Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

2016-17 Major Projects Report

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of this report is to provide the Auditor‐General’s independent assurance over the status of the selected Major Projects. The status of the selected Major Projects is reported in the Statement by the Secretary of Defence and the Project Data Summary Sheets (PDSSs) prepared by Defence, in accordance with the Guidelines endorsed by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA).

Due to the complexity of material and the multiple sources of information for the 2016-17 Major Projects Report, we are unable to represent the entire document in HTML. You can download the full report in PDF or view selected sections in HTML below. PDF files for individual Project Data Summary Sheets (PDSS) are also available for download.

!Part 1. ANAO Review and Analysis

Summary and Review Conclusion

The Major Projects Report

1. Major Defence equipment acquisition projects (Major Projects) continue to be the subject of parliamentary and public interest. This is due to their high cost and contribution to national security, and the challenges involved in completing them within the specified budget and schedule, and to the required capability.

2. The Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) has reviewed 27 of Defence’s Major Projects in this tenth annual report (2015–16: 26). The objective of the report is ‘…to improve the accountability and transparency of Defence acquisitions for the benefit of Parliament and other stakeholders.’1

3. The Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG) within the Department of Defence (Defence), manages the process of bringing new capabilities into service.2 In 2016–17 CASG provided support to the Australian Defence Force (ADF) through the acquisition and sustainment of required military equipment and supplies3, and expended some $6.2 billion on major and minor capital acquisition projects.4

4. The February 2016 Defence White Paper established the Government’s priorities for future capability investment for the next 20 years and provided for additional spending of over $29 billion across the next decade. More recently, the 2017–18 Defence Portfolio Budget Statements indicated that the Defence budget would total approximately $200 billion over the coming decade, for investing in Defence capability.5 Additionally, the Government commenced its $89 billion investment in Australia’s future shipbuilding industry in April 2017.6

Major Projects selected for review

5. Major Projects are selected for review based on the criteria included in the 2016–17 Major Projects Report (MPR) Guidelines (the Guidelines), as endorsed by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA).7 They represent a selection of the most significant Major Projects managed by Defence.

6. The total approved budget for the Major Projects included in this report is approximately $62.0 billion, covering nearly 59 per cent of the budget within the Approved Major Capital Investment Program of $105.9 billion.8 The selected projects and their approved budgets are listed in Table 1, below.

Table 1: 2016–17 MPR projects and approved budgets at 30 June 20171,2

|

Project Number (Defence Capability Plan) |

Project Name (on Defence advice) |

Defence Abbreviation (on Defence advice) |

Approved Budget $m |

|

AIR 6000 Phase 2A/2B |

New Air Combat Capability |

Joint Strike Fighter |

16 004.9 |

|

SEA 4000 Phase 3 |

Air Warfare Destroyer Build |

AWD Ships |

9 090.1 |

|

AIR 7000 Phase 2B |

Maritime Patrol and Response Aircraft System |

P-8A Poseidon |

5 262.5 |

|

AIR 9000 Phase 2/4/6 |

Multi-Role Helicopter |

MRH90 Helicopters |

3 733.8 |

|

AIR 5349 Phase 3 |

EA-18G Growler Airborne Electronic Attack Capability |

Growler |

3 495.0 |

|

AIR 9000 Phase 8 |

Future Naval Aviation Combat System Helicopter |

MH-60R Seahawk |

3 462.5 |

|

LAND 121 Phase 3B |

Medium Heavy Capability, Field Vehicles, Modules and Trailers |

Overlander Medium/Heavy |

3 363.5 |

|

JP 2048 Phase 4A/4B |

Amphibious Ships (LHD) |

LHD Ships |

3 091.9 |

|

LAND 121 Phase 4 |

Protected Mobility Vehicle – Light |

Hawkei3 |

1 951.1 |

|

AIR 87 Phase 2 |

Armed Reconnaissance Helicopter |

ARH Tiger Helicopters |

1 867.8 |

|

AIR 8000 Phase 2 |

Battlefield Airlift – Caribou Replacement |

Battlefield Airlifter |

1 406.7 |

|

LAND 116 Phase 3 |

Bushmaster Protected Mobility Vehicle |

Bushmaster Vehicles |

1 250.6 |

|

LAND 121 Phase 3A |

Field Vehicles and Trailers |

Overlander Light |

1 017.6 |

|

AIR 7403 Phase 3 |

Additional KC-30A Multi-role Tanker Transport |

Additional MRTT |

855.5 |

|

AIR 5431 Phase 3 |

Civil Military Air Traffic Management System |

CMATS 3 |

730.7 |

|

SEA 1448 Phase 2B |

ANZAC Anti-Ship Missile Defence |

ANZAC ASMD 2B |

678.6 |

|

AIR 9000 Phase 5C |

Additional Medium Lift Helicopters |

Additional Chinook |

637.8 |

|

JP 9000 Phase 7 |

Helicopter Aircrew Training System |

HATS |

474.2 |

|

JP 2072 Phase 2A |

Battlespace Communications System |

Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) |

463.3 |

|

SEA 1439 Phase 4A |

Collins Replacement Combat System |

Collins RCS |

450.4 |

|

SEA 1442 Phase 4 |

Maritime Communications Modernisation |

Maritime Comms |

432.1 |

|

SEA 1429 Phase 2 |

Replacement Heavyweight Torpedo |

Hw Torpedo |

428.0 |

|

JP 2008 Phase 5A |

Indian Ocean Region UHF SATCOM |

UHF SATCOM |

420.5 |

|

SEA 1439 Phase 3 |

Collins Class Submarine Reliability and Sustainability |

Collins R&S |

411.7 |

|

SEA 1448 Phase 2A |

ANZAC Anti-Ship Missile Defence |

ANZAC ASMD 2A |

386.7 |

|

LAND 75 Phase 4 |

Battle Management System |

BMS |

369.1 |

|

JP 2048 Phase 3 |

Amphibious Watercraft Replacement |

LHD Landing Craft |

236.8 |

|

Total 27 |

— |

— |

61 973.4 |

Note 1: Once a project is selected for review, it remains within the portfolio of projects under review until the JCPAA endorses its removal, normally once it has met the capability requirements of Defence.

Note 2: Air to Air Refuelling Capability was removed from the MPR program in 2016–17.

Note 3: Hawkei and CMATS are included in the MPR program for the first time in 2016–17.

Source: The Project Data Summary Sheets in Part 3 of this report.

Report objective and scope

7. The objective of this report is to provide the Auditor-General’s independent assurance over the status of the selected Major Projects. The status of the selected Major Projects is reported in the Statement by the Secretary of Defence and the Project Data Summary Sheets (PDSSs) prepared by Defence. Assurance from the ANAO’s review is conveyed in the Independent Assurance Report by the Auditor-General.

8. The following forecast information is excluded from the scope of the ANAO’s review:

- Section 1.2 Current Status—Materiel Capability Delivery Performance and Section 4.1 Measures of Materiel Capability Delivery Performance;

- Section 1.3 Project Context—Major Risks and Issues and Section 5 – Major Risks and Issues; and

- forecast dates where included in each PDSS.

- Accordingly, the Independent Assurance Report by the Auditor-General does not provide any assurance in relation to this information. However, material inconsistencies identified in relation to this information, are required to be considered in forming the conclusion.

9. The exclusions to the scope of the review noted above are due to a lack of Defence systems from which to provide complete and accurate evidence9, in a sufficiently timely manner to facilitate the review. This has been an area of focus of the JCPAA over a number of years10, and it is intended that all components of the PDSSs will eventually be included within the scope of the ANAO’s review.

10. Separate to the formal review, the ANAO has undertaken an analysis of key elements of the PDSSs—including cost, schedule, progress towards delivery of required capability, project maturity, and risks and issues. Longitudinal analysis across these key elements of projects has also been undertaken.

11. Defence provides further insights and context in its commentary and analysis—although this is not included within the scope of the ANAO’s review.

Review methodology

12. The ANAO has reviewed the PDSSs prepared by Defence as a priority assurance review under section 19A(5) of the Auditor-General Act 1997. The criteria to conduct the review are provided by the Guidelines approved by the JCPAA, and include whether Defence has procedures in place designed to ensure that project information and data was recorded in a complete and accurate manner, for all 27 projects.

13. The review included an assessment of Defence’s systems and controls, including the governance and oversight in place, to ensure appropriate project management. The ANAO also sought representations and confirmations from Defence senior management and industry in relation to the status of the Major Projects in this report.

Report structure

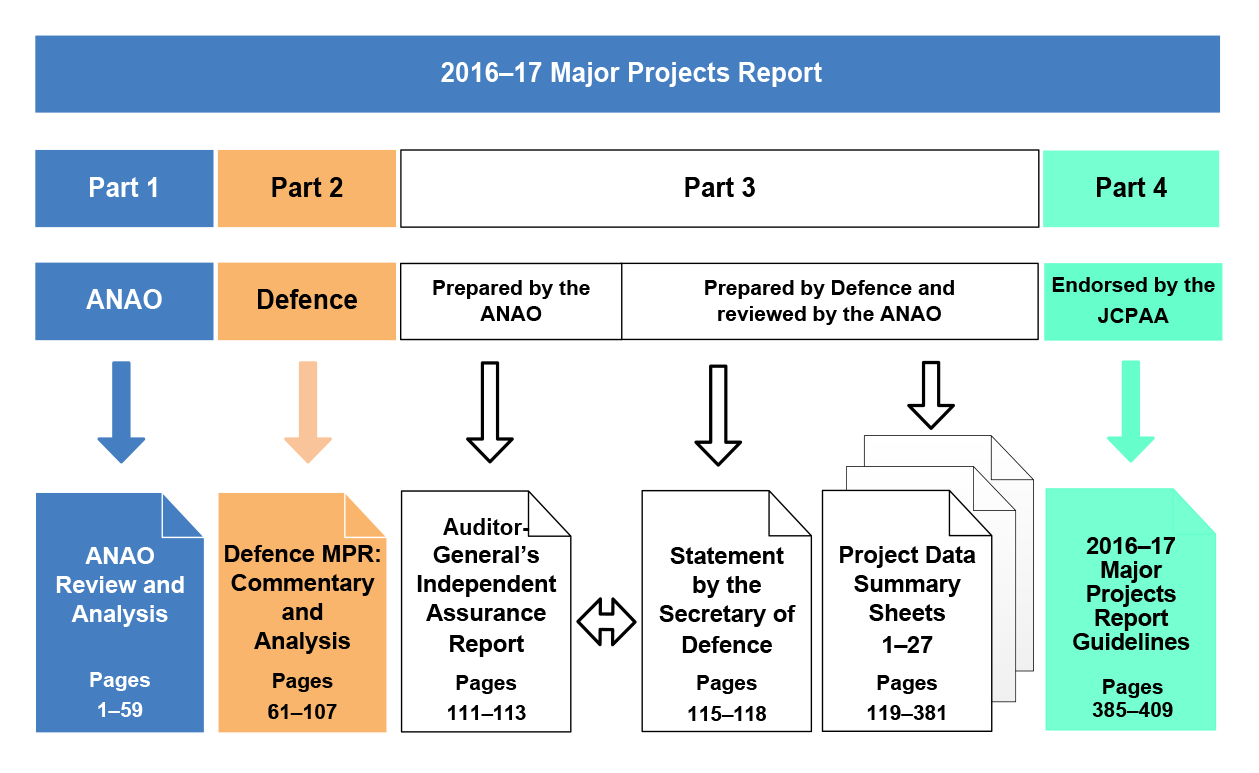

14. The report is organised into four parts:

- Part 1 comprises the ANAO’s review and analysis (pp. 1–59);

- Part 2 comprises Defence’s Commentary, Analysis and Appendices (not included within the scope of the Independent Assurance Report by the Auditor-General) (pp. 61–107);

- Part 3 incorporates the Independent Assurance Report by the Auditor-General, the Statement by the Secretary of Defence, and the PDSSs prepared by Defence as part of the assurance review process (pp. 109–381); and

- Part 4 reproduces the 2016–17 MPR Guidelines endorsed by the JCPAA, which provide the criteria for the compilation of the PDSSs by Defence and the ANAO’s review (pp. 383–409).

- Figure 1, below, depicts the four parts of this report.

Figure 1: 2016–17 Report structure

Note: To assist in conducting inter-report analysis, the presentation of data in the PDSSs remains largely consistent and comparable with the 2015–16 MPR.

Project Data Summary Sheets

15. The PDSSs include unclassified information on project performance, prepared by Defence. As projects appear in the MPR for multiple years, changes to the PDSS from the previous year are depicted in bold orange text.

16. Each PDSS comprises:

- Project Header: including name; capability and acquisition type; Capability Manager; approval dates; total approved and in-year budgets; stage; complexity; and an image;

- Section 1—Project Summary: including description; current status, including financial assurance and contingency statement; context, including background, uniqueness, major risks and issues, and other current sub-projects;

- Section 2—Financial Performance: including budgets and expenditure; variances; and major contracts in place (in addition to quantities delivered as at 30 June 2017);

- Section 3—Schedule Performance: providing information on design development; test and evaluation; and forecasts and achievements against key project milestones, including Initial Materiel Release (IMR), Final Materiel Release (FMR)11, Initial Operational Capability (IOC) and Final Operational Capability (FOC)12;

- Section 4—Materiel Capability Delivery Performance: provides a summary of Defence’s assessment of its expected delivery of key capabilities, the extent to which milestones were achieved (particularly where caveats are placed on the Capability Manager’s declaration of significant milestones), and a description of the constitution of each key milestone;

- Section 5—Major Risks and Issues: outlines the major risks and issues of the project and remedial actions undertaken for each;

- Section 6—Project Maturity: provides a summary of the project’s maturity, as defined by Defence13, and a comparison against the benchmark score;

- Section 7—Lessons Learned: outlines the key lessons that have been learned at the project level (further information on lessons learned by Defence are included in Defence’s Appendix 2); and

- Section 8—Project Line Management: details current project management responsibilities within Defence.

