Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Recruitment and Retention of Specialist Skills for Navy

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to examine the effectiveness of Navy’s strategy for recruiting and retaining personnel with specialist skills. The effective delivery of Navy capability depends on Navy having available sufficient numbers of skilled personnel to operate and maintain its fleet of sea vessels and aircraft, and conduct wide‑ranging operations in dispersed locations. Without the right personnel, Navy capability is reduced. Navy’s budget for 2014–15 included $1.86 billion in employee expenses.

The audit concluded that, in its strategic planning, Navy had identified its key workforce risks and their implications for Navy capability. To address these risks Navy had continued to adhere to its traditional ‘raise, train and sustain’ workforce strategy; developed a broad range of workforce initiatives that complemented its core approach; and sought to establish contemporary workforce management practices. However, long‑standing personnel shortfalls in a number of ‘critical’ employment categories had persisted, and Navy had largely relied on retention bonuses as a short‑ to medium‑term retention strategy.

Navy had developed a broad range of workforce initiatives, some designed specifically to address workforce shortages in its critical employment categories. To date, Navy had primarily relied on paying retention bonuses and other financial incentives; recruiting personnel with prior military experience to work in employment categories with significant workforce shortfalls; and using Navy Reserves in continuous full time roles. Ongoing work was required for Navy to firmly establish a range of promising workforce management practices, including providing the right training at the right time; more flexible approaches to managing individuals’ careers; and improving workplace culture, leadership and relationships. More flexible and tailored workforce management practices could help address the underlying causes of workforce shortfalls, particularly when the traditional approaches were not gaining sufficient traction.

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at Navy: drawing on external human resource expertise to inform the development and implementation of its revised workforce plan; and evaluating the impact of retention bonuses on the Navy workforce to determine their future role within its overall workforce strategy.

Summary

Introduction

1. The Royal Australian Navy (Navy) is the maritime arm of the Australian Defence Force (ADF), and its total budget for 2014–15 is $4.79 billion, which includes $1.86 billion in employee expenses.1 The effective delivery of Navy capability depends on Navy having available sufficient numbers of skilled personnel to operate and maintain its fleet of sea vessels and aircraft2, and conduct wide-ranging operations in dispersed locations. Without the right personnel, Navy capability is reduced.

2. To generate its workforce Navy generally adheres to the traditional ‘raise, train, sustain’ principle, which describes the broader ADF’s preference to grow its workforce from the ground up. Over 85 per cent of Navy’s recruits are ab initio, meaning that they do not have any prior military experience. Navy educates, trains and prepares these recruits for military service and their chosen naval job. These recruits may then be promoted through the ranks in accordance with their qualifications and experience. It can take many years for recruits to be fully competent and highly skilled in performing complex managerial and technical roles.

3. Navy’s workforce consists of its Trained Force and Training Force. As at 30 June 2014, Navy had 11 415 members in its Trained Force3 and 2741 members in its Training Force. The Trained Force comprises 60 distinct employment groups or ‘categories’, which include engineers, technicians, warfare sailors and officers, medical personnel, divers, pilots and others.4

4. In June 2014, Navy was short 201 trained personnel, or 1.7 per cent of its required workforce. While this overall figure is relatively low, there can be significant variability in the case of specific employment categories and ranks. Navy has an oversupply of personnel in some employment categories and at certain ranks within categories, and significant shortfalls in others. For example, as at 30 June 2014, the marine technician5 employment category had a workforce shortfall of 23.5 per cent and the medical officer category had a workforce shortfall of 29 per cent. Defence classified these categories as ‘critical’.6 Some of Navy’s critical employment categories, particularly technical sailor, engineering and medical officer categories, have experienced sustained workforce shortfalls for over a decade.

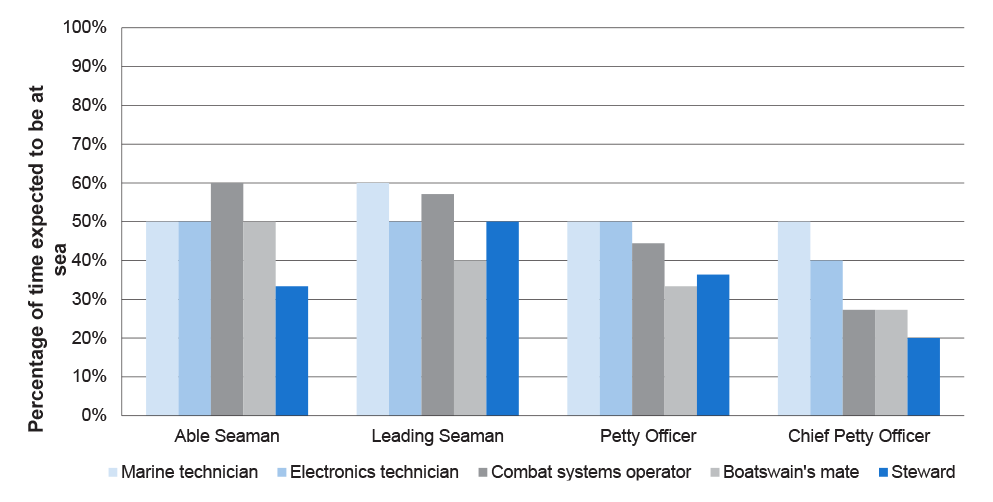

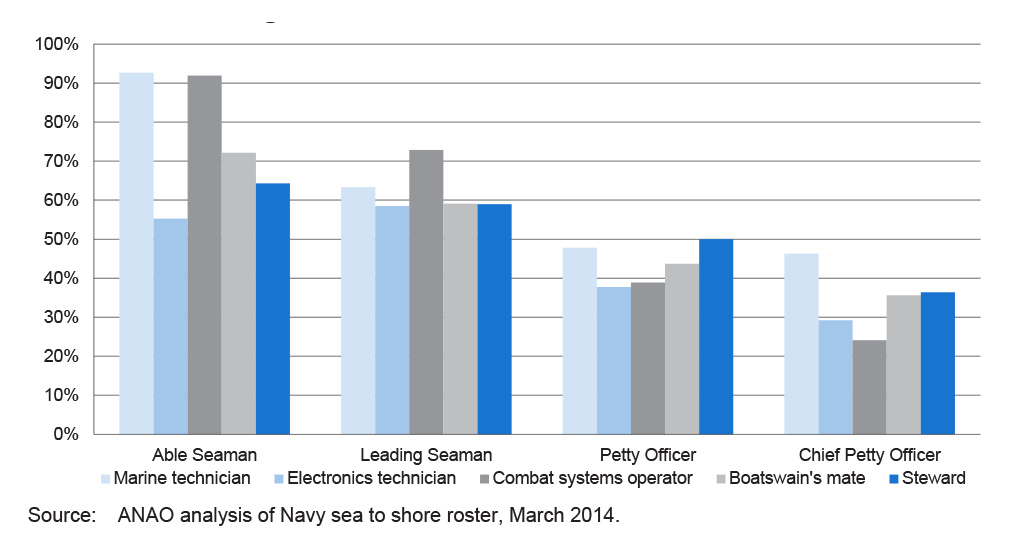

5. Forty per cent of Navy’s Trained Force positions are sea-based, and at 30 June 2014, 32 per cent of Navy’s Trained Force was at sea. The remaining positions are shore-based and provide members with respite from sea service, as well as enabling them to undertake advanced training, and to continue to work within Navy when injured, unfit or unable to go to sea. The recruitment and retention of personnel can impact directly on Navy’s ability to offer its members respite from sea service, an issue of particular importance during periods of high operational tempo.7

6. Navy’s workforce planning is primarily managed by the Navy People Branch. This branch is responsible for identifying Navy’s workforce requirements, developing Navy’s personnel policy, managing its employment categories, posting individual members to positions, and assisting individual members with managing their careers.

Audit objective and scope

7. The audit objective was to examine the effectiveness of Navy’s strategy for recruiting and retaining personnel with specialist skills. In particular, the ANAO assessed whether:

- this strategy supported Navy in maintaining and building military capability and carrying out its mission; and

- the plans and activities underpinning this strategy were effectively administered and implemented.

8. The high level criteria developed to assist in evaluating Navy’s performance were:

- Navy has conducted adequate workforce planning to identify personnel requirements including numbers and skills required to maintain and build military capability.

- Navy has suitable plans, policies and procedures in place to support its recruitment and retention of personnel with specialist skills.

- Navy has identified shortfalls in personnel with specialist skills, giving particular regard to Navy’s future capability, and is addressing these shortfalls.

- Navy’s recruitment and retention activities are supported by expert advice, research and analysis, legislative and procedural guidance, and training for staff involved.

- Navy monitors and evaluates the outcomes and cost effectiveness of its recruitment and retention strategies, policies and activities.

9. The audit included four employment category case studies: marine technicians; electronics technicians; aerospace engineering officers; and medical officers. As part of audit fieldwork, the ANAO interviewed personnel from the four selected employment categories to understand the issues affecting their employment within Navy.

Overall conclusion

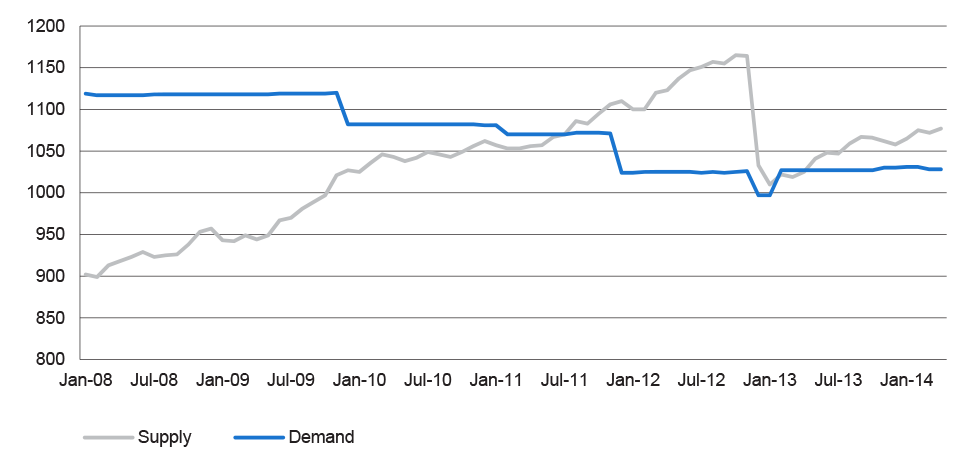

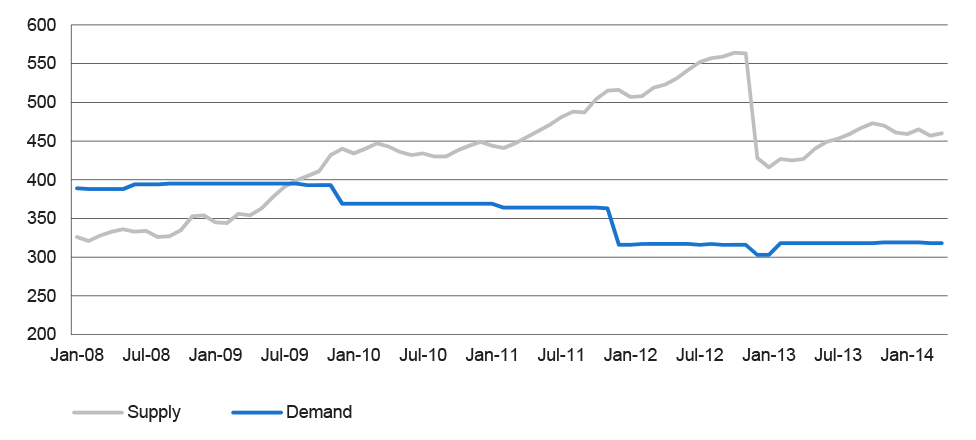

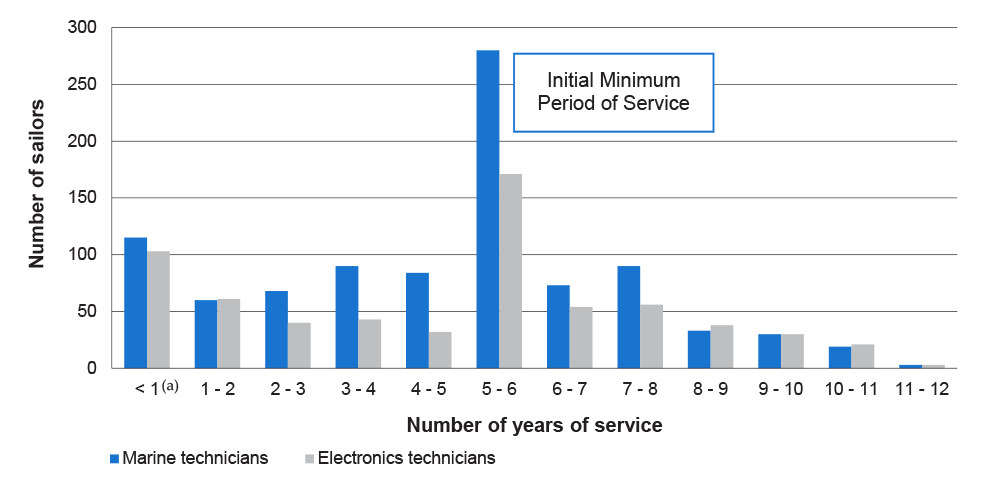

10. An effective workforce strategy involves aligning an organisation’s workforce with its current and future goals, taking into account its operating environment. To develop such a strategy, an organisation needs to identify its workforce requirements, and any gap between the workforce it has and the workforce it needs, and design initiatives to address this gap. After implementing these initiatives, it is important for an organisation to evaluate their impact, to help refine its overall workforce strategy and specific initiatives. A central consideration throughout this planning process is how best to attract skilled personnel and encourage them to stay; through remuneration, conditions of employment, providing interesting work, opportunities for promotion and growth, and a good working environment. For Navy, its workforce strategy and related initiatives must support the delivery of current and planned Navy capability in the context of an evolving labour market8, while it continues to carry out tasks directed by the government of the day.

