Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of the National Rental Affordability Scheme

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to examine the effectiveness of the Department of Social Services' (DSS) administration of the National Rental Affordability Scheme (NRAS), with a focus on the assessment of applications, and management of reserved allocations.

Auditor-General’s foreword

The issue of rental affordability featured prominently in the 2007 Federal Election and was a priority for the incoming Government. Subsequently the elected Government commenced planning for the implementation of a new affordable housing initiative. The National Rental Affordability Scheme (NRAS, or the scheme) was officially launched by the then Minister for Housing and the then Treasurer, on 24 July 2008. This was several months in advance of the legislation and regulations supporting the operation of the scheme being put in place.

This audit has focused on the application and assessment stages of NRAS since it commenced. The report contains no recommendations as further NRAS rounds are not expected to be called and changes to the conditions of reserved allocations can now only be made in very limited circumstances, mainly in the event of a natural disaster. Nevertheless, NRAS will continue to operate for a further 10 years as dwellings are entered into the scheme and annual incentive payments fall due. Over this time it is important that the responsible department maintains an appropriate level of senior management oversight of the scheme.

The implementation of NRAS has highlighted the need for effective planning and sound administration, if Government programs are to be successfully implemented and are to achieve their objectives and expected outcomes. In considering the findings of the report several key learnings emerged, these include the importance of:

- effectively planning for the implementation of programs, including allowing sufficient time for the administrative design features and any supporting legislative and regulatory frameworks to be settled prior to commencing formal implementation;

- integrating risk management processes into the overall design, governance, strategy, planning and administration, to effectively manage risks to the achievement of the objectives and outcomes of programs;

- identifying the required mix of essential skills, experience and capability to assist with the efficient and effective design, implementation and administration of programs, in accordance with broader government policy and any underlying legislative and regulatory frameworks;

- conducting application and assessment processes in a manner that accords with policy, legislative and regulatory requirements, including establishing robust probity and sound decision making processes, and complying with procedural fairness and other administrative law requirements;

- evaluating programs with a focus on understanding their impact, whether the policy objectives and expected outcomes are being achieved, and whether the underlying policy approach is an effective intervention;

- departments drawing to the attention of the Government, as early as possible, key risks and shortcomings in policy design and the likelihood that related programs may not fully achieve their intended objectives or outcomes; and

- creating and maintaining a minimum standard of documentation in relation to administrative processes and decisions in order to support accountability and transparency.

Summary

Introduction

1. The National Rental Affordability Scheme (NRAS or the scheme) commenced in 2008. The scheme was expected to contribute to improvements in the affordability of rental accommodation for low and moderate income households. The objectives of the scheme were to:

- stimulate the supply of up to 50 000 new affordable rental dwellings (by the end of 2011–12);

- reduce rental costs for low and moderate income households; and

- encourage large-scale investment in, and innovative delivery of, affordable housing.1

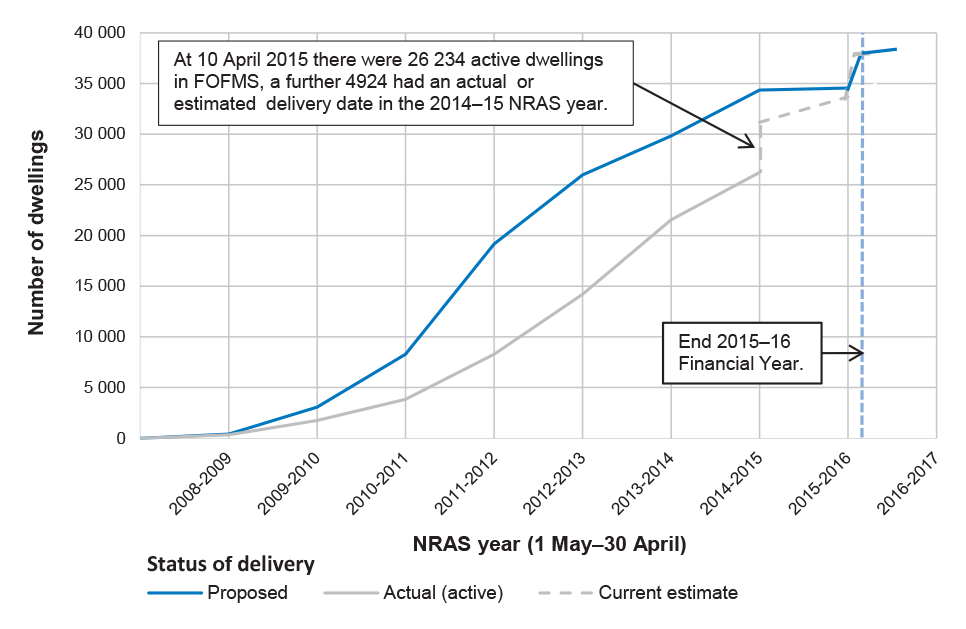

2. The target of 50 000 dwellings was revised in the 2011–12 Budget with the then Government extending the delivery timeframe, providing funding for 35 000 allocations between 2008–09 and 2014–15, with funding for the remaining 15 000 allocations to be made available in later periods. The overall target was revised as part of the 2014–15 Budget with the Government subsequently announcing that no further allocations would be offered as the scheme had not been successful in meeting its objectives, effectively capping the scheme at 38 000 dwellings.

3. A total of six application rounds were called between 2008 and 2013. Applicants2 were offered allocations or reserved allocations3 during five of the six rounds, with no offers made in relation to the last round. By mid-2015 around 26 000 dwellings had been delivered into the scheme. The remaining dwellings are expected to be completed by 30 June 2016. Allocations or reserved allocations are held by 145 approved participants4, although some NRAS dwellings have been on-sold to third-party small investors.5

4. Through the scheme, approved participants are able to access an annual indexed incentive of $6000 per dwelling for up to ten years.6 The incentive has been made available in the form of a refundable tax offset if the approved participant is an entity to which Division 380 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 applies7 and/or a payment where the approved participant is an endorsed charitable institution.8 To be eligible to receive the annual incentive, the dwelling must have been rented to an eligible tenant9 and have been rented at a rate which is at least 20 per cent below market value at all times during the NRAS year (1 May to 30 April). Approved participants may also receive either a financial benefit or in-kind support from the relevant state or territory government.

