Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Government Business Managers in Aboriginal Communities under the Northern Territory Emergency Response

The objective of the audit was to assess the administrative effectiveness of FaHCSIA's management of the GBM initiative, and the extent to which the initiative has contributed to improvements in community engagement and government coordination in the Northern Territory.

The audit focused on FaHCSIA's management of the GBM initiative under the NTER. The audit scope did not include additional functions assigned to some GBMs in the Northern Territory under the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Service Delivery (the National Partnership Agreement), or to Australian Government staff with similar roles and functions supporting the implementation of the National Partnership Agreement in Queensland and Western Australia.

Summary

Introduction

1. Government Business Managers (GBMs) are Australian Government officers recruited to support the implementation and monitoring of the Northern Territory Emergency Response (NTER), a five-year, whole-of-government intervention commencing in June 2007 to promote community safety in the Northern Territory. Residing and working in NTER communities full time, GBMs are intended to be ‘the single face of the Australian Government at the local community level—akin to an ambassador'.[1]

2. GBMs were initially deployed to facilitate the rollout of the NTER by providing a channel through which government could communicate to communities about how different aspects of the NTER would work. GBMs were expected to exercise a leadership role in coordinating Australian Government services, consult communities on changes in Australian Government policy and programs, and report back to the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA)[2] as the lead agency for the NTER.

Community safety

3. Safe and supportive families and communities provide a resilient, caring and protective environment, promoting a range of positive outcomes. Problems in families and communities, among other influences, can contribute to disrupted social relationships and social alienation, and to alcohol and drug misuse and family violence. There is a growing body of literature highlighting the extent of violence in Indigenous communities, particularly family violence. The presence of family violence is a strong predictor of child abuse, and partner violence has a damaging effect on children's emotional, behavioural and cognitive development.

4. According to the Productivity Commission:

Child abuse and neglect contribute to the severe social strain under which many Indigenous people live. Ensuring that Indigenous children are safe, healthy and supported by their families will contribute to building functional and resilient communities. The need for intervention for protective reasons may also reflect the social and cultural stress in many Indigenous communities. In such conditions, the extended networks that could normally intervene in favour of the child may no longer exist.[3]

5. In June 2006 the then Australian Government, under the auspice of the Council of Australian Governments (COAG), convened the Intergovernmental Summit on Violence and Child Abuse in Indigenous Communities (the Summit), involving ministers from all states and territories. COAG acknowledged the contribution of poor child health and education to an intergenerational cycle of social dysfunction, and agreed to an early intervention measure to improve the health and wellbeing of Indigenous children living in remote areas by trialling an accelerated rollout of the Indigenous child health checks in high need regions. The outcomes of the Summit in the 2006 COAG Communiqué and these other developments provide a backdrop to the measures adopted in the NTER announced one year later.[4]

6. Following the Summit, and as a result of advocacy by the then Australian Government and others, the NT Government appointed the Board of Inquiry into the Protection of Aboriginal Children from Sexual Abuse (Board of Inquiry) on 8 August 2006. The Board of Inquiry's report, titled Ampe Akelyernemane Mele Mekarle, Little Children are Sacred,[5] was released by the NT Chief Minister on 16 June 2007. The report indicated that, in all 45 communities visited by the Board of Inquiry, child abuse and potential neglect of children had been reported. The Board of Inquiry considered there was evidence of a strong connection between family abuse, child neglect and violence on the one hand and alcohol and substance abuse on the other. The report reiterated other issues identified in previous reports as contributing to breakdowns in community safety: people without meaningful things to do; a failure of existing service delivery methodologies; dysfunctional governance; and overcrowded houses.

The Northern Territory Emergency Response

7. The then Government announced the rollout of the NTER on 21 June 2007. The immediate aims of the NTER measures were to protect children and make communities safe. In the longer term, the measures were designed to create a better future for Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory. The overall goal of the NTER was to do and achieve more than ‘business as usual' and to lay down a platform from which to work towards sustained improvements in outcomes for Aboriginal people and communities in the medium and longer term.

8. The NTER would comprise three phases:

-

stabilisation—the first year to 30 June 2008;

-

normalisation of services and infrastructure; and

-

longer term support to close the gaps between these communities and standards of services and outcomes enjoyed by the rest of Australia.

