Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Value for Money in the Delivery of Official Development Assistance through Facility Arrangements

Please direct enquiries through our contact page.

Audit snapshot

Why did we do this audit?

- Approximately 97 per cent of aid delivered on behalf of the Australian Government through facility contractors was delivered by the top four contractors.

- Effective and efficient delivery of aid by managing contractors is critical to achieving Australia’s aid policy and broader national interest objectives.

- Transparency about the purpose, results and costs of the aid program helps to maintain public confidence.

Key facts

- DFAT’s largest facility by value is the Papua New Guinea–Australia Governance Partnership.

- For the facilities in this audit, 14 to 21 per cent of expenditure is on administration.

What did we find?

- DFAT’s achievement of value for money in the delivery of aid through facilities is largely effective, with a need for greater focus on the collection, monitoring and analysis of aid administration costs.

- Facility design and contractor procurement processes are well structured.

- Partnering with managing contractors is effective, but DFAT does not appropriately monitor the ratio of administration costs to aid delivered in facilities.

- Suitable frameworks have been established for evaluating the performance of aid investments.

What did we recommend?

- The Auditor-General made three recommendations to DFAT. They relate to: planning processes; value for money assessments; and visibility of costs.

- DFAT agreed with the recommendations.

19%

of total aid delivered by top four suppliers

$750m

the value of DFAT’s largest facility

14–21%

of expenditure is on administration

353

Aid Quality Checks completed in 2018

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Australia’s Official Development Assistance (ODA) budget in 2019–20 is $4.044 billion. In 2018–19, expenditure on aid by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) made up 90.8 per cent of Australia’s total ODA spend (valued at $3.976 billion).1 DFAT’s ODA expenditure represented 65 per cent of the department’s total expenditure.

2. There has been an increase in the value of aid delivered through DFAT’s major suppliers. The value of aid delivered through DFAT’s top four suppliers over the period 2008–09 to 2018–19 moved from $236.4 million to $751.1 million, representing an increase in value from 7.8 per cent to 19 per cent of DFAT’s total aid spend.2

3. DFAT uses contracting arrangements, termed ‘facilities’, to deliver programs of work aimed at achieving broad developmental outcomes.3 A key capability expected of a managing contractor is the ability to develop and implement aid activities.

4. As at January 2020, DFAT managed 20 commercial facilities with a total approved value of $2.791 billion.4 Seventeen of these facilities were delivered by the top four providers and valued at $2.716 billion, representing approximately 97 per cent of the total approved value of facility contracts.

5. The Kemitraan Indonesia Australia untuk Infrastruktur (KIAT) facility in Indonesia and the Papua New Guinea–Australia Governance Facility (PAGP) are two of the largest facilities managed by DFAT.

- The KIAT infrastructure facility commenced in 2017, with an expected expenditure of approximately $300 million over 10 years. KIAT aims to assist the Government of Indonesia to improve social and economic infrastructure.

- The PAGP was established in April 2016. The facility is valued at approximately $750 million over six years. It delivers the majority of Australia’s bilateral governance initiatives in Papua New Guinea.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

6. Facility contractors are delivering $2.8 billion in aid on behalf of Australia over the life of 20 major investments. Effective implementation of Australia’s aid program supports the Australian Government’s long-term policy objectives. Transparency about the purpose, results and costs of these investments, and value for money achieved, helps to maintain confidence that they represent a proper use of public resources.

Audit objective and criteria

7. The audit objective was to examine DFAT’s achievement of value for money objectives in the delivery of Official Development Assistance (aid) through facility arrangements. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Does DFAT’s design of frameworks for the delivery of aid through facilities support value for money objectives?

- Does DFAT’s implementation of facility arrangements support efficiency and effectiveness in the delivery of aid?

- Does DFAT appropriately evaluate and report on value for money achieved through facility arrangements?

Conclusion

8. DFAT’s achievement of value for money in the delivery of aid through facilities is largely effective, with a need for greater focus on the collection, monitoring and analysis of aid administration costs.

9. DFAT’s processes for the design and procurement of facilities are largely effective. Improvements have been made to arrangements for reviewing facility investment designs since the establishment of the KIAT and PAGP facilities in the period 2014–2016, reflecting increased contestability and risk awareness. Design processes do not, however, include appropriate consideration of facility administration costs as part of the formal assessment of value for money. Procurement processes for KIAT and PAGP were conducted in accordance with Commonwealth Procurement Rules and were effective in establishing fit-for-purpose contractual arrangements.

10. DFAT’s implementation of the KIAT and PAGP facility arrangements are partially effective in supporting value for money in the delivery of aid. Arrangements for collaborative partnering and high-level decision-making have been established, but supply chain risks are not being appropriately monitored in all instances. DFAT does not effectively analyse facility financial data at an aggregate level to determine whether administration costs are proportionate to the value of aid delivered and is therefore unable to determine whether the KIAT and PGF are realising overall expected efficiencies.

11. DFAT has effective frameworks for evaluating and reporting whether aid investments are achieving their intended purpose. There are suitable frameworks and processes in place for assessing progress in the implementation of investments and contractor performance, but there is scope to improve the transparency of evaluation and reporting on the performance of facility arrangements.

Supporting findings

Design

12. DFAT’s design of aid delivery through facilities largely supports the achievement of value for money objectives. Design processes followed the department’s investment planning requirements, but did not include appropriate consideration of cost baselines and savings projections, or information about the proportion of aid funding to be allocated to administration costs. Since 2017, improvements to the oversight of investment proposals have contributed to increased contestability and awareness of risk.

13. DFAT’s procurement of managing contractors for the KIAT and PAGP facilities was consistent with policy requirements and supported the achievement of value for money. Approaches to market maximised competition, tender evaluation processes appropriately considered provider capacity and price, and fit-for-purpose contractual arrangements were established.

Implementation

14. Governance arrangements for the KIAT facility and PAGP are largely effective in supporting the achievement of value for money. DFAT has established appropriate structures for decision-making and coordination with the respective managing contractors. There is inconsistent evidence that value for money assessments are being conducted for individual aid activities developed under the PAGP, and inconsistent compliance with requirements for the monitoring of risk in facility supply chains.

15. DFAT’s implementation of processes for monitoring and analysing facility costs are partly effective. DFAT does not routinely monitor administration costs for the purposes of analysing costs across facilities, and is therefore unable to determine whether the KIAT and PAGP are realising expected efficiencies. Audit analysis indicates that the costs associated with establishing and operating each of the two facilities are tracking higher than budgeted as a proportion of expenditure on aid activity.

Evaluation

16. DFAT has suitable frameworks for evaluating the performance of aid investments such as facilities. These are effective in supporting internal and public reporting on DFAT’s performance in achieving the results expected by government. There are opportunities for improvement in relation to the collection of data against a standard set of quantitative efficiency indicators.

17. DFAT’s reporting on the achievement of value for money in the delivery of aid through facility arrangements is largely transparent in the detail of its reporting on individual aid investments. Performance reporting on contractors occurs only at the aggregate level. Transparency would be enhanced through increased reporting on the Government’s spend on the non-aid component of facility contracts.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 2.30

That DFAT planning processes for the design of facilities include consideration of facility administration costs as part of the formal assessment of value for money.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 3.30

That DFAT ensures that the assessment of individual aid activities under a facility are subject to appropriate value for money assessment and approvals processes.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Recommendation no.3

Paragraph 3.72

That DFAT establishes processes to enable visibility, monitoring and analysis of facility administration and supply chain costs.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Summary of the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response

18. DFAT’s summary response is provided below. The department’s full response can be found at Appendix 1.

The Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) welcomes the report, which followed an internal DFAT review of the operation of facilities conducted in 2017–18. We welcome the findings that Facility design and contractor procurement processes are well structured, partnering with managing contractors is effective and suitable frameworks have been established for evaluating the performance of aid investments.

DFAT is committed to continuous improvement as part of our strategy to deliver an effective and efficient development assistance program. We accept the audit report observations and recommendations regarding a broader consideration of costs during planning, improved value for money approval processes within facility structures and managing risks associated with supply chain management.

Key messages from this audit for all Australian Government entities

Below is a summary of key messages, including instances of good practice, which have been identified in this audit and may be relevant for the operations of other Australian Government entities.

