Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Defence’s Management of Materiel Sustainment

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess whether Defence has a fit-for-purpose framework for the management of materiel sustainment.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Defence materiel sustainment is about the maintenance and support of Defence’s fleets of specialist military equipment: the provision of in-service support for naval, military and air platforms, fleets and systems operated by Defence. Effective sustainment of naval, military and air assets is essential to the preparedness of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) and to enable Defence to conduct operations. Defence spends similar amounts each year on sustainment and the acquisition of new equipment. In 2015–16, Defence spent $6.3 billion—21 per cent of its total departmental expenditure—on the sustainment of specialist military equipment.

2. Parliamentary committees have frequently stated an interest in Defence’s reporting of its sustainment performance and, in particular, obtaining greater insight into that performance. During the course of this audit the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) announced that it had commenced an inquiry into Defence sustainment expenditure.

3. Part of the context for this audit is to inform the Parliament regarding Defence’s approach to managing sustainment expenditure, including in the context of the current JCPAA inquiry, and to inform the ANAO’s future program in this area.

Audit objective and criteria

4. The objective of the audit was to assess whether Defence has a fit-for-purpose framework for the management of materiel sustainment. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Defence has established an appropriate governance and operational framework for the management of materiel sustainment;

- Defence has established and implemented a high quality performance framework to support the management and external scrutiny of materiel sustainment; and

- Defence has achieved key outcomes expected from the Smart Sustainment reforms and has progressed its implementation of the reforms to sustainment flowing from the First Principles Review.

Conclusion

5. The fundamentals of Defence’s governance and organisational framework for the management of materiel sustainment are fit-for-purpose. However, Defence continues to address specific operational shortcomings and there remains scope for Defence to improve its performance monitoring, reporting and evaluation activities to better support the management and external scrutiny of materiel sustainment.

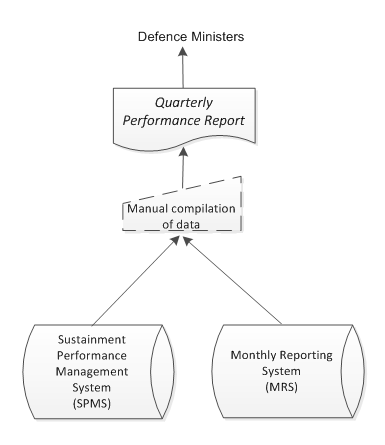

6. Defence has clear and long-standing governance and organisational arrangements for managing the sustainment of specialist military equipment.

7. Research and reviews conducted for Defence have revealed a range of specific operational problems that are detracting from the efficient and effective sustainment of Defence capability, including the functioning of Systems Program Offices. Defence has initiated a reform project as part of its First Principles Review implementation.

8. The development of an effective sustainment monitoring system remains a work in progress, and the effectiveness of Defence’s internal reporting system for sustainment could be improved in several areas. Opportunities also remain to increase the completeness and transparency of publicly reported information regarding materiel sustainment.

9. The 2015 First Principles Review was preceded by earlier major reform initiatives, notably the Strategic Reform Program (SRP) begun in 2009. Defence records show that the department made substantial efforts to keep track of the large number of diverse initiatives identified across the department under the ‘smart sustainment’ reforms associated with the SRP, including internal reporting to management. However, Defence did not adequately assess the outcomes from the ‘smart sustainment’ reforms.

10. Reforms to the management of sustainment flowing from the First Principles Review remain at an early stage, and this stream of activity is likely to take much longer than the expected two years. For example, the Systems Program Office reviews are not yet complete and Defence has provided no evidence that decisions have been taken on changes to their structure and functioning.

11. Defence has engaged industry expertise to guide and help it with the First Principles reforms relating to acquisition and sustainment, including $107 million with a single company where the contract for services is not performance-based. Reform is expected to lead to greater outsourcing of functions currently performed in-house by Defence’s Systems Program Offices.

Supporting findings

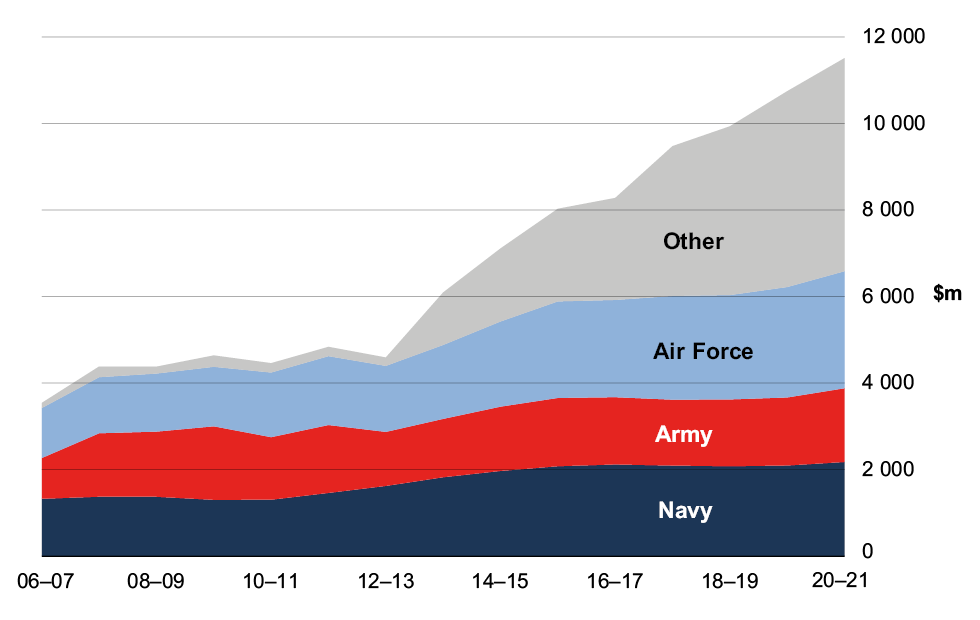

Defence’s governance and operational framework for the management of materiel sustainment

12. Defence has clear and long-standing arrangements for managing the sustainment of specialist military equipment. Key elements of the governance and organisational framework include: a specialist organisational unit—currently the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group—staffed by a mix of civilian and military personnel; contract-like arrangements for sustainment between that unit and the Chiefs of Navy, Army and Air Force (Defence’s Capability Managers); and day-to-day responsibility for most sustainment activities falling to Systems Program Offices, which carry out that work using a mix of in-sourced and out-sourced service provision. Military units also undertake some operational-level sustainment activities.

13. Nevertheless, an internal review conducted by Defence and research conducted for Defence following the 2015 First Principles Review have identified a range of operational problems that detract from the efficient and effective sustainment of Defence capability, including: adherence to procurement principles; staff capabilities; duplication of effort and transparency of internal costs. A project to reform and consolidate Systems Program Offices is currently underway, with 24 out of 64 Systems Program Offices (37.5 per cent) reviewed as at February 2017.

Defence’s performance framework for materiel sustainment

14. With the introduction of its Sustainment Performance Management System (SPMS), Defence continues to develop a basis for an effective monitoring system for sustainment. Once fully implemented this system should be capable of systematically reporting against a suite of performance indicators settled in agreement with Capability Managers.

15. There remains potential to improve some core key performance indicators used within the system—for example, to more usefully determine the total cost of the capability to Defence. The SPMS system was not fully implemented during audit fieldwork but is expected to be fully operational by the end of June 2017. In the longer term the system is to be expanded to cover acquisition.

16. The effectiveness of Defence’s internal reporting system for sustainment could be improved in several areas. The Quarterly Performance Report is the primary way by which Defence provides information to government and senior Defence personnel about the status of major acquisition and sustainment activities. However, based on the ANAO’s review of a Quarterly Performance Report produced during the audit, its contents are neither complete nor reliable, it takes two months to produce and its contents are sometimes difficult to understand. The ANAO’s analysis found that the report may not include additional information available to Defence that is critical to the reader’s ability to understand the status of significant military platforms. It provides only a partial account of materiel sustainment within Defence and is potentially at odds with the ‘One Defence’ model promoted by the First Principles Review. The ANAO has recommended that Defence institute a risk-based quality assurance process for information included in the Quarterly Performance Report.

