finalisation of the report. The proposed report is covered by the confidentiality obligation in subsection 36(3) of the Act. To avoid penalty, all recipients of information in the report must not disclose the information except with the consent of the Auditor-General in accordance with subsection 36(4) of the Act. The Auditor-General consents to the provision of proposed performance audit reports by accountable authorities to relevant officials and their audit committees to assist in preparing a response or monitoring entity risks.

1.42 The Auditor-General may give the proposed report or an extract from it to any person that in the Auditor-General’s opinion has a special interest in the proposed report or extract. Recipients of a proposed report or extract have 28 days to provide written comments to the Auditor-General for consideration prior to a final report being prepared.

1.43 Accountable authority responses to the proposed report (and those of any other recipients) and responses to each recommendation are included in the final report, which is tabled in the Parliament. This enables the Parliament to see the accountable authorities’ views on the findings and conclusion of the audit, and whether or not recommendations were agreed. The Auditor-General may include commentary on entity responses where additional context or information is deemed beneficial or necessary for clarity. In 2023–24, additional comments were made in eight of the 45 performance audit reports tabled in the Parliament (see Appendix 4).

1.44 Subsection 17(4) of the Act provides that, as soon as practicable after completing a performance audit, the Auditor-General must cause a copy of the report to be tabled in each House of the Parliament. Following tabling, reports are published on the ANAO website.

1.45 The responsible minister and entity’s accountable authority are notified of the tabling date and receive copies of the report in accordance with subsections 17(4) and 18(2) of the Act. The ANAO also provides copies of the report to the Prime Minister and the Secretary of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet under subsections 17(5) and 18(3). Cross entity reports are given to the Minister for Finance under subsection 18(2) of the Act.

Parliament use of performance audits

1.46 Performance audits conducted by the ANAO contain audit conclusions25 and detail specific recommendations made to Australian Government entities to improve aspects of public administration and performance. Audit recommendations form part of these conclusions and entities typically monitor these through their internal governance arrangements and audit committees.26 This is further supported through an ongoing program of audits on selected entities to examine the effectiveness of the implementation of agreed parliamentary committee and Auditor-General recommendations.

1.47 Performance audits tabled in the Parliament can assist the Parliament in holding the executive government to account. The ANAO’s primary relationship is with the Australian Parliament, particularly the JCPAA. In 2023–24, the JCPAA presented four reports to the Parliament following inquiries into Auditor-General audit reports. Two of the JCPAA reports followed inquiries into ANAO performance audit reports covering procurement, probity and ethics; one examines the ANAO’s performance statements work; and one considers the Defence Major Projects Report.27 The ANAO provided eight private briefings to the JCPAA and attended 19 public hearings to support the Committee’s inquiries.

1.48 Through the ANAO’s submissions to the Parliament and its performance audit reports, the ANAO has supported the work of the JCPAA and recommendations it has made with respect to assurance of cyber security frameworks (see paragraphs 3.19 to 3.22), improvements to the Commonwealth Grants Framework28 and the Commonwealth Procurement Rules29 (see paragraphs 3.16 to 3.18). Legislative changes have also been progressed, for example, following an ANAO performance audit on telehealth.30

1.49 Based on its audit work, the ANAO further supports the Parliament by appearing before, and providing submissions, briefings and other information to, parliamentary committees on ANAO work in their portfolios of focus. In 2023–24, the ANAO attended nine private briefings to committees, 24 public hearings and one classified hearing. All appearances followed requests from parliamentary committees. The total number of appearances remains consistent with prior reporting cycles with the total of 34 appearances in 2023–24 being equal the total appearances in 2022–23.

1.50 In 2023–24, the ANAO provided 27 private briefings to parliamentarians. Of these, 23 were in relation to specific audit reports, one was in relation to general portfolio matters, one was in relation to the general function of the ANAO, and two were in relation to the ANAO’s support of the JCPAA. Briefings to individual members of Parliament are listed on the ANAO’s website.31

2. Performance audit analysis

Chapter coverage

This chapter provides an analysis of performance audit outcomes from 2019–20 to 2023–24, including:

- audit activity, audit objectives, and stage of delivery against portfolios and audit conclusions;

- entity responses to recommendations, including their implementation; and

- improvements made by entities during audits.

Audit findings

Performance audits conducted by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) in 2023–24 identified deficiencies in public sector governance and procurement activities. Grants administration audits in 2023–24 have seen improvements when compared to largely negative conclusions from the 2019–20 to 2023–24 average. The procurement and grants frameworks are both established under finance law and represent a minimum expectation of compliance and administration. Getting the ‘basics right’ such as adhering to the law, whole-of-government policy and frameworks, and record keeping practices, enables entities to achieve outcomes, minimise risk and make decisions in the public interest. A challenge for leaders is to ensure they consistently demonstrate the expected behaviours, professionalism and standards that promote a culture of compliance with both the letter and intent of the law, along with an expectation that results are achieved.

Poor record keeping practices continued to be an audit finding through 2023–24. Record keeping practices are the creation and storage of decision-based records, including the absence of and quality of (rationale for a decision) documented decisions. Every decision made in the public service is reviewable and demonstrates cost impact, promotes a system that is fit for purpose, contributes to the retention of corporate memory, and is critical to building trust in entity performance and transparency in the spending of public money.

Performance audits analysed from 2019–20 to 2023–24 identified the following key points:

- the National Disability Insurance Agency had the highest percentage of negative conclusions and the highest average number of recommendations while the Social Services and Treasury portfolios had the highest percentages of unqualified conclusions;

- audits with a negative conclusion represented 63 per cent of policy development activity audits, 60 per cent of grants administration activity audits and 53 per cent of procurement activity audits. Audits with a positive conclusion represented 66 per cent of asset management and sustainment activity audits;

- five of the six efficiency audits had negative conclusions; and

- the stage of delivery did not largely impact the percentage of positive or negative conclusions.

Entities fully agreed with more than 90 per cent of recommendations each year from 2019–20 to 2023–24, with 94 per cent of recommendations agreed to in 2023–24. Between 2017–18 and 2021–22, an average of 80 per cent of recommendations were self-reported to be implemented.

From 2021–22, performance audit reports included information in an appendix to capture improvements made by entities during the course of an audit. In 2023–24, 40 of the 45 performance audits (89 per cent) tabled in the Parliament identified improvements during the audit process.

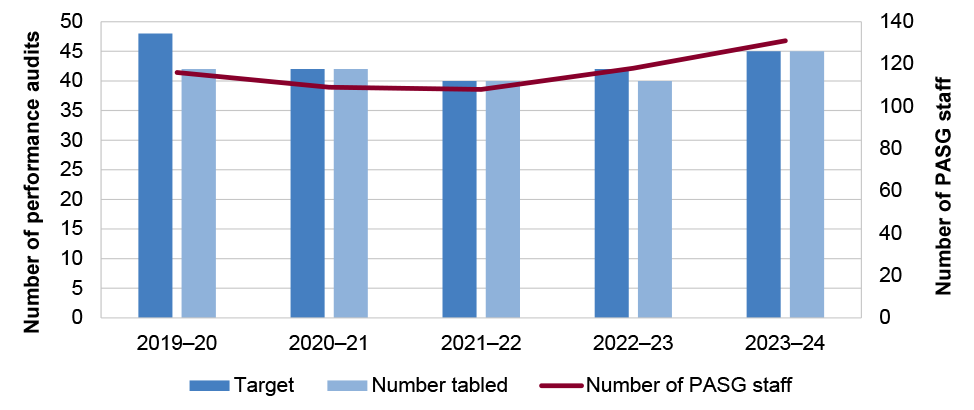

2.1 The ANAO sets performance measures and targets for the number of performance audits to be tabled in the Parliament in its Corporate Plan.32 Figure 2.1 outlines the total number of performance audits tabled compared to the target from 2019–20 to 2023–24, along with the average number of Performance Audit Services Group (PASG) staff across the financial year.

2.2 The ANAO met its Portfolio Budget Statement and Corporate Plan performance audit report targets in 2020–21, 2021–22 and 2023–24. In 2023–24, the ANAO tabled 45 performance audit reports in the Parliament. In 2019–20, the performance audit target was not met. Increased costs in the delivery of the mandatory financial statements audit program affected the ability of the ANAO to resource the performance audit program. In 2022–23, the target was not met due to machinery of government changes resulting in an increased number of entities subject to mandatory financial statements auditing and ANAO resources being directed to that work. The Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit has recommended that the ANAO is funded to achieve an annual target of 48 performance audits.33

Figure 2.1: Number of performance audits tabled compared to performance target and average number of PASG staff

Note: In 2020–21, 41 audits were tabled in the Parliament. Auditor-General Report No. 11 2020–21, Indigenous Advancement Strategy — Children and Schooling Program and Safety and Wellbeing Program was completed as two separate audits but was tabled as a single audit. The audit was counted twice as two audits were completed.

Source: Australian National Audit Office, ANAO Annual Report 2023–24, ANAO, Canberra, 2024, available from https://www.anao.gov.au/work/annual-report/anao-annual-report-2023-24 [accessed 14 October 2024].

2.3 During a performance audit, the ANAO gathers and analyses the evidence necessary to draw a conclusion on the established audit objective. For the purpose of this analysis, audit conclusions are categorised as follows:

- unqualified;

- qualified (largely positive);

- qualified (partly positive); and

- adverse.

2.4 An example of these conclusions, in the context of an audit examining an entity’s effectiveness would be: fully effective; largely effective; partly effective; and not effective. In this chapter, ‘unqualified’ and ‘qualified (largely positive)’ conclusions are considered positive conclusions while ‘qualified (partly positive)’ and ‘adverse’ conclusions are considered negative conclusions.

Portfolio overview of audits

2.5 When developing the Annual Audit Work Program (AAWP) and deciding the audits to commence, the ANAO considers a number of elements including the need to provide a balanced program of activity that is informed by risk and promotes accountability, transparency and improvements to public administration (see paragraphs 1.12 to 1.14).

2.6 Table 2.1 summarises the performance audits tabled in 2023–24, by portfolio that contributed to the performance audit target of 45.

Table 2.1: Portfolio coverage of tabled audits 2023–24

|

Portfolioa |

Countb |

Audits tabled |

|

Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry |

2 |

|

|

Attorney-General’s |

2 |

|

|

Australian Taxation Office |

2 |

|

|

Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water |

4 |

|

|

Defence |

3 |

|

|

Education |

2 |

|

|

Employment and Workplace Relations |

2 |

|

|

Finance |

3 |

|

|

Foreign Affairs and Trade |

1 |

|

|

Health and Aged Care |

5 |

|

|

Home Affairs |

3 |

|

|

Industry, Science and Resources |

2 |

|

|

Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts |

5 |

|

|

National Disability Insurance Agency |

2 |

|

|

Parliamentary Departments |

0 |

|

|

Prime Minister and Cabinet |

3 |

|

|

Services Australia |

3 |

|

|

Social Services |

2 |

|

|

Treasury |

3 |

|

|

Veterans’ Affairs |

2 |

|

Note a: The ANAO’s 2023–24 AAWP is categorised into 20 Australian Government portfolios. This is based on the Administrative Arrangements Order – 13 October 2022 (as amended 3 August 2023), which provides the legislative basis for the entity allocations to portfolios. Four entities are split out from their designated portfolio due to materiality and complexity: Services Australia and the National Disability Insurance Agency are split out from the Social Services portfolio; the Australian Taxation Office is split out from the Treasury portfolio; and Veteran’s Affairs (including the Department of Veterans’ Affairs and the Australian War Memorial) is split out from the Defence portfolio.

Note b: There is a total of 51 audits listed. This includes 45 tabled audits plus 6 entries addressing cross-entity audits.

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audit reports from 2023–24.

2.7 The Health and Aged Care and Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts34 portfolios had the highest number of audits tabled in 2023–24, with a total of five each. The portfolios with the lowest number of audits tabled in 2023–24 were Parliamentary Departments (nil audits) and Foreign Affairs and Trade (one audit).

