Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Interim Report on Key Financial Controls of Major Entities

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

This report is the first of two reports each year and focuses on the results of the interim audits, including an assessment of entities’ key internal controls, supporting the 2022–23 financial statements audits. This report examines 27 entities, including all departments of state and a number of major Australian government entities. The majority of entities included in the report are selected on the basis of their contribution to the income, expenses, assets and liabilities of the 2021–22 Consolidated Financial Statements.

Executive summary

1. The ANAO prepares two reports annually that provide insights at a point in time to the financial statements risks, governance arrangements and internal control frameworks of Commonwealth entities, drawing on information collected during our audits. These reports explain how entities’ internal control frameworks are critical to executing an efficient and effective audit and underpin an entity’s capacity to transparently discharge its duties and obligations under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act). Deficiencies identified during ANAO audits, posing a significant or moderate risk to entities’ ability to prepare financial statements free from material misstatements, are reported.

2. This report is the first of the two reports and focuses on the results of the interim audits, including an assessment of entities’ key internal controls, supporting the 2022–23 financial statements audits. This report examines 27 entities, including all departments of state and a number of major Australian government entities. The majority of entities included in the report are selected on the basis of their contribution to the income, expenses, assets and liabilities of the 2022–23 Consolidated Financial Statements (CFS). At the completion of interim audits for the 27 entities included in this report the ANAO noted that key elements of internal control were operating effectively for 12 entities. For the remaining 15 entities, except for particular finding/s outlined in Chapter 3, the key elements of internal control were operating effectively to support the preparation of financial statements that are free from material misstatement.

Summary of audit findings and related issues

Entity internal controls

3. The interim audit phase includes an assessment of the effectiveness of each entity’s internal controls as they relate to the risk of misstatement in the financial statements. At the completion of interim audits for the 27 entities included in this report, the key elements of internal control were assessed as operating effectively for 12 entities. For the remaining 15 entities, the key elements of internal control were operating effectively to support the preparation of financial statements that are free from material misstatement, except for particular finding/s outlined in Chapter 3.

4. An analysis of entity compliance with the Commonwealth’s finance law and a review of entity risk assessment and internal controls relating to procurement has highlighted that entities utilise a variety of policies, procedures and approaches to manage and monitor procurements.

Machinery of Government changes

5. Machinery of Government (MoG) changes implemented in 2022–23 transferred functions and programs between departments. Two departments of state were established and five departments of state were renamed.

6. Analysis of the MoG changes indicated that entities largely followed the principles of the Machinery of Government changes: A guide for entities — November 2021 when implementing MoG changes.

Safeguarding financial information from cyber threats

7. The Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) contains the Essential Eight mitigation strategies including mandatory and recommended controls intended to strengthen cyber resilience and the capacity of government to mitigate cyber threats. Review of entities implementation and compliance with these strategies noted deterioration in reported maturity levels across some Essential Eight mitigation strategies since ANAO’s 2021–22 assessment.

Summary of audit findings

8. A total of 78 findings were reported to the entities included in this report as a result of interim audits, comprising 29 moderate, 47 minor and two legislative findings. This is an overall increase in the number of findings, and a large increase in moderate findings compared to the 2021–22 interim audit results. The 2021–22 interim audit results reported one significant, 14 moderate, 45 minor, and two legislative findings.

9. Sixty-three per cent of all findings and seventy-two per cent of moderate findings relate to the management of IT controls, particularly the management of privileged user access and terminations.

Reporting and auditing frameworks

Summary of developments

10. A revised Australian Auditing Standard ASA 315 Identifying and Assessing the Risks of Material Misstatement became effective for 2022–23 financial statements audits. As a result, changes have been made to the ANAO’s audit methodology.

11. The ANAO Quality Management Framework addresses the requirements of three new and revised Australian Quality Management Standards, which became effective on 15 December 2022. In November 2022, the ANAO finalised its methodology and framework for considering ethics either as part of a broader performance, financial or performance statements audit, or as an audit of an entity’s ethical framework. Audits considering ethics will feature in ANAO audit programs.

12. The ANAO is monitoring national and international developments in sustainability reporting guidance and will continue to contribute to discussions as reporting and assurance standards develop.

Cost of this report

13. The cost to the ANAO of producing this report is approximately $320,000.

1. Interim audit results and other matters

Chapter coverage

This chapter provides:

- an overview of the ANAO’s audit approach to financial statements audits;

- a summary of observations regarding the internal control environments of the entities included in this report;

- observations relating to Machinery of Government changes, compliance with finance law, managing and monitoring procurement, and the safeguarding of financial information from cyber threats; and

- a summary of audit findings identified at the conclusion of the interim audit.

Conclusion

Key to the ANAO’s audit process is our assessment of entities’ internal control frameworks as they apply to financial reporting. An effective internal control framework provides the ANAO with a level of assurance that entities are able to prepare financial statements that are free from material misstatement. At the completion of interim audits for the 27 entities included in this report, we noted that key elements of internal control were operating effectively for 12 entities. For 15 entities, except for particular finding/s outlined in chapter 3, the key elements of internal control were operating effectively to support the preparation of financial statements that are free from material misstatement.

Accountable authorities have duties under Division 2 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) that include: promoting the proper use and management of public resources; and reporting to the Minister on significant issues and activities in the entity. In the context of these obligations and a review of entity internal controls, this report includes an analysis of entity compliance with the Commonwealth’s finance law. The review highlighted that entities utilise a variety of policies, procedures and approaches to manage and monitor procurements.

Analysis of 2022–23 Machinery of Government (MoG) changes indicated that entities largely followed the principles of the Machinery of Government changes: A guide for entities — November 2021 when implementing MoG changes.

The Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) contains the Essential Eight mitigation strategies and recommends controls intended to strengthen cyber resilience and the capacity of government to mitigate cyber threats. Review of entities’ implementation and compliance with these strategies noted deterioration in reported maturity levels across some Essential Eight mitigation strategies since ANAO’s 2021–22 assessment.

A total of 78 findings were reported to the entities included in this report as a result of interim audits, comprising 29 moderate, 47 minor and two legislative findings. This is an overall increase in the number of findings, with a large increase in moderate findings, compared to the 2021–22 interim audit results. The 2021–22 interim audit results reported one significant, 14 moderate, 45 minor, and two legislative findings.

Eighty-three per cent of moderate findings continue to be in the areas of: management of IT controls, particularly the management of privileged users, and accounting and control of non-financial assets. These areas warrant further attention by entity management.

Introduction

1.1 The ANAO publishes an Annual Audit Work Program (AAWP) which reflects the ANAO’s strategy and deliverables for the forward year. The purpose of the AAWP is to inform the Parliament, the public and government sector entities of the ANAO’s planned audit coverage for Australian Government entities by way of financial statements audits, performance audits and other assurance activities.

1.2 The financial statements audit coverage, as outlined in the AAWP, includes presenting two reports to the Parliament addressing the outcomes of the financial statements audits of Australian Government entities and the Consolidated Financial Statements of the Australian Government (CFS). These reports provide Parliament with an independent examination of the financial accounting and reporting of Commonwealth public sector entities.

1.3 This report focuses on the results of the interim audits of 27 entities including an assessment of key internal controls supporting the 2022–23 financial statements. The assessment includes a review of the governance arrangements related to entities’ financial reporting responsibilities and the design and implementation of key internal controls relating to significant business processes. Where the auditor plans to rely upon key controls for assurance that financial statements are free from material misstatement, the controls are tested for operating effectiveness. Testing of controls during the interim audit phase allows us to form a conclusion on the operating effectiveness of those controls for the period up to the date of testing. During the final phase of the 2022–23 financial statements audit, we complete testing over the operating effectiveness of those controls we intend to rely upon, and controls not assessed at interim. The second report presents the final results of the financial statements audits of the CFS and all Australian Government entities.

1.4 The entities included in this report are those entities that contribute significantly to the three sectors of the CFS: the General Government Sector (GGS), Public Non-Financial Corporation (PFNC) sector and Public Financial Corporation (PFC) sector. A listing of these entities is provided in Appendix 1.

1.5 The ANAO conducts its financial statements audits in four phases: planning, interim, final and completion. Figure 1.1 outlines the key elements of each phase.

Figure 1.1: ANAO financial statements audit process

Source: ANAO data.

