Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Administration of the JobKeeper Scheme

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- This audit was conducted under phase two of the ANAO’s multi-year strategy that focuses on the effective, efficient, economical and ethical delivery of the Australian Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- The JobKeeper scheme was a key measure in the Australian Government’s economic response to the COVID-19 pandemic and has affected a significant number of employees and businesses.

Key facts

- Over one million entities had JobKeeper applications processed by the ATO.

- Around $89 billion in JobKeeper payments were made.

- An average of 3.6 million individuals received payments in each month of the original scheme.

- 1160 ATO staff were involved in administering the scheme (as their primary role) in August 2020.

What did we find?

- The Australian Taxation Office’s (ATO’s) administration of the JobKeeper scheme was effective, except for shortcomings in implementation across parts of the ATO’s compliance program.

- The ATO has been effective in administering the legislative rules for the JobKeeper scheme.

- The ATO largely implemented fit for purpose arrangements to protect the integrity of JobKeeper payments.

- The ATO’s monitoring and reporting on the operational performance of the JobKeeper scheme was effective.

What did we recommend?

- No recommendations were made to the ATO or the Department of the Treasury.

- Key messages on the administration of economic response measures like the JobKeeper scheme have been identified for the benefit of Australian Government entities.

5 weeks

after the JobKeeper Payment was announced, entities could claim the first monthly reimbursement.

4 days

was the ATO’s average timeframe for processing a JobKeeper claim for reimbursement.

$180 million

in JobKeeper overpayments were waived by the ATO using the legislative discretion provided to the Commissioner of Taxation.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The JobKeeper Payment was announced by the Prime Minister and Treasurer on 30 March 2020 as part of the Australian Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The announcement stated that the JobKeeper Payment was a wage subsidy to businesses that would keep more Australians in jobs through the outbreak.

2. The legislative framework for the JobKeeper Payment mainly comprises:

- the Coronavirus Economic Response Package (Payments and Benefits) Act 2020 (CERP Act), which received Royal Assent on 9 April 2020; and

- the Coronavirus Economic Response Package (Payments and Benefits) Rules 2020 (‘the Rules’), which is a legislative instrument made under the CERP Act by the Treasurer.

3. The Rules establish the ‘JobKeeper scheme’ and set out the eligibility requirements for the JobKeeper Payment, payment arrangements and administration matters. The JobKeeper scheme is administered by the Commissioner of Taxation, who also has the general administration of the CERP Act.

4. The JobKeeper scheme was originally legislated to operate for six months from 30 March until 27 September 2020. Following an announcement by the Australian Government on 21 July 2020, the JobKeeper scheme was extended for six months to 28 March 2021.

5. The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) assisted the Commissioner of Taxation in the day-to-day administration of the JobKeeper scheme, while the Department of the Treasury (Treasury) has responsibility for JobKeeper policy and evaluation.

6. As with other COVID-19 economic response measures administered by the ATO in 2020, the JobKeeper scheme was characterised by rapid implementation.

7. As of 15 August 2021, the ATO’s data stated that net payments totalled $88.82 billion ($69.97 billion in the original period and $18.85 billion in the extension period). A total of 1,068,856 entities had applications processed under the scheme. An average of 3.6 million individuals were estimated to have received payments each month in the original period and 1.8 million unique individuals received payments in the extension period.

8. The ATO advised the ANAO that the cost of administering the JobKeeper scheme from March 2020 to 30 June 2021 was $286 million.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

9. An audit of the JobKeeper scheme is part of phase two of the ANAO’s multi-year strategy that focuses on the effective, efficient, economical and ethical delivery of the Australian Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

10. The JobKeeper scheme was a key measure in the Australian Government’s economic response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Following the phase one audit that examined the ATO’s management of risks related to the rapid implementation of six COVID-19 economic response measures (including the JobKeeper scheme)1, this audit focused on the ATO’s administration of the JobKeeper scheme. This audit also examined the ATO’s and Treasury’s strategies for evaluating the JobKeeper scheme and disseminating lessons learned.

Audit objective and criteria

11. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the ATO’s administration of the JobKeeper scheme.

12. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- Has the ATO effectively administered the legislative rules for the JobKeeper scheme?

- Has the ATO implemented fit for purpose arrangements to protect the integrity of JobKeeper payments?

- Has the ATO effectively monitored and reported on the operational performance of the scheme?

13. Under the third criterion, the scope of the audit included an examination of Treasury’s arrangements for evaluating the JobKeeper program and policy.

Conclusion

14. The ATO’s administration of the JobKeeper scheme was effective, except for shortcomings in implementation across parts of the ATO’s compliance program.

15. The ATO has been effective in administering the legislative rules for the JobKeeper scheme. The legislative rules relating to JobKeeper entitlement, payment rates and payment timeframes were reflected in the ATO’s administrative systems, processes and practices. The ATO’s approach was to make the application and payment process as simple and fast as possible for eligible entities.

16. In line with its priority of making timely payments to eligible entities, the ATO largely implemented fit for purpose arrangements to protect the integrity of JobKeeper payments. The ATO identified payment risks, developed compliance strategies and, with some exceptions, demonstrated that key compliance measures were implemented largely as intended. A more structured approach for documenting the reasons for exercising discretion on JobKeeper overpayments would have provided more transparency and accountability for the use of public funds.

17. The ATO’s monitoring and reporting on the operational performance of the JobKeeper scheme was effective. The ATO maintained fit for purpose governance arrangements to monitor scheme performance, regularly monitored performance and provided regular reporting to Treasury and other government entities. Treasury developed an evaluation framework for the JobKeeper program.

Supporting findings

Administering the legislative rules for the JobKeeper scheme

18. The ATO established processes to administer the legislative rules on entitlement that were aligned to its general self-assessment approach to administering the taxation and superannuation systems. Key rules on entitlement, including rule changes, were incorporated into the ATO’s processes. For the original period of the scheme, the ATO did not capture all relevant details in the JobKeeper application form about the decline in turnover test, impacting on its subsequent compliance activities. More granular information was added to the application form for the JobKeeper extension period. (See paragraphs 2.2 to 2.24)

19. The ATO’s systems and processes were appropriately updated when JobKeeper payment rates changed. Payment amounts were calculated correctly by the ATO, taking into account the number of employees declared by the applicant and the relevant JobKeeper payment rate at different periods of the scheme. (See paragraphs 2.25 to 2.28)

20. Ninety-nine per cent of JobKeeper payments were made to entities within the initial 14-day timeframe set out in the Rules. The average timeframe was four days. (See paragraphs 2.29 to 2.34)

Protecting the integrity of JobKeeper payments

21. Compliance strategies were developed for both periods of the scheme. Detailed treatment plans set out the ATO’s intended compliance measures for specific payment risks. (See paragraphs 3.3 to 3.17)

22. The ATO did not implement all key compliance and integrity measures as intended. Of the 22 compliance measures tested, two were partly implemented as intended, seven largely as intended and eight fully as intended. The ANAO was unable to conclude on five compliance measures due to data integrity issues. The ATO’s governance and internal reporting arrangements did not provide clear assurance on the implementation of the compliance measures. (See paragraphs 3.18 to 3.28)

23. While the ATO conducted decline in turnover reviews in accordance with its internal procedures, the nature of the ATO’s procedures and variability in the documentation maintained did not provide strong assurance on the assessed eligibility of entities that were reviewed. (See paragraphs 3.29 to 3.43)

24. The ATO exercised discretion on overpayments largely in accordance with its internal policies and procedures. The ATO’s approach was that the exercise of discretion needed to be reasonable based upon the circumstances of the case. The ATO’s guidance material set out two significant factors to be taken into account when exercising discretion — honest mistake and retention of financial benefit. Based on a sample of 63 overpayments, the ATO did not consistently document how its exercise of discretion related to the two significant factors. The ATO’s understanding of the law was that the Commissioner’s discretion on JobKeeper overpayments could not be limited by internal policies and procedures. (See paragraphs 3.44 to 3.60)

Monitoring and reporting on the performance of the JobKeeper scheme

25. The ATO implemented sound arrangements for monitoring the performance of the JobKeeper scheme. Governance arrangements were established early and were subject to review and adjustments. The main governance and oversight bodies operated in accordance with their charters in respect of meeting frequency and matters considered. The ATO monitored and reported on performance. Internal performance measures were reported in July 2021. (See paragraphs 4.3 to 4.23)

26. The ATO has reported externally on the JobKeeper scheme in a timely and informative manner, in line with arrangements established for the scheme and with public sector mechanisms. (See paragraphs 4.24 to 4.40)

27. Treasury has established arrangements to evaluate the JobKeeper Payment. An evaluation report is scheduled to be completed by the end of 2022. In December 2021, Treasury’s Executive Board determined that the JobKeeper evaluation would be conducted internally. The ATO has internally reviewed its administration of the scheme. (See paragraphs 4.41 to 4.57)

Summary of entity responses

28. The entities’ summary responses to the audit are set out below, while their full responses are provided at Appendix 1.