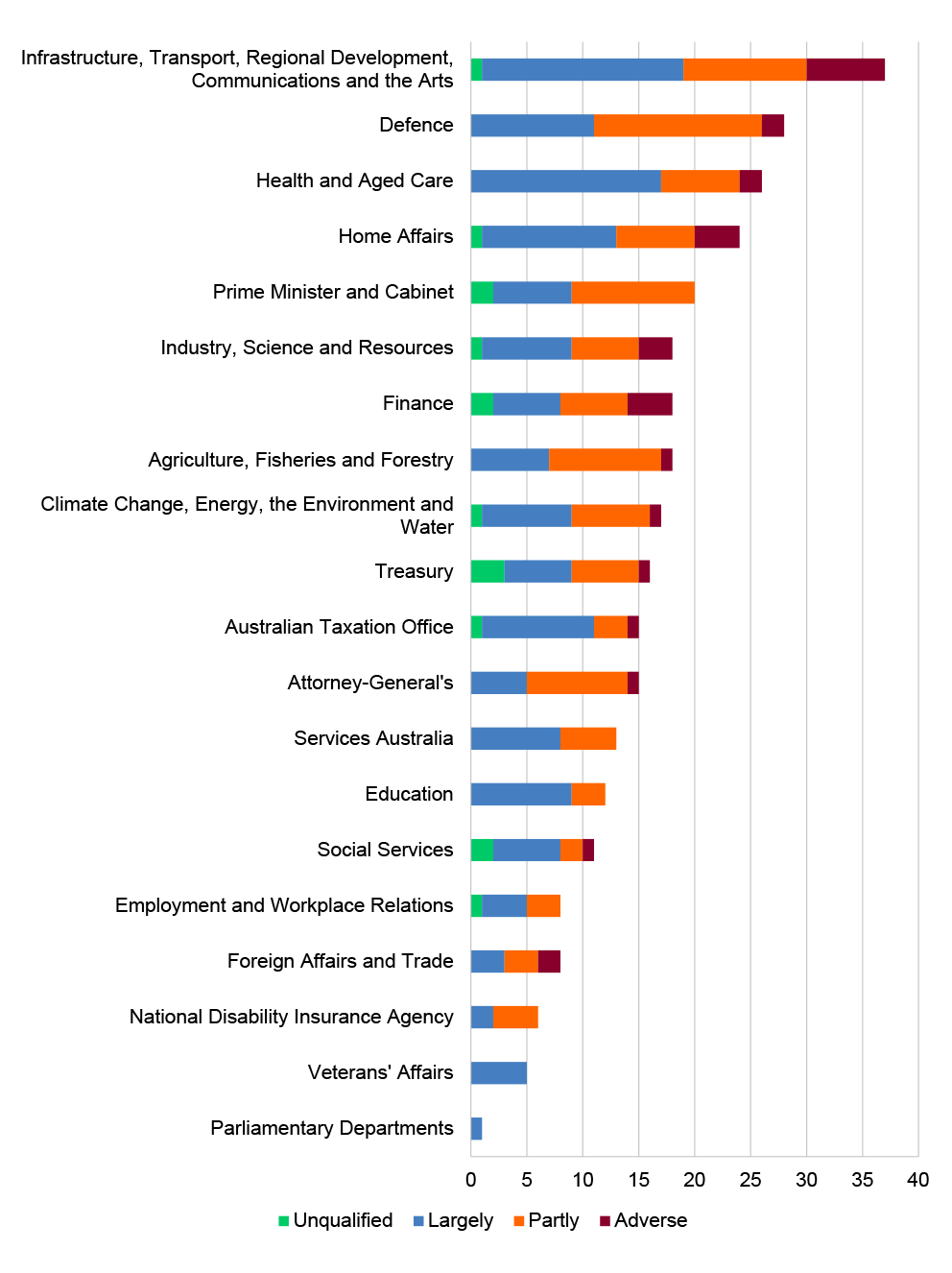

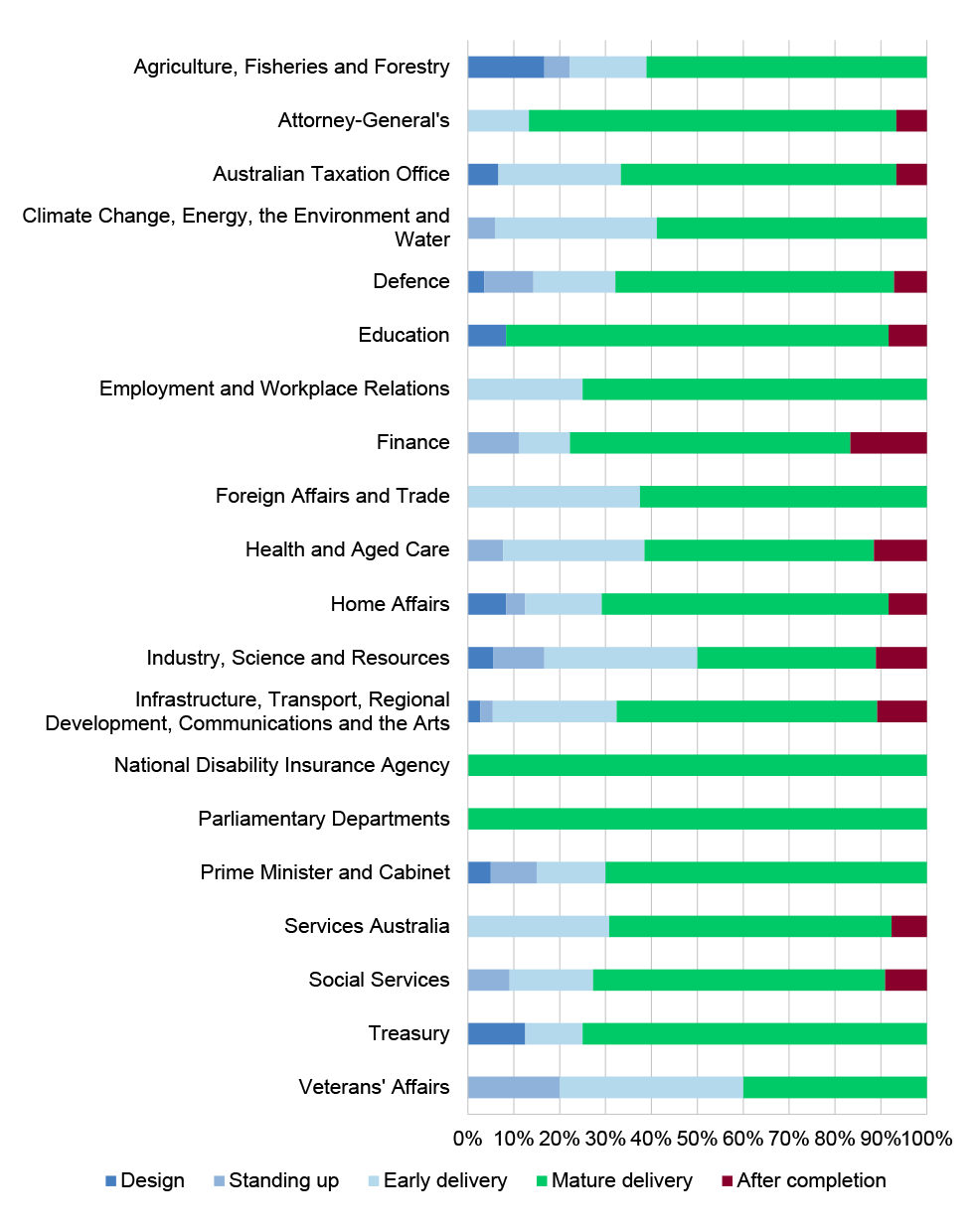

2.8 The number of audits tabled in each portfolio and their audit conclusion for 2019–20 to 2023–24 is shown in Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2: Number of audits tabled in each portfolio and their conclusion, tabled audits 2019–20 to 2023–24

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audit reports from 2019–20 to 2023–24.

2.9 The Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts portfolio had the highest number of audits between 2019–20 and 2023–24, with 37 audits tabled. The Defence portfolio was the second highest with 28 audits tabled between 2019–20 and 2023–24.35

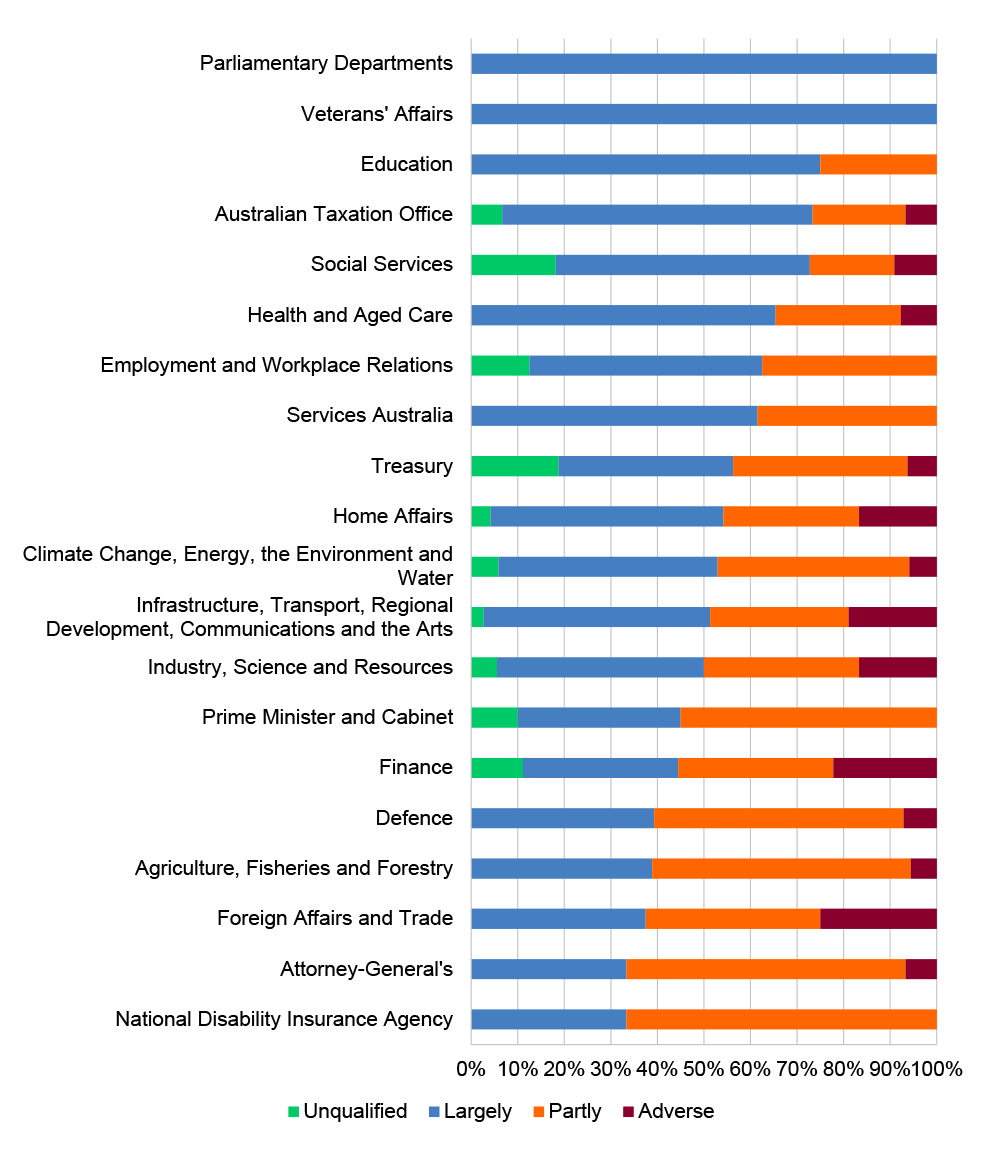

2.10 All performance audits in the Parliamentary Departments and Veterans’ Affairs portfolios had largely effective conclusions. Two thirds of the performance audits in the National Disability Insurance Agency and Attorney-General’s portfolio had negative conclusions (see Figure 2.3, ordered from highest percentage of positive conclusions). The Foreign Affairs and Trade portfolio had the highest percentage of adverse conclusions. The Social Services and Treasury portfolios36 had the highest percentage of unqualified conclusions.

