Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Fraud Control Arrangements in the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- Fraud against the Commonwealth makes less money available for public goods and services.

- All Commonwealth entities are required to have arrangements in place to prevent, detect and deal with fraud.

- This audit is part of a series of three audits intended to provide assurance to Parliament on the selected entities’ fraud control arrangements, and assist other entities to consider the effectiveness of their fraud control arrangements.

Key facts

- The Australian Government has set out its requirements for fraud control in the 2017 Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework.

- All non-corporate Commonwealth entities are required to follow the framework’s fraud policy and should implement better practice fraud guidance, as relevant.

- As the accountable authority, the department’s Secretary is required to take all reasonable measures to prevent, detect and deal with fraud against the department.

What did we find?

- Fraud control arrangements in the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade are largely effective.

- The department’s arrangements comply with the mandatory requirements of the Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework.

- The department has also implemented arrangements that are largely consistent with the whole of government better practice fraud guidance.

- The accountable authority has promoted a fraud aware culture, with further attention required to address low levels of compliance with mandatory fraud awareness training requirements.

What did we recommend?

- The Auditor-General made three recommendations regarding clarity in the assignment of responsibility for controls, updating aspects of investigations procedures, and improved compliance with mandatory fraud awareness training.

- The Department agreed to the recommendations.

31-65%

The proportion of staff that completed mandatory fraud awareness training between 2018 and 2020.

205

The number of finalised fraud investigations in 2018–19.

152 (74%)

The number of finalised investigations first identified from a tip off from staff or the public.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. The Australian Government (the government) defines fraud as:

Dishonestly obtaining a benefit or causing a loss by deception or other means.1

2. Fraud requires intent, and is more than carelessness, accident or error. Without intent, an incident may indicate non-compliance rather than fraud.2

3. Fraud against the Commonwealth can be committed by Commonwealth officials or contractors (internal fraud) or by external parties such as clients, service providers, members of the public or organised criminal groups (external fraud).3 In some cases fraud against the Commonwealth may involve collusion between external and internal parties, and can include corrupt conduct such as bribery. However, not all corrupt conduct meets the definition of fraud.4

4. Australian Government entities have long been required to establish arrangements to manage fraud risks. The government’s requirements for fraud control are contained in the 2017 Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework5 (the Framework) pursuant to the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act). The Framework comprises three tiered documents — the fraud rule, fraud policy and fraud guidance — with different binding effects for corporate and non-corporate Commonwealth entities.6 The Attorney-General’s Department is responsible for administering the Framework.

5. As non-corporate Commonwealth entities, Australian Government departments must comply with the fraud rule and fraud policy. While the fraud guidance is not binding, the government considers the guidance to be better practice and expects entities to follow it where appropriate.7

6. This audit is one in a series of three performance audits reviewing fraud control arrangements in selected departments — the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, the Department of Home Affairs, and the Department of Social Services. The focus of this audit report is the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

7. This audit series is intended to provide assurance to the Parliament regarding the fraud control arrangements of selected Australian Government departments. All Commonwealth entities are required to have fraud control arrangements in place because preventing, detecting and responding to fraud against the Commonwealth is necessary to ensure the proper use of public resources, financial and material losses are minimised, and public confidence is maintained. In addition, this audit series aims to assist all Commonwealth entities to consider the effectiveness of their fraud control arrangements, including areas where additional effort would improve consistency with whole of government better practice fraud guidance (discussed in paragraph 5) and the take-up of whole of government advice on new and emerging fraud risks (discussed in paragraph 10).

Audit objective and criteria

8. The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s fraud control arrangements. The high level audit criteria were that the department:

- complies with the mandatory requirements set out in the Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework and arrangements are consistent with the government’s better practice guidance; and

- promotes a fraud aware culture.

9. The ANAO did not assess whether specific controls are in place or the effectiveness of such controls in the selected entity.8

10. The ANAO reviewed fraud control arrangements in place within the department during the period of audit fieldwork, September 2019 to early February 2020. On 18 February 2020 the Australian Government activated the Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19).9 On 27 March 2020 the Australian Federal Police’s Operation Ashiba and the Commonwealth Counter Fraud Prevention Centre in the Attorney-General’s Department established the Commonwealth COVID-19 Counter Fraud Taskforce intended to support Commonwealth agencies to prevent fraud against the COVID-19 economic stimulus measures.10 The Commonwealth Fraud Prevention Centre circulated the Fraud Control in COVID-19 Emergency and Crisis Management fact sheet to Commonwealth entities, with information about key fraud risks related to COVID-19 response efforts.

11. The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade was invited by the ANAO to make a representation in relation to its current or planned arrangements to address increased fraud risks resulting from the COVID-19 response. The department advised the ANAO in June 2020 that:

In response to COVID-19, DFAT undertook assessments of risk and whole of Government consultations to inform the focus for fraud operations.

The department has and will continue to concentrate on (a) ensuring continuity in case referrals and management under remote working; and (b) proactive engagement and communications with internal and external stakeholders emphasising practical up-front counter-measures to disrupt and reduce the impacts of fraud. An ‘infographic’ on how to manage fraud under COVID-19 in DFAT specific operations has been circulated to staff.

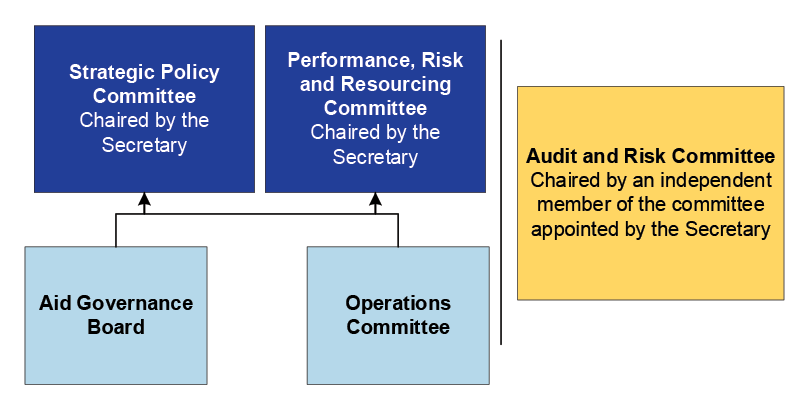

DFAT governance committees, including the Audit and Risk Committee and the Performance, Risk and Resourcing Committee, were briefed on the approach (in April and May respectively). Deputy Secretaries and First Assistant Secretaries have emailed internal and external stakeholders emphasising core principles for fraud prevention.

DFAT is participating in the whole of Australian Government Senior Officers Fraud Forum. The Fraud Control Section has sent a Cable to all staff and portfolio agencies sharing fraud related insights from the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission. Further whole of Government products have and will continue to be circulated across the Department.

Conclusion

12. Fraud control arrangements in the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade are largely effective. The department’s arrangements comply with the mandatory requirements of the Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework, are largely consistent with the whole of government better practice fraud guidance, and the accountable authority has taken steps to promote a fraud aware culture. Further attention is required to address low levels of compliance with mandatory fraud awareness training requirements and to improve consistency with internal requirements by identifying fraud control owners and updating investigations procedures.

13. The department has developed and implemented a fraud control plan, completed fraud risk assessments and has guidance and procedures to assist officials to understand what constitutes fraud and to carry out their fraud prevention responsibilities.

