Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Australia’s COVID-19 Vaccine Rollout

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- The distribution and delivery of COVID-19 vaccines has been one of the largest exercises in health logistics in Australian history. COVID-19 and the vaccine rollout have impacted upon every person in Australia.

- This performance audit was conducted under phase two of the ANAO’s multi-year strategy that focuses on the effective, efficient, economical and ethical delivery of the Australian Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Key facts

- As at 1 July 2022, there had been 8.2 million reported cases of COVID-19 in Australia and 9,930 deaths.

- The Australian Government spent more than $8 billion on COVID-19 vaccines.

- During 2021, 42.6 million COVID-19 vaccine doses were administered.

What did we find?

- The Department of Health and Aged Care’s (Health’s) planning and implementation of the COVID-19 vaccine rollout has been partly effective.

- Health’s approach to planning became more effective as the rollout progressed.

- The final governance arrangements established to manage the COVID-19 vaccine rollout have been largely effective.

- Implementation of the COVID-19 vaccine rollout has been partly effective, with Health’s administration of vaccines to priority populations and the general population not meeting targets.

What did we recommend?

- The Auditor-General made two recommendations relating to: improving data quality and IT controls; and conducting a comprehensive review of the rollout to identify opportunities for improvement in the event of a future vaccine rollout.

- Health agreed to both recommendations.

90.2%

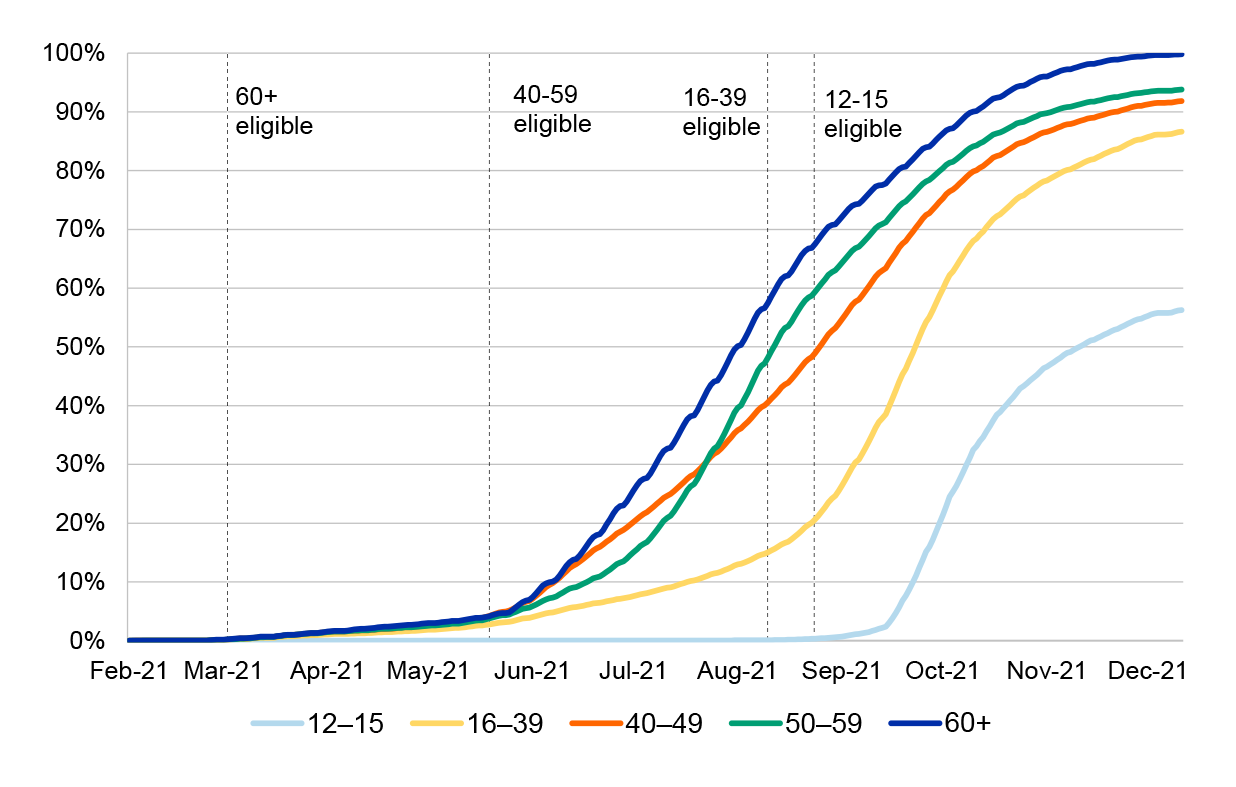

Percentage of people aged 12 or over in Australia double vaccinated by 31 December 2021.

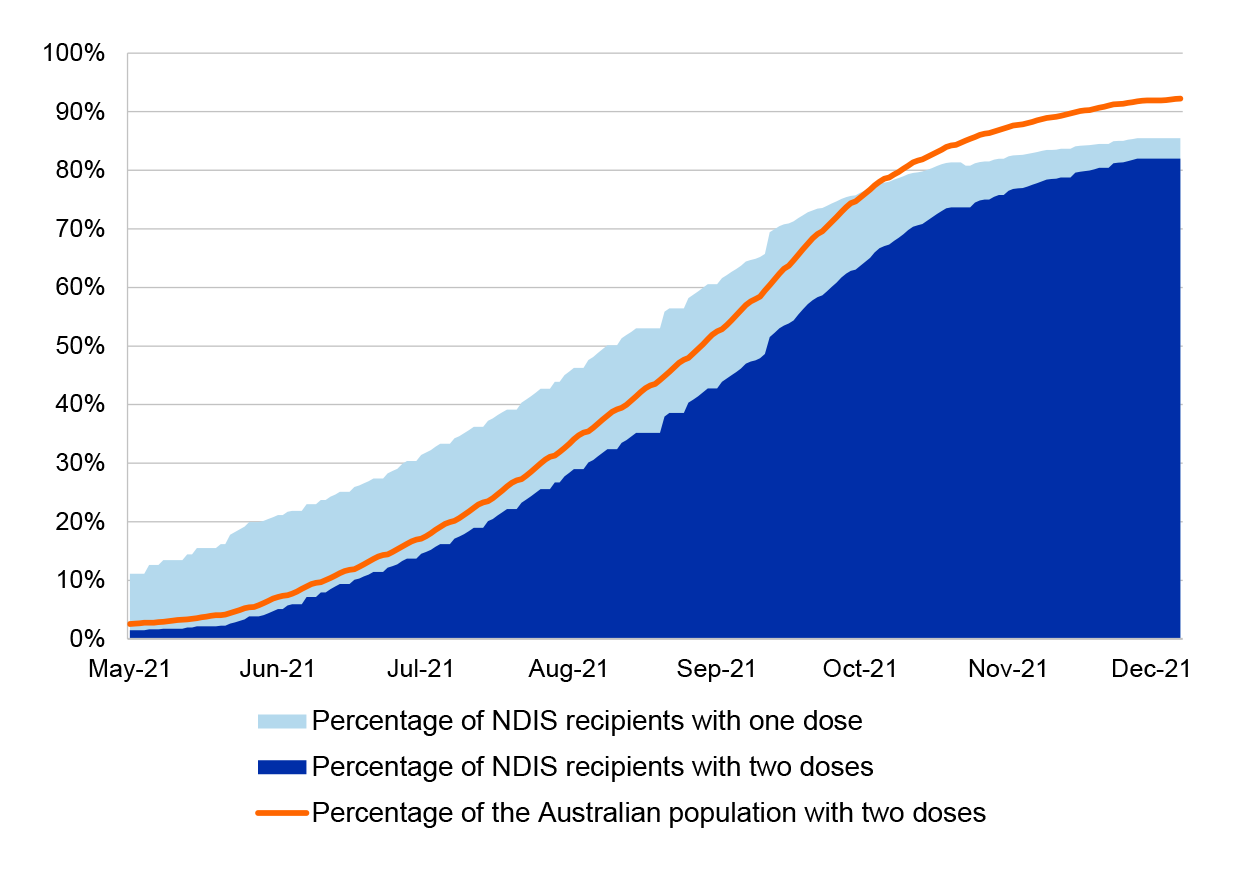

87.2%

Percentage of residential aged care facility residents double vaccinated by 10 January 2022.

82.0%

Percentage of residential disability facility residents double vaccinated by 31 December 2021.

63.5%

Percentage of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 12 or over double vaccinated by 31 December 2021

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Since its emergence in late 2019, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has become a global pandemic that is impacting on human health and national economies. On 21 January 2020, the Australian Government declared COVID-19 as a listed human disease under the Biosecurity Act 2015 (Biosecurity Act). The World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 to be a ‘public health emergency of international concern’ on 30 January 2020.