Figure 2.3: Percentage of audit conclusion for each portfolio, tabled audits 2019–20 to 2023–24

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audit reports from 2019–20 to 2023–24.

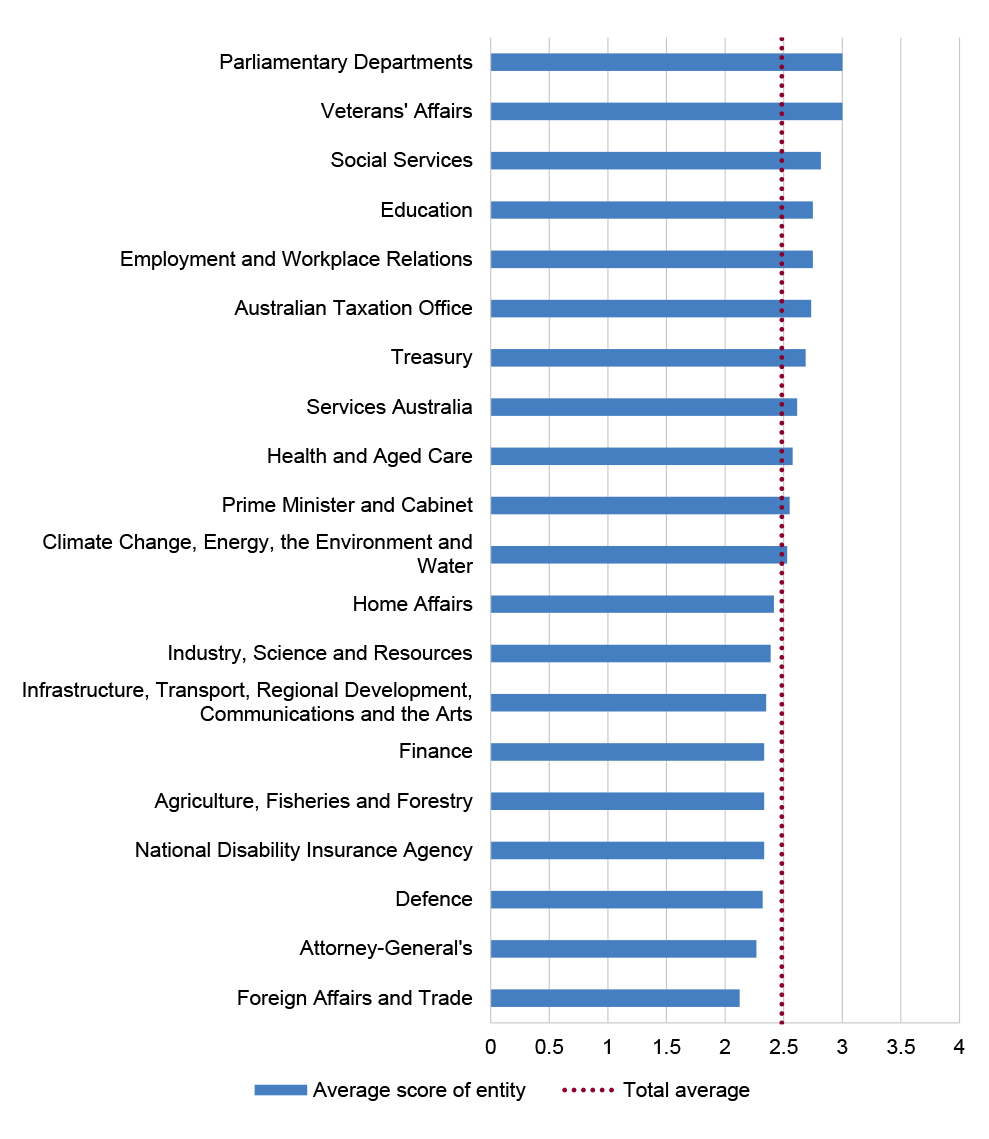

2.11 The four audit conclusion categories (see paragraph 2.3) were assigned a score on a four-point scale (‘unqualified’ with a score of four to ‘adverse’ with a score of one). Figure 2.4 outlines the average score based on audit conclusions by portfolio, with the Foreign Affairs and Trade and Attorney-General’s portfolios being the lowest two scoring portfolios. The average score across all portfolios was 2.5.

Figure 2.4: Average score based on audit conclusions by portfolio, tabled audits 2019–20 to 2023–24

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audit reports from 2019–20 to 2023–24.

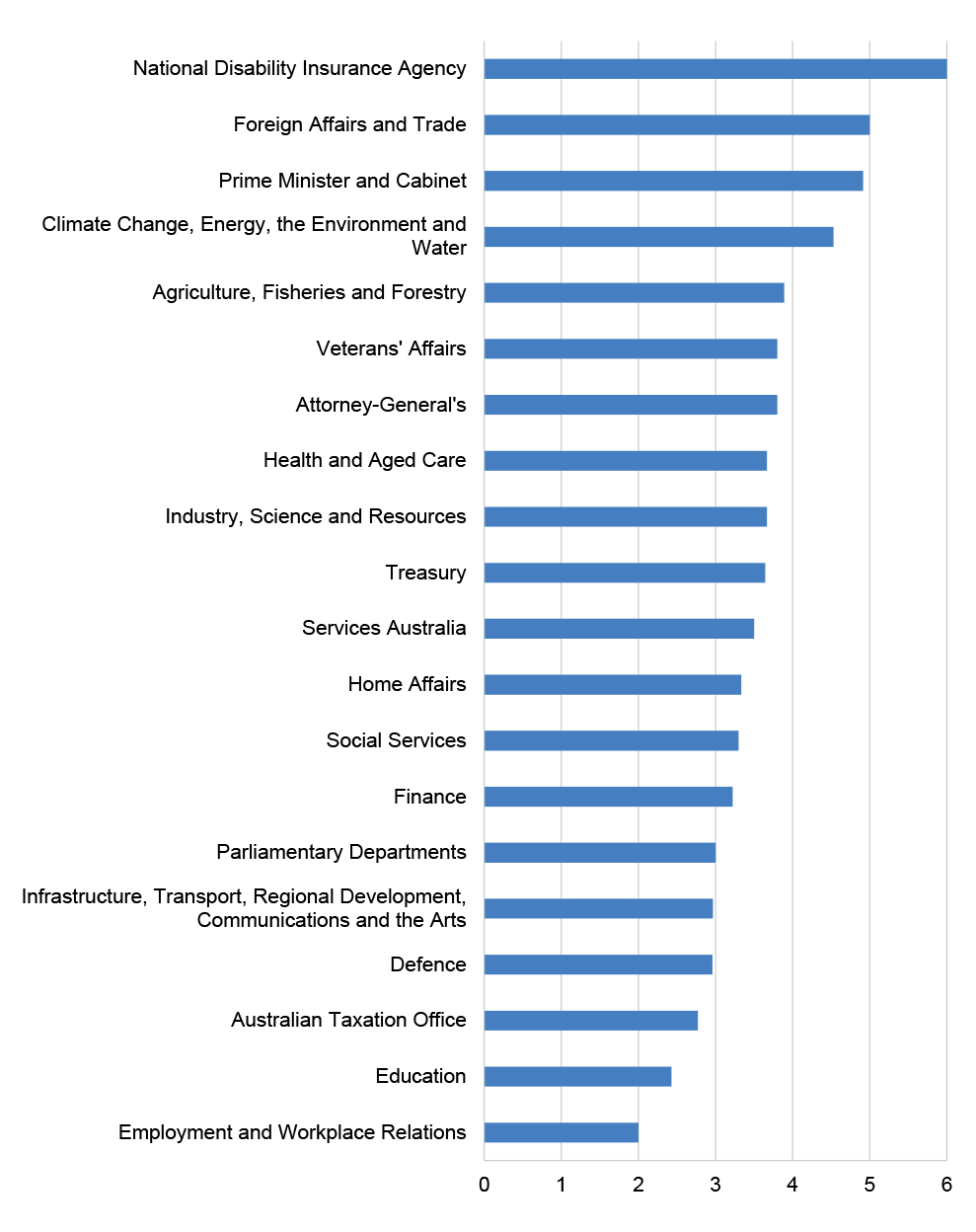

2.12 Figure 2.5 displays the average number of recommendations per audit by portfolio. The National Disability Insurance Agency received the highest average number of recommendations per audit (six recommendations). The Foreign Affairs and Trade portfolio received an average of five recommendations per audit. The Prime Minister and Cabinet, and Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water portfolios received an average of 4.9 and 4.5 recommendations per audit, respectively. The Employment and Workplace Relations portfolio received the lowest average number of recommendations per audit (two recommendations).

Figure 2.5: Average number of recommendations per audit by portfolio, tabled audits 2019–20 to 2023–24

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audit reports from 2019–20 to 2023–24.

Analysis by audit activity

2.13 All performance audits consider one of seven key audit ‘activity’ descriptors as part of the topic development process for the AAWP. The scope of the activity descriptors is shown in Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: Audit activity descriptors and what they encompass

|

Activity |

Includes |

|

Asset management and sustainment |

Asset capability maintenance, deployment readiness, property and infrastructure services, condition assessment, replacement and repair. |

|

Governance |

Internally focussed — governance oversight frameworks, performance measurement, impact measurement, monitoring and reporting, risk identification, assessment and monitoring, strategic planning, business continuity, implementation/operational planning, financial management (including implementation of savings measures), fraud control and probity management. |

|

Procurement |

Needs assessment, approach to market, tender assessment, acquisition, delivery of requirements, contract negotiation. |

|

Regulatory |

Regulatory intelligence collection, assessment, exchange, compliance activities, inspections, investigations and enforcement. |

|

Grants administration |

Program guidelines, grant assessment, contract management, acquittal and performance. |

|

Service delivery |

Externally focussed — customer facing delivery or enabling of delivery through a third party. Includes program administration, MOUs/intergovernmental agreements, record keeping (applies across all), grant programs, social support, contract management. |

|

Policy development |

Advice to government, white papers, discussion papers, industry consultation, development and assessment of options, policy proposals, use of technical expertise, strategic planning, development and approvals for legislative change, risk identification, design of oversight arrangements, stakeholder engagement. |

Source: ANAO.

2.14 The audit program is intended to deliver a mix of audits across each of these activities. Table 2.3 outlines the audit coverage by primary audit activity37, from highest to lowest, for 2019–20 to 2023–24.

Table 2.3: Audit coverage by audit activity

|

Activity |

2019–20 to 2023–24 |

2022–23 |

2023–24 |

|||

|

|

Number of audits |

% |

Number of audits |

% |

Number of audits |

% |

|

Governance |

64 |

30 |

10 |

25 |

16 |

36 |

|

Service delivery |

41 |

20 |

8 |

10 |

7 |

16 |

|

Procurement |

36 |

17 |

7 |

17.5 |

7 |

16 |

|

Regulatory |

34 |

16 |

7 |

17.5 |

7 |

16 |

|

Grants administration |

19 |

9 |

4 |

10 |

4 |

9 |

|

Asset management and sustainment |

9 |

4 |

2 |

5 |

1 |

2 |

|

Policy development |

6 |

3 |

2 |

5 |

3 |

7 |

|

Total |

209 |

100 |

40 |

100 |

45 |

100 |

Note: Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding.

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audits from 2019–20 to 2023–24.

2.15 Governance activity audits have the highest number of tabled audits, averaging 30 per cent across 2019–20 to 2023–24 and comprising 25 per cent of audits in 2022–23 and 36 per cent of audits in 2023–24. This is followed by service delivery, comprising an average of 20 per cent of audits across 2019–20 to 2023–24.