14. The department has mechanisms in place to assess and provide assurance of its controls. Internal reporting and oversight would be strengthened by: requiring business areas to report on progress to reduce fraud risks above the tolerance level; and ensuring that responsibility for controls is assigned by position, in line with internal guidance.

15. The department has put in place controls to detect fraud, including reporting channels for use by staff and members of the public. The department’s fraud investigation procedures are largely consistent with the Australian Government Investigations Standards, with attention required to update some procedures.

16. The department has taken steps to promote a fraud aware culture and meets the reporting requirements set out in the framework. While there is internal messaging to staff about fraud control and a program of mandatory fraud awareness training, completion rates for that training are consistently low. Recent remediation measures are credited with improved compliance, but continued attention is required as failure to adequately address non-compliance with mandatory requirements communicates to staff that compliance is optional.

Supporting findings

Risk management, planning and prevention

17. The department considers fraud risk in the context of its overarching risk management framework. Fraud risks must be considered by departmental officials when they are conducting risk assessments. The Secretary’s expectation for work areas to control fraud in their activities is documented in the fraud control plan. The department’s fraud toolkit for staff provides information and instructions to assist staff to meet this expectation.

18. As required by the fraud rule, fraud risks are identified and the assessments are conducted at regular intervals. The department conducted a fraud risk assessment in 2017 prior to the development of the fraud control plan. In 2019, a fraud risk assessment for seven (mostly financial) business processes was conducted. Both fraud risk assessments involved consultation with relevant areas across the department. Departmental staff have or are in the process of gaining qualifications in fraud control.

19. Fraud risks are assessed and given a fraud risk exposure rating based on the likelihood and consequences of the risk occurring. Depending on the assessed exposure rating and having regard to the department’s tolerance level, these risks are then addressed with responses ranging from monitoring to actively treating the risk. Of the 91 fraud risks identified in the department’s 2017 fraud risk assessment, seven (7.7 per cent) were identified in internal reporting as ‘critical’ fraud risks. One additional ‘critical’ risk was identified in the department’s 2019 fraud risk assessment. The department took action to address these ‘critical’ fraud risks and reported on the actions taken to mitigate these risks to its Executive.

20. The department has a range of preventive controls in place to prevent fraud and tests its controls to ensure they are operational. The department has undertaken control reviews and has mechanisms in place to provide assurance around its control environment. These mechanisms could be better supported by clear assignment of control owners, by position, in line with the department’s risk management guide.

Detection, investigation and response

21. The department has processes for departmental staff and others (such as members of the public and funding recipients) to confidentially report allegations of fraud. The department’s main source of fraud detection is tip offs from within the department (for allegations of internal fraud) or from sources external to the department (for allegations of external fraud). The department has a publicly available procedure for handling Public Interest Disclosures. The department also detects fraud through other detective controls. These include internal audits, data analytics and forensic examination.

22. The department’s investigation procedures are largely consistent with the Australian Government Investigations Standards. The department’s policy and procedures for conducting investigations of suspected internal fraud require updating.

Culture, assurance and reporting

23. The department has set expectations and promotes a fraud aware culture through: a fraud strategy statement; a Fraud Control Toolkit for Funding Recipients; a fraud control plan; a conduct and ethics manual for departmental staff; a Fraud Control Toolkit for Staff; fraud awareness programs for funding providers; and internal messaging to all staff from the Secretary about fraud control. The department’s audit and risk committee charter and work plan allow the committee to review the department’s fraud risks. The committee has done so and provided reports to the Secretary.

24. Completion rates for the department’s mandatory fraud awareness training are consistently low — in the range of 31 to 65 percent between 2018 and 2020.

25. The department has provided assurance about its fraud control arrangements through reporting. The department has:

- met annual report requirements under subsection 17AG(2) of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014;

- complied with mandatory reporting obligations in the Commonwealth Fraud Control Policy to provide information to the Australian Institute of Criminology annually; and

- implemented the fraud guidance recommendation to keep the Minister informed about entity fraud control arrangements and significant issues.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 2.47

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s department-level fraud risk assessments identify control owners by position, in line with its risk management guide.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 3.24

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade update its policy and processes for fraud investigations to fully meet Australian Government Investigations Standards requirements.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.3

Paragraph 4.23

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade improves staff compliance relating to mandatory fraud awareness training.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) welcomes the report, which is part of a series of three audits on selected Commonwealth entities assessing the effectiveness of fraud control arrangements. We welcome the findings that fraud control arrangements are largely effective and the department’s arrangements comply with mandatory requirements of the Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework.

DFAT is committed to continuous improvement in our framework to prevent, detect and respond to fraud. Fraud undermines our ability to achieve objectives and reduces the effectiveness of the Australian Government’s policies and programs. We accept the audit report recommendations regarding identification of control owners by position, updating aspects of investigations procedures and improved staff compliance relating to mandatory fraud awareness training. DFAT will address these recommendations through ongoing update in our fraud control policies, procedures and guidelines.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

26. This audit is one in a series of three performance audits reviewing fraud control arrangements in selected non-corporate Australian Government entities:

- the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade;

- the Department of Home Affairs; and

- the Department of Social Services.

27. Key messages from this audit series will be outlined in an ANAO Insights product available on the ANAO website.

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Fraud against the Commonwealth causes financial and material loss, reducing the amount of money available for public goods and services and impacting on government’s ability to achieve its objectives. Fraud can also damage trust in government. Managing fraud risk is a responsibility shared by all Commonwealth officials, with ongoing effort commensurate to the scale of fraud risk required to effectively prevent, identify and respond to fraud. Fraud threats are constantly evolving, meaning responses need to be dynamic.

1.2 The Australian Government (the government) defines fraud as:

Dishonestly obtaining a benefit or causing a loss by deception or other means.11

1.3 Fraud requires intent, and is more than carelessness, accident or error. Without intent, an incident may indicate non-compliance rather than fraud.12 Fraud against the Commonwealth may include (but is not limited to):

- theft;

- accounting fraud (for example, false invoices, misappropriation);

- misuse of Commonwealth credit cards;

- unlawful use of, or unlawful obtaining of, property, equipment, material or services;

- causing a loss, or avoiding and/or creating a liability;

- providing false or misleading information to the Commonwealth, or failing to provide information when there is an obligation to do so;

- misuse of Commonwealth assets, equipment or facilities;

- cartel conduct;

- making or using, false, forged or falsified documents; and/or

- wrongfully using Commonwealth information or intellectual property.13

1.4 Fraud against the Commonwealth can be committed by Commonwealth officials or contractors (internal fraud) or by external parties such as clients, service providers, members of the public or organised criminal groups (external fraud).14 In some cases fraud against the Commonwealth may involve collusion between external and internal parties, and can include corrupt conduct such as bribery. However, not all corrupt conduct meets the definition of fraud.15

The Australian Government’s fraud control framework

1.5 Australian Government entities have long been required to establish arrangements to manage fraud risks. At the time of this audit, the government’s requirements for fraud control are contained in the 2017 Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework16 (the Framework) pursuant to the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act). A desktop review conducted by the ANAO of state and territory and international fraud control frameworks is presented at Appendix 2.

