Browse our range of reports and publications including performance and financial statement audit reports, assurance review reports, information reports and annual reports.

Pesticide and Veterinary Medicine Regulatory Reform

Please direct enquiries relating to reports through our contact page.

The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority’s (APVMA’s) implementation of reforms to agvet regulation and the extent to which the authority has achieved operational efficiencies and reduced the cost burden on regulated entities.

Summary and recommendations

Background

1. Across Australia, over $3 billion of agricultural chemicals, such as insecticides, herbicides and other pesticides, and veterinary medicines (together, agvet chemicals) are sold each year. The sale and use of these chemicals is regulated through a National Registration Scheme, which is established under Commonwealth, state and territory legislation. Under the scheme, the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA or the Authority) is responsible for regulating the supply of agvet chemicals up to the point of retail sale. The key regulatory activities that are undertaken by the APVMA include: assessing and registering agvet products; approving active chemical constituents; issuing permits and licences; monitoring compliance with registration, permit and licence conditions; and investigating suspected non-compliance.

2. In July 2014, a range of legislative reforms came into effect with the aim of improving the efficiency and effectiveness of the APVMA’s regulatory activities. The legislative reforms were wide-ranging and required the Authority to introduce a range of new guidance and assessment procedures, administrative requirements, and timeframes.

Audit objective, scope and criteria

3. The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness of APVMA’s implementation of reforms to agvet regulation and the extent to which the authority has achieved operational efficiencies and reduced the cost burden on regulated entities.

4. To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Have the regulatory reforms been effectively implemented?

- Are regulatory activities being delivered with greater efficiency and reduced regulatory burden on industry?

- Were sound governance arrangements established to support legislative and business process reform?

Conclusion

5. The Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority’s implementation of agvet chemical legislative reform has been mixed. While key legislative reforms were implemented by the legislated timeframe of July 2014, the full scope of the reform program is yet to be implemented more than four years since the legislative amendments were developed. Further, the Authority is not well placed to determine the extent to which reform objectives have been met in the absence of a robust set of performance measures. There is considerable scope for the APVMA to improve its management of major reform projects, particularly in the context of the Government’s decision to relocate the Authority over the next two years.

6. Projects to support the delivery of key reforms with legislated deadlines—the provision of enhanced guidance to industry, the establishment of pre-application assistance, and the introduction of an online application lodgement system—were prioritised by the APVMA and delivered on time. However, project outcomes required ongoing remediation. Reforms that did not have legislated deadlines for implementation, such as the risk-based regulatory framework and upgrades to internal IT systems to support the achievement of legislative objectives, are yet to be completed. The ongoing assessment of agvet product and chemical applications in the post-reform period has not been supported with fit-for-purpose workflow management systems and a robust quality control framework.

7. The APVMA has not established a robust performance measurement framework to measure the effectiveness of the reform program in achieving greater efficiency of its activities and in reducing the regulatory burden on industry. While performance measures that have been established by the Authority provide insights into the delivery of regulatory activities—for example the timeliness of decision-making—they do not clearly indicate the extent to which reform objectives are being achieved. The limited performance information retained by the APVMA indicates that it has not achieved greater efficiencies in the delivery of its regulatory activities and, overall, the regulatory burden on industry has not been reduced since the reforms were implemented.

8. The APVMA’s governance of the delivery of the reform program was not effective, with significant weaknesses in oversight, planning and risk management arrangements. In particular, the absence of an up to date implementation plan meant that committees established to oversee the implementation of the reform program were not well placed to effectively monitor the progress of projects and hold project managers to account. Further, while implementation risks were considered at an individual project level, they were not aggregated and integrated into an overarching risk management framework. Additionally, engagement with industry in relation to the reform program was undertaken when operational changes were yet to be finalised, which ultimately limited its effectiveness.

Supporting findings

Implementation of the reform program

9. The APVMA implemented key regulatory reforms in accordance with legislated delivery timeframes. The Authority reviewed, reprioritised and re-scoped its reform projects on a number of occasions over the course of implementation to target its efforts towards the minimum legislative requirements of the reform program. Weaknesses in project monitoring, however, meant that the APVMA lacked a clear picture of the extent to which all reform related work had been completed.

10. Key reforms, such as the provision of guidance to industry, pre-application assistance and online application lodgement, did not meet industry or internal business requirements when first implemented. The APVMA has recognised weaknesses in its arrangements for the delivery of these reforms and has undertaken remedial work to improve their effectiveness. The Authority has also revised its governance arrangements for the management of major projects.

11. The APVMA has made progress towards the establishment of a risk-based approach to the delivery of its regulatory activities including the introduction of notifiable variations for administrative registration changes and the establishment of a risk-based prioritisation process for chemical reviews. However the Authority has further work to do as it is yet to implement a risk-based assessment decision framework to target its regulatory activities.

12. While assessment decisions are, in the main, appropriately documented and based on sound evidence, they are not timely—forty per cent of the assessments examined by the ANAO were completed outside the statutory timeframes for decision-making. The establishment of a robust assurance framework for decision-making would better place the Authority to determine whether assessments are being conducted in a consistent manner and in accordance with legislated requirements.

Reform outcomes

13. The APVMA has established a corporate planning framework based on performance strategies, key result areas and performance measures. These measures established by the APVMA cover a broad range of activities but in aggregate do not enable a robust and well-rounded assessment of overall performance over time. The Authority has established appropriate monitoring arrangements in relation to the timeliness of assessments, with improved reported performance in the period 2014–2016, followed by a decline in the six months to March 2017. These fluctuations in the timeliness of assessments have taken place while a backlog of overdue assessments has grown during 2016.

14. The APVMA has not demonstrated greater efficiencies in the delivery of regulatory activities following its implementation of the regulatory reform program. While the Authority has not established a robust means to assess the extent to which efficiencies have been achieved, the ANAO’s analysis of available performance data and industry feedback indicates a decline in efficiency since 2014.

15. Overall, feedback provided by industry stakeholders indicates that the regulatory burden on industry has not reduced following the implementation of regulatory reform, while noting some improvements in relation to individual measures such as pre-application assistance and online lodgement. The absence of specific performance measures to assess regulatory burden makes it more difficult for the APVMA to ascertain changes in regulatory burden arising from the roll-out of reform initiatives.

Governance arrangements

16. The oversight arrangements to monitor the implementation of the reform program were not effective. The APVMA’s governance forums lacked continuity and did not facilitate assurance on the progress of work, ultimately contributing to poor or incomplete implementation outcomes for some projects.

17. The APVMA did not establish an effective planning framework to guide the implementation of the reform program. In the absence of such a framework, the numerous governance committees that were established over the course of reform program implementation lacked an appropriate basis on which to oversee progress and hold project managers to account.

18. The risks to the effective implementation of the reform program were poorly managed by the APVMA. While an appropriate risk management framework is in place, high level business risk reviews were not conducted regularly and risks to the implementation of the reform program were not adequately managed. Further, risk management at the individual project level was inconsistent and treatments for risks in relation to the retention of staff capability have not been effective.

19. Industry stakeholders were engaged during the implementation of the reform program via a range of information and training sessions, but delays in the finalisation of reform projects limited the extent to which specific changes at the operational level were communicated. The feedback provided by industry stakeholders to the ANAO on the APVMA’s engagement approach was mixed.

Recommendations

Recommendation No. 1

Paragraph 2.47

The Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority should implement an internal quality framework to provide an appropriate level of assurance that its assessments are undertaken in a consistent manner and made in accordance with agvet chemical legislation.

Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority's response: Agreed.

Recommendation No. 2

Paragraph 3.28

The Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority should establish and monitor an appropriate set of measures and targets to assess the extent to which it is improving the effectiveness and efficiency of its regulatory activities through its ongoing reform agenda.

Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority's response: Agreed.

Recommendation No. 3

Paragraph 4.14

The Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority should improve its governance of the implementation of major reforms, including the maintenance of an oversight body with clearly defined responsibilities and robust project monitoring arrangements.

Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority's response: Agreed.

Recommendation No. 4

Paragraph 4.38

The Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority should implement a structured and systematic approach to identifying and responding to emerging business risks.

Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority's response: Agreed.

Summary of entity response

20. The APVMA’s summary response to the report is provided below, while its full response is at Appendix 1.

The agency welcomes the audit by the ANAO of the effectiveness of implementation of reforms to agricultural and veterinary (agvet) chemical regulation which came into effect in July 2014. The agency acknowledges the findings and areas for improvement identified in the ANAO Report. The agency notes, however, that for the scale of reform undertaken the implementation timeframes were challenging and resourcing required to fully deliver within these timeframes was limited.

The agency notes the transition from pre-July 2014 to post-July 2014 reform arrangements was achieved without significant disruption to service delivery and involved an ongoing program of business improvement. Having moved through the transition period, the reforms were moving into a more mature phase of implementation in mid-to-late 2016, with 78 per cent of product applications processed within timeframe in the June quarter 2016 and 83 per cent in the September quarter 2016.