Policy and program design

Procurement

Performance and impact measurement

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Australia’s Official Development Assistance (ODA) budget in 2019–20 is $4.044 billion.5 In 2018–19 expenditure on aid by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) was valued at $3.976 billion and made up 90.8 per cent of Australia’s total ODA spend. DFAT’s ODA expenditure represented 65 per cent of the department’s total expenditure.

1.2 The objective of the Australian aid program is to ‘promote Australia’s national interests through contributing to sustainable economic growth and poverty reduction.’6 DFAT’s annual Performance of Australian Aid report assesses the department’s management of the aid program against a performance framework, which includes 10 strategic targets.7 The eighth target requires a high standard of value for money to be achieved in at least 85 per cent of aid investments.8

1.3 DFAT and the Australian Agency for International Development (AusAid) merged on 1 November 2013.9 Responsibility for managing the aid program within DFAT now lies with policy, administration and contracting areas across the department. DFAT’s overseas missions (referred to as ‘posts’) have primary responsibility for implementing aid program activities.10

Definitions of value for money

1.4 DFAT is a non-corporate Commonwealth entity under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act). Under the Act, the accountable authority of a Commonwealth entity must promote the proper use and management of public resources. Proper means efficient, effective, economical and ethical use of resources.11 The Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) set out requirements for achieving value for money in the purchasing of goods and services by Commonwealth officials.12

1.5 In 2014, DFAT introduced eight principles to make explicit how value for money should be understood in the context of the aid program (see Table 1.1).13 These are referenced in DFAT guidance for managing the aid program, including for: strategic planning; procurement; program administration; and monitoring, evaluation and reporting.

Table 1.1: DFAT’s value for money principles

|

Economy |

Efficiency |

Effectiveness |

Ethics |

|

Cost consciousness |

Evidence based decision-making |

Performance and risk management |

Accountability and transparency |

|

Encouraging competition |

Proportionality |

Results focus |

|

|

|

|

Experimentation and innovation |

|

Source: DFAT value for money principles.14

Delivery of aid through contractors

1.6 Over the decade to 2019, the Australian Government has sought to consolidate the number of individual investments under the aid program.15 Consistent with Australia’s commitment to implementing the 2008 OECD Accra Agenda for Action, consolidation is aimed at improving value for money by reducing fragmentation in funding and improving policy coherence.16 There are now fewer, larger programs of activity of higher value — between 2013 and 2016 the number of aid investments managed by DFAT fell by 23 per cent, and the average value of investments increased by 26 per cent.

1.7 There has been an increase in DFAT’s use of major suppliers for the delivery of aid over the past decade, and in the value of aid delivered through these suppliers. The value of aid delivered through DFAT’s top four suppliers over the period 2008–09 to 2018–19 moved from $236.4 million to $751.5 million, representing an increase in value from 7.8 per cent to 19 per cent of DFAT’s total aid spend.17 In 2018–19, the top 10 suppliers delivered 95.5 per cent of DFAT’s contracted work by total approved value.

Facilities

1.8 DFAT uses facilities, managed by an external contractor, to deliver programs of work aimed at achieving broad developmental outcomes.18 A key capability expected of a managing contractor is the ability to develop and implement aid activities.

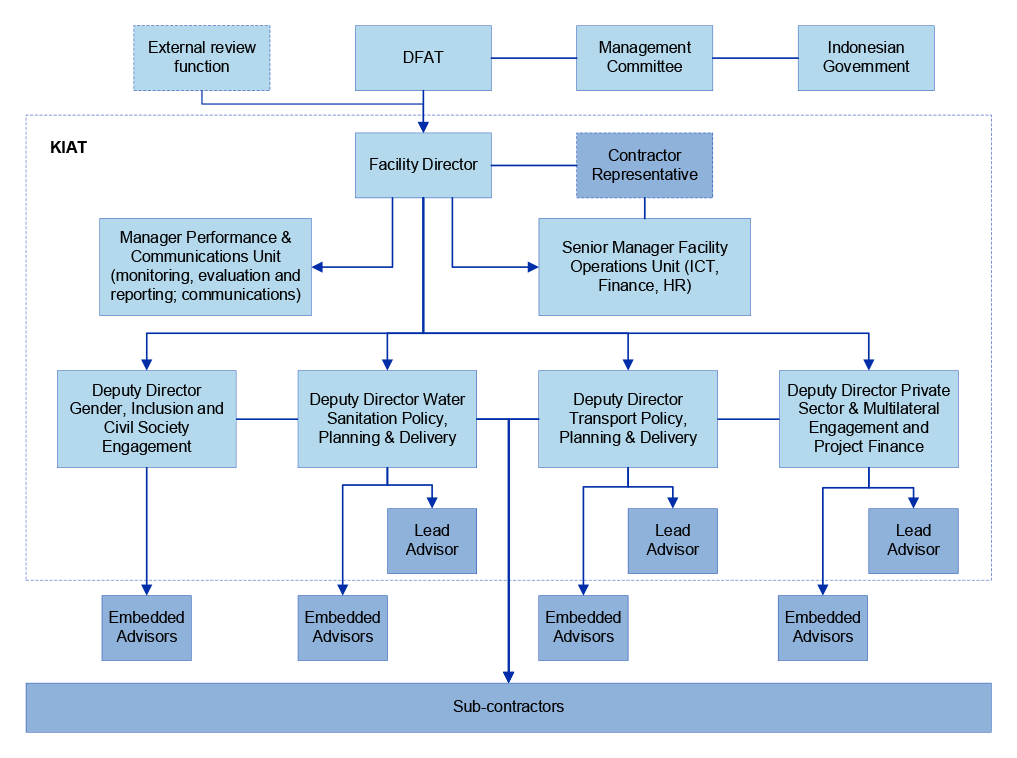

1.9 The general structure of a facility comprises a services platform and program implementing arms (see Figure 1.1). The platform supports the operation of the facility through corporate services19, with program lead areas managing the implementation of aid activities. Program areas are responsible for the development of aid proposals and engagement with DFAT and partner government stakeholders on these. This may involve establishing and managing a network of technical advisers embedded in partner government entities.

Figure 1.1: General facility structure

Note: There are some differences in the structure of the PNG–Australia Governance Partnership. See Appendix 6.

Source: ANAO analysis of data provided by DFAT.

1.10 A facility allows aid activities to be developed on an ongoing basis during implementation, with funding allocated annually. Facility operations can be scaled in response to policy and funding decisions made by the Australian or partner government. Annual work plans are used to determine a program of activities and associated budgets. DFAT describes the main benefits of the facility model as: greater policy coherence and coordination in implementation; and increased operating efficiency arising from economies of scale.

1.11 As at January 2020, DFAT managed 20 commercial facilities with a total approved value of $2.791 billion. Seventeen of these facilities were delivered by the top four providers and valued at $2.716 billion, representing approximately 97 per cent of the total approved value of facility contracts.

1.12 This audit has examined DFAT’s achievement of value for money through the use of two development facilities, the Kemitraan Indonesia Australia untuk Infrastruktur (KIAT) facility in Indonesia and the Papua New Guinea–Australia Governance Partnership (PAGP).

KIAT facility

1.13 The KIAT infrastructure facility commenced in 2017.20 It was expected that annual aid expenditure would be around $30 million on average (the total possible value under the agreement is $300 million over 10 years).21 The KIAT facility also manages four grants programs funded separately to the KIAT aid program budget.22 These grants are valued at up to $76 million over the life of the facility. Actual total spend on the facility as at 30 June 2019 was $39.7 million (approximately $20 million per year), plus an additional $18.7 million on the four grant programs. A timeline of the development and implementation of the facility is provided at Appendix 2.

1.14 KIAT aims to assist the Government of Indonesia to support sustainable and inclusive economic growth through improved access to infrastructure. It has three intended outcomes:

- Improved policies and regulations for infrastructure development.

- High-quality projects prepared for financing by the Government of Indonesia, multilateral development banks or the private sector.

- High-quality infrastructure delivery, management and maintenance by the Government of Indonesia.

Detail about KIAT objectives and work streams is provided at Appendix 3.