2. Early Australian Government responses to COVID-19 included:

- travel restrictions, international border controls and quarantine arrangements;

- delivery of substantial economic stimulus, including financial support for affected individuals, businesses and communities; and

- support for essential services and procurement and deployment of critical medical supplies (including the national vaccine rollout).

3. The Australian Government’s August 2020 Australia’s COVID-19 vaccine and treatment strategy committed the government to building a ‘diverse global portfolio of investments to seek to secure early access to promising vaccines and treatments’, using local manufacturing wherever possible.1 Between September 2020 and May 2021, the Australian Government entered into agreements with five vaccine manufacturers to purchase a total of 315.3 million vaccines of different types, with some vaccines being manufactured overseas and some produced locally.

4. The Department of Health and Aged Care (Health)2 has been the lead entity for the COVID-19 vaccine rollout. The COVID-19 vaccine rollout commenced on 22 February 2021. As at 30 December 2021, Health reported that 42,598,706 doses had been administered nationally with 18,845,485 people having been fully vaccinated.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

5. The COVID-19 pandemic and the pace and scale of the Australian Government’s response impacts on the risk environment faced by the Australian public sector. This performance audit was conducted under phase two of the ANAO’s multi-year strategy that focuses on the effective, efficient, economical and ethical delivery of the Australian Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.3

6. The distribution and delivery of COVID-19 vaccines has been one of the largest exercises in health logistics in Australian history. The COVID-19 vaccine rollout has required rapid and flexible planning, decision-making and implementation, to respond to the changing health, social and economic impacts of COVID-19, as well as the effective and timely acquisition and distribution of vaccines once they were created. The audit was conducted to provide independent assurance to the Parliament that Australia’s COVID-19 vaccine rollout was planned and implemented effectively.

Audit objective and criteria

7. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the planning and implementation of the COVID-19 vaccine rollout.

8. To form a conclusion against this objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted.

- Has the approach to planning Australia’s COVID-19 vaccine rollout been effective? (Chapter 2)

- Have effective governance arrangements been established to manage the COVID-19 vaccine rollout? (Chapter 3)

- Has the COVID-19 vaccine rollout been effectively implemented? (Chapter 4)

Conclusion

9. Health’s planning and implementation of the COVID-19 vaccine rollout has been partly effective. While 90 per cent of the eligible Australian population was vaccinated by the end of 2021, the planning and implementation of the vaccine rollout to priority groups was not as effective.

10. Health’s approach to planning Australia’s vaccine rollout became more effective as the rollout progressed. Health undertook largely appropriate planning to establish administration channels and logistics for the rollout and developed a fit-for-purpose communication strategy. Initial planning was not timely, with detailed planning with states and territories not completed before the rollout commenced, and Health underestimated the complexity of administering in-reach services to the aged care and disability sectors. Further, it did not incorporate the government’s targets for the rollout into its planning until a later stage. Health identified and continually reassessed risks to the rollout, adapting its planning in response to realised risks.

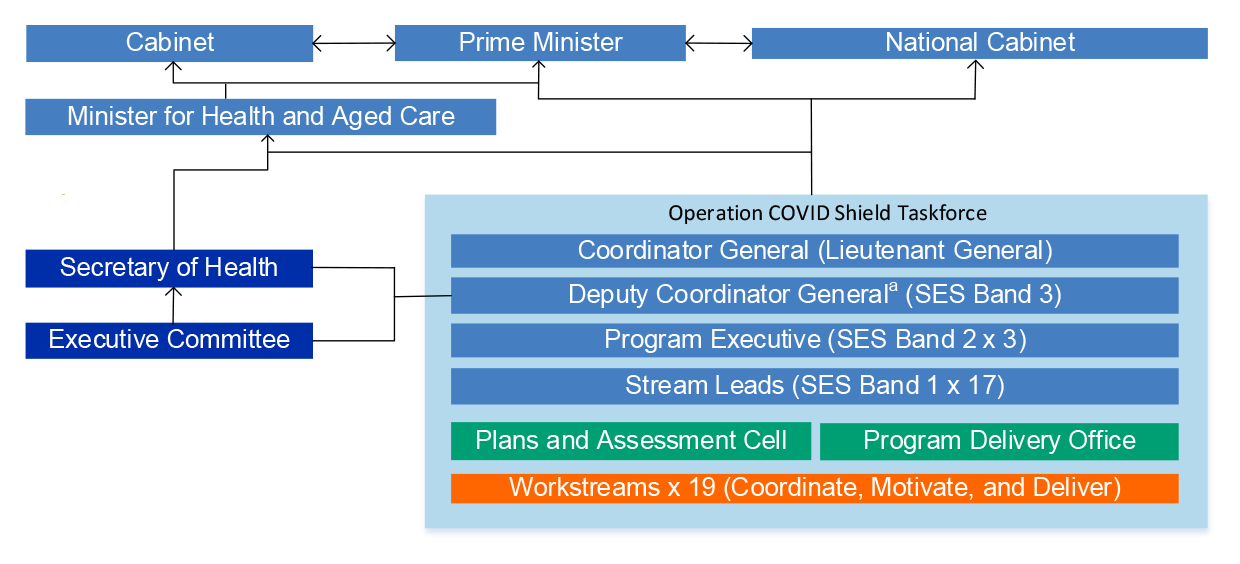

11. The final governance arrangements established to manage the COVID-19 vaccine rollout have been largely effective. Following the commencement of Operation COVID Shield in June 2021, senior level oversight of the program substantially increased. Health regularly consulted with four sector-specific stakeholder advisory groups. Health put in place effective monitoring and reporting arrangements using the best available data. However, it did not undertake sufficient reporting against targets, and it does not have adequate assurance over the completeness and accuracy of the data and third-party systems.

12. Health’s implementation of the COVID-19 vaccine rollout has been partly effective. While vaccines were delivered with minimal wastage, Health’s administration of vaccines to priority populations and the general population has not met targets. The vaccine rollout to residential aged care and residential disability were both slower than planned, and the vaccination rate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people has remained lower than for the Australian population. Health implemented its communication strategy, but its advertising campaign has not yet been evaluated.

Supporting findings

Vaccine rollout planning

13. The commencement of planning for the rollout was not timely and early planning did not include target dates for the rollout. Detailed engagement with the states and territories on rollout planning did not begin until November 2020 and Jurisdictional Implementation Plans were not agreed until February 2021, by which time the rollout of COVID-19 vaccines had already commenced. Initial planning on the prioritisation of vaccinations to vulnerable and at-risk groups was based on advice from the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation, an expert committee. Planning continued throughout the rollout. In June 2021, the Prime Minister announced the replacement of Health’s rollout taskforce with new Operation COVID Shield and a new Op COVID Shield National COVID Vaccine Campaign Plan was released in August 2021. Health subsequently developed a series of sub-plans which contained lower-level target dates for vaccinating specific priority groups and sectors. (See paragraphs 2.3 to 2.37)

14. Risks to the rollout were identified from June 2020. In January 2021, Health established a comprehensive risks and issues register which was used throughout 2021 to identify risks to the rollout. Risks were kept under regular review and, where necessary, corrective action was determined. The most significant risks and issues were referred to the taskforce leadership for review. (See paragraphs 2.38 to 2.47)

15. Health worked with state and territory authorities and relevant stakeholders to consider and establish a variety of administration channels that were suitable for priority groups and the population as a whole. Two logistics providers were engaged to transport and deliver vaccines throughout Australia. Health underestimated the magnitude and complexity of rolling out in-reach services for the residential aged care and disability sectors and did not engage sufficient in-reach providers early in the rollout. (See paragraphs 2.48 to 2.57)

16. Health developed a fit-for-purpose strategy for communicating the vaccine rollout. The communication strategy and its supporting advertising strategy identified target audiences and was tailored to addressing the concerns of these groups as determined through market research. The advertising strategy complied with government guidelines for advertising campaigns and had a plan to monitor progress. (See paragraphs 2.58 to 2.73)

Governance

17. Fit-for-purpose governance arrangements were established for the vaccine rollout following the commencement of Operation COVID Shield in June 2021. Senior level oversight of the program also substantially increased. Responsibilities of the Australian, state and territory governments and other stakeholders were documented in the Australian COVID-19 vaccination policy, Jurisdictional Implementation Plans and sector specific implementation plans. (See paragraphs 3.3 to 3.19)

18. Health put in place systems to monitor the vaccine rollout but does not have adequate assurance over the completeness and accuracy of the data and third-party systems. Health provided decision makers and the public with regular and detailed updates on the vaccine rollout that were tailored and developed using the best available data. These reports did not include progress against targets until August 2021. (See paragraphs 3.20 to 3.38)