Overall outcomes

Statement by the Secretary of Defence

17. The Statement by the Secretary of Defence was signed on 3 January 2018. The Secretary’s statement provides his opinion that the PDSSs for the 27 selected projects ‘… comply in all material respects with the Guidelines and reflect the status of the projects as at 30 June 2017’.

18. The Secretary also ‘acknowledge[s] the difference of view between Defence and the ANAO in relation to the AIR 87 Phase 2 – Armed Reconnaissance Helicopter PDSS’. Further detail is provided in paragraphs 20 to 25 below (see Conclusion by the Auditor-General).

19. In addition, the Statement by the Secretary of Defence details significant events occurring post 30 June 2017, which materially impact the projects included in the report, and which should be read in conjunction with the individual PDSSs. These include: Joint Strike Fighter, AWD Ships, MRH90 Helicopters, Hawkei, ARH Tiger Helicopters, Battlefield Airlifter, Overlander Light, Additional MRTT, CMATS, ANZAC ASMD 2B, Additional Chinook, HATS, Battle Comm. Sys. (Land), Maritime Comms, Hw Torpedo, Collins R&S, ANZAC ASMD 2A and BMS.

Conclusion by the Auditor-General

20. The Auditor-General has been unable to provide an unqualified Independent Assurance Report for 2016–17 as a number of matters were identified, in the course of the ANAO’s review, that resulted in the qualification of progress and performance as reported in one Project Data Summary Sheet (PDSS).

21. The review Guidelines define a project as the acquisition or upgrade of Specialist Military Equipment. The Guidelines provide that the scope of Defence reporting includes the performance of selected major equipment acquisitions and associated sustainment activities, where applicable.

22. The ARH Tiger Helicopters PDSS has been prepared on the basis of the Defence acquisition project14, which is narrower than the scope established in the Guidelines.

- The project maturity score in Section 6.1 of the ARH Tiger Helicopters PDSS reports a total of 69 out of a maximum of 70 (98.6 per cent) at the time of transition from acquisition to sustainment in April 2017. Noting the caveats, capability deficiencies and obsolescence issues at the declaration of FOC in April 201615, 16, and considering that only two of the nine caveats applying at FOC have been lifted by the Capability Manager (in July 2017), this score does not accurately or completely represent the project’s maturity as at 30 June 2017. The Auditor-General’s conclusion has had regard to the July 2017 events.

23. In addition, a material inconsistency has been identified in the forecast information. Section 4.1 in the ARH Tiger Helicopters PDSS reports that materiel capability delivery performance is at 100 per cent, indicating that materiel capability delivery performance has been met. Rate of effort continues to be lower than planned17, and expert analysis commissioned by Defence in April 2016 indicates that the program will remain incapable of fully meeting expectations relating to reliability, availability, maintainability and rate of effort.18

24. The Auditor-General also drew attention to these matters in the Independent Assurance Report for 2015–16.19

25. With the exception of the matters above, the Auditor-General has concluded in the Independent Assurance Report for 2016–17 that ‘…nothing has come to my attention that causes me to believe that the information in the 27 Project Data Summary Sheets in Part 3 (PDSSs) and the Statement by the Secretary of Defence, excluding the forecast information, has not been prepared in all material respects in accordance with the 2016–17 Major Projects Report Guidelines (the Guidelines), as endorsed by the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit.’

26. Additionally, in 2016–17, a number of administrative issues were observed in the course of the ANAO’s review, as summarised below:

- non-compliance with corporate guidance resulting in inconsistent approaches taken to contingency allocation (Section 1 of the PDSS). See further explanation in paragraphs 1.36 to 1.40;

- a change to the basis of financial reporting and the application of incorrect exchange rates when managing contracts (Section 2 of the PDSS). See further explanation in paragraphs 1.41 to 1.43 and paragraph 2.25;

- a lack of oversight, non-compliance with corporate guidance and the use of spreadsheets20 in the management of risks and issues (Section 5 of the PDSS). See further explanation in paragraphs 1.44 to 1.50;

- outdated policy guidance for the project maturity framework21 (Section 6 of the PDSS). See further explanation in paragraphs 1.51 to 1.57; and

- an increase in the number of MPR projects which have achieved significant milestones with caveats. See further explanation in paragraphs 1.58 to 1.60.

ANAO’s analysis of project performance

27. As discussed, the ANAO has undertaken an analysis of key elements of the Defence PDSSs—including cost, schedule, progress towards delivery of required capability, project maturity, risks and issues, and in particular, longitudinal analysis across these key elements of projects. Table 2, below, provides: summary data on Defence’s progress toward delivering the capabilities for the Major Projects covered in this report; and compares current data against that reported in previous editions of the MPR. This section also contains a summary analysis of the three principal components of project performance: cost, schedule and capability.

Table 2: Summary longitudinal analysis

|

|

2014–15 MPR |

2015–16 MPR |

2016–17 MPR |

|

Number of Projects |

25 |

26 |

27 |

|

Total Approved Budget |

$60.5 billion |

$62.7 billion |

$62.0 billion |

|

Total Expenditure Against Total Approved Budget |

$29.0 billion (48.0 per cent) |

$29.4 billion (46.9 per cent) |

$32.1 billion (51.7 per cent) |

|

Total In-year Expenditure Against In-year Budget |

$4.8 billion (96.8 per cent) |

$3.9 billion (91.2 per cent) |

$4.1 billion (96.6 per cent) |

|

Total Budget Variation since Second Pass Approval |

$18.5 billion (30.6 per cent) |

$22.8 billion (36.3 per cent) |

$21.5 billion (34.7 per cent) |

|

In-year Approved Budget Variation |

$2.9 billion (4.9 per cent) |

$4.9 billion (7.8 per cent) |

-$1.6 billion (-2.6 per cent) |

|

Total Schedule Slippage 1, 2 |

768 months (28 per cent) |

708 months (26 per cent) |

793 months (29 per cent) |

|

Average Schedule Slippage per Project |

31 months |

28 months |

30 months |

|

In-year Schedule Slippage 3 |

41 months (2 per cent) |

42 months (1 per cent) |

149 months (6 per cent) |

|

Total Project Maturity 4 |

1 401 / 1 750 (80 per cent) |

1 479 / 1 820 (81 per cent) |

1 531 / 1 890 (81 per cent) |

|

Total Reported Risks and Issues 5, 6 |

129 |

123 |

136 |

|

Expected Capability (Defence Reporting)

|

97 per cent |

99 per cent |

98 per cent |

|

3 per cent |

1 per cent |

2 per cent |

|

0 per cent |

0 per cent 7 |

0 per cent 7 |

Refer to paragraphs 27 to 42 in Part 1 of this report.

Note 1: The data for the 27 Major Projects in the 2016–17 MPR compares the data from projects in the 2015–16 MPR and 2014–15 MPR.

Note 2: Slippage refers to the difference between the original government approved date and the current forecast date. These figures exclude schedule reductions over the life of the project. However, Figure 10 reports in-year schedule reductions.

Note 3: Based on the 23 repeat projects from the 2013–14 MPR, 23 repeat projects from the 2014–15 MPR, 25 repeat projects from the 2015–16 MPR respectively, and one new project (CMATS) that had slippage in 2016–17.

Note 4: The figures represent the total of the reported maturity scores divided by the total benchmark maturity score, in the PDSSs across all projects.

Note 5: The figures represent the combined number of open high and extreme risks and issues reported in the PDSSs across all projects. Risks and issues may be aggregated at a strategic level.

Note 6: The grey section of the table is excluded from the scope of the ANAO’s priority assurance review, due to a lack of systems from which to obtain complete and accurate evidence in a sufficiently timely manner to facilitate the review.

Note 7: Defence has advised that Joint Strike Fighter will not deliver one element of capability at FOC (which equates to approximately one per cent). However, across all 27 Major Projects this percentage rounds to zero per cent.

Cost

28. Cost management is an ongoing process in Defence’s administration of the Major Projects. While all projects reported that they could continue to operate within the total approved budget of $62.0 billion, CMATS is seeking approval for a significant Real Cost Increase22 which is anticipated to be considered by government in February 2018. In addition, ARH Tiger Helicopters was provided a heavily caveated Final Operational Capability (FOC) in April 2016 without having delivered all of the capabilities required as part of the acquisition project.23 Delivery of outstanding requirements has been transferred from acquisition to sustainment management within CASG.

29. The approved budget for Major Projects included in this MPR has increased by $21.5 billion (34.7 per cent) since Second Pass Approval, as detailed in Table 3, below. However, as the MPR predominantly focusses on the approved capital budget, the ongoing costs of Project Offices (acquisition), training, replacement capability, etc., are not reported here.

Table 3: Budget variation post Second Pass Approval by variation type1, 2

|

Project |

Variation |

Explanation |

Year |

Amount $b |

|

MRH90 Helicopters |

Scope increase/budget transfers |

34 additional aircraft |

2005–06 |

2.4 |

|

Bushmaster Vehicles |

Scope increases |

715 additional vehicles |

2007–08, 2011–12 and 2012–13 |

0.8 |

|

Joint Strike Fighter |

Scope increase |

58 additional aircraft |

2013–14 |

10.5 |

|

Overlander Medium/Heavy |

Scope increase/budget transfers |

Real Cost Increase |

2013–14 |

0.7 |

|

AWD Ships |

Real Cost Increase/budget transfers |

Real Cost Increase of $1.2b offset by $0.1b transfer for facilities in 2014 |

2013–14 and 2015–16 |

1.1 |

|

P-8A Poseidon |

Scope increase |

Four additional aircraft |

2015–16 |

1.3 |

|

Other |

Scope increase/budget transfers (net) |

Other scope changes and transfers |

Various |

(2.4) |

|

|

Sub-total |

14.4 |

||

|

Price Indexation – materials and labour (net) (to July 2010) 2 |

3.6 |

|||

|

Exchange Variation – foreign exchange (net) (to 30 June 2017) |

3.5 |

|||

|

|

Total |

|

|

21.5 |

Note 1: Variations greater than $500 million are included in this table. For the breakdown of in-year variation, refer to Table 10 of this report.

Note 2: Prior to 1 July 2010, projects were periodically supplemented for price indexation, whereas the allocation for price indexation is now provided for on an out-turned basis at Second Pass Approval.

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2016–17 PDSSs.

Schedule

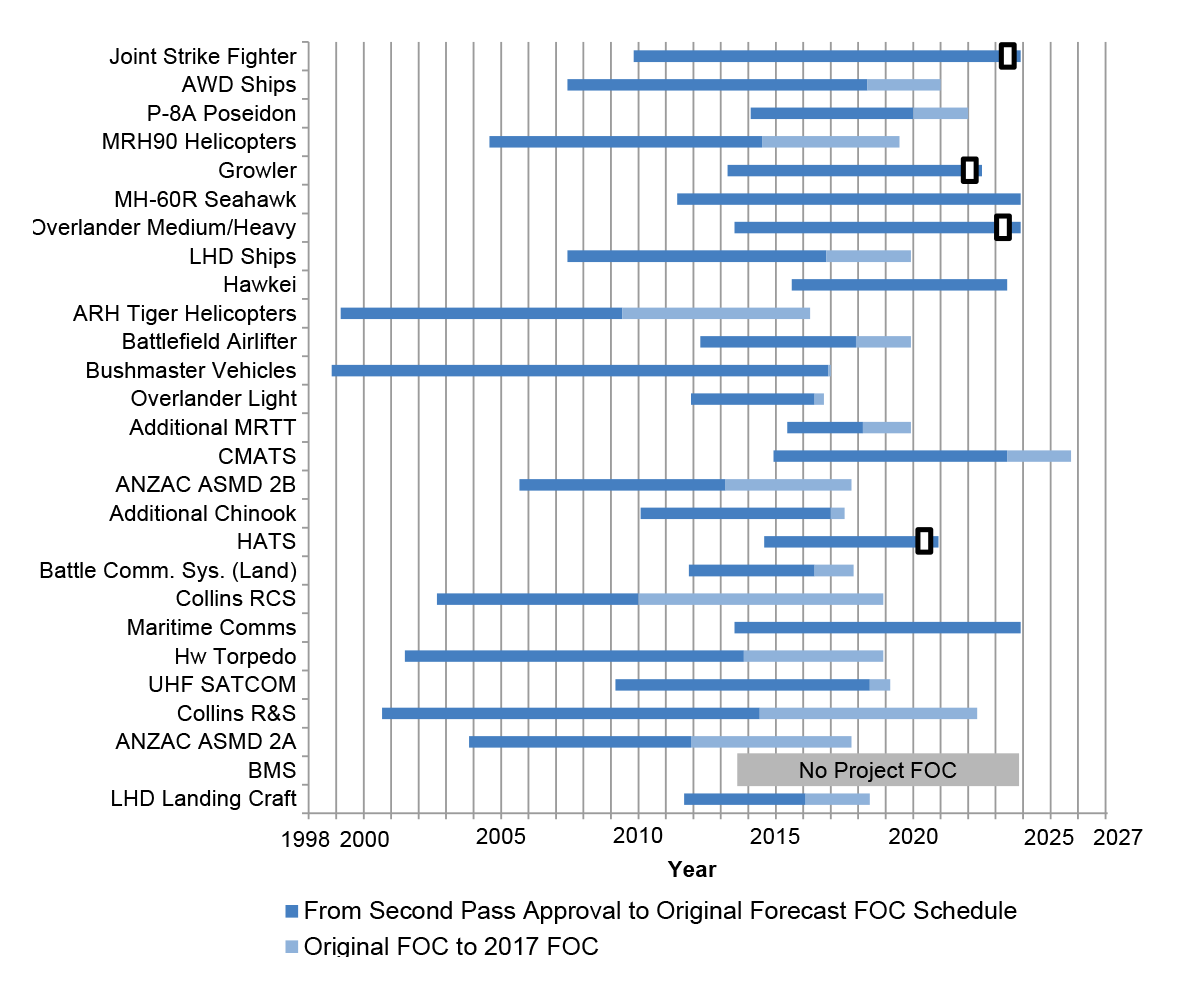

30. Delivering Major Projects on schedule continues to present challenges for Defence24; affecting when the capability is made available for operational release and deployment by the Australian Defence Force, as well as the cost of delivery.25