1.6 A central element of the ANAO’s financial statements audit methodology, and the focus of the planning phase of ANAO audits, is a sound understanding of an entity’s environment and internal controls relevant to assessing the risk of material misstatement in the financial statements. This understanding informs the ANAO’s audit approach, including the reliance that may be placed on entity systems to produce financial statements that are free from material misstatement.

1.7 In accordance with generally accepted auditing practice, the ANAO accepts a low level of risk that an audit will fail to detect the financial statements are materially misstated. This low level of risk is accepted because it is too costly to perform an audit that is predicated on no level of risk. An understanding of the entity, its environment and its controls helps the ANAO design the required work and respond to risks that bear on financial reporting. The key areas of financial statements risks identified through this planning approach are discussed in chapter 3 for each entity included in this report.

1.8 A key component of understanding the entity and its environment is to understand the governance arrangements established by its accountable authority.1 Accountable authorities of all Commonwealth entities and companies subject to the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) are required to govern their entity in a way that promotes the proper use and management of public resources, the achievement of the purposes of the entity and the entity’s financial sustainability.

1.9 The development and implementation of effective corporate governance arrangements and internal controls should be designed to meet the individual circumstances of each entity. These processes also assist in the orderly and efficient conduct of the entity’s business and compliance with applicable legislative requirements, including the preparation of annual financial statements that present fairly the entity’s financial position, financial performance and cash flows.

Understanding the entity

1.10 The ANAO uses the framework in the Australian Auditing Standards (ASA) 315 Identifying and Assessing the Risks of Material Misstatement through Understanding the Entity and its Environment to consider the impact of different elements of an entity’s internal controls that support the preparation of financial statements. This approach provides a basis for designing and implementing the audit work program that reflects the ANAO’s assessment of the risk of material misstatement. Deficiencies in the internal control framework increase the requirement of the ANAO to perform additional audit work in the final audit phase. Figure 1.2 outlines these elements.

Figure 1.2: Elements of entity internal controls

Source: ASA 315 Identifying and assessing the risk of material misstatement through understanding the entity and its environment, paragraphs 21–26.

1.11 This chapter discusses each of these elements and outlines observations based on the ANAO’s review of aspects of each entity’s internal controls, relevant to the risk of material misstatement to the financial statements, including the detailed results of the interim audits.

1.12 At the completion of the interim audits for the 27 entities included in this report, the ANAO noted that key elements of internal control were operating effectively for 12 entities. The remaining 15 entities were assessed as having internal controls that were operating effectively except for a particular finding which is outlined in chapter three.2

1.13 The key elements of internal control for the full financial year will be assessed in conjunction with additional audit testing during the 2022–23 final audits.

Control environment

1.14 The PGPA Act sets out the requirements to establish and maintain systems relating to risk and control. Division 2, section 16 of the PGPA Act states that:

The accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity must establish and maintain:

a) an appropriate system of risk oversight and management for the entity; and

b) an appropriate system of internal control for the entity;

including by implementing measures directed at ensuring officials of the entity comply with finance law.3,4

1.15 An effective control environment is underpinned by a fit-for-purpose governance structure. Indicators of an effective governance structure include whether management has established frameworks and processes that promote positive attitudes, awareness and actions concerning the entity’s internal controls and their importance in the entity. The main elements reviewed included: governance structures relevant to the preparation of the financial statements; audit committee and assurance arrangements; systems of authorisation; and processes for recording financial transactions.

1.16 All entities included in this report have established audit committees that meet the minimum requirements for audit committees as outlined in PGPA Rule section 175 or section 286. All audit committees consist of a majority of members which were assessed by the entity to be independent. The Chair of the audit committee for all entities is an independent member. All entities have an audit committee charter that is consistent with their obligations under subsection 17(2) of the PGPA Rule.

1.17 Of the 27 entities included in this report, 26 entities have established executive management committees and/or sub-committees that meet at least monthly, which support financial decision making at the strategic and operational levels.7 The Department of Home Affairs’ executive management committee meets quarterly and as directed by the Chair. Consideration of financial reporting was included on the agendas of 26 entities’ executive committees. The Department of Defence reports financial information directly to its Secretary and Chief of Defence. The financial information provided to the entities’ executives was supplemented by non-financial operational information for all entities.

1.18 Clear lines of accountability and reporting are important in establishing a strong internal control environment for the purposes of preparing the financial statements. The involvement of those charged with governance is an important element of these structures. Just as important is ensuring that staff at all levels understand their own role in the control framework. This can be achieved through the issuance of accountable authority instructions and delegation instruments. All entities have established accountable authority instructions and delegations reflecting current business arrangements.

Risk assessment processes

1.19 Section 16 of the PGPA Act sets out an accountable authority’s responsibilities regarding the establishment of appropriate risk oversight and management in an entity. An understanding of an entity’s process to identify and manage risk is essential to an effective and efficient financial statements audit. A review of this process is done to assist the ANAO to understand how entities identify and manage risks relating to financial statements and assess the risk of material misstatement to an entity’s financial statements.

1.20 All entities included in this report have a process to develop and update risk management plans at the organisational and strategic risk levels. In addition, each entity has developed processes for the identification and notification of risks relevant to financial statements preparation either as part of the overall risk management plan, or through a targeted risk identification exercise. The monitoring of risks, and the entities’ implementation of risk management strategies, was typically assigned to either an executive committee and/or the audit committee.

Monitoring of controls

1.21 Entities undertake many types of activities as part of their monitoring of control processes, including external reviews, self-assessment processes, post-implementation reviews and internal audits. The level of review of these activities by the ANAO is determined through a risk assessment approach that takes into consideration the nature, extent and timing of each activity and the activities’ application to the preparation of the financial statements. All entities included in this report have an ongoing process for monitoring and evaluating internal controls.

Internal audit

1.22 As part of the financial statements audit coverage, internal audit is reviewed to gain an understanding of its role and activities in the entity. Where an internal audit function has been established it can play an important role in providing assurance to the accountable authority that the internal control framework is operating effectively. Entities are encouraged to identify opportunities to leverage internal audit coverage as a means of providing increased assurance to accountable authorities to support their opinion on the entity’s financial statements. All entities included in this report have established an effective internal audit function.

1.23 The extent to which the work of internal audit may be able to be used, in a constructive and complementary manner, varies between entities and is more likely to occur where internal audit work is focused on financial controls and legislative compliance. The ANAO is expecting to rely upon the work of internal audit for three entities in the current year.8 If the ANAO is anticipating to use the work of internal audit, in accordance with ASA 610 Using the Work of Internal Auditors, the ANAO is required to assess whether the internal audit function has: appropriate organisational status; relevant policies and procedures to support its objectivity; an appropriate level of competence; and whether it applies a systematic and disciplined approach in the execution of its work including quality control.

1.24 When it is determined that the work of internal audit can be used to support an effective audit approach, additional work is performed to confirm its adequacy to support the external audit. This will include confirmation that the scope of the work is appropriate, that there is sufficient evidence to support the conclusions drawn and selected re-performance of internal audit’s testing.

Reporting relating to compliance with finance law

1.25 The introduction of the PGPA Act resulted in a move from a compliance-based approach to a principle-based framework for Commonwealth entities. To promote the safe custody and proper use of public resources whilst reducing red tape, a greater emphasis is placed on the robustness of an entity’s self-assessment processes, strong governance structures and internal control frameworks to identify risks. A practical example of this is an entity’s requirement to report on compliance with finance law.9

1.26 From 2015–16, the Department of Finance changed the compliance reporting process to require entities to report only significant non-compliance with the finance law to both the Minister for Finance and the responsible Minister. To support the change in requirements, the Department of Finance issued guidance in relation to reporting of significant non-compliance through the Resource Management Guide 214 Notification of significant non-compliance with finance law (PGPA Act, section 19) (RMG 214). The guide outlines factors which may be considered when determining whether significant non-compliance occurred including:

- failure to comply with the duties of accountable authorities (PGPA Act sections 15 to 19);

- serious breaches of the general duties of officials (PGPA Act sections 25 to 29) including any fraudulent activity by officials;

- systemic issues reflecting internal control failings or high-volume instances of non-compliance; and

- non-compliance issues that are likely to impact on the entity’s financial sustainability.