19. Health developed a stakeholder engagement plan for the rollout, which assessed stakeholders based on their needs, influence, and impact on the program. Health received advice on the rollout from four sector-specific advisory groups that were established for the COVID-19 response. Feedback on the vaccine rollout from key stakeholders contacted by the ANAO was mixed. (See paragraphs 3.39 to 3.54)

Implementation

20. Vaccines were delivered within agreed logistics timeframes and with minimal wastage, with 60 per cent of vaccines administered through Australian Government managed channels. Health had a principle of allocating vaccines to states and territories on a proportional basis, however issues such as logistical constraints and responses to COVID-19 hotspots meant that allocations were not proportional in the early stages of the rollout. Health did not meet the government’s original target to ‘have the country vaccinated’ before the end of October 2021. (See paragraphs 4.3 to 4.29)

21. Health’s administration of the vaccine rollout to the residential aged care and disability sectors was slower than planned, due to Health initially contracting insufficient vaccine administration providers and other planning and implementation issues. Health’s target for the vaccination rate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to be equal to or greater than the national target [80 per cent] has not been met in 2021. (See paragraphs 4.30 to 4.65)

22. Health’s communication about the vaccine rollout has been largely consistent with its communication strategy, and its monitoring of public sentiment has shown attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccination improved over time. Health implemented communication activities targeted at Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and culturally and linguistically diverse communities, but these activities were not as effective at reaching these groups as communication to the general population. Health has not yet conducted an evaluation of the effectiveness of the advertising campaign as the campaign is ongoing. (See paragraphs 4.66 to 4.76)

Recommendations

Recommendation no. 1

Paragraph 3.25

The Department of Health and Aged Care establish processes, including during public health emergencies, to ensure it regularly obtains and reviews assurance over the data quality and IT controls in place in externally managed systems on a risk basis, including IT security, change management and batch processing.

Department of Health and Aged Care response: Agreed

Recommendation no. 2

Paragraph 3.55

Before 31 December 2022, the Department of Health and Aged Care conduct a comprehensive review of the COVID-19 vaccine rollout which:

- invites contribution from all key government and non-government stakeholders;

- examines all aspects of the COVID-19 vaccine rollout;

- identifies what worked well and what did not; and

- makes recommendations to the Australian Government about opportunities for improvement in the event of a future vaccination rollout.

Department of Health and Aged Care response: Agreed

Summary of entity response

23. Health’s summary response is provided below and its full response is included at Appendix 1.

The Department of Health and Aged Care (the Department) welcomes the findings in the report and the recommendations directed to the Department. The Department is committed to effective implementation of recommendations and has already commenced steps to address the issues identified in this audit.

It was pleasing to note the audit recognises the significant planning, consultation and engagement that underpinned the vaccine rollout. I also note the acknowledgement of appropriate governance and risk management processes developed through the rollout, and the fit-for-purpose communication strategy that informed Australians and key stakeholders on the vaccine program. The audit also found that vaccines were delivered within agreed logistics timeframes and with minimal wastage.

The audit found some shortcomings on assurance received over the completeness and accuracy of the data and third-party systems that underpinned the vaccine rollout. To address this finding the Department plans to undertake a review of IT controls for data received from externally managed systems. The audit also recommended the Department undertake a comprehensive review of the vaccine rollout. The Department notes that such a review would logically form part of an expected broader review into the COVID-19 pandemic with the timing still to be agreed by Government.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Policy/program implementation

Governance and risk management

Performance and impact measurement

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Since its emergence in late 2019, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has become a global pandemic that is impacting on human health and national economies. On 21 January 2020, the Australian Government declared COVID-19 as a listed human disease under the Biosecurity Act 2015 (Biosecurity Act).4 The World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 to be a ‘public health emergency of international concern’ on 30 January 2020.

1.2 From January 2020, the Australian Government commenced the introduction of a range of policies and measures in response to the emergence of COVID-19. On 18 March 2020, in response to the pandemic in Australia, the Governor-General of the Commonwealth of Australia declared that a human biosecurity emergency exists.5

1.3 The Australian Government’s health and economic response has included:

- travel restrictions, international border controls and quarantine arrangements;

- delivery of substantial economic stimulus, including financial support for affected individuals, businesses and communities; and

- support for essential services and procurement and deployment of critical medical supplies (including the national vaccine rollout).

1.4 With the release of the 2022–23 Budget on 29 March 2022, the Australian Government reported that it had committed $314 billion to economic response measures.6 In addition, as at April 2022, the Australian Government had committed more than $45 billion to the COVID-19 health response, including more than $8 billion related to COVID-19 vaccines and booster doses.

Development, approval and acquisition of COVID-19 vaccines

1.5 The Australian Government’s initial response to COVID-19 was contained in the Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19), which was published on 18 February 2020.7 The plan focussed on measures to reduce transmission, minimise the burden on health systems and ‘inform, engage and empower the public’. It also noted that ‘availability of a customised novel coronavirus vaccine would be the greatest tool in reducing the impact [of COVID-19]’ and committed the Australian Government to:

fast-track assessment and approval of a customised vaccine, should this become available; procure vaccines; develop a national novel coronavirus vaccination policy and a national novel coronavirus immunisation program; and communicate immunisation information on the program to the general public and health professionals.8

1.6 Australia has had mass vaccination campaigns since 1924. In 1997, the Australian, state and territory governments jointly established the National Immunisation Program (NIP)9, which currently provides free vaccination against 17 diseases for babies, young children, teenagers and older Australians.10 The NIP has achieved very high immunisation rates, particularly for children.

Development and approval of COVID-19 vaccines

1.7 From January 2020, research organisations and pharmaceutical companies worldwide began developing and testing COVID-19 vaccines at unprecedented speeds.11 The vaccines developed ranged from viral vector and protein vaccines, such as the Oxford AstraZeneca viral vector vaccine (AstraZeneca), to new genetic vaccines, such as the mRNA Pfizer vaccine (Pfizer).

1.8 The Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), which forms part of the Department of Health and Aged Care (Health)12, is Australia’s regulatory authority for therapeutic goods.13 The TGA assessed COVID-19 vaccines for safety, quality and effectiveness before they could be supplied in Australia.14 While achieving full registration for a therapeutic good such as a vaccine can take several years, where the TGA assesses that the benefit of early availability outweighs the risk inherent in the fact that additional data are still required, it can provisionally register the vaccine. All COVID-19 vaccines used in Australia have used the provisional registration process.15

1.9 Once the TGA approves use of a therapeutic good, it monitors the use of the product to identify potential safety issues. The TGA has monitored the COVID-19 vaccine to identify adverse effects since 22 February 2021 and published a weekly safety report on any issues identified.

Australia’s acquisition of COVID-19 vaccines

1.10 By mid-2020, many potential COVID-19 vaccine candidates had entered clinical trials and countries such as the United States began entering into advance purchase agreements with pharmaceutical companies.16

1.11 In August 2020, the Australian Government established the Science and Industry Technical Advisory Group (SITAG) to ‘support the Australian Government to make decisions about purchasing and manufacture of COVID-19 vaccines and treatments’. SITAG’s terms of reference state that its purpose is to provide advice on:

- the scientific validity of research into safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccine candidates;

- potential purchasing arrangements for COVID-19 vaccine candidates for Australia;

- the scientific validity of research into new therapeutics for COVID-19, including tests and treatments;

- potential purchasing arrangements for COVID-19 therapeutics for Australia;

- the viability of options for manufacturing and packaging COVID-19 vaccines and treatments in Australia;

- distribution and logistics associated with COVID-19 vaccine candidates; and

- other technical matters related to COVID-19 vaccines and treatments, as requested by the Chair.17

1.12 In August 2020, the Australian Government released Australia’s COVID-19 vaccine and treatment strategy, which committed the Australian Government to building a ‘diverse global portfolio of investments to seek to secure early access to promising vaccines and treatments’, using local manufacturing wherever possible.18 The criteria which were used to guide investment decisions were:

- availability of the vaccine candidate in 2021;

- experience in the technology platform;

- the track record of the company or partner company in vaccine development;

- complexities involved in the distribution and administration of the candidate (such as the temperature at which they must be stored and transported prior to administration19);

- the likely volume able to be secured in 2021;

- the clinical trial stage reached; and

- costs related to securing candidates.

1.13 Vaccine efficacy was not one of the factors taken into account in the initial selection of vaccines for purchase. This was because, at that time, none of the vaccines being considered had reached Phase 3 clinical trials where efficacy is tested.20

1.14 Commencing in August 2020, Health presented SITAG with information about a number of vaccine candidates and sought its endorsement to proceed with negotiations with the five companies which produced the vaccines that were ultimately purchased (see Table 1.1). Health then sought the government’s approval to proceed with advance purchase agreements with the selected companies.