1.6 The Framework is intended to: allow Commonwealth entities to manage their fraud risks in a way which best suits the individual circumstances of the entity; and support the accountable authority17 to effectively discharge their responsibilities under the PGPA Act. The Framework comprises three tiered documents with different binding effects:18

- Section 10 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (the fraud rule): A legislative instrument binding all Commonwealth entities and setting out the key requirements of fraud control.

- The Commonwealth Fraud Control Policy (the fraud policy): An Australian Government policy binding non-corporate Commonwealth entities19 setting out procedural requirements for specific areas of fraud control such as investigations and reporting.

- Resource Management Guide No. 201 — Preventing, detecting and dealing with fraud (the fraud guidance): A better practice document setting out the government’s expectations in detail for fraud control arrangements within all Commonwealth entities.

1.7 As non-corporate Commonwealth entities, Australian Government departments must comply with the fraud rule and fraud policy. While the fraud guidance is not binding, the government considers it to be better practice and expects entities to follow it where appropriate.20

1.8 The Attorney-General’s Department (AGD) administers the Framework. The Australian Government is providing $16.4 million over two years from 2019–20 to AGD ($6.6 million) and the Australian Federal Police (AFP) ($9.8 million) to pilot and continue measures to strengthen Commonwealth counter-fraud arrangements.21 The AGD established the Commonwealth Fraud Prevention Centre, and is piloting measures to improve the sharing of data, information and knowledge across government. The AFP established Operation Ashiba to lead a Commonwealth multi-agency taskforce intended to support and strengthen whole of government efforts to detect, disrupt and respond to serious and complex fraud.

Responsibilities of accountable authorities

1.9 The PGPA Act and the PGPA Rule contain specific duties and requirements for the accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity pertaining to internal control arrangements, including for fraud control and relevant reporting (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1: Responsibilities of accountable authorities (PGPA Act and PGPA Rule)

|

Reference |

Duty or requirement |

|

Section 15 PGPA Act |

Duty to govern the Commonwealth entity 1. The accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity must govern the entity in a way that:

2. In making decisions for the purposes of subsection (1), the accountable authority must take into account the effect of those decisions on public resources generally. |

|

Section 16 PGPA Act |

Duty to establish and maintain systems relating to risk and control The accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity must establish and maintain:

including by implementing measures directed at ensuring officials of the entity comply with the finance law. |

|

Section 10 PGPA Rule |

Preventing, detecting and dealing with fraud The accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity must take all reasonable measures to prevent, detect and deal with fraud relating to the entity, including by:

|

|

Subsection 17AG(2) PGPA Rule |

Information on management and accountability The annual report must include the following:

|

Note a: In respect to ‘proper use’, section 8 of the PGPA Act provides that: ‘proper, when used in relation to the use or management of public resources, means efficient, effective, economical and ethical’.

Source: PGPA Act and PGPA Rule.

Extent of fraud against the Commonwealth

1.10 The Australian Government has reported that the extent of fraud against the Commonwealth, including the exact cost and impact, is unknown.22 Fraud can be hidden, difficult to detect or remain unreported. The Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) produces an annual report measuring levels of fraud detected and investigated across the Commonwealth on the basis of data self-reported by Commonwealth entities via an online questionnaire.23 The Commonwealth fraud investigations 2017–18 and 2018–19 report24 stated that of 155 entities with responses, 30 (19 per cent) commenced internal fraud investigations and 37 (24 per cent) commenced external fraud investigations. In total, 52 (34 per cent) different entities commenced investigations. In 2018–19, 27 (17 per cent) entities finalised internal fraud investigations and 34 (22 per cent) entities finalised external fraud investigations. In total, 44 (28 per cent) different entities finalised fraud investigations in the 2018-19 financial year. The AIC estimated fraud losses during 2018–19 of $149,680,728 ($2,775,917 from internal fraud; $146,904,811 from external fraud), on the basis of completed investigations where fraud could be quantified.25

1.11 The results of a desktop review by the ANAO of international research to estimate fraud losses is presented in Appendix 2.

Previous audits

1.12 The interim audit phase of the ANAO’s annual program of financial statements audits includes an assessment of the effectiveness of each entity’s internal controls as they relate to the risk of misstatement in the financial statements. Auditor-General Report No.46 2018–19 Interim Report on Key Financial Controls of Major Entities (the controls report) reported that at the completion of the ANAO’s interim audits for the 26 major entities included in that report, the key elements of internal control were operating effectively for 19 entities26, including the three departments selected for this performance audit series.27 In the context of the ANAO’s review of entity internal controls, the controls report included a focus on and an analysis of, payment card and fraud control policies together with a continued review of compliance with the Commonwealth’s finance law.28

1.13 Australian Government fraud control arrangements have also been the subject of previous ANAO performance audits. The most recent relevant audit was tabled in 2018–19 and examined the fraud control arrangements of the National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA). The audit found that while the NDIA was largely compliant with the requirements of the Commonwealth Fraud Rule29 there was scope to improve: fraud prevention strategies; measures to detect potential fraud; and the effectiveness of fraud control governance and reporting arrangements.30 A key learning for other government entities arising from the audit was that the Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework (not just the Fraud Rule) provides a robust framework for all government entities to manage fraud risk. In the absence of it being mandatory for corporate entities to comply with all elements of the framework, corporate entities should see its implementation as good practice.31

1.14 An ANAO audit tabled in 2014–15 of the fraud control arrangements of selected entities32 found that overall these entities were generally compliant with the applicable requirements of the 2011 Fraud Control Guidelines (the Guidelines) that were in effect during the course of the audit. The audit included one recommendation.

To facilitate the timely preparation of the annual Fraud Against the Commonwealth Report and the annual Compliance Report to Government, the ANAO recommends that the Attorney-General’s Department formalises its business arrangements with the Australian Institute of Criminology.33

1.15 From 1 July 2014, the Guidelines were replaced with the Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework pursuant to the PGPA Act. The fraud policy was reissued in August 2016, with new provisions implementing the ANAO recommendation detailed in paragraph 1.14 by formalising the requirement for entities to provide information to the AIC to facilitate the AIC annual fraud report.34 The fraud guidance was reissued in August 2017.35

Selected entities in this audit series

1.16 This audit is one in a series of three performance audits reviewing fraud control arrangements in selected departments — the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, the Department of Home Affairs and the Department of Social Services. The focus of this audit report is the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

1.17 Other audits in the series are:

- Auditor-General Report No.43 2019-20 Fraud Control Arrangements in the Department of Home Affairs; and

- Auditor-General Report No.44 2019-20 Fraud Control Arrangements in the Department of Social Services.

1.18 Contextual information about the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade is provided at Table 1.2.

Table 1.2: Contextual information about the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

|

Element |

Contextual information |

|

Entity mission/purpose |

To make Australia stronger, safer and more prosperous, to provide timely and responsive consular and passport services, and to ensure a secure Australian presence overseas. |

|

Number of staff (as at June 2019) |

6,078 — 3,136 overseas, including 2,276 locally engaged staff in overseas posts. |

|

Number of staff dedicated to fraud related dutiesa (as at June 2019) |

39 |

|

Total resourcing ($’000) (for 2018–19) |

6,205,906 |

|

Geographic location |

Worldwide locations — 109 locations overseas with an additional 11 posts managed by Austrade. Major office in Canberra, offices in every state and territory and the Torres Strait. |

Note a: ‘Fraud-related duties’ as defined within the 2018–19 AIC fraud questionnaire, could include work in fraud control policy, fraud risk management, prevention, detection, investigation, delivery of training and/or fraud reporting.