1.27 RMG 214 notes that the accountable authority should consider their entity’s environment when determining whether instances of non-compliance are significant. In May 2019, RMG 214 was updated with additional guidance in the form of case studies. The case studies highlight the need for entities to consider the number of non-compliance issues in the context of the number of times the function had occurred within the entity. For example, comparing the number of breaches relating to incorrect reporting of contracts on AusTender compared to the number of contracts executed in that year. As part of the interim audits the ANAO considered entities’ application of RMG 214.10

1.28 In addition to notifying the relevant Minister of any significant issues which occur, entities must also report any significant non-compliance in their annual report in line with the PGPA Rule subsection 17AG. The following three entities reported significant non-compliance in the 2021–22 annual reports:

- The Department of Home Affairs reported one significant non-compliance11 relating to misuse of a Commonwealth credit card and falsification of documents. The matter was finalised in November 2021 and related to transactions that occurred between July 2016 and June 2017. The department has limited cash withdrawal access for departmental Commonwealth credit card holders and implemented a Credit Card Compliance Monitoring Program, and the department also continues to require mandatory training for cardholders and review of monthly statements by supervisors.

- The Department of Industry, Science and Resources reported one significant non-compliance12 relating to compliance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules. Corrective action is being undertaken by the department to ensure that it demonstrates best practice in management of probity in procurements and grants.

- The Department of Defence reported 14 instances of significant non-compliance13. Five cases related to credit card non-compliance, primarily related to credit card misuse; one case related to deception; eight cases related to entitlements. The department has undertaken remedial actions ranging from administrative sanctions or disciplinary action to criminal prosecutions and has undertaken remedial action under the Defence Force Discipline Act 1982.

1.29 Entities undertake a range of activities to identify instances of non-compliance and support their assessment of whether identified breaches meet the definition of significant. These activities include self-reporting, internal assurance activities, and questionnaires completed by officers holding delegations. Through these processes, in 2021–22 entities included in this report identified a total of 4,873 instances of non-compliance.14

1.30 The Department of Home Affairs also advised additional non-compliance with section 23 of the PGPA Act in the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS) contract centre, when assigning interpreting jobs to interpreters.15 Subsequent legal advice concluded that the operators engaged as contractors by TIS were not prescribed as Officials under the PGPA Act and did not hold section 23 delegations. The department advised that delegations and Authority to Act instruments have been implemented to allow the exercise of section 23 delegations relating to TIS operators.

1.31 Figure 1.3 provides the ANAO analysis of instances of non-compliance by category as identified by entities in 2021–22.

Figure 1.3: Non-compliance identified by entities in 2021–22

Source: ANAO analysis of data provided by entities.

1.32 Further details of the areas of non-compliance are detailed below.

- The following three entities identified the highest levels of non-compliance with the Commonwealth Procurement Rules: the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (671 instances); the Department of Home Affairs (465 instances); and the Department of Industry, Science and Resources (200 instances).

- Breaches of section 23 of the PGPA Act include failure to obtain appropriate delegate approval prior to entering into contracts and exceeding a delegate’s approval. The following three entities identified the highest levels of non-compliance in this area; the Department of Defence (604 instances); the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (57 instances); and the Department of Home Affairs (56 instances).

- Eighty-one per cent of instances of non-compliance with the PGPA Act, excluding section 23, related to breaches of Duty of Care and Diligence under section 25.

- The non-compliance with the PGPA Rule relates to failure to document the approvals to enter into arrangements under section 23 of the PGPA Act.

1.33 RMG 214 identifies that while a matter may not be sufficiently significant to report to the responsible Minister and/or the Minister for Finance, entities are encouraged to review all incidents of non-compliance as these could indicate internal control problems or the beginning of more systemic issues. The collation and reporting of non-compliance allows audit committees and accountable authorities to assess emerging risks and determine training requirements or changes to procedures required to address trends.

Procurement

1.34 The majority of reported breaches of finance law continues to be in relation to procurement. For this report, the ANAO has considered procurement practices including risk assessments, policies and training of the 27 entities included in this report. Results are included in the following section.

1.35 Under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), responsibility for the proper use of public resources, including procurement, rests with the accountable authority of each entity. This responsibility includes developing procurement policies, procedures and systems and the conduct of individual procurements. The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (PGPA Rule), associated instruments, and policies, establish the requirements and procedures necessary to give effect to the governance, performance and accountability matters as covered by the PGPA Act

1.36 The Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) are the core of the Australian Government procurement framework. The framework also includes guidance developed by the Department of Finance, Resource Management Guides that simplify and streamline processes and other tools to assist entities in ensuring procurement practices are robust. An appropriate system of risk oversight and management in addition to internal controls is key to ensuring entities are able to comply with relevant requirements.

1.37 Of the entities included in this report, three entities16 have identified strategic risks that directly relate to procurement and 1517 entities have determined that there is an entity level risk or risks that have an indirect relationship to procurement. The strategic risks for the remaining nine entities do not relate to procurement.

1.38 All entities have policies and procedures in place to assist staff in undertaking procurements and procurement is included as a topic in the internal audit plan for nine18 entities. Policies and procedures provided by entities include:

- formal procurement policies and guides, Accountable Authority instructions and procurement toolkits supplemented with practical guidance materials and templates and contract management flowcharts;

- procurement internet pages that include guidance; and

- procurement specific IT applications.

1.39 Entities have also implemented methods to support staff in completing procurements that are considered high risk. These include:

- more detailed risk assessments;

- direct support from a central procurement team;

- obtaining legal advice; and

- obtaining external probity and/or commercial advice

1.40 As outlined in Figure 1.3 above, entities reported non-compliance with procurement rules in 2021–22. A key process in mitigating the risk of non-compliance is the provision of regular training to staff on the requirements of managing and undertaking procurements.

1.41 The following table identifies the 27 entities included in this report and outlines the total number and value of committed procurements reported to commence in 2021–22. The table also includes information on the number of staff in the entity’s procurement function and training requirements.

Table 1.1: The number and committed value of contracts (and amendments to existing contracts) reported to start in 2021–22 financial year for entities included in this report

|

Entitya |

Total number of contracts |

Total value of contracts $’000 |

Number of staff in centralised procurement team |

Mandatory procurement training |

|

Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry |

5,136 |

1,263,348 |

19 |

Yesb |

|

Attorney-General’s Department |

1,234 |

179,356 |

No centralised procurement teamd |

No |

|

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water |

1,420 |

365,736 |

22 |

Yesc |

|

Snowy Hydro Limitedf |

– |

– |

7 |

No |

|

Department of Defence |

33,386 |

43,397,291 |

No centralised procurement teamd |

No |

|

Department of Veterans’ Affairs |

2,670 |

508,743 |

7 |

No |

|

Department of Education |

1,320 |

481,523 |

6 |

No |

|

Department of Employment and Workplace Relations |

2,595 |

965,036 |

6 |

No |

|

Department of Finance |

1,200 |

1,560,380 |

5 |

No |

|

Future Fund Management Agency |

503 |

111,385 |

3 |

Yesb |

|

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade |

1,743 |

982,794 |

39 |

Yese |

|

Department of Health and Aged Care |

4,856 |

4,298,388 |

8 |

No |

|

Department of Home Affairs |

2,702 |

3,863,664 |

24 |

No |

|

Department of Industry, Science and Resources |

2,230 |

876,097 |

15 |

No |

|

Department of Infrastructure, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts |

1,734 |

687,547 |

6 |

No |

|

Australian Postal Corporationf |

– |

– |

16 |

Yesc |

|

NBN Co. Limitedf |

– |

– |

66 |

No |

|

Department of Parliamentary Services |

548 |

140,657 |

18 |

No |

|

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet |

664 |

114,948 |

12 |

No |

|

National Indigenous Australians Agency |

614 |

123,247 |

6 |

No |

|

Department of Social Services |

886 |

520,065 |

5 |

No |

|

National Disability Insurance Agencyf |

564 |

38,382 |

126 |

Yesb |

|

Services Australia |

3,819 |

2,864,475 |

38 |

No |

|

Department of the Treasury |

775 |

197,650 |

6 |

Yesb |

|

Australian Office of Financial Management |

30 |

22,927 |

No centralised procurement team |

No |

|

Australian Taxation Office |

1,953 |

1,877,830 |

48 |

No |

|

Reserve Bank of Australia |

20 |

335,000 |

13 |

Yesc |

Note a: Where a MoG has resulted in a change to an entity name without a change to the entity’s Australian Business Number (ABN), any contracts published under the previous entity name have been automatically updated to the new entity name as outlined in paragraph 2.6 of Auditor-General Report No. 11 2022–23 Australian Government Procurement Contract Reporting – 2022 Update.