Analysis by portfolio

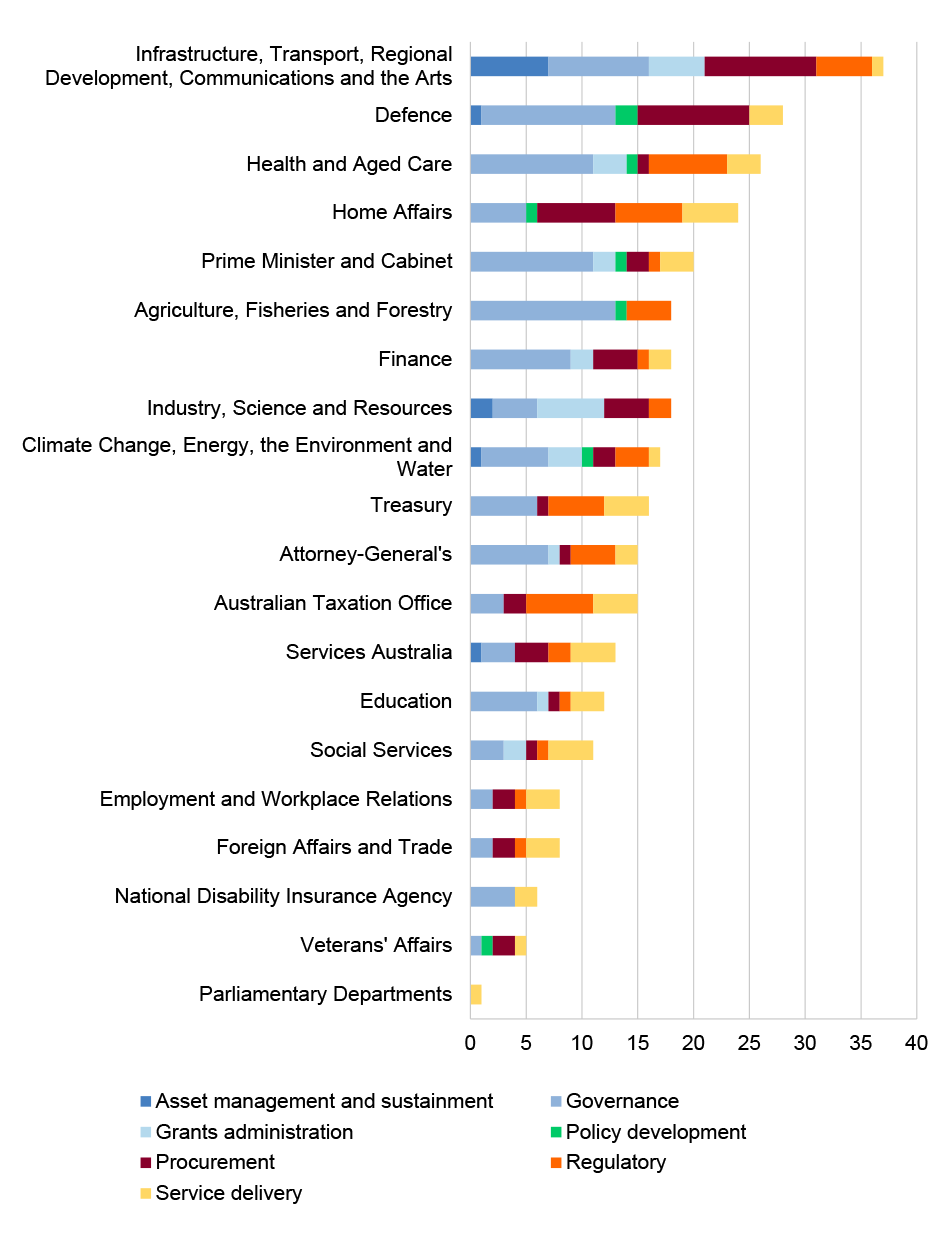

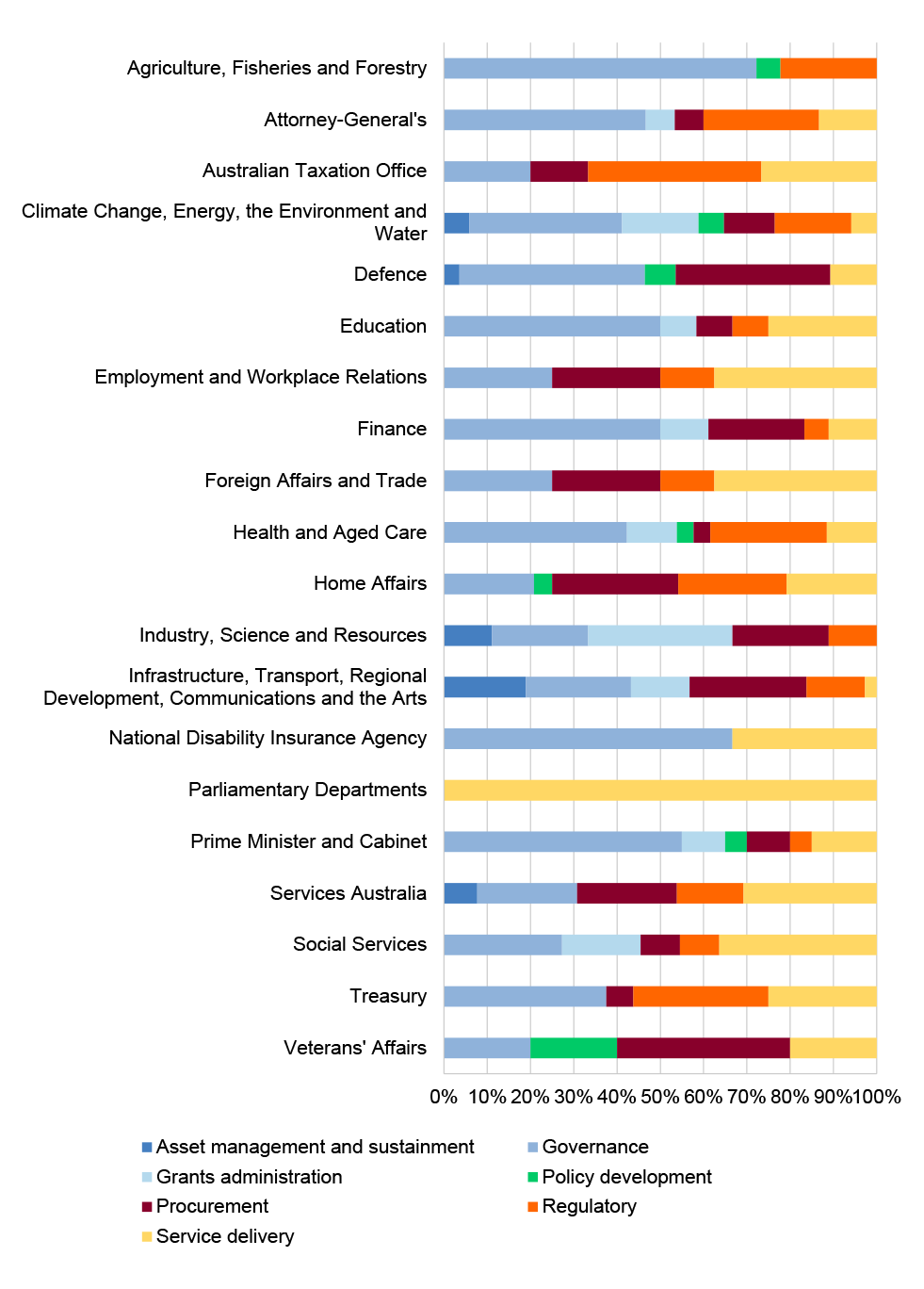

2.16 Figure 2.6 breaks down the spread of activities by portfolio for the period 2019–20 to 2023–24.

Figure 2.6: Audit activity by portfolio, tabled audits 2019–20 to 2023–24

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audits from 2019–20 to 2023–24.

2.17 The Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts portfolio had the highest number of audits for asset management and sustainment, at seven audits. The Industry, Science and Resources portfolio had the highest number of grants administration audits, at six audits. Defence, and the Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts portfolios had the highest number of procurement audits, at 10 audits each. Governance, policy development, regulatory, and service delivery audits were relatively well spread across all portfolios.

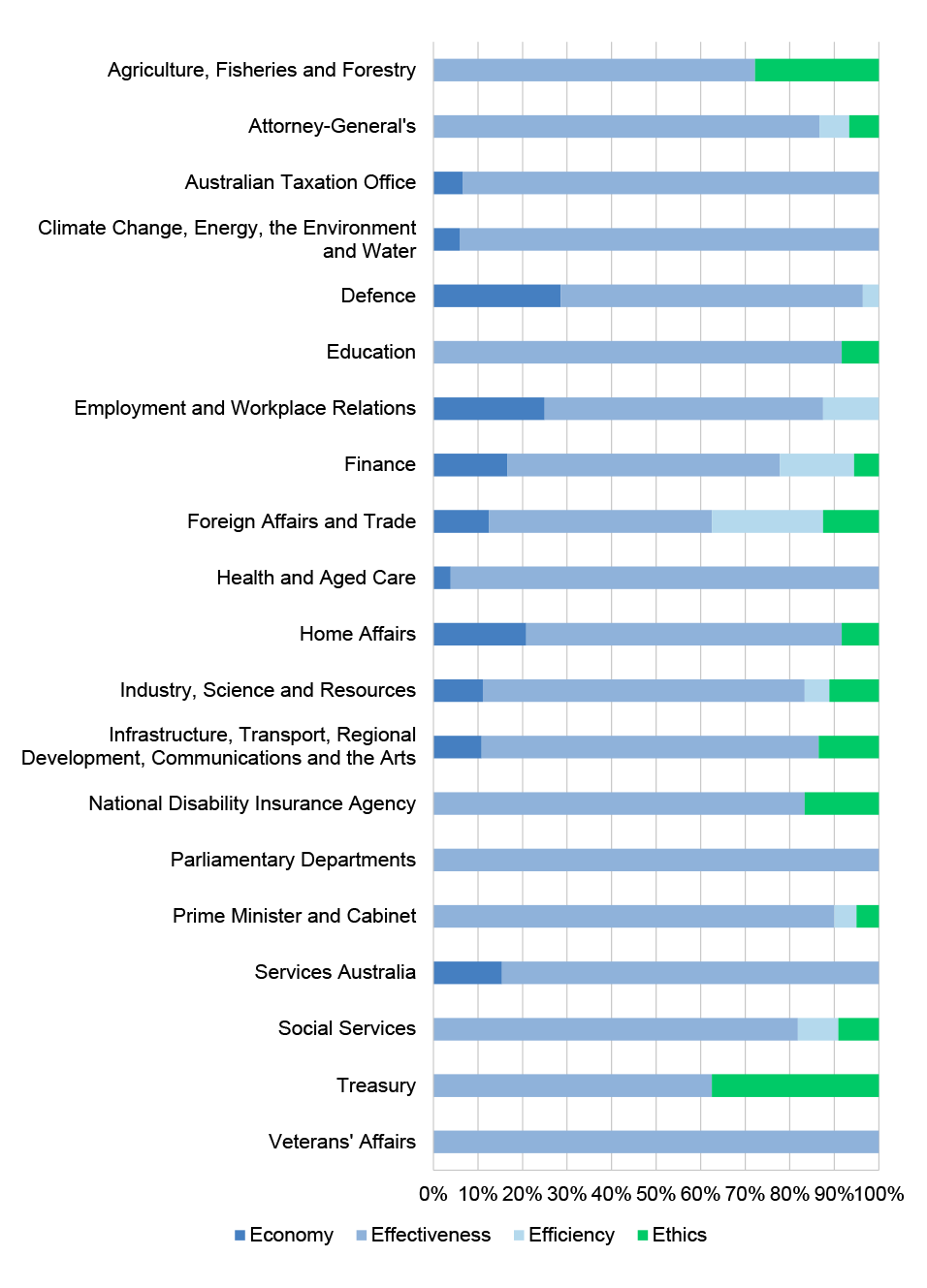

2.18 When viewed as a percentage of audit activity within each portfolio for 2019–20 to 2023–24 (see Figure 2.7):

- 19 per cent of audits in the Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts portfolio were asset management and sustainment activities;

- 72 per cent of audits in the Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry portfolio were governance activities;

- 33 per cent of audits in the Industry, Science and Resources portfolio were grants administration activities;

- 20 per cent of audits in the Veterans’ Affairs portfolio were policy development activities;

- 40 per cent of audits in the Veterans’ Affairs portfolio, 36 per cent in the Defence portfolio, 29 per cent in the Home Affairs portfolio, and 27 per cent in the Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts portfolio were procurement activities;

- 40 per cent of audits in the Australian Taxation Office were regulatory activities; and

- 38 per cent of audits in the Employment and Workplace Relations portfolio, 38 per cent in Foreign Affairs and Trade, 36 per cent in Social Services, 33 per cent in the National Disability Insurance Agency and 31 per cent Services Australia were service delivery activities.