The agency accepts all four recommendations with action already taken or underway to implement improvements consistent with the recommendations. This includes improvements in quality assurance processes for application assessment; better documentation of business processes to support consistency; and strengthening risk management, governance and performance monitoring frameworks. The agency is also implementing a major program of business process reform to improve the efficiency of its service delivery.

1. Background

Introduction

1.1 Across Australia, over $3 billion of agricultural chemicals, such as insecticides, herbicides and other pesticides, and veterinary medicines (together, agvet chemicals) are sold each year. The supply and use of these chemicals is regulated through a National Registration Scheme, which is established under Commonwealth and state and territory legislation.1 Under the scheme, the:

- Australian Government’s Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA or the Authority) regulates the supply of agvet chemicals up to the point of retail sale;

- states and territories are responsible for controlling the use of agvet chemicals once they are sold; and

- Australian Government Department of Agriculture and Water Resources (Agriculture) is responsible for legislative and policy oversight.

Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority

1.2 The APVMA’s purpose is to ‘evaluate the safety and performance of chemicals intended for sale in Australia to ensure that the health and safety of people, animals, crops and the environment are protected’. The role of the APVMA is governed by a legislative framework (see Table 1.1 on the following page). The key regulatory activities undertaken by the Authority include: assessing and registering agvet products; approving active chemical constituents; issuing permits and licences; monitoring compliance with registration, permit and licence conditions; and investigating suspected non-compliance.

1.3 As at February 2017, the APVMA had registered over 13 000 products and chemicals for over 900 businesses, individuals and organisations. The APVMA receives around 5000 applications each year, with approximately 70 per cent of applications seeking to vary an existing registration or approval, or produce a copy of an existing product. The APVMA has around 200 staff, including around 100 regulatory scientists, 30 legal and compliance staff, 40 corporate staff and 30 executive and administrative staff. The Authority’s revenue in 2016–17 was $36.4 million, with funding primarily obtained through cost recovery arrangements.

Table 1.1: Agvet chemical legislative framework

|

Legislation |

Purpose |

|

Agricultural and Veterinary Chemicals (Administration) Act 1992 |

Establishes the APVMA as an independent statutory authority of the Commonwealth responsible for the regulation and control of agvet chemicals in Australia up to the point of retail sale. |

|

Agricultural and Veterinary Chemicals Code Act 1994 [Agvet Code] |

Enables the APVMA to: evaluate, approve or register and review active constituents and agvet products; issue permitsa; license the manufacture of chemical products; and conduct compliance and enforcement activities with respect to the Agvet Code. |

|

Agricultural and Veterinary Chemicals Act 1994 |

Enables the Agvet Code to have effect and provides that the Agvet Code is to apply as a law of the participating jurisdictions. |

|

Agricultural and Veterinary Chemical Products (Collection of Levy) Act 1994 |

Contains measures that allow for the assessment and collection of levies in regard to agvet products registered for use in Australia. |

|

Agricultural and Veterinary Chemicals (Administration) Regulations 1995 |

Prescribes the fees for export certificates and the form of search warrant to be used when there is a suspected offence in relation to the importation, manufacture or exportation of agvet chemicals. |

|

Agricultural and Veterinary Chemicals Regulations 1999 |

Prescribes functions that enable the Director of Public Prosecutions of the Commonwealth to bring prosecutions and proceedings for offences against the Agvet Code or the Agvet Regulations. |

|

Agricultural and Veterinary Chemicals Code Regulations 1995 |

Prescribes detailed provisions of the Agvet Code. |

|

Agricultural and Veterinary Chemical Products (Collection of Levy) Regulations 1995 |

Prescribes the state laws under which an agvet product is registered under the Collection of Levy Act 1994 and specifies the rate of levy applicable. |

Note a: The APVMA may issue permits for non-commercial minor use, emergency and research purposes.

Source: APVMA.

Legislative reform

1.4 Agvet chemical regulation has been subject to a series of reviews and legislative reforms over recent years, with these reforms designed to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of regulatory activities.2 Following the 2010 federal election, the Government directed Agriculture to consult with the agvet chemical industry on the development of measures to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of regulatory arrangements and provide better protection for human health and the environment. To inform the development of new measures, Agriculture released a discussion paper and met with industry stakeholders.3

1.5 The subsequent report prepared by Agriculture, Better Regulation of Agricultural and Veterinary Chemicals, highlighted a range of issues including:

- the absence of: a clear risk-based regulatory framework; statutory timeframes for the review of registered products and chemicals; and intermediate enforcement measures between the extremes of warning letters and criminal prosecution;

- inefficient preliminary assessment arrangements; and

- delays to the completion of assessments due to applicants providing additional information during the assessment process.

2014 legislative reforms

1.6 The Agricultural and Veterinary Chemicals Legislation Amendment Act 2013 and regulations were designed to address the issues outlined in the department’s review and to ‘encourage the development of newer and safer chemicals by providing more flexible and streamlined regulatory processes with higher levels of transparency and predictability for businesses seeking approval for agvet chemicals to enter the market’. The key reforms that the APVMA was required to implement from 1 July 2014 included:

- new regulatory guidance to industry under the reformed legislative arrangements;

- a structured, upfront pre-application assistance scheme for applicants;

- a system to electronically receive all applications online;

- stricter preliminary assessment arrangements that focus on basic application requirements (restricting the ability of the applicant to rectify a defect in their application during this phase of assessment);

- revised maximum assessment timeframes based on the type of application being made, with increased time for the assessment of certain product and chemical applications;

- additional requirements for the review of registered products and chemicals (such as the development of work plans for each review) and statutory timeframes for completing chemical reviews; and

- procedural, technical and transitional arrangements, including limiting the acceptance of additional material from applicants and introducing requirements to provide notices of certain proposed decisions to applicants.4

1.7 In addition, the new legislation provided two mechanisms for the APVMA to target its resources more effectively. Firstly, by allowing the APVMA to implement a risk-based regulatory framework to guide the conduct of regulatory activities resources can be directed towards areas of high risk. Secondly, the introduction of a range of new enforcement powers supports a more graduated response to non-compliance than was possible previously.

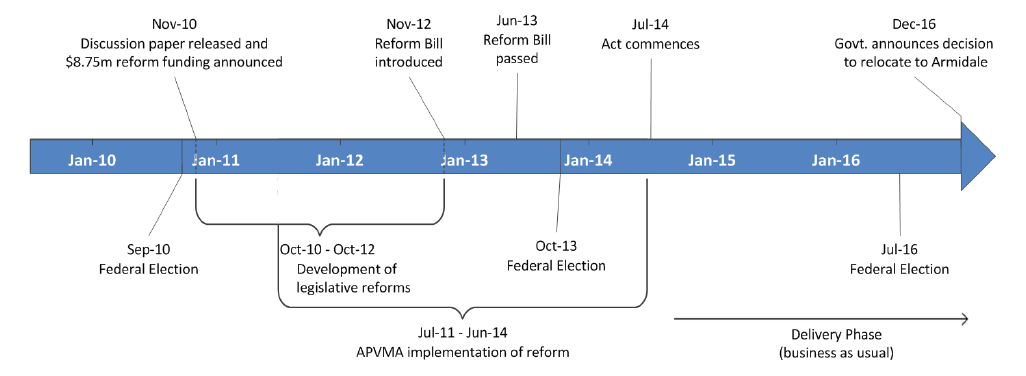

1.8 The APVMA commenced projects to implement the legislation during the development of the legislative reforms. An overview of the timeline for the development and implementation of the 2014 agvet chemical legislative reforms is provided at Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1: Timeline of the development and implementation of the 2014 agvet chemical legislative reforms

Source: ANAO based on APVMA and departmental information.

Recent developments

Agricultural Competitiveness White Paper

1.9 The Government’s 2015 Agricultural Competitiveness White Paper, which sets out the Australian Government’s roadmap of actions to grow the agriculture sector in Australia, noted that agvet chemical regulation imposes a heavy regulatory burden on industry that is often disproportionate to the risks that products pose. The White Paper also outlined the Government’s intentions for further reform including: limiting pre-market assessments of low and medium risk products; recognising assessments from accredited third party suppliers and trusted chemical regulators; and exploring opportunities to improve post-market compliance and national control of chemical use with co-regulators.5 In 2016, the Government allocated $7.3 million over four years to the APVMA to progress these further reforms.

Relocation of the regulator

1.10 On 23 November 2016, the Minister for Finance made a Government Policy Order under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 to relocate the APVMA from Canberra to a regional community. The Order is supported by additional funding of $25.6 million to relocate the Authority to Armidale, New South Wales, to be completed in 2019.6

Further reviews

1.11 In October 2014, COAG agreed to consider changes to the regulatory framework governing chemicals to improve efficiency. The Department of Industry and Science, on behalf of COAG engaged consultants in 2015 to review Commonwealth chemicals assessment functions with a focus on complementary regulatory and administrative functions. The different regulatory requirements for chemicals and chemical products administered by the APVMA, the National Industrial Chemicals Notification and Assessment Scheme, the Therapeutic Goods Administration, Food Standards Australia New Zealand, and the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission were identified. The report is yet to be finalised, pending further consideration by COAG.