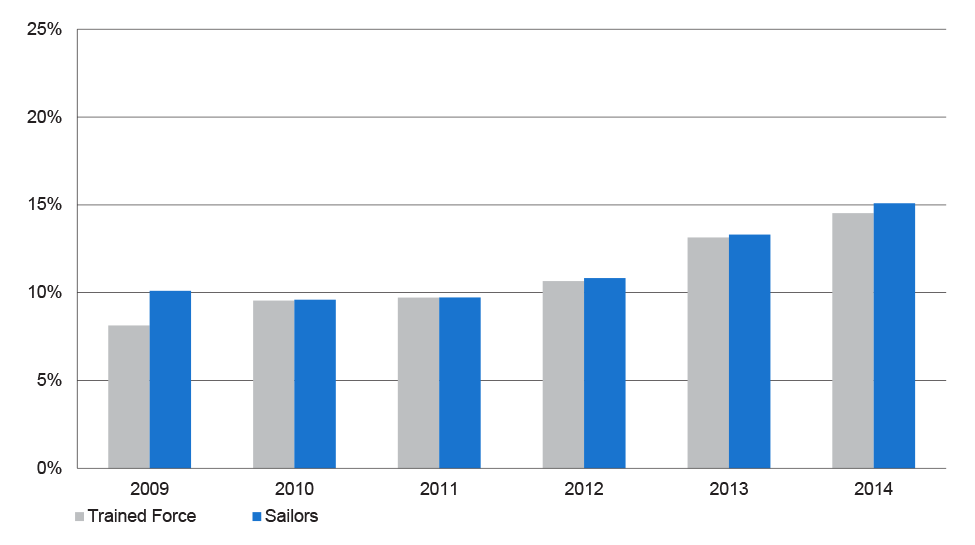

11. In its strategic planning, Navy has identified its key workforce risks and their implications for Navy capability. To address these risks Navy continues to adhere to its traditional ‘raise, train and sustain’ workforce strategy; has developed a broad range of workforce initiatives that complement its core approach; and is seeking to establish contemporary workforce management practices. However, long-standing personnel shortfalls in a number of ‘critical’ employment categories have persisted, and Navy has largely relied on retention bonuses as a short to medium-term retention strategy.

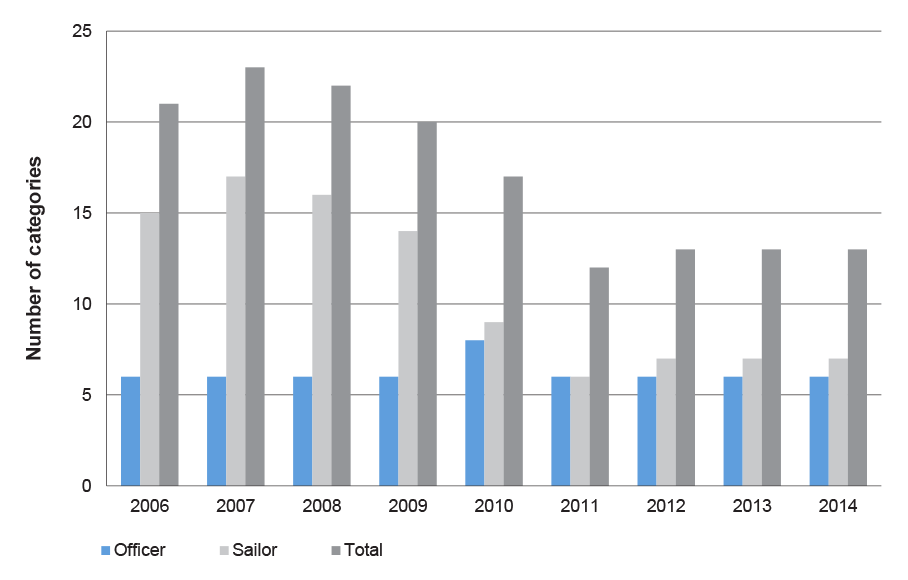

12. The number of Navy employment categories assessed9 by Defence as ‘critical’ has reduced from 23 in 2007 to 13 in 2014. Despite the overall reduction in the number of Navy critical employment categories, three of the remaining 13 critical categories have been critical for 15 years and Navy does not expect seven of these categories to recover within the next 10 years, including technical sailor, submariner and medical employment categories. The marine technician workforce is Navy’s largest employment category, possessing skills essential for operating Navy ships and submarines. This category continues to experience complex workforce issues that are difficult to remediate. Navy had a shortfall of some 461 marine technician sailors and submariners in June 2014, which was 26 per cent fewer than needed. While such workforce shortfalls may be manageable in the normal course of events, they expose Navy to significant risk in the event of unforseen or particularly heavy operational demands. The complex workforce issues include constraints affecting the timely transition of recruits to the Trained Force; a lack of meaningful shore-based jobs caused, in part, by the outsourcing of maintenance work to the private sector; and low levels of respite for personnel from ship-based duties. As a result of these issues many marine technicians leave the Navy earlier in their career than Navy would like.10

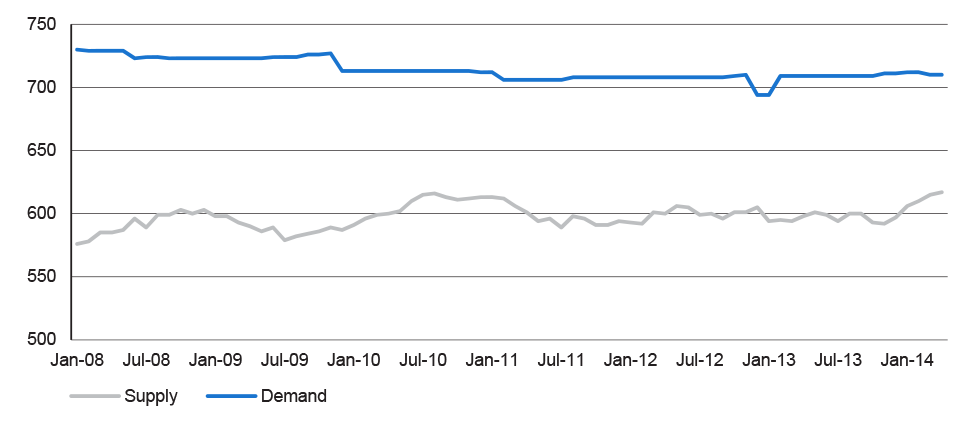

13. Navy’s principal workforce strategy is to ‘raise, train and sustain’ its workforce. This traditional strategy allows Navy to select from a large recruiting pool; develop a workforce with the skills it needs; and significantly, to fit its culture and often demanding operational environment. However, reliance on this strategy presents risks to the extent that trained personnel leave Navy early in their career11, and it limits Navy’s ability to quickly and flexibly respond to workforce shortfalls and changes in the wider labour market. In response to these risks, Navy’s strategic-level plans emphasise the need for Navy to increase workplace diversity and flexibility. This emphasis responds to the changing demographics and work preferences of the Australian population.

14. Navy has developed a broad range of workforce initiatives, some designed specifically to address workforce shortages in its critical employment categories. However, Navy’s record in following through to effectively implement these initiatives is variable. To date, Navy has primarily relied on initiatives that complement its ‘raise, train and sustain’ strategy, including: paying retention bonuses and other financial incentives; recruiting personnel with prior military experience to work in employment categories with significant workforce shortfalls12; and using Navy Reserves in continuous full time roles. Ongoing work is required for Navy to firmly establish a range of promising workforce management practices, including: providing the right training at the right time; more flexible approaches to managing individuals’ careers; more challenging work; a more flexible reward system; improving access to more flexible working arrangements; using civilian qualified personnel in the right roles; and improving workplace culture, leadership and relationships. This work is challenging, particularly when there is a high operational tempo, and changes to more traditional approaches can take time to bed-down and find acceptance. However, more flexible and tailored workforce management practices can help address the underlying causes of workforce shortfalls, particularly when the traditional approaches are not gaining sufficient traction.

15. Navy has recognised shortcomings in its approach to managing employment categories with significant workforce shortfalls. In 2013, Navy started developing workforce management plans for each employment category and providing human resource training for staff within Navy People Branch so that they have appropriate human resource management skills and competencies for the work they undertake.13 Consistent with this approach Navy should draw on external human resource professionals to help validate and confirm its thinking on its revised Workforce Plan due to be completed in 2015. Strengthened planning would also assist Navy to implement, monitor and evaluate workforce initiatives in a timely manner. Navy has not systematically assessed the impact of recruitment and retention initiatives to help shape its overall workforce strategy and improve the design of initiatives. Of particular note, Navy has not formally evaluated the impact of its retention bonuses despite making over 22 000 payments totalling some $311 million in the past decade.

16. In the period ahead, Navy will put several major new platforms into operation, including the Landing Helicopter Dock ships, Hobart-class Guided Missile Destroyers and helicopter fleets, which will require a sufficient number of personnel, often with new skills. To more effectively manage known risks relating to current capability, and risks in delivering planned capability, Navy should build on the progress it has made to date, with particular emphasis on the benefits offered by more contemporary workforce management strategies. Further progress will rely on active management by the Navy’s senior leadership. The ANAO has made two recommendations aimed at Navy: drawing on external human resource expertise to inform the development and implementation of its revised Workforce Plan; and evaluating the impact of retention bonuses on the Navy workforce to determine their future role within its overall workforce strategy.

Key findings by chapter

Recruitment and Retention Strategies and Performance (Chapter 2)

17. Two major reviews that have considered the causes and impact of workforce shortfalls in the key areas of engineering and technical sailor skills are the 2009 Strategic Review of Naval Engineering, and the 2011 Plan to Reform Support Ship Repair and Management Practices.14 These reviews identified a number of issues affecting Navy’s engineering and technical workforce, including a ‘hollowed-out’ Navy engineering function; a culture that placed short‐term operational missions above meeting asset engineering and maintenance standards; poor career management, job satisfaction and morale amongst technical sailors; and lack of respite from ship-based duties. To address these issues, the reviews made a number of recommendations and suggestions, including establishing an effective workforce planning system to ensure personnel have the appropriate skills, and providing more meaningful work for technical sailors.

18. ADF-wide and Navy strategies for recruitment and retention identify a number of common risks and propose similar potential solutions to address these risks, including broadening Navy’s recruitment intake and increasing diversity and flexibility in Navy’s workforce. The Navy Strategy 2012–17 sets out where Navy wants to be in 2017, how it plans to get there and the risks it will face along the way. The strategy identifies five enterprise risks including the ‘failure to attract, retain and generate a capable and integrated Navy workforce’. As such, Navy clearly identifies recruitment, retention and training as central to its ability to fulfil its obligations. The Navy Strategy lists 26 tasks15 aimed at addressing its workforce enterprise risk. Most of these tasks were due to be completed by August 2013, however only two of the 26 tasks were completed by this date, and ongoing activities are now being monitored through other arrangements. In addition to the Navy Strategy, Navy’s Workforce Plan 2007–17 is Navy’s key planning guidance for workforce management. It was released in February 2008 and a revised version is under development. Navy continues to face challenging workforce shortfalls and delays in promulgating a new workforce plan have meant that it has lacked an up-to-date edition of its primary workforce planning guidance.