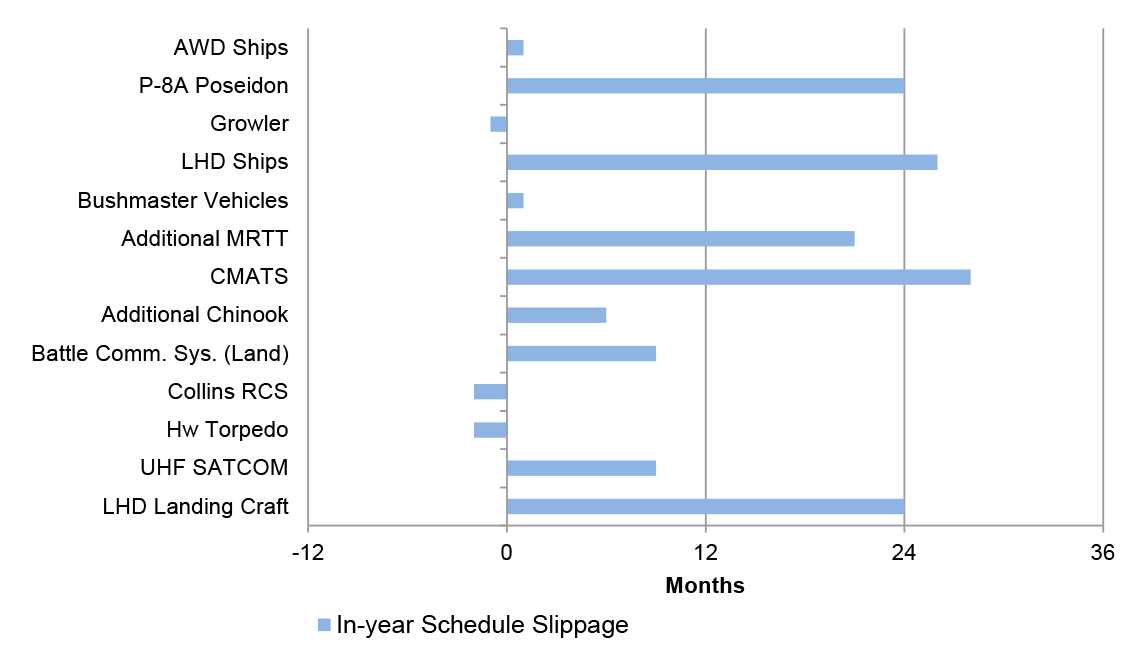

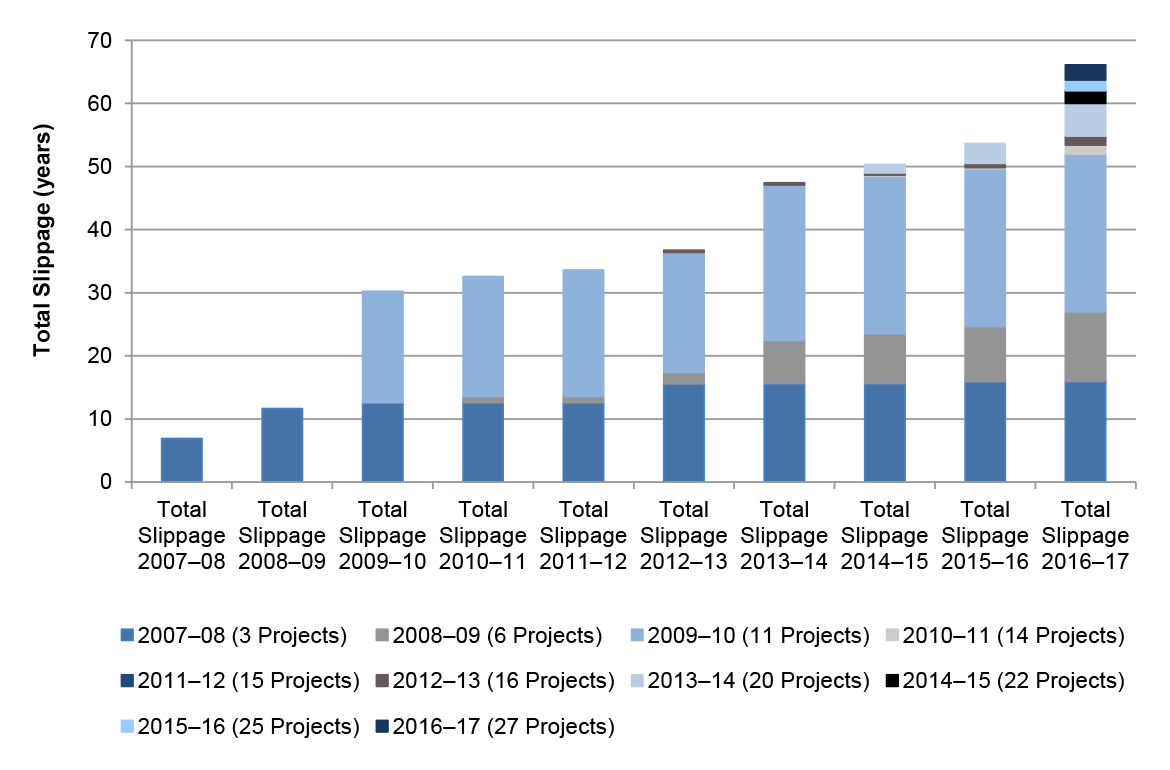

31. The total schedule slippage26 for the 27 selected Major Projects, as at 30 June 2017, is 793 months (2015–16: 708 months) when compared to the initial schedule. This represents a 29 per cent (2015–16: 26 per cent) increase since approval. Table 4 below includes details of in-year and total schedule slippage by project. While the table shows a six per cent in-year slippage for 2016–17, the removal of a completed project (Air to Air Refuel) has removed 64 months of slippage. The effect of this project exiting the review explains the difference between the total schedule slippage in 2016–17 (85 months) and the total in-year slippage amount (149 months).

Table 4: Schedule slippage from original planned Final Operational Capability1

|

Project |

In-year (months) |

Total (months) |

|

Joint Strike Fighter 3 |

0 |

2 |

|

AWD Ships |

1 |

35 |

|

P-8A Poseidon |

24 |

24 |

|

MRH90 Helicopters |

0 |

60 |

|

Growler |

0 |

0 |

|

MH-60R Seahawk |

0 |

0 |

|

Overlander Medium/Heavy |

0 |

5 |

|

LHD Ships 3 |

26 |

37 |

|

Hawkei |

0 |

0 |

|

ARH Tiger Helicopters 2 |

0 |

82 |

|

Battlefield Airlifter |

0 |

24 |

|

Bushmaster Vehicles |

1 |

1 |

|

Overlander Light |

0 |

9 |

|

Additional MRTT |

21 |

21 |

|

CMATS 3 |

28 |

28 |

|

ANZAC ASMD 2B |

0 |

57 |

|

Additional Chinook |

6 |

6 |

|

HATS |

0 |

0 |

|

Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) 3 |

9 |

17 |

|

Collins RCS |

0 |

109 |

|

Maritime Comms |

0 |

0 |

|

Hw Torpedo |

0 |

63 |

|

UHF SATCOM 3 |

9 |

9 |

|

Collins R&S |

0 |

99 |

|

ANZAC ASMD 2A |

0 |

72 |

|

BMS 4 |

N/A |

N/A |

|

LHD Landing Craft |

24 |

33 |

|

Total (months) |

149 |

793 |

|

Total (per cent) |

6 |

29 |

Note 1: Refer to footnote 26.

Note 2: FOC for ARH Tiger Helicopters was declared with caveats. That is, not all capabilities required by government were delivered by the acquisition project.

Note 3: These projects have been identified by Defence as Projects of Interest (see paragraph 1.17 in Part 1).

Note 4: BMS does not have IOC or FOC milestones. These were to be linked to Work Packages B-D which received government approval in September 2017 under LAND 200. Work Package A is expected to achieve FMR and MAA closure in quarter one 2018.

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2016–17 PDSSs.

32. Platform availability has contributed to the slippage experienced within some projects. For example, the submarine programs have been impacted by changes to docking schedules, following government commissioned reviews. Significant delays have also been experienced by those projects with the most developmental content: AWD Ships, MRH90 Helicopters, ARH Tiger Helicopters, CMATS and ANZAC ASMD 2B. Additionally, delays to operational test and evaluation activities have led to further delays to the LHD Ships and LHD Landing Craft projects.

33. Table 5, below, provides details of total schedule slippage by project, for projects that have exited the MPR. Compared to the 793 months total schedule slippage for the current 27 Major Projects, the 14 projects which have exited the MPR have reported accumulated schedule slippage of 601 months, as at their respective exit dates. Again, schedule slippage was more pronounced in projects with the most developmental content.

Table 5: Schedule slippage for projects which have exited the MPR

|

Project |

Total (months) |

|

Wedgetail (Developmental) |

78 |

|

Super Hornet (MOTS) |

0 |

|

Hornet Upgrade (Australianised MOTS) |

39 |

|

C-17 Heavy Airlift (MOTS) |

0 |

|

Air to Air Refuel (Developmental) |

64 |

|

FFG Upgrade (Developmental) |

132 |

|

Next Gen Satellite 1 (MOTS) |

0 |

|

HF Modernisation (Developmental) |

147 |

|

Armidales (Australianised MOTS) |

45 |

|

SM-2 Missile (Australianised MOTS) |

26 |

|

155mm Howitzer (MOTS) |

7 |

|

Stand Off Weapon (Australianised MOTS) |

37 |

|

Battle Comm. Sys. (Australianised MOTS) |

24 |

|

C-RAM (MOTS) |

2 |

|

Total |

601 |

Note 1: Next Gen Satellite shows slippage in Figure 8, which related to the final capability milestones at the time. By the time it reached FOC, a new final capability milestone had been introduced and slippage was reduced.

Source: PDSSs in published Major Projects Reports and ANAO analysis.