1.12 In November 2015, the Treasurer requested the Productivity Commission to undertake an inquiry into the regulatory burden imposed on Australian farm businesses focusing on regulation with a material impact on domestic and international competitiveness. The Commission’s report of March 2017 recommended that the APVMA increase its use of international evidence in its assessments.7

1.13 In December 2015, Agriculture commissioned a review of the duplication of effort and unnecessary costs on industry associated with their compliance with agvet chemical legislation and the Work Health and Safety Act 2011.8 The review was completed in August 2016 and made four recommendations including that the APVMA: continue to work with Safe Work Australia9 to assist industry on labelling requirements; consider work health and safety labelling as part of any future changes to agvet labelling requirements; and apply discretion where possible to enable veterinary chemical producers to re-label products at the point of supply.

Upcoming reviews

1.14 The Agricultural and Veterinary Chemicals Legislation Amendment Act requires a review of the agvet regulatory reforms to be completed by July 2019. In addition, the Agricultural and Veterinary Chemicals (Administration) Act 1992 requires a comprehensive review of the suite of agvet legislation—over 20 instruments—to be completed by July 2024.

Audit approach

1.15 The objective of the audit was to assess the effectiveness of APVMA’s implementation of reforms to agvet regulation and the extent to which the authority has achieved operational efficiencies and reduced the cost burden on regulated entities. To form a conclusion against this objective, the ANAO adopted the following high-level criteria:

- Have the regulatory reforms been effectively implemented?

- Are regulatory activities being delivered with greater efficiency and reduced regulatory burden on industry?

- Were sound governance arrangements established to support legislative and business process reform?

1.16 The scope of the audit included an examination of the measures established by the APVMA to give effect to the 2014 reforms and their impact on achieving efficiencies, lowering the burden on industry and improving regulatory outcomes. The audit considered the implementation of reform in the context of the Government’s separate policy of relocating the regulator and the APVMA’s management of business continuity risks associated with the move. The audit did not examine functions that do not directly relate to the objectives of the reforms, such as the collection of fees from industry.

1.17 In conducting the audit, the ANAO examined the APVMA’s internal records, systems and procedures relating to the implementation of reform, including governance reviews, engagement with industry, assessment decision-making and project documentation. The ANAO also interviewed APVMA staff, stakeholders, and co-regulators and conducted an online survey of regulated entities to gain an industry perspective on regulation.10

1.18 The audit was conducted in accordance with ANAO Auditing Standards at a cost to the ANAO of approximately $427 000.

1.19 The team members for this audit were Mark Rodrigues, Alicia Vaughan, Vinesh Abbott, Jillian Blow, Jessica Carroll and Sally Ramsey.

2. Implementation of the reform program

Areas examined

The ANAO examined the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority’s (APVMA’s or the Authority’s) development of key initiatives to implement legislative reform, including the provision of guidance to industry, changes to business processes and the transparency and timeliness of regulatory decision-making.

Conclusion

Projects to support the delivery of key reforms with legislated deadlines—the provision of enhanced guidance to industry, the establishment of pre-application assistance, and the introduction of an online application lodgement system—were prioritised by the APVMA and delivered on-time. However, project outcomes required ongoing remediation. Reforms that did not have legislated deadlines for implementation, such as the risk-based regulatory framework and upgrades to internal IT systems to support the achievement of legislative objectives, are yet to be completed. The ongoing assessment of agvet product and chemical applications in the post-reform period has not been supported with fit-for-purpose workflow management systems and a robust quality control framework.

Areas for improvement

The ANAO has made one recommendation aimed at strengthening arrangements to support transparent, accountable and consistent decision-making. There is also scope for the APVMA to:

- monitor the outcomes of applications following the use of pre-application assistance to inform in the development of appropriate guidance for industry; and

- develop intelligence collection and analysis arrangements to strengthen the implementation of its graduated compliance and enforcement strategy.

Were key reform requirements identified and implemented on time?

The APVMA implemented key regulatory reforms in accordance with legislated delivery timeframes. The Authority reviewed, reprioritised and re-scoped its reform projects on a number of occasions over the course of implementation to target its efforts towards the minimum legislative requirements of the reform program. Weaknesses in project monitoring, however, meant that the APVMA lacked a clear picture of the extent to which all reform related work had been completed.

2.1 As outlined in Chapter 1, the Department of Agriculture and Water Resources led the process to design the agvet chemical legislative amendments with input from industry and the APVMA. The design process was informed primarily through the development and release of a discussion paper in 2010, with feedback sought from relevant stakeholders.

2.2 The legislative amendments covered a broad range of the APVMA’s regulatory activities. By July 2014, the Authority was to have introduced key requirements including:

- updated guidance for industry;

- a pre-application assistance scheme;

- an online application system;

- stricter preliminary assessment arrangements that focus on basic application requirements (restricting the ability of the applicant to rectify a defect in their application during this phase of assessment);

- revised maximum assessment timeframes;

- work plans for the chemical reviews and new timeframes for those reviews; and

- procedural, technical and transitional requirements with respect to the assessment of applications.

2.3 Other 2014 reforms without a prescribed deadline provided for the APVMA to implement a risk-based regulatory framework and exercise a graduated range of enforcement powers. In anticipation of the resourcing requirements necessary to support the implementation of the reforms and to upgrade relevant IT infrastructure, the Government allocated the APVMA an additional $8.75 million over the period from 2010–11 to 2013–14.11

2.4 The 2014 legislative amendments were introduced into Parliament in November 2012 with a commencement date of July 2013.12 In June 2013, the House of Representatives approved minor amendments to the Bill, including delaying commencement to July 2014. The bill was passed on 28 June 2013.

Prioritisation of reforms

2.5 To prepare for the expected regulatory reforms, the APVMA developed a series of projects in 2011 to be monitored by its executive management committees.13 For the eight key reform related projects planned14, the APVMA has retained limited documentation regarding the progress made during 2012. By July 2013, the projects had been subsumed into five key areas of focus: pre-application assistance; registration assessment; chemical review; re-registration/ re-approval; and compliance. The APVMA identified complementary major projects that were pertinent to the successful delivery of reform across these areas relating to ‘IT transformation’, internal and external regulatory guidance and a leadership development program for senior staff.

2.6 Further revisions to the APVMA’s approach to delivering reform were made in late 2013, with the APVMA identifying reform elements with legislated implementation deadlines and areas where implementation could be delayed. In January 2014, the APVMA considered that ‘core implementation projects’ to support the implementation of the reform program were not on schedule and re-prioritised and re-scoped projects to focus on the minimum requirements that could be achieved within legislated deadlines. In March 2014, the Authority had 13 reform related projects underway. By May, seven streams of work had been identified: pre-application assistance; preliminary assessment; evaluation; application finalisation; permits; reconsideration; and compliance. Table 2.1 outlines the main changes in project coverage over time.

Table 2.1: Iterations of reform project coverage over time

|

Time |

Reform project coverage |

Additional comments |

|

July 2011 |

8 key projects |

Legal Interaction, Expert Advice, Risk Framework, Overseas Assessment, Science Panel, Re-registration, Compliance and Business Improvement |

|

July 2013 |

5 key areas |

Pre-application Assistance, Registration Assessment, Chemical review, Re-registration/Re-approval; and Compliance |

|

November 2013 |

10 key projects |

Regulations Guidelines Content Project, Compliance, Legislative Reform Training Project, Legal Implementation, Pre-Application Assistance, Registration Application Assessment, Reform Communication Implementation, Website Redevelopment, Chemical Review and IT Projects |

|

January 2014 |

13 key projects |

Consultation Project and Permits were added. Legal Implementation was separated into two projects |

|

March 2014 |

13 key projects |

Regulations Guidelines Content Project was considered complete. Case Management was added. |

|

May 2014 |

7 main streams |

Pre-application assistance, preliminary assessment, evaluation, application finalisation, permits, reconsideration, and compliance. |

Source: ANAO analysis based on APVMA documentation.

Implementation status as at July 2014

2.7 The APVMA was unable to provide a complete set of documents relating to the implementation of reform projects. Documentation retained by the APVMA indicates that the Authority had implemented key reforms on time, including the establishment of new assessment procedures, a pre-application assistance service, new regulatory guidance, and online application submission portal. The ANAO’s review of the status of implementation, as at 1 July 2014, is outlined at Table 2.2.