Note b: Training is mandatory for all staff.

Note c: Training is mandatory for relevant staff including those that have purchasing authority or may exercise a delegation.

Note d: Defence’s Commercial Division manages the Defence Commercial Framework and provides commercial advice and procurement services. The Attorney-General’s Department has a central team that provides policy advice for procurements.

Note e: Training is mandatory for officers prior to being posted offshore.

Note f: Corporate Commonwealth entities that are not prescribed to comply with the reporting requirements of the CPRs, including reporting procurements on AusTender as outlined in paragraph 2.3 of Auditor-General Report No. 11 2022–23 Australian Government Procurement Contract Reporting – 2022 Update. None of the 18 Commonwealth companies are prescribed to comply with the CPRs.

Source: ANAO analysis of AusTender data for contracts and amendments, reported to start between 1 July 2021 and 30 June 2022, extracted and provided by the Department of Finance in September 2022.

1.42 Where training is mandatory, training is required to be completed annually for four19 entities, every two years for two20 entities and every three years or once per posting for two21 entities. Effective training to support the development of skills is key to ensuring entities appropriately perform their duties related to procurement.

1.43 The assessment has highlighted that entities utilise a variety of policies, procedures and approaches to manage and monitor procurements to assist the accountable authority in discharging their duties and reducing instances of non-compliance.

Machinery of Government changes

1.44 A Machinery of Government (MoG) change occurs following a Government decision to change the way Commonwealth responsibilities are managed. MoG changes can involve the movement of functions, resources and staff from one agency to another. When implementing MoG changes entities are to apply change management arrangements in a timely and effective manner, ensuring continuity of Government business.22

1.45 Where MoG changes affect areas such as governance arrangements, appropriations, IT systems, internal controls and financial reporting, the ANAO takes the changes into account in developing its audit approach as part of the annual financial statement audits of Australian Government entities.

Scale of 2022–23 MoG changes

1.46 MoG changes implemented in 2022–23 transferred functions and programs between departments. As part of these changes, two departments of state were established: the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water and the Department of Employment and Workplace Relations. Additionally, five departments of state were renamed.23

1.47 Of the 27 entities included in this report, 12 were impacted by MoG changes in 2022–23.24 MoG changes impacting these entities are summarised in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: Functions transferred in 2022–23 MoG changes

|

Function(s) transferred |

Transferring entity |

Receiving entity |

|

Law enforcement and cybercrime |

Department of Home Affairs |

Attorney-General’s Department |

|

Copyright |

Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communicationsa |

|

|

National child safety and open government partnership |

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet |

|

|

Environment and water |

Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environmenta |

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Waterb |

|

Climate change and energy |

Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resourcesa |

|

|

Water (infrastructure) |

Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communicationsa |

|

|

Emergency management |

Home Affairs |

National Emergency Management Authorityc |

|

Industrial relations |

Attorney-General’s Department |

Department of Employment and Workplace Relationsb |

|

Employment and vocational training |

Department of Employment, Skills and Educationa |

|

|

Pacific Australia Labour Mobility (PALM) scheme |

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade |

|

|

Deregulation and data and digital policy |

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet |

Department of Finance |

|

Supply chain resilience and digital technologies |

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet |

Department of Industry, Science and Resources |

|

Domestic, family and sexual violence |

Department of Social Services |

Domestic, Family and Sexual Violence Commissionc |

Note a: The transferring entity name in the table reflects the arrangements prior to the Machinery of Government changes effective 1 July 2022.

Note b: Entity was established 1 July 2022.

Note c: Entity is non-material (not in the scope of this report).

Source: ANAO data.

1.48 Transfers of employees between entities impacted by MoG changes are made through a determination under section 72 of the Public Service Act 1999. The transfers of ongoing APS employees between the entities included in this report are summarized in Table 1.3.

Table 1.3: Staff transfers between entities included in this report (from 2022–23 MoG changes)

|

Entity |

Ongoing employees transferred out |

Ongoing employees transferred in |

|

Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry |

2,220 |

– |

|

Attorney-General’s Department |

333 |

201 |

|

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Watera |

– |

2,927 |

|

Department of Education |

2,636 |

– |

|

Department of Employment and Workplace Relationsa |

– |

3,004 |

|

Department of Finance |

– |

72 |

|

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade |

46 |

– |

|

Department of Home Affairs |

150 |

– |

|

Department of Industry, Science and Resources |

667 |

31 |

|

Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts |

37 |

– |

|

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet |

146 |

– |

|

Department of Social Services |

– |

– |

|

Total |

6,235 |

6,235 |

Note a: Entity was established 1 July 2022.

Source: Public Service (Machinery of Government changes) Section 72 Determinations (including amendments) between entities included in this report. This includes Determinations signed by the former Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment and the former Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources in June 2022.

1.49 In addition to the transfer of staff, appropriations were transferred between entities through determinations made under section 75 of the PGPA Act. The total values of section 75 transfers in 2022–23 relating to entities included in this report are listed in Table 1.4.

Table 1.4: Section 75 transfers from 2022–23 MoG changesa

|

Entity |

Departmental appropriations transferred in ($m) |

Departmental appropriations transferred out ($m) |

Administered appropriations transferred in ($m) |

Administered appropriations transferred out ($m) |

|

Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry |

0.4 |

126.2 |

– |

320.3 |

|

Attorney-General’s Department |

26.7 |

24.1 |

11.8 |

16.7 |

|

Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water |

172.1 |

– |

2,209.2 |

– |

|

Department of Education |

– |

257.6 |

– |

2,061.6 |

|

Department of Employment and Workplace Relations |

288.9 |

– |

2,094.2 |

– |

|

Department of Finance |

10.8 |

– |

– |

0.1 |

|

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade |

– |

7.5 |

– |

14.7 |

|

Department of Home Affairs |

– |

26.0 |

– |

24.6 |

|

Department of Industry, Science and Resources |

1.2 |

39.9 |

– |

1,879.4 |

|

Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts |

– |

6.5 |

– |

8.7 |

|

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet |

– |

22.4 |

– |

2.3 |

|

Department of Social Services |

– |

3.5 |

– |

– |

Note a: Section 75 transfers listed in this table include appropriation transfers to non-material entities (not within the scope of this report) in line with functions transferred as a result of 2022–23 in MoG changes.

Source: Determinations made under section 75 of the PGPA Act relating to transfer of 2022–23 appropriations.

Implementing MoG changes

1.50 Implementing MoG changes can involve complexity in managing a range of issues. These include: reaching agreement on the staff and appropriations to be transferred; establishing communication mechanisms with both ‘gaining’ and ‘losing’ staff; connecting gaining staff to existing IT networks and disconnecting transferred staff from IT systems; arranging accommodation requirements for staff being transferred; and negotiating the most effective way to maintain the delivery of services in both the short and longer term, particularly arrangements for the processing of employee entitlements and program payments.

1.51 The Machinery of Government changes: A guide for entities — November 2021 (the Guide), jointly issued by the Australian Public Service Commission and the Department of Finance outlines a set of protocols for entities to observe when implementing changes resulting from a MoG. The principles are:

- taking a whole-of-government approach;

- constructive and open communication with employees; and

- accountability and compliance with legislation and policy.

1.52 The Guide outlines that where a completion date is not specified in relation to a MoG, entities are expected to complete changes within 13 weeks from the date of effect.25 Agency heads are responsible for meeting this deadline and for implementing MoG changes in accordance with the principles.

1.53 Due diligence and change management underpin an effective MoG. The Guide outlines that it is good practice for entities to start MoG planning as early as possible.26 As soon as it becomes clear that a MoG change will occur, affected entities are expected to:

- commence planning activities;

- establish a cross-entity, multi-disciplinary steering committee to oversee implementation;

- consider the appointment of an independent third party to facilitate and advise on the process;

- prepare for an immediate and thorough due diligence exercise; and

- develop a communications strategy to keep employees informed.

1.54 The extent of actions will depend on the size and complexity of the MoG change. Not all actions may be required for entities, depending on the scale of the MoG change.