9. The NTER identified seven broad areas for government intervention in the Northern Territory: promoting law and order; improving child and family health; supporting families; enhancing education; welfare reform and employment; housing and land reform; and coordination. Specific interventions made under these broad areas included quarantines on welfare income, restrictions on alcohol and pornography, health checks for children, increased police presence and changes to land tenure arrangements.[6]

The Government Business Managers initiative

10. When the then Minister for Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, the Hon Mal Brough MP, announced the national emergency response to protect Aboriginal children in the Northern Territory, his press release noted that the NTER measures would involve ‘improving governance by appointing managers of all government business in prescribed communities.' The interrelated nature of the seven overarching measures, the immediacy of their implementation timeframes, the requirement for significant whole-of-government cooperation and the emergency context of the NTER created a need for enhanced coordination and governance arrangements at the community level and within the Australian Government.

11. FaHCSIA's submission to the NTER Review Board in 2008 details that GBMs were intended ‘to improve governance of communities…so that problems can be tackled community by community, with local input and ownership'.[7] The Australian Government committed to deploying GBMs into remote communities over five years. According to FaHCSIA, this was

[recognition] that for the Government's investment and service delivery reforms to have maximum effect, a local presence and source of intelligence is required who can report reliably on:

- the operating context for the rollout of the emergency measures

- community and corporate governance and performance, particularly of government-funded service delivery organisations delivering both mainstream and Indigenous-specific services

- the wider impact of government investments into communities (including the respective impacts of other levels of government).[8]

12. As at August 2010 there were 60 GBMs servicing 73 NTER communities. In a change from previous service delivery arrangements, which saw public servants visit communities on an ‘as required' basis, GBMs reside in communities full time and present a single face for the Australian Government. While maintaining agency line reporting relationships, Australian Government staff from all agencies are required to ‘carry out their work under GBM guidance so as to optimise the timing, sequencing and connections with other initiatives…and ensure effective and orderly engagement with the community.'[9]

13. In addition to departmental funding to recruit, deploy and support GBMs, the Australian Government agreed to establish a fund of approximately $11 million each year for GBMs to implement specific projects in the communities to which they were appointed. This fund has been known in different years of the NTER as the Flexible Funding Pool, the Community Capability Fund and the Local Priority Fund. According to FaHCSIA, this funding arrangement ceased at the end of 2009–10.

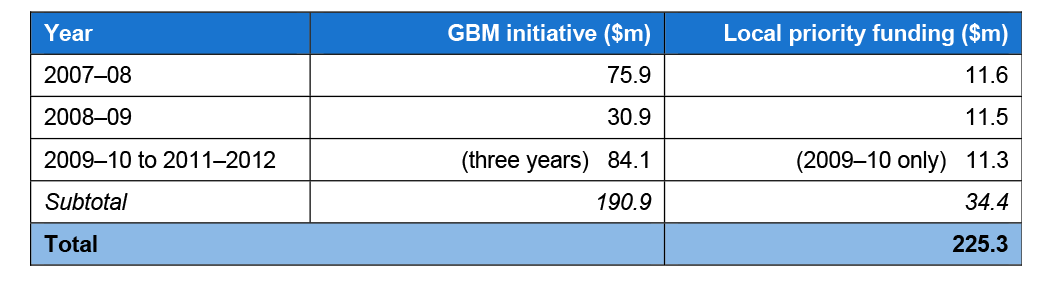

14. Table 1 below shows the budget for the GBM initiative and its associated local priority project funding for the five years of the NTER.

Table 1 Annual budget for the GBM initiative

Audit Objective and scope

15. The objective of the audit was to assess the administrative effectiveness of FaHCSIA's management of the GBM initiative, and the extent to which the initiative has contributed to improvements in community engagement and government coordination in the Northern Territory.

16. The audit focused on FaHCSIA's management of the GBM initiative under the NTER. The audit scope did not include additional functions assigned to some GBMs in the Northern Territory under the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Service Delivery (the National Partnership Agreement), or to Australian Government staff with similar roles and functions supporting the implementation of the National Partnership Agreement in Queensland and Western Australia.