17. Defence conducts reviews of sustainment performance through sustainment gate reviews that help Defence to obtain insight into a project or product’s progress and status. The effectiveness of these reviews could be increased if the lessons obtained from gate reviews were routinely incorporated into management reporting on sustainment and if gate reviews were extended to contribute to the proposed quality assurance mechanism for Quarterly Performance Reports.

18. Defence has not implemented measures of efficiency and productivity for all sustainment products. Reviews have consistently emphasised the need for Defence to improve the efficiency of its operations, including in sustainment. Most recently, the First Principles Review recommended immediate implementation of measures of productivity, a related concept. The ANAO found that, 18 months after implementation commenced, there had been limited progress.

19. Defence has recently improved its whole-of-life costing of proposals to acquire major capital equipment but remains unable to measure or report reliably the total cost of ownership. It is now planning to implement a new model, which seeks to capture the full cost of ownership throughout the life of an asset, with implementation planned for completion in July 2018. The First Principles Review has pointed out that Defence has treated Systems Program Office staff costs at the project level as a free good, reducing the transparency of the cost of sustainment work and providing inaccurate price signals and a distorted incentive structure to Capability Managers.

20. Opportunities remain to improve the quality and transparency of Defence’s publicly reported information regarding materiel sustainment, while being sensitive to national security concerns. Areas for improvement include:

- achieving a clearer line of sight between planning and reporting documents—for both expenditure and descriptive information at the corporate and project levels; and

- the use of consistent time series data and analysis of sustainment expenditure.

21. Defence’s second corporate plan prepared under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (PGPA Act) identifies sustainment more clearly than in the first corporate plan. Under the PGPA Act, Defence will need to report meaningfully against this plan in its annual performance statement.

22. Defence’s 2015–16 public reporting of sustainment activity included expenditure information and other descriptive material. However, it was not: complete; consolidated in one easy to locate area; prepared in a manner which permitted the comparison of actual expenditure against estimates; or consistent in its presentation of clear reasons for full-year variances. Further, performance summaries were highly variable and inconsistent between public planning documents—Defence’s Portfolio Budget Statements and Portfolio Additional Estimates Statements—and the Annual Report.

23. Defence has not published program level expenditure data on a consistent basis over time, or time series analysis, to assist with external scrutiny of its sustainment expenditure.

Smart Sustainment reforms

24. There is no record of whether the intended savings to sustainment costs were achieved from the Defence Materiel Organisation’s (DMO) 2008 initiative to identify efficiencies. A target expenditure cut of five per cent of sustainment costs over a financial year was set by the Chief Executive Officer of the DMO in February 2008. Defence expected savings from: reducing spares; making more use of performance-based contracting; discouraging unnecessary end-of-year spending; travel efficiencies and improved maintenance philosophies.

25. Defence has not kept a systematic record of the outcomes of the Smart Sustainment initiative associated with the 2009 Strategic Reform Program. In 2011, a ‘health check’ by external consultants found some early successes with cost reductions and changes in practice. Nevertheless, the consultants considered the program was failing because of shortcomings in governance, program management, and Defence’s approach to reform described by a major vendor as ‘minor reform, driven by piecemeal, top down budget pressure’.

26. Smart Sustainment had a ten-year savings target of $5.5 billion. In its 2014–15 Annual Report, Defence claimed to have achieved $2 billion of savings from the initiative in its first five years. Defence has not been able to provide the ANAO with adequate evidence to support this claim, nor an account of how $360 million allocated as ‘seed funding’ for Smart Sustainment initiatives was used.

Materiel sustainment reform—First Principles Review

27. Defence has drawn heavily on contracted industry expertise to support its implementation of the program of organisational change relating to acquisition and sustainment that has followed the First Principles Review. This represents a major investment of at least $120 million, including contracts for services from the principal provider (Bechtel) valued at some $107 million. Contracts with the principal provider are not performance-based.

28. Systems Program Office consolidation and reform is one of the largest reforms to Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group deriving from the 2015 First Principles Review. This stream of activity is likely to take much longer than the two years expected for implementation. In June 2017, Defence advised the ANAO that implementation plans for significant reforms to Systems Program Offices would be developed in the second half of 2017.

29. Other reforms flowing from the First Principles Review remain underway:

- Introducing performance-based contracting into Defence sustainment has been underway for over a decade. Defence does not yet have a completed register of its acquisition and sustainment contracts though, since January 2016, it has had a facility in place and had commenced populating it.

- Initial establishment of ‘centres of expertise’ in Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group is underway. Defence expects full implementation to take a further two years. Similarly, the new Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group Business Framework is expected to take ‘many years’ to fully implement.

- Defence has developed its own meaning for the term ‘smart buyer’, which does not clearly articulate the intent of the First Principles Review recommendation. This introduces risks related to ensuring that Systems Program Office staff working on outsourcing have the necessary skills and competencies.

30. Defence has also been developing its approach to asset management over many years, having obtained substantial advice from internal and external sources to adopt a Defence-wide asset management strategy to underpin a sustainment business mode for specialist military equipment. It is now not clear whether Defence will continue with this work.

31. Defence has not put in place plans to evaluate either the reforms themselves or its implementation of them. There is a risk that insights into a very substantial reform process could be lost. This was the case with the earlier Smart Sustainment reforms. The ANAO has recommended that Defence develop and implement an evaluation plan.

Parliamentary interest

32. In light of the Parliamentary interest in Defence sustainment (see paragraph 1.4 forward) the ANAO has considered, on the basis of the current audit’s findings, the issue of enhanced scrutiny of sustainment through a process similar to the existing Major Projects Report (MPR).1 The MPR has been prepared annually over the last decade to provide independent assurance of the status of selected Defence major acquisition projects. The MPR has added value through the review process and the transparency of information providing increased assurance to the Parliament and the Government. This has been achieved while managing risks to national security.2

33. A key step in the MPR process is the preparation of a Project Data Summary Sheet for each project being reviewed. It is apparent from this audit that Defence has developed information systems that could support the preparation of similar information for its sustainment work. Defence has undertaken work on performance measures for sustainment and has developed the infrastructure to collect and report on its sustainment work (see Chapter 3).

34. Three principal issues remain for the conduct of a process for sustainment parallel to the MPR for acquisition:

- First, the effective management of risks to national security which can arise with the exposure of details of the readiness and availability of Defence capability. This issue could be managed provided the scope of any sustainment review is appropriately selected. For example, a small number of products could be selected, with rotation or other variation from year-to-year, limiting the risks that may flow from time-series analysis and the release of other material whose aggregation could add risk.3

- Second, the material to be produced for scrutiny of sustainment performance would need to reflect a ‘One Defence’ (that is, whole of portfolio) view. As noted in this audit report, the focus of some current arrangements requires clarification as it may reflect only the performance of Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group.

- A final consideration is that of resourcing. In setting the scope and methodology of any review of sustainment performance, the costs and benefits of the proposed program of work and its relationship to existing scrutiny arrangements would need to be considered, both for Defence and for the ANAO.

35. The ANAO has also observed in Chapter 3 of this audit report that there is scope to improve the quality and transparency of public reporting on sustainment in existing Defence reports—the Portfolio Budget Statements, Portfolio Additional Estimates Statements and Defence Annual Report.

Recommendations

Recommendation no.1

Paragraph 3.27

The ANAO recommends that Defence institutes a risk-based quality assurance process for the information included in the Defence Quarterly Performance Report.