Table 1.1: Australia’s COVID-19 vaccine purchase agreements

|

Vaccine |

Number of doses per agreementa (millions) |

Total number of doses per vaccine (millions) |

Date agreement announced |

Vaccine type |

Approved by TGA |

|

|

AstraZeneca (Vaxzevria) |

33.8 |

56.3 |

07/09/2020 |

Viral vector |

✔ |

15/02/2021 |

|

22.5 |

11/12/2020 |

|||||

|

University of Queensland |

51.0 |

51.0 |

08/10/2020 |

Protein |

✘ |

N/Ab |

|

Pfizer (Comirnaty) |

10.0 |

131.0 |

05/11/2020 |

mRNA |

✔ |

25/01/2021 |

|

10.0 |

04/02/2021 |

|||||

|

20.0 |

09/04/2021 |

|||||

|

0.5c |

13/5/2021 |

|||||

|

85.0 |

25/07/2021 |

|||||

|

1.0 |

15/08/2021 |

|||||

|

0.5d |

31/08/2021 |

|||||

|

4.0e |

03/09/2021 |

|||||

|

Novavax (Nuvaxovid) |

40.0 |

51.0 |

05/11/2020 |

Protein |

✔ |

19/1/2022 |

|

11.0 |

11/12/2020 |

|||||

|

Moderna (Spikevax) |

25.0 |

26.0 |

13/05/2021 |

mRNA |

✔ |

09/08/2021 |

|

1.0f |

1/9/2021 |

|||||

|

Total number of doses purchased (millions) |

315.3 |

|||||

|

Total number of doses purchased that received TGA approval (millions) |

264.3 |

|||||

Note a: Agreements include advance purchase agreements with vaccine manufacturers and agreements with nations to purchase additional vaccine stock.

Note b: The University of Queensland vaccine did not proceed past human trials in December 2020.

Note c: 513,630 Pfizer doses purchased from the COVAX facility.

Note d: 500,000 Pfizer doses were ‘swapped’ with Singapore in August 2021 and repaid in November 2021.

Note e: Four million Pfizer doses were ‘swapped’ with the United Kingdom in September 2021 and repaid in late 2021.

Note f: One million Moderna doses were purchased from European Union member states in September 2021.

Source: ANAO analysis of Health documents and press releases by the Minister for Health and Aged Care and the Prime Minister.

Australia’s COVID-19 vaccine rollout

1.15 Health has been responsible for managing Australia’s COVID-19 vaccine rollout.

1.16 Health published the Australian COVID-19 vaccination policy on 13 November 2020, which included key principles relating to the vaccine rollout.21 On 7 January 2021, based on advice from the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI), Health published Australia’s COVID-19 vaccine national roll-out strategy, which outlined a three-phase rollout strategy commencing with priority populations.22

1.17 Australia’s COVID-19 vaccine rollout was launched on 22 February 2021 with the provision of the Pfizer vaccine to individuals in Phase 1a (which included quarantine, border and frontline healthcare workers and aged care and disability care residents and staff).23 The AstraZeneca vaccine was made available from March 2021, with the first dose of AstraZeneca administered in Australia on 5 March 2021.

1.18 In early March 2021, reports began to circulate globally of a rare but potentially serious side-effect of AstraZeneca. ATAGI monitored these reports and published several updates. On 8 April 2021, ATAGI updated its advice, recommending the use of Pfizer as the preferred vaccine for eligible people under 50 years of age.24 As a result, Health ‘recalibrated’ the rollout, including by changing the recommended age ranges for some population groups.

1.19 Until June 2021, the rollout was administered by a taskforce within Health. In June 2021, the Prime Minister appointed Lieutenant General John (JJ) Frewen DSC AM as the Coordinator General of Operation COVID Shield.25 The Coordinator General assumed control of the taskforce and was directed by the Prime Minister to report directly to him and the Minister for Health and Aged Care, while working closely with the Secretary of Health.

1.20 By 31 December 2021, all people aged 12 years and above were eligible, and encouraged, to receive a COVID-19 vaccine. On 8 November 2021, the Australian Government began a vaccine booster program, for people to receive an additional dose of vaccine to provide additional protection. This was initially targeted to priority groups most at risk, such as the elderly and the immunocompromised. From 10 January 2022, the Australian Government expanded eligibility for the program to include those aged five to 11 years.26

1.21 As at 30 June 2022:

- 60.3 million vaccine doses had been administered, 39.0 million of these by Australian Government providers such as pharmacies, general practitioners (GPs) and contracted providers; and

- 19.8 million people aged 16 or over (over 95 per cent) had received at least two vaccine doses.

1.22 Figure 1.1 is a timeline key events that occurred in the lead up to, and during, the vaccine rollout.

Figure 1.1: COVID-19 vaccine rollout key events, 1 August 2020–31 December 2021

Source: ANAO from Health documents.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.23 The COVID-19 pandemic and the pace and scale of the Australian Government’s response impacts on the risk environment faced by the Australian public sector. This performance audit was conducted under phase two of the ANAO’s multi-year strategy that focuses on the effective, efficient, economical and ethical delivery of the Australian Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.27

1.24 The distribution and delivery of COVID-19 vaccines have been one of the largest exercises in health logistics in Australian history. The COVID-19 vaccine rollout has required rapid and flexible planning, decision-making and implementation, to respond to the changing health, social and economic impacts of COVID-19, as well as the effective and timely acquisition and distribution of vaccines once they were created. The audit was conducted to provide independent assurance to the Parliament that Australia’s COVID-19 vaccine rollout was planned and implemented effectively. The audit was identified by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit as an audit priority of the Parliament.

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.25 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the planning and implementation of the COVID-19 vaccine rollout.

1.26 To form a conclusion against this objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted.

- Has the approach to planning Australia’s COVID-19 vaccine rollout been effective? (Chapter 2)

- Have effective governance arrangements been established to manage the COVID-19 vaccine rollout? (Chapter 3)

- Has the COVID-19 vaccine rollout been effectively implemented? (Chapter 4)

1.27 The scope of the audit did not include:

- the procurement of the vaccines selected for use in Australia;

- the administration of vaccinations by state and territory governments, including state and territory vaccine immunisation hubs;

- the safety or effectiveness of vaccines purchased by the Australian Government, or any other matters requiring clinical expertise;

- the administration of vaccines to Australian Government employees overseas (such as Department of Foreign Affairs staff); or

- the donation of vaccines by the Australian Government to countries in the Pacific and Southeast Asia.28

1.28 The audit focused on the period from the first occurrence of COVID-19 in Australia until 31 December 2021. For that reason, there is limited examination of the implementation of the booster program, which began late in 2021, or the implementation of the rollout for children aged five to eleven, which did not begin until 2022.

Audit methodology

1.29 The audit involved:

- reviewing submissions and briefings to the Australian Government;

- reviewing Health’s documentation including meeting papers and minutes, policies, procedures and correspondence;

- analysing data held in systems used by Health;

- meetings with officers from relevant business areas within Health;

- reviewing 22 submissions and meeting with stakeholders in the health sector, state and territory governments and COVID-19 advisory groups29; and

- reviewing 507 contributions received from organisations and individuals via the ANAO’s ‘contribute to this audit’ facility.

1.30 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $845,000.

1.31 The audit team members for this audit were Julian Mallett, Laura Trobbiani, Anne Kent, Sarah Koehler, Olivia Robbins, Elizabeth Wedgwood, Matthew Rigter, Alexander Wilkinson and Daniel Whyte.

2. Vaccine rollout planning

Areas examined

This chapter examines the effectiveness of the Department of Health and Aged Care’s (Health’s) approach to planning Australia’s COVID-19 vaccine rollout.30

Conclusion

Health’s approach to planning Australia’s vaccine rollout became more effective as the rollout progressed. Health undertook largely appropriate planning to establish administration channels and logistics for the rollout and developed a fit-for-purpose communication strategy. Initial planning was not timely, with detailed planning with states and territories not completed before the rollout commenced, and Health underestimated the complexity of administering in-reach services to the aged care and disability sectors. Further, it did not incorporate the government’s targets for the rollout into its planning until a later stage. Health identified and continually reassessed risks to the rollout, adapting its planning in response to realised risks.

2.1 As noted in paragraph 1.24, the distribution and delivery of COVID-19 vaccines have been one of the largest exercises in health logistics in Australian history. When an initiative is urgent, planning and implementation may need to occur quickly or in stages, prioritising critical foundations and building on them later. One of the most pressing priorities is to reduce risk by seeking expert implementation advice and experience as soon as possible in the delivery phase and adjusting policy and/or delivery settings as necessary.