Australian Taxation Office

The ATO welcomes this review and the report finding that the ATO has been effective in administering the legislative rules for the JobKeeper scheme and effective in our administration, noting some areas for improvement. We are also pleased the ATO’s arrangements for administering the program were found to be fit for purpose considering the context and timeframe that it was asked to be delivered within.

The ATO identified payment risks, developed compliance strategies and, with some exceptions, demonstrated that key compliance measures were implemented largely as intended. We recognise the findings identified the potential for better record-keeping practices, particularly in relation to the favourable exercise of discretions and decisions not to continue compliance action, although we do note the actual environment required rapid implementation while balancing the need to support the community in a time of great uncertainty. We note also that the ATO, under a self-assessment system and having regard to the efficient use of resources, has traditionally put more effort into documenting reasons for decisions unfavourable to taxpayers (to ensure rigour in the decision and to provide procedural fairness to a taxpayer who may wish to challenge that decision) than to favourable decisions (which are unlikely to be challenged).

We reaffirm the challenge of delivering a program of the scale and complexity of JobKeeper under exceptional circumstances and in very tight timeframes and reflect the confidence and pride that the ATO has, that the substantive outcomes of this program have been delivered with high integrity. Whilst there are some differences of opinion, the ATO has taken on board the findings from the ANAO and will continue to refine and improve processes in the delivery of our key programs of work.

Department of the Treasury

Treasury welcomes the report and its finding that the Australian Taxation Office’s administration of the JobKeeper scheme has been largely effective. Given the potential for a severe economic outcome to materialise, JobKeeper had to be implemented rapidly to ensure support was delivered to households and businesses to address the acute circumstances of the time.

While the report does not contain any recommendations for Treasury, the findings and key messages within the report are valuable in the context of Treasury’s role in providing economic policy advice, including designing economic stimulus measures in the future.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Governance and risk management

Performance and impact measurement

1. Background

Overview of the JobKeeper Payment and scheme

1.1 The JobKeeper Payment was announced by the Prime Minister and Treasurer on 30 March 2020 as part of the Australian Government’s response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

1.2 The announcement stated that the JobKeeper Payment was a wage subsidy to businesses that would keep more Australians in jobs through the outbreak. The announcement outlined that:

- the payment would be made to employers for up to six months for each eligible employee who was on the employer’s books on 1 March 2020 and was retained or continued to be engaged by that employer;

- employers would receive a payment of $1500 per fortnight per eligible employee2 and every eligible employee must receive at least $1500 per fortnight from this business, before tax;

- eligible employers included businesses structured through companies, partnerships, trusts and sole traders, and not-for-profit entities, including charities; and

- the program would commence on 30 March 2020, with the first payments to be received by eligible businesses in the first week of May as monthly arrears from the Australian Taxation Office (ATO).

1.3 Other countries also introduced wage subsidy or ‘job retention’ schemes in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, including the United Kingdom, New Zealand and Canada.3

Legislative framework

1.4 The legislative framework for the JobKeeper Payment mainly comprises:

- the Coronavirus Economic Response Package (Payments and Benefits) Act 2020 (CERP Act), which received Royal Assent on 9 April 2020; and

- the Coronavirus Economic Response Package (Payments and Benefits) Rules 2020 (‘the Rules’), which is a legislative instrument made under the CERP Act by the Treasurer.4

1.5 The Rules were first made by the Treasurer on 9 April 2020 and were updated a number of times during the course of the JobKeeper scheme.

1.6 The Rules establish the ‘JobKeeper scheme’ and set out the eligibility requirements for the JobKeeper Payment, payment arrangements and administration matters. The JobKeeper scheme is administered by the Commissioner of Taxation, who also has the general administration of the CERP Act.

1.7 The JobKeeper scheme was originally legislated to operate from 30 March to 27 September 2020. Following an announcement by the Australian Government on 21 July 2020, the JobKeeper scheme was extended to 28 March 2021. Under the Rules, the Commissioner of Taxation must not make any JobKeeper payments after 31 March 2022, except in specified circumstances.5

Rapid implementation

1.8 As with other COVID-19 economic response measures administered by the ATO in 2020, the JobKeeper scheme was characterised by rapid implementation. The first monthly claim period under the scheme opened on 4 May 2020, five weeks after the JobKeeper Payment was announced.

1.9 In his opening statement to the Parliament of Australia’s Senate Select Committee on COVID-19 on 7 May 2020, the Commissioner of Taxation articulated the ATO’s approach to administering the economic response measures, including JobKeeper, as follows:

In response to COVID-19, the ATO has pivoted our focus to ensure the efficient rollout of the five key measures, in particular the JobKeeper payments, early release of superannuation, cash flow boost, increasing the instant asset write-off, and accelerated depreciation. Our priority has been to deliver on the government’s commitment to get millions of Australians access to financial support quickly and as easily as possible during this difficult time.6

JobKeeper Payment

1.10 As of 15 August 2021, ATO data indicated that net payments7 totalled $88.82 billion ($69.97 billion in the original period and $18.85 billion in the extension period). A total of 1,068,856 entities had applications processed under the scheme.8 An average of 3.6 million individuals were estimated to have received payments each month in the original period9 and 1.8 million unique individuals received payments in the extension period.10 A monthly breakdown of net payments, the number of entities receiving payments and the number of individuals covered by payments over the course of the scheme is provided in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Net payments, entities with processed applications, individuals with processed applications — 30 March 2020 to 28 March 2021

Notes: The first ‘JobKeeper fortnight’ was 30 March to 12 April 2020.

The August and December 2020 net payments are higher due to three JobKeeper fortnights being included in these periods.

Source: ANAO, reproduced from the ATO’s JobKeeper data (as at 15 August 2021).

1.11 Other summary data produced by the ATO on the JobKeeper scheme, including analysis by entity type, market segment and jurisdiction, is provided at Appendix 3.

Administration arrangements for the JobKeeper scheme

1.12 The ATO assisted the Commissioner of Taxation in the day-to-day administration of the JobKeeper scheme, while Treasury has responsibility for JobKeeper policy and evaluation.

1.13 The ATO’s administration arrangements for the JobKeeper scheme changed over time.

- For the first six months, compliance activities were undertaken by four business lines within the ATO’s Client Engagement Group. ATO documentation noted that this reflected the rapid implementation and the ATO’s ability to leverage its existing structures and processes.

- In October 2020, the ATO established the Economic Stimulus Branch within the Client Engagement Group to centralise administration of the JobKeeper scheme (as well as the JobMaker Hiring Credit scheme and the Single Touch Payroll program). The Economic Stimulus Branch comprised three work streams: Engagement and Assurance (initially 556 staff), Advice and Guidance (212), and Program Governance and Management (74, of which 12 worked on JobKeeper and 62 on the Single Touch Payroll program).

- The Economic Stimulus Branch was disbanded in June 2021 and responsibility for JobKeeper functions, including compliance work, was assigned to the Superannuation and Employer Obligations business line.

1.14 The cost of administering the first six months of the JobKeeper scheme was funded from the ATO’s existing budget in 2019–20. The ATO received additional funding of $305.9 million over four years in the 2020–21 Budget to deliver the extension period and the JobMaker Hiring Credit scheme. The bulk of this funding ($256.2 million) was allocated for 2020–21.

1.15 The ATO advised the ANAO that the cost of administering the JobKeeper scheme from March 2020 to 30 June 2021 was $286 million. Figure 1.2 shows the number of ATO staff involved in administering the JobKeeper scheme (as their primary role) from May 202011 to June 2021.

Figure 1.2: Number of ATO staff administering the JobKeeper scheme, May 2020 to June 2021

Note: Staff worked in Client Engagement Group, Enterprise Solutions and Technology, and Law Design and Practice.

Source: ANAO, based on the ATO’s data.