Scheme administrative arrangements

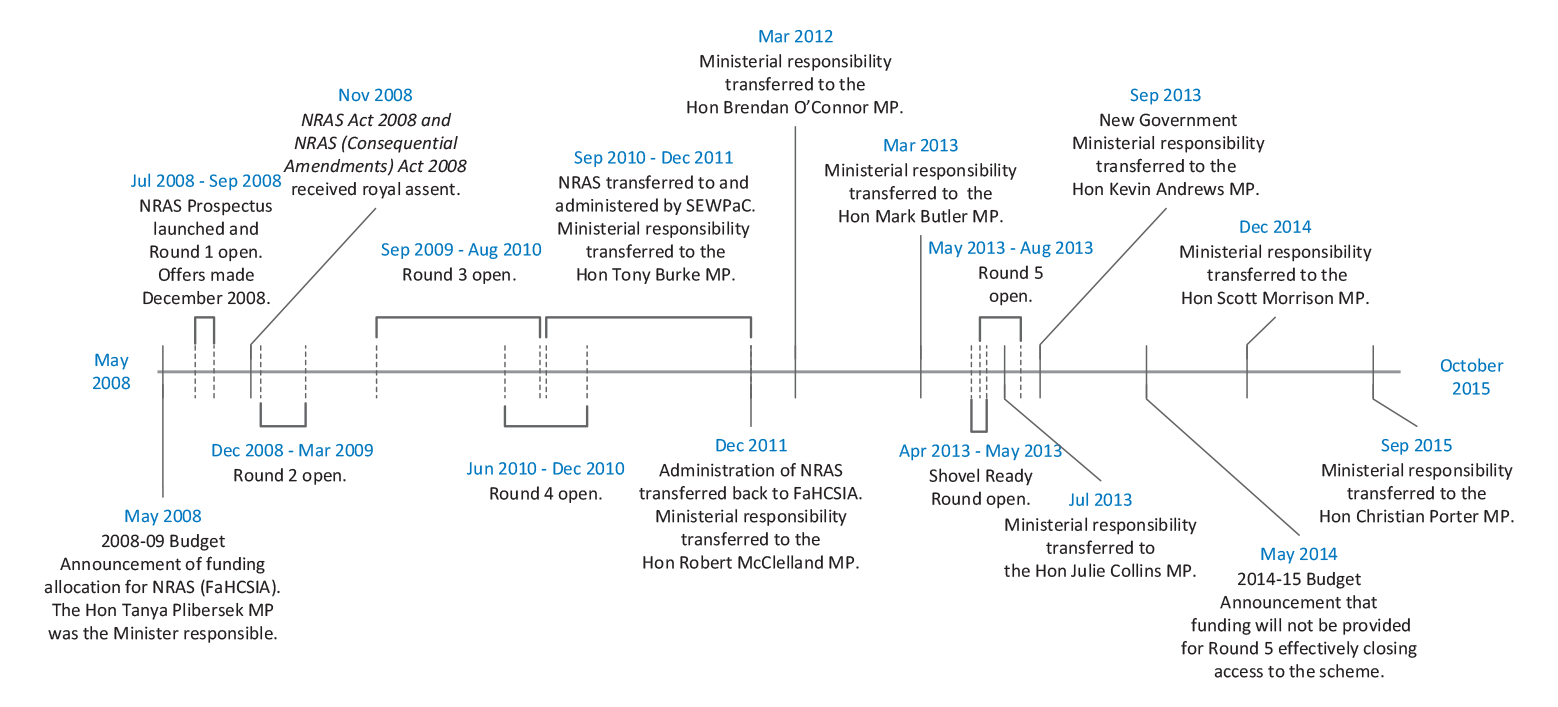

5. The National Rental Affordability Scheme Act 2008 (the Act) and the National Rental Affordability Scheme Regulations 2008 (the Regulations) established the framework for the administration of the scheme. Since commencing, the scheme has been administered by three departments and has been overseen by nine Ministers. The then Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) was initially responsible for the design and implementation of the scheme between 2008 and September 2010. At that time, responsibility for administering the scheme transferred to the then newly created Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPaC). In December 2011, the administration of the scheme was transferred back to FaHCSIA and since late September 2013, the scheme has been administered by the Department of Social Services (DSS).10 Figure 1.1 on the following page outlines significant events and administrative changes over the life of the scheme, including details of the responsible departments and ministers. Current departmental estimates of the whole of life cost of the scheme are in the order of $3.5 billion, with this funding to be allocated up to 2026. Departmental budget forecasts in relation to the scheme indicate that by the end of 2014–15, nearly $560 million will have been spent, with incentive payments and tax offsets expected to peak in 2020–21 at around $345 million.

Figure 1.1: NRAS timeline of administrative and ministerial responsibilities

Source: ANAO analysis of DSS records and publicly available information.

Audit objective and criteria

Audit objective

6. The objective of the audit was to examine the effectiveness of DSS’ administration of NRAS, with a focus on the assessment of applications, and management of reserved allocations. This is the first of two audits on the administration of NRAS. The second audit will examine the department’s processing of approved participants’ statements of compliance (claims for incentives) and the issuing of refundable tax offsets or payments, as applicable.

Criteria

7. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the Australian National Audit Office’s (ANAO’s) high level criteria included assessing whether:

- applications made under the scheme were assessed in accordance with the requirements of the Regulations and other government policy requirements; and

- incentives were allocated or reserved, and managed, in accordance with the conditions set out in the Regulations.

Overall conclusion

8. From the commencement of NRAS in 2008 the delivery of eligible dwellings has been slower than anticipated. The initial target of 50 000 dwellings was reduced to 38 000 dwellings, but the funding for any reserved allocations or allocations withdrawn or revoked is to be returned to budget.11 By mid-April 2015 the number of dwellings expected to be delivered into the scheme had reduced to 37 679, with less than 27 000 dwellings entered into the scheme. If the revised target of around 38 000 dwellings is to be achieved by 30 June 2016, a significant acceleration in the construction of eligible dwellings is required.

9. The policy objectives of NRAS were threefold and while the department monitors the delivery of dwellings into the scheme and whether eligible dwellings are rented at 20 per cent or more below the market rate, no processes have been put in place to monitor or evaluate whether the scheme has encouraged large scale investment in affordable housing, the innovative design of affordable housing and/or whether NRAS has had any flow on effect in the housing market.

10. Administration of the application and assessment process and management of reserved allocations for NRAS has not been effective. During the early years there was a lack of understanding of the Regulations and the operating environment, which led to the scheme being administered in a manner which did not fully accord with the requirements of the Regulations. The processes for assessing applications, managing reserved allocations and the overall administration of the scheme could have been better planned and implemented. The department has more recently focused on improving the administration of the scheme and sought amendments to the Regulations to address key risks, including the slower than expected delivery of dwellings into the scheme.

Supporting findings

11. To gain entry into NRAS a series of application rounds were called between 2008 and 2013. Applications received in relation to the scheme were assessed by the administering department and relevant state and territory government agencies. The requirements of the Regulations were not clearly understood and the approach to assessing applications did not always fully comply with the Regulations, which may have resulted in some otherwise meritorious applications not being supported. Administrative law and procedural fairness requirements were also not consistently met across all application rounds during the assessment process.

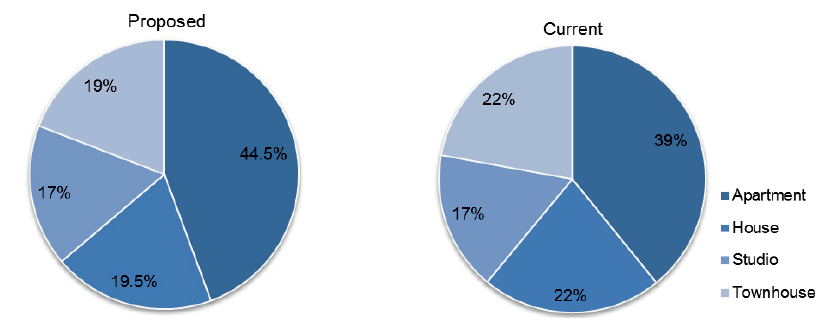

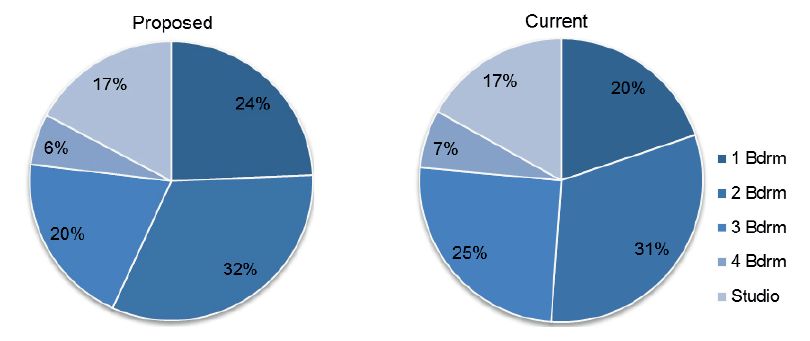

12. Following the assessment of applications, successful applicants were offered allocations where a dwelling was available for rent, or reserved allocations where the dwellings were yet to be constructed. A reserved allocation was a conditional offer whereby the applicant agreed to deliver a dwelling, of a specific style and size, and in a specific location by an agreed future date. By mid-April 2015 over 145 000 changes have been made to the size, style, location and agreed available for rent date of dwellings, despite changes to the conditions of reserved allocations by approved participants not being identified as a risk during the design of the scheme.