Table 2.2: ANAO analysis of the APVMA’s implementation of reform, as at 1 July 2014

|

Key reforms |

Implementation status at 1 July 2014 |

Evidence supporting the completion of reforms |

|

Stricter preliminary assessment arrangements (new timeframes and ‘shut-the-gate’ provisions) |

Largely complete |

s.6A guideline in place by 1 July 2014. Work instruction for Preliminary Assessment issued 1 July 2014. At June 2015, Decision Maps relating to preliminary assessment remained in development. |

|

Revised maximum assessment timeframes |

Insufficient documentation to verify |

N/A |

|

New chemical review arrangements |

Completed |

New timeframes outlined on website by 1 July 2014. Internal progress monitoring indicates work instructions and work plan templates were updated by 1 July 2014. Stocktake review also noted that work instructions were in place by 1 July 2014. |

|

Pre-application assistance |

Complete |

Internal progress monitoring. Work instruction issued 1 July 2014. |

|

Online application submission portal |

Largely complete |

Post implementation remediation and monitoring. |

|

Regulatory guidance |

Complete |

Internal monitoring indicates new website (including s.6A guidelines) launched by 1 July 2014. |

|

Procedural, technical and transitional requirements |

Insufficient documentation to verify |

Internal monitoring noted 93 per cent completion of Registration Application Assessment project at 7 May 2014 (including work to support implementation such as staff training). s.6A guidelines for re-categorising applications, altering applications and issuing section 159 notices in place by 1 July 2014. Legislative instrument detailing Application Requirements issued 26 June 2014. |

Source: ANAO analysis based on APVMA documentation.

2.8 The limited monitoring of the status of reform projects that had been undertaken by the APVMA in early July 2014 indicates that, while key reforms with a legislated deadline had been implemented, the APVMA did not have a clear picture of the extent to which all reform related work had been implemented.

2.9 In October 2014, the Authority commenced a ‘reform legislation implementation stocktake’ to identify incomplete work and any matters additional to what was required under the new legislative requirements. The stocktake, which was finalised in June 2015, noted the significant work undertaken to implement the key reforms, although some reform related work was not completed on time. These outstanding areas included: updating internal work instructions, procedures and decision maps; and internal IT systems to support reform. The stocktake also identified a lack of documentation to substantiate progress against some reform projects.

Reform activities post July 2014

2.10 As at February 2017, the APVMA had ongoing projects related to the 2014 reforms, including the Lower Regulatory Approaches to Registration Project (continuing from the previous Risk-based Assessment Framework Project), and an Internal IT Portal Upgrade Project. These projects are discussed further in paragraphs 2.22 and 2.28–2.29.

Were key reforms effectively delivered?

Key reforms, such as the provision of guidance to industry, pre-application assistance and online application lodgement, did not meet industry or internal business requirements when first implemented. The APVMA has recognised weaknesses in its arrangements for the delivery of these reforms and has undertaken remedial work to improve their effectiveness. The Authority has also revised its governance arrangements for the management of major projects.

2.11 As outlined earlier, the APMVA was required to implement key reforms by 1 July 2014. For these key reforms, the ANAO reviewed the APVMA’s implementation of new regulatory guidance to industry, a pre-application assistance service, and online application submission tools.

Industry guidance

2.12 To support the implementation of the broader reform program, the APVMA commenced a Regulatory Guidelines Project to replace the previous Manual of Requirements and Guidelines in 2013. The aim of the project was to redevelop website content to provide comprehensive information to industry stakeholders about the registration of products, the approval of chemicals, and management of applications. Draft guidelines were released in January 2014 for public consultation, with the revised guidelines released on the APVMA’s website on 1 July 2014.15

2.13 Further, formal guidelines have been released under s.6A of the Agvet Code which outline, for APVMA officers and industry stakeholders, the principles and processes for the APVMA’s functions and powers under the Agvet Code and the Agvet Code Regulations. As at 1 July 2014, the Authority had developed 13 s.6A guidelines, covering topics such as ‘Preliminary Assessment’ and ‘Altering Applications’.

2.14 In relation to the quality of the guidance material prepared, the APVMA’s 2015 Stocktake noted staff concerns about missing content, errors and the lack of a user friendly structure. The review also found that there were a ‘number of sections of the legislation for which no reference [could] be found on the website’ and a need to update some of the content.16 It is unclear if these issues had been addressed because the Stocktake did not identify which sections of the legislation were absent from the website and the APVMA has not retained documents to demonstrate rectification of these issues.

2.15 The responses to the ANAO’s survey of regulated entities indicated mixed views on the quality of APVMA’s guidance materials. While around one third of respondents considered that the APVMA’s website was easy to navigate and that its guidance to industry was clear, around 40 per cent considered that guidance was unclear. Respondents’ views on the range of coverage of the APVMA’s guidance was more positive, with around 42 per cent considering that the APVMA’s written advice covered a sufficient range of topics (a further 30 per cent not expressing a strong view on the matter).

2.16 The APVMA has continued to develop its guidance for industry into 2017. In December 2016, the APVMA developed a project plan for ‘Transforming the User Experience’, following a website usability review. Key deliverables for the project included improved search and web functionality and tailored guidance to support the ‘top 20’ most common application types.

Pre-application assistance

2.17 From 1 July 2014, potential applicants could obtain assistance from the APVMA to prepare their applications under the Pre-application Assistance (PAA) Scheme. The APVMA reviewed the service in October 2014, following concerns raised by industry stakeholders. The review found that: the PAA had not delivered the service and benefits as intended by the reforms; and the Authority had failed to meet the reasonable expectations of industry. The review also found that the scheme lacked: clarity about the objective; a consolidated statement of internal roles and responsibilities; reporting and monitoring; sound business workflow processes; and a robust quality assurance mechanism.

2.18 The 40 recommendations made by the review were generally addressed by key changes introduced by the APVMA in November 2015, when the Authority:

- introduced of a tiered system to manage different types of requests for assistance;

- offered applicants the option to request face-to-face meetings and the appraisal of trial protocols (which was previously available only through technical assessments); and

- simplified the fee structures.

2.19 The ANAO reviewed APVMA data to determine the extent to which applications for pre-application assistance were finalised within the Authority’s target timeframes. The ANAO’s analysis indicated that of the 146 applications received from November 2015 and finalised by December 2016, 96 applications (66 per cent) were not finalised within established PAA timeframes, and were on average, 43 days overdue. The APVMA has not analysed PAA data to identify the outcomes of applications submitted following use of the scheme. There would be benefit in the APVMA monitoring the progress of applications following applicants’ use of the PAA to better measure the extent to which it is achieving its objective.

2.20 Of the survey responses received by the ANAO, 25 per cent considered that pre-application assistance had significantly or somewhat reduced time or costs for their organisation in 2014, while 29 per cent considered that there was no impact.

Online application lodgement

2.21 From 1 July 2014, applications could be submitted online. However, there were extensive weaknesses in the APVMA’s management of the project. Specifically, core IT project management practices such as technical and user acceptance testing was not undertaken prior to releasing new applications into production. In addition, key project documentation was either not prepared or was incomplete.17

2.22 The APVMA has recognised that there are weaknesses in its governance of ICT projects. To address these weaknesses, the Authority has established new governance arrangements for ICT projects in September 2016 and developed key supporting ICT planning documents such as a Project Management Framework (June 2016), a Project Management Plan (in draft at November 2016), and a new ICT Strategic Plan (October 2016). The most recent internal portal project deliverable, the Permits Module, was completed by the APVMA in May 2016. The module was delivered to scope and on budget.

2.23 As noted in paragraphs 2.37–2.41, the APVMA’s assessment of applications is poorly supported by internal workflow management systems. Current systems in place do not enable the direct transfer of records and data between assessment staff and the tracking of assessment progress is fragmented.

Industry views

2.24 The ANAO received generally positive feedback from stakeholders in relation to the online application lodgement capability. Responses to the ANAO’s survey indicated that the new functionality had significantly or somewhat reduced time or costs for 40 per cent of participating organisations. There were, however, 19 per cent of respondents that reported that the new functionality had somewhat or significantly increased time or costs for their organisation.

Are regulatory activities graduated in proportion to risk?

The APVMA has made progress towards the establishment of a risk-based approach to the delivery of its regulatory activities including the introduction of notifiable variations for administrative registration changes and the establishment of a risk-based prioritisation process for chemical reviews. However the Authority has further work to do as it is yet to implement a risk-based assessment decision framework to target its regulatory activities.

2.25 The agvet chemical legislative amendments also provided for the APVMA to implement a risk-based regulatory framework, new arrangements for chemical review and exercise a graduated range of new enforcement powers. The ANAO assessed the extent to which these reforms have contributed to a more graduated regulatory approach in proportion to risk.

Implementation of risk-based approach to regulation

2.26 The APVMA’s work towards implementing a risk-based approach to regulation has progressed slowly over a number of years. A 2011 legislative reform plan produced by the Authority included the development of a ‘fully documented and published Risk Analysis Framework’ to ‘improve transparency of APVMA operations, facilitate the submission of quality applications, enhance stakeholder and community confidence and drive alignment of regulatory effort with the degree of risk’.

2.27 In 2013 the APVMA commissioned a review of the application of risk proportionate regulatory processes for chemicals regulated in Australia including the Therapeutic Goods Administration and Food Standards Australia New Zealand. The review identified options for reducing regulatory burden on industry through the application of risk-based principles. In 2014, the APVMA commissioned the Centre of Excellence for Biosecurity Risk Analysis (CEBRA)18, to develop a conceptual framework underpinning a risk-based assessment decision framework. The resulting report outlined the development and testing of a screening level risk assessment tool for agvet chemicals. The APVMA intended to use the report to develop new risk-based measures and implement ‘low hanging fruit’ by July 2016, however no significant regulatory changes directly arose from the CEBRA engagement.