Source: ANAO drawing on the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade 2018–19 Annual Report, 2019–20 Portfolio Budget Statements and AIC 2018–2019 fraud questionnaire.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.19 This audit series is intended to provide assurance to the Parliament regarding the fraud control arrangements of selected Australian Government departments. All Commonwealth entities are required to have fraud control arrangements in place because preventing, detecting and responding to fraud against the Commonwealth is necessary to ensure the proper use of public resources, financial and material losses are minimised, and public confidence is maintained. In addition, this audit series aims to assist all Commonwealth entities to consider the effectiveness of their fraud control arrangements, including areas where additional effort would improve consistency with whole of government better practice fraud guidance (discussed in paragraphs 1.6 and 1.7) and the take-up of whole of government advice on new and emerging fraud risks (discussed in paragraph 1.22).

Audit approach

Audit objective, criteria and scope

1.20 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trades’ fraud control arrangements. The high level audit criteria were that the department:

- complies with the mandatory requirements set out in the Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework and arrangements are consistent with the government’s better practice guidance; and

- promotes a fraud aware culture.

1.21 The ANAO did not assess whether specific controls are in place or the effectiveness of such controls in the selected entity.36

1.22 The ANAO reviewed fraud control arrangements in place within the department during the period of audit fieldwork, September 2019 to early February 2020. On 18 February 2020 the Australian Government activated the Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19).37 On 27 March 2020 the Australian Federal Police’s Operation Ashiba and the Commonwealth Counter Fraud Prevention Centre in the Attorney-General’s Department established the Commonwealth COVID-19 Counter Fraud Taskforce intended to support Commonwealth agencies to prevent fraud against the COVID-19 economic stimulus measures.38 The Commonwealth Fraud Prevention Centre circulated the Fraud Control in COVID-19 Emergency and Crisis Management fact sheet to Commonwealth entities, with information about key fraud risks related to COVID-19 response efforts.

1.23 The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade was invited by the ANAO to make a representation in relation to its current or planned arrangements to address increased fraud risks resulting from the COVID-19 response. The department advised the ANAO in June 2020 that:

In response to COVID-19, DFAT undertook assessments of risk and whole of Government consultations to inform the focus for fraud operations.

The department has and will continue to concentrate on (a) ensuring continuity in case referrals and management under remote working; and (b) proactive engagement and communications with internal and external stakeholders emphasising practical up-front counter-measures to disrupt and reduce the impacts of fraud. An ‘infographic’ on how to manage fraud under COVID-19 in DFAT specific operations has been circulated to staff.

DFAT governance committees, including the Audit and Risk Committee and the Performance, Risk and Resourcing Committee, were briefed on the approach (in April and May respectively). Deputy Secretaries and First Assistant Secretaries have emailed internal and external stakeholders emphasising core principles for fraud prevention.

DFAT is participating in the whole of Australian Government Senior Officers Fraud Forum. The Fraud Control Section has sent a Cable to all staff and portfolio agencies sharing fraud related insights from the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission. Further whole of Government products have and will continue to be circulated across the Department.

Audit methodology

1.24 The audit methodology involved:

- assessing entity arrangements against the mandatory requirements of the Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework;

- reviewing entity records;

- reviewing entity procedures for planning, prevention, detection, investigation and responding to fraud and allegations of fraud, against the fraud guidance; and

- discussions with relevant entity staff.

1.25 To assess the department’s compliance with the Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework, the ANAO has read the fraud rule in conjunction with the fraud guidance, and has based its assessment and findings on the suite of documents produced by the department to support fraud control planning

1.26 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $215,000.

1.27 The team members for this audit were Tracy Cussen, Ailsa McPherson, Michael Fitzgerald, Hannah Climas and Michelle Page.

2. Risk management, planning and prevention

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the department has complied with the mandatory requirements set out in the Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework as they relate to fraud prevention and the extent to which these arrangements are consistent with the Australian Government’s fraud guidance.

Conclusion

The department has developed and implemented a fraud control plan, completed fraud risk assessments and has guidance and procedures to assist officials to understand what constitutes fraud and to carry out their fraud prevention responsibilities.

The department has mechanisms in place to assess and provide assurance of its controls. Internal reporting and oversight would be strengthened by: requiring business areas to report on progress to reduce fraud risks above the tolerance level; and ensuring that responsibility for controls is assigned by position, in line with internal guidance.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has made one recommendation, aimed at ensuring that responsibility for identified fraud controls is clearly assigned in department-level fraud risk assessments.

The ANAO has also suggested that business areas report to the department’s Fraud Control Section on progress to reduce fraud risks above the tolerance level, to improve reporting to the departmental executive.

2.1 Section 10 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (the fraud rule) requires the accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity to take all reasonable measures to prevent fraud relating to the entity.39 In order to prevent fraud, entities must understand their fraud risks and ensure arrangements are in place to prevent fraud from occurring.

2.2 The ANAO examined entity compliance with the mandatory requirements of the Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework and the extent to which entity arrangements are consistent with Resource Management Guide No. 201 — Preventing, detecting and dealing with fraud (the fraud guidance), to assess:

- whether the entity has considered fraud risk management within the context of its overall risk management process, including the content of the entity’s fraud control plan;

- how fraud risks are identified and whether these assessments are conducted at regular intervals;

- how identified fraud risks are assessed and addressed; and

- whether preventive controls to manage fraud risks have been identified and are being adequately assessed.

Is fraud risk considered within the context of the overall risk management process?

The department considers fraud risk in the context of its overarching risk management framework. Fraud risks must be considered by departmental officials when they are conducting risk assessments. The Secretary’s expectation for work areas to control fraud in their activities is documented in the fraud control plan. The department’s fraud toolkit for staff provides information and instructions to assist staff to meet this expectation.

2.3 As a non-corporate Commonwealth entity, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT or the department) is bound by the Australian Government’s Commonwealth Fraud Control Policy (fraud policy), which states that:

Non-corporate Commonwealth entities must ensure that their fraud control arrangements are developed in the context of the entity’s overarching risk management framework as described in the Commonwealth Risk Management Policy.40

2.4 In addition, the fraud guidance states that:

It is important to avoid looking at fraud in isolation from the general business of the entity. Entities are strongly encouraged to develop dynamic fraud risk assessment procedures integrated within an overall business risk approach rather than in a separate program.41

2.5 To assess whether fraud risk is considered within the context of DFAT’s overarching risk management process, the ANAO reviewed how fraud is considered in the department’s risk management guide and assessed whether the contents of the department’s fraud control plan contained the components suggested in the fraud guidance.

DFAT’s risk management guide

2.6 The Secretary42 issued the risk management guide (the risk guide) in December 2018, with an updated version released in February 2020. The guide aims to help departmental officials manage risk in delivering on the department’s objectives. The guide contains the department’s risk management framework, which is:

The sum of all the policies, procedures, and governance structures that directly or indirectly guide the behaviour and actions of officers to manage risks in the pursuit of objectives.