Audit Criteria

17. In order to address the audit objective, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) examined the following areas:

- the alignment between the overall objective of the GBM initiative and the design of the program's activities;

- strategic program management arrangements developed by FaHCSIA to support the delivery of GBM activities;

- the implementation of the core activities of GBM recruitment, deployment and support; and

- the effectiveness of reporting systems designed to support GBMs in their engagement and coordination roles..

Overall Conclusion

18. The Northern Territory Emergency Response (NTER) represented a significant and rapid shift in the way the Australian Government delivered programs in Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory. Community safety concerns had been building for several years but the release of a report into child abuse in the Northern Territory led the Australian Government to adopt a more interventionist approach to tackling these policy concerns than had previously been the case. This approach sought to address the identified policy challenges through a series of cross-sectoral but interrelated activities or ‘measures' that required significant whole-of-government cooperation. This created a need for enhanced coordination and engagement arrangements at the community level.

19. The environment in which the NTER was developed was characterised by the then government as a ‘national emergency'. Many aspects of the NTER's implementation were considered controversial by some sections of the Australian community as they directly intervened in aspects of individual and community life. The NTER was a complex undertaking involving sensitive matters and the Government required it to be established and implemented in a short period of time.

20. Implementing the required administrative arrangements to support the NTER under these conditions presented the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services (FaHCSIA) with a number of challenges in its role as lead agency for Indigenous affairs and the NTER. While some precedents for the approach of the NTER could be found in Australia's international activities, such as the Regional Assistance Mission to the Solomon Islands (RAMSI), there were few domestic precedents on which FaHCSIA could draw to develop appropriate administrative arrangements. Further, improving whole-of-government coordination is not a straightforward objective, as ‘existing public sector institutions were, by and large, not designed with a primary goal of supporting collaborative inter-organisational work'.[10]

21. Against this background, FaHCSIA worked effectively to support the initial delivery of the NTER through the development and implementation of the Government Business Managers (GBMs) initiative. Immediate and ongoing engagement with the Secretaries Group on Indigenous Affairs secured high-level agreement about GBMs' roles and responsibilities and their activities under each of the NTER measures. By drawing on its existing human resource capabilities, FaHCSIA was able to give practical effect to this agreement by rapidly recruiting and deploying GBMs to support each of the communities targeted by the NTER, positioning them to support the achievement of the initiative's engagement and coordination objectives.

22. Lessons learned from the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) Indigenous service delivery trials from 2002 to 2006 indicate that a stable Australian Government presence in communities can result in measurable improvements in community engagement and whole-of-government coordination. As a results of its efforts during the initial stabilisation phase of the NTER and its ongoing management of the GBM initiative, FaHCSIA has established a stable presence in the NTER communities. GBM deployment data shows that most communities have been supported by the same GBM for at least 12 months at a time, and that in approximately one in three communities there has only been a single GBM handover since the commencement of the NTER.

23. Over time, as the NTER has moved beyond the initial implementation phase, GBMs' coordination efforts have come to be hampered by the persistence of vertical, single-agency approaches to service delivery and by other agencies' waning recognition of GBMs' coordination role in communities. At the end of 2008, the NTER Review Board observed that ‘there remain[ed] a major gap between the laudable intention of whole-of-government management and the reality of its implementation on the ground'.[11] Prioritising the issues arising from GBMs' local engagement activities, forwarding these issues to relevant areas within FaHCSIA and to other agencies and tracking their resolution is also an ongoing challenge for the department. Both of these issues can bear on the overall effectiveness and value of GBMs' local-level engagement and coordination activities.

24. The development of local service delivery agreements, such as those developed for the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Service Delivery, could help to formalise local service delivery relationships, provide GBMs with strategic priorities and strengthen GBMs' authority in communities, and serve to improve communities' understanding of GBMs' roles and responsibilities. Improvements to the communication of issues within FaHCSIA and to other agencies will help to give practical effect to GBMs' engagement efforts, while ongoing development of systems to track agencies' responses to issues raised by GBMs should also provide an incentive for those agencies to better engage at the local level.