2.28 To date, a key work to implement a risk based regulatory approach by the APVMA has been through the ‘Lower Regulatory Approaches to Registration’ (LRAR) project in 2015. Key outcomes of this project have been:

- the removal of assessments for five types of variations (for example, changing the manufacturer’s address or storage and disposal instructions)19; and

- streamlined processes (‘fast-tracking’) for low risk applications, such as repack registrations, in prescribed circumstances.

2.29 The LRAR project also aims to: expand fast-track assessments to other application types; develop and publish risk assessment manuals; and develop, in consultation with Agriculture, future legislative reforms to the prescribed application categories under the agvet Code. In addition to the LRAR Project, the APVMA is undertaking two joint projects with Agriculture to improve farmers’ access to chemicals.20 Collectively these projects aim to improve access to chemical products for minor use by streamlining registration requirements and reducing the regulatory effort.

Chemical Review (Reconsideration)

2.30 As part of the 2014 reforms21, the APVMA implemented a documented risk-based approach to the reconsideration of products and chemicals that had been registered. In November 2014, the APVMA held a two-day chemical review prioritisation workshop with Australian, state and territory government co-regulators and compiled a list of 19 chemicals or types of chemicals for review, reduced from the previous number of 39. The remaining 20 chemicals were either no longer considered to require review, or concerns were to be managed using alternate agvet regulatory processes. The APVMA subsequently consulted the public, industry and government entities to prioritise these chemicals, which included an invitation for submissions from April to June 2015. Following consultation with relevant stakeholders, five chemicals were prioritised for detailed scoping and the remainder were scheduled for re-evaluation by December 2016.22

Compliance and enforcement activities

2.31 As noted in Chapter 1, the APVMA is responsible for regulating agvet chemicals up to and including the point of sale. This responsibility involves monitoring compliance with agvet legislation to identify the supply of unregistered products, the use of unapproved labels, unfounded advertising claims, and chemicals that do not conform to standards. The APVMA’s activities to identify non-compliance include post-border inspections, audits of manufacturers and labels, and presumptive chemical testing. The 2014 reforms provided the Authority with an expanded range of compliance and enforcement powers, including penalty infringement notices, enforceable undertakings, substantiation notices, suspensions/cancellations of approval/registration and monitoring and investigation warrants, in addition to letters of warning and criminal prosecution.

2.32 To facilitate the use of its new enforcement powers, the APVMA developed a Compliance and Enforcement Strategy for 2015–17 and a Compliance Plan for 2016–17, which outline a range of graduated education, engagement, compliance and enforcement activities. The Strategy provides for a risk-based approach to compliance, including the use of intelligence analysis to underpin its broader compliance activities, and the establishment of formal arrangements to undertake joint investigations and information sharing with partner agencies, such as states and territories, which are responsible for regulating the use, transport and storage of agvet chemicals.

2.33 However, the APVMA’s compliance and enforcement activities are not supported by a fit-for-purpose investigation case management system and procedures for the collection and use of compliance intelligence. Draft work instructions and intelligence reporting and referral templates were developed in 2014 and 2015 but were not operationalised. Intelligence sharing arrangements with other jurisdictions are also yet to be formalised. As a result, the APVMA’s 230 investigations per year have been largely reactive, in response to reports of non-compliance submitted by the public on its website. The current lack of formal procedures and appropriate systems has the potential to undermine the effectiveness of the APVMA’s compliance program.23

2.34 Notwithstanding these potential limitations to its compliance activities, the APVMA has exercised its expanded enforcement powers since July 2014. In 2015–16, the Authority issued one statutory notice, six formal warnings, two infringement notices (totalling $27 000) and one investigative warrant. The development of appropriate intelligence collection and analysis arrangements would better place the APVMA to implement its graduated compliance and enforcement strategy.

Industry views

2.35 Of the regulated entity responses to the ANAO’s survey, 38 per cent agreed or strongly agreed with the statement: ‘Within its legislative constraints, APVMA’s regulatory effort is generally targeted towards the most important issues’. Of the remaining responses, 2 per cent did not agree with this statement and 30 per cent did not express a strong view on the matter.

Are assessment decisions appropriately documented, evidence-based and timely?

While assessment decisions are, in the main, appropriately documented and based on sound evidence, they are not timely—forty per cent of the assessments examined by the ANAO were completed outside the statutory timeframes for decision-making. The establishment of a robust assurance framework for decision-making would better place the Authority to determine whether assessments are being conducted in a consistent manner and in accordance with legislated requirements.

2.36 Applications for the registration of agvet chemicals are managed by the APVMA’s Case Management and Administration Unit, with all applications to undergo preliminary assessment to determine if basic documentary requirements have been met. The assessment process includes the production of technical reports that may cover toxicology, workplace health and safety, residues, trade, efficacy (crop or host animal safety), environment and chemistry and manufacture.24 The APVMA may determine whether further information from the applicant or a re-categorisation of the application is required at any stage over the assessment process.

Documentation of decision-making

2.37 The retention of appropriate documentation to evidence the decision-making process supports accountability and positions regulators to explain and defend their decisions. The APVMA has recorded assessment outcomes against core application requirements25, but the approval of final assessment decisions was not recorded consistently. Of the 100 major assessments sampled by the ANAO, seven assessments were identified where the decision was not recorded on the decision document (alternative records had been retained to evidence the delegate’s approval). To provide greater assurance regarding delegate decision-making, there would be merit in the APVMA ensuring that delegate decisions are recorded on each decision document.

Assessment delays

2.38 The processing of applications is shared across a number of areas of APVMA including Case Management and Administration Unit, risk managers, delegates and scientific assessment areas. The Authority has not, however, assigned responsibility for end-to-end timeframe management.

2.39 The statutory period in which the APVMA is required to complete assessments ranges from two months to 25 months depending on the application type. Of the 100 assessments reviewed by the ANAO, 60 applications were found to have been completed on time, with 40 overdue—ranging from two weeks to 10 months. While the reasons for overdue assessments varied across the application types and assessment components, more common reasons included:

- delays in receiving and reviewing technical assessments;

- misplaced application material (including, in one case, confidential commercial information26);

- staff absences27; and

- delays in recognising the payments from applicants.28

Workflow management

2.40 The APVMA use a number of automated and manual systems to manage applications, including its internal portal, which is currently subject to a major redevelopment. In general, the assessment of applications is poorly supported by existing systems. In particular, the existing portal does not include sufficient information on the progress of assessments to support effective monitoring. For example, information on the status of technical reviews and whether additional information from the applicant is outstanding is not retained. To confirm the status of applications and to track the progress of assessments, assessors are required to review standalone spreadsheets.

2.41 There are also functional limitations relating to the operation of the external portal. For example, the external portal does not provide sufficient information to applicants to enable them to track the progress of their applications. When contacted, the APVMA responds to applicant queries with general information on the assessment, but does not provide an estimate of the likely completion timeframe or explain those factors that impact on the assessment timeline. As a consequence, applicants are not provided with clarity surrounding expected assessment completion dates, which ultimately makes it more difficult for them to schedule further work to prepare for the release of relevant products.

Requests for further information and re-categorisations

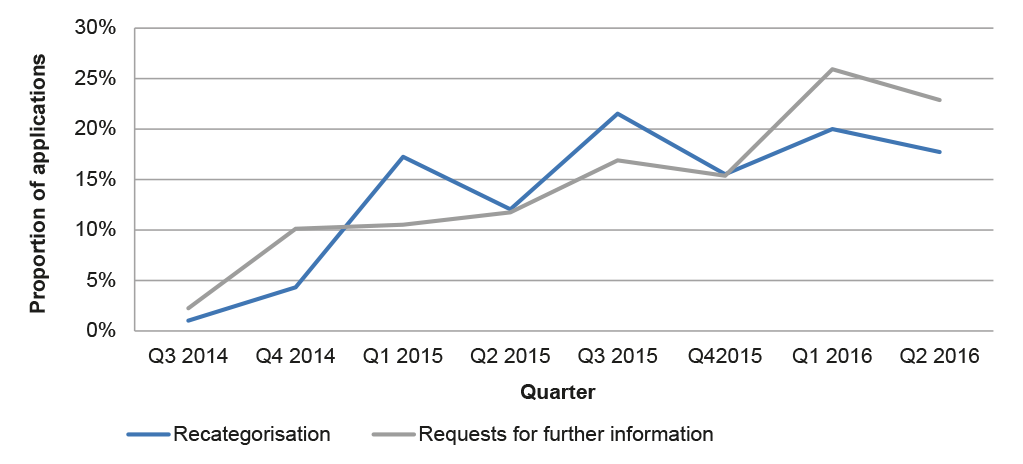

2.42 Almost half of the 100 applications examined by the ANAO were subject to a request for further information (27) or re-categorisation (22).29 Data on all major applications submitted after July 2014 indicates similar rates of requests for further information and re-categorisation, and an increasing trend over time (Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1: Requests for further information and re-categorisation, 2014–2016

Source: ANAO analysis of APVMA information.