1.16 Treasury’s responsibilities for JobKeeper policy were managed by the JobKeeper Division, which was later renamed the Labour Market Policy Division, located within Fiscal Group. An average of 22 staff worked in the division between April 2020 and June 2021. Staff also had responsibilities for the JobMaker Hiring Credit scheme and other labour market policy matters. The Tax Analysis Division within Treasury’s Revenue Group also had dealings with the ATO on fiscal and economic updates and reporting.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.17 An audit of the JobKeeper scheme is part of phase two of the ANAO’s multi-year strategy that focuses on the effective, efficient, economical and ethical delivery of the Australian Government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.12

1.18 The JobKeeper scheme was a key measure in the Australian Government’s economic response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Following the phase one audit that examined the ATO’s management of risks related to the rapid implementation of six COVID-19 economic response measures (including the JobKeeper scheme)13, this audit focused on the ATO’s administration of the JobKeeper scheme. This audit also examined the ATO’s and Treasury’s strategies for evaluating the JobKeeper scheme and disseminating lessons learned.14

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.19 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the ATO’s administration of the JobKeeper scheme.

1.20 To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the following high-level criteria were adopted:

- Has the ATO effectively administered the legislative rules for the JobKeeper scheme?

- Has the ATO implemented fit for purpose arrangements to protect the integrity of JobKeeper payments?

- Has the ATO effectively monitored and reported on the operational performance of the scheme?

1.21 Under the third criterion, the scope of the audit included an examination of Treasury’s arrangements for evaluating the JobKeeper program and policy.

Audit methodology

1.22 The audit methodology included:

- examination of ATO documentation;

- analysis of JobKeeper data to assess timeliness of JobKeeper payments and correct payment rates;

- examination of Treasury documentation relating to the evaluation of the JobKeeper program and policy; and

- meetings with ATO and Treasury staff.

1.23 The audit considered feedback from members of the National Tax Liaison Group15 on aspects of the ATO’s administration of the JobKeeper scheme, and six submissions received through the citizen contribution function on the ANAO website.

1.24 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of $963,033.

1.25 The team members for this audit were David Willis, Samuel Painting, Evan Lee, Connor McGlynn, Chay Kulatunge, Matt Rigter, Omer Shaikh, Peta Martyn and Christine Chalmers.

2. Administering the legislative rules for the JobKeeper scheme

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) has effectively administered the legislative rules for the JobKeeper scheme.

Conclusion

The ATO has been effective in administering the legislative rules for the JobKeeper scheme. The legislative rules relating to JobKeeper entitlement, payment rates and payment timeframes were reflected in the ATO’s administrative systems, processes and practices. The ATO’s approach was to make the application and payment process as simple and fast as possible for eligible entities.

2.1 To assess the effectiveness of the ATO’s administration of the legislative rules governing the JobKeeper scheme, this chapter examines whether the ATO:

- established effective processes to administer the legislative rules on entitlement, including changes to those rules during the course of the scheme;

- appropriately updated systems and processes when JobKeeper payment rates changed; and

- made JobKeeper payments in accordance with the timeframes set out in the legislative rules.

Did the ATO establish effective processes to administer the legislative rules on entitlement?

The ATO established processes to administer the legislative rules on entitlement that were aligned to its general self-assessment approach to administering the taxation and superannuation systems. Key rules on entitlement, including rule changes, were incorporated into the ATO’s processes. For the original period of the scheme, the ATO did not capture all relevant details in the JobKeeper application form about the decline in turnover test, impacting on its subsequent compliance activities. More granular information was added to the application form for the JobKeeper extension period.

2.2 The ANAO examined whether the ATO established effective administrative design and decision-making processes to give effect to the rules on entitlement determined by the Treasurer. The legislative rules on entitlement for a JobKeeper payment are set out in part 2 of the Rules and are specified under three headings:

- Entitlement based on paid employees — an employer’s entitlement for an employee;

- Entitlement based on business participation — a business’ entitlement for an individual who is not an employee but is actively engaged in operating the business16; and

- Entitlement based on paid religious practitioners — a registered religious institution’s17 entitlement for a minister of religion or a full-time member of a religious order.

2.3 Part 2 of the Rules also lists the types of entities that do not qualify for the JobKeeper scheme.18 These include Australian government agencies and local governing bodies.19

Self-assessment approach and administrative design

2.4 The ATO administered the JobKeeper scheme, including the legislative rules on entitlement, on a self-assessment basis — in line with its approach to administering other parts of the taxation and superannuation systems.

2.5 The main features of the ATO’s self-assessment approach for the JobKeeper scheme were:

- applicants (or their intermediaries20) were responsible for assessing their eligibility to receive JobKeeper payments by answering questions on forms developed by the ATO (with questions tailored based on information already held by the ATO);

- the ATO provided information and guidance in its forms, on its website and in direct stakeholder communication to support applicants to provide the correct information;

- applicants were not required to provide evidence upfront to support their self-assessment — they were required to declare that the information provided was true and correct; and

- the ATO undertook pre-payment and post-payment checks and compliance activities to support the integrity of the application and payment processes for the scheme — these included processes to ‘block’ entities that were ineligible under the Rules.

2.6 The decision-making process that led to the ATO administering the JobKeeper scheme on a self-assessment basis was not evident from the ATO’s records. Treasury advised the ANAO that the decision to adopt self-assessment was implicit in the original policy decision made by government that the ATO would be the key delivery entity leveraging its existing mechanisms.

2.7 The ATO’s early planning arrangements included establishing a ‘core design team’ to develop the legislation, processes and data management. The core design team was chaired by an Assistant Commissioner and was comprised of representatives from different program ‘streams’ such as compliance, marketing and communications, advice and guidance, internal readiness, IT and data, and rapid dispute resolution. The core design team was focused on the ATO’s readiness for JobKeeper applications to be made and the development of ‘experience pathways’ for applicants.21

2.8 An internal briefing pack, which the ATO advised incorporated the JobKeeper measure on 9 April 2020, indicated that the following key design decisions had been made by this date.

- Eligible employers to apply online, self-assess eligibility through a reduction in turnover and identify eligible employees.

- Employees to complete an approved nomination notice that is kept by the employer.

- Single Touch Payroll (STP) employers to have some prefilled employee data.22

- Non-STP employers and the self-employed to have a more manual claim process.

2.9 The JobKeeper Program Board — the ATO’s key governance body for the scheme — held its first meeting on 14 April 202023, with the focus on the ATO’s ‘Day 1 Readiness Program’. A paper on ‘experience pathways’ for different JobKeeper parties (employers, intermediaries, employees) across the initial phases of the scheme was considered (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1: JobKeeper experience pathway, as of 14 April 2020

Note: Generic for all employees excluding non-digital.

Source: Reproduced from the ATO’s records.

2.10 The ATO’s intended approach was to focus on online forms and to use its existing online service channels as the main mechanism for accessing the scheme. Applicants would apply through one of three channels: ATO Online24; Business Portal25; or Online Services for Agents.26 ATO documentation shows that 87.6 per cent of applications were made through the three online channels.27

2.11 The paper considered by the JobKeeper Program Board on 14 April 2020 set out a number of principles for administering the JobKeeper scheme. This included the intention for payments to be made ‘as timely and seamlessly as possible.’ A 28 April 2020 paper set out the guiding principles for compliance, including that the ATO sought to make it easy for JobKeeper payments to be made to eligible applicants, and stated that strategies to detect suspected ineligible applicants would be developed.

2.12 The ATO continued to consider design issues over the course of the scheme. A JobKeeper Design Board was established in July 2020 following the announced extension of the scheme.28 The Design Board was renamed the Economic Stimulus Design Board in September 2020. At its 5 August 2020 meeting, the Design Board decided to maintain the existing administrative arrangements for the JobKeeper extension period.

Administering the decline in turnover tests

2.13 The decline in turnover test was a key eligibility requirement for the JobKeeper scheme (Appendix 4). The Rules provided for four types of decline in turnover tests:

- a basic test — met by having projected, or experienced, a threshold reduction in turnover, which varied by entity type;

- an alternative test — met by satisfying one of eight alternative tests determined by legislative instrument29;

- a modified test for certain group structures — met by having projected, or experienced, a specified reduction in turnover, when the turnover of each member of a consolidated, consolidatable or GST group is combined; and

- an actual decline in turnover test — introduced in the JobKeeper extension period and met by having experienced the threshold reduction in turnover, which varied by entity type.

2.14 JobKeeper applicants were required to satisfy the relevant test, along with other requirements30, in order to be eligible for a JobKeeper payment.

Online application form

2.15 The online application form developed by the ATO for the original period of the scheme required applicants to determine the relevant turnover threshold and declare whether they had experienced, or were likely to experience, that reduction for a nominated month (Appendix 5). Questions were tailored for the applicant based on the information previously provided to the ATO.