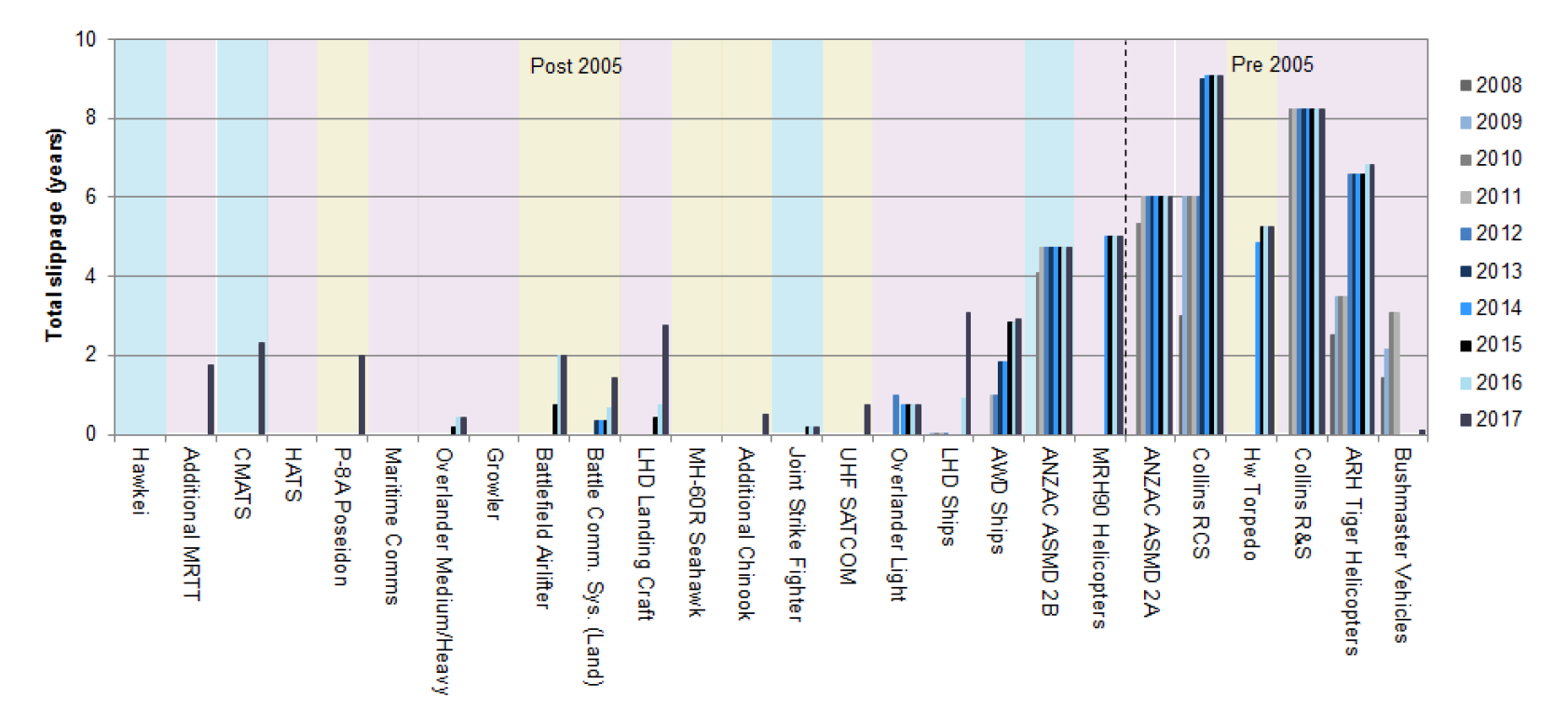

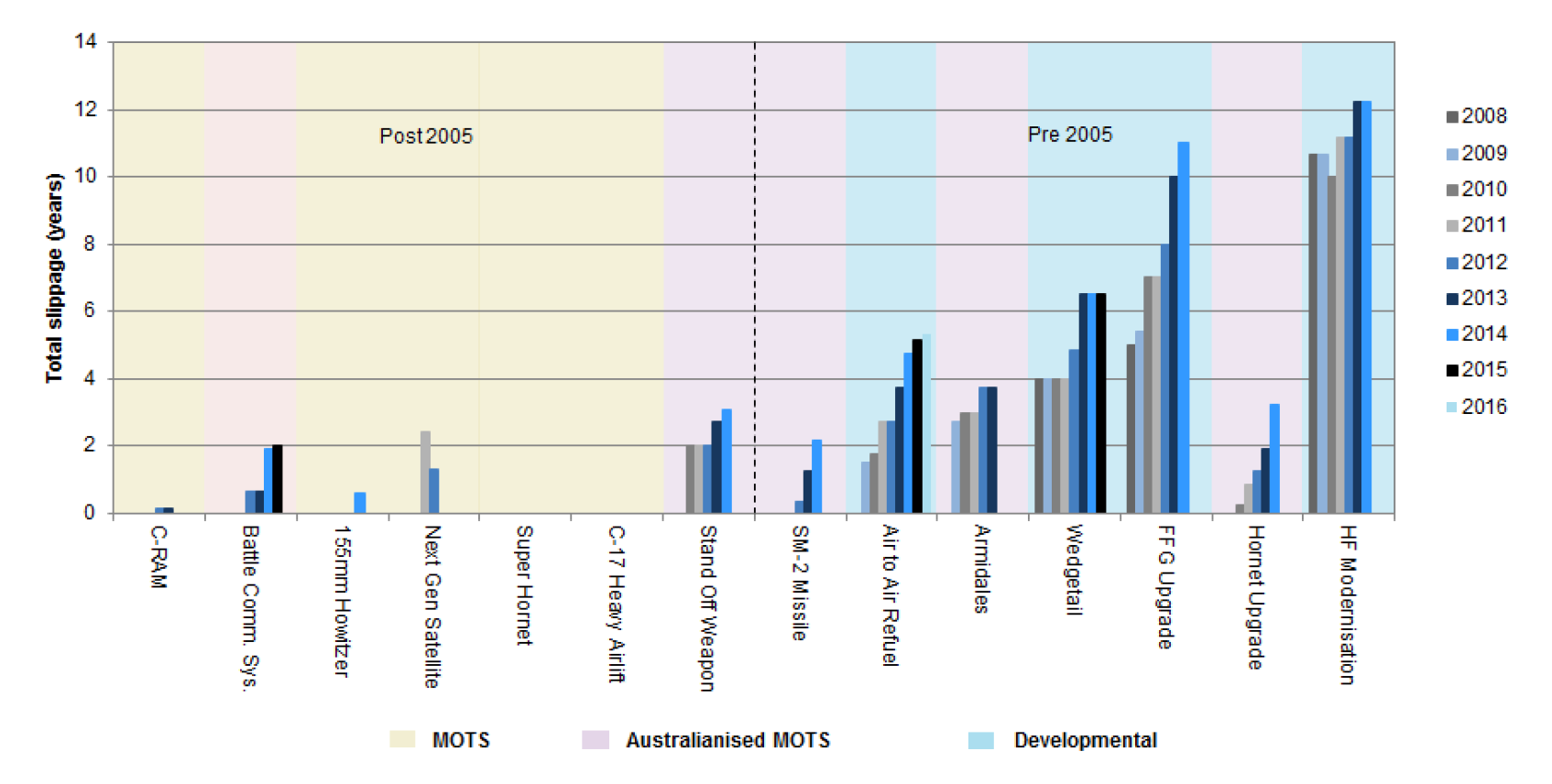

34. Additional ANAO analysis (refer to Figure 7, on page 46) has compared project slippage against the Defence classification of projects as Military Off-The-Shelf (MOTS), Australianised MOTS or developmental.27 These classifications are a general indicator of the difficulty associated with the procurement process. This analysis highlights, prima facie, that the more developmental in nature a project is, the more likely it will result in project slippage, as well as demonstrating one of the advantages of selecting MOTS acquisitions.28

35. Figure 8 (on page 47) provides analysis of projects either completed, or removed from the MPR review, and shows that a focus on MOTS acquisitions has assisted in reducing schedule slippage. Figure 8 was requested by the JCPAA in May 2014.29

36. Longitudinal analysis indicates that while the reasons for schedule slippage vary, it primarily reflects the underestimation of both the scope and complexity of work, particularly for Australianised MOTS and developmental projects (see page 84 in Part 2).

Capability

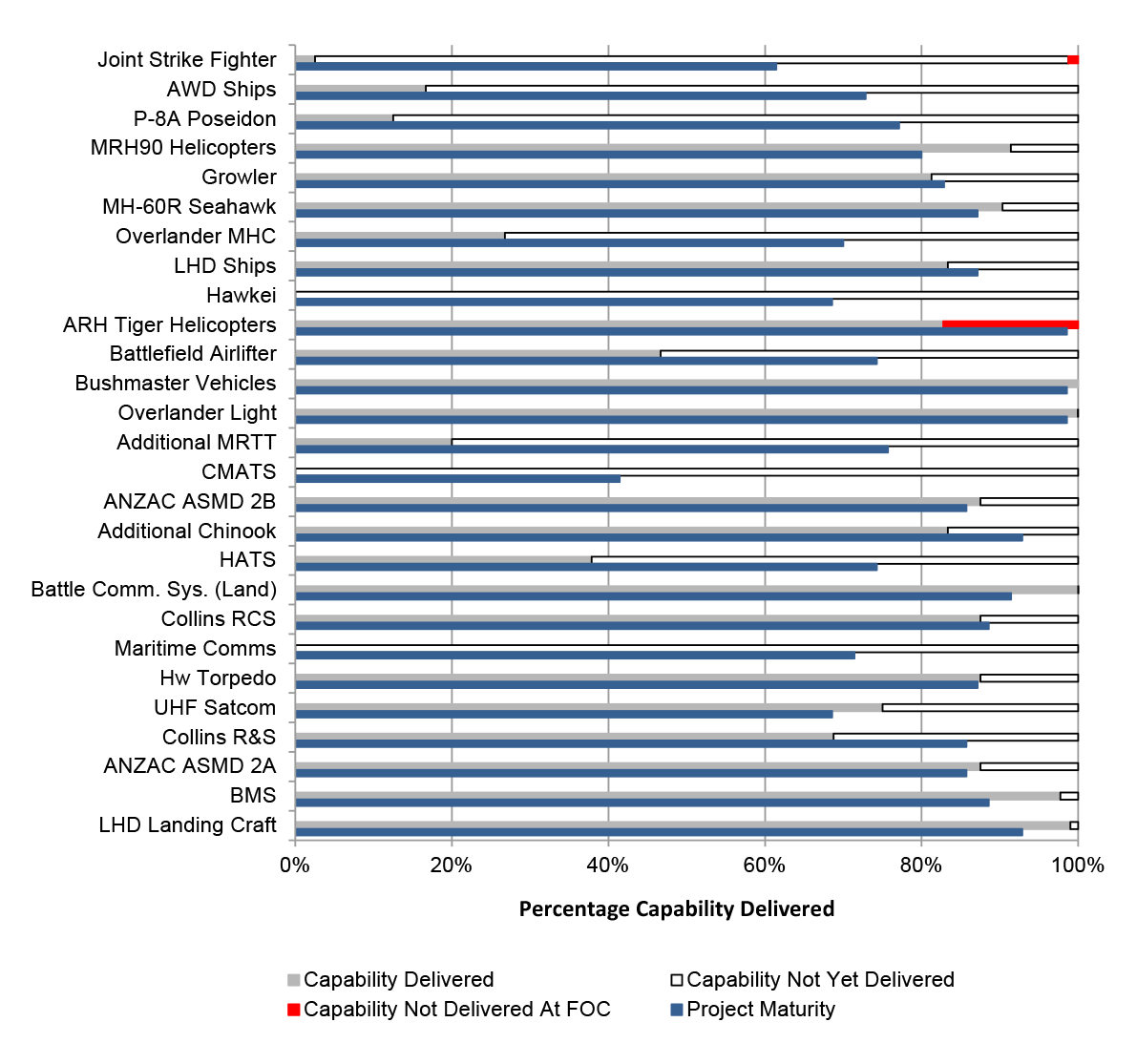

37. The third principal component of project performance examined in this report is progress towards the delivery of capability required by government. While the assessment of expected capability delivery by Defence is outside the scope of the Auditor-General’s formal review conclusion, it is included in the analysis to provide an overall perspective of the three principal components of project performance.

38. The Defence PDSSs report that 23 projects in this year’s report will deliver all of their key capability requirements. Defence’s assessment indicates that some elements of the capability required may be ‘under threat’, but the risk is assessed as ‘manageable’. The three project offices experiencing challenges with expected capability delivery (2015–16: three) are MRH90 Helicopters, Battlefield Airlifter and LHD Landing Craft. One project office (Joint Strike Fighter) is currently unable to deliver all of the required capability by FOC.

39. Defence’s presentation of capability delivery performance in the PDSSs is a forecast and therefore has an element of uncertainty. In 2015–16, the ANAO developed an additional measure of the status of current capability delivery progress to assist the Parliament—Capability Delivery Progress—which is a tally of the capability delivered as at 30 June 2017, as reported by Defence. Tables 6 and 7 below provide two worked examples of the ANAO’s methodology, utilising the performance information provided in the relevant PDSS.

Table 6: Capability Delivery Progress assessment – CMATS

|

Capability elements as per Section 4.2 of the PDSS |

No. of elements approved |

No. of elements delivered at 30 June 2017 |

Comments |

|

Transition of Amberley, East Sale, School of Air Traffic Control and Edinburgh from Australian Defence Air Traffic System (ADATS) to Civil Military Air Traffic Management System (CMATS). |

4 |

0 |

No sites have been transitioned. |

|

Transition of Oakey, Nowra, Tindal, Darwin, Townsville, Williamtown, Pearce, Richmond and Gin Gin from ADATS to CMATS. |

9 |

0 |

No sites have been transitioned. |

|

Total (number) |

13 |

0 |

— |

|

Total (per cent) |

100 |

0 |

— |

Source: PDSSs in published Major Projects Reports and ANAO analysis.

Table 7: Capability Delivery Progress assessment – Bushmaster Vehicles

|

Capability elements as per Section 4.2 of the PDSS |

No. of elements approved |

No. of elements delivered at 30 June 2017 |

Comments |

|

Commencement of delivery of full rate production for Production Period 1 (PP1) vehicles. |

1 |

1 |

All PP1 vehicles have been completed. |

|

Completion of vehicle deliveries for all five production periods as detailed in Section 1.1. |

1 015 |

1 015 |

All vehicles have been delivered. |

|

Total (number) |

1 016 |

1 016 |

— |

|

Total (per cent) |

100 |

100 |

— |

Source: PDSSs in published Major Projects Reports and ANAO analysis.

40. Table 8 below, summarises expected capability delivery as at 30 June 2017—as reported by Defence and using the ANAO’s Capability Delivery Progress measure.