19. Responsibility for implementing Navy’s recruitment strategies is shared between Defence Force Recruiting16 and Navy. Defence Force Recruiting manages the recruitment of ab initio recruits on behalf of the Services. Candidates are assessed by Defence Force Recruiting based on standards set by the Services for each job, with the final decision to enlist a candidate made by a uniformed Defence Force Recruiting staff member, or an Officer Selection Board composed of officers of the relevant Service. Navy sets ab initio recruitment targets for Defence Force Recruiting, and in the period following the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, Defence Force Recruiting has achieved close to 90 per cent of these targets. However, the most common time that recruits leave the Navy is within their first 90 days of service, and taking these separations into account, recruiting achievement dropped by an average of 8.5 per cent between 2008–09 and 2013–14. While recognising that military life is demanding and not for everyone, and that a proportion of recruits will decide to separate prior to the 90 day point, Defence could strengthen its analysis of the profile of personnel that leave Navy shortly after commencing service and the reasons they cite for departing. Analysis of this type could usefully inform a review of upstream recruitment and assessment processes, as a first step in minimising downstream losses shortly after personnel have been recruited.

20. Navy’s separation rates have generally improved over the last several years. The June 2014 overall separation rate of 8.4 per cent compared to a peak of 12.3 per cent in mid-2007. Despite this overall improvement certain employment categories and ranks still have high separation rates. For example, in June 2014 the separation rate for submariners was 17.3 per cent and the separation rates for middle sailor ranks, particularly Leading Seaman and Petty Officers, were higher than for other sailor and officer ranks. Further, following their first 90 days of service the next most common time for sailors to leave Navy is at the end of their Initial Minimum Period of Service, at which point they are relatively junior sailors. As a result of these factors, workforce pressures and shortfalls accrue within some of Navy’s critical employment categories at the supervisor level (Leading Seaman to Chief Petty Officer ranks).

21. Broadening Navy’s recruitment intake to include personnel with prior military and civilian experience has the potential to assist Navy address workforce shortages at supervisory ranks for officers and sailors. Navy has made good progress in implementing its Lateral Recruitment Program, which is intended to recruit personnel with prior military experience, and the skills and experience to work in employment categories with significant workforce shortfalls. During 2013–14, 13 per cent of Navy’s total recruits were laterally recruited including personnel: returning to Navy; transferring from the Navy Reserve or other Services; and personnel with prior foreign military service. However, Navy has been slow to progress its Mid-Career Entry Scheme. This scheme is designed to employ ab initio recruits who previously worked in civilian jobs, at a rank commensurate with their qualifications and experience, in shore-based positions.17 As at October 2014, Navy reported that only three sailors had been recruited through the scheme.

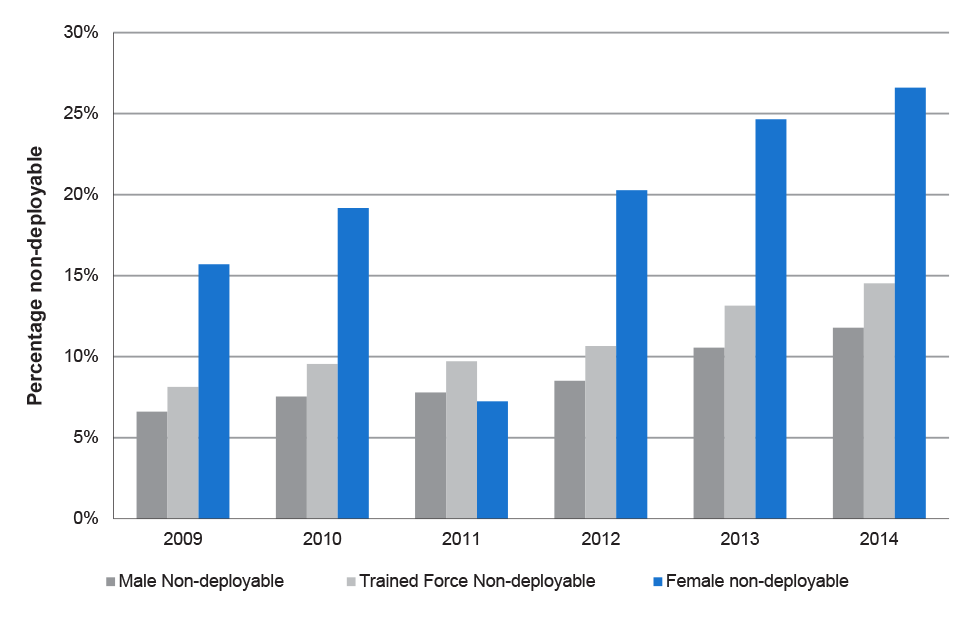

22. In recent years, Navy have pursued a number of initiatives aimed at increasing workforce diversity and flexibility, including increasing female participation and work-life balance. As at June 2014, the female participation rate for the Permanent Navy was 18.6 per cent and varied within employment categories from less than 10 per cent to greater than 50 per cent.18 Increasing female participation may create challenges for Navy if women are more likely to be unavailable for sea positions and deployments. As at June 2014, 26 per cent of women in Navy were classified as non-deployable compared to 12 per cent of men. In relation to work-life balance, a 2014 survey found that more Navy personnel were accessing both formal and informal flexible work arrangements compared with the previous year, however, their satisfaction with work-life balance remained below 50 per cent. In an environment characterised by workforce gaps and some traditional mindsets19, there has been a lack of guidance within Navy on how to apply flexible working arrangements. These issues highlight the need for Navy to effectively manage the tension that may arise between workplace diversity and flexibility, and its operational imperatives.

Workforce Planning and Category Management (Chapter 3)

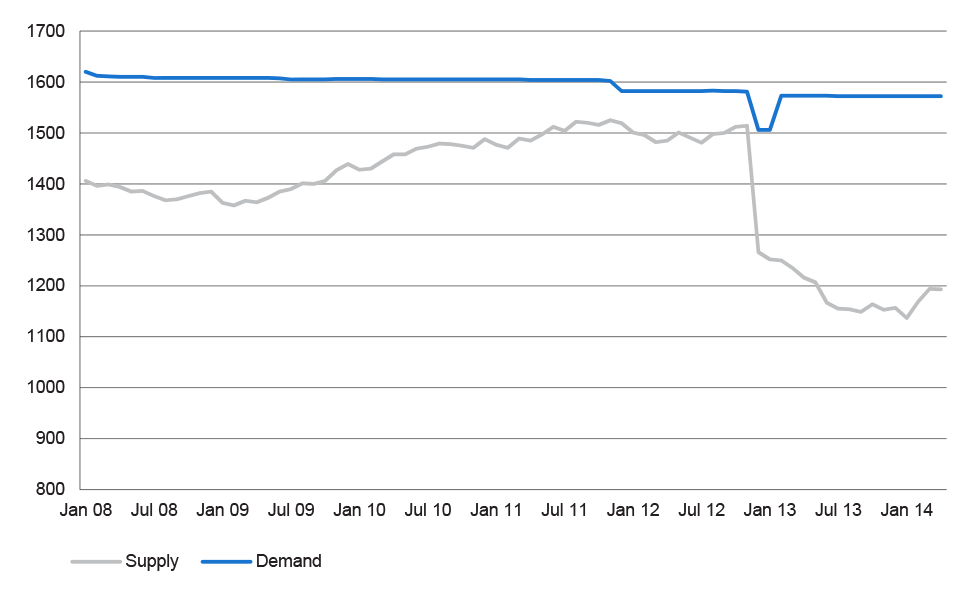

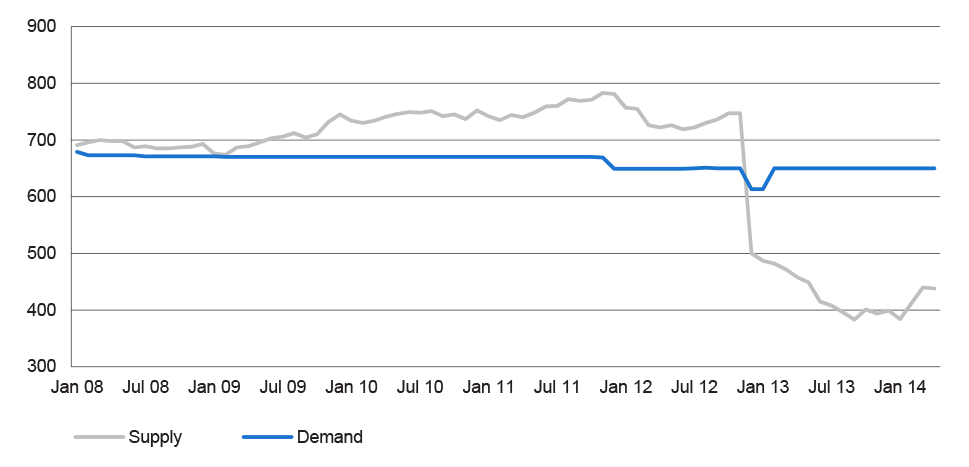

23. The aim of Navy workforce planning is to have a sufficient number of personnel within each employment category to form effective crews for each of its platforms, to allow Navy to meet its operational requirements. Navy workforce planning also aims to have a sufficient number of positions to support individual career advancement and provide shore respite for personnel. When modelling workforce supply and demand, Navy allocates 4.3 per cent of its positions for members of the Trained Force who are not contributing because they are either on long-term leave or unable to perform their role due to a medical condition (referred to as Personnel Contingency Margin (PCM)).20 In June 2014, Navy reported that 14.6 per cent of its Trained Force was unavailable to go to sea. There is a gap between Navy’s PCM and the proportion of its workforce unavailable to go to sea. This gap complicates Navy’s workforce requirement planning, particularly for critical employment categories with sea-based positions. At the time of the audit, Navy was reviewing its workforce requirement planning policy. Navy intends to make a number of changes to the policy in order to: apply different PCM rates for employment categories and ranks to better reflect actual rates; consider geographic stability for personnel when defining the workforce requirement and positions; and assess the sustainability of employment categories at different ranks.

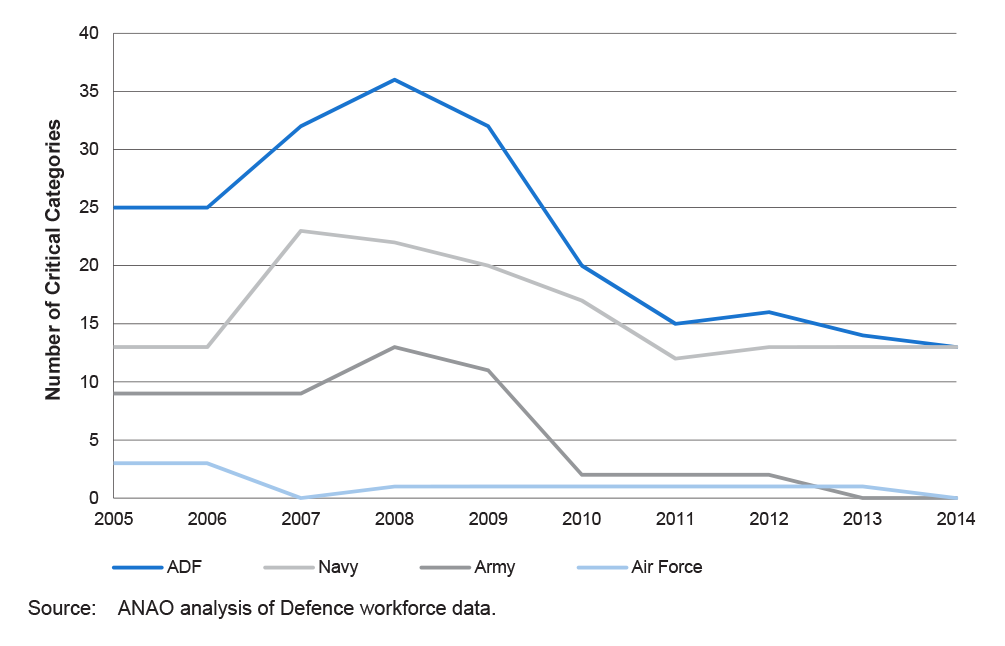

24. Defence uses a range of quantitative and qualitative measures to assess employment categories including the future supply of Navy assets and related demand for personnel. The classification21 of categories is considered annually by the Service Chiefs. Since 2005, Navy has had a significantly higher number of critical categories than Army or Air Force and in 2014 all 13 critical categories across the ADF were in Navy. Seven of the 13 critical categories are not expected to recover within the ten year forecasting period to 2024. However, it is difficult to predict the status of employment categories in 10 years’ time, particularly given the significant economic, labour market and industry changes which can occur over the long‐term.22

25. Navy assigns a category sponsor to manage each of its employment categories. The category sponsors engage regularly with personnel within the category on issues affecting their employment within Navy. Category sponsors have been primarily placed in their roles because of their experience and training within the category and, until recently, the sponsors may not have undertaken any human resource training to assist them in performing their role. A 2013 Navy People Branch initiative planned to provide some human resource training to these personnel, and at the time of the audit, additional work was required to progress the initiative. In light of the complex set of workforce challenges that Navy is dealing with, there is a need to apply human resource expertise to the task.23 This can be achieved by actively pursuing the development of human resource expertise within Navy People Branch, and by drawing on external human resource professionals with relevant experience to help inform the development and implementation of Navy’s revised Workforce Plan and associated initiatives.