Observations

1.55 A steering committee appointed to oversee the implementation of MoG changes provides a clear point of contact for the escalation of any issues which may arise. In 2022–23, a steering or implementation committee was appointed by 10 of the 12 entities impacted by MoG changes to manage the MoG process.27 No steering or implementation committee was appointed in two entities that assessed their MoG changes as non-complex and low risk.

1.56 Entities should appoint an independent advisor to manage the process of information exchange between entities where MoG changes are large, sensitive or complex.28 Three entities advised that they used an independent advisor in implementing 2022–23 MoG changes: the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry; the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water; and the Department of Industry, Science and Resources. The independent advisor was used to assist negotiations, help resolve issues and provide independent advice to the secretaries.

1.57 The Guide provides that transferring entities are to provide receiving entities with due diligence information within 10 business days of the announcement of the MoG.29 For due diligence, receiving entities should also establish measures of success for the implementation of the MoG and review any materials prepared during previous MoG changes to assist with planning.30 Of the 12 entities impacted by MoG changes, 10 advised that they undertook a due diligence assessment in relation to the MoG.31 The two entities that did not document a formal due diligence assessment assessed the impact of MoG changes as low risk as the changes involved the transfer of a low numbers of employees.

Implementing MoG changes in a timely manner

1.58 A MoG change must be implemented in a timely manner to ensure continuity of Government business. The Guide provides that where a completion date is not specified in relation to a MoG, entities are expected to complete changes within 13 weeks from the date of effect.32

1.59 Of the 12 entities impacted by MoG changes, eight entities did not complete changes within the 13-week timeframe outlined in the Guide: the Attorney-General’s Department, the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry; the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water; the Department of Education; the Department of Employment and Workplace Relations; the Department of Home Affairs; the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts; and the Department of Social Services.

Risk management of MoG changes

1.60 The Guide outlines that the application of a risk management approach relating to the impact of the MoG change on an entity would assist in avoiding delays in negotiations.33

1.61 Performing a risk assessment assists entities in identifying high risk areas which require escalation early to prevent delays to the implementation of MoG changes, for both transferring and receiving entities. Of the 12 entities impacted by MoG changes in 2022–23, eight entities advised that they performed a formal risk assessment in relation to the overall MoG.34 Four of the twelve entities impacted by MoG changes in 2022–23 advised that they performed an assessment of risks that could impact the financial statements preparation processes. Although this is not a specific requirement in Guide, MoG changes may pose a risk to the timely preparation of complete and accurate financial statements. Performing an analysis of financial statements risks may be useful for entities in future periods.

Conclusion and audit findings relating to implementation of MoG changes

1.62 The information included in the Guide provides entities with a set of principles to follow when they are subject to MoG changes. Best practice would include entities applying the principles of the Guide whether they are the losing agency or the gaining agency. Performing a due diligence review and undertaking detailed risk assessments, from an operational and financial statements perspective, assists entities to identify any new risks that could impact on the timely preparation of complete and accurate financial statements.

1.63 As a result of the interim audit, findings relating to MoG changes were reported to the Department of Education and the Department of Employment and Workplace Relations.35 These findings highlight weaknesses in relation to:

- the configuration of financial and HR systems;

- delays in finalisation of memoranda of understanding with service providers;36

- no established reconciliation processes for appropriation transactions; and

- failure to provide and validate existing employee numbers and movements during the year.

1.64 While findings were reported to two entities, the majority of entities largely complied with the principles of the Guide when implementing the MoG changes in 2022–23.

Safeguarding information from cyber threats

1.65 The Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) requires non-corporate Commonwealth entities (NCE) to consider and implement the Australian Signals Directorate’s (ASD) Essential Eight mitigation strategies (Essential Eight).37 The initial requirements were defined in 2013 and are now specified in PSPF Policy 10, “Safeguarding information from cyber threats” (Policy 10).38 The Essential Eight is considered the baseline for cyber resilience within the Australian Government and provides advice on measures that entities can implement to mitigate cyber threats.39

1.66 Policy 10 requires each non-corporate Commonwealth entity (NCE) to:

- implement the following Australian Signals Directorate (ASD) Strategies to Mitigate Cyber Security Incidents:40

- consider which of the remaining mitigation Strategies from the Strategies to Mitigate Cyber Security Incidents48 need to be implemented to protect the entity.49

1.67 Since 2013, the ANAO has conducted a series of performance audits focussed on assessing entities’ implementation of the PSPF cyber security requirements. These performance audits continue to identify low levels of compliance with mandatory PSPF cyber security requirements and concerns in annual self-assessments by entities. The ANAO has reported its concern that there is no evidence through the series of audits that the regulatory framework had driven sufficient improvement in entities mitigating their cyber security risks since 2013.

1.68 In 2022–23, the ANAO performed a review of the 2021–22 Policy 10 annual self-assessment as part of its assurance audit program of financial statements. This review focused on the protection of information relevant to the preparation of financial statements, specifically the Financial Management Information System (FMIS) and Human Resource Management Information Systems (HRMIS). Twenty of the 27 entities included in this report are required to report annually against the Policy 10 requirements.50 The review was undertaken to assess the evidence supporting the self-assessment and reporting, and to identify cyber security risks that may impact on the preparation of financial statements. The review was based on the October 2020 Policy 10 requirements as these are the requirements that entities were required to implement for the majority of the 2021–22 reporting period.51 The review consisted of analysis of policy and procedural documentation, testing of some Essential Eight mitigation strategies specific to the FMIS and HRMIS, review of results of sprint assessments and meetings with entity personnel.

1.69 The ANAO noted deterioration in reported maturity levels across some Essential Eight mitigation strategies since ANAO’s 2021–22 assessment, particularly with ‘Restricting Administrative Privileges’ and ‘Macro Settings’. Figure 1.4 shows ANAO’s analysis of reported maturity levels for each Essential Eight mitigation strategy between 2019–20 and 2022–23. The Essential Eight mitigation strategies within the shaded area of represent the mitigation strategies that were mandatory during the majority of the 2021–22 reporting period.

Figure 1.4: Reported Compliance with the PSPF Policy 10 Requirements

Source: ANAO data.

1.70 Seven entities reported improvements in Essential Eight maturity levels across several of the Essential Eight mitigation strategies. Although these entities reported improvements, only two of the seven entities had reported meeting all Policy 10 requirements. The other five entities, similar to the majority of the NCEs, were still progressing their development of the Policy 10 mitigation strategies.

1.71 Seven entities reported lower maturity since last year’s assessment. The lower maturity resulted from changes in Policy 10 requirements. Several NCEs reported that the complexity of the changes in Policy 10 requirements has required them to adjust their cyber security uplift programs, resulting in some delays in implementation. Thirteen of the 20 entities reviewed engaged third parties, such as the Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC), to assist with their assessments and implementation of security controls. Although some entities commented on the complexity of changes, most entities were still planning on achieving ASD’s Maturity Level Three for the Essential Eight mitigation strategies.

1.72 The ANAO found the reported maturity levels for most entities were still significantly below the Policy 10 requirements. Of the 20 entities assessed, two had self-assessed as achieving a Managing maturity level. Both entities were able to demonstrate evidence to support the self-assessments as required by the PSPF.

1.73 The lowest level of compliance was with the ‘Macro Settings’ and ‘User Application Hardening’ controls. Although entities had plans to improve ‘Macro Settings’ and ‘User Application Hardening’ controls, as at June 2022 the majority of entities were still not achieving a Managing maturity level. The number of applications in entities’ systems and identifying all applicable hardening controls for specific applications continues to be the key issue with implementing this mitigation strategy. Some entities chose to implement hardening controls for some applications and are implementing other mitigation strategies to address the related cyber threats for those applications that do not have hardening controls.

1.74 ‘Macro Settings’ was reported to be difficult as users continue to rely heavily on macros to perform business activities. Entities continue to differ in their maturity of addressing the associated risks, with some entities reporting difficulties with monitoring the use of macros in their environments. Entities advised that the deterioration in reported maturity levels since last year was due to challenges with fully integrating the changes in Policy 10 requirements into business practices.