1.15 As of 31 July 2019, the KIAT facility had 48 contracted staff. Of these, 43 positions are located in the facility and five are attached to Government of Indonesia agencies. Development assistance activities include: the provision of technical assistance; the design of activities; feasibility studies; project management; engineering designs; capacity building; and training.

1.16 The managing contractor for KIAT is Cardno Emerging Markets (CEMA, Australia), which is a wholly owned subsidiary of Cardno Limited.23 As at January 2020, Cardno’s 33 contracts with DFAT had a total approved value of approximately $1.3 billion. Almost one third of its programs are delivered in Indonesia.24

Papua New Guinea–Australia Governance Partnership

1.17 The PAGP was established in April 2016.25 A timeline of the development and implementation of the facility is at Appendix 4.

1.18 The facility delivers the majority of Australia’s bilateral governance initiatives in PNG. Key areas of cooperation are delivered through six streams of work:

- Economic Governance and Inclusive Growth;

- Public Sector Leadership and Reform;

- Decentralisation and Citizen Participation;

- development assistance to the Autonomous Region of Bougainville;

- the Kokoda Initiative; and

- the PNG Partnership Fund — health and education grants.

Detail about the activities of the PAGP is provided at Appendix 3.

1.19 The implementation of PAGP activities is supported by a corporate services unit, which provides: contracting; human resource and financial management; legal; and other services. Just over a quarter of PAGP staff (91 of 332 contracted positions) are located in this unit.

1.20 The facility commenced in 2016 with funding of up to $390 million for an initial four years, with an option to extend the contract for an additional four years to 2024. Funding was increased to $480 million in 2017 to enable the delivery of health and education grants.26 Following a two-year contract extension to 2022, the upper limit of spending over the life of the facility is $750 million.27

1.21 At 30 June 2019, the PAGP had expended $342 million since its establishment. Expenditure under the PAGP during 2018–19 was $125.5 million, which represented approximately 22 per cent of Australia’s total bilateral aid expenditure to PNG for that year.28

1.22 The managing contractor for the PAGP is Abt Associates Australia (Abt), a company specialising in health, social and environmental policy and international development. As at January 2020, Abt held 52 contracts with DFAT with a total approved value of around $1.6 billion. Seventy per cent of programs delivered by Abt are in PNG.29

1.23 Timelines showing key stages in the development and implementation of the KIAT and PAGP facilities are at Appendices 2 and 4.

Rationale for undertaking the audit

1.24 Facility contractors are delivering $2.8 billion in aid on behalf of Australia over the life of 20 major investments. Effective implementation of Australia’s aid program supports the Australian Government’s long-term policy objectives. Transparency about the purpose, results and costs of these investments, and value for money achieved, helps to maintain confidence that they represent a proper use of public resources.

Audit objective and criteria

1.25 The audit objective was to examine DFAT’s achievement of value for money objectives in the delivery of Official Development Assistance (aid) through facility arrangements. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria.

- Does DFAT’s design of frameworks for the delivery of aid through facilities support value for money objectives?

- Does DFAT’s implementation of facility arrangements support efficiency and effectiveness in the delivery of aid?

- Does DFAT appropriately evaluate and report on value for money achieved through facility arrangements?

Audit methodology

1.26 This audit applied the ANAO’s methodology for auditing value for money, consistent with the PGPA Act. This involves relating principles of effectiveness, efficiency and economy in an overall assessment of value for money, which has regard to the Government’s purpose. The principle of effectiveness relates to the extent to which the intended objectives of public expenditure have been achieved. Efficiency has been assessed with reference to whether DFAT optimises its use of resources in delivering the intended quantity, quality and timing of outputs. Economy is understood as the principle of minimising costs, with regard to requirements of timeliness and the quantity and quality of inputs.30

1.27 The audit team undertook the following activities:

- selected two facilities as case studies by identifying the highest value facility in PNG and Indonesia respectively, taking into consideration sector (governance and infrastructure) and suppliers (first and second ranked in terms of total approved value of contracted work)31;

- examined documentation and data held by the department relating to the facilities and the broader aid program and reviewed public submissions to the ANAO; and

- conducted field visits to DFAT posts in Jakarta and Port Moresby to interview departmental and managing contractor staff and to review documentation and data held at post. The audit team also interviewed departmental staff and other stakeholders in Canberra.

1.28 The audit was conducted in accordance with the ANAO auditing standards at a cost to the ANAO of $612,126.

1.29 The team members for this audit were Judy Lachele, Nathan Callaway, Yvonne Buresch, Dr Cristiana Linthwaite-Gibbins and Paul Bryant.

2. Design of facilities

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the department’s design and procurement of facilities supported value for money objectives, using the KIAT facility and the Papua New Guinea–Australia Governance Partnership (PAGP) as case studies.

Conclusion

DFAT’s processes for the design and procurement of facilities are largely effective. Improvements have been made to arrangements for reviewing facility investment designs since the establishment of the KIAT and PAGP facilities in the period 2014–2016, reflecting increased contestability and risk awareness. Design processes do not, however, include appropriate consideration of facility administration costs as part of the formal assessment of value for money. Procurement processes for KIAT and PAGP were conducted in accordance with Commonwealth Procurement Rules and were effective in establishing fit-for-purpose contractual arrangements.

Area for improvement

The ANAO made one recommendation that the design of facilities include consideration of facility operating costs as part of the formal assessment of value for money.

2.1 An effective design process clarifies the purpose and expected results of an investment and determines how value for money can be best achieved and measured over its lifespan. In order to examine this criterion, the audit reviewed DFAT’s frameworks for establishing facility investments, with reference to the design and procurement of the KIAT and the PAGP facilities. This encompassed the review of:

- processes for the design of aid delivered through facilities — including DFAT’s consideration of the Government’s priorities; use of cost and risk analyses; and the operation of oversight mechanisms; and

- processes and practices for procuring facility managing contractors — as the selection of an effective delivery partner has a major influence on the achievement of value for money over the life of an investment.

Does DFAT’s design of aid delivery through facilities support the achievement of value for money objectives?

DFAT’s design of aid delivery through facilities largely supports the achievement of value for money objectives. Design processes followed the department’s investment planning requirements, but did not include appropriate consideration of cost baselines and savings projections, or information about the proportion of aid funding to be allocated to administration costs. Since 2017, improvements to the oversight of investment proposals have contributed to increased contestability and awareness of risk.

Planning of aid delivery

2.2 DFAT’s Aid Programming Guide governs the process for the development of new aid investments. Investment designs are required to set out the policy rationale and intended outcomes of a proposal, as well as broad options for implementation. These form the basis of consultation with partner governments, approvals for the commitment of funds, and subsequent procurement.

2.3 For investments over $10 million, the design process involves the development of an initial, high-level proposal (Investment Concept Note). Following approval by the delegate, a detailed design (Investment Design Document) is developed.32 This informs the development of a Request for Tender (RFT).

2.4 Criteria for the design of proposals are set out in DFAT guidance. Key ‘quality criteria’ are:

- relevance to government policy priorities;

- effectiveness — how the strategy will address priorities and deliver measurable and achievable outcomes; and

- efficiency — whether the proposal will make appropriate use of resources and time. Efficiency is defined in terms of costed inputs and outputs, with alternative models of delivery evaluated.33

2.5 The alignment of a proposal with government priorities is informed by four-year Aid Investment Plans (AIPs), which are agreed with partner governments and set out high-level objectives for country and regional programs.34 The plans aim to link aid objectives, aid programming and intended results.

2.6 The design of high-value or high risk (or a combination of both) proposals involves external and peer review processes.35 Proposals are provided to an oversight body — the Aid Governance Board (AGB) — for endorsement at the Investment Concept Design stage.