2.7 The department’s risk management guide is intended to support the department’s compliance with the Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework. While specific risks the department faces in delivering on its objectives are not detailed in the risk guide, the guide does identify risk policy areas. These are areas with risks that are managed through additional policy, processes and guidance. The risk management guide categorises fraud risk as a risk policy area, and as such, departmental officials must consider fraud risk when conducting risk assessments if they consider fraud risk to be relevant.

DFAT’s fraud control plan

2.8 Subsection 10(b) of the fraud rule states that the accountable authority must develop and implement ‘a fraud control plan that deals with identified risks as soon as practicable after conducting a risk assessment’.43

2.9 In accordance with the fraud rule the department undertook a fraud risk assessment and then developed its fraud control plan. The department undertook its fraud risk assessment in November 2017 (this process is reviewed from paragraph 2.27) and the current fraud control plan was issued by the Secretary on 1 September 2018. The fraud control plan contains the department’s fraud control framework; sets out the department’s strategies to meet the mandatory requirements for fraud control in the Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework; and documents the Secretary’s expectation that work areas control for fraud in their activities.

2.10 To assist staff to carry out their responsibilities under the fraud control plan, the department has developed a fraud control toolkit. The toolkit addresses how staff can comply with their obligations to prevent and detect fraud.

2.11 The fraud guidance suggests that fraud control plans can:

Document the entity’s approach to controlling fraud at a strategic, operational and tactical level, and encompass awareness raising and training, prevention, detection, reporting and investigation measures.44

2.12 The department’s fraud control plan contains all of the components suggested by the fraud guidance (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1: Content of DFAT’s fraud control plan

|

Fraud guidance suggested areas |

DFAT fraud control plan |

|

A summary of fraud risks and vulnerabilities associated with the entitya |

Yes |

|

Treatment strategies and controls put in place to manage fraud risks and vulnerabilitiesb |

Yes |

|

Information about implementing fraud control arrangements within the entity |

Yes |

|

Strategies to ensure the entity is meeting its training and awareness needs |

Yes |

|

Mechanisms for collecting, analysing and reporting fraud incidents |

Yes |

|

Protocols for handling fraud incidents |

Yes |

|

An outline of key roles and responsibilities for fraud control within the entityc |

Yes |

Note a: Fraud risks are summarised into nine fraud risk domains and included in the fraud control plan. Fraud risk domains are intended to identify systemic risks in the department.

Note b: Fraud controls are organised into the nine fraud risk domains, and then further organised into strategic and operational controls, and governance owners. Organising fraud controls in this way is intended to help identify vulnerabilities in controls from a strategic perspective.

Note c: Appendix 3 of this audit report outlines roles and responsibilities for fraud control within DFAT as detailed in the department’s fraud control plan.

Source: Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework and ANAO analysis of DFAT documentation.

Are fraud risks identified and are assessments conducted at regular intervals?

As required by the fraud rule, fraud risks are identified and assessments are conducted at regular intervals. The department conducted a fraud risk assessment in 2017 prior to the development of the fraud control plan. In 2019, a fraud risk assessment for seven (mostly financial) business processes was conducted. Both fraud risk assessments involved consultation with relevant areas across the department. Departmental staff have or are in the process of gaining qualifications in fraud control.

2.13 Subsection 10(a) of the fraud rule requires the accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity to conduct ‘fraud risk assessments regularly and when there is a substantial change in the structure, functions or activities of the entity.’45 The fraud guidance encourages entities to conduct fraud risk assessments at least every two years.46

2.14 The fraud policy requires that:

Entities must ensure officials primarily engaged in fraud control activities possess or attain relevant qualifications or training to effectively carry out their duties.47

2.15 The fraud guidance identifies that relevant training can include a Certificate IV in Government (Fraud Control) or equivalent qualification for officials implementing fraud control, or a Diploma of Government (Fraud Control) or equivalent qualification for officials managing fraud control.48

2.16 The ANAO reviewed when fraud risk assessments had been undertaken and examined the department’s process for identifying fraud risks, including whether staff conducting these assessments are appropriately trained.

2.17 The department’s fraud control plan states that the department’s fraud control section conducts regular fraud risk assessments to identify areas vulnerable to fraud.

2.18 In November 2017, the department undertook a fraud risk assessment of all departmental corporate functions and departmental programs49, which identified 91 fraud risks. It also:

- described the fraud risk and provided examples of potential sources of fraud as a result of the fraud risk;

- identified whether the fraud risk is an internal or external (or both) fraud risk;

- documented relevant policies and procedures applicable to the fraud risk;

- identified existing controls;

- rated the fraud risk on the basis of the likelihood of the risk occurring and the consequence;

- identified the risk owner;

- presented potential treatment option(s); and

- detailed who was consulted as part of the fraud risk assessment process. In total, 28 meetings were held with relevant areas across the department.

2.19 The 91 fraud risks identified in the 2017 fraud risk assessment have been summarised by DFAT into nine fraud risk domains and these risk domains are included in the fraud control plan.50

2.20 In 2019, the department reviewed51 the existing fraud risk assessment in relation to three of the nine fraud risk domains: finance systems; human resources processes; and corporate assets. These domains were selected due to the high number of ‘medium risks’ identified in the 2017 assessment. Overall the review assessed 48 of the 91 fraud risks identified in 2017 and covered seven business processes: 1) accounts payable; 2) accounts receivable; 3) vendor creation; 4) corporate credit cards; 5) procurement; 6) consular; and 7) information technology.The 2019 fraud risk assessment included consultation with departmental officials who undertake these business processes.

2.21 The risk assessment identified fraud risks across the seven business processes. It also described the risk; identified sources/causes; provided an initial risk rating; listed existing key controls; provided a residual risk rating; listed the fraud tolerance level based on the fraud risk domain; identified the risk owner; and provided additional comments/suggested treatment actions.

2.22 A further whole of department fraud risk assessment has been approved and is expected to be undertaken in August 2020. The department advised the ANAO that the overall approach is being developed and that it intends to finalise, by 30 June 2020, an approach to market to procure support services, subject to the operational impacts of COVID-19.

2.23 In addition to managing the 2017 fraud risk assessment and the 2019 fraud risk assessment review, the department’s Fraud Control Section prepares a Vulnerabilities and Treatments report52 for the Audit and Risk Committee and departmental executive. The first Vulnerabilities and Treatments report covered the period 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2018. Subsequent reports have been prepared twice yearly (covering a six-month period). The report highlights fraud vulnerabilities identified in the fraud risk assessments, including strategic and operational risks. The report collates data about suspected or known fraud and identifies areas where fraud may be under-reported. The report also identifies key themes across these areas of fraud risk and suggests ways to strengthen the department’s fraud control arrangements. Actions undertaken by the department to improve fraud control arrangements are included in subsequent reports.

2.24 To compile content for the Vulnerabilities and Treatments report, the Fraud Control Section liaises with two other business areas — internal fraud and passport fraud.53

2.25 The department’s fraud control section staff have appropriate qualifications in fraud control in line with the fraud guidance, or are awaiting training to be delivered.

Are fraud risks assessed and addressed?