26. In 2013, Navy developed category management plans with a view to creating a single authoritative document for managing employment categories. These plans document the broad range of remediation activities underway or planned for critical categories. The development of the category management plans is a positive step towards strengthened oversight and coordination of the remediation of critical categories. However, the plans generally do not establish performance measures and assessment techniques to gauge the effectiveness of the remediation activities, nor do they identify priority activities to help drive their implementation.

Employment Category Case Studies (Chapter 4)

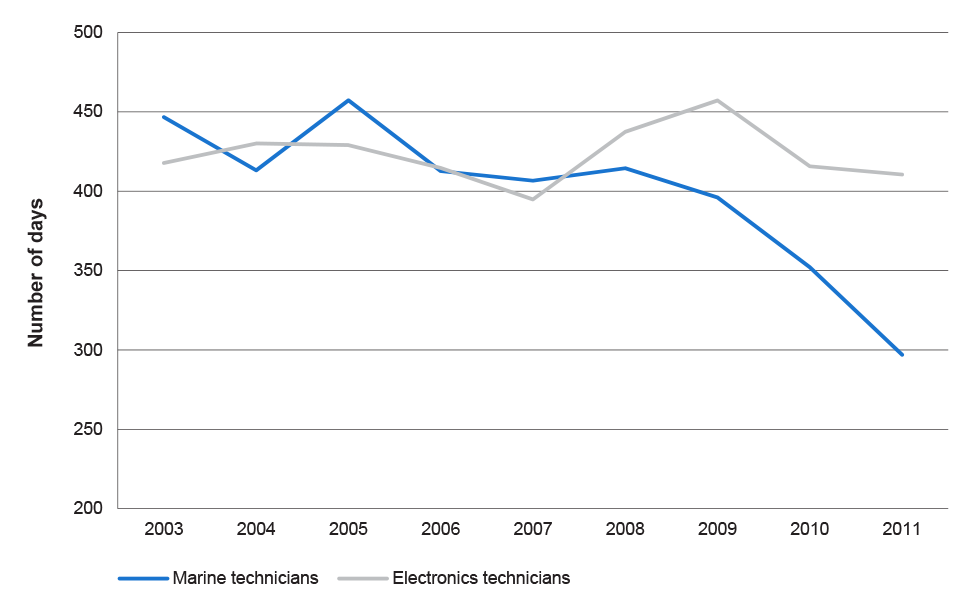

27. Navy’s two largest employment categories are marine technicians and electronics technicians. As at June 2014, the marine technician category was classified as ‘critical’, with a shortfall of some 370 trained marine technicians, or 23.5 per cent of the targeted workforce. At the same time, the electronics technician category was classified as ‘at-risk’.24 While Navy had four more electronics technicians than required, there were 96 fewer electronics technicians than required at more senior ranks. For both of these employment categories there has often been an excess of sailors at lower ranks to assist in addressing shortfalls at higher ranks subject to their promotion. However, many sailors have left Navy following their Initial Minimum Period of Service, and these departures have detracted from the effectiveness of Navy’s attempts to grow its workforce from within.

28. During the audit, technical sailors raised a number of workforce issues affecting their employment with Navy. These issues were similar to those identified by the 2009 Strategic Review of Naval Engineering.25 Technical sailors expressed dissatisfaction with the trade qualifications they received, and considered there was a need to pursue external opportunities to improve those qualifications. Other factors mentioned affecting their decision to depart or stay with Navy were a lack of meaningful shore-based jobs, low levels of respite26 and the payment of retention bonuses. The proportion of Navy’s workforce unavailable to go to sea has also increased over the last five years, from eight per cent in 2009 to 15 per cent in 2014. This has added to the pressure on technical sailors available to go to sea.

29. Navy’s initiatives to address shortfalls in its technical sailor workforce have included paying retention bonuses, managing the training pipeline and increasing lateral recruitment. To address dissatisfaction within its largest employment category, marine technicians, Navy is restructuring the training and career continuum for these sailors. In September 2010, Navy started using the Marine Technician 2010 Category Career Continuum (MT2010) as its framework for training new marine technician recruits. The aim of this continuum is to provide marine technicians with the right training at the right time; qualifications recognised within the civil maritime industry; and the trade skills needed to be able to undertake deeper maintenance tasks. Navy has experienced difficulties transitioning to MT2010 caused by a backlog in trainees; constraints in the sea training pipeline27; and inadequate resourcing of the project. In October 2014, Navy informed the ANAO that the new Chief of Navy had given directions to prioritise the training of junior marine technicians, including through the use of specific platforms for training purposes where consistent with government requirements. It is too early to determine the success of MT2010.

30. The ANAO also reviewed Navy’s management of two officer categories – aerospace engineers and medical officers. As at June 2014, there was a surplus of aerospace engineers, partly reflecting a reduced external demand for engineers in the broader economy. The category is also more readily amenable to flexible workplace conditions.28 On the other hand, Navy has had a significant shortage of medical officers for a considerable period of time, and as at 30 June 2014, Navy employed 29 per cent fewer medical officers than needed. While Defence has pursued initiatives to strengthen training opportunities, streamline career progression and financially reward medical officers, differences between remuneration available to ADF medical officers and civilian medical practitioners are likely to continue to pose a major challenge to remediating Navy’s medical officer workforce.

31. Over the past decade, Navy has relied heavily on retention bonuses to stem the separation of personnel in critical categories, having made over 22 000 retention bonus payments, with a total value of $311 million, to personnel within a range of employment categories. For example, there have been five rounds of retention bonuses specifically targeted at marine technicians and/or submariners in return for between one and two years of additional service; and four rounds of retention bonuses specifically targeted at electronics technicians or submariners in return for up to two years of additional service. While Navy has relied on retention bonuses to encourage personnel with critical skills to stay in the Navy workforce in the short to medium-term, their ongoing use has not resolved underlying workforce issues and there are mixed perspectives within Navy on their overall benefits and costs. Navy members emphasised the need to address the underlying workforce issues, which reflect deeper structural issues in terms of the work performed by technical sailors ashore, their timely transition to the Trained Force and low levels of respite. Navy has not formally evaluated the impact of its retention bonus schemes, and should do so to help determine their future role within its overall workforce strategy.

Summary of entity response

32. Defence’s covering letter in response to the proposed audit report is reproduced at Appendix 1. Defence’s summary response to the proposed audit report is set out below:

Defence thanks the ANAO for undertaking the Recruitment and Retention of Specialist Skills for the Navy audit.

Defence welcomes ANAO’s acknowledgement of the complexity of managing the recruitment and retention of Navy personnel, as well as the recognition of Defence’s work in improving in this area in the last few years.

Defence acknowledges the findings contained in the audit report and welcomes the Recommendations made by ANAO. Defence will also consider the feasibility of the suggestions made in the report.

Recommendations

|

Recommendation No.1 Paragraph 3.32 |

|

|

Recommendation No.2 Paragraph 4.80 |

To refine its workforce strategy, the ANAO recommends that Navy:

|

1. Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the Royal Australian Navy’s workforce and related workforce challenges. It also describes the audit objective, scope and approach.

Overview of the Navy workforce

1.1 The Royal Australian Navy (Navy) is the maritime arm of the Australian Defence Force (ADF). Its stated mission is ‘to fight and win at sea’ and its total budget for 2014–15 is $4.79 billion, which includes $1.86 billion in employee expenses.29 Navy’s importance to the defence of Australia was reinforced in the most recent Defence White Paper which stated that, as an island nation, ‘Australia’s geography requires a maritime strategy for deterring and defeating attacks against Australia’.30

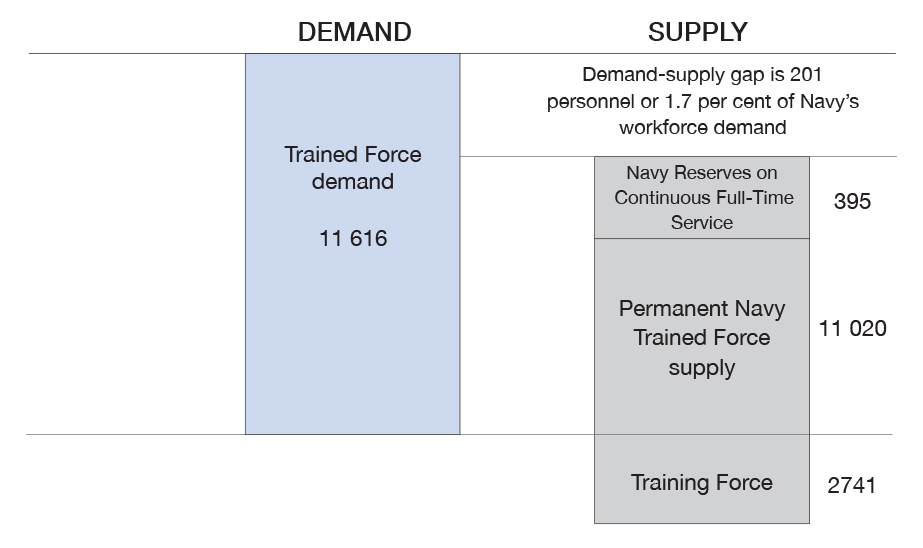

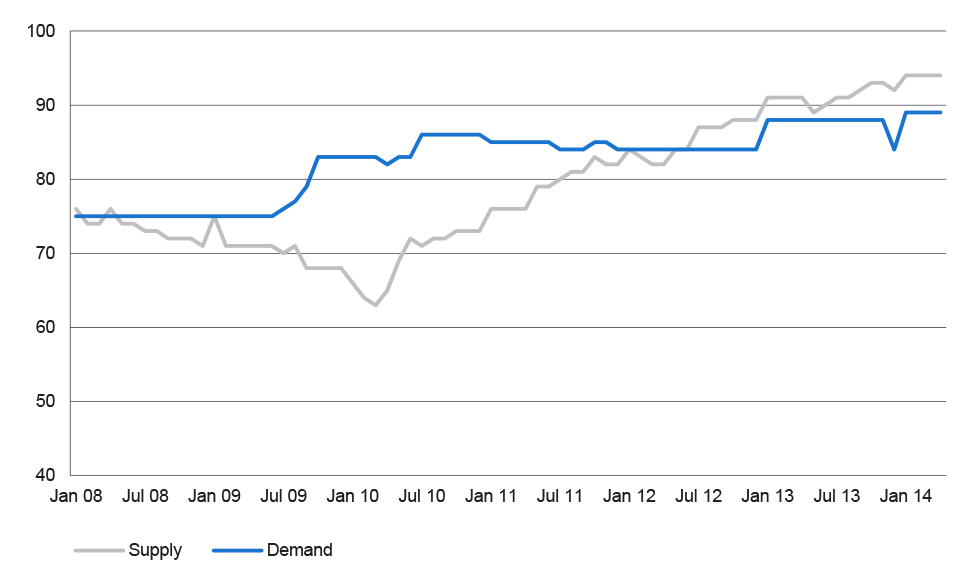

1.2 Navy’s workforce includes its Trained Force and Training Force. As at 30 June 2014, the Trained Force comprised 11 415 people and the Training Force 2741 people. At that time, Navy required a Trained Force of 11 616 people, which meant there was a shortfall of 201 trained personnel, or 1.7 per cent of Navy’s workforce demand. Navy’s Trained Force of 11 415 people included 11 020 members of the Permanent Navy and 395 Navy Reserves undertaking Continuous Full-time Service.31 Figure 1.1 shows Navy’s workforce demand and supply gap as at 30 June 2014.

Figure 1.1: Navy’s workforce demand and supply, 30 June 2014

Source: ANAO analysis of Navy Monthly Workforce Status Report, 30 June 2014.