Design of the KIAT and PAGP facilities

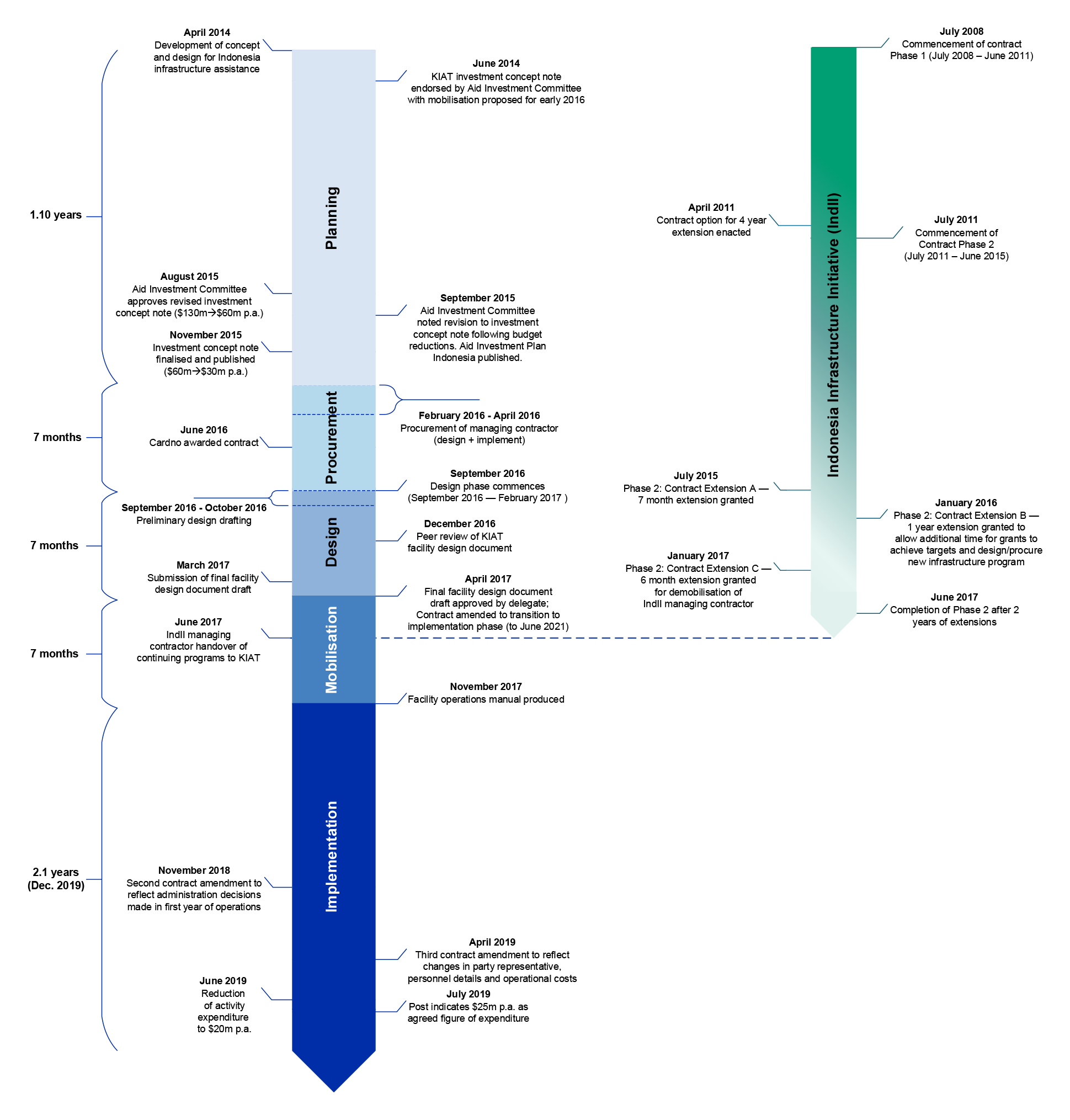

2.7 Activities for the design of the KIAT were undertaken from April 2014 to February 2017. The PAGP was designed between March 2012 and July 2015. Appendices 2 and 4 provide timelines for these design processes. Both proposals were reviewed and endorsed by the Aid Investment Committee (AIC), the principal DFAT governance body responsible for overseeing funding proposals at the time. The AIC was replaced by the AGB in December 2017 (discussed at paragraphs 2.18 to 2.34 below).

KIAT

2.8 The KIAT facility succeeded an established facility, the Indonesia Infrastructure Initiative (IndII)36, largely maintaining its focus on infrastructure development and the facility mode of delivery. The Investment Concept Note finalised in November 2015 outlined Australia’s bilateral policy objectives, which aligned with the AIP for Indonesia published two months earlier. The AIP signalled a shift in emphasis from the direct funding of infrastructure to influencing policy and regulation, recognising Indonesia’s increased capacity to fund capital works.

2.9 Agreed bilateral priorities were reflected in the KIAT design through the following changes from the existing IndII facility:

- a shift in focus from grants-based aid to targeted technical assistance;

- a reduction in funding from a planned $130 million to $30 million per annum, with an increased emphasis on leveraging Indonesian public and private resources37; and

- linking aid investments more closely with Australia’s trade objectives.

2.10 DFAT’s decision to use the facility model for KIAT was informed by evaluations undertaken of the previous infrastructure program and feedback on the existing facility from the Indonesian Government.38 A facility was considered to provide greater transactional efficiency and program coherence compared to a number of stand-alone investments. DFAT’s design and associated approval process did not, however, include an explicit cost and benefit comparison of alternate delivery mechanisms.39

2.11 Some process efficiencies identified in an ANAO audit and evaluations of the IndII facility40 were addressed in the final design. This included streamlining processes for the approval of aid activities developed under the facility to reduce administration and costs to DFAT and the managing contractor. KIAT’s activity development process is discussed further at paragraphs 3.24 to 3.27.

PAGP

2.12 In October 2014, the AIC endorsed the PAGP Investment Concept Note. The PAGP design process established the policy rationale and business case for the use of the facility mode of delivery. The proposal was aimed at delivering greater development impact than had been achieved through a number of extant governance programs due to end in December 2015.

2.13 The PAGP design reflected the Government’s policy of reducing direct service delivery through the aid program and supporting economic development. It aligned with the intent of a ministerial agreement concluded in December 2013 to expand Australia’s support for governance in PNG through activities directed at:

- expanding support for good governance (delivered primarily via the Strongim Gavman Program)41;

- strengthening anti-corruption and security efforts;

- professionalising the public service;

- improving accountability and leadership;

- undertaking critical economic reforms; and

- meeting the basic needs of the population.42

2.14 A facility model and two alternative models were considered:

- partial consolidation — integration of individual projects into a smaller number (8–10); or

- consolidation into three mini-facilities, each with 8–10 smaller initiatives, designed and contracted separately.

2.15 The facility model was assessed as the most appropriate implementation mechanism for ensuring aid activities were strategically aligned, coordinated and responsive to changing priorities. It was anticipated that a flexible and iterative design function would enable lessons learnt to be applied throughout implementation. The facility model was determined to offer the greatest scope for achieving administrative efficiency. An anticipated reduction in staffing at post (estimated at 20 per cent), and hence capacity to manage multiple stand-alone investments, was a key consideration.43

2.16 DFAT estimated that the facility model would lead to overall savings of approximately 25 per cent compared with existing arrangements. This included one-off savings (for example, through the consolidation of office costs) and on-going savings (for example, as a result of reduced design, tendering and contracting costs). Estimates of potential savings were not prepared for the other two options.

2.17 Cost savings identified for the facility model were not assessed with reference to costs associated with operating a facility. Without an understanding of these costs, the net saving likely to be achieved cannot be determined. This reduced the capacity of decision-makers to assess the proposal’s overall proposition for achieving value for money.44

Oversight arrangements

2.18 An internal 2017 review, (the ‘Aid Operations Health Check’) concluded that the AIC’s oversight of aid program risks was not effective. The main reasons for this were:

- active avoidance of AIC scrutiny by proponents of proposed investments by undervaluing investments or understating risk;

- large and unstable committee membership and infrequent meetings;

- a lack of portfolio view; and

- oversight not extending to the implementation of investments.

2.19 The AGB replaced the AIC in December 2017. The AGB is chaired by a Deputy Secretary and members include the Chief Economist (Development), the Chief Financial Officer and Senior Executives of policy and contracting divisions. Unlike the AIC, the AGB has an independent member. Members are expected to apply a whole of department perspective in exercising their responsibilities rather than acting as representatives of their Group.