13. The department was slow in developing policies and procedures to effectively manage the variation or change process and the ongoing management of reserved allocations could have been improved to support the delivery of dwellings into the scheme as originally agreed between approved participants and the administering departments. Amendments to the Regulations in late 2014 have restricted extensions to the available for rent date for dwellings and changes in the location and/or style of dwellings, encouraging approved participants to deliver dwellings as previously agreed.

14. The application and assessment process and the management of reserved allocations were also affected by the quality and completeness of departmental records. Records retained in relation to the scheme were insufficient to support an assessment of whether key events, such as all of the calls for rounds, were authorised by the delegate. The department also did not have a complete or reliable record of dwellings as originally or subsequently approved to form an accurate baseline against which the scheme can be administered.

15. Over the life of the scheme, emerging risks including the slower than expected delivery of dwellings into the scheme were drawn to the attention of successive governments, largely from late 2012. The advice to Government prior to 2014 did not adequately canvas options for improving the delivery of dwellings into the scheme, or advise the Government in relation to the shortcomings in the overall policy design and approach, or of the likelihood that the objectives and intended outcomes of the scheme would not be fully achieved. To address these risks the department could have taken administrative action and withdrawn reserved allocations where it was apparent the associated conditions were unable to be met. As an alternative, the department relied on amending the Regulations. In part, the 2014 amendments to the Regulations were designed to accelerate the delivery of dwellings into the scheme.

Summary of entity response

The proposed audit report was provided to DSS. DSS provided formal comments on the proposed report and these are summarised below, with the full response included at Appendix 1:

The Department acknowledges the findings in the audit report. The Department has already implemented, or is in the process of implementing, major reforms to improve its capability in policy development, programme management, workforce planning and information management. These reforms address the key learnings identified in the report and will support the design and delivery of future programmes.

The Department also notes the recognition in the report of improvements made to the NRAS. The report also highlights that issues with the Scheme were exacerbated by several moves between departments as a result of Machinery of Government changes, along with the tight timeline resulting in significant time constraints for implementation.

1. Introduction

Background

1.1 The National Rental Affordability Scheme (NRAS or the scheme) is a supply-side initiative aimed at encouraging investment in newly constructed rental dwellings. The scheme was established in 2008 with the overall objectives of:

- stimulating the supply of up to 50 000 new affordable rental dwellings (by the end of 2011–12);

- reducing rental costs for low and moderate income households; and

- encouraging large scale investment, in and innovate design of, affordable housing.12

1.2 The Australian Government offered applicants13 access to an annual incentive of $6000 per dwelling for up to ten years. The annual incentive is indexed to the housing group of the consumer price index from the date when the dwelling first becomes available for rent. The incentive has been made available in the form of a refundable tax offset if the approved participant14 is an entity to which Division 380 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 applies15 and/or a payment where the approved participant is an endorsed charitable institution.16

1.3 For approved participants to be eligible to receive the annual incentive, the dwelling must have been rented to an eligible tenant17 and have been rented at a rate which is at least 20 per cent below market value at all times during the NRAS year.18 The approved participant is also required to comply with any other conditions of allocation or special conditions imposed. Failure to comply with these requirements could result in the approved participant being ineligible to receive the incentive for the specified period (the relevant NRAS year) or only being eligible to receive a proportionally reduced amount.

1.4 The state or territory governments also offered approved participants a co-contribution in the form of a payment or other in-kind support and agreed to match the Australian Government’s rate of indexation where they provide a contribution to approved applicants on an annual basis. To be eligible to receive the relevant state or territory government’s contribution, approved participants may also be required to comply with other conditions imposed by the state and territory government.

Audit objective, criteria, scope and methodology

Audit objective

1.5 The objective of the audit was to examine the effectiveness of Department of Social Services’ (DSS’) administration of the NRAS, with a focus on the assessment of applications, and management of reserved allocations.19

Criteria

1.6 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO’s high level criteria included assessing whether:

- applications made under the scheme were assessed in accordance with the requirements of the Regulations and other government policy requirements; and

- incentives were allocated or reserved, and managed, in accordance with the conditions set out in the Regulations.

Scope

1.7 This audit is the first of two audits examining the administration of NRAS. The first audit has examined the call for applications in relation to each of the six rounds and the department’s assessment of applications received. The management of the stock of reserved allocations has also been examined, along with consideration of the withdrawal of allocations where an approved participant has not complied with the requirements of the scheme. The second audit will examine the department’s processing of approved participants’ statements of compliance (claims for incentives) and the issuing of refundable tax offsets or payments, as applicable.

Audit methodology

1.8 The audit included an examination of information held by DSS relating to the development, implementation and ongoing administration of the scheme. This involved examining a sample of applications from each application round and applicant and dwellings’ data held in FOFMS20, the information technology system used to assist with the administration of the scheme. Interviews were also held with a number of key stakeholders about changes in the housing market, the impact of the scheme on housing and rental affordability and DSS’ administration of the scheme. Key stakeholders were also provided with the opportunity to contribute to the audit through the ANAO’s Citizen Input Facility.21

1.9 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO auditing standards at a cost of $725 584.

2. NRAS administrative arrangements and overall progress

Areas examined

The ANAO considered the development and implementation of the scheme, the supporting legislative and regulatory framework and administrative arrangements.

Supporting findings

- The Act and Regulations forming the basis for the administration of the scheme came into effect from late November 2008, but were retrospective from 1 July 2008.

- The first call for applications was made in July 2008, well in advance of the supporting legislation and Regulations being in place. Until such time as the Act and Regulations were in place, there was no framework to formally support the implementation or administration of the scheme, including the first call for applications.

- The department’s estimate of the whole of life cost of NRAS is around $3.5 billion. This funding is expected to be allocated over the period 2008–09 to 2025–26. By 2014–15, around $560 million had been spent on NRAS incentives.

- By 10 April 2015, 26 234 eligible dwellings had been delivered into the scheme.

- Over the life of the scheme to date, new residential dwelling approvals in Australia have been around 100 000 each year.

- Queensland received the largest number of allocations, 10 427 or 27 per cent, while the Northern Territory is the least represented jurisdiction with applicants receiving 1246 or three per cent of allocations.

- The Government expected that institutional investors would be key participants in the scheme, however, not for profit organisations hold the largest number of allocations or reserved allocations, followed by for profit organisations, then universities and other student accommodation providers.

Key learnings

- Effectively planning for the implementation of programs, including allowing sufficient time for the administrative design features and any supporting legislative and regulatory frameworks to be settled prior to commencing formal implementation.

- Integrating risk management processes into the overall design, governance, strategy, planning and administration, to effectively manage risks to the achievement of the objectives and outcomes of programs.

Scheme development

2.1 The scheme was initiated following a Senate Committee inquiry into housing affordability in Australia which considered in 2008 that there was an inadequate supply of rental housing in Australia with record lows in rental vacancies.

2.2 The Australian Government released a technical discussion paper about establishing a rental affordability scheme in May 2008, seeking submissions and comments to assist with settling the final design features of the scheme. The technical discussion paper outlined the key elements of the scheme and the role of the Australian, state and territory governments. This included that:

- the scheme would offer a national rental incentive to providers of new dwellings on the condition that they are rented to low and moderate income households at 20 per cent below-market rates;

- the incentive would comprise of an Australian Government contribution in the form of a tax offset or grant, and a state or territory government contribution in the form of financial and/or other support;

- the incentive would be provided annually for ten years on the condition that the dwelling is rented to eligible low and moderate income households for at least 20 per cent below market rates for each of the ten years;

- the usual eligibility rules for Commonwealth Rent Assistance would apply;22

- the dwellings would be managed in accordance with relevant state or territory government regulatory requirements; and

- participants would be subject to specific reporting requirements in relation to tenancy selection and management, as well as to regular reporting for compliance purposes.