Navy: a technological service

1.3 Navy’s surface ships, submarines, aircraft and other materiel assets are fundamental to its capability. In 2009, Navy’s Strategic Review of Naval Engineering described Navy as ‘fundamentally a technological service’, with its warfighting ability ‘critically dependent on the engineering design of its platforms and systems and the state of serviceability in which they are maintained’.32 Navy personnel operate and maintain these assets33, and it is therefore critical that Navy has a competent and committed workforce. Without the right personnel, Navy capability is reduced.34

1.4 Navy’s fleet consists of 52 sea vessels, including 14 different classes of warship, and 35 helicopters including three different types.35 To operate and maintain this fleet, Navy’s workforce comprises 60 employment groups or ‘categories’.36 These categories include engineers, technicians, warfare sailors and officers, medical personnel, logistics personnel, divers, pilots and others. Some positions within these categories require personnel to have platform specific qualifications and experience. Furthermore, Navy’s primary operational environment represents more than 12 per cent of the Earth’s surface, across which it conducts a wide range of operations including maritime patrol and interdiction, creating navigational charts, collecting and analysing intelligence, and providing humanitarian assistance, disaster relief and maritime search and rescue.

1.5 Navy is soon to transform its fleet. At the start of the audit, the Deputy Chief of Navy informed the ANAO:

Over the next six years Navy will undergo a significant capability transformation with the introduction of Landing Helicopter Dock (LHD) ships, the Hobart class Guided Missile Destroyers (DDG) and the MH-60R Seahawk helicopter … All of these systems form the basis of Navy’s contribution to the joint ADF capability and their successful introduction, while sustaining current capabilities at the level expected by Government, will be a challenge given Navy’s constrained workforce levels.37

1.6 Effective workforce planning is a prerequisite to delivering current capability, bringing new capabilities into service and maintaining their availability.

Raise, train, sustain

1.7 To generate its workforce Navy generally adheres to the traditional ‘raise, train, sustain’ principle, which describes the broader ADF’s preference to grow its workforce from the ground up. Most of Navy’s recruits are ab initio which means, that they do not have any prior military experience. Navy educates, trains and prepares these recruits for military service and the job they will do in their chosen employment category. These recruits may then be promoted through the ranks in accordance with their qualifications and experience.

1.8 Navy has a limited appetite for recognising qualifications and experience gained in the civilian world. If recruiting someone with prior workforce experience but no military experience, Navy mostly requires them to start at the bottom of the rank structure, undertake Navy education and training, and work their way up. If a recruit has recent military experience, gained either from a Navy38 or from one of the other Services, Navy may fast-track that person’s promotion through the ranks or recruit them into a higher rank.

1.9 Navy’s general reliance on growing its workforce from within presents it with both risks and opportunities. The relative lack of prerequisite skills required of these recruits allows Navy to select from a large recruiting pool. By training the recruits Navy can develop a workforce with the skills it needs, and to fit its culture, and often demanding operational environment. On the other hand, providing a comprehensive education and training program requires Navy to make a significant investment of both time and resources into its recruits. Furthermore, growing a workforce from the ground up limits Navy’s ability to quickly and flexibly respond to workforce shortfalls and changes in the wider labour market. Table 1.1 summarises some key differences between Defence’s military and civilian workforces, many of which stem from the employment context of the two workforces.

1.10 Training engineers, technicians and warfare personnel to operate and maintain complex military equipment takes years, and requires personnel to stay motivated while studying, learning on the job and sometimes undertaking jobs they do not like in order to reach a desired level of competence. As new and more complex platforms are introduced into Navy, the effective education and training of personnel in technical and warfare employment categories – already a challenge as discussed below – will continue to require attention.

Table 1.1: Key differences between Defence’s military and civilian workforces

|

Feature |

Military |

Civilian |

|

Workforce grown from within |

The military workforce grows its own leaders. There is very limited recruitment at middle and senior levels, and there are a limited number of Service transfers. |

Defence can recruit middle and senior level people from within the Australian Public Service (APS) or externally. The APS workforce can move freely between entities. |

|

Age Profiles: 18 to 60 Years |

The ADF’s age profile reflects that the majority of Service personnel are under the age of 30. The profile is characterised by youth. |

Defence’s APS age profile reflects that the majority of employees are older than 35. The profile is characterised by experience. |

|

Defined Career Structures |

There are well defined career structures in the Services. There are pathways to the top and within specialist streams. Time in rank, experience, skills and merit are key drivers. |

Career structures are less clearly defined within the APS. Time at level is not a key driver. The focus is on skills and merit. |

|

Career Management |

Career management is a shared responsibility between the Service and the individual. There is a need to balance the needs of the individual and organisation. |

While performance feedback is given, individuals are responsible for their own career and identifying promotion opportunities or moves at level. |

|

Initial Periods of Service |

There are clearly defined initial periods of obligations for officers and other ranks. |

Civilian employees are not bound to an initial contract period. |

Source: Defence Strategic Workforce Plan 2010–20.

Workforce shortfalls in some employment categories

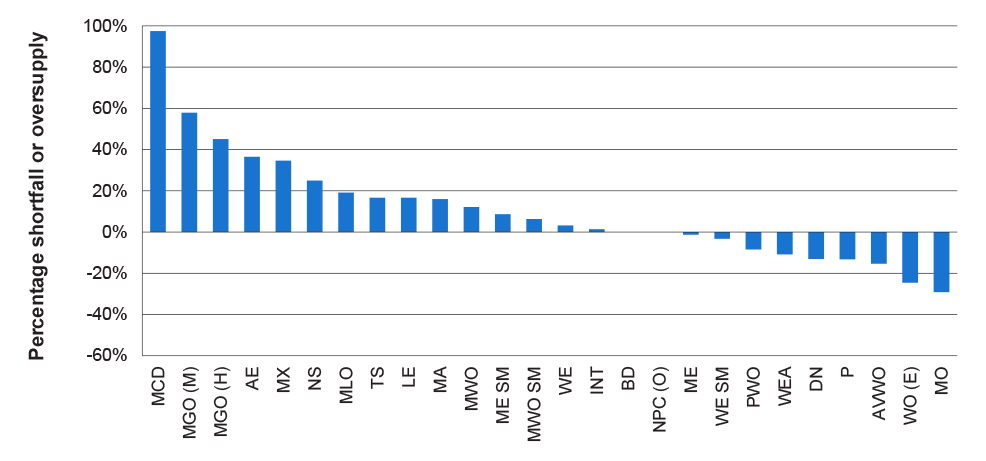

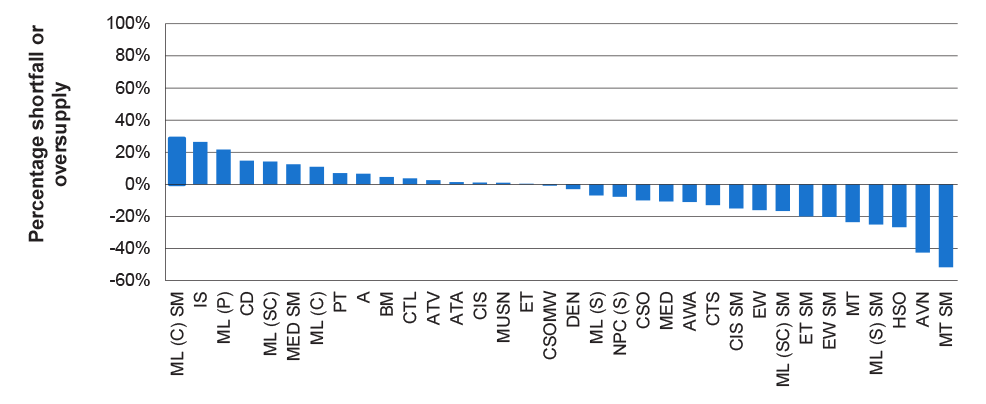

1.11 Navy has had difficulty in responding quickly and flexibly to some workforce shortfalls and some of its employment categories have experienced sustained shortfalls for over a decade. While Navy’s total workforce shortfall was 201 trained personnel as at 30 June 2014, this overall figure masks the extent of workforce shortages in particular employment categories and at certain ranks. Figure 1.2 and Figure 1.3 show that there was an oversupply of personnel in some employment categories and significant shortfalls in others.

1.12 At 30 June 2014, the marine technician (MT) employment category had a shortfall of some 370 sailors, which was 23.5 per cent fewer sailors than needed; and the medical officer (MO) category had a personnel shortfall of 29 per cent. Furthermore, in some categories workforce shortfalls occur at a particular rank or for personnel with a specific qualification. For example, as at 30 June 2014, the maritime warfare officer (MWO) category had a workforce oversupply of 12.1 per cent but at the Lieutenant Commander rank it had a shortfall of 49.0 per cent. At the same time, the electronics technician (ET) category had four more technicians than required, but at the Leading Seaman rank there was a shortfall of 21.1 per cent.

Figure 1.2: Workforce oversupply and shortfalls in officer employment categories, 30 June 2014

Source: Navy Monthly Workforce Status Report, 30 June 2014.

Note: See Table A.1 in Appendix 2 for an explanation of these 26 Navy officer employment categories.

Figure 1.3: Workforce oversupply and shortfalls in sailor employment categories, 30 June 2014

Source: Navy Monthly Workforce Status Report, 30 June 2014.

Note: See Table A.2 in Appendix 2 for an explanation of these 34 Navy sailor employment categories.

1.13 These workforce shortfalls within particular employment categories and at certain ranks represent significant gaps in Navy’s workforce. Navy does not have enough sailors at all ranks, engineering, medical and warfare personnel, and officers at the rank of Lieutenant-Commander. Defence acknowledged in its Strategic Workforce Plan 2010 that Navy has significant workforce ‘hollowness’39, which ‘may limit capability options’.40 This hollowness is a consequence of the difficulties Navy has had in recruiting, training and retaining personnel over the last decade.

Not a nine-to-five job

1.14 Navy personnel are primarily employed to perform a function at sea. Navy’s Australian Maritime Doctrine describes life at sea in the following terms:

inherently dangerous … [with] the effects of wind, water and hidden hazards often proving more deadly than any declared enemy … Operations are tiring, demanding and unforgiving, they are often characterised by long periods of surveillance and patrol followed by short bursts of [activity] … Even the biggest ships are relatively cramped and confined, and all living within them are subject to the continuous effects of weather and sea state. Constant monitoring of work practices is essential to lessen and manage the risks associated with fatigue.41

1.15 Forty per cent of Navy employment positions are sea-based, and at 30 June 2014, 32 per cent of Navy’s Trained Force was at sea. The remaining positions are shore-based and provide members with respite from sea service, as well as enabling them to undertake advanced training, and to continue to work within Navy when injured, unfit or unable to go to sea.

1.16 To ensure personnel obtain adequate respite over the course of a member’s career Navy tries to balance the number of sea and shore positions they are allocated. However, the recruitment and retention of personnel can impact directly on Navy’s ability to offer its members respite from sea service, an issue of particular importance during periods of high operational tempo.42 Navy considers all medically fit sailors as available for immediate posting as operational reliefs to replace a sailor returned to Australia on medical grounds or to undertake advanced training.

1.17 Navy shore positions are geographically dispersed. Navy has operational bases in Sydney, Perth, Darwin, Cairns and Nowra; training and support bases in Melbourne, Sydney, Canberra and Jervis Bay; and a presence in Brisbane, Hobart, Adelaide, Thursday Island and Dampier. While it is Navy’s policy intent to consider a member’s posting preferences, and to provide a degree of geographic stability and certainty as to where personnel are going next, this may not be possible due to workforce shortages and ongoing operational demands.