Defence response: Agreed

Recommendation no.2

Paragraph 5.66

The ANAO recommends that Defence develop and implement an evaluation plan to assess the implementation of the recommendations of the First Principles Review.

Defence response: Agreed

Entity response

The Department of Defence welcomes the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) performance audit on Defence’s management of materiel sustainment. Defence’s comments, and suggested editorial amendments, have been provided to the ANAO.

Defence notes the findings of the ANAO, and agrees to both recommendations.

Defence concurs with the ANAO’s conclusion that the fundamentals of the governance and organisational framework for the management of sustainment are clear, and fit for purpose.

Defence notes that the audit was conducted at a strategic level, and acknowledges the opportunities for improvement identified by the ANAO. Defence continues to strive towards efficiencies in the delivery of sustainment outcomes for Defence capability and to report on outcomes, noting the need to balance transparency and accountability to the Australian public and Parliament, with the national security interests of the Commonwealth.

Defence’s implementation of the recommendations of the First Principles Review has also introduced a single end-to-end capability development function, the Capability Life Cycle, which will reduce previous delineations between the management of acquisition and sustainment activity.

1. Background

1.1 Defence materiel sustainment is about the maintenance and support of Defence’s fleets of specialist military equipment. Defence defines sustainment as involving the provision of in-service support for specialist military equipment, including platforms, fleets and systems operated by Defence. Typically, sustainment entails repair and maintenance, engineering, supply support and disposal of equipment and supporting inventory.4 Effective sustainment of naval, military and air assets is essential to the preparedness of the ADF and to enable Defence to conduct operations in accordance with the Government’s requirements.5

1.2 Defence has commented that sustainment management is not a technical discipline: ‘it is an over-arching business-oriented management function focused on meeting the outcomes required of Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group customers’.6

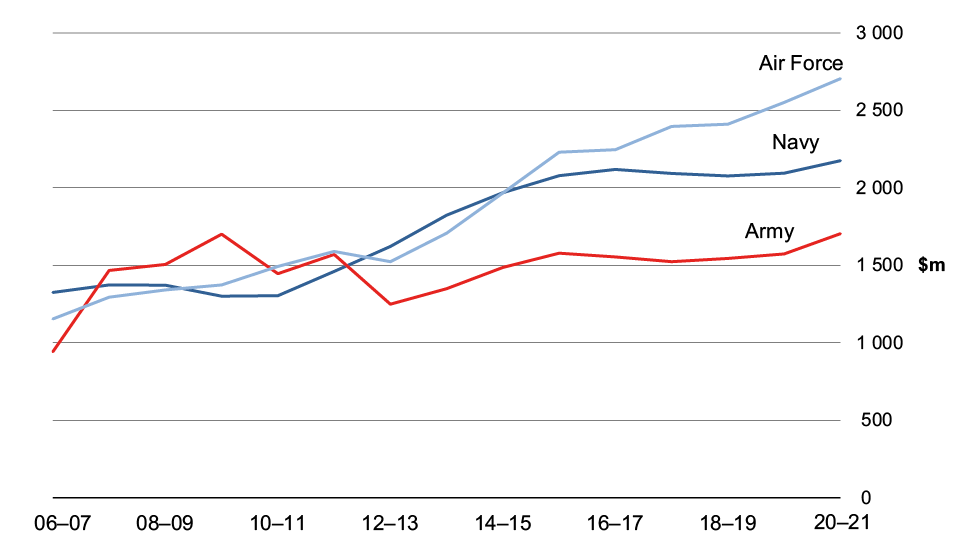

1.3 In recent years, Defence has spent, each year, similar amounts on sustainment and the acquisition of new equipment (Figure 1.1, below). In 2015–16, Defence spent about $6.3 billion—21 per cent of its total departmental expenditure—on sustainment of specialist military equipment.

Figure 1.1: Defence acquisition and sustainment expenditure

Note: For 2005–06 to 2014–15, expenditure was made through the Defence Materiel Organisation. Figures for 2015–16 are based on Defence advice with one-third of Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group staff costs allocated to acquisition and two-thirds to sustainment.

Source: Defence Annual Reports 2005–06 to 2014–15, and Defence advice.

Parliamentary interest

1.4 Parliamentary committees over several years have stated an interest in Defence’s reporting of its sustainment performance and, in particular, obtaining greater insight into that performance.7 In May 2014, the JCPAA recommended that the DMO prepare a suitable methodology for reporting sustainment activity and expenditure, within six months.8 The Government disagreed on the basis that current arrangements balanced Parliamentary scrutiny of sustainment expenditure with the protection of classified information on the military capability, readiness and availability associated with that sustainment.9 In September 2014, the Committee sought a sustainment options paper from the ANAO, which was made public by the Committee. Defence subsequently provided the Committee with an in camera briefing (November 2015), consistent with an option in the paper put forward by the ANAO. The Committee expressed the view, in May 2015, that:

Sustainment expenditure is currently at approximately $5 billion per annum and predicted to increase significantly over time. The Committee considers sustainment expenditure to be an area requiring further parliamentary scrutiny on the adequacy and performance of Defence involving billions of dollars in the future.10

1.5 The Committee noted, however, that the final structure for sustainment reporting was as yet undecided. During the course of this audit (9 January 2017) the Committee announced that it had commenced an inquiry into Defence Sustainment Expenditure. Part of the context for this audit is to inform the Parliament as to whether Defence has developed its management reporting sufficiently to facilitate a program of ANAO assurance reviews of selected sustainment activities.

1.6 The ANAO’s observations on this aspect of the audit are reflected in the Summary and Recommendations section of this report (paragraph 32 forward).

Audit approach

1.7 The objective of the audit was to assess whether Defence has a fit-for-purpose framework for the management of materiel sustainment. To form a conclusion against the audit objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Defence has established an appropriate governance and operational framework for the management of materiel sustainment;

- Defence has established and implemented a high quality performance framework to support the management and external scrutiny of materiel sustainment; and

- Defence has achieved key outcomes expected from the Smart Sustainment reforms and has progressed its implementation of the reforms to sustainment flowing from the First Principles Review.

1.8 The scope of this performance audit is the management of sustainment of specialist military equipment. It addresses sustainment management at a high level and is not focused on the sustainment of individual platforms or the technical aspects of their maintenance. Defence’s broader sustainment program also includes the maintenance and support of corporate information technology and estate and infrastructure assets. These activities are outside the scope of the audit.

1.9 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $422 000.

1.10 The team members for this audit were Dr David Rowlands, Kim Murray and David Brunoro.

2. Defence’s governance and operational framework for the management of materiel sustainment

Areas examined

This chapter examines Defence’s governance and operational arrangements for managing the sustainment of specialist military equipment.

Conclusion

Defence has clear and long-standing governance and organisational arrangements for managing the sustainment of specialist military equipment.

Research and reviews conducted for Defence have revealed a range of specific operational problems that are detracting from the efficient and effective sustainment of Defence capability, including the functioning of Systems Program Offices. Defence has initiated a reform project as part of its First Principles Review implementation.

Does Defence have a clear governance and operational framework for the management of materiel sustainment?

Defence has clear and long-standing arrangements for managing the sustainment of specialist military equipment. Key elements of the governance and organisational framework include: a specialist organisational unit—currently the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group—staffed by a mix of civilian and military personnel; contract-like arrangements for sustainment between that unit and the Chiefs of Navy, Army and Air Force (Defence’s Capability Managers); and day-to-day responsibility for most sustainment activities falling to Systems Program Offices, which carry out that work using a mix of in-sourced and out-sourced service provision. Military units also undertake some operational-level sustainment activities.

Nevertheless, an internal review conducted by Defence and research conducted for Defence following the 2015 First Principles Review have identified a range of operational problems that detract from the efficient and effective sustainment of Defence capability, including: adherence to procurement principles; staff capabilities; duplication of effort and transparency of internal costs. A project to reform and consolidate Systems Program Offices is currently underway, with 24 out of 64 Systems Program Offices (37.5 per cent) reviewed as at February 2017.