1.75 Only six of the 20 entities reviewed had reported achieving the ‘Restricting Administrative Privileges’ requirements. Most entities that reported not achieving the requirements had reported the reduction in maturity level being due to the changes in the Policy 10 requirements. The ANAO identified weaknesses in managing privileged users in two of the six entities that had reported achieving the requirements. The weaknesses related to monitoring privileged user activities across FMIS and HRMIS applications and databases. The ANAO noted that the entities’ self-assessments did not focus on the FMIS and HRMIS applications, but on the systems hosting these applications.

1.76 The PSPF requires entities to identify and protect people, information and assets that are critical to the ongoing operation of their core business.52 Most entities did not view the FMIS and HRMIS applications and financial information as separate critical assets to their computer networks. Those entities conducted their self-assessment at a system or environment level and did not assess the controls required to minimise cyber risks to their FMIS or HRMIS applications.

1.77 Entities which access FMIS and HRMIS applications as part of Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) arrangements reported relying on documentation developed as part of the decision to authorise the system to operate. This documentation may not have been updated in the current period. The PSPF requires this documentation to be developed on new information and communications technology (ICT) systems or when implementing improvements to existing systems.53

1.78 Ten of the 20 entities reviewed had information asset registers that identified critical and high-priority systems and information. Five of the 10 entities had specified the FMIS and HRMIS as critical or high-priority information assets. Entities that had not implemented an information asset register used their business continuity, disaster recovery and risk management plans as the basis for prioritising systems and information. Entities use these mechanisms along with their broader enterprise strategies and objectives to help determine investment in cyber security. Most entities had defined a multi-year security improvement program that included cyber security, however, these additional programs did not have a defined budget and costs were being absorbed as part of business-as-usual activities.

1.79 The ANAO found that the number of assessed entities that reported an Ad-hoc or Developing maturity level had not significantly changed since last year’s assessment. Although the overall number of entities not meeting the required Policy 10 maturity level remained similar, the number of entities reporting an Ad-hoc maturity level had increased from five per cent to 30 per cent. This was due to changes in the requirements within Policy 10 and the Essential Eight.

1.80 The number of entities that reported as meeting the Managing maturity level (two) has not changed since the 2020–21 PSPF self-assessments. The changes in Policy 10 have caused most NCEs to prioritise the alignment of maturity levels across all Essential Eight mitigation strategies before progressing to the higher maturity level (NCEs are aiming to achieve Maturity Level One across all mitigation strategies prior to progressing to Maturity Level Two).

1.81 The PSPF cyber security requirements have been in place since 2013, with the March 2022 update mandating the implementation of all Essential Eight mitigation strategies. Entities’ inability to meet changing requirements indicates a weakness in implementing and maintaining strong cyber security controls over time.

1.82 Previous ANAO audits of entity compliance with PSPF cyber security requirements have not found a significant improvement over time. The work undertaken as part of this review indicates that this pattern continues, with limited improvements.

1.83 The Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) Report 485 Cyber Resilience (2020)54, Auditor-General Report No. 53 2017–18 Cyber Resilience55 and Auditor-General Report No. 32 2020–21 Cyber Security Strategies of Non-Corporate Commonwealth Entities56 recommended strengthening of arrangements for verifying self-assessment results and accountability for the implementation of mandatory cyber security requirements.

1.84 While entities’ compliance with PSPF cyber security requirements remains low, there continues to be the risk of compromise to information relevant to the preparation of financial statements.

Interim audit results

1.85 Audit findings are raised in response to the identification of a potential business or financial risk posed to an entity. Often these risks arise from deficiencies within an entity’s internal control processes or frameworks. Weaknesses in internal controls increase the possibility that a material misstatement of an entity’s financial statements will not be prevented or detected in a timely manner. The ANAO rates audit findings according to the potential business or financial management risk posed to the entity. The rating scale is presented in Table 1.5.

Table 1.5: Findings rating scale

|

Rating |

Description |

|

Significant (A) |

Issues that pose a significant business or financial management risk to the entity. These include issues that could result in a material misstatement of the entity’s financial statements. |

|

Moderate (B) |

Issues that pose a moderate business or financial management risk to the entity. These may include prior year issues that have not been satisfactorily addressed. |

|

Minor (C) |

Issues that pose a low business or financial management risk to the entity. These may include accounting issues that, if not addressed, could pose a moderate risk in the future. |

|

Significant legislative breach (L1) |

Instances of significant potential or actual breaches of the Constitution; and instances of significant non-compliance with the entity’s enabling legislation, legislation that the entity is responsible for administering, and the PGPA Act. |

|

Other non-compliance with legislation (L2) |

Other instances of non-compliance with legislation the entity is required to comply with. |

|

Non-compliance with subordinate legislation (L3) |

Instances of non-compliance with subordinate legislation, such as the PGPA Rule. |

Source: ANAO reporting policy.

1.86 A summary of findings identified at the end of the interim phase in Table 1.6 below. The table includes all findings reported to the 27 entities included in this report.

Table 1.6: Audit findings by category for the 2022–23 interim period

|

Category |

Significant |

Moderate |

Minor |

Main areas of weakness |

|

IT control environment |

– |

21 |

28 |

|

|

Compliance and quality assurance frameworks |

– |

– |

4 |

|

|

Accounting and control of non-financial assets |

– |

3 |

2 |

|

|

Revenue, receivables and cash management |

– |

1 |

3 |

|

|

Human resources financial processes |

– |

– |

1 |

|

|

Purchases and payables management |

– |

2 |

5 |

|

|

Financial statements preparation |

– |

– |

– |

|

|

Other audit findings |

– |

2 |

4 |

|

|

Legislative breaches |

– |

2 |

– |

|

|

Total |

– |

31 |

47 |

|

Source: Compilation of ANAO interim audit findings.