Fraud risks are assessed and given a fraud risk exposure rating based on the likelihood and consequences of the risk occurring. Depending on the assessed exposure rating and having regard to the department’s tolerance level, these risks are then addressed with responses ranging from monitoring to actively treating the risk. Of the 91 fraud risks identified in the department’s 2017 fraud risk assessment, seven (7.7 per cent) were identified in internal reporting as ‘critical’ fraud risks. One additional ‘critical’ risk was identified in the department’s 2019 fraud risk assessment. The department took action to address these ‘critical’ fraud risks and reported on the actions taken to mitigate these risks to its Executive.

2.26 In order for entities to effectively respond to fraud risks it is important for the significance of the risks to be assessed and to determine whether treatments are required. The ANAO examined how the department assesses its risk exposure and identified the mechanisms the department uses to address fraud risks.

2.27 The department’s November 2017 fraud risk assessment identified 91 fraud risks and determined a fraud risk exposure rating for each risk on the basis of the likelihood of the risk occurring and the consequence if the risk occurred. Table 2.2 shows the department’s risk matrix used to determine the risk exposure rating for each fraud risk based on this assessment.

Table 2.2: Risk matrix of fraud risks to determine fraud risk exposure rating

|

|

Consequence of risk occurring |

|||||

|

Limited |

Minor |

Moderate |

Major |

Severe |

||

|

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

||

|

Likelihood of risk occurring |

Almost Certain |

Medium |

Medium |

High |

Very High |

Very High |

|

Likely |

Medium |

Medium |

High |

High |

Very High |

|

|

Possible |

Low |

Medium |

Medium |

High |

High |

|

|

Unlikely |

Low |

Low |

Medium |

Medium |

High |

|

|

Rare |

Low |

Low |

Low |

Medium |

Medium |

|

Note: DFAT’s risk matrix uses the term ‘very high’ to describe its highest fraud risk exposure, while the other entities in this audit series use the term ‘extreme’. The definitions are broadly equivalent.

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental documentation.

2.28 The assessment allocated a fraud risk exposure rating for each of the 91 fraud risks (Table 2.3).

Table 2.3: 2017 fraud risk assessment ratings after assessment

|

Fraud risk exposure ratings |

|

|

Very high risk |

0 |

|

High risk |

7 |

|

Medium risk |

60 |

|

Low risk |

24 |

|

Total |

91 |

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental documentation.

2.29 The seven fraud risks with a fraud risk exposure rating of ‘high’ were identified as ‘critical fraud risks’ within the department’s Vulnerabilities and Treatments report in June 2018, on the basis that they were ‘high’ risks. The report set out recommendations to address these critical fraud risks. The department considered that these risks reflected systemic issues and gaps that could be repeated through multiple programs. The report therefore recommended addressing these critical fraud risks ‘in a systematic way’ to ‘improve practices more broadly, with a treatment capable of remedying several risks’.

2.30 In 2019 the department undertook a further fraud risk assessment, focussed on six different business processes. This assessment identified 15 fraud risks all of which had a residual risk rating of ‘medium’ or ‘low’ after the application of treatments. Seven of the risks with a residual rating of ‘medium’ were assessed as being outside the department’s tolerance level. One new ‘critical risk’ was identified.

2.31 The ANAO viewed evidence that action was taken by the department to improve departmental practices to address the critical fraud risks and risks that were outside its tolerance level. These actions, which included progress towards implementing policies, frameworks and procedures, continued over 2018 and 2019. By the end of 2019 the department considered that these risks were no longer ‘critical’ as the risks had been addressed (see also paragraph 2.42).

2.32 The actions taken to address the ‘critical’ fraud risks were reported in the two Vulnerability and Treatments reports covering the period 1 July 2018 to 30 June 2019.

2.33 The department has in place a number of operational processes and activities to address identified and assessed fraud risks. These include:

- allocating a fraud risk owner to each identified fraud risk, who is responsible for managing and mitigating the fraud risk;

- a risk management guide for aid investments54 which includes better practice information for departmental staff to design and implement aid investments;

- assisting funding recipients to meet their contractual requirements to develop and implement fraud control strategies through the fraud control toolkit developed for funding recipients;

- considering fraud risks and detected incidences of fraud when developing the department’s internal audit work program; and

- conducting internal audits to provide assurance on whether the department’s controls contribute to the management of fraud risks.

Does the department’s internal control environment include preventive controls and are these adequately assessed?

The department has a range of preventive controls in place to prevent fraud and tests its controls to ensure they are operational. The department has undertaken control reviews and has mechanisms in place to provide assurance around its control environment. These mechanisms could be better supported by clear assignment of control owners, by position, in line with the department’s risk management guide.

2.34 Preventive controls can help entities to prevent fraud from occurring in the first place or to reduce the consequences when it occurs. The fraud guidance states that:

Controls and strategies outlined in fraud control plans are ideally commensurate with assessed fraud risks. Testing controls may indicate that not all controls and strategies are necessary or that different approaches may have more effective outcomes. Controls can often be reviewed on a regular basis to make sure they remain useful.55

2.35 The ANAO examined whether DFAT has documented preventive controls to manage its identified fraud risks and whether it has established mechanisms to assess and provide assurance over the control’s effectiveness. The ANAO did not test the design or operational effectiveness of individual controls.56

Preventive controls

2.36 The Australian Government’s Risk Management Policy defines an internal control as:

Any process, policy, device, practice or other actions within the internal environment of an organisation which modifies the likelihood or consequences of a risk.57

2.37 Broadly, there are two types of controls — preventive controls which are put in place to prevent fraud before it occurs, and detective controls which are put in place to identify when fraud has occurred (detective controls are discussed in chapter three).

2.38 The department’s fraud risk assessments (conducted in 2017 and 2019) identified groupings of existing controls against each of the fraud risks. These controls are largely preventive and reflect standard departmental business processes subject to testing and assurance.58

2.39 The department’s fraud control plan organises fraud controls into a matrix based on the nine fraud risk domains (discussed in paragraph 2.19). Fraud controls are divided between strategic controls (controls applicable to all Commonwealth entities such as Commonwealth legislation) and operational controls (controls specific to the department such as training requirements and internal policies).

Assessment of controls

2.40 The department’s Fraud Control Toolkit for Staff and Fraud Control Toolkit for Funding Recipients contain a list of possible controls that can be drawn upon by staff and funding recipients to treat identified fraud risks. Assessment of these controls is the responsibility of business areas.

2.41 The department’s Vulnerabilities and Treatments reports provide a mechanism to identify any potential enhancements to existing ‘critical’ controls following the receipt of an allegation of fraud. These reports detail the fraud risk and suggested improvements to existing controls, with the resulting actions and completion dates tracked. This approach is intended to ensure risks are within tolerance as soon as possible.

2.42 Key business processes considered in the 2019 fraud risk assessment have since been subject to control effectiveness reviews to examine the control environment for these business areas. The results of these reviews were reported in the December 2019 Vulnerabilities and Treatment report.

2.43 Operational areas across DFAT have put in place operational and program assurance frameworks. The Aid Governance Board approved a framework and further development for the Official Development Assistance program at the end of 2019. The first Vulnerabilities and Treatments report (June 2018) identified that a department-wide program assurance framework should be developed and implemented ‘to monitor compliance with the department’s contractual requirements, enhancing the department’s oversight.’ The department advised the ANAO that the intention of this whole of department framework is to look at the effectiveness and efficacy of controls, as well as clarifying individual accountability for the oversight of key controls. Development of a department-wide framework had not commenced as at March 2020.59

2.44 The department’s 2018 risk management guide60 states that each control ‘should have a control owner who is accountable for managing the control’. The guide also states that departmental controls should be assessed. Controls may be assessed as ‘effective’, ‘partially effective’ or ‘ineffective’. For a control to be ‘effective’ the guide requires that the control is assigned and ‘forms part of the officer(s) duty statement and/or performance agreement’. Controls may be ‘ineffective’ if ‘no specific officers have been identified to operate the control’.