2.2 This chapter examines whether rollout planning was conducted in a timely fashion and based on evidence. It also examines the assessment of risks to the rollout, the logistics and ‘channels’ used to deliver and administer vaccines, and whether a fit-for-purpose communication strategy was developed.

Was planning timely and informed by appropriate evidence?

The commencement of planning for the rollout was not timely and early planning did not include target dates for the rollout. Detailed engagement with the states and territories on rollout planning did not begin until November 2020 and Jurisdictional Implementation Plans were not agreed until February 2021, by which time the rollout of COVID-19 vaccines had already commenced. Initial planning on the prioritisation of vaccinations to vulnerable and at-risk groups was based on advice from the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation, an expert committee. Planning continued throughout the rollout. In June 2021, the Prime Minister announced the replacement of Health’s rollout taskforce with new Operation COVID Shield and a new Op COVID Shield National COVID Vaccine Campaign Plan was released in August 2021. Health subsequently developed a series of sub-plans which contained lower-level target dates for vaccinating specific priority groups and sectors.

2.3 On 7 August 2020, the Prime Minister announced that Australian governments31 had ‘strongly welcomed the Commonwealth Government’s COVID-19 Vaccine and Treatment Strategic Approach that provides a framework for securing early access to safe and effective vaccines and treatments’.32

2.4 Australia’s COVID-19 vaccine and treatment strategy (the vaccine and treatment strategy), released on 18 August 2020, stated that the government was ‘working in five areas to deliver safe and effective COVID-19 vaccines and treatments’: research and development; purchase and manufacturing; international partnerships; regulation and safety; and immunisation administration and monitoring.33

2.5 On 13 November 2020, Health published the Australian COVID-19 vaccination policy (the vaccination policy).34 The vaccination policy set out ‘the key policy parameters and approach to providing COVID-19 vaccines’, including high-level information on:

- roles and responsibilities of the Australian, state and territory governments and other key stakeholders in a COVID-19 pandemic vaccination program;

- information on the vaccines purchased by the Australian Government;

- key features of the vaccination program, including how doses would be made available to priority population groups and where and how vaccination would take place;

- how vaccine safety would be monitored;

- how data would be collected and reported; and

- how information on COVID-19 vaccines and vaccination would be made available to consumers and clinicians.

Rollout planning to June 2021

2.6 The vaccine and treatment strategy (released on 18 August 2020) stated that ‘Australian Government agencies are working with states and territories on transportation, storage and distribution plans. This will ensure vaccines, syringes and needles can be moved and stored securely and distributed rapidly’. However, although Health advised that it had monthly meetings between July and November 2020 with states and territories about ‘COVID planning’, the evidence shows that detailed engagement with the states and territories on rollout planning did not begin until November 2020.

2.7 At a meeting of state and territory health authority chief executive officers (CEOs) on 6 November 202035, Health outlined a number of key principles and assumptions for the rollout, which were:

- the rollout would not initially be administered under the National Immunisation Program (NIP)36;

- the rollout would be free for all Australian citizens, permanent residents, and most visa-holders37;

- vaccination would not be mandatory, but encouraged and likely incentivised;

- vaccination would be rolled out on the basis of identified priority populations, linked to delivery schedules, with scope for outbreak response; and

- the Australian Government would oversee the rollout, with defined responsibilities for the Australian, state and territory governments and shared governance.

2.8 A document prepared for the meeting emphasised that ‘connectivity of implementation plans and clear responsibilities are crucial’ and stated that individual Jurisdictional Implementation Plans (JIPs) were intended to be developed between the Australian Government and each state and territory government. The aim was to have JIPs with all jurisdictions agreed by early December 2020.

2.9 Between 18 and 23 November 2020, Health held a series of bilateral meetings with each state and territory health authority to ‘design jurisdictional implementation plans that are aligned with the Vaccination Policy’. Topics discussed included:

- vaccination locations38, workforce and training requirements;

- vaccine transport, delivery and storage;

- monitoring and reporting on vaccine stock, and minimising wastage;

- coordinating safety monitoring and surveillance of adverse events; and

- communication.

2.10 ‘Early indicative drafts’ of the JIPs were sent to each state and territory health authority on 29 November 2020. The ANAO saw evidence of a lengthy consultative and redrafting process during December 2020 and January 2021, with several versions of JIPs being circulated. The JIPs were agreed by state and territory governments in February 2021.39

2.11 The JIPs repeated the respective responsibilities of the Australian, state and territory governments that had been stated in the vaccination policy (see paragraph 2.5). They also contained detailed information about the topics which had been discussed during the earlier bilateral meetings (see paragraph 2.9).

2.12 While some arrangements for the rollout could not be finalised until it was known which vaccines were available40, the statement in the August 2020 vaccine and treatment strategy that ‘Australian Government agencies are working with states and territories on transportation, storage and distribution plans’ was not accurate. More than two and a half months elapsed between the release of the vaccine and treatment strategy (on 18 August 2020) and the first meeting between Health and state and territory health authority CEOs on 6 November 2020 at which Health first put forward the ‘proposed responsibilities for States and Territories’.

Determining priority populations

2.13 Both the vaccine and treatment strategy and the vaccination policy stated that ‘the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI) is preparing advice to support planning for the allocation and use of safe and effective vaccines’.41

2.14 ATAGI issued two sets of advice ‘aimed at supporting planning by the Australian Government in the development of a strategy for the procurement of COVID-19 vaccines and program delivery’. The preliminary advice (summarised in Table 2.1) was provided to the Australian Government in August 2020 and recognised that ‘when vaccines are available, supplies will initially be limited and priority groups for vaccination will need to be identified’ and that ‘prioritisation should be based on evidence influenced by the prevailing epidemiology when specific vaccines become available’.42 Following further considerations of the progress of clinical trials and international approvals, the advice was finalised and publicly released on 13 November 2020.

Table 2.1: ATAGI preliminary advice on priority population groups

|

Risk factor |

Priority population |

|

Those who have an increased risk of developing severe disease or dying from COVID-19. |

Older people. |

|

People with pre-existing underlying select medical conditions. |

|

|

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. |

|

|

Those who are at increased risk of exposure and hence of being infected with and transmitting SARS-CoV-2 to others at risk of severe disease or are in a setting with high transmission potential. |

Health and aged care workers. |

|

Other care workers (such as group residential care and disability care workers). |

|

|

People in other settings where the risk of virus transmission is increased (such as correctional and detention facilities, sea and airports and meat processing plants). |

|

|

Those working in services critical to societal functioning. |

Select essential services personnel (such as public health personnel, police, emergency services and defence forces). |

|

Other key occupations required for societal functioning (such as workers in distribution of essential goods and services such as food, water, electricity, telecommunication and other critical infrastructure). |

Source: Department of Health, ATAGI – Preliminary advice on general principles to guide the prioritisation of target populations in a COVID-19 vaccination program in Australia [Internet], 13 November 2020.

2.15 On 24 December 2020, ATAGI provided the Australian Government with supplementary advice which added to its preliminary advice and more specifically identified which population groups should be accorded priority.43 Based on ATAGI’s advice, Health prepared Australia’s COVID-19 vaccine national roll-out strategy (the rollout strategy)44, which was released on 7 January 2021 and announced by the Prime Minister at a press conference on the same day.45 Table 2.2 shows the rollout phases, priority populations and the estimated number of people in each population.

Table 2.2: Rollout strategy: priority populations (as identified by Health)

|

Phase |

Priority population |

Number (est.) |

|

1a |

Quarantine and border workers |

70,000 |

|

Frontline healthcare worker subgroups for prioritisation |

100,000 |

|

|

Aged care and disability care staff |

318,000 |

|

|

Aged care and disability care residents |

190,000 |

|

|

Sub-total |

678,000 |

|

|

1b |

Elderly adults aged 80 years and over |

1,045,000 |

|

Elderly adults aged 70 to 79 years |

1,858,000 |

|

|

Other health care workers |

953,000 |

|

|

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people over 55 |

87,000 |

|

|

Younger adults with an underlying medical condition |

2,000,000 |

|

|

Critical and high risk workers including defence, police, fire, emergency services and meat processing |

196,000 |

|

|

Sub-total |

6,139,000 |

|

|

2a |

Adults aged 60 to 69 years |

2,650,000 |

|

Adults aged 50 to 59 years |

3,080,000 |

|

|

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 18 to 54 |

387,000 |

|

|

Other critical and high risk workers |

453,000 |

|

|

Sub-total |

6,570,000 |

|

|

2b |

Balance of adult population |

6,643,000 |

|

Sub-total |

6,643,000 |

|

|

3 |

Less than 18 (if recommended by ATAGI) |

5,670,000 |

|

Sub-total |

5,670,000 |

|

|

Total |

25,700,000 |

|

Source: Department of Health, Australia’s COVID-19 vaccine national roll-out strategy.