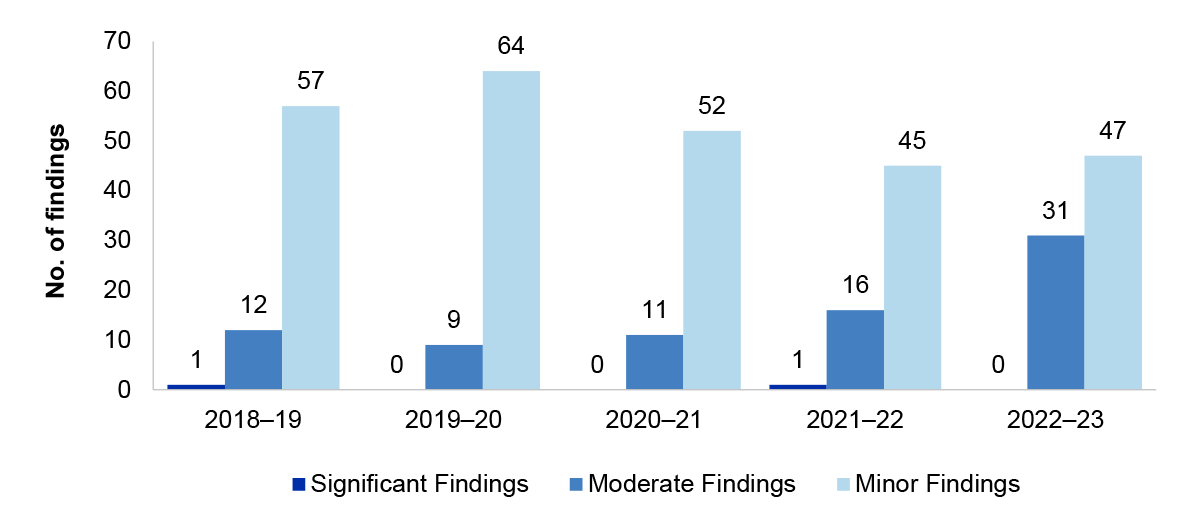

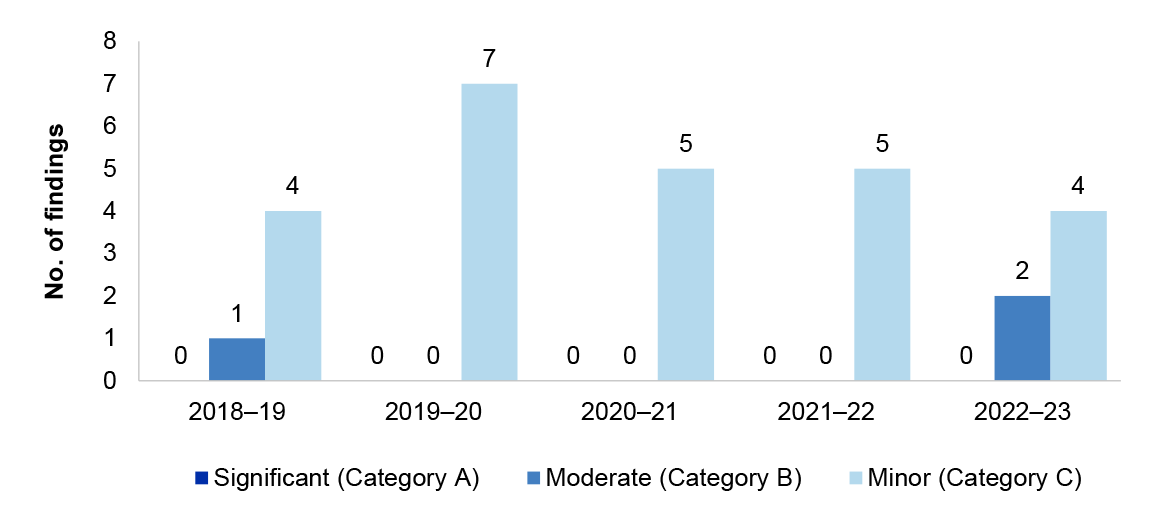

1.87 A summary of all significant, moderate, minor and legislative findings reported at the conclusion of the interim audit phase across the past five financial years is presented in Figure 1.5 below.

Figure 1.5: Trend in aggregate interim findings 2018–19 to 2022–23

Source: ANAO data.

Information Technology Control Environment

1.88 The review of information systems and related controls is an integral part of an entity’s control environment. This section summarises the results from interim tests of the operating effectiveness of general IT controls for each of the entities included in this report.

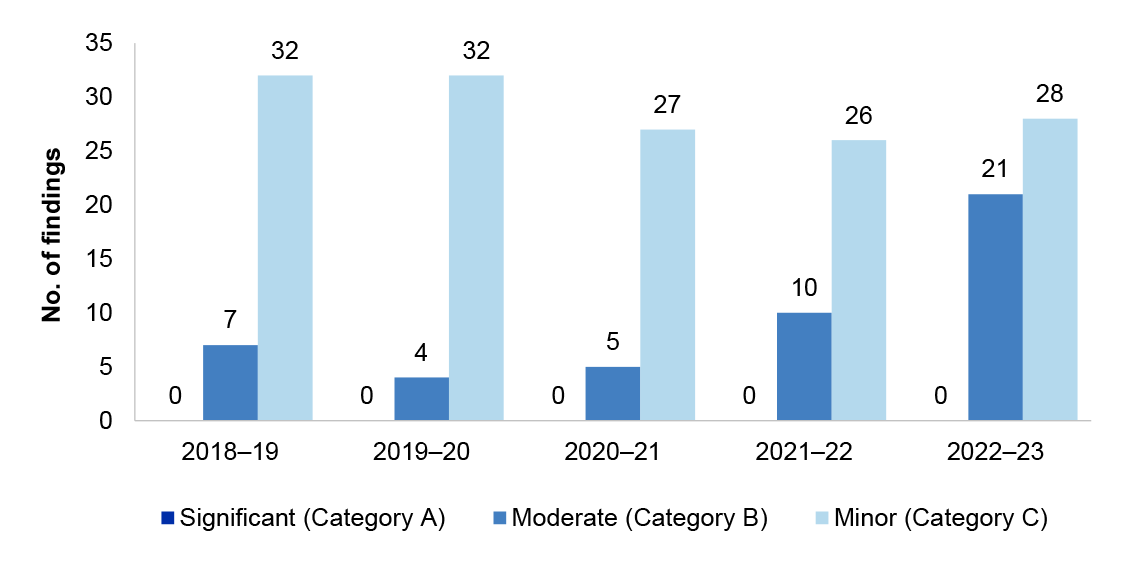

1.89 Figure 1.6 demonstrates the trends in interim audit findings related to entities’ overall IT control environments from 2018–19 to 2022–23. At the time of this report, testing of the operating effectiveness of IT controls had not been completed for was still in progress for three entities.57

Figure 1.6: IT control environment interim findings 2018–19 to 2022–23

Source: ANAO data.

1.90 Findings related to entities’ IT control environments represent 63 per cent of total findings identified during the 2022–23 interim period. IT control environment findings continue to represent the highest proportion of all findings. There were 21 moderate findings reported in 2022–23 compared to 10 moderate findings reported in 2021–22. Further details relating to the moderate findings are detailed in chapter 3 for the Attorney-General’s Department and the Departments of: Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water; Defence; Education; Employment and Workplace Relations; Finance; Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts; Social Services; the Treasury; Veterans’ Affairs; Home Affairs; and National Disability Insurance Agency and Services Australia.

1.91 The information systems control environment findings reported at the conclusion of the 2021–22 interim audits for entities included in this report have been grouped as follows:

- IT security;

- IT change management; and

- disaster recovery arrangements.

IT Security

1.92 IT security is concerned with protecting an entity’s information assets from internal and external threats. It includes controls to prevent or detect unauthorised access to systems, programs and data. In the context of the financial statements audit, the focus is on the financially significant systems and data only. The Protective Security Policy Framework58 (PSPF) sets out the government protective security policy and the Australian Cyber Security Centre’s Information Security Manual59 (ISM) provides guidance on strategies for protecting information and systems from cyber threats.

1.93 The key controls areas that address risks relating to IT security and that are assessed as part of the interim audit are:

- IT security governance;

- general and privileged user access; and

- monitoring and reporting.

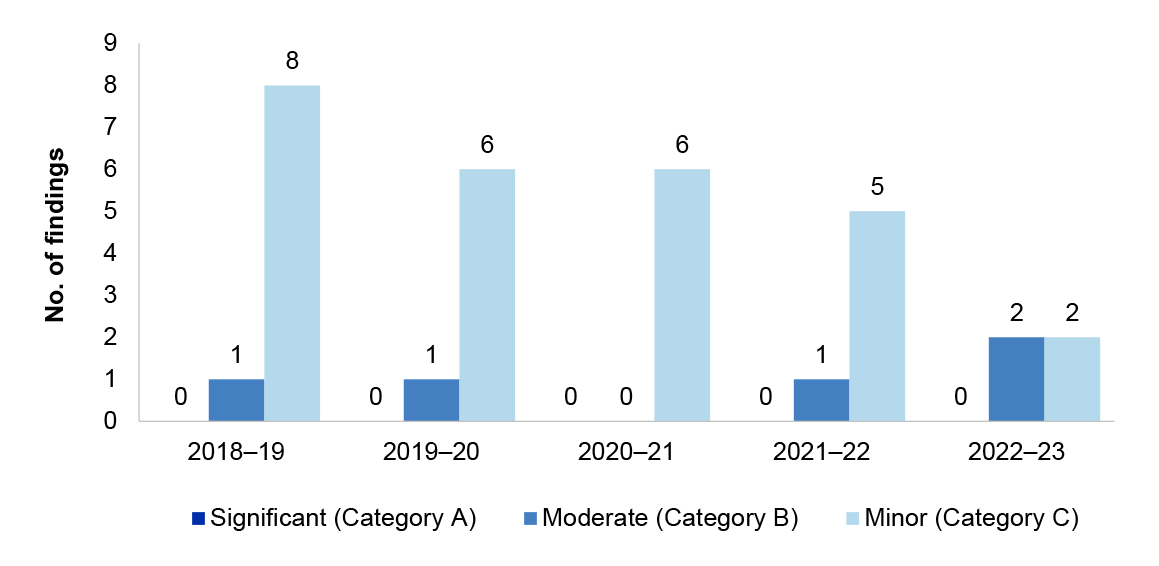

1.94 Figure 1.8 illustrates the trends in findings observed in entities’ IT security arrangements between 2018–19 and 2022–23.

Figure 1.7: IT security interim findings 2018–19 to 2022–23

Note: The comparative numbers in this figure have been updated to include findings previously categorised as IT application controls which related to IT security.

Source: ANAO data.

1.95 The IT security findings represent 86 per cent of all IT-related findings reported in 2022–23. Nineteen moderate findings were reported in the 2022–23 interim audit. Further details of the moderate findings are detailed in chapter 3.60

1.96 A review of all IT security findings identified issues in the following areas:

- logging and monitoring of privileged user activity;

- user access management, including approving new user access and performing regular user access reviews;

- removal of user access when it is no longer required;

- password configuration; and

- risk management and monitoring of controls.