2.16 The form did not require the applicant to specify:

- which relevant decline in turnover test they used in self-assessing their eligibility;

- whether the ‘turnover test period’ was for a month or quarter as provided for in the Rules and the Explanatory Statement to the Rules, instead asking applicants to nominate a month only;

- whether the claimed reduction in revenue was informed by a projection or on the basis of actual revenue data — as was considered to be an important distinguishing factor in the ATO’s subsequent compliance activities on the scheme31; or

- whether a cash or accrual accounting method was used in calculating their decline in turnover — the two options provided for in the ATO’s ‘administratively binding’ Law Companion Ruling on its approach to administering the decline in turnover test.

2.17 The ATO advised the ANAO that the forms for the original period of the scheme did not ask applicants which test they used to satisfy the decline in turnover test because of the speed in which the ATO had to implement the application process for the JobKeeper scheme.

2.18 An internal ‘Strategy finalisation report’ dated 23 October 2020 noted that in relation to the risk population of ‘self-preparers’ and ‘agents and intermediaries’:

not capturing the basic or alternative test information on the application form made it difficult to correctly determine the risk. In many instances the Agent had used actual turnover figures to determine eligibility … Many clients had also appropriately used the alternative test.

2.19 This same document also noted that not asking applicants to specify whether the cash or accrual method was used limited the use of Business Activity Statement data as a reliable indicator of whether the decline had eventuated.

2.20 The JobKeeper Design Board considered the question of whether the ATO should capture additional information in the JobKeeper extension period to assist in assurance over eligibility. A paper considered at the 14 August 2020 meeting recommended that the JobKeeper extension form capture details on the alternative decline in turnover tests. The ATO revised its online application form for the extension period to capture these details (Appendix 5).

Reflecting other rule changes in administrative processes

2.21 In addition to the actual decline in turnover test introduced for the JobKeeper extension period, other changes to the rules on entitlement were made over the course of the JobKeeper scheme. The ATO reflected these other rule changes in its online application forms, associated guidance and employee nomination notices (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1: Other rule changes reflected in the ATO’s administrative processes for JobKeeper

|

Date of change |

Rule change |

Rationale |

Reflected in ATO processes? |

|

1 May 2020 |

Established an additional entitlement category for JobKeeper — registered religious institutions based on paid religious practitioners. |

The change was made ‘to assist entities to maintain relationships with their religious practitioners throughout the period of the downturn.’a |

Yes — the ATO reflected the rule change in the nomination notice for religious practitioners and in guidance provided through the online forms for JobKeeper. |

|

15 August 2020 |

Allowed employers to use 1 July 2020 (previously 1 March 2020) as the date an employee could qualify for JobKeeper. |

The change was made so ‘that eligible entities can qualify for JobKeeper payments in respect of more recently engaged employees or existing employees that now meet eligibility requirements.’b |

Yes — the ATO reflected the rule change in an updated employee nomination notice that required new employees to declare to their employer that they satisfied the new entitlement requirements to participate in the JobKeeper scheme. |

|

16 September 2020 |

Modified the amount of the JobKeeper payment based on the number of hours worked by each individual, to be stepped down in the December 2020 and March 2021 quarters. |

The introduction of the two-tiered payment rate and the gradual step down of assistance was to ‘ensure that the rate of the payment is appropriately targeted and sustainable.’c |

Yes — the ATO reflected the rule change by adding drop down lists to the online form for the JobKeeper extension period that required the applicant to identify whether the higher or lower payment rate applied for each individual. |

Note a: Explanatory Statement, Coronavirus Economic Response Package (Payments and Benefits) Amendment Rules (No. 2) 2020 (Cth), p.22.

Note b: Explanatory Statement, Amendment Rules (No. 7) 2020 (Cth), p.3.

Note c: Explanatory Statement, Amendment Rules (No. 8) 2020 (Cth), p.4.

Source: ANAO, based on the ATO’s records and public records.

Processes to block ineligible entities

2.22 The ATO’s general approach to block ineligible entities involved the compilation of an Australian Business Number (ABN) ‘exclusion list’ and the use of system-based exclusion rules to prevent ineligible entities from accessing the ATO’s online enrolment form and claiming a JobKeeper payment. The exclusion list drawn from ATO-held information was developed in April 2020 and included entities that do not qualify for the JobKeeper scheme listed in part 2 of the Rules, including entities who registered for an ABN after 12 March 2020.32

2.23 The ATO identified that it was not able to effectively develop a population of all the exceptions provided for in subsection 7(2) of the Rules. Wholly-owned government bodies (as per paragraph 7(2)(d) of the Rules) had not been excluded because of difficulties in precisely identifying these entities from the source data available. Also, the ATO identified that its population of exclusions would be restricted to those entities that meet a tight definition of liquidation and bankruptcy.

2.24 The ATO reported in a compliance update to the Treasurer on 7 July 2021 that 69,500 ineligible JobKeeper enrolment attempts had been prevented. The ATO advised the ANAO that it did not maintain a report on the types of excluded entities that made up the total 69,500 enrolment attempts or which entities triggered the ‘blocks’ set up through its system access rules.

Have the ATO’s systems and processes been appropriately updated when payment rates have changed?

The ATO’s systems and processes were appropriately updated when JobKeeper payment rates changed. Payment amounts were calculated correctly by the ATO, taking into account the number of employees declared by the applicant and the relevant JobKeeper payment rate at different periods of the scheme.

2.25 Section 13 of the Rules sets out the amount of the JobKeeper fortnightly payment.

- For the original period of the scheme, the payment rate was $1500 per fortnight for each eligible individual. The Explanatory Statement to the Rules noted that the $1500 payment provided the equivalent of approximately 70 per cent of the national median wage. Treasury’s three-month review of the JobKeeper Payment noted that the $1500 JobKeeper rate provided an ‘income transfer payment’ to some individuals.33 That is, the $1500 rate was higher than some individuals’ ordinary wages.34

- For the extension period, the JobKeeper payment rate was ‘stepped down’ in two stages and two payment ‘tiers’ were introduced — a higher rate and a lower rate (Table 2.2).

Table 2.2: JobKeeper payment rates, 28 September 2020 to 28 March 2021

|

Period |

Tier 1 rate |

Tier 2 rate |

|

28 September 2020 to 3 January 2021 |

$1200 |

$750 |

|

4 January 2021 to 28 March 2021 |

$1000 |

$650 |

Source: ANAO, based on section 13 of the Coronavirus Economic Response Package (Payments and Benefits) Rules 2020 (Cth).

2.26 Entitlement to the Tier 1 rate generally depended on whether an individual satisfied the relevant 80-hour threshold over the specified ‘reference period’35; otherwise, the Tier 2 rate applied. The Australian Government’s announcement of the JobKeeper extension noted that the two-tiered payment system was designed to better align the payment with the incomes of employees before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.27 The ANAO tested a population of more than 8.8 million JobKeeper transactions36 to determine whether the ATO’s payment systems and processes used the correct payment rates for different periods of the JobKeeper scheme.37 The transactions covered the period from 3 May 2020 to 28 February 2021, and involved net JobKeeper payments and receipts of over $84.4 billion. Of this total, $72.1 billion in transactions were system-automated without any manual intervention by ATO staff. The balance of the transactions, $12.3 billion (15 per cent), involved manual intervention. Manual interventions could include entering the complete transaction as the result of a telephone call, reversing or amending a transaction as a result of compliance procedures or amending a transaction at the request of the entity.

2.28 The ANAO tested the transaction amount through a combination of automated evaluation and sample testing.38 The testing took account of the relevant claim period and rate, the number of employees, and employees’ respective payment rates as reported by entities in monthly JobKeeper claims. Thirteen per cent of the 8.8 million transactions were updating non-financial data and had no financial effect. The remaining 7.7 million transactions were found to be materially correct.39

Were JobKeeper payments made in accordance with required timeframes?

Ninety-nine per cent of JobKeeper payments were made to entities within the initial 14-day timeframe set out in the Rules. The average timeframe was four days.

2.29 Section 15 of the Rules sets out the timeframe in which the Commissioner of Taxation (‘the Commissioner’) must pay JobKeeper payments.