2.3 The technical discussion paper stated that the scheme was designed to pool resources from a range of participants including financial institutions, non-profit organisations and local government. Further, it was expected that by requiring dwellings to be rented below market rent that the scheme would substantially improve housing affordability for tenants. The department received 127 submissions in response to the technical discussion paper and this feedback guided the design of the scheme. Key matters guiding the final scheme design, included:

- broadening eligibility requirements for tenants;

- developing a framework for market rent valuations and the indexation of rent charged;

- introducing a minimum size for housing portfolios (a minimum of twenty dwellings during the establishment phase of the scheme); and

- basing the scheme in legislation with an act to cover high level provisions, with the other aspects of the scheme to be covered by subordinate instruments.

2.4 Matters raised during the consultations not reflected in the design of the scheme included a graduated penalty regime, and reducing the number of dwellings for which incentives would be available, while also increasing the value of the incentive for each dwelling. Following the consultation process, the then Treasurer and the then Minister for Housing, on 24 July 2008, in a joint press release launched the National Rental Affordability Scheme Prospectus. The Prospectus provided information to institutions and organisations considering applying for NRAS incentives and announced the opening of Round One. This was in advance of the legislative framework to support the implementation of the scheme being established. There was no record of the department providing advice to the Government about delaying the first call for applications until such time and the Act and supporting Regulations were in place.

NRAS legislative and regulatory framework

2.5 The National Rental Affordability Scheme Act 2008 (the Act) and the National Rental Affordability Scheme Regulations 2008 (the Regulations) form the basis for the administration of the scheme, with the Act receiving royal assent on 25 November 2008. The Regulations were subsequently made on 28 November 2008 with both having retrospective effect from 1 July 2008. Amendments were made to the Regulations on seven occasions between 2009 and 2014 with the most significant changes designed to provide the delegate with greater flexibility in administering the scheme and to accelerate the delivery of eligible dwellings. Other changes were made to better align the Regulations with existing administrative practice and the overall policy intent of the scheme. As a regulatory program, the scheme is required to be administered in a manner which accords with the requirements of the Act and Regulations. Key requirements supporting the administration of the scheme are presented in Appendix 2.

2.6 The first round of applications under the scheme opened on 24 July 2008, several months prior to the Act and Regulations being put in place. Applicants were informed that any changes to the proposed legislation would be communicated and offers were not made until the Regulations were created. FaHCSIA advised the then Minister for Housing against calling for a second round of applications prior to the assent of the legislation on the basis that until the Act received assent and the Regulations were created, there was:

- no scheme against which any action could be taken;

- no criteria to use for the purposes of assessing applications; and

- no delegate for the scheme, which meant that decisions could not be made about application rounds or closing dates.

NRAS targets and funding

2.7 When the scheme was launched, the Government expected that it would ‘assist institutional investors, developers and not-for-profit groups to deliver 50 000 rental dwellings over the next four financial years by creating a new residential property asset class for property investors’.23 The scheme was expected to stimulate the construction of:

- 3500 new rental dwellings in 2008–09;

- 7500 new rental dwellings in 2009–10;

- 14 000 new rental dwellings in 2010–11; and

- 25 000 new rental dwellings in 2011–12.24

2.8 The then Prime Minister and then Minister for Housing had also previously announced in March 2008 that if 50 000 incentives were achieved in the first four years and if market demand from renters and investors remained strong, that an additional 50 000 incentives would be available from 2012 onwards.25

2.9 Funding for the scheme was first announced as part of the 2008–09 Budget. Subsequently the Government made a number of changes to the funding and targets for the scheme. Funding for NRAS was redirected in the 2011–12 Budget to assist with the rebuilding of flood-affected regions across Australia.26 The Government also extended the implementation of the scheme, providing funding for 35 000 allocations between 2008–09 and 2014–15, with funding for the remaining 15 000 allocations to become available in later periods. Following the slower than anticipated delivery of new rental dwellings into the scheme, the Government announced as part of the 2014–15 Budget that no further allocations would be offered as the scheme had not been successful in achieving its objectives.27 At the same time, the overall target for the scheme was revised down to 38 000 dwellings. Current departmental estimates of the whole of life cost of the scheme are in the order of $3.5 billion, with this funding to be allocated up to 2026. Departmental budget forecasts in relation to the scheme indicate that by the end of 2014–15, nearly $560 million will have been spent, with incentive payments and tax offsets expected to peak in 2020–21 at around $345 million.

Administering entities

2.10 Since NRAS commenced in 2008, the scheme has been administered by three departments and has been overseen by nine Ministers. FaHCSIA was initially responsible for the design and implementation of the scheme between 2008 and September 2010. Responsibility for administering the scheme was then transferred to the newly created Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPaC—now the Department of the Environment). In December 2011, the administration of the scheme was transferred back to FaHCSIA and since late September 2013, the scheme has been administered by DSS.28 The Secretary of the department is the delegate for the purpose of administering the scheme, but these powers can be delegated to other officers. Figure 2.1 outlines key administrative changes over the life of the scheme, including details of the responsible departments and Ministers.

Figure 2.1: NRAS timeline of administrative and ministerial responsibilities

Source: ANAO analysis of DSS records and publicly available information.

NRAS funding rounds

2.11 Allocations or reserved allocations29 have been offered to applicants following the assessment of applications received through six rounds undertaken between July 2008 and August 2013. To support the achievement of the initial outcome of 50 000 new rental dwellings, delivery of eligible dwellings was divided into two phases, the:

- establishment phase—Rounds One and Two under which a total of 11 000 allocations or reserved allocations were expected to be offered during 2008–09 and 2009–10; and

- expansion phase—Rounds Three and Four consisting of 39 000 allocations or reserved allocations which were expected to be offered in 2010–11 and 2011–12.

2.12 Initial uptake of the scheme was much lower than anticipated and as noted in paragraph 2.9, the Government amended its overall target to 38 000 dwellings of which 35 000 were to be delivered by 2014–15. DSS’ records indicate that by mid-April 2015, 37 679 allocations had been made or reserved, highlighting that the revised target of 38 000 dwellings will no longer be achieved. Furthermore, it is likely that less than 37 679 dwellings will be delivered as some reserved allocations may be withdrawn, as the associated dwellings cannot be delivered, and/or allocations may be revoked, as approved participants or third-party investors30 choose to exit the scheme. A summary of the outcomes of each round is presented in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1: National Rental Affordability Scheme rounds

|

Round |

Date opened |

Date closed |

Incentives allocated or reserved1 |

|

1 |

24 July 2008 |

4 September 2008 |

3 018 |

|

2 |

17 December 2008 |

27 March 2009 |

4 873 |

|

3 |

1 September 2009 |

31 August 2010 |

9 385 |

|

4 |

14 June 2010 |

14 December 2010 |

18 039 |

|

Shovel Ready |

18 April 2013 |

22 May 2013 |

2 364 |

|

52 |

7 May 2013 |

6 August 2013 |

N/A |

|

Total |

37 679 |

||

Note 1: Figures do not include allocations which were ceased, revoked, withdrawn or substituted.

Note 2: Round Five did not proceed. The Australian Government’s decision not to proceed was announced as part of the 2014–15 Budget.

Source: ANAO analysis of DSS data.

2.13 In May 2014, prior to the finalisation of Round Five, the Government announced as part of the 2014–15 Budget, that the final round of NRAS had been suspended and that no allocations or reserved allocations would be offered to applicants as part of that round.31 In closing the scheme, the Government also announced that for incentives already allocated, payments would continue to be made for up to ten years from the date of activation providing eligibility requirements were met and homes were built in agreed locations and within the agreed timeframes.32 The funding for unallocated incentives or reserved allocations not used within the agreed timeframes were to be returned to the budget.

Overall progress

2.14 By 10 April 2015, 26 234 eligible dwellings were delivered into the scheme, with a further 11 445 reserved.33 While this result is just under the Government’s revised target of 38 000, it is more than 12 000 less than originally envisaged when the scheme was launched.34 Over the life of the scheme to date, new residential dwelling approvals in Australia have been around 100 000 each year. The distribution of NRAS dwellings across jurisdictions is discussed in paragraphs 2.16 and 2.17.