2.1 The ANAO examined Defence’s governance and operational arrangements for managing the sustainment of specialist military equipment, with a particular focus on the clarity of:

- roles and responsibilities; and

- processes for documenting capability managers’ requirements around sustainment.

Governance and operational arrangements

2.2 Defence has clear and long-standing arrangements for the management of materiel sustainment for specialist military equipment. Key elements are:

- since 2000, a specialist acquisition and sustainment unit—previously the Defence Materiel Organisation (DMO) and most recently the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group—staffed by a mix of civilian and military personnel;

- maintenance by the specialist unit of physically dispersed sub-units—known as ‘Systems Program Offices’—with day-to-day responsibility for Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group sustainment activities11;

- since 2005, contract-like arrangements known as ‘Materiel Sustainment Agreements’ between the specialist unit and the Australian Defence Force’s capability managers—primarily the Chiefs of Navy, Army and Air Force;

- a mix of in-sourced and out-sourced service provision for sustainment activity; and

- reliance on a mix of public and private equipment and facilities for sustainment activity.

2.3 While a number of reviews have focused on the optimal distance of the specialist entity from the Department of Defence12—with changes over time in its degree of separation—and have made recommendations on the unit’s operations and practices, the fundamentals of the sustainment management framework have been stable for over a decade.

Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group

2.4 The sustainment of specialist military equipment was formerly a core responsibility of the DMO. Following government acceptance of a recommendation of a review of Defence—the First Principles Review, which reported in April 2015—DMO was delisted from 1 July 2015.13 DMO’s sustainment role then passed immediately to Defence’s Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group.14 As at November 2016, Defence employed about 5500 people in that Group.15

2.5 Defence describes the accountabilities of the Group as follows:

The Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG) purchases and maintains military equipment and supplies in the quantities and to the service levels that are required by Defence and approved by Government.16

We are accountable to:

- The Australian Government through the Defence Ministers (our owner).

- The Secretary of Defence and Chief of the Defence Force.17

- The women and men of the ADF through the capability managers (our customers).

- Defence industry (our partners).

Systems Program Offices

2.6 As at February 2017, Defence had some 64 Systems Program Offices, which manage the acquisition, sustainment and disposal of specialist military equipment. They do this through a combination of internal work and commercial contracts. In January 2017 Defence’s Systems Program Offices managed the sustainment of 112 fleets of equipment and services. Systems Program Offices are located in different parts of the country but are organisationally all part of the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group within Defence. They may also be involved in acquisition projects but the greater bulk of their work involves sustainment.

2.7 In most cases, a major platform—such as an aircraft type or class of ship—is managed by a single Systems Program Office.18 Systems Program Offices maintain a relationship with industry bodies, particularly those providing maintenance services, spares, engineering and other support, and with the representative of the relevant capability manager.19 Each Systems Program Office has contracts with industry suppliers of services, parts and consumables.

|

Box 1: The origin of Systems Program Offices |

|

Reviews of Defence over the last two decades have identified many opportunities for improvement in Defence sustainment practice. Defence established Support Command Australia in August 1997 to coordinate materiel support to Navy, Army and Air Force, ‘and to help Defence “do more with less”’. In 2000, when the expected benefits were not being realised, Defence reviewed Support Command Australia and the Defence Acquisition Organisation, finding that serious problems persisted in capital acquisition and whole-of-life support. To address these problems, Support Command Australia, the Defence Acquisition Organisation and part of National Support were merged to form the DMO. The DMO was to be accountable for whole-of-life materiel management, with Systems Program Offices comprising multi-functional teams to undertake the work. The Defence White Paper, Defence 2000—Our Future Defence Force, stated that ‘the DMO will adopt commercial best practice as its norm and assess its performance against industry benchmarks’. The subsequent Defence Procurement Review (‘Kinnaird Review’) in 2003 also stressed the need for high-quality, highly skilled sustainment managers in delivering modern military capability in a ‘business-like manner’. |

2.8 As a consequence of the 2015 First Principles Review and the decision to consolidate and reform Systems Program Offices, Defence has adopted a new definition of ‘Systems Program Office’. A number of acquisition projects had been managed in project offices which are now counted as Systems Program Offices.20 Systems Program Offices do not endure indefinitely: for example, after the withdrawal from service of an asset and its disposal the relevant Systems Program Office may be dissolved or amalgamated with another. Similarly, a new Systems Program Office may be created for a major acquisition project. A list of Systems Program Offices (including staff numbers, assets under sustainment and contracts) is at Appendix 1.

|

Box 2: Sustainment work in Defence’s Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group |

|

Sustainment can be considered as falling into three categories: sustainment of platforms, products and commodities, as well as the provision of services such as test and measurement. Platforms represent a large and complex capability such as frigates, tanks or aircraft. There are over 40 platform fleets being supported and they represent around 60 per cent of total sustainment expenditure in any given year. These are usually long life items, with little fleet replacement across years to decades and have budgets dominated by maintenance. Most of the sustainment budget is for maintenance of major platforms which, in turn, depends on age and use. Thus, for example, slippage in new acquisition projects can increase sustainment costs for ageing platforms. Products are those that deliver a capability based on smaller but more numerous systems often involving regular replacement of all, or components of, the capability. Examples include B Vehicles (Land Rovers, G-Wagons), Direct Fire Support Weapons, Aeronautical Life Support Equipment and Command and Support Systems—Maritime. Maintenance is still a large cost component for sustainment of these systems but regular replacement is more significant in comparison with platforms. Support of products represents about 20–25 per cent of sustainment expenditure. For commodities, the maintenance component of the budget is comparatively small with replacement or replenishment being the dominant activity. Fuel and lubricants, combat clothing and explosive ordnance fall into this category, which makes up about 20 per cent of sustainment expenditure. |

Source: Abstracted from Defence, ‘Reform Issues’, April 2011.

Internal Agreements

2.9 Agreements, internal to Defence, between the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group and each capability manager, set out the level of performance and support required by the capability manager.21 These are ‘Materiel Sustainment Agreements’ (MSAs). MSAs include an agreed ‘price’ for the sustainment work and performance indicators by which Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group internal service delivery is measured and reported.22

2.10 Defence intends to replace MSAs (and the associated Materiel Acquisition Agreements) progressively with Product Delivery Agreements. The Product Delivery Agreement will cover both acquisition and sustainment of a capability system over its life, through to disposal.

2.11 A simplified representation of the essential relationship among elements responsible for the sustainment of specialist military equipment is in Figure 2.1 below.

Figure 2.1: Simplified representation of organisational arrangements supporting Defence sustainment of specialist military equipment

Note: Military units also undertake some operational-level sustainment activities.

Source: ANAO

2.12 Navy, Army and Air Force policy requires six-monthly reviews of MSAs. These are known within Defence as ‘Fleet Screenings’.23 While ‘Fleet Screening’ procedures vary among the Services, the intent is broadly similar: that is, to review the funding allocated to sustainment through the MSAs, and make decisions about changes to funding levels, equipment operation, or performance indicators.24 For example, additional funding may be required for equipment that has recently returned from operations. Fleet Screenings comprise a meeting or series of meetings between the Services and Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group.