The Commissioner must pay the jobkeeper payment no later than the later of:

(a) 14 days after the end of the calendar month in which the fortnight ends; and

(b) 14 days after the requirements in section 14 for the Commissioner to make the payment are met.40

2.30 In relation to section 14 of the Rules, the Explanatory Statement notes that if the Commissioner is satisfied that an employer or business is entitled to a JobKeeper payment for a fortnight, the Commissioner must pay the employer or business the JobKeeper payment. The ATO advised the ANAO that the practical application of section 14 is that when an entity lodged its monthly JobKeeper declaration, the Commissioner could choose to accept the statements and be satisfied on the basis of those statements to make the payment to the entity. Alternatively, the Commissioner may not be satisfied and could undertake checks before making a payment. The ATO further advised that the Rules did not prescribe when the Commissioner must become satisfied. That is, the Rules did not set a time limit on how long the ATO could take to determine whether an entity was entitled to a JobKeeper payment.

2.31 Automated testing of 7,329,699 JobKeeper payment transactions for 3 May 2020 to 28 February 2021 was performed by the ANAO to identify the number of payment transactions that were disbursed by the ATO within 14 days of a JobKeeper application form being received by the ATO.41 A total of 7,265,348 payment transactions (99 per cent) were paid within 14 days (Figure 2.2). The balance of the tested population (64,351 payment transactions) were paid after 14 days. The average timeframe for making a JobKeeper payment was four days.

Figure 2.2: Distribution of JobKeeper payments made within 14 days

Source: ANAO, based on the ATO’s data.

2.32 The ATO’s goal was to make timely payments whilst also checking the integrity of payments. A 27 April 2020 paper considered by the ATO recommended a four-day rather than three-day payment cycle, allowing the ATO an additional day to run ‘risk rules’ and undertake fraud checks.

2.33 In relation to the number of payments processed within two days, the ATO advised the ANAO that risk cases were still able to be identified and removed prior to any payment file being generated.

2.34 The ANAO analysed the time distribution of the 64,351 payments made after 14 days, nearly half of which were paid within 24 days (Figure 2.3). The longest timeframe for disbursement of a JobKeeper payment was 306 days.

Figure 2.3: Distribution of JobKeeper payments made after 14 days

Source: ANAO, based on the ATO’s data.

3. Protecting the integrity of JobKeeper payments

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) implemented fit for purpose arrangements to protect the integrity of JobKeeper payments.

Conclusion

In line with its priority of making timely payments to eligible entities, the ATO largely implemented fit for purpose arrangements to protect the integrity of JobKeeper payments. The ATO identified payment risks, developed compliance strategies and, with some exceptions, demonstrated that key compliance measures were implemented largely as intended. A more structured approach for documenting the reasons for exercising discretion on JobKeeper overpayments would have provided more transparency and accountability for the use of public funds.

3.1 In administering the legislative rules for the scheme, the Commissioner of Taxation (the Commissioner) and the ATO had responsibility, and broad discretion, for determining and implementing measures to protect the integrity of JobKeeper payments.42

3.2 To assess whether the ATO implemented fit for purpose arrangements for protecting the integrity of JobKeeper payments, this chapter examines whether the ATO:

- developed a compliance framework and strategy for the JobKeeper scheme;

- implemented key compliance and integrity measures as intended;

- conducted ‘decline in turnover’ reviews in accordance with its internal procedures; and

- exercised discretion on overpayments in accordance with its internal policies and procedures.

Did the ATO develop a compliance framework and strategy for the JobKeeper scheme?

Compliance strategies were developed for both periods of the scheme. Detailed treatment plans set out the ATO’s intended compliance measures for specific payment risks.

3.3 The expectation that the ATO develop a compliance framework and strategy for the JobKeeper scheme is based on the materiality of the scheme and on the principle of a ‘risk-based’ approach to inform and promote the proper use and management of public resources under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013.43

Compliance strategy for the original period of the scheme

3.4 At the first meeting of the JobKeeper Program Board on 14 April 2020, it was stated that ‘the highest level of assurance and integrity is maintained to monitor and act to identify and prevent apparent misuse and fraud’. A ‘JobKeeper Payment: Compliance Risk Framework’ was included in the Program Board papers. The draft framework set out the ATO’s top eight risks for JobKeeper payments and the intended payment action for each risk: ‘Payments should be stopped’ or ‘Pay but review before second payment’ (Figure 3.1). The draft framework also outlined the ATO’s intended mitigation measures for the top eight risks.

Figure 3.1: The ATO’s top eight risks from its draft JobKeeper Payment: Compliance Risk Framework (14 April 2020)

Source: ANAO, based on the ATO’s records.

3.5 Separate to the draft compliance risk framework, the ATO progressively developed a compliance strategy. Six iterations of the strategy were presented to the Program Board between 21 April and 3 July 2020. The Program Board suggested ways to improve the strategy, including ensuring the identified risks are examined from a ‘whole of ATO compliance lens’. The Program Board noted that the risks identified for the JobKeeper scheme could be applicable to the other stimulus measures being administered by the ATO.

3.6 The compliance strategy was presented to the ATO Executive Committee44 on 30 June 2020. A companion paper45 noted that the intent was to:

- support an economic stimulus package with the principal policy aims of keeping people in business and employment;

- pay JobKeeper payments to businesses as quickly as possible with minimal friction points and high levels of certainty for those that are entitled; and

- identify and treat those who are not entitled, have made mistakes or who intentionally defraud the system.

3.7 The Commissioner noted that the compliance program was both comprehensive and collaborative. The Commissioner emphasised the importance of obtaining and retaining the learnings and ensuring that the capability was systemised and held within the ATO for future initiatives.

3.8 The final version of the compliance strategy, presented to the Program Board on 3 July 2020, included the objective ‘To provide confidence that we will make timely payments while maintaining integrity and fairness and dealing with fraud to the system’. The strategy outlined assurance approaches and specific risk tolerances for 10 identified risks covering entity eligibility, employee eligibility, JobKeeper obligations and decline in turnover declarations (Appendix 6).

3.9 As with the draft compliance risk framework, a feature of the compliance strategy was a combination of pre-payment and post-payment verification. Pre-payment verification included the option of ‘suppressing’ (stopping) payments that triggered pre-set risk rules. At the enrolment stage from 20 April 2020 onwards, the ATO’s intended strategy was to block entities identified in the Rules as being ineligible for JobKeeper payments from progressing to the application stage of the scheme.

3.10 For the original period of the scheme, the ATO developed ‘treatment plans’ for eight payment risks (Table 3.1), which set out the ATO’s detailed intentions about how to manage the specific payment risks.

Table 3.1: Risk-specific treatment plans prepared by the ATO for the original period

|

Name of risk treatment plan |

Relating to |

Date on risk treatment plan |

|

JobKeeper Turnover Test |

Decline in turnover test in the Rules (for entities managed by the ATO’s Public Groups and Internationala, and Private Wealth business lines) |

22 May 2020 |

|

JobKeeper Turnover Test |

Decline in turnover test in the Rules (for entities managed by the ATO’s Small Business business line) |

13 July 2020 |

|

Eligible Business Participant |

Requirement in the Rules that only one eligible business participant can be claimed for an entity |

Undated |

|

Employee Verification Risk Mitigation Strategies |

Incorrect claiming of employees, including over-claiming by employers |

Undated |

|

Wage Condition |

Requirement in the Rules for employees to be paid before the employer is reimbursed by the ATO |

26 May 2020 |

|

Signs of Life |

Requirement in the Rules that on 1 March 2020 an entity carried on a business in Australia or was a non-profit body that pursued its objectives principally in Australia |

26 May 2020 |

|

Identity Fraud |

Integrity of individuals’ details (employees) for whom JobKeeper payments are claimed |

26 May 2020 |

|

JobKeeper/JobSeeker |

Rules preventing simultaneous receipt of JobKeeper and JobSeeker payments |

26 May 2020 |

Note a: Previously called Public and Multinational Businesses.

Source: ANAO, based on the ATO’s records.

3.11 There was broad alignment between the payment risks identified in the compliance risk framework, compliance strategy and risk treatment plans.

3.12 The ATO’s governance arrangements for the JobKeeper scheme did not specifically identify which person or body was responsible for approving the risk treatment plans. The June 2020 JobKeeper Program Board Charter did not include a specific role to review and approve the risk treatment plans for the original period of the scheme. The JobKeeper and JobMaker Hiring Credit Program Board Charter, which was formalised during the extension period, also did not include a specific role to review or approve the risk treatment plans.

3.13 The ATO advised the ANAO that three business lines were responsible for the development and execution of the treatment plans for their relevant areas of focus46, in concert with the ‘stream lead’ for compliance.47 The three business lines and stream lead for compliance were responsible for reporting to the Senior Responsible Officer and the Program Board. The ATO was unable to demonstrate that all eight risk treatment plans had been formally approved within the relevant business lines or by the stream lead for compliance.