Figure 2.7: Percentage of audit activity by portfolio, tabled audits 2019–20 to 2023–24

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audits from 2019–20 to 2023–24.

Analysis by conclusion

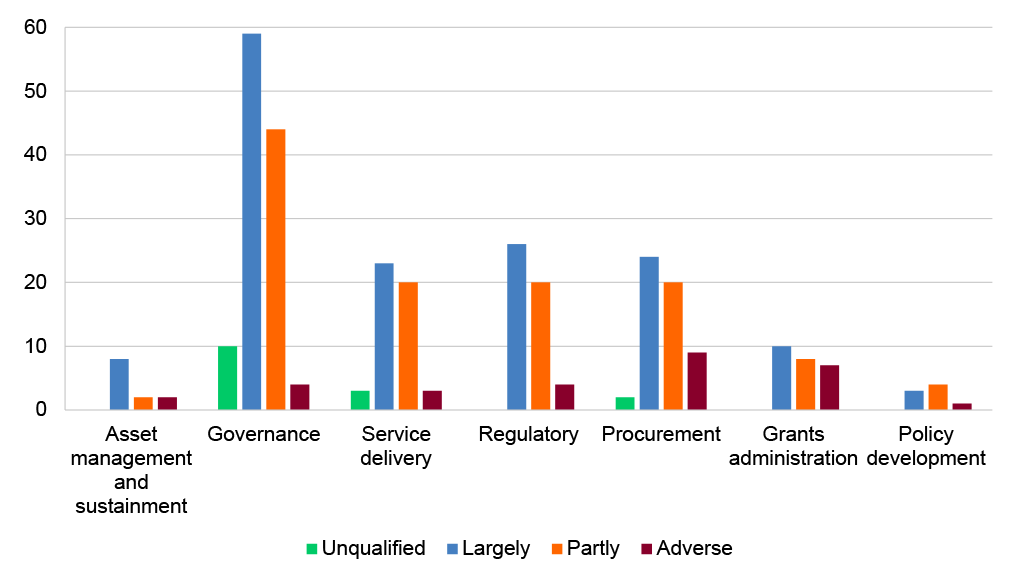

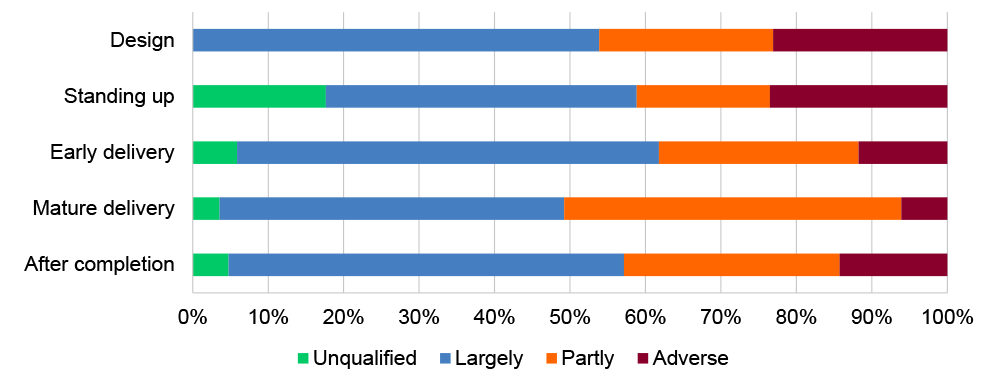

2.19 Figure 2.8 displays the number of audit conclusions by audit activity. Figure 2.9 outlines the percentage of audit conclusions by audit activity.

Figure 2.8: Audit conclusions by audit activity, tabled audits 2019–20 to 2023–24

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audits from 2019–20 to 2023–24.

2.20 Audits focused on policy development activities had the highest ratio of negative conclusions over 2019–20 to 2023–24, with 63 per cent of audit conclusions categorised as partly positive or adverse. Sixty per cent of grants administration audits had negative conclusions over 2019–20 to 2023–24. Audits focused on asset management and sustainment activities had the highest ratio of positive conclusions over 2019–20 to 2023–24, with 66 per cent of audits categorised as largely positive. Fifty-nine per cent of governance activity audits over 2019–20 to 2023–24 had positive conclusions.

2.21 In 2023–24, 61 per cent of audits focused on governance activities had negative conclusions, in contrast to the 59 per cent of governance activity audits having positive conclusions over 2019–20 to 2023–24. Policy development activity audits had a similar percentage of negative conclusions in 2023–24 compared to the average from 2019–20 to 2023–24, with 60 per cent of audits having negative conclusions. Grants administration activity audits had 80 per cent of audits with positive conclusions in 2023–24, a reversal of the average from 2019–20 to 2023–24 where 60 per cent had negative conclusions.

Figure 2.9: Percentage of audit conclusions by audit activity, tabled audits 2019–20 to 2023–24

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audits from 2019–20 to 2023–24.

Analysis by audit objective

2.22 Subsection 15(1) of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) provides that the accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity must govern the entity in a way that promotes the proper use and management of public resources. The PGPA Act defines ‘proper’ as efficient, effective, economical and ethical. Entities are also obliged to comply with relevant legislative requirements, and for non-corporate Commonwealth entities, operate in a way that is not inconsistent with the policies of the Australian Government.

2.23 In consideration of the obligations set out under the PGPA Act, each performance audit makes a conclusion on whether the entity achieved the objective of being efficient, effective, economical and/or ethical in its implementation of the program or activity under examination.

2.24 Table 2.4 outlines the number and percentage of audits against each of the four objectives.

Table 2.4: Audit coverage by objective

|

Objective |

2019–20 to 2023–24 |

2022–23 |

2023–24 |

|||

|

|

Number of audits |

% |

Number of audits |

% |

Number of audits |

% |

|

Effectiveness |

161 |

77 |

27 |

68 |

32 |

71 |

|

Economy |

22 |

11 |

6 |

15 |

4 |

9 |

|

Ethicsa |

20 |

10 |

5 |

13 |

8 |

18 |

|

Efficiency |

6 |

3 |

2 |

5 |

1 |

2 |

|

Total |

209 |

100 |

40 |

100 |

45 |

100 |

Note: Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding.

Note a: Ethics objective audits examine elements such as honesty, integrity, probity, diligence, fairness and consistency. For example, in 2023–24, six of the ethics objective audits tabled in the Parliament related to compliance with corporate credit card or gifts, benefits and hospitality requirements (see paragraphs 3.8 to 3.12).

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audits from 2019–20 to 2023–24.

2.25 Effectiveness objective audits represented 77 per cent of performance audits undertaken from 2019–20 to 2023–24. Economy and ethics objective audits represented 11 and 10 per cent, respectively, over 2019–20 to 2023–24. Thirteen of the 20 ethics objective audits were completed in 2022–23 and 2023–24. Efficiency objective audits were the lowest percentage of audits performed, representing three per cent of audits from 2019–20 to 2023–24.

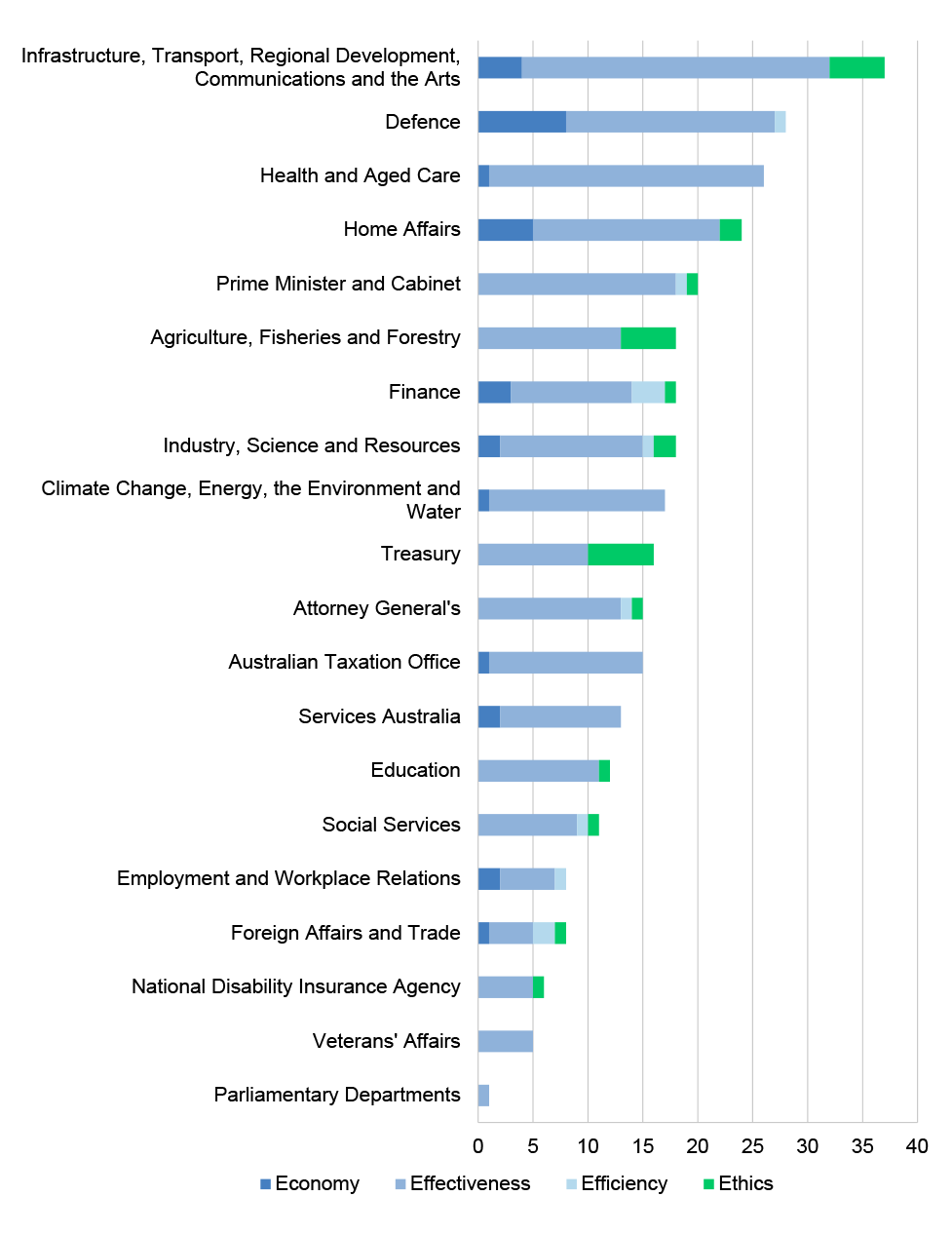

Analysis by portfolio

2.26 Figure 2.10 displays the portfolio coverage by audit objective.

Figure 2.10: Audit objective by portfolio, tabled audits 2019–20 to 2023–24

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audits from 2019–20 to 2023–24.

2.27 Between 2019–20 and 2023–24 there were:

- economy objective — eight audits in the Defence portfolio; and

- ethics objective — six audits in the Treasury portfolio, five audits in the Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts portfolio, and five audits in the Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry portfolio.