Relationship between sustainment and acquisition

2.13 Generally, the lifecycle of Defence’s military assets falls into two periods: acquisition and sustainment. There has long been a strong internal perception in Defence that sustainment attracts less management attention than acquisition. An internal survey a decade ago found that Systems Program Offices attributed the problem to Defence management in Canberra:

sustainment still does not get sufficient level of attention and needs to be recognised as the major component of the life cycle. [Systems Program Offices] claim that policies and new tools are developed which do not sit well with sustainment and, because Canberra is acquisition-focused, sustainment advice is not taken.25

2.14 Five years later, the Rizzo Review into naval sustainment drew a similar conclusion:

The need for the sustainment of assets is understood in Defence and DMO, but it is not given the same rigorous attention as asset acquisition. Sustainment costs can exceed those of the original procurement and the challenges can be more complex.26

2.15 Coles took a similar view a few months later, in the Collins Class Sustainment Review, arguing that Defence should give sustainment much higher attention and priority during the initial phases of the asset’s lifecycle (‘Needs’, ‘Requirements’, and ‘Acquisition’ phases). Failure to pay sufficient attention to sustainment early on would increase the cost of ownership to Defence. That review found ‘sustainment is still being treated as a “poor relation” compared to the generally higher-profile acquisition work’.27 The Sustainment Complexity Review (2010), which found ’50 plus’ sustainment business models in DMO’s Systems Program Offices, explained this diversity by reference to the greater attention Defence had given acquisition. Defence had developed, by the time of that review, a consistent approach to acquisition. But ‘no such global improvement approach’ had been implemented across sustainment. The Review found, in terms similar to those of Coles: ‘In fact, the general comment is that “sustainment is the poor cousin to acquisition.”’28 In June 2017 Defence advised the ANAO that it was attempting to address this perception through the current round of reforms, such as the new Capability Life Cycle and the December 2016 release of Support Procurement Strategies.

Review of Systems Program Offices

2.16 Two recent reviews of the operations of Systems Program Offices have identified major challenges for the future management of sustainment. The first is a Defence internal review conducted in late 2015; the second comprises work done following the First Principles Review as part of the Systems Program Office reform and consolidation project.

Review of contracted services arrangements in Systems Program Offices

2.17 In late 2015, Defence’s Audit and Fraud Control Division reviewed the contracted service arrangements within three Systems Program Offices in response to a request by Defence’s Chief Finance Officer Group. That review found shortcomings in the application of procurement principles, which exposed Defence to risks. Specifically, the review identified instances where:

- Defence had not established a strong case for value for money for the continual renewals of supplier contracts. This practice: has created the risk of dependency on particular suppliers; raises concerns about probity as contractors and APS staff involved in the procurement may not be dealing with each other at ‘arms-length’; and means that Defence may not be getting value for money.

- Defence suppliers have access to potentially commercially sensitive Defence financial information which could provide an unfair advantage to some service providers.

- Defence has entered into sole source contracts with suppliers outside of the Defence system established to manage such arrangements. As a result: service providers may have been contracted to provide services for which Defence has previously determined they were not suitable to deliver, and/or charge higher rates than previously negotiated with Defence; and there is a risk that the documentation required to support the procurement decision may not be adequate.

- Defence procurement guidance did not reflect some of the requirements of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules in place at the time of the review.

2.18 Defence makes extensive use of external service providers and contractors to deliver acquisition and sustainment services. Further, Defence’s Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group, is implementing reforms that will potentially increase reliance on industry to deliver these services. Defence therefore requires a robust framework to manage the risks associated with the widespread use of contracted services. Defence informed the ANAO that it had updated its procurement guidance in April 2017 and intends to address the other concerns raised in the 2015 review over the next 18 months.

Reform and consolidation of Systems Program Offices

2.19 Following the First Principles Review, Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group is undertaking a project to reform and consolidate Systems Program Offices. In its submission to the JCPAA inquiry into sustainment expenditure about this project (February 2017), Defence advised that:

[Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group] Systems Project Offices Reform project is undertaking a review of all SPOs across [Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group]. The outcome from this review is alignment of the SPO activity to Planning, Governance and Assurance roles, and enabling industry to undertake the management and delivery of sustainment activity, in particular the transactional functions required to maintain capability.

2.20 Defence records indicate that, as at February 2017, the project had reviewed 24 Systems Program Offices across three ‘domains’ (Maritime, Aerospace, and Joint), comprising 37.5 per cent of the Group’s business delivery units. Systemic issues identified by Defence from the reviews of Systems Program Offices to date are set out in Box 3. They include:

- the experience, skills and competencies of Systems Program Office staff;

- duplication of effort; and

- overhead costs.

2.21 The review is examined in more detail in Chapter 5 of this audit report, while the transparency of internal costs is examined in Chapter 3.

|

Box 3: Systemic issues identified by Defence in the reform of Systems Program Officesa |

|

Capability Manager Engagement The Support and Operating Intent of the capability are not being adequately articulated by Capability Managers, which results in:

Activities assigned to the Services that affect asset management and asset condition are not being completed, and limited feedback is being provided to the Capability Manager Representative regarding the impact of non-completion on cost and availability. Supplier Management SPO staff have limited experience, skills, and competencies needed to effectively establish, govern, and assure industry delivery of capability.

The bulk of SPO staff consist of engineering and logistics experts who are trained to solve technical and practical problems. They tend to manage outcomes by testing quality and auditing activity rather than assuring capability outcomes governing supplier processes; this results in ‘man marking’b [industry], duplication of effort, rework, and delays. The number of SPO staff supporting activities such as planning, contract management, and assurance may not be sufficient and this is a risk to achieving FPR goals (including SPO reform) and ongoing delivery of [Integrated Investment Program] activities. Hidden Overhead SPO overhead has increased through a number of avenues:

Transactional Work SPOs continue to manage and perform work that industry may be able to do more effectively or efficiently, whilst insufficient resources are being applied to governing and assuring. The review team assesses that in some cases, 25–30 per cent of current SPO activity is involved in auditing and ‘man marking’ industry, making basic modifications, and the management of these activities. |

Note a: Defence, CASG Executive Advisory Committee paper position paper reflecting the views of the SPO Reform Project, 13 February 2017.

Note b: ‘Man-marking’ is where Defence staff in the Systems Program Office supervise the performance of one or a small number of contractor personnel.

3. Defence’s performance framework for materiel sustainment

Areas examined

This chapter examines Defence’s performance framework to support the management and external scrutiny of materiel sustainment for specialist military equipment.

Conclusion

The development of an effective sustainment monitoring system remains a work-in-progress, and the effectiveness of Defence’s internal reporting system for sustainment could be improved in several areas. Opportunities also remain to increase the completeness and transparency of publicly reported information regarding materiel sustainment.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has recommended that Defence institute a risk-based quality assurance process for information included in the Quarterly Performance Report. Defence’s sustainment ‘gate reviews’ could usefully contribute to this assurance process.

Defence should also clarify whether the Quarterly Performance Report system reports on sustainment activities across Defence or is limited to the activities of the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group.

3.1 To assess whether Defence has in place an effective performance framework to support the management and external scrutiny of materiel sustainment, the ANAO examined:

- monitoring systems for sustainment;

- internal reporting practices for sustainment;

- reviews of sustainment performance;

- whether Defence has established measures of efficiency and productivity for sustainment activity;

- whether Defence assesses whole-of-life costs and the total cost of ownership of its assets; and

- public reporting on sustainment.

Does Defence have effective monitoring systems for sustainment?

With the introduction of its Sustainment Performance Management System (SPMS), Defence continues to develop a basis for an effective monitoring system for sustainment. Once fully implemented this system should be capable of systematically reporting against a suite of performance indicators settled in agreement with Capability Managers.

There remains potential to improve some core key performance indicators used within the system—for example to more usefully determine the total cost of the capability to Defence. The SPMS system was not fully implemented during the ANAO’s audit fieldwork but is expected to be fully operational by the end of June 2017. In the longer term the system is to be expanded to cover acquisition.

The Monthly Reporting System (MRS) and the Sustainment Performance Management System (SPMS)

3.2 The reporting system relied upon by Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group and, before it, the DMO, to track major acquisition projects since mid-2004 has been its web-based Monthly Reporting System (MRS). At the time DMO developed MRS it was noted internally that ‘DMO currently spends around 3 billion dollars per year on sustainment activities and at this stage has no system that can adequately report on the effectiveness or efficiency of these activities’.29 Work began in September 2005 to introduce sustainment reporting capacity into MRS.