2.20 The AGB’s primary purpose is to act as an advisory body to the Secretary; the departmental executive; and delegates under the PGPA Act. Its stated aims are to increase strategic clarity and strengthen governance, including risk management of the aid program.

2.21 In addition to broader functions associated with providing advice on the aid program, the AGB advises delegates on designs for investments that have a value of $100 million or more, are rated ‘high risk’, or are a facility. The AGB can also elect to consider investments developed under time pressure or those that have highly ambitious or innovative objectives. It may request to review investments during implementation.

2.22 A technical unit, the Quality and Risk Advisory Unit (QRAU) overseen by the First Assistant Secretary of Contracting and Aid Management Division, appraises all proposals submitted to the AGB. Its primary role is to advise the AGB and delegates on the quality of concepts and designs. QRAU appraisals aim to assess the extent to which proposals:

- have clear objectives and align with strategic priorities and are likely to bring substantial benefits and impacts;

- are informed by evidence of the country, regional, and sector context, as well as relevant DFAT and international expertise;

- have clear and effective management and governance arrangements, and feasible implementation plans;

- have arrangements to manage risk; and

- have clear and effective arrangements for monitoring and evaluating progress.

2.23 This audit reviewed documentation relating to new facility proposals considered by the AGB since its inception (refer to Table 2.1) to assess whether intended improvements in the higher-level oversight of facilities are evident.45

Table 2.1: Facility proposals reviewed by the Aid Governance Board from April 2017 to May 2019

|

Facility proposal |

Date reviewed by AGB |

|

Indonesia Governance for Growth (KOMPAK — contract extension) |

11 April 2017 |

|

Pacific Labour Mobility Facility |

22 June 2018 |

|

Australia–PNG Health Program Managing Contractor (PNG-AUS Transition to Health (PATH) Program) |

23 August 2018 |

|

PNG–Australia Program for Improved Performance in Education |

4 October 2018 |

|

Southeast Asia Economic Governance and Infrastructure Facility (Phase 1) |

6 December 2018 |

|

PNG–Australia Governance Partnership (next steps — contract extension) |

20 April 2019 |

|

Australia Infrastructure Financing Facility for the Pacific |

31 May 2019 |

Source: ANAO analysis of data provided by DFAT.

Objectives

2.24 The design process generally established a clear line of sight between proposed activities, delivery mechanisms and the intended outcomes of the investment. Clarification of objectives and intended impact was requested by either the AGB or QRAU for four of the seven proposals, and further information on how proposed activities would result in the expected development impact was requested for two proposals. DFAT advised in March 2020 that actions relating to these investments have been completed.

Costs

2.25 DFAT guidance states that delegates must understand the costs and impacts of their spending decisions, as well as the risks involved. The funding for an individual proposal is set through the department’s annual budget processes. In order to assess value for money, the delegate requires information about how the proposed scope of an activity and its delivery mechanism represents the best use of resources.

2.26 The investment documents for each proposal reviewed did not clearly link the expected quantity and quality of aid delivery to the funding available. Value for money was systematically assessed for one of the seven proposals examined; the PNG–Australia Governance Partnership (next steps — contract extension). The need to achieve value for money was referenced in a further three proposals.

2.27 Only limited information about anticipated indirect delivery costs as a component of the overall budget was presented in proposals.46 Delivery options and associated costs are not examined as a standard component of QRAU assessments. Such costs are relevant to understanding the amount of program funding likely to be available for direct aid activities.

2.28 Proposals generally did not assess DFAT staffing requirements. The QRAU has noted a continuing tendency across the department to select the facility modality as the most efficient mechanism for delivering programs given staffing constraints, without sufficient consideration of potential consequences for effectiveness.

2.29 The Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs) state that when a business requirement arises, it is important to take into consideration the market’s capacity to competitively respond to a procurement.47 This perspective was evident in two of the seven proposals.

Recommendation no.1

2.30 That DFAT planning processes for the design of facilities include consideration of facility administration costs as part of a formal assessment of value for money.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed, noting that at design stage facility administration cost will only be an estimate, with costs finalised through the tender process and contract negotiations.

Risks

2.31 The involvement of independent members48 and the use of technical assessments have contributed to increased visibility and testing of risks associated with individual proposals. More broadly, the AGB is overseeing work to strengthen management of aid program risks.

2.32 Reporting to the AGB in June 2019 stated that DFAT has ‘no system for capturing and reporting on aid program risks in a consolidated form’. Risk information contained in AidWorks, the department’s system for managing aid investments, is incomplete. The system cannot be used therefore to identify high-risk investments.49

2.33 Proposed work to address weaknesses in DFAT’s management of risk identified by the 2017 Aid Operations Health Check included:

- risk planning and oversight of the top 15 aid investments by value;

- development of risk appetite statements for the aid program;

- aid risk updates to be provided every six months; and

- a broader assurance framework and systems capability to address non-compliance with DFAT policies and procedures.

2.34 In late 2019, DFAT identified 15 aid investments for oversight by the AGB on the basis of key risk criteria. These criteria included: either being a facility and/or of high value; delivered in high-risk countries; having a high safeguard risk; and having been assessed as an investment requiring improvement.50 The first risk report was to be provided to the AGB in March 2020.

Do DFAT’s processes and practices for procuring facility managing contractors support the achievement of value for money in the development of aid programs?

DFAT’s procurement of managing contractors for the KIAT and PAGP facilities was consistent with policy requirements and supported the achievement of value for money. Approaches to market maximised competition, tender evaluation processes appropriately considered provider capacity and price, and fit-for-purpose contractual arrangements were established.

2.35 The CPRs require procurement activities to deliver a value for money outcome. This is achieved when procurements:

- encourage competition and are non-discriminatory;

- use public resources in an efficient, effective, economical and ethical manner;

- facilitate accountable and transparent decision-making;

- encourage appropriate engagement with risk; and

- are commensurate with the scale and scope of the business requirement.51

Procurement approach

KIAT

2.36 The procurement process for the KIAT facility commenced with an open tender in February 2016.52 The tender sought the provision of both design and implementation services for the facility.53 This approach differed from DFAT’s more commonly used procurement strategy of tendering for design and implementation services separately and sequentially. Engagement for the implementation phase was not guaranteed to the provider of design services — it was to be at DFAT’s discretion whether to exercise the implementation option following the design phase.

2.37 The procurement approach was aimed at minimising the time between the completion of the design and the start of implementation, as DFAT would not be required to undertake a separate procurement for implementation services.54 DFAT also saw benefit in the contractor responsible for consulting with key stakeholders in the design of the facility carrying these relationships forward into the implementation phase. However, the scheduled timing of the KIAT procurement would not have allowed DFAT to return to market for the implementation phase without disrupting activities that were to be continued from the IndII facility.55 This reduced the scope for benefits of an option to not proceed to implementation.

2.38 DFAT ensured that the market received appropriate information about its objectives for the procurement.56 Of the 11 companies that attended the industry briefing, four submitted bids.

PAGP

2.39 The open tender process to engage a managing contractor for the PAGP commenced in August 2015 with the release of the PAGP Design Document and RFT to the market.

2.40 The PAGP design detailed DFAT’s expectations that the managing contractor would be responsible for the development and implementation of most of Australia’s governance related program activities in Papua New Guinea.57 The draft deed of standing offer outlined a requirement to establish four broad programs of work. The transition of a large number of lapsing agreements and their alignment with a yet to be developed governance strategy was to be determined during a six month inception period.

2.41 DFAT recognised a key risk was that the procurement would not secure the most able supplier for delivering the substantial scope of work, particularly as DFAT would be locked into an arrangement for several years. To mitigate the risk, DFAT engaged with industry at an early stage, providing comprehensive information.58 Fourteen organisations attended DFAT’s industry briefing resulting in four tender submissions. All were consortia ranging from two through to eight organisations, led by four of DFAT’s top five suppliers in 2015–16.

Tender evaluation

KIAT

2.42 An Evaluation Committee (EC) was established in March 2016 to assess the tender submissions for the KIAT facility. The EC’s Evaluation Plan set out four key criteria for evaluating value for money: technical; operations; financial and commercial; and risk.