2.43 The increasing proportion of requests for further information and re-categorisations suggests that existing guidance for applicants relating to the application requirements may need to be reviewed. The introduction of additional pre-application guidance to applicants as part of the reform program was designed to better place applicants to submit complete and accurate applications. Two applications in the sample examined by the ANAO involved the use of Pre-application assistance under the pre-November 2015 arrangements (outlined in 2.18). Of these, one exceeded the statutory decision-making timeframe and one was on time but subject to a request for further information. As noted at paragraph 2.19, there would be merit in the APVMA monitoring the rate of requests for further information and re-categorisations to better target its guidance to industry.

Quality control and review

2.44 The APVMA informed the ANAO that some assessment areas within the Authority undertake peer review of technical assessment decisions, although quality review processes are not integrated across assessment streams and documented. The absence of a fit-for-purpose internal quality framework limits the APVMA’s ability to provide assurance that assessments are undertaken in accordance with legislative requirements and are appropriately evidenced. The risk of divergence from legislative requirements is heightened in the context of poor workflow management support systems and lack of staff clarity in the processing of applications.

2.45 In 2014–15 the APVMA established an internal Registration Quality Committee to provide ‘advice on APVMA frameworks to foster excellence in decision making; overseeing quality assurance and the administration of decision making on registrations to ensure that decisions are consistent, timely, transparent and predictable’. In 2016 the Committee considered a project to document the elements of good regulatory decision making, undertake a gap analysis against existing capability and develop a quality assurance framework. This ‘Quality Decision Making’ Project commenced in July 2016, but was suspended in December 2016.30

2.46 The implementation of a quality framework would assist the APVMA to detect and address any inconsistent practices among assessment staff as well as demonstrate the appropriate application of standards and procedures to support rigorous regulatory decision-making.

Recommendation No.1

2.47 The Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority should implement an internal quality framework to provide an appropriate level of assurance that its assessments are undertaken in a consistent manner and made in accordance with agvet chemical legislation.

Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority’s response: Agreed.

2.48 The APVMA agrees the quality assurance framework for agvet chemical assessments can be improved. The APVMA believes the current processes for assessment of agvet chemicals are robust, with appropriate documentation and based on sound evidence, as acknowledged in the ANAO report. This provides for high quality scientific decision making for registration of agvet chemicals in line with the legislative framework.

2.49 Internal governance committees for registration management and science quality are operational within the agency to provide assurance that regulatory decision making is in line with legislative requirements, fit-for-purpose and consistent. The terms of reference for these committees will be reviewed to ensure they reflect action to implement the recommendation.

2.50 The APVMA will support the work of the committees through a program of better documentation of assessment frameworks, targeted training for assessment staff, and business process and IT improvements to standardise application processes as much as possible and improve consistency.

2.51 The APVMA notes the ANAO’s suggestion regarding analysis of pre-application assistance outcomes with a view to developing appropriate industry guidance. The agency agrees improved guidance for industry continues to be an area for improvement and has commenced a process in consultation with industry to develop better guidance material for high volume applications.

2.52 The APVMA notes the ANAO’s suggestion to develop intelligence collection and analysis arrangements to strengthen its compliance and enforcement strategy and will include this suggestion in future strategies.

3. Reform outcomes

Areas examined

The ANAO examined the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority’s (APVMA’s or the Authority’s) development and use of performance monitoring strategies, and the extent to which it has improved its efficiency and lowered the regulatory burden on industry since the legislative reforms came into effect in July 2014.

Conclusion

The APVMA has not established a robust performance measurement framework to measure the effectiveness of the reform program in achieving greater efficiency of its activities and in reducing the regulatory burden on industry. While performance measures that have been established by the Authority provide insights into the delivery of regulatory activities—for example the timeliness of decision-making—they do not clearly indicate the extent to which reform objectives are being achieved. The limited performance information retained by the APVMA indicates that it has not achieved greater efficiencies in the delivery of its regulatory activities and, overall, the regulatory burden on industry has not been reduced since the reforms were implemented.

Area for improvement

The ANAO has made one recommendation aimed at improving the benchmarks and targets used by the APVMA to measure the effectiveness and efficiency of its regulatory activities.

Was a robust performance measurement framework established to assess effectiveness and efficiency of regulatory activities?

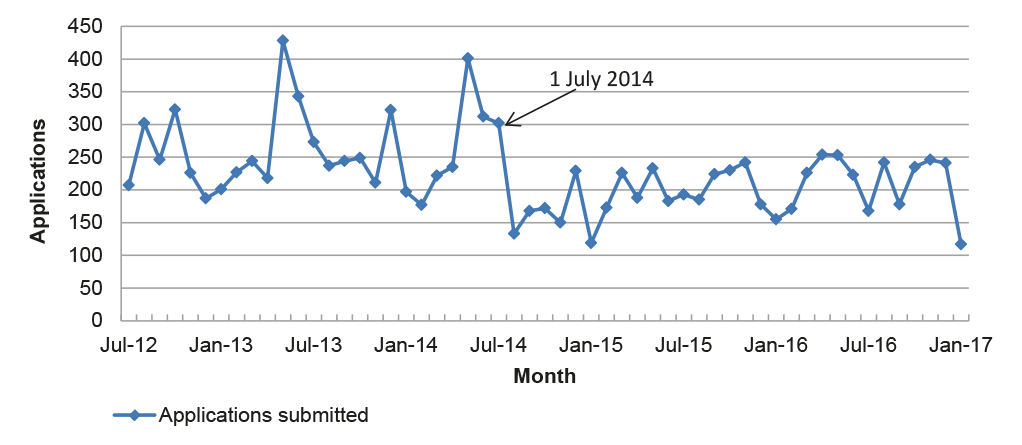

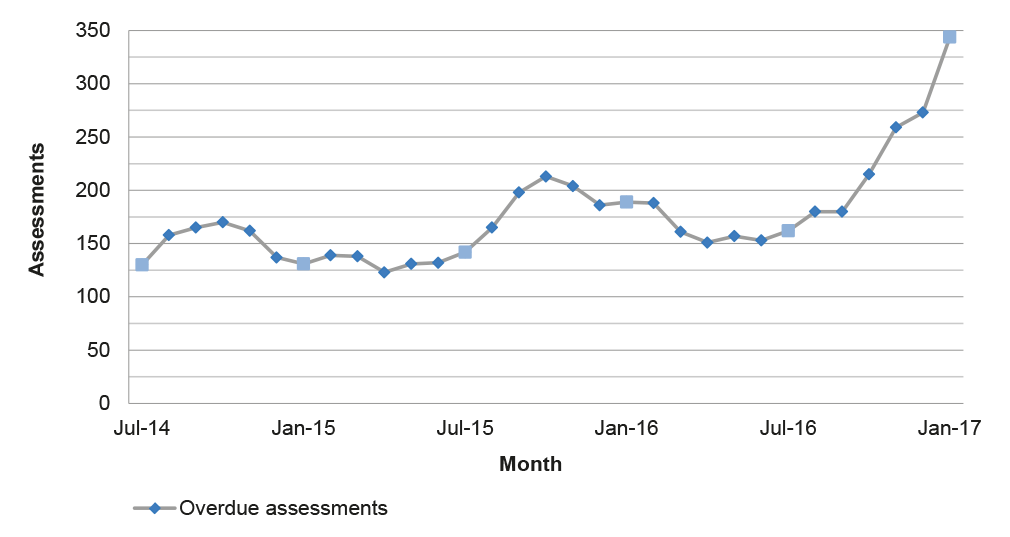

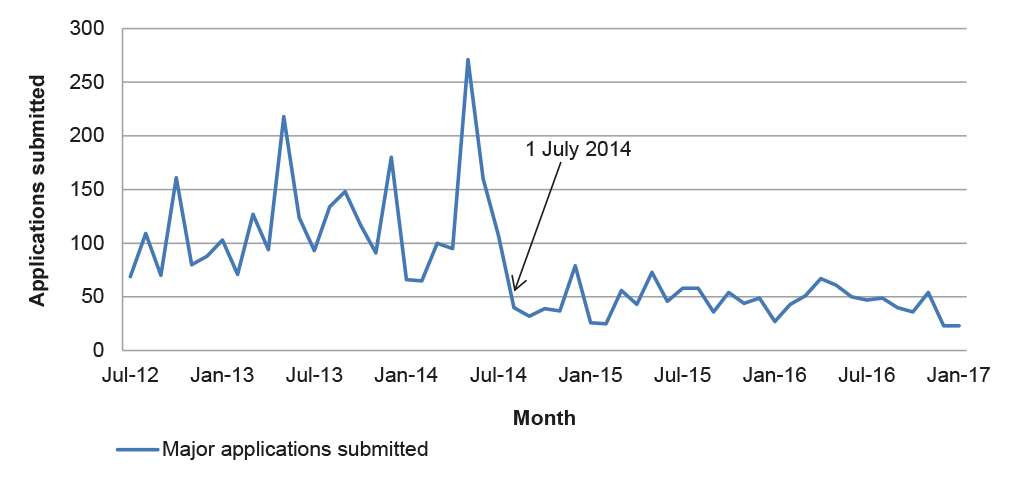

The APVMA has established a corporate planning framework based on performance strategies, key result areas and performance measures. These measures established by the APVMA cover a broad range of activities but in aggregate do not enable a robust and well-rounded assessment of overall performance over time. The Authority has established appropriate monitoring arrangements in relation to the timeliness of assessments, with improved reported performance in the period 2014–2016, followed by a decline in the six months to March 2017. These fluctuations in the timeliness of assessments have taken place while a backlog of overdue assessments has grown during 2016.