1.97 Users with administrative access privileges, commonly referred to as privileged users, are able to make significant changes to IT systems’ configuration and operation, bypass critical security settings and access sensitive information. As part of reviewing IT security arrangements, different groups of privileged users were examined, including:

- application administrators, sometimes referred to as super users;

- database administrators;

- system administrators; and

- network or domain administrators.

1.98 To reduce the risks associated with this access, the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD) Information Security Manual (ISM) specifies that privileged user access be appropriately restricted and when provided, that the access is logged, regularly reviewed and monitored. Three moderate and four minor findings related to the logging and monitoring of privileged user access. Two new moderate findings related to issues with the monitoring of privileged user activities at the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water, and National Disability Insurance Agency. Both latter mentioned entities have not established adequate processes for reviewing access performed by privileged users, including documenting the results and outcomes of reviews. The third moderate finding was reported to Services Australia and related to issues with security configurations for managing and logging privileged user activities and the robustness of monitoring and investigation processes. The four minor findings related to issues with the design of controls, such as the scope of access being monitored, completeness and accuracy of audit logs, and the independence of monitoring activities. The risk of inappropriate changes to financially significant systems and data arising from these findings is partially mitigated through alternate controls.

1.99 All users with access to financial systems may have the ability to change financial information, and therefore access should only be granted where it is required for the performance of the role; and should be reviewed whenever the role changes. Two moderate and seven minor findings related to granting and reviewing user access. The moderate findings reported to Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water and Department of Veterans’ Affairs related to user access reviews not being performed. The seven minor findings related to managing access to payment files, approving of new user access and timeliness of user access reviews.

1.100 Entities must remove or suspend user access on the same day that a user no longer has a legitimate business requirement for its use.61 Terminating a user account when the user no longer has a requirement to access it, such as upon departure from an entity, can prevent unauthorised use. There were ten moderate findings in this area and an additional five minor findings. The ten moderate findings related to weaknesses in monitoring controls and access being performed by users who no longer required such access. The ten moderate findings were reported to the Attorney-General’s Department and the Departments of: Defence; Education; Employment and Workplace Relations; Finance; Home Affairs; Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts; Social Services; and Veterans’ Affairs, and the National Disability Insurance Agency. The five minor findings related to access not being removed when it was no longer required and issues related to the design of controls, such as scope of access being reviewed and controls not being implemented in accordance with policies and procedures.

1.101 The ISM provides guidance on the password requirements for Australian Government systems. In October 2019 the ASD updated this guidance to specify passphrase requirements for instances where multi-factor authentication62 is not supported; passphrases used for single-factor authentication should be at least four random words with a minimum of 14 characters63. There were six minor findings in this area. Inadequate password controls increase the likelihood of unauthorised access to systems and data.

1.102 Monitoring the performance of security controls is essential to maintaining an entity’s security posture. It can contribute to improving the implementation of minimum core and supporting PSPF requirements, the detection of new and emerging security risks, and the identification controls that are not operating as planned. Four moderate findings and one minor finding related to the management and monitoring of security controls. Two moderate findings were reported to the Department of Veterans’ Affairs and related to issues with monitoring the implementation and operation of security controls and remediation of security risks. One moderate finding was reported to the Department of Defence and related to issues with controls for managing personally identifiable information, such as tracking access to information and the completion of compliance activities. The fourth moderate finding was reported to the Department of the Treasury and related to issues with managing security risks and managing the design, implementation and operation of associated security controls. The minor finding related to issues with monitoring the performance of controls within third party providers.

1.103 The weaknesses identified within this category increase the risk of unauthorised access to systems and data, or data leakage. Entities should review their management of these areas in light of the recommendations of the ISM and the risks to their operational environment.

IT change management

1.104 IT change management provides a disciplined approach to making changes to the IT environment. It includes controls to prevent unauthorised changes being introduced, and to reduce the likelihood that normal business operations are interrupted with the implementation of authorised changes.

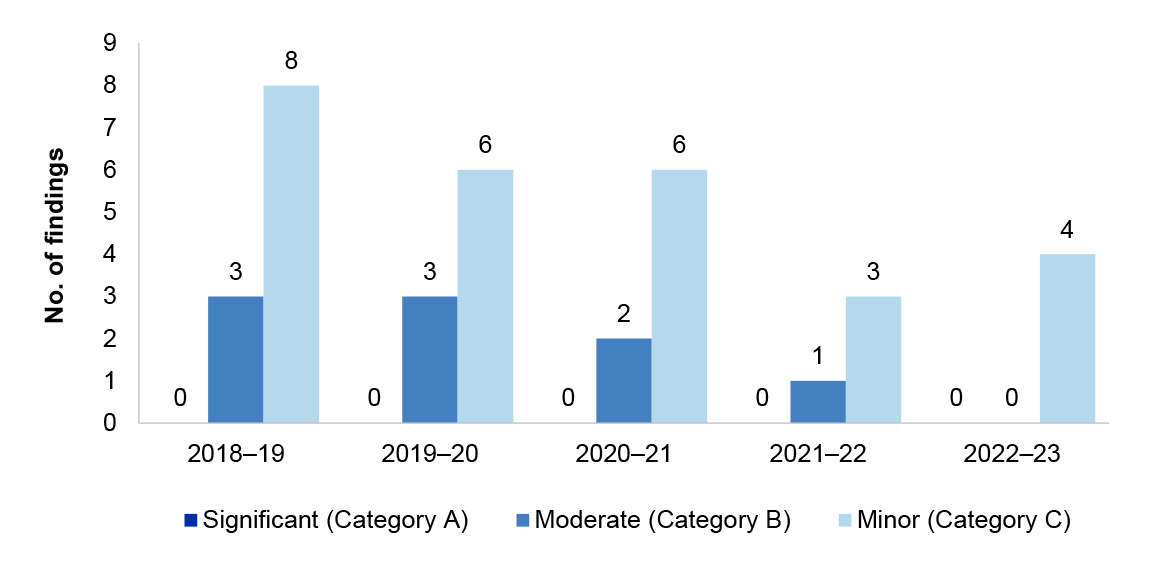

1.105 Figure 1.9 illustrates the trends in findings identified in entities’ IT change management controls between 2018–19 and 2022–23.

Figure 1.8: IT change management interim findings 2018–19 to 2022–23

Source: ANAO data.

1.106 Changes to entities’ IT environments were managed using standardised processes, usually based on the ITIL Framework.64 While still low when compared to IT security, the number of findings in this area still highlights the importance of maintaining and monitoring performance of change management processes.

1.107 Two moderate findings and two minor findings related to weaknesses in the operation of the change management processes were reported as a result of the interim audits. The National Disability Insurance Agency and Services Australia each had moderate findings relating to issues with restricting developer access to production systems and data, and monitoring changes performed by those with access to developer functions. The two minor findings relate to managing developer access to production systems and data, and management of batch processing and reporting data.

1.108 Weaknesses in change management elevate the risk of unauthorised or untested changes to systems during these activities. These weaknesses may also affect the availability or reliability of the overall IT environment. Entities should monitor the operating effectiveness of their IT control environments to mitigate risks.

Disaster recovery arrangements

1.109 Disaster recovery is concerned with the resumption of the IT environment including systems and data following an interruption to services. It relies on:

- effective back-up and recovery arrangements, to allow data to be recovered from current versions of key IT systems; and

- disaster recovery planning, including the development, maintenance and testing of a disaster recovery plan to enable IT systems to be recovered in line with defined business requirements.

1.110 The ANAO assesses entities’ disaster recovery arrangements in view of the potential for a disruptive event to impact on financial reporting. Figure 1.10 illustrates the trend for findings identified in entities’ disaster recover arrangements between 2018–19 and 2022–23.

Figure 1.9: Disaster recovery interim findings 2018–19 to 2022–23

Source: ANAO data.

1.111 In all cases where general IT controls testing has been completed, ANAO found that entities undertook regular backups of financially significant data. The three minor findings related to weaknesses in managing service provider performance, management of batch processing and scope of business continuity and disaster recovery arrangements. These findings increase the risk that, in the event of a significant disruption, systems and data will not be recovered within an acceptable timeframe.