2.45 Control owners were not listed for controls identified in both the 2017 and 2019 fraud risk assessments. Control owners in the department’s fraud control plan are listed as the branches and sections in the department which are responsible for the control, rather than an identified position or person in the department.

2.46 To assist the department to oversight its fraud controls at a business area level and at the whole of department level, responsibility for controls should be assigned by position, in line with internal guidance.

Recommendation no.1

2.47 The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s department-level fraud risk assessments identify control owners by position, in line with its risk management guide.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

3. Detection, investigation and response

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the department has complied with the mandatory requirements of the Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework as they relate to the detection, investigation and response to fraud and the extent to which these arrangements are consistent with the Australian Government’s fraud guidance.

Conclusion

The department has put in place controls to detect fraud, including reporting channels for use by staff and members of the public. The department’s fraud investigation procedures are largely consistent with the Australian Government Investigations Standards, with attention required to update some procedures.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has made one recommendation for the department to update its policy and procedures for fraud investigations so as to fully meet the Australian Government Investigations Standards.

3.1 Section 10 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Rule 2014 (the fraud rule) requires the accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity to take all reasonable measures to detect and deal with fraud.61 In order to detect and deal with fraud, entities must take active steps to find fraud when it occurs and investigate or otherwise respond to it.

3.2 The ANAO examined the department’s compliance with relevant mandatory requirements of the Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework and the extent to which arrangements are consistent with Resource Management Guide No. 201 — Preventing, detecting and dealing with fraud (the fraud guidance) to assess whether:

- detective controls are identified; and

- the department’s investigations procedures are consistent with the Australian Government Investigations Standards.

Are detective controls identified?

The department has processes for departmental staff and others (such as members of the public and funding recipients) to confidentially report allegations of fraud. The department’s main source of fraud detection is tip offs from within the department (for allegations of internal fraud) or from sources external to the department (for allegations of external fraud). The department has a publicly available procedure for handling Public Interest Disclosures.

The department also detects fraud through other detective controls. These include internal audits, data analytics and forensic examination.

3.3 Detective controls are used to manage fraud risks and find fraud. Detecting fraud in an entity can highlight any vulnerabilities in existing preventive controls.

3.4 Subsection 10(d) of the fraud rule requires entities to have ‘a process for officials of the entity and other persons to report suspected fraud confidentially’.62

3.5 The fraud guidance notes that reporting suspected fraud is a common means of detection, and therefore it is important for entities to appropriately publicise fraud reporting mechanisms. Under the fraud guidance entities should encourage and support reporting of suspected fraud through proper channels, and this can include measures to protect those making such reports from adverse consequences.63

3.6 The ANAO examined the controls the department has in place to detect fraud with reference to the requirements of the Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework.

Detective controls

3.7 The department has channels for suspected fraud to be reported by officials of the entity and others (such as the general public and funding recipients). These channels are advertised on the department’s website and for staff, on the intranet. These channels include:

- a fraud referral form64; and

- three fraud reporting email addresses (one each for external fraud, passport fraud and internal fraud).65

3.8 The department also includes information about reporting suspected fraud in its Fraud Control Toolkit for Staff Funding Recipients (available on its website) and Fraud Control Toolkit for Staff (available to all staff on its intranet).66

3.9 Public Interest Disclosures are allegations made by public officials (disclosers) under the Public Interest Disclosure Act 2013 to an authorised officer because they suspect wrongdoing within the Commonwealth public sector.67 The department has procedures for handling Public Interest Disclosures, including: protection for disclosers; roles and responsibilities; details of how to make a disclosure; procedures for supervisors and managers; procedures for authorised officers; procedures for investigators; confidentiality and record keeping; and monitoring and evaluation requirements.68

3.10 The department’s website states that all fraud allegations are handled in a confidential manner,69 and the privacy webpage states that the department must comply with the Australian Privacy Principles contained in the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth).70 The website further states that the department will only use and disclose personal information for the purpose for which it was collected unless it is reasonably necessary for enforcement activities conducted by or on behalf of an enforcement body.

3.11 The Australian Institute of Criminology’s (AIC) annual fraud questionnaire asks entities to identify the detection method for finalised fraud investigations using categories provided by the AIC. In its response to the 2018–19 questionnaire the department reported that its main source of fraud detection for internal fraud was via tip offs, with 100 per cent of investigations finalised in 2018–19 detected via tip offs internal to the department. For external fraud, 72 per cent of investigations finalised in 2018–19 were detected via tip offs external to the department.71

3.12 Other sources of fraud detection during 2018–19 for external fraud include72:

- information technology controls (10 per cent);

- law enforcement notification to entity (7 per cent);

- staff member detection (6 per cent);

- external audit (3 per cent);

- tip off within the department (0.5 per cent); and

- self-reporting/confession (0.5 per cent).

3.13 The department has in place other detective controls, including:

- internal audits — internal audit planning includes consideration of fraud risks, and internal audits have considered fraud arrangements including program fraud frameworks and fraud arrangements at posts;

- data analytics — for example, the department’s passport fraud unit uses data analytics to assess documentation provided by passport applicants; and

- forensic examination — for example, the department’s passport fraud unit operates controls such as facial recognition.

Are the department’s investigation procedures consistent with the Australian Government Investigations Standards?

The department’s investigation procedures are largely consistent with the Australian Government Investigations Standards. The department’s policy and procedures for conducting investigations of suspected internal fraud require updating.

3.14 Once fraud is detected it is necessary to take action. Taking action shows that incidences of suspected fraud are not only identified but are responded to. Any investigation undertaken needs to be handled in a manner that will gather evidence to allow for subsequent responses, including criminal prosecution.

3.15 The Commonwealth Fraud Control Policy (the fraud policy) requires entities to have investigation processes and procedures consistent with the Australian Government Investigations Standards (AGIS) (see details in Box 1).73

|

Box 1: The Australian Government Investigations Standards (AGIS) |

|

The AGIS establish the minimum standards for Australian Government agencies conducting investigations, and apply to all stages of an investigation. AGIS defines an investigation as:

AGIS lists standards the agency must have (mandatory), as well as standards the agency should have (not mandatory). The most recent review of the AGIS was in 2011 through a working group commissioned by the Heads of Commonwealth Operational Law Enforcement Agencies, chaired by the Australian Federal Police. The PGPA Act, and the Commonwealth Fraud Control Framework 2017 pursuant to the PGPA Act, are not referenced in the AGIS. The AGIS states that it is mandatory for all agencies required to comply with the Financial Management and Accountability Act 1997, legislation that has been replaced by the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act). |

Note: Australian Government, Australian Government Investigations Standards 2011 [Internet], Attorney-General’s Department, available from https://www.ag.gov.au/Integrity/counter-fraud/fraud-australia/Documents/ AGIS%202011.pdf [accessed 12 February 2020]. Following a machinery of government change in 2017, responsibility for the AGIS transferred to the Home Affairs portfolio.