- The technical assessment was based on three areas: the bidding organisation59 (weighting 20 per cent); the bidder’s proposed approach to delivering the tender requirements (40 per cent); and proposed personnel (40 per cent). Each proposal was given a technical score out of 10. Cardno was ranked first on this assessment.

- The financial and commercial assessment was conducted on each bidder’s proposed costs over the life of the facility. Cardno was initially ranked last on this criterion. However, the EC identified that Cardno’s higher cost was due to its proposed high number of technical advisers. As these advisers would be paid for directly by DFAT, the Committee determined that removing these costs would allow for Cardno’s pricing to be better compared to the other tenderers. Taking this into account, the bid was determined to be more competitive compared to the other bids.60

- The EC’s evaluation of value for money did not initially consider financial viability assessments as these were not yet available.61 However, when these reports were completed, the EC assessed this information and presented it to the delegate as part of its recommendation for decision. While Cardno was assessed as satisfactory in terms of its financial viability, the EC recommended that DFAT obtain additional security to mitigate risk in the form of a performance guarantee from the parent company, Cardno Limited.62 During contract negotiations, DFAT agreed to waive the requirement of a performance guarantee.63 The delegate was advised that the inclusion of clauses in the contract (relating to Definitions, Early Notification and Termination for Breach) would address concerns raised in the financial viability assessment. However, advice did not provide detail on how the financial viability risk would be mitigated by this approach.

- Each of the proposals were risk assessed by the EC on technical risk and commercial and financial risk. Cardno was rated as low risk for both risk types.

2.43 The EC provided an overall value for money ranking for each of the bidders, recommending Cardno as the preferred supplier. In June 2016, the delegate approved the tender evaluation outcome.64

2.44 While the delegate was apprised of adjustments to Cardno’s price and of its assessed financial viability in the evaluation outcome minute, there would have been merit in providing the delegate with a revised overall value for money assessment as:

- Cardno’s financial proposal would have reflected a more comparable price with other tenderers; and

- the financial viability assessment forms part of the systematic consideration of risk.

While the overall ranking based on the value for money assessment may not have changed in light of these factors, it would have provided a more complete basis for, and record of the value for money evaluation.

PAGP

2.45 The tender period for the procurement of the PAGP closed on 6 October 2015. Four submissions were received. An Evaluation Board (EB) was established to provide a recommendation on which proposal represented the best overall value for money.

2.46 The assessment of value for money under the EB’s Evaluation Plan was undertaken in four areas: technical; operations; commercial; and risk. These assessments were conducted by separate committees reporting to the Board.65

- The technical evaluation was conducted by the Technical Evaluation Committee. Proposals were assessed out of 100 on their technical ability. The committee assessed Abt as the second ranked tenderer on its technical proposal, although the difference between the first and second tenderers was relatively small (4.5 points).

- The operations evaluation was conducted by the Operation Evaluation Committee to examine the bidder’s approach to supporting the delivery of the facility services and the proposed organisational structures for managing the PAGP. The committee assessed Abt as the strongest tenderer and a clear first.

- The commercial evaluation was conducted to assess if the tenderer’s proposal was cost effective, competitive and provided for the full delivery of the proposed technical and operational activities. Abt was assessed as the best commercial tender.

- The risk evaluation was conducted with reference to the assessed financial viability of the tenderer and the compliance of the proposal with the terms of the RFT. Abt’s proposal was considered to be the lowest risk proposal.

2.47 Abt was ranked first across each of the evaluation areas, except for technical ability where it came a close second. When the operations score was taken into account, Abt remained the preferred bidder.

2.48 The EB also tested value for money against five aid program expenditure scenarios (ranging from $200 million to $400 million) using a value for money index.66 Abt was assessed as representing the best value for money for three of the scenarios.67 The Evaluation Board recommended Abt as the preferred tenderer, as its proposal was assessed as representing best value for money overall.

2.49 This recommendation was approved by the delegate68 on 19 December 2015.

Contracting — negotiation and finalisation

KIAT

2.50 DFAT conducted formal negotiations with Cardno between July and August 2016, entering into a contract in September 2016. Negotiations clarified adviser support costs for the design and implementation phases. Agreement was reached to reduce the number and cost of technical advisers, achieving an 18.5 per cent reduction in adviser-related costs.69 Cardno completed the Final Design Document for the KIAT Facility in February 2017.

2.51 The commissioning of Cardno to also deliver implementation services was contingent on DFAT enacting an amendment to the original contract. The structure of the design–implement contract thereby provided a mechanism for re-testing value for money before proceeding to the implementation stage. DFAT negotiated with Cardno to improve the terms of the contract. This resulted in more favourable performance and management fee arrangements.70 However, DFAT did not conduct an overall assessment of value for money linking deliverables and price, despite the relatively high value of the implementation phase ($140 million)71 and a revised statement of requirements.72

PAGP

2.52 For PAGP, the second preferred tender was close to the first. While the tenderer achieved a higher ranking on technical ability, it had also submitted a higher price. In light of this, DFAT could have considered adopting a ‘best and final offer’ process, involving a formal request that tenderers indicate if they are able to improve their proposals.

2.53 DFAT commenced negotiations with Abt in December 2015. As the draft deed set out only a high-level program of work and did not specify the activities to be transferred to the PAGP, there was a need to more clearly define the scope of work to be undertaken under the contract.73 DFAT also negotiated on three issues related to performance: pricing and the proportion of payments linked to performance; the flexibility of the facility platform in scaling up as PAGP activities increased; and establishing a process for adding service orders to the facility. DFAT and Abt entered into a deed of standing offer on 4 April 2016.

General negotiation planning

2.54 Formal plans were not developed to support either the KIAT or PAGP contract negotiation processes.74 DFAT has since developed an optional template to support negotiation planning.75 DFAT’s standard practice is to conduct negotiations only with the first ranked tenderer. Negotiations with the next preferred tenderer are commenced if agreement cannot be reached with the preferred tenderer. For both KIAT and PAGP, DFAT retained the option of opening negotiations with the next preferred tenderer.

Contracting — payment structure

2.55 A contract should provide incentives for the contractor to deliver value for money throughout the life of the investment. The contract for a development facility sets out the fee structure for operating the facility and general arrangements for implementing aid activities. All personnel, operational and program costs are paid on a reimbursable basis.

KIAT

2.56 Fees paid to Cardno comprise:

- fixed monthly payments (60 per cent of total) — not dependent on performance;

- milestone payments (20 per cent) — paid upon the satisfactory completion of milestones; and

- performance payments (20 per cent) — paid on the results of annual DFAT performance assessments. The payment reduces for each performance indicator against which Cardno is rated as less than ‘adequate’.

2.57 Milestone payments are for outputs such as: facility plans; policies and procedures; and reporting. These items are needed to support the functioning of the facility itself. Some milestones relate more directly to the implementation of aid activities (for example, the design of a performance-based grants system; the development of specific aid proposals; or policy briefs).

2.58 The KIAT contract includes a cost control regime. This is intended to reinforce cost consciousness by requiring contractors to: use competitive tender processes when engaging sub-contractors; report expenditure against contract limits; and implement resource-sharing arrangements.

PAGP

2.59 The PAGP was established as a deed of standing offer arrangement with no initial value. The deed sets out the overall scope of the PAGP and allows DFAT to enter into service orders with the managing contractor, as required, to deliver activities against the objectives of the facility. Service orders function as standalone contracts, which specify funding amounts for the activities. As at November 2019, there were six service orders in place under the PAGP.76 These ranged in value from $21 million to $261 million.

2.60 The deed of standing offer arrangement reduces the risk of a single point of failure in the event of contractor underperformance by allowing individual service orders to be terminated and re-tendered.77 The use of service orders therefore supports flexibility in programming and the alignment of resources with specific outputs.

2.61 Unlike other DFAT facilities, the PAGP contract has both a management fee and a procurement fee.78 The management fee is paid in relation to services provided by the facility platform (Service Order 1). The procurement fee is based on the total expenditure (operational and program costs) of service orders for the delivery of aid program activities. A procurement fee was used because of budget uncertainty in Australia and PNG at the time of tendering. The fee is scaled in line with changing levels of funding.