2.28 When viewed as a percentage of audit objectives within each portfolio for 2019–20 to 2023–24 (see Figure 2.11):

- economy objective — 29 per cent of audits in the Defence portfolio and 25 per cent of audits in Employment and Workplace Relations portfolio;

- ethics objective — 38 per cent of audits in the Treasury portfolio; and

- efficiency object — 25 per cent of audits in the Foreign Affairs and Trade portfolio.

Figure 2.11: Percentage of audit objective by portfolio, tabled audits 2019–20 to 2023–24

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audits from 2019–20 to 2023–24.

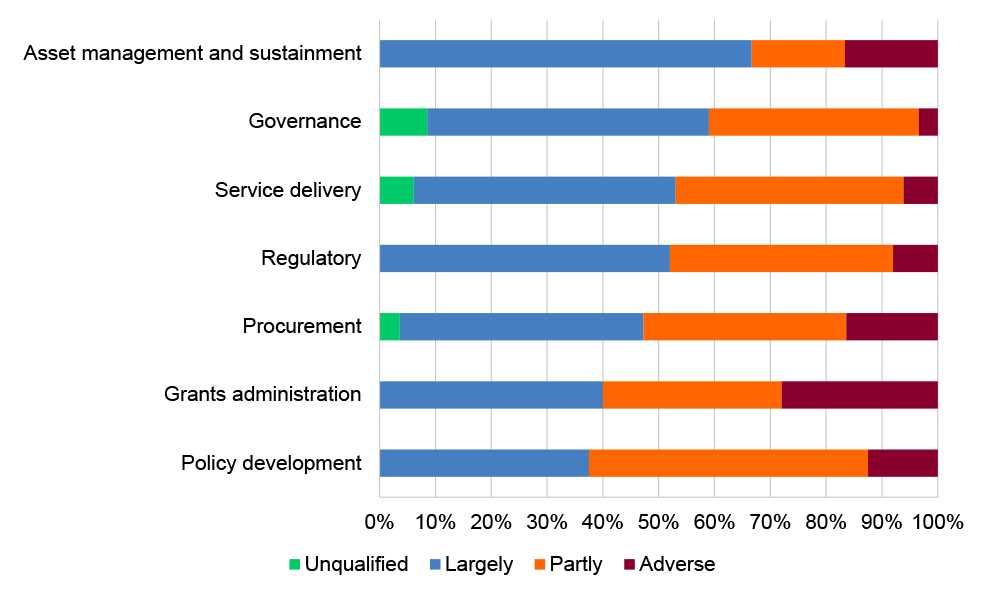

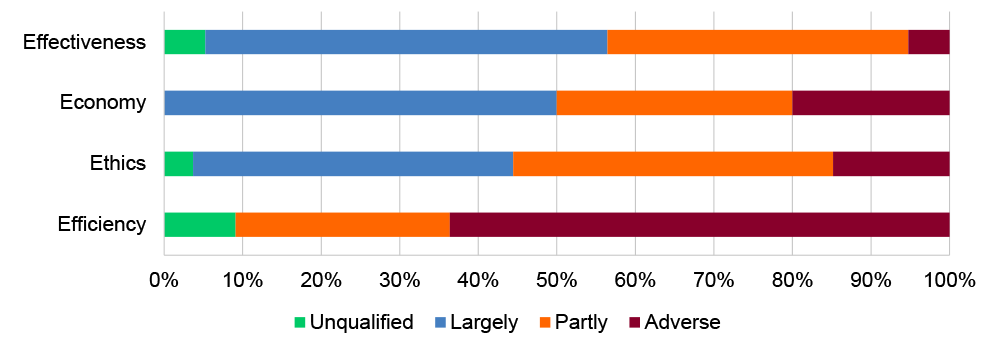

Analysis by conclusion

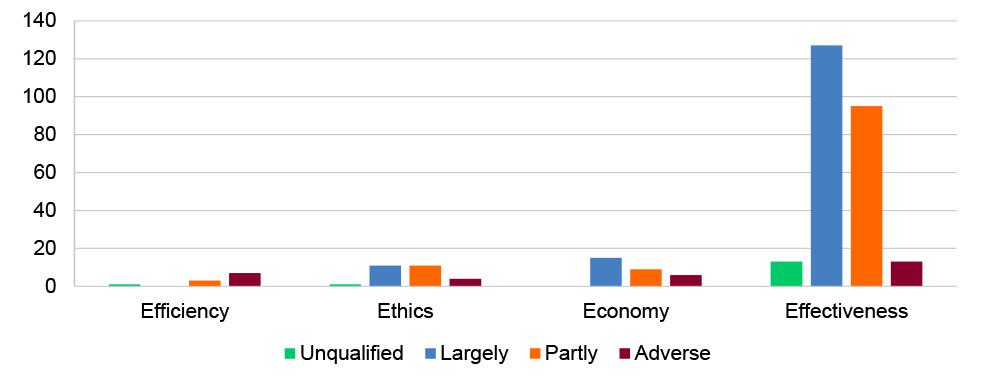

2.29 Figure 2.12 outlines audit conclusion categories against the audit objective, with Figure 2.13 showing the percentage of audit objectives by conclusion, from highest percentage of positive conclusions.

Figure 2.12: Audit objective by conclusion, tabled audits 2019–20 to 2023–24

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audits from 2019–20 to 2023–24.

2.30 Efficiency objective audits had the highest ratio of negative conclusions, with five of the six efficiency objective audits having negative conclusions over 2019–20 to 2023–24. Economy, effectiveness and ethics objective audits had relatively comparable ratios of positive versus negative conclusions over 2019–20 to 2023–24.

2.31 In 2023–24 the percentage of ethics objective audits with negative conclusions increased to 75 per cent. Economy and effectiveness objective audits in 2023–24 were comparable to the average from 2019–20 to 2023–24, with 50 per cent of economy objective audits and 60 per cent of effectiveness objective audits having positive conclusions in 2023–24. One efficiency audit was completed in 2023–24, which had a negative conclusion.38

Figure 2.13: Percentage of audit objective by conclusion, tabled audits 2019–20 to 2023–24

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audits from 2019–20 to 2023–24.

Analysis by stage of delivery

2.32 Australian Government programs and activities present a variety of risk profiles related to their stage of maturity. The ANAO seeks to provide assurance over a range of programs and activities across different stages of implementation maturity. Audits of programs in the design, standing up and early delivery phases enable insights to be made that assist implementation and delivery. Audits of programs at the mature delivery and after completion stage aim to provide findings directed towards assurance, evidence collection, lessons learned for future programs, and delivery of objectives. Table 2.5 outlines that programs in the mature delivery phase are those most commonly audited. This remained largely unchanged in 2023–24 compared to previous years.

Table 2.5: Audit coverage by delivery stage

|

Stage of delivery |

2019–20 to 2023–24 |

2022–23 |

2023–24 |

|||

|

|

Number of audits |

% |

Number of audits |

% |

Number of audits |

% |

|

Mature delivery |

131 |

63 |

27 |

68 |

28 |

62 |

|

Early delivery |

47 |

22 |

6 |

15 |

12 |

27 |

|

Standing up |

12 |

6 |

1 |

3 |

2 |

4 |

|

Design |

9 |

4 |

4 |

10 |

2 |

4 |

|

After completion |

10 |

5 |

2 |

5 |

1 |

2 |

|

Total |

209 |

100 |

40 |

100 |

45 |

100 |

Note: Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding.

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audits from 2019–20 to 2023–24.

Analysis by portfolio

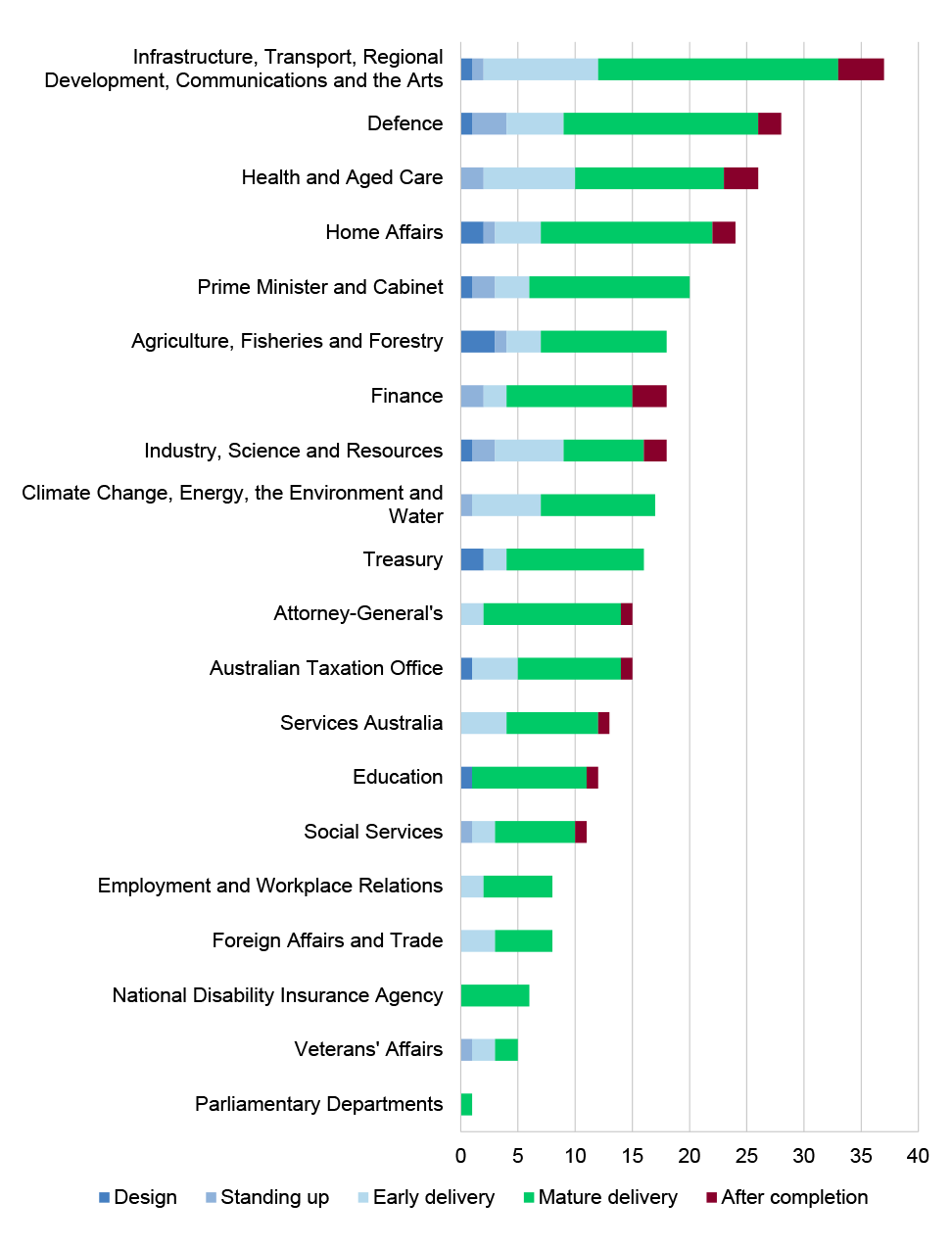

2.33 Figure 2.14 shows the portfolio coverage by stage of delivery.

Figure 2.14: Stage of delivery by portfolio, tabled audits 2019–20 to 2023–24

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audits from 2019–20 to 2023–24.

2.34 Between 2019–20 and 2023–24, the ratio of portfolio coverage against the five stages of delivery was comparable to the overall coverage shown in Table 2.5.

Figure 2.15: Percentage of stage of delivery by portfolio, tabled audits 2019–20 to 2023–24

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audits from 2019–20 to 2023–24.