2.15 The department monitors the delivery of dwellings into the scheme and whether eligible dwellings have been rented at 20 per cent or more below the market rate, as required by the Regulations. To better understand the impact of the scheme and whether the scheme’s objectives were being achieved, there would be benefit in the department establishing processes to monitor and evaluate the extent to which the scheme has encouraged large scale investment in and/or the innovative design of affordable housing.

Distribution of allocations by state or territory

2.16 NRAS is a national scheme supported by a co-contribution from the state and territory governments. The level of financial support provided by each state and territory government was discretionary and varied across the rounds. The level of support has influenced the distribution of allocations and reserved allocations by state or territory, which is not closely aligned with the proportional distribution of low and moderate income households as represented in Table 2.2.35 A more proportional distribution could have been achieved by the Government offering applicants Commonwealth only incentives36 where the level of state or territory government support was lower than the proportional representation of low to moderate income households.

Table 2.2: Distribution of allocations and reserved allocations by state or territory

|

State |

Allocations |

Reserved allocations |

Total allocations1 |

Percentage of allocations |

Percentage of low to moderate income households2 |

|

ACT |

1 959 |

458 |

2 417 |

6.41 |

1.96 |

|

NSW |

3 104 |

3 726 |

6 830 |

18.13 |

30.83 |

|

NT |

372 |

874 |

1 246 |

3.31 |

1.33 |

|

QLD |

9 223 |

1 204 |

10 427 |

27.67 |

19.73 |

|

SA |

2 903 |

754 |

3 657 |

9.71 |

7.64 |

|

TAS |

825 |

811 |

1 636 |

4.34 |

2.43 |

|

VIC |

5 173 |

981 |

6 154 |

16.33 |

25.42 |

|

WA |

2 675 |

2 637 |

5 312 |

14.10 |

10.67 |

|

Total |

26 234 |

11 445 |

37 679 |

100.00 |

100.00 |

Note 1: Figures do not include allocations which were ceased, revoked, withdrawn or substituted.

Note 2: Based on Australian Bureau of Statistics, ‘Household and Income Distribution, Australia 2011–12’, cat. no 6523.0.

Source: ANAO analysis of DSS and Australian Bureau of Statistics data.

2.17 An examination of the distribution of allocations and reserved allocations by state or territory highlighted that Queensland received the largest number of allocations, 10 427 or 27 per cent compared to a proportional distribution of low to moderate income households of 19 per cent.37 New South Wales and Victoria received proportionately fewer allocations at 18 per cent and 16 per cent, despite these jurisdictions having a higher proportional distribution of low to moderate income households at 31 per cent and 25 per cent respectively. The final location on NRAS dwellings is presented in Figure 2.2, which highlights that the majority of dwellings are located in major cities and inner regional areas.

Figure 2.2: Location of NRAS dwellings (eligible and proposed)

Source: ANAO analysis of DSS data

Profile of approved participants

2.18 Each round of NRAS has attracted a mix of applicants. Both the not-for-profit and for-profit sectors have been represented in all rounds, with universities and student accommodation providers also applying for and securing allocations in the second, third, fourth and shovel ready rounds. While the scheme was expected to encourage institutional investors, developers and not-for-profit groups to deliver affordable rental dwellings for low to moderate income households, institutional investors have not participated to the extent originally envisaged. As at mid-April 2015, allocations or reserved allocations are held by 145 approved participants, although many NRAS dwellings have been on-sold to third-party small investors. Overall, not-for-profit organisations hold the largest number of allocation or reserved allocations, followed by for-profit organisations, then universities and student accommodation providers.

Universities and student accommodation providers

2.19 One policy objective of NRAS was to provide affordable rental accommodation for people on low to moderate incomes.38 In this respect, the scheme has been criticised in the media for supporting the provision of allocations for student accommodation, particularly as NRAS dwellings have been rented to non-resident students. The Regulations do not prohibit student accommodation providers from holding allocations or reserved allocations and are silent about the need for tenants of NRAS dwellings to be Australian residents. The delegate has discretion in making offers of allocations and can impose special conditions. In making offers of allocations or reserved allocations to universities, the delegates generally imposed the following conditions:

- that tenancies are also made available to tenants other than students;

- where tenants are students, priority is given to those travelling from elsewhere in Australia; and

- that initial leases are to be for a term of no less than 52 weeks. 39

2.20 Tenancy demographic data captured by the department indicates that of the 3652 active allocations held by universities, 1812 or 50 per cent were occupied by non-resident students during 2013–14. While approving NRAS eligible dwellings for student accommodation may relieve pressure on affordable rental accommodation in areas in and around universities, it can also reduce the total number of incentives available for other accommodation types.

3. Application and assessment process

Areas examined

The ANAO examined the adequacy of guidance provided by the department to applicants, and whether applications made under the scheme were assessed in accordance with the requirements of the Regulations and other government policy requirements. The role of probity and legal advisers and the delegate as decision maker were also examined.

Supporting findings

- As part of each call for applications guidance was issued to applicants about how to apply for allocations or reserved allocation. This guidance was not always clear and more complete information may have assisted applicants with submitting compliant applicants and all of the required information.

- A total of six rounds were called between 2008 and 2013, but there is a lack of certainty about the nature of the authority for the conduct of each round. The Regulations require a delegate to authorise each round, although DSS only had a record of the delegate authorising two of the rounds.

- The implementation of the assessment process and the prioritisation of applications by the administering department unintentionally disadvantaged some applicants with these applicants not receiving offers of allocations or reserved allocations.

- An internal review of the assessment processes in relation to the early rounds concluded that the transparency of the processes could have been improved with some of the processes considered to not comply with procedural fairness requirements or sound administrative decision making principles.

- Aspects of the application and assessment process have not been administered in a manner which fully accorded with the requirements of the Regulations and/or guidelines issued in support of the call for applications. This included:

- not fully assessing applications against the priority areas of interest forming part of the sets of assessment criteria;

- separately assessing projects within an application rather than the application as a whole;

- the state and territory governments’ completing a full assessment of applications during Round One; and

- prioritising applications by state or territory despite NRAS being a national program.

- The application and assessment processes improved over time with a higher level of engagement with the department’s legal services.

Key learnings

- Identifying the required mix of essential skills, experience and capability to assist with the efficient and effective design, implementation and administration of policy measures, in accordance with broader government policy and underlying legislative and regulatory frameworks.

- Conducting application and assessment processes in a manner that accords with policy, legislative and regulatory requirements, including establishing robust probity and sound decision making processes, and complying with procedural fairness and other administrative law requirements.

Guidance to applicants and key planning documents

3.1 As the initial administering department, FaHCSIA prepared guidance documents to support the first call for applications. This included the initial NRAS Guidelines and Application Guidelines which provided information to applicants about how the scheme would operate, how to apply for allocations, and how applications would be assessed. This suite of documents was subsequently updated with each call for applications. From Round Two onwards the Act and Regulations also provided further guidance for applicants. Despite this, a feature of the scheme during the conduct of several rounds was the receipt of large numbers of non-compliant applications. The quality of the guidance as well as the lack of experience of some applicants in dealing with government application processes of this nature may have contributed to this outcome.

3.2 The department’s record keeping in relation to guidance provided to applicants and internal planning and policy documents prepared to support the application and assessment processes could have been improved. The department retained copies of most of the guidance documents from each round with the exception of the Assessment Plan for Round Five. Other governance documents including the probity plans and deeds of confidentiality/conflict of interest declarations could only be provided by the department for the Shovel Ready Round and Round Five. Table 3.1 presents information about the retention of these important documents by the department.

Table 3.1: Guidance material and planning documents retained

|

Document |

Round One |

Round Two |

Round Three |

Round Four |

Shovel Ready/ Round Five |

|

NRAS Guidelines |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Application Guidelines |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Assessment Plan |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

|

Probity Plan |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

|

Deeds of confidentiality/ conflict of interest declarations |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

Source: ANAO analysis.