Table 8: Capability delivery

|

Expected Capability |

2014–15 MPR (%) |

2015–16 MPR (%) |

2016–17 MPR (%) |

Capability Delivery Progress |

2016–17 MPR (%) |

2016–17 MPR (%) Adjusted 3 |

|

High Confidence (Green) |

97 |

99 |

98 |

Delivered |

70 |

52 |

|

Under Threat, considered manageable (Amber) |

3 |

1 |

2 |

Not yet delivered |

30 |

46 |

|

Unlikely (Red) |

0 |

0 1 |

0 1 |

Not delivered at FOC 2 |

0 |

2 |

|

Total |

100 |

100 |

100 |

Total |

100 |

100 |

Note 1: Defence has advised that Joint Strike Fighter will not deliver one element of capability at FOC, of a total of 79 elements required for the project (which equates to approximately one per cent). However, across all 27 Major Projects this percentage rounds to zero.

Note 2: In addition, ARH Tiger Helicopters had a small number of elements not delivered at FOC. However, as there is a total of 28 321 elements across all 27 Major Projects, these percentages round to zero.

Note 3: Excluding the six projects with the largest number of elements for delivery (i.e. Overlander Medium/Heavy, Hawkei, Bushmaster Vehicles, Overlander Light, Battle Comm. Sys. (Land), and BMS), results in an increase to the proportion of capability ‘not yet delivered’ to 46 per cent (from 30 per cent) and ‘not delivered at FOC’ to two per cent (from zero per cent). These six projects disproportionately weight the calculation of Capability Delivery Progress due to a large number of physical elements for delivery. These six projects represent 27 876 deliverables out of a total of 28 321 deliverables for all 27 Major Projects.

Source: PDSSs in published Major Projects Reports and ANAO analysis.

41. The ARH Tiger Helicopters platform was provided a caveated FOC and Defence faces ongoing risks and issues in relation to delivering the remaining capabilities.30 It is also impacted by technological obsolescence, related to delays in delivery, which impact future use. The impact of these issues has not translated into Defence’s assessment of future capability delivery performance, although they could reasonably be assumed to have a long term effect on capability. Refer to paragraphs 17 to 25 for further detail.

42. In addition to reporting on expected capability delivery, Defence has continued the practice of including declassified information on settlement actions for projects. Prior settlements for projects within this report related to MRH90 Helicopters, LHD Ships, ARH Tiger Helicopters and Maritime Comms.

1. The Major Projects Review

1.1 This chapter provides an overview of the review’s scope and approach, as implemented by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO), for the review of the 27 Project Data Summary Sheets (PDSSs) prepared by the Department of Defence (Defence). This chapter also provides the results of the Major Projects Report (MPR) review.

Review scope and approach

1.2 In 2012 the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) identified the review of the PDSSs as a priority assurance review, under section 19A(5) of the Auditor-General Act 1997 (the Act). This provided the ANAO with full access to the information gathering powers under the Act. The ANAO’s review of the individual project PDSSs, which are reproduced in Part 3 of this report, was conducted in accordance with the auditing standards set by the Auditor-General under section 24 of the Auditor-General Act 1997 through its incorporation of the Australian Standard on Assurance Engagements (ASAE) 3000 Assurance Engagements Other than Audits or Reviews of Historical Financial Information, issued by the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards Board.

1.3 The following forecast information is excluded from the scope of the ANAO’s review: capability delivery, risks and issues, and forecast dates. These exclusions are due to the lack of Defence systems from which to provide complete and accurate evidence31, in a sufficiently timely manner to complete the review. Accordingly, the Independent Assurance Report by the Auditor-General does not provide any assurance in relation to this information. However, material inconsistencies identified in relation to this information, are required to be considered in forming the conclusion.

1.4 The ANAO’s work is appropriate for the purpose of providing an Independent Assurance Report in accordance with the above auditing standard. However, the review of individual PDSSs is not as extensive as individual performance and financial statement audits conducted by the ANAO, in terms of the nature and scope of issues covered, and the extent to which evidence is required by the ANAO. Consequently, the level of assurance provided by this review, in relation to the 27 major Defence equipment acquisition projects (Major Projects), is less than that provided by the ANAO’s program of audits.

1.5 Separately, the ANAO undertakes analysis of key elements of the PDSSs and examines systemic issues and provides longitudinal analysis for the 27 projects reviewed.

1.6 The review was conducted in accordance with the ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $1.8 million.

Review methodology

1.7 The ANAO’s review of the information presented in the individual PDSSs included:

- examination and assessment of the governance and oversight in place to ensure appropriate project management;

- an assessment of the systems and controls that support project financial management, risk management, and project status reporting, within Defence;

- an examination of each PDSS and the documents and information relevant to them;

- a review of relevant processes and procedures used by Defence in the preparation of the PDSSs;

- interviews with persons responsible for the preparation of the PDSSs and management of the projects;

- analysis of project information, for example, cost and schedule variances;

- taking account of industry contractor comments provided on draft PDSS information;

- assessing the assurance by Defence managers attesting to the accuracy and completeness of the PDSSs;

- examination of the representations by the Chief Finance Officer supporting the project financial assurance and contingency statements, and the independent third-party assessment of the project financial assurance statements (commissioned by Defence);

- examination of confirmations, provided by the Capability Managers, relating to each project’s progress toward Initial Materiel Release (IMR), Final Materiel Release (FMR), Initial Operational Capability (IOC) and Final Operational Capability (FOC); and

- examination of the ‘Statement by the Secretary of Defence’, including significant events occurring post 30 June, and management representations by the Secretary of Defence.

1.8 The ANAO’s review of PDSSs also focused on project management and reporting arrangements contributing to the overall governance of the Major Projects. The ANAO considered:

- resolution of matters described in the Auditor-General’s prior year (2015–16) qualified Independent Assurance Report, relating to the ARH Tiger Helicopter PDSS and the LHD Landing Craft PDSS32;

- developments in acquisition governance (Chapter 1 in Part 1, below);

- the financial framework, particularly as it applies to the project financial assurance and contingency statements, and managing project budgets in the out-turned budget environment (Section 2 of the PDSSs);

- schedule management and test and evaluation processes (Section 3 of the PDSSs);

- capability assessments, including Defence statements of the likelihood of delivering key capabilities, particularly where caveats are placed on the Capability Manager’s declaration of significant milestones (Section 4 of the PDSSs);

- the ongoing review of the maturity of the Enterprise Risk Management Framework (currently undergoing reform), and the completeness and accuracy of major risk and issue data in order to pilot bringing risks and issues into the scope of the Independent Assurance Report in the 2018–19 MPR (Section 5 of the PDSSs);

- the project maturity framework along with its related reporting and the systems in place to support the consistent and accurate application and the provision of this data (Section 6 of the PDSSs); and

- the impact of acquisition issues on sustainment to ensure the PDSS is a complete and accurate representation.

1.9 This review informed the ANAO’s understanding of the systems and processes supporting the PDSSs for the 2016–17 review period. It also highlighted issues in those systems and processes that warrant attention.

Developments in acquisition governance

1.10 Consistent with previous years, key developments in acquisition governance processes are covered in the ANAO’s review in order to inform the planning process. While some initiatives are mature, others require further progress prior to achieving their intended impact.

Independent Assurance Review Boards

1.11 First introduced in 2008, the Gate Review (acquisition) process33 was designed to provide the Defence Senior Executive with assurance that all identified risks for a project are manageable, and that costs and schedule are likely to be under control prior to a project passing through the various stages of its life cycle. Gate Reviews were introduced for sustainment in 2013–14.

1.12 Since July 2016, Gate Reviews have been referred to as Independent Assurance Reviews34, with corporate policies and procedures updated for the revised processes under the modified Capability Life Cycle. The process has also introduced a contestability function, to focus on project business cases prior to government approval. Sixteen of the projects included in this report had an Independent Assurance Review conducted during 2016–1735, which formed key corroborative evidence for the ANAO’s review.

1.13 Defence advised in November 2017 that ‘Gate Review’ is now a description for a separate process that leads to Gate submission (to the Investment Committee) including the CASG Independent Assurance Review and the Capability Manager Gate Review.

Projects of Concern

1.14 First established in 2008, the Projects of Concern process was implemented to focus the attention of the highest levels of government, Defence and industry on remediating problem projects. The process has continued to play a role across the portfolio of MPR projects. As at 30 June 2017, two MPR projects were continuing projects of concern:

43. AWD Ships, a project of concern since June 2014, due to increasing commercial, schedule and cost risks, including difficulties and delays in shipbuilding36; and

44. MRH90 Helicopters, a project of concern since November 2011, due to technical issues preventing the achievement of milestones on schedule.37

1.15 In August 2017, the Ministers for Defence and Defence Industry announced38 that the Civil Military Air Traffic Management System (CMATS) project was being placed on the list due to substantial challenges getting into contract.39 The challenges revolve around issues with ensuring value for money for the taxpayer.

Quarterly Performance Report

1.16 The Quarterly Performance Report (QPR) introduced in 2014, aims to provide senior stakeholders within government and Defence with a clear and timely understanding of emerging risks and issues in the delivery of capability to the Australian Defence Force’s end-users.40 Defence has advised that the report is provided to the Minister for Defence and the Minister for Defence Industry on a quarterly basis, with reports starting to cover the broader remit of the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG) deliverables, as recommended by the First Principles Review.41

1.17 In 2016–17, further to the two MPR projects of concern noted above, the June 2017 QPR also identified five MPR projects as Projects of Interest42:

- Joint Strike Fighter, due to the inability to deliver one element of capability required for FOC;

- LHD Ships, due to propulsion issues and other system defects, which have impacted on the forecast dates for FMR and FOC;

- CMATS, due to ongoing contract negotiations and the request for approval of a Real Cost Increase (this project has since been declared a Project of Concern);

- Battle Comm. Sys. (Land), due to additional validation and verification requirements not originally captured in the schedule, which have impacted on the forecast dates for FMR and FOC; and

- UHF SATCOM, due to issues with the modification of Commercial Off-The-Shelf software (an element of the project now considered developmental) and delays in the security accreditation process.

1.18 The ongoing issues highlighted above for Joint Strike Fighter, LHD Ships, CMATS, Battle Comm. Sys. (Land) and UHF SATCOM align with the results of the ANAO’s review. Delays to progress have impacted the delivery schedule of four43 of these projects (see Table 4, on page 12).

Joint Project Directives and Materiel Acquisition Agreements

1.19 The longstanding issue for Defence in maintaining complete and accurate records of government approvals for Major Projects, led to the introduction of Joint Project Directives (JPDs) (from March 2010).44 JPDs state the terms of government approval and are used to inform internal documentation such as Materiel Acquisition Agreements (MAAs)45 between CASG and the Service Chiefs.46

1.20 However, the initiative started slowly, with Defence taking over two years to begin to produce the first JPDs.47 Further, JPDs are regularly finalised after the MAAs they are intended to inform and, as a result, care is required to ensure that JPDs properly reflect the relevant government decision, and that MAAs are appropriately aligned with the relevant JPD.48

1.21 In 2016–17, 15 of the 16 MPR projects approved from 1 March 2010, have completed a JPD.49 However, the ANAO requires access to original approval documents to validate the requirements of projects. At this time, validation based on internal Defence documentation is not always possible.

1.22 The ANAO will continue to take JPDs into account in its review program in future years. However, the extent to which they can be relied upon will be dependent on the completeness and accuracy of JPDs, in relation to recording the detail of government approvals.

1.23 Product Delivery Agreements (PDAs) are being developed to replace the existing MAAs and Materiel Sustainment Agreements (MSAs).50 PDAs will be a higher level document (reviewed annually) that combine the MAA and MSA for each program. In August 2017, Defence advised that the development of the PDA templates was still ongoing.

Business systems rationalisation

1.24 Defence’s business systems rationalisation is aimed at consolidating processes and systems in order to provide a more manageable system environment.51 The Monthly Reporting System (MRS), which provides much of the data for the PDSSs, is to be replaced by the Project Performance Review for acquisition, and the Sustainment Performance Management System for sustainment.52 As reported to the JCPAA on 31 March 2017, Defence stated that there was a ‘need to get a single unified system of accountability and reporting inside the organisation’. Defence intends to rely on interfaces with existing systems, such as Open Plan Professional (OPP – the scheduling tool), rather than create another ‘system’.53

1.25 In September 2017, Defence advised that 33 Defence projects, 15 of which are included in the MPR, are participating in a pilot of the Project Performance Review. The pilot is still in its formative stages and development work and reviews will continue into 2018. Defence has advised that the MRS is still the mandated reporting system and will continue to be used until late 2018. The ANAO will review the progress of the pilot during the next reporting period.

Results of the review

1.26 The following sections outline the results of the ANAO’s review, which inform the overall conclusion in the Independent Assurance Report by the Auditor-General for 2016–17.

Financial framework

1.27 The project financial assurance statements were introduced in the 2011–12 Major Projects Report and have been included within the scope of the Independent Assurance Report by the Auditor-General since 2014–15. The contingency statements were introduced for the first time in the 2013–14 report and these describe the use of contingency funding to mitigate project risks. Together, they are aimed at providing greater transparency over projects’ financial status.

1.28 A project’s total approved budget comprises:

- the allocated budget, which covers the project’s approved activities, as indicated in the MAA; and

- the contingency budget, which is established to provide adequate budget to cover the inherent cost, schedule and technical risks and uncertainties of the in-scope work of the project and any contingency events that may arise during the conduct of a project.54

1.29 In 2016–17, the ANAO reviewed the financial framework as it applied to managing project budgets and expenditure, including: contingency, project financial assurance and the reporting environment.