2.62 The management fee is capped at $16.5 million over the life of the facility.79 The procurement fee is set at 5.3 per cent of total reimbursable expenditure.

3. Implementation

Areas examined

This chapter examines whether the department’s arrangements for the implementation of facilities support value for money in the delivery of aid, using the KIAT and the Papua New Guinea–Australia Governance Partnership (PAGP) as case studies.

Conclusion

DFAT’s implementation of the KIAT and PAGP facility arrangements are partially effective in supporting value for money in the delivery of aid. Arrangements for collaborative partnering and high-level decision-making have been established, but supply chain risks are not being appropriately monitored in all instances. DFAT does not effectively analyse facility financial data at an aggregate level to determine whether administration costs are proportionate to the value of aid delivered and is therefore unable to determine whether the KIAT and PGF are realising overall expected efficiencies.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO made two recommendations aimed at strengthening value for money assessments and increasing the visibility, monitoring and analysis of administration costs.

3.1 For this criterion, the audit examined whether DFAT has demonstrated value for money in the implementation of KIAT and PAGP. This involved an assessment of:

- facility governance arrangements — the establishment of facility functions; governance structures; coordination processes with managing contractors; development of aid program activities; and risk management and assurance processes to ensure facilities have the appropriate foundations for achieving value for money; and

- cost oversight — structures for the ongoing monitoring and analysis of facility administration costs in order to ensure that expected efficiencies associated with the facility model are being realised.

Do governance arrangements for the delivery of aid through facilities, including for the management of risk, support the achievement of value for money?

Governance arrangements for the KIAT facility and PAGP are largely effective in supporting the achievement of value for money. DFAT has established appropriate structures for decision-making and coordination with the respective managing contractors. There is inconsistent evidence that value for money assessments are being conducted for individual aid activities developed under the PAGP, and inconsistent compliance with requirements for the monitoring of risk in facility supply chains.

Establishment of facility functions

3.2 Delays in the start-up of both the KIAT and PAGP meant that approximately one year was required to put in place a strategic framework; organisational arrangements; and a pipeline of work aligned with the objectives of the design for each facility respectively. The KIAT and PAGP organisational structures are shown at Appendices 5 and 6.

3.3 The audit examined DFAT’s establishment of core governance functions and processes for the respective facilities.

KIAT

3.4 The final design of the KIAT facility provided the basis for its mobilisation.80 The facility was slower than expected in establishing new streams of work and did not fully expend its aid program funding in the first 18 months.81 This was due to the effort required to transition six substantial activities to the KIAT facility. DFAT guidance issued in July 2019 states that mobilisation plans should specify sufficient human resource allocations for set up and staff recruitment.

PAGP

3.5 DFAT engaged a consultant in December 2015 to assist with the transition of existing contracts to the facility. As the contract with Abt was not finalised until April 201682, the scope to undertake transition activities was limited. While hand-over briefs were prepared for a number of transitioning programs, there was no overarching implementation or risk plan.

3.6 DFAT assessments of the inception of the PAGP indicate that during this period the facility’s effectiveness was impacted by:

- the large number of complex contracts that were required to be novated83;

- unrealistic assumptions about the time, effort and funding requirements for the development of new programs of activity during the first 18 months;

- delays in recruiting qualified international and local facility staff; and

- a lack of fit-for-purpose operational systems to manage budgets and to monitor and report on activities.

Facility governance structures

3.7 Good governance helps a facility to maintain a focus on the purpose of an investment and establish organisational delivery structures aligned with value for money principles. Aid policy objectives are set by the Australian Government in consultation with partner governments, with facility arrangements providing a flexible mechanism to deliver on these through aid programs such as technical assistance and grants. A facility is expected to quickly design and tender for new programs in response to changes in country priorities, while delivering on longer-term development impact goals.

3.8 For both KIAT and PAGP, strategic decision-making authority is vested in a senior management committee co-chaired by the Australian and respective partner government. Each committee’s role is to direct and oversee the activities of the facility to ensure progress toward the achievement of the facility’s strategic objectives. Six-monthly meetings are held to review progress in the implementation of the work program and financial expenditure. These processes are also intended to enable DFAT to respond to changing priorities.

3.9 Each facility’s funding is allocated on an annual basis. A proportion of funding is uncommitted, and the management committee may direct these resources to new priorities.

KIAT

3.10 A number of technical committees have been established to support the senior management committee. These generally meet on a quarterly basis to review the implementation of specific programs of work and to approve new funding. If technical committees cannot reach consensus agreement, decisions are elevated to the senior management committee. Day-to-day management is supported by facility operations manuals and standard operating procedures.

3.11 A range of reporting is produced by the facility to support the review of progress by joint committees. Reporting for compliance and accountability purposes is provided by the managing contractor to the Jakarta post in relation to performance against contract milestones and Key Performance Indicators.

PAGP

3.12 Several changes have been made to the governance structures of the PAGP since its establishment.

3.13 In the early phase of the PAGP, bilateral arrangements for reaching agreement on facility program priorities were not considered effective. Concern centred on stakeholder perceptions that the facility had assumed a decision-making role that properly sat with the Australian and PNG governments. In October 2017, the Australian and PNG governments agreed to name the facility the Papua New Guinea—Australia Governance Partnership. Key changes to operational arrangements were made to give effect to government direction. These included:

- a shift in the facility’s role from the design of activities to delivering activities determined by the Australian and PNG governments;

- the devolution of decision-making from the senior management committee to individual work streams overseen by relevant DFAT and PNG officials; and

- restructuring the corporate unit to ensure it would deliver required support for work stream activity, while appropriately assessing and reporting on facility-level outcomes.84

3.14 The changes, which were reflected in the updated contractual arrangements for the PAGP, were approved by the Australian High Commissioner to PNG. A subsequent internal review in 2019 noted that the new arrangements had addressed stakeholder concerns and reduced some inefficiencies relating to centralised decision-making.

3.15 The new arrangements reduced the managing contractor’s responsibilities for supporting centralised strategy setting. However, management fees under the deed were not adjusted to reflect this.

3.16 Funding for the operation of the PAGP and its activities is derived from six separate allocations. These funding allocations are managed by three senior executives. Recognising a risk that these funding allocations and associated individual work streams could become siloed, DFAT has assigned a Senior Responsible Officer (SRO) to the PAGP.85 The SRO is responsible for ensuring the facility meets overall outcomes and for managing strategic risks.

The DFAT and managing contractor relationship

3.17 Effective collaboration between DFAT and managing contractor personnel in the implementation of aid can: promote common understanding of objectives; increase flexibility and responsiveness to changes in the operating environment; and lead to more effective management of disputes.

3.18 DFAT guidance emphasises the importance of DFAT retaining responsibility for strategic engagement with partner governments, while recognising that facility personnel will need to interact on a day-to-day basis with partner government officials and the community to be effective in their role.

3.19 The KIAT facility has established effective partnering and working arrangements through clear governance and business processes. These recognise the differing roles of DFAT and the contractor in the design and delivery of aid. Charters set out protocols of engagement between the three main parties of DFAT, the Government of Indonesia and the facility contractor. Processes for the development of aid activities are underpinned by this understanding.

3.20 The design of the PAGP envisioned the facility contractor having a strong capacity to design aid program activities, with post only overseeing those initiatives considered high risk. Over the course of implementation, the respective roles of DFAT and the facility contractor in the development of aid program activities have changed. The facility contractor’s role is now largely defined as an implementing arm of post. This approach risks not making full use of the expertise and experience offered by the managing contractor, potentially diminishing value for money outcomes.

Development of aid activities under the facility structure

3.21 Facilities are a mechanism for developing a pipeline of aid activities over the life of an investment. A key driver of activity development is the need for each investment to meet annual and overall investment expenditure targets.

3.22 Similar to a standing offer arrangement, DFAT makes use of aid design and implementation services, as needed. The process of activity development involves:

- determining requirements — proposals may be generated by DFAT, the partner government or via facility personnel or contracted advisers;

- the preparation of proposals, including an estimated budget — involving consultation between DFAT, stakeholders and the facility at working level;

- DFAT approval based on consultation with the partner government — this may involve consideration by a management or technical committee; and

- implementation — monitored by the facility which reports to DFAT and partner government.