25. Throughout the audit, the ANAO raised a number of issues relating to the GBM initiative's management with FaHCSIA, and the department has already begun to address these issues. In order to assist FaHCSIA to improve program management arrangements for the GBM initiative, the ANAO has made one recommendation. This relates to reaffirming agencies' recognition of the authority given to GBMs, and supporting this recognition at the local level through the development of service delivery agreements.

Program design

26. FaHCSIA was required to develop administrative arrangements to support the deployment of 60 GBMs to work with 73 communities in order to develop an understanding of local priorities and to coordinate the engagement of a range of different Australian Government agencies. The arrangements that emerged during the initial phase of the NTER were well aligned with the Australian Government's engagement and coordination objectives for Indigenous communities in the Northern Territory. The development of an engagement and reporting model that connects the issues of a single community to multiple agencies in the APS through the GBMs is also an appropriate design element.

27. The portfolio-based arrangements that have been the basis of the Australian public service have a number of advantages, including strong vertical bonds that enhance accountability, increase specialisation, and create an efficient division of labour. However, these same bonds can impede government efforts to tackle ‘wicked' policy problems that cross portfolios, including Indigenous disadvantage. Traditional hierarchical models of public administration would have been challenged to support the coordinated delivery of the NTER at the local level.

28. Accordingly, the administrative design that has emerged for GBMs has more in common with a networked governance model than a traditional public sector program. Developing local networked governance arrangements allows coordination and collaboration to occur at the service delivery level while maintaining the advantages afforded by vertical departmental structures. Further, this approach reflects contemporary views relating to the benefits of citizen-centred public service delivery by establishing closer links between the recipients of Australian Government services and the agency staff responsible for delivering those services. However, local arrangements also face a number of challenges, including the need to secure and maintain authority, joining up specialised systems and resources in communities, and measuring improvements in coordination and engagement.

Program management

29. The GBM initiative was developed in an emergency context, with design and agency consultation arrangements completed in a matter of weeks. By engaging with the Secretaries Group on Indigenous Affairs and its Minister at the commencement of the NTER, FaHCSIA quickly secured whole-of-government agreement about the initiative's purpose and scope. Further, FaHCSIA sought to align the GBM initiative's activities with those of other NTER measures by documenting GBMs' roles and responsibilities for each of the new NTER initiatives.

30. The GBM initiative is a complex activity that requires both an element of responsiveness and an element of longer term planning to sustain its implementation. Its objectives of enhanced community engagement and improved government coordination will not necessarily be achieved by undertaking a series of planned activities in the same way as a typical project. Rather, it is likely that progress toward its objectives will be achieved through the maintenance of an active, stable presence in communities, able to respond quickly to changing circumstances and emerging policy initiatives.

31. A necessary focus on implementation during the emergency phase limited the early development of formal program management arrangements, with the department drawing on existing capabilities and new, NTER-specific management structures to provide effective management for the GBM initiative instead. Longer-term planning and risk management approaches would be expected to be developed over time, but uncertainty about the future direction of the NTER and the GBM initiative have made it necessary to be more cautious about developing these approaches. Accordingly, formal reviews of program management arrangements, previously planned for each phase of the NTER, are only now taking place. FaHCSIA has advised that it is developing longer-term project planning and risk management arrangements in order to support the GBM initiative's ongoing integration with its regular management arrangements in the Northern Territory.

Program implementation

32. FaHCSIA's workforce management strategies were effective, particularly given the scale and emergency context of the GBM initiative. Despite pressure to recruit and deploy more than 50 senior managers to remote locations in a short period, FaHCSIA delivered a recruitment round consistent with APS requirements, an orientation program and remote area accommodation.

33. The department's efforts resulted in the deployment of 28 GBMs by September 2007, and a total of 51 GBMs in the first year of the emergency response. Overall, GBM coverage of communities has been consistent, with most communities having a continuous GBM presence throughout the NTER; where breaks have occurred, these have been of limited duration and largely covered by relief GBMs. The GBM initiative has also provided most communities with a more stable Australian Government presence, with one in three experiencing only a single handover since the commencement of the NTER, and more than 80 per cent having three or fewer different GBMs.