Project financial assurance statement

1.30 The project financial assurance statement was added to the PDSSs to enhance transparency by providing readers with information on each project’s financial position (in relation to delivering project capability) and whether there is ‘sufficient remaining budget for the project to be completed’.55

1.31 In 2016–17 the CMATS project is seeking approval for a significant Real Cost Increase which is anticipated to be considered by government in February 2018.

1.32 Defence has continued to subject a sample of project financial assurance statements to a third-party agreed-upon procedures engagement. The third party engagement supports Defence in assessing the project financial assurance statements, by reporting on projects’ compliance with an internal Defence instruction issued by the Chief Finance Officer.56

1.33 Projects selected for the 2016–17 third-party engagement, in support of the financial assurance statement assurance process, were:

- additional procedures—Joint Strike Fighter and UHF SATCOM; and

- standard procedures—LHD Ships, Additional MRTT and Battle Comm. Sys. (Land).

1.34 Defence has advised that the third-party engagement ‘found no adverse factual findings that would indicate any financial issues with the PDSS [project financial assurance statements] for the five selected projects’.

1.35 In conclusion, for the 2016–17 Major Projects Report, the Acting Chief Finance Officer’s representation letter to the Secretary on the project financial assurance statements was unqualified. The project financial assurance statement is restricted to the current financial contractual obligations of Defence for these projects, including the result of settlement actions and the receipt of any liquidated damages, and current known risks and estimated future expenditure as at 30 June 2017.

Contingency statements and contingency management

1.36 The purpose of the project contingency budget is ‘to provide adequate budget to cover the inherent risk of the in-scope work of the project’.57 Defence policy requires project offices to maintain a contingency budget log to identify and track components of the contingency budget.58

1.37 PDSSs are required to include a statement regarding the application of contingency funds during the year, if applicable, as well as disclosing the risks mitigated by the application of those contingency funds. Defence’s Project Risk Management Manual (PRMM version 2.4, page 110) requires that contingency be applied for identified risk mitigation activities which have been assessed as being cost effective and representing value for money.

1.38 The five project offices which had contingency funds applied in 2016–17 were MRH90 Helicopters (supportability and performance risks), ANZAC ASMD 2A and 2B (gain share, combat management system, dockyard facilities and training facilities), Additional Chinook (building upgrade, missile warning system, improved vibration control and improved seating), and UHF SATCOM (software review and system security).

1.39 The ANAO’s examination of the contingency statements as at 30 June 2017 also highlighted that:

- the clarity of the relationship between contingency application and identified risks continues to be an issue. Of the 25 project offices that have a formal contingency allocation59, eight projects (Joint Strike Fighter, P-8A Poseidon, LHD Ships, Hawkei, CMATS, ANZAC ASMD 2B, UHF SATCOM and ANZAC ASMD 2A) did not explicitly align their contingency log with their risk log, by including risk identification numbers as required by PRMM version 2.4;

- the method for applying contingency varied, with 23 project offices using the ‘expected costs’ of the risk treatment (as required by PRMM version 2.4), with HATS using a proportionate allocation of the likelihood of the risk eventuating (the method outlined in PRMM version 2.2); and

- there were seven project offices that did not meet all the requirements of PRMM version 2.4 in terms of keeping a record of review of contingency logs, however, the ANAO observed that the information required could be located in other documents.

1.40 Non-compliance with PRMM version 2.4 has resulted in inconsistent approaches taken to the management of contingency.

Reporting environment

1.41 Defence advised projects at the start of the year to change reporting of expenditure to a cash basis (previously accrual). This resulted in significant changes to financial disclosures for 14 projects during ANAO site visits. Financial reporting was reverted to an accrual basis at 30 June for the purposes of consistency in reporting across years.60

1.42 Defence prepares, on a cash basis, all financial data related to projects and capital programs provided within the Defence Portfolio Budget Statements, Portfolio Additional Estimates Statements and annual report.61 Therefore financial data in the PDSSs may not be consistent with that reported in the 2016–17 Defence annual report.

1.43 The ANAO also observed that incorrect exchange rates in system-generated commitment reports were used for projects managing contracts in foreign currencies, which meant that contract values had not been calculated correctly and required manual adjustment.

Enterprise Risk Management Framework

1.44 While major risks and issues data in the PDSSs remains excluded from the formal scope of the Auditor-General’s Independent Assurance Report, material inconsistencies identified in relation to this information are required to be detailed in the report.62 The following information is included to provide an overall perspective of how risks and issues are managed within Defence and the selected Major Projects.

1.45 Risk management has been a focus of the MPR since its inception. The CASG risk management environment consists of multiple policies and varying implementation mechanisms and documentation. There are multiple group-level (i.e. CASG), sub-group (i.e. Divisional) and project-level risk management documents. The primary focus of the ANAO’s examination of risk management is at the project level, in order to assure the PDSS.

1.46 The ANAO first became aware of a comprehensive risk reform being pursued in CASG following the provision of a consultant’s report which responds to recommendations contained in the First Principles Review.63 This report recognises the opportunity for improvement and makes a number of observations, including:

- four of the eight CASG divisions have documented how risk management is conducted;

- there does not appear to be a positive risk culture where risk is appropriately identified, assessed, communicated and managed; and

- ‘a general perception that culture in Defence and more broadly Defence industry was that the truth is not clearly represented or documented in risk reports. The justification and evidence of this, is that risk reports often do not align with reality and the issues that emerge’.

1.47 At the Group level, Deputy Secretary CASG issued a directive in May 2017 establishing a CASG Risk Management Reform Program to implement a risk management model that is situated within Defence’s risk management framework, to be implemented over two years. The first phase of the reform was expected to be completed by September 2017. Defence advised in October 2017 that this is yet to be completed. The ANAO will continue to monitor the implementation of the reform as part of future reviews, but will not be able to consider including risks and issues in scope until the 2018–19 MPR, when the reform is expected to be complete.

1.48 In 2016–17, the ANAO again examined project offices’ risk and issue logs at the Group and Service level, which are predominantly created and maintained utilising spreadsheets and/or Predict! software.64 Overall, the issues with risk management that the ANAO observed related to:

- variable compliance with corporate guidance, for example, five out of 27 Major Projects did not update their Risk Management Plan in line with PRMM version 2.4;

- the visibility of risks and issues when a project is transitioning to sustainment;

- the frequency with which risk and issue logs are reviewed to ensure risks and issues are appropriately managed in a timely manner, and accurately reported to senior management;

- risk management logs and supporting documentation of variable quality, particularly where spreadsheets are being used65; and

- lack of quality control resulting in inconsistent approaches in the recording of issues within Predict!.

1.49 The ANAO has previously observed that Defence’s use of spreadsheets as a primary form of record for risk management is a high risk approach. Spreadsheets lack formalised change/version control and reporting, thereby increasing the risk of error. This can make spreadsheets unreliable corporate data handling tools as accidental or deliberate changes can be made to formulae and data, without there being a record of when, by whom, and what change was made. As a result, a significant amount of quality assurance is necessary to obtain confidence that spreadsheets are complete and accurate at 30 June, which is not an efficient approach. The ANAO’s review of CASG’s 27 project offices indicates that 14 utilise spreadsheets66 as their primary risk management tool, 11 utilise Predict! and one utilises a bespoke SharePoint based tool.67

1.50 Defence advised the JCPAA in March 2017 that there are ‘too many systems and too much variation in the way [Defence] apply risk management in [the] organisation.’68 While some project offices will experience greater challenges with risks and issues administration—often reflecting project complexity, scale and timing—it is important that Defence ensure that risk management systems and processes are used appropriately and consistently with the Defence Enterprise Risk Management framework. This is particularly important for higher cost/risk developmental projects.

Project maturity framework

1.51 Project Maturity Scores have been a feature of the Major Projects Report since its inception in 2007–08. The DMO Project Management Manual 2012, defined a maturity score as:

The quantification, in a simple and communicable manner, of the relative maturity of capital investment projects as they progress through the capability development and acquisition life cycle.69

1.52 Maturity scores are a composite indicator, cumulatively constructed through the assessment and summation of seven different attributes. The attributes are: Schedule, Cost, Requirement, Technical Understanding, Technical Difficulty, Commercial, and Operations and Support, which are assessed on a scale of one to 10.70 Comparing the maturity score against its expected life cycle gate benchmark provides internal and external stakeholders with a useful indication of a project’s progress.

1.53 The ANAO has previously raised inconsistency in the application of Project Maturity Scores as an issue. However this year, Defence has been more consistent in applying this guidance.

1.54 The policy guidance underpinning the attribution of maturity scores would benefit from a review for internal consistency and the relationship to Defence’s contemporary business. For example, allocating approximately 50 per cent of the maturity score at Second Pass Approval, regardless of acquisition type, is often inconsistent with the proportion of project budget expended, and the remaining work required to deliver the project.

1.55 Further, the existing project maturity score model does not always effectively reflect a project’s progress during the often protracted build phase, particularly for developmental projects. During this phase it can be expected that maximum expenditure will occur, and that many risks will be realised, some of which will only emerge as test and evaluation activities are pursued through to acceptance into operational service. For example, the ARH Tiger Helicopters project had capability deficiencies and obsolescence issues at FOC (declared on 14 April 2016), but the maturity score prepared for the 2015–16 MPR did not accurately represent the project’s maturity as at 30 June 2016, and the maturity score prepared for the 2016–17 MPR does not accurately represent the project’s maturity as at 30 June 2017. Refer to paragraphs 17 to 25 for further detail.

1.56 The policy guidance underpinning maturity scores was due for review in September 2012.71 In May 2016, the JCPAA recommended ‘that the Department of Defence work with the Australian National Audit Office to review and revise Defence’s policy regarding Project Maturity Scores in time for the new approach to be implemented in the next Major Projects Report.’72 In response, Defence engaged a contractor to develop a more appropriate methodology to support the presentation of the Project Maturity Score graphs. However, due to the immaturity of the processes and systems referred to, CASG is not yet in a position to test or apply such a methodology and has not proposed an approach to the ANAO.

1.57 In October 2017, the JCPAA recommended ‘that the Department of Defence commence discussions with the Australian National Audit Office on updating Project Maturity Scores, with a view to advising the Committee on a way forward prior to the first sitting week of 2018.’73

Caveats

1.58 In 2016–17, the ANAO noted a continuing trend of Major Projects which have achieved significant milestones with caveats.74 Table 9 below lists the current MPR projects which have achieved a major milestone with caveats.75

Table 9: Caveated projects

|

Project |

Milestone (Year) |

Number of Caveats |

Description |

Status of Caveats (as at 30 June 2017) |

|

Overlander Light |

IMR (2014) and IOC (2015) |

Three |

Capability requirements; |

All resolved |

|

FOC (2016) |

Two |

Capability requirements; |

Unresolved–both lifted in September 2017 |

|

|

Battlefield Airlifter |

IMR and IOC (2016) |

Two |

Supply support deficiencies; |

Unresolved—both lifted in August 2017 |

|

ARH Tiger Helicopters |

FOC (2016) |

Nine |

Capability requirements; |

Unresolved—two lifted in July 2017 |

|

Growler |

IMR (2017) |

One |

Training requirements. |

Unresolved |

Source: PDSSs in published Major Projects Reports and ANAO analysis.

1.59 At JCPAA hearings on 31 March 2017, Defence confirmed that caveats are an infrequent event.76

1.60 The ANAO will continue to monitor the declaration and resolution of caveats in future reviews. Additionally, from 2017–18, projects which have been removed from the MPR which still have outstanding caveats are required to report on the status of these caveats in the Statement by the Secretary of Defence until their final status is accepted by the Capability Manager.77

2. Analysis of Projects’ Performance

2.1 Performance information is important in the management and delivery of major Defence equipment acquisition projects (Major Projects). It informs decisions about the allocation of resources, supports advice to government, and enables stakeholders to assess project progress.

2.2 Project performance has been the subject of many of the reviews of the Department of Defence (Defence), and a consistent area of focus of the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) since the first Major Projects Report (MPR). This chapter progresses previous Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) analysis over project performance.

Project performance analysis by the ANAO

2.3 The ANAO utilises three key performance indicators to analyse the major dimensions of projects’ progress and performance. These indicators are the:

- percentage of budget expended (Budget Expended)—which measures the total expenditure as a percentage of the total current budget;

- percentage of time elapsed (Time Elapsed)—which measures the percentage of time elapsed from original approval to the forecast Final Operational Capability (FOC)78; and

- percentage of key materiel capabilities delivered79 (Capability Delivery Progress)—which measures the total capability elements delivered as a percentage of the total capability elements across all Major Projects.

2.4 The ANAO has previously utilised Defence’s prediction of expected final capability, as reported in Section 4.1 of each Project Data Summary Sheet (PDSS). In 2015–16, the ANAO derived an indicator for ‘Capability Delivery Progress’, which aims to show the current capability delivered, in terms of capability elements included within the agreed Materiel Acquisition Agreements (MAAs). These performance indicators are measured in percentage terms, to enable comparisons between projects of differing scope, and to provide a view across the selected projects of progress and performance.