3.23 Value for money must still be considered each time services are procured.86 The audit examined KIAT and PAGP records to determine how this requirement had been applied in the development and approval of proposals.87

KIAT

3.24 The KIAT facility uses an aid activity development process, which has defined approval ‘gates’ (see Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1: KIAT aid activity design and approval process

Source: ANAO analysis of data provided by DFAT.

Minor activities

3.25 Gate points for DFAT approvals are clearly defined. Activities with an estimated value of less than $500,000 are classified as minor activities and do not require the development of concept notes or designs (phases 3 and 4). KIAT undertakes competitive tender processes as a requirement under its contract, reflecting requirements of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules (CPRs). As at August 2019, half of all activities managed by the facility had been classified as minor, with an average value of $196,000 (comprising eight per cent of the total value of activities).

Major activities

3.26 There is evidence that DFAT staff actively contribute to the development of major activities in KIAT, providing varying levels of feedback. Comments and questions in documents reviewed centred on matters of effectiveness. As at August 2019, 21 major activities above $500,000 had been approved by DFAT with an average value of $2.5 million per activity.

3.27 DFAT relies on the managing contractor to maintain formal records of how, when and who provided funding approvals. The terms of the KIAT and PAGP contracts stipulate that DFAT retains legal ownership of all records created for the provision of the goods and services by the managing contractor. Contractors are required to transfer records to DFAT upon termination or conclusion of the contract. This supports DFAT to meet Commonwealth record-keeping obligations.88 DFAT should also ensure records of proposal approvals can be readily accessed and verified by DFAT personnel throughout the implementation of a facility.

PAGP

3.28 The PAGP does not have an equivalent documented activity development process. Under the deed of standing offer, DFAT approves work for activities through an Annual Work Plan process. Each work stream and the platform develops a high-level annual work plan and budget that outlines areas of activity and the maximum amount available for those activities for the financial year. These are approved by senior personnel at post and confirmed at a senior management meeting held between post and the managing contractor.

3.29 Briefs for individual activities are developed for high risk and high value proposals. DFAT advised that activity development processes reflect the specific needs of each work stream. In reviewing a sample of activity briefs, the ANAO found the extent to which these linked objectives, deliverables and costs, as part of a value for money assessment, varied considerably, and there were inconsistencies in the extent to which approvals had been recorded.89

Recommendation no.2

3.30 That DFAT ensures that the assessment of individual aid activities under a facility are subject to appropriate value for money assessment and approvals processes.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade response: Agreed.

Facility risk management and assurance processes

3.31 The aid program often operates in environments where there is a heightened risk of financial misappropriation or where there may be different standards of community health and safety. While the facility contractor manages sub-contractors and non-government organisations, DFAT remains accountable for aid investments achieving objectives in compliance with Australian Government policies and standards, including for how well the contractor manages delivery partners.

Risk management

3.32 DFAT has developed guidance to assist delegates to meet requirements under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act), including to appropriately manage risk.90 Delegates are to ensure managing contractors have systems in place for managing program implementation risks.

3.33 The KIAT facility has a risk plan, which sets out DFAT and managing contractor roles and responsibilities and processes for monitoring and managing risk. A comprehensive risk register for each work program, and the facility as a whole, has been developed. DFAT requires risk registers to be reviewed at least quarterly to respond to changes in the risk environment and to ensure controls remain effective. Jakarta post and the managing contractor comply with this requirement.

3.34 For the PAGP, risk registers have been developed for each work stream and are reviewed on a six-monthly basis. A ‘risks, threats and opportunities’ report exists at the facility level and is reviewed monthly. While the report provides a high-level summary of risks, it does not rate levels of risk or assign responsibility for managing risks. As at February 2020, an organisation-wide risk management system was in the process of being established. It is intended that this will incorporate facility level risk registers.91

Fraud

3.35 Under PGPA Rule 1092 an entity must take all reasonable measures to prevent, detect and correct fraud.93 A 2017 review of DFAT’s management of fraud identified risks arising from the growth of facility sub-contracting arrangements. DFAT does not specifically monitor the frequency of fraud associated with facility arrangements, however it advised the ANAO on instances of potential fraud reported by Cardno and Abt over a two-year period for all investments (including programs other than KIAT and PAGP).94

- Cardno — 29 detected by managing contractor and six by sub-contractor (of these, 15 cases were confirmed as fraud); and

- Abt — 41 detected by managing contractor and seven by sub-contractor (of these, 35 cases were confirmed as fraud).

3.36 The efficacy of DFAT’s fraud control system is subject to a separate ANAO performance audit and therefore has not been examined further in this audit.95

Sub-contractor due diligence

3.37 DFAT policy requires managing contractors to conduct due diligence checks of delivery partners (sub-contractors and non-government organisations) before awarding contracts. Checks are aimed at providing assurance about policies, processes and controls for mitigating key risks.96 DFAT’s Environmental and Social Safeguard Policy for the aid program sets out mandatory risk and safeguard processes that apply to working with partners. The policy requires early identification of risks during planning and throughout the life of the investment.97

KIAT

3.38 Cardno has standard policies and procedures for ensuring compliance with DFAT’s assurance requirements throughout its delivery chain. As at July 2019, due diligence checks were finalised for 10 of 38 active sub-contracts, representing five different sub-contracted entities, with remaining checks partially finalised. Senior management of Cardno had become aware in December 2018 of the company’s non-conformance with DFAT and Cardno policy, but did not inform DFAT until this audit requested evidence of sub-contractor checks in June 2019. A majority of checks were then completed by 9 August 2019, with all checks completed by December 2019.

3.39 KIAT has established a web-based management information system (MIS).98 The MIS stores due diligence and other reports completed by the facility and can be accessed by both managing contractor and DFAT personnel. In 2019 Jakarta post introduced an assurance plan and reporting system for DFAT’s aid program in Indonesia.

PAGP

3.40 Port Moresby post does not have an overarching formal assurance plan and reporting system for DFAT’s aid program in-country. PAGP processes for ensuring sub-contractor and NGO compliance are thorough and records are well maintained. Processes include a set of legal and compliance checks each time a contract is let; proactive field education about DFAT requirements; and regular site visits.

Has DFAT implemented processes to effectively monitor and analyse facility costs?

DFAT’s implementation of processes for monitoring and analysing facility costs are partly effective. DFAT does not routinely monitor administration costs for the purposes of analysing costs across facilities, and is therefore unable to determine whether the KIAT and PAGP are realising expected efficiencies. Audit analysis indicates that the costs associated with establishing and operating each of the two facilities are tracking higher than budgeted as a proportion of expenditure on aid activity.

3.41 Facility costs comprise:

- direct expenditure on aid programs, projects and activities; and

- costs that are administrative in nature and result from processes of aid delivery (management fees and operational costs, including contracted personnel costs).99

3.42 Efficiency in facility operations depends on the costs involved in establishing and operating a facility being proportionate to the benefits delivered. Understanding and monitoring the ratio of administration costs (inputs) to aid expenditure (outputs) is necessary to effectively guide resource allocation, planning and financial management. A range of factors relating to the specific operating context of delivery need to be taken into account when determining an appropriate ratio. This should occur at the investment design stage as part of establishing a baseline for monitoring costs over the life of the investment.

Monitoring facility administration costs

3.43 Staff at the Jakarta and Port Moresby posts generate and review financial data for the purposes of managing invoicing and payments under contracts for the respective facilities and to support financial reporting.

3.44 The KIAT contract requires the managing contractor to seek opportunities for price reductions and savings throughout the life of the facility. There is evidence that post monitors compliance with elements of the contract’s cost control regime, including by addressing sub-contracting costs. The contract does not identify a specific cost savings target to be achieved.

3.45 DFAT expected that the PAGP would deliver significant efficiencies compared with separately tendered programs — a total of $29.4 million in operating cost savings over a five-year period.100 Post has reported some savings in corporate and staff costs (cumulative totals of $4.5 million as at 2017–18 and $9.1 million as at 2018–19), although this has not been verified.101 There have been on-going efforts to improve the operating efficiency of the PAGP, including through an organisational review in 2018 that recommended eliminating duplication in enabling services.