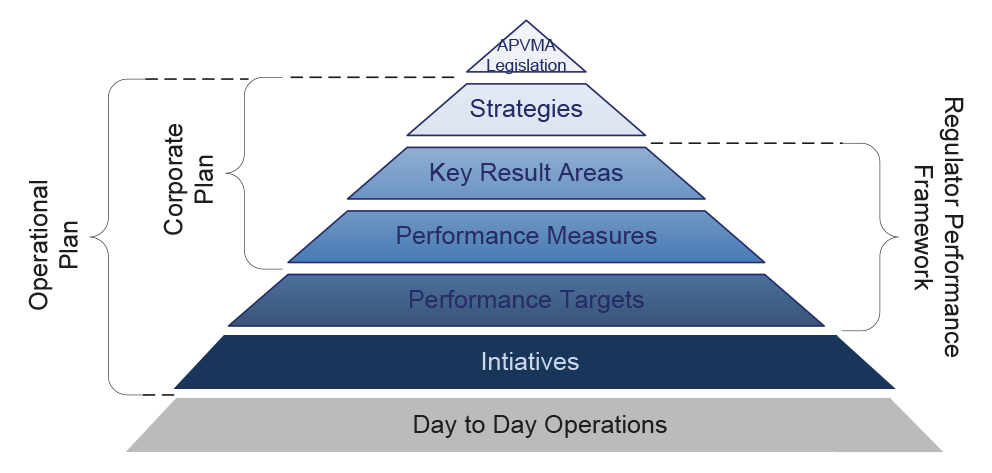

3.1 The APVMA’s performance monitoring arrangements are based on indicators established within its Corporate Plan, Operational Plan, and as outlined in the Regulator Performance Framework.31 The Authority’s corporate planning framework is outlined in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1: APVMA’s corporate planning framework

Source: ANAO analysis of APVMA information.

Corporate plan

3.2 The APVMA’s Corporate Plan 2015–20 included the following four key strategies:

- deliver regulatory decisions that are timely, science-based and proportionate to the risks being managed;

- reduce the burden on industry in complying with regulatory requirements;

- build a client focused approach to service delivery, committed to continuous improvement; and

- operate as a contemporary, high performing and efficient organisation.

3.3 These strategies are linked to nine key result areas and 22 performance measures.

Operational Plan

3.4 The APVMA is required to produce an operational plan each year in accordance with s.55 of the Agricultural and Veterinary Chemicals (Administration) Act 1992. The Operational Plan 2015–16 links the strategies, key result areas and performance measures outlined in the Corporate Plan 2015–20 with 70 performance measures and 77 initiatives.32

3.5 Individual performance measures should be relevant and reliable, indicating the desired level of achievement (target) and an expected timeframe. Collectively, performance measures should enable an overall assessment of the extent to which a program or function is achieving its established objectives. While the APVMA’s performance measures cover a broad range of its activities, in aggregate they do not enable a robust and well-rounded assessment of overall performance over time. The ANAO’s assessment of the APVMA’s performance measures is outlined in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1: The ANAO’s review of the APVMA’s performance measures

|

Characteristic |

Assessment |

|

Relevant |

|

|

Reliable |

|

|

Complete |

|

Source: Examples selected extracted from the APVMA information.

Monitoring and reporting

3.6 The APVMA’s Executive Leadership Team (ELT) is responsible for reviewing performance reporting against its operational plans. However, the ELT’s review of performance reports has been ad hoc and generally focused on the second half of each financial year. The operational plan reports that have been provided to the ELT listed each initiative/activity, including the responsible director, milestones, progress indicators and comments on work planned, in progress or undertaken. In late 2015, the APVMA revised its performance reporting processes. Under this process, additional reports against the Operational Plan initiatives that are classified under ‘major projects’ are provided to the Major Projects Board, which was established in October 2015.33

3.7 The APVMA’s performance against its corporate and operational plan measures was reported in its 2015–16 Annual Report. Examples of the APVMA’s reporting against its performance targets are outlined in Table 3.2.

Table 3.2: Examples of the APVMA’s reporting against its performance measures

|

Performance target |

Result reported by the APVMA |

|

Timeframe performance met for 100 per cent product registration |

66 per cent. |

|

Four stakeholder forums held each year to discuss issues affecting regulated entities |

The APVMA held more than four stakeholder forums and meetings with key industry associations throughout 2015–16 to discuss operational and other matters affecting agvet chemical regulation. |

|

Feedback from stakeholders about the quality of guidance material |

There is a feedback mechanism on every web page containing guidance material. All feedback is assessed and referred to business owners for action. A useability review will be completed in 2016–17 and recommendations will inform further improvement to guidance material. |

|

Documented compliance and enforcement strategy, including options for graduated compliance, in place |

The compliance and enforcement strategy, which is underpinned by a risk-based approach is available under ‘Corporate documents’ (apvma.gov.au/node/11026). |

|

Number of corporate training days per full-time equivalent (FTE) |

During the 2015–16 financial year, staff participation in training averaged 5.1 training days per FTE. |

Source: Extracted from the APVMA information.

Timeliness of assessment decision-making

3.8 Timeliness of assessment decision-making is a primary performance metric for the APVMA and of particular interest to industry stakeholders. Delays in the completion of assessments can add to the time required by industry to introduce new and varied products to market and can increase the risk of certain products being unavailable for a cropping season. To help improve timeframe predictability for industry, the 2014 reforms provided new statutory timeframes for assessment decision-making based on a revised methodology. Since July 2014, timeframe performance for new assessments is based on ‘elapsed time’ from lodgement to finalisation, rather than the previous ‘clock time’ methodology, which excluded non-assessment time during which the APVMA waited for applicants to provide additional material.34

3.9 The APVMA’s arrangements for monitoring the timeliness of assessments has gained maturity since 2014 and is now well established, with the publication of quarterly performance reports on its website. The ANAO analysis of APVMA data indicates that, across all applications, the APVMA finalised applications on time in 79 per cent of cases in 2014–15 and 68 per cent of cases in 2015–16. Under the previous ‘clock time’ methodology, prior to the implementation of the reform program, the APVMA reported an overall timeframe performance of 90 per cent of applications finalised within statutory timeframes in 2013–14, up from 89 per cent the previous year.