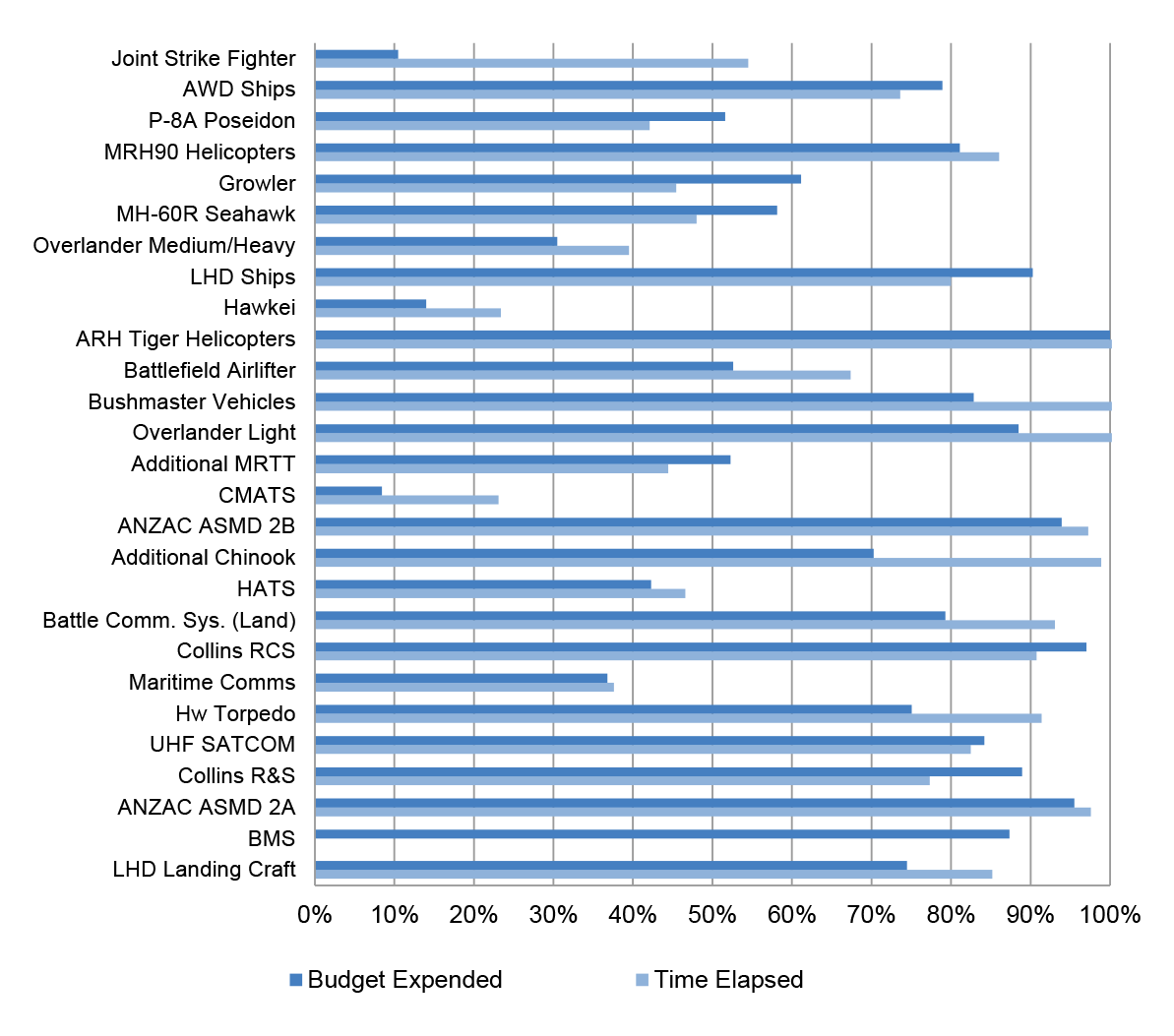

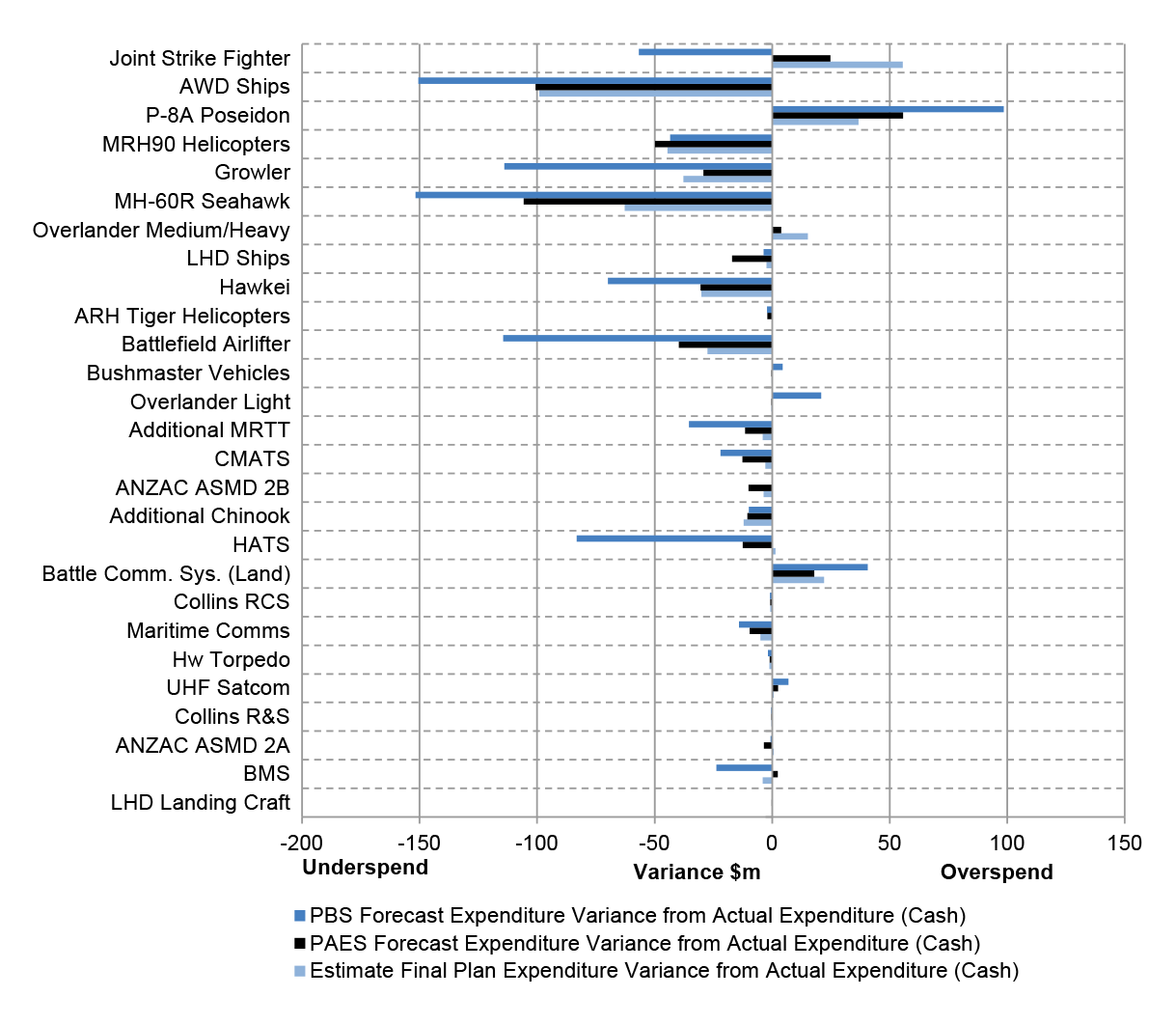

2.5 The following sections of this chapter provide analysis relating to the three principal components of project performance. This includes in-year information, longitudinal analysis and the results of project progress for the year-ended 30 June 2017. The first piece of analysis, in Figure 2 below, sets out each project’s Budget Expended and Time Elapsed.80

Figure 2: Budget Expended and Time Elapsed

Note: BMS does not have IOC or FOC milestones. These were to be linked to Work Packages B-D which received government approval in September 2017 under LAND 200. Work Package A is expected to achieve FMR and MAA closure in quarter one 2018.

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2016–17 PDSSs.

2.6 Figure 2 shows that for most projects (21 of 27), Budget Expended is broadly in line with, or lagging, Time Elapsed.81 This relationship is generally expected in an acquisition environment predominantly based on milestone payments. However, due to the varying complexity, stages and acquisition approaches across the portfolio of projects, further analysis of these simple performance measures is required to provide an overall picture of key variances.

2.7 Where Budget Expended is significantly lagging Time Elapsed the project schedule may be at risk, i.e. expenditure lags may indicate delays in milestone achievement. However this is not the case for the two projects where the Budget Expended is over 20 per cent less than the Time Elapsed in 2016–17, as detailed below:

- Joint Strike Fighter (Budget Expended 10 per cent, Time Elapsed 54 per cent)—a large scope increase ($10.5 billion) for the purchase of additional aircraft was approved in April 2014, with the project yet to enter into main production contracts, as aircraft development continues; and

- Additional Chinook (Budget Expended 70 per cent, Time Elapsed 99 per cent)—the variance reflects cost savings achieved through the integration of a number of previously post production modifications (including some of the Australian unique modifications) on the production line and progressive price reductions in the Foreign Military Sales (FMS) case.

2.8 Where Budget Expended leads Time Elapsed the project budget may be at risk, i.e. expenditure increases may indicate real cost increases. However, for the five projects where Budget Expended leads Time Elapsed by 10 per cent or more, the actual reasons are related either to early procurement of major equipment due to production timing, or schedule delays caused through platform availability, as detailed below:

- P-8A Poseidon (Budget Expended 52 per cent, Time Elapsed 42 per cent)—most of the expenditure on equipment is in line with aircraft production over the coming three financial years. Three aircraft have now been delivered to Defence.

- Growler (Budget Expended 61 per cent, Time Elapsed 45 per cent)—expenditure reflects aircraft production costs (which represent a large proportion of project costs) having occurred before a large decrease in annual expenditure over the following years as work continues on the Mobile Threat Training Emitter System. All aircraft have now been delivered to Defence. The variance is also exacerbated by the length of time between Initial Operational Capability (IOC) (July 2018) and FOC (June 2022) with most of the major equipment being delivered by 2018.

- MH-60R Seahawk (Budget Expended 58 per cent, Time Elapsed 48 per cent)—the project has taken delivery of all 24 aircraft. The variance is caused by the time between final aircraft delivery and FOC, which is being used to implement Australian unique modifications and modify navy vessels to operate with the MH-60R Seahawk.

- LHD Ships (Budget Expended 90 per cent, Time Elapsed 80 per cent)—most of the budget has been expended. The Final Materiel Release (FMR) and FOC milestones have been further delayed in 2016–17 due to the unavailability of the LHD Ships to conduct operational test and evaluation activities as a result of issues with the propulsion pods and ongoing remediation of other systems.

- Collins R&S (Budget Expended 89 per cent, Time Elapsed 77 per cent)—most of the materiel has been acquired and expenditure undertaken. In addition, originally planned installation dates have been extended based on submarine availability, reducing the proportion of time elapsed.

2.9 In each case, the performance information highlights projects requiring further attention. This is to ensure that surplus funds are returned to the Defence budget for re-allocation in a timely manner, the timing of key deliverables remains in focus, or planning focuses on bringing together all elements in a timely manner, as equipment is delivered.

Cost performance analysis

Sustainment reporting in the Major Projects Report

2.10 Historically, the majority of projects within the MPR have not been required to disclose significant detail in relation to sustainment activity to meet the requirements of the MPR Guidelines. However, the practice of providing caveated achievement of IOC or FOC provides for advancement through the process of acceptance into operational service, notwithstanding known shortcomings.

2.11 The practice of issuing caveated milestones will require Defence to exercise appropriate judgement for the capability disclosures within the MPR, in order to prepare project PDSSs that provide an accurate depiction of performance to readers of the PDSS while also ensuring that classified data is prepared in such a way as to allow for unclassified publication. Additionally, the ANAO may need to monitor and report on projects ‘in sustainment’, when projects complete tasks defined, and funded, for delivery in acquisition.

- For example, the ARH Tiger Helicopters acquisition received caveated FOC and requires additional funding to address outstanding issues. The ANAO’s performance audit82 identified that the funding required to remediate the ARH Tiger Helicopters was beyond the scope of the already approved $2 033.0 million for the acquisition project. Expert analysis commissioned by Defence indicates that the issues arising from the developmental nature of the ARH Tiger Helicopter platform and sub-optimal sustainment arrangements will endure.83

2.12 The JCPAA agreed to removing the ARH Tiger Helicopters project from the 2017–18 MPR, instead requiring that the status of projects achieving FMR/FOC with caveats be reported in the Statement by the Secretary of Defence until their final status is accepted by the Capability Manager.

2.13 The practice of Defence issuing caveats to milestones is discussed further in Chapter 1, in paragraphs 1.58 to 1.60.