AstraZeneca recalibration

2.16 The initial stages of the rollout were heavily reliant on the AstraZeneca vaccine, with AstraZeneca comprising 80 per cent of the allocation of doses to sites over the first 12 weeks of the rollout.46

2.17 As discussed at paragraph 1.18, in early March 2021, reports began to circulate internationally about a rare but potentially serious side-effect47 of the AstraZeneca vaccine which appeared to be more prevalent in younger people. ATAGI monitored these reports and published several updates. On 8 April 2021, ATAGI updated its advice, recommending the use of Pfizer as the preferred vaccine for eligible people under 50.48

2.18 In April 2021, Australian governments considered options for the ‘recalibration’ of the vaccine strategy. Issues discussed included limited current supplies of Pfizer, changes to aged-based eligibility, the rollout to remote communities and increasing negative community sentiment towards AstraZeneca.49

2.19 On 22 April 2021, the Prime Minister announced that Australian governments had approved key changes to the COVID-19 vaccination rollout strategy.50 Seven of the key changes are listed in Table 2.3. Health implemented some changes, such as vaccine eligibility, in April 2021 and implemented other changes between May and August 2021.

Table 2.3: ANAO assessment of Health’s implementation of key changes under the recalibrated rollout strategy

|

Description of planned change |

Date implementedb |

Implementation complete |

|

Restricting the Pfizer vaccine to those under 50 years (with a few agreed exceptions).a |

22 April 2021 |

✔ |

|

Utilising the AstraZeneca doses by bringing forward eligibility for those over 50 years of age. |

4 May 2021 |

✔ |

|

Increasing access to Pfizer by:

|

17 May 2021 16 June 2021 |

✔ |

|

Providing more doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine to general practitioners (GPs) as demand permits through reallocation and re-directing doses within jurisdictions where it makes sense to do so. |

21 June 2021 |

✔ |

|

States and territories to continue to operate AstraZeneca sites where required, and open these sites up to those eligible in Phase 1a and 1b. |

24 May 2021 |

✔ |

|

Permitting state and territory operated vaccination sites to operate Pfizer and AstraZeneca services from the one site where practical. |

21 May 2021 |

✔ |

|

Encourage state and territories to incorporate community pharmacies into their rollout plans in rural and remote areas. |

11 August 2021 |

✔ |

Note a: ATAGI continued to monitor national and international safety data around AstraZeneca and on 17 June 2021 updated its advice to recommend the use of Pfizer as the preferred vaccine for eligible people under 60.

Note b: Date implemented is recorded as the date when the change was implemented in at least one jurisdiction or channel as relevant.

Source: ANAO analysis of Health documentation.

2.20 Health also acquired additional Pfizer doses to address the potential vaccine shortfall, consistent with the recalibrated rollout strategy. Between April 2021 and September 2021, Health ordered an additional 25.5 million Pfizer doses for delivery in 2021. These doses were delivered from mid-August with the majority to be available from September 2021.51

2.21 The change in ATAGI advice on AstraZeneca resulted in limited supply of vaccines preferred for people under 60 until September 2021.52 Health adapted the plan for the vaccine rollout and implemented these changes in a timely manner. This included encouraging the use of existing stocks of AstraZeneca while waiting for Pfizer suppply to increase from September 2021.

Sectoral vaccination program implementation plans

2.22 As noted in Table 2.2, people in residential aged care, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people over 55 years and people with disabilities were three of the priority groups for vaccination under Phases 1a and 1b. In addition, Health identified people from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities as a group which, while not identified by ATAGI as a priority population, might need greater assistance or support due to language and cultural issues.

2.23 Health developed specific vaccination program implementation plans for each of these groups in early 2021, which contained tailored sector-specific information as well as information about:

- Australian, state and territory government responsibilities (and other parties where relevant);

- workforce and training requirements;

- arrangements for safety monitoring and surveillance of adverse events53;

- minimising wastage, monitoring stock and reporting; and

- communication to people in the sector.

2.24 The plans for aged care, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and CALD communities were published on Health’s website in February and March 2021. The plan for people with disabilities was not published.54

Establishment of target dates in planning

2.25 The vaccine and treatment strategy and the vaccination policy (see paragraphs 2.4 and 2.5) did not contain any target dates or indication when the rollout would start or finish. At the time that these documents were published, it was not known when vaccines would become available. Jurisdictional Implementation Plans (see paragraphs 2.8 to 2.12) contained ‘indicative timelines’ for when the phases referred to in Table 2.2 would commence but not when they might be completed.

2.26 In late 2020 and early 2021, the Prime Minister, the Minister for Health and Aged Care and the Secretary of Health made a number of public statements and commitments about:

- when the rollout would commence;

- the date by which people could expect to be (or be given the opportunity to be) vaccinated; and

- when priority or vulnerable groups would be vaccinated.55

2.27 Health did not include target dates for the rollout as part of its planning prior to June 2021. In March 2021, the COVID-19 vaccination program was the subject of an Implementation Readiness Assessment (IRA)56 commissioned by the Department of Finance, which noted that achievement of the ‘policy commitment to complete the vaccination program by end October 2021’ was ‘highly unlikely’ and found:

the Program has adopted a just-in-time approach to planning, and has an acute focus on the next four weeks. The review team has seen only a high-level plan and no supporting detail for the medium term (until end October). Further, the vaccination deployment modelling beyond April is high level and incomplete. With the delivery of large quantities of vaccine by CSL (Seqirus) by end March, there is no justification for not having a model and delivery schedule for the entire program. The review team finds that the lack of this model and schedule is impeding preparations for future rollout, including by states and territories, that may require considerable lead times. The lack of a model and schedule for the medium term also means that it is not possible to have confidence in achievement of an end-October target.

2.28 The IRA’s recommendations included:

- Consider the use of intermediate objectives that demonstrate key public health outcomes prior to the October target. An example would be ‘all vulnerable Australian are protected’, as at the end of Phase 1a and 1b.

- Consider modifying the Program’s public objective to a more achievable version such as ‘all eligible Australians will be offered the vaccine and will have the opportunity to commence vaccination by end-October’.

- Develop a vaccination deployment model and associated plan for the next 8-12 months…

2.29 Health ‘noted’ these recommendations and its response was contained in an internal document which was not prepared until July 2021, after the establishment of Operation COVID Shield. The response to the recommendation on intermediate objectives read:

To support the recalibration following National Cabinet’s decision on April 16, the overarching narrative and guiding communications principles of the roll out have been revisited and the revised strategic approach supersedes the intent of this recommendation.

The revised approach includes focus groups for key cohorts, the exploration of partnerships to reach specific audiences and a refresh of the communications campaign. Vaccine Communications are also working closely with [the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet] to ensure the approach remains responsive to public sentiment. Key artefacts including Stakeholder Engagement and Communications Plan and External Communications Playbook have been revised.

2.30 Following the transition to Operation COVID Shield, lower-level targets were developed for some aspects of the rollout (see paragraph 2.37). Health’s reporting against these targets is discussed at paragraph 3.36 and achievement of targets is discussed in Chapter 4 and Appendix 4.

Rollout planning from June 2021 (Operation COVID Shield)

2.31 At a press conference on 4 June 2021, the Prime Minister announced the appointment of the Coordinator General of Operation COVID Shield, stating:

Lieutenant General Frewen will have direct operational control across numerous government departments for the direction of the national vaccination program and all of those working in that program, from communications to dealings with states, to the distribution and delivery of vaccines and all of these matters, and the ramp-up, the scale-up, the working with the GPs, pharmacists and others, this will all come under the direct control of Lieutenant General Frewen… I think that very direct command and control structure that has proved to be so effective in the past will add a further dimension and assistance as we step up in this next phase.57

2.32 The ANAO sought Health’s comments on the reasons for the move to a ‘command and control’ model and how that differed from the previous arrangements. Health said:

Operation COVID Shield used a command and control structure to coincide with an influx of new supply, and a need to increase the size and speed of the rollout. The command and control structure included direct operation control of all relevant assets and resources across all Commonwealth Government departments and agencies engaged in the direction and implementation of the national COVID vaccination program. [Operation COVID Shield] introduced a military led planning team and an assessment cell to support the command and control structure of the operation. The plans and assessment cells differ from traditional structures as they span all of the areas of the taskforce and aim to consolidate planning and tracking across all branches with a direct report to Coordinator General, as opposed to decentralised planning normally undertaken within the branches.