Analysis by audit conclusion

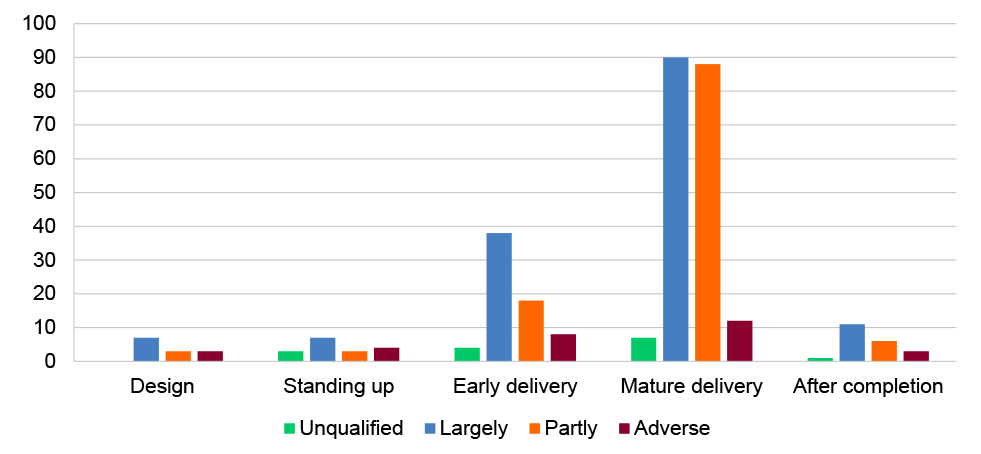

2.35 Figure 2.16 displays performance audit conclusions by stage of delivery, with Figure 2.17 showing the stage of delivery by conclusion percentages.

Figure 2.16: Performance audit conclusions by stage of delivery, tabled audits 2019–20 to 2023–24

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audits from 2019–20 to 2023–24.

2.36 In the five years from 2019–20 to 2023–24, there was a relatively even spread of positive versus negative conclusions against the five stages of delivery. In 2023–24, 58 per cent of audits under mature delivery had negative conclusions and 66 percent of audits under early delivery had positive conclusions, comparable to the average for 2019–20 to 2023–24. The number of audits tabled in the after completion, standing up and design delivery stages were too low to provide a comparison in 2023–24 (see Table 2.5).

Figure 2.17: Percentage of performance audit conclusions by stage of delivery, tabled audits 2019–20 to 2023–24

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audits from 2019–20 to 2023–24.

Analysis of entity responses to recommendations

ANAO recommendations

2.37 Through performance audits, the ANAO identifies areas where improvements can be made to aspects of public administration and makes specific recommendations to assist public sector entities to improve their management.

2.38 Under section 19 of the Auditor-General Act 1997, the ANAO provides a copy of the proposed performance audit report, including any proposed recommendations, to entities before the finalisation of the report. Entity responses to recommendations are reproduced in the body of the final audit report. As the entity’s response is being presented to Parliament with its view of recommendations, it is expected that the response indicates whether the entity agrees or disagrees with each recommendation. This formalises an entity’s commitment to the Parliament to implement the recommendations it has agreed with.

2.39 The ANAO’s regular engagement with entities during the audit process means that they are aware of the issues likely to be raised in a report. Any disagreement with recommendations is worked through with the auditors and entities before finalisation of the audit report. On occasion, the Auditor-General makes recommendations to government where, through audit work, deficiencies or gaps in rules and/or frameworks are identified — these are generally noted by the relevant lead policy entity given that those recommendations will require advice to government.

2.40 The ANAO analyses the rate of entities’ agreement to recommendations in its performance audit reports. The four categories for assessing agreement to recommendations are:

- fully agreed;

- agreed with some qualification (including partly agree and agree in principle);

- noted or no response; and

- disagreed.

2.41 The degree of agreement with ANAO recommendations is an important indicator of acknowledgement by accountable authorities to areas of administration which need attention (see paragraph 2.39).

2.42 Table 2.6 outlines the number of performance audit recommendations made and agreed to by financial year for 2017–18 to 2023–24. From 2017–18 to 2023–24 the ANAO made 1188 recommendations with 92 per cent fully agreed to by entities.

Table 2.6: Number of recommendations made by the ANAO and agreed to by entities

|

Financial year |

Number of recommendations |

Number of fully agreed recommendations by entities |

Percentage of agreed recommendations by entities (%) |

|

2017–18 |

126 |

107 |

85 |

|

2018–19 |

146 |

131 |

90 |

|

2019–20 |

141 |

128 |

91 |

|

2020–21 |

165 |

152 |

92 |

|

2021–22 |

161 |

154 |

96 |

|

2022–23 |

194 |

177 |

91 |

|

2023–24 |

255 |

240 |

94 |

|

Total |

1188 |

1094 |

92a |

Note: A recommendation is considered agreed if more than 50 per cent of entities the recommendation is made to agree to the recommendation without qualification.

Note a: The average percentage of recommendations agreed by entities for 2017–18 to 2023–24 is shown.

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audits published 2017–18 to 2023–24.

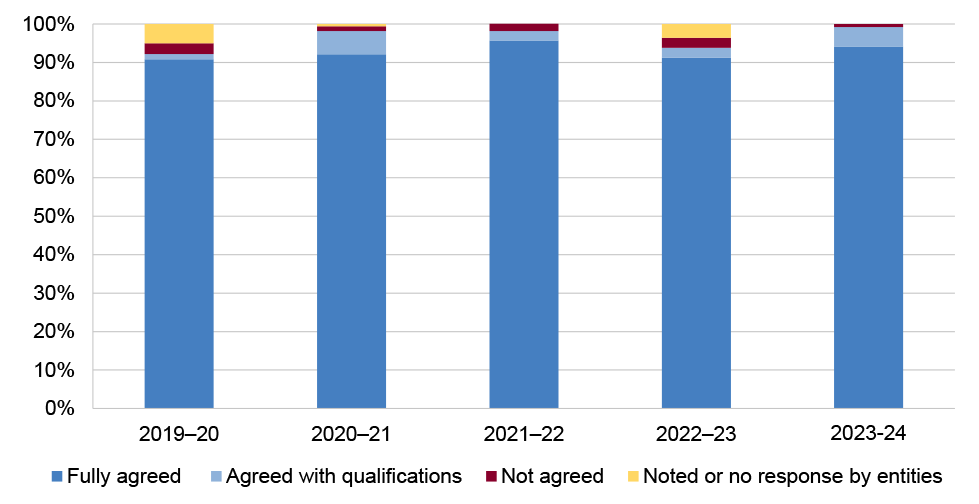

2.43 The 45 performance audit reports tabled in the Parliament in 2023–24 contained 255 recommendations, of which 94 per cent were agreed in full. The number of recommendations made is an increase on the previous year (194 recommendations in 40 audit reports with 91 per cent agreed in full), reflecting both the increase in the number of audit reports tabled, and the nature of the reports themselves.

2.44 Figure 2.18 displays the entity responses to ANAO recommendations over the last five financial years. The vast majority of recommendations are fully agreed to every year.

Figure 2.18: Entity response to recommendations by financial year, tabled audits 2019–20 to 2023–24

Source: Australian National Audit Office, ANAO Annual Report 2023–24, ANAO, Canberra, 2024, available from https://www.anao.gov.au/work/annual-report/anao-annual-report-2023-24 [accessed 14 October 2024].

Analysis by portfolio

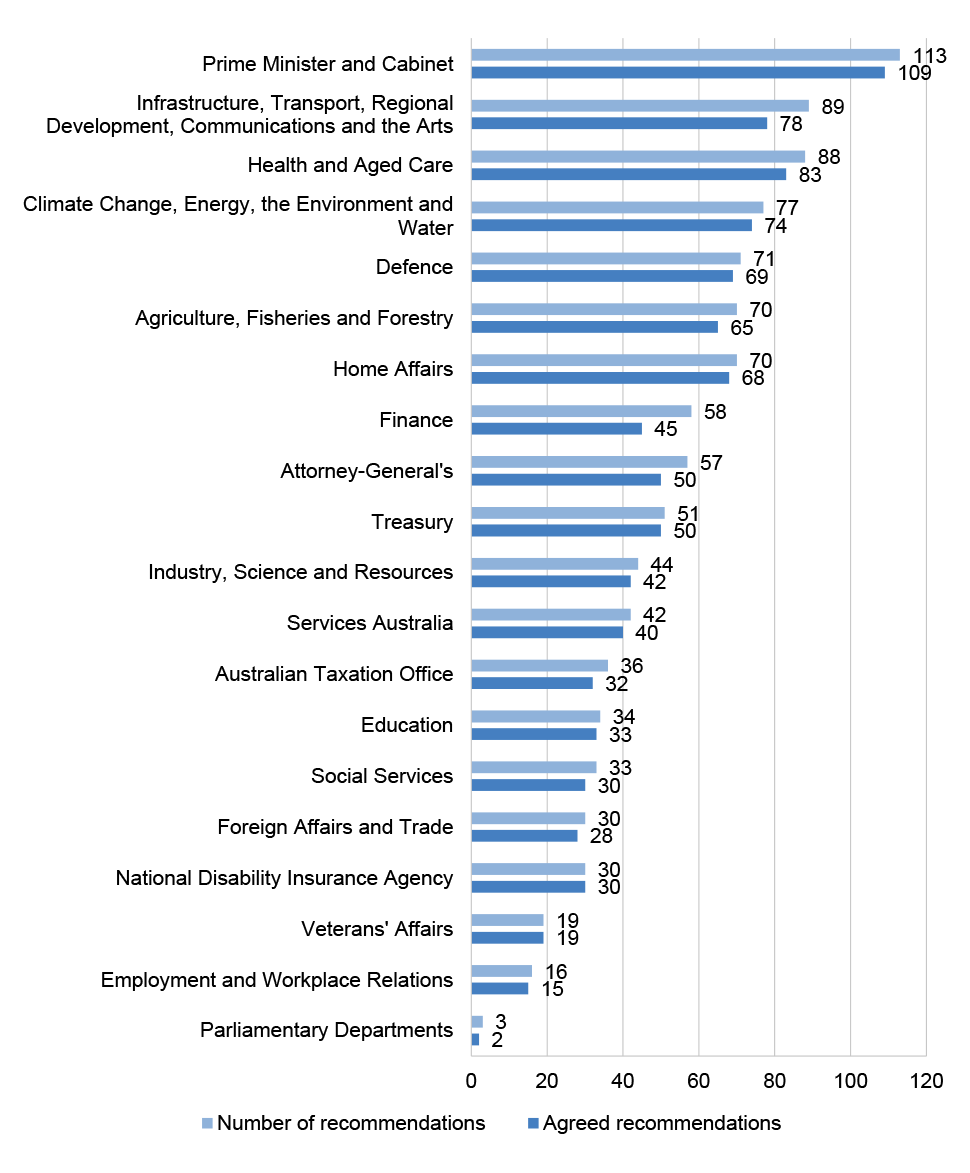

2.45 Figure 2.19 compares the number of recommendations received and the number of recommendations fully agreed to by portfolio from highest to lowest number of recommendations, for the period 2019–20 to 2023–24.

Figure 2.19: Recommendations received and fully agreed to by portfolio, tabled audits 2019–20 to 2023–24

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audits published 2019–20 to 2023–24.

2.46 The Prime Minister and Cabinet portfolio received the highest number of recommendations39, followed by the Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts, and the Health and Aged Care portfolios.

2.47 The National Disability Insurance Agency and Veterans’ Affairs fully agreed to all ANAO recommendations over the last five financial years. The Finance portfolio has the highest number of recommendations not fully agreed to (13 recommendations). ANAO recommendations directed at amending whole-of-government rules or policies are often noted by the Department of Finance on the basis that legislative and policy matters require government consideration.40 The Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts portfolio has not fully agreed to 11 recommendations.

Implementation of recommendations

2.48 The ANAO monitors entities’ implementation of performance audit recommendations by attending entity audit committees (as an observer) and conducting audits that follow up on entity progress in implementing previously made recommendations. In order to report against performance measure 9 included in the ANAO’s Corporate Plan, ‘Percentage of ANAO recommendations implemented within 24 months of a performance audit being presented’ the ANAO seeks advice annually from all relevant entities on progress in implementing recommendations, over a 24 month implementation period. This measure is based on entity self-reporting on implementation of recommendations.