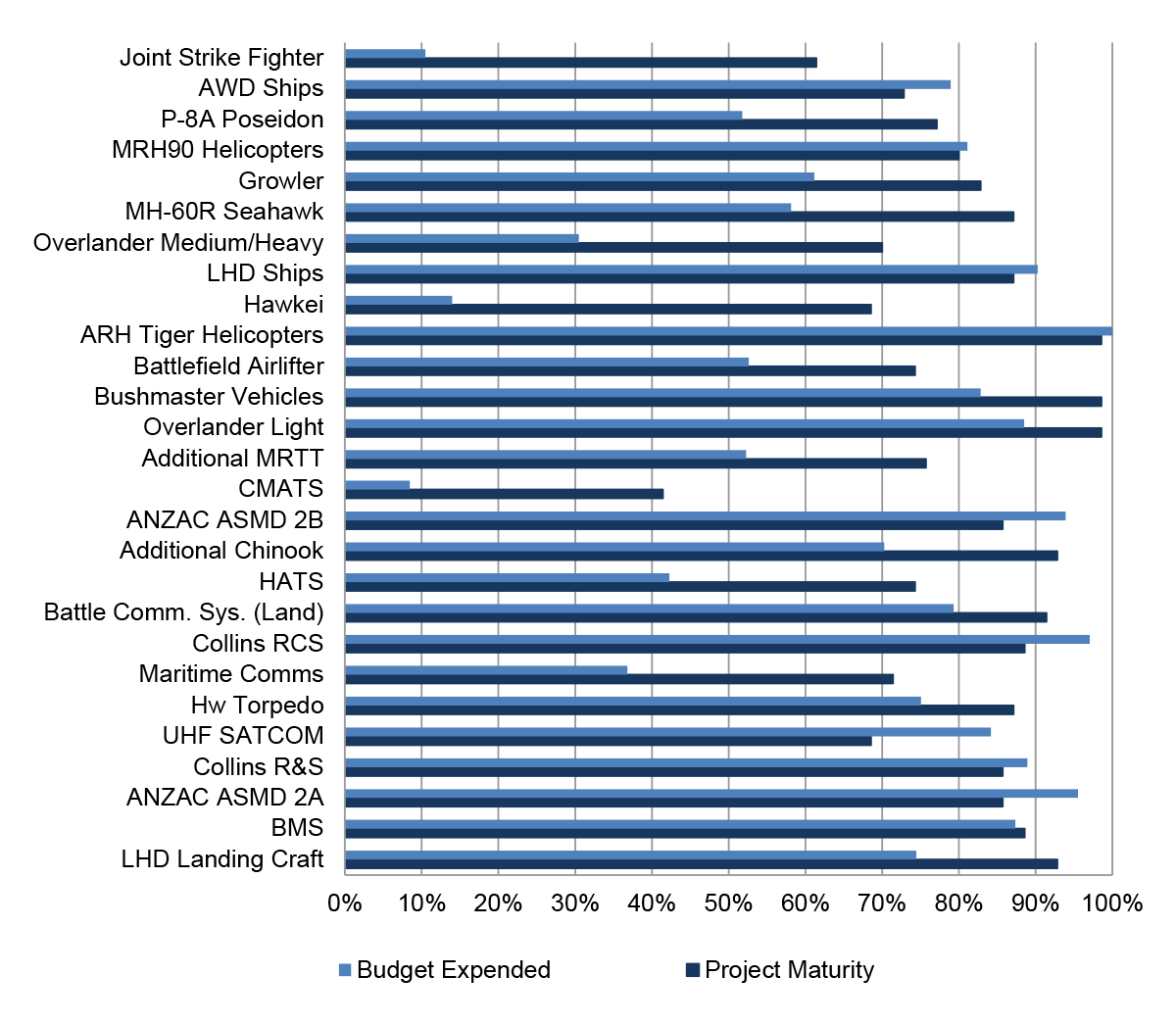

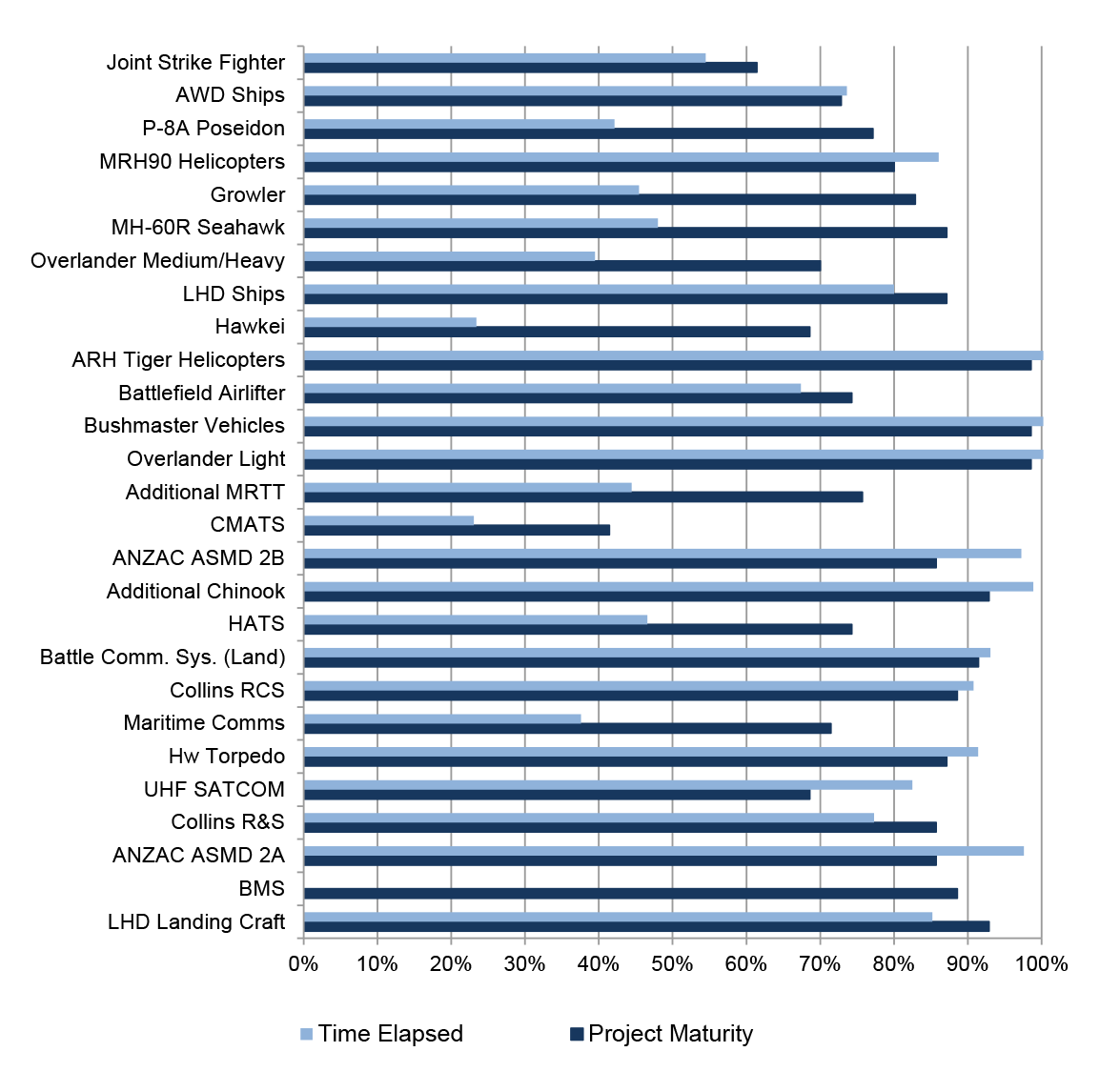

Budget Expended and Project Maturity

2.14 Figure 3, below, sets out each project’s Budget Expended against Project Maturity84 and shows that Budget Expended lags Project Maturity for the majority of projects (18 of 27). This relationship is expected for two reasons:

- in an acquisition environment predominantly based on milestone payments, projects will typically develop confidence in delivering their scope through testing and demonstration, ahead of formal acceptance of milestone achievement (and expenditure of budget); and

- where there is a larger proportion of Military Off-The-Shelf (MOTS) projects. MOTS products are generally in-service with other military forces, and will generally have benefited from significant development and testing, prior to selection by Defence, resulting in a higher level Project Maturity score.

2.15 Budget Expended lags Project Maturity with a variance of 20 per cent or more in 12 projects. As expected, these projects are generally classified as either MOTS or Australianised MOTS. The exceptions are Joint Strike Fighter, which is expected to be classified as MOTS by the time of aircraft delivery; Hawkei, which is still conducting testing and other reviews prior to the start of full-rate production; and CMATS, which remains in negotiation with the prime contractor ahead of signing the main acquisition contract. There are no instances where Budget Expended leads Project Maturity by 20 per cent or more.

2.16 The variances are, in part, the result of Defence’s project maturity framework attributing approximately 50 per cent of total Project Maturity at Second Pass Approval (the main investment decision by government).85 This reduces the value of project maturity assessments during the early stages of acquisition.

2.17 Defence’s focus on typically lower risk MOTS acquisitions in recent years, has assisted in meeting schedule timelines across projects.86 Analysis of the available performance information highlights that the selection of MOTS projects assists in reducing risk during project acquisition, where Project Maturity is more advanced at Second Pass Approval than developmental projects.

Figure 3: Budget Expended and Project Maturity

Note: ANZAC ASMD 2B’s Project Maturity is based on the progress of the lead ship, not on the current eight ship program.

Source: ANAO analysis of the 2016–17 PDSSs.

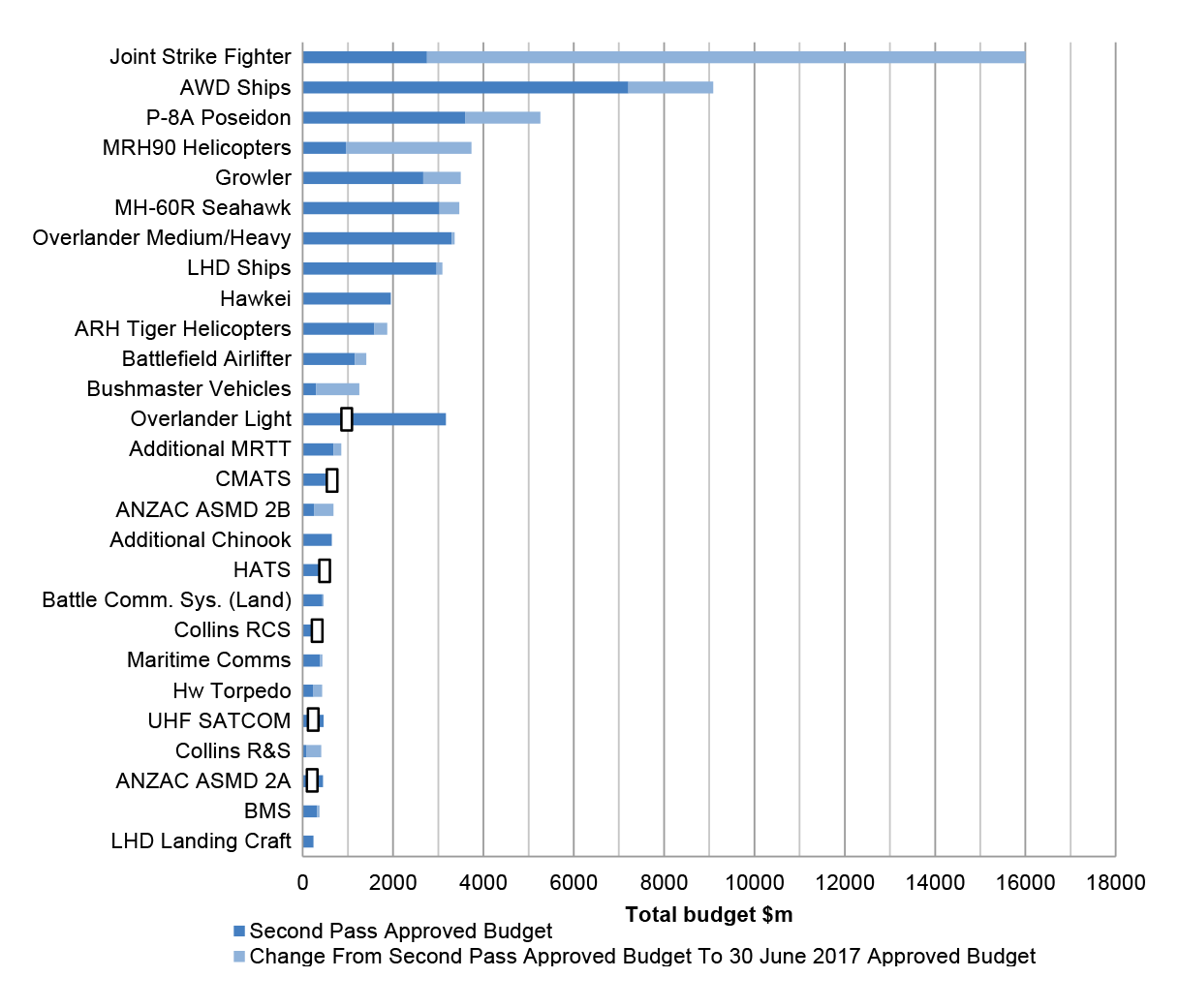

Second Pass Approval and 30 June 2017 approved budget

2.18 Figure 4, below, compares each project’s approved budget at Second Pass Approval and its approved budget at 30 June 2017.

2.19 The total budget for the 27 projects at 30 June 2017 was $62.0 billion, a net increase of $21.5 billion, when compared to the approved budget at Second Pass Approval of $40.5 billion (detailed analysis of this variance is included in Table 3, on page 11).

2.20 Figure 4 indicates relative budget variations from Second Pass Approval of $500 million or more for six projects. The list below describes the components of these variations:

- Joint Strike Fighter—increase of $13.3 billion, comprising $10.5 billion for 58 additional aircraft in 2013–14, $2.4 billion for exchange rate variation and $0.4 billion for price indexation;