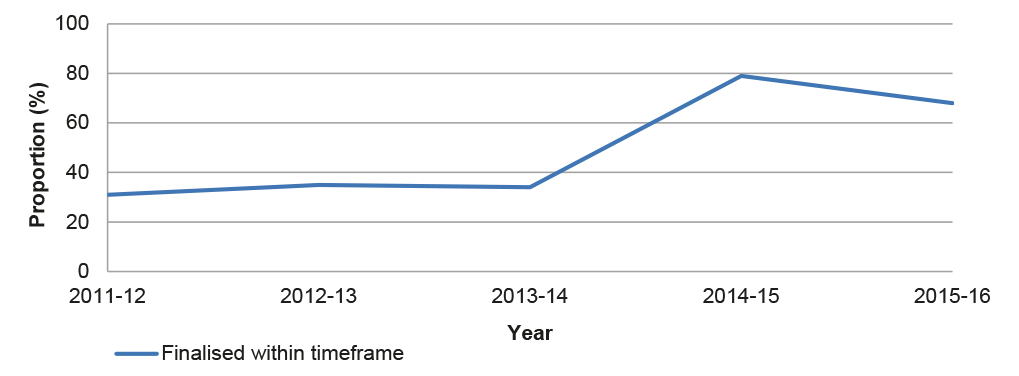

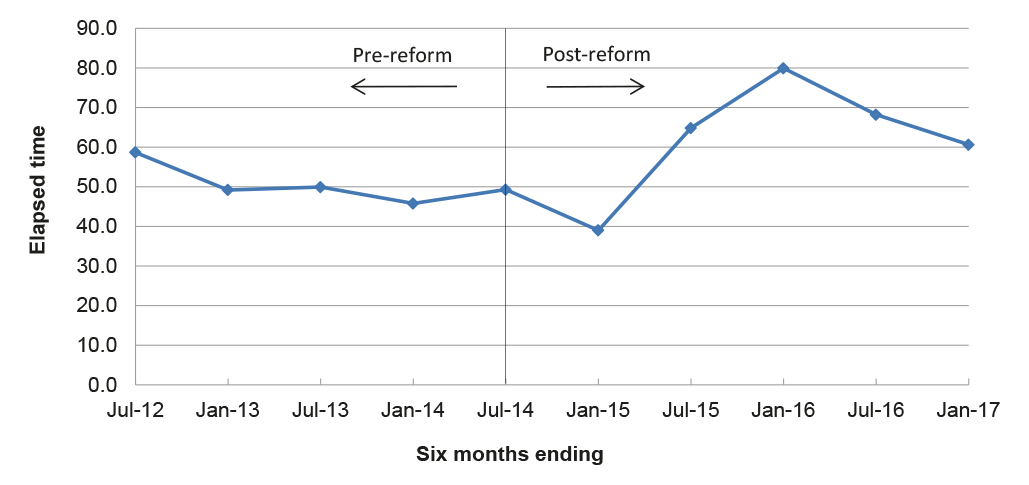

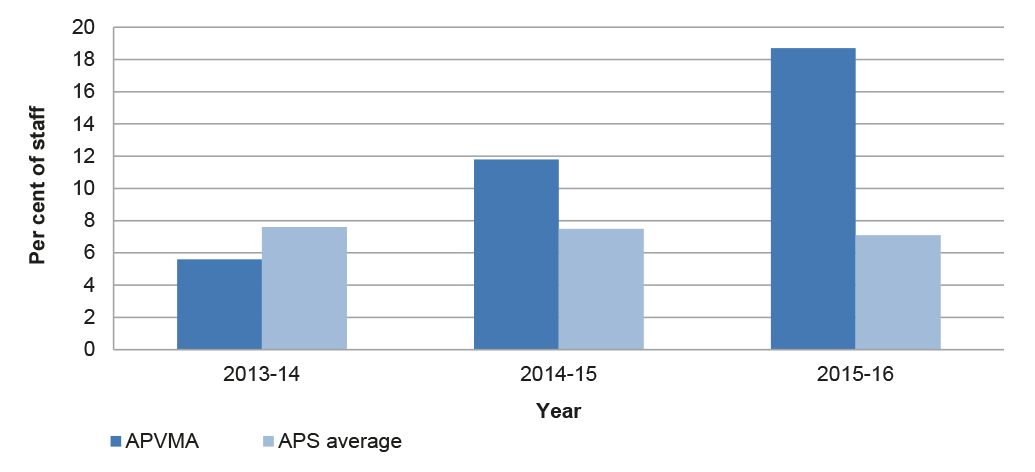

3.10 The ANAO re-calculated the APVMA’s timeframe performance for the three years prior to July 2014 based on the current elapsed time methodology, illustrated in Figure 3.2. In the pre-reform period the proportion of applications finalised within the elapsed timeframe ranged between 31–35 per cent, and rose to 79 per cent in the first year of the post-reform period.

Figure 3.2: Timeliness of assessments based on elapsed time, 2011–2016

Note: The methodology adopted by the ANAO includes all applications from the period of the commencement of assessment to the finalisation of an application (date of regulatory decision) and is consistent with the methodology adopted by the APVMA’s published application duration statistics produced by its internal auditors, available at: <http://apvma.gov.au/sites/default/files/publication/20246-apvma-application-duration-statistics_oakton.pdf>, [accessed 22 March 2017].

Source: ANAO analysis of APVMA information.

3.11 However, the APVMA’s timeframe performance in the post-reform period has been influenced by fewer submissions received for application categories with a timeframe greater than six months, and fewer applications overall. The number of applications submitted for assessment in the post-reform period has declined, from an average of 260 per month prior to July 2014 to 201 per month after, as illustrated in Figure 3.3.

Figure 3.3: Total applications submitted per month, July 2012 to January 2017

Note: Excludes notifiable variations and pre-application assistance.

Source: ANAO analysis of APVMA information.

3.12 Against the backdrop of fewer applications for assessment and improved timeliness in the post-reform period, the number of overdue assessments at the end of each month has fluctuated between 123 and 213 until late 2016 when there was a rapid increase to 344 at the end of January 2017, as illustrated in Figure 3.4. This suggests an accumulation of overdue assessments that are yet to be finalised at the end of each month.35

Figure 3.4: Overdue assessments by month, July 2014 to January 2017

Note: Includes products, chemicals and transitional applications submitted to the APVMA from 1 July 2012. Overdue assessments were calculated using the ‘clock time’ methodology between 1 July 2012 and 30 June 2014 and the elapsed time methodology after 1 July 2014.

Source: ANAO analysis of APVMA information.

3.13 The APVMA’s reported timeframe performance in the six months to March 2017 indicates a decline in timeliness from 83 to 42 per cent of product applications and 77 to 62 per cent of all applications (products, chemicals and permits).

3.14 Overall, data trends on the timeliness of assessments suggest an initial improvement in performance compared with the pre-reform period. This has been followed by fluctuations in the level of assessments completed on time and a recent decline, in the context of fewer applications to be assessed and an increasing backlog of overdue assessments.

Self-assessment against the Regulator Performance Framework

3.15 The APVMA has also reviewed its performance under the Australian Government’s Regulator Performance Framework. In its first self-assessment of performance under the framework, covering the period 2015–16, the Authority outlined activities undertaken in relation to the framework’s six indicators, and the results achieved.36 The APVMA is yet to externally validate its self-assessment through stakeholder input, as required by the framework, prior to publication.

3.16 The APVMA’s reported progress towards effective and efficient regulation included regular interactions with industry and improved performance against timeframes. The report focussed on examples of success and did not clearly identify areas for improvement against targets or provide a reliable indication of the extent of overall improvement over time.

Are regulatory activities being delivered more efficiently?

The APVMA has not demonstrated greater efficiencies in the delivery of regulatory activities following its implementation of the regulatory reform program. While the Authority has not established a robust means to assess the extent to which efficiencies have been achieved, the ANAO’s analysis of available performance data and industry feedback indicates a decline in efficiency since 2014.

3.17 As outlined earlier, the APVMA has not established a robust performance measurement framework that, among other things, would assist the Authority to determine the extent to which efficiencies in its delivery of regulatory activities are being achieved. Such a framework could include performance measures with reference to resourcing levels and outputs over time, the ratio of corporate expenditure to expenditure on regulatory activities or benchmarking with similar regulatory bodies.

Assessment completion and resourcing

3.18 In the absence of a robust performance measurement framework to assess the impact of the 2014 reforms, the ANAO compared actual assessment completion durations (outputs) with assessment fees charged to industry (inputs) as a proxy measure of efficiency over time. The assessment period in which the APVMA is required to finalise an application varies depending on the complexity of the application. According to the Australian Government Cost Recovery Guidelines 2014, application fees should be set so that revenue (fees) generated from the assessment is equal to the expenses (resource time cost) incurred in undertaking the assessment. The APVMA’s fee structure generally correlates less complex assessments with shorter timeframes and lower fees.

3.19 To derive a proxy efficiency index, the ANAO divided the APVMA’s total actual assessment times by the total fees for those assessments over six month periods (elapsed time per application dollar). The lower the time per dollar, the greater the efficiency being achieved. In the six months to June 2012, the APVMA finalised 1224 assessments that had taken a total time of 3828 months to complete and which attracted fees of $2 858 429, equating to about 59 elapsed minutes per application dollar. The index of elapsed minutes per application dollar then fluctuated between 39–50 over the pre- and post-reform period until the end of 2014, when the index doubled from 39 to 80 over the following 12 months, prior to a decline to 60. This suggests an overall decrease in efficiency in the post-reform period compared with the pre-reform period, as illustrated in Figure 3.5.

Figure 3.5: Elapsed time per application dollar

Note: The analysis includes products, chemicals and transitional applications, based on the actual application fees applied where cost data was available, and an average item fee for modular assessments as a proxy indicator of fees in the absence of APVMA data on the actual fees applied to these applications. Of the 11 862 completed assessments included in the analysis, the proxy average item fee was applied to 87 modular assessments in the post-reform period and 1550 in the pre-reform period. The analysis excludes withdrawn applications, pre-application assistance and notifiable variations.

Source: ANAO analysis of the APVMA information.

3.20 On the basis of the limited data available, the elapsed time for assessments per application dollar has increased over the two and a half years following the implementation of reform. In order to better understand the cost of assessments and identify potential areas for efficiency savings, there is scope for the APVMA to develop systems to collect and analyse accurate and comprehensive information about its assessment related activities.

Notifiable variations

3.21 A factor in the decline of the overall number of applications was the introduction of the Notifiable Variations Scheme on 1 January 2015. The Notifiable Variation Scheme removed the requirement for regulated entities to formally apply for low risk minor variations. Notifiable variations are deemed to be granted when they are lodged with the APVMA after checks are conducted. There are currently 13 types of notifiable variations, such as changes to the name of a product and to the safety instructions. In 2015–16, 736 variation notices were lodged with the APVMA and 696 variations were issued.37 The introduction of notifiable variations would likely have resulted in time and cost savings, given that, under the pre-reform system these variations would have been lodged and processed as applications. The APVMA has not, however, retained data to enable the extent of any efficiency improvements to be assessed.

Corporate expenditure