Operation COVID Shield campaign plan

2.33 On 3 August 2021, the Coordinator General released the Op COVID Shield National COVID Vaccine Campaign Plan (the campaign plan)58, which was stated to cover the period from 1 July 2021 to 31 December 2021. The plan described several challenges existing at that time, including:

- changed guidance from ATAGI in April 2021 (see paragraph 2.17) in relation to potentially dangerous side-effects associated with the AstraZeneca vaccine, which resulted in reduced confidence in the AstraZeneca vaccine and a surge in demand for the Pfizer vaccine;

- limited global supply of the Pfizer vaccine;

- delays in delivery to some priority groups due to global supply challenges, domestic supply shortfalls and ‘scale up’ challenges with vaccine administration service providers59; and

- changes made by states and territories to agreed vaccine eligibility criteria.

The campaign plan was divided into three stages (shown in Figure 2.1) which were based on anticipated vaccine supply and linked to and balanced with the progressive introduction of administration channels (discussed further at paragraph 4.8).

Figure 2.1: Operation COVID Shield campaign plan stages

Source: Operation COVID Shield campaign plan (Department of Health).

2.34 To assist vaccination providers (including those for which the states and territories were responsible) with their own planning, in June 2021, Health published ‘COVID Vaccination Allocations Horizons’ which showed the notional allocations for each state and territory by vaccine and channel for July to August 2021 (Horizon 1), September 2021 (Horizon 2) and October to December 2021 (Horizon 3). Later editions of the ‘Horizons’ were published in July and September 2021, with allocations updated based on modelling of future supply.

2.35 With regard to priority populations, the campaign plan stated that:

There are populations that have circumstances that require unique consideration to ensure equity of access and confidence in the vaccine rollout. To safeguard the health and wellbeing of the Australian population, it is critical that these priority groups have access to vaccines and are supported in receiving them.

2.36 The ten priority populations identified in the campaign plan are listed in Table 2.4.

Table 2.4: Operation COVID Shield campaign plan: priority populations

|

Priority populations |

|

|

Aged care |

Culturally and linguistically diverse communities |

|

Disability accommodation |

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people |

|

Regional, Rural and Remote rollout |

External territories |

|

Quarantine and border workers |

12-15-year olds |

|

Health care workers |

Other priority populationsa |

Note a: This includes people who are homeless, those in prison, those requiring drug and alcohol support, those in mental health facilities and social housing.

Source: Department of Health Operation COVID Shield campaign plan.

Sub-plans

2.37 To support the campaign plan, Health developed a series of sub-plans, including ‘acceleration plans’, which focused on specific priority groups and sectors. While the content of the sub-plans varied according to topic, they generally set out specific tasks and lower-level target dates for priority groups and sectors and were more consistent with the intention of the recommendation in the March 2021 Implementation Readiness Assessment (see paragraph 2.27). Examples of sub-plans are shown in Table 2.5.

Table 2.5: Examples of Operation COVID Shield sub-plans

|

Name |

Plan type |

Date approved |

Target set? |

|

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander acceleration plan |

Acceleration |

21/9/2021 |

80% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 12 or over receive at least one dose by 31/10/2021. |

|

Youth vaccination (12-18) |

Sub-plan |

21/9/2021 |

All youth are given opportunity to receive at least first dose by 20/12/2021. |

|

Pharmacy rollout |

Sub-plan |

21/9/2021 |

On-board suitable pharmacies for Moderna administration in six week period commencing September 2021. |

|

Residential disability in-reach |

Sub-plan |

21/9/2021 |

Two doses offered to residents of all 6,311 residential disability sites by 31/10/2021. |

|

NDIS participants and workers |

Acceleration |

15/10/2021 |

80% of NDIS participants 12 or over and workers fully vaccinated by 31/10/2021. |

|

Booster in-reach program for aged care and disability residents |

Sub-plan |

3/11/2021 |

Program to commence 8/11/2021. |

|

Regional and remote |

Sub-plan |

Not signed or dated |

Not seta |

Note a: The sub-plan did not set a specific target: it outlined ‘efforts to ensure that regional and remote communities are able to reach 70% and 80% fully vaccinated targets in line with the general population’.

Source: ANAO from Health documents.

Were risks to the rollout identified and regularly reassessed?

Risks to the rollout were identified from June 2020. In January 2021, Health established a comprehensive risks and issues register which was used throughout 2021 to identify risks to the rollout. Risks were kept under regular review and, where necessary, corrective action was determined. The most significant risks and issues were referred to the taskforce leadership for review.

2.38 Under the Public Governance Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), the accountable authority60 must establish and maintain appropriate systems of risk oversight, management, and internal control for the entity.61 The Commonwealth Risk Management Policy sets out the government’s risk management expectations for Australian Government entities in undertaking the business of government.62

2.39 There was early awareness that vaccination of the entire Australian population would be attended by many risks. For example, advice provided to government in June 2020 observed that the most significant risk was that there may never be a COVID-19 vaccine. As it became clear that a number of potentially effective vaccines would likely be available, internal documents show that Health started considering rollout risks in the latter part of 2020.

2.40 The August 2020 vaccine and treatment strategy committed the government to building a ‘diverse global portfolio of investments to seek to secure early access to promising vaccines and treatments, using local manufacturing wherever possible’. Two of the vaccines initially selected for purchase, the University of Queensland vaccine and AstraZeneca, were intended to be manufactured in Australia. At the time that advance purchase agreements for COVID-19 vaccines were signed, none of the selected vaccines had reached Phase 3 clinical trials and hence achieved TGA approval (see paragraph 1.8), which is a pre-requisite for use in Australia. In September 2020, an internal Health document identified a risk that ‘Domestic manufacture [is] not possible because negotiated candidate is not approved, further reducing dose volume’. This risk was subsequently realised (see case study 1).

|

Case study 1. Realisation of risks to domestic manufacture |

|

In October 2020, following Phase 1 clinical trials, the University of Queensland identified that its vaccine could produce false positive readings with certain HIV screening tests. Though there was no health risk, the potential for a false positive HIV result posed the risk that people may be deterred from being vaccinated.a Health sought the views of SITAG which agreed on 8 December 2020 that the University of Queensland vaccine should not continue to Phase 2/3 clinical trials. Consequently, the contract with the University of Queensland was terminated in December 2020. As a result, Health needed to address the potential shortfall of an anticipated 51 million doses for Australia’s vaccine portfolio. Health responded to the University of Queensland termination and on 10 December 2020, put to government a proposal to:

|

Note a: On 11 December 2020, the University of Queensland reported: ‘There is no possibility the vaccine causes infection, and routine follow up tests confirmed there is no HIV virus present. With advice from experts, CSL and UQ have worked through the implications that this issue presents to rolling out the vaccine into broad populations. It is generally agreed that significant changes would need to be made to well-established HIV testing procedures in the healthcare setting to accommodate rollout of this vaccine’.

Note b: AstraZeneca and Novavax had each indicated they could provide sufficient doses to cover the whole of the Australian population. The additional doses for both vaccines were announced on 11 December 2020. Negotiations for the additional doses of AstraZeneca and Novavax concluded on 24 December 2020, and 31 December 2020 respectively.

Risks and issues log

2.41 In December 2020, Health created a ‘risks and issues log’ which contained both a risk register and an issues log. With respect to risks, the log showed:

- the date that the risk was logged and who raised it;

- the risk owner and impacted workstream;

- the impacted stakeholder group63;

- the risk name, description and impact (if it were to occur);

- the current risk level (likelihood and consequence);

- the control assessment and treatment plan (if necessary); and

- the target risk rating.

2.42 The issues log was similarly detailed. Its purpose was to record what action had been taken with respect to identified risks.

2.43 One of the risks identified in the risks and issue log was that ‘uptake is below desired levels due to consumer sentiment’.64 This risk was also realised with the AstraZeneca vaccine (discussed at paragraphs 2.17 to 2.21).

2.44 The earliest version of the risks and issues log that the ANAO located (dated 15 January 2021) contained 79 risks. Some examples included:

- adverse event management — incomplete and inaccurate data;

- lack of suitably safe vaccine candidates;

- shortages of critical materials required for vaccinations;

- COVID-19 outbreak occurs impacting rollout; and

- immunisation workforce not sufficient, ready or appropriately skilled.

2.45 The latest version of the risks and issues log examined by the ANAO was dated 6 December 2021. It contained 301 risks, with risks added progressively throughout 2021.