3.3 Several major reports have criticised sustainment reporting over the last decade, including Mortimer (2008) and Rizzo (2011).30 Rizzo was highly critical of existing performance indicators:

Each current [MSA] Product Schedule has inadequate Key Performance Indicators … They only include a small subset of the ‘contractual’ measures that should be placed on each party and there are no consequences associated with non‐compliance. At worst, non‐delivery will result in a red traffic light status in DMO Sustainment Overview Reports which it seems that few stakeholders read.31

3.4 This led to the commencement of work on a new IT system, the Sustainment Performance Management System (SPMS), in mid-2011 to replace the sustainment module in MRS.32 Defence agreed in August 2012 to the ‘continuing refinement and implementation of a shared Sustainment Performance Management Framework and reporting system for use in the sustainment of all products jointly managed by Defence and DMO’.33 An objective of developing SPMS is that the system should provide ‘the central source of truth for sustainment management data and reporting for sustainment management personnel at all levels of both Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group and Capability Manager organisations’.34 This was contrasted with the MRS, which reportedly required substantial work-arounds requiring double and triple handling. MRS and, to an increasing extent, SPMS, are now used to populate a Quarterly Performance Report on both acquisition and sustainment (see paragraph 3.11 forward).

How SPMS works

3.5 In common with MRS, SPMS is a web-based system designed to provide performance reports for Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group and Capability Managers. Data is entered monthly by subject matter experts, usually based in the relevant Systems Program Office. The Systems Program Office Director reviews the data and comments for each measure and provides comments for a set of ‘key performance indicators’ and an additional set of ‘key health indicators’.35 Further comments can be added up the hierarchy to the relevant Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group division head. By way of example, Appendix 2 of this audit report lists Navy’s MSA Performance Framework core Key Performance Indicators and Key Health Indicators.36 Defence advised the ANAO that Air Force has also developed a corresponding set of indicators and Army is progressing similar work.

SPMS implementation

3.6 SPMS was introduced, first, for Navy (May–July 2015) following work to develop its sustainment performance framework with a standard suite of performance indicators.37 The system was being implemented in Air Force and Army from late 2015 through 2016. Implementation is incremental and subject to feedback and review. Defence expects that all sustainment products will be reporting in SPMS by the end of June 2017.

3.7 A joint review of Navy’s performance framework, completed in March 2016 by Navy and Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group, concluded that there was ‘universal acceptance that the framework provides a sound basis for the assessment of sustainment outcomes’.38 However, the review decided to remove one of Navy’s core key performance indicators (cost per materiel-ready day achieved) on the basis that the measure required the Systems Program Office to enter four separate data elements and ‘stakeholder compliance’ was reportedly low. The indicator was replaced with a measure ‘CASG-related Product Cost per materiel-ready day’, whose value could be generated automatically and would not require comment by the Systems Program Office.39 This would be reported in SPMS but not be represented as a key performance indicator40 because it did not include the cost of all the fundamental-inputs-to-capability and did not measure the cost per materiel-ready day. Defence informed the ANAO that both measures are based on direct product costs incurred by the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group and do not include sustainment costs incurred by other parts of Defence.

3.8 Neither indicator is useful in determining the total cost of the capability to Defence. Knowledge of the total cost could contribute to a better understanding of the whole-of-life costs of Navy assets and, over time, could provide useful insight into whether cost-effectiveness is improving or deteriorating.41

Further development of SPMS

3.9 In September 2016, Defence decided to expand SPMS to cover acquisition. When implemented, the system will be renamed the ‘Program Performance Management System’.42 In the long term, Defence intends to build an ‘enterprise solution’ to encompass both sustainment and acquisition management and reporting using SAP software.

Does Defence have effective internal reporting for sustainment?

The effectiveness of Defence’s internal reporting system for sustainment could be improved in several areas. The Quarterly Performance Report is the primary way by which Defence provides information to government and senior Defence personnel about the status of major acquisition and sustainment activities. However, based on the ANAO’s review of a Quarterly Performance Report produced during the audit, its contents are neither complete nor reliable, it takes two months to produce and its contents are sometimes difficult to understand. The ANAO’s analysis found that the report may not include additional information available to Defence that is critical to the reader’s ability to understand the status of significant military platforms. It provides only a partial account of materiel sustainment within Defence and is potentially at odds with the ‘One Defence’ model promoted by the First Principles Review.

The ANAO has recommended that Defence institute a risk-based quality assurance process for information included in the Quarterly Performance Report.

3.10 Reviews of Defence over the years have highlighted the importance of management reporting on its activities. The Mortimer Review (2008, p. 48) noted that the efficiency and effectiveness of DMO sustainment performance will not improve unless it is measured.

The Quarterly Performance Report

3.11 The Quarterly Performance Report is the primary way by which Defence provides information to government and senior Defence personnel about the status of major acquisition and sustainment activities.43 The report was developed in 2015 in consultation with the office of the Minister for Defence. Staff in the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group compile the report manually, incorporating information contained in MRS and, increasingly, SPMS. The report includes performance summaries for the Top 30 major acquisition projects, all major acquisition projects reported in the Major Projects Report and the Top 30 sustainment products. The report also includes an overview of projects of concern and underperforming acquisition projects and sustainment products.

3.12 In a recent submission to the JCPAA, Defence stated that ‘The Defence Ministers are provided with a Quarterly Performance Report, which includes Projects of Concern, Projects and Products of Interest and Performance Summaries for the Top 30 Sustainment Products’.44 The stated intent of the Quarterly Performance Report is to provide ministers and senior Defence personnel with:

a clear and timely understanding of emerging risks and issues in the delivery of capability to our Australian Defence Force end-users. These risks and issues are highlighted so that stakeholders can respond in a coordinated manner to guide the conduct of remediation actions.

3.13 This broad focus is consistent with Defence advice to the ANAO that some sustainment services for some equipment items are also undertaken by Capability Managers and other enabling Groups, including Joint Logistics Command.45 The primary data source for the report is SPMS—the ‘central source of truth for sustainment management data and reporting for sustainment management personnel at all levels of both Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group and Capability Manager organisations’.46 The approach, as advised to the JCPAA, also reflects the First Principles Review recommendation that an end-to-end approach should be taken for accountability for capability—the ‘One Defence’ model.47

Figure 3.1: Preparation of the Quarterly Performance Report

Source: ANAO

3.14 However, Defence advised the ANAO in June 2017 that the Quarterly Performance Report’s ‘primary focus is on products and projects delivered by the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group, and does not encompass the complete sustainment enterprise. This narrower focus risks telling only a partial account of sustainment within Defence and is potentially at odds with the ‘One Defence’ model promoted by the First Principles Review

Assessment of the report

3.15 Under current arrangements for its production, the Quarterly Performance Report is neither timely—it is more than 50 days old by the time it gets to ministers—nor clear—it is dense with acronyms and jargon. Some terms are used in an unusual way, for example, expenditure of more funds than had been budgeted is referred to as an ‘overachievement’.

3.16 One potentially useful feature is a list of underperforming sustainment products.48 This is based on information provided through MRS, SPMS and gate reviews. Eight underperforming products were listed in the second quarter of 2016. Ten such products are listed in the report for the subsequent quarter (July – September 2016). In that later report the list was labelled ‘sustainment products of interest’ rather than ‘underperforming’, though the items are still listed ‘in order of concern’.

Case study—performance reporting on Army’s Armed Reconnaissance Helicopter

3.17 The ANAO observed marked differences in the information provided about Army’s Armed Reconnaissance (Tiger) helicopter between:

- a Quarterly Performance Report to the Defence Minister produced during the audit (April – June 2016) and, in contrast,

- a recent ANAO performance audit49, the 2015–16 Major Projects Report50, a sustainment gate review51 and the Houston review of Army Aviation.52

3.18 A comparison shows that the Quarterly Performance Report does not include information available to Defence that is critical to the reader’s ability to understand the gap between the expectation of capability and reality for the Tiger helicopter program (See Appendix 3).