34. As the NTER has progressed, different areas of the department have sought to refine particular aspects of workforce planning for the GBM initiative, such as performance management and support arrangements. FaHCSIA has recently established a Change Management Team to integrate management of the GBM workforce with the department's broader strategy for the Northern Territory. This step should better position the department to effectively plan for future workforce requirements.

Program performance

35. GBMs face the significant challenge of supporting, advising and monitoring the efforts of a large number of Australian Government, Territory government and local government agencies, engaging with many different community stakeholders, as well as liaising with funded service providers and NGOs. They undertake this work in difficult circumstances, facing geographical and social isolation in an environment characterised by frequent demands and short deadlines. GBMs' engagement and coordination efforts would be enhanced by reaffirming and sustaining agencies' recognition of their authority in communities, and the development of local implementation plans or service delivery agreements, such as those required under the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Service Delivery.

36. The GBM initiative would benefit from the development of arrangements to measure improvements to engagement and coordination arising from GBMs' activities, including an improved suite of performance indicators to monitor short-term progress and the clearer articulation of long-term evaluation approaches. The ANAO acknowledges the difficulty of determining whether whole-of-government coordination activities have been effective. However, the GBMs are a sizeable investment and an innovative approach, and future attention to developing performance measurement arrangements will assist the department to capture lessons learned to inform future reforms and make better decisions about continued resourcing for the initiative. Accordingly, there would be merit in investigating appropriate options.

37. Issues with current reporting arrangements are impeding the effective communication of issues raised by GBMs to agencies for appropriate action. In particular, there are opportunities for FaHCSIA to improve GBM reporting, agency issue forwarding and tracking arrangements. This will improve the consistency and relevance of information the GBM initiative provides to decision-makers within FaHCSIA and in other agencies, and support the translation of GBMs' local engagement efforts into improved service delivery arrangements, increasing the likelihood the GBM initiative will improve government coordination. FaHCSIA has advised that these improvements are currently under development.

38. Local priority funding arrangements supporting the GBM initiative resulted in the delivery of 358 new projects in NTER communities in the first two years of the NTER. The development of improved guidance and assessment criteria would have supported better decisions about whether particular capital purchases and infrastructure works were eligible for funding.

Summary of agency response

39. FaHCSIA appreciates the opportunity to respond to the ANAO Section 19 Report. Each of the Groups and Sections involved in the audit and the resulting recommendations contributed to this response and the summary of actions.

40. FaHCSIA has considered and agreed the recommendation in the Section 19 Report. FaHCSIA will continue to work with the ANAO to implement the action and resolve the recommendation.

Footnotes

[1] FaHCSIA, Government Business Managers Statement of Roles and Responsibilities.

[2] At the commencement of the NTER in June 2007, the department was known as the Department of Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaCSIA). For consistency, the ANAO refers to ‘FaHCSIA' throughout this report.

[3] Productivity Commission, Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage: Key Indicators 2009, p. 4.115

[4] COAG Meeting Outcomes 14 July 2006. <http://www.coag.gov.au/coag_meeting_outcomes/2006-07-14/index.cfm> [accessed 21 November 2009]

[5] Wild, R & Anderson P, (2007) Ampe Akelyernemane Mele Mekarle, Little Children are Sacred: Northern Territory Board of Inquiry into the Protection of Aboriginal Children from Sexual Abuse, Darwin, NT. Northern Territory Government. <http://www.inquirysaac.nt.gov.au> [accessed 21 November 2009]

[6] FaHCSIA Submission of Background Material to the NTER Review Board, 2008:11. <http://www.fahcsia.gov.au/sa/indigenous/pubs/nter_reports/documents/nter_review_submission/nter_review_submission.pdf> [accessed 22 November 2009]

[7] Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, Submission to the NTER Review – Background material on the NTER, <http://www.nterreview.gov.au/docs/nter_review_submission/app1.htm#t7>

[8] FaHCSIA paper to Secretaries Group on Indigenous Affairs Sub-Group on the Northern Territory Emergency Response, 25 October 2007

[9] FaHCSIA, Government Business Managers Statement of Roles and Responsibilities.

[10] Australian Public Service Commission 2007, Tackling Wicked Problems: A Public Policy Perspective, p.17.

[11] NTER Review Board 2008, Report of the NTER Review Board, p.45.