2.46 Health instituted a process by which ‘top risks and issues’ were the subject of a ‘deep dive’ to assess the risk and consider whether any specific action was necessary. Risks rated ‘high’ or ‘extreme’ were then presented to a weekly meeting of the taskforce leadership group65, which reviewed the proposed corrective action and whether it was satisfied with the outcome. The ANAO reviewed examples of this process and found there was robust consideration of key rollout risks.

2.47 The consistent use of a risk register and a documented process to respond to risks as they arose demonstrates good practice.

Were administration channels and logistics considered and established?

Health worked with state and territory authorities and relevant stakeholders to consider and establish a variety of administration channels that were suitable for priority groups and the population as a whole. Two logistics providers were engaged to transport and deliver vaccines throughout Australia. Health underestimated the magnitude and complexity of rolling out in-reach services for the residential aged care and disability sectors and did not engage sufficient in-reach providers early in the rollout.

Administration channels

2.48 With more than 20 million people in Australia needing to be given at least two doses of vaccine66, it was clear from the outset that as many administration channels as possible would need to be used.67 The vaccination policy, published in November 2020, stated:

Vaccination sites will be agreed by the Australian Government and the States and Territories through their jurisdictional implementation plans. There are a number of likely vaccination locations. All vaccines must be administered in accordance with the relevant legislation, best practice, and the guidelines and recommendations the Australian Immunisation Handbook. Vaccination locations must facilitate the safety of vaccines, staff, and consumers; be adequately staffed with appropriately trained personnel; have the facilities and protocols in place to ensure data is reported in an accurate and timely way; and be able to manage high volumes of vaccinations.68

2.49 Other factors that influenced decisions about administration channels were:

- the difficulty some people (such as the elderly and people with disabilities) would have in attending a location such as a general practice;

- availability of vaccines;

- distribution capacity of logistics providers;

- the remoteness of some smaller areas of population; and

- the necessity to keep some vaccines ultra-cold at all times from manufacture until administration.

2.50 Under long-standing arrangements, responsibility for the administration and funding of health care facilities in Australia is shared between the Australian and state and territory governments. For example, while in 2017–18, the Australian Government provided 39 per cent of funding for public hospitals69, responsibility for their administration rests entirely with states and territories. Consequently, arrangements for establishing which locations would administer vaccines was one of the issues negotiated during the development of JIPs (see paragraph 2.9). Table 2.6 shows the administration channels that were used for the rollout and which government was responsible for the administration of vaccines for each.70

Table 2.6: Vaccine administration channels: responsible governments

|

Administration channel |

Government responsible |

Comment |

|

General practice |

Australian |

Registered medical practitioners providing medical care for individuals, families and communities. |

|

Commonwealth vaccination clinics (CVCs) |

Australian |

Originally established to assess and test people with respiratory symptoms. |

|

Aboriginal Controlled Community Health organisations (ACCHOs) |

Australian |

Funded by the Australian Government and operated by local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. |

|

Community pharmacies |

Australian |

Part of the community they serve (as distinct from consultant, hospital and industrial pharmacies). |

|

In-reach |

Australian |

Companies engaged to supply qualified providers to visit and administer vaccines on site. |

|

Hospital hubs |

State and territory |

Hubs established within, or on the campus of, hospitals. |

|

Mass vaccination hubs |

State and territory |

Fixed sites such as stadiums or conference centres. |

|

Community hubs |

Australian and state and territory |

Such as pop-up clinics in places of worship and mobile clinics for the homeless. |

|

Royal Flying Doctor Service (RFDS) |

Australian |

The RFDS was engaged under contract to distribute vaccines to selected rural and remote areas. |

Source: Health.

2.51 While some administration channels were established specifically to cater to particular priority groups71, people in those groups were not limited to only those administration channels. If they were able to, or preferred to, they could use another administration channels (such as their own general practitioner). Table 2.7 links the priority groups with the administration channels shown in Table 2.6. The introduction of administration channels was staged based on the priority populations they were targeting and Health’s modelling of expected vaccine supply. The implementation of administration channels is discussed in Chapter 4.

Table 2.7: Priority groups and administration channels

|

Population |

In-reacha |

Primary Care |

State and territory hubs |

Other |

|||

|

|

|

GP |

CVC |

ACCHO |

Pharmacy |

|

|

|

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people |

◇ |

◇ |

◇ |

◆ |

◇ |

◇ |

◇b |

|

Residential aged care facility (RACF) residents |

◆ |

◇ |

◇ |

◇ |

◇ |

◇ |

|

|

Residential disability facility residents |

◆ |

◇ |

◇ |

◇ |

◇ |

◇ |

|

|

RACF and residential disability workers |

◆ |

◇ |

◇ |

◇ |

◇ |

◆ |

◇c |

|

Non-residential people with a disability |

◇ |

◆ |

◆ |

◇ |

◆ |

◆ |

|

|

Non-residential older people |

|

◆ |

◆ |

◇ |

◆ |

◆ |

|

|

Frontline healthcare and border workers |

|

◇ |

◇ |

◇ |

◇ |

◆ |

|

|

People with pre-existing medical conditions |

|

◆ |

◆ |

◇ |

◆ |

◆ |

|

|

Regional and remote populations |

|

◆ |

◆ |

◇ |

◆ |

◆ |

◆b |

|

Remainder of population aged 12 or over |

|

◆ |

◆ |

◇ |

◆ |

◆ |

|

|

KEY: ◆ main administration channel/s for the population ◇ able to access vaccines through the administration channel |

|||||||

Note a: The majority of in-reach was performed by contracted Vaccine Administration Service providers (VAS providers). This is discussed further at paragraphs 4.12 and 4.13.

Note b: The Royal Flying Doctor Service delivered and administered vaccines in regional and remote communities, including to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

Note c: RACF and residential disability workers were eligible to access specific pop-up clinics.

Note: People can belong to multiple priority groups, for example an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander frontline healthcare worker. These people could access administration channels for both priority groups.

Source: ANAO analysis of Health records.

Operational planning for in-reach services

2.52 Most administration channels listed in Table 2.7 utilised existing infrastructure and processes, such as vaccines being administered by GPs. Health needed to establish new arrangements for in-reach services to the residential aged care and residential disability sectors, which required detailed operational planning.

2.53 Following an approach to market in December 2020, in late January 2021 Health engaged two Vaccine Administration Service (VAS) providers to conduct in-reach visits to residential aged care facilities. Health issued the first work orders under these contracts in early February 2021 and the providers began administering vaccines at residential aged care facilities when the rollout began on 22 February 2021. These work orders included detailed operational requirements, such as site requirements and RACF locations. Health engaged additional VAS providers later in the rollout when it identified the current arrangements were at high risk of not meeting its target dates for this area. The additional VAS providers were engaged under similar arrangements, as discussed in paragraphs 4.37 and 4.47.72

2.54 To plan the administration of vaccines to the residential disability sector, Health contracted a VAS provider (Aspen Medical) on 19 February 2021 to engage with key stakeholders and co-design the delivery model. This was provided to Health on 26 February 2021, and Health confirmed the model and approach for the rollout to the residential disability sector on 10 March 2021, more than one month later than for the residential aged care sector and after the rollout had commenced. On 1 April 2021, Health executed a work order with the same VAS provider used in the residential aged care rollout to provide in-reach services to the residential disability sector. Health engaged an additional VAS provider in May 2021, when existing arrangements proved to be insufficient. Health supplemented its arrangements for in-reach with operational policies and procedures, such as the excess dose policy.

2.55 The need to engage additional VAS providers later in the rollout indicates that Health underestimated the magnitude and complexity of the in-reach rollout to aged care and residential disability facilities. This issue is discussed further at paragraphs 4.35 and 4.47.

Logistics

2.56 In December 2020, Health entered into contracts with DHL and Linfox to co-design arrangements for the delivery of vaccines and ancillary consumables such as syringes throughout Australia. Logistical services contracts were signed with both providers in February 2021. Each provider was allocated responsibility for deliveries to particular geographical regions of states and territories. The providers were required to report to Health monthly on:

- cold chain compliance;

- data integrity;

- completeness and timeliness of deliveries;

- reporting and remediation of incidents; and

- lost, damaged or stolen vaccines and consumables.

2.57 Distribution and logistics services commenced in February 2021 for DHL and March 2021 for Linfox. Implementation of the logistics arrangements is discussed further at paragraphs 4.3 to 4.5.

Was a fit-for-purpose communication strategy for the COVID-19 vaccine rollout developed?

Health developed a fit-for-purpose strategy for communicating the vaccine rollout. The communication strategy and its supporting advertising strategy identified target audiences and was tailored to addressing the concerns of these groups as determined through market research. The advertising strategy complied with government guidelines for advertising campaigns and had a plan to monitor progress.