Navy workforce planning and recruitment

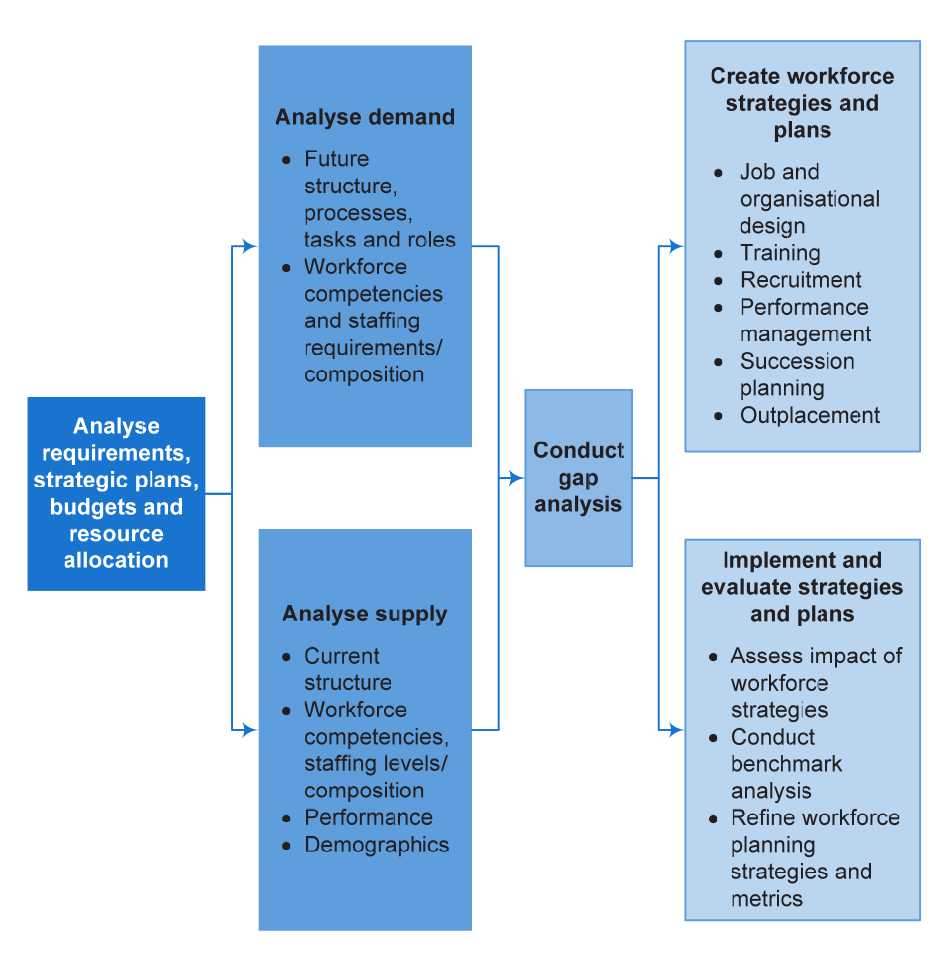

1.18 An effective workforce strategy involves aligning an organisation’s workforce with its current and future goals, taking into account the operating environment. To develop such a strategy an organisation needs to identify its workforce requirements and any gap between the workforce it has and the workforce it needs, in order to design initiatives to mitigate workforce shortfalls. Having implemented these workforce initiatives, it is important for an organisation to evaluate their impact to help refine its overall workforce strategy and specific initiatives. Figure 1.4 sets out a basic framework for workforce planning.

1.19 A central consideration throughout this planning process is how best to attract skilled personnel and encourage them to stay through remuneration, conditions of employment, providing interesting work, opportunities for promotion and growth, and good working relationships. For Navy workforce planning, a key external consideration is the wider labour market for technical skills, which can affect Navy’s ability to recruit and retain relevant personnel.43

Figure 1.4: A basic framework for workforce planning

Source: Workforce Planning Best Practices, United States Office of Personnel Management, 2011.

Navy People Branch

1.20 Navy’s workforce planning is primarily managed by the Navy People Branch. Figure 1.5 shows the organisational structure of Navy People Branch and describes the role of its five directorates.

Figure 1.5: Navy People Branch organisational chart

Source: ANAO analysis of Defence data.

1.21 The Directorate of Navy Workforce Requirements sets Navy’s demand for personnel by determining the number and type44 of positions needed in the Trained Force. Demand is largely based on the number of personnel required to crew Navy’s platforms45, and the career structure required to grow a sailor or officer through the ranks. The Directorate of Navy Workforce Management and the Navy People Career Management Agency manage the supply of personnel. The former directorate develops and implements plans for managing each of Navy’s employment categories, and is also responsible for addressing the causes of workforce shortfalls within some categories.46

1.22 Defence People Group supports Navy in managing its workforce. The Navy section of the Directorate of Workforce Modelling, Forecasting and Analysis in Defence People Group conducts analysis of the number of personnel Navy has, and the number of positons it needs to fill. This directorate also produces Navy’s Monthly Workforce Status Report.

Recruitment process

1.23 Navy does not manage the recruitment process for its ab initio recruits. This process is managed by Defence Force Recruiting, which is a public and private sector collaboration between Defence and Manpower Services (Australia). Defence informed the ANAO in October 2014 that:

Candidates are assessed in accordance with standards set by the Services for each job and the final decision on whether a candidate is enlisted is made by a uniformed [Defence Force Recruiting] staff member, or in the case of Officers, by an Officer Selection Board composed of Officers of the relevant Service.47

1.24 Responsibility for managing non-ab initio recruitment, such as personnel re-enlisting into one of the Services, is shared between Defence Force Recruiting and the Services.

Audit objective and scope

1.25 The objective of the audit was to examine the effectiveness of Navy’s strategy for recruiting and retaining personnel with specialist skills. In particular, the ANAO assessed whether:

- this strategy supported Navy in maintaining and building military capability and carrying out its mission; and

- the plans and activities underpinning this strategy were effectively administered and implemented.

1.26 For the purpose of this audit, specialist skilled personnel in the ADF included engineering officers, personnel performing technical trades and health professionals. The audit did not examine the training of these personnel other than to inform consideration of recruitment and retention strategies.

1.27 The ANAO developed the following high level criteria to assist in evaluating Navy’s performance:

- Navy has conducted adequate workforce planning to identify personnel requirements including numbers and skills required to maintain and build military capability.

- Navy has suitable plans, policies and procedures in place to support its recruitment and retention of personnel with specialist skills.

- Navy has identified shortfalls in personnel with specialist skills, giving particular regard to Navy’s future capability, and is addressing these shortfalls.

- Navy’s recruitment and retention activities are supported by expert advice, research and analysis, legislative and procedural guidance, and training for staff involved.

- Navy monitors and evaluates the outcomes and cost effectiveness of its recruitment and retention strategies, policies and activities.

1.28 In undertaking the audit, the audit team:

- reviewed relevant Australian Government, Defence and Navy policies, strategies, plans, manuals and reviews;

- analysed Navy’s workforce data;

- interviewed Defence and Navy staff responsible for managing recruitment and retention processes for personnel with specialist skills;

- analysed the implementation of recruitment and retention initiatives broadly across Navy, and specifically within four employment categories chosen by the ANAO in consultation with Navy. These categories were: electronics technicians, marine technicians, medical officers and aerospace engineering officers; and

- conducted fieldwork visits to a number of Navy bases to interview personnel from the four selected employment categories to understand the issues affecting their employment within Navy.

1.29 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $396 000.

Report structure

1.30 The remaining chapters of the report are set out in Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: Report structure

|

Chapters |

Overview |

|

2. Recruitment and Retention Strategies and Performance |

Examines Defence and Navy workforce strategies. It also provides an overview of recruitment and retention performance for Navy. |

|

3. Workforce Planning and Category Management |

Examines Navy’s workforce requirement planning and management of critical employment categories. |

|

4. Employment Category Case Studies |

Examines Navy’s approach to recruiting and retaining personnel in four employment categories. It also examines the payment of retention bonuses to personnel in critical employment categories. |

2. Recruitment and Retention Strategies and Performance

This chapter examines Defence and Navy workforce strategies. It also provides an overview of recruitment and retention performance for Navy.

Introduction

2.1 Navy’s principal recruitment and retention strategy is to ‘raise, train and sustain’ its workforce. This strategy allows Navy to select from a large recruiting pool, and to develop a workforce with the skills it needs, and to fit its culture, and often demanding operational environment. However, it also presents risks to the extent that trained personnel leave the Navy earlier than Navy would like, and it limits Navy’s ability to quickly and flexibly respond to workforce shortfalls and changes in the wider labour market. Navy has sought to address these risks with initiatives that complement its traditional raise, train, and sustain approach and other, more contemporary workforce management practices. Navy has designed some of these initiatives specifically to address workforce shortages in employment categories.

2.2 This chapter examines:

- major reviews addressing engineering and technical skills in Navy;

- Defence and Navy workforce strategies; and

- recruitment and retention performance for Navy.48

Major reviews addressing engineering and technical skills in Navy

2.3 In the past six years two major reviews have considered the causes and impact of shortfalls in Navy’s engineer and technical sailor workforce. The findings of these reviews provide important context for Defence and Navy workforce planning.

2.4 In February 2011, following the unavailability of Navy’s amphibious fleet in response to Cyclone Yasi, the then Government appointed an independent panel headed by Mr Paul Rizzo, which developed the July 2011 Plan to Reform Support Ship Repair and Management Practices. The Rizzo Plan found that:

The inadequate maintenance and sustainment practices have many causal factors. They include poor whole‐of‐life asset management, organisational complexity and blurred accountabilities, inadequate risk management, poor compliance and assurance, a ‘hollowed-out’ Navy engineering function, resource shortages in the System Program Office in DMO, and a culture that places the short‐term operational mission above the need for technical integrity.49

2.5 The Rizzo Plan recommended that: ‘Navy should establish an effective workforce planning system to ensure staff have the skills and experience required for complex sustainment roles’; and that the ‘[Defence Materiel Organisation] and Navy should develop an innovative and comprehensive through-life career plan for the recruitment and retention and development of their engineering talent’.50 As at March 2014, Defence had closed the first of these recommendations on the basis that the training and education needs of uniformed personnel in senior sustainment roles in the Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO) were included in training programs and captured in duty statements. In October 2014, Defence informed the ANAO that the implementation of the other recommendation was ‘on track’ following the return of a lead officer from secondment.

2.6 The Rizzo Plan drew in part on a 2009 internal Navy review of its engineering function. In May 2009, the Chief of Navy directed the Head Navy Engineering to conduct this review within the context of the New Generation Navy cultural reform program. The resultant Report on the Strategic Review of Naval Engineering emphasised that it is the skills, competence and commitment of the people who operate and maintain Navy’s platforms, particularly Navy’s engineering and technical personnel, who give Navy its edge.

2.7 The Strategic Review of Naval Engineering described the technical sailor community as being in crisis.51 It identified poor career management, job satisfaction and morale, as well as misaligned training as central to this problem. In particular:

- Navy was recruiting and training more technical sailors than its fleet could absorb, causing some trainees to become disillusioned with the long time it could take before they were posted to sea;

- shortages in qualified technical sailors and engineering officers were causing available personnel to be moved from one vacancy to another, with little regard for their professional development and, for technical sailors, this included being removed from shore postings with virtually no notice to fill positions at sea;

- there was a lack of meaningful jobs for technical sailors ashore, following the contracting out of platform maintenance and support functions; and

- there was a fundamental disconnect between the expectations and aspirations of technical sailors and the reality of their initial training, the skills they required at sea and in their employment ashore.

2.8 One of the inputs to the Strategic Review of Naval Engineering was Navy’s Project Engineering 2024. This project discussed the changing career attitudes of junior engineering officers, and suggested that generational considerations need to be factored into Navy’s approach to workforce planning:

The reality is that this generation of junior officers comes from a decreasing employment pool with different attitudes to long-term careers and a different perspective on loyalty and leadership - they expect loyalty from and to be highly valued by their employers. Alternative employment is readily available and they feel well qualified to take on a range of jobs, not necessarily engineering based, anywhere in the world. In short, if their Navy career does not provide interesting work, the contemporary service lifestyle is not sufficient incentive to stay. The challenge therefore is to provide meaningful employment…52

Defence and Navy workforce strategies

2.9 Defence People Group develops a Defence-wide strategic workforce plan and the individual Services develop their own strategies and plans, taking into account government policy settings.

Defence White Paper 2013

2.10 The Defence White Paper 2013 stated that:

Generating the required Navy workforce and training people in core skills to professional standards across all future capabilities will continue to be key challenges. In the medium-term, the Navy will address shortages in some supervisory ranks through increased emphasis on lateral recruitment, direct entry specialists and Reserves. Attention will be focused on growing an inclusive and diverse workforce as part of the New Generation Navy program. … Attracting people with diverse talents from across the Australian community will assist the Navy to operate at peak performance to achieve maximum capability delivery.53

Defence Strategic Workforce Plan 2010–20

2.11 The Defence Strategic Workforce Plan 2010–20 outlines Defence’s approach to workforce planning in support of the Defence White Paper 2009 and Defence’s Strategic Reform Program.54 The plan identifies a number of workforce challenges facing the ADF, which include:

- increasing the diversity of the ADF’s workforce;

- balancing youth and experience within the ADF’s workforce;

- effectively competing for recruits with other industries; and

- retaining skilled staff within the ADF.

2.12 The Strategic Workforce Plan notes that the ADF needs to: focus on retaining Defence’s key talent rather than simply monitoring separation rates; improve the structural sustainability of a number of employment categories; and address the significant issue of personnel leaving en masse at specific points in their military career.55

Navy Strategy 2012–17

2.13 The Navy Strategy 2012–17 sets out where Navy wants to be in 2017, how it plans to get there and the risks it will face along the way. The strategy identifies five enterprise risks. Enterprise Risk 3 is the ‘failure to attract, retain and generate a capable and integrated Navy workforce’.56 As such, Navy clearly identifies recruitment, retention and training as central to its ability to fulfil its obligations.