3.19 In this case, the Quarterly Performance Report’s usefulness is reduced by the following:

- The use of the ‘traffic light’ indicators ‘Green’ (acceptable performance) or ‘Amber’ (early signs of underperformance). Neither of these is a reasonable assessment of the aircraft’s capacity to meet the required level of capability expected by government.

- The report’s traffic lights, in particular, focus attention on the measures contained in contractual and intra-Defence agreements (for example, aircraft ‘availability’) and not the measures that matter to Army, the end-user (aircraft actually able to be flown).53

- The year-end spend performance indicator is blank.

3.20 The contrasting information identified in this case indicates that the Quarterly Performance Report would benefit from the application of a quality assurance process to ensure that government and senior Defence personnel are presented with a frank and balanced assessment of performance (see paragraph 3.27 below).

Does Defence conduct effective reviews of sustainment performance?

Defence conducts reviews of sustainment performance through sustainment gate reviews that help Defence to obtain insight into a project or product’s progress and status. The effectiveness of these reviews could be increased if the lessons obtained from gate reviews were routinely incorporated into management reporting on sustainment and if gate reviews were extended to contribute to the proposed quality assurance mechanism for Quarterly Performance Reports.

3.21 Defence has implemented a strategy in recent years that should help to draw problems in individual sustainment products to senior management attention. This has occurred with the extension of DMO’s earlier program of gate reviews to cover sustainment as well as acquisition.54

3.22 In 2009 Defence commenced gate reviews for capital acquisition projects as an internal assurance process.55 They have provided insight into a project’s progress and an opportunity for project staff to discuss difficult issues with senior management and seek guidance. Defence later recognised that gate reviews also have potential value for sustainment, especially where it allows management to become aware of maintenance problems that might otherwise remain hidden. The Rizzo Review into naval sustainment raised this problem in the following terms:

To avoid being seen to fail personally, there is a danger (especially in the can do, make do environment) that staff will choose to not raise bad news. This can result in bad news remaining at lower levels in the organisation, increasing enterprise risk and only becoming apparent when recovery is expensive, difficult or even impossible.56

3.23 Defence commenced sustainment gate reviews in December 2015. Gate reviews are conducted to ‘provide high quality and reliable advice to Defence and Government regarding the health and outlook of both acquisition projects and sustainment products’. Defence requires that the first sustainment gate review be held within 12 months of the review held before final operational capability is reached.57 Thereafter, further such reviews are to be undertaken periodically (every one, two or three years) with the exact timing determined on a risk basis. Defence has stated that gate reviews ‘review overall performance of the sustainment system and its fitness for purpose rather than just its outcomes for the past month.’

3.24 Gate reviews can draw management attention to sustainment risks in individual fleets. For example, sustainment cost has been identified as a ‘key risk’ for the MRH90 helicopter:

- An ANAO performance audit in 2013–14 found that, at the time of approval (June 2004), Defence had estimated the sustainment cost for 40 aircraft at $85.2 million a year.58

- By 2009–10 when only 15 aircraft had been delivered, the cost of sustainment for those aircraft had already exceeded $85 million per annum.

- During 2012 DMO endeavoured to capture and model the expected cost of ownership for the 47 MRH90 aircraft over the planned life of the aircraft. That modelling indicated cost of ownership of between $240 million and $360 million per year (October 2012 prices), or $5.1 million to $7.7 million per aircraft per year.

- In May 2016, a sustainment gate review identified the cost of sustainment as a key risk for this program. Defence confirmed in March 2017 that this risk remains.

3.25 Information from sustainment gate reviews is not routinely incorporated into management reporting on sustainment. The ANAO suggests that Defence could devise a means of doing this, thereby capturing additional useful information on sustainment performance and current risks. For example, Quarterly Performance Reports could include a section providing an update on how the issues identified in the sustainment gate reviews are being addressed over time.

3.26 Moreover, there is an opportunity for Defence to extend the use of its Sustainment Gate Review program to have those reviews consider the quality of the information provided in the most recent Quarterly Performance Report for the asset under review, to help quality assure the accuracy, clarity and completeness of that information. As discussed, a quality assurance process for the Quarterly Performance Report would provide a firmer basis for internal and external scrutiny of sustainment reporting.

Recommendation no.1

3.27 The ANAO recommends that Defence institutes a risk-based quality assurance process to ensure the accuracy, completeness and relevance of the information included in the Defence Quarterly Performance Report.

Entity response: Agreed

3.28 Defence will institute a Quality Assurance process covering the Defence Quarterly Performance Report.

Has Defence established measures of efficiency and productivity for sustainment activity?

Defence has not implemented measures of efficiency and productivity for all sustainment products. Reviews have consistently emphasised the need for Defence to improve the efficiency of its operations, including in sustainment. Most recently, the First Principles Review recommended immediate implementation of measures of productivity, a related concept. The ANAO found that, 18 months after implementation commenced, there had been limited progress.

3.29 The efficiency of sustainment has been raised repeatedly over the years. In 2003, a few years after the formation of the DMO, a ‘zero-based’ review found that there was a ‘significant opportunity to reduce resourcing levels by re-engineering processes and improving systems’—in other words, improve efficiency.59 Specifically, there was potential to ‘optimise resource utilisation through judicious outsourcing to original equipment manufacturers in appropriate circumstances’. Later (April 2004), senior DMO managers stated that there was scope to achieve a better risk balance in sustainment program management, where well-defined tasks had, in the past, been transferred to industry successfully with net savings, thereby improving efficiency.

3.30 More recently, after the release of the 2015 First Principles Review, one of the Review panel members characterised inefficiency as the most prominent problem across Defence:

The big problem that the Review team saw was one of efficiency and not of effectiveness. By any reasonable standard the military output—the effectiveness of the ADF—is world class, but does the Department arrive at that effectiveness in the most efficient way possible? Can the Department assure the Government of the day and the Australian taxpayer that the resources—the people, processes and tools—used to create that output are being utilised in the most efficient way? The Review team thought the answer to that was ‘No’.60

3.31 To develop sound measures of efficiency, Defence also needs to understand the cost of ownership of its assets (see paragraph 3.34 forward) and to take account of staff costs in assessing the total cost of its activities (see paragraph 3.44 forward).

3.32 The First Principles Review found no direct measures of productivity in the existing management information systems, though some cost and schedule information is included in MRS and SPMS. The Review proposed the immediate implementation of productivity measures at a project level:

It is also incumbent upon the organisation to have a process in place that effectively measures its cost, schedule and productivity at a project level. This should be implemented immediately and individual leaders from the first line to the Deputy Secretary Capability Acquisition and Sustainment must be accountable for cost and schedule targets.61

3.33 On the question of the above recommendation about measuring productivity, Defence referred the ANAO to the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group Business Framework and, within it, the proposed process for the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group Business Review Cycle. The Business Review Cycle provides for monthly Project/Product Performance Reviews (PPRs) and, at increasing levels of aggregation, Branch monthly reviews and Domain monthly reviews. Deployment of the PPR was, at that point (September 2016), ‘on pause’ pending further review of the prototype arrangements. The envisaged end state is the deployment of a Program Performance Management System (PPMS), see paragraph 3.9 of this audit report), covering both acquisition and sustainment, commencing 30 June 2017.62

Does Defence effectively assess whole-of-life costs and the total cost of ownership of Defence assets?

Defence has recently improved its whole-of-life costing of proposals to acquire major capital equipment but remains unable to measure or report reliably the total cost of ownership. It is now planning to implement a new model, which seeks to capture the full cost of ownership throughout the life of an asset, with implementation planned for completion in July 2018. The First Principles Review has pointed out that Defence has treated Systems Program Office staff costs at the project level as a free good, reducing the transparency of the cost of sustainment work and providing inaccurate price signals and a distorted incentive structure to Capability Managers.