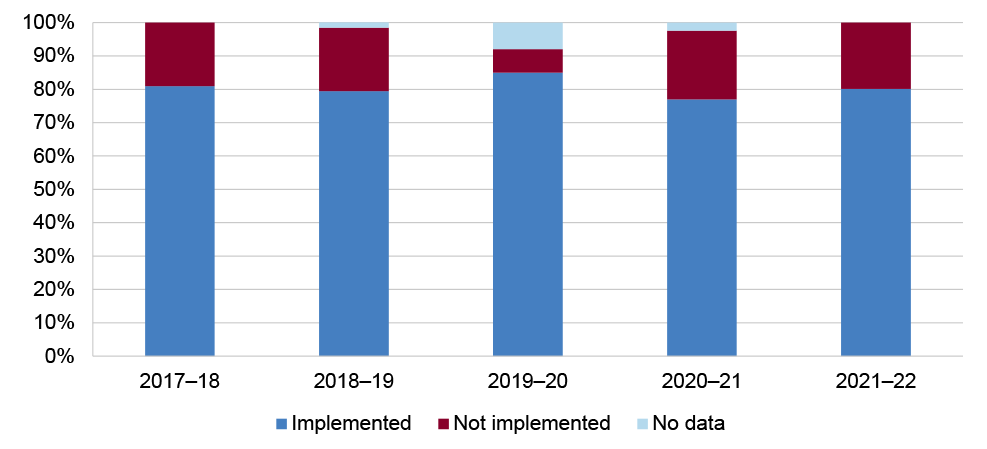

2.49 To determine whether ANAO recommendations have been addressed by entities a full 24 month period is required from the audit cycle when the findings were raised. Figure 2.20 considers the implementation of recommendations from 2017–18 to 2021–22.

Figure 2.20: Implementation of recommendations within 24 months, tabled audits 2017–18 to 2021–22

Source: Australian National Audit Office, ANAO Annual Report 2023–24, ANAO, Canberra, 2024, available from https://www.anao.gov.au/work/annual-report/anao-annual-report-2023-24 [accessed 14 October 2024].

2.50 For audits tabled between 2017–18 to 2021–22, an average of 80 per cent of recommendations were self-reported to be implemented within two years.

2.51 The ANAO undertakes an ongoing program of performance audits on entities’ implementation of parliamentary and ANAO recommendations. These audits have shown that some entities have reported ANAO recommendations as being implemented when the evidence has shown that they have not actually been implemented. These performance audits do not cover all entities, and the results may not be representative of the whole population. The audits undertaken to date have identified that 18 per cent of recommendations that entities had reported as implemented were assessed by the ANAO as not implemented.41

Analysis by portfolio

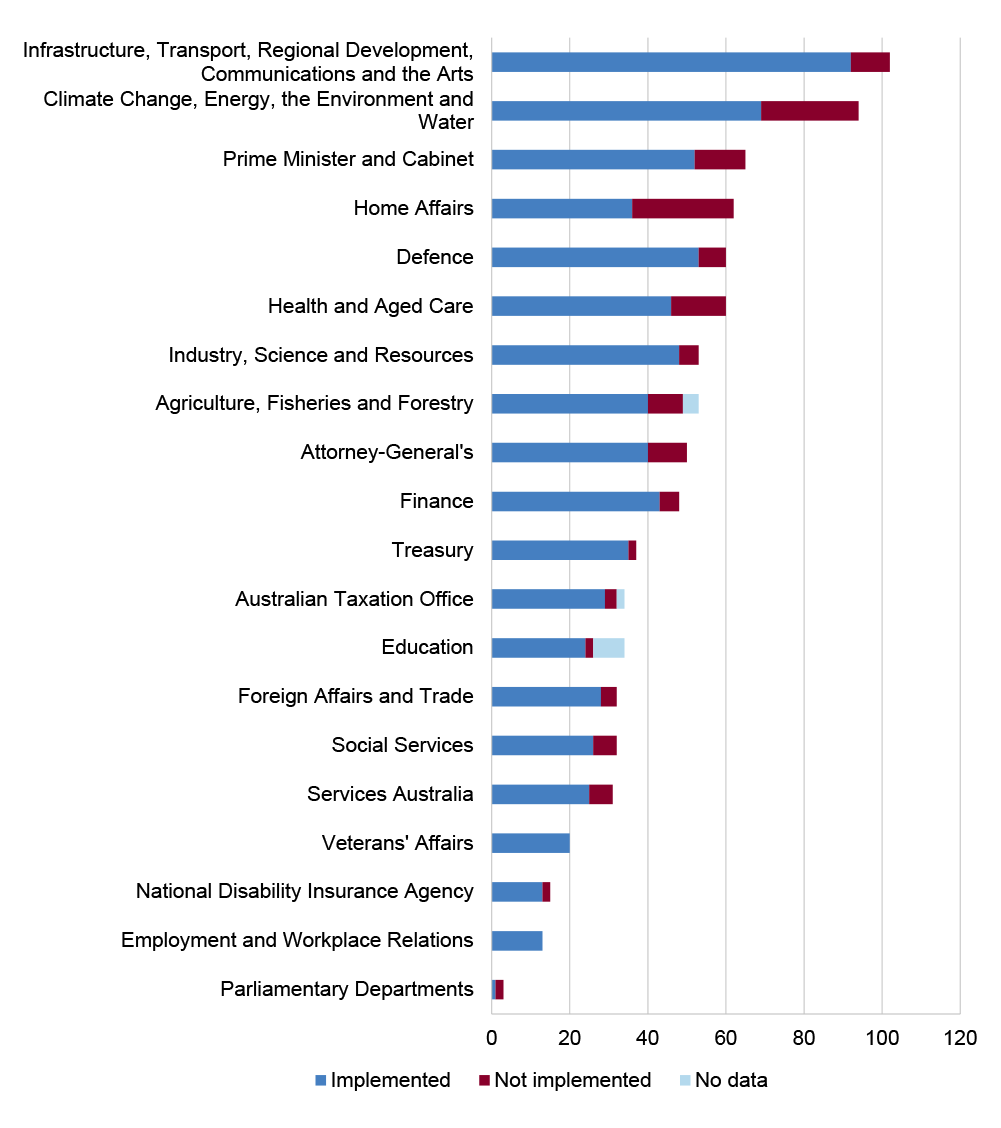

2.52 Figure 2.21 displays the number of recommendations implemented or not implemented, from highest to lowest number of recommendations.

Figure 2.21: Implementation of recommendations by portfolio, tabled audits 2017–18 to 2021–22

Note: Implementation of recommendations are self-reported by entities.

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audits published 2019–20 to 2023–24.

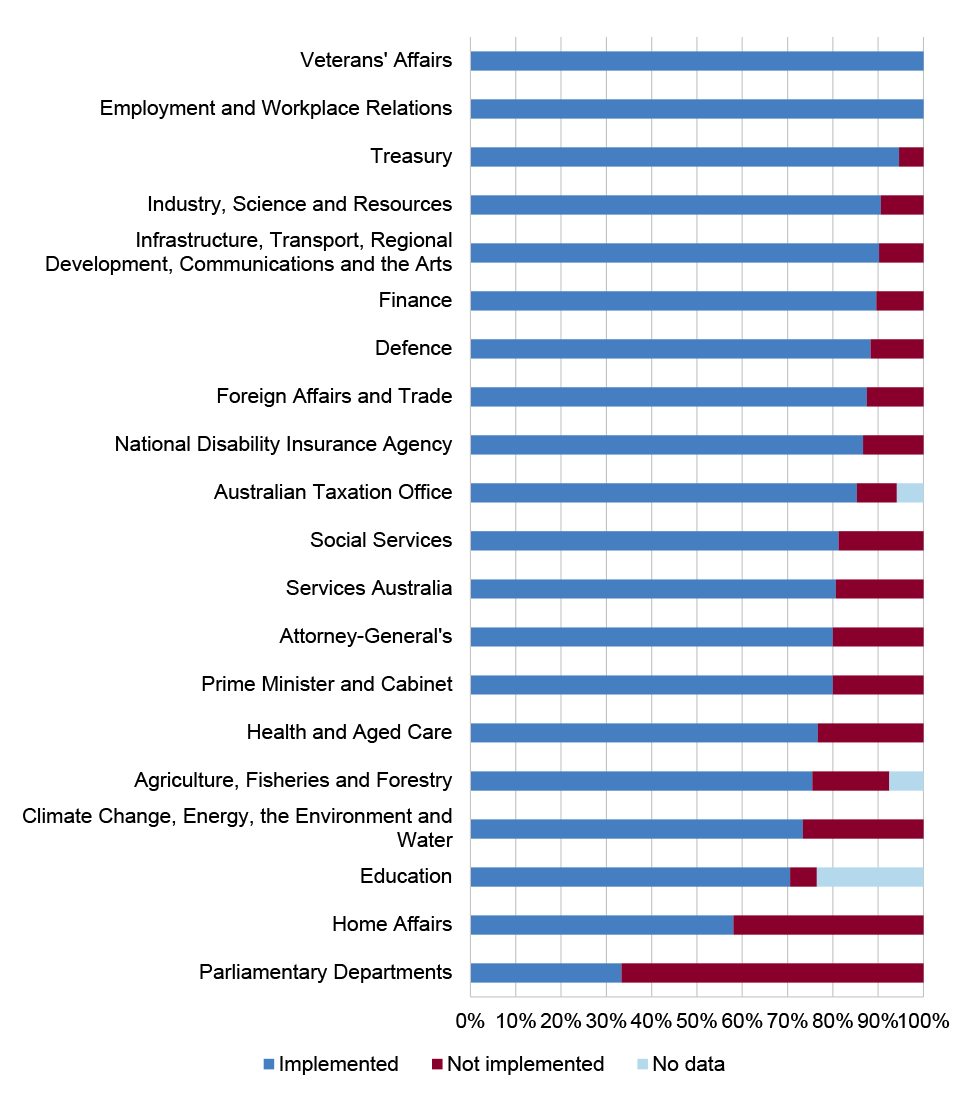

2.53 The Home Affairs portfolio had 26 recommendations (42 per cent, see Figure 2.22) not implemented, the Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water portfolio had 25 recommendations (27 per cent, see Figure 2.22) not implemented. Veterans’ Affairs and the Employment and Workplace Relations portfolio self-reported that they had implemented all recommendations received.

Figure 2.22: Percentage of implementation of recommendations by portfolio, tabled audits 2017–18 to 2021–22

Source: ANAO analysis of performance audits published 2019–20 to 2023–24.

Improvements observed by entities during 2023–24 audits

2.54 Performance audits involve regular engagement between the ANAO and the audited entity. Throughout the audit engagement, the ANAO outlines to the entity the preliminary audit findings, conclusions and potential audit recommendations. This ensures that final recommendations are appropriately targeted and encourages entities to take early remedial action on any identified matters during the course of an audit. Remedial actions entities may take during the audit include: strengthening governance arrangements; initiating reviews; and revising and updating policies or guidelines.

2.55 From 2021–22, performance audit reports included information in an appendix to capture improvements observed by entities during the course of an audit. For 2023–24, 40 of the 45 performance audits (89 per cent) tabled in the Parliament captured observed improvements. The key improvement themes included governance, risk management, administrative processes, and performance reporting and monitoring. Five audits did not identify improvements.42

3. Themes identified from performance audits

Chapter coverage

This chapter provides a summary of themes identified from performance audits completed in 2023–24. It provides guidance for improving public service administration.

Summary

Themes and issues emerging from performance audits in 2023–24 included planning and implementation, evaluation, procurement and contract management, and cyber security. Outcomes from audits relating to compliance with corporate credit cards, and gifts, benefits and hospitality requirements demonstrated the need for well documented and executed policies and procedures, which consider risks and focus on a pro-integrity culture. The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) has made ongoing observations on the need for improvement in record keeping practices.

The ANAO has published audit ‘Insights’ products on risk management, procurement and contract management, grants administration, cyber security and other areas of note to contribute to improved public sector performance. In September 2024, the ANAO published its inaugural quarterly Audit Matters newsletter to inform external audiences of updates on the ANAO’s work and provide insights on what we are seeing in the Australian Government sector.