2.14 To address Enterprise Risk 3, the then Chief of Navy tasked the Deputy Chief of Navy with two programs: ‘Attract the workforce’ and ‘Retain the workforce’. An August 2013 report to the Chief of Navy Senior Advisory Committee (CNSAC) stated that these two programs were being coordinated by the Director-General Navy People, and the Program Director of New Generation Navy.

2.15 CNSAC receives regular reports on the status of Enterprise Risk 3, including an assessment of Navy’s ability to ‘attract the workforce’ and ‘retain the workforce’. CNSAC members are also provided a quarterly Navy People Report, which includes information on personnel demand and supply, separation rates, workforce health including gender participation, leave balances and training, and the status of employment categories classified as critical. These reports discuss Navy’s efforts to attract and retain the workforce and related issues receive significant attention at CNSAC. However, there was no evidence of Navy managing a coordinated set of workforce initiatives through the ‘Attract the workforce’ and ‘Retain the workforce’ programs.

2.16 The Navy Strategy 2012–17 also includes a Navy Task List 2012–13, with 83 tasks that would put Navy on track to achieving its goal. Twenty-six of these tasks address Enterprise Risk 3, including lateral recruitment of personnel with prior military experience, mid-career entry for experienced recruits with no prior military experience, payment of retention bonuses to Marine Technicians, and providing more flexible work arrangements. The Navy Strategy Executive (the area within Navy that provides secretariat support to the CNSAC) was responsible for monitoring the delivery of initiatives under the Navy Strategy 2012–17. However, as of August 2013, only two of the 26 tasks to address Enterprise Risk 3 were completed, even though 18 were due to be completed by that date. Since that time Navy has discontinued the Task List and ongoing activities are now being monitored through other arrangements.

2.17 The Navy Strategy 2012–17 reiterates the challenge identified in the Defence Strategic Workforce Plan to introduce more flexibility and diversity into Navy’s workforce, stating that:

In 2017, Navy will be characterised by a workforce of permanent or part time uniformed and civilian staff who have the skills, leadership and resilience to deliver Navy’s mission.57

2.18 The Navy Strategy also emphasises that while Navy may not be able to compete for recruits on remuneration, it can offer other incentives. It states that:

despite the fact that we will never be able to offer the remuneration of our competitors, we need to highlight our advantages over our workforce competitors, especially esprit-de-corps, leadership, excitement and the contribution that each one of our people makes to our nation.58

2.19 Navy is currently developing a revised Navy Strategy for the period 2014–19. It is due to be signed off by the Chief of Navy by early 2015.

Navy Workforce Plan 2007–17

2.20 Navy’s Workforce Plan 2007–17, released in February 2008, provides a ‘summary of workforce issues, goals and initiatives that affect capability delivery’. The plan summarises the major concerns for Navy’s workforce:

Navy continues to face a range of internal and external threats and challenges in terms of its ability to meet current and future workforce and capability requirements. Separation and undermanning are at high levels. For many reasons our recruiting targets are not being achieved, especially with respect to the perilous and critical categories.59

2.21 The Workforce Plan identifies Navy’s key workforce risks and mitigation strategies. Of the risks identified, Navy assessed the ongoing workforce shortages experienced by some employment categories as an ‘extreme’ risk. These shortfalls are identified as ‘an enduring risk as it is not sustainable to conduct business under current workforce pressures’.60 Other identified workforce risks include: lack of rigour in managing Navy Reserve and civilian staff; workforce requirements exceeding supply and funding; crew size and associated shore support for Navy’s new ships being inadequate; and poor workforce planning. The initiatives and activities listed in the workforce plan to mitigate the identified risks include:

- Review employment category structures to improve efficiency and prioritise positions within Navy workforce.

- Enhance the capability of the Navy Reserve and optimise the use of the civilian workforce.

- Develop initiatives to align demand and supply within employment categories, and improve monitoring and reporting of outcomes.

- Improve workforce planning including human resource training for staff, benchmark Navy’s workforce planning practices against public and private organisations, and improve workforce planning tools and metrics.

2.22 The Navy Workforce and People Committee endorsed the Workforce Plan and was assigned responsibility for monitoring achievements against its strategic goals, actions and initiatives. Further, the plan notes that:

Future stages in the development of a [Navy Workforce Plan] risk management framework will involve ‘closing the loop’ through formal assessment of the effects of risk mitigation initiatives, as well as the development of quantitative tools that will link workforce outcomes to [Navy] operating capabilities.61

2.23 In October 2014, Defence informed the ANAO that:

The Navy Capability Committee (NCC) has subsumed the Navy Workforce and People Committee. [The NCC] receives and considers updates on the state of Navy’s workforce as a standing agenda item prior to this information being presented to [CNSAC]. The NCC also considers and amends or endorses all significant Navy workforce initiatives. This includes annual workforce reports for each Navy community … as well as changes to [employment] category structures and training arrangements.

2.24 Part 3 of the Navy Workforce Plan 2007–17 is the Navy Workforce Supply Management Plan. This part of the plan includes an extensive list of risk mitigation initiatives, as were current in 2008, such as the Sea Change Workforce Renewal Projects. However, the Supply Management Plan does not list any measures which could link recovery of workforce shortfalls to mitigation initiatives. In October 2014, Navy informed the ANAO about the achievements of the Sea Change Projects, including changes to crewing arrangements to provide geographic stability for members, and improved career management support for members.

Development of a new Navy Workforce Plan

2.25 As mentioned in paragraph 2.20, Navy released the current Navy Workforce Plan in 2008. Navy has subsequently experienced significant change. Two Defence White Papers, the Navy Strategic Plan 2010–15, the Navy Strategy 2012–17, and two iterations of the New Generation Navy cultural reform program have all been released in the past six years. Following an initial planned released date of December 2012, later revised to March 2013, a new Navy Workforce Plan is now expected to be finalised by early 2015.62 Navy continues to face challenging workforce shortfalls, and delays in promulgating a new workforce plan have meant that it has lacked an up-to-date edition of its key planning product for providing ‘clear guidance on key workforce management areas that require an active focus … to meet future capability requirements’.63 Providing contemporary guidance is an essential prerequisite for maintaining focus and momentum within Navy on its ongoing workforce challenges.64

New Generation Navy

2.26 The then Chief of Navy launched the New Generation Navy strategy in April 2009. The strategy detailed ten signature behaviours65 intended to fundamentally reform Navy leadership, training, culture and structure. New Generation Navy was also designed to address ‘significant recruitment and retention challenges’, and to ‘close the gap between … [the] current workforce and the workforce to meet the requirements of future capabilities’.66 The challenges to be overcome were:

- constraints preventing Navy from more readily recruiting laterally;

- consistent failure to meet recruitment targets;

- the rate of personnel leaving in the first year or at the completion of their Initial Minimum Period of Service; and

- significant shortfalls in particular employment categories including marine technicians, electronics technicians, medical officers and pilots.

2.27 Navy grouped the New Generation Navy 2009 initiatives and activities under the themes ‘Lead’, ‘Raise’, ‘Train’, and ‘Sustain’. These initiatives and activities were intended to change Navy culture from one which ‘operates effectively at sea and through best endeavours, stretches resources through a can-do attitude, puts platforms before people and burns the good will of Navy personnel’ to one that ‘makes and executes strategic decisions, supports people during and beyond their service and empowers them to make a respected contribution’.67 Many of the initiatives and activities directly targeted the recruitment and retention of Navy’s workforce (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1: New Generation Navy 2009, initiatives targeting the recruitment and retention of Navy’s workforce

|

Priority |

Recommendation |

|

Theme 1: Lead |

|

|

Align promotion and advancement of leaders with New Generation Navy |

Selection criteria and promotion processes to reinforce and recognise New Generation Navy cultural values and behaviours. |

|

Modernise our customs and strengthen Navy heritage |

Modify existing customs and traditions to reinforce what it means to serve in today’s Navy. |

|

Theme 2: Raise |

|

|

Improve responsiveness to those re-joining Navy |

Remove cultural and systemic barriers to attract and encourage former Navy personnel to re-join. |

|

Recruit more people, send them to sea earlier |

Focus ADF recruitment and initial Navy training on enabling more Navy people to serve at sea earlier. |

|

Ensure participation in Navy reflects Australian diversity |

Adapt Navy culture to provide an environment supportive and representative of the diverse needs and make-up of Australian society. |

|

Theme 3: Train |

|

|

Reform category training and job roles |

Switch focus of initial and category training from the civilian qualification-focused career progression to operator competencies at sea. |

|

Continue Plan Train initiatives |

Continue Plan Train as a medium term initiative to facilitate a training led recovery of critical categories that rely heavily on platform based training. |

|

Manage careers more flexibly |

Provide flexible career models to respond to the life and career ‘ages and stages’ needs of the workforce. |

|

Theme 4: Sustain |

|

|

Deliver people focused work practices |

Achieve an appropriate balance between operational and ‘home/personnel’ tempo. |

|

Provide supportive employment conditions and increase family connection |

Improve the experience of the non-financial employment conditions and increase Navy’s connection to families. |

|

Review financial employment conditions |

Financial conditions match or remain competitive with equivalent job roles in relevant industries. |

Source: New Generation Navy, April 2009, pp. 16–18.

2.28 In February 2013, in response to changes within Navy and externally since the program’s launch in 2009, the then Chief of Navy released a revised New Generation Navy strategy to guide Navy through to 2017. The revised strategy represents a significant departure from the original. It groups initiatives and activities under three pillars:

- warfighting and seaworthiness: trusted to defend;

- improvement and accountability: proven to deliver; and

- values-based, people-centred leadership: respectful always.

2.29 The revised strategy contained fewer specific activities and initiatives directly targeting the recruitment and retention of Navy’s workforce, and only one such initiative was to be delivered as part of the revised strategy (Table 2.2).68

Summary—workforce strategies

2.30 Defence and Navy strategies have consistently identified workforce planning risks and acknowledged the need for timely and ongoing action to mitigate them. There have also been some consistent themes throughout the range of Defence and Navy plans that address workforce planning, including the benefits of innovation and cultural change. The plans emphasise the need to increase workplace diversity and flexibility, including through lateral recruitment, mid-career entry and amendments to personnel policies.

Table 2.2: New Generation Navy 2013, initiatives targeting the recruitment and retention of Navy’s workforce

|

Initiative |

Outcome |

|

To be delivered by New Generation Navy 2013: |

|

|

Embed people focused work practices |

A balanced tempo of work improves the health, wellbeing and effectiveness of Navy people and sustains the Navy workforce. |

|

To be supported by New Generation Navy 2013: |

|

|

Increase diversity and flexibility |

Navy optimises available resources by having a diverse and flexibly managed workforce. |

|

To be monitored by New Generation Navy 2013: |

|

|

Develop leadership capability |

Navy leaders enable people to be the best that they can. |

|

Improve responsiveness to those re-joining Navy |

Improved ability to meet Navy capability through a larger trained force. |

|

Modernise customs and traditions |

Customs and traditions appeal to and connect the diverse Navy workforce. |

Source: New Generation Navy, February 2013, pp. 13–20.

Overview of recruitment and retention performance for Navy

2.31 Every year, Navy People Branch provides Defence Force Recruiting69 with a targeted number of ab initio recruits for each employment category. The branch consults widely in determining the number of ab initio recruits needed, including with the commanders of Navy’s surface and submarine fleets. This process is intended to align Navy’s recruitment targets with its personnel supply targets, training pipelines and employment category plans.