NRAS Guidelines

3.3 The NRAS Guidelines are program level guidelines and provide a general description of the scheme, setting out the objectives and outlining the regulatory framework under which the scheme operates. The Regulations allow for the delegate to issue guidelines about how an applicant may apply for allocations in relation to a call for applications and where guidelines are issued the Regulations state that applicants are required to comply with these. The Guidelines imposed additional requirements on applicants, particularly in relation to the form in which an application was to be submitted.

Application Guidelines

3.4 The Application Guidelines were developed to provide advice and guidance to applicants about how to apply for incentives and how applications would be assessed. Similar to the NRAS Guidelines, applicants were required to comply with any guidelines issued as part of a call for applications. Therefore, the Application Guidelines were central to enabling an efficient and compliant application process.

3.5 While the guidelines provided applicants with adequate information about the application and assessment process, additional and/or more reliable information could have been provided to applicants, particularly in relation to the early rounds. A key omission from the early Application Guidelines was information about how financial and organisational viability was to be assessed. Financial viability was a key part of the assessment process and more complete information about this process may have assisted applicants with providing all of the required information. The guidance to applicants improved as the scheme progressed, with the Application Guidelines for Round Four onwards being more comprehensive.

Assessment Plans

3.6 The Assessment Plans for each round were the main documents used to guide the assessment of applications. Typically, these plans set out how each criterion was to be assessed and key decision points in the assessment process. The Assessment Plans also outlined the roles and responsibilities of the assessment teams, external consultants, quality assurers, the state and territory governments and the delegate.

3.7 The Assessment Toolkits, an attachment to the Assessment Plans, were primarily an internal resource developed to standardise the assessment process. The toolkits provided additional guidance about assessing each criterion and detailed the respective benchmark scores. In December 2009, the department’s legal services suggested making the Assessment Toolkits available to applicants following a request for an internal review and the commencement of a judicial review by an unsuccessful applicant from Round Two. The toolkits were made available to applicants for the Shovel Ready Round and Round Five which were called in April and May 2013 respectively.

Deeds of confidentiality and conflict of interest declarations

3.8 Officers involved in the design of application processes and the assessment of applications should be aware of confidentiality requirements and situations that could give rise to a conflict of interest. While the Assessment Plans from Round Two onwards contained deeds of confidentiality templates and conflict of interest declarations, the department was unable to provide signed copies for any rounds, with the exception of assessment staff from the Shovel Ready Round and Round Five. The department could also not locate any signed deeds of confidentiality or conflicts of interest declarations for any of the delegates.

3.9 Australian Public Servants are bound by confidentiality obligations through the course of their employment.40 Members of the assessment teams and delegates formally acknowledging their confidentiality obligations would have reinforced the sensitivity of the application and assessment process. This was particularly relevant as the assessment process also involved third parties, including representatives from the state and territory governments. One state government was a shareholder of an entity applying for reserved allocations in Round Four, creating an actual, potential or perceived conflict of interest for the state assessment team. A 2009 internal audit of NRAS also identified breaches of privacy and confidentiality relating to the assessment of Round Two applications, highlighting the need for these processes to be reinforced to the officers involved.

Calls for applications

3.10 NRAS was implemented in two phases—establishment and expansion. During the establishment phase, the application and assessment processes focused on selecting proposals where the applicants were expected to be able to deliver dwellings by 30 June 2010. Moving into the expansion phase, Round Three called for applications that could deliver larger scale developments or that were tied to other Australian Government social housing and economic stimulus initiatives. Round Four, the Shovel Ready Round and Round Five focussed on expanding the scheme. Presented in Table 3.2 is a summary of the main focus areas of each round.

Table 3.2: Assessment criteria specified as part of each call for applications—Schedule 1 of the NRAS Regulations

|

NRAS round |

Main focus area |

|

1 |

Dwellings that would be available for rent between 1 July 2008 and 30 June 2010. |

|

2 |

Early round: projects that could be completed and available by 30 June 2009. Main round: projects that were due to be completed after 1 July 2009. |

|

3 |

Projects on state/territory owned land which had been released for mixed residential development by state/territory governments; or Projects that involved 1000 or more dwellings; or Projects that linked to the Social Housing Initiative which was a component of the Nation Building and Economic Stimulus Plan. |

|

4 |

Proposals of 20 or more dwellings, although applications for 100 or more dwellings were preferred. |

|

Shovel Ready |

Dwellings that could become available for rent by June 2014. |

|

5 |

Dwellings that could become available for rent between 1 July 2015 and 30 June 2016. |

Source: NRAS Application Guidelines.

3.11 In accordance with the Regulations, the Secretary (or their delegate) is the only person authorised to make a call for applications and any call for applications is required to specify the set of criteria to be used in assessing applications. Calls for applications were made through the release of the Application Guidelines for each round, but the records of the delegates’ decisions in relation to the calls for applications for Rounds One to Four have not been maintained. In substance, an administrative decision to call these rounds may have been made, but a record of the delegate’s authorisation exists only for the Shovel Ready Round and Round Five. In the absence of these records, it not clear whether there is an express authority for the conduct of several of the rounds.

Assessing applications

3.12 The assessment of applications involved four stages:

- compliance checking;

- assessment against the criteria;

- assessment of financial and organisational viability; and

- assessment by the relevant state and/or territory governments.

Compliance checking

3.13 The department conducted a completeness and correctness check to determine whether applications met the mandatory requirements of the scheme, and that all required information was provided. Where a non-compliant application was received, the delegate was able to invite the applicant to vary the application or request additional information. In relation to Round Two, of the 140 applications received only 25 were deemed to be fully compliant at the time of submission. The department requested the remaining 115 applicants to provide further information. During the subsequent rounds, the assessment toolkit and financial viability methodology were made available to applicants giving the applicants greater detail about the assessment process. Despite this, the number of non-compliant applications received remained high. For example, in relation to the 29 applications examined from the Shovel Ready Round, 76 per cent of applicants were invited to provide further information in order to proceed to assessment.41

Assessing applications against the assessment criteria

3.14 The delegate was required to assess applications in accordance with the assessment criteria specified in the call for applications. The assessment of applications involved evaluating and scoring compliant applications against the specified set of assessment criteria, including the main focus areas as set out in Table 3.2. This provided a consistent basis for assessing applications and assisted in differentiating between applications of varying merit. Round One applications were assessed in their entirety by the relevant state or territory government, but for subsequent rounds the state and territory governments only assessed selected criteria where local knowledge was considered valuable. Based on the outcome of the assessments, and taking into account other value for money considerations and risks associated with each application, applications were prioritised and a recommendation was made to the delegate for their consideration.

3.15 In assessing applications the delegate may ‘choose any combination of dwellings from an application’42, but the delegate ‘must assess applications in accordance with the assessment criteria specified for the call for applications’.43 For Rounds One and Two applications were assessed as a whole, but as the scheme matured assessments began to be made of individual projects within an application. While this may have assisted with identifying projects in higher need areas, the sets of assessment criteria specified in the Regulations made no reference to assessing applications on that basis. As a result, some applicants were unintentionally disadvantaged. Further, in Round Three, some applicants were ultimately unsuccessful because some projects within the applications were not supported by the relevant state or territory government. This resulted in the overall number of dwellings falling below the minimum requirement of 1000, with the application being set aside. As a consequence some meritorious projects may not have been supported.

Assessment criteria—priority areas of interest

3.16 Each set of criteria for Rounds One to Three also included ‘priority areas of interest’. The Application Guidelines state that these priorities were not mandatory, but the Round One Application Guidelines indicated that compliance with them was more likely to attract higher scores during the assessment process. In communicating the assessment criteria and priority areas to potential applicants in Round One, ‘proposals for rental dwellings that will become available between 1 July 2008 and 30 June 2010’44 was interpreted by the department to mean proposals that included dwellings that would become available during 2008–09. Despite this, 18 per cent of Round One applications were for dwellings not expected to become available until after 30 June 2010.