Compliance strategy for the extension period

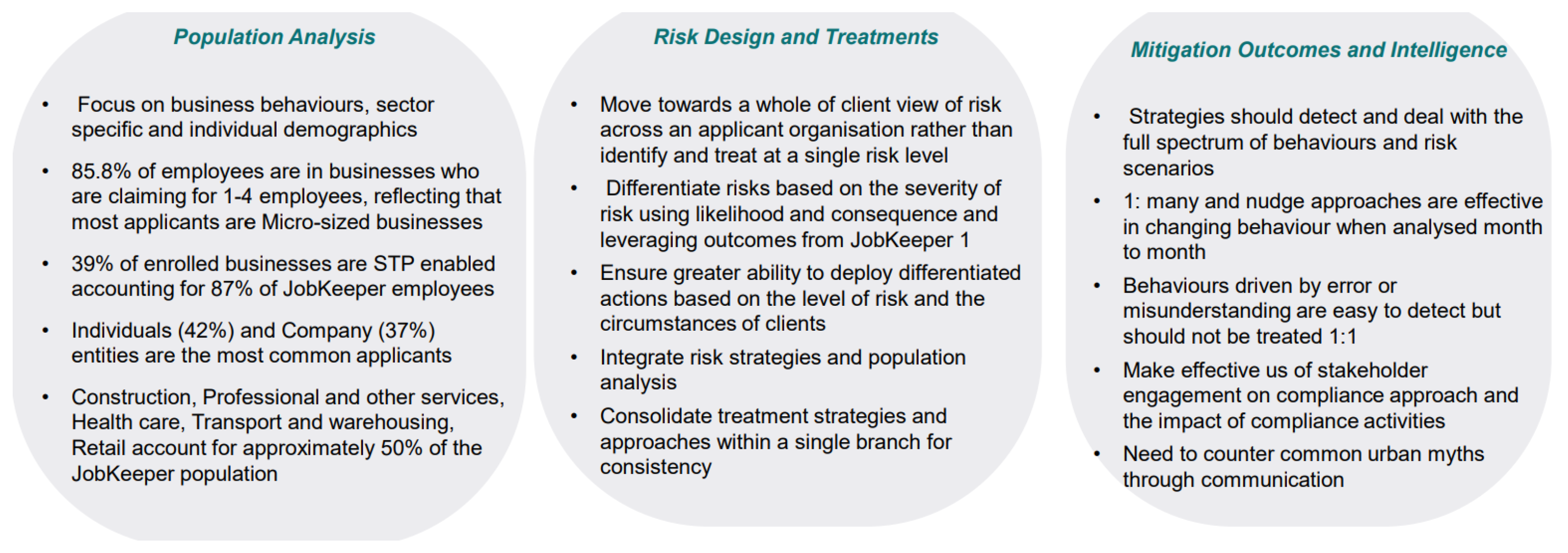

3.14 The ATO prepared a new compliance strategy for the extension period. A ‘JobKeeper Extension–Compliance Approach’ was provided for information to the Program Board at its 18 November 2020 meeting. The strategy reflected learnings from the original period (Figure 3.2).

3.15 The ATO designed a seven-step compliance model for the extension period based on a ‘whole of client’ view of risk across an entity (Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.2: ATO learnings from JobKeeper into JobKeeper extension

Note: ‘1:many’ refers to ATO bulk communications and ‘1:1’ refers to ATO engagement with individual taxpayers.

Source: Reproduced from the ATO’s records.

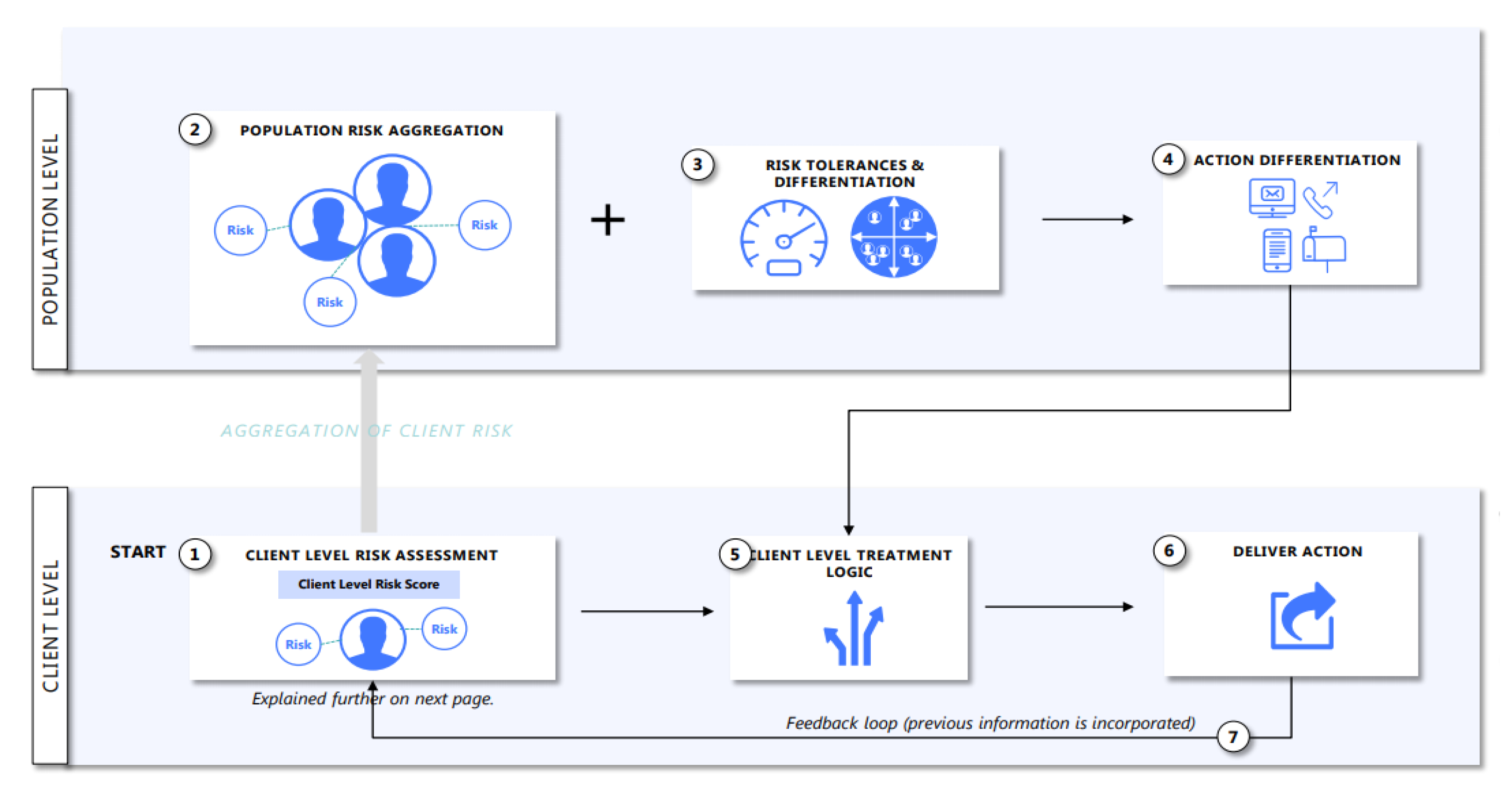

Figure 3.3: Overview of the ATO’s compliance model for the extension period

Source: Reproduced from the ATO’s records.

3.16 The extension period compliance model was designed to calculate an overall ‘Client Level Risk Score’ for each JobKeeper recipient, based on the likelihood of ineligibility and financial consequences of ineligibility (such as the number of employees being claimed for). The likelihood was to be derived from the client’s demographic characteristics (for example, type of industry) and six risks models, comprising: ‘Eligible business participant eligibility’, ‘Employee eligibility and (payment) tiers’, ‘Identity take over’, ‘Signs of life’, ‘Turnover’, and ‘Agents of threat’.

3.17 The ATO prepared treatment plans for seven payment risks in the extension period (Table 3.2). None of the seven risk treatment plans were dated and there was no evidence of the plans being approved in writing.