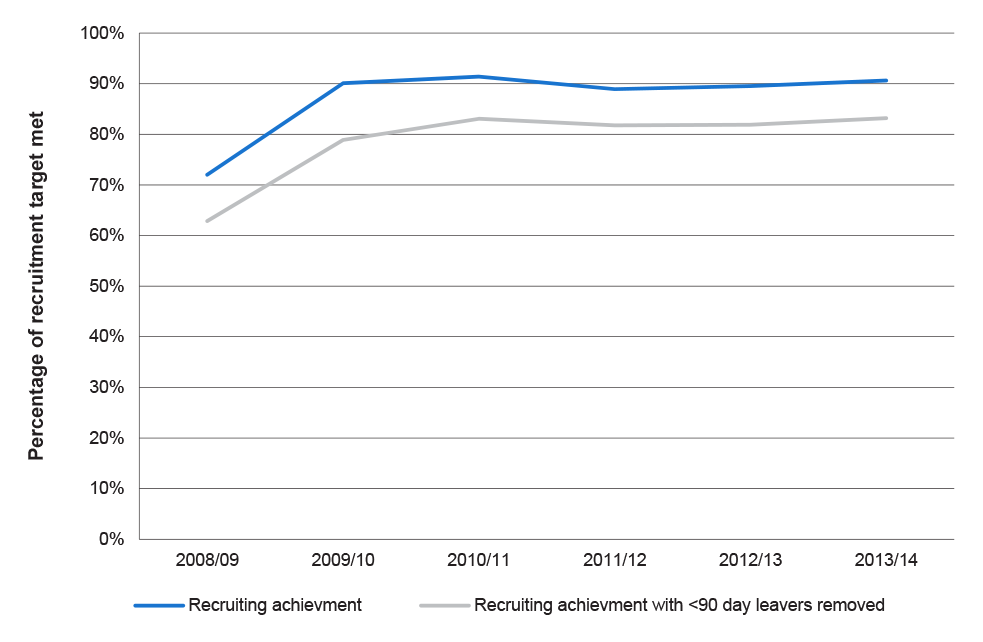

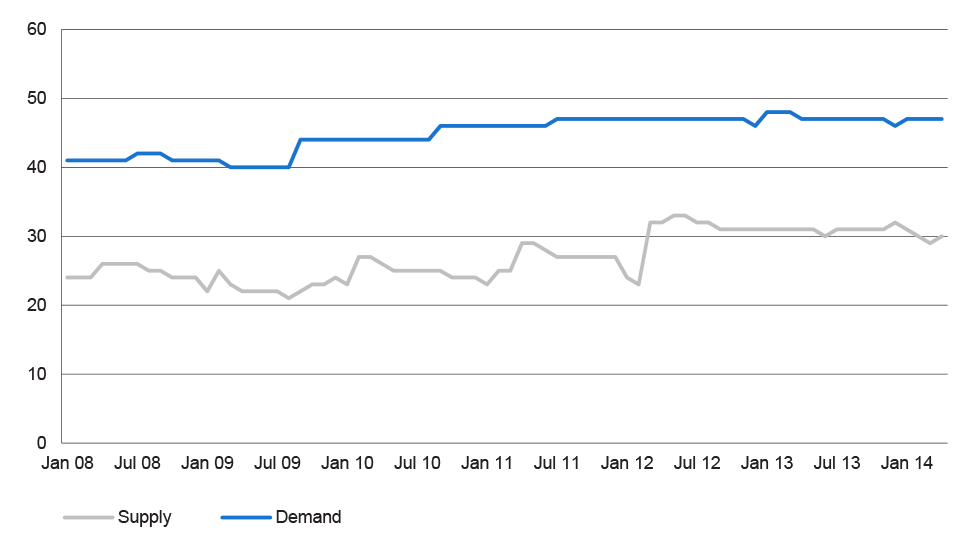

2.32 Defence Force Recruiting has recruited close to 90 per cent of the target number of recruits set for it by Navy since 2009.70 However, once recruited, personnel can opt to discharge from Navy within their first three months of service without penalty.71 Figure 2.1 shows that recruiting achievement dropped by an average of 8.5 per cent between 2008-09 and 2013-14 when separations within the first 90 days of service are taken into account.

Figure 2.1: Recruiting achievement between 2008 and 2014

Source: ANAO analysis of Navy workforce data.

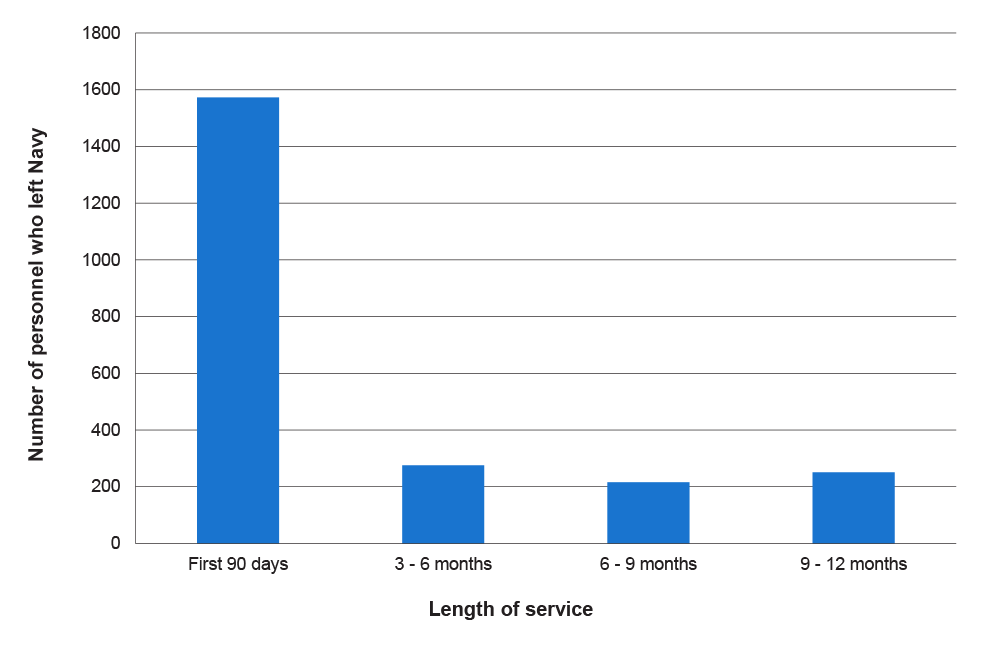

2.33 Figure 2.2 shows the number of personnel who left Navy within their first year of service, between 2002 and 2014. The most common time for a recruit to leave Navy is within their first 90 days of service. Ten per cent of all personnel recruited into Navy since 2002 left within the first 90 days of service.

2.34 The Defence Strategic Workforce Plan attributes the propensity to leave within the first year of military service to a poor fit between the individual and the organisation. Military life is very different to civilian life, it is challenging, often physically demanding, and not for everyone.72 For this reason the Strategic Workforce Plan recognises the need to continually validate recruit quality measures and their ability to predict success.

Figure 2.2: Number of personnel who left Navy within the first year of service, 2002–2014

Source: ANAO analysis of Navy workforce data.

2.35 While acknowledging that not all recruits will be well-suited to Navy life, Navy itself recognises the risks of recruiting personnel simply to achieve targets:

To achieve recruiting targets, over the last couple of years Navy have been accepting a larger number of candidates within the lower range in the order of merit for recommended applicants, where candidates’ motivation/ commitment/knowledge of Navy is at a lower level.73

2.36 The ANAO sought Defence advice on analysis undertaken in relation to personnel who leave Navy within their first 90 days, which may be used in assessing recruitment processes. In October 2014, Defence informed the ANAO that:

Defence People Group (DPG) does not conduct analysis in relation to leavers in the first 90 days as the only information available … is limited to age and gender; it does not provide why they elected to discharge. DPG understands that reports are raised upon intake graduation which lists those who discharged and reasons why. This information is sent to [the Director-General Navy People, Commander Training in Navy and Defence Force Recruitment].

2.37 Defence could strengthen its analysis of the profile of personnel that leave Navy shortly after commencing service, and the reasons they cite for departing. Analysis of this type could usefully inform a review of upstream recruitment and assessment processes, as a first step in minimising downstream losses shortly after personnel have been recruited.

Recruitment pathways including lateral recruitment

2.38 There are two main pathways for recruitment into Navy:

- recruitment for personnel entering into Navy for the first time, without any prior military experience. This group includes personnel recruited by direct entry, from the Australian Defence Force Academy and undergraduate officer entry.

- Lateral recruitment74 for personnel returning to Navy from civilian life; transferring from the Navy Reserve, Army or Air Force; or personnel with prior foreign military service.

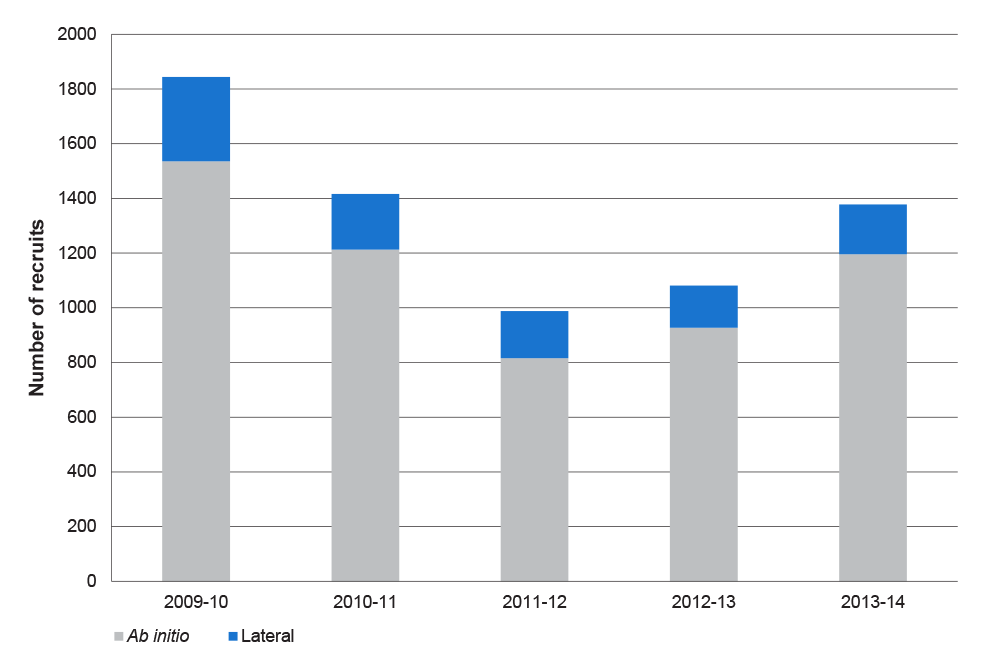

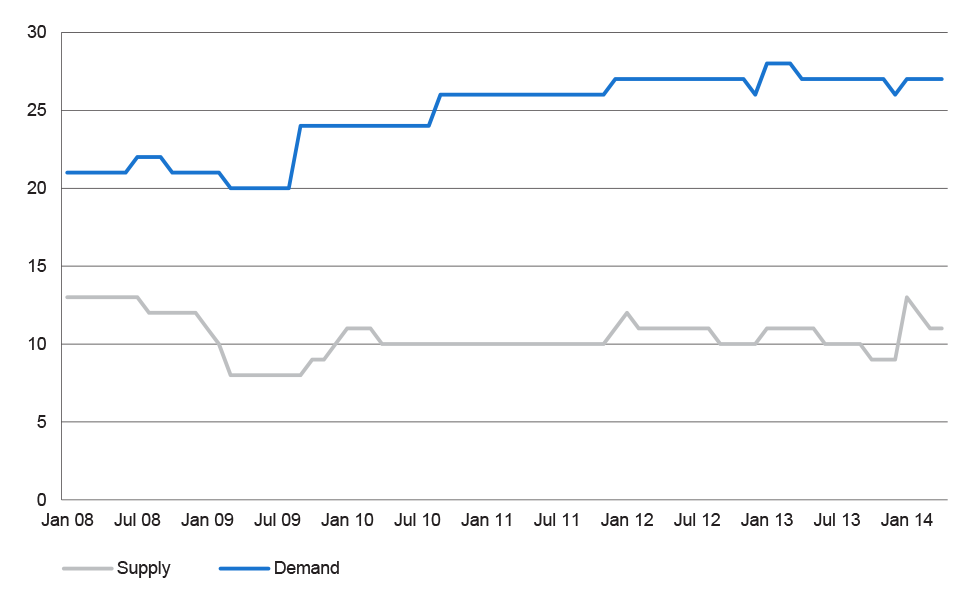

2.39 Figure 2.3 shows the number of ab initio and lateral recruits accepted into Navy between 2009–10 and 2013–14. The number of lateral entries as a proportion of Navy’s total recruits has remained relatively stable over the past five years. In 2013–14 the large majority of recruits were ab initio, however 182 or 13 per cent were recruited laterally, which represents an important contribution towards meeting workforce requirements. Lateral recruitment enables Navy to address workforce hollowness in a more immediate fashion than ab initio recruitment, and was identified in the Navy Strategy 2012–17 as a key initiative to address workforce shortfalls.

Figure 2.3: Number of and lateral Navy recruits, 2009–10 to 2013–14

Source: Navy workforce statistics.

Note: The figures for lateral recruits include in-service transfers, for example, sailors transferring to officer categories.

2.40 Table 2.3 below outlines the achievement of targets for lateral and in-service75 recruitment, compared to ab initio recruitment, for officers and sailors in 2013–14. The achievement against targets for lateral and in-service recruitment is lower than for ab initio recruitment for both sailors and officers.

Table 2.3: Achievement of recruitment targets by type, 2013–14

|

Recruitment type |

Percentage of target achieved |

|

Ab initio—Sailors |

94% |

|

Ab initio—Officers |

86% |

|

Lateral (including re-entry) and In-Service—Sailors |

79% |

|

Lateral (including re-entry) and In-Service—Officers |

59% |

Source: Navy Recruiting Progress 2013-14.

Re-joining the Navy