3.17 In some circumstances the priority areas of interest were viewed by the department as discretionary, although they formed a substantive part of the set of assessment criteria, as set out in the Regulations, indicating that the priority areas of interest were not discretionary. From Round Four onwards, the use of ‘priority areas of interest’ was discontinued in favour of criteria subsets.

Minimum or benchmark scores

3.18 Benchmark or minimum scores were used to support the assessment of applications for the majority of criteria across the rounds. Generally, the benchmark score to be met was a numeric score that aligned with a descriptor of ‘meets criterion’. In most instances applications were required to meet the benchmark score for each criterion in order to be recommended to the delegate. Based on analysis of a sample of applications from each round, some proposals which did not meet the benchmark scores for each criterion, but that scored well in aggregate, were recommended to the delegate for approval.

Financial viability assessment

3.19 Across all rounds the assessment of financial and organisational viability was contracted out to external service providers. Applicants were required to submit their most recent audited financial statements, projected cash flow analysis, details of project costs, financing arrangements, and the planning, development and construction status of the nominated projects.

3.20 The methodology used to assess the financial viability of proposals and applicants varied across rounds. For example, in Round Two, one service provider assessed the financial viability of each individual project, with a second service provider engaged to assess the financial viability and risk profile of the applicant. In the later rounds, financial assessment of both proposals and applicants was completed by one service provider. For proposals consisting of multiple projects, the service provider assessed one project from each proposal. The assessment process was based around the achievement of a benchmark score, and the results of the financial viability assessment were taken into consideration when making recommendations to the delegate.

3.21 In the early rounds, in agreement with the state and territory governments, the financial viability assessment tool was not made public, and as a result, applicants did not have access to information about how financial viability was to be assessed. At the conclusion of Round Two, some applicants raised concerns with the department about the lack of transparency which led to an internal review of the delegate’s decision in relation to an application and the underlying assessment process. Not releasing the financial viability assessment methodology was found by the department to be incompatible with the principles of procedural fairness. From Round Four, the Assessment Toolkits were made available to applicants and included details of the financial viability assessment methodology to be used.

Role of the state and territory governments

3.22 NRAS is a national program which is supported by a state and/or territory co-contribution. The Australian Government provides 75 per cent of the funding to approved participants, with the state and territory governments contributing the balance. This may be through in-kind support, including the provision of land, or an annual cash payment. Given the financial commitment being made by the state and territory governments to the scheme, they have played a significant role in assessing applications. In particular, during the early rounds, applicants were required to address priority areas of interest that included whether proposals were consistent with state, territory or local government affordable housing priorities. This requirement could reasonably be interpreted to mean that the state and territory governments could be asked to provide advice to the delegate about the extent to which a proposal met state, territory or local government affordable housing priorities. Nevertheless, it was agreed that the state and territory governments would complete a full assessment of Round One applications and a partial assessment from Round Two onwards.

3.23 In accordance with the Act, the delegate is the sole decision maker for the scheme and during the early rounds the delegates did not offer allocations to applicants which did not have state or territory support. Departmental legal advice relating to the conduct of the early rounds stated that:

whilst the Delegate can place a heavy weight on the support of the relevant State and Territory in making their decision whether or not to make an offer of allocation, the Delegate cannot have their decision shaped by the State or Territory and must consider the individual merits of the application.

3.24 A new set of assessment criteria which formed the basis of the call for applications for Rounds Four, the Shovel Ready Round and Round Five were included in the 11 May 2010 amendments to the Regulations. The amendments included a requirement that ‘the relevant state or territory supports the proposal’45. The inclusion of this criteria normalised pre-existing administrative practice.

Grouping application by state or territory prior to assessment

3.25 In establishing the scheme, the Australian Government agreed with the state and territory governments that 25 per cent of the value of the NRAS annual incentive was to be provided to approved participants by the state and territory governments, as either financial or in kind support. During each round the state and territory governments were requested to provide advice about the level of support to be made available. Based on this advice, the available allocations for each round were divided into separate pools according to how many incentives the state and territory governments would support in their jurisdiction.

3.26 Applications received were grouped by state or territory prior to assessment and were then prioritised within that grouping based on the results of the assessment process. The grouping of applications by state or territory was not consistent with the Regulations. During the early rounds this resulted in applications considered to be of higher overall merit not being supported as the available allocations for the jurisdiction had been exhausted. Consequently, prioritising applications based on the Australian Government’s score and whether the application was supported by the relevant state or territory government may have resulted in a different mix of successful applications.

3.27 In Round One an application that was scored 19 out of a possible 25 by FaHCSIA and that was supported by the relevant state government, did not receive an initial offer of allocations as the available allocations for that state had been used. In contrast, in another state, two applicants were collectively offered 467 incentives although FaHCSIA only scored the applications six and eight respectively. This was below the agreed Round One benchmark score of 10 and accounted for about 15 per cent of Round One offers. It was not possible to replicate similar analysis for the other rounds as insufficient records had been retained by the department.

3.28 The application guidelines for each round made reference to state and territory government affordable housing priorities, and the role of the state and territory governments in assessing applications and providing advice to the Australian Government, but did not discuss the grouping of applications or the process for prioritising applications following assessment. Including this information in the guidelines would have promoted greater transparency of the assessment process.

Use of probity and legal advisers

3.29 To support the application and assessment process, at varying times during the life of the scheme, the department engaged the services of probity and legal advisers. Their main roles were to assist the department with understanding and complying with the regulatory framework under which the scheme operates and other government policy and legislative requirements.

3.30 Probity advisers were engaged at the beginning of each round, and while there was evidence of advice being sought in relation to specific probity issues, the Shovel Ready Round and Round Five were the only rounds for which probity planning was evident with probity plans available. Probity plans could usefully have outlined the underlying probity principles; roles and responsibilities of the Australian, state and territory governments; key probity risks; strategies for communicating with applicants; and processes for managing conflicts of interest, confidentiality and other probity risks. A sound approach would have been for the probity advisers to develop a probity plan for each round in consultation with the department, with the plans submitted to and endorsed by the delegate.

3.31 Despite a probity adviser being engaged to support the conduct of each of the rounds, insufficient consideration was given to the requirements of the Regulations when developing the Application Guidelines, the NRAS Guidelines and the Assessment Plans for the early rounds. At the completion of Round One, the probity adviser reported to the department that ‘the assessment process was conducted in accordance with the process stated in the Assessment Guidelines and Application Assessment Plan [and] [a]s a result, the integrity of the process can be demonstrated.’ The probity adviser also informed the department that the first round had complied with Australian Government probity principles and considered that the ‘…selection process undertaken meets Commonwealth Procurement Guidelines requirements’. The scheme is enabled through legislation and operates as a regulatory program, and as such was not a procurement. Internal legal advice in December 2009 recommended that the department reconsider the role of the probity adviser in future rounds. In particular, noting that experience in administrative law would bolster the quality of the advice expected to be provided to the department.

3.32 The department was also unable to provide evidence of consistent and substantive engagement with the legal service advisers during the early stages of NRAS. The lack of engagement may have contributed to some of the confusion around the operational aspects of the scheme. The involvement of the department’s legal services significantly increased from late 2009 following a Round Two applicant seeking both an internal and judicial review of a decision of the delegate, in relation to not receiving an offer of allocations under the main part of Round Two. At the completion of the internal review, and in light of the adverse findings made, the delegate subsequently supported the making of an offer of 350 reserved allocations to the applicant.

3.33 While the internal review related specifically to the assessment of one particular application, there were flow on consequences for the application process more generally. In reviewing the suite of documents including the Application Guidelines and NRAS Guidelines, the department’s internal legal services identified ‘significant procedural fairness issues’ with the original decision making process. In particular:

- the benchmark scores against which applications were assessed were not clearly communicated to applicants;

- applicants were not given an opportunity to respond to adverse findings before decisions were made; and

- there was the possible perception that policies had been applied inflexibly.