3.34 Achieving value for money is the core rule of the Commonwealth Procurement Rules. When conducting procurement, an official must consider the relevant financial and non-financial costs and benefits including, among other things, whole-of-life-costs.63 Sustainment expenditure is a major contributor to whole-of-life costs—in some cases, the largest contributor.

3.35 Defence major capability decisions have substantial long‐term financial consequences for Defence and the Commonwealth budget. Nevertheless, developing whole‐of‐life cost estimates for major capital projects has been a challenge for Defence for decades. A Defence instruction on lifecycle costing has been in place since at least November 1992.64 In addition, a ‘Through Life Support Manual Volume 6—Life Cycle Costing Analysis’ has been available since 2001 (and remains current).65 The issue of instructions and availability of guidance has not provided assurance of adequate costing action.

3.36 Numerous reviews and audits have urged greater focus on whole-of-life costs and better knowledge of the total costs of ownership of military assets, including sustainment, but have found that Defence has struggled to establish the skills, systems and data for this activity66:

- Defence was urged to use lifecycle costing throughout the acquisition lifecycle by an ANAO performance audit in early 1998. The audit had found, among other things, that it was not generally used in the ‘in-service’ (sustainment) stage.67 The audit included, as an appendix, a brief better practice guide to lifecycle costing.

- Defence agreed to the recommendation that total cost information be provided to relevant Defence committees, with qualification.68 When Defence reported in 1998 on the implementation of the then recent Defence Efficiency Review, it stated that ‘A project has been initiated by the Joint Logistic Systems Agency to establish a common process to address through-life support arrangements, including … lifecycle costing … ’.69

- In 2008, the Mortimer Review recommended that decisions to purchase new equipment or maintain existing systems should be based on the through-life cost of each option.70

- By July 2011, the Rizzo Review stated that ‘The Team recognises that Defence has a policy instruction on life‐cycle costing … However, it is considerably out‐of‐date and compliance is inadequate’.71

Presenting whole-of-life cost estimates to government for approval

3.37 In recent years, Defence has generally estimated whole-of-life costs when seeking government agreement to a proposed acquisition. An ANAO performance audit in 2013 found that, in most cases, submissions to government included whole-of-life cost estimates. However, this was not presented as prominently as acquisition costs nor was its significance made clear to decision-makers.72

3.38 In the course of this audit, the ANAO examined nine Defence major capital equipment submissions approved by government between July 2015 and April 2016 to review the presentation of whole-of-life costs.73 In all but one submission examined, whole-of-life cost estimates are more prominent than in the submissions examined for the 2013 ANAO performance audit. In one case, whole-of-life cost estimates were not prominent with only the acquisition cost and ‘net personnel and operating costs’ referred to in recommendations to government.74

Defence has plans to improve its whole-of-life costing

3.39 The 2015 First Principles Review found that: ‘Costing methodology does not account for all of the inputs to capability, at acquisition and over project life, and the true total cost of ownership is opaque’.75 It also found that, to manage its major equipment efficiently and effectively, Defence needs to manage on a whole-of-life basis. This requires visibility of the total cost of ownership of major equipment. Such visibility would enhance Defence’s ability to benchmark its sustainment performance against allied countries with similar equipment.

3.40 In October 2016, Defence concluded that inadequate attention to managing its equipment on a whole-of-life basis had resulted in funding shortfalls for ongoing operating, maintenance and support costs. Defence is seeking to address the issue.76 In the same month, it endorsed a total cost of ownership approach to estimating whole of life costs for all major capital equipment, infrastructure, and information and communications technology projects. The model seeks to capture the full cost of ownership throughout the life of an asset.77

3.41 Defence also decided that, in the absence of tender quality cost information it would mandate an analogous78 or a parametric79 approach to developing cost estimates for all Defence major capital equipment projects. It also agreed that deviation from the endorsed approach will be permitted only in exceptional circumstances, and with the approval of Defence’s costing authority—its Chief Finance Officer.

3.42 To provide the historical cost data to support analogous or parametric cost estimates, Defence’s Chief Finance Officer will build a database of historical costs and cost attributes. The data will be obtained from: Defence’s internal cost data; industry suppliers; industry-maintained databases; and cost data made available to Defence from the United States, United Kingdom, New Zealand and Canada.80

3.43 In developing this new approach to cost estimating, Defence sought information from Defence partner nations about the structures, data and approaches they use to develop cost estimates for major capital projects. Defence’s view is that, once implemented, this initiative will improve Defence’s cost estimates for major capital equipment projects and will bring Defence practice into line with the approach adopted by capital intensive industries and Defence partner nations. Defence has an implementation plan with target dates, concluding in July 2018.

Staffing costs are not included in Materiel Sustainment Agreements

3.44 The Mortimer Review (2008) observed that ‘through-life maintenance and support account for more than half of the DMO annual budget and involve about two-thirds of its workforce’. The cost of that workforce is not included in the internal price paid by Defence capability managers for the sustainment services provided by DMO/Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group through MSAs. Those prices comprise only the costs incurred by the relevant Systems Program Office for goods and services supplied under contract.

3.45 The First Principles Review found that, at the project level, Defence treats staff as a ‘free good’ across the department:

Employee costs are not considered part of a project’s costs and a manager cannot adjust numbers of staff based on project need. An alternative approach is to manage a total project budget that includes employee expenses. This encourages managers to exercise judgement and discretion to ‘trade’ within that operating budget (assessing their need for how many staff and what levels, skills and contracted expertise are required) to most efficiently and effectively deliver the outcomes required.81

3.46 Treating staff as costless lessens transparency of the true cost of activity and introduces risks because of the inaccurate price signals and distorted incentive structure then facing Systems Program Office managers and the capability manager. For example, this approach could make ‘in-sourced’ labour appear costless and put outsourcing at a comparative disadvantage. This risks encouraging insourcing in preference to outsourcing even where the total real cost to the Commonwealth of the former is greater.82 Defence has noted this internally (February 2017):

Any reduction of SPO [full-time equivalent staff], without a commensurate reduction of activity, will result in work being outsourced to industry and therefore increase the cost to the [Capability Manager].

Acquisition and sustainment salaries are held by [Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group] and not funded by [Capability Managers], so reductions in this Commonwealth APS workforce do not generate a saving for [Capability Managers]. … The anticipated transfer transactional workloads to industry will therefore increase the unit cost of capability delivery as far as the [Capability Managers] are concerned, regardless of the expected overall improvement in Defence’s budget.83

3.47 Systems Program Offices have had between three and four thousand staff over the last decade (Figure 3.2, below). Defence advised the ANAO that Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group’s expenses on all employees in 2015–16 were $490.4 million. In this light, the cost of those staff is a substantial omission from the apparent price of services facing the capability manager. This is especially so, given the recent observation by Defence that, in some cases, ‘[Systems Program Offices] have been spending … more money on salaries than they were on actual acquisitions or sustainment’.84

Figure 3.2: Numbers of staff in DMO/Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group Systems Program Offices, 2004–16

Note a: In compiling the data underlying this table PMKeys Reporting is not able to identify all those organisational units now recognised by Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group as Systems Program Offices. This data is likely therefore to understate the total number of staff in Systems Program Offices.

Note b: These figures include Australian Public Service and Australian Defence Force staff.

Source: Defence, PMkeys Reporting, Full-time equivalent staff in all Systems Program Offices DMO/Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group, by month, July 2004 to June 2016.

3.48 On the inclusion of staff costs in the new Product Delivery Agreements, Defence informed the ANAO in March 2017 that ‘The PDA remains under development, and it is inappropriate to speculate in any detail on how anticipated elements of the document will be used’.