Table 3.2: Risk-specific treatment plans prepared by the ATO for the extension period

|

Name of risk treatment plan |

Relating to |

|

Employee Verification |

A range of risks associated with an employer/employee relationship such as employers claiming for ineligible employees |

|

Decline in Turnover |

The actual decline turnover test for the JobKeeper extension period |

|

Wage Condition |

Requirement that employers must pay their employees first, before being reimbursed by the ATO |

|

Intermediaries assurance COVID-19 response |

Reducing any adverse influence of tax agents or other intermediaries on the integrity of JobKeeper payments and other stimulus measures |

|

Eligible Business Participants |

Requirement that businesses can only claim a JobKeeper payment for one eligible business participant |

|

Eligible Business Participants Tier Payments |

Two new payment tiers for the JobKeeper extension period |

|

Residency |

Residency requirements for JobKeeper payments |

Source: ANAO, based on the ATO’s records.

Have key compliance and integrity measures been implemented as intended?

The ATO did not implement all key compliance and integrity measures as intended. Of the 22 compliance measures tested, two were partly implemented as intended, seven largely as intended and eight fully as intended. The ANAO was unable to conclude on five compliance measures due to data integrity issues. The ATO’s governance and internal reporting arrangements did not provide clear assurance on the implementation of the compliance measures.

3.18 To assess whether key compliance measures had been implemented as intended, the ANAO selected one or more compliance measures from each of the ATO’s 15 risk treatment plans. A total of 22 compliance measures were selected.48 The selection was principally based on compliance measures that the ATO had directed at higher-risk populations or behaviours, which were typically intended to involve direct engagement with JobKeeper recipients. Evidence was sought from the ATO on whether it had implemented the selected measures as intended or implemented any approved changes to the measures (Appendix 7).

3.19 The ATO provided ‘case lists’ of individual compliance activities extracted from its case management system, Siebel. The case lists represented the ATO’s initial claims about the implementation of intended compliance measures. The ATO provided lists of compliance cases for each of the 22 compliance measures selected by the ANAO. From a total of 41,031 compliance cases in the case lists across both the original and extension periods, 735 cases were selected for testing. For each compliance case, the ANAO sought evidence that the intended action had been undertaken.

Implementation of compliance measures

3.20 Of the 22 compliance measures tested, two were partly implemented as intended, seven largely as intended and eight fully as intended. For five measures comprising 202 compliance cases, the ANAO was unable to conclude on whether the intended compliance measures were implemented (Table 3.3).

- A total of 30 compliance cases with substantive exceptions – that is, where the ATO did not evidence that its intended compliance action had been fully undertaken or that an eligibility outcome had been recorded – were identified across nine of the 17 compliance measures that could be tested.

- There were 41 compliance cases across 16 of the compliance measure populations where issues were identified with the reliability of the ATO’s case lists. These included compliance cases that were created in error and closed without compliance action, and apparent duplicates in the case lists.

Table 3.3: ATO implementation of sampled compliance measures

|

Compliance measure |

Total compliance cases |

Sampled compliance cases |

Compliance cases with exceptions |

ANAO testing results |

|

|

Original period of the JobKeeper scheme |

|||||

|

1.1a |

Turnover Test – Public Groups & International and Private Wealtha |

100 |

18 |

0 |

|

|

1.1b |

Turnover Test – Public Groups & International and Private Wealtha |

86 |

86 |

1 |

|

|

1.2a |

Turnover Test – Small Businessb |

20 |

20 |

0 |

|

|

1.2b |

Turnover Test – Small Businessb |

30 |

30 |

1 |

|

|

1.2c |

Turnover Test – Small Businessb |

30 |

30 |

1 |

|

|

1.3 |

Eligible Business Participants |

4345 |

22 |

0 |

|

|

1.4a |

Employee Verification Riskc |

1062 |

41 |

2 |

|

|

1.4b |

Employee Verification Riskc |

4518 |

22 |

0 |

|

|

1.4c |

Employee Verification Riskc |

7 |

7 |

0 |

|

|

1.4d |

Employee Verification Riskc |

69 |

69 |

0 |

|

|

1.5 |

Wage Condition (Payment of Employees) |

49 |

49 |

15 |

|

|

1.6 |

Signs of Life |

16,657 |

42 |

0 |

|

|

1.7 |

Identity Fraud |

5814 |

22 |

1 |

|

|

Extension period of the JobKeeper scheme |

|||||

|

2.1a |

Employee Verificationd |

2599 |

41 |

The ANAO was unable to conclude on whether this compliance measure was implemented as intended |

|

|

2.1b |

Employee Verificationd |

260 |

20 |

6 |

|

|

2.1c |

Employee Verificationd |

973 |

40 |

The ANAO was unable to conclude on whether this compliance measure was implemented as intended |

|

|

2.2 |

Decline in Turnover |

638 |

40 |

The ANAO was unable to conclude on whether this compliance measure was implemented as intended |

|

|

2.3 |

Wage Condition (Payment of Employees) |

130 |

19 |

1 |

|

|

2.4 |

Agents and Intermediaries |

18 |

18 |

0 |

|

|

2.5 |

Business Participants |

703 |

40 |

The ANAO was unable to conclude on whether this compliance measure was implemented as intended |

|

|

2.6 |

Eligible Business Participants Tier Payments |

102 |

18 |

2 |

|

|

2.7 |

Residency |

2821 |

41 |

The ANAO was unable to conclude on whether this compliance measure was implemented as intended |

|

Note a: The ANAO tested two compliance measures selected from the ‘Turnover Test – Public Groups & International and Private Wealth’ treatment plan. Compliance measure 1.1a was directed at medium to high-risk entities selected through a risk filter, and 1.1b at selected Significant Global Entities.

Note b: The ANAO tested three compliance measures selected from the ‘Turnover Test – Small Business’ treatment plan. Compliance measure 1.2a was directed at entities that had self-prepared their Business Activity Statement, 1.2b at entities that reported increased sales, and 1.2c at entities that reported sales increasing from nil.

Note c: The ANAO tested four compliance measures selected from the ‘Employee Verification Risk’ treatment plan for the original period of the JobKeeper scheme. Compliance measure 1.4a was directed at entities that were at risk of claiming JobKeeper payments for an inflated number of employees, 1.4b at entities that were claiming the payment for employees without a (or with a backdated) pay as you go withholding role, 1.4c at potential multiple claims for the same individual, and 1.4d at entities at risk of claiming for fictitious employees.

Note d: The ANAO tested three compliance measures selected from the ‘Employee Verification’ treatment plan for the extension period of the JobKeeper scheme. Compliance measure 2.1a was directed at entities at risk of claiming JobKeeper payments for ineligible employees, 2.1b at employees at risk of receiving payments from multiple employers, and 2.1c at entities at risk of claiming payments for non-resident employees.

Source: ANAO, based on the ATO’s records.

3.21 The highest number of exceptions (15 among the 49 cases tested) was for the Wage Condition treatment plan for the original period, which was intended to ensure that employers receiving JobKeeper payments were paying their employees. The 15 exceptions comprised:

- five compliance cases that were closed together with no further attention given to the individual cases in February 2021 — six months after a review was opened — with no indication that the wage condition risk had been addressed;

- five compliance cases for which there was not sufficient evidence that the risk had been addressed (for example, no notes recorded);

- three compliance cases that were closed due to being ‘likely low risk’ although there was no confirmation that the risk had been addressed; and

- two compliance cases in which a case officer recorded that the risk had been addressed through the completion of an eligibility checklist; however, verifying the wage condition was not included on the checklist.

3.22 In relation to the ATO’s JobKeeper/JobSeeker risk treatment plan, JobKeeper data was regularly shared with Services Australia from May 2020 to March 2021. The principal aim of the data sharing was to identify persons who were in receipt of both JobKeeper and JobSeeker payments — which was not permitted under the JobSeeker payment rules.

3.23 The five compliance measure populations where testing was not able to determine whether they had been implemented as intended involved the application of the ATO’s ‘Action Differentiation Framework’ (ADF) — a key element of the extension period compliance model. The intent of the ADF was to align the treatment approach to the identified level of risk. Each entity was assigned to one of four ADF categories:

- Detect and monitor — monitoring groups of entities for risk through data analysis;

- Detect, educate and encourage — promoting compliance across a group of entities through outbound telephone calls, emails and letters to entities;

- Detect and review — reviewing high-risk payments without applying a suppression; or

- Detect, stop and review — suppressing the highest-risk payments prior to review.