Departmental requirements for external fraud investigations undertaken by funding recipients

3.16 The department requires funding recipients to prevent, detect and correct fraud in accordance with the obligations specified in their contract. In accordance with contractual arrangements, funding recipients must report any suspected fraud or incidents of fraud to the department within five business days, and to investigate the matter in accordance with the AGIS. The department provides guidance and written procedures to assist funding providers to conduct investigations. Under the contract, the department retains the right to conduct an investigation, along with the right to conduct an audit or review of the funding recipient’s compliance with its fraud control strategy and policies, including fraud prevention, reporting and investigation obligations.

3.17 The ANAO viewed evidence that the department is providing guidance to funding providers when they are conducting investigations. The department has procedures and a case management system to guide departmental monitoring of investigations being conducted by funding recipients. The ANAO reviewed the records retained in the case management system and found these records were complete, and included guidance from the department to funding providers about the conduct of investigations. The ANAO also saw evidence that the department uses this information to analyse trends, monitor and adjust the preventive control environment, track methods of fraud detection and report regularly to its executive and audit committee.

3.18 The department conducts due diligence checks of contractual arrangements and checks that the funding provider has the requisite fraud control arrangements in place.

3.19 There is evidence that the department has actively monitored the external fraud investigations brought to its attention. The department does not have a mechanism to assure itself that all funding recipients who are required to investigate a fraud matter are conducting investigations, or whether investigations are conducted in accordance with the AGIS (for example, whether the person undertaking the investigation holds the necessary qualification in accordance with the AGIS).74 In addition, as at March 2020 only two of the DFAT staff responsible for monitoring external fraud investigations met the minimum level of qualification to conduct investigations, with no staff holding the minimum qualification for staff primarily engaged in coordinating and supervising investigations.75

3.20 The ANAO examined whether the department’s investigation procedures for passport fraud and internal fraud investigations met the mandatory requirements listed in the AGIS (Table 3.1)

Table 3.1: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade investigation procedures and the AGIS mandatory requirements

|

AGIS requirement |

Passport fraud |

Internal fraud |

|

A clear written policy in regard to its investigative function |

✔ |

Out of date |

|

A procedure governing the manner in which complaints concerning the conduct of its investigations are handled |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Written procedures regarding liaison with the media and the release of media statements in regard to investigations |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Exhibit handling procedures |

✔ |

Out of date |

|

A written procedure covering the initial evaluation and actioning of each matter that has been received or identified |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Investigation management procedures |

✔ |

Out of date |

|

Written procedures relating to finalising the investigation |

✔ |

Out of date |

|

Investigator qualifications |

✔ |

✔ |

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental documentation.

3.21 Details of the ANAO’s assessment against the AGIS requirements are set out below — grouped as written procedures, case selection and referral, and investigation management. Departmental responses to the 2018–19 AIC fraud questionnaire are also included.76

AGIS requirements for written procedures

3.22 The department has a manual for departmental officials to assist them to carry out their duties as investigators of allegations of potential internal fraud. The manual is out-of-date and contains references to superseded legislation and Australian Government frameworks. Therefore this manual cannot be fully relied upon to assist investigators to perform their duties.77

3.23 There is scope for DFAT to update its policy and processes for fraud investigations to fully meet AGIS requirements.

Recommendation no.2

3.24 The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade update its policy and processes for fraud investigations to fully meet Australian Government Investigations Standards requirements.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Case selection and referral

3.25 The department has an up-to-date case prioritisation policy (dated January 2019) to assess and prioritise reports of misconduct by departmental employees (including potential cases of internal fraud). The factors taken into account when making a decision to investigate are detailed in the policy, and include:

- whether a formal investigation is required;

- the complexity and size of the potential case; and

- any risks and/or threats, and the seriousness of the potential case.

3.26 The department has procedures, including templates and an evaluation matrix, to assess cases of potential passport fraud. The assessment procedures include a decision on whether to proceed with a criminal or administrative investigation.

3.27 In its response to the 2018–19 AIC fraud questionnaire, the department reported that five internal fraud cases and 66 external fraud cases did not meet the threshold to warrant an investigation.78

3.28 The department has procedures for referring serious cases of fraud to law enforcement, including the Australian Federal Police and overseas agencies. In its response to the 2018–19 AIC fraud questionnaire the department identified that: 9 of the 10 internal fraud investigations finalised in 2018–19 were conducted solely by the department and one was conducted by a consultant investigator; and 105 of the 195 external fraud investigations were conducted by funding recipients, with the remaining 90 external fraud investigations conducted solely by the department.

Investigation management

3.29 As required by the AGIS, the department has procedures for the investigation of allegations of suspected passport fraud. These procedures cover all steps in the investigation management process from receiving an allegation through to finalising an investigation, and include preparing briefs of evidence for the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions.

3.30 The department has an electronic investigation management system for the investigation of allegations of suspected internal fraud, but does not have up-to-date procedures (see paragraph 3.22).

3.31 The ANAO reviewed records contained within the separate electronic investigation management systems established for passport fraud and internal fraud, and found records of all steps undertaken in an end-to-end investigation process.79

3.32 The department’s response to the AIC questionnaire reported that it commenced a total of 235 investigations during 2018–19, the majority of which were investigations of external fraud (Table 3.2).

Table 3.2: Number of investigations commenced in 2018–19

|

|

Internal fraud |

External frauda |

Fraud involving collusion between internal and external individuals |

|

Investigations commenced |

14 |

215 |

6 |

Note a: External fraud includes passport fraud and external fraud investigations.

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental documentation.

3.33 The department records the outcomes of investigations. In 2018–19, 50 per cent of internal fraud investigations and 43 per cent of external fraud investigations had allegations substantiated in full or in part (Table 3.3).

Table 3.3: Outcomes of investigations finalised in 2018–19

|

|

Internal fraud |

External frauda |

|

Allegation substantiated (in full or in part) |

5 |

83 |

|

All allegations not substantiated |

3 |

79 |

|

Allegation referred to another agency and outcome currently unknown |

2 |

0 |

|

Allegations substantiated but the funding owner is not DFATb |

0 |

33 |

|

Total |

10 |

195 |

Note a: External fraud includes passport fraud and external fraud investigations.

Note b: DFAT advised the ANAO that these are allegations of fraud where the fraud is substantiated, although the fraud has not been committed directly against DFAT. This will include pooled funds and funding being used by delivery partners to enter into agreements in the supply chain.

Source: ANAO analysis of departmental documentation.

3.34 For those investigations of internal fraud finalised in 2018–19, where allegations were substantiated (in full or in part), all received an administrative sanction. There was a range of results for investigations of external fraud where allegations were substantiated, the most common being referral to non-Australian law enforcement (Table 3.4).

Table 3.4: Result of investigations finalised in 2018–19 where allegations were substantiated (in full or in part)

|

|

Internal fraud |

External frauda |

|

No further action taken |

0 |

7 |

|

Matter referred to police or another agency |

0 |

6 |

|

Termination of employment or contract by dismissal |

0 |

13 |

|

Claim or benefit withdrawn or terminated |

0 |

2 |

|

Administrative sanctions |

5 |

5 |

|

Criminal court conviction outcomes |