3.34 At the time of the internal review, the department had already made a call for Round Three applications and released the supporting Application Guidelines. As mentioned in paragraph 3.7, the department’s legal services subsequently recommended that the Round Three Assessment Tool be amended and published and that in relation to Round Four, a complete rewrite of the documentation be undertaken. DSS advised that it does not have a record of the documents being amended and publicly rereleased. The Round Four application guidance documents provided applicants with greater detail about the assessment process and the process for appealing a decision. The Assessment Toolkits were also published which provided guidance to applicants about benchmark scores and their application.

Advice to the delegate/decision maker

3.35 The decision making arrangements for NRAS are based on the requirements of the Act and Regulations. The Secretary is the nominated decision maker, but responsibility for approving applications and other key administrative decisions were delegated to other senior officers within the department, as allowed for by the Act.

3.36 In deciding whether to make offers of allocations or reserved allocations to applicants, the respective delegates have relied on written advice from the department, presented as consolidated assessment reports or individual application assessments. The views of the state and territory governments were also considered. As discussed in paragraphs 3.22 to 3.24, offers of allocations to applicants in Rounds One and Two were only made to applicants where their application was supported by the relevant state or territory government. This position was further advanced in Round Three where it was stated in the Assessment Plan that:

The Commonwealth Decision Maker’s policy in relation to offers of Allocation and Reserved Allocation is to only offer Allocations or Reserved Allocations to those Applicants whose Applications are also supported by the relevant State or Territory, noting that this policy cannot be applied inflexibly, and consideration of individual circumstances must be undertaken by the Commonwealth Decision Maker.

3.37 In determining whether to make an offer of allocations to an applicant, the delegates have relied on the department to provide all relevant information to enable the making of informed decisions, consistent with the requirements of the scheme, government policy and administrative law. Issues in relation to the decision-making processes were brought to the attention of the then delegate in late 2009, when the delegate was advised that:

The Department has become aware that some of the assessment processes used to make recommendations to the decision maker on whether or not to make allocations of [National Rental Incentives] under the NRAS, may not discharge the decision maker’s legal obligation to make administrative decisions consistently with rules of procedural fairness.

3.38 To improve the decision making process, in April 2010 the delegates participated in a decision making workshop. The advice to the delegates in relation to Rounds Three and Four was more comprehensive with matters such as the application of state or territory requirements in relation to residential tenancy and the how proposals would contribute to longer-term housing outcomes discussed. During the Round Four assessment process the delegate was also verbally briefed by an officer from the assessment team about the assessment outcomes providing an opportunity for the delegate to seek clarification of matters and/or additional information to inform the decision-making process.

4. Management of reserved allocations

Areas examined

The ANAO examined the frameworks for reviewing variation requests, the approval of variation requests and the impact of approved variations on the delivery of eligible dwellings into the scheme. This included consideration of whether incentives allocated or reserved were managed in accordance with the conditions set out in the Regulations.

Supporting findings

- Only limited consideration was given to the risk that approved participants would not be able to deliver dwellings into the scheme and the Regulations as originally drafted, did not provide a legal basis for approved participants to request variations to the conditions of reserved allocations.

- The early guidance to approved participants and internal policy guidance did not establish a framework for the assessment of variation requests, but as understanding of the operating environment evolved, the Regulations were amended and the processes for managing variation requests were formalised.

- Due to the poor quality of the records retained over the life of the scheme, there is no complete record of dwellings as originally approved and/or subsequent approved changes.

- The capacity of approved participants to deliver dwellings in accordance with the agreed conditions of reserved allocations and/or approved variations should have been given greater consideration during the assessment of variation requests.

- Since the start of NRAS through to 10 April 2015, in excess of 145 000 changes of location, size, style or expected availability had been made to reserved allocations.

- Changes to the agreed available for rent date resulted in the peak period for delivery of dwellings shifting from the 2011 to 2013 NRAS years into the 2013 to 2015 NRAS years.

- Emerging risks relating to the achievement of the scheme’s objectives and outcomes were drawn to the attention of successive governments, largely from late 2012. However, this advice prior to 2014, did not adequately canvas options for improving the delivery of dwellings into the scheme, or provide advice to Government about the shortcomings of the policy design and approach, and the likelihood that the program would not fully achieve its intended outcomes.

Key learnings

- Evaluating programs with a focus on understanding their impact, whether the policy objectives and expected outcomes are being achieved, and whether the underlying policy approach is an effective intervention.

- Departments drawing to the attention of the Government, as early as possible, key risks and shortcomings in policy design and the likelihood that policy measures may not fully achieve their intended objectives or outcomes.

- Creating and maintaining a minimum standard of documentation in relation to administrative processes and decisions in order to support accountability and transparency.

NRAS allocations and reserved allocations

4.1 Following the assessment of applications, offers of allocations or reserved allocations were made to successful applicants. An offer of allocations was made to applicants where eligible dwellings were available for rent, while reserved allocations are a conditional offer for dwellings that are expected to become available at a later date. The conditions pertaining to reserved allocations have generally related to the location, style, size and expected timeframe for the delivery of each associated dwellings.

4.2 Analysis of NRAS data indicates that as at 10 April 2015 there were 37 679 allocations and reserved allocations. Of these, 26 234 were allocations, and 11 445 were reserved allocations, including one provisional allocation.46 A further 8390 allocations or reserved allocations were no longer available through the scheme, having been withdrawn or revoked.

4.3 Management of the stock of reserved allocations is a key part of the administration of NRAS. Since March 2009, more than 145 000 changes to the conditions of reserved allocations have been made.47 On average, nearly four changes have been made to each of the dwellings currently available or expected to become available through NRAS. Table 4.1 presents information about the number of changes to the agreed available for rent date, location, style and size of dwellings.

Table 4.1: Changes to eligible dwellings

|

Financial Year |

Number of changes affecting dwellings |

|||||||

|

|

Agreed rental availability date |

Location1 |

Style |

Size |

||||

|

|

Changes |

Dwelling2 |

Changes |

Dwelling2 |

Changes |

Dwelling2 |

Changes |

Dwelling2 |

|

2008–09 |

803 |

803 |

165 |

164 |

178 |

178 |

309 |

309 |

|

2009–10 |

4 109 |

4 039 |

1 888 |

1 861 |

908 |

908 |

1 209 |

1 207 |

|

2010–11 |

6 578 |

5 333 |

6 527 |

4 997 |

990 |

961 |

1 678 |

1 562 |

|

2011–12 |

12 384 |

11 051 |

15 249 |

10 089 |

2 163 |

2 125 |

2 964 |

2 888 |

|

2012–13 |

12 631 |

11 204 |

20 186 |

13 726 |

2 576 |

2 336 |

3 535 |

3 228 |

|

2013–14 |

7 471 |

6 936 |

17 486 |

12 219 |

2 404 |

2 344 |

3 082 |

3 029 |

|

2014–15 |

6 159 |

5 189 |

9 694 |

7 715 |

986 |

978 |

1 573 |

1 560 |

|

Total |

50 135 |

29 191 |

71 195 |

32 448 |

10 202 |

8947 |

14 350 |

12 129 |

|

Average |

1.7 changes/dwelling |

2.2 changes/dwelling |

1.1 changes/dwelling |

1.2 changes/dwelling |

||||

Note 1: The location count includes in excess of 40 000 records where the approved participant may have updated an existing street address in FOFMS without submitting a variation request. Excluded from the table are changes to the street address of dwellings where the field in FOFMS was updated from blank or otherwise undefined (this was not considered a variation under the NRAS Regulations based on legal advice). Also excluded are variations to dwellings where the geographical location changed in FOFMS without any other identifiable change in the manually updated location fields in FOFMS.

Note 2: Individual dwellings may be included in the count for more than one financial year where changes were made in multiple years; the total number of dwellings only identifies a dwelling once.

Source: ANAO analysis of FOFMS data.

Framework for varying reserved allocations