3.24 During the ANAO’s initial testing of the five populations, inconsistencies were identified in all five populations between the action recorded in the ATO’s case lists and the compliance action that was evident from the ATO’s case documentation. There were 106 inconsistencies among the 202 sampled compliance cases in these five populations. These included 47 compliance cases where ‘detect, stop and review’ was recorded in the case list, but there was no evidence of payments being suppressed before the review commenced, or at all. A further eight cases were identified where either ‘detect, stop and review’ or ‘detect and review’ was recorded in the case list, but there was no evidence of a review being completed. Following testing, the ATO advised the ANAO that the ADF category recorded in the case lists was not a reliable indicator of the ATO’s intended action:

The ADF categories were not always final actions undertaken by the ATO. Each risk was monitored on an ongoing basis … Where the action taken does not match the ADF, a decision would be made based on a number of factors… The ADF rating in these cases would not be solely relevant in selection. The data showing the ADF category does not get updated if we [the ATO] decide to undertake a review on the client. The ADF is based on automated risk models and is not manually changed if for example a risk manager decides to review a ‘monitor’ ADF case.

3.25 On this basis, no finding could be made on whether the ATO’s compliance measures over the five affected populations were implemented as intended.

Oversight of compliance measures

3.26 The ATO’s governance arrangements for the JobKeeper scheme did not specifically identify which person or body was responsible for overseeing the implementation of the risk treatment plans for the original period of the scheme. The ATO advised the ANAO that its existing business lines were responsible for the development and execution of the treatment plans for their relevant areas of focus. No document was provided to support this advice or to set out the respective responsibilities of business lines and the Program Board.

3.27 The Program Board received a range of reporting on the ATO’s compliance strategies, activities and outcomes. In addition, there was evidence of progress and outcomes reporting being provided within the business lines for some of the risk treatment plans.

- A ‘Strategy Finalisation Report’ (dated 23 October 2020) on the Small Business Decline in Turnover Risk treatment plan provided to an Assistant Commissioner in the Small Business line.

- An ‘Evaluation Report’ provided on 1 December 2020 to the Strategic Management Committee within the ATO’s Public Groups and International business line on the decline in turnover compliance measures undertaken within this business line.

- A ‘Risk Insights Report’ provided to the ATO’s stream lead for compliance (Assistant Commissioner level) on 5 October 2020 outlining compliance activities undertaken within the Private Wealth business line for the decline in turnover risk.

3.28 The reporting to the Program Board did not typically provide a clear ‘line of sight’ back to the intended compliance measures from the ATO’s risk treatment plans.

Did the ATO conduct ‘decline in turnover’ reviews in accordance with its internal procedures?

While the ATO conducted decline in turnover reviews in accordance with its internal procedures, the nature of the ATO’s procedures and variability in the documentation maintained did not provide strong assurance on the assessed eligibility of entities that were reviewed.

3.29 The decline in turnover test was a key eligibility requirement for the JobKeeper scheme and an area of focus for the ATO’s compliance activities. The ATO’s published guidance emphasised the need for an entity’s projected decline in turnover to be ‘reasonable’ and for the entity to maintain records to demonstrate that a reasonable approach was taken.49

3.30 The extension period compliance strategy stated that over 1000 ‘decline in turnover reviews’ had been undertaken by business lines on applications received during the original period of the scheme and that over 97 per cent of the cases reviewed were found to be eligible. A similar result was reported publicly. On 10 September 2021, the Commissioner advised the Senate Economics Legislation Committee that:

We have undertaken a comprehensive review of cases that forecast a decline in turnover and found the vast majority of taxpayers undertook the projected decline in turnover test in good faith. From our review of more than 1,600 entities across all markets, including 480 large businesses, we found more than 95% were eligible.50

Decline in turnover reviews

3.31 The ANAO asked the ATO to provide a list of the decline in turnover reviews that were referenced in the compliance strategy. From a list of 1619 decline in turnover reviews provided by the ATO in March 202151, a sample of 40 reviews was selected by the ANAO for testing. The sample comprised 30 cases listed as ‘eligible’ and 10 cases listed as ‘ineligible’. Reviews were undertaken by three business lines — Public Groups and International, Private Wealth, and Small Business.

3.32 The ATO developed a range of internal procedures and guidance material to support the decline in turnover reviews. This included a ‘risk guide’, first issued on 10 July 2020, designed to assist staff when actioning activities relating to entities identified as potentially not meeting the decline in turnover test. The risk guide set out four main tasks for ATO staff to complete and included different guidance for the three business lines conducting the decline in turnover reviews.

- Profile the client to understand the risk.52

- Understand the product that is being recommended.

- Contact the client.

- Determine the outcome.

3.33 For Public Groups and International, the options for conducting a decline in turnover review included sending a ‘nudge’ email to the taxpayer where they were of a ‘lower consequence’ (fewer than 25 employees) or a Significant Global Entity that was applying the 30 per cent decline in turnover rate and had not experienced an actual decline of 50 per cent or more (Appendix 4).53 The risk guide stated that the nudge approach was designed to prompt entities to reconsider their eligibility for JobKeeper payments by checking for any errors in their decline in turnover test. The ATO advised the ANAO that 113 nudge emails were sent by the Public Groups and International business line.54

3.34 The risk thresholds that underpinned the nudge email for Public Groups and International were not required to be applied by the two other business lines — Private Wealth and Small Business. The ATO advised the ANAO that the different thresholds and treatments across the three business lines was attributed to three factors:

- ATO policy to segment the taxpayer population by different client experiences;

- the differences in the severity of behaviours that caused risks to manifest; and

- the risks that were being treated.

3.35 Public Groups and International also had the option of issuing a formal request for information, seeking detailed source documents from the taxpayer. The risk guide stated that this approach was to be used by exception and only after a telephone questionnaire had been used. The ATO advised the ANAO that no formal requests for information were issued.

Implementation of decline in turnover reviews

3.36 The main issues identified by the ANAO through testing concerned the nature of the evidence sought and received by the ATO to gain assurance that the entity had satisfied the decline in turnover test.

3.37 A requirement in the ATO’s risk guide, which applied to all three business lines, was the need to obtain documents to substantiate the entity’s decline in turnover claims. Where documentation was directly sought from entities in line with this requirement, there was variability in the nature and quality of the records provided. Some entities provided a spreadsheet including only a decline in turnover calculation, which provided no indication of when the calculation was completed. The ATO acknowledged the general variability of the documentation and advised the ANAO that ‘there was no definition of what records were required to be kept or how to present the calculation, so we received large variations between clients.’

3.38 In three cases where direct contact was made (which were all assessed to be eligible), no documentation was included in the ATO’s records. The ATO advised the ANAO that these three cases were part of a private group comprising 29 employer entities. In such cases, the ATO’s risk guide allowed the Private Wealth business line to determine which employer entities to request working papers from, having regard to factors such as the number of employees and the expected impact on the relevant industry. The ATO’s records indicate that working papers were requested from six of the 29 entities.

3.39 The ANAO’s testing sought to identify whether the ATO obtained evidence from entities on when the decline in turnover projection was made and who prepared the projection. This first aspect reflected a principle in the ATO’s published guidance that the decline in turnover projection needed to be a reasonable assessment of what was likely at the ‘point in time’ an entity calculated the test.55 The ATO was generally accepting of entity assertions with regard to the manner in which the decline in turnover test was completed and did not seek to verify the responses provided, by, for instance, requesting primary documentation to evidence the date on which the projections were produced (such as emails or board papers). This reduced the intended assurance that entities had completed their decline in turnover projection before they submitted their application.

3.40 In conducting the reviews, the ATO typically sought to identify which decline in turnover test the entity used to establish their eligibility — the basic test, the alternative test or the modified alternative test for group employers. As discussed in Chapter 2 (paragraph 2.16), the ATO’s online form for the original JobKeeper scheme did not require entities to specify which test was used.

3.41 The sampled reviews included one case, categorised as eligible, where a nudge email was sent to the entity. The ATO’s profiling document noted that the entity’s reported revenue increased by 152 per cent, whereas a decline of 50 per cent had been nominated on the entity’s application form. The entity was categorised as ‘low consequence’ (fewer than 25 employees), in line with the ATO’s risk guide for the Public Groups and International business line. The nudge email encouraged the entity to review its eligibility for JobKeeper payments and contact the ATO to discuss any issues. The ATO’s records state that no response was received. Based on the information gathered by the ATO, the potential overpayment was up to $360,000.

3.42 The ATO’s risk guide provided the three business lines with different options for profiling the client and recording the outcome. The ATO created profiling templates and an ‘analysis and decision template’, but these were not required to be used across the three business lines. The ANAO observed variability in the ATO’s documentation in relation to the entity profiling step and recording the outcome of the review.

3.43 For the 10 sampled reviews that were assessed by the ATO as ‘ineligible’, the ATO provided sufficient evidence that the proposed decisions were referred for approval in line with the requirements for each business line set out in the risk guide.

Has the ATO exercised discretion on overpayments in accordance with its internal policies and procedures?